A Review of Riverbank Filtration with a Focus on Tropical Agriculture for Irrigation Water Supply

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

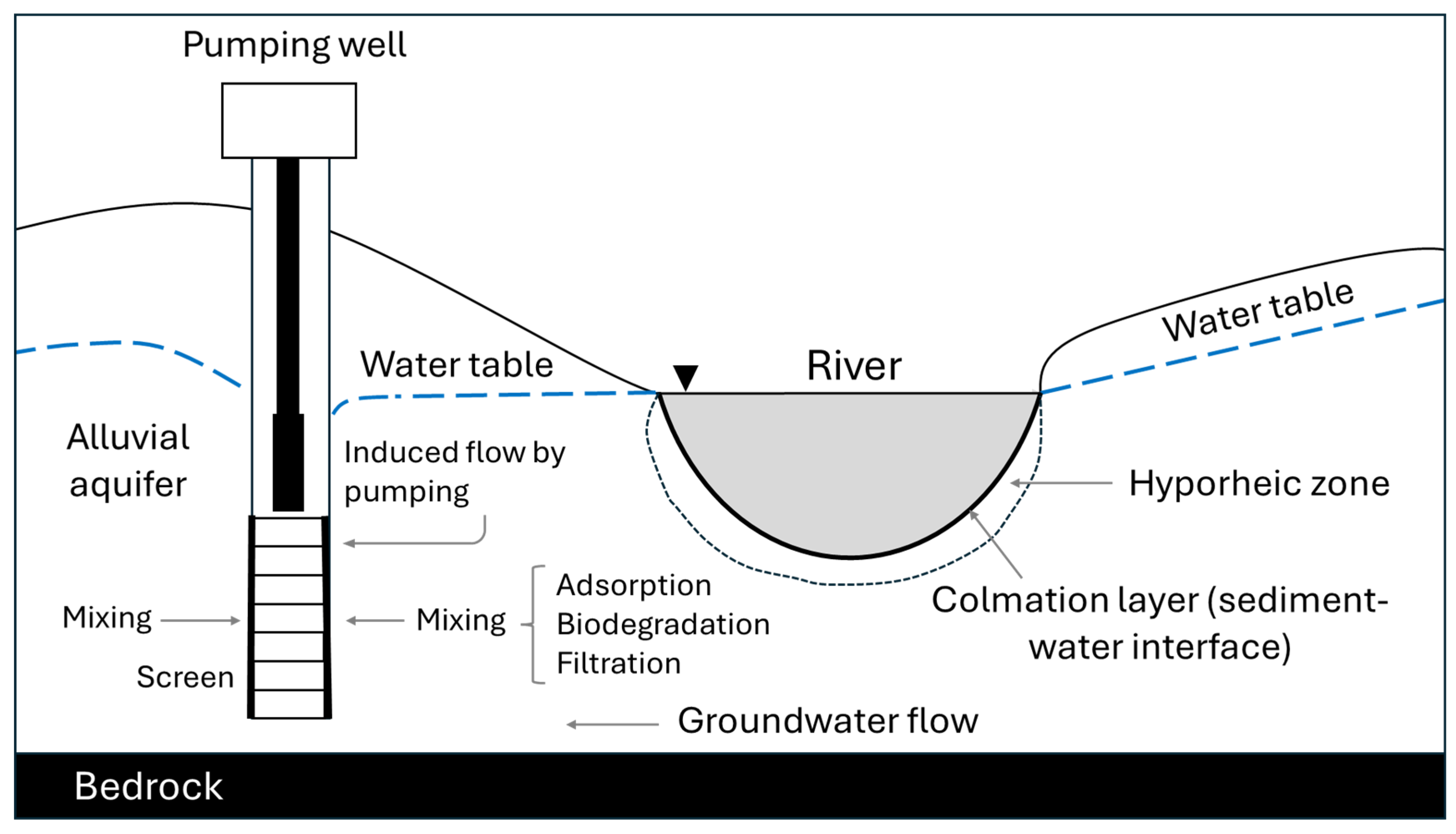

3. RBF Technology Background and Principles

3.1. Induced Hydraulics, Collector Wells, and Infiltration Performance

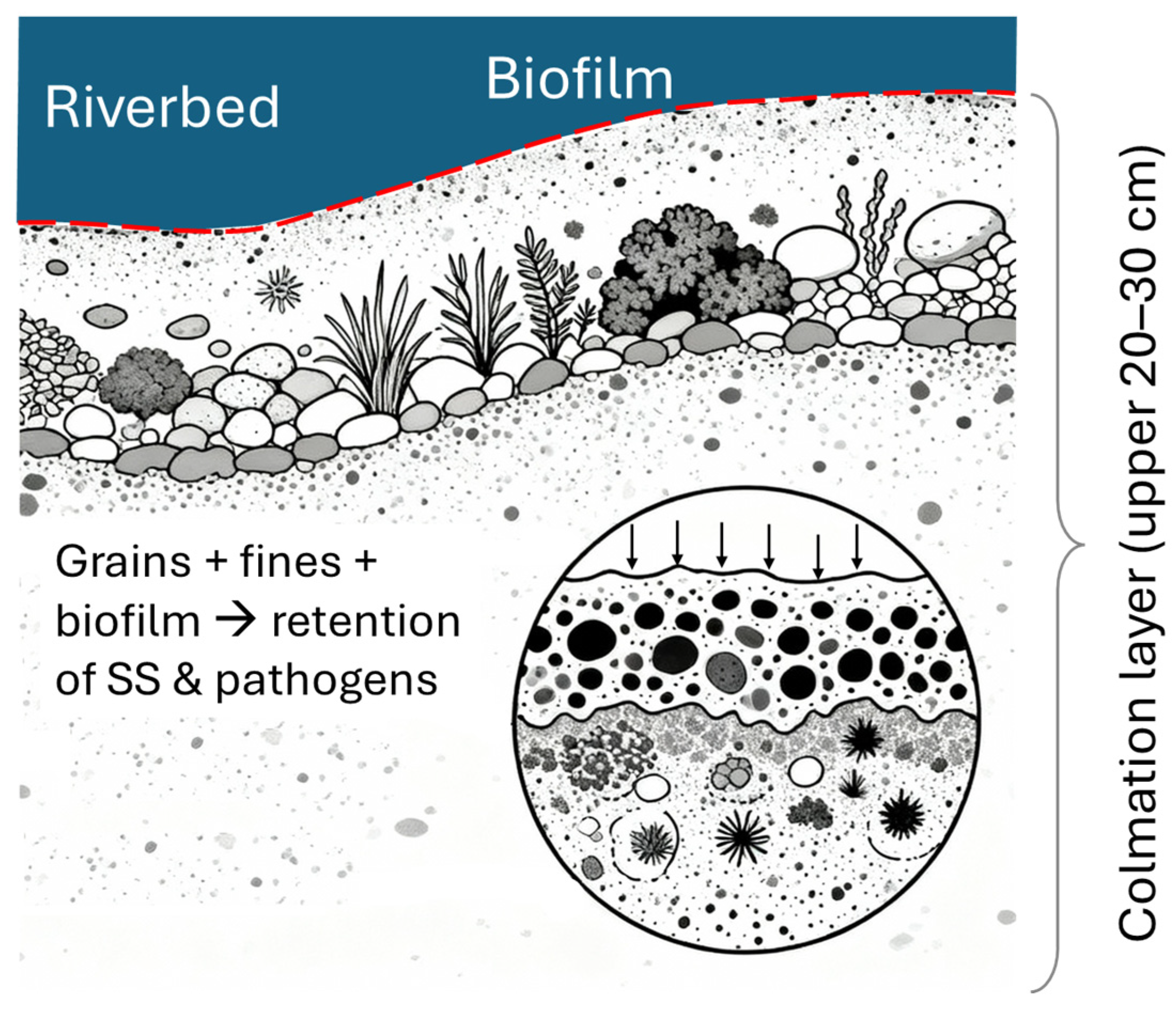

3.2. Sediment-Rich Tropical Rivers: Challenges and Adaptations for RBF Systems

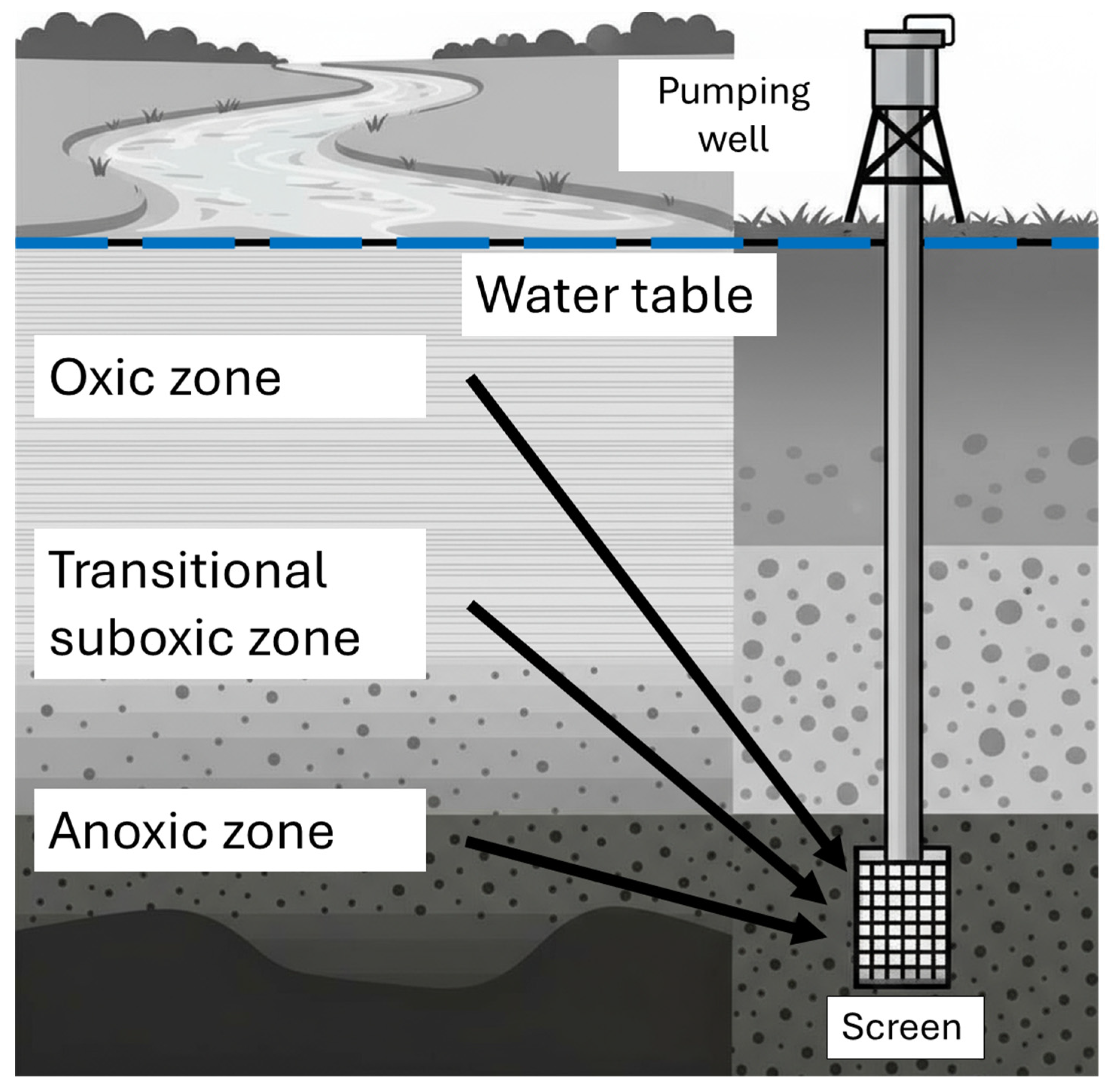

3.3. Attenuation Mechanisms Along the Subsurface Flow Path

3.4. Hydrostratigraphy, Mineralogy, and Heterogeneity Controls

3.5. Seasonal Hydrology and Shifting Pathogen/Chemical Risk

4. Engineering Design and Implementation

4.1. Site-Scale Hydrogeologic Design Criteria

4.2. Abstraction Architecture

4.3. Global Engineering Parameters

4.4. Pre-Treatment Under Sediment-Rich Tropical Conditions in Micro-Irrigation

4.5. Techniques for RBF Site Characterization

5. Water Quality Improvement Mechanisms

5.1. Mechanistic Overview of Subsurface Treatment and Particulate Control

5.2. Pathogen Attenuation and Microbiological Stability

5.3. Nitrogen Transformations Under Redox Stratification and Compound-Specific Attenuation

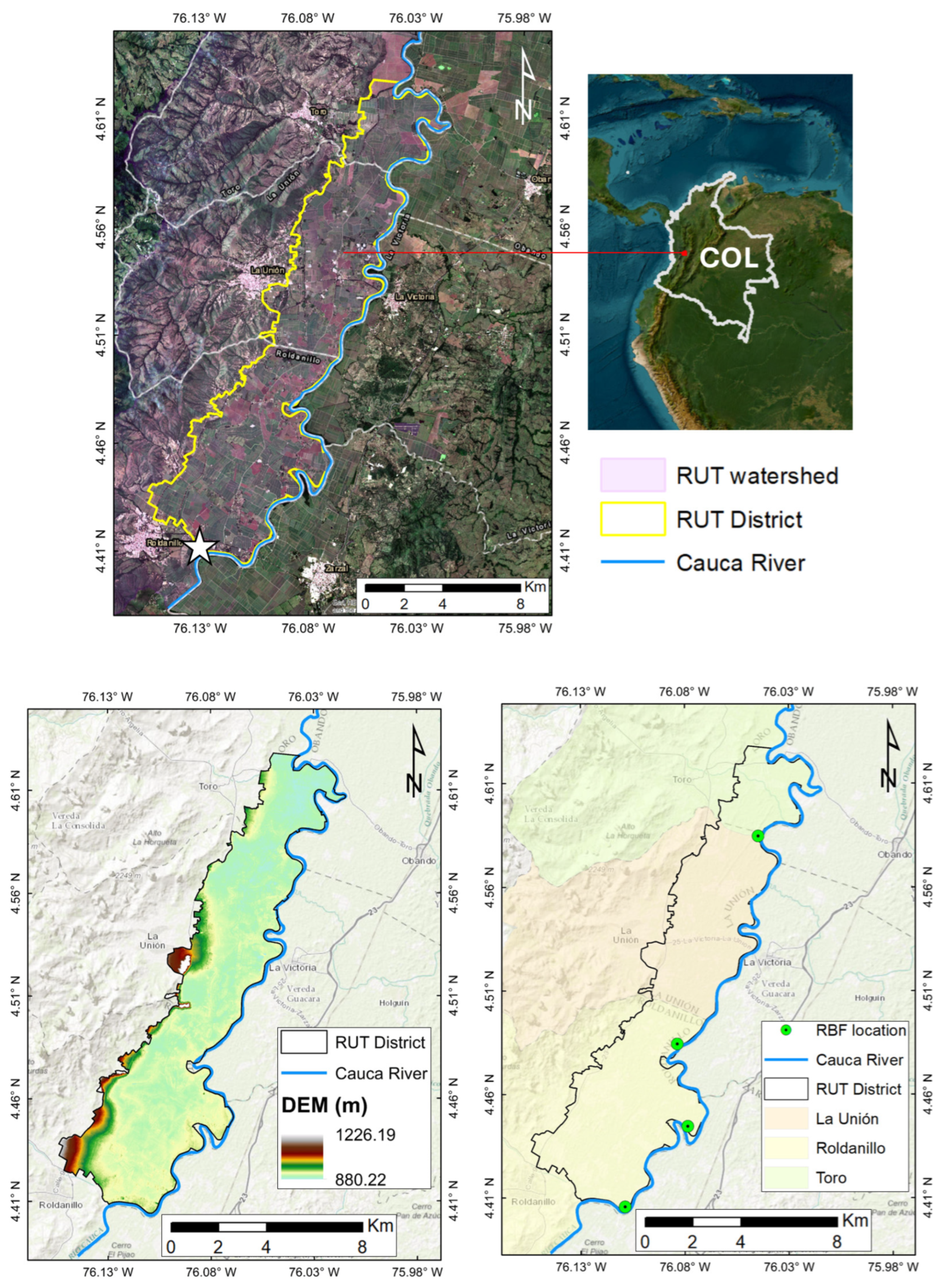

6. Colombian Context: The RUT District

6.1. Regional Setting and Suitability for RBF

6.2. Source Water Quality, Irrigation Constraints, and the Role of RBF

6.3. Hydrogeology and Soils: River–Aquifer Connectivity and Constraints

6.4. Conceptual Design, Scaling, and Monitoring (RBF Pilot to District Level)

7. Challenges

7.1. Climatic and Seasonal Variability

7.2. Temperature Effects on Biotransformation and Redox Stability

7.3. Sediment and Biofilm Clogging Dynamics

7.4. Extreme Turbidity Events and Pretreatment Vulnerabilities

8. Future Research Directions and Recommendations

8.1. Pilot-Scale Validation and Core Design Variables

8.2. Long-Term Soil and Nutrient Dynamics Under RBF Irrigation

8.3. Geographic and Functional Gaps in Current Research

8.4. Monitoring and Modeling Tools for Predictive Capacity

9. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mondal, K.; Chowdhury, M.; Dutta, S.; Satpute, A.N.; Jha, A.; Khose, S.; Gupta, V.; Das, S. Synergising Agricultural Systems: A Critical Review of the Interdependencies within the Water-Energy-Food Nexus for Sustainable Futures. Water-Energy Nexus 2025, 8, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.F.; Pavelic, P.; Sikka, A.; Krishnan, S.; Dodiya, M.; Bhadaliya, P.; Joshi, V. Energy Consumption as a Proxy to Estimate Groundwater Abstraction in Irrigation. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 101035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Chen, W.; Li, B.; Cao, E.; Li, Y.; Sun, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y. Reducing Fouling and Emitter Clogging in Saline Water Drip Irrigation Systems by Choosing Suitable Nitrogen Fertilizer. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 12, 101254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, B.; Kumar, S.; Purchase, D.; Bharagava, R.N.; Dutta, V. Practice of Wastewater Irrigation and Its Impacts on Human Health and Environment: A State of the Art. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 2181–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Puig-Bargués, J.; Ma, C.; Xiao, Y.; Maitusong, M.; Li, Y. Influence and Selection of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Compound Fertilizers on Emitter Clogging Using Brackish Water in Drip Irrigation Systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 291, 108644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, C.; Lorenzen, G.; Hülshoff, I.; Grützmacher, G.; Ronghang, M.; Pekdeger, A. Vulnerability of Bank Filtration Systems to Climate Change. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.K.A.; Marhaba, T.F. Review on River Bank Filtration as an in Situ Water Treatment Process. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2017, 19, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaiyu, L.; Yan, M.; Hao, G.; Shihong, G.; Yanqun, Z.; Guangyong, L.; Feng, W. The Hydraulic Performance and Clogging Characteristics of a Subsurface Drip Irrigation System Operating for Five Years in the North China Plain. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliva, R.G. Riverbank Filtration. In Anthropogenic Aquifer Recharge; Springer Hydrogeology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 647–682. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, V.; Greskowiak, J.; Asmuß, T.; Bremermann, R.; Taute, T.; Massmann, G. Temperature Dependent Redox Zonation and Attenuation of Wastewater-Derived Organic Micropollutants in the Hyporheic Zone. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 482–483, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, X.; Jin, H. A Comprehensive Review of Riverbank Filtration Technology for Water Treatment. Water 2025, 17, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf von Rohr, M.; Hering, J.G.; Kohler, H.P.E.; von Gunten, U. Column Studies to Assess the Effects of Climate Variables on Redox Processes during Riverbank Filtration. Water Res. 2014, 61, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, R.L.; Dash, R.R.; Pradhan, P.K.; Das, P. Effect of Hydrogeological Factors on Removal of Turbidity during River Bank Filtration: Laboratory and Field Studies. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlucinar, K.G.; Handl, S.; Allabashi, R.; Causon, T.; Troyer, C.; Mayr, E.; Perfler, R.; Hann, S. Non-Targeted Analysis with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry for Investigation of Riverbank Filtration Processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 64568–64581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargha, M.; Róka, E.; Erdélyi, N.; Németh, K.; Nagy-Kovács, Z.; Kós, P.B.; Engloner, A.I. From Source to Tap: Tracking Microbial Diversity in a Riverbank Filtration-Based Drinking Water Supply System under Changing Hydrological Regimes. Diversity 2023, 15, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Bresciani, E.; An, S.; Wallis, I.; Post, V.; Lee, S.; Kang, P.K. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Iron and Sulfate Concentrations during Riverbank Filtration: Field Observations and Reactive Transport Modeling. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2020, 234, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangre, N.; Sinha, J.; Raj, J.; Kamalkant. Estimation of Crop Water Requirement of Kharif Maize Crop Using CROPWAT 8.0 Model in Bilaspur District. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmecke, M.; Fries, E.; Schulte, C. Regulating Water Reuse for Agricultural Irrigation: Risks Related to Organic Micro-Contaminants. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Moshe, S.; Weisbrod, N.; Barquero, F.; Sallwey, J.; Orgad, O.; Furman, A. On the Role of Operational Dynamics in Biogeochemical Efficiency of a Soil Aquifer Treatment System. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2020, 24, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Zhang, P.; Ma, Z.P.; Ma, Z.B.; Wang, J.J.; Tang, Y.Y.; Chen, H. Coupling Sprinkler Freshwater Irrigation with Vegetable Species Selection as a Sustainable Approach for Agricultural Production in Farmlands with a History of 50-Year Wastewater Irrigation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 414, 125576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnitz, W.D.; Clancy, J.L.; Whitteberry, B.L.; Vogt, J.A. RBF as a Microbial Treatment Process. J. Am. Water Work. Assoc. 2003, 95, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, I.; Abbas, M.; Bassouny, M.; Gameel, A.; Abbas, H. Indirect Impacts of Irrigation with Low Quality Water on the Environmental Safety. Egypt. J. Soil Sci. 2019, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschneider, A.A.; Haralampides, K.A.; MacQuarrie, K.T.B. River Sediment and Flow Characteristics near a Bank Filtration Water Supply: Implications for Riverbed Clogging. J. Hydrol. 2007, 344, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Su, X.; Wan, Y.; Lyu, H.; Dong, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y. Quantifying the Effect of the Nitrogen Biogeochemical Processes on the Distribution of Ammonium in the Riverbank Filtration System. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Bolaños, J.A.; Echeverri-Sánchez, A.F.; Reyes-Trujillo, A.; del Mar Carreño-Sánchez, M.; Jaramillo-Llorente, M.F.; Rivera-Caicedo, J.P. In Situ Hyperspectral Reflectance Sensing for Mixed Water Quality Monitoring: Insights from the RUT Agricultural Irrigation District. Water 2025, 17, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Filho, J.A.A.; da Cruz, H.M.; Fernandes, B.S.; Motteran, F.; de Paiva, A.L.R.; Pereira Cabral, J.J.d.S. Efficiency of the Bank Filtration Technique for Diclofenac Removal: A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 300, 118916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Teng, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Zuo, R.; Li, J.; Chen, H. Riverbank Filtration in China: A Review and Perspective. J. Hydrol. 2016, 541, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Liu, Y.; Su, X.; Tong, S.; Jiang, M. Aquifer Exploitation Potential at a Riverbank Filtration Site Based on Spatiotemporal Variations in Riverbed Hydraulic Conductivity. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 41, 101068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn, E. Hydrogeological Issues of Riverbank Filtration—A Review. In Riverbank Filtration: Understanding Contaminant Biogeochemistry and Pathogen Removal; Ray, C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 14, pp. 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Zuo, R.; Wang, J.-S.; Li, Q.; Du, C.; Liu, X.; Chen, M. Response of the Redox Species and Indigenous Microbial Community to Seasonal Groundwater Fluctuation from a Typical Riverbank Filtration Site in Northeast China. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 159, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, H.; Schubert, J.; Ray, C. Conceptual Design of Riverbank Filtration Systems. In Riverbank Filtration; Ray, C., Melin, G., Linsky, R.B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; Volume 43, pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Umar, D.A.; Ramli, M.F.; Aris, A.Z.; Sulaiman, W.N.A.; Kura, N.U.; Tukur, A.I. An Overview Assessment of the Effectiveness and Global Popularity of Some Methods Used in Measuring Riverbank Filtration. J. Hydrol. 2017, 550, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaty, I.; Saleh, O.K.; Ghanayem, H.M.; Grischek, T.; Zelenakova, M. Assessment of Hydrological, Geohydraulic and Operational Conditions at a Riverbank Filtration Site at Embaba, Cairo Using Flow and Transport Modeling. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharudin, F.; Zailani, I.; Hamzah, N.; Mohd Zaki, Z.Z.; Mohamad, I.N. Assessment of River Water Quality Improvement Due to Riverbank Filtration (RBF) Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Civil and Environmental Engineering (ISCEE 2022), Online, 2–4 October 2022; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2023; Volume 1205, p. 012008. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, C.; Jasperse, J.; Grischek, T. Bank Filtration as Natural Filtration. In Drinking Water Treatment: Strategies for Sustainability; Ray, C., Jain, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 93–158. [Google Scholar]

- Labelle, L.; Baudron, P.; Barbecot, F.; Bichai, F.; Masse-Dufresne, J. Identification of Riverbank Filtration Sites at Watershed Scale: A Geochemical and Isotopic Framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 160964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Hamm, S.Y.; Cheong, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Ko, E.J.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, S.I. Characterizing Riverbank-Filtered Water and River Water Qualities at a Site in the Lower Nakdong River Basin, Republic of Korea. J. Hydrol. 2009, 376, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaty, I.; Saleh, O.K.; Ghanayem, H.M.; John, A.P.; Straface, S. Investigating and Improving Natural Treatment Processes by Riverbank Filtration in Egypt. In Groundwater in Arid and Semi-Arid Areas; Earth and Environmental Sciences Library; Ali, S., Armanuos, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 341–368. [Google Scholar]

- Srisuk, K.; Archwichai, L.; Pholkern, K.; Saraphirom, P.; Chusanatus, S.; Munyou, S. Groundwater Resources Development by Riverbank Filtration Technology in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Rural Dev. 2012, 3, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdouh, H.; Wahaab, R.A.; Khalifa, A.; Elalfy, E. Studying the Effect of Design Parameters on Riverbank Filtration Performance for Drinking Water Supply in Egypt: A Case Study. Water Supply 2022, 22, 3325–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C.; Hubbard, S.S.; Florsheim, J.; Rosenberry, D.; Borglin, S.; Trotta, M.; Seymour, D. Riverbed Clogging Associated with a California Riverbank Filtration System: An Assessment of Mechanisms and Monitoring Approaches. J. Hydrol. 2015, 529, 1740–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, C.; Grischek, T.; Ronghang, M.; Mehrotra, I.; Kumar, P.; Ghosh, N.; Satyaji-Rao, Y.; Chakraborty, B.; Patwal, P.; Kimothi, P. Overview of Bank Filtration in India and the Need for Flood-Proof RBF Systems. In Natural Water Treatment Systems for Safe and Sustainable Water Supply in the Indian Context; Wintgens, T., Nättörp, A., Elango, L., Asolekar, S., Eds.; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2016; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, C.M.; David Ng, K.M.; Richard Ooi, H.H.; Ismail, W.M.Z.W. Malaysia’s Largest River Bank Filtration and Ultrafiltration Systems for Municipal Drinking Water Production. Water Pract. Technol. 2015, 10, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pholkern, K.; Srisuk, K.; Grischek, T.; Soares, M.; Schäfer, S.; Archwichai, L.; Saraphirom, P.; Pavelic, P.; Wirojanagud, W. Riverbed Clogging Experiments at Potential River Bank Filtration Sites along the Ping River, Chiang Mai, Thailand. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 7699–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.A.; Cabral, J.J.S.P.; Paiva, A.L.R.; Molica, R.J.R. Application of Bank Filtration Technology for Water Quality Improvement in a Warm Climate: A Case Study at Beberibe River in Brazil. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 2012, 61, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.P.; Van Halem, D.; Rietveld, L. Riverbank Filtration for the Treatment of Highly Turbid Colombian Rivers. Drink Water Eng. Sci. 2017, 10, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdélyi, N.; Gere, D.; Fekete, E.; Nyiri, G.; Engloner, A.; Tóth, A.; Madarász, T.; Szűcs, P.; Nagy-Kovács, Z.Á.; Pándics, T.; et al. Transport Model-Based Method for Estimating Micropollutant Removal Efficiency in Riverbank Filtration. Water Res. 2025, 275, 123194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yuan, Z.; Lyu, H.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Su, X. Response of Redox Zoning and Microbial Community Structure in Riverbed Sediments to the Riverbed Scouring during Bank Filtration. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covatti, G.; Grischek, T. Sources and Behavior of Ammonium during Riverbank Filtration. Water Res. 2021, 191, 116788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusiak, M.; Dragon, K.; Gorski, J.; Kruc-Fijałkowska, R.; Przybylek, J. Surface Water and Groundwater Interaction at Long-Term Exploited Riverbank Filtration Site Based on Groundwater Flow Modelling (Mosina-Krajkowo, Poland). J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 37, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grischek, T.; Ray, C. Bank Filtration as Managed Surface-Groundwater Interaction. Int. J. Water 2009, 5, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Hu, B.X.; Su, X. Migration and Transformation Mechanisms of Iron and Manganese during River Infiltration Affected by the Changes in Riverbed Sediment Thickness. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 132030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Zhao, C.; Cui, J.; Du, C.; Tian, Z.; Shi, Y.; et al. Effect of Microbial Network Complexity and Stability on Nitrogen and Sulfur Pollutant Removal during Sediment Remediation in Rivers Affected by Combined Sewer Overflows. Chemosphere 2023, 331, 138832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, M.; Oswald, S.E.; Schäfferling, R.; Lensing, H.J. Temperature-Dependent Redox Zonation, Nitrate Removal and Attenuation of Organic Micropollutants during Bank Filtration. Water Res. 2019, 162, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Moghadam, H.R.; Mahmoodlu, M.G.; Jandaghi, N.; Heshmatpour, A.; Seyed, M. River Bank Filtration for Sustainable Water Supply on Gorganroud River, Iran. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuis, R.; De Cesare, G. The Clogging of Riverbeds: A Review of the Physical Processes. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2023, 239, 104374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zuo, R.; Brusseau, M.L.; Wang, J.S.; Liu, X.; Du, C.; Zhai, Y.; Teng, Y. Groundwater Pollution Containing Ammonium, Iron and Manganese in a Riverbank Filtration System: Effects of Dynamic Geochemical Conditions and Microbial Responses. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 4175–4189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Jin, G.; Tang, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, M. Ammonium (NH4+) Transport Processes in the Riverbank under Varying Hydrologic Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 826, 154097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberry, D.O.; Healy, R.W. Influence of a Thin Veneer of Low-Hydraulic-Conductivity Sediment on Modelled Exchange between River Water and Groundwater in Response to Induced Infiltration. Hydrol. Process. 2012, 26, 544–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, S.; Bahar, A.; Aziz, Z.A.; Suratman, S. Modelling Contaminant Transport for Pumping Wells in Riverbank Filtration Systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 165, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyaji Rao, Y.R.; Vijay, T.; Siva Prasad, Y.; Singh, S. Development of River Bank Filtration (RBF) Well in Saline Coastal Aquifer. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 37, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blavier, J.; Verbanck, M.A.; Craddock, F.; Liégeois, S.; Latinis, D.; Gargouri, L.; Flores Rua, G.; Debaste, F.; Haut, B. Investigation of Riverbed Filtration Systems on the Parapeti River, Bolivia. J. Water Process Eng. 2014, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Mehrotra, I.; Gupta, A.; Kumari, S. Riverbank Filtration: A Sustainable Process to Attenuate Contaminants during Drinking Water Production. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2018, 6, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, M.H.; Essam, A.; Elnaggar, A.Y.; Hussein, E.E. Heavy Metal Removal from the Water of the River Nile Using Riverbank Filtration. Water 2021, 13, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musche, F.; Sandhu, C.; Grischek, T.; Patwal, P.S.; Kimothi, P.C.; Heisler, A. A Field Study on the Construction of a Flood-Proof Riverbank Filtration Well in India—Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 31, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Knabe, D.; Engelhardt, I.; Droste, B.; Rohns, H.P.; Stumpp, C.; Ho, J.; Griebler, C. Dynamics of Pathogens and Fecal Indicators during Riverbank Filtration in Times of High and Low River Levels. Water Res. 2022, 209, 117961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Du, Q.; Teng, Y.; Zhai, Y. Design and Optimization of a Fully-Penetrating Riverbank Filtration Well Scheme at a Fully-Penetrating River Based on Analytical Methods. Water 2019, 11, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Pozdniakov, S.P.; Shestakov, V.M. Optimum Experimental Design of a Monitoring Network for Parameter Identification at Riverbank Well Fields. J. Hydrol. 2015, 523, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, S.; Satsangi, A.; Soamidas, V. River Bank Filtration System: Cost Effective Water Supply Alternative. In Water Safety, Security and Sustainability; Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications; Vaseashta, A., Maftei, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 565–579. [Google Scholar]

- Ascott, M.J.; Lapworth, D.J.; Gooddy, D.C.; Sage, R.C.; Karapanos, I. Impacts of Extreme Flooding on Riverbank Filtration Water Quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 554–555, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHadary, M.; Salah, A.; Mikhail, B.; Peters, R.W.; Ghanem, A.; Elansary, A.S.; Wahaab, R.A.; Mostafa, M.K. Challenges and Possible Solutions for Riverbank Filtration: Case Studies of Three Sites in Egypt. Air Soil Water Res. 2024, 17, 11786221241274480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaty, I.; Kuriqi, A.; Ganayem, H.M.; Ahmed, A.; Saleh, O.K.; Garrote, L. Assessment of Riverbank Filtration Performance for Climatic Change and a Growing Population. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1136313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Teng, Y.; Wang, G.; Du, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, G. Water Supply Safety of Riverbank Filtration Wells under the Impact of Surface Water-Groundwater Interaction: Evidence from Long-Term Field Pumping Tests. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 711, 135141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sophocleous, M. Interactions between Groundwater and Surface Water: The State of the Science. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.A.T.; Covatti, G.; Grischek, T. Methodology for Evaluation of Potential Sites for Large-Scale Riverbank Filtration. Hydrogeol. J. 2022, 30, 1701–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuy, V.K.; He, K.; Echigo, S.; Asada, Y.; Itoh, S. Impact of Biological Clogging and Pretreatments on the Operation of Soil Aquifer Treatments for Wastewater Reclamation. Water Cycle 2022, 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruisdijk, E.; Ros, J.F.; Ghosh, D.; Brehme, M.; Stuyfzand, P.J.; van Breukelen, B.M. Prevention of Well Clogging during Aquifer Storage of Turbid Tile Drainage Water Rich in Dissolved Organic Carbon and Nutrients. Hydrogeol. J. 2023, 31, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.; Weisbrod, N.; Bar-Zeev, E. Revisiting Soil Aquifer Treatment: Improving Biodegradation and Filtration Efficiency Using a Highly Porous Material. Water 2020, 12, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Brusseau, M.L. The Impact of Well-Field Configuration and Permeability Heterogeneity on Contaminant Mass Removal and Plume Persistence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 333, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misstear, B. Some Key Issues in the Design of Water Wells in Unconsolidated and Fractured Rock Aquifers. Acque Sotterr. Ital. J. Groundw. 2012, 1, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, W.; Nzeribe, B.N.; Liu, G.R.; Yao, G.; Crimi, M.; Rubasinghe, K.; Divine, C.; McDonough, J.; Wang, J. Modeling, Simulation and Analysis of Groundwater Flow Captured by the Horizontal Reactive Media Well Using the Cell-Based Smoothed Radial Point Interpolation Method. Adv. Water Resour. 2022, 160, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Lee, S.S. Development of Site Suitability Analysis System for Riverbank Filtration. Water Sci. Eng. 2010, 3, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Maeng, S.K.; Lee, K.H. Riverbank Filtration for the Water Supply on the Nakdong River, South Korea. Water 2019, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronghang, M.; Gupta, A.; Mehrotra, I.; Kumar, P.; Patwal, P.; Kumar, S.; Grischek, T.; Sandhu, C. Riverbank Filtration: A Case Study of Four Sites in the Hilly Regions of Uttarakhand, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2019, 5, 831–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberleitner, D.; Stütz, L.; Schulz, W.; Bergmann, A.; Achten, C. Seasonal Performance Assessment of Four Riverbank Filtration Sites by Combined Non-Target and Effect-Directed Analysis. Chemosphere 2020, 261, 127706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebl, A.; Wahaab, R.A.; Elazizy, I.; Hagras, M. Hydraulic Performance of Riverbank Filtration: Case Study West Sohag, Egypt. Water Supply 2022, 22, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaty, I.; Saleh, O.K.; Ghanayem, H.M.; Zeleňáková, M.; Kuriqi, A. Numerical Assessment of Riverbank Filtration Using Gravel Back Filter to Improve Water Quality in Arid Regions. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 1006930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paufler, S.; Grischek, T.; Benso, M.R.; Seidel, N.; Fischer, T. The Impact of River Discharge and Water Temperature on Manganese Release from the Riverbed during Riverbank Filtration: A Case Study from Dresden, Germany. Water 2018, 10, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Huang, Q.; Huang, G.; Xing, L. Modeling the Effects of Temperature on the Migration and Transformation of Nitrate during Riverbank Filtration Using HYDRUS-2D. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, R.; Xue, Z.; Wang, J.; Meng, L.; Zhao, X.; Pan, M.; Cai, W. Spatiotemporal Variations of Redox Conditions and Microbial Responses in a Typical River Bank Filtration System with High Fe2+ and Mn2+ Contents. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rashid, N.A.; Mohd Amin, M.F.; Mohd Arif Zainol, M.R.R.; Abustan, I.; Wan Mohtar, W.H.M.; Nizar Shamsuddin, M.K. Protection of Water: Robust of Artificial Barriers in Application of Riverbank Filtration Abstraction for Water Sustainability. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 322, 101034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.Z.; Adlan, N.; Selamat, M.R. A Study on the Potential of Riverbank Filtration for the Removal of Color, Iron, Turbidity and E. coli in Sungai Perak, Kota Lama Kiri, Kuala Kangsar, Perak, Malaysia. J. Teknol. 2015, 74, 2180–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondor, A.C.; Jakab, G.; Vancsik, A.; Filep, T.; Szeberényi, J.; Szabó, L.; Maász, G.; Ferincz, Á.; Dobosy, P.; Szalai, Z. Occurrence of Pharmaceuticals in the Danube and Drinking Water Wells: Efficiency of Riverbank Filtration. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 265, 114893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.N.A.; Covatti, G.; Nguyen, D.V.; Börnick, H.; Grischek, T. Feasibility of Riverbank Filtration in Vietnam. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.H.; Nuottimäki, K.; Jarva, J.; Dang, T.T.; Luoma, S.; Nguyen, K.H.; Pham, T.L.; Hoang, T.N.A. Use of a Groundwater Model to Evaluate Groundwater–Surface Water Interaction at a Riverbank Filtration Site: A Case Study in Binh Dinh, Vietnam. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, K.; Ślósarczyk, K.; Sitek, S. A Study of Riverbank Filtration Effectiveness in the Kępa Bogumiłowicka Well Field, Southern Poland. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 53, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masse-Dufresne, J.; Baudron, P.; Barbecot, F.; Pasquier, P.; Barbeau, B. Optimizing Short Time-Step Monitoring and Management Strategies Using Environmental Tracers at Flood-Affected Bank Filtration Sites. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 141429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boving, T.B.; Patil, K. Riverbank Filtration Technology at the Nexus of Water-Energy-Food. In Water-Energy-Food Nexus: Principles and Practices; Salam, A., Shrestha, S., Pandey, V.P., Anal, A.K., Eds.; American Geophysical Union and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, R.R.; Mehrotra, I.; Kumar, P.; Grischek, T. Study of Water Quality Improvements at a Riverbank Filtration Site along the Upper Course of the River Ganga, India. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 54, 2422–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.D.; Valencia-Zuluaga, V.; Echeverri-Sánchez, A.; Visscher, J.T.; Rietveld, L.C. Impact of Upflow Gravel Filtration on the Clogging Potential in Microirrigation. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, L.D. Determinación del Factor de Adherencia en Filtros de Grava de Flujo Ascendente en Capas. Ing. Compet. 2017, 19, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwimpaye, F.; Twagirayezu, G.; Agbamu, I.O.; Mazurkiewicz, K.; Jeż-Walkowiak, J. Riverbank Filtration: A Frontline Treatment Method for Surface and Groundwater—African Perspective. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 04015035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo-Uribe, M. Evaluation of the Potential for Riverbank Filtration in Colombia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, M.; Nordin Adlan, M.; Hana Mokhtar Kamal, N. Colour and E. coli Removals by Riverbed Filtration—A Physical Modelling Study at Different Filter Bed Depths and Inflow Rates. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2019, 11, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillefalk, M.; Massmann, G.; Nützmann, G.; Hilt, S. Potential Impacts of Induced Bank Filtration on Surface Water Quality: A Conceptual Framework for Future Research. Water 2018, 10, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Li, G. Occurrence and Distribution of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products (PPCPs) in Wastewater Related Riverbank Groundwater. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 821, 153372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačević, S.; Radišić, M.; Laušević, M.; Dimkić, M. Occurrence and Behavior of Selected Pharmaceuticals during Riverbank Filtration in the Republic of Serbia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 2075–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.; Grischek, T.; Boernick, H.; Velez, J.I. Evaluation of Riverbank Filtration in the Removal of Pesticides: An Approximation Using Column Experiments and Contaminant Transport Modeling. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollnitz, W.D.; Whitteberry, B.L.; Vogt, J.A. Riverbank Filtration: Induced Infiltration and Groundwater Quality. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2004, 96, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wan, Y.; Lyu, H.; Dong, W. Effects of Carbon Load on Nitrate Reduction during Riverbank Filtration: Field Monitoring and Batch Experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, L.; Chen, R.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.; Teng, Y. The Impact of Clogging Issues at a Riverbank Filtration Site in the Lalin River, NE, China: A Laboratory Column Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhai, Y.; Teng, Y. Microbial Response to Biogeochemical Profile in a Perpendicular Riverbank Filtration Site. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 244, 114070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regnery, J.; Barringer, J.; Wing, A.D.; Hoppe-Jones, C.; Teerlink, J.; Drewes, J.E. Start-up Performance of a Full-Scale Riverbank Filtration Site Regarding Removal of DOC, Nutrients, and Trace Organic Chemicals. Chemosphere 2015, 127, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, P.; Mehrotra, I.; Grischek, T. Impact of Riverbank Filtration on Treatment of Polluted River Water. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jaf, H. Assessment of Riverbank Filtration for Sirwan River in Iraq. Int. J. Energy Water Resour. 2022, 6, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, G.F.; de Paiva, A.L.R.; de Araújo Freitas, J.B.; da Silva Pereira Cabral, J.J.; Veras Albuquerque, T.B.; de Carvalho Filho, J.A.A. River Bank Filtration in Tropical Metropoles: Integrated Evaluation of Physical, Geochemical and Biochemical Interactions in Recife, NE Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 5803–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.A.; Cabral, J.J.S.P.; Rocha, F.J.S.; Paiva, A.L.R.; Sens, M.L.; Veras, T.B. Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. Removal by Bank Filtration at Beberibe River, Brazil. River Res. Appl. 2017, 33, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Su, X.; Zheng, S.; Tong, S.; Jiang, M. Hydrological and Biogeochemical Processes Controlling Riparian Groundwater Quantity and Quality during Riverbank Filtration. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 350, 124020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASORUT Asociación de Usuarios Del Distrito de Adecuación de Tierras de Los Municipios de Roldanillo, La Unión, Toro. Available online: https://asorut.com/ (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Castillo-Sánchez, L. Evaluación de los Peligros Asociados a la Calidad del Agua del Canal Interceptor Usada en Riego en el Distrito RUT. Master’s Thesis, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ASORUT (Asorut, La Unión, Colombia). Plan de Riego. Private Communication, 2024.

- Echeverri-Sánchez, A.-F. Modelo Metodológico para la Identificación del Riesgo de Salinización de Suelos en Distritos de Riego de Colombia. Caso de Estudio: Distrito RUT. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Sánchez, L. Zonificación del Comportamiento Espacial de las Propiedades Hidrodinámicas del Suelo en el Distrito de Riego RUT. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Palmira, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Yue, S.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, D.; Zhu, R. Effects of Flood Inundation on Biogeochemical Processes in Groundwater during Riverbank Filtration. J. Hydrol. 2023, 617, 129101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Preisendanz, H.E.; Veith, T.L.; Cibin, R.; Drohan, P.J. Riparian Buffer Effectiveness as a Function of Buffer Design and Input Loads. J. Environ. Qual. 2020, 49, 1599–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Drohan, P.J.; Cibin, R.; Preisendanz, H.E.; White, C.M.; Veith, T.L. Reallocating Crop Rotation Patterns Improves Water Quality and Maintains Crop Yield. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terán-Gómez, V.F.; Buitrago-Ramírez, A.M.; Echeverri-Sánchez, A.F.; Figueroa-Casas, A.; Benavides-Bolaños, J.A. Integrating AHP and GIS for Sustainable Surface Water Planning: Identifying Vulnerability to Agricultural Diffuse Pollution in the Guachal River Watershed. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Country, Name of the River(s) | Number of Wells | Water Production (m3/day) | Installed Capacity of Well Pumps (m3/day) | Distance Between Wells (m) | Distance from the Well to the River (m) | Depth of the Well (m) | Clogging Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [41] | Egypt, Bahr Yusuf | 4 | 5184 | 10,386 | 5–15 | 5.0–75.0 | - | Yes-physical |

| [72] | Egypt, Nile River | 7 | - | 2592 | 20 | 15–20 | - | - |

| [39] | Egypt, Nile River | 6 | - | 14,000–21,000 | - | 10–15 | 54 | Yes-physical |

| [87] | Egypt, Nile River | 3 | 3024 | 3024 | 8 | 8 | 36 | - |

| [88] | Egypt, Nile River | 6 | - | 3600 | - | 10–15 | 24–91 | Yes-physical |

| [34] | Egypt, Nile River | 6 | 21,600 | 21,600 | - | 10–15 | 25–150 | Yes-physical |

| [67] | Germany, Rhine River | 11 | 7728 | - | 17–40.2 | 32.2 | - | Yes-physical |

| [89] | Germany, Elbe River | 72 | 15,500 | 36,000 | - | 95 | - | Yes-physical |

| [90] | China, Qingyang River | 3 | - | - | - | 2.5–13 | 12 | - |

| [68] | China, Songhua River | 7–11 | 23,000 | - | - | 50 | 50 | - |

| [91] | China, Songhua River | 3 | 9600 | 9600 | 20 | - | 50 | - |

| [59] | China, Fuliji River | 5 | - | - | - | 4.9–114.6 | 10.5–14.2 | Yes-physical |

| [16] | South Korea, Nakdong River | 3 | 500 | 237.5–25 | 14.8–15.1 | 15.2–18.7 | 9 | - |

| [84] | South Korea, Nakdong River | 13 | 280,000 | 280,000 | - | 30 | 18–27 | - |

| [92] | Malaysia, Sungai Semerak River | 13 | 1240–3070 | 10–25,000 | - | - | - | Yes-physical |

| [93] | Malaysia, Sungai Perak River | 7 | 2694.4 | 2694.4 | 8–50 | 10 | 13 | - |

| [94] | Hungary, Danube River | 756 | 456,000–161,000 | 456,000–161,000 | - | 16.5–813 | - | - |

| [48] | Hungary, Danube River | - | 447,945 | - | 5500–7000 | 60–395 | - | - |

| [95] | Vietnam, Red River and Dai An River | 17 | - | - | 20–500 | 300–1500 (Hanoi); 20–500 (Binh Dinh) | 10–30 | Yes-physical |

| [96] | Vietnam, Dai An River | 8 | - | 5300 | - | 38 | 7.6–20.5 | - |

| [51] | Poland, Warta River | - | 46,732.5 | 8571.4 | - | - | 12 | Yes-physical |

| [97] | Poland, Dunajec River | 11 | 8476; 10,000 | - | - | 110–350 | - | - |

| [23] | Canada, Saint John River | 8 | 26,000 | 28,800 | - | 400 | 32.0–49.4 | Yes-physical |

| [98] | Canada, Ottawa River | 8 | ≥1000 | 4000–7500 | - | - | 45,950 | - |

| [21] | USA, Great Miami River | 10 | 80,000 | 57,000–114,000 | - | 15–247 | 25–57 | - |

| [42] | USA, Russian River | 6 | 348,000 | 348,000 | 80 | - | 20 | Yes-biological |

| [99] | Jordan, Zarqa River | 6 | 88.8 | - | 25 | 5–25 | 16.5–21.6 | Yes-biological |

| [100] | India, Ganga River | 25 | - | - | - | 4–250 | 6.5–10.7 | Yes-biological |

| [69] | Russia, Kuybyshev Reservoir | 28 | 1440–2990 | - | 200 | 150–250 | 60–96 | Yes-physical |

| Reference | Total Coliforms and/or Fecal Coliforms | Turbidity | NH4+, NO3− or Other N Species | Removal Rates | Redox Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [93] | E. coli and total coliforms monitored; effective E. coli removal (~100%) and likely similar for total coliforms; 72 h monitoring. | Removal 98.78%; pumped water 0.3–0.4 NTU; Columbia River water 1.0–5.0 NTU. | - | ~100% E. coli removal | Fe oxides mobilized under reducing conditions, adsorbed/precipitated under oxidizing; Fe3+ in alluvium formed in reduced state; higher Fe in river water linked to anthropogenic sources; pH and ionic strength influence removal. |

| [48] | - | Southern wells 0.38–5.1 NTU; Northern wells 0.1 NTU; p < 0.001. | NO3− highest in NW1; NO3− and Cl− higher in Northern wells; NH4+, NO2−, Mn correlated with high redox potential; NO3− correlated with atrazine in NW1–NW2. | Organic micropollutants (OMP) removal 4–97% depending on compound; NO3− correlated with atrazine presence. | High Fe, Mn, NH4+, NO2− at high redox potential; Northern wells had higher redox potential than Southern; OMP removal higher in oxidative conditions. |

| [55] | - | - | NO3− in river avg. 5.2 mg/L; seasonal peak 9.4 mg/L (winter), low 4.1 mg/L (summer); NO3− removal 6–89% between river and well; seasonal temperature explained 81% variance in NO3−. | OMP removal varied up to 3 orders of magnitude; diclofenac and sulfamethoxazole removal strongly temp- and redox-dependent; residence time and microbial dynamics influenced removal. | O2 fully depleted in summer; Mn2+ detected in autumn with O2 depletion and NO3− = 0; Mn2+ and Fe2+ detected during anoxic/nitrate-depleted periods (June 2016–January 2017); SO42− ≈ 187–194 mg/L in river. |

| [56] | 150–1100 MPN/100 mL in river; ~98% removal in RBF. | 25.4 NTU (river) to 0.58 NTU (RBF); 97.7% removal. | NH3 removal 39.6%, NO2− 12%, NO3− 5.4%; NH3 oxidation rate higher than NO2−, NO3−. | Fe 19.2%, Mn 22.2%, NH3 39.6%, NO2− 12%, NO3− 5.4%. | Fe and Mn decreased from river to well; Fe-reducing/Fe-oxidizing bacteria noted; redox changes linked to ion reduction and color variation. |

| [110] | - | RBF average turbidity < 1.0 NTU with occasional spikes up to 6.0 NTU; some wells show sporadic variations over two orders of magnitude; production wells generally < 0.3 NTU with occasional spikes; higher turbidity observed in new wells due to incomplete development. | - | Pathogen surrogate reduction > 3.5 log. | - |

| [21] | None detected in RBF; indicates effective pathogen removal. | Reduced below 1 NTU with 2 ft filtration; maintained <0.3 NTU; ≥4-log reduction. | - | ≥4-log turbidity reduction; 100% removal of Giardia/Cryptosporidium in groundwater. | - |

| [36] | - | <0.5 NTU post-peak flow; 4.5–6.5 log removal over 30 days. | NO3− reduction to NH4+ under anoxic conditions. | TOC > 50% removal; DOC reduced; pathogens removed 4.5–6.5 logs (30 days), ~2 logs (24 h), ~8 logs (25 days). | Fe & Mn sensitive to redox changes; sulfate reduction observed under strong reducing conditions; NO3− acts as electron acceptor; anoxic conditions reported. |

| [78] | - | 2–165 NTU; >20 NTU reduced injectivity; guideline 1–5 NTU; automated flushing kept <20 NTU. | NH4+ oxidizers (Nitrosoarchaeum); NO3− as main N source; denitrifiers, nitrite oxidizers; Sulfurimonas, Sulfuricurvum indicated NO3− reduction with S and H oxidation. | - | Strongly anoxic; Fe2+ = 3.5 mg/L, Mn2+ = 0.58 mg/L during standstill; native groundwater Fe2+ = 9.5–39 mg/L; SO4-reducing and methanogenic (CH4 = 11–40 mg/L). |

| [97] | - | Turbidity up to 25.5 NTU (2012–2022); high values due to corrosion/encrustation; RBF turbidity removal up to 100%. | NH4+ in surface water: <0.05–7.25 mg/L; groundwater < 0.05–0.26 mg/L; NO3− in surface water: 0.22–11.2 mg/L; groundwater NO3− reduced in warmer months via denitrification. | Mn removal ~40%; color removal ~80%; NO3− removal up to 97% in summer; stable groundwater composition maintained. | Fe and Mn levels influenced by pH and redox; periodic elevated Fe/Mn in river; redox-driven (re)oxidation, sorption, precipitation control mobility. |

| [111] | - | - | Groundwater NO3− removal mainly via DNF; DNRA causes NH4+ retention; seasonal NO3− reduction affects NH4+ enrichment; NO3−, NO2−, NH4+ analyzed by continuous flow. | NH4+-N enrichment higher in wet season; DOC decay rate: 0.1996 mmol L−1 m−1 (wet) vs. 0.022 mmol L−1 m−1 (dry); more effective DOC removal in wet season. | Sequential Mn4+ and Fe3+ oxide reduction indicates specific redox zonation influenced by OC and nutrient fluxes; anaerobic reduction environments favor DNRA/DNF processes. |

| [112] | - | Turbidity ratio decreased 59.4–96.9% after 96 h; highest at 80 cm (79.6–96.9%), lowest at >10 cm (59.4–78.6%); r = −0.95 (p < 0.01) correlation between turbidity and permeability at 10 cm. | NH4+ decreased 60.6–89.1% in first 120 h; additional 1.7–2.0% drop between 144–168 h; steady state at 216 h; COD, NO3−, Mn2+ also analyzed; chemical clogging indicated by NH4+ increases during intervals. | - | Oxygenated water infiltration altered Fe and Mn concentrations; higher inflow reduced Mn4+, Mn2+, Fe2+, total Fe via oxidation; precipitation of Fe hydroxides linked to chemical clogging; redox reactions key for Fe/Mn removal/transformation. |

| [113] | - | - | NH4+: 0.4–3.2 mg/kg; NO2−: 0–6.88 mg/kg; NO3−: 1.32–42.8 mg/kg; Nitrospirae oxidizes NO2− to NO3− aiding NH4+ biotransformation; ammonium/nitrates impact microbial structure and biogeochemical processes. | - | Redox conditions affected microbial diversity and distribution; mineral dissolution increasing Fe (6.9–31.2 g/kg) and Mn (163–678 mg/kg) in groundwater; favorable for Fe-oxidizing and Mn-oxidizing bacteria; sediment pH weakly alkaline. |

| [114] | - | - | River NH4+: 5.8 ± 1.4 mg/L (winter), 1.0 ± 0.6 mg/L (summer); RBF 90% NH4+: 0.6 ± 0.4 mg/L, 0.4 ± 0.1 mg/L; NO3− decreased via denitrification (reducing conditions); no difference in NO3− removal between 2009 and 2012; NO3− attenuation sustained over 7 years. | DOC removal was 42 ± 8% when RBF contributed 90% of the water, and 54 ± 3% when RBF contributed 50%, with the higher apparent removal at 50% explained by dilution with landside groundwater. Removal of sulfamethoxazole, gemfibrozil, and diclofenac—was controlled by temperature and residence time, with higher efficiencies observed in summer. | Mn < 0.2 mg/L in RBF 50% wells (oxic); Mn in RBF 90%: 0.61 ± 0.24 mg/L (2009), 0.89 ± 0.13 mg/L (2012): reducing conditions; Fe < 1 mg/L in all wells (no strong reduction); redox influenced by microbial activity/electron acceptors. |

| [115] | River total coliforms: 2.3 × 103–1.5 × 106 MPN/100 mL; RBF filtrate: 4.3 × 104–7.5 × 104 MPN/100 mL (~2 log reduction). | River turbidity: 3.83–13.6 NTU (pre/post-monsoon), 70–180 NTU (monsoon); RBF bed filtration reduced turbidity. | - | DOC removal during pre-chlorination: 7–18%; RBF reduced DOC, color, UV-absorbance, and fecal coliforms by ~50% vs. direct pumping. | - |

| [116] | River: 660 CFU/100 mL; RBF: 0 CFU/100 mL. | River: 13.47 NTU; RBF: 0.3 NTU. | NO3− 1.38 mg/L (safe for human consumption). | - | - |

| [72] | Total coliform removal ~99%, meeting microbiological standards. | Turbidity reduced ~90% to safe levels for human consumption. | - | Microbiological ~99%. | Fe2+, Mn2+, Fe3+, Mn4+; Fe oxidized by atmospheric O2; Mn requires aeration; moderate redox potential: higher Fe/Mn; redox/pH changes affect oxidation rate. |

| [117] | Total/thermotolerant coliforms (MPN/100 mL, Colilert test); river: variable counts; pumped groundwater: complete removal. | River turbidity: 1.3–156 NTU; well water: 0.2–1.6 NTU; Brazilian limit: 5 NTU; long-term drop from 10–300 NTU to 0 NTU in groundwater. | NH4+ from fertilizers/domestic effluents; NO3− increased in aquifers (electron acceptor role); NO2− transitional N species; linked to OM degradation and nitrification. | - | - |

| [118] | Beberibe River: total coliforms ≥ 1600–≥160,000 NMP/100 mL; E. coli 280–≥160,000 NMP/100 mL; RBF removal: 99.9% in Ganges River, 95% in Nile River; production wells (e.g., Well A) 100% removal. | Turbidity reduction 99–99.9% (Haridwar, India); Beberibe River 16.3–158.0 NTU; wells much lower; suspended particulates reduced by porous medium filtration. | - | - | - |

| [119] | River water TC: 4240.8–7258.8 MPN/100 mL; E. coli: 23.8–42 MPN/100 mL; sediment removal at 0–20 cm: 85% TC, 56% E. coli; Citrobacter & Enterobacter = 10.57% soil bacteria; E. coli undetectable in groundwater. | - | NH4+-N in groundwater: 2.11 mg/L (dry), 2.66 mg/L (wet); NO3−-N in river: 1.74 mg/L (dry), 2.37 mg/L (wet); groundwater NO3−-N ≈ 0.6 mg/L; at 80 cm depth: NO3−-N = 0.13 mg/L (>94.5% removal). | 94.5% NO3− and 94% E. coli removed within 1 m of riverbed surface; 85% TC and 56% E. coli removed at 0–20 cm; Fe-Mn dissolution contributes to high groundwater Fe, Mn. | Shift from aerobic to anoxic; Mn reduction precedes Fe; Fe2+ increases from riverbed to aquifer; high NH4+ and DNRA observed; redox favors Fe/Mn release. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo-Sánchez, L.; Echeverri-Sánchez, A.F.; Sánchez Torres, L.D.; Quiroga-Rubiano, E.L.; Benavides-Bolaños, J.A. A Review of Riverbank Filtration with a Focus on Tropical Agriculture for Irrigation Water Supply. Water 2025, 17, 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213169

Castillo-Sánchez L, Echeverri-Sánchez AF, Sánchez Torres LD, Quiroga-Rubiano EL, Benavides-Bolaños JA. A Review of Riverbank Filtration with a Focus on Tropical Agriculture for Irrigation Water Supply. Water. 2025; 17(21):3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213169

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo-Sánchez, Leonardo, Andrés Fernando Echeverri-Sánchez, Luis Darío Sánchez Torres, Edgar Leonardo Quiroga-Rubiano, and Jhony Armando Benavides-Bolaños. 2025. "A Review of Riverbank Filtration with a Focus on Tropical Agriculture for Irrigation Water Supply" Water 17, no. 21: 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213169

APA StyleCastillo-Sánchez, L., Echeverri-Sánchez, A. F., Sánchez Torres, L. D., Quiroga-Rubiano, E. L., & Benavides-Bolaños, J. A. (2025). A Review of Riverbank Filtration with a Focus on Tropical Agriculture for Irrigation Water Supply. Water, 17(21), 3169. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17213169