Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for Health Assessment in Wild Adult Harbour Seals

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

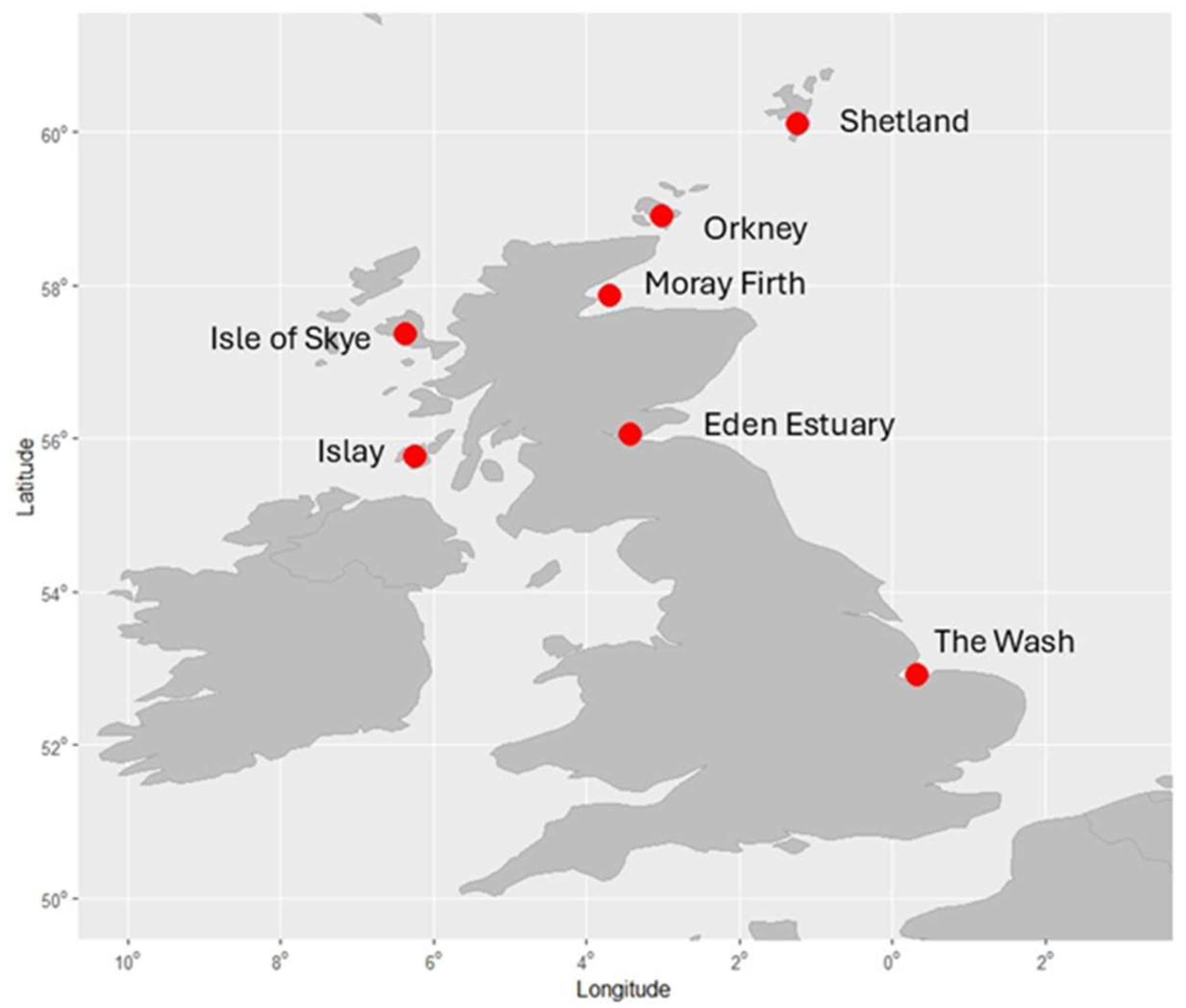

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Sample Analysis

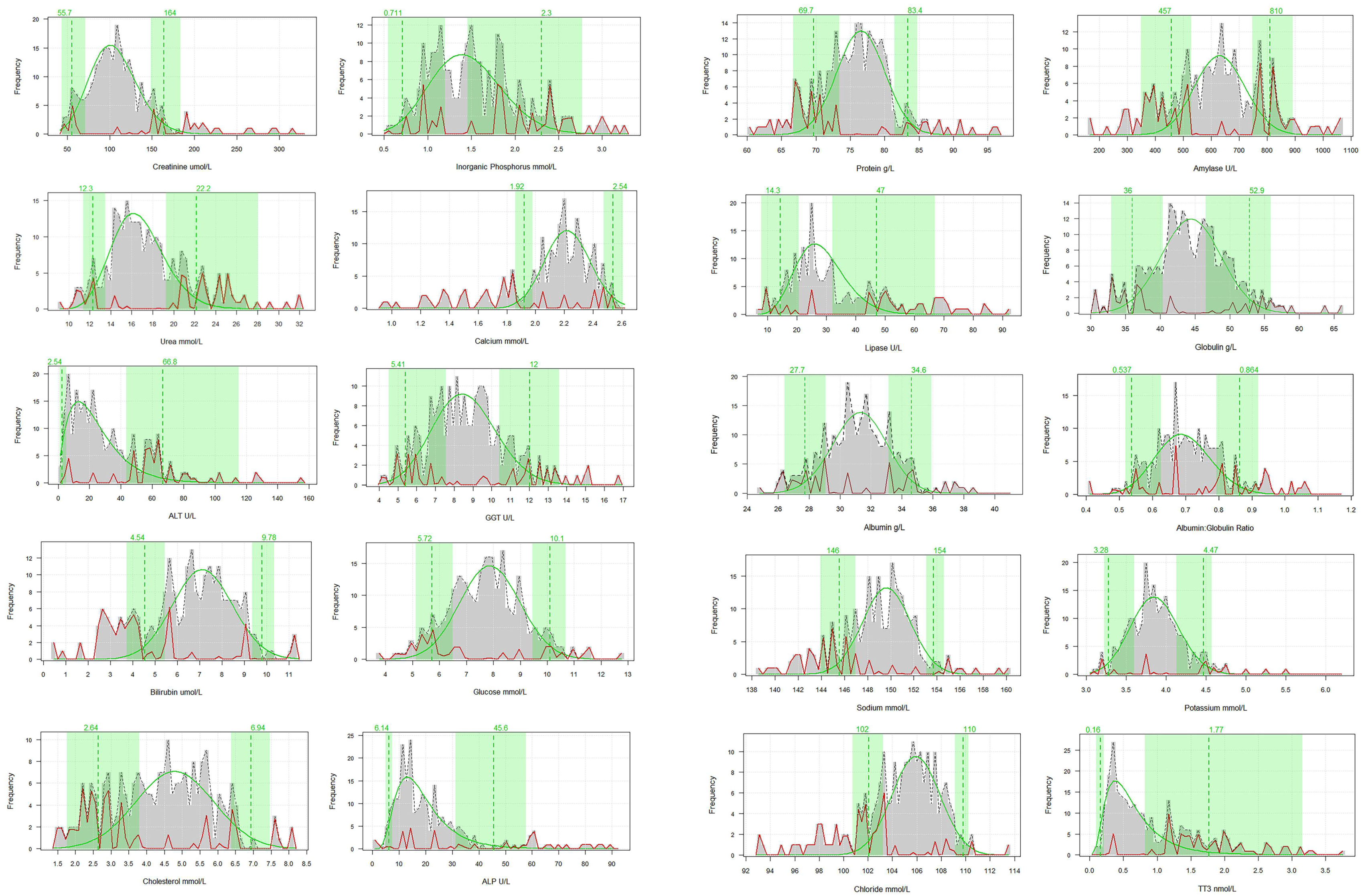

2.3. Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals Generation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IFCC | International Federation of Clinical Chemistry |

| RWD | Real-World Data |

| TT3 | Total Triiodothyronine |

| i.v. | Intravenous |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl Transferase |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ALT | Alanine Transaminase |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| VESOP | Veterinary Expert System for Outcome Prediction |

References

- Kerr, M.G. Veterinary Laboratory Medicine: Clinical Biochemistry and Haematology; John Wiley & Sons: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Thomas, L.; Wells, R.S.; Rowles, T.K.; Bossart, G.D.; Townsend, F., Jr.; Mazzoil, M.; Allen, J.B.; Balmer, B.C.; Barleycorn, A.A.; et al. An expert-based system to predict population survival rate from health data. Conserv. Biol. 2024, 38, e14073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, H. Approved recommendation on the theory of reference values. Part 5. Statistical treatment of collected reference values. Determination of reference limits. Clin. Chim. Acta 1984, 170, S13–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siest, G.; Henny, J.; Gräsbeck, R.; Wilding, P.; Petitclerc, C.; Queraltó, J.M.; Hyltoft Petersen, P. The theory of reference values: An unfinished symphony. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013, 51, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierauf, L.A.; Gulland, F.M.D. CRC Handbook of Marine Mammal Medicine, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, A.C.; Robinson, S.J.; Borjesson, D.L.; Barbieri, M.; Littnan, C.L. Establishing hematology and serum chemistry reference intervals for wild Hawaiian monk seals (Neomonachus schauinslandi). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2018, 49, 1036–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, G.; Altaie, S.; Boyd, J.; Ceriotti, F.; Garg, U.; Horn, P. Defining, Establishing, and Verifying Reference Intervals in the Clinical Laboratory. In Approved Guideline, 3rd ed.; EP28-A3C; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gräsbeck, R. The evolution of the reference value concept. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004, 42, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; Nilsson, J.-E.; Solberg, H.E.; Tryding, N. Practical experience in the selection and preparation of reference individuals: Empirical testing of the provisional Scandinavian recommendations. In Reference Values in Laboratory Medicine; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 1981; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ceriotti, F.; Hinzmann, R.; Panteghini, M. Reference intervals: The way forward. Annal. Clin. Biochem. 2009, 46, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriotti, F. Prerequisites for use of common reference intervals. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2007, 28, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichs, K.R.; Harr, K.E.; Freeman, K.P.; Szladovits, B.; Walton, R.M.; Barnhart, K.F.; Blanco-Chavez, J. ASVCP reference interval guidelines: Determination of de novo reference intervals in veterinary species and other related topics. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 41, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré-Masferrer, M.; Fuentes-Arderiu, X.; Puchal-Añe, R. Indirect reference limits estimated from patients’ results by three mathematical procedures. Clin. Chim. Acta 1999, 279, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadenhuijsen, H.; Smit, J.C. Indirect estimation of clinical chemical reference intervals from total hospital patient data: Application of a modified Bhattacharya procedure. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1985, 23, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.R.D.; Haeckel, R.; Loh, T.P.; Sikaris, K.; Streichert, T.; Katayev, A.; Barth, J.H.; Ozarda, Y.; IFCC Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits. Indirect methods for reference interval determination—Review and recommendations. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 57, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, P.S.; Pesce, A.J.; Copeland, B.E. A robust approach to reference interval estimation and evaluation. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, L.G.; Brandslund, I.; Petersen, P.H. Should we maintain the 95 percent reference intervals in the era of wellness testing? A concept paper. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004, 42, 747–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solberg, H.E. International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC), Scientific Committee, Clinical Section, Expert Panel on Theory of Reference Values, and International Committee for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH), Standing Committee on Reference Values. Approved Recommendation (1986) on the theory of reference values. Part 1. The concept of reference values. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1987, 25, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, J.; Karniski, C. Diving beneath the surface: Long-term studies of dolphins and whales. J. Mammal. 2017, 98, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yochem, P.K.; Stewart, B.S.; Mazet, J.A.K.; Boyce, W.M. Hematologic and serum biochemical profile of the northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris): Variation with age, sex, and season. J. Wildl. Dis. 2008, 44, 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Hall, A.J.; Townsend, F.I.; Wells, R.S.; Hansen, L.J.; Hohn, A.A.; Bossart, G.D.; Fair, P.A.; Rowles, T.K. Hematologic and serum biochemical reference intervals for free-ranging common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and variation in the distributions of clinicopathologic values related to geographic sampling site. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2009, 70, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Twiner, M.J.; De Guise, S.; Balmer, B.C.; Wells, R.S.; Townsend, F.I.; Rotstein, D.C.; Varela, R.A.; Hansen, L.J.; Zolman, E.S.; et al. Eosinophilia and biotoxin exposure in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from a coastal area impacted by repeated mortality events. Environ. Res. 2010, 110, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Zolman, E.S.; Balmer, B.C.; De Guise, S.; George, R.C.; Hoguet, J.; Hohn, A.A.; Kucklick, J.R.; Lamb, S.; Levin, M.; et al. Anaemia, hypothyroidism and immune suppression associated with polychlorinated biphenyl exposure in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Proc. R. Soc. B 2012, 279, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Smith, C.R.; Townsend, F.I.; Wells, R.S.; Hart, L.B.; Balmer, B.C.; Collier, T.K.; De Guise, S.; Fry, M.M.; Guillette, L.J.; et al. Health of Common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Barataria Bay, Louisiana, Following the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirotta, E.; Booth, C.G.; Costa, D.P.; Fleishman, E.; Kraus, S.D.; Lusseau, D.; Moretti, D.; New, L.F.; Schick, R.S.; Schwarz, L.K.; et al. Understanding the population consequences of disturbance. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 9934–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirotta, E.; Thomas, L.; Costa, D.P.; Hall, A.J.; Harris, C.M.; Harwood, J.; Kraus, S.D.; Miller, P.J.O.; Moore, M.J.; Photopoulou, T.; et al. Understanding the combined effects of multiple stressors: A new perspective on a longstanding challenge. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 821, 153322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.L.; Thomas, L.; Costa, D.P.; Hall, A.J.; Harris, C.M.; Harwood, J.; Kraus, S.D.; Miller, P.J.O.; Moore, M.; Photopoulou, T.; et al. Managing the effects of multiple stressors on wildlife populations in their ecosystems: Developing a cumulative risk approach. Proc. R. Soc. B 2022, 289, 20222058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.M.; Tollit, D.J.; Corpe, H.M.; Reid, R.J.; Ross, H.M. Changes in haematological parameters in relation to prey switching in a wild population of harbour seals. Funct. Ecol. 1997, 11, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Frame, E. Evidence of domoic acid exposure in harbour seals from Scotland: A potential factor in the decline in abundance? Harmful Algae 2010, 9, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, L.S.; Duck, C.D.; Mackey, B.L.; Hall, A.J.; Thompson, P.M. Long-term patterns in harbour seal site-use and the consequences for managing protected areas. Anim. Conserv. 2011, 14, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, G.D.; Russell, D.J.F.; McConnell, B.; Moss, S.; Thompson, D.; Janik, V.M. Sound exposure in harbour seals during the installation of an offshore wind farm: Predictions of auditory damage. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.J.F.; Hastie, G.D.; Thompson, D.; Janik, V.M.; Hammond, P.S.; Scott-Hayward, L.A.S.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Jones, E.L.; McConnell, B.J. Avoidance of wind farms by harbour seals is limited to pile driving activities. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 53, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, J.L.; Stubberfield, E.J.; Foster, G.; Brownlow, A.; Hall, A.J.; Perrett, L.L. Exposure of harbour seals Phoca vitulina to Brucella in declining populations across Scotland. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2017, 126, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Mackey, B.; Kershaw, J.L.; Thompson, P. Age-length relationships in UK harbour seals during a period of population decline. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.I.D.; Boehme, L.; Cronin, M.A.; Duck, C.D.; Grecian, W.J.; Hastie, G.D.; Jessopp, M.; Matthiopoulos, J.; McConnell, B.J.; Miller, D.L.; et al. Sympatric seals, satellite tracking and protected areas: Habitat-based distribution estimates for conservation and management. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 875869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.; Duck, C.D.; Morris, C.D.; Russell, D.J.F. The status of harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) in the UK. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 29, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, D.J.; Gulland, F.M.D.; Rios, C.A.; Hall, A.J. Hematology and serum chemistry in stranded and wild-caught harbor seals in Central California: Reference intervals, predictors of survival and parameters affecting blood variables. J. Wildl. Dis. 2010, 46, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammer, T.; Schützenmeister, A.; Prokosch, H.-U.; Rauh, M.; Rank, C.M.; Zierk, J. refineR: A novel algorithm for reference interval estimation from Real-World Data. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, D.; Ahola, M.P.; Carlsson, A.M.; Galatius, A.; Nilssen, K.T.; Härkönen, T.; Harding, K.C. Declining harbour seal abundance in a previously recovering meta-population. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J.; Thomas, G.O. Polychlorinated biphenyls, DDT, polybrominated diphenyl ethers and organic pesticides in United Kingdom harbor seals—Mixed exposures and thyroid homeostasis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.; Hewitt, R.; Civil, M.A. Determining pregnancy status in harbour seals using progesterone concentrations in blood and blubber. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 295, 113529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ammer, T.; Rank, C.M.; Schuetzenmeister, A. refineR: Reference Interval Estimation using Real-World Data, R Package Version 1.6.1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/refineR/index.html (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ammer, T.; Schützenmeister, A.; Rank, C.M.; Doyle, K. Estimation of reference intervals from routine data using the refineR algorithm—A practical guide. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2023, 8, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierk, J.; Arzideh, F.; Kapsner, L.A.; Prokosch, H.-U.; Metzler, M.; Rauh, M. Reference interval estimation from mixed distributions using truncation points and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov distance (kosmic). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roletto, J. Hematology and serum chemistry values for clinically healthy and sick pinnipeds. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 1993, 24, 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- Trumble, S.J.; Castellini, M.A. Blood chemistry, hematology and morphology of wild harbor seal pups in Alaska. J. Wildl. Manag. 2002, 66, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.W.; Jakush, J.L.; Simpson, A.; Norman, M.M.; Pabst, D.A.; Simmons, S. Evaluation of hematologic and biochemical values for convalescing seals from the coast of Maine. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2009, 40, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vail, M.; Beaufrère, H.; Gallini, S.; Paluch, H.; Brandão, J.; DiGeronimo, P.M. Hematologic and plasma biochemical prognostic indicators for stranded free-ranging phocids presented for rehabilitation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L.; Kumaresan, S.; Thomas, C.; MacWilliams, P. Hematology and chemistry reference values for free-ranging harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and the effects of hemolysis on chemistry values of captive harbor seals. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 1998, 29, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lander, M.E.; Harvey, J.T.; Gulland, F.M.D. Hematology and serum chemistry comparisons between free-ranging and rehabilitated harbor seal (Phoca vitulina richardii) pups. J. Wildl. Dis. 2003, 39, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahti, A. Partitioning biochemical reference data into subgroups: Comparison of existing methods. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004, 42, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryland, M.; Krafft, B.A.; Lydersen, C.; Kovacs, K.M.; Thoresen, S.I. Serum chemistry values for free-ranging ringed seals (Pusa hispida) in Svalbard. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 35, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, E.K.; Boyd, J.C. On dividing reference data into subgroups to produce separate reference ranges. Clin. Chem. 1990, 36, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, W.D.; Greenberg, I.D. Reference range determination—The problem of small sample sizes. J. Nucl. Med. 1991, 32, 2306–2310. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, W.J.; Bangert, S.K. Clinical Chemistry, 5th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Everds, N.E. Deciphering sources of variability in clinical pathology—It’s not just about the numbers: Preanalytical considerations. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 45, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazet, J.A.K.; Hamilton, G.E.; Dierauf, L.A. Educating veterinarians for careers in free-ranging wildlife medicine and ecosystem health. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2006, 33, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, S.L.; Riley, S.J.; Nelson, M.P. Promoting wildlife health or fighting wildlife disease: Insights from history, philosophy, and science. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 2012, 36, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Location | Time Period | Males | Females | Number of Animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shetland | 2022 | 8 | 21 | 29 |

| Orkney | 2016–2017 | 13 | 21 | 34 |

| Moray Firth | 2008–2025 | 63 | 56 | 119 |

| Eden Estuary | 1998–2000 | 33 | 33 | 66 |

| The Wash | 2023 | 22 | 15 | 37 |

| Islay | 2024 | 17 | 1 | 18 |

| Isle of Skye | 2017 | 10 | 4 | 14 |

| Total | 166 | 151 | 317 |

| Function | Parameter |

|---|---|

| Renal | Creatinine (µmol/L) |

| Phosphorous (mmol/L) | |

| Urea (mmol/L) | |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | |

| Hepatic | Alanine Transaminase (ALT) (U/L) |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) (U/L) | |

| Bilirubin (µmol/L) | |

| Nutritional status/ gastrointestinal | Glucose (mmol/L) |

| Cholesterol (mmol/L) | |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) (U/L) | |

| Total protein (g/L) | |

| Amylase (U/L) | |

| Lipase (U/L) | |

| Infection/inflammation | Globulin (g/L) |

| Albumin (g/L) | |

| Electrolytes | Sodium (mmol/L) |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | |

| Thyroid | Triiodothyronine (nmol/L) |

| Parameter | Sample Size | Lower 2.5th Percentile | Lower 90% CI | Upper 97.5th Percentile | Upper 90% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine µmol/L | 249 | 55.74 | 43.50–71.32 | 163.73 | 148.70–183.59 |

| Phosphorus mmol/L | 218 | 0.711 | 0.543–1.198 | 2.30 | 1.46–2.77 |

| Urea mmol/L | 251 | 12.29 | 11.38–13.49 | 22.18 | 19.27–28.03 |

| Calcium mmol/L | 218 | 1.92 | 1.87–1.96 | 2.54 | 2.50–2.66 |

| Alanine Transaminase (ALT) U/L | 251 | 2.54 | 1.00–5.00 | 66.85 | 43.61–115.07 |

| Gamma-glutamyl Transferase (GGT) U/L | 222 | 5.41 | 4.52–7.57 | 12.04 | 10.41–13.61 |

| Bilirubin µmol/L | 242 | 4.54 | 3.73–5.44 | 9.78 | 9.34–10.34 |

| Glucose mmol/L | 242 | 5.72 | 5.13–6.50 | 10.12 | 9.46–10.69 |

| Cholesterol mmol/L | 218 | 2.64 | 1.76–3.79 | 6.94 | 6.37–7.46 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) U/L | 248 | 6.14 | 4.89–7.43 | 45.59 | 31.24–57.89 |

| Total Protein g/L | 251 | 69.71 | 66.70–73.39 | 83.37 | 81.44–84.76 |

| Amylase U/L | 213 | 457.00 | 349.62–529.04 | 809.79 | 747.65–891.63 |

| Lipase U/L | 213 | 14.33 | 7.89–20.57 | 47.00 | 32.01–67.00 |

| Globulin g/L | 251 | 35.97 | 32.93–40.35 | 52.86 | 46.55–55.88 |

| Albumin g/L | 251 | 27.73 | 26.41–29.06 | 34.62 | 33.12–35.92 |

| Albumin: Globulin ratio | 251 | 0.537 | 0.518–0.626 | 0.864 | 0.793–0.918 |

| Sodium mmol/L | 221 | 145.57 | 143.90–146.94 | 153.69 | 153.10–154.60 |

| Potassium mmol/L | 221 | 3.28 | 3.23–3.61 | 4.47 | 4.13–4.57 |

| Chloride mmol/L | 219 | 102.10 | 100.75–103.23 | 109.80 | 109.14–110.22 |

| Total Triiodothyronine nmol/L | 271 | 0.160 | 0.954–0.212 | 1.770 | 0.822–3.160 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hall, A.J.; Russell, D.J.F.; Thompson, P.M.; Milne, R.; Moss, S.E.; Armstrong, H.C.; Kershaw, J.L. Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for Health Assessment in Wild Adult Harbour Seals. Animals 2025, 15, 3429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233429

Hall AJ, Russell DJF, Thompson PM, Milne R, Moss SE, Armstrong HC, Kershaw JL. Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for Health Assessment in Wild Adult Harbour Seals. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233429

Chicago/Turabian StyleHall, Ailsa J., Debbie J. F. Russell, Paul M. Thompson, Ryan Milne, Simon E. Moss, Holly C. Armstrong, and Joanna L. Kershaw. 2025. "Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for Health Assessment in Wild Adult Harbour Seals" Animals 15, no. 23: 3429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233429

APA StyleHall, A. J., Russell, D. J. F., Thompson, P. M., Milne, R., Moss, S. E., Armstrong, H. C., & Kershaw, J. L. (2025). Clinical Chemistry Reference Intervals for Health Assessment in Wild Adult Harbour Seals. Animals, 15(23), 3429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233429