Abstract

Developing countries face the dilemma of balancing economic development with the governance of the water environment. In the 21st century, water environment governance has become a core theme in Chinese society, prompting governments at all levels to introduce numerous policies in this area. However, the effectiveness of governance varies widely across regions. To address the shortcomings of existing research, which often adopts overly simplistic perspectives and lacks explanatory power, this study integrates previous findings on water environment governance, drawing on theories such as structuration and policy implementation to construct an institutional-actor analytical framework. Through a qualitative comparative analysis of the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative in 28 counties in Zhejiang, this study identifies four distinct configurations leading to different governance outcomes: the strong upper-pressure and command-dominated type, the strong target-pressure and market-dominated type, the weak-pressure and command-market hybrid type, and the weak-pressure and command-market hybrid type. The revelation of these diverse governance types deepens the understanding of causal pathways in environmental governance and provides valuable insights into water environment governance practices in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Developing countries often face the dilemma of balancing economic development with environmental protection [1]. The direct economic losses caused by environmental pollution in developing countries are significant annually, such as the 2005 pollution incident on the Songhuajiang River in China [2]. If environmental pollution issues in developing countries are not effectively addressed, it will be difficult to achieve sound governance of the global ecological environment. As a developing country, China presents considerable internal disparities in economic development levels and environmental quality challenges. Therefore, research on environmental governance in China is highly representative, and the findings offer valuable insights not only for other developing countries but also for developed nations, as demonstrated by the comprehensive pathway analysis of the Taihu Lake Cyanobacterial Bloom Incident [3].

In this study, our central focus resides in elucidating the causal mechanisms underlying disparities in local government environmental governance performance. More specifically, we interrogate whether—and if so, along which dimensions—the governance influencing factors and configuration of relationships driving performance differentials actually diverge, and how these heterogeneous elements interact to shape ultimate governance outcomes. To achieve the stated research objectives and investigate the key factors and underlying mechanisms influencing water environmental governance performance, a systematic review and analysis of the existing literature is essential. This foundational work will inform the development of the analytical framework and facilitate the formulation of testable research hypotheses.

Which factors influence the effectiveness of environmental governance? Researchers have approached this question from various perspectives, including regimes, governance institutions and policies, key actors, and governance tools, yielding numerous valuable findings. For example, some scholars argue that authoritarian regimes are less likely to achieve stronger environmental governance outcomes than are democratic systems [4]. Others, focusing on intergovernmental institutions and policies, contend that it is essential to carefully examine and assess their respective positions and behavioral orientations between central and local administrations, as significant areas of overlapping interests and similar patterns of behavior—both positive (e.g., enforcement) and negative (e.g., shirking) may exist between them [5]. Even when the central government introduces environmental protection policies, local officials may implement strategic behaviors in policy implementation, such as data manipulation [6] and pollutants at administrative boundaries that are not covered by assessment policies (e.g., heavy metals) show no signs of improvement. This suggests that local governments may be more oriented toward fulfilling specified performance indicators rather than genuinely focusing on water quality improvements relevant to public health [7].

From the perspective of governance actors, researchers argue that local party secretaries tend to prioritize economic development over environmental protection. However, comparatively younger officials are more conducive to improving local environmental governance outcomes [8], and when the secretary of the municipal Party Committee takes office in his or her hometown, enterprises invest more in environmental protection [9]. Moreover, the lack of independence of environmental protection enforcement agencies or officials is a critical factor leading to the failure of environmental regulations [10]. Additionally, since the beginning of the 21st century, environmental organizations have become increasingly active and frequent participants in China’s environmental governance arena. The “greening” transformation of the Chinese government, coupled with its flexible governance strategy oscillating between tolerance and strict control of social organizations, has shaped the gradualist development trajectory of Chinese environmentalism [11]. Concurrently, the increasing governmental emphasis on environmental protection and the administrative fragmentation resulting from internal bureaucratic divisions have created significant political opportunities for environmental organizations to engage in the articulation of public demands [12]. Environmental organizations with either strong governmental backgrounds or leadership possessing close personal ties to key officials demonstrate greater capacity to effectively leverage institutional channels for achieving environmental advocacy objectives [13], or in cases of environment-related conflicts, raise challenges and opposition to local governments’ project planning or environmental enforcement [14].

With respect to the effectiveness of mandatory, market-based, and participatory policy instruments, studies indicate that command-and-control tools can contribute significantly to environmental governance [15], prompting heavily polluting enterprises to increase their level of environmental investment [16]. Moreover, some studies find that economic incentive-based instruments yield optimal outcomes [17]. Scholars hold divergent views on public participation, and some researchers assert that public engagement exerts a positive influence on environmental governance [18]. However, other researchers have revealed that public participation does not automatically improve environmental governance performance, as its efficacy hinges on a multitude of conditions and factors [19]. Environmental education contributes to enhancing students’ environmental attitudes [20]; however, whether such attitudes translate into corresponding environmental protection behaviors and ultimately improve environmental governance performance requires further investigation.

In summary, while existing research on the governability of environmental issues in developing countries has adopted diverse perspectives and yielded valuable insights, certain limitations remain. First, many studies tend to focus on the environmental governance effects of single independent variables, failing to integrate multiple potential variables to examine their complex causal interactions on environmental outcomes. This linear causal understanding may oversimplify the intrinsic mechanisms of environmental governance and constrain practitioners’ exploration of the diverse pathways for environmental improvement. Second, prior research often portrays local governments in a negative light within the context of environmental governance. However, in practice, numerous local governments have actively advanced environmental initiatives and achieved significant results. How can we explain variations in environmental governance behaviors and effectiveness across local governments? This question warrants further investigation.

This study aims to explore the mechanisms through which local governments in developing countries achieve improvements in water environment quality. To achieve the aforementioned research aim, This study seeks to elucidate the key factors underlying disparities in local government performance in water environment governance, and to examine whether and how these factors constitute cogent causal mechanisms. To achieve the specified research objectives, the following research questions will be systematically examined: (1) Which factors within the dimensions of institutions, actors, and policy instruments potentially influence governance outcomes and qualify as relevant conditioning variables? (2) Among the selected variables, which demonstrate critical causal influence on the observed variation in final governance outcomes? (3) Does the causal architecture underlying performance variation constitute a single configuration or multiple conjunctural paths? How do those key influencing factors interconnect and interact to generate the ultimate outcomes? To address these questions, this paper draws on and integrates structuration theory and policy implementation theory to construct an “institution–actor” analytical framework. It introduces a case of water environment governance that is generally successful overall but exhibits performance variations across counties and districts, and analyzes through Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA).

2. Analytical Framework

A well-constructed analytical framework provides a basis for examining diverse theories and assessing their pertinence to resolving important problems. Given the strong explanatory power and applicability of structuration theory [21], as well as its capacity to integrate theories from new institutionalism and policy implementation, this paper constructs an “institution–actor” analytical framework on the basis of these theoretical resources.

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of the Analytical Framework

Since local environmental governance is inherently embedded in a bureaucratic governance field centered on government decision-making and implementation, relevant policy implementation theories serve as primary theoretical sources for constructing the analytical framework. With respect to the factors influencing policy implementation outcomes, Sabatier et al. (1980)’s integrated implementation model encompasses variables such as problem difficulty, statutory control, and nonstatutory factors [22]. Goggin et al. (1986) focused on incentives and constraints among the Federal, State, and Local Governments [23]. The integrated implementation model divides policy implementation into implementing actors and the implementation environment, emphasizing the impact of institutional resources and external societal influences on implementation outcomes. The intergovernmental implementation model further acknowledges that interactions among governments shape final policy results. Building on these models, it can be argued that the effectiveness of environmental governance policy implementation is closely linked to intergovernmental, state-society, and state-business interactions. Intergovernmental interactions are influenced by intergovernmental governance institutions, state-society interactions through civil society environmental participation mechanisms, and state-business interactions through the design of policy tools adopted by local governments.

While policy implementation theory identifies key actors and institutional resources that influence policy outcomes, it does not explicitly explain how these factors interact to produce divergent implementation effects. Since constructing an analytical framework requires hypothesizing the relationships among the key variables under examination, it is necessary to incorporate additional theoretical resources. Here, structuration theory proves particularly suitable as a foundational framework for integrating multiple theories, as it emphasizes institutions and actors. Furthermore, the new institutionalism provides preliminary mechanisms of action for the framework. Its three mechanisms—coercive, mimetic, and normative [24]—effectively link institutions with actors, offering a clearer depiction of the interactive relationships between institutional structures and agent behaviors.

Among the aforementioned theoretical resources, Structuration Theory illuminates the effective interaction and isomorphic relationship between actors and social structures. New Institutionalism further elaborates the isomorphic processes between institutions and actors through its three core institutional mechanisms. Policy Implementation Theory, in turn, introduces the key actors within the environmental governance arena and the potential influence relationships among them, thereby enhancing the analytical framework’s fit with the specific research context of this article.

Integrating these perspectives, Structuration Theory, New Institutionalism, and Policy Implementation Theory collectively frame structure (institution) and key actors as an interconnected whole. Within this framework, institutions function to set or influence the direction of actors’ actions to achieve fundamental order and specific objectives. Actors and their actions constitute the critical link connecting institutions to governance performance. In concrete practice, these actors may either comply with, circumvent, or challenge existing institutions, thereby generating distinct action outcomes.

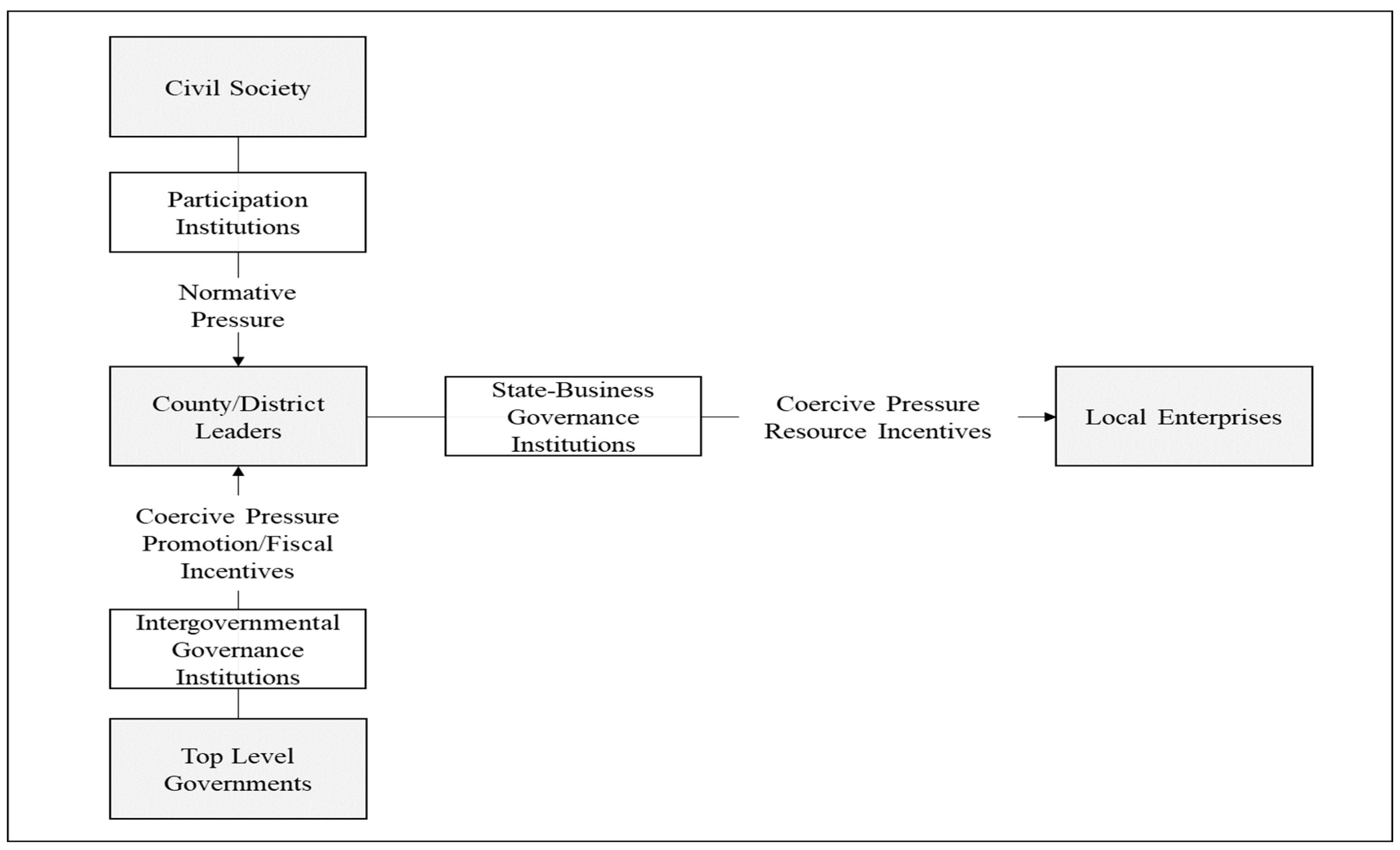

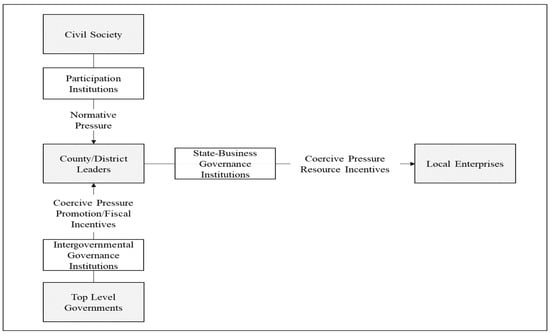

In summary, the “institution–actor” (Figure 1) analytical framework effectively centers on the research theme of this study, successfully incorporates diverse theoretical resources, and outlines the interactive relationships and hypothesized causal logic between institutions and actors. Furthermore, guided by this framework, it is possible to identify and select relevant variable conditions on the basis of the principle of balancing comprehensiveness and criticality from a multitude of factors influencing environmental governance, thereby laying the foundation for subsequent comparative case analysis.

Figure 1.

The “institutional-actor” analytical framework.

2.2. Elaboration of the Analytical Framework

Institutions are structural constraints that shape individual behavior [25]. The behavior formed under institutional constraints exhibits stability, regularity, and predictable patterns. At the level of local governance in China, intergovernmental governance institutions, such as target-setting, inspections, and supervisory mechanisms imposed by top level governments (In this article, “top level” consistently refers to provincial governments, while “local level” denotes county/district governments, hereafter the same.), carry a coercive character because of their exercise of authority. In contrast, institutions such as official promotion systems [26] and fiscal decentralization [27] have incentivizing effects.

In addition to pressure from top level governments, the civil society participation may also drive local environmental governance. When there is a consensus among the civil society regarding environmental governance expectations, it generates substantial normative pressure on governments through various forms of engagement. On the one hand, this can motivate top level governments to introduce or strengthen intergovernmental governance institutions, and on the other hand, it can urge county- and district leaders to increase their pollution control efforts within their jurisdictions.

Therefore, the intergovernmental governance institutions enacted by top level governments and societal public expectations mediated through the civil society participation mechanisms constitute critical structural elements that county- and district-level governments face. These institutions exert coercive pressure, motivational incentives, and normative pressure, thereby guiding and constraining the direction and intensity of governance actions taken by local leaders and ultimately influencing environmental governance outcomes.

In the context of environmental governance at the county and district levels, the Party Committee Secretary is regarded as an authoritarian figure in the local environmental policy implementation system. When confronted with normative pressure from society or subjected to coercive and incentive pressures from intergovernmental governance institutions, local leaders demonstrate a stronger motivation to promote environmental governance initiatives. They may introduce command-and-control instruments, such as standards and bans, and permit mandatory requirements for regulated entities. Alternatively, they may leverage market-based incentive mechanisms, including pollution discharge fees, environmental taxes, and emissions trading systems, to alter the cost–benefit calculations and even the relative market competitiveness of local enterprises. These measures aim to steer corporate behavior in specific directions, such as relocating operations away from regions with stringent environmental requirements or investing in environmental personnel and equipment to comply with regulatory standards [28].

Therefore, in the context of local water environmental governance, the outcomes are shaped by the interplay between institutions and actors. Institutions provide contextual conditions for actors, offering specific guidance, constraints, and support, while actors adopt diverse strategies in response to institutional regulations. More specifically, local environmental governance is jointly influenced by key actors, such as top level governments, county and district leaders, the civil society, and local enterprises. Among these, the top level governments serve as primary designers and supervisors of intergovernmental governance institutions. The civil society exerts its corresponding governance pressure on local governments. Moreover, county and district leaders are both constrained and influenced by intergovernmental institutions and civil society pressure while also designing and implementing local environmental governance measures that exert regulatory influence on enterprises within their jurisdictions. In the subsequent discussion, we employ this analytical framework to examine this case.

3. Research Design and Empirical Analysis

Amid rapid economic development, the aggregation of numerous heavily polluting industries has led to a sharp deterioration in the surface water quality in Zhejiang Province. In 2013, a series of high-profile incidents occurred across multiple localities in Zhejiang, where citizens publicly challenged environmental protection bureau directors to swim in polluted rivers. In November of the same year, the Provincial Party Committee and Government of Zhejiang launched the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative, headed by the Provincial Party Secretary and the Governor, with six vice-governor-level officials serving as deputy leaders.

“Five-Water Co-Governance” is a comprehensive initiative focusing on wastewater treatment, flood prevention, waterlogging control, water supply security, and water conservation. The program established a clear roadmap with phased timelines: “Three Years (2014–2016) to resolve critical issues with visible results; Five Years (2014–2018) to fundamentally address problems with comprehensive improvement; Seven Years (2014–2020) to achieve qualitative transformation with sustained outcomes, ensuring no sludge or polluted water enters the well-off society.” The implementation follows the principle of “Five-Water Co-Governance, Treatment First,” prioritizing pollution control as the foundational step.

With years of sustained governance efforts, the water quality in Zhejiang Province has significantly improved. According to data from the Zhejiang Provincial Environmental Status Bulletin, by 2017, the proportion of provincial monitoring sections with surface water quality meeting or exceeding Grade III standards had increased from 63.8% to 82.4%, and the overall water environment had transitioned from a warning state to a relatively safe condition. Therefore, on the basis of objective data or evaluations from the central government, the “Five-Water Co-Governance” Initiative in Zhejiang can be considered relatively successful. Therefore, this study employs the “institution–actor” analytical framework and conducts qualitative comparative case analysis to identify the governance typologies and causal mechanisms underlying the “Five-Water Co-Governance” actions across counties and districts in Zhejiang.

3.1. Research Methodology

Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) was developed by the American scholar Charles Ragin in the 1980s. This method enables a systematic comparison across cases while accounting for their internal complex causation [29]. Given that the “institution–actor” framework involves multiple conditioning variables and may generate complex conjunctural causality, the case-oriented QCA approach is well suited for this study. Moreover, restricting the case comparison to counties and districts within Zhejiang Province under the shared context of the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative aligns with the QCA’s practical requirements for cases with similar background conditions. Notably, although the “Five-Water Co-Governance” Initiative has been largely successful at the aggregate level, further analysis reveals significant variation in performance across localities. This heterogeneity meets another key recommendation in the QCA methodology: studies should ideally include both “positive” and “negative” outcomes to support robust causal inference.

3.2. Case Selection and Data Sources

This study selected 28 counties and districts in Zhejiang Province for qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) (see Table 1). The case selection process adhered to the following steps and principles: (1) a primary case pool comprising all 91 counties and districts in Zhejiang Province was established, and initial data collection was conducted; and (2) on the basis of data availability, cases that consistently exhibited good water quality—thus unable to reflect the outcomes of water improvement governance—were excluded, resulting in a final case set of 28 counties and districts.

Table 1.

List of selected county/district cases.

Owing to the absence of a unified database and varying levels of information disclosure across regions, this study collected and compiled relevant environmental governance data for Zhejiang Province from 2013 to 2017 through multiple channels. Data were primarily obtained from (1) information acquired via official government information disclosure requests filed by the researchers, with data provided by the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Environmental Protection, Prefecture-level environmental bureaus, and county/district environmental branches; (2) government official websites, mainly through the “Unified Government Website Information Search” portal of the Zhejiang Provincial People’s Government website and official sites such as the Provincial Bureau of Statistics; and (3) other public media sources, including reports from mainstream news portals and local media outlets.

3.3. Variable Setting and Calibration

3.3.1. Outcome Variables

The variables used to measure environmental governance outcomes can generally be categorized into four types: (1) single-process output variables, which select one or several indicators with typical process action or output as outcome variables, such as environmental governance investment, the number of local environmental regulations enacted, the number of environmental law enforcement cases handled, and the volumes of wastewater and waste gas emissions. (2) Aggregated process output variables: These studies combine multiple process output indicators into a single composite outcome variable to assess environmental governance results. (3) Single–Outcome Variables: These studies emphasize the final results of environmental governance, such as the concentration of pollutants, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, in water bodies. (4) Composite–Outcome Variables: These studies adopted comprehensive water quality grades (Classes I–V) defined by national standards, which were calculated on the basis of multiple indicators, as outcome variables.

Given that process-output indicators—such as environmental governance investment, the number of local regulations enacted, and the quantity of environmental enforcement cases—primarily reflect regulatory or resource-based actions undertaken by county and district leaders and represent only intermediate processes or potential precursors to final environmental performance outcomes, this study adopts a result-oriented approach to assess the ultimate effectiveness of “Five-Water Co-Governance” and selects comprehensive water quality as the evaluation criterion. Specifically, An increase in the number of surface water monitoring sections (at the prefecture level) achieving Class III or better water quality by the end of 2017 compared to the end of 2013 is used as an indicator for assessing governance outcomes.

The decision to adopt the comprehensive water quality classification standard as the outcome variable in this study is based on the following rationales:

Primarily, the water quality standards are derived from the Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water (GB 3838-2002) ( https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/shjzlbz/200206/t20020601_66497.shtml, accessed on 3 November 2025), jointly issued by China’s former State Environmental Protection Administration and the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection, and Quarantine. This national standard categorizes surface water into five classes according to functional hierarchy (see Table 2 below), with each class defining explicit threshold limits for parameters including COD, BOD5, NH3-N, phosphorus, heavy metals, and other constituents, ensuring professional authority and methodological rigor.

Table 2.

Water function and standard classification table.

Furthermore, in practice, both the central government and provincial authorities in China primarily utilize the proportion and incremental improvement of Grade III water quality monitoring sections at the prefecture level as key metrics for assessing regional water quality and governance outcomes in their official environmental quality reports. Consequently, this study aligns with the official statistical reporting framework by adopting this standardized metric.

Finally, the selection is contextually grounded in the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative—a campaign launched by Zhejiang’s provincial leadership characterized by strong target orientation. This institutional context incentivizes lower-level local governments to prioritize the enhancement of Grade III water sections as their central operational focus. Employing alternative water quality benchmarks might fail to accurately capture this targeted governance effort, potentially leading to distorted performance evaluations.

3.3.2. Causal Conditions

In QCA practice, for medium-sized samples, selecting between four and seven explanatory conditions is recommended [29]. On the basis of the analytical framework and empirical knowledge of the cases, seven explanatory conditions were selected from the institutional and actor dimensions, fulfilling the requirement for a conditional setting in medium-N studies.

(1) Target responsibility pressure: The number of Grade IV and Grade V water quality sections among the prefecture-level monitored sections in each region (compiled by local government environmental agencies in accordance with the parameters and thresholds specified in the Environmental Quality Standards for Surface Water (GB 3838-2002) was selected to measure the target responsibility pressure. Because these sections are monitored primarily by top level and regional level environmental agencies, higher-level governments can accurately assess local water quality conditions. A greater number of noncompliant sections indicates greater governance pressure on county and district governments, likely prompting intensified water remediation efforts.

(2) Upper-level inspection pressure: Numerous studies have shown that environmental inspections are conducive to improving governance outcomes [30]. Considering the top-down enforcement characteristic of policy implementation in China, inspection pressure is measured by the total number of inspections conducted by provincial inspection teams (Non-Central Environmental Protection Inspection) and visits made by the Provincial Party Secretary to each locality during the water governance campaign. This composite indicator reflects the intensity of supervisory pressure from higher authorities.

(3) Local Fiscal Pressure: In addition to the aforementioned pressures, local economic development demands and fiscal resource endowments may also influence local environmental governance. Considering that environmental governance may impede local economic growth and fiscal revenue and thus reduce motivation for governance, this study also selects county/district fiscal pressure as an additional proxy variable in the institutional incentive dimension.

(4) Civil society pressure: In addition to coercive pressure, civil society participation may serve as a source of normative pressure, motivating local governments to implement environmental governance. As the civil society environmental satisfaction effectively represents external normative pressure, this study uses the results of public environmental satisfaction surveys conducted by the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Ecology and Environment across counties and districts as a measure of normative pressure, assessing its impact on final governance outcomes.

(5) Age of the County/District Party Secretary: Although multiple organizations and individuals are involved in local environmental governance, the Party Secretary holds an authoritarian role in the process. Moreover, as the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative was a high-priority campaign launched by the Provincial Party Secretary, it is reasonable to assume that younger county/district Party Secretaries may be more motivated to demonstrate effort and achievement through vigorous water governance to gain recognition from provincial leaders. Compared to the generally short tenures of local officials—which may incentivize them to pursue quicker and simpler responses to environmental issues—this approach proves detrimental to fundamental environmental remediation [31], thus, the age of the party secretary is selected as a proxy variable for the actor dimension.

(6) Command-and-control intensity: Command-and-control instruments represent a crucial type of environmental governance institution. This study selected the total amount of environmental fines imposed as a measure of the local government’s command-and-control intensity. Generally, higher fine amounts indicate expansion and intensification of coercive enforcement.

(7) Market-based incentive intensity: Market-based incentive tools constitute another key environmental governance institution. Because previous pollution discharge fee standards were relatively low, firms often preferred to pay for pollution. Given that Zhejiang Province is a national leader in emissions trading, the ratio of emissions trading volume (calculated based on the trading value of chemical oxygen demand (COD), ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N), and total phosphorus) to GDP in each county/district was selected to measure market-based incentive intensity.

After the outcome variable and causal conditions are defined and on the basis of the analytical framework and existing research, the study hypothesizes the following potential relationships between each causal condition and governance outcome (see Table 3):

Table 3.

Theoretical Expectations.

After the causal conditions were defined, calibrating the collected indicator data was necessary. This study adopted the calibration thresholds recommended for fsQCA: full membership (0.95), crossover point (0.5), and full non-membership (0.05). The corresponding calibration results are detailed in the following table (Table 4).

Table 4.

Configuration of causal conditions and calibration results for case cities in the QCA.

3.4. Empirical Analysis Results

3.4.1. Analysis of the Necessary Conditions

Prior to conducting a configurational analysis, it is necessary to test the “necessity” of individual conditions. In QCA, consistency measures the degree to which cases sharing a given combination of causal conditions agree in displaying the outcome, whereas coverage assesses the extent to which a causal condition or combination of conditions “explains” instances of the outcome set. The purpose of testing individual conditions was to determine whether a condition was necessary for the outcome. A condition was considered necessary for the outcome variable if its consistency level exceeded 0.9. This study analyzes both “high” and “low” performance scenarios, yielding necessity analysis results for desirable and undesirable governance performance states.

As shown in the table (Table 5), the consistency levels of all the conditions are below 0.9, indicating that no single causal variable alone determines the water governance outcomes in the case cities. Instead, the outcomes are produced through the interaction of multiple conditions.

Table 5.

Analysis of necessary conditions for causal conditions.

3.4.2. Configurational Analysis of Multiple Causal Conditions

To analyze the configurational effects of the causal conditions, a truth table was constructed. Following conventional practice, the raw consistency threshold was set at 0.8, and the case frequency threshold was set at 1. This yields complex, parsimonious, and intermediate solutions for causal pathways. This paper reports both intermediate and parsimonious solutions. The conditions that appear in both the intermediate and parsimonious solutions are identified as core conditions, whereas those present only in the intermediate solution are considered peripheral conditions. The analysis reveals seven configurations (Table 6), associated with both high and low governance performance.

Table 6.

Configurations of local government water environmental governance.

3.5. Configuration Classification and Causal Mechanism Models

3.5.1. Configuration Classification

On the basis of the analytical results, five configurations were identified to lead to relatively high governance performance. Configuration S1 is characterized by core conditions, including high upper-level inspection pressure, low civil society pressure, a relatively young county/district party secretary, and strong corporate command and control. Configuration S2 features core conditions, such as low target responsibility pressure, high upper-level inspection pressure, low civil society pressure, a relatively young county/district party secretary, strong corporate command-and-control, and strong market incentives. Configuration S3 contains three core conditions: low target responsibility pressure, strong corporate command and control, and strong market incentives. Configurations S4 and S5 share core conditions, including high target responsibility pressure, a relatively young county/district party secretary, and strong market incentives, forming second-order equivalent configurations. Additionally, the two configurations were associated with relatively low governance performance. Configuration S6 is defined by core conditions, including low target responsibility pressure, a relatively young county/district party secretary, weak command-and-control, and weak market incentives. Configuration S7 has core conditions comprising low upper-level inspection pressure, low local fiscal pressure, an older county/district party secretary, and low-intensity command-and-control.

According to the QCA results, among the various configurations that achieve high governance performance, Configurations S1 and S2 share the most core conditions (high upper-level inspection pressure, low civil society pressure, relatively young county/district party secretaries, and strong command-and-control). Additionally, data analysis revealed that in Wuyi County, a typical case of Configuration S2, the intensity of market incentive usage was significantly lower than that of command-and-control incentives. To avoid unnecessary complexity, both S1 and S2 are classified as strong upper pressure and command-dominated governance. Furthermore, since S4 and S5 completely share core conditions (high target responsibility pressure, a relatively young county/district party secretary, and strong market incentives) and constitute second-order equivalent configurations, they are categorized as strong target pressure and market-dominated governance. Configuration S3 is relatively distinct, lacking clear pressure sources but exhibiting high intensity in both command-and-control and market incentives. It is tentatively labeled weak pressure and command-market hybrid governance. The two configurations associated with poor governance performance are classified as weak-pressure and command-market-deficient governance given their similarity across most conditions.

On the basis of the above classification, four distinct governance configurations exist in the “Five-Water Co-Governance” actions across the case cities: the strong upper-pressure and command-dominated governance configuration, the strong target-pressure and market-dominated governance configuration, the weak-pressure and command-market hybrid governance configuration, and the weak-pressure and command-market deficient governance configuration.

(1) Strong upper pressure and command-dominated governance configuration. The logic by which this configuration leads to relatively high environmental governance performance is as follows. After the launch of the “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative, frequent inspections by top level governments created significant pressure on local officials. To avoid negative impacts on their promotion prospects and strive to achieve superior governance outcomes more rapidly than their peers in a policy area prioritized by the Provincial Party Secretary, local leaders adopted a governance system centered on command-and-control instruments. By rigorously penalizing local enterprises that violated pollution discharge standards or failed to meet emission reduction targets, improvements in local water quality were achieved. For example, since it became the permanent host venue of the World internet Conference in 2014, Tongxiang city has attracted attention from the highest levels of national leadership, which directly influences the city’s environmental governance actions. Under such circumstances, top level governments can effectively incentivize local environmental governance implementation by adopting stringent reward-penalty mechanisms—such as the “one-vote veto” system and performance-based target assessments—to reshape local governmental behavior [32].

(2) Strong target pressure and market-dominated governance configuration. This configuration demonstrates a distinct preference for market-based incentives. The underlying logic can be explained as follows: Under the policy direction of “Five-Water Co-Governance,” severe pollution in local water quality created significant pressure on relatively young local leaders. To avoid accountability from top level governments and to protect their political careers, these leaders face substantial governance pressure. However, they revealed that the characteristics of entrepreneurial local officials are influenced by individual preferences and historical constraints. This led them to emphasize the design and application of market-based incentives in environmental governance, thereby addressing pollution at its source and improving local water quality. For example, Haining pioneered factor marketization reforms and supported emissions trading system reforms in Zhejiang Province as early as 2013. It implemented comprehensive efficiency evaluations, including industrial value-added per unit COD indicators, for heavily polluting industries, linking these assessments to resource allocation decisions and thus incentivizing local enterprises to enhance their environmental management.

(3) Weak-pressure and command-market hybrid governance configuration. Among the various configurations, this configuration is the most challenging to interpret. Why do local authorities implement both strong command-and-control measures and market-based incentives in contexts where water pollution is not severe, upper-level inspection pressure is low, and local leaders are not particularly young? An analysis of the water quality improvement trajectory and official characteristics of Linhai city provides a preliminary explanation. The data revealed that Linhai achieved its water governance targets by the end of 2016. Since the county party secretary concurrently served as a standing committee member of the prefectural-level city’s party committee, this older but higher-ranking official likely intensified water governance efforts to extend his political career, And when local governments employ diversified policy instruments—including market-based mechanisms and command-and-control measures—environmental governance performance in the respective jurisdictions has consequently improved significantly [32].

(4) Weak-pressure and command-market-deficient governance configuration. This governance configuration is characterized by low target responsibility pressure, minimal upper-level inspection pressure, and weak implementation of both command-and-control measures and market-based incentives. In the absence of significant water governance pressure, local leaders function as limited-compliance actors and are more likely to direct their efforts and attention toward other matters that impact their political performance, such as economic development, investment promotion, and infrastructure construction, this signifies that local governments will selectively adopt operational strategies that maximize their institutional self-interest [33]. Consequently, in a context lacking both governance motivation and substantive initiatives, the limited environmental governance outcomes observed in these localities are readily understandable, local interest preferences shape skewed enforcement outcomes.

3.5.2. Causal Mechanism of Local Government Water Environmental Governance

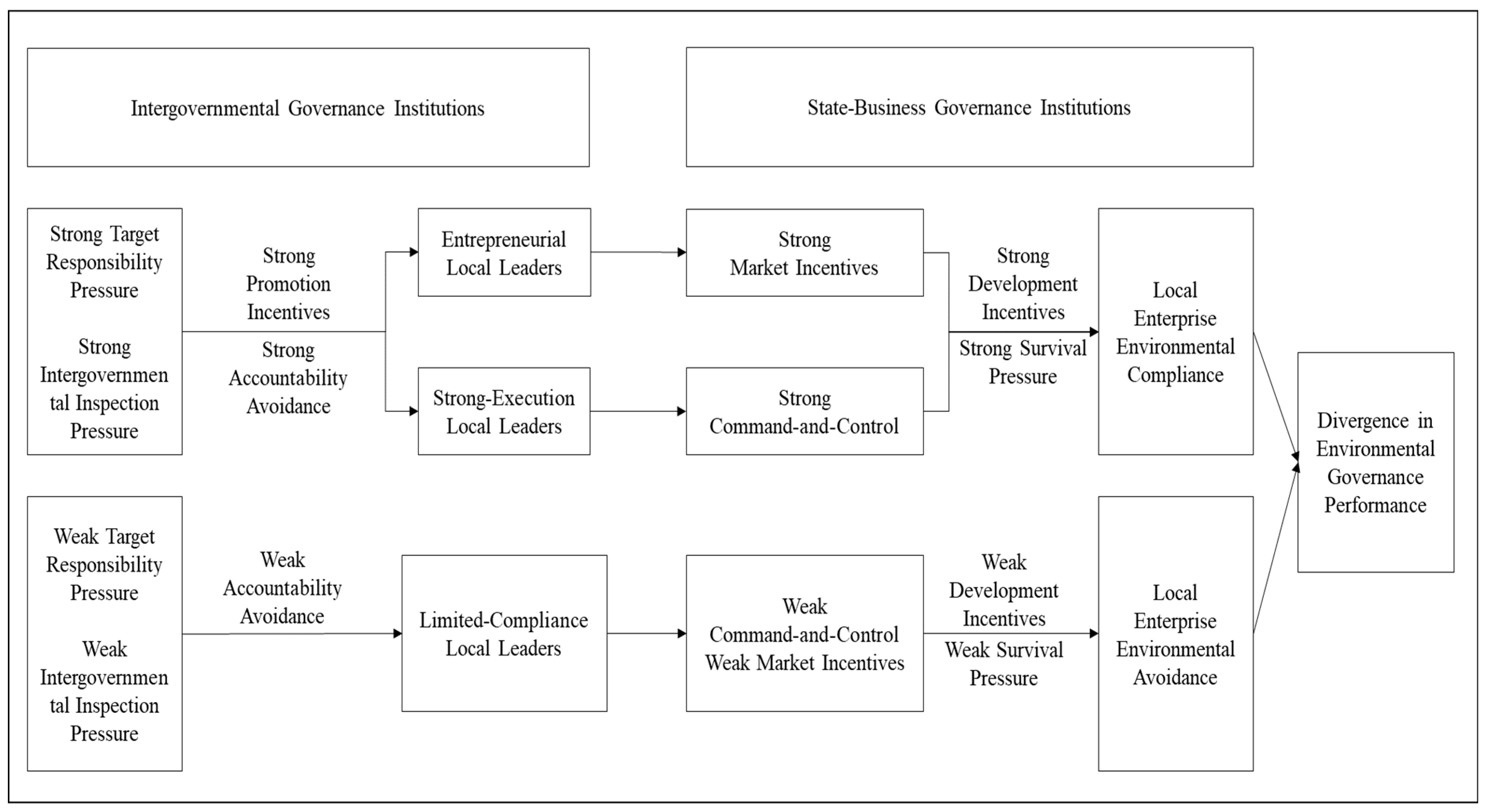

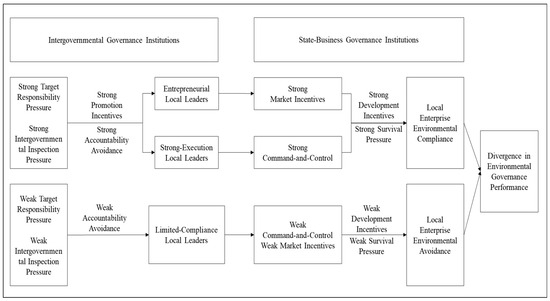

By integrating the “institution–actor” analytical framework with configurational analysis, it can be argued that water environmental governance performance is shaped primarily by the joint influence of institutions (intergovernmental governance institutions and state-business governance institutions) and actors (top level governments, local leaders, and local enterprises). The institutional environment includes sources of coercive pressure and incentives. Local leaders can be categorized as entrepreneurial leaders, strong-execution leaders, and limited-compliance leaders, whereas local enterprises include governance-compliant and governance-avoidant firms.

Environmental outcomes are generated through two mechanisms within the water governance process: vertical pressure transmission and horizontal incentive competition. Specifically, intergovernmental governance institutions create varying degrees of vertical coercive pressure and horizontal promotion competition incentives through target-responsibility systems and upper-level inspections. These are interpreted and assessed by local leaders, generating motivations for responsibility avoidance and the pursuit of promotion, which subsequently influence their governance decisions and the selection of state-business governance institutions. Since the survival pressures and development incentives produced by different state–business governance institutions vary in type and intensity, local enterprises conduct cost–benefit assessments under these differing conditions and adopt corresponding actions.

Thus, the institutional environment and actors collectively constitute the core elements of the water environment governance mechanism. The institutional environment adjusts and influences actors’ specific actions through vertical pressure transmission and horizontal incentive competition, thereby affecting the final environmental governance outcomes. This constitutes an intrinsic causal mechanism of local water environmental governance (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Causal mechanism model of local government water environmental governance.

3.6. Robustness Test

A robustness test is required following configurational analysis. Such testing can be conducted by altering the case frequency threshold or by adjusting the consistency threshold. In line with mainstream QCA research practices, this study increased the consistency threshold by 0.05, using 0.85 instead of the initial value of 0.80. Rerunning the QCA with this adjusted threshold revealed that the resulting configurations, consistency of the solutions, and overall coverage remained unchanged. Therefore, it can be concluded that this study passed a robustness test.

4. Findings and Conclusions

4.1. Findings

On the basis of the “institution–actor” analytical framework, this study selected target responsibility pressure, upper-level inspection pressure, local fiscal pressure, civil society pressure, the age of the county/district party secretary, command-and-control intensity, and market incentive intensity as causal conditions. Using the QCA of 28 county/district cases in Zhejiang Province, the following preliminary findings were drawn:

(1) Among the various factors influencing environmental governance outcomes, upper-level inspection pressure, age of the county/district party secretary, command-and-control intensity, and market incentive intensity demonstrate relatively clear causal relationships with environmental governance performance. Specifically, upper-level inspection pressure, command-and-control intensity, and market incentive intensity were positively correlated with desirable governance outcomes, whereas an older party secretary was associated with less ideal results.

(2) Four configurations that lead to divergent environmental governance outcomes were identified. Three are associated with relatively high performance: the strong upper-pressure and command-dominated type, the strong target-pressure and market-dominated type, and the weak-pressure and command-market hybrid type. One configuration corresponds to relatively low performance: the weak-pressure and command-market deficient type.

(3) Vertical coercive pressure and horizontal competitive incentives embedded within the institutional environment shape the governance motivations and actions of both local leading officials and local enterprises, ultimately determining environmental governance performance. Stated differently, local leading officials are driven to actively engage in water governance due to vertical coercive pressures (e.g., target responsibility systems and intergovernmental inspections) and horizontal promotion competition. Concurrently, these officials employ either mandatory policy instruments or market-based incentives reflecting entrepreneurial approaches to regulate polluting enterprises. Meanwhile, local enterprises intensify their water environment governance efforts in response to vertical command-and-control pressures and competition for developmental resources in the horizontal dimension.

4.2. Conclusions

Building upon the research questions posed earlier—regarding which factors critically influence water governance outcomes, whether the causal configurations are singular or multiple, and what underlying mechanisms operate—this study provided preliminary answers. Our investigation revealed that key determinants include top-down inspection pressure, the age of local leading officials, command-and-control instruments, and market-based incentives. These elements coalesced into four distinct governance configurations. Fundamentally, both vertical coercive pressures and horizontal competitive dynamics compelled or incentivized local governments and enterprises to engage in water environmental governance, thereby generating differentiated performance outcomes.

It should be emphasized, however, that these conclusions were contingent upon specific preconditions: namely, the presence of a highly authoritative top level government capable of effectively incentivizing or sanctioning subordinate local officials. This authority must be institutionalized to consistently exert pressure, thereby transforming environmental governance from short-term interventions into sustained long-term efforts, ultimately yielding stable governance performance. Additionally, in the interaction between local governments and local enterprises regarding environmental governance, the comprehensive application of market-based instruments such as emission trading systems, coupled with incentives tied to other production factors, may yield more enduring effects than relying solely on mandatory policy directives.

Although civil society pressure, as represented by environmental satisfaction surveys, did not emerge as a sufficient condition for effective governance in this study—a finding that diverged from some existing research [18]. This result should be interpreted with caution. In modern societies, the civil society can exert governance pressure through various channels. Notably, one visible catalyst for the initiation of Zhejiang’s “Five-Water Co-Governance” initiative was citizen activism on social media, including public challenges to local environmental officials to swim in polluted rivers.

For other developing countries to promote the balanced development of water, society, and ecology [34], these findings underscored the critical importance of institutional design. Effective institutions must either amplify public governance pressure or transmit firm and consistent mandates from upper-level governments, thereby creating crucial windows of opportunity for environmental governance. The historical trajectory of “develop first, clean up later” has proven detrimental in many developed nations. The central challenge lay in designing institutions that embed environmental considerations into the decision-making calculus of local officials. The study also held relevance even for developed countries, which similarly face the challenge of balancing economic development with environmental governance (e.g., in areas such as water eutrophication and biodiversity). For these countries, it remained essential to incorporate environmental governance needs into the behavioral constraints and incentives of relevant actors through institutional design. In this regard, the governance experience of Zhejiang Province, China, offered valuable insights.

However, this study had certain limitations. Methodologically, the employed QCA approach did not incorporate dynamic analysis across temporal sequences, when applying this method to analyze complex systems such as water environment governance—characterized by the dynamic interplay of numerous natural and social factors as well as multiple actors—some analytical bias was inherently unavoidable. Furthermore, the research failed to conduct longitudinal case studies of representative cities identified through QCA to examine motivation and interaction processes among potential key actors. These methodological constraints affected the internal validity of the causal inferences, for instance, in the weak-pressure and command-market hybrid governance configuration, does an older but higher-ranking local official engage in environmental governance because they remain relatively younger compared to peers at the same level in other prefecture-level cities—thus retaining motivation for deferred retirement or even further promotion—or because of generational differences in environmental awareness among officials? Additionally, as the study was primarily conducted within the Chinese context without incorporating samples from other developing countries, further validation would be necessary before generalizing these findings to other national contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: F.L. and Q.F.; methodology: F.L. and Y.S.; visualization: Q.F.; funding acquisition: Q.F.; project administration: Y.S.; supervision: Y.S.; writing—original draft: F.L., Q.F. and Y.S.; writing—review and editing: F.L., Q.F. and Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the General Project of Philosophy and Social Science Research in Colleges and Universities in Jiangsu Province (2022SJYB0727).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hunjra, A.I.; Bouri, E.; Azam, M.; Azam, R.I.; Dai, J. Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability in Developing Economies. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; You, Z.; Liu, B. Economic Estimation of the Losses Caused by Surface Water Pollution Accidents in China from the Perspective of Water Bodies’ Functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, G.; Bao, C. Evolution and Mechanism of Intergovernmental Cooperation in Transboundary Water Governance: The Taihu Basin, China. Water 2025, 17, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilley, B. Authoritarian Environmentalism and China’s Response to Climate Change. Environ. Politics 2012, 21, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostka, G.; Nahm, J. Central–Local Relations: Recentralization and Environmental Governance in China. China Q. 2017, 231, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Implementation of Pollution Control Targets in China: Has a Centralized Enforcement Approach Worked? China Q. 2017, 231, 749–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, M.E.; Li, P.; Zhao, D. Water Pollution Progress at Borders: The Role of Changes in China’s Political Promotion Incentives. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2015, 7, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Yin, A.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Zhan, P. Motivating for Environmental Protection: Evidence from County Officials in China. World Dev. 2024, 184, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N. Local Officials’ Hometown Preference and Enterprises’ Environmental Investment Behavior. Int. Stud. Econ. 2025, 20, 106–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing-Hung Lo, C.; Tang, S.-Y. Institutional Reform, Economic Changes, and Local Environmental Management in China: The Case of Guangdong Province. Environ. Politics 2006, 15, 190–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. Greening Without Conflict? Environmentalism, NGOs and Civil Society in China. Dev. Change 2001, 32, 893–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Spires, A.J. Advocacy in an Authoritarian State: How Grassroots Environmental NGOs Influence Local Governments in China. China J. 2018, 79, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teets, J. The Power of Policy Networks in Authoritarian Regimes: Changing Environmental Policy in China. Governance 2018, 31, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhardt, H.C.; Wu, F. In the Name of the Public: Environmental Protest and the Changing Landscape of Popular Contention in China. China J. 2016, 75, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.; Luo, J.; Yang, Y.; Tu, Y. Analysis of the Influence and Coupling Effect of Environmental Regulation Policy Tools on Industrial Green and Low-Carbon Transformation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chai, S.; Li, S.; Sun, Z. How Environmental Regulation Affects Green Investment of Heavily Polluting Enterprises: Evidence from Steel and Chemical Industries in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Wen, S. Interaction Effects of Market-Based and Incentive-Driven Low-Carbon Policies on Carbon Emissions. Energy Econ. 2024, 137, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, M.; Liu, J.; Tan, Z. Public Environmental Concern, Government Environmental Regulation and Urban Carbon Emission Reduction—Analyzing the Regulating Role of Green Finance and Industrial Agglomeration. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Yin, W.; Jin, Y. Analyzing Public Environmental Concerns at the Threshold to Reduce Urban Air Pollution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, D.; Liu, S. The Impact of Environmental Education at Chinese Universities on College Students’ Environmental Attitudes. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, R. Structuration Theory: Giddens and Beyond. In Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice; Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L., Seidl, D., Vaara, E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2025; pp. 113–129. ISBN 978-1-00-921606-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatier, P.; Mazmanian, D. The Implementation of Public Policy: A framework of Analysis. Policy Stud. J. 1980, 8, 538–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggin, M.L. The “Too Few Cases/Too Many Variables” Problem in Implementation Research. West. Political Q. 1986, 39, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. In Advances in Strategic Management; Emerald (MCB UP): Bingley, UK, 2000; Volume 17, pp. 143–166. ISBN 978-0-7623-0661-9. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, H.R.; Argote, L. Behavioral Theories of Organization. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 481–486. ISBN 978-0-08-097087-5. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, K.; Ying, Z.; Liu, W. Effects of the Promotion Pressure of Officials on Green Low-Carbon Transition: Evidence from 277 Cities in China. Energy Econ. 2024, 129, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, G. Fiscal Decentralization, Government Self-Interest and Fiscal Expenditure Structure Bias. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 1133–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; He, C.; Liu, Y. Going Green or Going Away: Environmental Regulation, Economic Geography and Firms’ Strategies in China’s Pollution-Intensive Industries. Geoforum 2014, 55, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B.; Ragin, C. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-1-4129-4235-5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Bi, J.; Liu, M.; Li, S. Does the Central Environmental Inspection Actually Work? J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 253, 109602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.; Kostka, G. Authoritarian Environmentalism Undermined? Local Leaders’ Time Horizons and Environmental Policy Implementation in China. China Q. 2014, 218, 359–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreifels, J.J.; Fu, Y.; Wilson, E.J. Sulfur Dioxide Control in China: Policy Evolution during the 10th and 11th Five-Year Plans and Lessons for the Future. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, Z. Strong Negative Incentive and Weak Implicit Negotiation: The Campaign-Style Environment Governance in China. J. Glob. Area Stud. 2019, 3, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Su, Y.; Geng, J.; Shu, S.; Liu, Y. A Comprehensive Study of Water Resource–Environment Carrying Capacity via a Water-Socio-Ecological Framework and Differential Evolution-Based Projection Pursuit Modeling. Water 2025, 17, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).