Abstract

Investment casting of aluminum alloys is widely used in the aeronautical and automotive sectors for manufacturing complex components. However, conventional alloys lack sufficient mechanical strength and high-temperature resistance, prompting the need for enhanced materials. This study investigated the addition of submicron TiC particles, introduced via stir casting process, to an AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy for investment casting. Chemical analysis confirmed the incorporation of up to 0.1 wt.% TiC, but no significant improvement in tensile properties was observed. High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy (HRSEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) revealed a complex microstructure with few TiC particles and needle-shaped intermetallic phases containing titanium, iron, silicon, or aluminum. The high mold temperature (700 °C) and slow solidification rate likely caused partial TiC dissolution and intermetallic precipitation, which may have offset strengthening mechanisms like the Hall–Petch effect. Notably, the partial dissolution of TiC particles in investment casting has not been previously reported in similar alloys. These findings highlight the challenges of using particle-reinforced alloys in this process and emphasize the need for further research into process–microstructure relationships.

1. Introduction

Most aluminum casting components for transport sector applications are produced using the High-Pressure Die Casting (HPDC) process. HPDC is a highly automated process designed for mass production, characterized by short cycle times. However, components tend to exhibit a relatively high level of porosity compared to those produced using other casting processes. This is mainly attributed to the turbulent flow of the liquid metal during the injection step and the decomposition of lubricants employed to avoid the soldering of the casting to the die. Although the introduction of vacuum-assisted injection processes has improved the properties and structural integrity of HPDC components, new approaches are necessary to meet the increasingly demanding requirements of the transport industry. As a result, new manufacturing processes such as low-pressure diecasting or advanced investment casting have been successfully implemented. Additionally, the aluminum casting industry has adopted strategies based on the development and application of new high-performance alloys incorporating alloying elements such as scandium, lithium, or zirconium, as well as ceramic particles like alumina, carbides, or borides [1,2,3,4].

Investment casting components are usually addressed to two main markets. On one hand, there is the production of small-sized aluminum or steel parts with low geometrical complexity for the automotive sector. On the other hand, this process is also used to manufacture larger components with elevated dimensional and mechanical requirements, mostly produced in Ni superalloys, predominantly manufactured for the aeronautical sector. These components offer high added value but face a significant limitation: the mechanical properties achievable through investment casting are inherently constrained. Investment casting process relies on ceramic shell molds that may be heated up to high temperatures, enabling the production of complex components with very thin walls, high surface quality, and excellent dimensional accuracy. However, the ceramic nature of the molds results in slow solidification of the molten metal, which can result in coarse grain structure and, consequently, reduced mechanical properties. Over the past decades various strategies have been developed to overcome these drawbacks. These strategies include the development of rapid solidification technologies, the incorporation of metallic chillers, changes in the composition of ceramic layers, directional solidification to produce single-crystal components, hot isostatic pressing (HIP) processes, as well as the development of advanced alloys and ceramic-reinforced metal matrix composites specifically designed for investment casting [5,6].

The incorporation of submicron-sized ceramic particles into liquid metal has been successfully applied in other aluminum casting processes, presenting a promising opportunity to enhance the mechanical performance of investment cast components. Due to their small size, these particles can provide a unique combination of strengthening mechanisms to the alloys. Their interaction with dislocations has proven to be particularly effective in improving material strength. The primary strengthening mechanisms activated by the presence of submicron-sized particles include the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch and the Orowan effect, especially when the particle diameter is below 50 nm. These particles can effectively pin down dislocations, leading to the formation of Orowan loops under external load. Additionally, Hall–Petch strengthening, resulting from the grain size reduction, can significantly and positively impact the mechanical properties of the alloys, as grain boundaries directly impede dislocation movement [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

The present work aims to assess the efficacy of sub-micron TiC particle reinforcement in improving the mechanical performance of an AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy processed by investment casting. Specifically, TiC concentrations up to 0.1 wt.% were introduced into the melt. To evaluate the influence of TiC particle incorporation on the AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy, a detailed microstructural analysis was carried out to identify the distribution, morphology, and any dissolution of TiC particles. In addition, tensile tests were conducted to evaluate the influence of the particles in the mechanical properties of the material.

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Materials

In this work, a secondary AlSi7Mg0.3 aluminum alloy with the chemical composition shown in Table 1 was used as base material. The material was supplied by Redisa (Madrid, Spain). The use of AlSi7Mg0.3 aluminum alloy in investment casting is justified by its excellent mechanical properties, which make it particularly suitable to produce high-quality, complex components with great dimensional accuracy and surface finish, which are essential characteristics for applications in the aerospace and automotive industries. The AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy was upgraded with the incorporation of submicron-sized TiC particles, aiming to further improve its performance, combining advanced casting techniques to achieve components with enhanced strength, precision, and reliability.

Table 1.

AlSi7Mg0.3 chemical composition in wt.%.

The TiC powder used in this study, with an average particle size of 373 nm, was produced and supplied by Marion Technologies S.A. (Verniolle, France). The TiC particles were mixed with pure aluminum using a ball milling process. The aluminum powder, supplied by Pometon España S.A. (Ripollet, Spain), had a purity of 99.5% and an average particle size of less than 200 µm. Throughout the research, this material was utilized to investigate the effect of TiC particles on the properties of the alloy. Additionally, an Al-Sr modifier (~0.1 wt.%) and an AlTi5B1 grain refiner (~0.15 wt.%) were introduced immediately before the casting step, following the standard procedures and recommended dosages.

2.2. Samples Fabrication Procedure

The production of AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy samples reinforced with 0.1 wt.% TiC via investment casting was carried out in three successive stages. This methodology had been previously optimized and described in detail in another work [14].

In the first stage, a high-energy ball milling process was employed to obtain a homogeneous mixture composed of 70 g of pure aluminum and 15 g of TiC powder. This step was critical for disaggregating TiC agglomerates, enhancing their wettability by the molten alloy, and avoiding the direct handling of submicron powders in subsequent stages. The milling was performed using a Retsch (Haan, Germany) PM400 planetary ball mill under an argon atmosphere and without the use of surfactants. Sealed steel jars with a nominal volume of 500 mL were loaded with 70–80 g of the powder mixture. Chromium steel balls with a diameter of 12 mm were used as milling media, with a ball-to-powder weight ratio ranging from 7:1 to 10:1. The rotation speed of the milling platform was set at 300 rpm, and the jars were air-cooled throughout the milling operation to prevent overheating.

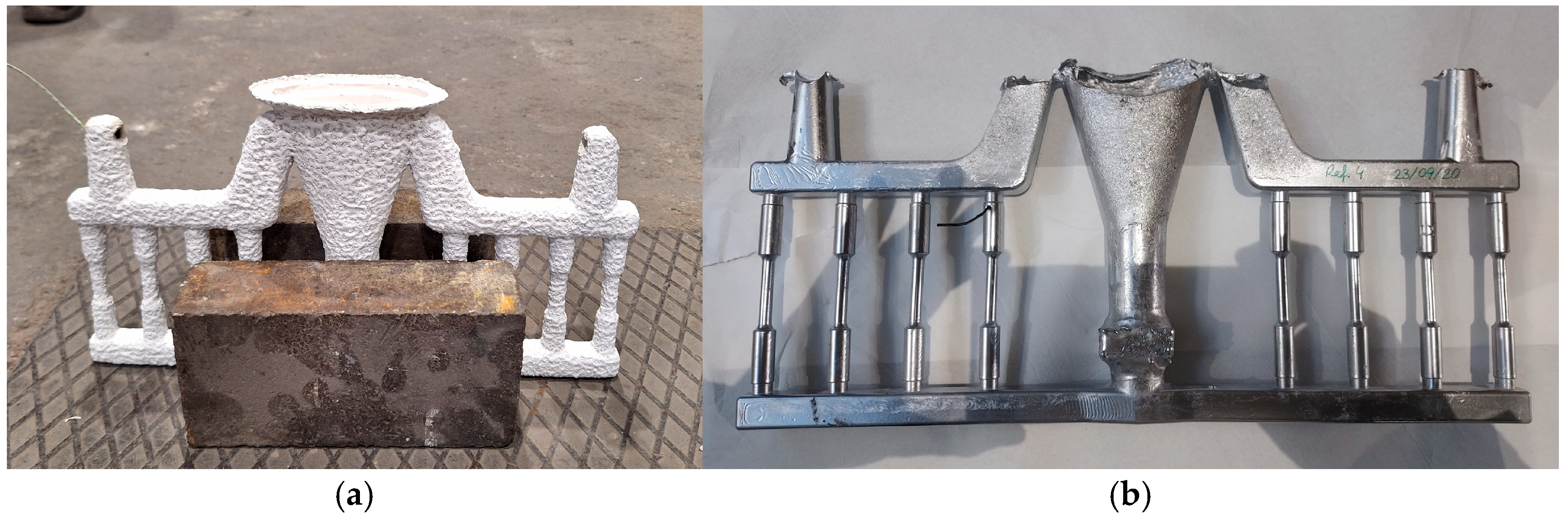

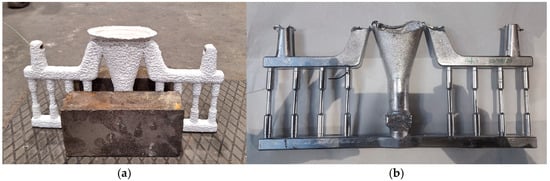

In the second stage, the resulting powder mixture was pelletized in a hydraulic press applying a load of 2–7 t. These pellets were introduced into the melt by semi-solid stir casting process. This process consists of heating the alloy until it is completely molten, then slightly reducing the temperature to reach a semi-solid state and introducing a stirrer. The stirrer creates a vortex into which the pellets are manually added. The stirring at 360 rpm was maintained for 15 min. Ten minutes after the powder addition, the stirring was stopped, and the stirrer was removed. Thanks to the stirring in this semi-solid state, high shear forces are generated that are known to break up particle clusters and promote better wetting between the aluminum matrix and the reinforcing particles [10,15]. In each experiment, 3 kg of AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy were melted in a silicon carbide crucible placed in an induction furnace. A K-type thermocouple was immersed into the melt to monitor its temperature, which was maintained between 650 and 670 °C during the stirring process. The melt was then reheated to 730 °C, the modifier and the refiner were added, and the molten material was poured into a preheated ceramic shell at 650 °C (Figure 1a). After solidification, the casting was demolded. The cast part comprised eight tensile test specimens (Figure 1b), which were used for mechanical property analysis. After the mechanical tests, the broken pieces were retained and the material from the specimen heads was used for the microstructural investigations.

Figure 1.

(a) Ceramic mold ready to be cast and (b) aluminum part after being demolded. The incorporation yield of the TiC particles was evaluated by comparing the titanium content in the final reinforced samples with that of the original as-cast AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy. Based on this comparison, the final TiC content was estimated to be approximately 0.1 wt.% in the solidified material.

2.3. Material Characterization

The samples were characterized from both mechanical and microstructural perspectives. The microstructural analysis was conducted to investigate the influence of particles on phase precipitation, their interaction with other elements and phases, and to examine any possible chemical reaction. This analysis involved advanced techniques such as optical microscopy (OM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and X-ray diffraction (XRD) to provide a thorough understanding of the microstructural evolution. Furthermore, tensile tests were systematically performed to determine the mechanical properties of the reinforced alloy, specifically the tensile strength and elongation at break. The tensile testing was carried out in accordance with ASTM standards, ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of the results. The data obtained from these tests were analyzed using statistical methods to quantify the improvement in mechanical resistance and ductility imparted by the incorporation of the particles.

The obtained samples were analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), specifically a FEI (Hilsboro, OR, USA) TECNAI G2 FEG-type microscope. This equipment, equipped with an X-ray Energy Dispersion Analyzer (EDX), allows for the identification of the different phases that have precipitated. Furthermore, thin foils for TEM observations were prepared with an electro polishing Struers (Ballerup, Denmark) TenuPol-5 electrode equipment, using nitric acid (1/3) and methanol (2/3) electrolyte at a temperature of 250 K. Before the TEM observation, samples were also examined using SEM.

Tensile tests were performed in an Instron (Norwood, MA, USA) 5500R machine following the ASTM E8/E8M-2024 standard [16]. Prior to these tests samples were thermally heated following the standard T6 treatment. The average mechanical properties of five specimens, along with standard deviation, were calculated for the reinforced material and compared with those of the unreinforced specimens of the same alloy.

Additionally, to determine the precise chemical composition of the alloy, a Spectro (Kleve, Germany) SPECTROMAXx Metal Analyzer was employed. This equipment is widely used for material analysis in foundries and was primarily used to monitor the titanium (Ti) content. This served as an indirect method to verify the incorporation of titanium carbide (TiC) particles into the Al-SI7Mg0.3 alloy and to calculate the process yield. (see Table 2).

Table 2.

AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC chemical composition in wt.%.

Eventually, grain sizes of samples of both the reference alloy and the reinforced material were measured following the ISO 643:2024 standard [17].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition

Chemical composition of the reinforced AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC was analyzed (see Table 2 below) and compared to the reference alloy (see Table 1).

The table shows that Ti was incorporated into the alloy in small amounts, approximately 0.11 wt.%. Considering that up to 0.5 wt.% of particles had been added into the melt, it can be concluded that the yield of the ball milling and stir casting process selected is around 20%.

3.2. Microstructural Characterization

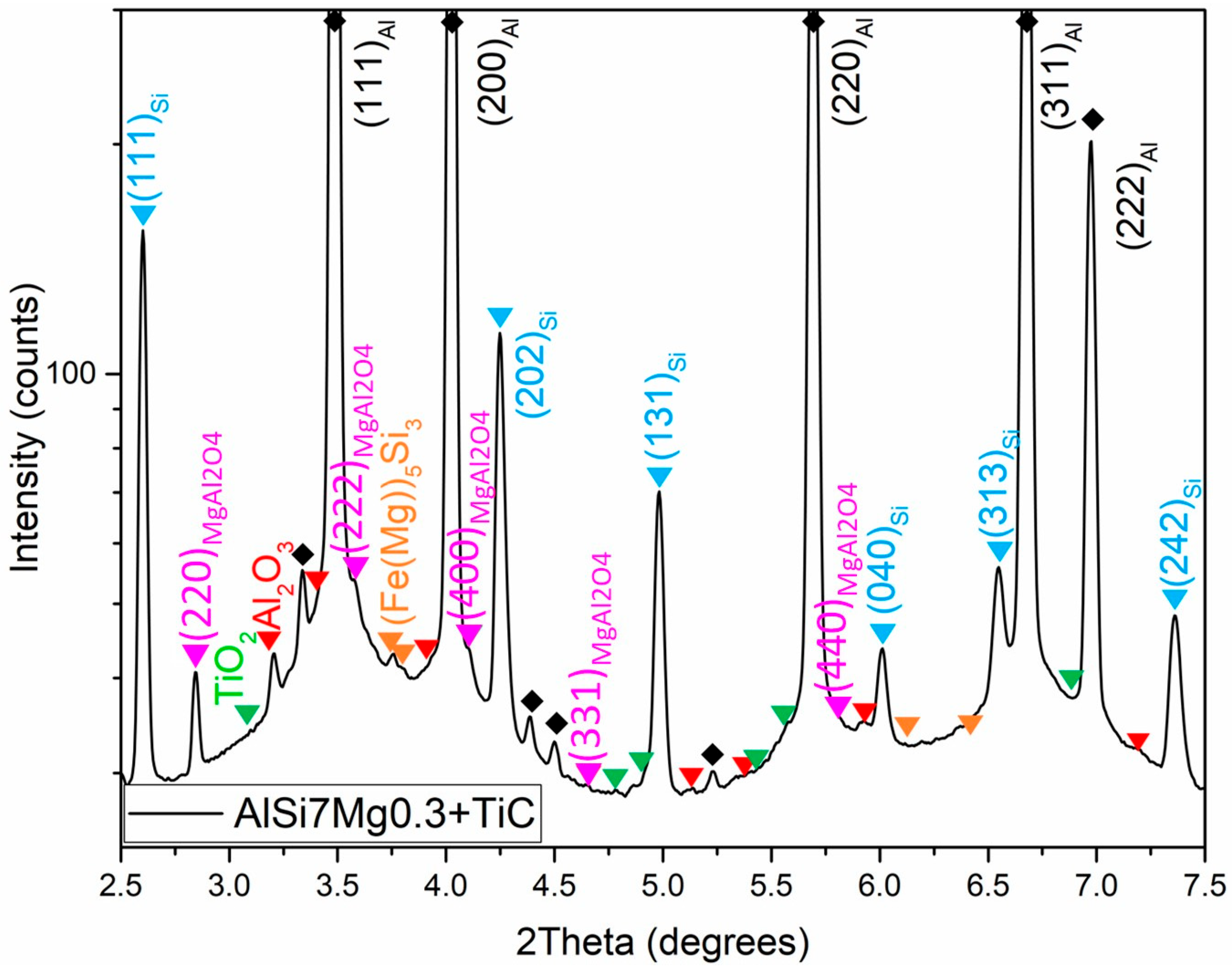

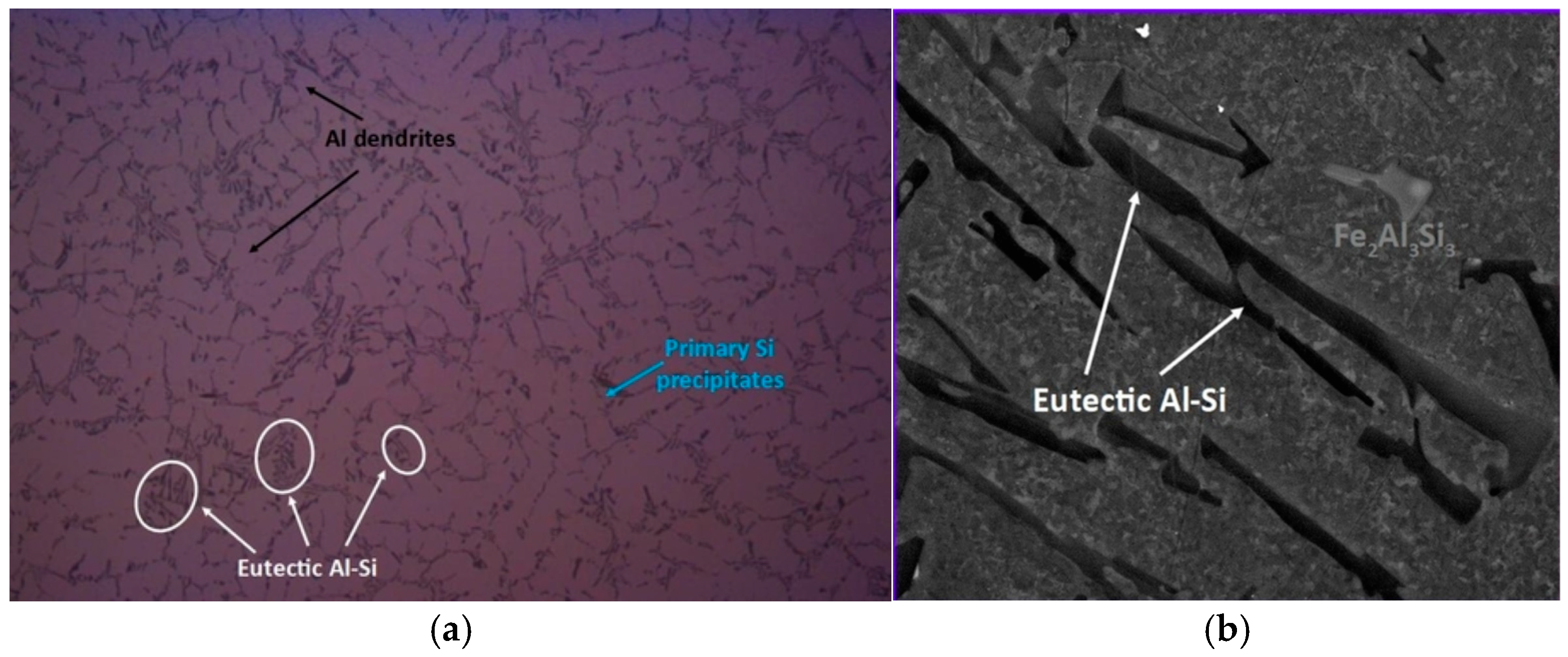

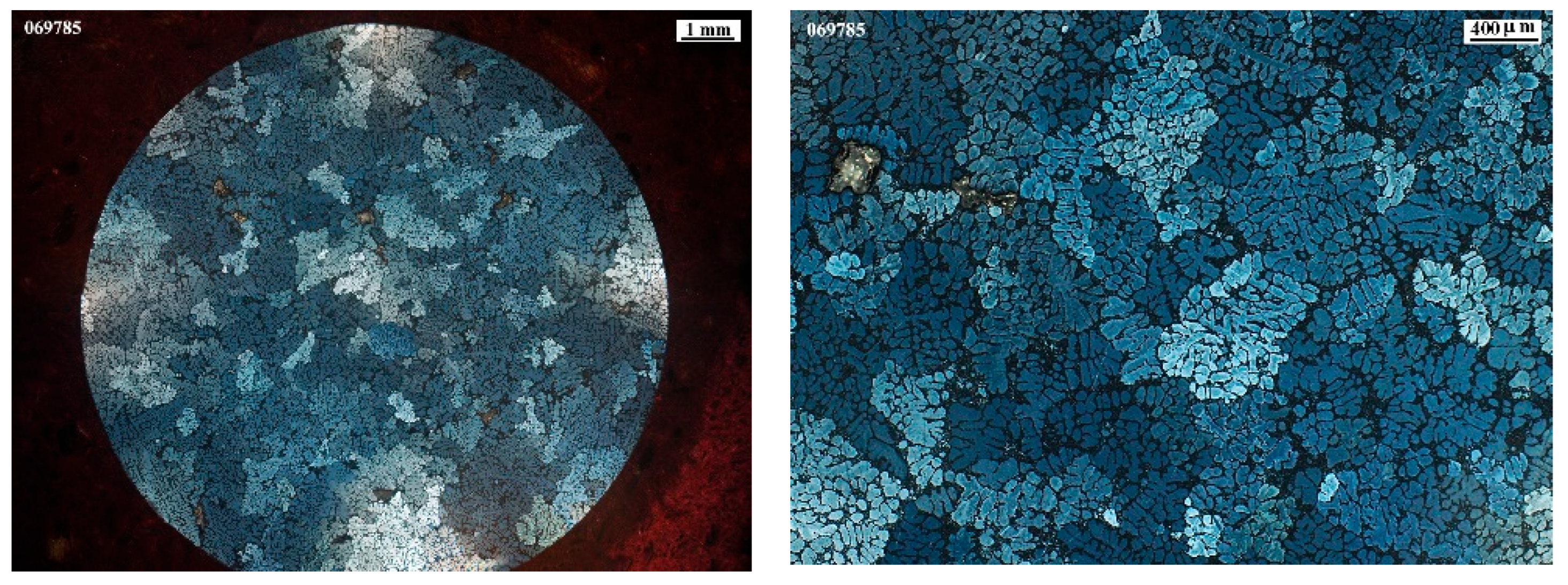

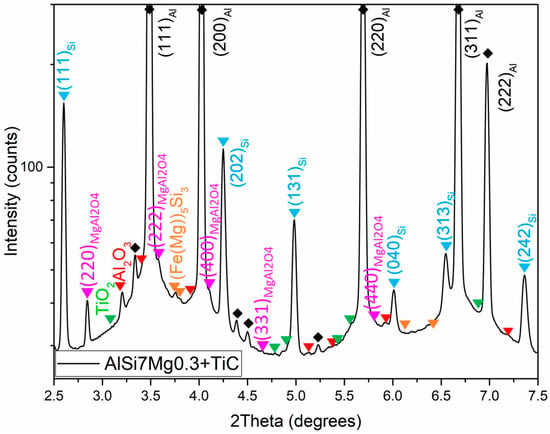

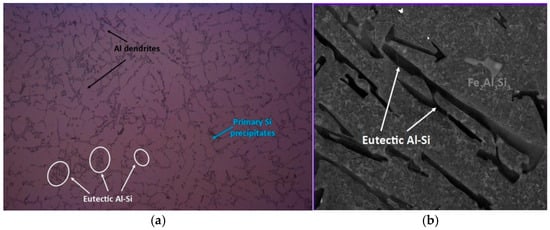

Figure 2 presents high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction patterns of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample. The main high intensity peaks are indexed in accordance with Al and Si phases, while TiC phase has not been found in the sample. The extra low-intensity reflections are identified as presumably TiO2, Al2O3, (Fe(Mg))5Si3, and MgAl2O4 phases. Their existence is related to the chemical composition of the base aluminum alloy as well as possible reactions occurring during melting and casting steps. Figure 3a,b shows the OM and backscattered scanning electron microscopy (BSE/SEM) images of the microstructure of the as-cast AlSi7Mg0.3 + 0.1wt.%TiC sample. The primary α–Al phase is surrounded by Al–Si eutectic, showing fibrous morphology (marked by white circles). Moreover, a small amount of extra (Fe (Mg))5Al3 phase is found and labeled with an orange arrow.

Figure 2.

High-energy X-ray diffraction pattern of AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC.

Figure 3.

(a) OM and (b) backscattered scanning electron microscopy (BSE/SEM) image of AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC.

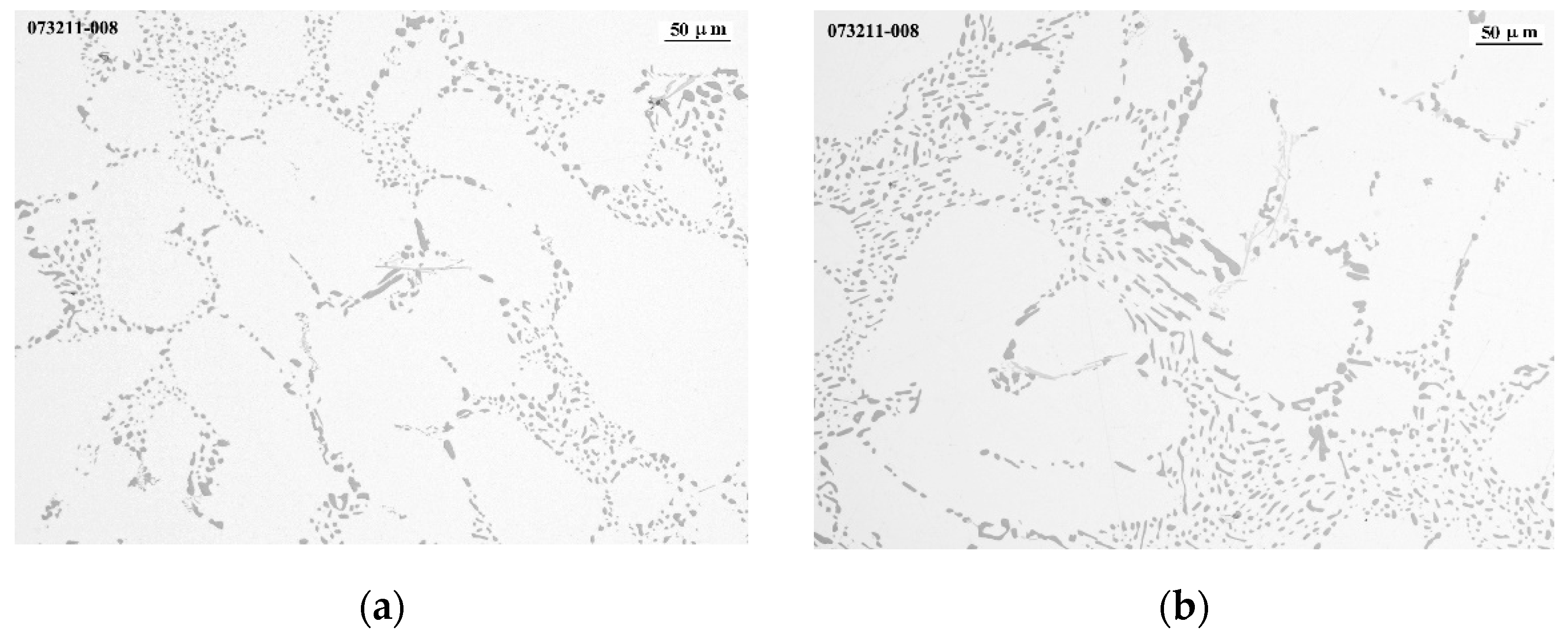

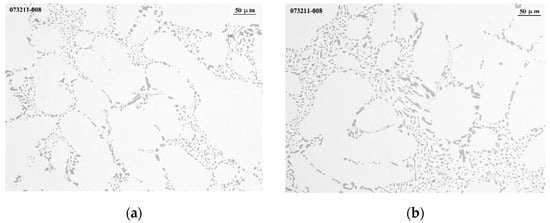

Figure 4 shows further OM images (×200) of both alloys, AlSi7Mg and AlSi7Mg-0.1 wt.% TiC. The microstructures present a similar aspect at these magnifications. The reinforced alloy seems to present a slightly smaller grain size, but there are not further differences in terms of porosity, oxide content, modifying of Si, or presence of different phases that can be appreciated with OM.

Figure 4.

Optical micrograph (OM) of (a) AlSi7Mg0.3 sample and (b) AlSi7Mg0.3 + 0.1 wt.% TiC sample produced by investment casting. (×200).

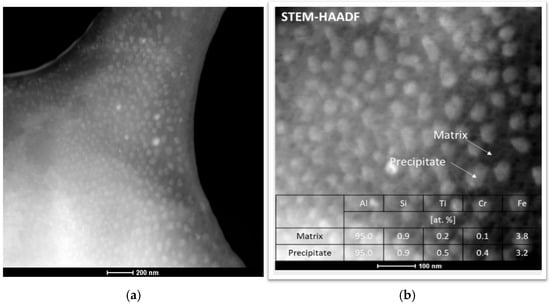

To validate the presence of all the phases identified through high-energy synchrotron X-ray diffraction, and given the relatively novel and scarcely documented fabrication method of the composite, extensive microstructural investigation was performed using TEM. A singular microstructural phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 5, which corresponds to the area of the reinforced sample exhibiting a substantial quantity of homogeneously distributed spherical precipitates. These precipitates, approximately 50 nm in size, were meticulously located using scanning transmission electron microscopy–high angle annual dark field (STEM-HAADF) imagining at various magnifications. The uniform distribution and size of these spherical precipitates suggest significant interactions and stability within the matrix. Furthermore, the results of the chemical analysis, obtained from both the matrix and the precipitates, are comprehensively presented in the table (inset of Figure 5). This analysis provides critical insights into the elemental composition and distribution within the composite, highlighting the influence of the reinforcements on the overall chemical makeup of the material. The detailed chemical characterization underscores the effectiveness of the fabrication method and its impact on the microstructural properties of the composite.

Figure 5.

STEM-HAADF images at (a) 50.000 magnifications and (b) 100.000 magnifications showing the area of the reinforced alloy with the large amount of homogenously distributed spherical precipitations with a size of about 50 nm.

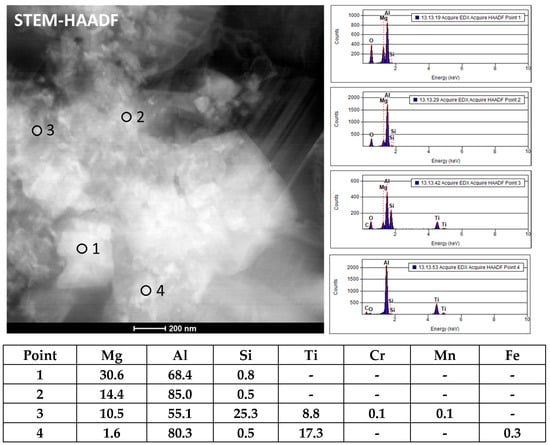

The chemical composition of the matrix and precipitates in Figure 5 shows slight differences, with the precipitates being enriched in Ti and Cr elements. Cr may appear as a contamination from the steel-chrome balls used in ball milling. Although the content of both elements is rather low, the TEM/EDS spectra and relative charge in the distribution are shown in the insert of Figure 5. Interestingly, it can be concluded that the Ti added to the composite in the form of TiC powder may have been absorbed by the matrix and precipitates. The size of precipitates and their homogenous distribution in the shown area might significantly improve the mechanical properties of the composite if they were homogeneously distributed in the entire sample. Figure 6 shows the microstructure taken from different regions of the sample with STEM-HAADF, and corresponding analytical results of chemical composition measured in different points are presented.

Figure 6.

STEM-HAADF microstructure and corresponding analytical results of chemical composition taken from different points of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample.

It is evident that despite the similarity in contrast at the examined points, primarily due to the high density of structural faults introduced during the stir casting process, there are notable differences in the chemical composition. By thoroughly analyzing the results presented in Figure 5, it can be concluded that the studied area contains an Al solution along with precipitates that have varying contents of Mg, Si, and Ti.

The presence of these elements in different concentrations suggests a complex microstructural composition, which can significantly influence the material’s properties. The high density of structural faults, such as dislocations and voids, introduced during the stir casting process, contributes to the observed contrast in the micrographs. These faults can act as sites for the nucleation and growth of precipitates, thereby affecting the overall distribution of elements within the matrix.

To further elucidate the distribution of these elements within the studied region, EDS maps were generated. EDS mapping is a powerful technique that allows for the visualization of the spatial distribution of elements within a sample. By using this technique, it is possible to obtain detailed information about the elemental composition and distribution at the microscale.

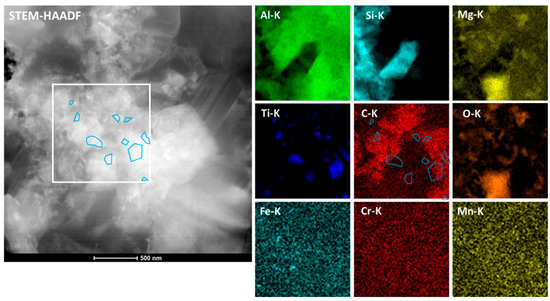

Figure 7 showcases the TEM/EDS elemental mapping obtained from the area highlighted in the STEM-HAADF microstructure. The EDS maps reveal the presence of distinct regions with varying concentrations of Mg, Si, and Ti, indicating the formation of different types of precipitates. These precipitates are likely to have a significant impact on the mechanical properties of the material, such as its strength, hardness, and ductility.

Figure 7.

STEM-HAADF microstructure of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample and corresponding results of elemental mapping performed on the indicated area.

In summary, the analysis of the microstructural and chemical composition of the studied area reveals a complex interplay between the Al solution and the precipitates with varying contents of Mg, Si, and Ti. The high density of structural faults introduced during the stir casting process plays a crucial role in the formation and distribution of these precipitates. The use of advanced characterization techniques, such as TEM/EDS elemental mapping, provides valuable insights into the microstructural features and elemental distribution within the material, which are essential for understanding its properties and performance.

In the analyzed area, Al and Si are the dominant elements, which indicates the pressure of two distinct solid solutions: α-Al and β-Si. The distribution of Mg reveals that it preferentially dissolves into de α-Al solid solution, suggesting its affinity for the aluminum-rich phase. However, considering the oxygen distribution, it can be expected that complex oxide phases belonging to the Al-Mg-O system can also be formed.

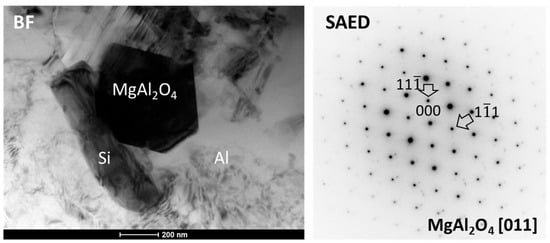

Moreover, there are also single, separated from each other, Ti particles ranging in size from approximately 90 to 200 nm. These Ti-rich particles appear to be correlated with C, as shown in the distribution of C on which the blue contours of the Ti particles are plotted, although it remains uncertain whether they are stoichiometric TiC or pure Ti particles associated with C. Trace amounts of Fe, Cr, and additional Mg were also detected, as shown in the elemental distribution maps and supported by quantitative data in the table (Figure 6). High-resolution bright-field (BF) images combined with selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns show that the area in Figure 7 enriched with Mg, O, and Al has a spinel structure of the MgAl2O4 type. This spinel phase was observed in the form of equiaxed grains with a size of about 0.5 µm and a cubic structure, characterized by a lattice parameter of a = 0.79829 nm, as confirmed by an SAED pattern oriented along the [011] zone axis (Figure 8). The presence of equiaxed spinel grains in the composite could also significantly improve its mechanical properties, thermal stability, and wear resistance, as reported by Singh et al. [17], Zhou et al. [18], and Zhou et al. [19].

Figure 8.

Bright field (BF) microstructure of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample and corresponding SAED image showing the MgAl2O4 spinel grain.

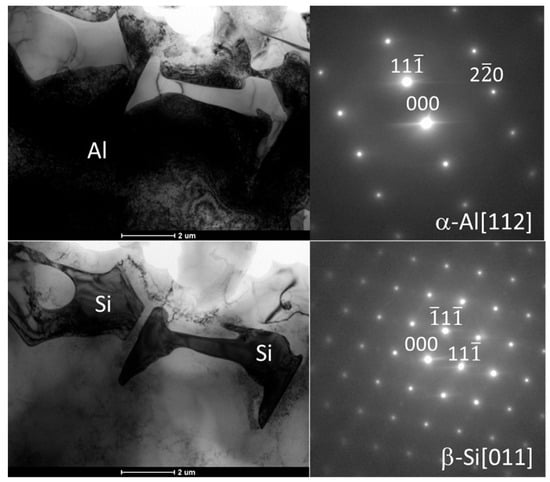

Figure 8 shows that the spinel grain is embedded in the α-Al matrix and is also adjacent to the β-Si solid solution. As can be seen in the table (Figure 6), the α-Al solid solution contains a small amount of both Mg and Si. The crystal structure of these phases was confirmed by electron diffraction. In Figure 9 BF microstructures and corresponding SAED patterns indexed in accordance with α-Al and β-Si phases are represented, respectively.

Figure 9.

Set of BF microstructures of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample and corresponding SAED patterns showing the eutectic α-Al and β-Si phases.

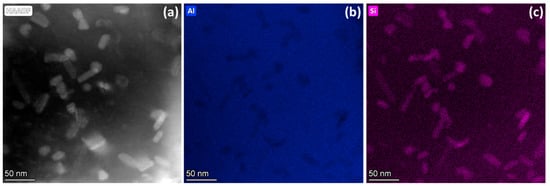

The β-Si phase was not present solely in eutectic form; primary β-Si crystals of nanometric dimensions were also observed within the aluminum matrix. As shown in Figure 10, the STEM-HAADF microstructure and corresponding elemental maps of Al and Si reveal that silicon particles with size of about 30 nm are homogeneously distributed in the aluminum matrix.

Figure 10.

STEM-HAADF microstructure of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample and corresponding elemental distribution of Al and Si. (a) General view, (b) Al, and (c) Si.

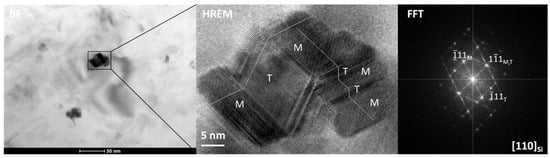

The results of microstructural observations of these particles in the conventional BF and high resolution (HRTEM) modes are presented Figure 11. In the BF microstructure, two Si nanoparticles with a size of about 30 nm embedded in aluminum matrix can be seen. The HRTEM image of a selected nanoparticle reveals a twin microstructure comprising two variants of nano-twins with {111}-type habit planes, as corroborated by the fast Fourier transform (FFT) analysis. Furthermore, the presence of additional diffraction spots between the main reflections indicates the occurrence of stacking faults in the crystallographic arrangement. The formation of such nano-twinning features within the matrix suggests that plastic deformation mechanisms were activated in the primary β-Si crystals during the stir casting process, likely as a result of the semisolid condition of the melt.

Figure 11.

BF, HREM, and FFT images of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC sample showing nanometric β-Si nanoparticle.

To summarize, it can be concluded that detailed microstructural studies have revealed the presence of a complex microstructure of the investigated reinforced alloy. This phenomenon is likely associated with the specific stir casting and investment casting process technologies, in which both intensive chemical reactions and shear stresses occur at semisolid temperatures in stir casting as well as the long cooling process of investment casting. These conditions may lead to partial dissolution of TiC particles that entail the precipitation and formation of complex phases containing several different elements such as Si, Fe, Cr, Mg, etc.

The partial dissolution of TiC particles observed during microstructural analysis appears to have played a significant role in shaping the final microstructure and properties of the material. It is well established that TiC can degrade when exposed to high temperature in liquid aluminum [20,21]. V.H. López et al. reported that the degradation of TiC in molten aluminum leads to the precipitation and growth of various Al-Ti and Al-Ti-Si polygonal intermetallic phases, as well as small Al4C3 and TiAl14Si0.38 angular blocks, particularly at temperature above 800 °C. They also concluded that the presence of Si enhances the dissolution kinetics of TiC.

However, the dissolution of TiC has been reported to occur at temperatures higher than those used in the present study, where significant dissolution was observed after 48 h at 700 °C [20,21]. It is thought that the submicron size and large surface area of the TiC particles may have contributed to the acceleration of these dissolution processes.

In the same work, it was additionally observed that during the solidification phase the solubility of Ti in Al decreases and C gets dissolved and may diffuse from the TiC structure until an equilibrium TiC(x-y) is achieved [20,21].

3.3. Grain Size Measurement

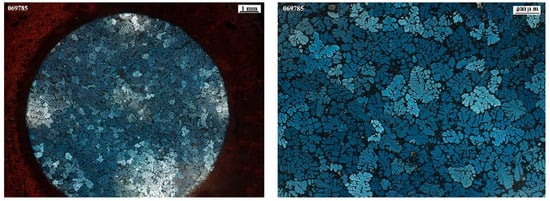

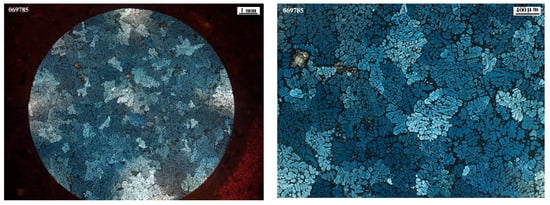

The grain size of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + TiC 0.1 wt.% samples were compared with samples of the reference alloy AlSi7Mg0.3. Figure 12 and Figure 13 provide the micrographs, and Table 3 shows the grain size number G calculation following the ISO 643:2024 standard, which showcases the results of the analysis.

Figure 12.

Micrographs of the Al-SiMg0.3 + 0.1 wt.% TiC alloy cast into ceramic shells following ISO 643:2024 standard [17].

Figure 13.

Micrographs of the Al-Mg.0.3 alloy cast into ceramic shells and following ISO 643:2024 standard [17].

Table 3.

Grain size number G calculation following the ISO 643:2024 standard.

As already reported in the literature, the presence of submicron sized TiC particles leads to a reduction in the grain size of the alloy. TiC particles may act as heterogeneous nucleation sites during the solidification of Al-Si alloys, which should lead to a more refined and equiaxed microstructure [22]. At the same time the secondary dendrite arm spacing (SDAS) is also decreased, which is also expected to have a strengthening effect over the alloy (López et al., n.d.) [21]. The reference alloy exhibits a grain size of 480 µm, with a SDAS of 41 ± 7 µm, while the grain size of the AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy reinforced with 0.1 wt.% TiC, produced using the same grain refiner (AlTi5B1) and silicon modifier (Al-Sr) amounts and equal processing conditions, is 320 µm, with a SDAS of 26 ± 11 µm. This expected reduction in grain size was anticipated to result in an improvement in both mechanical strength and ductility of the reinforced alloy. However, this expected improvement was not confirmed by the tensile test results (see Section 3.2 on mechanical properties). It can therefore be concluded that other factors affecting mechanical properties may have a more significant influence and should also be considered.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

In Table 4 mechanical properties (ultimate tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation) of the reinforcement alloy can be observed. The resistance and elongation values of the AlSi7Mg0.3 are compared with the values of the material obtained after the introduction of submicrometric TiC particles and subsequent casting and thermal treatment steps.

Table 4.

Mechanical properties and standard deviation of AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy; base alloy and after TiC particle’s introduction.

Although the incorporation of nano-sized and submicron-sized particles into Al-Si family alloys by stir casting processes is reported to increase both strength and elongation [23,24,25,26,27,28], in this case a marginal decline in performance is noted, with a reduction of approximately 5% in both ultimate tensile and yield strength, as well as a 10% decrease in elongation compared to the reference alloy.

It has been demonstrated that approximately 0.1 wt.% of submicron-sized particles were incorporated into the alloy, resulting in a decrease in the grain size of the material. This should have led to an improvement of mechanical properties that has not been corroborated by tensile test results. It seems that other phenomena have taken place that may have negatively affected the microstructure and may explain the slight decrease in the mechanical properties of the reinforced alloy.

The optical microscopy analysis did not reveal any signs of increased porosity in the reinforced alloy. Additionally, there is only limited evidence suggesting potential contamination of the material during the stir casting or investment casting processes. Some oxides, such as TiO2 and Mg-based spinels, were identified in the microstructure, along with traces of chromium, which may have originated from contamination by steel jars used in the ball milling process to mix the aluminum and TiC powders. However, the presence of these defects appears to be minimal, and their impact on the material properties is considered negligible.

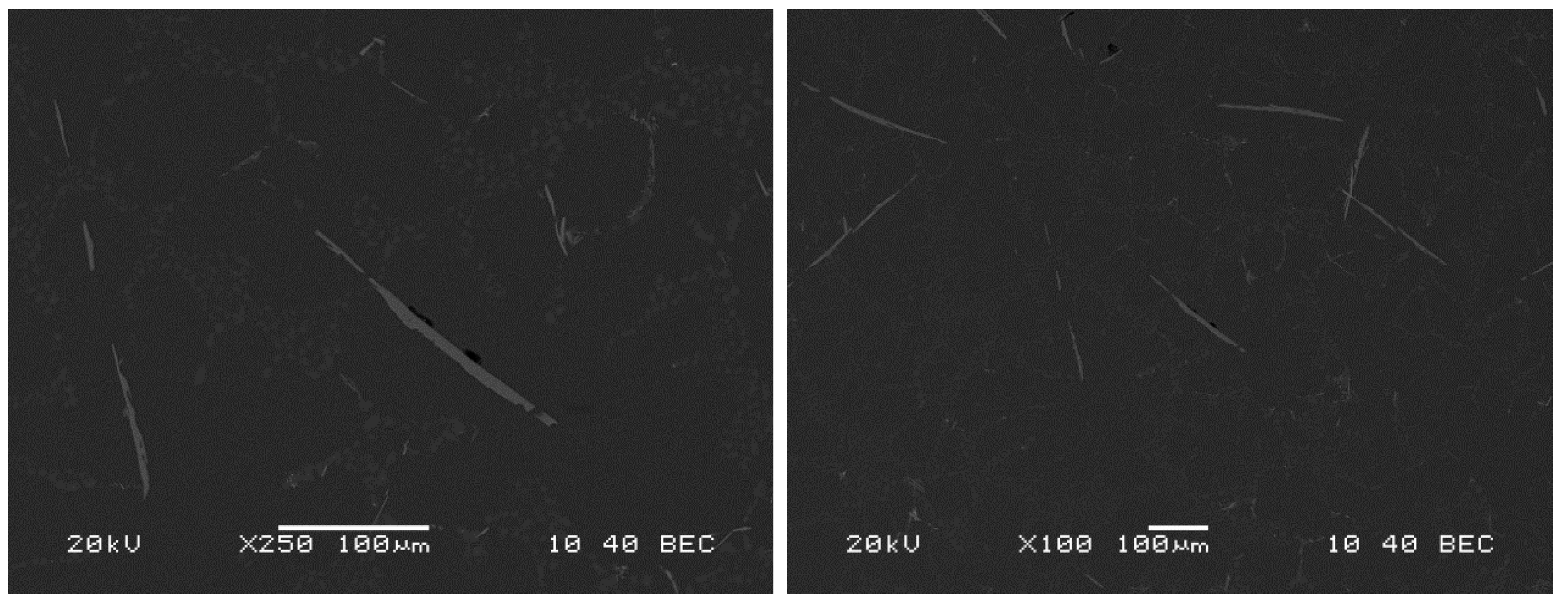

SEM and TEM analyses have revealed additional phenomena that may better explain the observed results. The most significant finding is the partial dissolution of TiC particles during the melting and solidification stages. Dissolution of Ti-containing phases is quite common, and it is moreover easier when the particle size is smaller, as already reported by other authors [29]. Although chemical analysis of the final material showed an increase in elemental Ti content of up to 0.1 wt.%, the actual number of remaining TiC particles appeared to be much lower. Moreover, the size of the identified TiC particles is smaller than the 300 nm average size of the original TiC powder used in the study. This partial dissolution is likely attributed to the extended cooling time in investment casting, which increased the contact time between the submicron TiC particles and liquid aluminum. The small initial size and high surface area of these particles, combined with the elevated casting temperature, may have facilitated the dissolution of Ti and C into the melt.

In addition, the microstructural analysis showed that the previous phenomena may have led to the formation of the complex microstructure observed. Apart from typical phases of investment cast Al-Si alloys, the reinforced alloy contains other phases that may affect negatively mechanical properties of the alloy. The most relevant microstructural features may be summarized as follows:

- Areas containing homogeneously distributed spherical precipitates, approximately 50 nm in size and enriched in Ti and Cr (Al 95.5%, Si 0.9%, Ti 0.5%, Cr 0.4%, and Fe 3.2%), were observed. The precise effect of such particle agglomeration on the properties of the final material was not determined; however, these regions may have acted as stress concentration sites (Figure 5).

- Ti particles associated with carbon and measuring 90–120 nm in size were observed. It was not clear whether these were Ti particles or TiC-type particles with different stoichiometry. However, their size was clearly smaller than the original TiC particles used in the study. It appears that the small TiC particles underwent diffusion processes, where Ti and C diffused into the liquid aluminum, affecting their geometrical stability (See Figure 7).

- The presence of primary nanometric β-Si crystals with an average size of 30 nm was confirmed (see Figure 11).

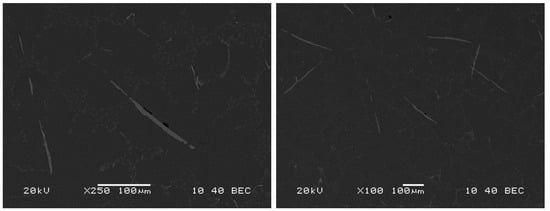

- Presence of complex Ti-Si-Cr-Mg phases with many needle-shaped structures that appear mainly located into the grain boundaries (See Figure 14 below).

Figure 14. Backscattered scanning electron microscopy (BSE/SEM) images of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + 0.1 wt.% alloy where a large amount of brittle needle-shaped structures are shown.

Figure 14. Backscattered scanning electron microscopy (BSE/SEM) images of the AlSi7Mg0.3 + 0.1 wt.% alloy where a large amount of brittle needle-shaped structures are shown.

The ductility of the reinforced alloy was 10% lower than that of the reference AlSi7Mg0.3 samples, despite the reduction in grain size achieved in the former. This can be explained by the microstructural changes described above. It was also well established that the distribution of nanoparticles has a significant influence on elongation at fracture. In cases where this distribution is inhomogeneous and does not extend uniformly throughout the sample, ductility is typically comparable to, or even lower than, that of non-reinforced alloys.

4. Conclusions

The objective of the work was to evaluate the effect of incorporating up to 0.1 wt.% submicron-sized TiC particles into AlSi7Mg0.3 investment cast components. It was observed that the addition of TiC particles did not result in the expected improvement in mechanical properties. A reduction in grain size and the presence of hard submicron ceramic particles—expected to hinder dislocation movement through Orowan or CTE mismatch mechanisms—were observed. Nevertheless, other effects appeared to partially offset these benefits. The main issue seemed to be the diffusion of Ti and C from the particles into the aluminum melt. Microstructural analysis revealed a complex structure containing multiple new phases not present in the reference alloy.

It is concluded that the slow solidification inherent to the investment casting process, combined with the small size and nature of submicron TiC particles, led to additional phenomena during the solidification process that may explain the obtained results.

The microstructure shows special features related to this dissolution process. Ti particles associated with C, with sizes in the range of 90–120 nm, have been identified. It remains unclear whether these particles are Ti or TiC-type particles with a different stoichiometry.

The existence of nanometric primary β-Si phases in the matrix, which may result from the semisolid nature of the stir casting process, could be attributed to plastic deformation phenomena of the primary β-Si crystals during the stirring process.

Additionally, needle-shaped phases containing titanium were identified in the grain boundary regions, which were expected to have a negative impact on the ductility and mechanical strength of the samples.

In conclusion, although the incorporation of the desired particles into the melt was confirmed to some extent, subsequent analysis revealed that most of the particles had either disappeared or decreased in size. This is likely due to the diffusion of both Ti and C into the aluminum matrix during the processing and solidification conditions of investment casting process [23,24,25,26,27,30].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W.; Methodology, A.J., W.M. and M.M.; Validation, A.W.; Resources, W.M.; Writing—original draft, A.J., W.M. and M.M.; Writing—review & editing, A.W. and M.G.d.C.; Supervision, A.J. and M.M.; Project administration, M.G.d.C.; Funding acquisition, M.G.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the Basque Government through the Elkartek program (KK-2024/00061).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Ane Jimenez, Mikel Merchán and Maider Garcia de Cortazar were employed by TECNALIA, Basque Research and Technology Alliance (BRTA). The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Koli, D.K.; Agnihotri, G.; Purohit, R. Advanced Aluminium Matrix Composites: The Critical Need of Automotive and Aerospace Engineering Fields. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 3032–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosselle, F.; Timelli, G.; Bonollo, F. Doe applied to microstructural and mechanical properties of Al-Si-Cu-Mg casting alloys for automotive applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 3536–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morri, A. Empirical models of mechanical behaviour of Al-Si-Mg cast alloys for high performance engine applications. Metall. Sci. Technol. 2010, 28, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hockauf, M.; Wagner, M.F.-X.; Hände, M.; Lampke, T.; Siebeck, S.; Wielage, B. High-strength aluminum-based light-weight materials for safety components—Recent progress by microstructural refinement and particle reinforcement. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 103, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.Y.; Jiang, Y.H.; Ma, Z.; Shan, S.F.; Jia, Y.Z.; Fan, C.Z.; Wang, W.K. Effect of cooling rate on solidified microstructure and mechanical properties of aluminium-A356 alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 207, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, M.O.; Mazahery, A. Prediction of mechanical properties of cast A356 alloy as a function of microstructure and cooling rate. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2011, 56, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Previtali, B.; Pocci, D.; Taccardo, C. Application of traditional investment casting process to aluminium matrix composites. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2008, 39, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidari, S.; Patil, A.; Banapurmath, N.; Hallad, S. Effect of Nanoparticle Reinforcement in Metal Matrix for Structural Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 9552–9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamfard, S.; Khosroshahi, R.A.; Brabazon, D.; Mousavian, R.T. Study on the incorporation of ceramic nanoparticles into the semi-solid A356 melt. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 230, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-s.; Yuan, D.; Lü, S.-l.; Hu, K.; An, P. Nano-SiCP particles distribution and mechanical properties of Al-matrix composites prepared by stir casting and ultrasonic treatment. China Foundry 2018, 15, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casati, R.; Vedani, M. Metal matrix composites reinforced by Nano-Particles—A review. Metals 2014, 4, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschini, L.; Dahle, A.; Gupta, M.; Jarfors, A.E.W.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Morri, A.; Rotundo, F.; Toschi, S.; Singh, R.A. Aluminum and Magnesium Metal Matrix Nanocomposites; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodianskiy, K.; Zinigrad, M.; Gedanken, A. Aluminum A356 reinforcement by carbide nanoparticles. J. Nano Res. 2011, 13, 41–46. Available online: https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/JNanoR.13.41 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Ferreira, V.; Egizabal, P.; Popov, V.; de Cortázar, M.G.; Irazustabarrena, A.; López-Sabirón, A.M.; Ferreira, G. Lightweight automotive components based on nanodiamond-reinforced aluminium alloy: A technical and environmental evaluation. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2019, 92, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, B.T.; Koppad, V.; Raju, H.T. Fabrication of Stir Casting Setup for Metal Matrix Composite. Int. J. Sci. Res. Dev. 2017, 5, 944–949. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E8/E8M-24; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 1–35. [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN ISO 643:2024; Aceros: Determinación Micrográfica del Tamaño de Grano Aparente. Comité Técnico CTN36 Siderurgia: Madrid, Spain, 2024.

- Singh, S.; Pal, K. Influence of surface morphology and UFG on damping and mechanical properties of composite reinforced with spinel MgAl2O4-SiC core-shell microcomposites. Mater. Charact. 2017, 123, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, N.; Shi, C.; Liu, E.; Du, X.; He, C. Microstructure and properties of in situ generated MgAl2O4 spinel whisker reinforced aluminum matrix composites. Mater. Des. 2013, 46, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, N.; Shi, C.; Liu, E.; Du, X.; He, C. In-situ processing and aging behaviors of MgAl2O4 spinel whisker reinforced 6061Al composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 598, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V.H.; Kennedy, A.R.; García, R.; Verduzco, J.A. Efecto del Si en la estabilidad térmica del Tic en aluminio fundido. Rev. Latinoam. Metal. Mater. 2012, 32, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, H.; Xiao, W.; Li, H.; Fu, Y.; Yi, G.; Qie, J.; Ma, X.; Ma, C. Effects of submicron-sized TiC particles on the microstructure modification and mechanical properties of Al-Si-Mg alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 968, 171963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahallawi, I.; Abdelkader, H.; Yousef, L.; Amer, A.; Mayer, J.; Schwedt, A. Influence of Al2O3 nano-dispersions on microstructure features and mechanical properties of cast and T6 heat-treated Al Si hypoeutectic Alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 556, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Awaji, H. Nanocomposites—A new material design concept. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2005, 6, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahallawi, I.S.; Shash, Y.; Eigenfeld, K.; Mahmoud, T.S.; Ragaie, R.M.; Shash, A.Y.; El Saeed, M.A. Influence of nanodispersions on strength-ductility properties of semisolid cast A356 Al alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2010, 26, 1226–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazahery, A.; Abdizadeh, H.; Baharvandi, H.R. Development of high-performance A356/nano-Al2O3 composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 518, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, S.A.; Ezatpour, H.R.; Beygi, H. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Al2O3 micro and nano composites fabricated by stir casting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 8765–8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghan Hamedan, A.; Shahmiri, M. Production of A356-1wt% SiC nanocomposite by the modified stir casting method. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 556, 921–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, M.; Shi, Q.; Jiang, B.; Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Ji, Z. Population dynamics behaviors of TiC and their effect on grain refinement in Al–Ti–C refiners: Growth, agglomeration, nucleation and precipitation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 1758–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V.H.; Kennedy, A.R.; Verduzco, J.; López, V.H.; García, R.; Verduzco, J.A. Reaction Kinetics for TiC Particles in Molten Aluminium. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332511019 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.