An Agricultural Hybrid Carbon Model for National-Scale SOC Stock Spatial Estimation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

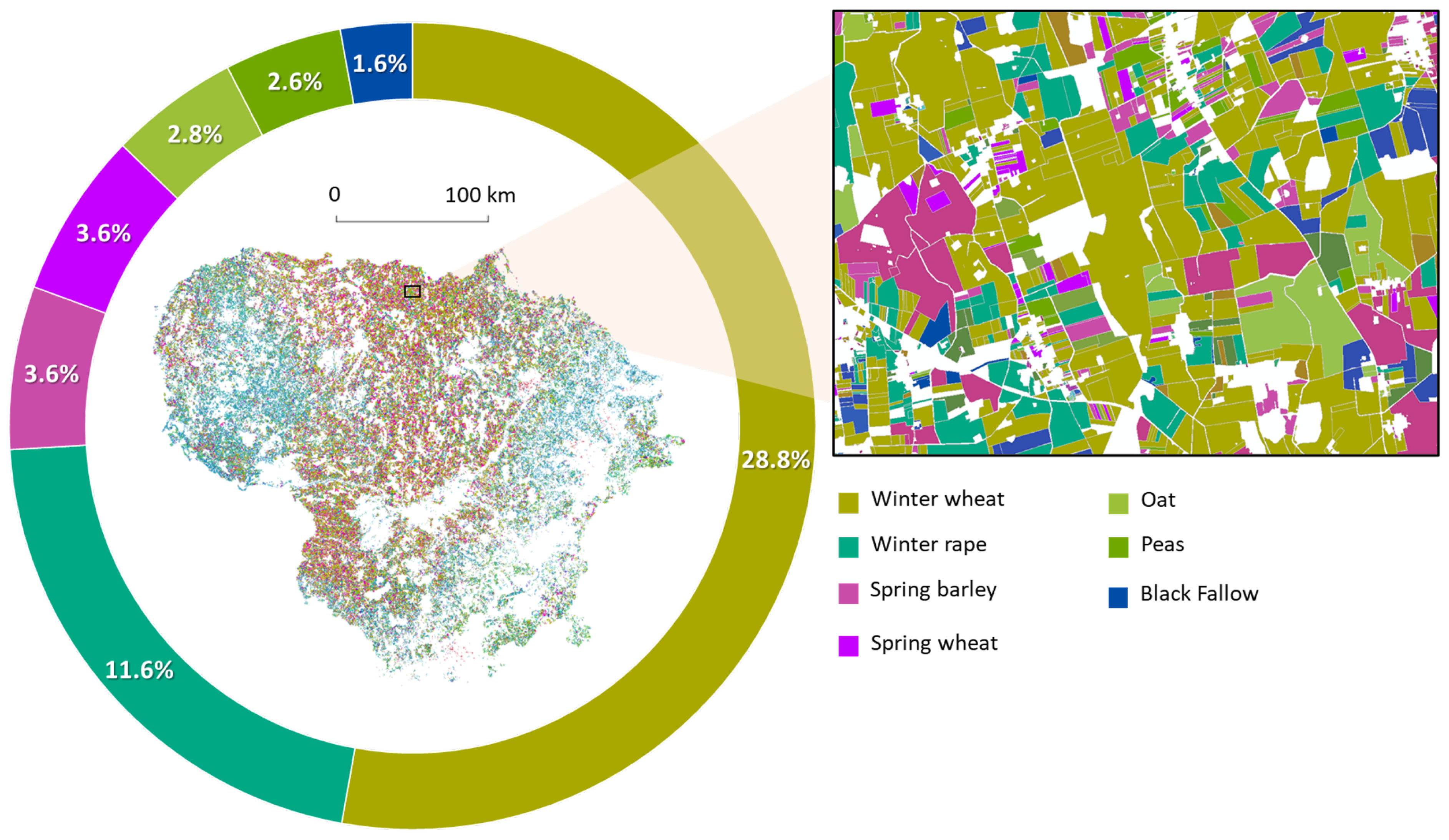

2.1. Study Area

2.2. The Hybrid AI-Driven Physical Process-Based Modeling Approach

2.3. Input Data Sources

2.3.1. Land Use Land Cover Dataset

2.3.2. Climate Dataset

2.3.3. Soil Dataset

2.3.4. Plant Cover and Carbon Input Dataset

2.4. The Projected SOC Stocks and Climate Change Scenario Design

- Absolute SOC sequestration (ASR)ASR is expressed as the change in SOC stocks over time relative to a baseline period . It can be calculated for both BAU and CCS scenarios and may be either positive or negative:where refers to the final SOC stocks after the defined period of 20 years and represents the SOC stocks at the baseline period.

- Relative SOC sequestration (RCR)RCR is expressed as the change in SOC stocks over time relative to the BAU scenario. Similar to ASR, it can be either positive or negative and is determined bywhere refers to the final SOC stocks after the defined period of 20 years and refers to the final SOC stocks under the BAU management at the end of the considered period of 20 years.

3. Results

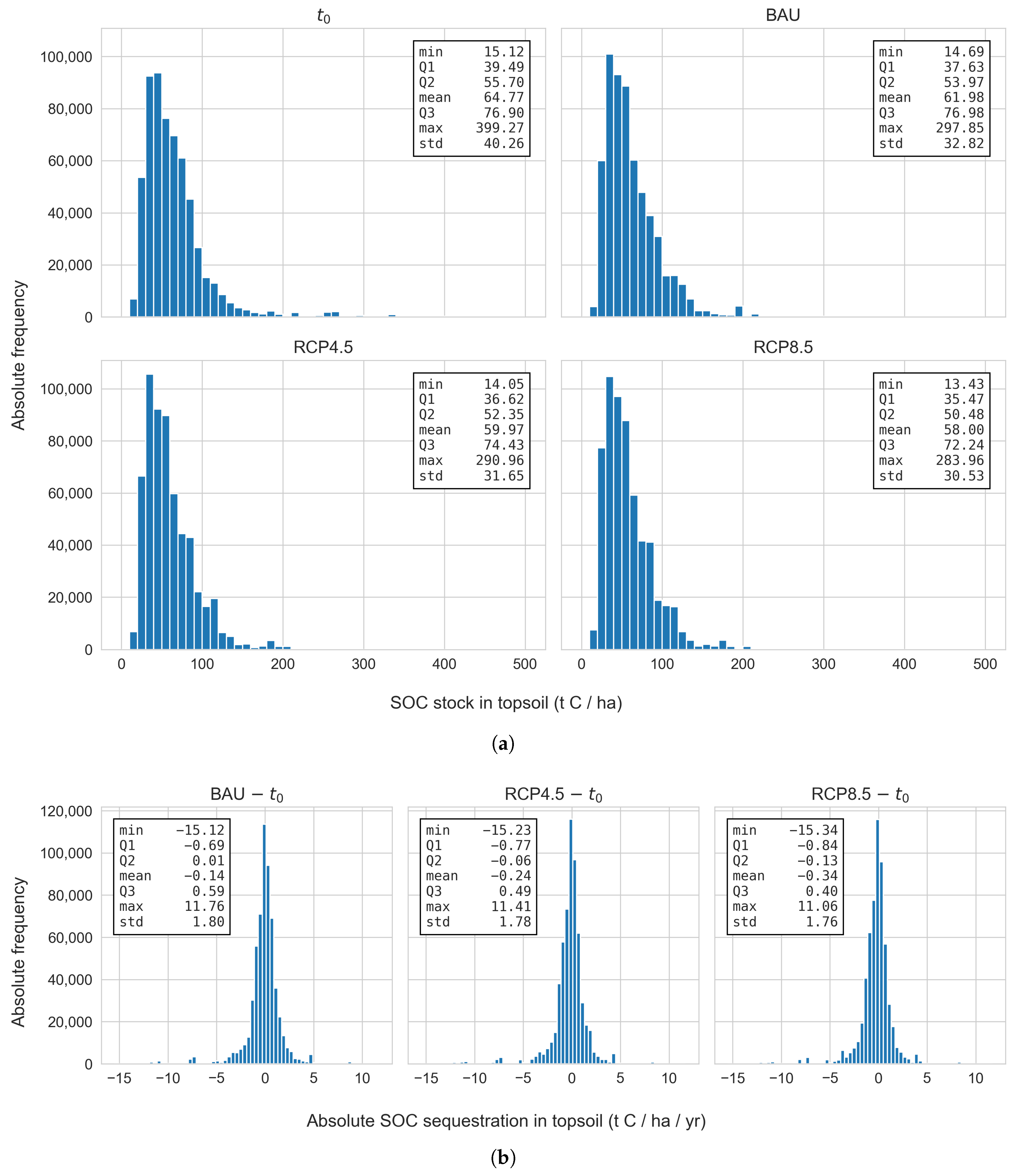

3.1. The Current Situation of Lithuanian Croplands Related to SOC Stock

- 1st simulation: low-resolution input layersThis simulation utilized coarse-spatial-resolution input data, including SOC and clay content at 250m resolution from SoilGrids, LULC data from the Corine dataset, and climate data from the ERA-5 dataset.

- 2nd simulation: high-resolution input layersIn this simulation, the high-spatial-resolution input data layers were employed, namely, the 10m for SOC and clay content, LULC data from the IACS dataset, and climate data from TerraClimate dataset.

3.2. The Spatial Projections of SOC Sequestration Under the Climate Change Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. The Rationale for RothC Selection and the Importance of Hybrid Approaches Incorporating High-Resolution Input Layers

4.2. Understanding the Impact of Climate Change Scenarios on SOC Estimation

4.3. Operational Relevance for National Soil-Carbon Monitoring

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BAU | Buisiness as Usual |

| CORDEX | Coordinated Regional Climate Downscaling |

| CCS | Climate Change Scenarios |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast |

| EO | Earth Observation |

| EU | European Union |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| IACS | Integrated Administration Control System |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LULC | Land Use Land Cover |

| LULUCF | Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry |

| NPP | Net Primary Productivity |

| RCP | Representative Concectration Pathways |

| SDC | Soil Data Cube |

| SOC | Soil Organic Carbon |

References

- Batjes, N. Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 1996, 47, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Carbon sequestration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2007, 363, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigini, Y.; Panagos, P. Assessment of soil organic carbon stocks under future climate and land cover changes in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 557–558, 838–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, N.; Boody, G.; Broussard, W.; Glover, J.D.; Keeney, D.; McCown, B.H.; McIsaac, G.; Muller, M.; Murray, H.; Neal, J.; et al. Sustainable Development of the Agricultural Bio-Economy. Science 2007, 316, 1570–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; McConnell, C.; Coleman, K.; Cox, P.; Falloon, P.; Jenkinson, D.; Powlson, D. Global climate change and soil carbon stocks; predictions from two contrasting models for the turnover of organic carbon in soil. Glob. Change Biol. 2004, 11, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkels, F.; Cammeraat, L.; Kuhn, N. The fate of soil organic carbon upon erosion, transport and deposition in agricultural landscapes — A review of different concepts. Geomorphology 2014, 226, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doetterl, S.; Berhe, A.A.; Nadeu, E.; Wang, Z.; Sommer, M.; Fiener, P. Erosion, deposition and soil carbon: A review of process-level controls, experimental tools and models to address C cycling in dynamic landscapes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2016, 154, 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Montanarella, L.; Barbero, M.; Schneegans, A.; Aguglia, L.; Jones, A. Soil priorities in the European Union. Geoderma Reg. 2022, 29, e00510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, D.; Ballabio, C.; Lugato, E.; Fasiolo, M.; Jones, A.; Panagos, P. Soil organic carbon stocks in European croplands and grasslands: How much have we lost in the past decade? Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 30, 16992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padarian, J.; Stockmann, U.; Minasny, B.; McBratney, A. Monitoring changes in global soil organic carbon stocks from space. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 281, 113260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament: Directorate-General for Internal Policies of the Union; McDonald, H.; Frelih-Larsen, A.; Lóránt, A.; Duin, L.; Pyndt Andersen, S.; Costa, G.; Bradley, H. Carbon Farming – Making Agriculture Fit For 2030; Publications Office of the European Parliament: Luxembourg, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Broothaerts, N.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; De Rosa, D.; Borrelli, P.; Liakos, L.; Vieira, D.; Van Eynde, E.; Arias Navarro, C.; et al. How the EU Soil Observatory is providing solid science for healthy soils. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 75, 13507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.; Monger, C.; Nave, L.; Smith, P. The role of soil in regulation of climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2021, 376, 20210084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesfin, S.; Gebresamuel, G.; Haile, M.; Zenebe, A. Modelling spatial and temporal soil organic carbon dynamics under climate and land management change scenarios, northern Ethiopia. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 72, 1298–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beillouin, D.; Corbeels, M.; Demenois, J.; Berre, D.; Boyer, A.; Fallot, A.; Feder, F.; Cardinael, R. A global meta-analysis of soil organic carbon in the Anthropocene. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Soussana, J.; Angers, D.; Schipper, L.; Chenu, C.; Rasse, D.P.; Batjes, N.H.; van Egmond, F.; McNeill, S.; Kuhnert, M.; et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 26, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Smith, J.; Powlson, D.; McGill, W.; Arah, J.; Chertov, O.; Coleman, K.; Franko, U.; Frolking, S.; Jenkinson, D.; et al. A comparison of the performance of nine soil organic matter models using datasets from seven long-term experiments. Geoderma 1997, 81, 153–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Guenet, B.; Wang, Y.L.; Ciais, P. Global simulation and evaluation of soil organic matter and microbial carbon and nitrogen stocks using the microbial decomposition model ORCHIMIC v2.0. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, e2020GB006836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Elliott, J.; Kelly, D.; Arneth, A.; Balkovic, J.; Ciais, P.; Deryng, D.; Folberth, C.; Hoek, S.; Izaurralde, R.C.; et al. The Global Gridded Crop Model Intercomparison phase 1 simulation dataset. Sci. Data 2019, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugato, E.; Berti, A. Potential carbon sequestration in a cultivated soil under different climate change scenarios: A modelling approach for evaluating promising management practices in north-east Italy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, P.; Smith, P.; Bradley, R.I.; Milne, R.; Tomlinson, R.; Viner, D.; Livermore, M.; Brown, T. RothCUK –A dynamic modelling system for estimating changes in soil C from mineral soils at 1-km resolution in the UK. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 22, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witing, F.; Gebel, M.; Kurzer, H.J.; Friese, H.; Franko, U. Large-scale integrated assessment of soil carbon and organic matter-related nitrogen fluxes in Saxony (Germany). J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinge, G.; Surampalli, R.Y.; Goyal, M.K.; Gupta, B.B.; Chang, X. Soil carbon and its associate resilience using big data analytics: For food Security and environmental management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 169, 120823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarinas, N.; Tziolas, N.; Zalidis, G. Improved Estimations of Nitrate and Sediment Concentrations Based on SWAT Simulations and Annual Updated Land Cover Products from a Deep Learning Classification Algorithm. Isprs Int. J. -Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, E.; Chen, J.; Peng, Y.; Yan, G.; Zhao, Y. Modelling the spatiotemporal dynamics of cropland soil organic carbon by integrating process-based models differing in structures with machine learning. J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 2816–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarinas, N.; Tsakiridis, N.; Kalopesa, E.; Zalidis, G. Soil Loss Estimation by Water Erosion in Agricultural Areas Introducing Artificial Intelligence Geospatial Layers into the RUSLE Model. Land 2024, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Zhang, X.; Lu, F.; Peng, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, Y. Integration of a process-based model into the digital soil mapping improves the space-time soil organic carbon modelling in intensively human-impacted area. Geoderma 2022, 409, 115599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Mulder, V.L.; Chen, S.; Deng, X.; Yang, L. Using process-oriented model output to enhance machine learning-based soil organic carbon prediction in space and time. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 170778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Gross Value Added and Income by A*10 Industry Breakdowns. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/bookmark/fa6f7d3f-f0e2-4b49-8aaf-0f5049fa699f?lang=en (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Coleman, K.; Jenkinson, D.S. RothC-26.3–A Model for the turnover of carbon in soil. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondini, C.; Cayuela, M.L.; Sinicco, T.; Fornasier, F.; Galvez, A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A. Modification of the RothC model to simulate soil C mineralization of exogenous organic matter. Biogeosciences 2017, 14, 3253–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, S.; Beckage, B. Soil carbon sequestration through regenerative agriculture in the U.S. state of Vermont. PLoS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarinas, N.; Tsakiridis, N.L.; Kokkas, S.; Kalopesa, E.; Zalidis, G.C. Soil Data Cube and Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Generating National-Scale Topsoil Thematic Maps: A Case Study in Lithuanian Croplands. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, C.A.; Mueller, M.; Trumbore, S.E. Models of soil organic matter decomposition: The SoilR package, version 1.0. Geosci. Model Dev. 2012, 5, 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, G.; Di Paolo, L.; Luotto, I.; Omuto, C.; Mainka, M.; Viatkin, K.; Yigini, Y. Global Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Potential Map (GSOCseq v1.1) – Technical Manual; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.; Dobrowski, S.; Parks, S.; Hegewisch, K. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 170191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengl, T. Soil bulk density (fine earth) 10 x kg / m-cubic at 6 standard depths (0, 10, 30, 60, 100 and 200 cm) at 250 m resolution. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Poggio, L.; de Sousa, L.M.; Batjes, N.H.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Kempen, B.; Ribeiro, E.; Rossiter, D. SoilGrids 2.0: Producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 2021, 7, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Mu, X.; Ruan, G.; Gao, Z.; Li, L.; Yan, G. Estimating fractional vegetation cover and the vegetation index of bare soil and highly dense vegetation with a physically based method. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 58, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieth, H. Modeling the Primary Productivity of the World. In Primary Productivity of the Biosphere; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1975; pp. 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Minasny, B.; Viaud, V.; Walter, C.; Malone, B.; McBratney, A. Modelling the Whole Profile Soil Organic Carbon Dynamics Considering Soil Redistribution under Future Climate Change and Landscape Projections over the Lower Hunter Valley, Australia. Land 2023, 12, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, S.; Grados, D.; Møller, A.B.; de Carvalho Gomes, L.; Beucher, A.M.; Giannini-Kurina, F.; de Jonge, L.W.; Greve, M.H. Unleashing the sequestration potential of soil organic carbon under climate and land use change scenarios in Danish agroecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 166921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service. CORDEX Regional Climate Model Data on Single Levels. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, A.; Sauzet, O.; Matter, A.; Boivin, P. Soil organic carbon content and soil structure quality of clayey cropland soils: A large-scale study in the Swiss Jura region. Soil Use Manag. 2023, 39, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ren, C.; Yang, G.; Han, X.; Ren, G.; Feng, Y. Relationship between Soil Organic Carbon Stocks and Clay Content under Different Climatic Conditions in Central China. Forests 2018, 9, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krinner, G.; Viovy, N.; de Noblet-Ducoudré, N.; Ogée, J.; Polcher, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ciais, P.; Sitch, S.; Prentice, I.C. A dynamic global vegetation model for studies of the coupled atmosphere-biosphere system. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2005, 19, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Williams, J.R.; Gassman, P.W.; Baffaut, C.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Jeong, J.; Kiniry, J.R. EPIC and APEX: Model Use, Calibration, and Validation. Trans. Asabe 2012, 55, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Gottschalk, P.; Bellarby, J.; Chapman, S.; Lilly, A.; Towers, W.; Bell, J.; Coleman, K.; Nayak, D.; Richards, M.; et al. Estimating changes in Scottish soil carbon stocks using ECOSSE. I. Model description and uncertainties. Clim. Res. 2010, 45, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J. The CENTURY model. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCown, R.; Hammer, G.; Hargreaves, J.; Holzworth, D.; Freebairn, D. APSIM: A novel software system for model development, model testing and simulation in agricultural systems research. Agric. Syst. 1996, 50, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liski, J.; Palosuo, T.; Peltoniemi, M.; Sievänen, R. Carbon and decomposition model Yasso for forest soils. Ecol. Model. 2005, 189, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, A.; Giussani, A.; Sanna, M.; Fumagalli, M.; Carozzi, M.; Lodovico; Alfieri; Brenna, S.; Acutis, M. The ARMOSA simulation crop model: Overall features, calibration and validation results. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 2013, 3, 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Goglio, P.; Smith, W.N.; Grant, B.B.; Desjardins, R.L.; McConkey, B.G.; Campbell, C.A.; Nemecek, T. Accounting for soil carbon changes in agricultural life cycle assessment (LCA): A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geremew, B.; Tadesse, T.; Bedadi, B.; Gollany, H.T.; Tesfaye, K.; Aschalew, A.; Tilaye, A.; Abera, W. Evaluation of RothC model for predicting soil organic carbon stock in north-west Ethiopia. Environ. Challenges 2024, 15, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, G.; Jangir, A.; Francaviglia, R. Modeling soil organic carbon dynamics under shifting cultivation and forests using Rothc model. Ecol. Model. 2019, 396, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadoux, A.M.C.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Lark, R.M.; Lagacherie, P.; Bouma, J.; Mulder, V.L.; Libohova, Z.; Yang, L.; McBratney, A.B. Ten challenges for the future of pedometrics. Geoderma 2021, 401, 115155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebari, A.; Álvaro Fuentes, J.; Pardo, G.; Almagro, M.; del Prado, A. Estimating soil organic carbon changes in managed temperate moist grasslands with RothC. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzali, S.F.; Azad, B.; Golabi, M.H.; Francaviglia, R. Using RothC Model to Simulate Soil Organic Carbon Stocks under Different Climate Change Scenarios for the Rangelands of the Arid Regions of Southern Iran. Water 2019, 11, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnagirytė-Kabašinskienė, I.; Žemaitis, P.; Armolaitis, K.; Stakėnas, V.; Urbaitis, G. Soil Organic Carbon Stocks in Afforested Agricultural Land in Lithuanian Hemiboreal Forest Zone. Forests 2021, 12, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Dechow, R. The legacy of one hundred years of climate change for organic carbon stocks in global agricultural topsoils. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Economic and Social Committee. Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on the proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Soil Monitoring and Resilience (Soil Monitoring Law) (COM(2023) 416 final — 2023/0232 (COD)). The Official Journal of the European Union. OJ C, C/2024/887, 2024. EESC 2023/03275; CELEX: 52023AE3275. 2024. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/C/2024/887/oj (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Batjes, N.H.; Ceschia, E.; Heuvelink, G.B.; Demenois, J.; le Maire, G.; Cardinael, R.; Arias-Navarro, C.; van Egmond, F. Towards a modular, multi-ecosystem monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) framework for soil organic carbon stock change assessment. Carbon Manag. 2024, 15, 2410812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummitt, C.D.; Mathers, C.A.; Keating, R.A.; O’Leary, K.; Easter, M.; Friedl, M.A.; DuBuisson, M.; Campbell, E.E.; Pape, R.; Peters, S.J.; et al. Solutions and insights for agricultural monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) from three consecutive issuances of soil carbon credits. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Zhang, X.; Atkinson, P.M.; Stein, A.; Li, L. Geoscience-aware deep learning: A new paradigm for remote sensing. Sci. Remote Sens. 2022, 5, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating Scientific Knowledge with Machine Learning for Engineering and Environmental Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, W.; Guan, K.; Peng, B.; Xu, S.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Till, J.; Jia, X.; Jiang, C.; et al. Knowledge-guided machine learning can improve carbon cycle quantification in agroecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G.E. Physics Informed Deep Learning (Part II): Data-driven Discovery of Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. arXiv 2017, arXiv:cs.AI/1711.10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Crowell, S.; Luo, Y.; Moore, B., III. Model structures amplify uncertainty in predicted soil carbon responses to climate change. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsakiridis, N.; Samarinas, N.; Kalopesa, E.; Zalidis, G. Cognitive Soil Digital Twin for Monitoring the Soil Ecosystem: A Conceptual Framework. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Average SOC Stocks ( | Average ASR ( | Average RSR ( | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Class | N Parcels | BAU | RCP 4.5 | RCP 8.5 | BAU | RCP 4.5 | RCP 8.5 | RCP 4.5–BAU | RCP 8.5–BAU | |

| All | 598,460 | 64.77 | 61.98 | 59.97 | 58.00 | |||||

| Winter wheat | 163,853 | 65.45 | 63.88 | 61.82 | 59.79 | |||||

| Winter rape | 52,354 | 68.38 | 66.72 | 64.63 | 62.57 | |||||

| Spring barley | 30,101 | 66.43 | 64.65 | 62.58 | 60.53 | |||||

| Spring wheat | 35,199 | 63.99 | 60.42 | 58.45 | 56.52 | |||||

| Oat | 29,222 | 60.44 | 57.54 | 55.66 | 53.81 | |||||

| Peas | 19,456 | 65.59 | 63.04 | 61.02 | 59.02 | |||||

| Black fallow | 18,911 | 63.85 | 61.15 | 59.14 | 57.16 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samarinas, N.; Tsakiridis, N.L.; Kalopesa, E.; Tziolas, N. An Agricultural Hybrid Carbon Model for National-Scale SOC Stock Spatial Estimation. Environments 2025, 12, 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12120477

Samarinas N, Tsakiridis NL, Kalopesa E, Tziolas N. An Agricultural Hybrid Carbon Model for National-Scale SOC Stock Spatial Estimation. Environments. 2025; 12(12):477. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12120477

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamarinas, Nikiforos, Nikolaos L. Tsakiridis, Eleni Kalopesa, and Nikolaos Tziolas. 2025. "An Agricultural Hybrid Carbon Model for National-Scale SOC Stock Spatial Estimation" Environments 12, no. 12: 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12120477

APA StyleSamarinas, N., Tsakiridis, N. L., Kalopesa, E., & Tziolas, N. (2025). An Agricultural Hybrid Carbon Model for National-Scale SOC Stock Spatial Estimation. Environments, 12(12), 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments12120477