Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) Exhibit Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Leaf Harvesting and Extract Preparation

2.2. GC–MS Analysis of Extracts and Compound Preparation

2.3. Cells, Bacteria, and Viruses

2.4. Assessment of Cytotoxicity

2.5. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

2.6. Bacterial Inhibition Assays

2.7. Viral Inhibition Assays

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

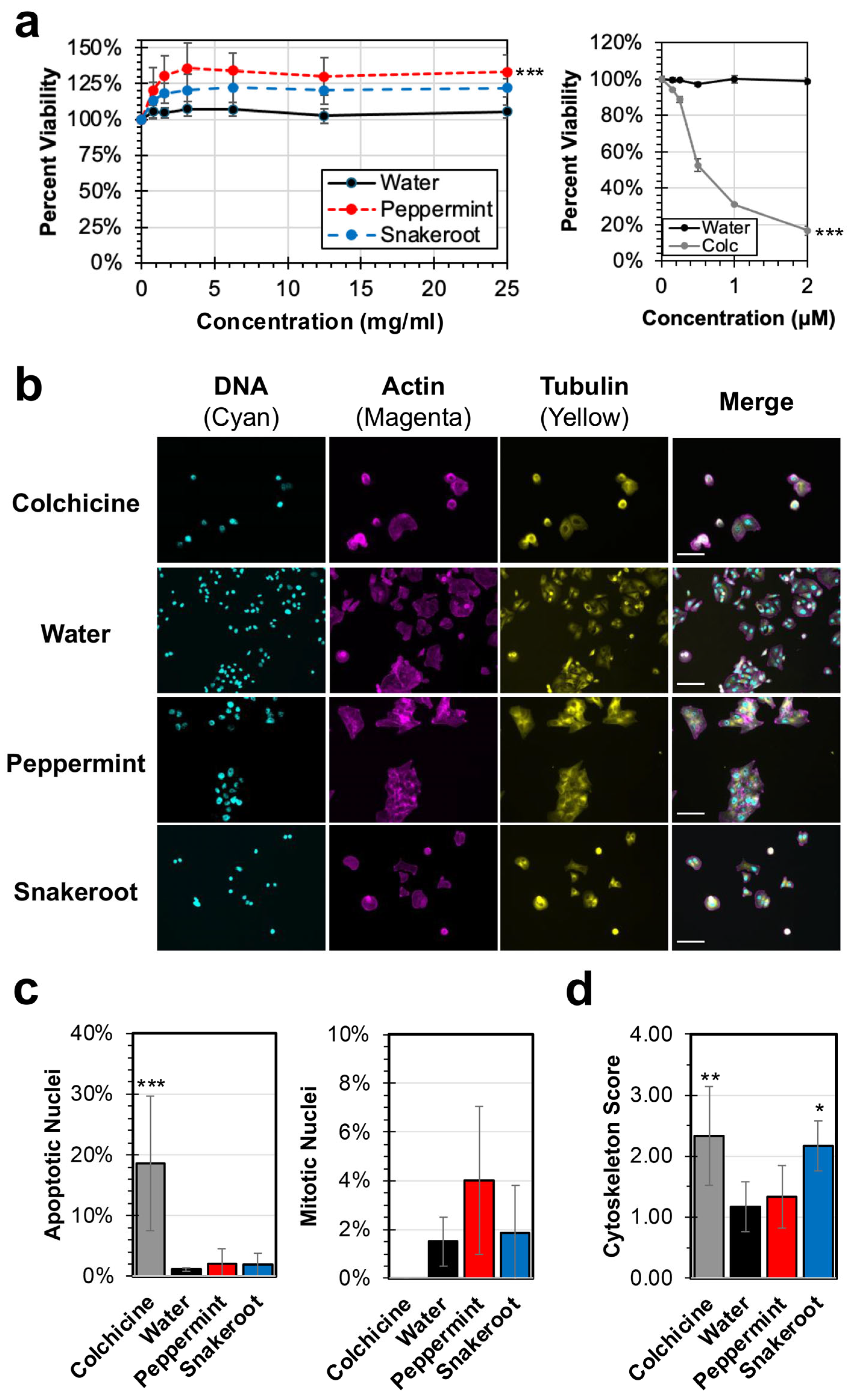

3.1. Peppermint (M. × piperita) and White Snakeroot (A. altissima) Extracts Show Limited Effects on the Replication and Proliferation of Cancer Cells In Vitro

3.2. Both Peppermint (M. × piperita) and White Snakeroot (A. altissima) Exhibit Significant Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity

3.3. Analysis of the Antiviral Activity of Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (M. × piperita) and White Snakeroot (A. altissima) Against a Murine Coronavirus Strain (MHV)

3.4. Chemical Analysis of Peppermint (M. × piperita) and White Snakeroot (A. altissima) Identify Several Major Chemical Constituents

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424, Erratum in CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, M.; Mairpady Shambat, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Antibiotic Resistance and Persistence—Implications for Human Health and Treatment Perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e51034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Bhattacharjee, U.; Chakrabarti, A.K.; Tewari, D.N.; Banu, H.; Dutta, S. Emergence of Novel Coronavirus and COVID-19: Whether to Stay or Die Out? Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.M. Plant Products as Antimicrobial Agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, R.; Ghazanfar, S.A.; Obied, H.; Vasileva, V.; Tariq, M.A. Ethnobotany: A Living Science for Alleviating Human Suffering. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 2016, e9641692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.; Lo, C.-W.; Einav, S. Preparing for the next Viral Threat with Broad-Spectrum Antivirals. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e170236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Stobart, C.C.; Hotard, A.L.; Moore, M.L. An Overview of Respiratory Syncytial Virus. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudz, N.; Kobylinska, L.; Pokajewicz, K.; Horčinová Sedláčková, V.; Fedin, R.; Voloshyn, M.; Myskiv, I.; Brindza, J.; Wieczorek, P.P.; Lipok, J. Mentha Piperita: Essential Oil and Extracts, Their Biological Activities, and Perspectives on the Development of New Medicinal and Cosmetic Products. Molecules 2023, 28, 7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, A.R. A Handbook of Native American Herbs: The Pocket Guide to 125 Medicinal Plants and Their Uses; Shambhala Publications: Boulder, CO, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8348-2422-5. [Google Scholar]

- Keifer, D.; Ulbricht, C.; Abrams, T.R.; Basch, E.; Giese, N.; Giles, M.; DeFranco Kirkwood, C.; Miranda, M.; Woods, J. Peppermint (Mentha Piperita): An Evidence-Based Systematic Review by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. J. Herb. Pharmacother. 2007, 7, 91–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, A.; Rahmoune, C.; Boumendjel, M.; Aissi, O.; Messaoud, C. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Six Wild Mentha Species (Lamiaceae) from Northeast of Algeria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2016, 6, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoghachi, F.E.H.; Almousawei, U.M.N.; Shari, F.H. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of RA Extracts of Peppermint Leaves against Human Cancer Breast and Cervical Cancer Cells. Teikyo Med. J. 2022, 45, 3467. [Google Scholar]

- Naksawat, M.; Norkaew, C.; Charoensedtasin, K.; Roytrakul, S.; Tanyong, D. Anti-Leukemic Effect of Menthol, a Peppermint Compound, on Induction of Apoptosis and Autophagy. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, A.; Bao, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, Z. In Vitro Antiviral, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidant Activities of the Ethanol Extract of Mentha piperita L. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loolaie, M.; Moasefi, N.; Rasouli, H.; Adibi, H. Peppermint and Its Functionality: A Review. Arch. Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, T.Z.; Stegelmeier, B.L.; Lee, S.T.; Collett, M.G.; Green, B.T.; Pfister, J.A.; Evans, T.J.; Grum, D.S.; Buck, S. White Snakeroot Poisoning in Goats: Variations in Toxicity with Different Plant Chemotypes. Res. Vet. Sci. 2016, 106, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Choi, J.; Song, W. Introduction and Spread of the Invasive Alien Species Ageratina altissima in a Disturbed Forest Ecosystem. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulus, K.R.; Marshall, J.M. Competitive Interactions between Two Non-Native Species (Alliaria petiolata [M. Bieb.] Cavara & Grande and Hesperis matronalis L.) and a Native Species (Ageratina altissima [L.] R.M. King & H. Rob.). Plants 2022, 11, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essl, F. The Distribution of Ageratina altissima (L.) R. M. King & H. Rob. in Austria. BioInvasions Rec. 2025, 14, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, R.C.; Norman, J.O.; Reagor, J.C.; Rees, M.S.; Mundy, B.P. Isolation of the Major Component in White Snakeroot That Is Toxic after Microsomal Activation: Possible Explanation of Sporadic Toxicity of White Snakeroot Plants and Extracts. Nat. Toxins 1993, 1, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians. Extension Center; Cozzo, D. Cherokee Snakebite Remedies. South. Anthropol. Soc. Proc. 2013, 41, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Cerecero, O.; Zamilpa-Álvarez, A.; Ramos-Mora, A.; Alonso-Cortés, D.; Jiménez-Ferrer, J.E.; Huerta-Reyes, M.E.; Tortoriello, J. Effect on the Wound Healing Process and In Vitro Cell Proliferation by the Medicinal Mexican Plant Ageratina Pichinchensis. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, T.H.; da Rocha, C.Q.; Delgado-Roche, L.; Rodeiro, I.; Ávila, Y.; Hernández, I.; Cuellar, C.; Lopes, M.T.P.; Vilegas, W.; Auriemma, G.; et al. Influence of the Phenological State of in the Antioxidant Potential and Chemical Composition of Ageratina havanensis. Effects on the P-Glycoprotein Function. Molecules 2020, 25, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, P.; Witte, L.; Wray, V. Chromene Glycosides from Ageratina altissima. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 3690–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Davis, T.Z.; Gardner, D.R.; Stegelmeier, B.L.; Evans, T.J. Quantitative Method for the Measurement of Three Benzofuran Ketones in Rayless Goldenrod (Isocoma pluriflora) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 5639–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinu, F.R.; Villas-Boas, S.G. Rapid Quantification of Major Volatile Metabolites in Fermented Food and Beverages Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Metabolites 2017, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, E.N.; Link, N.G.; Jackson, M.R.; Alvi, A.F.; Moehlenkamp, J.N.; Beard, M.B.; Simons, A.R.; Carson, L.C.; Li, R.; Judd, B.T.; et al. Evaluation of the Therapeutic Potential of Traditionally-Used Natural Plant Extracts to Inhibit Proliferation of a HeLa Cell Cancer Line and Replication of Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus (hRSV). Biology 2024, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korch, C.T.; Capes-Davis, A. The Extensive and Expensive Impacts of HEp-2 [HeLa], Intestine 407 [HeLa], and Other False Cell Lines in Journal Publications. SLAS Discov. Adv. Life Sci. R&D 2021, 26, 1268–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotard, A.L.; Shaikh, F.Y.; Lee, S.; Yan, D.; Teng, M.N.; Plemper, R.K.; Crowe, J.E.; Moore, M.L. A Stabilized Respiratory Syncytial Virus Reverse Genetics System Amenable to Recombination-Mediated Mutagenesis. Virology 2012, 434, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barltrop, J.A.; Owen, T.C.; Cory, A.H.; Cory, J.G. 5-(3-Carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4,5-Dimethylthiazolyl)-3-(4-Sulfophenyl)Tetrazolium, Inner Salt (MTS) and Related Analogs of 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazolyl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Reducing to Purple Water-Soluble Formazans As Cell-Viability Indicators. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1991, 1, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, P.R.; Mondhe, D.M. Potential Anticancer Role of Colchicine-Based Derivatives: An Overview. Anticancer Drugs 2017, 28, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cui, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, P.; Cao, X.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; He, Q. Colchicine Inhibits the Proliferation and Promotes the Apoptosis of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Cells Likely Due to the Inhibitory Effect on HDAC1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 679, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, M.; Nabi, B.; Daswani, M.; Viquar, I.; Pal, N.; Sharma, P.; Tiwari, S.; Sarma, D.K.; Shubham, S.; Kumar, M. Role of Bacterial Efflux Pump Proteins in Antibiotic Resistance across Microbial Species. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 181, 106182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorusso, A.B.; Carrara, J.A.; Barroso, C.D.N.; Tuon, F.F.; Faoro, H. Role of Efflux Pumps on Antimicrobial Resistance in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, E.; Brenciani, A.; Burioni, R.; Varaldo, P.E. A Novel Efflux System in Inducibly Erythromycin-Resistant Strains of Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3750–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portillo, A.; Lantero, M.; Gastañares, M.J.; Ruiz-Larrea, F.; Torres, C. Macrolide Resistance Phenotypes and Mechanisms of Resistance in Streptococcus pyogenes in La Rioja, Spain. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 1999, 13, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, V.L.S.; dos Santos, J.C.; Martins, J.R.; Schripsema, J.; Siqueira, I.R.; von Poser, G.L.; Apel, M.A. Acaricidal Properties of the Essential Oil and Precocene II Obtained from Calea serrata (Asteraceae) on the Cattle Tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 179, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrankel, K.R.; Grossman, S.J.; Hsia, M.T. Precocene II Nephrotoxicity in the Rat. Toxicol. Lett. 1982, 12, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmawan, Y.P.; Anggadiredja, K.; Adnyana, I.K. Anti-Neuropathic Pain Mechanistic Study on A. Conyzoides Essential Oil, Precocene II, Caryophyllene, or Longifolene as Single Agents and in Combination with Pregabalin. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2023, 22, 924–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrant, C.; Cupp, E.W.; Bowers, W.S. The Effects of Precocene II on Reproduction and Development of Triatomine Bugs (Reduviidae: Triatominae). Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1982, 31, 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelešius, R.; Karpovaitė, A.; Mickienė, R.; Drevinskas, T.; Tiso, N.; Ragažinskienė, O.; Kubilienė, L.; Maruška, A.; Šalomskas, A. In Vitro Antiviral Activity of Fifteen Plant Extracts against Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leka, K.; Hamann, C.; Desdemoustier, P.; Frédérich, M.; Garigliany, M.; Ledoux, A. In Vitro Antiviral Activity against SARS-CoV-2 of Common Herbal Medicinal Extracts and Their Bioactive Compounds. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 3013–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Plant Extract | Chemical 1 | Approx. Concentration 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Peppermint | 1,8-Cineole (eucalyptol) | 0.56 M |

| α-Terpineol | 0.66 mM | |

| 4-isopropyl-1-methylcyclohexanol (p-Menthan-1-ol) | 5.01 mM | |

| Menthol | 4.97 mM | |

| Snakeroot | Precocene II | 6.97 mM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yurchiak, M.E.; Bailey, S.; Sakib, A.H.; Smith, M.M.; Lally, R.; DuBrava, J.W.; Roe, K.M.; Stuart, O.; Shafier, A.E.; Kim, J.; et al. Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) Exhibit Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010080

Yurchiak ME, Bailey S, Sakib AH, Smith MM, Lally R, DuBrava JW, Roe KM, Stuart O, Shafier AE, Kim J, et al. Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) Exhibit Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleYurchiak, Mackenzie E., Shea Bailey, Aarish H. Sakib, Macy M. Smith, Rachael Lally, Jacob W. DuBrava, Keely M. Roe, Orna Stuart, Abigail E. Shafier, Juhee Kim, and et al. 2026. "Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) Exhibit Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010080

APA StyleYurchiak, M. E., Bailey, S., Sakib, A. H., Smith, M. M., Lally, R., DuBrava, J. W., Roe, K. M., Stuart, O., Shafier, A. E., Kim, J., Susick, L. D., Prassas, L., Voss, A. L., O’Malley, G. C., Calvo, S., Magnus, M. B., Berthrong, S. T., Wilson, A. M., Trombley, M. P., ... Stobart, C. C. (2026). Aqueous Leaf Extracts of Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) and White Snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) Exhibit Antibacterial and Antiviral Activity. Microorganisms, 14(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010080