Synthesis and Treatment of Biosorbent from Cyanobacterial Biomass for the Removal of

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Adsorbents

2.2. Characterization of Adsorbents

2.3. Batch Adsorption Experiments

2.3.1. Experimental Process

2.3.2. Utilization of Modified Hydrochar as an Adsorbent

2.3.3. Effect of pH

2.3.4. Adsorption Kinetic Models

2.3.5. Adsorption Equilibrium Isotherm Models

2.4. Continuous Adsorption Experiments

2.4.1. Experimental Process

2.4.2. Column Adsorption Models

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Adsorbents

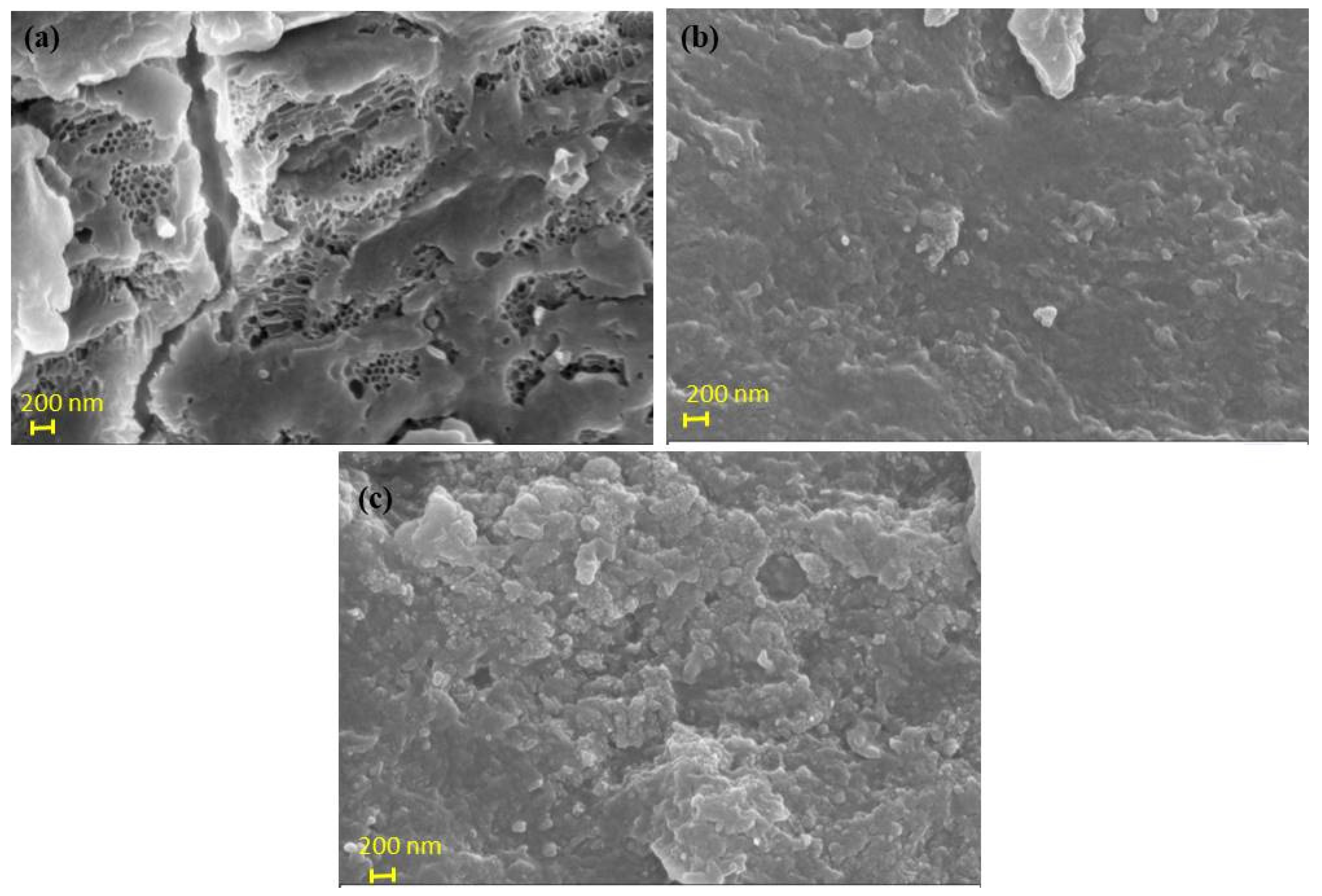

3.1.1. SEM

3.1.2. Zeta Potential-BET

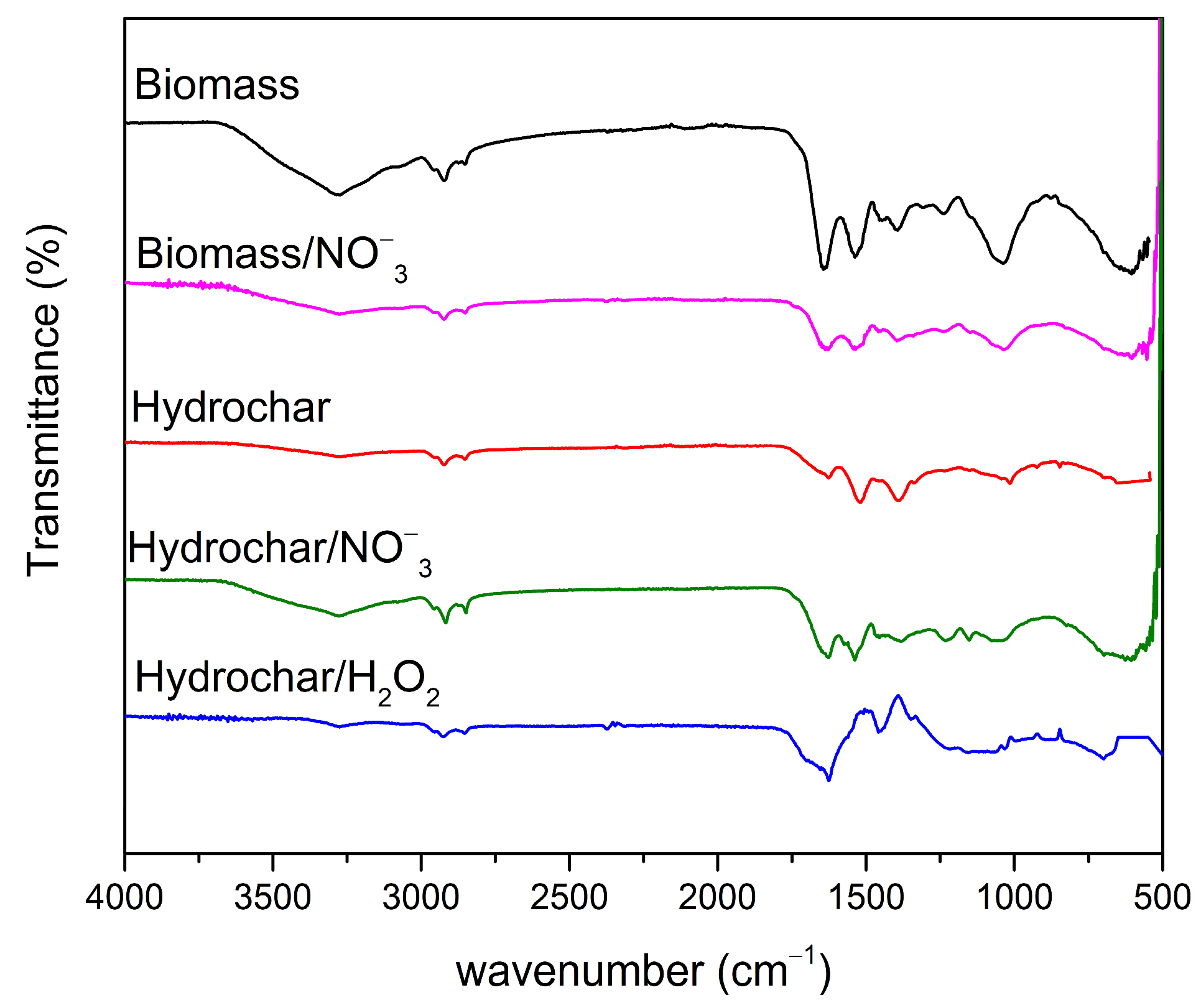

3.1.3. FTIR

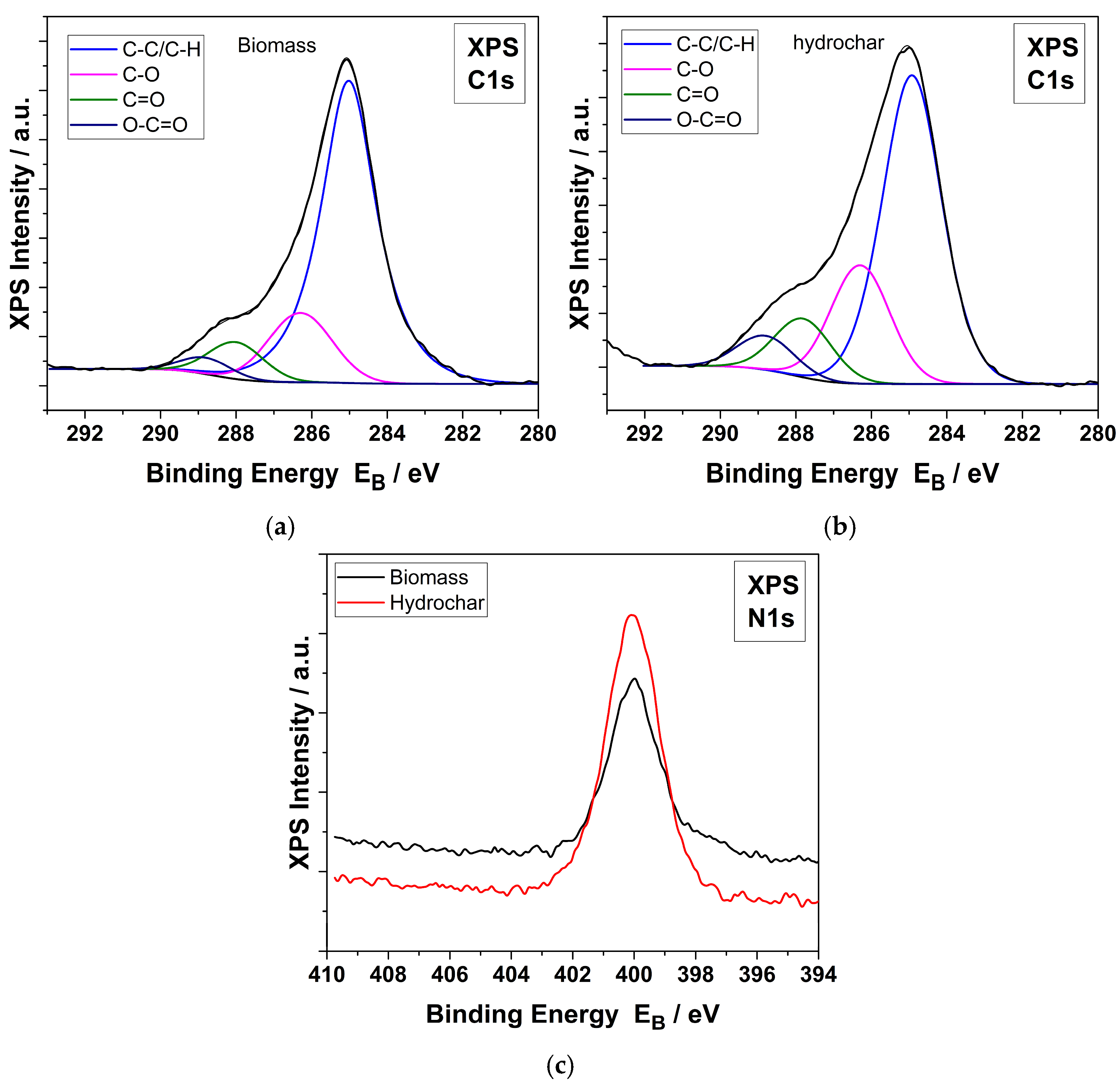

3.1.4. XPS

3.2. Batch Adsorption Experiments

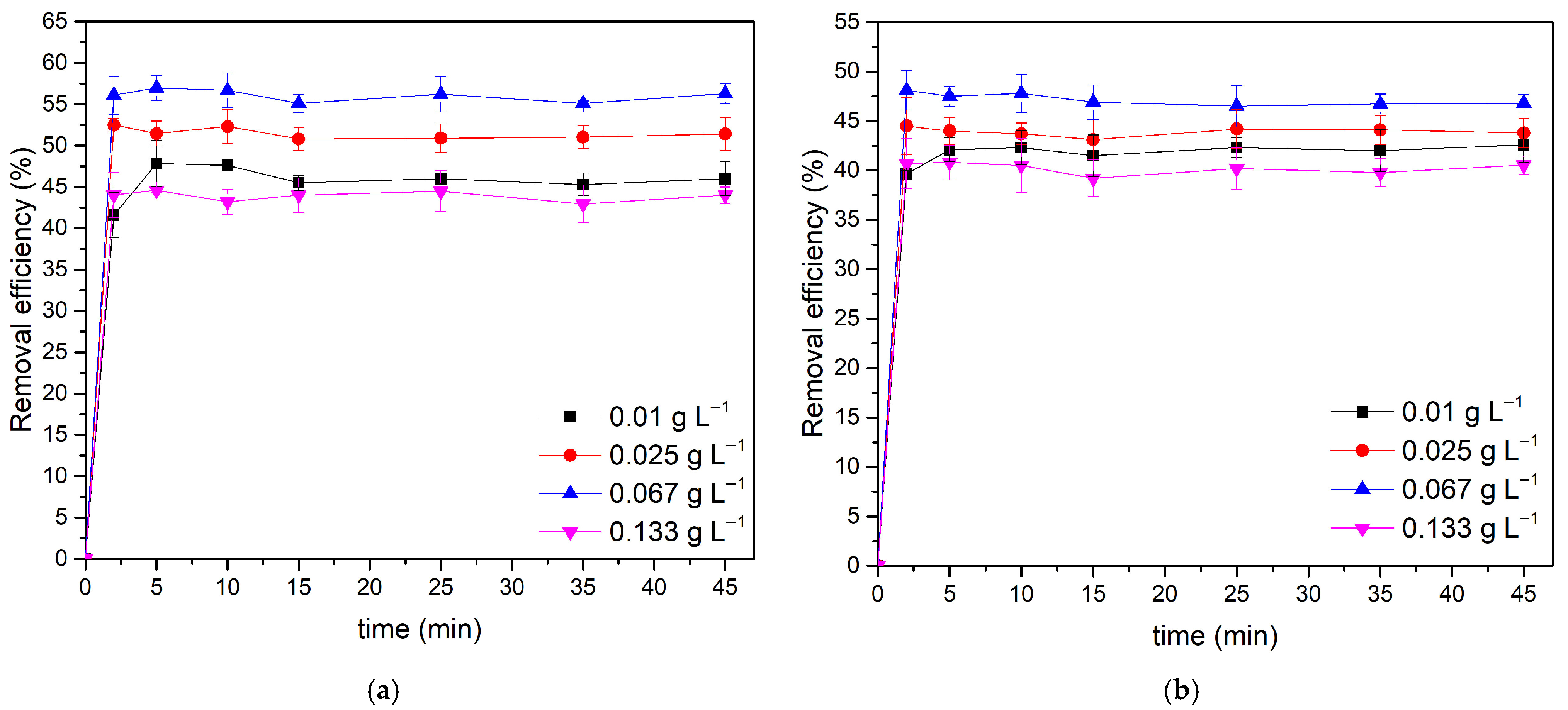

3.2.1. Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

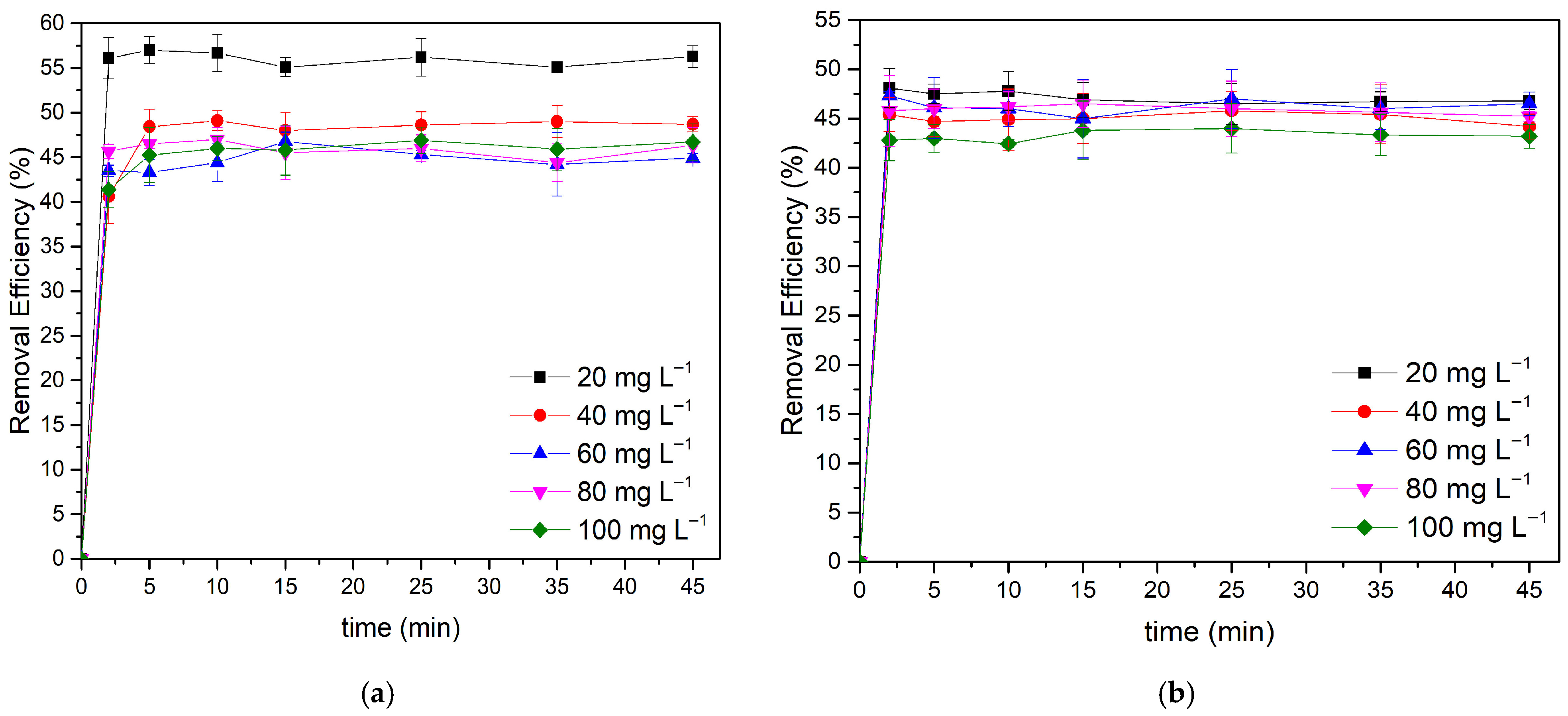

3.2.2. Effect of Initial Concentration

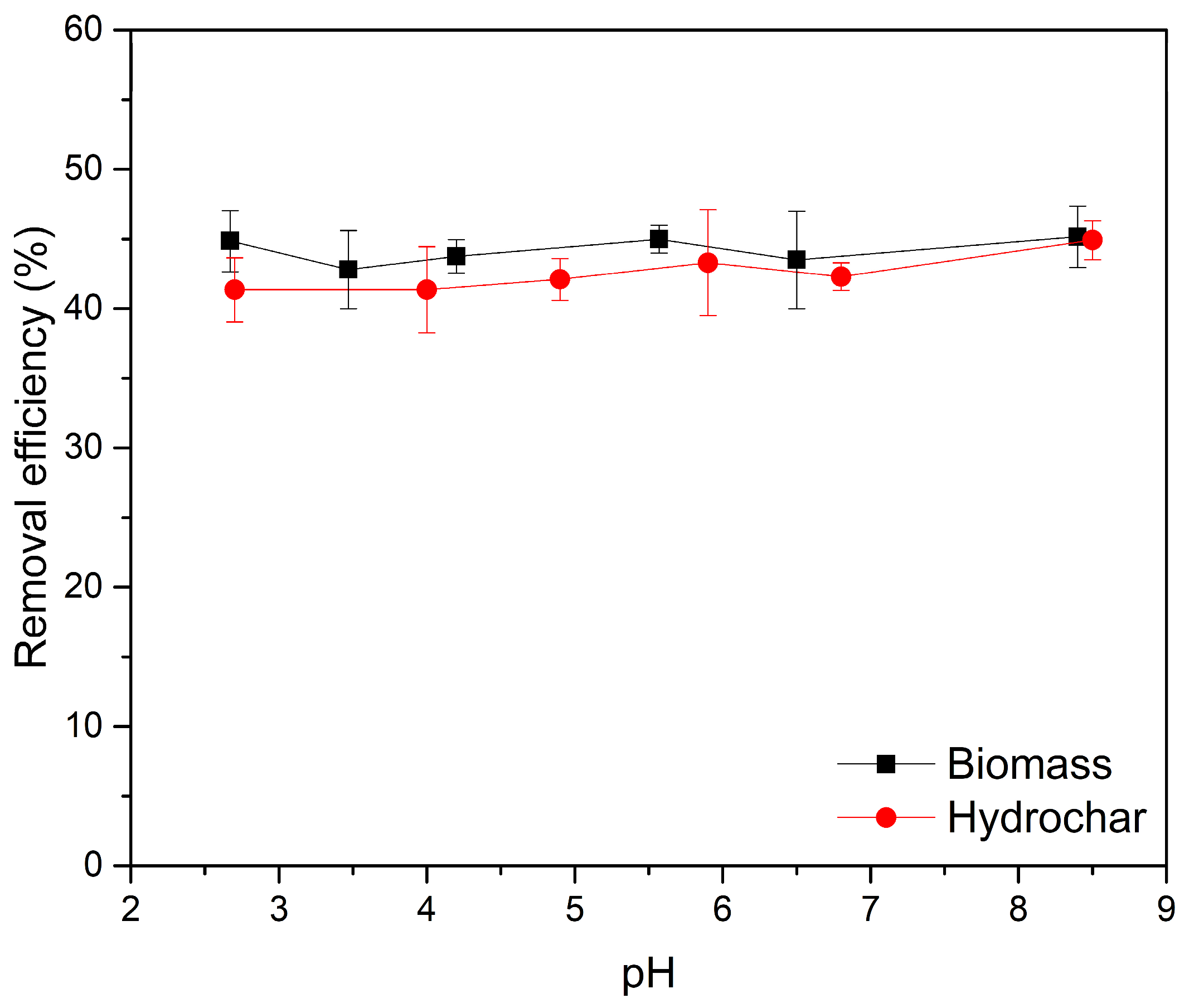

3.2.3. Effect of pH

3.2.4. Adsorption Kinetic Models

3.2.5. Adsorption Equilibrium Isotherm Models

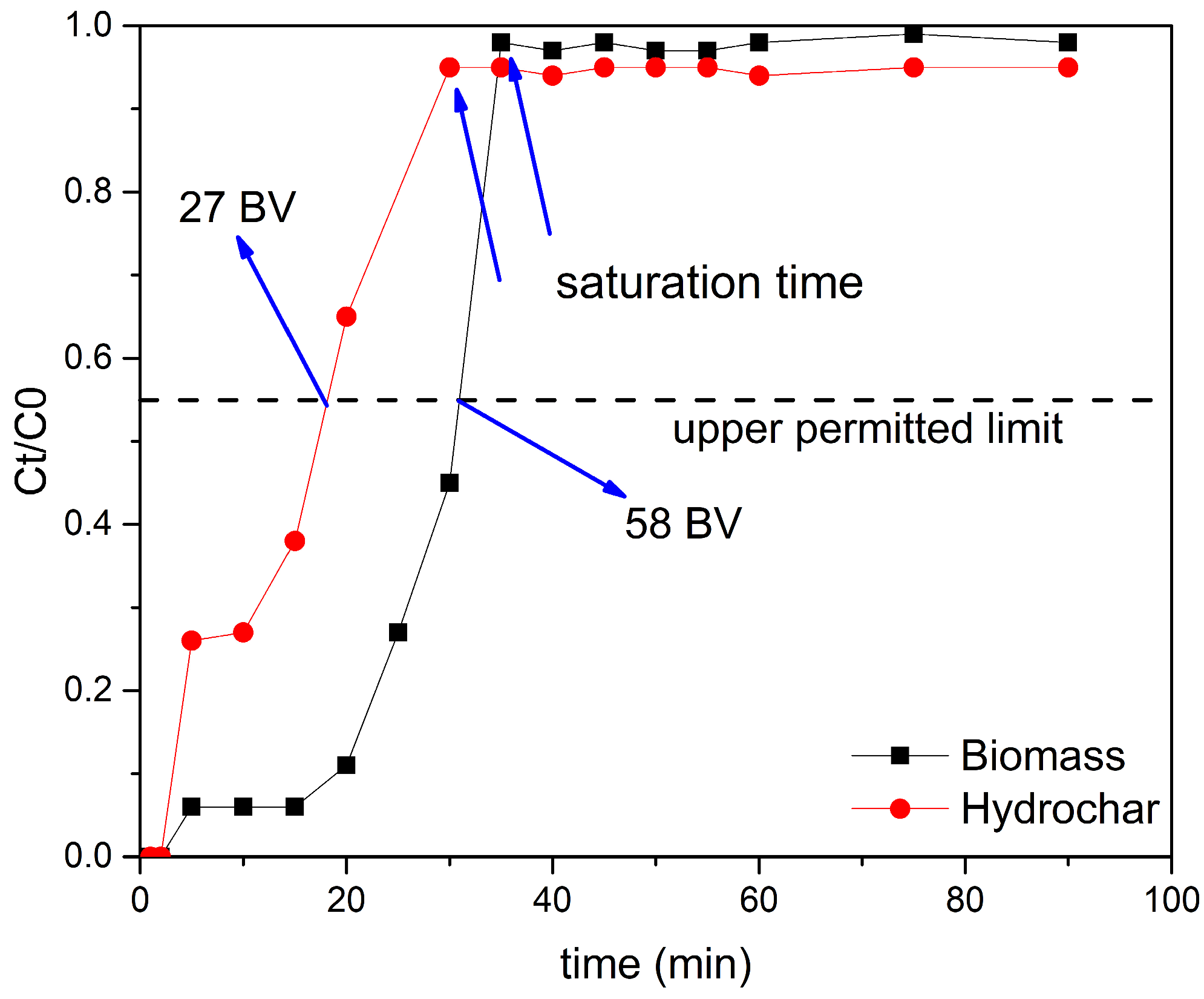

3.3. Continuous Adsorption Experiments

3.3.1. Experimental Results

3.3.2. Column Adsorption Models

3.4. Comparison with Other Literature Research

| Biomass | Thermal Treatment | Chemical Modification | Batch Experiments | Continuous Experiments | Ref. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorbent Dosage | Adsorbent Dosage | |||||||||

| Wheat straw | Pyrolysis | Use of with | - | - | - | [8] | ||||

| Sugarcane bagasse | Pyrolysis | Addition of amines | ≈70.0 | - | - | - | [9] | |||

| Elephant grass | Pyrolysis | - | - | - | - | [10] | ||||

| Corn | Pyrolysis | Use of Fe and amine | ≈90.0 | - | - | - | [11] | |||

| Hazelnut shell | - | Addition of amines | ≈90.0 | - | [12] | |||||

| Grape seed | - | Addition of amines | - | [13] | ||||||

| Date palm leaves | Pyrolysis | - | - | - | - | - | [49] | |||

| Macadamia | Pyrolysis | - | - | - | - | [50] | ||||

| Fruit lobes | Pyrolysis | Use of amines | - | - | - | [51] | ||||

| Sawdust | Pyrolysis | Use of iron chloride | - | - | - | - | [52] | |||

| Modified granular activated carbon | prepared by coating quaternary ammonium-containing polymer | 25.1–376 | 2.5 | 90–120 | ≈26 | [47] | ||||

| Cyanobacteria | - | - | This research | |||||||

| Cyanobacteria | Hydrothermal carbonization | - | This research | |||||||

| Cyanobacteria | Hydrothermal carbonization | Addition of | - | - | - | This research | ||||

4. Conclusions

- (i)

- Performance and mechanism. In its native state, the biomass achieved 40 to 56% nitrate removal at a low dosage, with equilibrium reached in almost 25 min. Its consistent advantage over the higher-surface-area hydrochar indicates that inherent surface chemistry and charge characteristics govern uptake more than surface area for the examined system.

- (ii)

- Model-based interpretation. Kinetic and equilibrium analyses were carried out by nonlinear regression of the original rate and isotherm expressions. The pseudo-first-order model provided physically consistent rate constants and capacities across all conditions, whereas the pseudo-second-order model produced non-identifiable or non-physical parameters in several runs and was not used for interpretation. The equilibrium data over 20 to 100 mg N L−1 were captured by the Freundlich equation, which accommodates site heterogeneity and does not impose a saturation plateau. Langmuir fits in this non-saturating window forced extrapolated qmax values without physical meaning and were therefore set aside.

- (iii)

- Continuous flow implementation. In fixed-bed columns, the biomass treated 58 bed volumes of influent to the 11.3 mg N L−1 nitrate-N threshold, compared with 27 bed volumes for the hydrochar at the same operating conditions. This outcome matches the batch evidence and reflects a more slowly advancing mass-transfer zone and a higher dynamic capacity for the native material.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| BET | Brunauer–Emmett–Teller |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| PFO | Pseudo-first-order |

| PSO | Pseudo-second-order |

| AB | Adams–Bohart |

| YN | Yoon–Nelson |

| D-R | Dubinin–Radushkevich |

References

- Lee, D.; Gibson, J.M.D.; Brown, J.; Habtewold, J.; Murphy, H.M. Burden of Disease from Contaminated Drinking Water in Countries with High Access to Safely Managed Water: A Systematic Review. Water Res. 2023, 242, 120244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Uppala, P.; Sambangi, A.; Haripavan, N.; Veerendra, G.T.N. Recycling of Solid Waste Biosorbents for Removal of Nitrates from Contaminated Water. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2022, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, M.E.; Guivernau, M.; Viñas, M.; Fernández, B.; Cáceres, R.; Biel, C.; Matamoros, V. Use of Wood and Cork in Biofilters for the Simultaneous Removal of Nitrates and Pesticides from Groundwater. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.C.; da Silva, R.A.; dos Santos, M.M.; Bovo, A.B.; da Silva, A.F. Assessing Nitrate Contamination in Groundwater for Public Supply: A Study in a Small Brazilian Town. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 25, 101084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, P.; Soria, J.; Moratalla-López, J.; Rico, A. Looking beyond the Surface: Understanding the Role of Multiple Stressors on the Eutrophication Status of the Albufera Lake (Valencia, Spain). Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.; Racoviteanu, G. Review of the Technologies for Nitrates Removal from Water Intended for Human Consumption. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the Sustainable Solutions for Energy and Environment, Bucharest, Romania, 21–24 October 2020; IOP Publishing Ltd.: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 664. [Google Scholar]

- Miriyam, I.B.; Anbalagan, K. Chicken Feathers Waste Biomass as an Effective Hierarchically Porous Adsorbent for Dimethyl, Diethyl and Dibutyl Phthalate: Mechanism, Performance, and Modeling of Batch and Continuous Adsorption Processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 319, 122233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Xuan, W.; Li, S.; Wei, A. Efficient Nitrate Adsorption from Groundwater by Biochar-Supported Al-Substituted Goethite. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafshejani, L.D.; Hooshmand, A.; Naseri, A.A.; Mohammadi, A.S.; Abbasi, F.; Bhatnagar, A. Removal of Nitrate from Aqueous Solution by Modified Sugarcane Bagasse Biochar. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 95, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesemuyi, M.F.; Adebayo, M.A.; Akinola, A.O.; Olasehinde, E.F.; Adewole, K.A.; Lajide, L. Preparation and Characterisation of Biochars from Elephant Grass and Their Utilisation for Aqueous Nitrate Removal: Effect of Pyrolysis Temperature. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Zhu, Q.; Zhen, J. Low Temperature Adsorption of Nitrate in Water by Ammoniac-Grafted Iron-Based Biochar: Electrostatic Interaction and Surface Complexation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 710, 136313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjepanović, M.; Velić, N.; Habuda-Stanić, M. Modified Hazelnut Shells as a Novel Adsorbent for the Removal of Nitrate from Wastewater. Water 2022, 14, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stjepanović, M.; Velić, N.; Habuda-Stanić, M. Modified Grape Seeds: A Promising Alternative for Nitrate Removal from Water. Materials 2021, 14, 4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadu, A.A.; Amoako, K.; Degraft-Johnson, A.; Komla Ameka, G. Chapter Industrial Applications of Cyanobacteria. In Cyanobacteria-Recent Advances in Taxonomy and Applications; IntechOpen: Londen, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kozyatnyk, I.; Benavente, V.; Weidemann, E.; Gentili, F.G.; Jansson, S. Influence of Hydrothermal Carbonization Conditions on the Porosity, Functionality, and Sorption Properties of Microalgae Hydrochars. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Zheng, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, B. Efficient Removal of U(VI) from Aqueous Solutions Using the Magnetic Biochar Derived from the Biomass of a Bloom-Forming Cyanobacterium (Microcystis aeruginosa). Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Rao, D.; Zou, L.; Teng, Y.; Yu, H. Capacity and Potential Mechanisms of Cd(II) Adsorption from Aqueous Solution by Blue Algae-Derived Biochars. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 145447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.P.; Economou, C.N.; Dailianis, S.; Charalampous, N.; Stefanidou, N.; Moustaka-Gouni, M.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Vayenas, D.V. Brewery Wastewater Treatment Using Cyanobacterial-Bacterial Settleable Aggregates. Algal Res. 2020, 49, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsialou, S.; Katapodis, D.; Antonopoulou, G.; Charalampous, N.; Qun, Y.; Dailianis, S.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Vayenas, D.V. Bioremediation and Toxic Removal Efficiency of Raw Pharmaceutical Wastewaters Treated with a Cyanobacteria-Based System Coupled with Valuable Biomass. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Bolan, N.; Jenkins, S.N.; Mickan, B.S. Organic Particles and High PH in Food Waste Anaerobic Digestate Enhanced NH4+ Adsorption on Wood-Derived Biochar. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; The Nineteenth and Earlier Editions; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawati, P.; Gusrianti, R.; Dwisiwi, B.B.; Purbaningtias, T.E.; Wiyantoko, B. Verification of Spectrophotometric Method for Nitrate Analysis in Water Samples. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Proceedings of the 2nd International Seminar on Chemical Education (ISCE) 2017, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 12–13 September 2017; American Institute of Physics Inc.: Melville, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Daneshvar, E.; Zarrinmehr, M.J.; Kousha, M.; Hashtjin, A.M.; Saratale, G.D.; Maiti, A.; Vithanage, M.; Bhatnagar, A. Hexavalent Chromium Removal from Water by Microalgal-Based Materials: Adsorption, Desorption and Recovery Studies. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 293, 122064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karri, R.R.; Jayakumar, N.S.; Sahu, J.N. Modelling of Fluidised-Bed Reactor by Differential Evolution Optimization for Phenol Removal Using Coconut Shells Based Activated Carbon. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 231, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S. Review of Second-Order Models for Adsorption Systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Modeling of Experimental Adsorption Isotherm Data. Information 2015, 6, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalfa, L.; Sdiri, A.; Bagane, M.; Cervera, M.L. A Calcined Clay Fixed Bed Adsorption Studies for the Removal of Heavy Metals from Aqueous Solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taty-Costodes, V.C.; Fauduet, H.; Porte, C.; Delacroix, A. Removal of Cd(II) and Pb(II) Ions, from Aqueous Solutions, by Adsorption onto Sawdust of Pinus Sylvestris. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 105, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhta, S.; Sadaoui, Z.; Bouazizi, N.; Samir, B.; Cosme, J.; Allalou, O.; Le Derf, F.; Vieillard, J. Successful Removal of Fluoride from Aqueous Environment Using Al(OH)3@AC: Column Studies and Breakthrough Curve Modeling. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Choi, T.R.; Gurav, R.; Bhatia, S.K.; Park, Y.L.; Kim, H.J.; Kan, E.; Yang, Y.H. Adsorption Behavior of Tetracycline onto Spirulina Sp. (Microalgae)-Derived Biochars Produced at Different Temperatures. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Zong, T.; Sun, Y.; Fang, W.; Shen, T.; Zhou, Y. Nano-Biochar Enhanced Adsorption of NO3−-N and Its Role in Mitigating N2O Emissions: Performance and Mechanisms. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A Review of the Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass Waste for Hydrochar Formation: Process Conditions, Fundamentals, and Physicochemical Properties. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, J.; Mosa, A.; Gao, B. Hydrochar Loaded with Nitrogen-Containing Functional Groups for Versatile Removal of Cationic and Anionic Dyes and Aqueous Heavy Metals. Water 2024, 16, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Long, L.; Chen, K.; Hu, X.; Xue, Y. Biodegradable Chitosan-Ethylene Glycol Hydrogel Effectively Adsorbs Nitrate in Water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 32762–32769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengenbach, T.R.; Major, G.H.; Linford, M.R.; Easton, C.D. Practical Guides for X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Interpreting the Carbon 1s Spectrum. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A Vac. Surf. Film. 2021, 39, 013204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirali, E.; Chronopoulos, I.; Yannopoulos, S.N.; Sygellou, L. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Analysis of Electrospun Polyacrylonitrile Fibers: Pre- and Post-Thermal Stabilization Investigations. Surf. Sci. Spectra 2024, 31, 024009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanyam, B.; Das, A. Linearised and Non-Linearised Isotherm Models Optimization Analysis by Error Functions and Statistical Means. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2014, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Lv, L.; Pan, B.C.; Zhang, Q.J.; Zhang, W.M.; Zhang, Q.X. Critical Review in Adsorption Kinetic Models. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2009, 10, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implications of Apparent Pseudo-Second-Order Adsorption Kinetics onto Cellulosic Materials: A Review. Available online: https://bioresources.cnr.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/BioRes_14_3_Review_Hubbe_AS_Implications_Appar_Pseudo_Second_Order_Sorptive_Kinetics_15852-1.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Tran, H.N.; You, S.J.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A.; Chao, H.P. Mistakes and Inconsistencies Regarding Adsorption of Contaminants from Aqueous Solutions: A Critical Review. Water Res. 2017, 120, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolster, C.H.; Hornberger, G.M. On the Use of Linearized Langmuir Equations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2007, 71, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da’ana, D.A. Guidelines for the Use and Interpretation of Adsorption Isotherm Models: A Review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, Z.; Gönen, F. Biosorption of Phenol by Immobilized Activated Sludge in a Continuous Packed Bed: Prediction of Breakthrough Curves. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 599–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Westerhoff, P.; Vermaas, W. Removal of Nitrate from Groundwater by Cyanobacteria: Quantitative Assessment of Factors Influencing Nitrate Uptake. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lee, S.J.; Noh, W.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Back, S.M.; Ryu, B.G.; Nam, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J. Production of Safe Cyanobacterial Biomass for Animal Feed Using Wastewater and Drinking Water Treatment Residuals. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.W.; Chon, C.M.; Kim, Y.; Jeon, B.H.; Schwartz, F.W.; Lee, E.S.; Song, H. Adsorption of Nitrate and Cr(VI) by Cationic Polymer-Modified Granular Activated Carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 175, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, A.M.; Dey, R.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Abd El-Monaem, E.M.; Ziora, Z.M. Insights into Recent Advances of Chitosan-Based Adsorbents for Sustainable Removal of Heavy Metals and Anions. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fseha, Y.H.; Sizirici, B.; Yildiz, I. Manganese and Nitrate Removal from Groundwater Using Date Palm Biochar: Application for Drinking Water. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8, 100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakly, S.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Bowtell, L. Macadamia Nutshell Biochar for Nitrate Removal: Effect of Biochar Preparation and Process Parameters. C 2019, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, D.; Mishra, P.C. Enhanced Biosorptive Incarceration of Nitrate from Aqueous Solutions Using Novel Green Adsorbent: Performance Optimization and Mechanistic Enlightenment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.Y.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, J.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Baek, K. Reduction of Nitrate Using Biochar Synthesized by Co-Pyrolyzing Sawdust and Iron Oxide. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| % C1s Peak Components | % at. Concentration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| samples | C-C/C-H | C-O/C-N | C=O/O-C-O | O-C=O | C | O | N |

| biomass | 72.7 | 16.6 | 7.5 | 3.1 | 72.3 | 21.7 | 6.0 |

| hydrochar | 60.7 | 22.5 | 10.6 | 6.2 | 71.1 | 20.0 | 8.9 |

| Adsorbent | Adsorbent Dosage | Pseudo-First Order Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass | |||||||

| Hydrochar | |||||||

| Model | Biomass | Hydrochar | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Freundlich | |||

| Biomass | Hydrochar | |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Biomass | Hydrochar | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yoon-Nelson | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mazarakos, G.; Lazaratou, C.V.; Frontistis, Z.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.G.; Georgakilas, V.; Vayenas, D.V.

Synthesis and Treatment of Biosorbent from Cyanobacterial Biomass for the Removal of

Mazarakos G, Lazaratou CV, Frontistis Z, Tekerlekopoulou AG, Georgakilas V, Vayenas DV.

Synthesis and Treatment of Biosorbent from Cyanobacterial Biomass for the Removal of

Mazarakos, George, Christina Vasiliki Lazaratou, Zacharias Frontistis, Athanasia G. Tekerlekopoulou, Vasilios Georgakilas, and Dimitris V. Vayenas.

2025. "Synthesis and Treatment of Biosorbent from Cyanobacterial Biomass for the Removal of

Mazarakos, G., Lazaratou, C. V., Frontistis, Z., Tekerlekopoulou, A. G., Georgakilas, V., & Vayenas, D. V.

(2025). Synthesis and Treatment of Biosorbent from Cyanobacterial Biomass for the Removal of