Featured Application

The findings suggest that inertial water-load equipment can be effectively applied in athletic training and rehabilitation to enhance dynamic stability and joint-moment control during landing and balance tasks.

Abstract

Maintaining lower-limb joint stability is essential for safe and efficient performance during landing and directional changes. This pilot study examined the effects of a 10-week perturbation-based Dynamic Stability Training (DST) program using an inertial water load on lower-limb joint moments during single-leg landing and a 3-s stabilization phase following a 90° cutting maneuver. Fifteen healthy young men completed DST twice weekly. Three-dimensional motion capture and force-plate data were collected at pre-, mid-, and post-training to compute hip, knee, and ankle joint moments. During landing, hip flexion and abduction moments increased, whereas knee abduction moment decreased. During the stabilization phase, hip flexion, hip rotation, and ankle abduction moments decreased, while knee abduction moment increased. These joint-specific changes suggest potential adaptations in frontal- and transverse-plane control when training with unstable inertial water loads; however, interpretations should remain cautious given the exploratory design and absence of a control group. Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm these preliminary findings.

1. Introduction

Landing tasks are fundamental motor skills in sports biomechanics, particularly when performed on a single leg from varying heights during competition [1]. The ground reaction force and kinetic energy absorbed upon landing impose considerable mechanical loads on the lower-limb joints. Inadequate energy absorption exposes vulnerable tissues such as ligaments and cartilage to excessive stress, increasing the risk of acute or overuse injuries [2,3,4]. In sports such as basketball, badminton, and handball, athletes frequently execute rapid directional changes or decelerations immediately after landing, which are closely associated with non-contact injuries, including anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture and valgus-related knee stress [5,6].

However, previous biomechanical studies have primarily focused on simplified tasks, such as bilateral drop landings [7]. In actual sports scenarios, landing is typically followed by multidirectional movements involving vertical, horizontal, and rotational forces [8]. These complex loads challenge the hip, knee, and ankle joints, and insufficient adaptation may lead to a loss of coordination, postural imbalance, or acute injury [9,10]. Moreover, athletes with ankle instability exhibit prolonged stabilization times and altered center of pressure (COP) trajectories during cutting maneuvers, reflecting impaired postural control [11,12,13,14,15,16]. Therefore, sport-specific biomechanical studies are needed to investigate joint loading and stability during post-landing directional changes.

To effectively perform these high-demand movements, athletes must coordinate joint biomechanics with neuromuscular control strategies [17]. Increased hip and knee flexion can compensate for ankle instability and facilitate shock absorption [18,19,20,21], whereas insufficient flexion, combined with excessive knee valgus angles, increases joint loading and injury risk [22]. Perturbation-based training (PBT) deliberately introduces unexpected external disturbances and has been reported to enhance neuromuscular reactivity, sensorimotor integration, and balance control [23,24,25,26,27]. Unlike conventional strength training, PBT emphasizes adaptability and dynamic stability, enabling athletes to cope with unpredictable conditions encountered during actual competition [26,28,29,30].

Among various perturbation modalities, the inertial load of water generates particularly high instability. The continuous movement of water within a bag produces unpredictable multidirectional forces that stimulate coordinated neuromuscular responses [31,32]. This waterbag-based intervention induces external perturbations resembling those experienced in athletic environments and has shown potential to improve dynamic stability and motor control [33].

Therefore, this pilot study aimed to investigate the effects of perturbation-based DST using an inertial water load on lower-limb joint moments during single-leg landing followed by a 90° cutting maneuver. It was hypothesized that ten weeks of waterbag training would enhance the control of hip, knee, and ankle joint moments during dynamic landing and stabilization tasks, thereby improving neuromuscular coordination and potentially reducing the risk of sports-related injuries such as ACL rupture or ankle instability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifteen healthy male university students aged 20–29 years were recruited through public advertisements at B University. All participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent before participation. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202504-01-008) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT07117617).

This pilot study was designed to evaluate the feasibility and preliminary biomechanical effects of perturbation-based DST using an inertial water load. Owing to its exploratory nature, a formal priori power analysis was not conducted. Pilot trials are recommended to focus on estimating variance and feasibility rather than hypothesis-testing; therefore, power calculations based on assumed effect sizes were not applicable at this stage. Instead, the sample size of fifteen participants was determined based on methodological recommendations for pilot studies, which suggest 10–15 participants for obtaining stable variance estimates and feasibility metrics in a single-group design [34,35,36]. To ensure the upper bound of the recommended range and improve the precision of variance estimation, we selected fifteen participants.

Previous perturbation and landing biomechanics studies have reported small-to-moderate effect sizes for time-dependent changes in joint moments (η2 ≈ 0.20–0.30) [19,37,38]. Considering these expected effect magnitudes and the high inter-individual variability typically observed in biomechanical outcomes, a sample of fifteen participants was deemed appropriate to achieve stable preliminary estimates while maintaining practical feasibility within a laboratory-based intervention.

The inclusion of homogeneous participants (healthy males aged 20–29 years) was intended to minimize heterogeneity and avoid confounding effects arising from sex-specific biomechanical differences or variations in movement skill proficiency. This sampling strategy allowed controlled examination of preliminary training-induced adaptations prior to expanding the target population in future randomized controlled trials.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- (a)

- Healthy adult males aged 20–29 years.

- (b)

- No structured physical activity during the six months prior to the study.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- (a)

- History of lower-limb surgery within the past year.

- (b)

- Presence of current musculoskeletal injuries, defined as:

- Pain ≥ 3/10 on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) during functional tasks (squat, single-leg stance, hopping);

- Clinically observable swelling, joint effusion, or restricted ROM (>10% asymmetry compared to contralateral limb), assessed by a certified sports medicine specialist.

- (c)

- Acute inflammation or severe pain, defined as:

- Visible redness, swelling, warmth, or localized tenderness on palpation;

- Inability to complete a full practice trial due to discomfort, as determined during pre-screening.

- (d)

- Neurological conditions confirmed through medical history questionnaire (e.g., vestibular disorders, peripheral neuropathy).

All participants completed the 10-week DST program using a waterbag, and their demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the pilot study.

2.2. Instrumentation

A three-dimensional motion capture system (Vicon MX-T20, Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) with six infrared cameras was used to record kinematic data at a sampling rate of 100 Hz, while ground reaction forces were collected at 1000 Hz using an AMTI OR6-7 force plate (Advanced Mechanical Technology Inc., Watertown, MA, USA). The force plate has a measurement capacity of ±5000 N with an accuracy of <0.1% full scale, providing high-fidelity kinetic data for subsequent inverse dynamics calculations. Sixteen reflective markers (14 mm diameter) were bilaterally attached to anatomical landmarks according to the Plug-in Gait lower-body model, including the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS), mid-lateral thigh, lateral femoral epicondyle, mid-shank, lateral malleolus, second metatarsal head, and calcaneus. Anthropometric variables (stature, body weight, leg length, knee width, and ankle width) were measured using a standard tape measure and caliper, and the values were entered into the Plug-in Gait model for segment parameter estimation.

Joint moments of the hip, knee, and ankle were calculated using inverse dynamics based on Plug-in Gait model outputs. Raw moment data (N·mm) were converted to N·m for analysis. Marker trajectory data (100 Hz) were low-pass filtered using a fourth-order Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 6 Hz, and ground reaction force data (1000 Hz) were filtered at 25 Hz. The cutoff frequencies were determined by residual analysis, consistent with previous studies on landing and cutting biomechanics [22,39].

To ensure data quality, marker trajectories were visually inspected for occlusion during preprocessing. Trials with prolonged marker loss or insufficient visibility of key anatomical markers were excluded and repeated as necessary. As a pilot study, all instrumentation and data-processing parameters were standardized according to conventional biomechanical protocols to ensure methodological feasibility and reliability for subsequent large-scale studies.

2.3. Data Acquisition

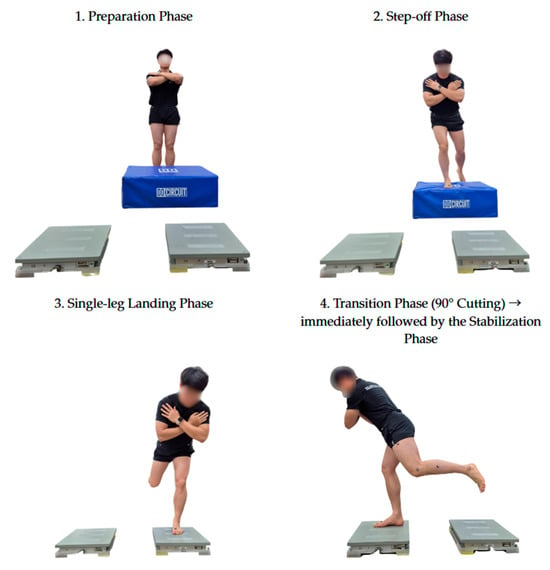

Participants were instructed to perform a single-leg landing immediately followed by a 90° cutting maneuver. From a standing position, each participant stepped off a 30 cm-high box with one leg, landed on the non-dominant leg, and immediately changed direction by 90° using the dominant leg [40]. The 30-cm height was selected based on previous landing biomechanics studies involving young adult males, in which 30–35 cm drop heights are commonly used to elicit sport-relevant loading without introducing excessive injury risk [19,22]. The experimental protocol was adapted from previous research demonstrating that the dominant limb primarily generates propulsive force during sport-specific directional changes [20,41]. Limb dominance was determined by asking which leg participants would naturally use to kick a ball, a standardized method commonly adopted in biomechanics research [42].

Prior to formal testing, participants completed three familiarization trials to ensure task comprehension. Because the landing–cutting task is relatively complex, additional practice trials were permitted whenever movement inconsistency or hesitation was observed, ensuring adequate familiarization for all participants.

Each participant then performed multiple trials until three valid recordings were obtained. A trial was considered valid if the participant (1) executed the landing–cutting sequence as instructed, (2) maintained balance without contralateral foot contact or extra steps, (3) refrained from hand support or hopping, and (4) demonstrated full marker visibility throughout the entire movement. Trials with partial marker occlusion were immediately discarded and reattempted to maintain data quality. To standardize landing foot placement, a designated landing target was marked on the force plate, and participants were instructed to land with the center of the non-dominant foot within this zone. Trials in which the landing occurred outside the predefined force-plate area (±10% boundary) were discarded and repeated to ensure consistency of ground reaction force measurements.

Although participants were instructed to perform the cutting maneuver at their maximum voluntary speed, additional steps were taken to verify speed consistency across trials. Because timing-gate devices were not used, video-based frame analysis was conducted using synchronized motion-capture recordings. Approach velocity was estimated from the displacement of the pelvis marker across sequential frames, and trials deviating more than approximately ±5% from the participant’s mean approach speed were repeated. This procedure minimized speed-related variability and prevented velocity inconsistencies from confounding joint moment outcomes.

All tasks were performed barefoot to reduce variability arising from shoe–surface interactions and to ensure optimal marker tracking. While this improved measurement precision, it does not fully reflect real sport-specific conditions; therefore, this was acknowledged as a methodological limitation.

The analyzed motion was divided into two phases: (1) the landing phase (from initial ground contact to toe-off) and (2) the stabilization phase (from the initial contact after the direction change to 3 s of quiet standing). The stabilization phase was defined as maintaining single-leg balance for 3 s without contralateral foot contact, additional steps, hand support, excessive trunk sway, or loss of marker visibility. A trial was considered failed if the participant touched the ground with the contralateral foot, performed extra steps, exhibited hopping or stumbling, or was unable to sustain balance for the full 3 s. Failed trials were discarded and repeated until three successful trials were obtained for each participant. The 90° turning angle was selected as it represents a sport-relevant maneuver requiring substantial postural stability, whereas larger turning angles have been shown to increase hip flexion and reduce knee loading [43,44]. The target angle was visually marked on the floor to standardize directional change, and participants were instructed to perform the maneuver at their maximum voluntary speed.

Figure 1 illustrates the reflective marker placement used for motion capture, and Figure 2 presents the sequence of the landing and 90° cutting task.

Figure 1.

Placement of reflective markers for motion capture.

Figure 2.

Sequential phases of the single-leg landing and 90° cutting task. Phase 4 illustrates the transition into the cutting direction, and the position shown represents the initial moment of the stabilization phase.

2.4. Exercise Intervention

This pilot intervention aimed to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and preliminary effects of a DST program using an inertial water load. The DST protocol was grounded in Bernstein’s Dynamic Systems Theory, as outlined by Davids et al. [45], and the DST framework proposed by Kang and Park [31].

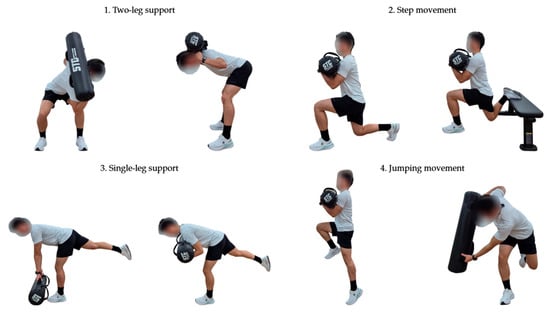

Training sessions were conducted twice weekly for 10 weeks (20 sessions total), with each session lasting approximately 50 min—comprising a 10-min warm-up, 30 min of main exercises, and a 10-min cool-down. Details of the training content and structure are presented in Table 2 and Figure 3.

Table 2.

Dynamic Stability Training (DST) program used in the pilot study.

Figure 3.

DST Program.

The program was designed as a progressive sequence emphasizing gradual increases in movement complexity and instability, rather than external load magnitude. Exercise progressions included bilateral stance, locomotor tasks, single-leg stance, jumping and acceleration/deceleration drills, and directional changes. Participants in the experimental group performed all exercises using a water-filled waterbag, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Waterbag.

The water load was regulated according to the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), following the procedure of Da Silva et al. [46]. The RPE-based load adjustment method was adapted from previous water-load training studies [47,48], which demonstrated its reliability and feasibility for instability-based resistance exercise. Based on these studies and our preliminary familiarization trials, the initial water load was standardized at approximately 8 kg, corresponding to a moderate intensity (RPE 6–7) on the Borg CR10 scale.

To ensure adherence to the intended training intensity, RPE was recorded at the end of every exercise set during all sessions. When a participant reported an RPE below the target range (<6), an additional 0.5–1.0 kg of water was added to the waterbag to increase instability and perceived effort. Conversely, if RPE exceeded the target range (>7), a small amount of water was removed to maintain moderate intensity. These adjustments were implemented immediately, and all RPE values and modifications were documented in session logs. During weeks 1–5, training intensity was maintained through this continual RPE monitoring. At the beginning of week 6, RPE was reassessed systematically, and the load was readjusted to maintain individualized moderate effort for the remaining training period.

The overall training program was standardized in terms of exercise type, frequency, and duration across all participants, while the water load was individualized according to RPE to ensure comparable relative effort. This mixed approach allowed consistent task exposure while accommodating inter-individual differences in motor control under unstable load conditions, consistent with prior water-based perturbation studies [45,46]. The overall parameters and session structure were established to evaluate the feasibility of implementing DST under controlled laboratory conditions and to refine the protocol for future randomized controlled trials.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (means ± standard deviations) were computed, and data normality was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Given the single-group repeated-measures design of this pilot study, temporal changes across the three time points (pre-, mid-, and post-intervention) were analyzed using a one-way repeated-measures ANOVA. When a significant main effect of time was found, Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons were conducted to identify specific differences. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

Effect sizes (η2) were calculated for all ANOVA results to assess the magnitude of observed changes. Additionally, Bayesian analysis was performed to complement the frequentist approach and to quantify the strength of evidence for either null or alternative hypotheses.

Because this was an exploratory pilot study without a priori power calculation or predefined effect-size assumptions, all statistical outcomes should be interpreted as preliminary indicators rather than confirmatory evidence. The analyses were intended to identify potential trends and estimate variance for future adequately powered trials, rather than to draw definitive causal inferences.

Furthermore, although repeated-measures ANOVA was appropriate for examining within-subject temporal changes in this design, we acknowledge that uncontrolled interacting factors (e.g., individual variability in movement strategies) may influence the results. Therefore, the statistical analyses are presented as exploratory and should be interpreted with caution.

For clarity, joint moments originally expressed along the X-, Y-, and Z-axes are presented using anatomical terminology: flexion/extension (X-axis), abduction/adduction (Y-axis), and internal/external rotation (Z-axis). The sign convention was defined such that positive values indicated flexion, abduction, and external rotation moments, whereas negative values indicated extension, adduction, and internal rotation moments. Peak joint moments were extracted for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

Changes in lower-limb joint moments during the single-leg landing and stabilization phases are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Changes in lower-limb joint moments during the single-leg landing phase.

Table 4.

Changes in lower-limb joint moments during the stabilization phase.

Significant time effects were observed for specific hip, knee, and ankle moments across both phases, as detailed in the following sections.

3.1. Single-Leg Landing Phase

Significant time effects were observed in several lower-limb joint moments during the single-leg landing phase (Table 3). The hip flexion/extension moment significantly increased from pre- to post-test (p = 0.003, η2 = 0.379, BF10 = 11.55), while the hip abduction/adduction moment also increased significantly across time points (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.495, BF10 = 89.31). In contrast, the hip external/internal rotation moment showed no significant change (p = 0.870, η2 = 0.012, BF10 = 0.21). Regarding the knee joint, the knee abduction/adduction moment significantly decreased over time (p = 0.002, η2 = 0.404, BF10 = 27.97), whereas knee flexion/extension (p = 0.135, η2 = 0.154, BF10 = 1.12) and knee rotation moments (p = 0.121, η2 = 0.161, BF10 = 0.82) remained unchanged. Similarly, for the ankle joint, the ankle abduction/adduction moment decreased significantly (p = 0.012, η2 = 0.309, BF10 = 10.51), while dorsiflexion/plantarflexion (p = 0.255, η2 = 0.108, BF10 = 0.49) and rotation moments (p = 0.306, η2 = 0.094, BF10 = 0.42) did not differ significantly across time points. Detailed Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons are provided in Appendix A Table A1. Overall, Bayesian results (BF10 > 3) provided moderate-to-strong evidence for several time-dependent changes, particularly in hip and knee joint moments. However, given the exploratory design, these patterns should be interpreted as potential indicators of altered load distribution, rather than definitive improvements in coordination or stability.

3.2. Stabilization Phase

Significant time effects were observed in several lower-limb joint moments during the stabilization phase (Table 4). Hip flexion moments decreased significantly from pre- to post-test (p = 0.001, η2 = 0.424, BF10 = 23.45). Hip external/internal rotation moments also showed a reduction over time (p = 0.038, η2 = 0.239), although the Bayesian evidence (BF10 = 2.60) indicates a suggestive rather than conclusive effect. Hip abduction/adduction moments did not change significantly (p = 0.478, η2 = 0.060, BF10 = 0.34). A large time effect was observed for the knee abduction/adduction moment (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.608, BF10 = 3013.17), representing the strongest evidence among all variables. No significant changes were detected in knee flexion (p = 0.460, η2 = 0.063, BF10 = 0.35) or rotation moments (p = 0.540, η2 = 0.050, BF10 = 0.30). For the ankle joint, ankle abduction/adduction moments decreased significantly (p = 0.011, η2 = 0.311, BF10 = 13.93), while dorsiflexion/plantarflexion (p = 0.670, η2 = 0.033, BF10 = 0.25) and rotation moments (p = 0.064, η2 = 0.205, BF10 = 1.68) showed no significant time effects. Full post hoc pairwise comparison results are presented in Appendix A Table A2. Overall, Bayesian results provided moderate-to-very strong evidence (BF10 > 3) for the observed reductions in hip flexion, knee abduction, and ankle abduction moments. However, variables with BF10 values between 1/3 and 3 (e.g., hip rotation) should be interpreted cautiously as exploratory trends rather than definitive changes. Given the pilot nature of the study, these joint-moment patterns are best understood as potential indicators of altered stabilization strategies, rather than direct evidence of improved postural stability.

4. Discussion

This pilot study examined the effects of DST using an inertial water load on lower-limb joint moments during single-leg landing and subsequent stabilization. The findings demonstrated distinct phase-specific adaptations in joint control strategies, suggesting that the intervention enhanced neuromuscular coordination and frontal-plane stability under dynamically unstable conditions.

Landing phase: Increases in hip flexion and abduction moments, together with a reduction in knee abduction moment, suggest a shift toward greater proximal contribution during load attenuation. While this pattern is commonly interpreted as enhanced impact absorption through hip-dominant strategies, it may also reflect compensatory adjustments rather than inherently optimal adaptations. Individuals often adopt different proximal-to-distal coordination patterns during landing, and increased hip moment generation can arise from neuromuscular compensation, task-specific constraints, or pre-existing movement tendencies. Therefore, these findings indicate an altered loading strategy rather than unequivocal improvement in landing mechanics [47].

The reduced knee abduction moment is consistent with a shift away from knee-dominant frontal-plane loading, which has been associated with decreased valgus stress in prior literature [20,43,48]. However, given the exploratory nature of this pilot trial and the variability in individual motor strategies, these interpretations should be made cautiously. Bayesian evidence was moderate for some variables (BF10 > 3) but inconclusive for others, and effects with BF10 values between 1/3 and 3 were not over-interpreted.

Unchanged hip and ankle rotation moments suggest that rotational control may require a longer intervention period or higher task complexity to elicit notable adaptation. Similarly, the stability of dorsiflexion/plantarflexion moments indicates that sagittal-plane control was maintained while perturbation-based training primarily influenced frontal- and transverse-plane loading strategies.

Stabilization phase: Reductions in hip flexion, hip rotation, and knee abduction moments, together with decreased ankle abduction moment, suggest improved postural stability through more efficient frontal-plane control of the lower limb. This interpretation aligns with previous findings that emphasize the role of frontal-plane moment regulation in maintaining dynamic knee alignment during stabilization tasks [20,22,43,49].

The strong evidence for the decrease in knee abduction moment (p < 0.001, η2 = 0.608, BF10 = 3013.17) indicates reduced valgus loading, which is generally associated with safer movement patterns and better neuromuscular control following landing or direction change maneuvers. These adaptations likely reflect enhanced coordination and co-activation of periarticular muscles, enabling improved control of dynamic alignment during the 3-s stabilization period.

Furthermore, the reductions in hip flexion and ankle abduction moments may indicate decreased reliance on compensatory proximal or distal strategies. This is consistent with previous work demonstrating that improved neuromuscular coordination leads to more balanced mechanical load distribution across the kinetic chain during stabilization tasks [20,44]. Similar improvements have been reported in perturbation-based balance training, where exposure to unpredictable multidirectional loads enhances joint coordination and reduces excessive joint-specific torque generation [26,27,28].

Integrated interpretation: Taken together, these findings indicate that DST using an inertial water load enhances joint coordination and dynamic balance control [28,50], particularly in the frontal and transverse planes [28,51,52,53]. Such improvements may contribute to a reduced risk of non-contact injuries—especially those associated with knee valgus and ankle instability—by promoting more efficient postural adjustments during complex sport-specific movements [1,10,16,19,54,55]. Because this pilot study was not powered to detect small-to-moderate effects and potential interacting factors could not be fully controlled, the statistical outcomes should be considered exploratory rather than confirmatory.

Given the exploratory nature of this pilot study and the absence of priori power calculation, the statistical findings should be interpreted as preliminary trends rather than definitive effects. Although repeated-measures ANOVA was suitable for examining within-subject temporal changes, uncontrolled interacting factors—such as individual variability in movement strategies—may have influenced the results. Therefore, all statistical interpretations should be viewed with caution and regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Limitations and implications: Several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this pilot study.

First, the small sample size and the absence of an active control group limit the generalizability of the results and prevent isolation of the specific effects of the inertial water-load intervention from general training or practice effects.

Second, all biomechanical tasks were performed barefoot to improve marker visibility and reduce variability from shoe–surface interactions. Although this enhanced measurement precision, it substantially limits ecological validity, and it remains unclear whether the observed adaptations would transfer to shod or sport-specific footwear conditions. Future studies should directly compare barefoot and shod performance to determine the robustness of these findings.

Third, electromyographic (EMG) data were not collected, preventing verification of whether changes in joint moments were accompanied by corresponding neuromuscular activation patterns. Including EMG measures in future work will be critical for identifying the underlying neuromuscular mechanisms of adaptation.

Fourth, no performance-based outcome measures (e.g., jump height, reactive agility, movement efficiency) were included. As such, it is not possible to determine whether biomechanical improvements translated into meaningful functional enhancements.

Fifth, the study examined only immediate post-intervention changes. The sustainability of these adaptations—whether they are retained over time or require continued training—is unknown. Long-term follow-up studies are needed to evaluate retention and decay of training effects.

Finally, the transferability of the observed biomechanical adaptations to real-world or sport-specific contexts remains uncertain. Sport movements typically involve higher velocities, greater unpredictability, and variable environmental constraints, and future studies should evaluate the applicability of dynamic stability training under sport-relevant conditions.

Conclusion: Ten weeks of Dynamic Stability Training (DST) using an inertial water load produced measurable changes in lower-limb joint moments during landing and stabilization. These patterns indicate shifts in joint-loading strategies rather than definitive improvements in stability or coordination. As exploratory findings from a small pilot sample, the results suggest that water-based perturbation training may influence movement strategies under unstable conditions, warranting further investigation in controlled, large-scale studies.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study identified distinct changes in lower-limb joint moments during single-leg landing and stabilization following a 10-week DST intervention using an inertial water load. The observed reductions in knee and ankle abduction moments, along with alterations in hip flexion and rotation moments, reflect potential adjustments in landing and stabilization strategies. However, these biomechanical adaptations cannot be interpreted as definitive improvements in stability or neuromuscular control, and compensatory mechanisms cannot be ruled out. Given the exploratory nature, small sample size, and absence of a control group, these findings should be considered hypothesis-generating. Future research—including randomized controlled trials with larger cohorts, EMG assessment, and performance outcomes—is required to clarify the neuromuscular mechanisms underlying these adaptations and determine their relevance to sport-specific movement and injury risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.P., C.K.L., M.J.S., and J.Y.L.; methodology, I.B.P. and C.K.L.; software, M.J.S. and J.Y.L.; validation, M.J.S. and J.Y.L.; formal analysis, M.J.S. and J.Y.L.; investigation, J.Y.L.; data curation, J.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.L.; writing—review and editing, I.B.P., C.K.L., M.J.S., and J.Y.L.; visualization, J.Y.L.; supervision, I.B.P., C.K.L., M.J.S., and J.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Public Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: P01-202504-01-008; approval date: 7 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at the following DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16827110 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Il Bong Park and Chae Kwan Lee for their invaluable guidance and continuous encouragement throughout this study. The authors also thank Min Ji Son for her expert advice and support in the experimental design and research process. This study was based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation and was made possible through the collaboration and dedication of all contributors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Min Ji Son was employed by JEIOS Inc.; however, this research was conducted without any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACL | Anterior Cruciate Ligament |

| COP | Center of Pressure |

| CR10 | Category Ratio 10 Scale |

| DST | Dynamic Stability Training |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| PBT | Perturbation-Based Training |

| RPE | Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| SMR | Self-Myofascial Release |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons for the Single-Leg Landing Phase

Table A1.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc pairwise comparison results for joint moments during the single-leg landing phase.

Table A1.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc pairwise comparison results for joint moments during the single-leg landing phase.

| Variable | Pre-Mid | Mid-Post | Pre-Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip flexion/extension moment | 0.208 | 0.136 | 0.021 |

| Hip abduction/adduction moment | 0.018 | 1.000 | 0.002 |

| Hip external/internal rotation moment | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Knee flexion/extension moment | 0.541 | 0.972 | 0.418 |

| Knee abduction/adduction moment | 0.361 | 0.123 | 0.005 |

| Knee external/internal rotation moment | 0.199 | 1.000 | 0.468 |

| Ankle dorsiflexion/plantarflexion moment | 0.517 | 1.000 | 0.773 |

| Ankle abduction/adduction moment | 0.059 | 1.000 | 0.056 |

| Ankle external/internal rotation moment | 0.384 | 1.000 | 0.867 |

Appendix A.2. Post Hoc Pairwise Comparisons for the Stabilization Phase

Table A2.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc pairwise comparison results for joint moments during the stabilization phase.

Table A2.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc pairwise comparison results for joint moments during the stabilization phase.

| Variable | Pre-Mid | Mid-Post | Pre-Post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip flexion/extension moment | 0.002 | 1.000 | 0.019 |

| Hip abduction/adduction moment | 0.846 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Hip external/internal rotation moment | 1.000 | 0.247 | 0.059 |

| Knee flexion/extension moment | 0.966 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Knee abduction/adduction moment | 0.001 | 0.969 | 0.001 |

| Knee external/internal rotation moment | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.783 |

| Ankle dorsiflexion/plantarflexion moment | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Ankle abduction/adduction moment | 0.187 | 1.000 | 0.036 |

| Ankle external/internal rotation moment | 0.734 | 0.801 | 0.056 |

References

- Waldén, M.; Krosshaug, T.; Bjørneboe, J.; Andersen, T.E.; Faul, O.; Hägglund, M. Three distinct mechanisms predominate in non-contact anterior cruciate ligament injuries in male professional football players: A systematic video analysis of 39 cases. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1452–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeow, C.H.; Lee, P.V.; Goh, J.C. Effect of landing height on frontal plane kinematics, kinetics and energy dissipation at lower extremity joints. J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 1967–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devita, P.A.U.L.; Skelly, W.A. Effect of landing stiffness on joint kinetics and energetics in the lower extremity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1992, 24, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Bates, B.T.; Dufek, J.S. Contributions of lower extremity joints to energy dissipation during landings. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krosshaug, T.; Nakamae, A.; Boden, B.P.; Engebretsen, L.; Smith, G.; Slauterbeck, J.R.; Hewett, T.E.; Bahr, R. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury in basketball: Video analysis of 39 cases. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padua, D.A.; DiStefano, L.J.; Beutler, A.I.; de la Motte, S.J.; DiStefano, M.J.; Marshall, S.W. The Landing Error Scoring System as a Screening Tool for an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury-Prevention Program in Elite-Youth Soccer Athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2015, 50, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schot, P.K.; Bates, B.T.; Dufek, J.S. Bilateral performance symmetry during drop landing: A kinetic analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besier, T.F.; Lloyd, D.G.; Ackland, T.R.; Cochrane, J.L. Anticipatory effects on knee joint loading during running and cutting maneuvers. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1176–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, T. Biomechanical mechanisms and prevention strategies of knee joint injuries on football: An in-depth analysis based on athletes’ movement patterns. MCB 2024, 21, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokochi, Y.; Shultz, S.J. Mechanisms of noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. J. Athl. Train. 2008, 43, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, B.P.; Dean, G.S.; Feagin, J.A.; Garrett, W.E. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics 2000, 23, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, D.; Melnyk, M.; Gollhofer, A. Gender and fatigue have influence on knee joint control strategies during landing. Clin. Biomech. 2009, 24, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppänen, M.; Pasanen, K.; Kujala, U.M.; Vasankari, T.; Kannus, P.; Äyrämö, S.; Krosshaug, T.; Bahr, R.; Avela, J.; Perttunen, J.; et al. Stiff Landings Are Associated With Increased ACL Injury Risk in Young Female Basketball and Floorball Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadi, S.; Ebrahimi, I.; Salavati, M.; Dadgoo, M.; Jafarpisheh, A.S.; Rezaeian, Z.S. Attentional Demands of Postural Control in Chronic Ankle Instability, Copers and Healthy Controls: A Controlled Cross-sectional Study. Gait Posture 2020, 79, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.D.; Stewart, E.M.; Macias, D.M.; Chander, H.; Knight, A.C. Individuals with chronic ankle instability exhibit dynamic postural stability deficits and altered unilateral landing biomechanics: A systematic review. Phys. Ther. Sport. 2019, 37, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, B.L.; De La Motte, S.; Linens, S.; Ross, S.E. Ankle instability is associated with balance impairments: A meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1048–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazulak, B.T.; Hewett, T.E.; Reeves, N.P.; Goldberg, B.; Cholewicki, J. Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: A prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Son, S.J.; Seeley, M.K.; Hopkins, J.T. Altered movement strategies during jump landing/cutting in patients with chronic ankle instability. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2019, 29, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, E.; Shiyko, M.P.; Ford, K.R.; Myer, G.D.; Hewett, T.E. Biomechanical Deficit Profiles Associated with ACL Injury Risk in Female Athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, C.D.; Sigward, S.M.; Powers, C.M. Limited hip and knee flexion during landing is associated with increased frontal plane knee motion and moments. Clin. Biomech. 2010, 25, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.S. Change-of-Direction Biomechanics: Is What’s Best for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Prevention Also Best for Performance? Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, N.; Morrison, S.; Van Lunen, B.L.; Onate, J.A. Landing technique affects knee loading and position during athletic tasks. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2012, 15, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, A.; Danells, C.J.; Inness, E.L.; Musselman, K.; Salbach, N.M. A survey of Canadian healthcare professionals’ practices regarding reactive balance training. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021, 37, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, Y.; Brodie, M.A.; Sturnieks, D.L.; Hicks, C.; Carter, H.; Toson, B.; Lord, S.R. Exposure to trips and slips with increasing unpredictability while walking can improve balance recovery responses with minimum predictive gait alterations. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerards, M.H.G.; McCrum, C.; Mansfield, A.; Meijer, K. Perturbation-based balance training for falls reduction among older adults: Current evidence and implications for clinical practice. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2017, 17, 2294–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrum, C.; Bhatt, T.S.; Gerards, M.H.G.; Karamanidis, K.; Rogers, M.W.; Lord, S.R.; Okubo, Y. Perturbation-based balance training: Principles, mechanisms and implementation in clinical practice. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 1015394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martelli, D.; Kang, J.; Aprigliano, F.; Staudinger, U.M.; Agrawal, S.K. Acute Effects of a Perturbation-Based Balance Training on Cognitive Performance in Healthy Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 688519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, S.; Mandla-Liebsch, M.; Mersmann, F.; Arampatzis, A. Exercise of Dynamic Stability in the Presence of Perturbations Elicit Fast Improvements of Simulated Fall Recovery and Strength in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Sports Act. Living 2020, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, A.; Bozzato, M.; Rotundo, L.; Zullo, G.; De Vito, G.; Paoli, A.; Marcolin, G. Multimodal training protocols on unstable rather than stable surfaces better improve dynamic balance ability in older adults. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.E.; Hsu, W.L. Effects of Dynamic Perturbation-Based Training on Balance Control of Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Park, I. Effects of Instability Neuromuscular Training Using an Inertial Load of Water on the Balance Ability of Healthy Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Park, I.; Ha, M.S. Effect of dynamic neuromuscular stabilization training using the inertial load of water on functional movement and postural sway in middle-aged women: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wezenbeek, E.; Verhaeghe, L.; Laveyne, K.; Ravelingien, L.; Witvrouw, E.; Schuermans, J. The Effect of Aquabag Use on Muscle Activation in Functional Strength Training. J. Sport. Rehabil. 2022, 31, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julious, S.A. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharm. Stat. 2005, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertzog, M.A. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2008, 31, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, A.L.; Julious, S.A.; Cooper, C.L.; Campbell, M.J. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2016, 25, 1057–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigward, S.; Powers, C.M. The influence of experience on knee mechanics during side-step cutting in females. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrysomallis, C. Balance ability and athletic performance. Sports Med. 2011, 41, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verniba, D.; Vescovi, J.D.; Hood, D.A.; Gage, W.H. The analysis of knee joint loading during drop landing from different heights and under different instruction sets in healthy males. Sports Med.-Open 2017, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinsurin, K.; Vachalathiti, R.; Srisangboriboon, S.; Richards, J. Knee joint coordination during single-leg landing in different directions. Sports Biomech. 2020, 19, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyama, M.; Nosaka, K. Influence of surface on muscle damage and soreness induced by consecutive drop jumps. J. Strengt Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Melick, N.; Meddeler, B.M.; Hoogeboom, T.J.; Nijhuis-van der Sanden, M.W.G.; van Cingel, R.E.H. How to determine leg dominance: The agreement between self-reported and observed performance in healthy adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigward, S.M.; Cesar, G.M.; Havens, K.L. Predictors of Frontal Plane Knee Moments During Side-Step Cutting to 45 and 110 Degrees in Men and Women: Implications for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. Clin. J. Sport. Med. 2015, 25, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, K.L.; Sigward, S.M. Joint and segmental mechanics differ between cutting maneuvers in skilled athletes. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, K.; Glazier, P.; Araújo, D.; Bartlett, R. Movement systems as dynamical systems: The functional role of variability and its implications for sports medicine. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, D.T.C.; Silva, K.D.S.; Ahmadi, S.; Teixeira, L.F.M. Indoor-cycling classes: Is there a difference between what instructors predict and what practitioners practice? JPES 2019, 19, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, C.K. The Effect of Inertial Load of Water on Lower Muscle Activation and COP (Center of Pressure) during Single-leg Landing Accompanied by Trunk Rotation. KJAB 2024, 34, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.J.; Cone, J.C.; Tritsch, A.J.; Pye, M.L.; Montgomery, M.M.; Henson, R.A.; Shultz, S.J. Changes in drop-jump landing biomechanics during prolonged intermittent exercise. Sports Health 2014, 6, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, C.M. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: A biomechanical perspective. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Kang, S.; Park, I.B. Comparison of Dynamic Muscle Activation during Fente Execution in Fencing Between Wearing Weighted and Waterbag Vests. KJAB 2023, 33, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuter, V.H.; de Jonge, X.A.J. Proximal and distal contributions to lower extremity injury: A review of the literature. Gait Posture 2012, 36, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Martel, V.; Santuz, A.; Bohm, S.; Arampatzis, A. Neuromechanics of Dynamic Balance Tasks in the Presence of Perturbations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 560630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazulak, B.T.; Hewett, T.E.; Reeves, N.P.; Goldberg, B.; Cholewicki, J. The effects of core proprioception on knee injury: A prospective biomechanical-epidemiological study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donelon, T.A.; Dos’ Santos, T.; Pitchers, G.; Brown, M.; Jones, P.A. Biomechanical determinants of knee joint loads associated with increased anterior cruciate ligament loading during cutting: A systematic review and technical framework. Sports Med. Open 2020, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larwa, J.; Stoy, C.; Chafetz, R.S.; Boniello, M.; Franklin, C. Stiff landings, core stability, and dynamic knee valgus: A systematic review on documented anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in male and female athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).