Abstract

In this study, insoluble CaSO3 was applied to replace soluble sulfite/bisulfite salt in the Fe(II)-activated sulfite/bisulfite [S(IV)] process for the efficient 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP) degradation. CaSO3 serves as a low-cost and slow-release source of S(IV), significantly improving S(IV) utilization compared to conventional soluble Na2SO3. The Fe(II)/CaSO3 system generated SO4•− and HO• through Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox cycling. Mechanistic studies confirmed SO4•− as the dominant reactive species, selectively attacking C-Br bonds and hydroxyl groups in TBP. Process optimization revealed effective performance under acidic conditions (pH 3.5–4.0) with minimal inhibition by common anions (Cl−, HCO3−). The reactive sites of TBP were identified through Fukui function calculations, and the degradation pathway was elucidated based on LC-MS analysis. Toxicity evaluation indicated reduced ecological risk of degradation intermediates due to debromination and benzene ring cleavage. This work provides a sustainable strategy for efficient TBP removal and detoxification in wastewater treatment with benefiting S(IV) utilization.

1. Introduction

With the rapid progress of industrialization, urbanization, and population expansion, discharges of industrial wastewater and municipal sewage have risen substantially. A considerable portion of industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and insufficiently treated urban wastewater are directly released into water bodies, leading to aggravated water pollution and further intensifying water scarcity concerns [1,2]. Trace contaminants such as halogenated aromatic compounds, pesticide residues, and pharmaceuticals persist in aquatic systems and pose significant long-term risks to human and ecological health due to their bioaccumulative potential, environmental persistence, and ecotoxicity [3,4]. Among them, 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP) is produced in the largest quantities and is frequently detected across various environmental matrices [5,6]. TBP bioaccumulates in organisms and has been increasingly identified in human blood, urine, and tissues [7]. Consequently, it is imperative to develop efficient and safe treatment technologies to mitigate the multifaceted risks that TBP and its transformation products pose to human and ecosystem health.

Among the treatment technologies for TBP, biological treatment methods exhibit relatively poor removal efficiency [8]. Physical adsorption methods face challenges such as limited adsorbent capacity and incomplete regeneration processes [9,10]. Membrane filtration is associated with issues like membrane fouling and clogging, which can lead to reduced treatment efficiency, as well as relatively high costs for membrane replacement and maintenance [11]. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) represent a category of environmentally friendly water treatment technologies. They efficiently degrade refractory organic pollutants by generating high reactive species, such as hydroxyl radicals (HO•), sulfate radicals (SO4•−), and chlorine radicals (Cl•) [12,13]. Among various AOPs, SO4•−-based AOPs have garnered extensive attention globally. However, the methods for activating persulfate to generate SO4•− possess several drawbacks: on one hand, residual persulfate in the reaction system can exhibit certain acute toxicity. On the other hand, when the target pollutant like TBP contains halogen elements, it can lead to the formation of highly carcinogenic halogenated disinfection byproducts [14,15]. Sulfite/bisulfite [S(IV)] is considered a preferable alternative to persulfate, as S(IV)-AOPs offer the following advantages: (1) Residual S(IV) after reaction in water can be removed through aeration [6]; (2) S(IV) is less expensive compared to persulfate; (3) The formation of brominated disinfection byproducts and bromate during the treatment of bromide-containing wastewater by S(IV)-AOPs is significantly minimal due to the strong reducing capacity of S(IV) [5].

While iron-activated S(IV) AOPs offer broad advantages for practical application, this method still presents challenges. When S(IV) was activated to generate free radicals, it also acts as a strong reducing agent [16]. Hence, S(IV) can compete with target pollutants for reactive species in the system, thereby reducing the utilization efficiency of chemicals and increasing treatment costs [17]. Although our previous research has demonstrated that batch dosing of S(IV) can enhance the efficacy of S(IV)-AOPs in degrading TBP [5], the operational process is complex. Thus, there is a need to develop more efficient S(IV) utilization techniques. Calcium sulfite (CaSO3), a byproduct of flue gas desulfurization, is low-cost and readily available [18,19]. Compared to Na2SO3, CaSO3 has a relatively low solubility in water (approximately 0.07 g/L H2O at 25 °C), endowing it with the ability to release S(IV) gradually, which can improve S(IV) utilization efficiency [17]. Based on these advantages, this study employs CaSO3 as a substitute for Na2SO3 to serve as the source of S(IV).

Herein, the primary objective of this study is to develop a method for enhanced S(IV) utilization efficiency in S(IV)-based AOPs, thereby improving the removal effectiveness of TBP. Firstly, the degradation efficiency of TBP in different S(IV)-AOPs was systematically compared to evaluate the feasibility of CaSO3 as a S(IV) source. The slow-release process of CaSO3 was elucidated by monitoring Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox cycle dynamics and real-time S(IV) concentration variation during the reaction. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy and chemical probe experiments were employed to identify the radical species (e.g., SO4•−, HO•) generated in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system [20]. Quenching experiments were further conducted to quantitatively analyze the oxidative contributions of different radicals and identify the dominant reactive species responsible for TBP degradation [21]. Additionally, the effects of key operational parameters, including chemical dosage, initial TBP concentration, solution pH, and dissolved oxygen, on the reaction kinetics were comprehensively investigated. To assess the practical applicability of the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system, the influences of natural organic matter (NOM) and common anions (e.g., Cl−, HCO3−) on TBP degradation were experimentally evaluated. Finally, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to identify intermediate products during TBP degradation, and toxicity evolution was assessed using computational toxicity prediction software Ecological Structure Activity Relationships (ECOSAR, Version 2.2). This study provides an effective strategy to address the low chemical utilization efficiency in S(IV)-AOPs and advances the development of water treatment technologies toward greater efficiency, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

All chemical reagents employed in this study conformed to at least the analytical grade standard to ensure the reliability of experimental results. The specific reagents and their details are as follows: 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP), with a purity of no less than 98%, was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China); calcium sulfite (CaSO3), having a purity of ≥90.0%, was supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Wuhan, China); ferric sulfate (Fe2(SO4)3), which had a purity of ≥99%, was obtained from Adamas (Shanghai, China); methyl alcohol, with a purity of ≥99.9%, was sourced from Tedia (Fairfield, OH, USA); acetic acid (CH3COOH, purity ≥ 99.0%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, purity ≥ 96.0%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, purity ≥ 96%), and ethyl alcohol (purity ≥ 95.0%) were all provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Wuhan, China). All experimental stock reagent solutions were prepared with 18.2 MΩ ultrapure water as solvent to avoid impurity introduction and subsequent reaction interference.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

All experiments for treating 2,4,6-tribromophenol (TBP)-contaminated water were performed on a programmable jar tester (TA6-1, Hengling, Wuhan, China), which was equipped with 500 mL beakers, mechanical stirrers, and a circulating water bath system. The experiment followed a two-stage process: oxidation and coagulation. First, 500 mL water samples containing 10 μM TBP were moved to the beakers. They were mechanically stirred to ensure uniformity, and the circulating water bath kept the solution temperature at 25 °C. Next, Fe2(SO4)3 was added, then the solution pH was adjusted. Finally, CaSO3 was added to start the oxidation reaction. It is important to note that throughout the entire experimental process, 1 M dilute sulfuric acid (H2SO4) solution and 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution were used for pH adjustment. No buffer solutions were added to the system to avoid potential interference with the reactions between the experimental reagents. To ensure accuracy and reproducibility, all the experiments were performed at least twice, and average values along with the standard deviation were presented in figures as error bars.

2.3. Analytic Methods

Turbidity was directly measured with a turbidimeter (WZB-175, Leici, Shanghai, China). TBP quantification was conducted via high-performance liquid chromatography (LC-15C, Shimadzu, Shanghai, China) equipped with an Agilent HC-C18 column (5 μm, 250 mm × 4.6 mm), under conditions of 25 °C column temperature, 50 μL injection volume, 290 nm detection wavelength, 1.0 mL min−1 flow rate, and a mobile phase of methanol, ultrapure water, and glacial acetic acid (85:15:1). The concentrations of Fe(II) and Fe(III) in the system were determined via the 1,10-phenanthroline spectrophotometric method (details in Text S1) [22], while the S(IV) concentration was measured using a colorimetric approach with 5,5-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) as the reagent [23]. Solution pH was analyzed with a pH meter (Model pHS-3C, Lei-ci, Shanghai, China), and dissolved oxygen (DO) content was detected using a DO meter (Model DO2000, YSI, Yellow Springs, OH, USA). For the intermediate products generated during TBP degradation, they were first extracted using a Cleaner S C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridge, then identified by a Q-Exactive hybrid quadrupole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer coupled with an Ultimate 3000 Complete Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography system (U-HPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap HRMs, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). To determine the reaction rate constants of TBP with SO4•− and HO•, the relative rate method was adopted, with ethanol (EtOH) and tert-butanol (TBA) used as chemical probes. Density functional theory (DFT) was conducted using Gaussian 09 at B3LYP/6–311G* basis set.

3. Results and Discussion

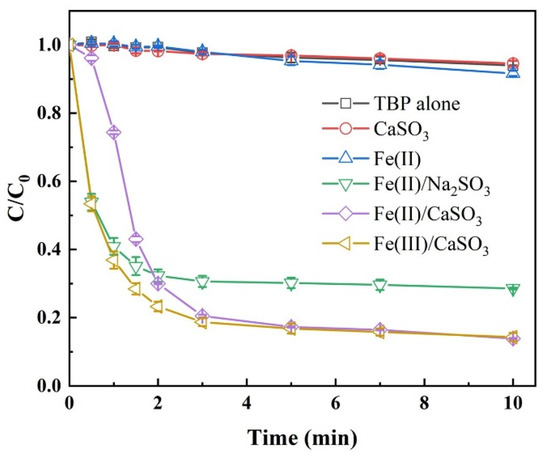

3.1. Comparison of Different Processes in TBP Degradation

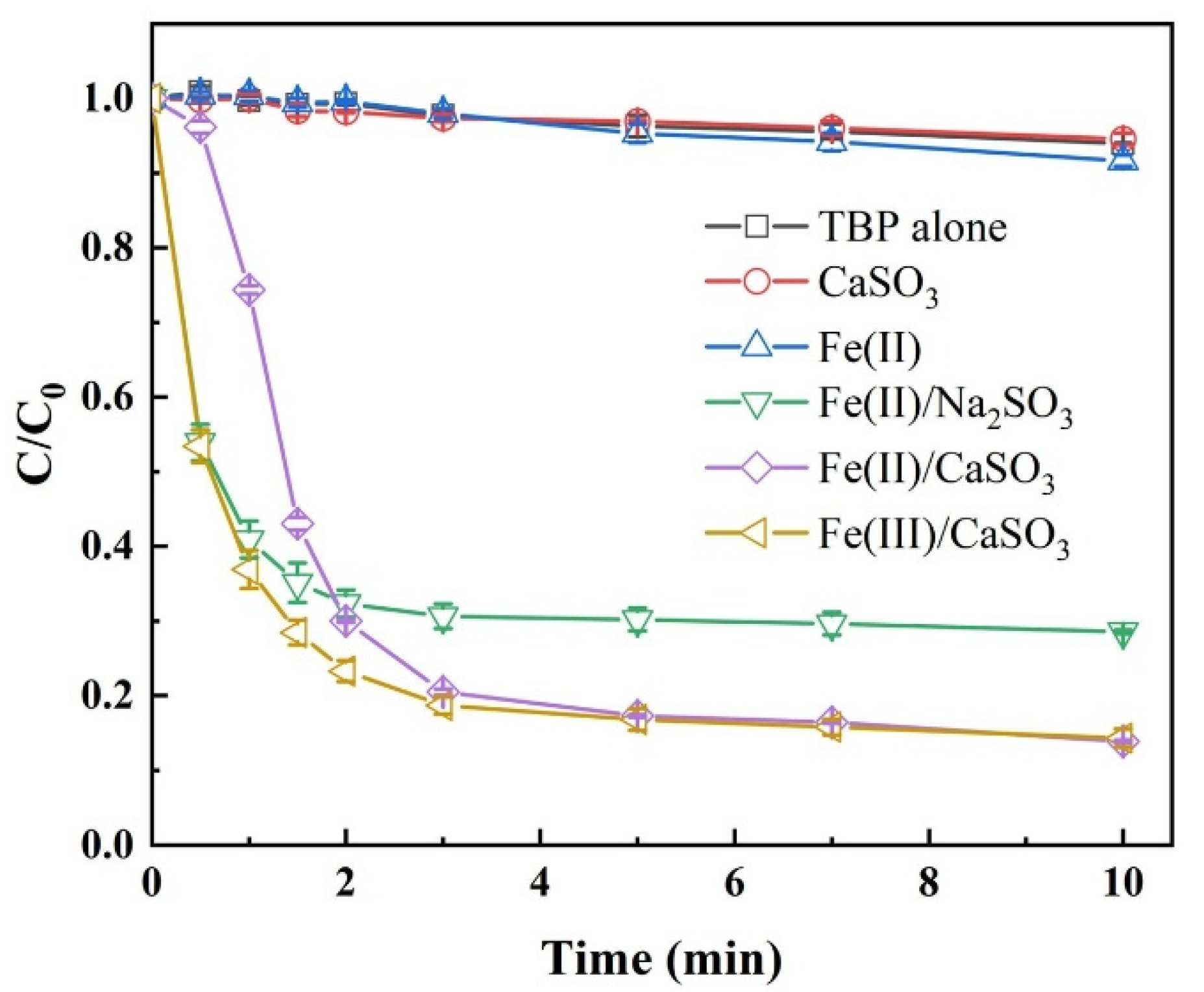

The degradation efficiency of TBP was first evaluated across various S(IV)-AOPs, as summarized in Figure 1. Control experiments including TBP alone, Fe(II) alone, and CaSO3 alone, all exhibited less than 10% degradation within 10 min, ruling out significant contributions from physical adsorption or volatilization. In the Fe(III)/CaSO3 and Fe(II)/CaSO3 systems, TBP degradation reached 85.7% and 86.1%, respectively, outperforming the Fe(II)/Na2SO3 system with 67.9% removal. These results indicate that substituting Na2SO3 with the slow-release CaSO3 significantly enhances contaminant removal efficiency in S(IV)-activated AOPs. The primary reactions occurring within the system are illustrated in Equations (1)–(8). It is noteworthy that within the first 30 s, TBP degradation was only 4.8% in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system compared to 46.6% in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system, suggesting a distinct initiation period of approximately 30 s in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system. This delay is likely due to the requirement for Fe2+ to first form a complex with HSO3− (as FeHSO3+), which then reacts with O2 to generate FeSO3+ [24], whereas Fe3+ directly reacts with HSO3− to form FeSO3+ in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system (Equation (3)). After 3 min, the performance of both systems became comparable. Given the similar reaction pathways and the lower cost of FeSO4, Fe(II) was selected over Fe(III) for subsequent experiments [25].

Figure 1.

Comparison of TBP degradation in different processes. Conditions: [TBP] = 10 μM, [Fe(III)] = [Fe(II)] = 50 µM, [CaSO3] = [Na2SO3] = 400 µM, initial pH 3.5, temperature 25 °C.

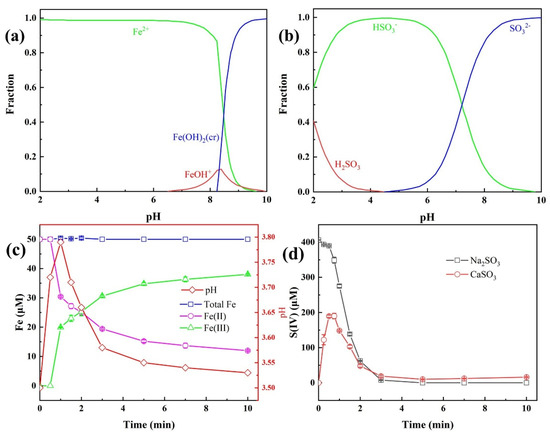

3.2. Quantitative Analysis of CaSO3 Slow-Release Process

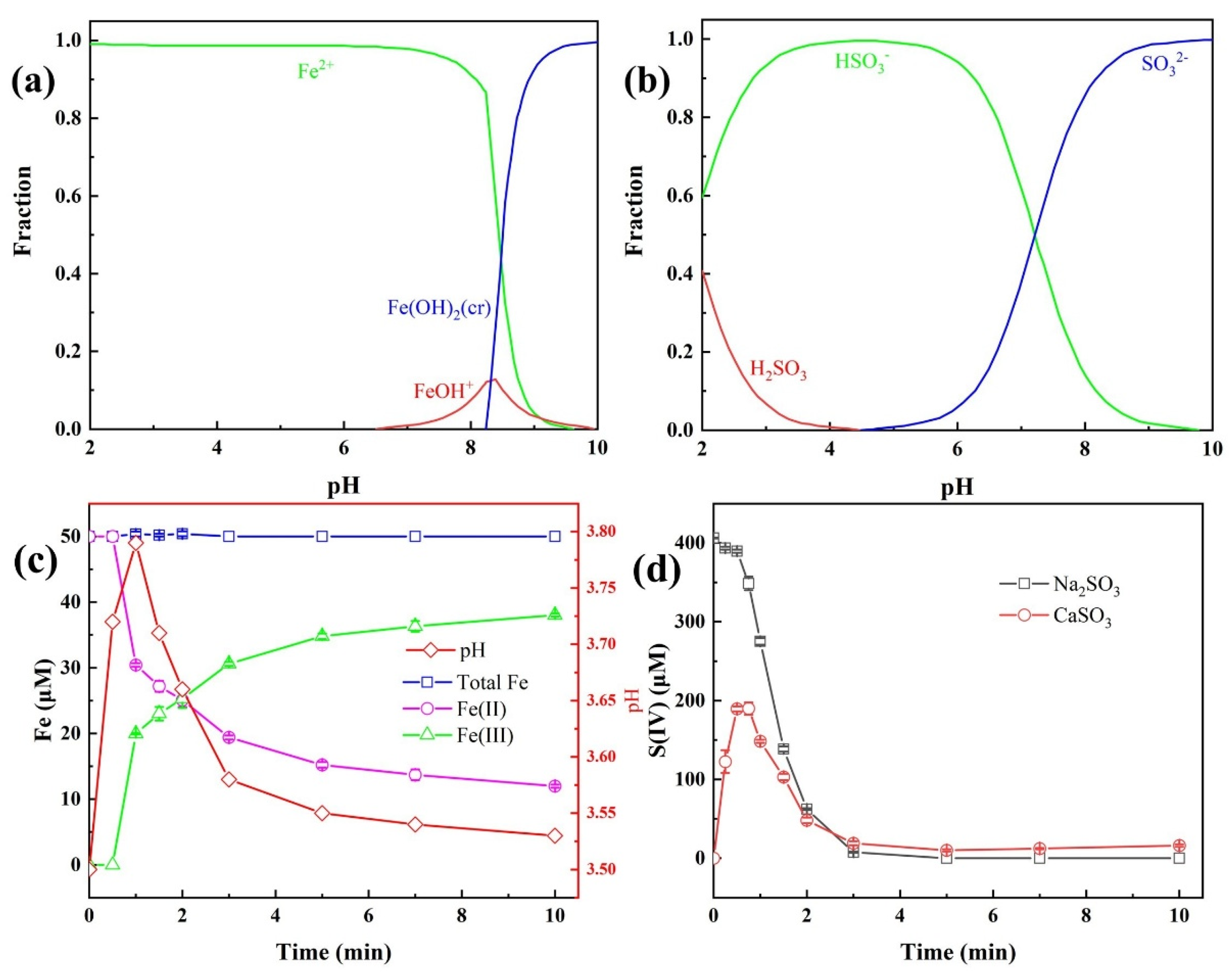

During the degradation of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system, CaSO3 undergoes sustained release of SO32−, which further reacts with H+ to form HSO3−, thereby modulating the solution pH [18]. Since pH significantly influences the species of both Fe and S(IV) in the solution, it is essential to monitor the concentration profiles of Fe(II), Fe(III), and S(IV) throughout the reaction. Simulations performed using MEDUSA software (Version 16) in Figure 2a,b and Figure S1 illustrated the pH-dependent species of Fe(II) and S(IV), indicating that at the initial pH of 3.5, Fe(II) and S(IV) predominantly exist as Fe2+ and HSO3−, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution curves of Fe(II) (a) and S(IV) (b) under different solution pH; Concentration variation in Fe species (c) and S(IV) (d) during the Fe(II)/CaSO3 reaction. Conditions: [TBP] = 10 μM, [Fe(II)] = 50 µM, [CaSO3] = 400 µM, initial pH 3.5, temperature 25 °C.

Experimental measurements of pH, Fe(II), Fe(III), and S(IV) concentrations in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system are presented in Figure 2c,d. Upon initiation of the reaction, CaSO3 released SO32− gradually, leading to a rapid increase in both pH and S(IV) concentration within the first 30 s, whereas the concentration of Fe(II) remained largely unchanged. This suggests that the initially low concentration of S(IV) delayed the formation of the FeHSO3+ complex via reaction between Fe(II) and HSO3−, which aligns with the observed initiation phase in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system (Figure 1). After 1 min, the pH began to decline as the concentration of Fe(III) increased, indicating that the rate of H+ generation in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system exceeded the consumption rate via reaction with SO32− [19]. The S(IV) concentration subsequently decreased, stabilizing around 20 μM after 3 min, thereby prolonging the pollutant degradation process. In contrast, the S(IV) concentration in the Fe(II)/Na2SO3 system decreased rapidly and was completely consumed within 3 min, suggesting significant consumption of S(IV) via radical quenching pathways [26]. The sustained and slow release of S(IV) from CaSO3 effectively enhances the utilization efficiency of S(IV), highlighting the advantage of the CaSO3 compared to Na2SO3 in the previous literature [16,23].

3.3. Generation Pathways and Oxidative Contribution of Reactive Species

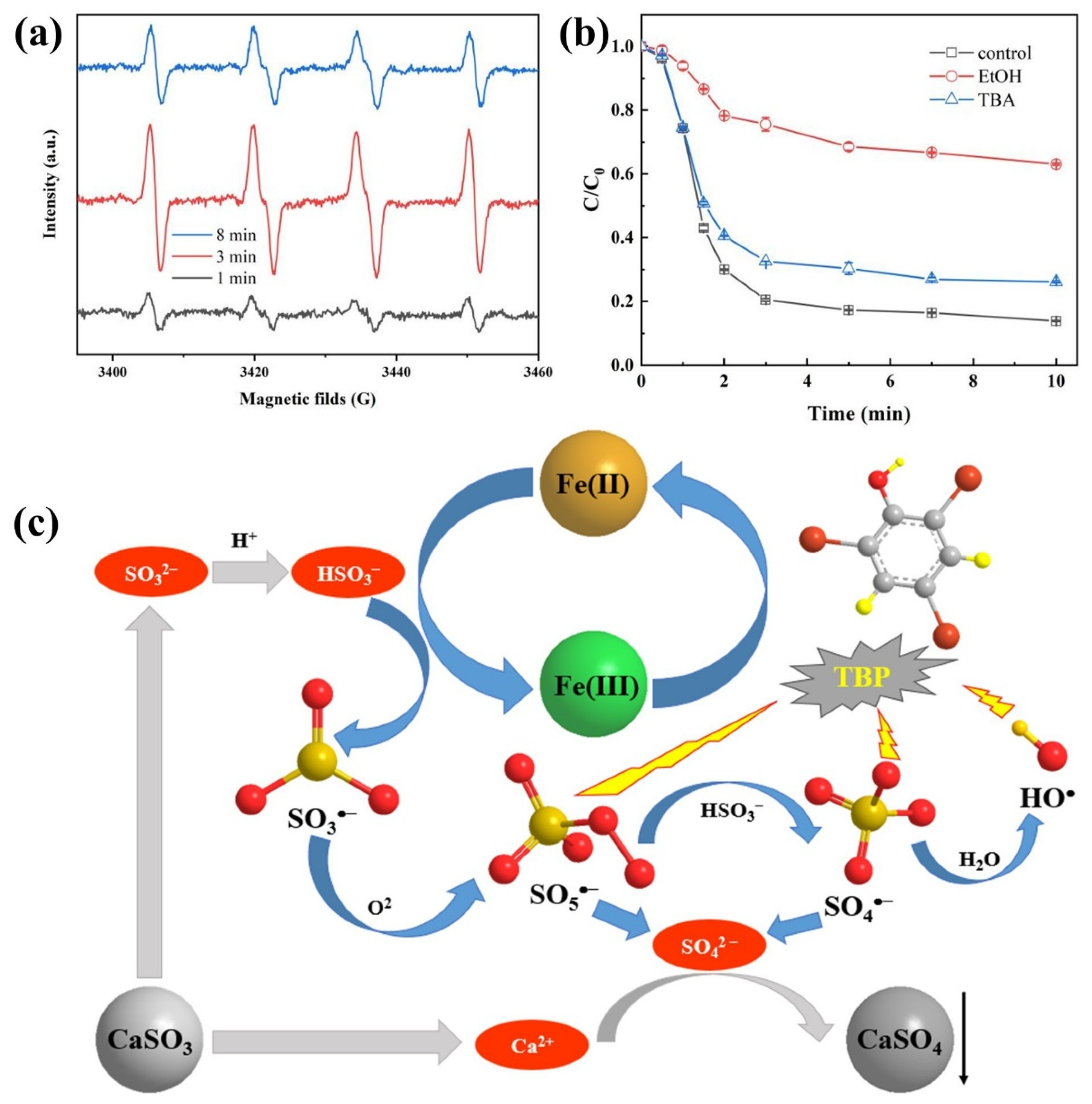

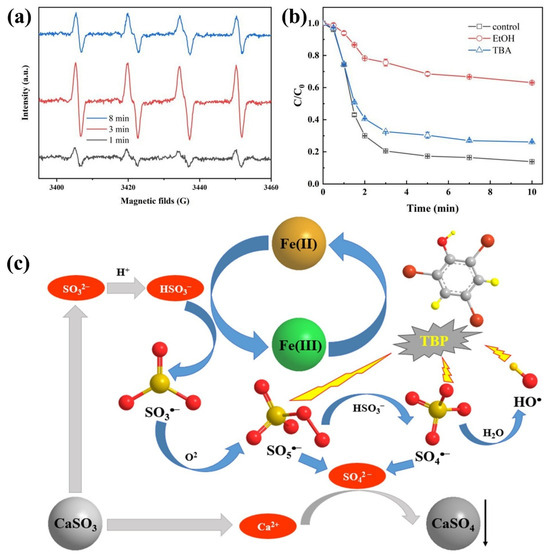

The Fe(II)/CaSO3 system exhibited significantly enhanced degradation efficiency toward TBP compared with the Fe(II)/Na2SO3 system, which is presumably attributed to the continuous generation of multiple reactive species, including SO5•−, SO4•−, HO•, and Fe(IV) [21,27]. In this study, 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolineN-oxide (DMPO) was employed as a spin-trapping agent to identify radical species generated in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system [28]. As shown in Figure 3a, the intensity of DMPO–SO3•− adducts in EPR spectroscopy initially increased and then decreased over the reaction process. The increase in signal intensity at 3 min indicates continuous generation of SO3•− in the solution. While after 8 min reaction, the decreasing intensity suggests that the formation rate of DMPO–SO3•− adducts was lower than their oxidative degradation rate. This observation implies the formation of higher reactivity radicals via Equations (5) and (6) in the system [24].

Figure 3.

EPR spectrum using DMPO as trap agent (a) and quenching experiments (b) in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system; The proposed reaction mechanism (c) of radical generation pathways. Conditions: [DMPO] = 50 mM in (a), [TBP] = 10 μM, [Fe(II)] = 50 µM, [CaSO3] = 400 µM, initial pH 3.5, temperature 25 °C.

To elucidate the potential formation of Fe(IV) in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system during the reaction, PMSO was employed as a probe compound for the identification of Fe(IV), which oxidizes PMSO to PMSO2 [27]. As shown in Figure S2, approximately 4.7 µM of PMSO was degraded, accounting for 23.5% of the initial dosage (100 µM). However, no PMSO2 was detected after the reaction for 10 min. These results indicate that the degradation of PMSO was attributable to the strong oxidative activity of radical species such as SO4•−, thereby excluding the possible contribution of Fe(IV) to TBP degradation under optimal experimental conditions [29].

To further quantitatively evaluate the contributions of various radical species to the TBP degradation, the effects of EtOH and TBA, acting as quenching agents, on the degradation efficiency of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system were investigated. TBA is an effective quencher for HO• (k = 6 × 108 L mol−1 s−1) but exhibits limited reactivity toward SO4•− [30]. In contrast, EtOH reacts rapidly with both SO4•− (k = 7.7 × 107 L mol−1 s−1) and HO• (k = 1.9 × 109 L mol−1 s−1), but only slowly with SO5•− (k < 1 × 103 L mol−1 s−1) [6]. By comparing the TBP removal after the addition of different quenchers, the relative contributions of each radical species to TBP degradation could be assessed. In the absence of any quencher, the degradation rate of TBP reached 86.1%. Upon addition of 10 mM TBA, the degradation rate decreased to 73.9%, representing a reduction of 12.2%. In contrast, when 10 mM EtOH was introduced, the degradation rate declined markedly to 36.9%. These results indicate that SO4•−, SO5•−, and HO• all participate in the oxidative degradation of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system, with SO4•− playing the dominant role.

Based on the above analysis, the reaction mechanism of the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system is summarized in Figure 3c. Fe(II) activates S(IV) that was sustainably released from CaSO3. This activation generates a series of reactive species including SO3•−, SO4•−, SO5•−, and HO•. Among these radicals, SO4•−, SO5•−, and HO• all contribute to the TBP degradation, with SO4•− being the primary reactive species responsible for TBP decomposition [31]. During this process, Fe(II) is oxidized to Fe(III), which further reacts with S(IV) to produce radicals and is subsequently reduced back to Fe(II), establishing a Fe(II)/Fe(III) redox cycle. Concurrently, Ca2+ released from the dissolution of CaSO3 react with SO42− to form CaSO4 precipitate, thereby reducing the potential impact on effluent water quality [32,33].

3.4. Effects of Operating Parameters

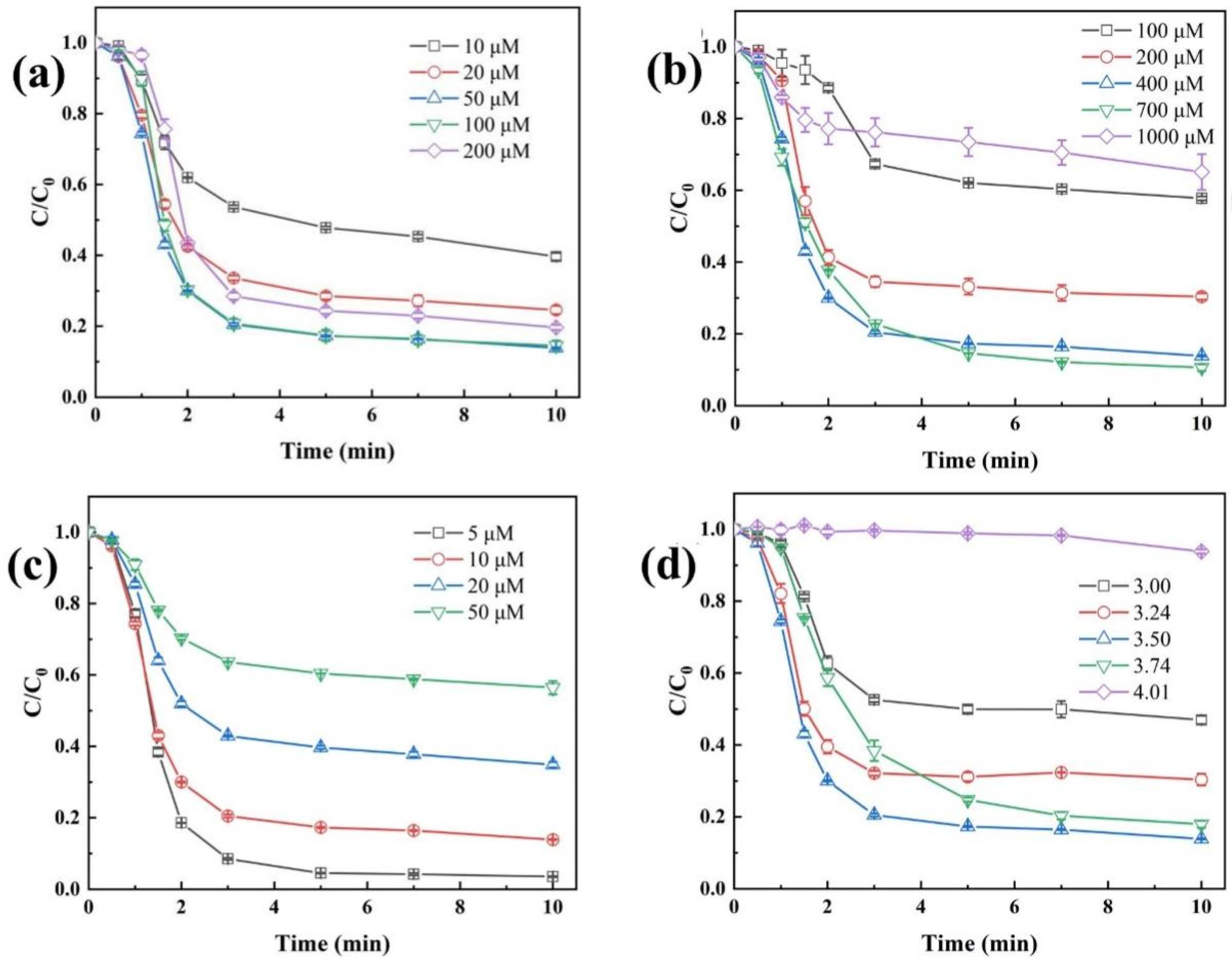

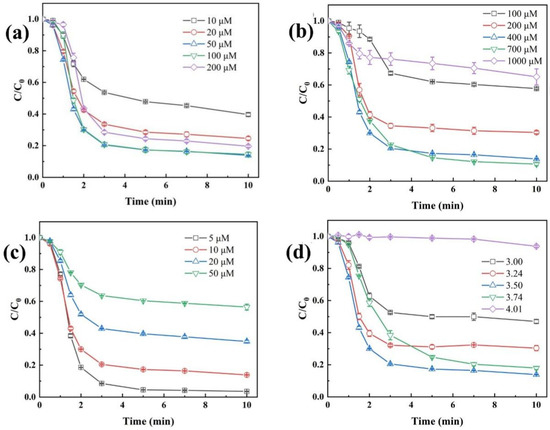

Under the condition of an initial CaSO3 dosage of 400 µM, the effect of Fe(II) dosage on the degradation efficiency of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system was investigated in Figure 4a. As the Fe(II) dosage increased from 10 µM to 100 µM, the removal efficiency of TBP gradually improved from 57.8% to 86.1%. This enhancement can be attributed to the increased generation of reactive species through Fe(II)-activated S(IV), thereby promoting TBP degradation [34]. However, when the Fe(II) concentration exceeded 100 µM, the excess Fe(II) scavenged the reactive radicals owing to its reducing nature, resulting in a decline in TBP degradation efficiency [35].

Figure 4.

Effects of operating parameters including Fe(II) (a) and CaSO3 (b) dosage, TBP concentration (c) and initial solution pH (d). Conditions: [Fe(II)] = 50 µM except (a), [CaSO3] = 400 µM except (b), [TBP] = 10 μM except (c), initial pH 3.5 except (d), temperature 25 °C.

The dosage of CaSO3 also exhibited a trend of initial increase followed by a decrease in TBP degradation. As shown in Figure 4b, when the CaSO3 dosage increased from 100 µM to 700 µM, the removal rate of TBP gradually rose from 42.2% to 89.4%. However, as the dosage was further elevated to 1000 µM, the TBP removal rate significantly decreased to 34.9%. As the source of S(IV), the dosage of CaSO3 directly determines the concentration of S(IV) during the reaction process [36]. According to Figure S2, with increasing initial CaSO3 dosage, the concentration of released S(IV) increased rapidly, promoting the generation of more radical species and thereby significantly enhancing TBP degradation. However, SO32− is also a strong reducing agent that can compete with TBP for reactive radicals such as SO4•−, SO5•−, and HO•. Therefore, excessive addition of CaSO3 led to an obvious inhibition.

Figure 4c illustrates the effect of initial TBP concentration on the degradation efficiency in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system. The results indicated that as the concentration increased from 5 µM to 50 µM, the removal efficiency decreased from 96.5% to 43.6%. Given that typical environmental concentrations of TBP generally fall within the ng/L to µg/L range under realistic pollution scenarios [15,37], the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system demonstrates highly effective removal performance. Further analysis of the absolute amount of degraded TBP in Figure S3 revealed that at initial TBP concentrations of 5, 10, 20, and 50 µM, the total degradation amounts were 4.82, 8.61, 13.03, and 21.78 µM, respectively. This trend can be attributed to the fact that higher TBP concentration competes for more available radicals.

Considering the significant influence of solution pH on the species of S(IV) and Fe, experiments were conducted to evaluate the removal efficiency of TBP by the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system under different pH conditions (Figure 4d). At pH 3.0, part of S(IV) exists as H2SO3, which exhibits low reactivity toward both Fe(II) and Fe(III), resulting in limited TBP removal [18]. As the initial pH increased from 3.0 to 3.5, the proportion of HSO3− rose gradually, promoting the formation of FeHSO3+ and FeSO3+ complexes. Consequently, the TBP removal efficiency increased from 53.0% to 86.1%. However, when the initial pH exceeded 4.0, the H+ concentration decreased markedly, and the subsequent release of S(IV) induced a rapid increase in solution pH (Figure S4). Under such conditions, Fe(III) undergoes complete hydrolysis and precipitation, preventing its participation in the radical chain propagation process. As a result, TBP degradation was nearly completely inhibited.

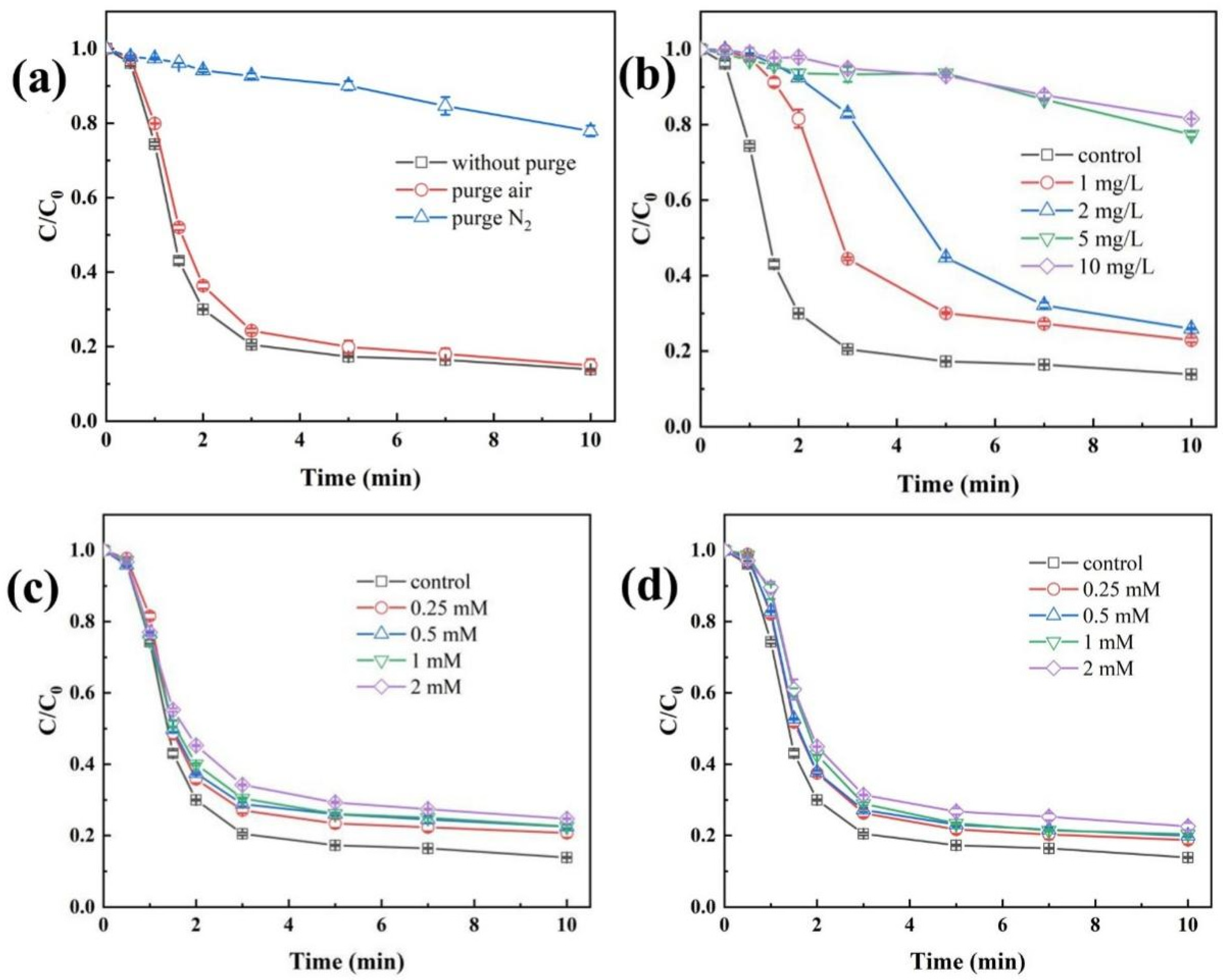

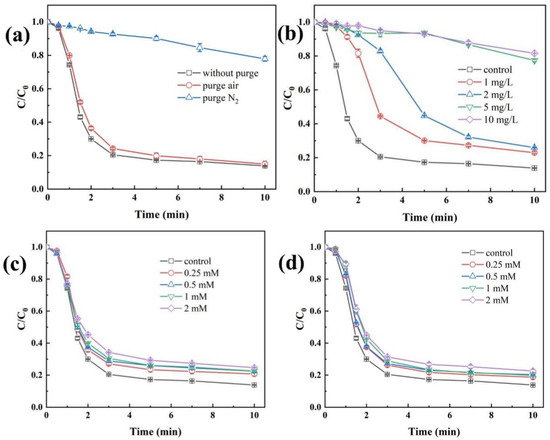

3.5. Impacts of Water Quality Conditions

Figure 5a illustrates the influence of dissolved oxygen (DO) concentration on the degradation efficiency of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system. Under both non-purged and air-purged conditions, the degradation efficiency of TBP after 10 min reaction showed no significant difference. In contrast, when N2 gas was introduced, the degradation efficiency of TBP decreased markedly to 22.1%. To elucidate the reason for this inhibition, variations in DO concentration during the reaction were monitored, as shown in Figure S5. Under non-purged and air-purged conditions, the DO concentration decreased rapidly within the first 3 min, reaching a minimum before gradually recovering. Since sufficient DO was available in both scenarios to sustain the reaction, the TBP removal rates were nearly identical. This result indicates that mechanical stirring alone can provide adequate oxygen replenishment for the system. However, when nitrogen was purged, DO was completely depleted, preventing the conversion of SO3•− to SO5•− via Equation (5). Consequently, the pathway for generating highly oxidative SO4•− was disrupted, leading to significant inhibition of TBP degradation [38].

Figure 5.

Impacts of water quality conditions, including aeration (a), NOM (b), Cl− (c) and HCO3− (d). Conditions: [TBP] = 10 μM, [Fe(II)] = 50 µM, [CaSO3] = 400 µM, initial pH 3.5, temperature 25 °C.

Natural organic matter (NOM) is widely present in natural water bodies and can significantly influence the degradation efficiency of pollutants in AOPs. Humic acid (HA), a major constituent of NOM, was thus selected as a representative model compound in this study [39]. Under fixed experimental conditions (50 µM Fe(II) and 400 µM CaSO3), the effect of HA concentration on the oxidative degradation of TBP in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system was investigated. The results are presented in Figure 5b. At HA concentrations of 1 mg/L and 2 mg/L, the TBP degradation was only slightly inhibited, with removal efficiencies decreasing to 77.1% and 74.1%, respectively. However, when the HA concentration increased to 5 mg/L, the TBP removal dropped markedly to 22.6%. A further increase to 10 mg/L HA resulted in a removal efficiency of only 18.5%. The inhibition of TBP degradation is attributed to the ability of NOM to rapidly react with HO• and SO4•−, thereby competing with TBP for reactive radicals [40]. In addition, the abundant carboxylic groups in HA may complex with Fe(III), hindering the formation of the key intermediate FeSO3+, which is essential for radical generation.

The influence of common anions in water, including Cl− and HCO3−, on the removal efficiency of TBP by the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system was further investigated. When the concentration of Cl− was increased from 0 mM to 2 mM, the removal efficiency of TBP decreased from 86.1% to 75.3% (Figure 5c), indicating a moderate inhibitory effect. This can be attributed to the fact that Cl− reacts with SO4•− and HO• in the system to form Cl• and Cl2•−, which can also rapidly react with TBP [18]. As shown in Figure 5d, when the concentration of HCO3− was raised from 0 mM to 2 mM, the removal efficiency of TBP only declined from 86.1% to 77.4%. Using the chemical equilibrium software MEDUSA, the species distribution of HCO3− under different pH conditions was simulated. Throughout the reaction in the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system, the pH remained between 3.5 and 3.8. Under these conditions, HCO3− predominantly exists as CO2 (aq) or H2CO3, while the concentration of the HCO3− species capable of rapidly scavenging radicals is relatively low [6]. Thus, its inhibitory effect on TBP degradation remains limited. In addition, the performance of Fe(III)/CaSO3 in treating actual water bodies spiked with TBP was examined in Figure S7, and a significant enhancement in the removal of DOC, TBP, and UV254 was observed compared to Fe(III) coagulation alone, demonstrating its excellent practical feasibility.

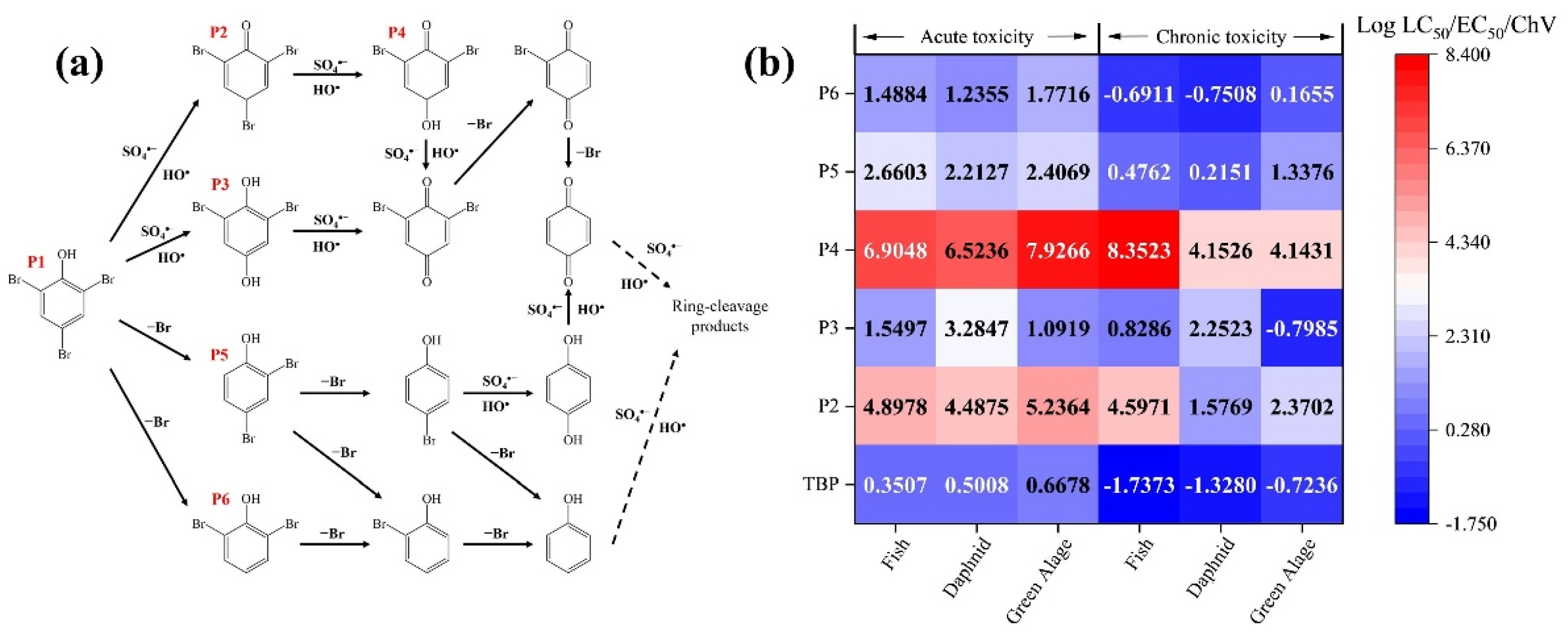

3.6. Intermediate Products Identification and Toxicity Prediction

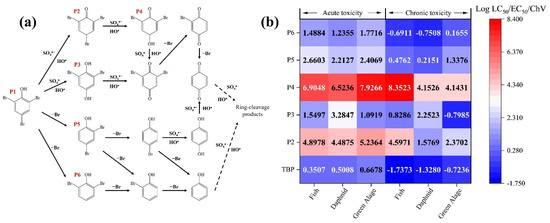

To elucidate the attack process of free radicals on the TBP molecule, DFT calculations were employed to determine the reactive sites of TBP. The optimized molecular structure of TBP and the computed natural bond orbital (NBO) charges for each atom are presented in Figure S6 and Table S1. Here, N represents the ground state of the molecule, N-1 denotes the state after losing one electron, and N+1 corresponds to the state after gaining one electron [41]. The results of the Fukui index indicated that the C2 and C6 positions are more susceptible to substitution reactions, whereas the C4–O12 and O12–H13 bonds are more prone to cleavage. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of a molecule largely dictate its chemical reactivity. A lower energy LUMO facilitates easier electron acceptance, while a higher energy HOMO indicates that electrons in this orbital experience less nuclear attraction, making them more likely to be donated [41]. Molecular orbital analysis (Figure S7) reveals that the HOMO of TBP is primarily localized on the C–Br bonds. Consequently, these sites are prone to donate electrons, leading to the oxidative debromination of TBP. To elucidate the degradation mechanism of TBP in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system, the oxidation products were qualitatively analyzed using HR-LC-MS by comparing m/z values. The results are summarized in Table S2 and Figure S10, and a detailed degradation pathway for TBP in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system is proposed in Figure 6a. The formation of P2 indicates that SO4•− exhibits high reactivity toward the -OH of TBP, oxidizing it to a carbonyl group. SO4•− can selectively attack C-Br bonds via electron transfer, generating P3, P5, and P6. These intermediate products can be further oxidized by SOso•− and HO• at the carbonyl group, followed by sequential debromination and cleavage of the benzene ring [42].

Figure 6.

Degradation pathway (a) and toxicity evaluation (b) of immediate products in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system.

To assess changes in toxicity during TBP degradation, an ECOSAR model was employed to evaluate the toxicity of intermediate products (Figure 6b). Toxicity endpoints included acute and chronic effects on three aquatic organisms (fish, daphnid, and green algae) [27]. In the resulting heatmap, darker blue colors and lower numerical values indicate higher toxicity, while red colors and higher values indicate lower toxicity. The results revealed that TBP exhibited the highest toxicity, with the lowest acute and chronic toxicity values for all three aquatic species. The high ecological risk indicated that developing efficient water treatment technologies for TBP is critically necessary. The oxidation of the carbonyl group led to the destruction of the benzene ring structure, significantly reducing the toxicity of P2 and P4. Moreover, debrominated products P3, P5, and P6 also showed decreased toxicity, suggesting that both the benzene ring and C-Br bonds are key structural features contributing to high toxicity. Given that all degradation products demonstrated reduced toxicity, the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system not only efficiently degrades TBP but also effectively detoxifies contaminated water. Luminescent bacteria toxicity test was further conducted in Figure S11. The initial reaction solution exhibited an inhibition rate of 27.3% toward photobacterium phosphoreum, indicating considerable acute toxicity attributable to the parent compound TBP. However, after 1 min treatment in the Fe(III)/CaSO3 system, the inhibition rate decreased significantly to 17.6%. It further declined to 4.6% in 5 min. These experimental data clearly demonstrate that the Fe(III)/CaSO3 process can effectively and rapidly reduce the acute toxicity of TBP.

4. Conclusions

The reducing property of S(IV) leads to nonproductive consumption of free radicals, which significantly inhibits the pollutant degradation efficiency of conventional S(IV)-based AOPs. This study demonstrates that the Fe(II)/CaSO3 system significantly enhances S(IV) utilization efficiency and achieves effective degradation and detoxification of TBP. The slow-release process of CaSO3 enables sustained generation of reactive species (mainly SO4•−), overcoming the limitations of soluble S(IV) sources. Mechanistic studies confirm the dominance of radical-induced pathways, including debromination and benzene ring cleavage, leading to markedly reduced ecological toxicity of intermediate products. The system maintains robust performance under acidic conditions and shows strong resilience to common water matrix components. By integrating cost-effective CaSO3 with efficient radical generation, this work provides a practical and sustainable strategy for treating halogenated aromatic compound-contaminated wastewater, highlighting the potential of slow-release oxidant sources in advancing green water treatment technologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17213100/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.W. and X.W.; Data curation, X.W.; Formal analysis, B.W.; Funding acquisition, D.L. and P.X.; Investigation, B.W.; Methodology, B.W. and X.W.; Project administration, D.L. and P.X.; Resources, D.L. and P.X.; Software, F.B. and Y.C.; Supervision, D.L.; Validation, S.L. and Z.W.; Visualization, S.L. and Z.W.; Writing—original draft, B.W. and X.W.; Writing—review and editing, P.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The supports by the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFC3202604-2), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52470007, 51878308), Scientific Research Special Project of South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Water Source Co., Ltd. (ZSY/YG-ZX (2023) 022), and the Young Top-notch Talent Cultivation Program of Hubei Province. We also thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for related measurements and the public computing service platform provided by Network and Computing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology to support the computing work.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Fan Bai was employed by the company “Henan Provincial Investment Company”. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from Scientific Research Special Project of South-to-North Water Diversion Middle Route Water Source Co., Ltd. (ZSY/YG-ZX (2023) 022). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Michałowicz, J.; Włuka, A.; Bukowska, B. A review on environmental occurrence, toxic effects and transformation of man-made bromophenols. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Song, X.; Fan, J.; Chen, C.; Li, Z. UV/Advanced Oxidation Process for Removing Humic Acid from Natural Water: Comparison of Different Methods and Effect of External Factors. Water 2024, 16, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.Y.; Show, P.-L.; Juan, J.C.; Ling, T.C.; Lau, B.F.; Lai, S.H.; Ng, E.P. Sustainable landfill leachate treatment: Optimize use of guar gum as natural coagulant and floc characterization. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, P.; Pirard, C.; Charlier, C. Determination of phenolic organohalogens in human serum from a Belgian population and assessment of parameters affecting the human contamination. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 599-600, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bai, F.; Cao, L.; Yue, S.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Ma, J.; Xie, P. Activation of sulfite by ferric ion for the degradation of 2,4,6-tribromophenol with the addition of sulfite in batches. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4766–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zou, Y.; Wang, S.; Yue, S.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. Transformation of tetrabromobisphenol a in the iron ions-catalyzed auto-oxidation of HSO3−/SO32− process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 235, 116197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonetti, C.; Butt, C.M.; Hoffman, K.; Miranda, M.L.; Stapleton, H.M. Concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and 2,4,6-tribromophenol in human placental tissues. Environ. Int. 2016, 88, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamssali, M.; Mantripragada, S.; Deng, D.; Zhang, L. Enhancing Swine Wastewater Treatment: A Sustainable and Systematic Approach through Optimized Chemical Oxygen Demand/Sulfate Mass Ratio in Attached-Growth Anaerobic Bioreactor. Environments 2024, 11, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Shen, X.; Zhang, D.; Chu, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, G. Electronic Control of Traditional Iron–Carbon Electrodes to Regulate the Oxygen Reduction Route to Scale Up Water Purification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 13740–13750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsawy, T.; Rashad, E.; El-Qelish, M.; Mohammed, R.H. A comprehensive review on the chemical regeneration of biochar adsorbent for sustainable wastewater treatment. npj Clean Water 2022, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.X.; Sun, J.Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.L.; Li, M.P.; Ma, X.H.; Xu, Z.L. Fe3O4/PVDF catalytic membrane treatment organic wastewater with simultaneously improved permeability, catalytic property and anti-fouling. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, M. Oxygen vacancies in piezoelectric ZnO twin-mesocrystal to improve peroxymonosulfate utilization efficiency via piezo-activation for antibiotic ornidazole removal. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Nie, Y.; Zhao, S.; Fan, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, A. Constructing surface micro-electric fields on hollow single-atom cobalt catalyst for ultrafast and anti-interference advanced oxidation. Appl. Catal. B 2022, 305, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łęcki, T.; Zarębska, K.; Sobczak, K. Skompska Photocatalytic degradation of 4-chlorophenol with the use of FTO/TiO2/SrTiO3 composite prepared by microwave-assisted hydrothermal method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 470, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.K.; Srivastava, A.; Garg, S.K.; Singh, V.P. Recent advances in degradation of chloronitrophenols. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 250, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, K. Surface treatment by the Fe(III)/sulfite system for flotation separation of hazardous chlorinated plastics from the mixed waste plastics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 377, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, P.; Liu, Y. Insights into the photo-reduction of nitrate in the presence of CaSO3: Performance and mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Z.; Cao, L.; Wang, Z.; Xie, P. Treatment of 2,4,6-tribromophenol-contaminated water using iron ion/calcium sulfite: The dual role of oxidation and coagulation. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 10, 2491–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lian, J.; Liu, B.; Zhu, X.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tan, F.; Wu, D.; Liang, H. Integrated ferrate and calcium sulfite to treat algae-laden water for controlling ultrafiltration membrane fouling: High-efficiency oxidation and simultaneous cell integrity maintaining. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 141880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Li, M.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Dong, S. Bimetallic (Cu, Zn) ZIF-derived S-scheme heterojunction for efficient remediation of aqueous pollutants in visible light/peroxymonosulfate system. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 330, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yan, X.; Xiao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Qi, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Mn-Co dual sites relay activation of peroxymonosulfate for accelerated decontamination. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 330, 122656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xie, P.; Ma, J. New insights into the degradation of micro-pollutants in the hydroxylamine enhanced Fe(II)/peracetic acid process: Contribution of reactive species and effects of pH. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Wang, Z.; Wan, G.; Cao, L.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xie, P. Combined oxidation and in situ coagulation in an iron-activated sulfite process for tribromophenol removal in an actual water matrix. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2024, 10, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cao, L.; Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Bai, F.; Xie, P. Enhanced degradation of tetrabromobisphenol A by Fe3+/sulfite process under simulated sunlight irradiation. Chemosphere 2021, 285, 131442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Cai, A.; He, H.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, F.; Fan, X.; Peng, W.; Li, Y. Atomically Fe doped hollow mesoporous carbon spheres for peroxymonosulfate mediated advanced oxidation processes with a dual activation pathway. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 20535–20544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Lu, X.; Xu, W.; Gong, Q.; Ding, J.; Dan, B.; Xie, P. Removal of acetaminophen in the Fe2+/persulfate system: Kinetic model and degradation pathways. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 358, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cao, L.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ma, J.; Xie, P. Tailorable morphology control of Prussian blue analogues toward efficient peracetic acid activation for sulfonamides removal. Appl. Catal. B 2024, 342, 123409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.X.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Gu, C.; Chen, X.; Zheng, H.; Xu, C.; Liu, W. Sensitivity of mass-independent Sn isotope fractionation to UV radiation and magnetic fields. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2504065122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Ji, Y.; Chen, D. Enhanced activation of peroxymonosulfate using ternary MOFs-derived MnCoFeO for sulfamethoxazole degradation: Role of oxygen vacancies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 441, 129912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Pan, T.; Li, D.; Lambropoulou, D.; Yang, X. Natural polyphenols enhanced the Cu(II)/peroxymonosulfate (PMS) oxidation: The contribution of Cu(III) and HO•. Water Res. 2020, 186, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Almatrafi, E.; Qin, H.; Huang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Tian, Q.; Xu, P.; et al. Confinement of ZIF-derived copper-cobalt-zinc oxides in carbon framework for degradation of organic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 440, 129811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Brighu, U. A comprehensive methodology for analysis of coagulation performance: Dosing approach, isotherm modelling, FTIR spectroscopy and floc characterization. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 52, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y. Coagulation of colloidal particles with ferrate(vi). Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2018, 4, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, D. Reductive Degradation of N-Nitrosodimethylamine via UV/S Water Resulfite Advanced Reduction Process: Efficiency, Influencing Factors and Mechanism. Water 2023, 15, 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Shang, F.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; Ping, Y.; Ding, J.; Wang, Z.; Xie, P. Enhanced Degradation of Deltamethrin in Water through Ferrous Ion Activated Sulfite: Efficiency and Mechanistic Insights. Water 2024, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yan, H.-N.; Jin, Y.-F.; Zhai, L.-F.; Sun, M. Co-Fe synergy in CoxFe1-xWO4: The new type peroxymonosulfate activator for sulfamethoxazole degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 461, 129811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bai, S.; Zhang, D.; Yang, S.-T.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Jing, L.; Liu, J. The influence of environmental factors on carbon isotopic fractionation during the degradation of tributyl phosphate (TBP) in advanced oxidation processes (AOPs). Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 202, 107686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Pan, C.; Peng, X.; Mao, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, L.; Huang, J. Deep mineralization of bisphenol A by catalytic peroxymonosulfate activation with nano CuO/Fe3O4 with strong Cu-Fe interaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 122539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yang, P.; Ji, Y.; Lu, J. The Role of Natural Organic Matter in the Degradation of Phenolic Pollutants by Sulfate Radical Oxidation: Radical Scavenging vs Reduction. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3325–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, Y.; Dabash, A.; Eghbareya, D. UV sensitization of nitrate and sulfite: A powerful tool for groundwater remediation. Environments 2018, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, L.; Bai, F.; Yue, S.; Xie, P.; Ma, J. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS(2)): A novel activator of peracetic acid for the degradation of sulfonamide antibiotics. Water Res 2021, 201, 117291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. HCO3–/CO32– enhanced degradation of diclofenac by Cu(II)-activated peracetic acid: Efficiency and mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 277, 119434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).