Changing University Students’ Habit Strength Towards Alcohol Consumption Using Affectively and Cognitively Framed Messages

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Alcohol Consumption in the University Population

1.2. Elaboration Likelihood Model

1.3. Need for Cognition

1.4. Habit

1.5. Habit–Emotion Relationship

1.6. Temporal Salience of Outcomes

1.7. Health Messages

1.8. Gender

1.9. Hypothesis

2. Method

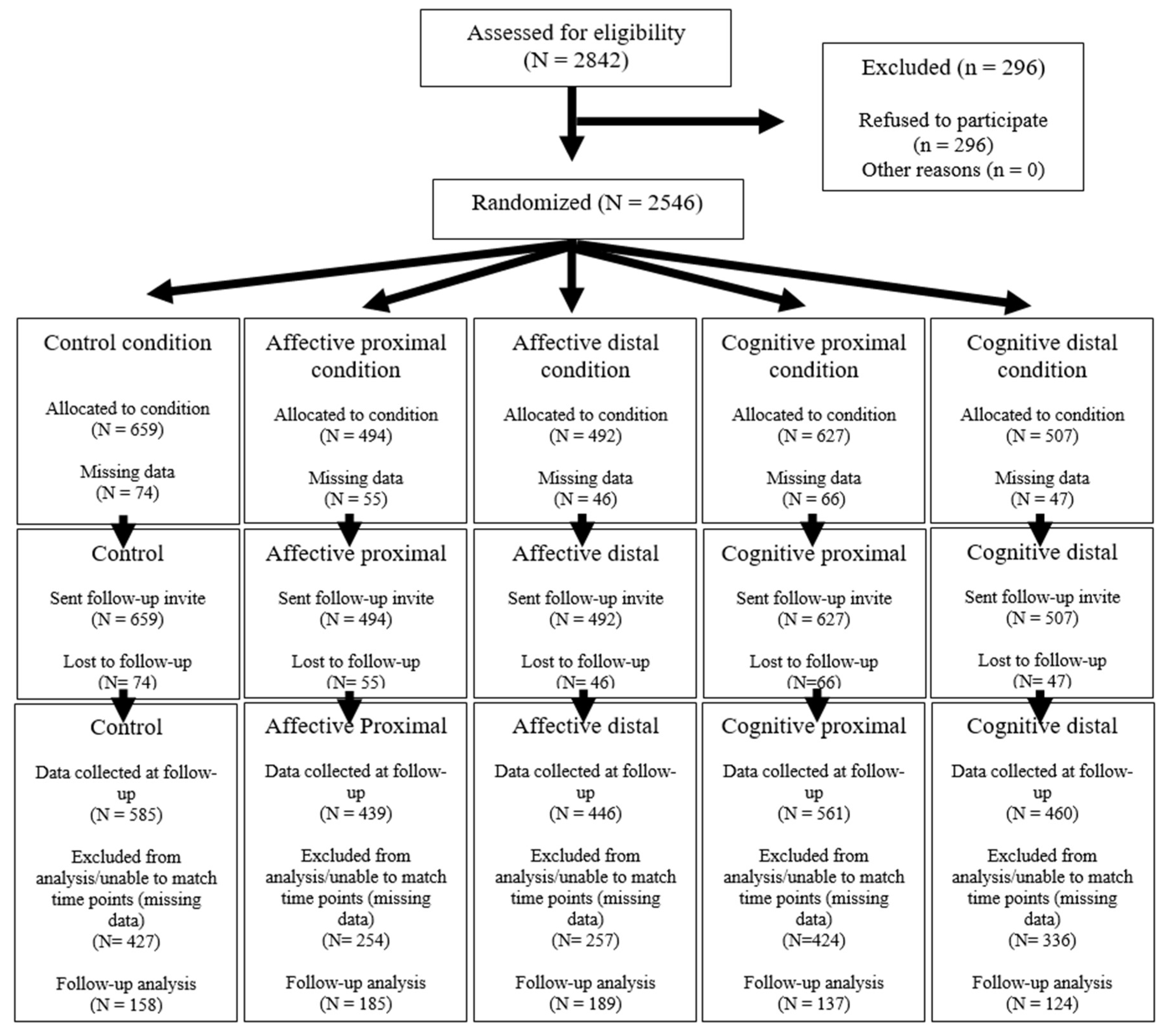

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Intervention

2.5. Procedure

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abhyankar, P., O’Connor, D. B., & Lawton, R. (2008). The role of message framing in promoting MMR vaccination: Evidence of a loss-frame advantage. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Acuff, S. F., Strickland, J. C., Smith, K., & Field, M. (2024). Heterogeneity in choice models of addiction: The role of context. Psychopharmacology, 241, 1757–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainslie, G., & Haendel, V. (1983). The motives of the will. In E. Gottheil, K. Druley, T. Skodola, & H. Waxman (Eds.), Etiology aspects of alcohol & drug abuse. Charles C. Thomas. [Google Scholar]

- Alsharawy, A., Spoon, R., Smith, A., & Ball, S. (2021). Gender differences in fear and risk perception during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 689467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, N. P., Ott, M. Q., Rogers, M. L., Loxley, M., Linkletter, C., & Clark, M. A. (2014). Peer associations for substance use and exercise in a college student social network. Health Psychology, 33(10), 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, R., Kerry-Barnard, S., Beckley-Hoelscher, N., Phillips, R., Reid, F., Fleming, C., Lesniewska, A., Yoward, F., & Oakeshott, P. (2021). Alcohol use, cigarette smoking, vaping and number of sexual partners: A cross-sectional study of sexually active, ethnically diverse, inner-city adolescents. Health Expectations, 24, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholow, B. D., & Heinz, A. (2006). Alcohol and aggression without consumption: Alcohol cues, aggressive thoughts, and hostile perception bias. Psychological Science, 17(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S., & Murphy, K. M. (1988). A theory of rational addiction. Journal of Political Economy, 96, 675–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennasar-Veny, M., Yañez, A. M., Pericas, J., Ballester, L., Fernandez-Dominguez, J. C., Tauler, P., & Aguilo, A. (2020). Cluster analysis of health-related lifestyles in university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benthin, A., Slovic, P., Moran, P., Severson, H., Mertz, C. K., & Gerrard, M. (1995). Adolescent health-threatening and health-enhancing behaviors: A study of word association and imagery. Journal of Adolescent Health, 17, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewick, B. M., Mulhern, B., Barkham, M., Trusler, K., Hill, A. J., & Stiles, W. B. (2008). Changes in undergraduate student alcohol consumption as they progress through university. BMC Public Health, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, S. J., Devellis, B. M., Afifi, R. A., & Sandler, R. S. (1990). Risk perceptions and participation in colorectal cancer screening. Health Psychology, 9, 792–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolsen, T., & Palm, R. (2019). Motivated reasoning and political decision making. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, C., Skinner, T., & Chan, C. K. Y. (2025). Narrative episodic future thinking reduces delay discounting and enhances goal salience in the general population: An online feasibility study. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 13(1), 2531948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brebner, J. (2003). Gender and emotions. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R., & Murphy, S. (2020). Alcohol and social connectedness for new residential university students: Implications for alcohol harm reduction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(2), 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R., & Sheron, N. (2018). No level of alcohol consumption improves health. The Lancet, 392(10152), 987–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Kao, C. F. (1984). The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality, 48, 306–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., Petty, R. E., & Morris, K. J. (1983). Effects of need for cognition on message evaluation, recall, and persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D., Epton, T., Norman, P., Sheeran, P., Harris, P. R., Webb, T. L., Julious, S. A., Brennan, A., Thomas, C., Petroczi, A., & Naughton, D. (2015). A theory-based online health behaviour intervention for new university students (U@Uni: LifeGuide): Results from a repeat randomized controlled trial. Trials, 16, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, C., & Wood, M. D. (2009). Thinking about drinking: Need for cognition and readiness to change moderate the effects of brief alcohol interventions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 23(4), 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, A. C., Brandon, K. O., & Goldman, M. S. (2010). The college and noncollege experience: A review of the factors that influence drinking behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 71(5), 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, E. M., & Shafir, E. (2006). Now that I think about it, I’m in the mood for laughs: Decisions focused on mood. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T. M., Hong, K., Bergquist, K., & Sinha, R. (2008). Gender differences in response to emotional stress: An assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(7), 1242–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H. G., Chen, S., McBride, O., & Phillips, M. R. (2016). Prospective relationship of depressive symptoms, drinking, and tobacco smoking among middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling adults: Results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 195, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conner, M., Rhodes, R. E., Morris, B., McEachan, R., & Lawton, R. (2011). Changing exercise through targeting affective or cognitive attitudes. Psychology & Health, 26, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M., Wilding, S., van Harreveld, F., & Dalege, J. (2020). Cognitive-affective inconsistency and ambivalence: Impact on the overall attitude–behavior relationship. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(4), 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, D., & Nicholls, E. (2022). ‘When I open it, I have to drink it all’: Push and pull factors shaping domestic alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic UK spring 2020 lockdown. Drug and Alcohol Review, 41(6), 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvera-Tindel, T., Doering, L. V., Gomez, T., & Dracup, K. (2004). Predictors of noncompliance to exercise training in heart failure. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(4), 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, J., Li, A. H., Garg, A. X., Chassé, M., Grimshaw, J. M., & Presseau, J. (2022). Identifying behaviour change techniques within randomized trials of interventions promoting deceased organ donation registration. British Journal of Health Psychology, 27, 822–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantzer, C., Wardle, J., Fuller, R., Pampalone, S. Z., & Steptoe, A. (2006). International study of heavy drinking: Attitudes and sociodemographic factors in university students. Journal of American College Health, 55, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoren, M. P., Demant, J., Shiely, F., & Perry, I. J. (2016). Alcohol consumption among university students in Ireland and the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2014: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 16, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vere Hunt, I., & Linos, E. (2022). Social media for public health: Framework for social media–based public health campaigns. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(12), e42179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dijkstra, A., Sweeney, L., & Gebhardt, W. (2001). Social cognitive determinants of drinking in young adults: Beyond the alcohol expectancies paradigm. Addictive Behaviors, 26(5), 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Plinio, S., Aquino, A., Haddock, G., Alparone, F. R., & Ebisch, S. J. H. (2025). Brain and behavior in persuasion: The role of affective-cognitive matching. Psychophysiology, 62, e70088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditto, P. H., Pizarro, D. A., Epstein, E. B., Jacobson, J. A., & MacDonald, T. K. (2006). Visceral influences on risk-taking behavior. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkaware. (2025, June 30). UK low risk drinking guidelines: The chief medical officers’ advice. Drinkaware. Available online: https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/information-about-alcohol/alcohol-and-the-facts/low-risk-drinking-guidelines (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Eberhard, K. (2023). The effects of visualization on judgment and decision-making: A systematic literature review. Management Review Quarterly, 73(1), 167–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W. (1954). The theory of decision making. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 380–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epper, T. F., & Fehr-Duda, H. (2024). Risk in time: The intertwined nature of risk taking and time discounting. Journal of the European Economic Association, 22(1), 310–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. B., Shanahan, E., Leith, S., Litvak, N., & Wilson, A. E. (2019). Living for today or tomorrow? Self-regulation amidst proximal or distal exercise outcomes. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11, 304–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T. (2021). Expectancy-value approaches: Present status and future directions. In Expectations and actions (pp. 395–420). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Feingold, A. (1994). Gender differences in personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, L., & Hart, P. S. (2018). Broadening exposure to climate change news? How framing and political orientation interact to influence selective exposure. Journal of Communication, 68(3), 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, L., Fairbrother, H., Whitaker, V., Henney, M., Stevely, A., & Holmes, J. (2023). “When I came to university, that’s when the real shift came”: Alcohol and belonging in English higher education. Journal of Youth Studies, 27(7), 1006–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finucane, M. L., Alhakami, A., Slovic, P., & Johnson, S. M. (2000). The affect heuristic in judgements of risks and benefits. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 13(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A. H., Mosquera, P. M. R., van Vianen, A. E. M., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2004). Gender and culture differences in emotion. Emotion, 4, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhoff, B., Slovic, P., Lichtenstein, S., Read, S., & Combs, B. (1978). How safe is safe enough? A psychometric study of attitudes towards technological risks and benefits. Policy Sciences, 9(2), 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M. R., & Bamberger, P. A. (2024). Alcohol and illicit drug involvement in the workforce and workplace. In L. E. Tetrick, G. G. Fisher, M. T. Ford, & J. C. Quick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (3rd ed., pp. 361–383). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambles, N., Porcellato, L., Fleming, K. M., & Quigg, Z. (2021). “If you don’t drink at university, you’re going to struggle to make friends”: Prospective students’ perceptions around alcohol use at universities in the United Kingdom. Substance Use & Misuse, 57(2), 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glassman, T., Paprzycki, P., Castor, T., Wotring, A., Wagner-Greene, V., Ritzman, M., & Kruger, J. (2018). Using the elaboration likelihood model to address drunkorexia among college students. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(9), 1411–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimcher, P. W. (2022). Efficiently irrational: Deciphering the riddle of human choice. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(8), 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C. M. J., Asharani, P. V., Abdin, E., Shahwan, S., Zhang, Y., Sambasivam, R., Vaingankar, J. A., Ma, S., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2024). Gender differences in alcohol use: A nationwide study in a multiethnic population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22(3), 1161–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W., Yang, X., Liu, X., & Xu, W. (2023). Mindfulness and negative emotions among females who inject drugs: The mediating role of social support and resilience. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(6), 3627–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, G., Maio, G. R., Arnold, K., & Huskinson, T. (2008). Should persuasion be affective or cognitive? The moderating effects of need for affect and need for cognition. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P. A., & Fong, G. T. (2003). The effects of a brief time perspective intervention for increasing physical activity among young adults. Psychology & Health, 18(6), 685–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P. A., & Fong, G. T. (2007). Temporal self-regulation theory: A model for individual health behavior. Health Psychology Review, 1(1), 6–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Montes, M., Alonso-Blanco, C., Paz-Zulueta, M., Pellico-López, A., Ruiz-Azcona, L., Sarabia-Cobo, C., Boixadera-Planas, E., & Parás-Bravo, P. (2022). Excessive alcohol consumption and binge drinking in college students. PeerJ, 10, e13368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, S. T., Zarei, L., Sadati, A. K., Moradi, N., Akbari, M., Mehralian, G., & Lankarani, K. B. (2021). The effect of risk communication on preventive and protective behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Mediating role of risk perception. BMC Public Health, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hittner, J. B. (2004). Alcohol use among American college students in relation to need for cognition and expectations of alcohol’s effects on cognition. Current Psychology, 23, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W., Friese, M., & Wiers, R. W. (2008). Impulsive versus reflective influences on health behavior: A theoretical framework and empirical review. Health Psychology Review, 2(2), 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsee, C. K., & Rottenstreich, Y. (2004). Music, pandas, and muggers: On the affective psychology of value. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133(1), 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingendahl, M., Hummel, D., Maedche, A., & Vogel, T. (2021). Who can be nudged? Examining nudging effectiveness in the context of need for cognition and need for uniqueness. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(2), 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. W., Sinclair, R. C., & Courneya, K. S. (2006). The effects of source credibility and message framing on exercise intentions, behaviors, and attitudes: An integration of the elaboration likelihood model and prospect theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalocsanyiova, E., Essex, R., & Fortune, V. (2023). Inequalities in COVID-19 messaging: A systematic scoping review. Health Communication, 38(12), 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keough, K. A., Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Who’s smoking, drinking, and doing drugs? Time perspective as a predictor of substance use. Journal of Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 21, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezer, C. A., Simonetto, D. A., & Shah, V. H. (2021). Sex differences in alcohol consumption and alcohol-associated liver disease. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 96(4), 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kypri, K., Cronin, M., & Wright, C. S. (2005). Do university students drink more hazardously than their non-student peers? Addiction, 100, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lannoy, S., Duka, T., Carbia, C., Billieux, J., Fontesse, S., Dormal, V., Gierski, F., López-Caneda, E., Sullivan, E. V., & Maurage, P. (2021). Emotional processes in binge drinking: A systematic review and perspective. Clinical psychology review, 84, 101971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Berre, A.-P. (2019). Emotional processing and social cognition in alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychology, 33(6), 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. S., Dorison, C. A., & Klusowski, J. (2024). How do emotions affect decision making? In Emotion theory: The Routledge comprehensive guide (pp. 447–468). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, G. F., & Elster, J. (1992). Choice over time. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Loewenstein, G. F., & Thaler, R. (1989). Anomalies: Intertemporal choice. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, C. S., & Greitemeyer, T. (2023). Are women the more empathetic gender? The effects of gender role expectations. Current Psychology, 42, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, D. G., Slovic, P., Dreman, D., & Berry, M. (2000). Imagery, affect, and financial judgment. Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 1, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackert, M., Mandell, D., Donovan, E., Walker, L., Henson-García, M., & Bouchacourt, L. (2021). Mobile apps as audience-centered health communication platforms. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 9(8), e25425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, J. E., Brawley, L., & Boykin, A. (1995). Self-efficacy and healthy behavior: Prevention, promotion, and detection. In J. E. Maddux (Ed.), Self-efficacy, adaptation, and adjustment: Theory, research, and application (pp. 173–202). Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, X. T., Trinh, T. T., & Ryan, C. (2024). Are you hungry for play? Investigating the role of emotional attachment on continuance intention to use food delivery apps. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7(5), 2968–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M. M., Wright, A. J., Corker, E., Johnston, M., West, R., Hastings, J., & Michie, S. (2024). The behaviour change technique ontology: Transforming the Behaviour change technique taxonomy v1. Wellcome Open Research, 8, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, T., & Mullan, B. A. (2022). The role of environmental cues in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption using a temporal self-regulation theory framework. Appetite, 169, 105828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConaha, C. D., McCabe, B. E., & Falcon, A. L. (2024). Anxiety, depression, coping, alcohol use and consequences in young adult college students. Substance Use & Misuse, 59(2), 306–311. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, M. P., Battagliese, G., D’angelo, A., Ciccarelli, R., Pisciotta, F., Tramonte, L., Fiore, M., Ferraguti, G., Vitali, M., & Ceccanti, M. (2021). Knowledge and practice towards alcohol consumption in a sample of university students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Eccles, M. P., Cane, J., & Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollen, S., Engelen, S., Kessels, L. T. E., & van den Putte, B. (2017). Short and sweet: The persuasive effects of message framing and temporal context in antismoking warning labels. Journal of Health Communication, 22(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, B., Lawton, R., McEachan, R., Hurling, R., & Conner, M. (2015). Changing self-reported physical activity using different types of affectively and cognitively framed health messages in a student population. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 21(2), 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, X., Iles, I. A., Yang, B., & Ma, Z. (2022). Public health messaging during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: Lessons from communication science. Health Communication, 37(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. (2022, October 24). The risks of drinking too much. NHS. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/alcohol-advice/the-risks-of-drinking-too-much/ (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2004). Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical psychology review, 24(8), 981–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollendick, T. H., Yang, B., Dong, Q., Xia, Y., & Lin, L. (1995). Perceptions of fear in other children and adolescents: The role of gender and friendship status. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 23(4), 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orbell, S., Perugini, M., & Rakow, T. (2004). Individual differences in sensitivity to health communications: Consideration of future consequences. Health Psychology, 23(4), 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, F. A., Ganie, A. U. R., & Dar, D. R. (2024). Substance use in university students: A comprehensive examination of its effects on academic achievement and psychological well-being. Social Work in Mental Health, 22(3), 452–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E. (2006). The functions of affect in the construction of preferences. The construction of preference, 454–463. [Google Scholar]

- Petry, N. M. (2001). Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology, 154(3), 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R. E., Barden, J., & Wheeler, S. C. (2009). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion: Developing health promotions for sustained behavioral change. In R. J. DiClemente, R. A. Crosby, & M. C. Kegler (Eds.), Emerging theories in health promotion practice and research (2nd ed., pp. 185–214). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion (pp. 1–24). Springer Series in Social Psychology. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J., Soerjomataram, I., Ferreira-Borges, C., & Shield, K. D. (2019). Does alcohol use affect cancer risk? Current nutrition reports, 8(3), 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, B. C., & Carey, K. B. (2019). Wonderland and the rabbit hole: A commentary on university students’ alcohol use during first year and the early transition to university. Drug and Alcohol Review, 38(1), 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklage, M. D., & Luttrell, A. (2021). Attitudes based on feelings: Fixed or fleeting? Psychological Science, 32(3), 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenstreich, Y., & Hsee, C. K. (2001). Money, kisses, and electric shocks: On the affective psychology of risk. Psychological Science, 12(3), 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J. F., Prochaska, J. J., Taylor, W. C., Hill, J. O., & Geraci, J. C. (1999). Correlates of physical activity in a national sample of girls and boys in grades 4 through 12. Health Psychology, 18(4), 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M. G., Sanchez, Z. M., Hughes, K., Gee, I., & Quigg, Z. (2022). Pre-drinking, alcohol consumption and related harms amongst Brazilian and British university students. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0264842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, K. S., Maleki, N., Urban, T., Marinkovic, K., Karson, S., Ruiz, S. M., Harris, G. J., & Oscar-Berman, M. (2019). Alcoholism gender differences in brain responsivity to emotional stimuli. eLife, 8, e41723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N. (2010). Meaning in context: Metacognitive experiences. In The mind in context (pp. 105–125). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, K. L., Abiodun, S. J., Fenn, Z., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., & Mata, R. (2022). Temporal discounting across adult hood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 37(1), 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevincer, A. T., Oettingen, G., & Lerner, T. (2012). Alcohol affects goal commitment by explicitly and implicitly induced myopia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(2), 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shell, D. F. (2023). Outcome expectancy in social cognitive theory: The role of contingency in agency and motivation in education. Theory Into Practice, 62(3), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shell, D. F., & Flowerday, T. (2019). Affordances and attention: Learning and culture. In K. A. Renninger, & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook on motivation and learning (pp. 759–782). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiota, M. N. (2021). Awe, wonder, and the human mind. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1501(1), 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, L., Raninen, J., & Larm, P. (2024). Early drinking onset and subsequent alcohol use in late adolescence: A longitudinal study of drinking patterns. Journal of Adolescent Health, 74(6), 1225–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P., Finucane, M. L., Peters, E., & MacGregor, D. G. (2002). The affect heuristic. In T. Gilovich, D. Griffin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.), Heuristics and biases: The psychology of intuitive judgment (pp. 397–420). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova, E. V., Bartholow, B. D., Saults, J. S., & Friedman, R. S. (2018). Effects of exposure to alcohol-related cues on racial discrimination. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(3), 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A., Koyanagi, A., Koposov, R., Razvodovsky, Y., & Ruchkin, V. (2013). Adolescent binge drinking and risky health behaviours: Findings from northern Russia. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 133(3), 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strack, F., & Deutsch, R. (2004). Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8, 220–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strathman, A., Gleicher, F., Boninger, D. S., & Edwards, C. S. (1994). The consideration of future consequences: Weighing immediate and distant outcomes of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(4), 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, M. B., Hepler, J., Zimmerman, R. S., Saul, L., Jacobs, S., Wilson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2015). Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological Bulletin, 141(6), 1178–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, C., Burns, S., & Kalembo, F. (2017). The association between levels of alcohol consumption and mental health problems and academic performance among young university students. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0178142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedens, L. Z., & Linton, S. (2001). Judgment under emotional certainty and uncertainty: The effects of specific emotions on information processing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffany, S. T., & Drobes, D. J. (1990). Imagery and smoking urges: The manipulation of affective content. Addictive Behaviors, 15(6), 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrisi, R., Mallett, K. A., Mastroleo, N. R., & Larimer, M. E. (2006). Heavy drinking in college students: Who is at risk and what is being done about it? The Journal of General Psychology, 133(4), 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, H., Manstead, A. S. R., van der Pligt, J., & Wigboldus, D. H. J. (2005). The role of affect in attitudes toward organ donation and donor-relevant decisions. Psychology & Health, 20(6), 789–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, E., & Zeelenberg, M. (2006). The dampening effect of uncertainty on positive and negative emotions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Valkengoed, A. M., Abrahamse, W., & Steg, L. (2022). To select effective interventions for pro-environmental behaviour change, we need to consider determinants of behaviour. Nature human behaviour, 6(11), 1482–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: A self-report index of habit strength 1. Journal of applied social psychology, 33(6), 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Huang, C., Xu, L., & Zhang, J. (2023). Drinking into friends: Alcohol drinking culture and CEO social connections. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 212, 982–995. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A., & Clark, D. (1998). Alcohol consumption in university students: The role of reasons for drinking, coping strategies, expectancies, and personality traits. Addictive Behaviors, 23(3), 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. R., Hultsch, D. F., Strauss, E. H., Hunter, M. A., & Tannock, R. (2005). Inconsistency in reaction time across the life span. Neuropsychology, 19(1), 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2018). Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zack, M. (2006). What can affective neuroscience teach us about gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M., & Beattie, J. (1997). Consequences of regret aversion 2: Additional evidence for effects of feedback on decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 72(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, P., & Boyd, J. (2008). The time paradox: The new psychology of time that will change your life. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Zimbardo, P. G., Keough, K. A., & Boyd, J. N. (1997). Present time perspective as a predictor of risky driving. Personality and Individual Differences, 23(6), 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Mean Age | Gender Ratio, Men to Women | Alcohol Consumption at Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 22.40 (5.33) | 52 vs. 104 | 12.73 (18.05) |

| Affective proximal | 23.08 (5.73) | 61 vs. 124 | 12.49 (16.71) |

| Affective distal | 22.62 (5.47) | 41 vs. 90 | 13.67 (19.56) |

| Cognitive proximal | 22.94 (5.66) | 44 vs. 94 | 10.70 (14.34) |

| Cognitive distal | 23.67 (8.05) | 52 vs. 72 | 14.25 (22.09) |

| Condition | Undergraduate Level | Postgraduate | Other | Not Reported | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | M | PhD | |||

| Control | 50 | 38 | 27 | 15 | 9 | 1 | 15 |

| Affective proximal | 53 | 40 | 38 | 23 | 15 | 1 | 15 |

| Affective distal | 34 | 30 | 28 | 17 | 9 | 0 | 13 |

| Cognitive proximal | 34 | 32 | 31 | 19 | 10 | 0 | 11 |

| Cognitive distal | 37 | 25 | 25 | 17 | 12 | 0 | 8 |

| Message | Estimated Marginal Mean | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 2.76 d | 0.09 | 2.58 | 2.94 |

| Cognitive proximal | 2.84 cd | 0.09 | 2.66 | 3.02 |

| Cognitive distal | 2.81 bcd | 0.09 | 2.62 | 3.00 |

| Affective proximal | 2.72 abcd | 0.09 | 2.55 | 2.89 |

| Affective distal | 2.47 a | 0.11 | 2.27 | 2.68 |

| NfC | Gender | Message | Estimated Marginal Mean | Standard Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Men | Control | 2.73 b | 0.31 | 2.13 | 3.34 |

| Cognitive proximal | 2.87 b | 0.29 | 2.28 | 3.46 | ||

| b < a | Cognitive distal | 3.02 b | 0.32 | 2.39 | 3.65 | |

| Affective proximal | 2.61 b | 0.30 | 2.01 | 3.20 | ||

| Affective distal | 1.30 a | 0.42 | 0.48 | 2.12 | ||

| Women | Control | 2.96 ab | 0.18 | 2.60 | 3.32 | |

| Cognitive proximal | 3.18 a | 0.19 | 2.82 | 3.55 | ||

| Cognitive distal | 2.90 ab | 0.19 | 2.45 | 3.07 | ||

| Affective proximal | 2.63 b | 0.17 | 2.30 | 2.97 | ||

| Affective distal | 3.04 ab | 0.18 | 2.69 | 3.39 | ||

| High | Men | Control | 2.83 ab | 0.15 | 2.52 | 3.13 |

| Cognitive proximal | 2.49 a | 0.18 | 2.14 | 2.85 | ||

| Cognitive distal | 2.76 ab | 0.16 | 2.45 | 3.07 | ||

| Affective proximal | 2.97 b | 0.15 | 2.68 | 3.26 | ||

| Affective distal | 2.95 ab | 0.17 | 2.63 | 3.28 | ||

| Women | Control | 2.65 a | 0.10 | 2.44 | 2.85 | |

| Cognitive proximal | 2.73 a | 0.11 | 2.51 | 2.94 | ||

| Cognitive distal | 2.58 a | 0.14 | 2.30 | 2.85 | ||

| Affective proximal | 2.70 a | 0.09 | 2.51 | 2.89 | ||

| Affective distal | 2.70 a | 0.11 | 2.47 | 2.92 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morris, B.; St Quinton, T.; Conner, M. Changing University Students’ Habit Strength Towards Alcohol Consumption Using Affectively and Cognitively Framed Messages. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121637

Morris B, St Quinton T, Conner M. Changing University Students’ Habit Strength Towards Alcohol Consumption Using Affectively and Cognitively Framed Messages. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121637

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorris, Benjamin, Tom St Quinton, and Mark Conner. 2025. "Changing University Students’ Habit Strength Towards Alcohol Consumption Using Affectively and Cognitively Framed Messages" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 12: 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121637

APA StyleMorris, B., St Quinton, T., & Conner, M. (2025). Changing University Students’ Habit Strength Towards Alcohol Consumption Using Affectively and Cognitively Framed Messages. Behavioral Sciences, 15(12), 1637. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15121637