Abstract

Cavitation erosion is a major concern in hydraulic systems exposed to strong pressure fluctuations. Well-developed experimental techniques exist for detecting cavitation based on measuring induced noise or vibrations, but additional tools are needed to assess its aggressiveness under operating conditions. This study investigates the capability of acoustic emission (AE) to characterise cavitation aggressiveness during long-duration cloud cavitation. A 50 h erosion test was performed in a closed-loop cavitation tunnel using a Venturi equipped with an aluminium 7075-T6 specimen. Hydraulic conditions were controlled to maintain a constant cavity length, and AE signals were recorded every 10 min during two representative 4 h intervals at 34–38 h and 46–50 h. A new AE-derived power parameter was defined using the amplitude distribution of AE envelope peaks. Both the number of impacts and the power parameter increased markedly from the intermediate to the final interval, consistent with the growth of erosion and increasing surface roughness. Conversely, both quantities decreased systematically within each 2 h test as water temperature increased. Image analysis of selected areas confirmed the progression of pitting between 34 and 50 h. Overall, the findings demonstrate that AE can capture the combined influence of temperature and surface degradation on cavitation aggressiveness, highlighting its potential as a monitoring technique for hydraulic components.

Keywords:

cavitation erosion; AE; cloud cavitation; temperature; erosion; venturi; cavitation tunnel; aluminium 1. Introduction

Cavitation occurs when the local pressure in a liquid falls below its vapour pressure, causing vapour bubbles to form without any heat being added, in contrast to boiling.

Cavitation can be generated in several ways [1,2]. (i) The geometry of the system can create velocity variations and, consequently, pressure variations. This type of cavitation is called hydrodynamic cavitation, and it is the most common in hydraulic machinery and hydraulic systems. (ii) Pressure variations can also be produced by sound waves, usually ultrasound, leading to ultrasonic cavitation. (iii) Optical cavitation is produced by a laser that creates bubbles, usually a single bubble.

Cavitation can erode the surrounding material when bubble collapses occur close to it. Karimi et al. [3] explained that the accumulation of shock-fatigue damage deforms surface layers and produces cracks that lead to material removal. Two main phases can therefore be distinguished in the cavitation erosion process: (1) the incubation period, during which only small plastic deformations (pits) can be seen, and (2) the period of material detachment and separation from the surface, which follows the previous one and results in mass loss [4].

AE is defined as a high-frequency vibration induced in a solid material due to elastic waves travelling inside it [5]. These elastic waves are generated by the energy released in the material due to sudden changes in internal stresses, external impacts, or surface contacts. As an AE source, cavitation represents external impacts resulting from bubble collapses near a solid boundary [5]. AE has a wide frequency band, but frequencies below 100 kHz are usually removed to filter out unwanted noise [6,7]. AE has been used to detect cavitation and to study its characteristics. For example, Escaler et al. [8] detected cavitation in several turbines using AE together with other quantities (such as vibrations and dynamic pressures). Signals were demodulated and different characteristic frequencies were identified. Ylönen [9] studied erosion in a cavitation tunnel using AE. The studies in [10,11] studied the incubation period and established a relationship between the cumulative distribution of amplitude peak values and pit diameters. As shown in [6], the shedding frequency obtained by demodulating the AE increases when erosion depth increases. A comprehensive review of the use of AE to detect and analyse cavitation was presented in [12]. Du et al. [13] developed a numerical model of ultrasonic cavitation to capture cavity evolution and pressure pulsation related to cavitation erosion and validated it experimentally. They concluded that cavitation erosion is primarily determined by cavity behaviour.

Several researchers have studied the relationship between the liquid temperature in which cavitation occurs and the resulting erosion. Hattori et al. [14] exposed pure copper and pure aluminium specimens to cavitating liquid jet tests at different temperatures and measured the mass loss. They concluded that mass loss increases as the liquid temperature increases until it reaches a maximum, after which it decreases. Li et al. [15] subjected stainless steel (AISI 304) specimens to ultrasonic cavitation at temperatures between 20 and 80 °C and found the maximum mass loss between 45 and 50 °C. Priyadarshi et al. [16] subjected two cast aluminium alloys (A356.2 and A380) to ultrasonic cavitation at temperatures between 10 and 50 °C and found the maximum mass loss at 30 °C. Dular [17] exposed aluminium specimens to cavitation in a cavitation tunnel at temperatures between 30 and 100 °C. Erosion in the incubation period was evaluated by pit counting, and the maximum erosion (maximum number of pits) was found at 60 °C. Ge et al. [18,19] conducted tests in a cavitation tunnel using water at temperatures between 24 and 85 °C, keeping the cavitation number and flow rate constant. They found that the sheet length increases with temperature up to around 55 °C (depending on cavitation number) and decreases afterwards. This behaviour can be explained by the combined effect of two factors: on one hand, the viscosity of the liquid (expressed by the Reynolds number) explains the sheet length increase at low temperatures; on the other hand, the thermodynamic effect (expressed by the thermodynamic parameter sigma proposed by Brennen [20]) becomes dominant and inhibits sheet growth at high temperatures.

The relationship between surface roughness and cavitation has also been studied. Escaler et al. [21] found that cavitation aggressiveness increases with the roughness of the tested specimen, with a roughly linear relationship. Hao et al. [22] studied the influence of rugosity on cloud cavitation behaviour. They concluded that the cavity on a rough surface may break off, shed, and collapse more than once in a period, which could lead to more severe cavitation erosion.

In this paper, the influence of fluid temperature and material surface condition on the number and intensity of cavitation impacts has been experimentally studied. A series of measurements of cavitation-induced AEs has been carried out in a closed-loop cavitation tunnel with a Venturi test section (TS) and a metallic sample. The sample was subjected to cloud cavitation for a very long period to visually observe cavitation damage. An AE-based parameter was defined to evaluate cavitation impacts and quantify their effects on cavitation aggressiveness. More specifically, Section 2 describes the test bench, the performed tests, and the definition of the AE parameter to estimate cavitation impacts. Section 3 presents the obtained results corresponding to operating parameters, cavitation aggressiveness levels, and observed cavitation erosion. Finally, Section 4 discusses the results and the main conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Bench Description

The tests were performed in a cavitation tunnel at the Barcelona Fluids & Energy Lab (IFLUIDS). The cavitation tunnel consists of a closed-loop circuit made of PVC pipes (Figure 1). The water circulation is provided by a 3 kW centrifugal pump whose rotating speed is controlled with a variable frequency drive. At the pump delivery, a partially filled tank (high-pressure tank) is used to damp the pressure fluctuations induced by the pump. Cavitation and its effects can be observed in a transparent PMMA TS where a Venturi has been installed to produce a static pressure drop at the throat and generate the corresponding cavitation (Figure 2). After the TS, there is another partially filled tank (low-pressure tank), and finally the water returns to the pump.

Figure 1.

Cavitation tunnel of the Barcelona Fluids & Energy Lab where the tests were performed.

Figure 2.

TS of the cavitation tunnel with the venturi and cavitation.

The system is instrumented with several sensors to measure the hydraulic variables: (1) absolute pressure sensors at the pump inlet, pump outlet, high-pressure tank, low-pressure tank, Venturi inlet, Venturi throat, and Venturi outlet; (2) temperature sensors at the bottom of the high-pressure tank and at the top of the low-pressure tank; (3) a magnetic flowmeter; and (4) the pump’s variable frequency drive (VFD) to control the pump rotating speed. A more detailed description of the cavitation tunnel is presented in [23].

The pressures at the free surfaces of the high- and low-pressure tanks, located at the inlet and outlet of the Venturi, respectively, can be controlled through a pneumatic system supplied with compressed air that can increase or decrease the pressures as required.

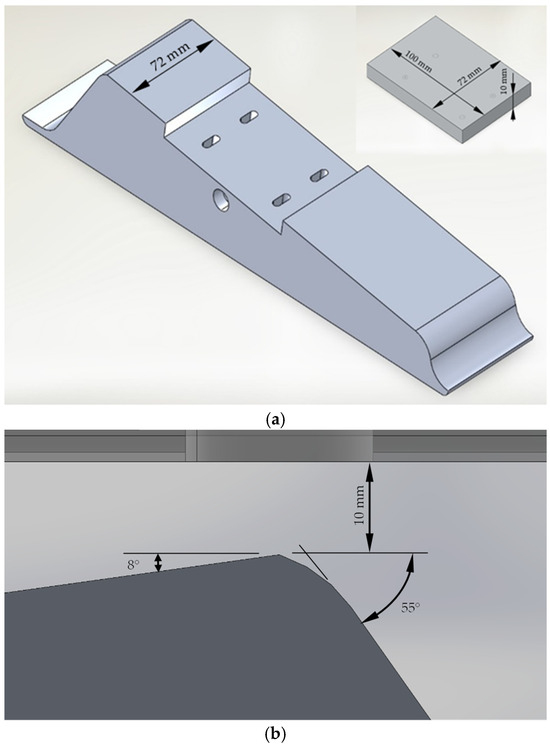

The basic geometry of the TS is a square 72 mm wide Venturi section consisting of a converging zone, followed by a throat section of 10 × 72 mm, and a diverging zone with an angle of 8°. The divergent zone has a housing to place the specimen, as shown in Figure 3. The throat contains a slight groove to trigger a homogeneous cavitation inception in the spanwise direction. This geometry was designed to generate cloud cavitation with significant erosive power over the material specimens, after evaluating different dimensions and shapes through numerical simulations and experiments.

Figure 3.

(a) Venturi section and removable metallic test specimen, and (b) zoom of the throat, with main dimensions.

2.2. Test Description

A 7075-T6 aluminium specimen was manufactured and mounted on the Venturi installed in the TS (Figure 3). This particular material is difficult to erode due to its high strength and hardness. Its mechanical properties are a yield strength of 503 MPa, an ultimate tensile strength of 572 MPa, and a Brinell hardness of 150 [24].

A long-duration erosion test was carried out for 50 h at steady flow conditions with periodic shedding cloud cavitation. The total running time was divided into 2 h periods to avoid an excessive temperature increase induced by pump heating. At the beginning of each period, the water was always at ambient temperature. Pressures and flow rate were maintained stable and similar for all runs in order to achieve cloud cavitation conditions with a constant maximum length in the range between 70 and 110 mm, so that the cavitation attack and the erosion always occurred within the aluminium specimen at the same location.

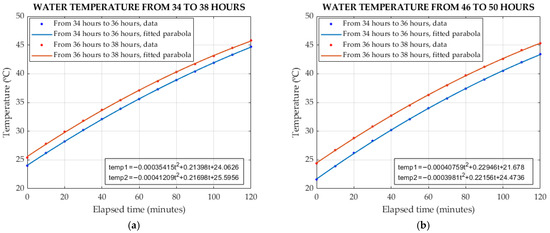

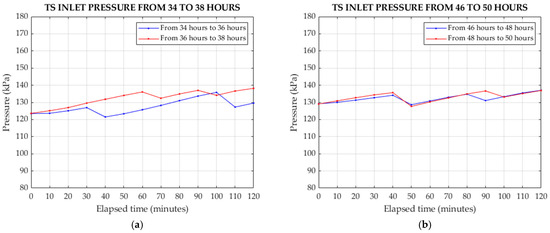

During a 2 h test period, the temperature of the system always increases by around 20 °C, as shown in the plots in Figure 4, where the temperature evolution is presented as a function of time. This temperature increase causes the system pressure to raise due to the heating of the air masses above the free surfaces in the upper part of the two tanks. Consequently, a reduction in the maximum length of the cloud cavitation is observed, which needs to be corrected to maintain similar aggressiveness levels and erosion location. Therefore, to keep the sheet length between 70 mm and 110 mm, successive purges of the air contained in the upper part of the high-pressure tank must be performed during each 2 h test. Figure 5 shows the evolution of the pressure at the Venturi inlet, where pressure drops occur during the purging process as air is released from the tank and the pressure is reduced. Between these drops, the pressure increases steadily as the temperature increases, as explained before. Because this correction is performed manually, some differences between runs can be observed, since the process has not yet been automated.

Figure 4.

Water temperature measured during the tests at the high-pressure tank, and their corresponding fitted parabolas. (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

Figure 5.

Evolution of the inlet pressure of the TS during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

Two specific time intervals of 4 h, each comprising two consecutive 2 h tests, were selected at the middle and at the end of the erosion tests. More precisely, these two periods were from 34 to 38 h and from 46 to 50 h, respectively. During these intervals, AE measurements were recorded every 10 min, and photographs of the sample surface were taken at their end to assess the evolution of the erosion. The first interval only showed an initial erosion stage, whereas the second one already presented a significant amount of erosion on the sample, which was not concentrated but dispersed.

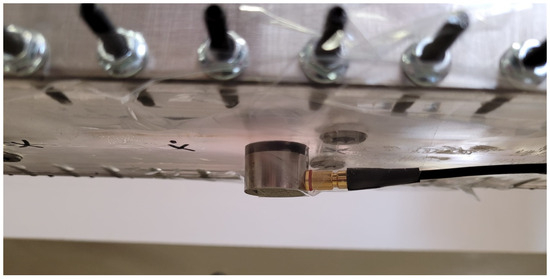

To measure the AE generated by cavitation, a Vallen 150-M sensor (Vallen Systeme GmbH, Wolfratshausen, Germany) was installed at the bottom of the TS, as shown in Figure 6. The rest of the AE setup consists of a Vallen AEP5 preamplifier, a Vallen DCPL2 decoupling box, and a National Instruments cDAQ-9185 (National Instruments Headquarter, Austin, TX, USA) connected to a laptop via Ethernet cable. The sampling rate was 1 MHz, and the measurement duration was 20 s. This means that each measurement consisted of 20 million samples.

Figure 6.

Sensor Vallen model 150-M fitted at the bottom of the TS.

2.3. Envelope Extraction of AEs

To determine the cavitation dynamic behaviour from the AE induced by the cavitation attack on the aluminium sample, it is considered that each collapse of a shed cloud results in a high-pressure, short-duration pulse on the sample surface that excites the solid like a hammer impact in a small area. Therefore, the AE transmitted through the Venturi and measured by the sensor on the external bottom wall of the TS appears to be modulated in amplitude at the characteristic shedding frequency of cloud cavitation. This shedding frequency can thus be inferred from the measured AE by applying an amplitude demodulation signal-processing method to its time signal.

The amplitude-demodulation procedure is based on the Hilbert transform. The Hilbert transform of a real-valued time-domain signal is another real-valued time-domain signal , which combines with to form the analytic signal . The magnitude function of the analytic signal, , describes the envelope of the original function [25].

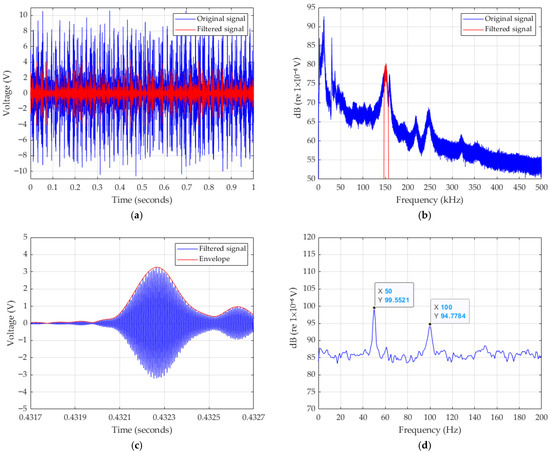

The Hilbert transform demodulation procedure requires a narrowband signal. Therefore, the first step in the analysis is a bandpass filtering to obtain a signal suitable for the Hilbert procedure. The filtered signal is also amplitude-modulated, as seen in Figure 7a, and it is narrowband, as shown in Figure 7b, which allows the Hilbert demodulation to be applied. To increase the accuracy of the method, a high signal level is required before applying the bandpass filter. In our case, the frequency band from 147 to 157 kHz was selected because it contains the first sensor resonance frequency (Figure 7b) and provides a good signal-to-noise ratio. Finally, the envelope of the filtered signal is calculated using the Hilbert transform, as illustrated in Figure 7c. The spectrum of this envelope is then computed using the Fast Fourier Transform to determine the exact value of the amplitude modulation induced by the periodic collapse of cloud cavitation, as shown in Figure 7d, with a peak frequency around 50 Hz and its second harmonic around 100 Hz.

Figure 7.

Procedure for calculating the shedding frequency from the measured AE. (a) Original and filtered time signals. (b) Original and filtered spectra. (c) Filtered signal and its envelope. (d) Envelope spectrum indicating the shedding frequency and its harmonic.

2.4. Cavitation Power Indicator Definition

In order to estimate the aggressiveness of cavitation, a power parameter has been defined according to the procedure described as follows:

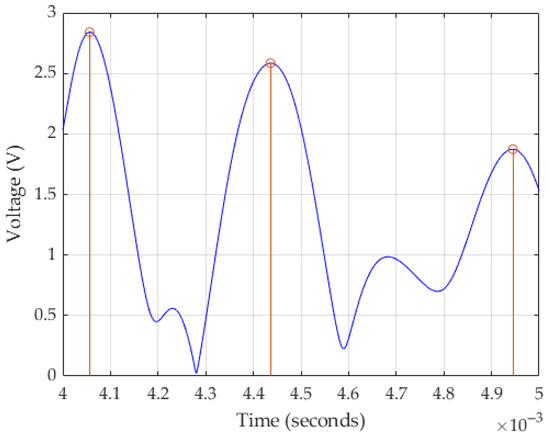

- The envelope of the AE signal is calculated using the method described in Section 2.3, and the peak values of this envelope function that are greater than 1 V are extracted. The set of such peak values is denoted by . In Figure 8, three of these peaks are identified in a short time interval of 1 ms.

- The peak values are grouped into 6 bins corresponding to the following amplitude ranges: , , , , , and .

- Assuming that each of these peaks corresponds to an impact produced by a collapsing bubble, the total energy delivered by the cavitating fluid during a given period and transmitted to the AE sensor can be estimated using the following parameter, named the Energy Parameter, :where is the number of elements in bin , and are the lower and upper boundaries of bin , and is an integer ranging from 1 to 6.

- To calculate the total power , the energy is divided by the acquisition period. This parameter is named the Power Parameter.

Figure 8.

Example of peaks identified with amplitudes (in red) higher than 1 V from the envelope function (in blue) obtained during 1 s of AE measurement.

3. Results

First, the evolution of the test rig operating parameters during the tests is presented. These parameters include the temperatures, pressures, cloud cavitation shedding frequencies, and cavitation numbers, calculated according to the following expression [26]:

where is the static pressure at the outlet of the TS, is the water vapour pressure, is the water density, and is the water speed at the throat.

Then, the aluminium surface condition and the observed increase in damage between the selected testing periods are presented. Finally, the cavitation power indicator results are compared between the two different periods.

3.1. Evolution of Operating Parameters During the Tests

Figure 4 shows the temperatures measured at the high-pressure tank and their corresponding fitted curves. The maximum difference between the temperatures of both tanks is 0.1 °C, so it can be assumed that the temperature along the cavitation zone is uniform. The temperature evolution shows an increase following a parabolic trend with downward-pointing branches, as seen in the fitted equations presented in Figure 4. The curves are roughly parallel, since the differences between the quadratic and linear coefficients of the fitted parabolas are negligible (see Figure 4). That is, the temperature evolution throughout the test depends only on its initial value. Table 1 shows the initial and final temperatures of the tests. The temperature increases are very similar, ranging between 20.6 and 22.0 °C, with an average of 21.2 °C.

Table 1.

Initial and final temperatures of the different periods, and their averages (in bold).

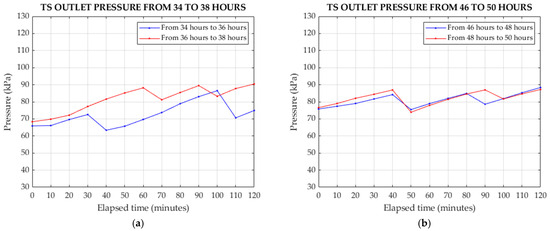

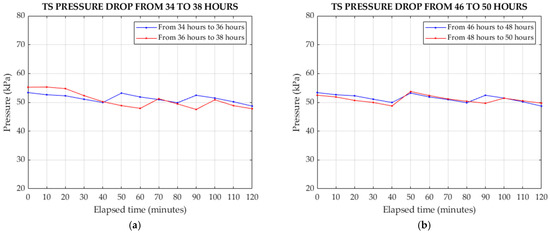

The pressures at the inlet and outlet of the TS are shown in Figure 5 and Figure 9, respectively. At the beginning of each test, the pressures increase together with the increase in temperature because the air mass above the two free surfaces inside the tanks remains constant. As previously explained in Section 2.2, periodic purges of the air contained in the upper part of the high-pressure tank are manually carried out to compensate for this pressure increase and to keep the pressures roughly constant.

Figure 9.

Evolution of the TS outlet pressure during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

Table 2 shows the maximum and minimum values of the inlet and outlet TS pressures and their pressure drop (inlet minus outlet), corresponding to the four analysed tests. For the intermediate tests, the inlet TS pressures fluctuate between 121.5 and 138.2 kPa, and the outlet TS pressures fluctuate between 63.4 and 90.4 kPa. For the final tests, the inlet TS pressures fluctuate between 127.7 and 137.1 kPa, and the outlet TS pressures fluctuate between 73.9 and 88.4 kPa. For all tests, the average range of inlet TS pressures is 11.7 kPa, and the average range of outlet TS pressures is 17.9 kPa.

Table 2.

Minimum, maximum pressures at inlet and outlet of the TS, the TS pressure drop, and their average values (in bold).

Figure 10 shows the evolution of the pressure drop in the TS (inlet pressure minus outlet pressure). The previously discussed fluctuations of the inlet and outlet TS pressures are clearly reflected in the pressure drop. However, the pressure drop behaves in the opposite manner: when the inlet and outlet pressures show a maximum, the pressure drop presents a minimum, and when the inlet and outlet pressures show a minimum, the pressure drop presents a maximum. According to Table 2, for the intermediate tests, the pressure drop fluctuates between 47.5 and 58.1 kPa, and for the final tests, it fluctuates between 48.7 and 53.7 kPa. For all tests, the average range of the pressure drop is 6.6 kPa.

Figure 10.

Evolution of the test pressure drop in the TS during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

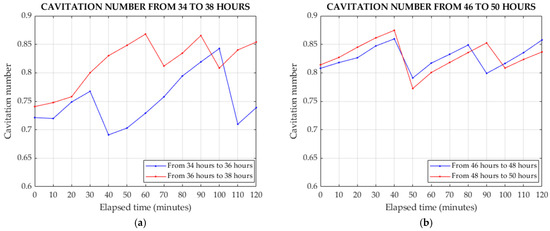

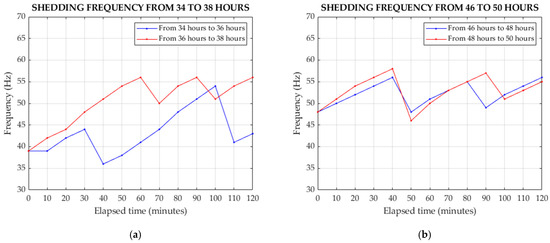

Figure 11 shows the evolution of the cavitation numbers, and Figure 12 shows the evolution of the cloud cavitation shedding frequencies identified from the maximum-amplitude frequency in the envelope spectrum, as explained in Section 2.3. The fluctuations of the inlet and outlet TS pressures are reflected in the cavitation number and in the shedding frequency values.

Figure 11.

Evolution of the cavitation numbers from TS outlet pressure during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

Figure 12.

Shedding frequencies during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and from 36 to 38. (b) From hours 46 to 48 and from 48 to 50.

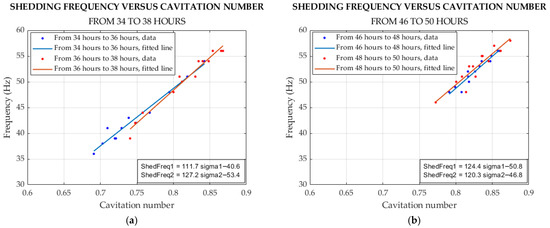

Figure 13 shows the shedding frequency versus cavitation number, where a linear relationship between both quantities is noticeable and is roughly the same for the four analysed tests, as shown by the fitted straight-line equations.

Figure 13.

Shedding frequencies versus cavitation numbers during tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and 36 to 38; (b) From hours 46 to 48 and 48 to 50.

By averaging the coefficients of the linear equations, the relationship between the cavitation number and the shedding frequency can be estimated using the following expression:

where is the shedding frequency and is the cavitation number according to Equation (3).

These results indicate that when the temperature increases, the TS inlet and outlet pressures also increase. Consequently, the cavitation number increases, and the maximum length of the cavitation cloud decreases, resulting in an increase in the shedding frequency, as confirmed by visual observations during the tests. This behaviour reinforces the need to purge the air periodically to maintain the sheet length at an acceptable level.

3.2. Cavitation Erosion Results

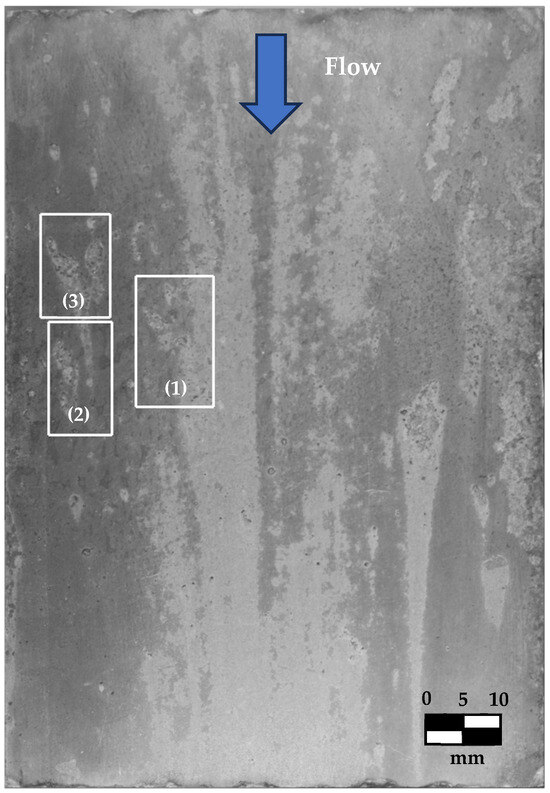

Although the specimen was subjected to 50 h of erosive cloud cavitation, the damage has not yet produced a measurable mass loss due to the large size and mass of the specimen. In addition, as previously explained, aluminium 7075-T6 is difficult to erode because of its high strength and hardness. As a result, the specimen has not yet been uniformly damaged, and the accumulated damage is insufficient to reach the material removal stage at a macroscopic scale. For this reason, three significantly damaged areas with a high concentration of pits were selected to analyse the changes in surface condition between the two analysed testing periods. These areas were chosen because visible differences between the two periods were observed. The sketch in Figure 14 shows the location of these selected areas.

Figure 14.

Specimen surface showing the photographed areas, named as 1, 2, and 3.

To compare the digital photographs pixel by pixel—given that they were taken from slightly different views—the following procedure was applied in Matlab® (version R2024b):

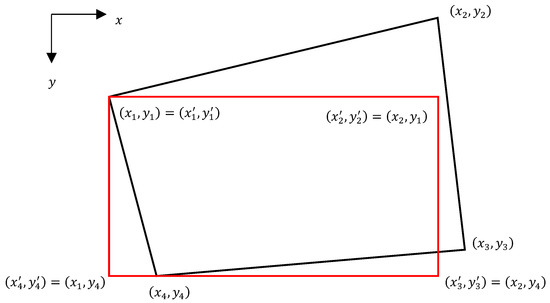

- A projective transformation using the function “tform” was performed, applying the transformation defined in Equation (5) to the specimen vertices with the coordinates shown in Figure 15.

- The images were cropped so that only the specimen surface was retained using the function “imcrop”.

- One image was resized so that both images matched in pixel dimensions using the function “imresize”.

Figure 15.

Detail of the projective transformation applied to a picture of a specimen taken from an arbitrary point (black line) that produces an image of the specimen taken from above the centre of the specimen (red line).

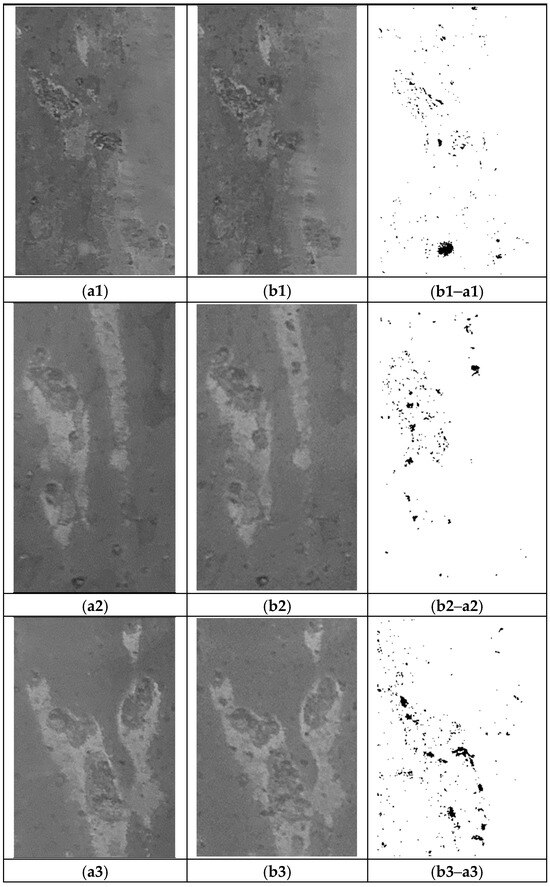

Figure 16 shows zones 1, 2, and 3: in the first column after 34 h of testing, labelled (a1), (a2), and (a3); and in the second column after 50 h of testing, labelled (b1), (b2), and (b3). The third column highlights the main differences between 34 and 50 h, labelled (b1–a1), (b2–a2), and (b3–a3). For each area, the percentage of eroded surface between 34 and 50 h of testing was calculated by dividing the number of dark pixels by the total number of pixels, giving the following results:

- Area 1 (b1–a1): 1.21%;

- Area 2 (b2–a2): 1.18%;

- Area 3 (b3–a3): 2.33%.

These results were obtained following the procedure below:

- Both colour images were transformed into black-and-white images.

- The corresponding pixel values of the two images were compared.

- If the difference exceeded 15 (threshold), the pixel was assigned a value of 0 (black), indicating that significant erosion had occurred.

- If the difference was less than 15, the pixel was assigned a value of 255 (white), indicating no erosion or insignificant erosion.

Figure 16.

Photographs of areas 1, 2, and 3 at 34 h: (a1–a3); at 50 h: (b1–b3); and the erosion that occurred between both: (b1–a1–b3–a3).

3.3. Cavitation Power Indicator Results

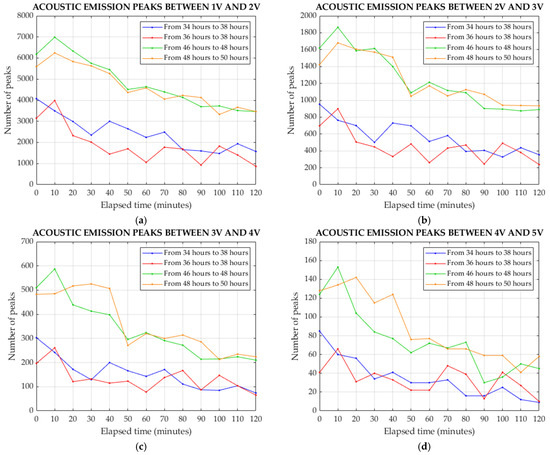

Figure 17 shows the evolution over time of the number of peaks corresponding to the clusters , , , and , as defined in Section 2.4, for the different AE measurements. It should be noted that the results for clusters and are not shown because they contained only a few peaks, making them statistically insignificant. Table 3 shows the mean number of peaks corresponding to the different clusters for the tests studied.

Figure 17.

Evolution of the number of peaks corresponding to different clusters, corresponding to different AE measurements during the tests: (a) Cluster of peaks between 1 and 2 V; (b) Cluster of peaks between 2 and 3 V; (c) Cluster of peaks between 3 and 4 V; (d) Cluster of peaks between 4 and 5 V.

Table 3.

Number of peaks of the different bins and power parameter.

On one hand, Figure 17 shows that the number of peaks decreases over time in all short-duration 2 h tests. Therefore, it can be concluded that the number of cavitation impacts decreases.

In addition, it is also observed that the number of peaks in the final tests is higher than in the intermediate tests. According to Table 3, these increases range from 121.2% (cluster between 1 and 2 V) to 143.8% (cluster between 3 and 4 V). Therefore, the number of cavitation impacts increases throughout the erosion process.

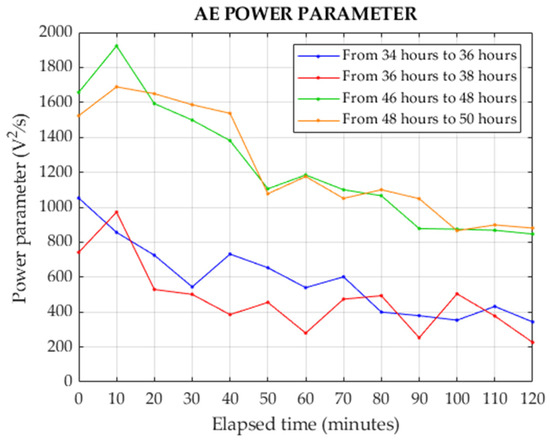

Figure 18 shows the temporal evolution of the power parameter defined in Equation (2). This parameter is a global indicator of cavitation power (i.e., number of impacts multiplied by their squared level and divided by time). Table 3 also lists this parameter for the different tests, along with the mean values for each group of tests. Figure 18 shows that, as before, the power parameter decreases during any continuous 2 h test. Moreover, the power parameter is significantly higher during the final tests at 50 h than during the intermediate tests at 38 h. According to Table 3, this increase is about 132.3%. It can thus be concluded that the power of cavitation impacts increases throughout the erosion process.

Figure 18.

Evolution of the power parameter during the tests.

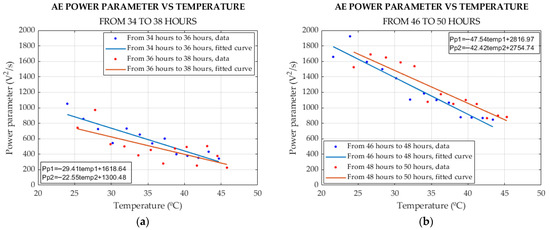

Figure 19 shows the power parameter as a function of temperature. The power parameter decreases when temperature increases. To quantitatively evaluate the influence of temperature on the power parameter, straight lines were fitted to the points corresponding to the different tests.

Figure 19.

Power parameter versus temperature during the tests: (a) From hours 34 to 36 and 36 to 38; (b) From hours 46 to 48 and 48 to 50.

Table 4 shows the slopes of the fitted lines and their mean values for the tests performed under the same conditions. The mean slope of the intermediate tests is −28.9 °/(V2/s), whereas the mean slope of the final tests is −44.6 °/(V2/s). Therefore, the influence of temperature is greater in the final tests, when the extent of erosion is larger.

Table 4.

Slopes of the different fitted lines and the averages corresponding to the tests performed at the same conditions.

4. Discussion

A cavitation erosion test was carried out for 50 h in a cavitation tunnel with a Venturi equipped with an aluminium specimen and subjected to cloud cavitation. Hydraulic conditions (pressures and flow rate) were controlled to maintain a maximum cavity length between 70 and 110 mm during all tests. The temperature increased during each short-duration 2 h test because of pump heating. This increase in temperature caused the pressure to rise, which was controlled and kept relatively constant by periodic manual purging of the air located in the upper part of the high-pressure tank.

During two specific time intervals, from 34 to 38 h and from 46 to 50 h, AE measurements were taken every 10 min. At 38 and 50 h, photographs of the eroded surface were also taken. Three particularly damaged areas were selected to analyse the changes in surface condition between the two periods. The increase in eroded surface in these areas was about 1.2%, 1.2%, and 2.3%, respectively.

The cloud cavitation shedding frequency was calculated from the AE measurements and was found to be related to the cavitation number in a roughly linear manner, which is consistent with the findings of Ylönen et al. [6].

Based on the AE measurements, impacts grouped into bins by amplitude range were estimated, and a general “power parameter” was defined. It was observed that the mean number of impacts and the value of the proposed power parameter increased from the intermediate interval to the final interval. Furthermore, both the number of impacts and the power parameter decreased over the course of each 2 h test as the temperature increased continuously.

The increase in the mean number of impacts and the mean power parameter from one test to the next one after 12 h of cavitation attack may be due to the increased roughness induced by cavitation erosion. Hao et al. [22] suggested that the cavity on a rough surface may rupture, detach, and collapse more than once within a period. This could explain the increase in cavitation impacts over time in these experiments.

The decrease in the number of impacts and the power parameter throughout a 2 h test could be due to the increase in temperature that occurs during pump operation. Priyadarshi et al. [16] studied the relationship between temperature and mass loss in two types of cast aluminium (A356.2 and A380) using ultrasonic cavitation. They found that mass loss increases with increasing temperature up to 30 °C, followed by a decrease. Assuming that the number of impacts and the power parameter calculated from the AE are estimators of cavitation aggressiveness, and considering that the maximum erosion temperature of the studied aluminium (A7075-T6) is unknown, as well as the moderate uncertainty produced by pressure oscillations, the findings of Priyadarshi et al. [16] and the present work may be consistent.

In industrial environments, having a system to evaluate cavitation and the resulting potential erosion based on AE offers the following advantages:

- Ease of installation: it is only necessary to place one or more sensors on the outside of the machine without accessing the wetted area.

- Vibration immunity: the high frequency of AE prevents contamination from other vibrations.

Regarding future work, further tests should be carried out with improved pressure control, avoiding manual air purges. Furthermore, AE should be measured continuously, and erosion should be assessed at short intervals to find a correlation between erosion and the proposed power parameter and to evaluate whether it is a good estimator of cavitation aggressiveness. In any case, AE appears to be a promising technique for the evaluation of cavitation and its erosion, as well as for identifying underlying parameters affecting it, such as water temperature and the degree of surface erosion.

5. Conclusions

A 50 h erosive cavitation test was conducted in a Venturi. At the midpoint and at the end of the erosion tests, two 4 h intervals were selected, and AE measurements were taken every 10 min during the 2 h short-duration tests. Based on the AE signals, the impacts were estimated, grouped into classes by level, and an overall erosion power parameter was defined. The main conclusions are the following:

- The mean number of impacts in different bins and the proposed power parameter increased between the intermediate and final intervals, which is related to the increase in roughness of the eroded surface.

- The average number of impacts in different bins and the power parameter decreased throughout each of the 2 h tests, which is related to the increase in water temperature.

- The results of the research initiated in this work confirm the suitability of using AE to predict and quantify erosive cavitation aggressiveness. This method can be used for predictive maintenance and condition monitoring in hydraulic machinery, increasing safety by reducing the possibility of catastrophic failures and the corresponding economic losses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.F.-O. and X.E.; methodology, I.F.-O., R.Z. and X.E.; software, I.F.-O. and D.B.; validation, I.F.-O. and X.E.; formal analysis, I.F.-O.; investigation, I.F.-O., D.B. and R.Z.; resources, X.E.; data curation, I.F.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.F.-O.; writing—review and editing, I.F.-O. and X.E.; supervision, X.E.; project administration, X.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank David Castañer for his help in setting up the cavitation tunnel, Elena Izquierdo for her collaboration in making the drawings of the TS and the team of the Barcelona Fluids & Energy Lab (IFLUIDS) for their technical support and assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dular, M.; Ohl, C.D. Bulk Material Influence on the Aggressiveness of Cavitation—Questioning the Microjet Impact Influence and Suggesting a Possible Way to Erosion Mitigation. Wear 2023, 530–531, 205061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogate, P.R. Application of Cavitational Reactors for Water Disinfection: Current Status and Path Forward. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 85, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, A.; Martin, J.L. Cavitation Erosion of Materials. Int. Met. Rev. 1986, 31, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franc, J.P.; Michel, J.M. Fundamentals of Cavitation; Moreau, R., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 76. [Google Scholar]

- Grosse, C.U.; Ohtsu, M.; Aggelis, D.G.; Shiotani, T. (Eds.) Acoustic Emission Testing, 2nd ed.; Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-67935-4. [Google Scholar]

- Ylönen, M.; Franc, J.P.; Miettinen, J.; Saarenrinne, P.; Fivel, M. Shedding Frequency in Cavitation Erosion Evolution Tracking. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2019, 118, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Kirschner, O.; Riedelbauch, S.; Necker, J.; Kopf, E.; Rieg, M.; Arantes, G.; Wessiak, M.; Mayrhuber, J. Influence of the Vibro-Acoustic Sensor Position on Cavitation Detection in a Kaplan Turbine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2014, 22, 052006. [Google Scholar]

- Escaler, X.; Egusquiza, E.; Farhat, M.; Avellan, F.; Coussirat, M. Detection of Cavitation in Hydraulic Turbines. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 2006, 20, 983–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylönen, M. Cavitation Erosion Monitoring by Acoustic Emission; Université Grenoble Alpes: Saint-Martin-d’Hères, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ylönen, M.; Saarenrinne, P.; Miettinen, J.; Franc, J.-P.; Fivel, M.C.; Fivel, M. Cavitation Bubble Collapse Monitoring by Acoustic Emission in Laboratory Testing. In Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Cavitation (CAV2018), Baltimore, MD, USA, 14–16 May 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylönen, M.; Saarenrinne, P.; Miettinen, J.; Franc, J.-P.; Fivel, M.; Laakso, J. Estimation of Cavitation Pit Distributions by Acoustic Emission. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Osete, I.; Bermejo, D.; Ayneto-Gubert, X.; Escaler, X. Review of the Uses of Acoustic Emissions in Monitoring Cavitation Erosion and Crack Propagation. Foundations 2024, 4, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Chen, F. Cavitation Dynamics and Flow Aggressiveness in Ultrasonic Cavitation Erosion. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 204, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, S.; Goto, Y.; Fukuyama, T. Influence of Temperature on Erosion by a Cavitating Liquid Jet. Wear 2006, 260, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Han, J.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Vibratory Cavitation Erosion Behavior of AISI 304 Stainless Steel in Water at Elevated Temperatures. Wear 2014, 321, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, A.; Krzemień, W.; Salloum-Abou-Jaoude, G.; Broughton, J.; Pericleous, K.; Eskin, D.; Tzanakis, I. Effect of Water Temperature and Induced Acoustic Pressure on Cavitation Erosion Behaviour of Aluminium Alloys. Tribol. Int. 2023, 189, 108994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dular, M. Hydrodynamic Cavitation Damage in Water at Elevated Temperatures. Wear 2016, 346–347, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Petkovšek, M.; Zhang, G.; Jacobs, D.; Coutier-Delgosha, O. Cavitation Dynamics and Thermodynamic Effects at Elevated Temperatures in a Small Venturi Channel. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 2021, 170, 120970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, M.; Zhang, G.; Petkovšek, M.; Long, K.; Coutier-Delgosha, O. Intensity and Regimes Changing of Hydrodynamic Cavitation Considering Temperature Effects. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennen, C.E. Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995; ISBN 0195094093. [Google Scholar]

- Escaler, X.; Dupont, P.; Avellan, F. Experimental Investigation on Forces Due to Vortex Cavitation Collapse for Different Materials. Wear 1999, 233–235, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, M.; Huang, X. The Influence of Surface Roughness on Cloud Cavitation Flow around Hydrofoils. Acta Mech. Sin. Lixue Xuebao 2018, 34, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, D.; Escaler, X.; Ruíz-Mansilla, R. Experimental Investigation of a Cavitating Venturi and Its Application to Flow Metering. Flow. Meas. Instrum. 2021, 78, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Automation Creations, Inc. Available online: https://matweb.com/search/propertysearch.aspx (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bendat, J.S.; Allan, G. Piersol the Hilbert Transform. In Random Data: Analysis and Measurement Procedures; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 473–503. [Google Scholar]

- Jahangir, S.; Ghahramani, E.; Neuhauser, M.; Bourgeois, S.; Bensow, R.E.; Poelma, C. Experimental Investigation of Cavitation-Induced Erosion around a Surface-Mounted Bluff Body. Wear 2021, 480–481, 203917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).