Abstract

Background/Objectives: Big data analysis has revolutionized medical research, making it possible to analyze vast amounts of data and gain valuable insights that were previously impossible to obtain. Our knowledge of the characteristics of vitamin D sufficiency is primarily based on data from a limited number of observations, generally spanning a few years at most. Methods: Here at the Medical Faculty of the University of Debrecen, the big data approach has allowed us to analyze trends in vitamin D status using nearly 60,000 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentration results from 2000 onwards. Results: Apart from analyzing the well-known phenomenon of seasonality in 25(OH)D concentration, we observed a trend in test requests, which increased from a few hundred in 2000 to almost 10,000 in 2020. Of particular interest is the change in the gender gap in test requests. In previous years, test requests were primarily from women, but by the end of the analysis period, a significant number of requests were from men as well. Since the data set includes all age groups, we analyzed 25(OH)D concentration for incremental age sets of five years, from a few months to 100 years old. The prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency (<75 nmol/L) was clearly demarcated among various years of observation, age groups, sexes, and seasons. Our data was particularly valuable for analyzing the effect of the methodology used for 25(OH)D determination. Three different methodologies were used during the study period, and clear, statistically significant bias was observed. Conclusions: Our results clearly demonstrate the effect of the methodology used to determine 25(OH)D concentrations on vitamin D status, explicitly highlighting the urgent need to standardize the various platforms used to measure this important analyte and its consequences for public health.

1. Introduction

The concept of big data in nutritional epidemiology has gained traction, with numerous large-scale prospective studies accumulating over the past 50 years [1]. While traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard for intervention studies, recent large-scale vitamin D3 RCTs have not yielded significant primary results [2]. A recent critical appraisal indicates that the reported outcomes and methodological constraints of these RCTs should guide the design of future vitamin D and nutrition interventions, emphasizing the need for a more individualized or precision-based approach [3]. An alternative approach involves segregating participants based on their responsiveness to vitamin D3 supplementation and measuring genome-wide parameters over multiple time points

Studies comparing vitamin D data across different years have yielded mixed results. A population-based study in northern Sweden found no clear trend in 25-hydroxyvitamin D 25(OH)D concentrations between 1986 and 2014 [4]. However, an analysis of US population data revealed lower serum 25(OH)D concentrations in 2000–2004 compared to 1988–1994, partly due to assay changes and factors like increased body mass index and sun protection [5]. The reliability of single 25(OH)D measurements over time has been examined, with one study finding a moderate correlation (r = 0.75) between two measurements taken within a year [6]. These studies highlight the importance of considering methodological factors when comparing vitamin D data across different time periods.

Seasonal variation in 25(OH)D concentrations is well-documented, with the lowest concentrations typically observed in winter and the highest in summer/autumn [7,8,9]. This seasonality can significantly impact health risk assessments and clinical decision-making [7]. Studies have shown that vitamin D deficiency prevalence can be approximately double in winter/spring compared to summer/autumn [8,9,10,11]. Researchers emphasize the importance of considering blood sampling seasonality as a crucial preanalytical factor in vitamin D assessment [8,9].

Lippi et al. reported no significant differences in 25(OH)D concentrations or deficiency prevalence across age groups or genders in their study conducted in north-east Italy [12]. Malyavskaya et al. observed high frequencies of vitamin D deficiency in all age groups in Arkhangelsk, Russia, with the highest prevalence being in adolescents and adults [13]. Yeşiltepe-Mutlu et al. found that children under 3 years old in Turkey had significantly higher vitamin D levels compared to other age groups, likely due to a national supplementation program [14]. They also noted lower levels in adults, suggesting a need for supplementation in older populations [14]. These findings highlight the complexity of vitamin D status across populations and emphasize the importance of targeted interventions.

The present study aimed to draw temporal inferences on gender disparity, age groups referred, seasonal variability and methodology of analyses, using a big data approach in the framework of a single regional medical healthcare provider.

2. Materials and Results

Anonymized medical data from the year 2000 onwards is available for research purposes at the Medical Faculty of the University of Debrecen. Anonymization is assured using the pseudonymization system of the UDBD Health data warehouse, in accordance with University of Debrecen data warehouse regulations. This Microsoft Azure Cloud-based UDBD-Health database was used to retrieve all 25(OH)D measurement data between 12 January 2000 and 31 December 2020. At the University of Debrecen, the Institutional Research Ethics Committee has permitted the use of anonymized data generated during standard healthcare for research purposes (Permission number—DE RKEB/IKEB 5404-2020 issued on 13 January 2020). No exclusion criteria were applied. Apart from the 25(OH)D concentrations, the date of the measurement, sex and the age of the patient were also retrieved. Information about the date when the methodology used to measure 25(OH)D was changed was available from the laboratory. 25(OH)D concentrations <75 nmol/L and ≥75 nmol/L were coded as insufficient and sufficient, respectively. The in-house developed R (R version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) statistical program was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistical summaries, FDR correction and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test were performed. Figures were generated using the R (version 4.2.2) software. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

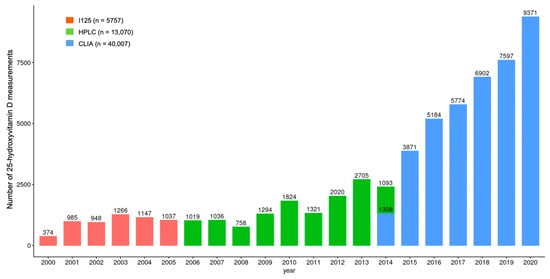

As part of routine healthcare, a total of 58,834 test results were identified that belonged to 31,710 patients (22,447 women and 9263 men). The number of tests per year showed an increasing tendency over time. The number of tests conducted in 2020 was 25 times that in 2001 (Figure 1). During the study period, three different analytical methods, a radioimmunoassay (RIA) (before 30 January 2006 (n = 5757)), high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (between 30 January 2006 and 16 June 2014 (n = 13,070)) and a chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) (from 16 June 2014 (n = 40,007)), were used for 25(OH)D determination (Figure 1.). The inter-assay CV for the I125 radioimmunoassay (Diasorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA), high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Jasco HPLC system (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) and Bio-Rad reagent kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and the automated Liaison DiaSorin total 25(OH)D chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN, USA) was <13%, <3.5% and <7.8%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Differences in the number of 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurements over the study period. I125: Radioimmunoassay; HPLC: High-pressure liquid chromatography; CLIA: Chemiluminescence immunoassay.

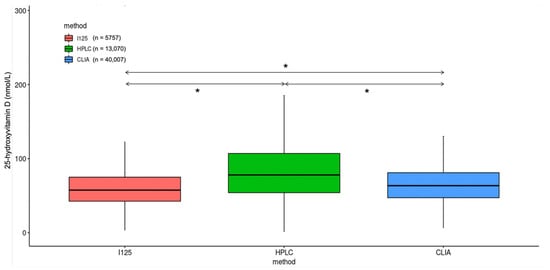

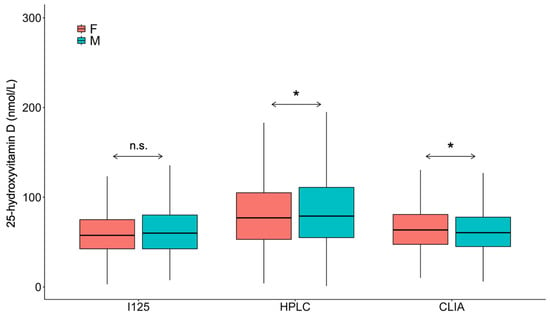

There was a statistically significant difference between the average 25(OH)D concentrations when comparing the test results measured on the different analytical platforms, particularly concentrations measured with HPLC being higher than with RIA and CLIA (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Difference in measured 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations using radioimmunoassay (I125), high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) and chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA). * p < 0.001.

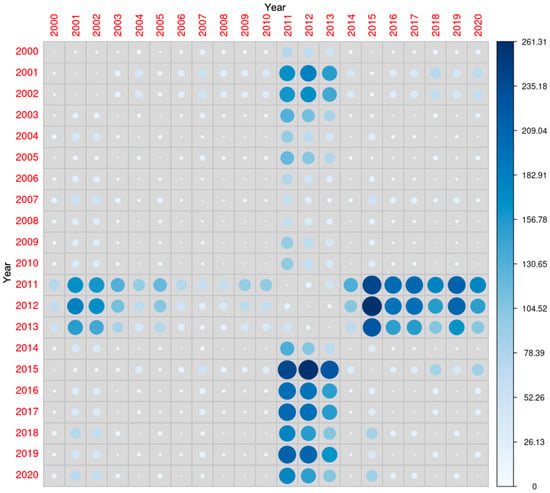

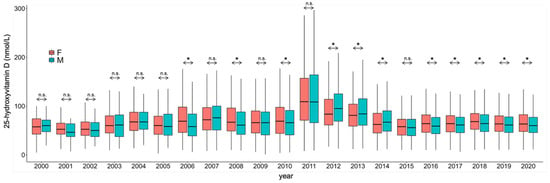

Although 25(OH)D concentrations were significantly different when comparing multiple years, the average concentrations were the highest in the years 2011, 2012 and 2013 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during the study period. The diameter of each circle and the intensity of its color shading denote the magnitude of disparity between the years represented along the x- and y-axes. Larger diameters and darker color tones correspond to a greater degree of difference between the two years under comparison.

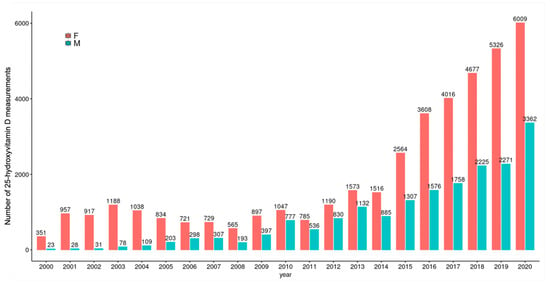

In the study period, there was a gradual increase in the number of tests per year for both sexes, an increase of 6 (n = 957 in 2001, n = 6009 in 2020) and 120 (n = 28 in 2001, n = 3362 in 2020) times was observed for women and men, respectively. Even though there was an increase in testing for men, women were still tested twice as frequently as men in 2020. In 2001, 97% of the results were from women and only 3% from men; this changed to 64% in women and 36% in men in 2020 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Frequency of testing by gender. F: Female, M: Male.

Although, when comparing average concentrations during the study period, there was no difference in 25(OH)D concentrations when comparing the two sexes (69 ± 7 nmol/L (women) vs. 70 ± 8 nmol/L (men); p > 0.05), men had significantly higher average concentrations when determinations were carried out with the HPLC methodology (Figure 5) and there were several years when there was a statistically significant difference between the two sexes (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Overall gender difference in 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. F: Female; M: Male; I125: Radioimmunoassay; HPLC: High-pressure liquid chromatography; CLIA: Chemiluminescence immunoassay. * p < 0.001. n.s.: No significance.

Figure 6.

Gender differences in 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during the study period. F: Female; M: Male. * p < 0.001. n.s.: No significance.

Over the period when the RIA methodology was in use, no significance was found when comparing the two sexes. When using HPLC, in 2006, 2008 and 2010, women had higher averages, and in 2012, 2013 and 2014, men were higher. Except for the year 2015 (where women had non-significantly higher values), in all the other years where the CLIA methodology was used, women had significantly higher vitamin D concentrations.

During the overall study period, there was no significant change in the percentage of vitamin D-sufficient patients (Table 1). Hypovitaminosis D was defined as 25(OH)D levels <75 nmol/L, as suggested by Dawson-Hughes et al. [15].

Table 1.

Gender distribution of the vitamin D insufficient and sufficient cases in each year.

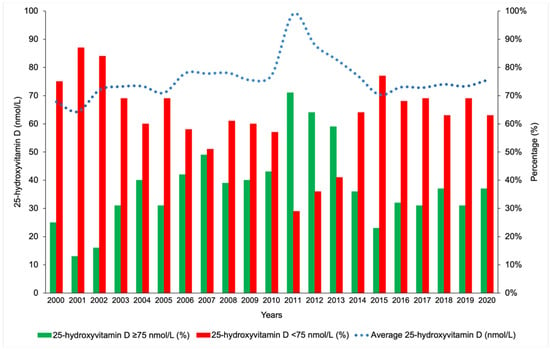

It was particularly interesting to note that within the study period spanning between 2000 and 2020, the average 25(OH)D concentrations and the percentage of sufficient vitamin D status were the highest during the years 2011, 2012 and 2013 when the methodology used was HPLC (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Trend of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during the study period.

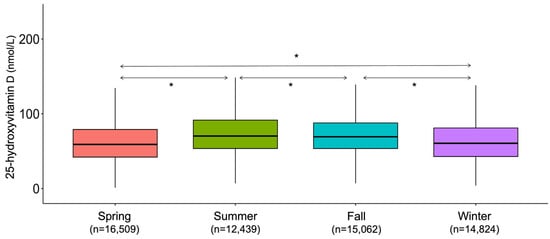

Seasonal variation was pronounced during the study period (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Seasonality trends during the study period. * p < 0.001.

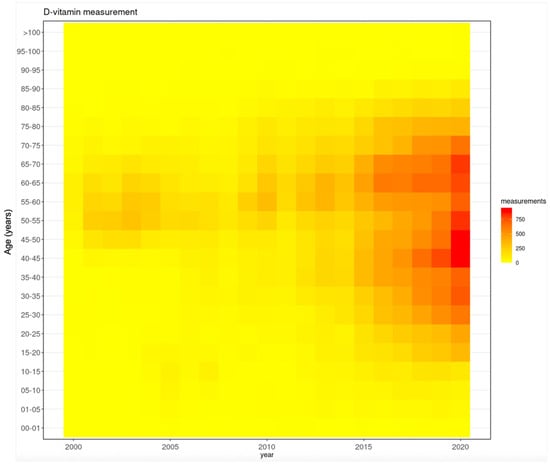

In the early 2000s, the majority of tests were conducted on those between 45 and 65 years of age. From 2010 onwards, this age range widened to 10–85 years, and the highest number of tests was in those from 40 to 45 and 60 to 65 years (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Trends in testing frequency in the various age groups during the study period.

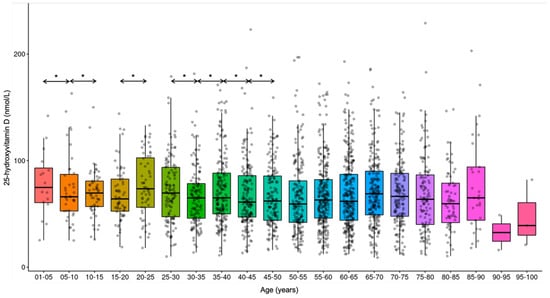

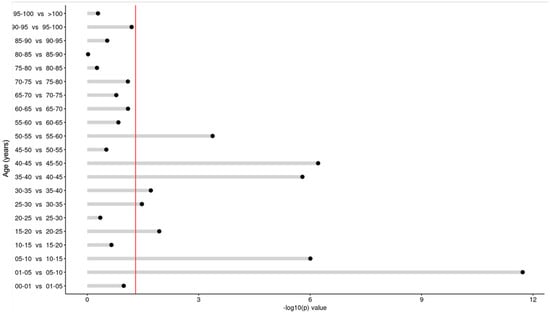

Comparing the age groups (years) sequentially, significant differences were noticed in the average vitamin D concentrations: 0–1 yrs vs. 1–5 yrs (1–5 yrs higher; p < 0.001), 1–5 yrs vs. 5–10 yrs (5–10 yrs lower; p < 0.001), 5–10 yrs vs. 10–15 yrs (10–15 yrs higher; p < 0.001), 15–20 yrs vs. 20–25 yrs (20–25 yrs higher; p < 0.001), 25–30 yrs vs. 30–35 yrs (30–35 yrs lower; p < 0.001), 30–35 yrs vs. 35–40 yrs (35–40 yrs higher; p < 0.001), 35–40 yrs vs. 40–45 yrs (40–45 yrs lower; p < 0.001), 40–45 yrs vs. 45–50 yrs (45–50 yrs higher; p < 0.001). (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Trends in 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the various age groups. * p < 0.001.

Figure 11.

Difference in vitamin D concentrations in sequential comparison of the age groups. The red line depicts the statistically significant value limit.

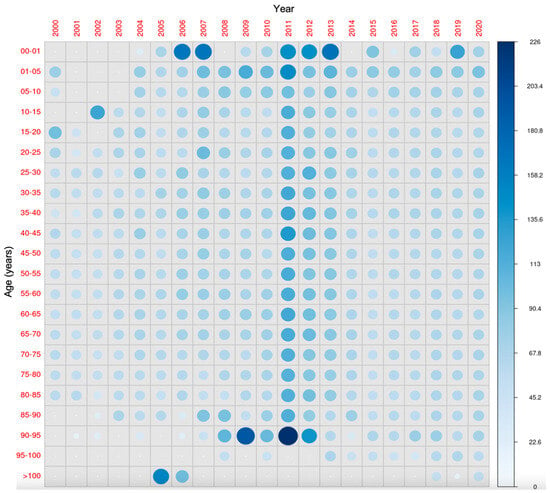

Figure 12 shows the comparison across all age groups during the study period. It is observed that after the early years, when vitamin D supplementation is compulsory, the concentrations tend to decrease in the later years of childhood. Such changes are not evident in the adult age groups.

Figure 12.

All-age-groups comparison of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations during the study period. The diameter of each circle and the intensity of its color shading denote the magnitude of the disparity between the years (x-axis) and age groups (y-axis). Larger diameters and darker color tones correspond to a greater degree of difference between the two years (for the same age group) and age groups (in the same year) under comparison.

3. Discussion

In recent years, researchers have leveraged the power of large-scale data analysis to uncover valuable insights into the prevalence and patterns of vitamin D sufficiency and insufficiency across diverse populations (Table 2) [4,5,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Table 2.

Big data studies on Vitamin D.

One key finding from this body of research is the estimation of the percentage of individuals with sufficient versus insufficient 25(OH)D concentrations. Numerous large-scale studies have consistently reported that a significant proportion of the global population, often exceeding 50%, exhibits suboptimal vitamin D status. This widespread prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency is a major public health concern, as inadequate 25(OH)D concentrations have been linked to a range of adverse health outcomes, including increased risks of bone loss, cardiovascular disease, many types of cancer and other chronic conditions [30,31,32]. The sheer scale of this problem underscores the critical need for targeted interventions and public health strategies to address this pervasive issue and improve overall vitamin D status within the population.

Furthermore, researchers have explored the temporal trends of 25(OH)D levels, conducting comparative analyses across multiple years. These in-depth investigations have unveiled valuable insights into the intricate interplay between vitamin D status and various demographic factors, such as seasonal variations, age, and gender [33,34]. The findings from these studies suggest that 25(OH)D levels may exhibit distinct patterns among different population subgroups, underscoring the need for a more nuanced understanding of this complex relationship [34].

A deeper examination of the big data on 25(OH)D has revealed significant differences in vitamin D status between men and women, as well as across different age groups. Some studies have found that older adults and women tend to have lower 25(OH)D concentrations compared to younger individuals and men, respectively [25]. These observed disparities highlight the importance of developing targeted public health interventions and educational campaigns to address the specific needs of these population subgroups. By tailoring strategies to address the unique vitamin D-related challenges faced by different demographics, healthcare providers and policymakers can work towards more effective and equitable solutions to improve overall vitamin D sufficiency within the broader population.

The determination of circulating 25(OH)D concentrations is recommended solely for patients deemed to be at risk of vitamin D deficiency by current guidelines, where the different risk factors are exhaustively enumerated [35,36].

Being the most abundant vitamin D metabolite in the bloodstream, 25(OH)D is considered the most optimal marker of vitamin D status. The current evidence points to 25(OH)D levels showing significant association with clinical endpoints, e.g., bone mineral density, fracture risk, falls, numerous pleotropic effects and mortality [25,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Having a relatively long half-life of 2–3 weeks, serum levels rarely oscillate within a short period; furthermore, 25(OH)D reflects the amount of both intake and production [43]. Additionally, 25(OH)D levels change in accordance with sunlight (UV) exposure and vitamin D supplementation [38,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51].

Although considered an optimal metabolite reflecting vitamin D status, the determination of 25(OH)D concentrations is still challenging despite recent technological improvements [52]. It is a prerequisite that 25(OH)D assays should measure both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3, i.e., total 25(OH)D. Adding to the technical challenges is the strongly hydrophobic nature of 25(OH)D that circulates in bound form with vitamin D-binding protein (DBP), albumin and lipoproteins; as such, stripping 25(OH)D from its carriers is a preliminary step in the analytics of total 25(OH)D concentrations [53].

Adding further to the technical difficulties is the fact that 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 have non-similar affinity constants for their carrier proteins; as such, ideal dissociation is a prerequisite for the precise quantification of total 25(OH)D levels. Since there is no room for organic solvent extraction, this can be a limiting step in automated immunoassays, in contrast to manual radioimmunoassays and chromatographic and binding protein assays. Alternative releasing agents are usually used in automated immunoassays that do not always achieve the desired dissociation. Additionally, due to the above-mentioned technical lapses, determination with automated methodology is usually less reliable when DBP levels are elevated, e.g., in pregnancy, estrogen therapy or renal failure [54,55,56,57].

Although ample data on 25(OH)D concentrations exist, standardizing 25(OH)D values remains challenging. To address this issue, the Vitamin D Standardization Program (VDSP) has introduced protocols for standardizing existing 25(OH)D data from national surveys around the world [17,58,59,60,61]. In brief, the VDSP protocol involves identifying a batch of samples from the sample pool primarily used to determine 25(OH)D in the given survey. These samples are then reanalyzed using the reference measurement procedures (RMP) of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Ghent University. The results are then used to correct the initially measured 25(OH)D concentrations of the sample pool. While the protocol is well-defined, the recommended RMP requires specialized equipment and expertise primarily available at specialized laboratories. Furthermore, the financial aspect may be a limitation. Nonetheless, Jakab et al. have proposed correcting the measured 25(OH)D values using the linear regression bias from the NIST “total” target values reported by the Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme (DEQAS) [62].

All clinical and research laboratories are strongly encouraged to participate in accuracy-based external quality assessment programs, such as those offered by the College of American Pathologists (CAP) or DEQAS. Providers of these programs should conduct regular commutability studies to ensure that their reported results are consistent with clinical outcomes obtained across various assay methods. Furthermore, manufacturers are also encouraged to participate in the Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program (VDSCP).

Significant methodological progress has occurred in the measurement of 25(OH)D and its metabolites. A recent review comprehensively evaluated the capabilities of available commercial assay platforms [63]. LC–MS/MS continues to be recognized as the definitive method for the accurate quantification of clinically relevant, circulating vitamin D metabolites.

4. Limitations

The data analyzed is taken from the database of the University of Debrecen. Although it is one of the biggest healthcare providers in the country, it caters mainly to the needs of the population residing in the northern region of Hungary. Furthermore, the data presented inherently belong to the healthcare setting and do not represent a population-based survey. As such, the deductions of our study may not be readily applicable to the whole population. Furthermore, analyses of the result categories of <50 nmol/L and <25 nmol/L were not performed.

5. Conclusions

Our results clearly demarcate the effect of the methodology used to determine 25(OH)D vitamin concentrations on Vitamin D status, explicitly highlighting the urgency of the standardization of various platforms used to measure this ominous analyte with grave public health importance and, therefore, consequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. and H.P.B.; methodology, S.R., M.E. and H.P.B.; formal analysis, S.R., M.E. and H.P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R., M.E., E.B., L.H., B.E.T., S.B., E.K., L.J., A.P.B.-B., W.B.G. and H.P.B.; writing—review and editing, W.B.G. and H.P.B.; supervision, H.P.B.; project administration, S.R.; funding acquisition, E.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was carried out within the framework of project TKP2021-NKTA-34, with support from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed by the TKP2021-NKTA grant program. The APC was funded by the University of Debrecen, Medical Faculty.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable as the study used anonymized data, and no patient-identifiable information was collected or processed.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| CAP | College of American Pathologists |

| CLIA | Chemiluminescence immunoassay |

| DBP | Vitamin D binding protein |

| DEQAS | Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme |

| F | Female |

| HPLC | High-pressure liquid chromatography |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry |

| M | Male |

| NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| RIA | Radioimmunoassay |

| RMP | Reference measurement procedures |

| VDSP | Vitamin D Standardization Program |

| VDSCP | Vitamin D Standardization-Certification Program |

References

- Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Big data and systematic reviews in nutritional epidemiology. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gospodarska, E.; Ghosh Dastidar, R.; Carlberg, C. Intervention Approaches in Studying the Response to Vitamin D3 Supplementation. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Trummer, C.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Grubler, M.R.; Verheyen, N.D.; Odler, B.; Karras, S.N.; Zittermann, A.; Marz, W. Critical Appraisal of Large Vitamin D Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerhays, E.; Eliasson, M.; Lundqvist, R.; Soderberg, S.; Zeller, T.; Oskarsson, V. Time trends of vitamin D concentrations in northern Sweden between 1986 and 2014: A population-based cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 3037–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looker, A.C.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Lacher, D.A.; Schleicher, R.L.; Picciano, M.F.; Yetley, E.A. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status of the US population: 1988–1994 compared with 2000–2004. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.M.; Graubard, B.I.; Dodd, K.W.; Iwan, A.; Alexander, B.H.; Linet, M.S.; Freedman, D.M. Variability and reproducibility of circulating vitamin D in a nationwide U.S. population. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosecrans, R.; Dohnal, J.C. Seasonal vitamin D changes and the impact on health risk assessment. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 47, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonelli, P.; Buonocore, R.; Aloe, R.; Lippi, G. Blood Sampling Seasonality as an Important Preanalytical Factor for Assessment of Vitamin D Status. J. Med. Biochem. 2016, 35, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadakis, G.; Keramidas, I.; Kakava, K.; Pappa, T.; Villiotou, V.; Triantafillou, E.; Drosou, A.; Tertipi, A.; Kaltzidou, V.; Pappas, A. Seasonal variation of serum vitamin D among Greek female patients with osteoporosis. In Vivo 2015, 29, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Hypponen, E.; Power, C. Hypovitaminosis D in British adults at age 45 y: Nationwide cohort study of dietary and lifestyle predictors. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroll, M.H.; Bi, C.; Garber, C.C.; Kaufman, H.W.; Liu, D.; Caston-Balderrama, A.; Zhang, K.; Clarke, N.; Xie, M.; Reitz, R.E.; et al. Temporal relationship between vitamin D status and parathyroid hormone in the United States. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Montagnana, M.; Meschi, T.; Borghi, L. Vitamin D concentration and deficiency across different ages and genders. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2012, 24, 548–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malyavskaya, S.; Kostrova, G.; Kudryavtsev, A.V.; Lebedev, A. Low vitamin D levels among children and adolescents in an Arctic population. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesiltepe-Mutlu, G.; Aksu, E.D.; Bereket, A.; Hatun, S. Vitamin D Status Across Age Groups in Turkey: Results of 108,742 Samples from a Single Laboratory. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson-Hughes, B.; Heaney, R.P.; Holick, M.F.; Lips, P.; Meunier, P.J.; Vieth, R. Estimates of optimal vitamin D status. Osteoporos. Int. 2005, 16, 713–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smirnova, D.V.; Rehm, C.D.; Fritz, R.D.; Kutepova, I.S.; Soshina, M.S.; Berezhnaya, Y.A. Vitamin D status of the Russian adult population from 2013 to 2018. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarafin, K.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Tian, L.; Phinney, K.W.; Tai, S.; Camara, J.E.; Merkel, J.; Green, E.; Sempos, C.T.; Brooks, S.P. Standardizing 25-hydroxyvitamin D values from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleicher, R.L.; Sternberg, M.R.; Lacher, D.A.; Sempos, C.T.; Looker, A.C.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Yetley, E.A.; Chaudhary-Webb, M.; Maw, K.L.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; et al. The vitamin D status of the US population from 1988 to 2010 using standardized serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D shows recent modest increases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenberg, M.; Scheidt-Nave, C.; Busch, M.A.; Thamm, M.; Rieckmann, N.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Dowling, K.G.; Skrabakova, Z.; Cashman, K.D.; Sempos, C.T.; et al. Implications of standardization of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D data for the evaluation of vitamin D status in Germany, including a temporal analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, A.; Donneau, A.F.; Streel, S.; Kolh, P.; Chapelle, J.P.; Albert, A.; Cavalier, E.; Guillaume, M. Vitamin D deficiency is common among adults in Wallonia (Belgium, 51 degrees 30’ North): Findings from the Nutrition, Environment and Cardio-Vascular Health study. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hintzpeter, B.; Mensink, G.B.; Thierfelder, W.; Muller, M.J.; Scheidt-Nave, C. Vitamin D status and health correlates among German adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrenya, N.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Melhus, M.; Broderstad, A.R.; Brustad, M. Vitamin D status in a multi-ethnic population of northern Norway: The SAMINOR 2 Clinical Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, M.J.; Murray, B.F.; O’Keane, M.; Kilbane, M.T. Rising trend in vitamin D status from 1993 to 2013: Dual concerns for the future. Endocr. Connect. 2015, 4, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, N.O.; Jorgensen, M.E.; Friis, H.; Melbye, M.; Soborg, B.; Jeppesen, C.; Lundqvist, M.; Cohen, A.; Hougaard, D.M.; Bjerregaard, P. Decrease in vitamin D status in the Greenlandic adult population from 1987–2010. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginde, A.A.; Liu, M.C.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. Demographic differences and trends of vitamin D insufficiency in the US population, 1988–2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, K.A.; Storandt, R.J.; Afful, J.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Schleicher, R.L.; Gahche, J.J.; Potischman, N. Vitamin D status in the United States, 2011–2014. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Hower, J.; Knoll, A.; Ritzenthaler, K.L.; Lamberti, T. No improvement in vitamin D status in German infants and adolescents between 2009 and 2014 despite public recommendations to increase vitamin D intake in 2012. Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 58, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, L.; Mirani, S.; Girgis, M.M.F.; Racz, S.; Bacskay, I.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Toth, B.E. Six years’ experience and trends of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D concentration and the effect of vitamin D3 consumption on these trends. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1232285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuuminen, T.; Sorsa, M.; Tornudd, M.; Lahteenmaki, P.L.; Poussa, T.; Suonsivu, P.; Pitkanen, E.M.; Antila, E.; Jaakkola, K. Long-term nutritional trends in the Finnish population estimated from a large laboratory database from 1987 to 2020. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattoa, H.P.; Konstantynowicz, J.; Laszcz, N.; Wojcik, M.; Pludowski, P. Vitamin D: Musculoskeletal health. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Annweiler, C.; Duval, G.; Karras, S.; Tirabassi, G.; Salvio, G.; Balercia, G.; Kimball, S.; Kotsa, K.; Mascitelli, L.; et al. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: From atherosclerosis to myocardial infarction and stroke. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 230, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz, A.; Grant, W.B. Vitamin D and Cancer: An Historical Overview of the Epidemiology and Mechanisms. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Boucher, B.J. Seasonal variations of U.S. mortality rates: Roles of solar ultraviolet-B doses, vitamin D, gene exp ression, and infections. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 173, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Fakhoury, H.M.A.; Karras, S.N.; Al Anouti, F.; Bhattoa, H.P. Variations in 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in Countries from the Middle East and Europe: The Roles of UVB Exposure and Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M.; Endocrine, S. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demay, M.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Bikle, D.D.; Diab, D.L.; Kiely, M.E.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Lips, P.; Mitchell, D.M.; Murad, M.H.; Powers, S.; et al. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1907–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Giovannucci, E.; Willett, W.C.; Dietrich, T.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemel, M.; von Domarus, C.; Klatte, T.O.; Kessler, S.; Schlie, J.; Meier, S.; Proksch, N.; Pastor, F.; Netter, C.; Streichert, T.; et al. Bone mineralization defects and vitamin D deficiency: Histomorphometric analysis of iliac crest bone biopsies and circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 675 patients. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobnig, H.; Pilz, S.; Scharnagl, H.; Renner, W.; Seelhorst, U.; Wellnitz, B.; Kinkeldei, J.; Boehm, B.O.; Weihrauch, G.; Maerz, W. Independent association of low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin d levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, M.; Sullivan, D.R.; Veillard, A.S.; McCorquodale, T.; Straub, I.R.; Scott, R.; Laakso, M.; Topliss, D.; Jenkins, A.J.; Blankenberg, S.; et al. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: A predictor of macrovascular and microvascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015, 38, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Cheng, R.Z.; Pludowski, P.; Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review of Risk Reduction Evidence. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Wimalawansa, S.J.; Pludowski, P.; Cheng, R.Z. Vitamin D: Evidence-Based Health Benefits and Recommendations for Population Guidelines. Nutrients 2025, 17, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Status: Measurement, Interpretation, and Clinical Application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woitge, H.W.; Knothe, A.; Witte, K.; Schmidt-Gayk, H.; Ziegler, R.; Lemmer, B.; Seibel, M.J. Circaannual rhythms and interactions of vitamin D metabolites, parathyroid hormone, and biochemical markers of skeletal homeostasis: A prospective study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2000, 15, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schottker, B.; Jorde, R.; Peasey, A.; Thorand, B.; Jansen, E.H.; Groot, L.; Streppel, M.; Gardiner, J.; Ordonez-Mena, J.M.; Perna, L.; et al. Vitamin D and mortality: Meta-analysis of individual participant data from a large consortium of cohort studies from Europe and the United States. BMJ 2014, 348, g3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zittermann, A.; Ernst, J.B.; Gummert, J.F.; Borgermann, J. Vitamin D supplementation, body weight and human serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D response: A systematic review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendenning, P.; Chew, G.T.; Seymour, H.M.; Gillett, M.J.; Goldswain, P.R.; Inderjeeth, C.A.; Vasikaran, S.D.; Taranto, M.; Musk, A.A.; Fraser, W.D. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in vitamin D-insufficient hip fracture patients after supplementation with ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol. Bone 2009, 45, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamberg, L.; Pedersen, S.B.; Richelsen, B.; Rejnmark, L. The effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on calciotropic hormones and bone mineral density in obese subjects with low levels of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin d: Results from a randomized controlled study. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, T.; Wong, Y.K.; Golombick, T. Effect of oral cholecalciferol 2,000 versus 5,000 IU on serum vitamin D, PTH, bone and muscle strength in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybchyn, M.S.; Abboud, M.; Puglisi, D.A.; Gordon-Thomson, C.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Mason, R.S.; Fraser, D.R. Skeletal Muscle and the Maintenance of Vitamin D Status. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, R.S.; Rybchyn, M.S.; Abboud, M.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C.; Fraser, D.R. The Role of Skeletal Muscle in Maintaining Vitamin D Status in Winter. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollis, B.W. Editorial: The determination of circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D: No easy task. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 3149–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, K.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Cavalier, E.; Phinney, K.; Sempos, C.T.; Ulmer, C.Z.; Vasikaran, S.D.; Vesper, H.; Heijboer, A.C. Recommendations on the measurement and the clinical use of vitamin D metabolites and vitamin D binding protein—A position paper from the IFCC Committee on bone metabolism. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 517, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, E.; Bacher, S.; Mery, S.; Le Goff, C.; Piga, N.; Vogeser, M.; Hausmann, M.; Cavalier, E. Performance characteristics of the VIDAS(R) 25-OH Vitamin D Total assay-comparison with four immunoassays and two liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods in a multicentric study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016, 54, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depreter, B.; Heijboer, A.C.; Langlois, M.R. Accuracy of three automated 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays in hemodialysis patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 415, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heijboer, A.C.; Blankenstein, M.A.; Kema, I.P.; Buijs, M.M. Accuracy of 6 routine 25-hydroxyvitamin D assays: Influence of vitamin D binding protein concentration. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalier, E.; Lukas, P.; Crine, Y.; Peeters, S.; Carlisi, A.; Le Goff, C.; Gadisseur, R.; Delanaye, P.; Souberbielle, J.C. Evaluation of automated immunoassays for 25(OH)-vitamin D determination in different critical populations before and after standardization of the assays. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 431, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkley, N.; Sempos, C.T.; Vitamin, D.S.P. Standardizing vitamin D assays: The way forward. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014, 29, 1709–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempos, C.T.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Binkley, N.; Jones, J.; Merkel, J.M.; Carter, G.D. Developing vitamin D dietary guidelines and the lack of 25-hydroxyvitamin D assay standardization: The ever-present past. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 164, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, K.D.; Dowling, K.G.; Skrabakova, Z.; Kiely, M.; Lamberg-Allardt, C.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Sempos, C.T.; Koskinen, S.; Lundqvist, A.; Sundvall, J.; et al. Standardizing serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D data from four Nordic population samples using the Vitamin D Standardization Program protocols: Shedding new light on vitamin D status in Nordic individuals. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 2015, 75, 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, K.D.; Kiely, M.; Kinsella, M.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.A.; Tian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lucey, A.; Flynn, A.; Gibney, M.J.; Vesper, H.W.; et al. Evaluation of Vitamin D Standardization Program protocols for standardizing serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D data: A case study of the program’s potential for national nutrition and health surveys. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakab, E.; Kalina, E.; Petho, Z.; Pap, Z.; Balogh, A.; Grant, W.B.; Bhattoa, H.P. Standardizing 25-hydroxyvitamin D data from the HunMen cohort. Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 1653–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, B.; Cavalier, E.; Bhattoa, H.P.; Perez-Lopez, F.R.; Lopez-Baena, M.T.; Perez-Roncero, G.R.; Chedraui, P.; Annweiler, C.; Della Casa, S.; Zelzer, S.; et al. Vitamin D testing: Advantages and limits of the current assays. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).