Investigation on the Viscosity and Fluidity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 Ternary Primary Slag in Cohesive Zone of Blast Furnace

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

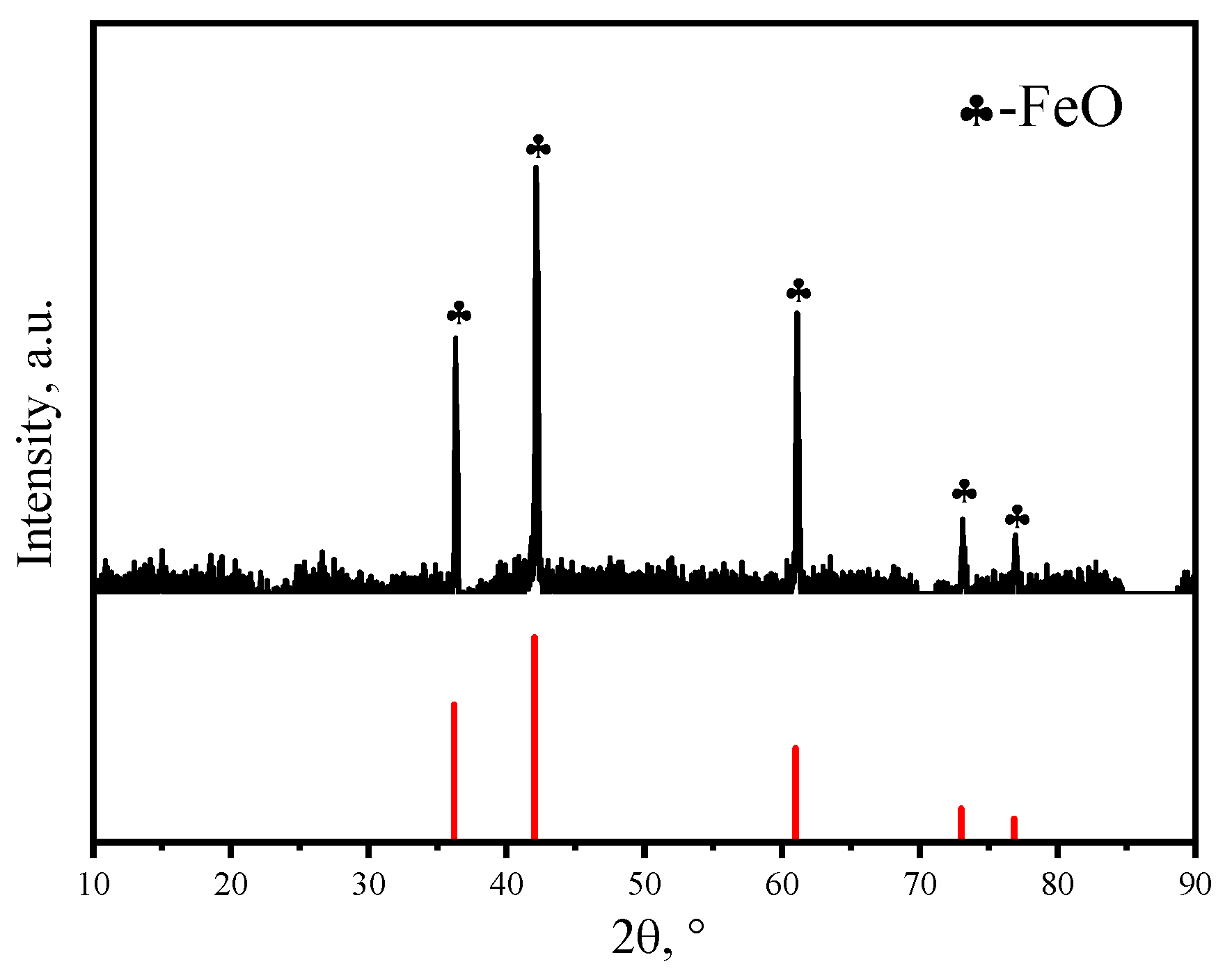

2.1. Raw Materials

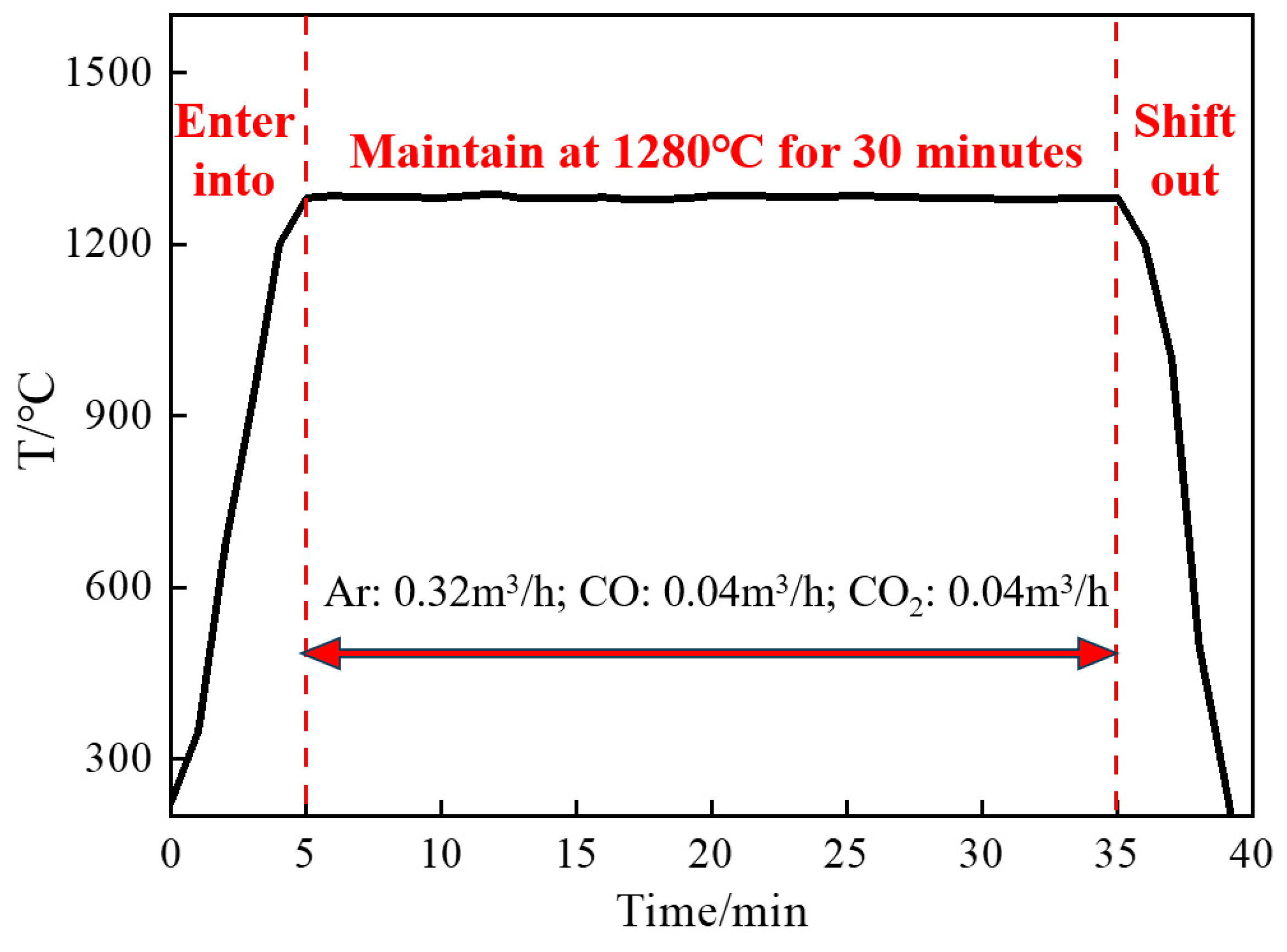

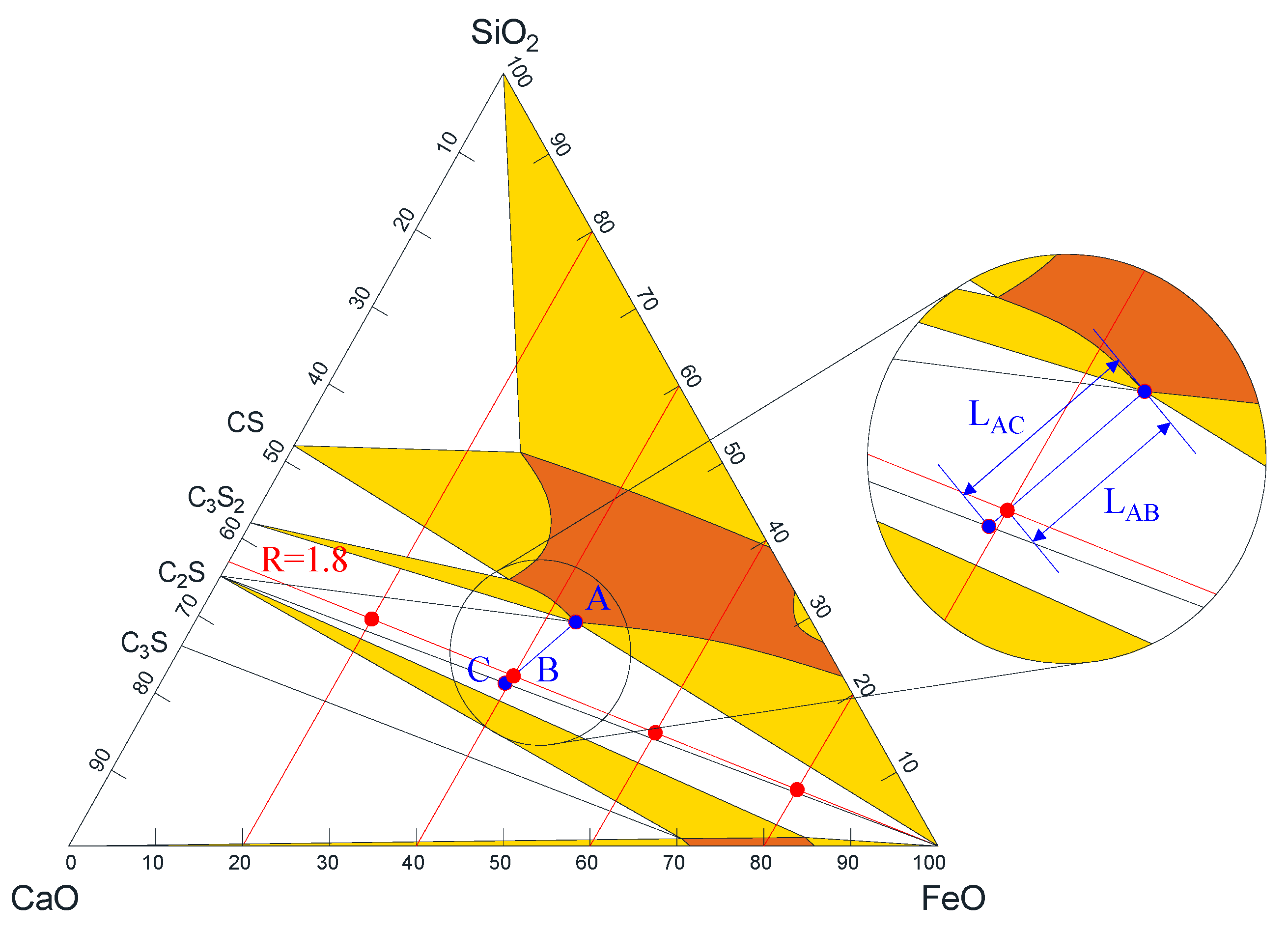

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Fluidity Tests

2.4. Determination of Solid–Liquid Coexistence-Phase Viscosity

2.4.1. Determination of System Composition and the Quantity of Solid Phase

2.4.2. Calculation Model of Liquid-Phase Viscosity

2.4.3. Calculation Model of Solid–Liquid Coexistence-Phase Viscosity

3. Results

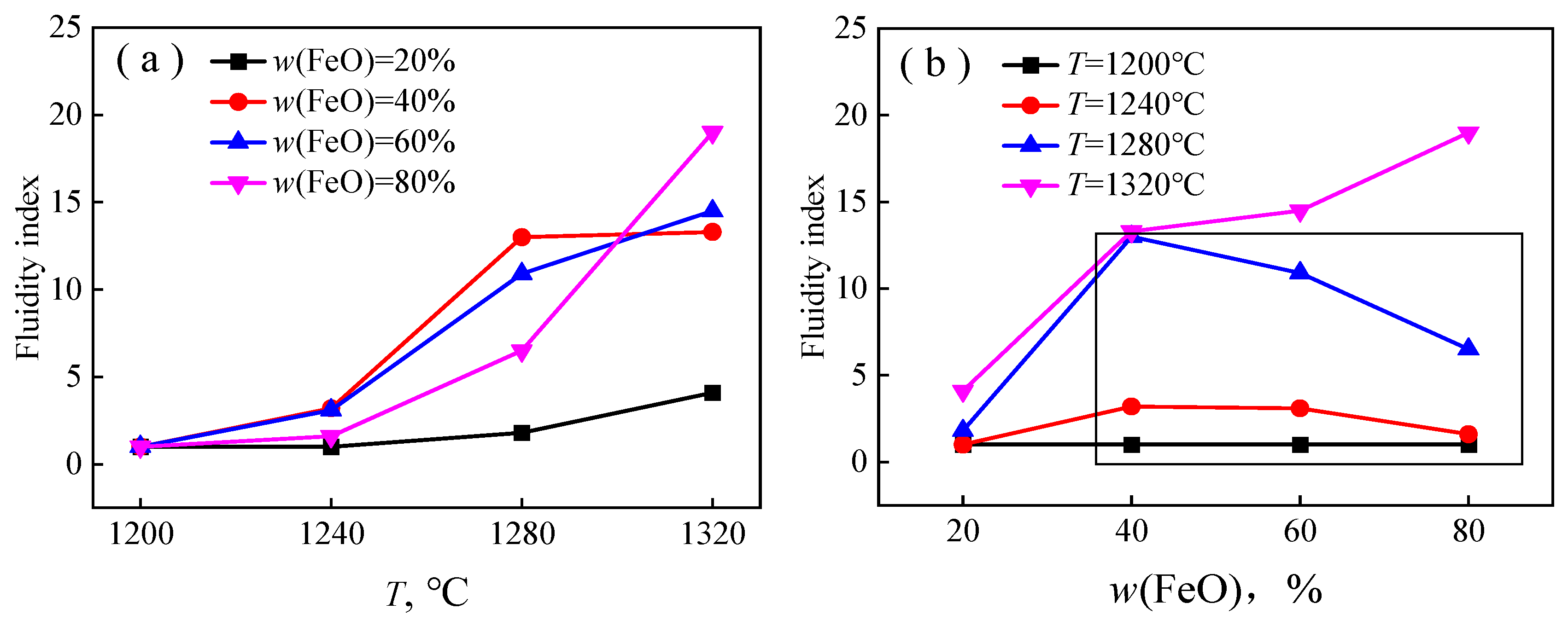

3.1. Fluidity Index Test Result

3.2. Calculation Results of Solid–Liquid Coexistence-Phase Viscosity

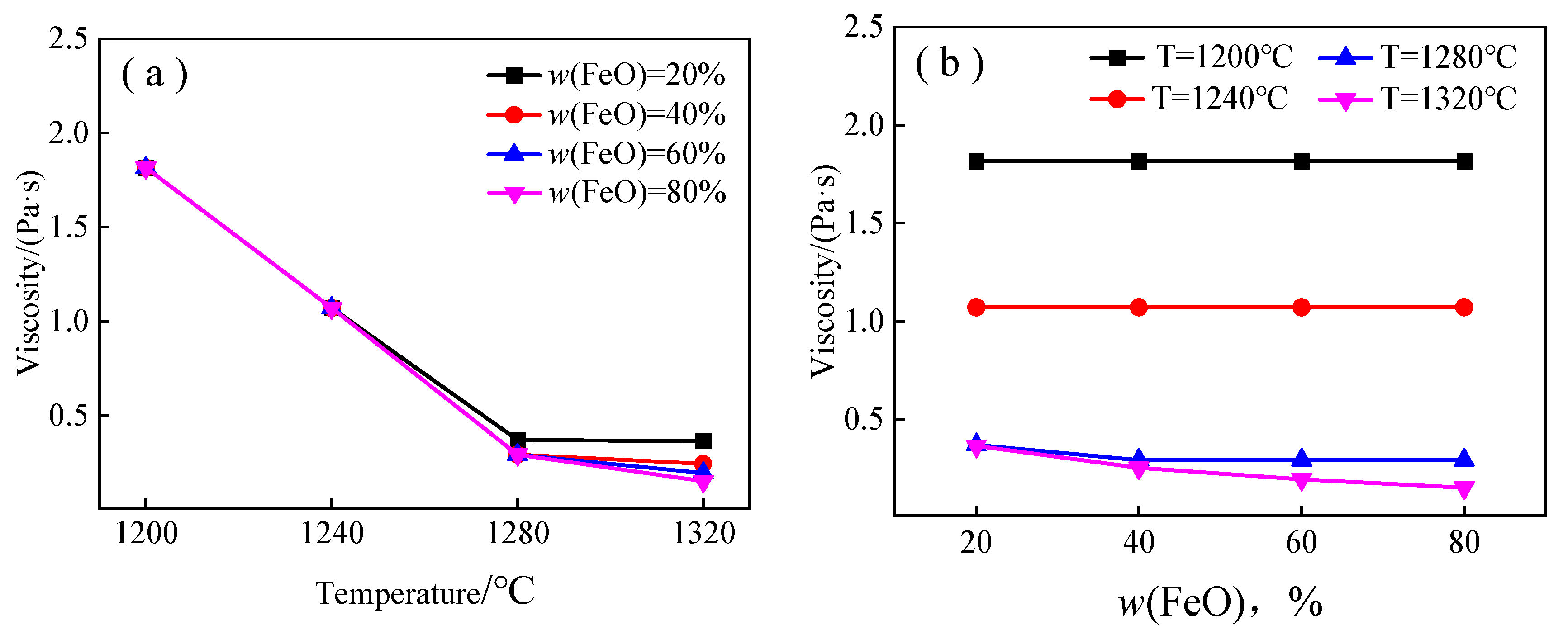

3.2.1. Calculation Results of Liquid-Phase Viscosity

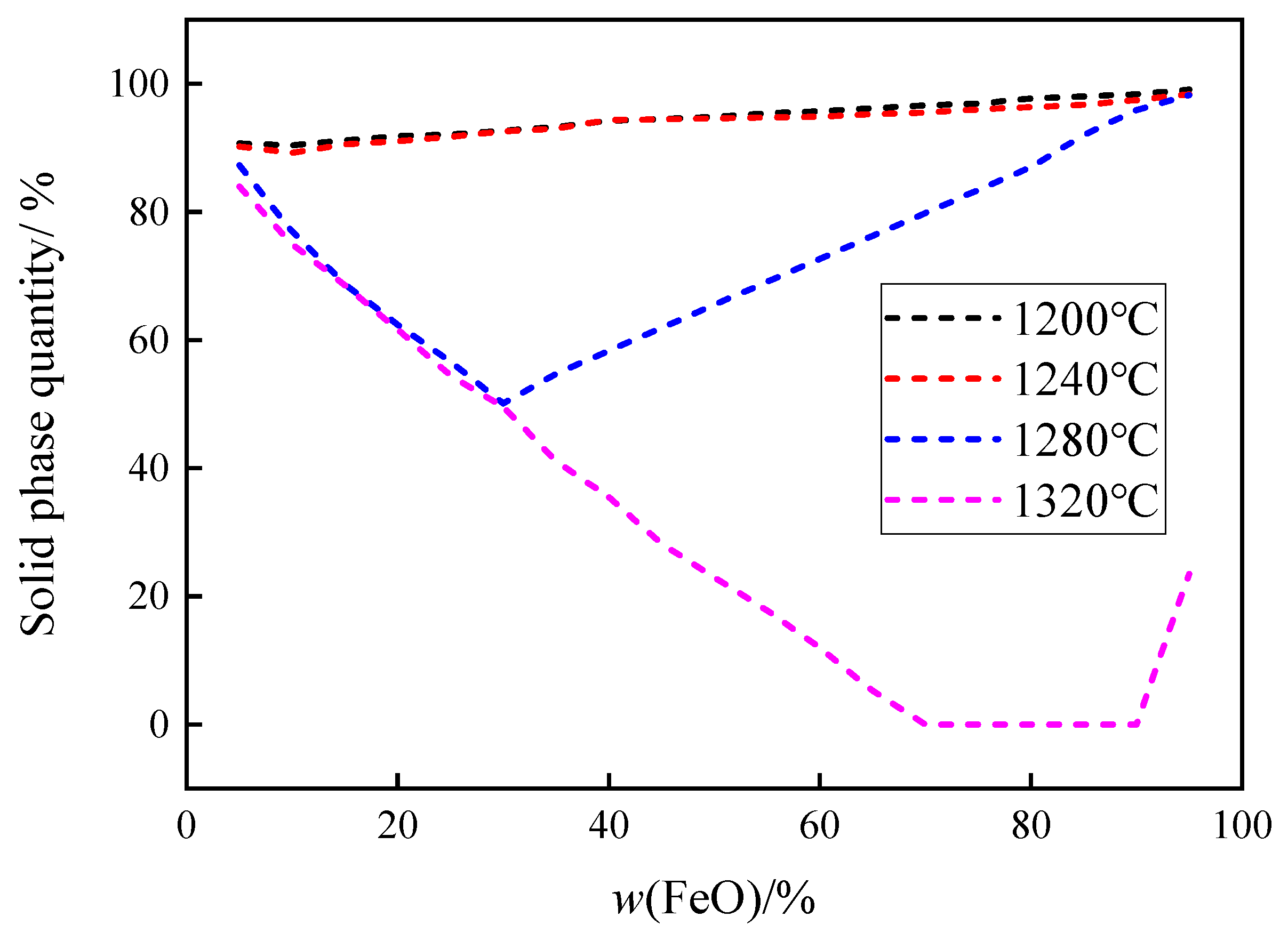

3.2.2. Calculation Results of the Quantity of Solid Phase

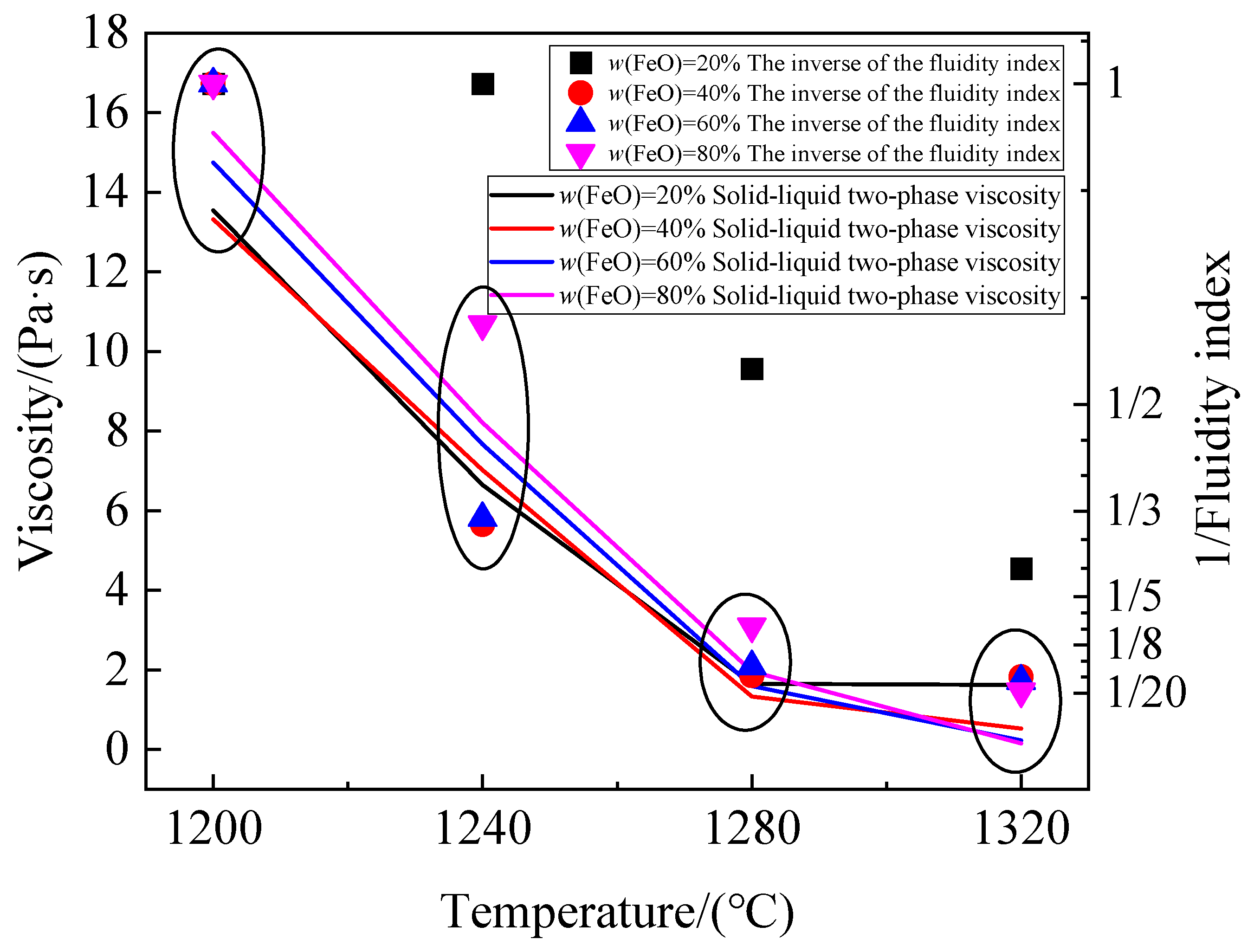

3.2.3. Accuracy Comparison of Solid–Liquid Coexistence-Phase Viscosity Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- For the primary slag of the FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system, when w (FeO) is constant, the fluidity index of each primary slag increases with the increase in temperature, T. When the temperature (T) is constant, the fluidity index of primary slag in non-three-phase region increases with the increase in w (FeO), while that in the three-phase region decreases with the increase in w (FeO).

- (2)

- The Kondratiev model and the Batchelor model were jointly employed to calculate the primary slag viscosity in the cohesive zone. According to this model, when w (FeO) = 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80%, the viscosity of the FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system at 1200 °C is 13.55 Pa·s, 13.32 Pa·s, 14.74 Pa·s, and 15.49 Pa·s, respectively. The viscosity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system at 1320 °C is 1.62 Pa·s, 0.53 Pa·s, 0.23 Pa·s, and 0.15 Pa·s, respectively. At the same temperature, the solid–liquid coexistence-phase viscosity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system is mainly controlled by the quantity of solid phase (w (FeO)). The different w (FeO) in the primary slag formed by different sinters is the main reason for the different permeability of cohesive zone.

- (3)

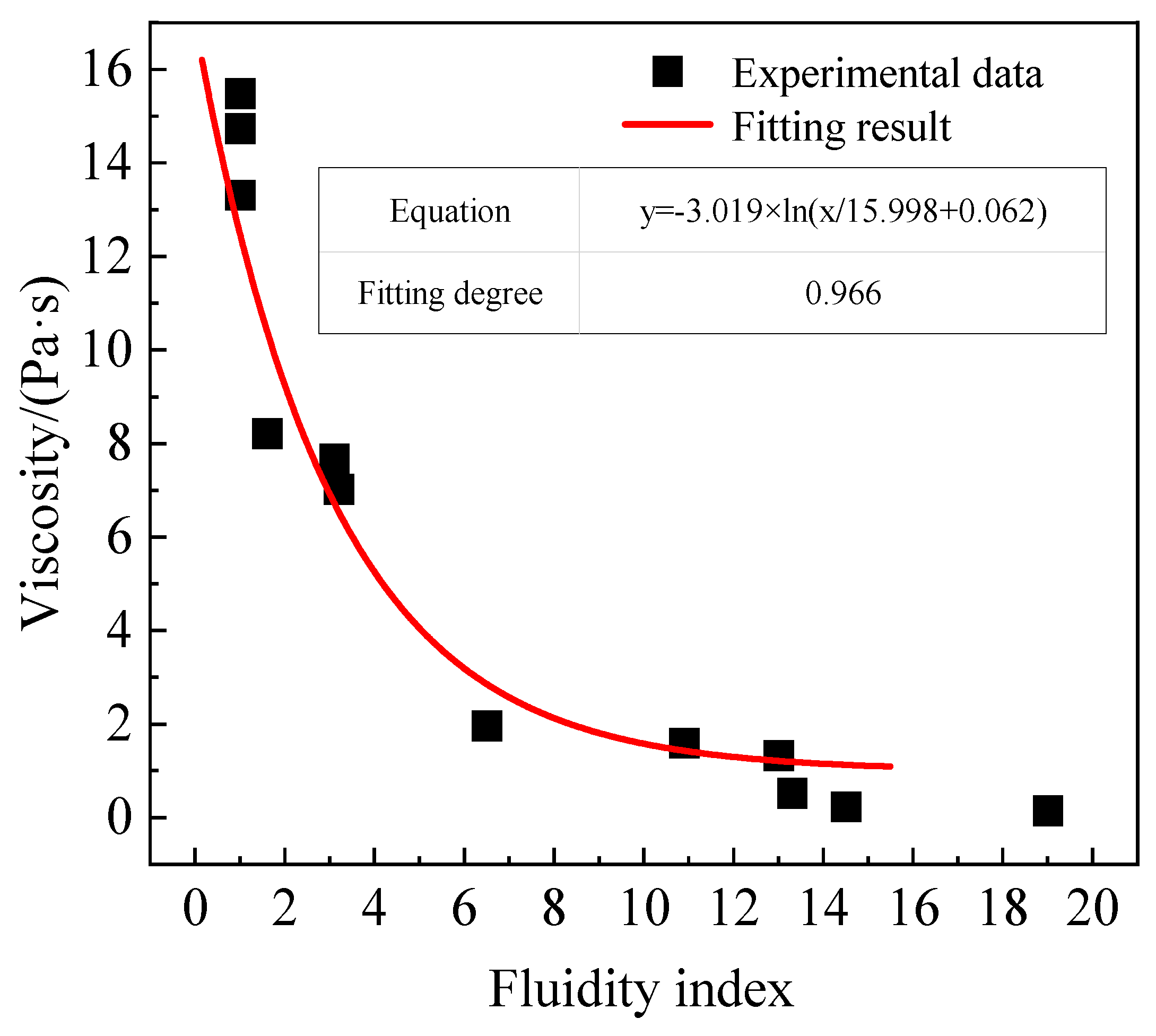

- In the FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system, there is an approximate logarithmic correlation between the solid–liquid coexistence-phase viscosity and the fluidity index. The relationship between them is determined by coupling as follows: —solid–liquid coexistence-phase viscosity; and —fluidity index), and the fitting degree can reach 0.966. According to the formula, the viscosity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 ternary slag system can be calculated by the composition and temperature of the primary slag, and then the fluidity index of the slag system can be obtained. Also, the viscosity of the primary slag is difficult to test, but it can be obtained by measuring the fluidity index. The relative error value of predicting the fluidity of the slag system using this method is only about 8.43%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, Z.Y.; Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L. Graphitization Behavior of Coke in the Cohesive Zone. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2018, 49, 2956–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.Y.; Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, K.D.; Chang, Z.Y. Phase Transformation of Cohesive Zone in a Water-quenched Blast Furnace. ISIJ Int. 2018, 58, 1775–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, T. Dissection Investigation of Blast Furnace Hearth—Kokura No. 2 Blast Furnace (2nd Campaign). ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Qie, Y.N.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhu, J.Q.; Liu, R.; Ji, H. Research status and prospect of softening-melting properties for blast furnace charge. China Metall. 2024, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.L.; Chen, Z.C.; Zhan, W.L.; Lui, J.H.; Zhang, J.H.; He, Z.J. Influence of different initial slag basicity on the retention performance of slag and iron in blast furnace. Energy Metall. Ind. 2025, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, N.; Zhou, Z.; Ning, Z.; Chen, M. Effect of combined ferrous burden composition and ore-coke interaction on blast furnace burden distribution. Powder Technol. 2025, 449, 120416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Wu, H.Z.; Hu, Z.W.; Zhang, J.L. Influence of high basicity slag on BF smelting and corresponding operating system suggested. Ironmaking 2025, 44, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, A.Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Chang, D.Q. Effects of MgO on the mineral structure and softening-melting property of Ti-containing sinter. Chin. J. Eng. 2018, 40, 184–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kohei, S.; Masahiko, H. Effect of High Al2O3 Slag on the Blast Furnace Operations. ISIJ Int. 2008, 48, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.; Ono-Nakazato, H.; Kawabata, H.; Usui, T.; Tanaka, T. Reduction Behavior of FeO Compact Including Molten Slag. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 2100–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Higuchi, K.; Naito, M.; Kunitomo, K. Evaluation of Softening, Shrinking and Melting Reduction Behavior of Raw Materials for Blast Furnace. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 1316–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Shen, F.M.; Du, G.; Du, H.G. Thermal strength requirement and testing method for blast furnace coke. J. Mater. Metall. 2011, 10, 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.M.; Jiang, X.; Wei, G.; Shen, F.M. Numerical Simulation for the Influence of Cohesive Zone Shape on Distribution of Unburned Pulverized Coal in Blast Furnace. J. Northeast Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018, 39, 1242–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, D.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Y.F.; Alessio, J.D.; Ferron, K.J.; Zhou, C.Q. CFD modelling of multiphase reacting flow in blast furnace shaft with layered burden. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 66, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.F.; Pinson, D.; Zhang, S.J.; Yu, A.B.; Zulli, P. Gas-powder flow in blast furnace with different shapes of cohesive zone. Appl. Math. Model. 2006, 30, 1293–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, T.L.; Sun, C.Y.; Wang, Q. Effect of FeO and Al2O3 contents on viscosity of primary slag. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Liaoning 2017, 40, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, L.M.; Liu, L.L.; Zhang, Z.T.; Wang, X.D. Experimental Research and Prediction Model on Viscosity of High FeO Content Slag. Iron Steel 2012, 47, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- She, W.W.; Liu, Z.J.; Chen, X.M.; Yang, J.L. Effect of FeO, Al2O3 and MgO mass fraction on viscosity of blast furnace primary slag. China Metall. 2019, 29, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Carles, V.; Alphonse, P.; Tailhades, P.; Rousset, A. Study of thermal decomposition of FeC2O4·2H2O under hydrogen. Thermochem. Acta 1999, 334, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Chen, C.L.; Liu, Y.X. Effect of TiO2 and FeO on the Viscosity and Structure of Blast Furnace Primary Slags. Steel Res. Int. 2017, 88, 1600296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, C.Y.; Song, S.; Wang, Q. Influences of Al2O3 and TiO2 Content on Viscosity and Structure of CaO-8%MgO-Al2O3-SiO2-TiO2-5%FeO Blast Furnace Primary Slag. Metals 2019, 9, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.A.; Jiang, X.; Gao, Y.; Huo, H.Y.; Shen, F.M. Investigation on fluidity of SFCA and sintering strength based on phase diagram. Iron Steel 2019, 54, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Zhao, J.D.; Wang, L.; An, H.W.; Gao, Q.J.; Zheng, H.Y.; Shen, F.M. Effects of Liquidus Temperature and Liquid Amount on the Fluidity of Bonding Phase and Strength of Sinter. ISIJ Int. 2020, 61, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.L.; Pei, Y.D.; Chen, H.; Peng, P.; Yang, F. Evaluation on liquid phase fluidity of iron ore in sintering. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2008, 30, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.L.; Du, J.X.; Ma, H.B.; Tian, Y.Q.; Xu, H.F. Fluidity of liquid phase in iron ores during sintering. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2011, 27, 291–293. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.Y.; Zhang, J.L. Relationship between Slag Phase and Softening & Melting Properties of Cohesive Zone. ISIJ Int. 2023, 63, 1919–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Zheng, H.Y.; Gao, Q.J.; Shen, F.M. Three-segment control theory of MgO/Al2O3 ratio based on viscosity experiments and phase diagram analyses at 1500 °C. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2020, 27, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Chen, M.; Zhang, W.D.; Zhao, Z.X.; Evans, T.; Nguyen, A.V.; Zhao, B. Viscosity Model for Iron Blast Furnace Slags in SiO2-Al2O3-CaO-MgO System. Steel Res. Int. 2015, 86, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, T.; Sakai, H.; Kita, Y.; Shigeno, K. An Equation for Accurate Prediction of the Viscosities of Blast Furnace Type Slags from Chemical Composition. ISIJ Int. 2000, 40, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, T.; Sakai, H.; Kita, Y.; Murakami, K. Equation for estimating viscosities of industrial mold fluxes. High Temp. Mater. Process. 1999, 19, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, A.; Sahoo, S.K.; Mishra, B.; Mohanty, U.K. Viscosity of Industrial Blast Furnace Slag in Indian Scenario. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2018, 71, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, D.W.; Kou, M.Y.; Zhao, B.J. Viscosities of Iron Blast Furnace Slags. ISIJ Int. 2014, 54, 2025–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev, A.; Jak, E. Review of experimental data and modeling of the viscosities of fully liquid slags in the Al2O3-CaO-FeO-SiO2 system. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2001, 32, 1015–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev, A.; Hayes, P.C.; Jak, E. Development of a Quasi-chemical Viscosity Model for Fully Liquid Slags in the Al2O3-CaO-FeO-MgO-SiO2 System. Part 3. Summary of the Model Predictions for the Al2O3-CaO-MgO-SiO2 System and Its Sub-systems. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondratiev, A.; Hayes, P.C.; Jak, E. Development of a Quasi-chemical Viscosity Model for Fully Liquid Slags in the Al2O3-CaO-FeO-MgO-SiO2 System. The Experimental Data for the FeO-MgO-SiO2, CaO-FeO-MgO-SiO2 and Al2O3-CaO-FeO-MgO-SiO2 Systems at Iron Saturation. ISIJ Int. 2008, 48, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, M.; Jak, E. Development of a Quasi-chemical Viscosity Model for Fully Liquid Slags in the Al2O3-CaO-FeO-MgO-SiO2 System: The Revised Model to Incorporate Ferric Oxide. ISIJ Int. 2014, 54, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Zhang, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, X.D. Structurally-based viscosity model for multicomponent slag systems. Chin. J. Eng. 2020, 42, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.L.; Guo, M.; Wang, X.D.; Zhang, T.Z.; Zhang, M. Estimation model of viscosity based on modified (NBO/T) ratio. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2010, 32, 1542–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.G.; Yan, Z.M.; Pang, Z.D.; Jiang, Y.Y.; Ling, J.W.; Lu, X.W. Advances of measurement and calculation model of slag viscosity. Iron Steel 2020, 55, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Batchelor, G.K. The effect of Brownian motion on the bulk stress in a suspension of spherical particles. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 83, 97–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, E.J.; Leal, L.G. The effect of Brownian motion on the rheological properties of a suspension of non-spherical particles. J. Fluid Mech. 2006, 52, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.L.; Ma, M.S. A description of slag viscosity model and the prediction capability. China Nonferrous Metall. 2015, 44, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

| No. | w (CaO) | w (SiO2) | w (FeO) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64.29 | 35.71 | 0 | 1.8 |

| 2 | 51.43 | 28.57 | 20 | 1.8 |

| 3 | 38.57 | 21.43 | 40 | 1.8 |

| 4 | 25.71 | 14.29 | 60 | 1.8 |

| 5 | 12.85 | 7.15 | 80 | 1.8 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Correction Coefficient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| j | ||||||||

| 0 | 13.31 | 36.98 | −177.70 | 190.03 | n | 9.322 | ||

| 1 | 5.50 | 96.20 | 117.94 | −219.56 | 0.370 | |||

| 2 | −4.68 | −81.60 | −109.80 | 196.00 | 0.587 | |||

| 1 | 34.30 | −143.64 | 368.94 | −254.85 | 0.665 | |||

| 2 | −45.63 | 129.96 | −210.28 | 121.20 | 0.212 | |||

| Model Name | Expression | Scope of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Einstein | fsolid < 0.05 | |

| Roscoe-1 | fsolid < 0.73 | |

| Roscoe-2 | unrestricted | |

| Alex | fsolid < 0.49 | |

| Batchelor | unrestricted | |

| Monney | unrestricted |

| T/°C | w (FeO)/% | /Pa·s | f/% | 1/F | Viscosity/Pa·s | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roscoe-2 | Batchelor | Monney | |||||

| 1200 | 20 | 1.82 | 91.83 | 1/1.00 | 765.84 | 13.55 | 296.18 |

| 1200 | 40 | 1.82 | 94.22 | 1/1.00 | 588.50 | 13.32 | 271.74 |

| 1200 | 60 | 1.82 | 95.69 | 1/1.00 | 5815.62 | 14.74 | 460.13 |

| 1200 | 80 | 1.82 | 97.69 | 1/1.00 | 186,100.00 | 15.49 | 604.23 |

| 1240 | 20 | 1.07 | 91.05 | 1/1.00 | 77.99 | 6.65 | 80.55 |

| 1240 | 40 | 1.07 | 94.36 | 1/3.20 | 123.02 | 7.02 | 102.82 |

| 1240 | 60 | 1.07 | 94.85 | 1/3.11 | 339.00 | 7.67 | 156.53 |

| 1240 | 80 | 1.07 | 96.33 | 1/1.60 | 1215.67 | 8.21 | 221.78 |

| 1280 | 20 | 0.37 | 62.38 | 1/1.82 | 5.12 | 1.65 | 7.84 |

| 1280 | 40 | 0.29 | 58.33 | 1/13.00 | 4.36 | 1.33 | 6.66 |

| 1280 | 60 | 0.29 | 72.66 | 1/10.91 | 9.41 | 1.60 | 12.80 |

| 1280 | 80 | 0.29 | 87.00 | 1/6.49 | 40.09 | 1.96 | 30.63 |

| 1320 | 20 | 0.37 | 61.63 | 1/4.11 | 5.05 | 1.62 | 7.74 |

| 1320 | 40 | 0.25 | 35.49 | 1/13.29 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.85 |

| 1320 | 60 | 0.19 | 11.98 | 1/14.71 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.26 |

| 1320 | 80 | 0.15 | 0.00 | 1/18.87 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.15 |

| T/°C | w (FeO)/% | /Pa·s | f/% | Pa·s | FC | FT | Relative Error/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1200 °C | 60 | 1.37 | 5 | 1.48 | 10.81 | 11.05 | 2.17 |

| 1200 °C | 80 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.75 | 13.52 | 12.93 | 4.56 |

| 1240 °C | 60 | 1.18 | 4 | 1.25 | 12.58 | 12.10 | 4.00 |

| 1240 °C | 80 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.59 | 14.15 | 13.05 | 8.43 |

| 1280 °C | 60 | 0.99 | 2 | 1.06 | 12.26 | 11.94 | 2.68 |

| 1280 °C | 80 | 0.47 | 0 | 0.47 | 14.69 | 13.67 | 7.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, K.; Zheng, H.; Gao, Q.; Shen, F. Investigation on the Viscosity and Fluidity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 Ternary Primary Slag in Cohesive Zone of Blast Furnace. Metals 2026, 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010035

Wang Q, Jiang X, Li Y, Fan K, Zheng H, Gao Q, Shen F. Investigation on the Viscosity and Fluidity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 Ternary Primary Slag in Cohesive Zone of Blast Furnace. Metals. 2026; 16(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qingyu, Xin Jiang, Yongqiang Li, Kai Fan, Haiyan Zheng, Qiangjian Gao, and Fengman Shen. 2026. "Investigation on the Viscosity and Fluidity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 Ternary Primary Slag in Cohesive Zone of Blast Furnace" Metals 16, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010035

APA StyleWang, Q., Jiang, X., Li, Y., Fan, K., Zheng, H., Gao, Q., & Shen, F. (2026). Investigation on the Viscosity and Fluidity of FeO-CaO-SiO2 Ternary Primary Slag in Cohesive Zone of Blast Furnace. Metals, 16(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/met16010035