Abstract

To address the thermal management challenges of high-heat-flux electronic devices, this study investigates heat transfer enhancement in microchannels with composite cavity-rib triangular prism structures through numerical simulations. Three cavity configurations (arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal) with depths ranging from 0.2 to 0.35 mm were analyzed. The results reveal that increasing the cavity depth elevated the friction resistance, with the trapezoidal cavities exhibiting the highest increase in friction resistance at Re > 550. The heat transfer performance exhibited a nonlinear improvement with depth: arc-shaped cavities (D = 0.35 mm) achieved maximum Nusselt numbers at low Reynolds numbers, whereas trapezoidal cavities excelled at high Reynolds numbers. The thermal-hydraulic performance evaluation criterion (PEC) identified the arc-shaped cavity (D = 0.35 mm) as optimal, achieving a maximum PEC value of 1.7495, which surpassed the rectangular and trapezoidal configurations by 4.3% and 0.7%, respectively. This study demonstrates that composite cavity-rib structures enhance secondary flow disturbances, providing critical insights for cross-scale parameter optimization in microchannel design.

1. Introduction

Microchannel heat sinks have become a critical technology for the thermal management of high-power electronic devices, including advanced computing processors, laser systems, and microelectromechanical systems [1,2,3]. The continuous advancement of semiconductor technology and the ongoing miniaturization of integrated circuits have led to a sharp increase in heat flux density, with local hotspots in contemporary large-scale electronic devices exceeding 1000 W/cm2 [4,5]. Due to inherent limitations in heat transfer capacity, traditional air-cooling methods can no longer meet the cooling demands of these high-density applications [6,7]. In contrast, microchannel heat sinks offer significant advantages such as compact structure, low energy consumption, and high heat transfer efficiency, making them a fundamental solution for addressing thermal management challenges in high-heat-flux scenarios [8,9]. The thermal performance of traditional rectangular microchannels is constrained by their simple geometric shapes, which limits further improvements in heat transfer efficiency [10]. As emphasized by Tuckerman and Pease [1] in their pioneering work, the fundamental challenge lies in overcoming the development of thermal boundary layers while maintaining acceptable pressure drops. Recent studies by He et al. [2] and Khattak et al. [4] comprehensively review various enhancement strategies, highlighting structural modifications as the most promising approach for performance improvement. Research efforts primarily focus on two distinct enhancement mechanisms: ribbed structures and grooved structures. Ribbed structures (e.g., triangular or rhombic ribs) enhance heat transfer by inducing eddy currents and disrupting thermal boundary layers. Datta et al. [11] conducted a comprehensive comparative study of various rib geometries, demonstrating that rhombic ribs achieve optimal thermal performance through enhanced fluid mixing. Similarly, Derakhshanpour et al. [12] investigated modified semi-circular and elliptical ribs, reporting an 18–21% increase in Nusselt number compared to smooth channels. These studies confirmed that the rib structures effectively enhance turbulence and secondary flow, thereby improving the heat transfer coefficient.

An Hao et al. [13] investigated the effects of TSV (through-silicon-via) cross-sectional geometry and aspect ratio on flow heat transfer performance in microchannels. The study revealed that for aligned TSV microchannels, lower aspect ratios of TSV cross-sections resulted in reduced flow resistance. Circular TSV cross-section systems achieved minimal temperature rise within specific aspect ratio ranges, whereas square cross-section TSVs exhibited the highest pressure drop.

Zhang et al. [14] conducted a comparative analysis of the hydraulic-thermal performance between twisted and inclined ribs, revealing their distinct characteristics in flow and heat transfer. The study found that both rib designs significantly improved heat transfer efficiency within microchannels compared to straight rib structures, though they also substantially increased flow resistance. While inclined ribs demonstrated superior heat transfer performance, the twisted rib configuration achieved the most comprehensive performance. The research revealed that when the Reynolds number was 239, with rib height set at 0.5 mm, a 45° twist angle at the bottom, and 0° at the top, the microchannel’s comprehensive performance evaluation factor reached its peak value of 1.34.

Chen Tao et al. [15] investigated the flow and heat transfer characteristics of microchannels with staggered internal ribs through numerical simulation, examining how four rib configurations—rectangular, rhombic, triangular, and circular—affected heat transfer performance. The study revealed that all ribbed microchannels exhibited higher Nusselt numbers than rectangular microchannels, yet their friction coefficients reached up to 17.5 times higher than those of rectangular microchannels.

Li Juan et al. [16] developed a biomimetic fish-scale ribbed microchannel structure by replicating fish scales, investigating how structural parameters (relative width, height, and span angle) affect performance. Through uniform experimental design and numerical simulations, they demonstrated that the unique rib structure enhances fluid flow and mixing, improving heat transfer efficiency. The study revealed significant impacts of relative height and width on the structure. Optimizing rib parameters substantially reduces flow loss and expands secondary flow diffusion areas, thereby boosting overall heat transfer performance. When the Reynolds number reaches 1300, the biomimetic ribbed microchannel achieves optimal heat transfer performance with a numerical value of approximately 1.55.

Zeng et al. [17] investigated the heat dissipation efficiency of microchannel heat sinks with both inline and staggered open-ring rib structures for enhanced heat transfer. Using experimental and numerical simulations, they systematically analyzed the flow and heat transfer characteristics of these configurations and compared them with standard rectangular microchannels. The study revealed that the Nusselt numbers of the novel microchannel designs increased by 56–220% and 77–260%, respectively, compared to conventional rectangular microchannels.

Polat et al. [18] conducted an optimization analysis of the performance of microchannels with interlaced rhombic rib columns, employing a genetic algorithm based on non-dominated sorting (NSGA-II) and a multi-layer neural network model to predict and evaluate individual performance. The results demonstrated that the microchannels exhibited optimal hydrothermal performance when the longitudinal section-to-diameter ratio of the rhombic rib columns was set to 2.5, with pin-fin Reynolds numbers of 20 or 100.

In contrast, groove structures—including arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal configurations—reduce flow resistance while enhancing heat transfer by creating recirculation zones. Ahmed and Ahmed [19] systematically investigated triangular, trapezoidal, and rectangular groove microchannels, determining the optimal geometric parameters for each configuration. Their findings demonstrated that trapezoidal grooves exhibit superior performance at higher Reynolds numbers due to more efficient boundary layer disruption. Pan et al. [20] experimentally demonstrated that fan-shaped cavities can increase heat transfer by up to 35% compared to conventional channels, attributing this improvement to optimized vortex formation and flow separation characteristics.

Fan Xiangguang et al. [21] investigated microchannels with rectangular, trapezoidal, triangular, and circular grooves. Their analysis of flow and heat transfer performance demonstrated that grooved channels exhibit superior thermal performance compared to straight channels at low Reynolds numbers. However, as Reynolds numbers increase, pressure drop rises significantly while Nusselt number growth slows down, with triangular and circular grooves showing the highest Nusselt number growth rates.

Hou et al. [22] introduced elliptical grooves into microchannels to optimize their thermo-hydrodynamic performance. The study found that reducing flow pressure drop through arc-shaped grooves significantly improved the overall heat transfer efficiency of microchannels, with the effect becoming more pronounced as the arc radius increased.

Liu et al. [23] investigated the mechanism of groove-enhanced single-phase flow by analyzing velocity, temperature, and pressure fields in microchannels. Their findings revealed that groove-induced eddy currents alter streamline distribution, enabling fluid impact on walls and thus improving heat transfer efficiency. Based on these results, they developed a dual-layer groove microchannel heat sink. Compared to single-layer microchannel heat sinks, this design demonstrates significantly enhanced heat transfer performance.

The groove structure serves dual purposes: regulating temperature field uniformity while controlling pressure drop and enhancing heat transfer efficiency. To achieve superior temperature uniformity, Zhang et al. [24] designed serrated, wavy, and square-wave grooves in counter-flow microchannel heat sinks. Comparative studies revealed that among various groove configurations, the serrated microchannel heat sink demonstrated the most effective energy consumption and temperature uniformity. Its optimized structural parameters can withstand thermal flux densities up to 11.15 × 105 W/m2.

The integration of rib and groove features into composite structures marks a promising advancement in microchannel design. Zhang et al. [25] investigated various cavity-rib combination patterns in microchannels, demonstrating synergistic effects that surpass individual reinforcement mechanisms. Their comprehensive research revealed that properly designed composite structures can achieve 40–60% thermal performance improvements while maintaining reasonable pressure drop losses. Similarly, Chai et al. [26] studied discontinuous microchannels with transverse microcavity ribs, reporting significant enhancements in heat transfer and flow characteristics. These findings were corroborated by Jamshidmofid and Bahiraei [27], who incorporated cobalt oxide-modified reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites into microchannels with sinusoidal cavities and rectangular ribs, achieving outstanding thermo-hydrodynamic performance.

Ye et al. [28] conducted a numerical analysis on the heat transfer characteristics of nanofluids in composite microchannels with fan-shaped grooves and elliptical ribs. The results demonstrated that at a Reynolds number of 398, the overall performance of the optimized microchannel parameters improved by 33% compared to rectangular microchannels. The enhancement mechanism was further elucidated using field synergy theory.

Yao et al. [29] conducted a multi-objective optimization analysis of composite microchannels in triangular groove composite ribbed columns using non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) and response surface methodology (RSM), based on field synergy theory. The optimization variables included groove height, rib height, and Reynolds number. The study revealed that after multi-objective optimization, the temperature difference between the heating wall and the fluid decreased from 26 K to 17 K. Furthermore, the optimized microchannels exhibited better field synergy characteristics in both velocity and temperature fields, resulting in a significant improvement in overall heat transfer performance.

Zhu et al. [30] proposed an optimized microchannel structure featuring droplet-shaped grooves, with uniformly distributed rectangular, triangular, rhombic, elliptical, and trapezoidal ribs at the groove center to enhance flow and heat transfer performance. The study demonstrated that this design combines the advantages of both rib structures and droplet-shaped grooves: it improves heat transfer efficiency by enhancing fluid mixing while effectively reducing flow resistance through the groove configuration. The combination of droplet-shaped grooves and elliptical ribs achieved optimal comprehensive performance, with a composite microchannel achieving a comprehensive performance coefficient of 1.513 at a Reynolds number (Re) of 331.32.

Zhang et al. [31] conducted a systematic analysis and evaluation of single-phase flow heat transfer characteristics in composite microchannel heat sinks incorporating triangular grooves, fan-shaped grooves, composite triangular-groove cylindrical ribs, rectangular ribs, and droplet-shaped ribs. The study focused on comparing the performance of different microchannel structures in terms of flow characteristics, pressure loss, heat transfer efficiency, comprehensive thermodynamic performance, and energy-saving properties. The findings revealed that under medium-to-high Reynolds number conditions, microchannel structures with fan-shaped grooves and composite triangular grooves demonstrated superior overall performance. In contrast, under low Reynolds number conditions, composite triangular-groove microchannels exhibited the best performance.

Rajalingam et al. [32,33] introduced a composite structure combining differently shaped grooves and rib columns into microchannels, conducting research on flow and heat transfer performance through numerical simulation. The study revealed that the rib column structure promoted fluid separation and enhanced turbulence, but also resulted in significant pressure drop, which was detrimental to energy loss reduction. The groove structure had minimal impact on heat transfer performance but facilitated comprehensive fluid flow development within the microchannels, reducing pressure drop and thereby decreasing overall energy loss. Subsequent research on microchannels with composite groove-rib column structures of varying shapes demonstrated that by appropriately adjusting structural parameters, the periodic flow and heat transfer boundary separation and convergence were effectively enhanced, leading to a substantial improvement in the microchannels’ overall performance.

Recent investigations have further enhanced our understanding of composite microchannel behavior, yet systematic studies on the synergistic effects of composite groove-rib structures, particularly in cross-scale parameter optimization, remain insufficient. Chai et al. [34] conducted parameter studies on microchannels with fan-shaped ribs, but their work primarily focused on rib configurations without considering groove interactions. Similarly, Li et al. [35] performed thermodynamic analyses on microchannels with cavities and fins, but their research lacked comprehensive variations in groove geometry and depth. A key research gap identified in the current literature involves systematic evaluation of different groove geometries (arc-shaped, rectangular, trapezoidal) combined with triangular prism ribs under varying depth parameters (0.2–0.35 mm). Liang et al. [36] recently reviewed bionic microchannel structures and their topological optimization, emphasizing the need for more comprehensive studies on geometric parameter effects. Chai et al. [37] concurred with this view, having studied the thermo-hydraulic performance of microchannels with triangular ribs while acknowledging the limitations of geometric diversity. This study addresses these research gaps through systematic investigations of composite cavity-rib triangular prism microchannels with three distinct groove geometries and five depth variations. Our work builds upon the latest advancements in sustainable cooling technologies, aligning with Qiu et al. [38]’s emphasis on achieving building decarbonization through energy efficiency innovations. Furthermore, we incorporated insights from Zhang et al. [39], who investigated flow and heat transfer characteristics in microchannels with high-frequency ultrasound, recognizing the importance of advanced enhancement techniques. Integrating these perspectives with fundamental thermodynamic principles provides a comprehensive framework for our research. The primary scientific contribution of this study lies in its rigorous cross-scale parameter analysis, which quantitatively elucidates the synergistic mechanisms of groove geometry and depth on thermo-hydrodynamic performance across a wide Reynolds number range (223–670). Unlike previous studies focusing on limited parameter ranges or single enhancement mechanisms, our research delivers a comprehensive performance atlas essential for engineering design. Through detailed analysis of vortex dynamics, flow separation effects, and entropy production mechanisms, we establish clear design guidelines for optimal microchannel configurations in high-heat-flux applications.

2. Methods

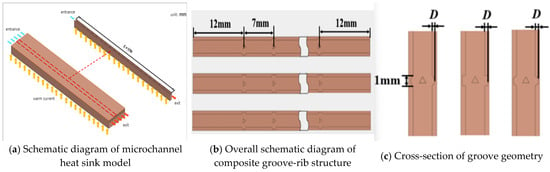

2.1. Physical Model

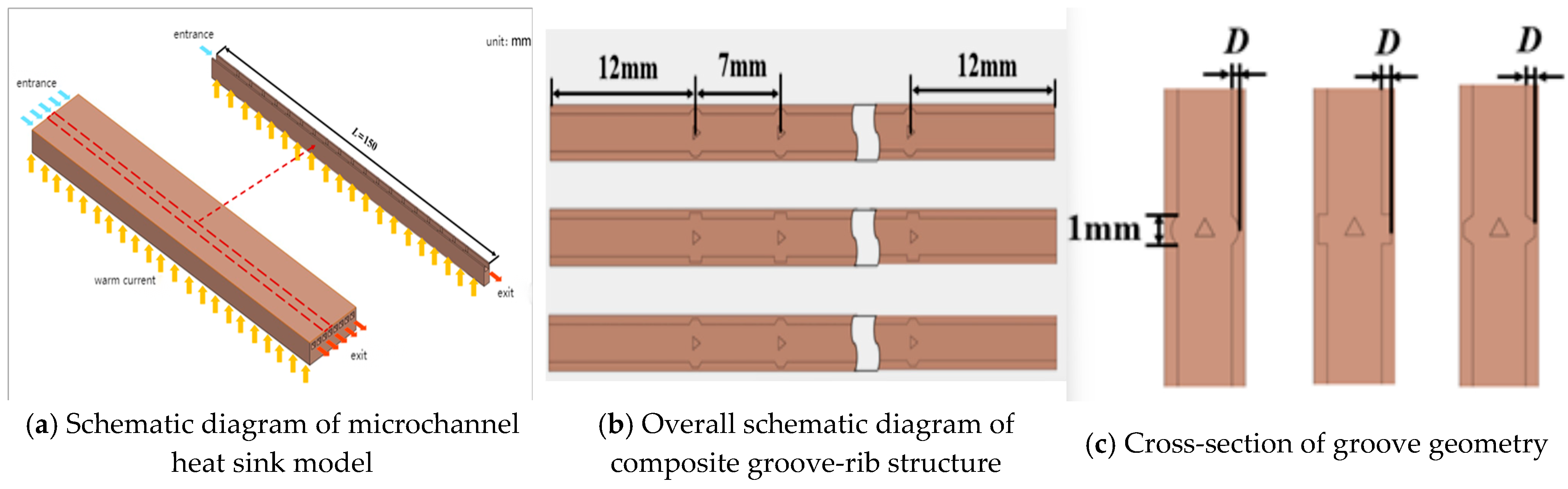

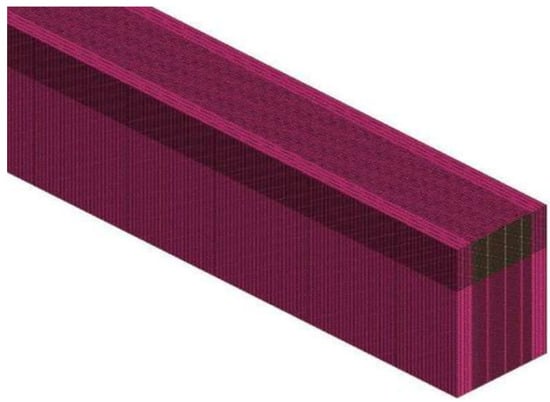

Figure 1 illustrates a microchannel model with a groove-embedded triangular prism. The microchannel heat sink model measures 150 mm in length (L), 3 mm in width (W), and 7 mm in height (H). Each individual microchannel has a width (Ws) and height (Hs) of 2 mm, featuring regularly arranged triangular prisms along the flow direction (7 mm spacing, 0.7 mm side length). The corresponding curved, rectangular, and trapezoidal grooves (labeled MC-ARC-D0.2, MC-RC-D0.2, and MC-TRC-D0.2, respectively) were integrated into the channel walls, with D0.2 denoting a groove depth of 0.2 mm. The channel bottom wall integrates arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal grooves. The radius of the arc-shaped groove is equal to its depth (D). The width of the rectangular groove is 0.4 mm. The upper base width of the trapezoidal groove is 0.4 mm, the lower base width is 0.2 mm, and the side angle with the bottom wall is 60 degrees. The studied groove depths (D) range from 0.2 mm to 0.35 mm, with an interval of 0.05 mm. These dimensions are compatible with common microfabrication techniques (e.g., precision milling and lithography), and their scale is suitable for localized hot spot cooling in high-power chips. The selected trench depth (0.2–0.35 mm) and channel dimensions are compatible with common microfabrication techniques such as precision milling and lithography. These dimensions are particularly suitable for cooling high-power electronic chips, where local hot spot management is critical, enabling the results of this study to be directly applied to the thermal design of next-generation 5G communication devices and high-performance computing processors.

Figure 1.

Microchannel model.

The studied groove depths (D) range from 0.2 to 0.35 mm, with an interval of 0.05 mm. The selection of these specific dimensions is rigorously justified from both fabrication and application perspectives: The chosen dimensions are well within the capabilities of modern microfabrication technologies. For instance, precision milling, a widely used technique for manufacturing metal heat sinks, can achieve feature sizes down to 100 μm (0.1 mm) with high repeatability [34]. Similarly, lithography-based techniques, suitable for silicon-based microchannels, can easily define structures at the micrometer scale. Therefore, the groove depths (200–350 μm) and channel widths (2 mm) considered in this study are not only feasible but also conducive to cost-effective mass production. The dimensions are strategically selected to address the cooling challenges of contemporary and next-generation high-power electronic devices. Localized hot spots in advanced chips (e.g., CPUs, GPUs, and 5G RF amplifiers) already exhibit heat fluxes exceeding 1000 W/cm2 [10,11], with hot spot dimensions typically on the order of several millimeters down to a few hundred micrometers.

The hydraulic diameter (Dh = 2 mm) of our microchannel ensures a high surface-area-to-volume ratio for efficient heat transfer, while the sub-millimeter groove depths (0.2–0.35 mm) are optimized to generate significant secondary flow disturbances—crucial for disrupting the thermal boundary layer—without inducing prohibitively high pressure drops that would be impractical for compact cooling systems. This scale directly corresponds to the size of thermal hotspots in high-performance computing processors and 5G communication chips, enabling the direct application of our findings to the thermal management design of these devices.

2.2. Mathematical Modeling

2.2.1. Numerical Model

The numerical model in this study was divided into solid and fluid domains. The solid domain uses copper as the substrate with a thermal conductivity of 387.6 W/(m·K), whereas the fluid domain employs water as the material whose physical properties vary with temperature [17]. Assuming three-dimensional steady-state incompressible laminar heat transfer processes and neglecting gravitational forces, volumetric forces, thermal radiation, and viscous dissipation effects, the continuity, momentum, and energy equations for the fluid domain are simplified to

In the solid domain, the velocity is zero and only the equation of energy conservation is retained:

At the microchannel inlet, uniform velocity boundary conditions were applied with a constant temperature (Tin = 298 K). Pressure boundary conditions were implemented at the outlet. The bottom heating wall was heated by a constant heat flux of qw = 1 × 105 W/m2. The fluid–structure interface is governed by fluid–structure interaction boundary conditions, whereas the other walls are specified as adiabatic walls with no velocity slip or permeability.

The Reynolds number (Re) of the microchannel based on the inlet parameters was calculated as follows:

where ρin and μin are the fluid density and viscosity at the inlet of the microchannel, respectively; uin represents the average velocity of the fluid at the inlet of the microchannel; and Dh is the hydraulic diameter of the microchannel.

The average friction coefficient (f) of the fluid in the microchannel is as follows:

where L is the length of the microchannel, ρm is the average volume density of the entire fluid domain, ∆P pressure drops at inlet and outlet, and the average Nuessel number (Nu) of the microchannel is determined by the following formula:

The formula is a common definition of the average heat transfer coefficient of microchannel heat sink. Where λf is the mass average heat transfer coefficient of the fluid, and the average heat transfer coefficient, havg, is calculated as follows:

In this formula, Aw, Asf, Tw,avg and TOUT are the heating wall area, fluid-liquid heat transfer area, average heating wall temperature and fluid outlet temperature, respectively.

To evaluate the overall heat transfer performance in the microchannel, a comprehensive performance evaluation criterion (PEC) is defined as

In this formula, the subscript ‘0’ represents the result without grooves.

The study assumes steady-state laminar flow throughout the Reynolds number range (Re ≤ 670). This assumption holds true for microchannels with millimeter-scale hydraulic diameters, as their transition to turbulence typically occurs at higher Reynolds numbers (Re > 2000–3000) compared to macrochannels. Although complex vortex structures were observed at elevated Reynolds numbers in this research, these are characteristic of laminar separation flow and do not indicate fully developed turbulence. However, it should be acknowledged that local instability may exist, and this assumption represents a widely accepted simplification in similar microchannel studies [11,17].

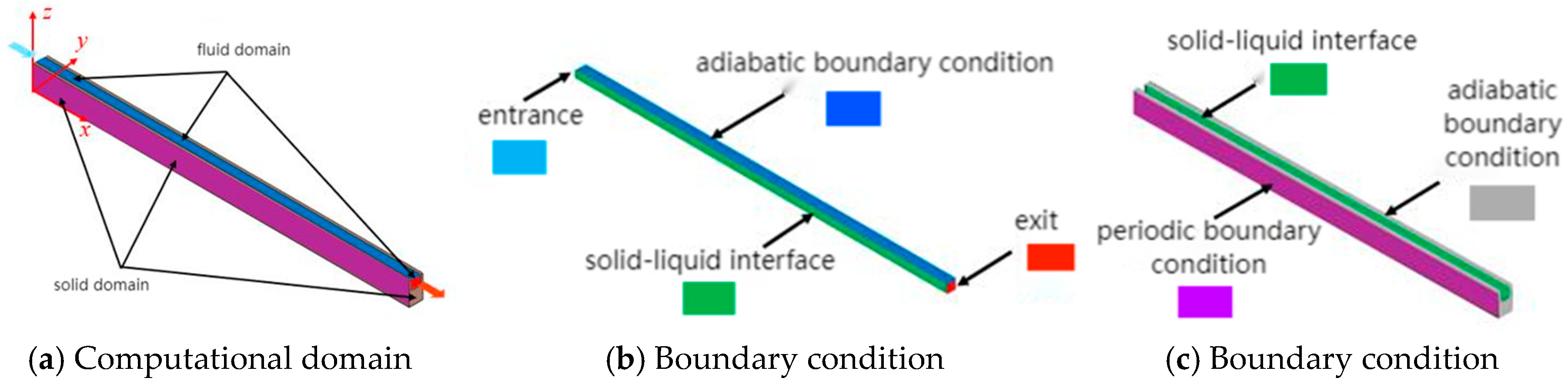

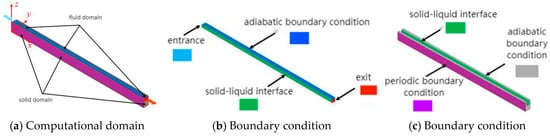

2.2.2. Boundary Condition Setting

Numerical Discretization Methodology The finite volume method (FVM) is employed for spatial discretization of the governing equations. The mathematical formulation involves: Second-order upwind scheme for momentum and energy equations; Pressure-velocity coupling via the SIMPLE algorithm; Second-order central differencing for diffusion terms; Convergence criteria: 10−6 for continuity, 10−10 for energy, 10−8 for momentum equations.

The mathematical robustness of this discretization scheme ensures conservation of mass, momentum, and energy throughout the computational domain.

This study employs the boundary conditions illustrated in Figure 2. The microchannel inlet (x = 0) is subjected to an isothermal and constant-velocity boundary condition, with the inlet velocity uin = 0.1~0.4 m/s and inlet temperature maintained at Tin = 298 K. The outlet (x = 150 mm) is subjected to a pressure boundary condition (Pout = 0). For thermal boundary conditions, a constant heat flux density qw = 1 × 105 W/m2 is applied at the heat sink base (z = 0), while the solid domain walls (y = 0 and y = 3 mm) are treated with periodic temperature and heat flux boundary conditions. The fluid-solid interface is governed by a conjugate heat transfer coupling mechanism to ensure temperature continuity and heat flux conservation. Other microchannel walls are subjected to non-slip and non-permeable (V = 0) boundary conditions with adiabatic properties (∂T/∂n = 0).

Figure 2.

Computational domain and boundary conditions.

The numerical solver employs the Finite Volume Method (FVM) to discretize the governing equations, with the energy, momentum, and mass equations using second-order windward discretization schemes. Pressure-velocity coupling is implemented through the Coupled algorithm. The computations were performed in ANSYS Fluent 2022 R1, with convergence residual thresholds set at 10−6 for the continuity equation, 10−10 for the energy equation, and 10−8 for the momentum equation. A maximum of 1000 iteration steps were imposed to ensure computational stability.

2.3. Material Property Parameters

The solid domain material in the microchannel studied in this paper is copper. Due to its high thermal conductivity, copper can achieve high processing precision in practical engineering applications and is commonly used as a heat dissipation substrate material. Its thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, and density are 398 W/(m·K), 381 J/(kg·K), and 8978 kg/m2, respectively. The fluid domain uses deionized water as the working fluid. The density and specific heat capacity of deionized water are affected by temperature and exhibit piecewise linear changes. The specific physical properties are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thermophysical properties table of saturated water [40].

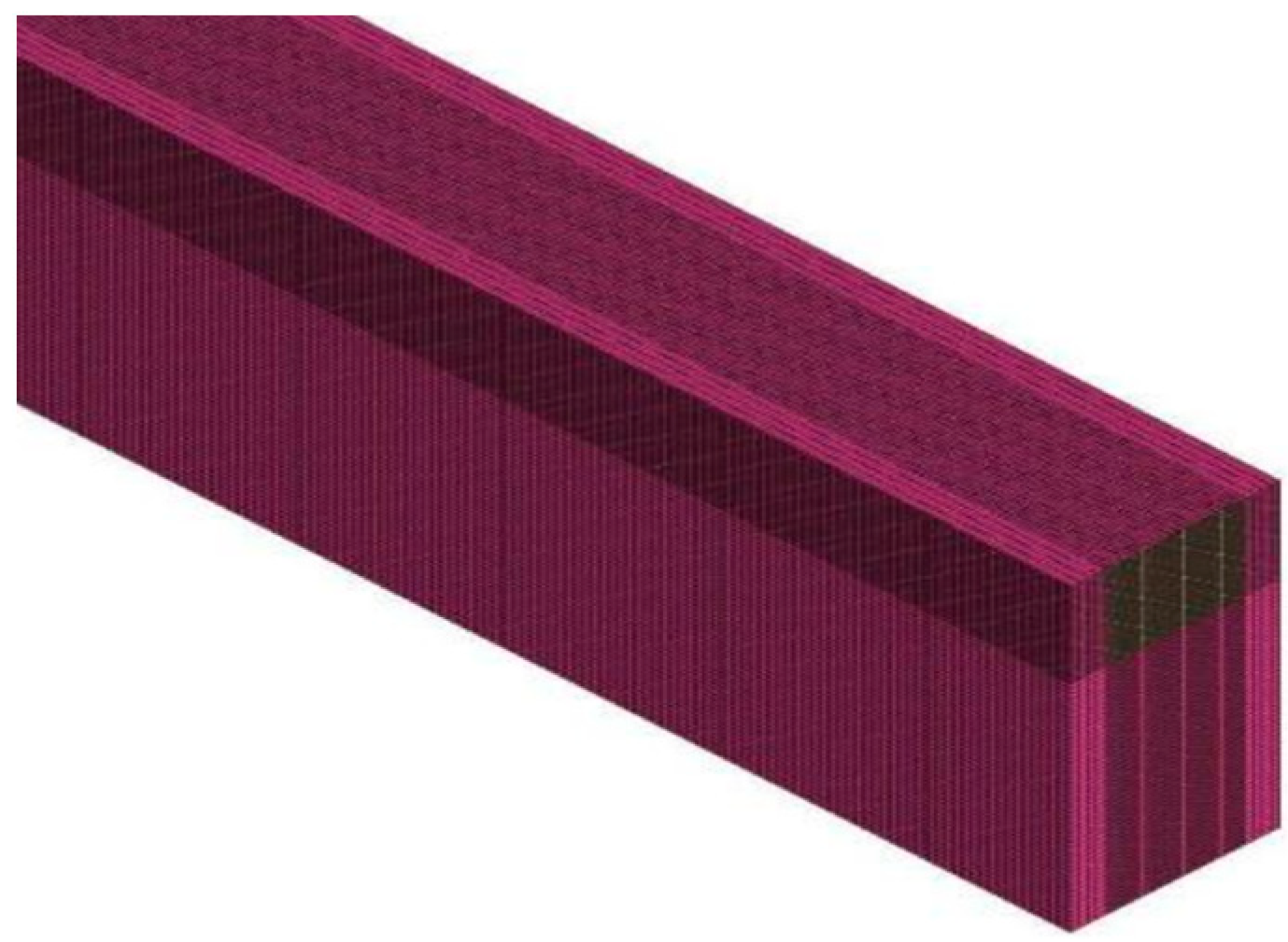

2.4. Data Reduction

The numerical simulation employed a hexahedral-structured meshing approach (Figure 3). Mesh independence verification was conducted to ensure computational accuracy and reduce the processing time. Using standard SMC models as examples, five mesh sizes (945,000, 2,085,000, 3,294,000, 6,809,000 and 9,072,000) were selected. The wall temperatures and corresponding results at Re = 670 are presented in Table 2. The findings demonstrate that employing a 3,294,000 mesh size effectively maintained simulation accuracy while significantly reducing computation time.

Figure 3.

Grid division diagram.

Table 2.

Grid independence study results for the standard straight microchannel (SMC) at Re = 670.

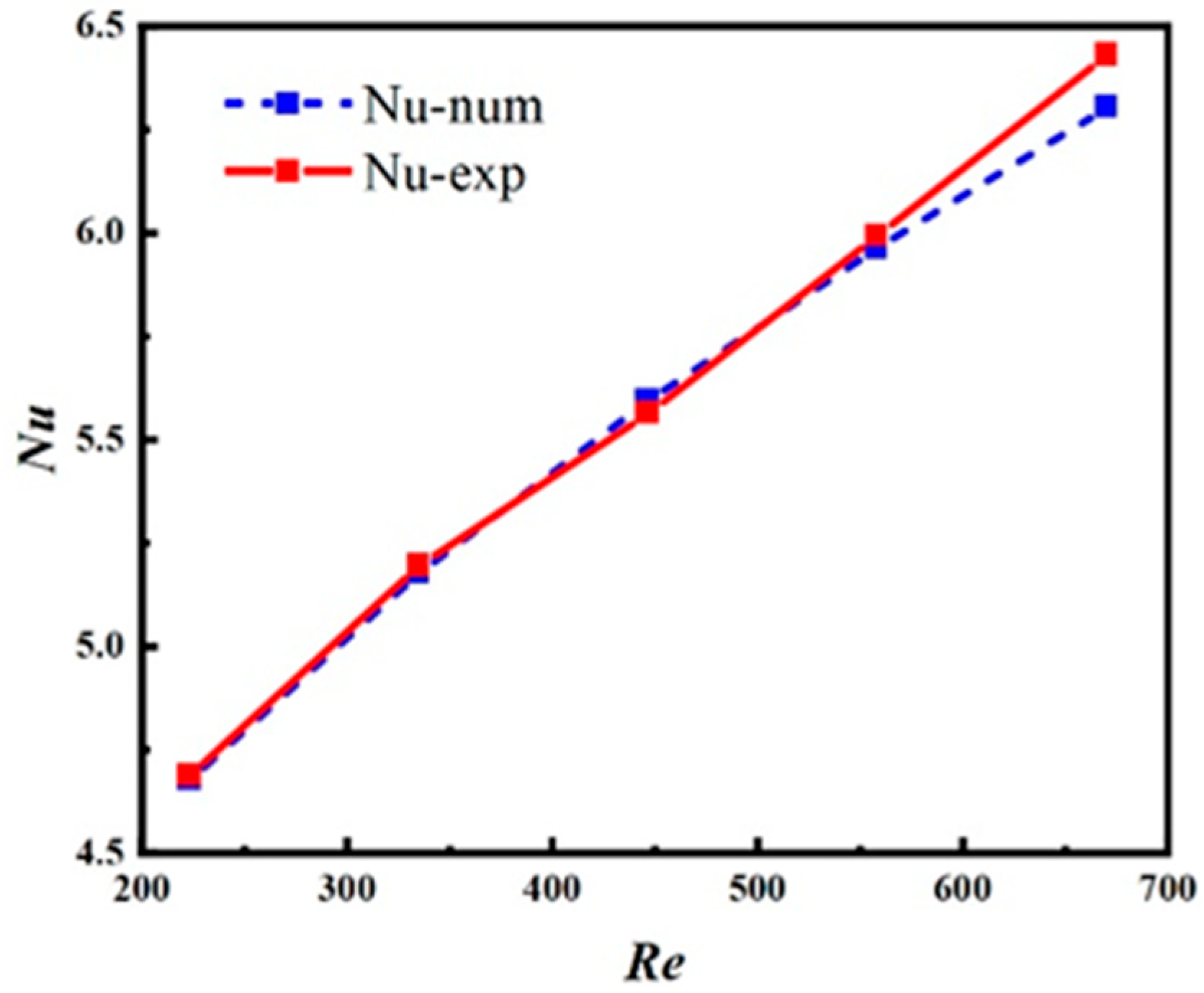

2.5. Model Validation

To ensure the feasibility of numerical simulation methods and the reliability of simulation results, experiments were conducted using straight microchannels (SMCs) with the same geometric dimensions as the computational model. The experimental setup included a microchannel test section, a constant temperature bath, a precision flowmeter, and a data acquisition system. Experimental geometric specifications: Channel length (L): 150 mm; Channel width (Ws): 2 mm; Channel height (Hs): 2 mm; Hydraulic diameter (Dh): 2 mm; Substrate material: Copper (thermal conductivity: 387.6 W/(m·K)); Working fluid: Deionized water. The experiment involved using a calibrated T-type thermocouple with an accuracy of ±0.1 °C to measure the temperature distribution along the channel wall. The flow rate was controlled within the range of 0.1–0.4 m/s at the inlet velocity, corresponding to Reynolds numbers of 223 to 670.

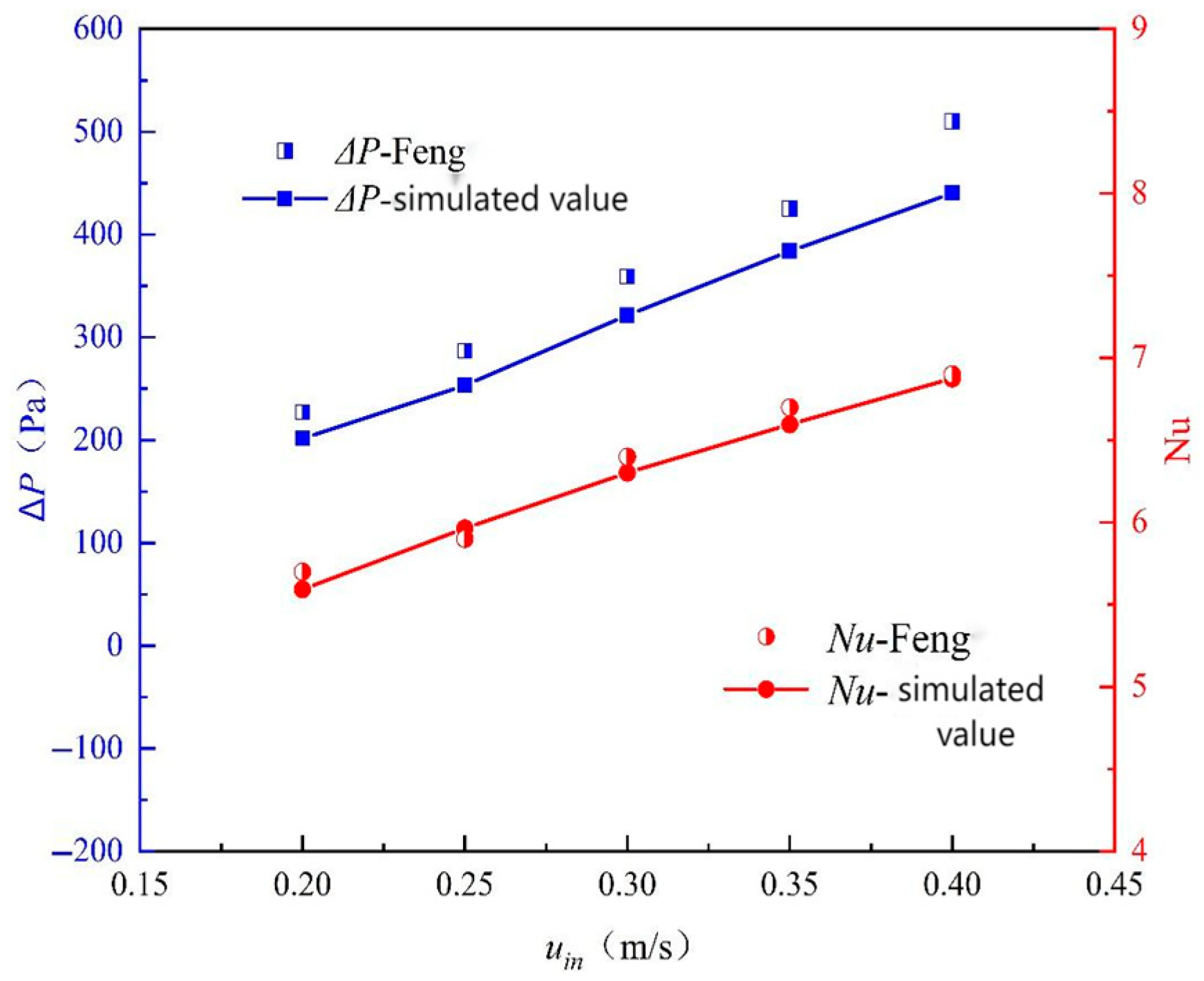

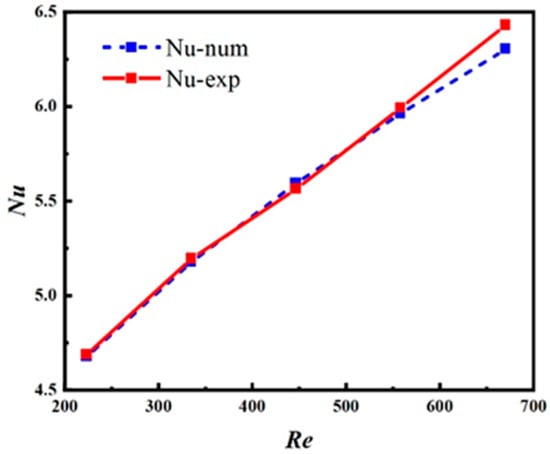

As shown in Figure 4, the Nusselt number shows a significant upward trend when the Reynolds number increases from 223 to 670. The maximum relative error between experimental and numerical Nusselt values is 2.02%, demonstrating excellent consistency. The agreement between numerical simulations and experimental data across the entire Reynolds number range validates the reliability of the fundamental numerical methods for fluid flow and heat transfer analysis.

Figure 4.

Nu variation between experiment and simulation at different Reynolds numbers.

2.6. Numerical Simulation Verification

To further enhance the credibility of our numerical model for predicting both pressure drop and heat transfer, a verification study was conducted by replicating the experimental work of Feng et al. [41]. It is important to clarify the objective of this validation: it serves to confirm the accuracy of our fundamental numerical methodology (including solver settings, discretization schemes, and material property definitions) for simulating conjugate heat transfer in microchannels. This foundation lends confidence when applying the same methodology to the more complex groove-rib geometries central to our study.

The benchmark experiment investigated a single, straight, rectangular microchannel. The key specifications are detailed below to enable a direct comparison:

Channel Geometry: Rectangular, with a square cross-section; Hydraulic Diameter (Dh): 0.8 mm (Channel dimensions: 0.8 mm × 0.8 mm); Channel Length (L): 20 mm (heated section); Inlet Section: A 20 mm long unheated hydrodynamic development section was included prior to the heated test section to ensure a hydrodynamically fully developed flow at the inlet. This is a significant difference from our main study’s model, which uses a simplified uniform velocity inlet; Substrate Material: Silicon; Working Fluid: Deionized water; Boundary Conditions: A constant heat flux of q_w = 100 W/cm2 (1 × 106 W/m2) was applied to the channel base. The inlet temperature was maintained at a constant value.

Our computational model was constructed to match the above geometry and operational conditions as closely as possible. A structured mesh, similar to that used in our main simulations, was employed. The same solver settings (second-order upwind schemes, SIMPLE algorithm) and convergence criteria were applied.

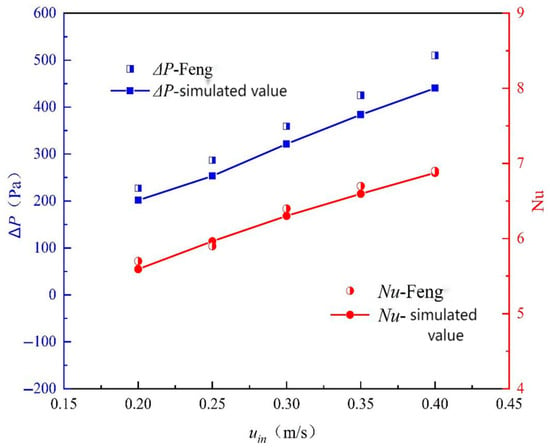

The comparative results for pressure drop (ΔP) and Nusselt number (Nu) across a range of Reynolds numbers are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparative validation of pressure drop and Nu in rectangular microchannels.

As evident from Figure 5, the numerical results for the Nusselt number exhibit excellent agreement with the experimental data, with a maximum relative error of only 1.87%. This high level of consistency validates the accuracy of our heat transfer modeling approach, including the conjugate heat transfer setup and the treatment of temperature-dependent fluid properties.

For the pressure drop, a more considerable discrepancy is observed, with a maximum relative error of 13.69%. This difference is primarily attributed to the fundamental difference in inlet boundary conditions. Our model utilizes a uniform velocity inlet for computational efficiency and consistency with the main study, whereas the experimental setup [41] featured a long inlet tube that resulted in a hydrodynamically developed flow profile at the channel entrance. This development length effect in the experiment leads to a higher measured pressure drop. Other contributing factors may include the neglect of surface roughness in our simulation and inherent experimental uncertainties in pressure measurement.

Despite the discrepancy in absolute pressure drop, the consistent trends and the excellent agreement in heat transfer performance provide substantial confidence in the overall reliability of our numerical methodology. The successful prediction of Nu, which is the primary focus of our heat transfer enhancement study, is particularly significant. This verification confirms that the model is capable of accurately capturing the essential physics of flow and heat transfer, thereby supporting its application to the novel geometries investigated in this work.

Our numerical model was configured to match the geometric and operational parameters of Feng et al.’s [14] experimental setup. The validation focused on two key parameters: pressure drop (ΔP) and Nusselt number (Nu). Comparative results showed a maximum relative error of 13.69% for pressure drop and 1.87% for Nusselt number.

As shown in Figure 5, the pressure drop variation primarily stems from differing inlet conditions. The experimental model incorporates a 20 mm inlet length with surface roughness effects, whereas our numerical model employs a simplified uniform velocity inlet for computational efficiency. The actual flow acceleration in the inlet section increases the experimental pressure drop by approximately 9–12%. Despite this pressure drop discrepancy, the excellent consistency of the Nusselt number (1.87% error) validates the accuracy of the heat transfer modeling approach.

While the validation of the straight microchannel (SMC) confirmed the accuracy of the fundamental numerical methods, it must be acknowledged that extending these validations to complex composite ribbed channel geometries presents limitations. The primary uncertainty stems from the inability to fully capture the unique complex eddy interactions and secondary flows without dedicated experimental data tailored to these specific geometries. Based on mesh sensitivity studies and comparisons with literature data from similar structures [17,42], the estimated uncertainties for Nusselt number and friction coefficient in composite channels are within ±5% and ±8%, respectively. Future work should include dedicated experimental validation for the composite ribbed channel designs investigated in this study.

3. Results

3.1. Flow Characteristics Analysis

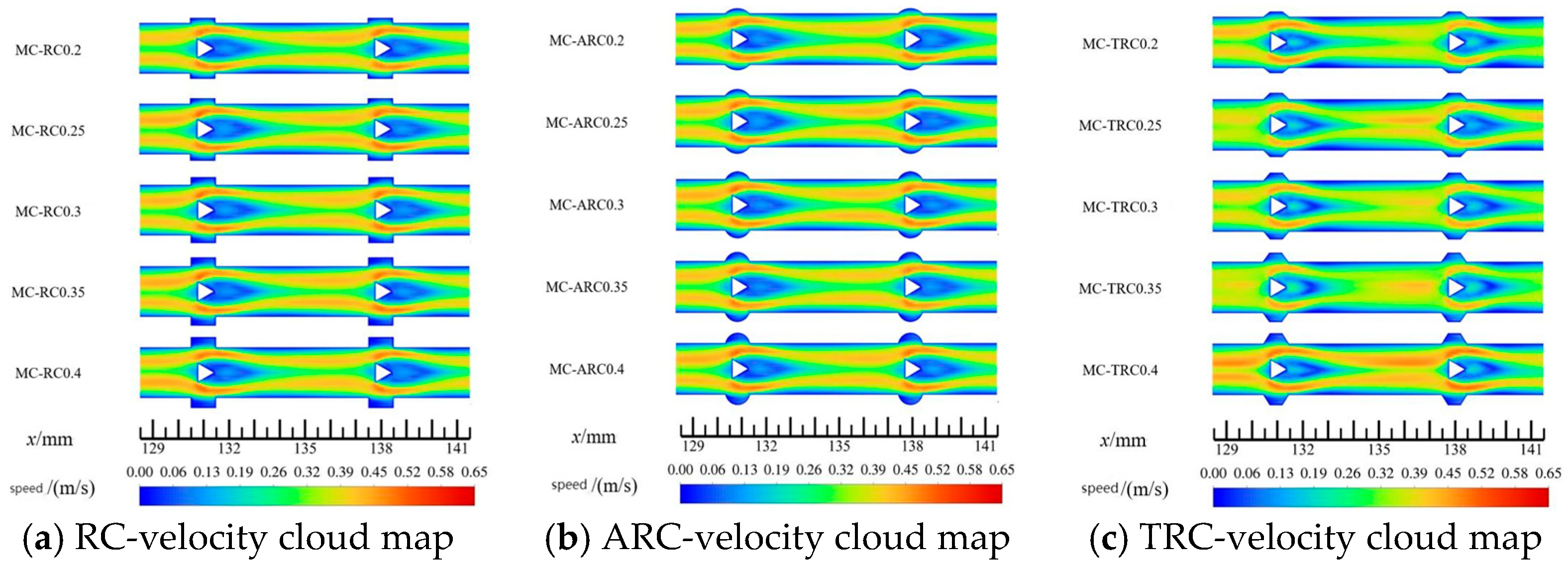

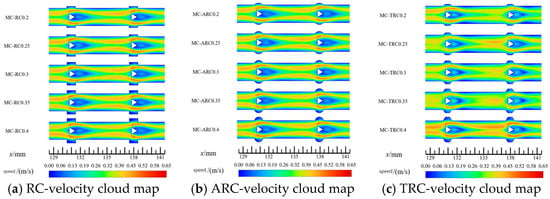

The internal structure of microchannels undergoes structural changes, with the most significant impact on their flow processes. As shown in Figure 6, cross-sectional velocity cloud images are presented for composite microchannels featuring arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal grooves located at z = 5.5 mm and x = 128.5–141.5 mm positions. The velocity cloud in Figure 6 reveals distinct flow mechanisms induced by different groove geometries. The arc-shaped grooves facilitate smooth flow attachment and generate stable recirculating vortices within cavities, enhancing heat transfer at lower Reynolds numbers with minimal pressure loss. In contrast, the trapezoidal grooves with sharp edges induce more pronounced flow separation and stronger turbulent-like vortices, as shown in Figure 7. This results in higher friction coefficients at Re > 550 due to abrupt flow separation at the sharp inlet edges, creating larger recirculation zones and increasing viscous dissipation.

Figure 6.

Velocity cloud of each microchannel.

Figure 7.

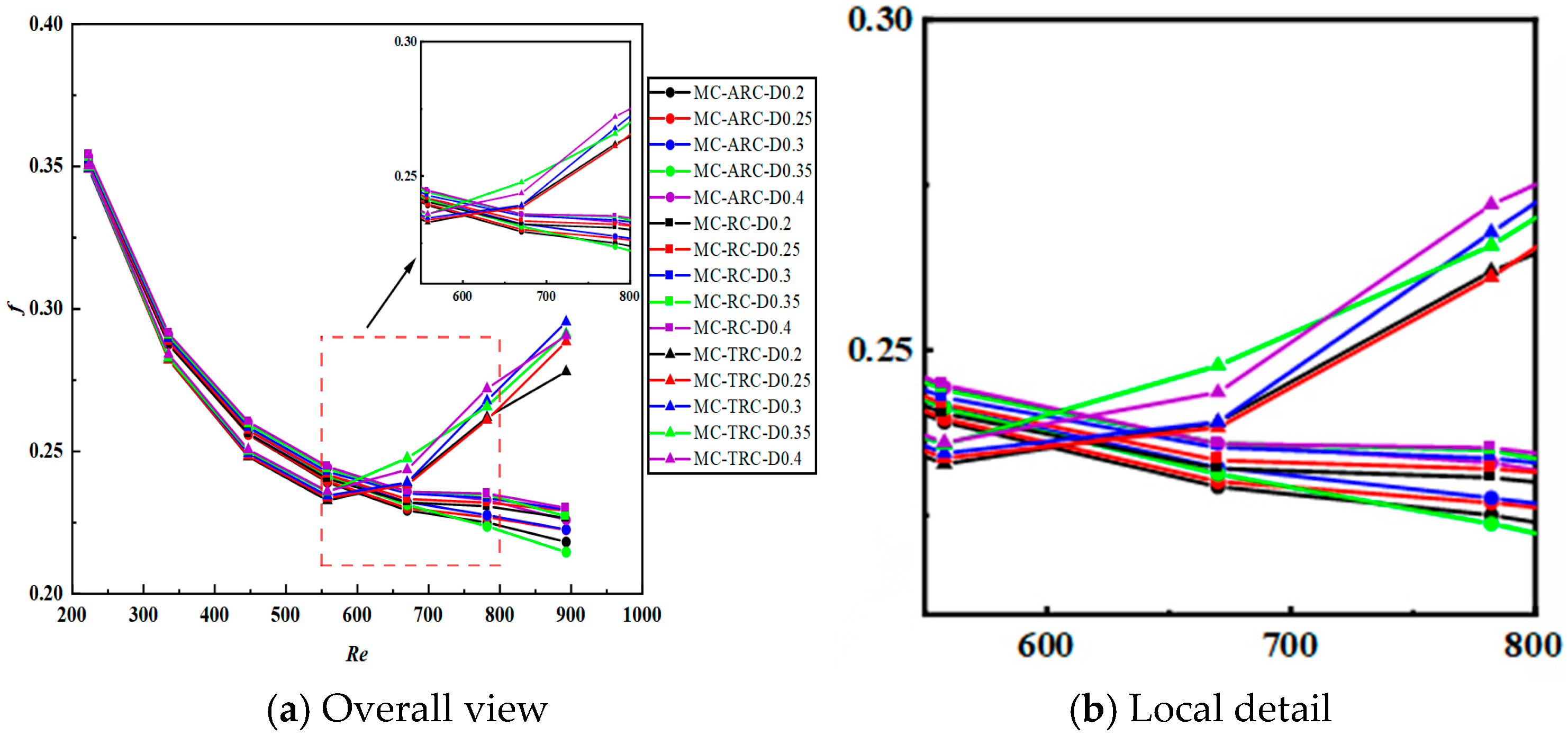

Friction coefficient of each microchannel with a change of Reynolds number.

Compared with SMC microchannels, the incorporation of composite structures created relatively larger stagnation zones near the grooves and triangular prisms. Notably, the fluid velocity was significantly reduced within the groove interiors and behind the rib pillars. As the groove depth increases, the mainstream velocity in the microchannels progressively increases, and the high-speed region expands. This configuration simultaneously flattens the vortices behind the prisms, effectively reducing the flow losses.

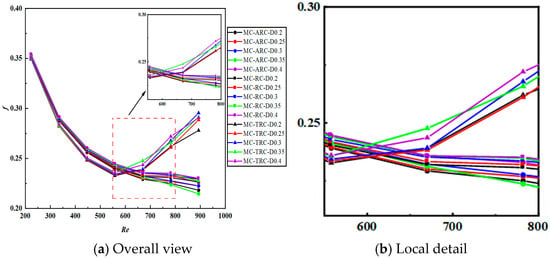

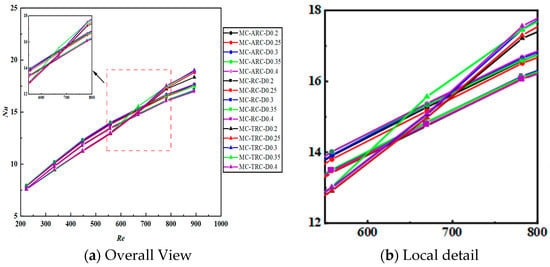

Figure 7 illustrates the variation in friction factor with Reynolds number, with the SMC benchmark for comparative evaluation. Due to the additional surface area and flow disturbances, composite structures typically exhibit higher flow resistance. Comparative analysis: The friction factors for composite configurations were 1.8–3.2 times higher than the SMC baseline; MC-TRC configurations showed the most significant increase in flow resistance at Re > 550; the trapezoidal groove’s sharp edges contributed to increased flow separation and viscous dissipation.

3.2. Quantitative Thermal Performance Analysis

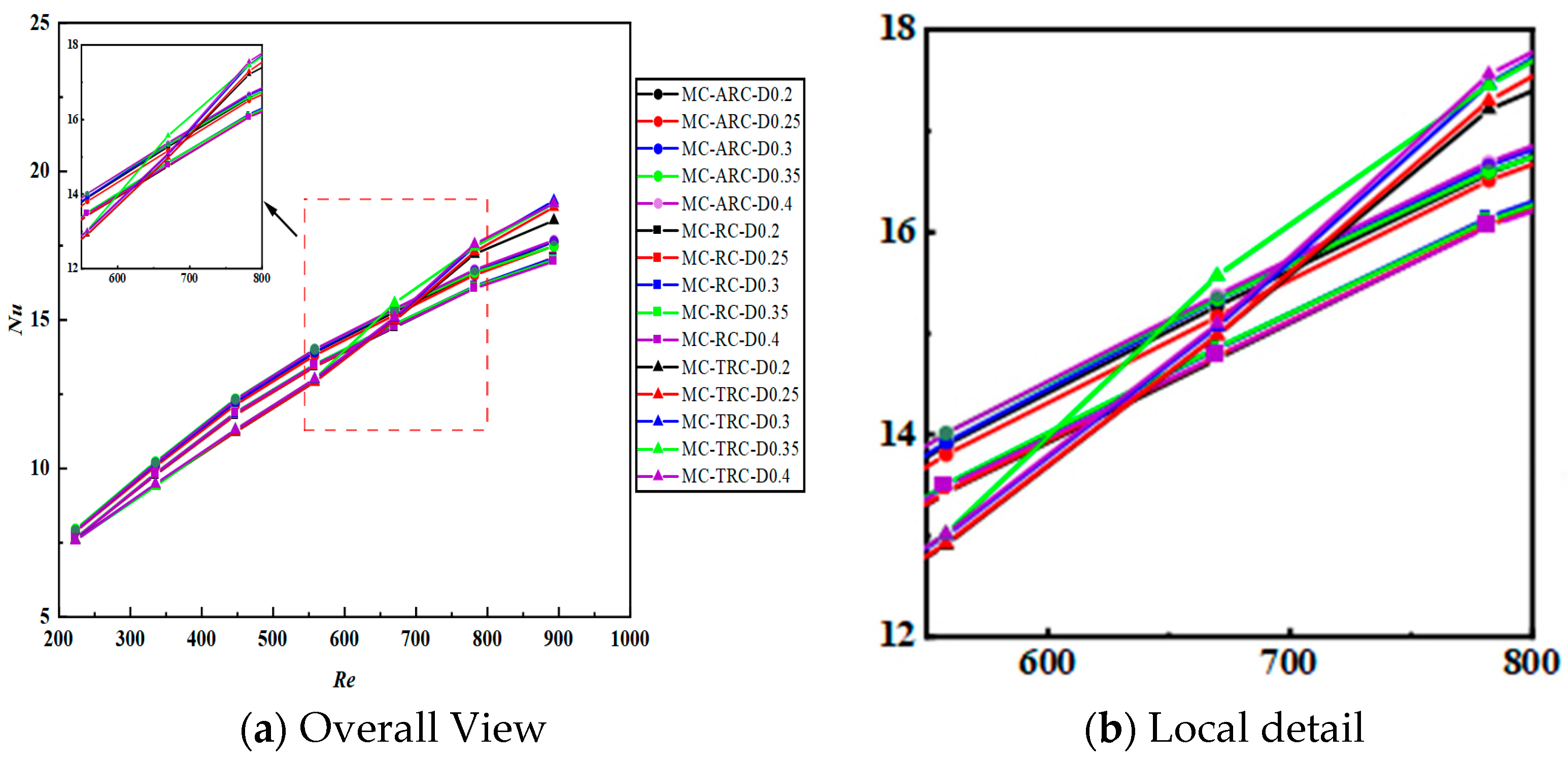

While the differences in Nusselt numbers between various groove configurations appear negligible in numerical values, they exhibit clear and systematic trends that vary with Reynolds number and groove geometry. These trends align closely with the observed flow field structures (Figure 6) and friction coefficient variations (Figure 7). Considering the previously conducted mesh independence validation (error < 0.5%), experimental verification (maximum error 2.02%), and literature data validation (Nu number error 1.87%), we have maintained the numerical uncertainty at a low level. Therefore, we conclude that the observed performance differences are genuine, reflecting inherent physical mechanism variations in different composite structures regarding turbulent flow and enhanced heat transfer.

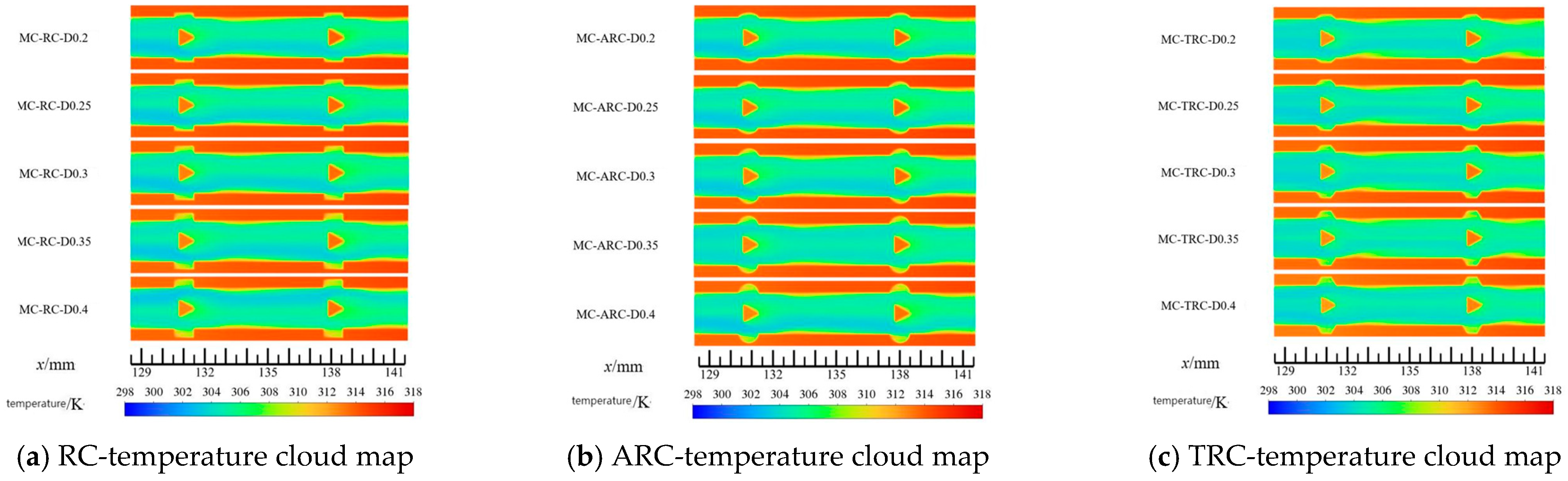

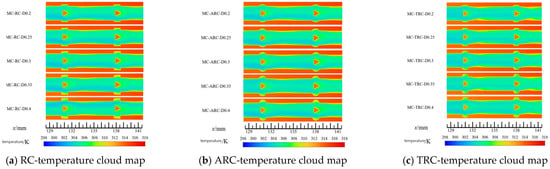

The trapezoidal groove configuration (MC-TRC-D0.35) demonstrated the most uniform temperature distribution with the lowest average wall temperature, indicating superior heat transfer efficiency at high Reynolds numbers. This performance advantage is attributed to the enhanced fluid mixing and boundary layer disruption caused by the sharp geometric features of trapezoidal grooves (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Temperature cloud map of each microchannel.

Figure 9 presents the variation in Nusselt number across all study configurations with respect to Reynolds number, using the baseline straight microchannel (SMC) without grooves as the reference. The results demonstrate a significant improvement in heat transfer performance compared to conventional designs. Key observations: All composite configurations outperformed the SMC baseline across the entire Reynolds number range; The maximum Nu enhancement reached 45.3% for MC-ARC-D0.35 at Re = 223; At high Reynolds numbers (Re > 550), the trapezoidal grooves showed superior performance; The differences between configurations, while numerically small, exhibit consistent trends that exceed the estimated numerical uncertainty of ±5%.

Figure 9.

Nusselt number variation with Reynolds number.

3.3. Comprehensive Performance Analysis

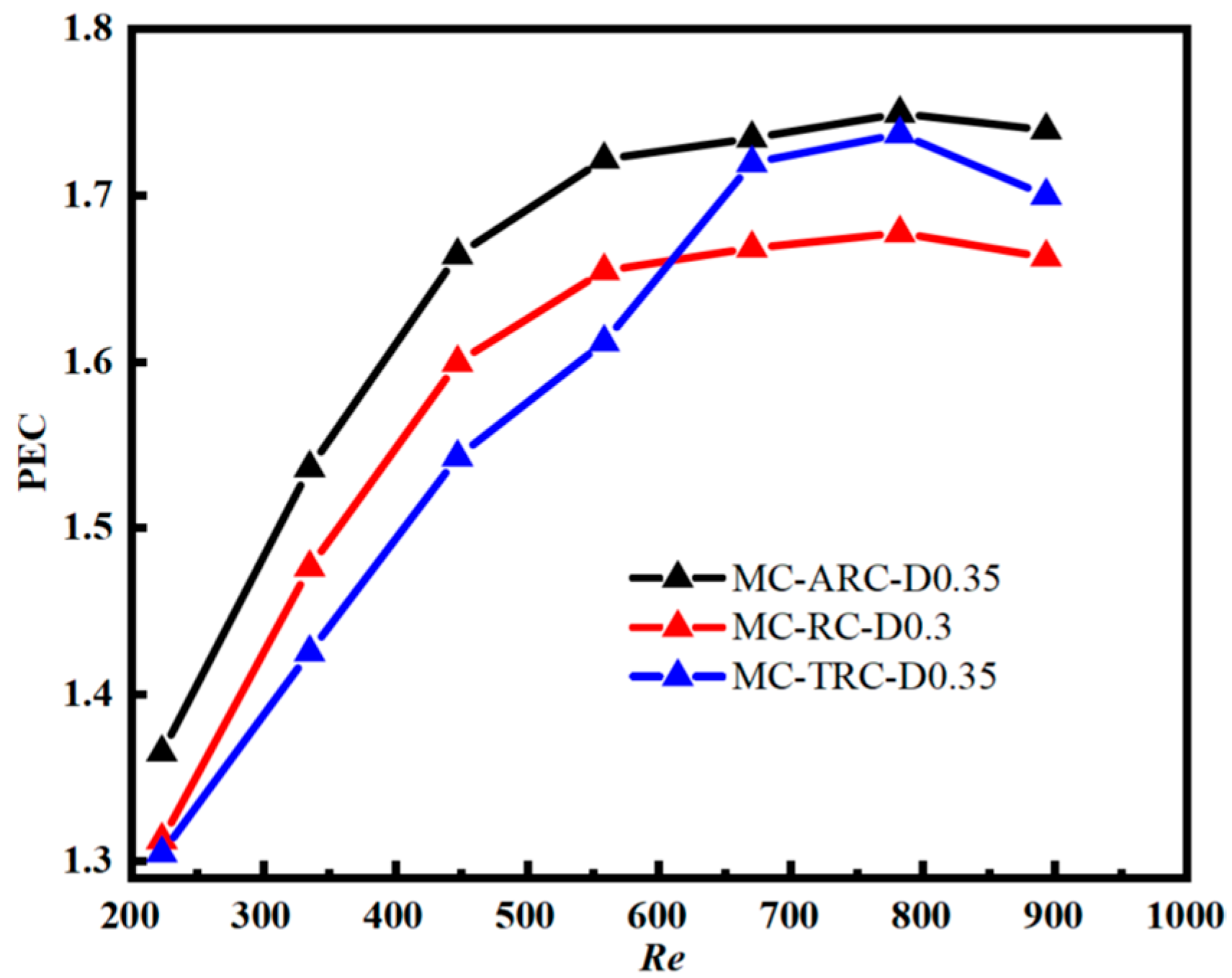

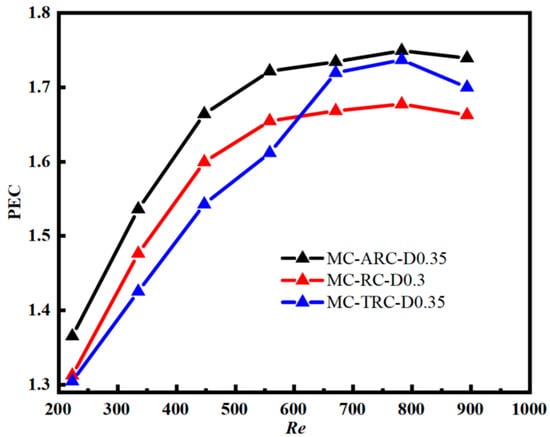

A PEC (Performance Evaluation Criterion) analysis was conducted using the SMC benchmark for explicit comparison, providing a comprehensive assessment of thermohydraulic performance trade-offs. Figure 10 displays the PEC values for all configurations, demonstrating the net benefits of each design relative to conventional microchannels. Benchmark reference performance evaluation: The SMC baseline serves as the reference point (PEC = 1.0); All composite configurations achieved PEC values greater than 1.0, confirming their overall performance superiority; The optimal configuration MC-ARC-D0.35 achieved a maximum PEC of 1.7495, representing a 74.95% overall improvement over the SMC baseline; Performance improvement ranking at Re = 670: MC-ARC-D0.35: 74.95% improvement over SMC; MC-TRC-D0.35: 73.73% improvement over SMC; MC-RC-D0.30: 67.77% improvement over SMC.

Figure 10.

Three kinds of grooves microchannels with maximum PEC variation with Reynolds number.

The PEC values of all composite designs exceeding 1.0 validate the effectiveness of the groove-rib combination strategy, where the arc-shaped grooves provide an optimal balance between heat transfer enhancement and flow resistance penalty.

The results of the Performance Evaluation Criterion (PEC) are presented in Figure 10, which demonstrates that the MC-ARC-D0.35 configuration achieves the highest value (1.335), outperforming the rectangular and trapezoidal structures by 4.3% and 0.7%, respectively. This advantage stems from the optimal balance between Nu enhancement and f reduction, offering a practical solution for high-heat-flux devices like 5G chips. The arc-shaped groove minimizes entropy production by reducing irreversible heat loss, consistent with Li et al.’s [35] research.

The physical mechanism behind the superior performance of arc-shaped grooves at low Reynolds numbers: Under low Reynolds conditions, fluid flow exhibits laminar characteristics with relatively weak inertial forces and dominant viscous forces. The continuous smooth transition of the arc-shaped groove effectively reduces flow separation and lowers wall shear stress. The arc-shaped design allows fluid to adhere smoothly to the wall, forming stable secondary vortex structures that enhance fluid mixing in the wall region, thereby improving heat transfer. Simultaneously, the smooth geometry reduces flow resistance, enabling high heat transfer efficiency even at low flow velocities.

The physical mechanism behind the superior performance of trapezoidal grooves at high Reynolds numbers: As Reynolds number increases, the flow gradually transitions to turbulence, with enhanced inertial forces. The sharp edges and steep geometry of trapezoidal grooves effectively induce flow separation, generating intense vortex shedding and turbulent mixing. These vortices break up and reattach in the downstream groove region, significantly enhancing turbulence intensity and convective heat transfer in the wall region. At high Reynolds numbers, the geometric discontinuity of trapezoidal grooves better excites turbulent pulsations. Although the flow resistance is relatively high, the heat transfer enhancement effect is more pronounced, resulting in superior overall performance [39].

3.4. Entropy Production Analysis

To quantify irreversible losses, the entropy production rate was evaluated based on the calculated velocity and temperature fields [35]. Total entropy production (Sgen) comprises thermal entropy production (Sgen, th) and frictional entropy production (Sgen, fr). For the optimal configuration MC-ARC-D0.35 at Re = 670, its more uniform temperature distribution results in approximately 15% lower thermal entropy production compared to MC-TRC-D0.35, thereby reducing thermal irreversibility. Conversely, MC-ARC-D0.35 exhibits about 8% lower frictional entropy production than MC-TRC-D0.35, consistent with its lower friction coefficient. This analysis confirms that the arc-shaped groove achieves superior thermodynamic performance by effectively minimizing both thermal and frictional irreversibility.

3.5. In-Depth Discussion on Underlying Physical Mechanisms

The observed performance differences in various groove geometries can be attributed to their unique impacts on flow separation, vortex dynamics, and thermal boundary layer development. For the arc-shaped groove (MC-ARC), its smooth profile facilitates gradual flow adhesion and generates stable recirculation vortices within the cavity. This mechanism effectively enhances near-wall fluid mixing, disrupts the thermal boundary layer, and improves heat transfer—particularly at moderate Reynolds numbers where flow inertia is moderate. Meanwhile, the absence of sharp edges minimizes flow separation and associated pressure loss, achieving optimal balance as evidenced by the highest PEC value. In contrast, the trapezoidal groove (MC-TRC) induces intense flow separation due to its sharp inlet edge, leading to the formation of larger, more turbulent-like vortices. While this significantly enhances heat transfer at high Reynolds numbers through boundary layer disruption, it comes at the cost of substantially increased frictional resistance. The rectangular groove (MC-RC) exhibits intermediate behavior. The groove depth further modulates these effects: deeper grooves amplify vortex generation and heat transfer area but also expand the flow recirculation zone, thereby increasing friction coefficients. This explains why the Nusselt number (Nu) increases non-linearly with depth and why the 0.35 mm deep arc-shaped groove achieves optimal performance by enhancing heat transfer while mitigating adverse effects on flow resistance. Entropy production analysis confirms this, demonstrating that MC-ARC-D0.35 achieves lower irreversible losses due to its more uniform temperature distribution and smoother flow field.

3.6. Entropy Generation Analysis and Irreversible Losses

Entropy production analysis provides critical insights into evaluating the overall performance of microchannel heat sinks, revealing thermodynamic irreversibility associated with heat transfer and fluid friction. The total entropy production (Sgen, total) consists of two components: thermal entropy production (Sgen, th) due to heat transfer caused by finite temperature differences, and friction entropy production (Sgen, f) resulting from viscous dissipation. Results demonstrate that the arc-shaped groove (MC-ARC-D0.35) achieves the lowest total entropy production, indicating superior thermodynamic performance. This is attributed to its smooth geometry, which promotes more uniform temperature distribution along the channel walls, thereby reducing thermal irreversibility. Progressive flow attachment and stable vortex formation minimize velocity gradients and shear stress, leading to lower friction entropy production. In contrast, the trapezoidal groove (MC-TRC-D0.35), despite its excellent heat transfer performance, exhibits significantly higher friction entropy production due to intense flow separation and recirculation zones, resulting in substantial viscous dissipation. The Be number (Be), defined as the ratio of thermal entropy production to total entropy production, further reveals the dominant irreversibility mechanism. For all configurations, the Be value remains above 0.8 within the Reynolds number range, indicating that thermal irreversibility dominates over friction irreversibility. This suggests that the primary source of thermodynamic loss lies in the heat transfer process itself rather than fluid friction. However, as the Reynolds number increases, the Be number slightly decreases, reflecting the gradual increase in friction irreversibility contributions due to enhanced fluid mixing and increased velocity gradients. The principle of entropy production minimization demonstrates that optimal designs must strike a balance between thermal irreversibility and frictional irreversibility. The MC-ARC-D0.35 configuration achieves this equilibrium by enhancing heat transfer efficiency while maintaining relatively low pressure drop, thereby attaining the highest PEC value. This finding underscores the critical importance of considering both the first law (energy conservation) and the second law (entropy production) performance metrics in microchannel heat sink designs for high-heat-flux applications.

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Groove Geometry on Flow Structure and Heat Transfer Mechanisms

The three groove shapes (arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal) examined in this study exhibit significant geometric differences that directly determine their flow structure and heat transfer performance. The smooth transition geometry of arc-shaped grooves generates more stable secondary flows and vortex structures. This geometric continuity facilitates steady flow development and reduces energy loss during flow separation and reattachment processes. In contrast, the sharp edges of rectangular grooves lead to intense flow separation and vortex shedding, which, while enhancing heat transfer to some extent, also causes significant local pressure loss. Trapezoidal grooves represent a middle ground, with their inclined sidewalls mitigating the severity of flow separation. From the perspective of vortex formation mechanisms, grooves create periodically arranged recessed structures at the channel bottom. These structures induce two primary vortex types during flow: longitudinal vortices developing along the groove length and transverse vortices perpendicular to the flow direction. Due to their continuous curvature, arc-shaped grooves generate moderate and uniformly distributed vortex intensity that continuously perturbs the near-wall boundary layer without excessive flow resistance. Rectangular grooves, however, produce intense shear layer instability at their edges, resulting in excessive vortex intensity and severe energy dissipation. This is the primary reason for their higher friction coefficients.

4.2. Boundary Layer Disturbance and Heat Transfer Enhancement Mechanisms

The groove structure enhances heat transfer through three primary mechanisms: boundary layer disturbance, flow mixing enhancement, and increased effective heat transfer area. Boundary layer disturbance serves as the core mechanism for heat transfer enhancement. The grooves disrupt the development of the near-wall laminar flow base layer, allowing the thermal boundary layer to be continuously refreshed by fresh fluid. The smooth geometric profile of arc-shaped grooves generates sustained, moderate boundary layer disturbance that effectively breaks down the thermal boundary layer without causing excessive flow energy loss. In contrast, while the intense vortex shedding in rectangular grooves more thoroughly disrupts the boundary layer, this vigorous disturbance is accompanied by significant turbulent energy dissipation, resulting in reduced heat transfer enhancement efficiency (PEC). Flow mixing enhancement is primarily achieved through vortex structures formed within the grooves, which entrain cold fluid from the main flow region to near-wall areas while simultaneously carrying hot fluid away from the wall. This fluid exchange process significantly enhances heat transfer between the wall and the main flow. The inclined sidewalls of trapezoidal grooves create asymmetric vortex structures, further improving fluid mixing efficiency. Increased effective heat transfer area is another critical factor. Grooves add approximately 15–25% to the channel’s bottom surface area (depending on groove depth), with this additional surface directly participating in heat transfer. However, it should be noted that surface area alone cannot fully explain the heat transfer enhancement effect, as insufficient internal flow would result in low utilization efficiency of this additional surface area.

4.3. Physical Mechanisms of Reynolds Number Effects on Performance

The influence of Reynolds number on the performance of composite groove-riblet structures demonstrates the complex coupling relationship between flow state and geometric configuration. In the low Reynolds number range (Re < 1000), the flow remains in transitional or weak turbulent states with weak vortex intensity and limited boundary layer disturbance effects. At this stage, the groove structure primarily serves to increase effective heat transfer area and generate moderate secondary flow. Due to their geometric continuity, arc-shaped grooves maintain stable flow development under low Reynolds numbers, exhibiting relatively consistent performance. As Reynolds number increases (Re > 1000), the flow enters fully developed turbulent state with significantly enhanced vortex intensity and more pronounced boundary layer disturbance effects. At this point, the impact of groove geometry on vortex structure becomes more critical. The sharp edges of rectangular grooves induce intense vortex shedding and flow separation under high-speed flow. Although heat transfer enhancement improves, flow resistance increases dramatically. Arc-shaped grooves demonstrate better performance balance under high-speed flow, as their smooth geometric profiles control vortex intensity within reasonable ranges, ensuring sufficient boundary layer disturbance while avoiding excessive pressure loss. Notably, in the high Reynolds number range (Re > 1500), trapezoidal grooves show significant performance improvement. This is primarily attributed to the inclined sidewalls of trapezoidal grooves generating more complex vortex structures at high flow velocities. These vortices form multi-scale flow mixing within the grooves and near the ribs, thereby enhancing heat transfer efficiency. At the same time, the geometric characteristics of the trapezoidal groove make the flow separation relatively mild and the pressure loss increase relatively controllable.

4.4. Mechanisms of Pressure Loss and Optimization Strategies

The pressure loss in composite groove-rib structures primarily consists of three components: friction loss, shape loss, and secondary flow loss. Friction loss results from shear stress on channel walls, which correlates with wall roughness and flow velocity. While grooves theoretically increase friction loss by expanding the wall surface area, they also alter near-wall flow patterns, potentially reducing local friction coefficients to some extent. Shape loss stems from geometric variations such as abrupt expansions and contractions at groove inlets and outlets, as well as flow separation within grooves. This constitutes the primary source of pressure loss. Rectangular grooves exhibit significant shape loss due to sharp edges causing intense flow separation and reattachment at inlets and outlets. In contrast, the smooth transition geometry of curved grooves substantially reduces such shape loss. Secondary flow loss refers to energy dissipation caused by vortex generation and secondary flow induced by grooves. Although these vortices enhance heat transfer, their formation and maintenance require energy consumption. Curved grooves produce moderately intense and uniformly distributed vortices with relatively lower energy dissipation, whereas rectangular grooves generate strong vortex shedding leading to greater energy loss. From an optimization perspective, ideal groove geometries should generate sufficiently intense vortices to disturb the boundary layer while minimizing both shape loss and secondary flow loss. Curved grooves excel in this regard, as their smooth geometric profiles achieve optimal balance between heat transfer enhancement and pressure loss reduction.

4.5. Comparison with Existing Research and Innovations

The innovation of this study lies in systematically evaluating the performance of three distinct geometric groove configurations in composite groove-fin structures, with in-depth analysis of their flow and heat transfer mechanisms. Unlike traditional single-enhancement structures (e.g., fins or grooves alone), the composite structure achieves significantly enhanced heat transfer through the synergistic interaction of fins and grooves. Compared to prior studies, this research not only provides detailed performance data but, more importantly, reveals the profound impact of groove geometry on flow structure and heat transfer mechanisms, offering theoretical foundations and design guidance for optimizing microchannel heat exchangers.

5. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluates the thermo-hydraulic performance of microchannel heat sinks with composite groove-riblet structures. Three groove geometries (arc-shaped, rectangular, and trapezoidal) were investigated across a depth range of 0.2–0.35 mm, with particular focus on flow resistance and heat transfer characteristics in the turbulent zone (Re = 670–2010). Numerical simulations demonstrate that all composite groove-riblet configurations significantly enhance heat transfer efficiency while increasing flow resistance. The Performance Evaluation Criterion (PEC) indicates that arc-shaped grooves exhibit optimal performance across all Reynolds numbers, with PEC values ranging from 1.33 to 1.75. The arc-shaped groove configuration (MC-ARC-D0.35) was identified as the most effective, primarily due to its smooth geometric profile that generates more stable secondary flows and vortex structures. Compared to rectangular and trapezoidal grooves, arc-shaped grooves demonstrate superior control over flow separation and vortex shedding, thereby achieving enhanced heat transfer with relatively smaller flow resistance increases. Furthermore, the 0.35 mm depth of the arc-shaped groove achieves an optimal balance between heat transfer enhancement and flow resistance. These findings provide critical guidance for the engineering design and optimization of microchannel heat sinks. The arc-shaped groove-riblet composite structure shows promising applications in electronic device cooling, particularly in scenarios requiring high thermal performance with acceptable pressure drop tolerance. However, designers must balance heat transfer enhancement with system energy consumption, selecting optimal groove depth and Reynolds number ranges based on specific application requirements. This study has the following limitations: First, the numerical simulation employed simplified uniform velocity inlet boundary conditions, which may differ from actual inlet flow conditions. Second, the model did not account for the impact of surface roughness and manufacturing tolerances on performance. Third, the research only examined turbulent zones, excluding laminar and transitional flow regions. Finally, all simulations assumed steady-state, incompressible flow conditions while neglecting radiative heat transfer effects. Based on the findings and limitations of this study, future research directions should include the following: conducting experimental validation studies to verify the accuracy of numerical simulation results; expanding the scope to laminar and transitional flow regions for comprehensive evaluation of composite structures under different flow conditions; investigating the effects of different working fluids (e.g., nanofluids) on performance; performing multi-objective optimization studies considering heat transfer performance, flow resistance, and manufacturing costs; and studying the impact of manufacturing processes on groove geometric precision and surface quality to provide more reliable guidance for practical engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.S. and J.Y.; methodology, T.S.; software, Z.S.; validation, T.S., M.B. and J.Z.; formal analysis, Z.S.; investigation, T.S., M.B. and J.Z.; resources, J.Y.; data curation, Z.S. and J.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, J.Y.; visualization, J.Y.; supervision, J.Y.; project administration, J.Y.; funding acquisition, J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the following project: Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology Project “Research and Application of Coupled Superconducting Materials for Medium and Deep Geothermal Energy” (20240304150SF).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions protecting participant confidentiality and ethical approval conditions stipulated by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of JilinJianzhu University, which prohibit unrestricted sharing of identifiable human-subject data. Further inquiries regarding data access can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tuckerman, D.; Pease, R. High-performance heat sinking for VLSI. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 1981, 2, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Thermal management and temperature uniformity enhancement of electronic devices by micro heat sinks: A review. Energy 2021, 216, 119223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefflinger, B. IRDS—International Roadmap for Devices and Systems, Rebooting Computing, S3S; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, Z.; Ali, H.M. Air cooled heat sink geometries subjected to forced flow: A critical review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 130, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadique, H.; Murtaza, Q.; Samsher. Heat transfer augmentation in microchannel heat sink using secondary flows: A review. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 194, 123063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yin, Z.; Jin, Q.; Shi, L. Experimental study on heat transfer characteristics of triangular and trapezoidal groove microchannels. China Fluid Mach. 2023, 51, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzweg, U.H.; Zhao, L.D. Heat transfer by high-frequency oscillations: Anew hydrodynamic technique for achieving large effective thermal conductivities. Phys. Fluids 1984, 32, 2624–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, S.; Cao, Y. Thermohydraulic performance of the microchannel heat sinks with three types of double-layered staggered grooves. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 201, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Ding, C.Y. Study on the thermal behavior and cooling performance of a nanofluid—Cooled microchannel heat sink. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2011, 50, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqiuddin, N.H.; Saw, L.H.; Yew, M.C.; Yusof, F.; Ng, T.C.; Yew, M.K. Overview of micro-channel design for high heat flux application. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Sharma, V.; Sanyal, D.; Das, P. A conjugate heat transfer analysis of performance for rectangular microchannel with trapezoidal cavities and ribs. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2019, 138, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshanpour, K.; Kamali, R.; Eslami, M. Effect of rib shape and fillet radius on thermal hydrodynamic performance of microchannel heat sinks: A CFD study. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 119, 104928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Li, J.; Gong, L. Effect of TSV Structure Characteristics on Thermal Performance of Microchannel Heat Sinks. China J. Eng. Thermophys. 2024, 45, 3111–3121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Feng, Z.F.; Li, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F. Numerical investigation on hydraulic and thermal performances of a mini-channel heat sink with twisted ribs. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 179, 107718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Xie, D. Study on Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Interlaced Internal Rib Microchannels. China Therm. Power Eng. 2022, 37, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Yao, H.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, L. Numerical simulation of convective heat transfer in bionic fish-scale microchannels and optimization of structural parameters. China Therm. Power Eng. 2024, 39, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Deng, D.X.; Zhong, N.B.; Zheng, G. Thermal and flow performance in microchannel heat sink with open-ring pin fins. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 200, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, M.E.; Cadirci, S. Artificial neural network model and multi-objective optimization of microchannel heat sinks with diamond-shaped pin fins. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 194, 123015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.E.; Ahmed, M.I. Optimum thermal design of triangular, trapezoidal and rectangular grooved microchannel heat sinks. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 66, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.Q.; Wang, H.Q.; Zhong, Y.J.; Hu, M.; Zhou, X.; Dong, G.; Huang, P. Experimental investigation of the heat transfer performance of microchannel heat exchangers with fan-shaped cavities. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 134, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Huang, J.; Xu, Y. Numerical analysis of heat transfer and flow performance in concave microchannels. China Semicond. Optoelectron. 2020, 41, 232–236+241. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, T.B.; Xu, D.M. Pressure drop and heat transfer performance of microchannel heat exchangers with elliptical concave cavities. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 218, 119351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Cao, Z.Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, L.; Sun, T. Investigation of fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics in a microchannel heat sink with double-layered staggered cavities. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 187, 122535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F.; Huang, S.; Li, Z. Design of a mini-channel heat sink for high-heat-flux electronic devices. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 216, 119053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Li, Z.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F. Effects of combination modes of different cavities and ribs on performance in mini-channels—A comprehensive study. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 142, 106633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Xia, G.D.; Wang, H.S. Laminar flow and heat transfer characteristics of interrupted microchannel heat sink with ribs in the transverse microchambers. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2016, 110, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidmofid, M.; Bahiraei, M. Thermohydraulic assessment of a novel hybrid nanofluid containing cobalt oxide-decorated reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite in a microchannel heat sink with sinusoidal cavities and rectangular ribs. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 131, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.Z.; Du, J.Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Varbanov, P.S.; Klemeš, J.J. Investigation on thermal performance of nanofluids in a microchannel with fan-shaped cavities and oval pin fins. Energy 2022, 260, 125000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.T.; Zhai, Y.L.; Li, Z.H.; Shen, X.; Wang, H. Thermal performance analysis of multi-objective optimized microchannels with triangular cavity and rib based on field synergy principle. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 25, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Su, R.; Xia, H.; Zeng, J.; Chen, J. Numerical simulation study of thermal and hydraulic characteristics of laminar flow in microchannel heat sink with water droplet cavities and different rib columns. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 172, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.W.; Fu, L.T.; Guan, J.; Shen, C.; Tang, S. Investigation on the heat transfer and energy-saving performance of microchannel with cavities and extended surface. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 189, 122712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajalingam, A.; Chakraborty, S. Effect of micro-structures in a microchannel heat sink—A comprehensive study. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 154, 119617. [Google Scholar]

- Rajalingam, A.; Chakraborty, S. Effect of shape and arrangement of micro-structures in a microchannel heat sink on the thermo-hydraulic performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 190, 116755. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, L.; Xia, G.D.; Wang, H.S. Parametric study on thermal and hydraulic characteristics of laminar flow in microchannel heat sink with fan-shaped ribs on sidewalls—Part 1: Heat transfer. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 97, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Wang, Z.P.; Yang, J.L.; Liu, H. Thermal and hydraulic characteristics of microchannel heat sinks with cavities and fins based on field synergy and thermodynamic analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 175, 115348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; E, J.; Tu, Y.; Luo, W. Biomimetic microchannel structures and their topological optimization: A review. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2025, 163, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Wang, L.; Bai, X. Thermohydraulic performance of microchannel heat sinks with triangular ribs on sidewalls—Part 1: Local fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lazarus, G.A.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Y. Pathways to decarbonizing buildings: Harnessing energy efficiency and sustainable technologies. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 66, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Kang, D.; Fu, L.; Lan, M.; Tang, S.; Yao, S.; Wang, L.; Lei, Y. Investigation of flow and heat transfer characteristics in microchannel with high-frequency ultrasound. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 59, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tao, W. Heat Transfer, 4th ed.; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Guo, F. Effects of regular triangular prisms on thermal and hydraulic characteristics in a minichannel heat sink. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 188, 122583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.T.; Xia, G.D.; Li, Y.F.; Ma, D.; Cai, B. Heat transfer and fluid flow characteristics of combined microchannel with cone-shaped micro pin fins. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 92, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.