A High-Performance Learning Particle Swarm Optimization Based on the Knowledge of Individuals for Large-Scale Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To reduce the influence of local extremum on the population during large-scale spatial search, this paper proposes that multiple elite individuals are used to refer to population updates and designs corresponding to population update strategy.

- (2)

- This paper proposes a novel approach of performing opposition-based learning on multiple elite individuals and individuals with poor fitness values. A synchronous opposition-based learning strategy for multiple elite and poor individuals is designed to help individuals quickly jump out of the poor search areas.

- (3)

- HPLPSO is proposed and its optimization performance is also verified in solving large-scale problems through experiments and case applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. PSO Improvement

2.2. PSO in Large-Scale Problems

3. Proposed HPLPSO

3.1. Strategy for Elite Individuals to Guide Population Updates

3.2. Synchronous Opposition-Based Learning Strategy for Elite and Poor Individuals

3.3. HPLPSO Based on Two Strategies

| Algorithm 1: Pseudo-code of the HPLPSO algorithm |

| 1. Initialize parameter values, individual velocity vi (i = 1…M) and position xi (i = 1…M) 2. Calculate fitnessi (i = 1…M) for the initial individual 3. Determine the best positions discovered by each individual so far pi (i = 1…M) 4. Determine the Celite used to guide later population updates by Equations (3) and (4) 5. while (t < T) 6. Calculate fitnessave (t) 7. Determine multiple elite and poor individuals in the current iteration population by Equations (5) and (6) 8. Opposition-based learning of multiple elite and poor individuals in the current iteration by Equation (7) and Equation (8), respectively 9. Update velocity vi (i = 1…M) and position xi (i = 1…M) based on Section 3.1 10. Calculate all individual fitness values 11. Update pi (i = 1…M) 12. Update Celite 13. t = t + 1 14. end while 15. Return Best individual position and its fitness value among the elite individuals |

4. Numerical Experiments

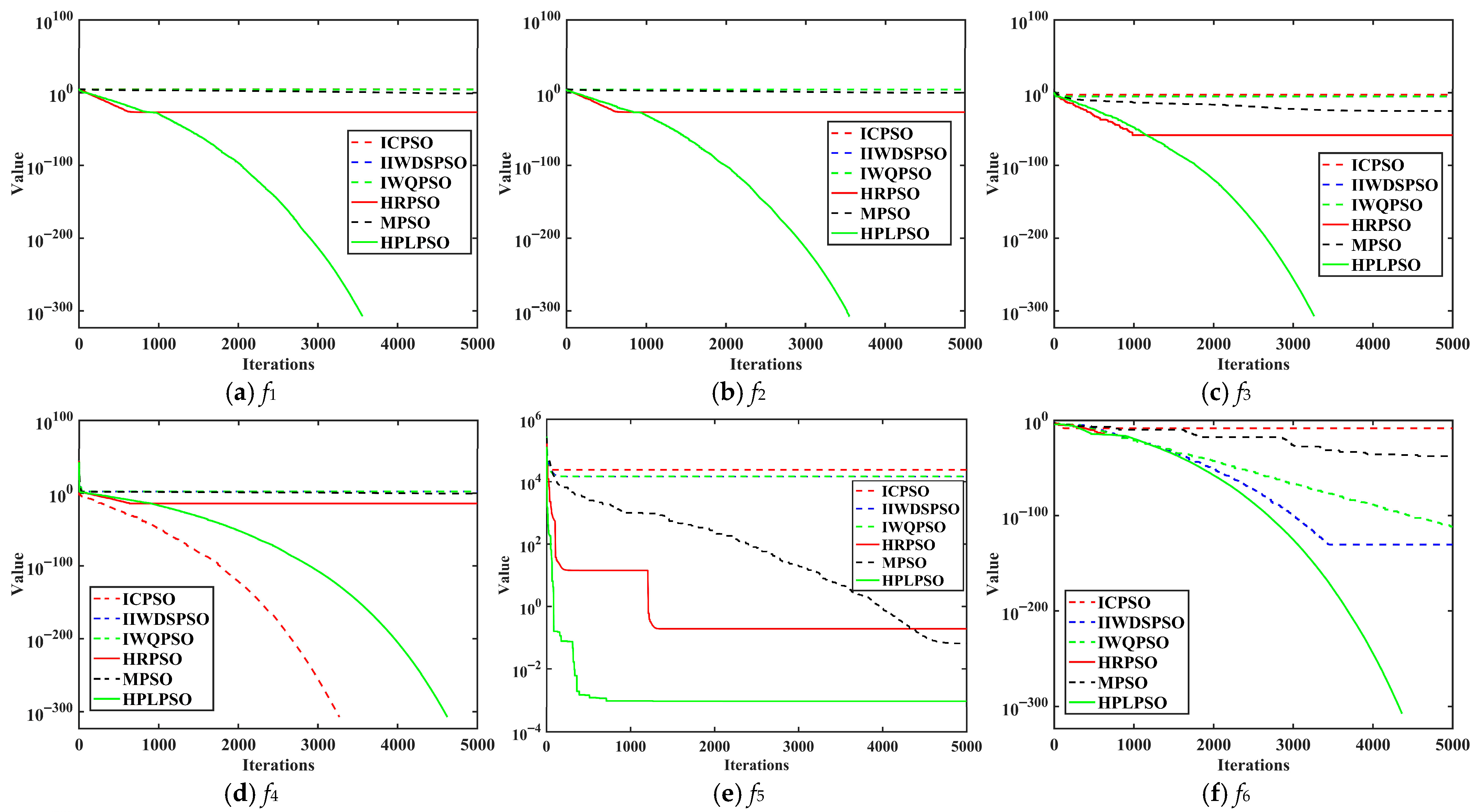

4.1. Dimension 100

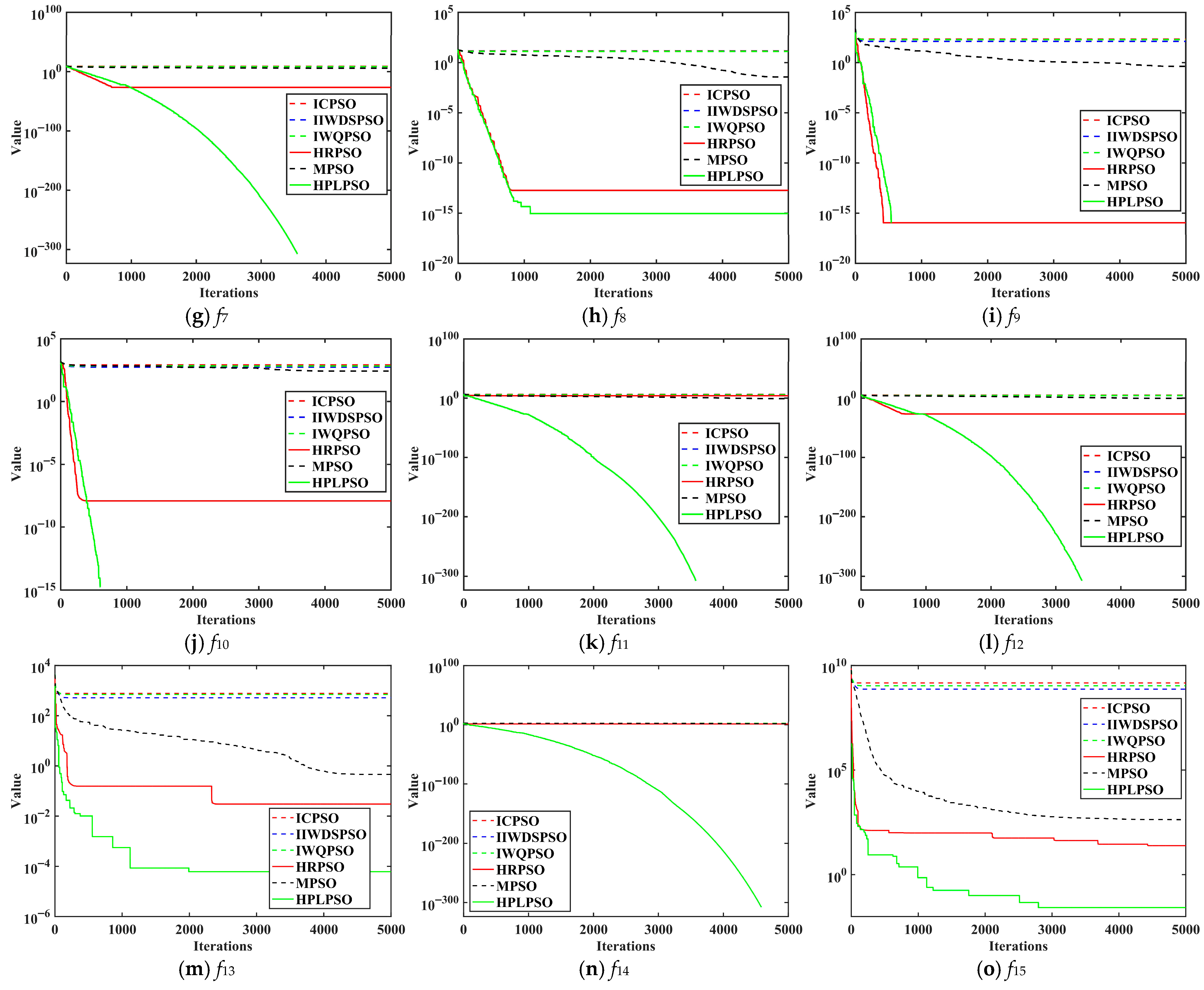

4.2. Dimensions 200, 500 and 1000

4.3. Stability Analysis of Obtaining Theoretical Optimal Value

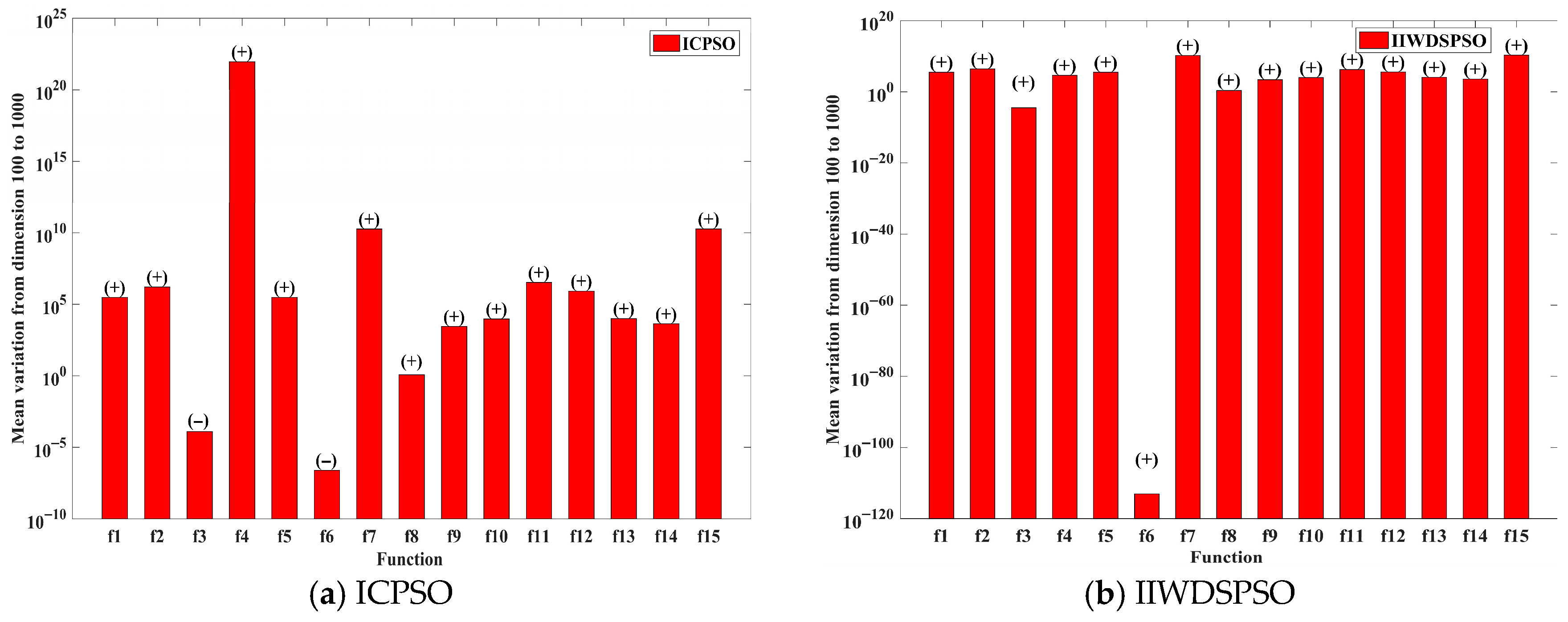

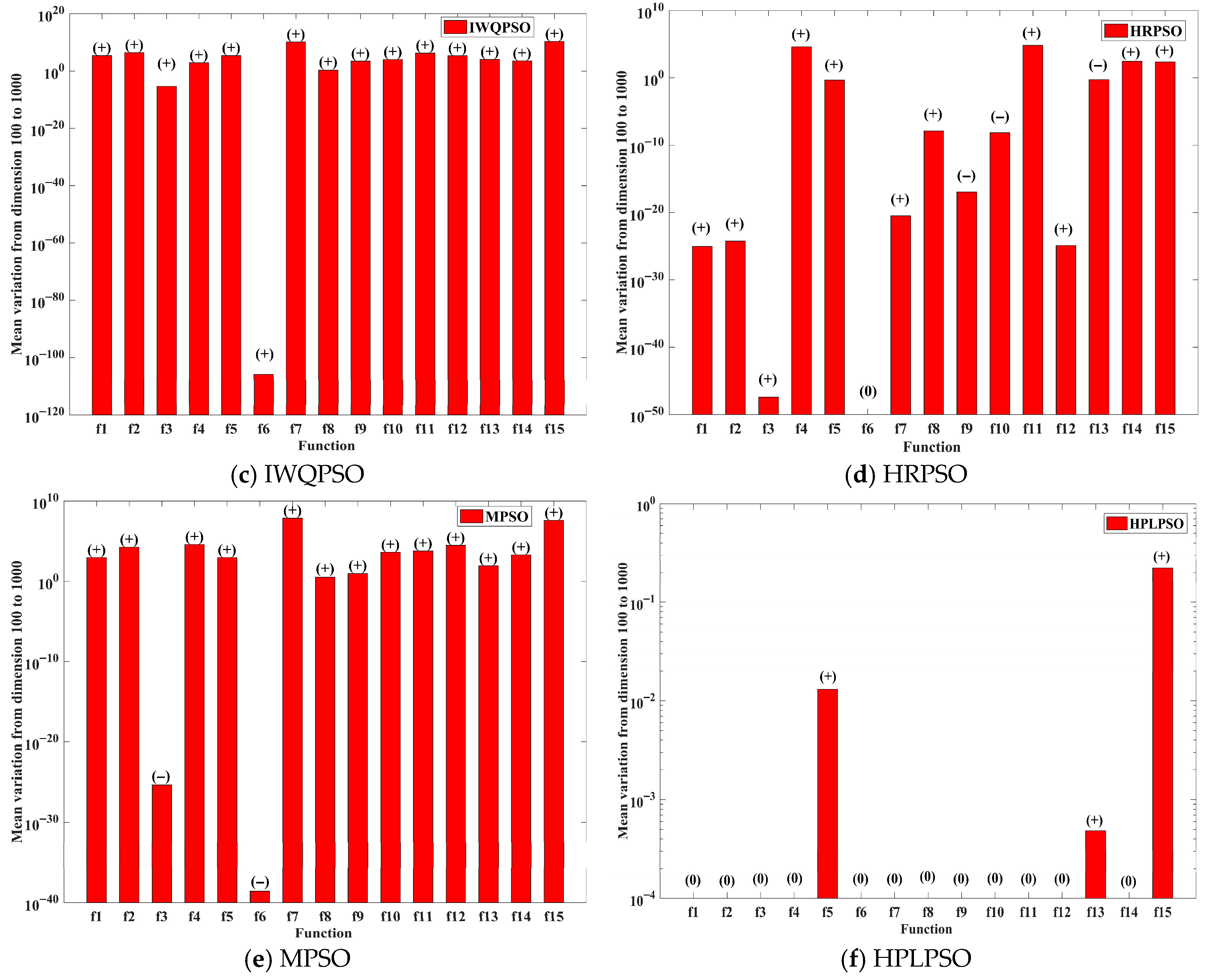

4.4. Performance Change Analysis of Six Algorithms with Increasing Dimensions

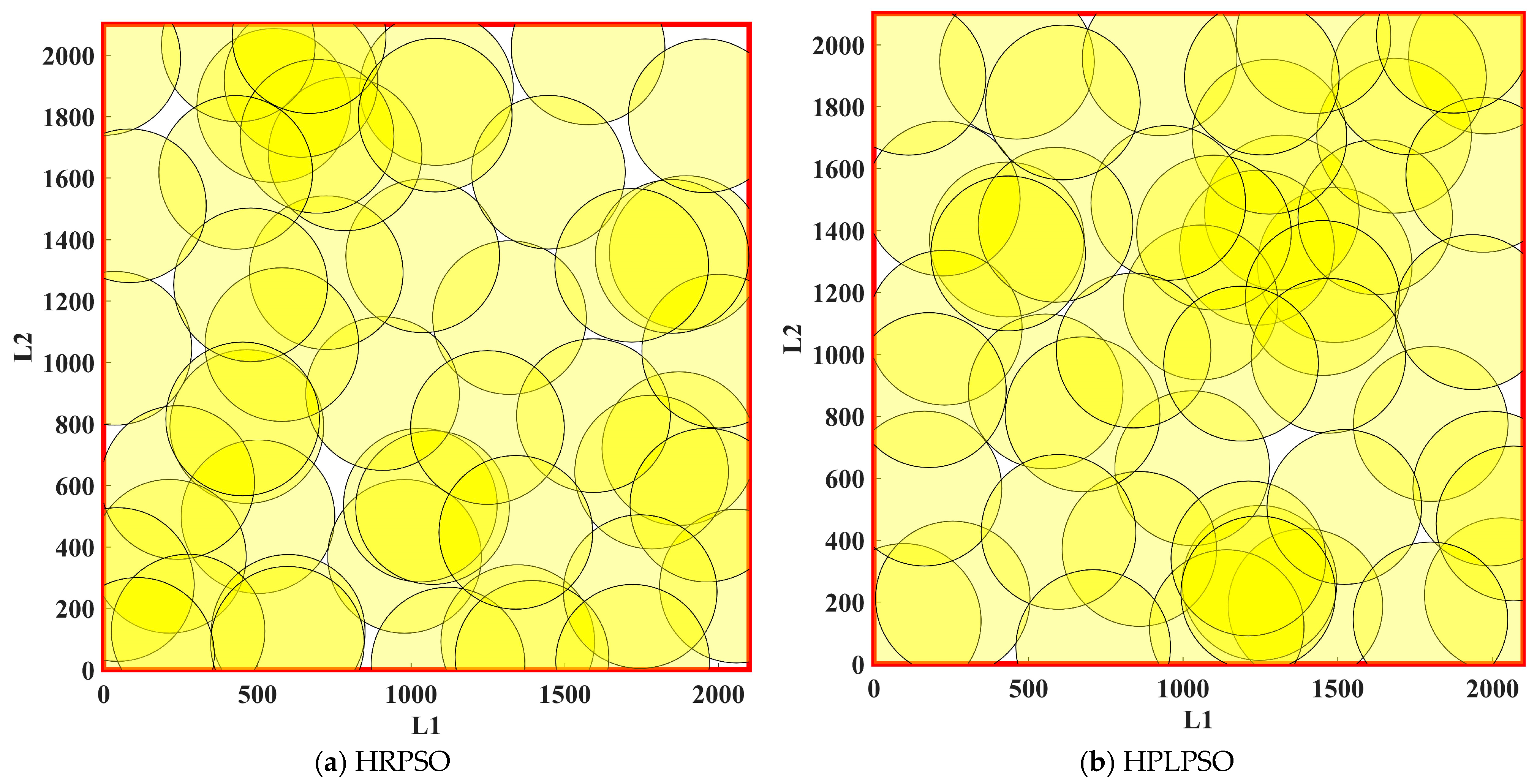

5. 5G Base Station Deployment Optimization Application

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Function | Indicator | ICPSO | IIWDSPSO | IWQPSO | HRPSO | MPSO | HPLPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f1 | Minimum | 4.0297 × 104 | 3.4417 × 104 | 2.7981 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.8726 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 5.4190 × 104 | 4.5487 × 104 | 3.9420 × 104 | 6.1508 × 10−27 | 8.1520 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 5.3564 × 103 | 7.2074 × 103 | 4.6405 × 103 | 1.0538 × 10−26 | 2.1816 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f2 | Minimum | 4.1497 × 104 | 5.3400 × 104 | 5.5820 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.1772 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 5.1557 × 104 | 6.7546 × 104 | 7.9162 × 104 | 1.0074 × 10−26 | 2.5628 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.6920 × 103 | 7.5803 × 103 | 1.0774 × 104 | 1.4311 × 10−26 | 3.8590 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f3 | Minimum | 2.3555 × 10−5 | 1.9791 × 10−7 | 1.0429 × 10−6 | 7.0821 × 10−220 | 2.5962 × 10−35 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.3228 × 10−3 | 3.1934 × 10−6 | 6.4852 × 10−6 | 1.2700 × 10−49 | 2.4739 × 10−32 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.4087 × 10−3 | 3.9286 × 10−6 | 6.1184 × 10−6 | 6.9561 × 10−49 | 3.9578 × 10−32 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f4 | Minimum | 2.5226 × 102 | 2.5389 × 102 | 2.8034 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 6.1139 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.8987 × 102 | 3.5359 × 102 | 3.6128 × 102 | 6.0975 × 10−15 | 2.6925 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.4028 × 101 | 4.1574 × 101 | 5.2945 × 101 | 7.7860 × 10−15 | 3.1046 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f5 | Minimum | 4.1216 × 104 | 3.5442 × 104 | 2.7387 × 104 | 3.8783 × 10−4 | 5.7137 × 10−1 | 1.6372 × 10−5 |

| Mean | 5.3779 × 104 | 4.4756 × 104 | 3.9349 × 104 | 1.8719 × 10−1 | 8.0927 × 10−1 | 2.7297 × 10−3 | |

| SD | 4.7378 × 103 | 5.5925 × 103 | 5.8046 × 103 | 4.9175 × 10−1 | 1.2897 × 10−1 | 3.0115 × 10−3 | |

| f6 | Minimum | 4.6498 × 10−148 | 9.8478 × 10−262 | 5.3177 × 10−117 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.4867 × 10−116 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.7200 × 10−7 | 7.9778 × 10−146 | 7.0446 × 10−109 | 0.0000 × 100 | 7.9406 × 10−45 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 5.6824 × 10−7 | 4.3696 × 10−145 | 3.7643 × 10−108 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.3493 × 10−44 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f7 | Minimum | 1.3754 × 109 | 5.3688 × 108 | 7.7907 × 108 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.1779 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.1405 × 109 | 9.3784 × 108 | 1.1783 × 109 | 1.8738 × 10−26 | 2.2797 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.0627 × 108 | 2.2276 × 108 | 3.2041 × 108 | 1.0147 × 10−25 | 5.6454 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f8 | Minimum | 1.3589 × 101 | 1.3364 × 101 | 1.3099 × 101 | 3.9968 × 10−14 | 8.2476 × 10−2 | 8.8818 × 10−16 |

| Mean | 1.4842 × 101 | 1.4248 × 101 | 1.4017 × 101 | 5.9419 × 10−13 | 1.0592 × 10−1 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | |

| SD | 3.9600 × 10−1 | 3.4765 × 10−1 | 5.4625 × 10−1 | 7.6016 × 10−13 | 2.2673 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f9 | Minimum | 3.6609 × 102 | 2.9137 × 102 | 4.1791 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.0503 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 4.9299 × 102 | 3.9658 × 102 | 5.2689 × 102 | 1.1842 × 10−16 | 8.8830 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.4594 × 101 | 5.4337 × 101 | 5.6726 × 101 | 4.3921 × 10−16 | 3.5043 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f10 | Minimum | 1.6903 × 103 | 1.4103 × 103 | 1.5238 × 103 | 5.0781 × 10−11 | 4.1769 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.8090 × 103 | 1.5435 × 103 | 1.7412 × 103 | 1.1622 × 10−8 | 5.8503 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 5.9645 × 101 | 6.9431 × 101 | 1.1355 × 102 | 3.0609 × 10−8 | 1.1632 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f11 | Minimum | 2.2844 × 105 | 1.9806 × 105 | 1.7804 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 6.9212 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.4402 × 106 | 4.4532 × 105 | 5.1852 × 105 | 6.5976 × 104 | 1.0449 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 3.8851 × 106 | 1.5319 × 105 | 4.7123 × 105 | 1.3997 × 105 | 1.7616 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f12 | Minimum | 8.6170 × 104 | 3.7784 × 104 | 3.4288 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.0973 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.5802 × 105 | 5.6198 × 104 | 4.6781 × 104 | 5.7643 × 10−27 | 3.9569 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 6.0023 × 104 | 1.3090 × 104 | 6.9351 × 103 | 1.0145 × 10−26 | 6.4178 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f13 | Minimum | 1.6157 × 103 | 1.4827 × 103 | 1.6058 × 103 | 1.5640 × 10−5 | 1.0447 × 100 | 3.8320 × 10−6 |

| Mean | 1.8149 × 103 | 1.7051 × 103 | 1.8952 × 103 | 6.4201 × 10−3 | 1.9009 × 100 | 1.3925 × 10−4 | |

| SD | 1.0964 × 102 | 1.1592 × 102 | 1.6404 × 102 | 1.1432 × 10−2 | 6.1636 × 10−1 | 1.2488 × 10−4 | |

| f14 | Minimum | 6.7192 × 102 | 5.1453 × 102 | 5.0537 × 102 | 1.0267 × 10−1 | 6.9890 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 7.7649 × 102 | 6.1534 × 102 | 6.0423 × 102 | 4.3151 × 101 | 1.8248 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 5.1693 × 101 | 5.2348 × 101 | 5.4742 × 101 | 4.6386 × 101 | 6.0666 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f15 | Minimum | 3.0444 × 109 | 1.9030 × 109 | 2.4388 × 109 | 4.8538 × 10−1 | 5.2777 × 102 | 3.4018 × 10−4 |

| Mean | 3.3629 × 109 | 2.4991 × 109 | 2.9446 × 109 | 4.3206 × 101 | 1.0541 × 103 | 4.5509 × 10−2 | |

| SD | 1.8523 × 108 | 1.8840 × 108 | 1.8971 × 108 | 4.5285 × 101 | 9.1910 × 102 | 4.9955 × 10−2 |

| Function | Indicator | ICPSO | IIWDSPSO | IWQPSO | HRPSO | MPSO | HPLPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f1 | Minimum | 1.3617 × 105 | 1.1899 × 105 | 1.0013 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.2822 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.5822 × 105 | 1.4888 × 105 | 1.1800 × 105 | 2.8969 × 10−26 | 3.1911 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.1215 × 104 | 1.1287 × 104 | 7.9957 × 103 | 4.4345 × 10−26 | 4.3221 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f2 | Minimum | 3.3451 × 105 | 4.8581 × 105 | 4.9173 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.6430 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 3.9215 × 105 | 6.0097 × 105 | 5.6835 × 105 | 8.7055 × 10−26 | 6.8689 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 3.3099 × 104 | 5.1591 × 104 | 5.1014 × 104 | 1.4838 × 10−25 | 2.5284 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f3 | Minimum | 3.0330 × 10−5 | 1.4853 × 10−7 | 7.7417 × 10−7 | 3.4918 × 10−251 | 3.0304 × 10−42 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.7133 × 10−3 | 5.8049 × 10−6 | 1.7049 × 10−5 | 1.0381 × 10−60 | 1.0482 × 10−35 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.4376 × 10−3 | 6.2711 × 10−6 | 2.0276 × 10−5 | 5.6852 × 10−60 | 3.9829 × 10−35 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f4 | Minimum | 6.6340 × 102 | 9.4230 × 102 | 8.3737 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 7.3172 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 7.6032 × 102 | 1.0430 × 103 | 9.4841 × 102 | 3.6619 × 10−14 | 2.0643 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 5.9861 × 101 | 5.2136 × 101 | 4.4583 × 101 | 3.6220 × 10−14 | 7.7742 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f5 | Minimum | 1.3558 × 105 | 1.2192 × 105 | 9.5723 × 104 | 2.4679 × 10−3 | 2.7850 × 101 | 2.0168 × 10−6 |

| Mean | 1.5730 × 105 | 1.4899 × 105 | 1.1785 × 105 | 2.5039 × 10−1 | 3.4414 × 101 | 7.6894 × 10−3 | |

| SD | 1.1919 × 104 | 1.5402 × 104 | 8.7414 × 103 | 4.3068 × 10−1 | 3.8462 × 100 | 1.1080 × 10−2 | |

| f6 | Minimum | 2.2392 × 10−255 | 3.8412 × 10−261 | 5.8765 × 10−117 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.4862 × 10−159 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.2916 × 10−8 | 1.3510 × 10−123 | 3.9903 × 10−110 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.2540 × 10−50 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.2527 × 10−8 | 7.3998 × 10−123 | 1.5012 × 10−109 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.2346 × 10−49 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f7 | Minimum | 6.2242 × 109 | 3.8444 × 109 | 3.8482 × 109 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.4643 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 8.1124 × 109 | 5.2923 × 109 | 5.3786 × 109 | 6.4970 × 10−22 | 1.3214 × 107 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.0889 × 109 | 1.0024 × 109 | 1.1629 × 109 | 2.0035 × 10−21 | 2.8302 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f8 | Minimum | 1.4786 × 101 | 1.4687 × 101 | 1.4200 × 101 | 6.8390 × 10−14 | 9.6859 × 10−1 | 8.8818 × 10−16 |

| Mean | 1.5264 × 101 | 1.5383 × 101 | 1.4787 × 101 | 2.6649 × 10−12 | 1.2315 × 100 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | |

| SD | 2.3126 × 10−1 | 3.5291 × 10−1 | 3.1416 × 10−1 | 4.7465 × 10−12 | 1.3344 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f9 | Minimum | 1.2297 × 103 | 1.2043 × 103 | 1.2733 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.2225 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.4296 × 103 | 1.3412 × 103 | 1.5069 × 103 | 1.3053 × 10−12 | 1.3052 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.0570 × 102 | 7.8702 × 101 | 1.1109 × 102 | 7.1491 × 10−12 | 3.8217 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f10 | Minimum | 4.6972 × 103 | 4.5338 × 103 | 4.7173 × 103 | 3.9861 × 10−11 | 1.3313 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 4.9449 × 103 | 4.8262 × 103 | 5.0656 × 103 | 2.7767 × 10−9 | 1.7664 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 9.7280 × 101 | 1.2618 × 102 | 1.7939 × 102 | 6.8560 × 10−9 | 2.6174 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f11 | Minimum | 5.7039 × 105 | 6.3400 × 105 | 6.7734 × 105 | 3.4354 × 10−6 | 3.0891 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.3060 × 106 | 1.1151 × 106 | 1.0122 × 106 | 3.0162 × 105 | 3.9351 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 6.8304 × 106 | 2.7614 × 105 | 2.0724 × 105 | 7.3832 × 105 | 6.0538 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f12 | Minimum | 2.1392 × 105 | 1.2655 × 105 | 9.2178 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.1342 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 4.4722 × 105 | 1.8216 × 105 | 1.2679 × 105 | 2.8259 × 10−26 | 4.2410 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.7742 × 105 | 3.2732 × 104 | 1.9701 × 104 | 4.1808 × 10−26 | 6.2363 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f13 | Minimum | 4.5471 × 103 | 5.1603 × 103 | 5.2854 × 103 | 1.2334 × 10−5 | 1.0824 × 101 | 5.2003 × 10−6 |

| Mean | 5.2788 × 103 | 5.5692 × 103 | 5.7743 × 103 | 4.3901 × 10−2 | 1.3620 × 101 | 3.5655 × 10−4 | |

| SD | 2.9997 × 102 | 2.4923 × 102 | 2.7680 × 102 | 1.3626 × 10−1 | 1.3281 × 100 | 3.9324 × 10−4 | |

| f14 | Minimum | 2.0727 × 103 | 1.7952 × 103 | 1.6142 × 103 | 1.5114 × 10−2 | 3.9472 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.2232 × 103 | 2.0123 × 103 | 1.8277 × 103 | 1.5057 × 102 | 8.3830 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 8.4496 × 101 | 1.3297 × 102 | 1.1079 × 102 | 1.7094 × 102 | 2.7119 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f15 | Minimum | 8.9720 × 109 | 8.1270 × 109 | 8.4956 × 109 | 2.9754 × 10−3 | 4.4331 × 103 | 1.3367 × 10−3 |

| Mean | 9.6603 × 109 | 8.9428 × 109 | 9.1331 × 109 | 8.6219 × 101 | 6.1594 × 103 | 1.0665 × 10−1 | |

| SD | 3.7057 × 108 | 4.3379 × 108 | 4.0604 × 108 | 1.0650 × 102 | 1.1364 × 103 | 1.0014 × 10−1 |

| Function | Indicator | ICPSO | IIWDSPSO | IWQPSO | HRPSO | MPSO | HPLPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f1 | Minimum | 2.9540 × 105 | 2.8271 × 105 | 2.0454 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.1192 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 3.2795 × 105 | 3.2529 × 105 | 2.5525 × 105 | 9.7907 × 10−26 | 9.4759 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.8229 × 104 | 2.1050 × 104 | 1.8248 × 104 | 1.8538 × 10−25 | 8.9128 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f2 | Minimum | 1.4255 × 106 | 2.3546 × 106 | 2.3831 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.1904 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.6509 × 106 | 2.6763 × 106 | 2.6007 × 106 | 6.0668 × 10−25 | 1.8470 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.0542 × 105 | 1.3375 × 105 | 1.3208 × 105 | 9.7629 × 10−25 | 3.2878 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f3 | Minimum | 3.6544 × 10−5 | 5.2990 × 10−7 | 1.0619 × 10−6 | 5.1529 × 10−231 | 4.1656 × 10−39 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.2835 × 10−3 | 3.4224 × 10−5 | 1.4559 × 10−5 | 3.7464 × 10−48 | 6.1014 × 10−34 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.3303 × 10−3 | 7.6936 × 10−5 | 2.7172 × 10−5 | 2.0520 × 10−47 | 1.9867 × 10−33 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f4 | Minimum | 1.2250 × 103 | 1.3708 × 103 | 8.3737 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.2057 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 9.0277 × 1021 | 4.2054 × 104 | 9.4841 × 102 | 4.1506 × 104 | 3.9819 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.9447 × 1022 | 3.1388 × 104 | 4.4583 × 101 | 3.2121 × 104 | 3.2034 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f5 | Minimum | 2.9657 × 105 | 2.7302 × 105 | 2.3251 × 105 | 1.1387 × 10−3 | 7.9344 × 102 | 2.1923 × 10−4 |

| Mean | 3.3000 × 105 | 3.2513 × 105 | 2.5833 × 105 | 6.5771 × 10−1 | 9.3025 × 102 | 1.3942 × 10−2 | |

| SD | 1.7559 × 104 | 2.2347 × 104 | 1.5832 × 104 | 1.0386 × 100 | 8.2377 × 101 | 1.9242 × 10−2 | |

| f6 | Minimum | 1.3405 × 10−80 | 1.8197 × 10−224 | 5.1048 × 10−116 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.5865 × 10−186 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 8.8966 × 10−9 | 8.7109 × 10−114 | 1.3882 × 10−106 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.0443 × 10−52 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.6367 × 10−8 | 4.7712 × 10−113 | 7.4572 × 10−106 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.5938 × 10−51 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f7 | Minimum | 1.5369 × 1010 | 1.2945 × 1010 | 1.0927 × 1010 | 0.0000 × 100 | 5.4319 × 107 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.9001 × 1010 | 1.5679 × 1010 | 1.3545 × 1010 | 3.2089 × 10−21 | 7.4270 × 107 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.0619 × 109 | 1.6789 × 109 | 1.6399 × 109 | 5.3257 × 10−21 | 1.2995 × 107 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f8 | Minimum | 1.4853 × 101 | 1.5349 × 101 | 1.4472 × 101 | 1.4300 × 10−13 | 3.0835 × 100 | 8.8818 × 10−16 |

| Mean | 1.5391 × 101 | 1.5644 × 101 | 1.4941 × 101 | 1.2656 × 10−8 | 3.2837 × 100 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | |

| SD | 2.2673 × 10−1 | 1.9947 × 10−1 | 2.7326 × 10−1 | 6.9052 × 10−8 | 1.0852 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f9 | Minimum | 2.6654 × 103 | 2.5926 × 103 | 2.9147 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | 7.7545 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.9548 × 103 | 2.8508 × 103 | 3.3837 × 103 | 1.4803 × 10−17 | 9.5230 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.6381 × 102 | 1.7000 × 102 | 2.2212 × 102 | 6.3432 × 10−17 | 7.3750 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f10 | Minimum | 1.0075 × 104 | 1.0139 × 104 | 1.0483 × 104 | 2.3130 × 10−11 | 3.5558 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.0379 × 104 | 1.0831 × 104 | 1.1000 × 104 | 4.8138 × 10−9 | 4.3903 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.6316 × 102 | 3.1183 × 102 | 2.9411 × 102 | 1.0488 × 10−8 | 7.7341 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f11 | Minimum | 1.0170 × 106 | 1.2346 × 106 | 1.1123 × 106 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.1826 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 4.6637 × 106 | 2.1380 × 106 | 2.0596 × 106 | 8.5539 × 104 | 6.1428 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 9.4867 × 106 | 4.8288 × 105 | 4.6796 × 105 | 2.1970 × 105 | 1.0237 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f12 | Minimum | 4.7922 × 105 | 2.6576 × 105 | 1.5585 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.8221 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 8.9141 × 105 | 4.2382 × 105 | 2.4689 × 105 | 1.2397 × 10−25 | 3.0788 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.2368 × 105 | 9.8986 × 104 | 4.0934 × 104 | 1.5350 × 10−25 | 8.6278 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f13 | Minimum | 1.0090 × 104 | 1.1497 × 104 | 1.1533 × 104 | 6.5023 × 10−4 | 8.1053 × 101 | 1.4340 × 10−5 |

| Mean | 1.0912 × 104 | 1.2656 × 104 | 1.2429 × 104 | 3.2252 × 10−2 | 8.5025 × 101 | 5.4160 × 10−4 | |

| SD | 3.7131 × 102 | 5.1532 × 102 | 4.2731 × 102 | 3.2202 × 10−2 | 3.2350 × 100 | 6.2737 × 10−4 | |

| f14 | Minimum | 4.2307 × 103 | 4.0227 × 103 | 3.9026 × 103 | 4.5971 × 10−1 | 1.3283 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 4.6162 × 103 | 4.4627 × 103 | 4.1006 × 103 | 3.1388 × 102 | 2.0946 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.4452 × 102 | 2.2820 × 102 | 1.5627 × 102 | 3.2284 × 102 | 4.5626 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f15 | Minimum | 1.8803 × 1010 | 1.6743 × 1010 | 1.8776 × 1010 | 2.5459 × 10−1 | 3.0104 × 107 | 1.3149 × 10−2 |

| Mean | 2.0190 × 1010 | 1.9867 × 1010 | 1.9652 × 1010 | 2.6315 × 102 | 3.8167 × 107 | 2.4985 × 10−1 | |

| SD | 5.2031 × 108 | 9.7205 × 108 | 6.3024 × 108 | 2.9957 × 102 | 3.8032 × 106 | 2.2250 × 10−1 |

References

- Bilandi, N.; Verma, H.; Dhir, R. hPSO-SA: Hybrid particle swarm optimization-simulated annealing algorithm for relay node selection in wireless body area networks. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 1410–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, D.; Gao, X. A fast hybrid feature selection based on correlation-guided clustering and particle swarm optimization for high-dimensional data. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 52, 9573–9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Qi, L.; Liu, X. Modeling and optimization of robot welding process parameters based on improved SVM-PSO. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Liu, A.; Wang, J.; Kong, X. An improved fault-tolerant cultural-PSO with probability for multi-AGV path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahnehkolaei, S.; Alfi, A.; Machado, J. Analytical stability analysis of the fractional-order particle swarm optimization algorithm. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 155, 111658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Li, G.; Wu, G.; Hou, M.; Jia, Q. Cooperative task allocation for multi heterogeneous aerial vehicles using particle swarm optimization algorithm and entropy weight method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 148, 110918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Gebreyesus, G.D.; Fujimura, S. Day-ahead multi-modal demand side management in microgrid via two-stage improved ring-topology particle swarm optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Houssein, E. Particle swarm optimization for hybrid mutant slime mold: An efficient algorithm for solving the hyperparameters of adaptive Grey-Markov modified model. Inf. Sci. 2025, 689, 121417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Nobile, M.S.; Cazzaniga, P.; Besozzi, D.; Colombo, R.; Mauri, G.; Pasi, G. Fuzzy Self-Tuning PSO: A settings-free algorithm for global optimization. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2018, 39, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Jin, C. Improved particle swarm optimization for selection of shield tunneling parameter values. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2019, 118, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.D.; Hou, G.Y.; Yang, L.; Huang, X.J. Selection of shield construction parameters in specific sections based on e-SVR and improved particle swarm optimization algorithm. China Mech. Eng. 2022, 33, 3007–3014. [Google Scholar]

- Bangyal, W.; Nisar, K.; Soomro, T.; Ibrahim, A.; Mallah, G.; Hassan, N.; Rehman, N. An improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for data classification. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, T.; Li, J.; Lu, G. Parameter estimation of multivariable Wiener nonlinear systems by the improved particle swarm optimization and coupling identification. Inf. Sci. 2024, 661, 120192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Liu, S.; Jiao, H.; Qin, C. Particle swarm optimization with search operator of artificial bee colony algorithm. Control. Decis. 2012, 27, 833–838. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, J.; Yin, C. A support vector machine based on an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm and its application. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2016, 37, 1728–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Xiao, J.; Yang, Y.; Liang, J.; Tao, L. Particle swarm optimizer with crossover operation. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2018, 70, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yao, S. Research on photovoltaic MPPT based on mutation strategy PSO algorithm. Modul. Mach. Tool Autom. Manuf. Tech. 2022, 2022, 151–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Muthusamy, P.; Jerald, M. A hybrid framework for improved weighted quantum particle swarm optimization and fast mask recurrent CNN to enhance phishing-URL prediction performance. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Liang, C.D.; Lu, M. Optimal scheduling of electric vehicle ordered charging and discharging based on improved gravitational search and particle swarm optimization algorithm. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 157, 109766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Guo, G.; Chen, S.; Qiang, Y.; Liu, J. Energy-efficient data collection from UAV in WSNs based on improved PSO algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 35762–35774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Li, B. Multi-strategy ensemble particle swarm optimization for dynamic optimization. Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 3096–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, P. An adaptive multi-strategy behavior particle swarm optimization algorithm. Control. Decis. 2020, 35, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Asghari, K.; Masdari, M.; Gharehchopogh, F.; Saneifard, R. Multi-swarm and chaotic whale-particle swarm optimization algorithm with a selection method based on roulette wheel. Expert Syst. 2021, 38, 12779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, W.; Houssein, E. An adaptive snow ablation-inspired particle swarm optimization with its application in geometric optimization. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Sun, L.; Tan, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, C. Cooperative hierarchical PSO with two stage variable interaction reconstruction for large scale optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2017, 47, 2809–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Liu, R.; Yu, K.; Qu, B. Dynamic multi-swarm particle swarm optimization with cooperative coevolution for large scale global optimization. J. Softw. 2018, 29, 2595–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Yu, W.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gu, T.; Zhang, J. Dynamic group learning distributed particle swarm optimization for large-scale optimization and its application in cloud workflow scheduling. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 2715–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousavirad, S.; Rahnamayan, S. CenPSO: A novel center-based particle swarm optimization algorithm for large-scale optimization. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020; pp. 2066–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Kwong, S.; Jin, H.; Zhang, J. Adaptive granularity learning distributed particle swarm optimization for large-scale optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 1175–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hao, K.; Huang, B.; Zhu, X. Adaptive niching particle swarm optimization with local search for multimodal optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 133, 109923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Oversampling framework based on sample subspace optimization with accelerated binary particle swarm optimization for imbalanced classification. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 162, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Huang, M.; Liang, X.; Jiao, X. An improved chaotic particle swarm optimization algorithm with improved inertia weight. J. Dalian Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 41, 102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Z.; Li, M.; Cao, S.; Liu, C. A whale optimization algorithm based on hybrid reverse learning strategy. Comput. Eng. Sci. 2022, 44, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Bao, F.; Chi, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, P. Particle swarm optimization with adaptive learning strategy. Knowl. Based Syst. 2020, 196, 105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Kang, Q.; Cheng, J. Differential mutation and novel social learning particle swarm optimization algorithm. Inf. Sci. 2018, 480, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Cloud computing resource scheduling based on improved quantum particle swarm optimization algorithm. J. Nanjing Univ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 40, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Ding, L.; He, R. PSO-based Elman neural network model for predictive control of air chamber pressure in slurry shield tunneling under Yangtze River. Autom. Constr. 2013, 36, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Function | Search Space | Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 2 | [−10,10] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 3 | [−1,1] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 4 | [−10,10] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 5 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 6 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 7 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 8 | [−32,32] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 9 | [−600,600] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 10 | [−5.12,5.12] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 11 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 12 | [−100,100] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 13 | [−10,15] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 14 | [−50,50] | 100/200/500/1000 | |

| 15 | [−10,50] | 100/200/500/1000 |

| Algorithm | Parameter and Value |

|---|---|

| ICPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, variance critical value ε = 0.0001, ωmax = 0.9 and ωmin = 0.4 |

| IIWDSPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, ωmax = 0.9, ωmin = 0.4 |

| HRPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, ωmax = 0.9, ωmin = 0.4 |

| IWQPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, α = 0.001, ω = 0.9 |

| MPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, ωmax = 0.9, ωmin = 0.4, mutation probability = 0.6 |

| HPLPSO | T = 5000, M = 50, c1 = c2 = 0.1, j = 10 (according to T), ωmax = 0.9, ωmin = 0.4 |

| Function | Indicator | ICPSO | IIWDSPSO | IWQPSO | HRPSO | MPSO | HPLPSO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f1 | Minimum | 1.7513 × 104 | 9.9533 × 103 | 8.7169 × 103 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.7714 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.3555 × 104 | 1.4021 × 104 | 1.4443 × 104 | 1.1326 × 10−27 | 6.7620 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.9355 × 103 | 2.7239 × 103 | 2.6879 × 103 | 2.2021 × 10−27 | 1.9948 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f2 | Minimum | 7.5088 × 103 | 5.4491 × 103 | 1.1223 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.3063 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.0999 × 104 | 1.0253 × 104 | 1.3934 × 104 | 9.3992 × 1028 | 7.8452 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 1.3028 × 103 | 1.9945 × 103 | 2.0602 × 103 | 2.0780 × 10−27 | 1.3252 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f3 | Minimum | 5.0922 × 10−5 | 1.2775 × 10−7 | 6.9402 × 10−7 | 3.3456 × 10−282 | 6.4938 × 10−28 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.4100 × 10−3 | 3.0676 × 10−6 | 9.9950 × 10−6 | 2.4307 × 10−57 | 4.7819 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.1920 × 10−3 | 2.5330 × 10−6 | 1.1879 × 10−5 | 1.3309 × 10−56 | 7.8184 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f4 | Minimum | 0.0000 × 100 | 9.6208 × 101 | 1.0526 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.2973 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.3155 × 102 | 1.4467 × 102 | 4.5019 × 10−15 | 1.8028 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.8290 × 101 | 3.1411 × 101 | 7.2779 × 10−15 | 2.2002 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f5 | Minimum | 1.7697 × 104 | 1.0084 × 104 | 9.6906 × 103 | 3.8796 × 10−5 | 3.8005 × 10−2 | 1.3167 × 10−6 |

| Mean | 2.3523 × 104 | 1.4345 × 104 | 1.4716 × 104 | 1.7458 × 10−1 | 6.5010 × 10−2 | 8.7372 × 10−4 | |

| SD | 2.9547 × 103 | 2.6668 × 103 | 2.7361 × 103 | 7.2496 × 10−1 | 2.2280 × 10−2 | 1.1115 × 10−3 | |

| f6 | Minimum | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.9361 × 10−262 | 2.4334 × 10−117 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.2998 × 10−76 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.5030 × 10−7 | 9.4984 × 10−133 | 3.7416 × 10−112 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.6175 × 10−39 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 9.5818 × 10−7 | 5.2025 × 10−132 | 1.5907 × 10−111 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.0923 × 10−38 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f7 | Minimum | 4.5410 × 108 | 7.7807 × 107 | 1.2661 × 108 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.6507 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 8.6958 × 108 | 1.9058 × 108 | 2.6365 × 108 | 1.9936 × 10−27 | 6.2627 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 3.0020 × 108 | 6.6627 × 107 | 9.9451 × 107 | 1.0130 × 10−26 | 2.5102 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f8 | Minimum | 1.2998 × 101 | 1.2534 × 101 | 1.1433 × 101 | 2.2204 × 10−14 | 2.8085 × 10−2 | 8.8818 × 10−16 |

| Mean | 1.4219 × 101 | 1.3323 × 101 | 1.2886 × 101 | 1.8527 × 10−13 | 3.5691 × 10−2 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | |

| SD | 4.4341 × 10−1 | 5.5417 × 10−1 | 8.0146 × 10−1 | 1.1604 × 10−13 | 4.6858 × 10−3 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f9 | Minimum | 1.5965 × 102 | 8.8168 × 101 | 1.2588 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.8456 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 2.1060 × 102 | 1.2544 × 102 | 1.9250 × 102 | 2.5905 × 10−17 | 4.1438 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.8763 × 101 | 2.4017 × 101 | 3.2640 × 101 | 7.5374 × 10−17 | 8.0106 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f10 | Minimum | 6.8354 × 102 | 4.7656 × 102 | 5.5833 × 102 | 5.8842 × 10−11 | 1.8873 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 8.1287 × 102 | 5.5010 × 102 | 6.6587 × 102 | 1.1844 × 10−8 | 2.6274 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 4.7896 × 101 | 4.8178 × 101 | 6.1698 × 101 | 2.6709 × 10−8 | 3.4349 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f11 | Minimum | 1.0310 × 105 | 8.6993 × 104 | 9.2270 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.9837 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 1.3315 × 106 | 1.9725 × 105 | 2.0374 × 105 | 1.7267 × 104 | 9.3048 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 3.5984 × 106 | 6.4806 × 104 | 5.2324 × 104 | 4.4518 × 104 | 2.9254 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f12 | Minimum | 3.4347 × 104 | 1.4216 × 104 | 1.3585 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.7687 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 6.2876 × 104 | 2.0836 × 104 | 1.7919 × 104 | 1.1084 × 10−27 | 2.5605 × 10−1 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 2.5469 × 104 | 4.7079 × 103 | 3.3004 × 103 | 2.0802 × 10−27 | 4.7403 × 10−2 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f13 | Minimum | 5.8170 × 102 | 4.2538 × 102 | 5.2337 × 102 | 6.8061 × 10−6 | 9.9968 × 10−3 | 1.4714 × 10−7 |

| Mean | 7.6860 × 102 | 5.1784 × 102 | 7.0418 × 102 | 5.8565 × 10−1 | 4.2782 × 10−1 | 5.7884 × 10−5 | |

| SD | 8.8485 × 101 | 5.3366 × 101 | 1.0012 × 102 | 2.2350 × 100 | 2.6240 × 10−1 | 5.5313 × 10−5 | |

| f14 | Minimum | 2.8651 × 102 | 1.7279 × 102 | 1.8432 × 102 | 2.4167 × 10−2 | 1.8294 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| Mean | 3.4265 × 102 | 2.2056 × 102 | 2.4579 × 102 | 1.6991 × 101 | 5.5923 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| SD | 3.1232 × 101 | 2.8994 × 101 | 3.0792 × 101 | 1.9610 × 101 | 2.6074 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | |

| f15 | Minimum | 1.1903 × 109 | 4.5588 × 108 | 8.5860 × 108 | 2.0981 × 10−2 | 9.7967 × 101 | 8.0217 × 10−5 |

| Mean | 1.4696 × 109 | 7.2627 × 108 | 1.0713 × 109 | 2.4299 × 101 | 4.1217 × 102 | 2.7046 × 10−2 | |

| SD | 1.6924 × 108 | 1.5221 × 108 | 1.3442 × 108 | 2.9723 × 101 | 2.6843 × 102 | 3.3449 × 10−2 |

| Mean of HRPSO | Mean of HPLPSO | |

|---|---|---|

| f1 | 1.1326 × 10−27 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f2 | 9.3992 × 10−28 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f3 | 2.4307 × 10−57 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f4 | 4.5019 × 10−15 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f5 | 1.7458 × 10−1 | 8.7372 × 10−4 |

| f6 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f7 | 1.9936 × 10−27 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f8 | 1.8527 × 10−13 | 8.8818 × 10−16 |

| f9 | 2.5905 × 10−17 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f10 | 1.1844 × 10−8 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f11 | 1.7267 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f12 | 1.1084 × 10−27 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f13 | 5.8565 × 10−1 | 5.7884 × 10−5 |

| f14 | 1.6991 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 |

| f15 | 2.4299 × 101 | 2.7046 × 10−2 |

| Friedman test | Chi-sq = 14, p = 0.0002 < 0.05 | |

| Wilcoxon test | p = 0.0029 < 0.05, h = 1 | |

| 200 | 500 | 1000 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean of HRPSO | Mean of HPLPSO | Mean of HRPSO | Mean of HPLPSO | Mean of HRPSO | Mean of HPLPSO | |||

| f1 | 6.1508 × 10−27 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.8969 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | 9.7907 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f2 | 1.0074 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.7055 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | 6.0668 × 10−25 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f3 | 1.2700 × 10−49 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.0381 × 10−60 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.7464 × 10−48 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f4 | 6.0975 × 10−15 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.6619 × 10−14 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.1506 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f5 | 1.8719 × 10−1 | 2.7297 × 10−3 | 2.5039 × 10−1 | 7.6894 × 10−3 | 6.5771 × 10−1 | 1.3942 × 10−2 | ||

| f6 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f7 | 1.8738 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | 6.4970 × 10−22 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.2089 × 10−21 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f8 | 5.9419 × 10−13 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | 2.6649 × 10−12 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | 1.2656 × 10−8 | 8.8818 × 10−16 | ||

| f9 | 1.1842 × 10−16 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.3053 × 10−12 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.4803 × 10−17 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f10 | 1.1622 × 10−8 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.7767 × 10−9 | 0.0000 × 100 | 4.8138 × 10−9 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f11 | 6.5976 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.0162 × 105 | 0.0000 × 100 | 8.5539 × 104 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f12 | 5.7643 × 10−27 | 0.0000 × 100 | 2.8259 × 10−26 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.2397 × 10−25 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f13 | 6.4201 × 10−3 | 1.3925 × 10−4 | 5.7535 × 10−2 | 9.1016 × 10−3 | 3.2252 × 10−2 | 5.4160 × 10−4 | ||

| f14 | 4.3151 × 101 | 0.0000 × 100 | 1.5057 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | 3.1388 × 102 | 0.0000 × 100 | ||

| f15 | 4.3206 × 101 | 4.5509 × 10−2 | 8.6219 × 101 | 1.0665 × 10−1 | 2.6315 × 102 | 2.4985 × 10−1 | ||

| Friedman test | Chi-sq = 14, p = 0.0002 < 0.05 | Chi-sq = 14, p = 0.0002 < 0.05 | Chi-sq = 14, p = 0.0002 < 0.05 | |||||

| Wilcoxon test | p = 0.0033 < 0.05, h = 1 | p = 0.0029 < 0.05, h = 1 | p = 0.0022 < 0.05, h = 1 | |||||

| Parameter | t | L1 | L2 | n1 | n2 | R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 50 | 2100 | 2100 | 300 | 300 | 250 |

| Algorithm | HRPSO | HPLPSO |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum number of grid points covered | 88,622 | 89,730 |

| Coverage proportion | 97.82% | 99.04% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Z.; Guo, F. A High-Performance Learning Particle Swarm Optimization Based on the Knowledge of Individuals for Large-Scale Problems. Symmetry 2025, 17, 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122103

Xu Z, Guo F. A High-Performance Learning Particle Swarm Optimization Based on the Knowledge of Individuals for Large-Scale Problems. Symmetry. 2025; 17(12):2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122103

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Zhedong, and Fei Guo. 2025. "A High-Performance Learning Particle Swarm Optimization Based on the Knowledge of Individuals for Large-Scale Problems" Symmetry 17, no. 12: 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122103

APA StyleXu, Z., & Guo, F. (2025). A High-Performance Learning Particle Swarm Optimization Based on the Knowledge of Individuals for Large-Scale Problems. Symmetry, 17(12), 2103. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym17122103