Abstract

The geochemical characteristics of reinjection fluids play a crucial role in controlling water–rock interactions and the long-term stability of geothermal reservoirs. This study aims to evaluate how different fluid chemistries affect mineral dissolution–precipitation behavior and ion migration during geothermal reinjection. Five types of reinjection water—including geothermal source water (i.e., formation water from the reservoir), primary and secondary treated waters, and their mixtures—were reacted with carbonate rocks from the Wumishan Formation of the Xiong’an New Area, North China Basin, under reservoir-like conditions (70 °C, 17 MPa). A combination of batch experiments, inverse modeling using PHREEQC, and one-dimensional reactive transport simulations was employed. Results show that fluid pH, ionic strength, and saturation state significantly influence reaction pathways. Alkaline-treated waters enhanced silicate dissolution, increasing Na+, K+, and Si concentrations, while source water and its mixtures promoted carbonate precipitation, increasing the risk of clogging. Simulations revealed that the early injection stage is the most reactive, with rapid ion front advancement and strong mineral transformations. Reaction-controlled ions such as Ca2+ and SO42− formed enrichment zones, while conservative ions like Na+ and Cl− propagated more uniformly. Moderate alkaline regulation was found to mitigate carbonate scaling and improve silicate reactivity, thereby reducing permeability loss. This integrated approach provides mechanistic understanding and practical guidance for reinjection fluid design in medium-to-deep geothermal systems.

1. Introduction

As the global development of geothermal energy accelerates, ensuring the sustainable utilization of geothermal resources has become a central challenge in both research and engineering practice. Geothermal reinjection, a critical strategy for maintaining reservoir pressure, prolonging the service life of well clusters, and mitigating land subsidence and environmental impacts, has been widely implemented across various geothermal systems in recent years. It involves reinjecting the extracted geothermal fluid—after heat extraction or treatment—back into the reservoir, where complex water–rock interactions take place, influencing mineral stability, porosity, and reservoir sustainability. In particular, reinjection has become a core component in enhancing heat recovery efficiency and ensuring stable production in typical geothermal reservoirs such as carbonate rocks, sandstones, and volcanic formations [1]. However, geothermal reinjection is far more than a simple physical process of fluid replenishment. It involves complex water–rock interactions, especially under high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, where injected fluids react with reservoir rocks through a series of dissolution, precipitation, and ion migration processes. These reactions not only modify the chemical composition of the geothermal fluids but also drive changes in the reservoir’s pore structure and permeability, ultimately influencing the long-term feasibility and economic viability of reinjection [2]. Consequently, in-depth investigations into the mechanisms of water–rock interaction and the evolution of mineral dissolution and precipitation during reinjection have become a key focus in current geothermal research.

Geothermal reinjection technology originated in the 1970s and was first applied in high-temperature dry steam fields such as The Geysers in California, USA, and Larderello in Italy, primarily to mitigate reservoir pressure decline [3]. With the growing development of medium- and low-temperature geothermal resources, reinjection practices have gradually expanded to two-phase and liquid-dominated geothermal reservoirs. This approach has been widely adopted in carbonate, sandstone, and fractured rock reservoirs in countries including China, Iceland, Japan, and New Zealand [3,4,5,6]. Although the development of geothermal reinjection technology in China started relatively late, it has advanced rapidly in recent years. Engineering-scale applications have now been successfully implemented in major basin-type geothermal reservoirs across regions such as Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, Shandong, and Henan [7,8,9,10]. The progress is particularly evident in large-scale district heating projects and the establishment of reinjection-based geothermal field management systems. This rapid advancement has been driven by increasing demand for sustainable clean energy, improvements in reinjection well design and monitoring technologies, and strong policy support for geothermal utilization and carbon neutrality goals. Despite these advancements, geothermal reinjection still faces several technical challenges in practice, among which reinjection blockage is one of the most critical [11]. Blockage can result from multiple mechanisms, including particle accumulation, microbial activity, gas exsolution, and mineral precipitation induced by water–rock interactions [12,13,14,15]. Among these, mineral precipitation is particularly problematic due to its concealed nature, the difficulty of real-time monitoring, and its often irreversible impact on reservoir permeability. In severe cases, it can lead to the complete failure of reinjection wells. Therefore, it is essential to utilize both experimental approaches and numerical simulations to investigate the interaction mechanisms between reinjection water and reservoir rocks. These efforts are crucial to providing theoretical support for optimizing reinjection system design and operational strategies.

To gain deeper insights into the water–rock interaction processes during geothermal reinjection, laboratory simulation experiments and hydrogeochemical modeling have become essential tools in geothermal science research. In terms of experimental system development, numerous universities and research institutions worldwide have established reaction setups capable of operating under a range of temperature and pressure conditions, typically between 70 and 200 °C and between 5 and 30 MPa [16,17,18,19]. These setups allow water–rock interaction experiments to be conducted using representative geothermal fluids and various rock types, including carbonate rocks (e.g., Ordovician and Jixian formation), Mesozoic sandstones, and volcanic tuffs. During the experiments, either powdered or intact rock core samples are reacted with geothermal fluids, and the evolution of major ion concentrations, pH, electrical conductivity, and saturation indices is continuously monitored to assess mineral dissolution and precipitation trends. In some studies, additional analytical techniques, such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area analysis, and in situ nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), are employed to characterize the mineralogical composition and pore/fracture structures of rock samples before and after reaction, thereby revealing micro-scale mechanisms of alteration [20,21,22,23]. Results from these investigations indicate that the early stages of geothermal reinjection are typically dominated by the dissolution of carbonate minerals such as calcite and dolomite. As the reaction progresses, secondary minerals, including chlorite, quartz, and various clays, may precipitate, leading to pore clogging and reduced permeability. Moreover, the chemical characteristics of the reinjection fluid play a critical role in governing the reaction pathways. For instance, elevated CO2 partial pressure, lower pH, and higher Na+ concentrations tend to enhance carbonate dissolution. Conversely, the addition of alkaline agents such as NaOH or Na2CO3 can modify fluid saturation states and promote the precipitation of specific minerals [24,25]. In China, systematic laboratory studies have evaluated the effects of various water treatment approaches—such as disinfection, filtration, and alkaline conditioning—on water–rock interactions, providing valuable theoretical support for geothermal water pretreatment strategies prior to reinjection [26].

Hydrological geochemical modeling tools have become indispensable, with PHREEQC (developed by the United States Geological Survey, USGS) being one of the most widely used simulation software programs today (available at: https://www.usgs.gov/software/phreeqc-version-3 (accessed on 2 September 2025)). PHREEQC supports various functions, including reaction pathway simulation, inverse simulation, kinetic modeling, and transport simulation. It can predict solution evolution pathways, mineral reaction directions, and rates based on the initial composition of fluids and rocks. Specifically, PHREEQC models rely on the following: (i) thermodynamic databases that calculate saturation indices of minerals and gases (via keywords such as EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES) which determine whether minerals will dissolve or precipitate and (ii) kinetic rate expressions (via KINETICS and RATES data blocks) that simulate time-dependent mineral dissolution/precipitation and hence provide estimates of reaction rates under given conditions.

In terms of experimental data fitting, researchers often use PHREEQC’s inverse modeling module to infer possible mineral dissolution and precipitation reactions based on changes in ion concentrations in solutions and determine reaction ratios. In kinetic simulations, by incorporating the KINETICS module and setting mineral reaction rate constants, surface area, and saturation index functions, the software can simulate mineral change trends over specific time periods and compare and fit these with batch experimental results. Some scholars have conducted high-temperature, high-pressure (120 °C) core displacement experiments in the Upper Triassic–Lower Jurassic Gassum Formation in northwestern Denmark to study the potential for storing heated formation water. Through geochemical and petrological analysis combined with PHREEQC geochemical modeling, changes in formation water and sandstone mineral composition were studied. The results indicated that reinjecting heated formation water into the Gassum Formation in Denmark may trigger the sodium feldsparization of microcline, dissolution of quartz, and precipitation of kaolinite and calcite. Calcite precipitation at high temperatures may cause injection issues, necessitating measures to prevent calcium carbonate scaling [27]. Other researchers conducted high-temperature and high-pressure batch experiments on the Szentes sandstone geothermal reservoir in Hungary. These experiments were combined with PHREEQC simulations using two thermodynamic databases and kinetic models to reproduce the geochemical processes. The results revealed the dissolution and precipitation evolution of carbonate and silicate minerals during short-term and long-term injection and cooling of geothermal water. Furthermore, the study quantitatively analyzed the variations in ion concentrations and assessed the potential for reinjection blockage [28]. Zhao Yuhui studied the water–rock reaction characteristics of the granite-type geothermal rock in Matouying, Hebei Province, in relation to groundwater, seawater, and pure water, and combined PHREEQC simulation to analyze the patterns of mineral evolution and water chemistry changes. The results showed that the mineral dissolution/precipitation reactions induced by different injected water bodies varied significantly, with lower precipitation after seawater reaction, primarily due to the adsorption capacity of the generated zeolite-type minerals. Appropriate regulation of Cl- content in seawater may enhance its potential application as a circulating water body in enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) [29]. On the other hand, the transport module of PHREEQC supports one-dimensional or multi-segment coupled reaction–transport simulation, which can be applied to predict solute and mineral evolution under near-wellbore injection conditions. Overseas, studies in Denmark, France, and other regions have combined columnar injection experiment results with the PHREEQC transport model [27] to conduct long-term predictions of mineral evolution trends in carbonate reservoirs under multi-year reinjection conditions, demonstrating the model’s application potential in assessing the lifespan of reinjection systems. Domestic researchers have similarly employed reaction pathway simulation software like PHREEQC to analyze reaction mechanisms, fit experimental results, and predict long-term processes [30,31].

The Wumishan Formation, a key component of the carbonate geothermal reservoir within the Jixian System, is widely distributed across the North China Craton and serves as one of the principal reservoirs for medium-to-deep geothermal development in the Xiong’an New Area. This formation is primarily composed of dolomite and microcrystalline limestone, characterized by a dense matrix with well-developed fractures and pores, endowing it with strong reservoir capacity and water conductivity. However, the coupled response characteristics of thermal–hydrological–chemical (THC) interactions under long-term extraction and reinjection remain poorly understood. In particular, the risks associated with pore structure evolution and secondary mineral precipitation induced by water–rock reactions—especially under the influence of injection fluids with varying chemical compositions—require systematic investigation. In the context of current geothermal development, the chemical properties of injected fluids are known to exert significant control over water–rock interaction processes, and this topic has been the subject of extensive research. Nevertheless, most existing studies focus on generalized carbonate systems, with limited attention paid to the specific applicability and effectiveness of alkaline regulation strategies for injection fluids in typical medium-to-deep carbonate reservoirs. To address this gap, the present study focuses on the Wumishan Formation carbonate reservoir and employs injection fluids with different chemical characteristics as experimental variables. A combination of quantitative laboratory experiments and hydrogeochemical modeling is used to investigate the regulated water–rock interaction pathways and their impacts on reservoir structure and reinjection performance at the microscopic level. This integrated approach aims to provide theoretical insights and engineering guidance for improving the efficiency and sustainability of extraction and reinjection in carbonate geothermal reservoirs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

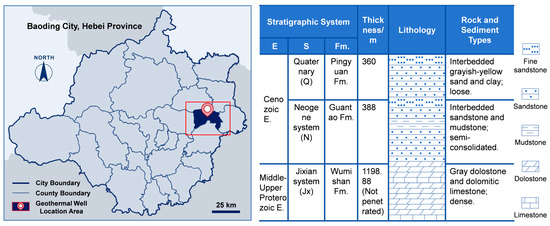

The rock chip samples used in this study were collected from a geothermal well in the Rongdong District of the Xiongan New Area (Figure 1). From a geological perspective, the well is located within the Rongcheng Uplift, with the target thermal reservoir being the carbonate rocks of the Wumishan Formation of the Ji County Series. To increase the reaction interface between the rock chips and geothermal fluids and accelerate the kinetics of water–rock interactions, the rock chip samples were pretreated prior to the experiment: they were ground and sieved through a 200-mesh screen to produce fine powdered rock chips, meeting the experimental requirements. The geothermal fluid used in the experiment was also sourced from the same geothermal well to ensure consistency in the water chemistry of the water–rock system throughout the experiment.

Figure 1.

Location of geothermal well (left) and core log (right).

To systematically study the effects of different water chemistry environments on water–rock reaction behavior, two treatment methods were applied to the original geothermal fluid (hereinafter referred to as YS). The first treatment method involved adding a disinfectant to the original water, followed by filtration through membranes with pore sizes of 5 microns and 0.45 microns to remove larger suspended particles and some microbial components, while the pH value and major ion composition of the water remained largely unchanged. The second treatment method aimed to more significantly alter the water chemistry environment: After adding disinfectant and filtering through a 5-micron membrane, 0.18 g/L of sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), 0.25 g/L of sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and 0.25 mL of citric acid (Huasheng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) were sequentially added to the water, followed by final filtration through a 0.45-micron membrane. The YS water retained the high mineralization characteristics of the original geothermal water, with a pH value close to neutral and high concentrations of Ca2+ and HCO3−. The first type of treated water retains the main chemical components of the raw water while removing microorganisms and suspended particles. In the second type of treated water, the Na+ concentration and alkalinity increase significantly, and the system saturation state and overall geochemical environment also undergo significant changes.

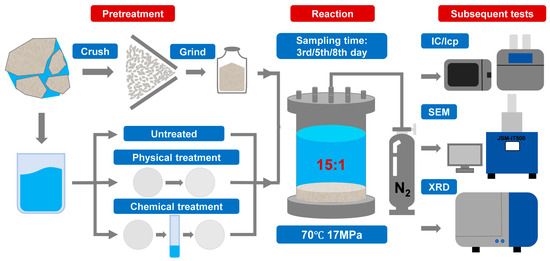

2.2. Static Batch Experiments

The experimental equipment used was a 316L-type high-temperature, high-pressure reactor (Origin: Nantong, China, Huaxing Petroleum Instrument Co., Ltd.) with a reaction chamber volume of 500 mL, capable of meeting experimental conditions of 200 °C temperature and 20 MPa pressure. The experimental system included a control system (pressure, temperature) and a pressure-increasing pump. Other auxiliary equipment included a high-temperature, high-pressure furnace, a tungsten filament scanning electron microscope (JSM-IT500), and an X-ray diffractometer (Japan Mechanics SmartLab SE) etc.

To simulate water–rock interactions under geothermal reservoir conditions, batch reaction experiments were conducted at 70 °C and 17 MPa for reaction durations of 3, 5, and 8 days. A total of 15 runs were performed, comprising five water types (three replicates each): geothermal water (YS), treated water I (MS), a 1:1 mixture (v/v) of treated water I and geothermal water, treated water II (CS), and a 1:1 mixture (v/v) of treated water II and geothermal water. For each run, the water-to-rock mass ratio was set to 15:1, corresponding to 300 mL of water and 20 g of crushed and ground carbonate reservoir rock (200 mesh) from the Wumishan Formation. The water samples and natural rock samples used in this experiment, along with their main ion compositions and mineral components, are presented in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

The main ion composition of different water samples.

Table 2.

The main mineral composition of the rock fragments.

The rock and water were sealed in stainless-steel autoclaves, heated to the target temperature, and pressurized with N2 gas to the target pressure. At the designated sampling times (3rd, 5th, and 8th day), heating was stopped and the autoclaves were cooled to room temperature before depressurization. The reacted fluid was filtered and stored in polyethylene bottles for analysis of pH, total dissolved solids (TDS), major cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, K+), anions (Cl−, HCO3−), and dissolved silica. The reacted solids were dried at 40 °C for 48 h, ground into powders, and characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the static water–rock experiment process.

2.3. PHREEQC Model Setup

To quantitatively analyze water–rock interaction processes under varying injection water conditions, this study utilizes the geochemical modeling software PHREEQC (Software version 3.6.2-15100) to simulate the geochemical evolution of the system. The modeling work is divided into two components: inverse geochemical modeling and forward reactive transport modeling, together forming an integrated simulation framework that bridges laboratory-scale static experiments and small-scale reservoir conditions. The research model incorporates both kinetic and transport modules. The simulation employs the IInl.dat thermodynamic database, which includes comprehensive thermodynamic and solubility data for carbonate, silicate, sulfate, and clay minerals. This database is particularly well-suited for simulating high-temperature (70 °C in this study) and high-salinity environments. The mineral species contained in the database closely correspond to those present in the experimental system, encompassing primary minerals such as sodium feldspar, quartz, and dolomite, as well as secondary minerals such as kaolinite, which were observed during the experiments.

The main PHREEQC keywords used in the model include the following: SOLUTION: Defines the chemical composition of the initial formation water and injected fluids. EQUILIBRIUM_PHASES: Applies mineral equilibrium constraints in inverse modeling and specifies the mineral phases allowed to react in forward simulations. KINETICS: Introduces kinetic controls for mineral dissolution and precipitation processes in forward simulations. TRANSPORT: Defines spatial discretization of the model domain, injection parameters (e.g., flow rate, diffusion length), diffusion coefficients, and porosity. RATES: Specifies custom reaction rate expressions for minerals. INVERSE_MODELING: Performs inverse modeling to estimate mineral reaction extents and saturation states based on multi-time-step experimental data.

Among these, inverse modeling is implemented using the INVERSE_MODELING keyword, which utilizes static experimental water chemistry data to identify the mineral types and corresponding mass changes involved in dissolution and precipitation. This approach helps infer reaction pathways that are consistent with observed geochemical changes. In contrast, forward simulations are conducted through the combined use of the KINETICS and TRANSPORT modules, where known reaction rate constants, initial geochemical conditions, and injection water characteristics are input to simulate the evolution of ion concentrations and mineral transformation behavior, thus capturing the coupled processes of transport and reaction during reinjection.

To construct a reactive transport model with predictive capability and quantitatively describe mineral reaction kinetics under experimental conditions, kinetic rate constants are calibrated based on results from static batch experiments. The Transition State Theory (TST) model is applied to fit the temporal variations in major ion concentrations, thereby deriving kinetic parameters under specific temperature–pressure conditions. Specifically, based on time-resolved ion concentration data, the release rates of individual elements are calculated and normalized to molar release rates per unit mineral surface area (mol/m2/s), according to the following equation:

Among these, ΔCi is the concentration change of the i-th ion (mol/L), V is the volume of the solution (L), Δt is the reaction time (s), A is the specific surface area of the solid sample (m2/g), and m is the mass of the rock fragment (g).

Subsequently, PHREEQC was used to calculate the saturation index (SI) of each mineral to assess the saturation state of the system.

Subsequently, the rate values obtained from the experiment were substituted into the TST model for fitting:

Here, ki represents the surface reaction rate constant to be fitted (moL/m2/s), and n is the empirical reaction order, typically set to 1. The fitting process is based on experimental values of r (reaction rate) and the corresponding saturation ratio (Q/K). The influence of temperature on reaction rates is accounted for either by extrapolating the fitted rate constants using the Arrhenius equation or by calculating temperature-dependent equilibrium constants using the Helgeson–Kirkham–Flowers (HKF) model [32].

3. Static Batch Experiment Results

3.1. Reactive Ion Migration Characteristics

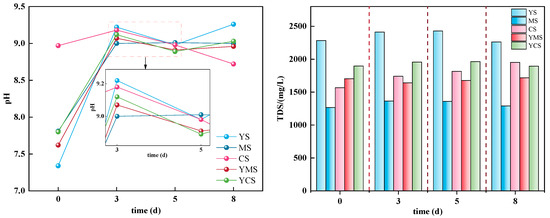

The results of the static dissolution experiment indicate that changes in pH and TDS during the reaction between different types of geothermal fluids and carbonate rocks reflect the chemical evolution characteristics of the fluid–rock system (Figure 3). Generally, untreated YS water releases alkaline components due to the dissolution of carbonate minerals (such as dolomite and calcite), causing the pH to rise rapidly in the initial stage and then decrease slightly, while treated MS and CS water bodies exhibit relatively minor pH changes in the initial stage. Among these, CS water bodies experience a significant decrease in pH during the later reaction stage due to alkaline regulation, which is associated with mineral precipitation and buffering effects. Mixed water bodies YMS and YCS tend to stabilize during the mid-reaction stage, indicating that alkaline regulation is influenced by dilution effects. Regarding TDS, all water samples exhibit overall minimal fluctuations, indicating that mineral precipitation changes have limited regulatory effects on total dissolved solid concentrations during short-term reactions. The original geothermal water (YS) has the highest TDS, consistent with its high mineralization background; treated water samples have slightly lower TDS, particularly CS water, where enhanced alkaline conditions cause partial mineral precipitation, resulting in a slight reduction in soluble total solids. Previous studies have noted that changes in TDS primarily depend on long-term dissolution/precipitation equilibrium processes, with short-term changes primarily manifesting as local variations. The experimental results of this study align with this understanding, further indicating that pH changes can serve as an indicator parameter for early water–rock reaction activity, while TDS is more suitable as a parameter for assessing overall solute equilibrium processes [33,34].

Figure 3.

Changes in pH (potential of hydrogen, left) and TDS (total dissolved solids, right) during the reaction process between different types of geothermal fluids and carbonate rocks. The left panel shows pH variations reflecting acid–base changes of the system, while the right panel presents TDS evolution, indicating the overall dissolution and precipitation trends of the system.

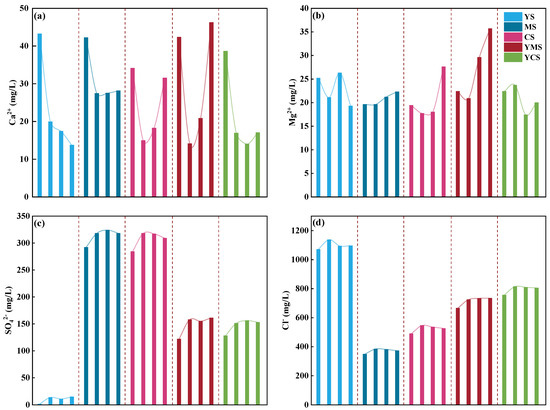

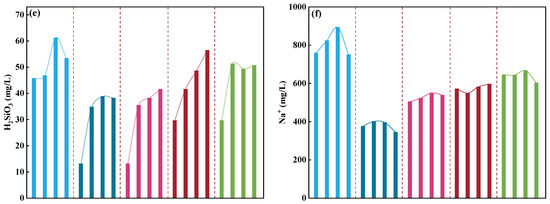

The experimental results indicate that different types of injection fluids, by altering system pH, ionic strength, and saturation state, significantly influence the migration of major ions and the dissolution–precipitation behavior of minerals (Figure 4 and Table 3). In the original geothermal water (YS), the coupled decline of Ca2+ and HCO3− reflects typical calcite precipitation under carbonate-supersaturated conditions without pH adjustment. K+, Na+, Mg2+, and H2SiO3 concentrations first increased and then decreased, indicating early dissolution of albite and other silicate minerals, followed by ion exchange, precipitation, or adsorption processes. The filtered and sterilized MS water exerted only a limited effect on reaction pathways: HCO3− and Na+ concentrations decreased slowly, while other ions showed only slight increases, suggesting minor dolomite dissolution and silicate release. In contrast, the CS water, with Na2CO3 and NaOH addition creating an alkaline environment, substantially enhanced Na+ activity and alkalinity, thereby suppressing calcite precipitation and promoting the dissolution of dolomite, albite, and other minerals. These observations are consistent with the findings of Schäffer et al. (2022) [21] and Xu et al. (2009) [35], who reported that alkaline adjustment of injection water facilitates carbonate and silicate dissolution. The mixed systems YMS and YCS, while retaining the original hydrochemical background, exhibited enhanced reactivity toward both carbonate and silicate minerals due to chemical adjustment, resulting in complex, coexisting multi-mineral reaction pathways. This highlights the key regulatory role of chemical control and compositional matching in governing mineral stability in reinjection systems.

Figure 4.

Grouped comparison of major ion concentrations in different injected fluids after 8 days of reaction. Each segment on the x-axis contains four points (0, 3, 5, and 8 days), representing YS, MS, CS, YMS, and YCS fluids, with the y-axis showing the concentration variation of major ions; ((a) Ca2+, (b) Mg2+, (c) SO42−, (d) Cl−, (e) H2SiO3, (f) Na+).

Table 3.

The changes in the molar amounts of various ions after the reaction of different types of geothermal fluids with carbonate rocks for 8 days.

Overall, the chemical characteristics of the fluids strongly affect ion migration and transformation, thereby determining the direction of mineral dissolution and precipitation. Specifically, the YS fluid favored pronounced calcium carbonate precipitation; the MS fluid showed relatively weak hydrochemical reactivity and mineral dissolution; the alkaline-regulated CS fluid promoted enhanced dissolution of dolomite and silicate minerals; and the mixed fluids YMS and YCS exhibited combined mineral reaction characteristics, simultaneously promoting carbonate dissolution and reflecting multiple interactive effects between fluids and minerals.

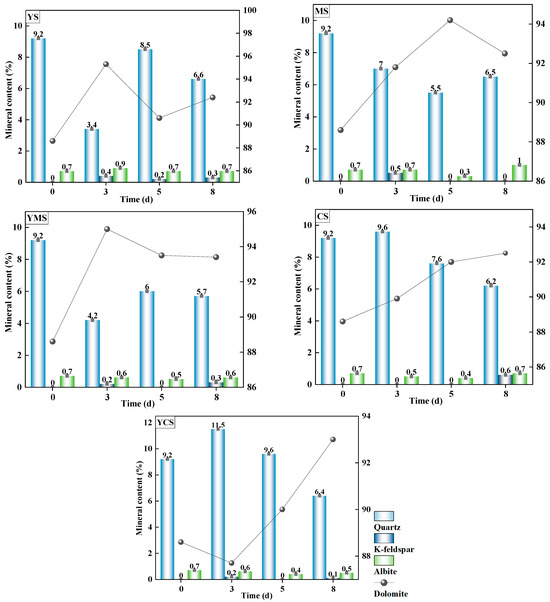

3.2. Characteristics of Mineral Dissolution Reaction

After the reaction, the overall mineral composition of the experimental rock samples remained dominated by dolomite, accompanied by quartz, minor clay minerals, and feldspars, although the relative proportions of minerals changed slightly (Figure 5). Compared with the original rock, dolomite content generally increased, albite content showed variable changes, K-feldspar content slightly increased, and quartz content decreased, indicating partial mineral dissolution and precipitation rearrangement. Ion variations in the fluids suggest the following mineral behavior: calcite precipitated most significantly in YS and YCS (marked decrease in Ca2+ and HCO3−), showed weak precipitation in MS and CS, and exhibited almost no precipitation in YMS. Dolomite showed slight precipitation in YS and YCS but dissolved in MS, CS, and YMS, with the strongest dissolution in YMS (Mg2+ increase was most pronounced). Silicate minerals dissolved in MS, CS, and YMS, as indicated by increased Na+, K+, and H2SiO3, with YMS showing the strongest effect, while dissolution in YS and YCS was minor. Sulfate minerals dissolved in all fluids (SO42− increase), with higher dissolution in CS and YCS. Overall, the type of injection fluid strongly influenced mineral dissolution and precipitation. YS and YCS were dominated by carbonate precipitation, MS and CS mainly promoted silicate dissolution, and YMS exhibited simultaneous carbonate and silicate dissolution.

Figure 5.

Changes in major mineral contents of rock samples over reaction time (0, 3, 5, and 8 days) under different injection fluids. YS, MS, CS, YMS, and YCS represent the respective fluid types.

4. Hydrogeochemical Simulation

4.1. Geochemical Inverse Modeling

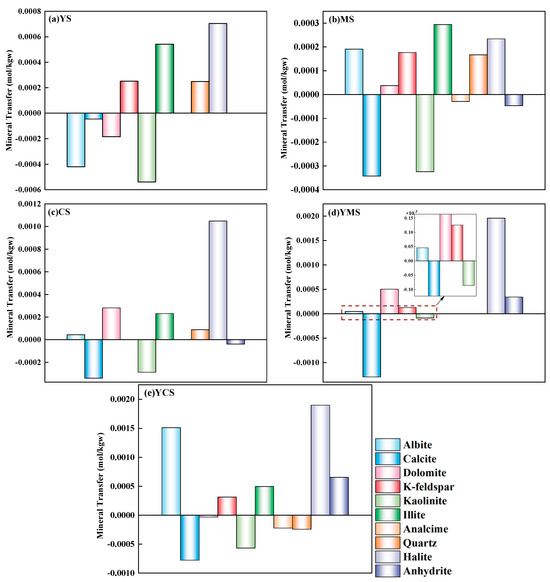

To investigate the primary water–rock interaction pathways and the evolution of key minerals, PHREEQC was employed to perform inverse modeling based on the results of static dissolution experiments conducted over an 8-day period between different types of injected fluids and carbonate reservoir detritus from the Wumishan Formation. The selection of minerals for inverse modeling was guided by both aqueous geochemical variations and mineralogical analyses before and after reaction. A total of nine representative minerals were included in the model, albite, calcite, dolomite, halite, K-feldspar, illite, kaolinite, and gypsum, encompassing both the original rock-forming phases and major secondary minerals observed during the reaction process.

The results of PHREEQC inverse modeling revealed significant mineral dissolution and precipitation processes after 8 days of reaction between different injected fluids and the Wumishan Formation carbonate reservoir detritus (Table 4 and Figure 6). The primary dissolving minerals included quartz, albite, K-feldspar, illite, halite, and gypsum, indicating that aluminosilicate and evaporite minerals are highly responsive to changes in geochemical equilibrium under injection conditions. In contrast, carbonate minerals (e.g., calcite and dolomite) and clay minerals (e.g., kaolinite) generally tended to precipitate, suggesting a potential risk of pore clogging during reinjection. Notably, the reaction pathways varied significantly among different water types.

Table 4.

Simulated mineral reaction amounts obtained from PHREEQC inverse modeling (positive values indicate dissolution, negative values indicate precipitation), in units of mmol/L.

Figure 6.

Mineral dissolution (positive) and precipitation (negative) in the carbonate reservoir under different injected fluids ((a): YS, (b): MS, (c): CS, (d): YMS, (e): YCS).

In the simulation of the YS sample, minor dissolution of quartz and K-feldspar occurred, accompanied by the precipitation of small amounts of calcite, dolomite, kaolinite, and albite. The precipitation of kaolinite reached −0.5391 mmol/L, implying a moderate risk of pore blockage due to the accumulation of clay minerals in micropores. The substantial dissolution of halite caused a sharp increase in fluid salinity, potentially triggering secondary mineral precipitation. While illite dissolution could slightly enhance porosity, the release of mobile clay particles might compromise reservoir integrity.

In the MS sample, dolomite, albite, and quartz dissolved, resulting in the formation of secondary minerals such as kaolinite and analcime. This type of geothermal fluid exhibited relatively stable geochemical behavior, with all dissolution reactions remaining below 0.3 mmol/L, indicating a low risk of clogging or structural damage. The dissolution of halite (0.2342 mmol/L) had a limited effect on porosity, and salinity remained within a controllable range, reflecting low potential for geochemical disruption.

The simulation of the CS sample showed dissolution of dolomite, albite, illite, quartz, and halite, along with the precipitation of calcite and kaolinite. This water type demonstrated the most favorable reinjection performance, characterized by moderate dissolution, low precipitation, and stable reaction pathways. The precipitation of kaolinite was significantly suppressed under alkaline conditions, while the impact of halite dissolution could be mitigated by flow control. No analcime precipitation was observed, effectively avoiding micropore clogging by zeolite minerals. The slight dissolution of illite (+0.2309 mmol/L) contributed to improved pore connectivity, and the system exhibited high chemical stability with minimal risks of clogging or structural disturbance.

In the YMS mixed water, the precipitation of calcite reached −1.29 mmol/L, potentially clogging millimeter-scale pores. Concurrently, the intense dissolution of halite and dolomite exacerbated salinity imbalance and induced secondary mineral precipitation, posing a high risk of injection impairment. For the YCS mixed water, simultaneous precipitation of calcite and kaolinite posed an extremely high risk of clogging, while the intense dissolution of albite and halite could compromise the structural integrity of the reservoir framework. These results indicate poor chemical stability and unsuitability of the YCS sample for reinjection purposes.

4.2. Forward Reactive Transport Modeling

4.2.1. One-Dimensional Model Construction and Boundary Conditions

The one-dimensional reactive transport model is implemented using the KINETICS and TRANSPORT modules in PHREEQC. The model consists of 100 spatial cells, each with a length of 1 m, resulting in a total simulation domain of 100 m along the principal direction of fluid flow. The simulation time step is set to 8640 s (equivalent to 0.1 days), with a total of 1500 steps, corresponding to an overall simulation duration of approximately 150 days. Among the various injection water scenarios, the alkaline-regulated water sample from Treatment II (CS) is selected for long-term reactive transport simulation. This scenario aims to evaluate the reaction–diffusion behavior and clogging risk under realistic reservoir conditions. The minerals included in the model and their associated parameters are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reaction equations, specific surface area (SSA), initial mineral content (mo), and kinetic parameters of each mineral in the reaction–transport model.

In the model, the dispersion coefficient is typically used to represent mechanical dispersion caused by formation heterogeneity and the curvature of microscopic flow paths. Previous studies have shown that at the laboratory scale, longitudinal dispersivity generally ranges from a few centimeters to several tens of centimeters, while at the field scale, it can reach several meters to over ten meters, depending on the degree of formation heterogeneity [38]. Given the relatively small scale of this study’s model, a uniform dispersivity setting is adopted, with the longitudinal dispersivity of each cell set to 0.1 m. The pore diffusion coefficient is set to 1 × 10−9 m2/s to account for molecular diffusion of ions in stagnant pore spaces. The porosity is defined as 0.075 based on typical values observed in carbonate reservoirs in the study area [39,40] and to further reflect coupling effects during heat and mass transfer processes. Model outputs are generated every 10 time steps (i.e., once per day) to track the dynamic evolution of water chemistry and mineral transformation throughout the reactive transport process. The initial condition assumes that the entire 1D profile is in the background state of the geothermal reservoir, with uniform distributions of aqueous chemistry and mineral composition. As for boundary conditions, the leftmost cell (cell 0) is continuously supplied with reinjection water of known composition (defined via the SOLUTION keyword), while the remaining cells evolve through coupled reaction and transport processes. The right boundary is set as a free outflow (zero-gradient boundary condition), ensuring no reflection or feedback occurs.

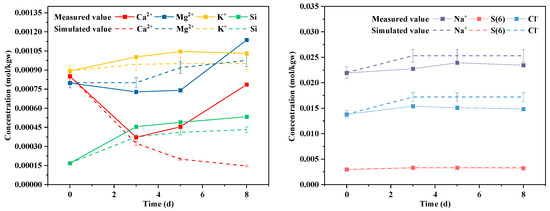

4.2.2. Verification of Simulation Models

To validate the effectiveness of the one-dimensional reactive transport model in representing water–rock interactions during the reinjection process, the simulation results were compared with static batch experimental data conducted at 70 °C and 17 MPa. The comparison focused on the concentration evolution of major ions (Ca2+, Na+, Mg2+, SO42−, K+, Cl−, and Si) in the solution over an 8-day period. The correspondence between the experimental measurements and the simulated values is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison between experimental and simulated concentrations of major ions (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, Cl−, SO42−, K+, Si, and alkalinity) over an 8-day reaction period. Solid lines represent experimental data, while dashed lines indicate simulated results.

The figure demonstrates that the model effectively captures the temporal trends in the concentrations of most ions during the reaction process. For example, the concentration of Ca2+ decreases rapidly within the first three days, reflecting the dissolution–precipitation dynamics of carbonate minerals, and this trend is well reproduced by the model. The concentrations of Na+ and Cl− remain relatively stable, with good agreement between simulated and experimental values. The gradual increase in Si concentration indicates the slow dissolution of silicate minerals (e.g., quartz and albite), which is accurately reflected in the simulation results.

In terms of numerical error, most ions exhibit relative deviations below 20% except for Ca2+, which shows a noticeable discrepancy in the later stages of the experiment. Specifically, the normalized root mean square error (NRMSE) for Ca2+ reaches 56.1%, with the maximum relative error of 81.4% occurring on day 8. This deviation may stem from the model’s inability to fully capture late-stage Ca2+ release mechanisms, such as the delayed dissolution of carbonate or aluminosilicate minerals, or the desorption of calcite due to changing conditions. Additionally, minor disturbances during sampling or leakage in the batch experiment could have caused local fluctuations or transient increases in Ca2+ concentrations that are difficult to replicate in the simulation.

Overall, the model successfully reproduces the migration and transformation patterns of key reactive species observed in the experiment. This indicates that the kinetic mechanisms and parameter settings used are broadly applicable and reliable, supporting their further use in predicting the long-term dissolution–precipitation behavior of reservoir minerals during reinjection.

4.2.3. Simulation Results

- (1)

- Carbonate reaction group.

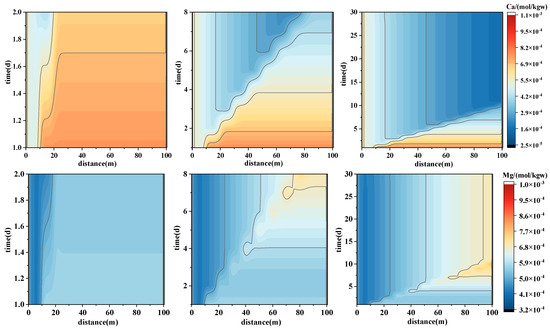

The forward simulation results indicate that the most pronounced reaction–transport features occur during the early stages of injection. Therefore, the analysis of concentration variations is primarily focused on the first 30 days. Ca2+ (Figure 8—top) exhibits a clear pattern of decreasing concentration with increasing distance. In the initial reaction phase, the breakthrough front rapidly advances to 15 m, forming a distinct concentration gradient within the 10–20 m range, with higher concentrations accumulating toward the downstream section of the model domain. By day 8, the breakthrough front reaches approximately 30 m and a pronounced low-concentration zone emerges, indicating Ca2+ consumption through precipitation reactions. By day 30, Ca2+ concentrations show an overall decline. These patterns suggest that Ca2+ undergoes rapid migration during the early injection phase, corresponding to the dissolution of calcite and other carbonate minerals. A reaction zone is formed in the mid-forefield (10–40 m), where Ca2+ concentrations progressively decline, reflecting a clear depletion pattern due to reaction consumption. The mineral saturation index (SI) for calcite further validates this trend: SI_Calcite initially ranges from −0.53 to −0.54 (undersaturated), with a corresponding dissolution rate (dk_Calcite) of approximately −1.65 × 10−6 mol. By day 30, SI_Calcite increases to 0.7162 at 100 m (supersaturated), with dk_Calcite approaching zero, indicating a transition from dissolution to precipitation control.

Figure 8.

Spatial–temporal evolution of major ion concentrations during forward PHREEQC simulations of geothermal reinjection. The panels illustrate concentration variations of Ca2+ (upper), Mg2+ (middle), and SO42− (lower) along the 100 m model domain over the first 30 days of injection. These trends reveal distinct migration and reaction behaviors of divalent cations and anions under different chemical equilibria within the reactive transport system.

In contrast, Mg2+ (Figure 8—middle) shows a delayed breakthrough front compared to Ca2+ (reaching only 10 m by day 2), with overall lower concentration levels concentrated in the 30–50 m range. This reflects a “slow release–redistribution” behavior, consistent with the gradual dissolution and re-equilibration of dolomite. The saturation index for dolomite (SI_Dolomite) remains around 0.77 (supersaturated), with a corresponding precipitation rate (dk_Dolomite) of 3.08 × 10−6 mol. By day 30, SI_Dolomite slightly decreases to 0.7668, suggesting that early Mg2+ release is dominated by dissolution, while precipitation becomes increasingly significant over time.

The distribution of sulfur (SO42−) (Figure 8—below) exhibits a similar spatial pattern to Ca2+ but with more dramatic concentration changes. A distinct high-concentration band forms along the injection front (10–30 m), primarily attributed to the dissolution of sulfate minerals such as gypsum. This region displays wave-like deformation, reflecting strong flow–reaction coupling. After 30 days, an enrichment zone of SO42− persists in the mid-section, indicating accumulation due to concurrent advection and mineral reactions.

- (2)

- Weakly reactive ion group.

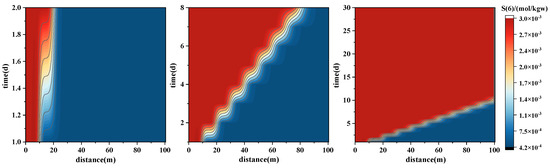

The migration of Na+, K+, and Cl− is primarily governed by physical transport, with minimal reaction involvement. In Figure 9, the concentration distributions of these ions exhibit a consistently advancing front, showing spatially uniform progression. The Na+ and Cl− fronts advance rapidly, reaching approximately 25 m at day 2, 60 m at day 8, and nearly spanning the entire model domain (90–100 m) by day 30. Their concentration profiles remain largely stable over time, indicating typical conservative ion behavior, dominated by advection and dispersion, with late-stage transport influenced by dilution or density gradients, while their weak reactivity maintains smooth spreading.

Figure 9.

Spatial–temporal evolution of major ion concentrations during forward PHREEQC simulations of geothermal reinjection. The panels illustrate concentration variations of Na+ (upper), K+ (middle), and Cl− (lower) along the 100 m model domain over the first 30 days of injection. These results reflect the migration and exchange processes of monovalent ions.

K+ displays slightly different behavior compared to Na+ and Cl−. A notable concentration peak forms within the 10–40 m range initially, with a slight decline in later stages, suggesting that K+ was rapidly released from minerals such as K-feldspar and illite during the early injection period. A “reaction zone” forms in the mid-section (10–25 m), followed by minor adsorption or re-precipitation in the mid-to-late section, after which conservative transport dominates and precipitation effects become minimal, leading to diffusion equilibrium. Mineral saturation indices indicate that SI_Illite increased from −0.1705 to 0.16 with dk_Illite of 1.03 × 10−7 mol (precipitation), while SI_K-Feldspar was −0.018 with dk of −2.3 × 10−7 mol (dissolution), reflecting early-stage dissolution and minor late-stage precipitation.

- (3)

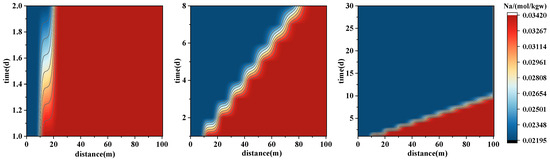

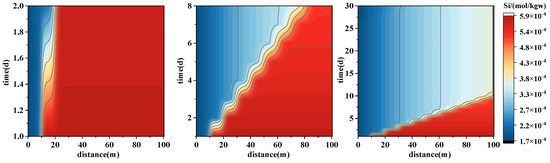

- Silicate dissolution index.

The simulation results of Si concentration distribution are presented in Figure 10, revealing a characteristic slow-release pattern associated with silicate mineral dissolution. In the initial reaction stage, the leading front extends to 10 m, forming a weak concentration gradient between 10 and 15 m, with higher concentrations accumulating toward the downstream end. After 8 days, the front advances to 20 m, and a low-concentration zone begins to appear, indicating consumption of Si at the leading edge. By day 30, Si concentration in the 97.5–99.5 m section decreases to approximately 0.000347 mol/L, showing a gradual decline. This suggests that Si release is dominated by dissolution of silicate minerals (e.g., quartz, albite, clay minerals) in the early injection stage, forming a “dissolution zone” in the mid-section (10–20 m), with concentrations stabilizing at later times. Mineral saturation indices show that SI_Quartz decreases from 0.1077 to −0.115, with dk_Quartz changing from 9.09 × 10−6 mol (precipitation) to −7.2 × 10−7 mol (dissolution), while SI_Albite is −1.04 with dk_Albite of −1.19 × 10−8 mol (dissolution), confirming initial minor precipitation followed by dissolution dominating the process.

Figure 10.

Spatial–temporal evolution of Si concentration during forward PHREEQC simulations of geothermal reinjection. The panel shows Si, illustrating concentration changes along the 100 m model domain over the first 30 days of injection.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Influence of Alkaline Regulation on the Water–Rock Reaction Pathway

The static experimental results revealed significant differences in water–rock interactions between various types of reinjection water and the carbonate rocks of the Wumishan Formation. In the YS system (untreated geothermal water), both calcite and dolomite exhibited low solubility. However, the progressive decreases in Ca2+ and HCO3− concentrations over time indicated a state of supersaturation with respect to calcium carbonate, ultimately leading to calcite precipitation. This observation was further confirmed by the PHREEQC inverse modeling, which showed negative values for calcite mass transfer, consistent with precipitation. In contrast, the MS system (primary-treated water), which underwent filtration and sterilization, exhibited reduced mineral precipitation, particularly a decline in calcite precipitation and a slight enhancement in dolomite dissolution. These findings were also supported by PHREEQC simulation results, suggesting that while filtration and sterilization removed suspended solids and microbial activity, they did not significantly alter the ionic strength of the fluid and thus had limited impact on the overall mineral dissolution–precipitation behavior.

When alkaline agents such as NaOH and Na2CO3 were added to the injection water (CS system), both experimental and simulation results indicated that the enhanced alkalinity reduced calcite precipitation and increased dolomite solubility. PHREEQC modeling showed that the addition of NaOH and Na2CO3 significantly altered the saturation state of the system. Alkaline adjustment suppressed carbonate mineral precipitation while promoting the dissolution of silicate minerals, such as albite. The increased involvement of silicate minerals contributed to improved pore structure and helped mitigate the negative impact of carbonate precipitation on reservoir permeability. These findings suggest that alkaline regulation of the injection water not only altered mineral dissolution kinetics but also facilitated the dissolution of different minerals by modifying the ionic composition of the solution.

The experimental and PHREEQC simulation results for the YMS and YCS water types further highlight the complexity of mineral reaction pathways in mixed water systems. Notably, the YMS water exhibited enhanced dissolution of dolomite as well as increased solubility of silicate minerals. Experimental data showed that the elevated Na+ concentrations promoted the dissolution of silicate minerals such as albite, while the dissolution of carbonate minerals also intensified. The PHREEQC inverse modeling results aligned well with the experimental observations, indicating that changes in ionic concentration directly influence the dissolution–precipitation equilibrium of minerals.

In contrast, the YCS water system showed a more pronounced tendency for calcite precipitation. Both experimental data and PHREEQC simulations confirmed significant calcite precipitation. Due to the mildly alkaline pH maintained in the mixed water system, calcite readily reached supersaturation and precipitated under such conditions. Additionally, the dissolution of sulfate minerals was evident in the YCS system, with both experimental and modeling results supporting this observation.

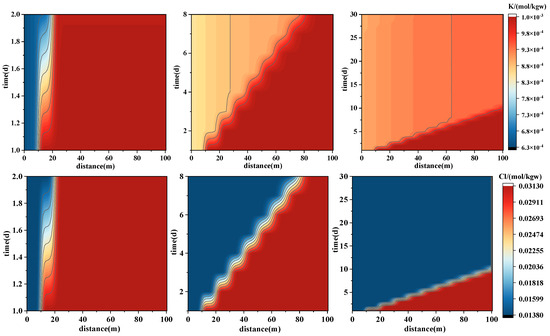

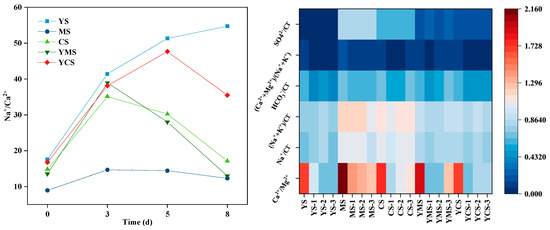

To more clearly reveal the regulatory effect of alkaline control on the reaction pathway, typical ion ratio indicators were further introduced for analysis (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Temporal evolution of major ion ratios during batch experiments at 70 °C and 17 MPa. The panels show changes in Na+/Ca2+, (Na+ + K+)/Cl−, SO42−/Cl−, HCO3−/Cl−, and Ca2+/Mg2+ over the 8-day reaction period, reflecting the coupled effects of ion migration, mineral dissolution, and precipitation under different injection water conditions.

The evolution of major ions during the reaction provides crucial insights into the water–rock interaction processes. The continuous increase in Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations indicates carbonate dissolution as a dominant process, primarily driven by the undersaturation of calcite and dolomite in the early reaction stage. Meanwhile, Na+ and K+ concentrations gradually increase due to the dissolution of silicate minerals such as albite and K-feldspar, whereas the decrease in SO42− and Cl− reflects gypsum dissolution followed by possible secondary precipitation and ion exchange processes.

The variation in ion ratios further reveals the competitive reactions among different minerals. A decreasing Na+/Ca2+ ratio and increasing Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio indicate enhanced carbonate dissolution and cation exchange between Na+ and Ca2+. The (Ca2+ + Mg2+)/(Na+ + K+) ratio shows that alkaline solutions promote cation exchange and silicate dissolution while inhibiting secondary carbonate precipitation. In particular, the increase in Na+ and K+ relative to Cl− (Na+ + K+/Cl−) suggests that ion sources are not solely from simple halite dissolution but are strongly affected by silicate hydrolysis. Overall, the ionic responses highlight the coupled behavior of dissolution, ion exchange, and re-precipitation during fluid–rock reactions, governed by both fluid composition and mineral buffering capacity.

As shown in Table 6, the variations in ionic concentrations exhibit a consistent quantitative correspondence with the simulated mineral dissolution–precipitation processes, although the absolute values do not perfectly match. Such discrepancies mainly arise from the overlap of multiple mineral reactions, charge-balance constraints in inverse modeling, and the influence of ion exchange or surface adsorption.

Table 6.

Correlations between major ion variations and corresponding mineral dissolution/precipitation processes.

The distinct responses among different water systems reflect the coupling between carbonate re-precipitation and silicate dissolution driven by the chemical composition of the injected fluids. In the YS and YCS systems, both Σ(Ca2+ + Mg2+) and HCO3− show significant decreases, accompanied by negative values of (calcite + dolomite). This indicates that carbonate minerals predominantly re-precipitate, leading to Ca2+ and Mg2+ depletion in the aqueous phase [41]. Conversely, the CS and YMS systems display positive Na+ and H2SiO3 variations, coupled with increases in aluminosilicate dissolution (mainly albite and K-feldspar). These features suggest that higher Na+ content and moderate alkalinity facilitate silicate dissolution while suppressing carbonate re-precipitation. The MS system represents a transitional state, showing moderate carbonate precipitation alongside continuous feldspar dissolution. Collectively, these quantitative relationships confirm that the observed ion evolution can be attributed to coupled carbonate precipitation–silicate dissolution reactions, governed by the fluid’s alkalinity and ionic composition.

Mechanistically, the enhancement of silicate dissolution under moderate alkalinity increases the buffering capacity of the system, maintaining near-neutral pH in the reaction zone and preventing excessive carbonate saturation. This self-regulating feedback helps mitigate scaling risk near the injection well and promotes a spatial redistribution of reactive fronts deeper into the reservoir [42].

5.2. Ion Migration Rules and Risk Assessment

The forward PHREEQC simulation results reveal distinct differences in the migration behaviors of various ions within the reservoir, which can be broadly categorized into three types:

- Reaction-controlled ions (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+, SO42−): These ions form pronounced concentration peaks near the injection front and gradually migrate deeper as reactions progress. Their behavior is characterized by a “front propagation–reaction release–localized enrichment” pattern, primarily governed by the dissolution and precipitation of carbonate and sulfate minerals.

- Physically transported ions (e.g., Na+, Cl−): These exhibit well-defined and consistent front advancement with relatively stable concentrations, acting as conservative tracers that reflect fluid flow paths and migration velocities. While Na+ may be slightly affected by the dissolution of feldspar minerals, its overall reactivity remains low.

- Slow-releasing ions (e.g., Si): These ions show a delayed front propagation and gradual concentration increase, indicative of the limited reaction rates of silicate minerals (e.g., quartz, feldspar, illite) under high-temperature water–rock interaction conditions. This behavior suggests that Si may serve as a key factor controlling long-term reservoir evolution.

Alkalinity-regulated water injection presents a pronounced dual effect in geothermal reinjection systems. On one hand, moderately elevated pH can improve reservoir rock wettability and enhance aluminosilicate dissolution, thereby delaying early-stage clogging and unlocking additional reactive capacity. On the other hand, excessively high pH or elevated concentrations of alkaline cations may trigger the precipitation of carbonate and sulfate minerals, potentially causing scale formation and reducing reservoir permeability.

Therefore, it is essential to develop targeted water chemistry regulation strategies based on the simulated migration and reaction characteristics of different ionic species. In the short term, controlling the pH of the injected water as well as the concentrations of Ca2+ and SO42− can help avoid supersaturation of carbonate and sulfate minerals, thereby reducing the risk of precipitation. In the mid-term, strategies such as mixed water injection or pulsed injection can improve water–rock contact uniformity and mitigate unstable flow caused by density gradients. In the long term, enhanced real-time monitoring and adaptive management are recommended, using reactive transport modeling to dynamically evaluate ion migration and mineral evolution trends, thus enabling timely adjustments to injection strategies.

Overall, the regulatory effects of alkaline water must strike a balance between promoting beneficial reactions and suppressing mineral precipitation and clogging. Through dynamic chemical control, it is possible to effectively steer the water–rock reaction pathways and manage the advancement of the injection front—both of which are crucial for improving the operational stability and extending the service life of geothermal systems.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the evolution of water–rock interaction pathways and key mechanisms in carbonate geothermal reservoirs under different injection water chemistries through the combined application of static experiments, PHREEQC inverse modeling, and forward reactive transport simulations. Experimental results demonstrated that the pH and ionic composition of the injection fluid significantly influence mineral dissolution–precipitation behavior. Alkaline regulation was shown to suppress calcite precipitation while enhancing the sustained dissolution of dolomite and silicate minerals. The inverse simulations effectively identified the dominant reactive minerals and quantified their mass changes under various injection conditions, validating the ion concentration trends and mineralogical responses observed in the experiments and improving the understanding of reaction pathways. Forward simulations further extended the analysis by revealing the spatiotemporal evolution of the reactive system, clearly distinguishing the transport behaviors of reaction-controlled, physically migrating, and slow-releasing ions and their coupling with the development of the reactive zone. The results suggest that moderate alkaline regulation can improve water–rock reaction pathways, delay early-stage mineral precipitation, and promote silicate reactivity. These effects could potentially reduce clogging risks and improve reservoir injectivity. Overall, the findings provide theoretical support and parameter references for the optimization of injection–production strategies in medium–deep carbonate geothermal systems.

Author Contributions

Z.L.: writing—original draft, data curation, conceptualization, formal analysis, visualization. B.F.: writing—review and editing, supervision, resources, funding acquisition. K.A.: writing—review and editing, supervision, resources. J.S.: supervision, funding acquisition, project administration. S.H.: data curation, investigation, resources. Y.Y.: supervision, project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the following: Deep Earth Probe and Mineral Resources Exploration—National Science and Technology Major Project, No. 2024ZD1003601; The Open Fund of Observation and Research Station of Tianjin Low-Medium Temperature Geothermal Resources, Ministry of Natural Resources, No. TJDRYWZ-202403; and Sichuan Science and Technology Program, Grant No. 2024NSFSC0092.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, J. The current status of geothermal reinjection. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2003, 3, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson, V. Geothermal reinjection experience. Geothermics 1997, 26, 99–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Zarrouk, S.J.; O’Sullivan, M.J. Reinjection in geothermal fields: A review of worldwide experience. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, G.; Flovenz, O.G.; Hjartarson, A.; Hauksdottir, S.; Bodvarsson, R. Thermal Energy Extraction by Reinjection from the Laugaland Geothermal System in N-Iceland. 2000. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gudni-Axelsson/publication/244993313_Thermal_energy_extraction_by_reinjection_from_the_Laugaland_geothermal_system_in_N-Iceland/links/02e7e53bfabdf8a172000000/Thermal-energy-extraction-by-reinjection-from-the-Laugaland-geothermal-system-in-N-Iceland.pdf?origin=scientificContributions (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Lin, L.; Wang, L.C.; Zhao, S.M.; Wang, Y.P.; Hu, Y. A discussion of the factors affecting geothermal reinjection in the geothermal reservoir of porous type in Tianjin. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2008, 35, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.L.; Liu, Z.M.; Liu, Q.X.; Yan, X.J. Modeling of Geothermal Reinjection in Xi’an Geothermal Field, West China. Acta Geol. Sin. 2002, 23, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, X.; Xue, Y.Z.; Wang, F.H.; Guan, Y.L.; Zhou, C. Key technology of “heat extraction without water consumption” heating by developing mid-deep geothermal energy in the Guanzhong Basin. Dist. Heat. 2020, 4, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.X.; Wang, G.L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W.L.; Cao, S.W. Evaluation of shallow geothermal energy resources in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Plain based on land use. J. Groundw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, B.; Long, W. A Review of the Current Situation of the Rational Development and Utilization of Medium and Deep Geothermal Resources. In Proceedings of the Environmental Engineering National Academic Conference of 2019, Beijing, China, 30 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Yang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhou, J.; Shen, G.; Wang, W. The current application status and development trend of geothermal energy heating technology. Huadian Technol. 2021, 43, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Fang, C.H.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Fang, Q.; Shi, X.Y. Development Status and Revelation of Geothermal Recharge at Home and Abroad. Oil Drill. Technol. 2021, 43, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.Q.; Ye, X.Y.; Lu, Y.; Chi, B.M.; Steffen, B.; Yang, Y.S. Research progress on clogging during artificial groundwater recharge. Adv. Earth Sci. 2009, 24, 973–980. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Liu, X.; Zheng, T.; Yang, J. A review of recharge and clogging in sandstone aquifer. Geothermics 2020, 87, 101857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwer, H. Artificial recharge of groundwater: Hydrogeology and engineering. Hydrogeol. J. 2002, 10, 121–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Xu, T.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Tian, H.; Yuan, Y.; Zhu, H. Numerical investigation on the influence of CO2-induced mineral dissolution on hydrogeological and mechanical properties of sandstone using coupled lattice Boltzmann and finite element model. J. Hydrol. 2024, 639, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Pu, C.; Guo, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, C. Chemical Characteristics and Formation Mechanism of Geothermal Water in the Southern Region of Langfang, Hebei Province. Geol. Bull. 2022, 41, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, C.C.; Xiao, J.; Pi, J.G.; Sun, X.L. Application of PHREEQC in simulating hydrochemical formation of Tangshi geothermal water. Min. Eng. Res. 2018, 33, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J. Principles, caveats and improvements in databases for calculating hydrogeochemical reactions in saline waters from 0 to 200 °C and 1 to 1000 atm. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 55, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palandri, J.L.; Kharaka, Y.K. A Compilation of Rate Parameters of Water-Mineral Interaction Kinetics for Application to Geochemical Modeling; Open-File Report 2004-1068; US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2004.

- Uwakwe, O.C.; Riechelmann, S.; Reinsch, T.; Nehler, M.; Immenhauser, A. Review of Carbonate Rock Experiments at Different Pressure and Temperature Conditions in the Context of Geothermal Energy Exploitation. Geosciences 2025, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, R.; Götz, E.; Schlatter, N.; Schubert, G.; Weinert, S.; Schmidt, S.; Kolb, U.; Sass, I. Fluid–Rock Interactions in Geothermal Reservoirs, Germany: Thermal Autoclave Experiments Using Sandstones and Natural Hydrothermal Brines. Aquat. Geochem. 2022, 28, 63–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmat, K.; Cheng, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Li, J. CO2-Water-rock interactions in carbonate formations at the Tazhong Uplift, Tarim Basin, China. Minerals 2022, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, X. In Situ Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Observation of Pore Fractures and Permeability Evolution in Rock and Coal under Triaxial Compression. J. Energy Eng. 2025, 151, 04025036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Hu, W.; Wan, Y.; Cao, J.; Lv, C.; Wang, R.; Cui, M. Supercritical CO2-involved water–rock interactions at 85 °C and partial pressures of 10–20 MPa: Sequestration and enhanced oil recovery. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2017, 35, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.L.; Wei, C.; Li, X.B.; Deng, Z.; Li, M.T.; Fan, G. Optimization of NaOH–Na2CO3 brine purification method: From laboratory experiments to industrial application. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 296, 121367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Yu, C.C.; Jiang, Z.C.; Shang, J.; Zhang, L.H. Experimental study on treatment of heating tailwater from Lindian geothermal field in northern Songnen Basin. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2021, 48, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmslykke, H.D.; Weibel, R.; Olsen, D.; Anthonsen, K.L. Geochemical Reactions upon Injection of Heated Formation Water in a Danish Geothermal Reservoir. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2023, 7, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendula, E.; Albrecht, R.; Conceição de Castro, C.; Keresztény-Borbás, E.; Szabó-Krausz, Z.; Kovács, J. Characteristics of Heat-Depleted Thermal Water Re-Injection-Induced Water–Rock Interactions in a Sandstone Reservoir Containing Carbonate and Silicate Minerals (Szentes, Hungary). Minerals 2025, 15, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhang, G.; Shangguang, S.; Qi, X.; Li, X.; Qiao, Y.; Xu, J. Study on the Interaction between Granite-Type Dry Hot Rock Bodies and Different Injection Water Bodies. Acta Geol. Sin. 2020, 94, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Liu, X.; Barry, D.A. The Application of PHREEQC in Groundwater Solute Reaction-Migration Simulation. Hydrogeol. Eng. Geol. 2004, 31, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.H. Numerical Simulation Study on Reactive Transport of Heavy Metals in Porous Media. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University, Qingdao, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson, H.C.; Kirkham, D.H.; Flowers, G.C. Theoretical prediction of the thermodynamic behavior of aqueous electrolytes by high pressures and temperatures; IV, Calculation of activity coefficients, osmotic coefficients, and apparent molal and standard and relative partial molal properties to 600 degrees C and 5 kb. Am. J. Sci. 1981, 281, 1249–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Tao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Kang, B. Experimental study on the water–rock interaction mechanism in a groundwater heat pump reinjection process. J. Water Clim. Change 2022, 13, 1516–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Deng, X.; Gao, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, F.; Han, J. Insight into the Process and Mechanism of Water–Rock Interaction in Underground Coal Mine Reservoirs Based on Indoor Static Simulation Experiments. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 36387–36402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Rose, P.; Fayer, S.; Pruess, K. Numerical Simulation Study of Silica and Calcite Dissolution Around a Geothermal Well by Injecting High pH Solutions with Chelating Agent; Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brantley, S.; Kubicki, J.; White, A. Kinetics of Water-Rock Interaction; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brantley, S.L.; Mellott, N.P. Surface area and porosity of primary silicate minerals. Am. Mineral. 2000, 85, 1767–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghici, R.M.; Oude Essink, G.H.P.; Hartog, N.; Sommer, W. Integrated assessment of variable density–viscosity groundwater flow for a high temperature mono-well aquifer thermal energy storage (HT-ATES) system in a geothermal reservoir. Geothermics 2015, 55, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Kang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhuo, L.; Gao, J.; Yuan, W.; Xing, Y. Flow Path of the Carbonate Geothermal Water in Xiong’an New Area, North China: Constraints From 14C Dating and H-O Isotopes. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 782273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Ji, Y.; Ma, Z.; Wan, H.; Yang, D.; Ji, H.; Bao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, C.; Lu, K. Formation Mechanism and Development Patterns of Karst Thermal Reservoirs in the Wumishan Formation, Xiong’an New Area. J. Paleogeography 2023, 25, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Cai, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, L.; Li, S. Feasibility Study on Geothermal Dolomite Reservoir Reinjection with Surface Water in Tianjin, China. Water 2024, 16, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V. Evaluation of Potential Geochemical Responses to Injection in the Forge Geothermal Reservoir, Utah. 2019. Available online: https://gdr.openei.org/files/1247/Patil_FORGE_FinalReport_042019.pdf (accessed on 22 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).