Abstract

Environmental education, implemented at both formal and informal levels, plays a significant role in the transformation process towards a Circular Economy (CE). In the Baltic Sea Region (BRS), the significant role of the forestry sector is worth noting, as it contributes to strengthening the CE agenda through the sustainable and circular management of wood processing waste. However, currently, environmental education on the potential uses of this waste, for the general public (including youth), students, and professionals, is quite limited. Therefore, this paper presents a conceptual approach to developing an education roadmap. The scope of work includes identifying the education gap in the forestry sector using a questionnaire survey among residents of the Baltic Sea Region, and then developing a concept for an education roadmap consistent with the CE assumptions. The presented concept of roadmap is a comprehensive document that analyses the educational needs, challenges, and opportunities related to the sustainable use of forest biomass in a given region. Strategic assumptions and educational priorities were identified and implemented in this document. Our findings contribute to aligning forestry education with broader environmental and economic goals in the Baltic Sea Region and beyond. This study supports the achievement of Sustainable Development Goals 4 (Quality Education), 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and 15 (Life on Land) by providing practical insights for advancing circular economy education in natural resource management.

1. Introduction

The shift towards a Circular Economy (CE) in the European Union (EU) signifies a fundamental change in how resources are managed and economic development is approached [1]. This strategy seeks to minimise waste, enhance resource efficiency, and create sustainable value chains across various sectors [2]. Within this context, the forestry sector in the Baltic Sea Region (BSR) is a cornerstone of both environmental sustainability and regional economic growth. Its contributions extend beyond traditional timber production to include carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and the provision of renewable alternatives to fossil-based materials. In the BSR, where forests are plentiful and deeply ingrained in the cultural and economic fabric, the forestry sector plays a crucial role [3].

The concept of bioeconomy pathways underscores the critical role of forestry in advancing the CE transition in the EU. Central to this process is the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into decision-making, which supports the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [4,5]. This involves fostering cross-sectoral cooperation, promoting industrial symbiosis, where the by-products or waste of one industry become resources for another, and enhancing resource efficiency. However, the BSR faces significant challenges owing to human activities and climate change, which affect the region’s biodiversity, land-use patterns, and forest resilience [6,7]. Consequently, the forestry sector must adapt to sustain essential ecosystem services, such as carbon capture and biodiversity preservation, while continuing to provide renewable raw materials in line with the CE principles of resource reuse and waste minimization [6].

The adoption of circular principles in forestry is increasingly being considered essential rather than optional. Circular strategies advocate for the cascading use of biomass, valorisation of by-products, and development of biorefineries that transform wood residues into biofuels, biochemicals, and biomaterials [8,9]. These approaches not only enhance resource efficiency but also reduce waste, embodying the core principles of circularity [10,11]. However, the sector faces significant constraints, including limited biomass availability owing to competing demands for energy, materials, and ecosystem conservation [12,13]. Additionally, challenges related to climate change, land-use conflicts, and biodiversity protection further complicate the sustainable management of forest resources [13].

The BSR exemplifies both the opportunities and complexities inherent in CE transitions. For instance, Sweden has emerged as a leader in bioenergy innovation, with approximately 96% of its heating energy sourced from bioenergy, while also investing in biorefineries that convert by-products from the pulp and paper industry into high-value materials [14]. In contrast, Latvia has expanded its forest cover and depends on woody biomass for nearly 40% of its energy mix, with wood pellets and chips as key export commodities [15]. These examples illustrate the diverse developmental trajectories within the region and underscore the need for harmonized strategies that balance economic growth, resource efficiency, and preservation of ecological integrity.

Environmental education is crucial for advancing the transition to CE within the forestry sector. Education serves as a catalyst for understanding and implementing circular practices by closing knowledge gaps among various stakeholders, such as local communities, students, forestry professionals, and policymakers [16,17]. However, the current educational landscape regarding the circular use of forestry residues and biomass is fragmented and inadequate, which may hinder the full realisation of the CE potential in the forestry sector. Additionally, the adoption of CE principles in forest-based supply chains is challenged by technical limitations, inconsistent global standards, and uneven knowledge dissemination [18]. Despite their essential role in CE innovation, startups and small enterprises often face unique challenges due to limited resources and institutional support, highlighting the need for targeted educational and policy interventions [19].

The intricacy of circular bioeconomy models necessitates a multifaceted educational approach that seamlessly integrates ecological knowledge, technological innovation and socio-economic understanding. This interdisciplinary perspective is crucial for developing comprehensive solutions to the challenges of CE implementation in forestry [20]. By fostering holistic awareness and practical competence, environmental education can empower stakeholders to make informed decisions, drive innovation, and contribute to sustainable forest resource management [17,21].

Despite the growing relevance of the CE for forest-based sectors, there is a notable lack of research systematically analysing educational gaps within forestry and bioeconomy learning pathways. Existing studies primarily address general sustainability competencies or focus on technological and policy aspects of the bioeconomy, while the structure, availability, and alignment of CE-related educational programs remain largely unexplored [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Importantly, there is no comprehensive framework that integrates empirical evidence on stakeholder needs across different countries with an assessment of existing educational materials and initiatives. This absence of comparative, multi-country, and multi-stakeholder analysis constitutes a critical research gap that this study seeks to address.

The impetus for this study arises from the growing demand for circular economy competencies within the forestry industry, such as resource circularity, digital monitoring, and cross-sector collaboration in the forestry industry. This demand is juxtaposed with the persistent fragmentation of training resources and limited inclusion of sector-specific content in educational curricula. As the industry transitions towards bio-based value chains, educational systems inadequately address these skill shortages, leading to uneven knowledge distribution and low stakeholder awareness.

Both formal and informal education play crucial roles in capacity building for the CE. Formal education, encompassing universities and Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), offers structured pathways for acquiring professional competencies in biorefinery processes and sustainable forest management. In contrast, informal education, including Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), workshops, non-governmental organisation (NGO) initiatives, and workplace training, fosters societal behavioural change, community engagement, and continuous skill enhancement, which are vital for industrial symbiosis and public adoption of circular practices. Consequently, this study developed an evidence-based Education Roadmap through stakeholder surveys (n = 1000), cluster analysis, and content review, aligning educational strategies with the circular economy needs of the BSR forestry sector.

This study seeks to identify and analyse the roles and contributions of key stakeholders in advancing CE principles within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors of the BRS. It emphasises how both formal and informal educational initiatives can enhance collaboration among academia, industry, policymakers, and society to promote sustainable and circular forestry practices. This study identifies critical actors, evaluates their awareness and engagement levels, and investigates how targeted educational strategies can boost cooperation, support innovation, and facilitate CE implementation. Unlike general stakeholder engagement frameworks, this study focuses on specific groups, such as forestry enterprises, research institutions, educators, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and local communities, to address existing educational gaps related to the sustainable and circular use of forest biomass. By elucidating stakeholder perspectives, this study lays the groundwork for developing a comprehensive Education Roadmap that could serve as a platform for multi-actor dialogue, knowledge exchange, and evidence-based policy development. Ultimately, this underscores the necessity for a more inclusive and collaborative approach to environmental education in forestry, reinforcing stakeholder-driven cooperation and aligning educational goals with CE principles to support the transition towards a sustainable and resource-efficient forest bioeconomy in the BRS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A Case Study: Forestry Sector in the Baltic Sea Region

This study employs a comparative case study approach across five BSR countries—Sweden (SE), Finland (FI), Lithuania (LT), Latvia (LV), and Poland (PL)—chosen for their robust forest-based economies, shared environmental challenges, and varying levels of circular economy (CE) implementation to achieve this aim (Figure 1). The BSR, a geographically and culturally diverse region encircling the Baltic Sea, encompasses Denmark, Estonia, Finland, northern Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Sweden, and occasionally the Kaliningrad region of Russia [29].

Figure 1.

Map of the BRS countries (in dark-green colour) showing in the five regional case studies.

Ecologically, the BSR extends along a north–south gradient, transitioning from temperate broadleaved to boreal coniferous forests [30]. This creates diverse forest mosaics shaped by natural disturbance regimes [31] that support high biodiversity [32]. Socially, the region includes a range of governance systems and historical trajectories, from long-established democracies to countries undergoing political and economic transitions, all of which influence environmental policies and resource management practices [33,34,35].

The forestry sectors in SE, FI, LT, LV, and PL produce significant amounts of residues, including bark, sawdust, chips, and needles, which remain largely underutilised despite their considerable potential for CE applications [36]. Most of these residues are still channelled into low-value energy production [37]. Sawmills in these countries generate over 1.48 billion kg of bark and 2.25 billion kg of sawdust annually, along with substantial quantities of chips, presenting opportunities for extracting high-value compounds (e.g., tannins and polyphenols) that have applications in adhesives, leather treatment, wastewater management, cosmetics, and food preservation [38,39].

The increasing focus on residue valorization has encouraged collaboration among industries, research institutions, and policymakers, positioning BSR as a potential leader in sustainable forestry and bio-based innovation. By advancing value-added uses of forestry by-products, resource efficiency can be enhanced, climate mitigation supported, economic opportunities stimulated and regional cooperation strengthened. This illustrates how the forestry sector can evolve in line with CE principles while maintaining economic relevance [36].

To better understand the importance of the forestry sector in the BSR, it is worth examining the situation in individual countries which—despite shared ecological conditions and similar economic challenges—have developed different models of forest management and resource utilisation. The analysis of selected case studies highlights both the differences in ownership structures, forestry traditions, and the role of forests in national economies, as well as the common pursuit of implementing the principles of sustainable development and the CE. A comparative overview of forestry characteristics and residue generation in the five countries is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key forestry characteristics and annual residue generation in the five BSR case study countries.

2.2. Data Collection and Analytical Approach

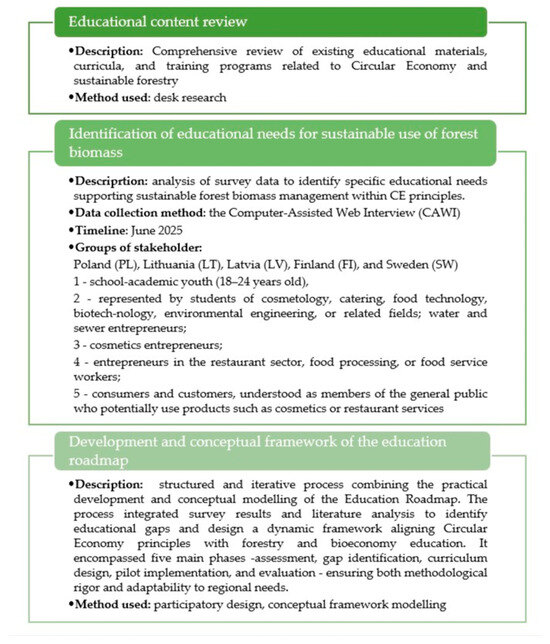

The methodological framework of this study was designed to conceptualize and develop an Education Roadmap supporting the implementation of CE principles in the forestry and bioeconomy sectors of the BSR. The approach combined elements of desk research, conceptual modelling, and empirical analysis based on a stakeholder-oriented survey. The process was divided into three consecutive stages, each building upon the findings of the previous one (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The research design for developing a conceptual framework.

2.2.1. Approach to Educational Content Review

The first stage of this research focused on identifying and verifying the scope of CE education within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors of the BRS. The objective was to establish an overview of existing educational frameworks, programmes, and training initiatives addressing CE-related topics. The research process is illustrated in Figure 2.

This stage applied the desk research method [42], involving systematic collection and analysis of data from scientific databases (Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar) and institutional sources, including the EU Learning Corner, FAO e-learning Academy, and the European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform. Reports and publications from organisations such as the European Commission, OECD, and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation were also reviewed to capture both academic and policy perspectives.

Searches were conducted using keywords such as “circular economy education”, “forestry education”, “bioeconomy learning”, “sustainable forest management”, “biomass utilisation”, “sustainability education”, “curriculum development”, “environmental training”, “lifelong learning”, “green skills”, “capacity building”, “educational roadmap”, “digital learning tools”, and “stakeholder engagement in education”. Only peer-reviewed or verified institutional resources published between 2014 and 2025 were included. The materials were classified by education type, thematic scope, and target audience. The findings provided the analytical foundation for identifying educational gaps and developing the conceptual Education Roadmap supporting CE implementation in the forestry sector.

2.2.2. Identification of Educational Needs for Sustainable Use of Forest Biomass

The identification of educational needs represents a key stage in developing the Education Roadmap for implementing CE principles within the forestry sector. This phase aimed to assess existing knowledge levels, evaluate stakeholder awareness, and identify specific gaps related to the sustainable use of forest biomass. To achieve this, a structured survey was conducted across the BRS, targeting a diverse group of stakeholders involved in education, industry, policy, and civil society. The collected data provided both quantitative and qualitative insights, forming the empirical foundation for defining strategic educational priorities and designing targeted learning interventions.

The sampling strategy combined purposive quota sampling with targeted recruitment across five stakeholder groups (students, water entrepreneurs, cosmetics entrepreneurs, food sector workers, and consumers) and five Baltic Sea Region countries (Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Finland, and Sweden). This non-probability approach was selected because specialised target populations lack comprehensive sampling frames, rendering probability sampling impractical. Quota targets were set at 40 respondents per stakeholder group in each country (total n = 1000), with demographic diversity criteria aligned with the available census-based distributions. Recruitment was conducted through two parallel channels: (1) institutional partners disseminated survey invitations via email lists, newsletters, and professional forums, and (2) a market research agency implemented targeted advertising and pre-screened panel recruitment to fill the remaining quotas. Overall, 4273 invitations were issued, yielding 1000 completed questionnaires and an overall response rate of 23.4%, following the AAPOR RR3 standards.

To ensure cross-country comparability, identical quota structures were applied in all five countries, and the research agency implemented post-stratification demographic weighting at the country-level. The CAWI questionnaire was distributed in June 2025 and administered exclusively in English to maintain consistency across the national samples.

The study employed the Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI) technique, in which respondents received a personalised survey link and completed the questionnaire independently online. The survey platform automatically monitored the logical correctness of the responses by preventing contradictory selections, applying programmed routing via filter questions, and blocking the final submission until all required items were completed. This ensured high data quality and reduced the risk of missing or inconsistent answers.

The questionnaire was designed based on existing circular economy capacity models and established educational frameworks. It included a mix of closed-ended, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale items, enabling a systematic assessment of educational needs, perceived barriers, and stakeholder attitudes. This structured, theory-informed design supports robust cross-national comparisons while acknowledging the inherent limitations of quota-based, non-probability sampling for broader generalisability. To ensure validity and reliability, the survey data were complemented by follow-up consultations with selected stakeholders. These discussions allowed for verification of survey findings, refinement of priorities, and exploration of context-specific nuances. Quantitative analysis was conducted using descriptive statistics to identify patterns and trends, while qualitative responses were reviewed thematically to capture deeper insights. This mixed-methods approach ensured a comprehensive understanding of the educational landscape and enhanced the robustness of the findings. Despite common limitations of online surveys, such as potential self-selection bias, the dataset offered sufficient breadth and diversity to inform the subsequent design of the educational roadmap.

2.2.3. Description of the Research Sample

The survey encompassed a broad spectrum of stakeholders to guarantee comprehensive representation. Students and educators contributed perspectives on formal educational programmes, while industry professionals highlighted practical training needs and market-driven requirements. Policymakers and public administrators provided insights into regulatory and governance dimensions of education. Non-governmental organisations and civil society actors emphasized the importance of inclusivity and awareness-raising. This diversity of perspectives ensured that the data reflected a wide range of expectations, challenges, and opportunities, forming the basis for developing a roadmap that balances academic rigor, practical relevance, and societal impact.

The study was conducted in five BSR countries: PL, LT, LV, FI, and SE (Table 2). The analysis covered five main stakeholder sectors (Table 2): 1—school-academic youth (18–24 years old), 2—represented by students of cosmetology, catering, food technology, biotechnology, environmental engineering, or related fields; water and sewer entrepreneurs; 3—cosmetics entrepreneurs; 4—entrepreneurs in the restaurant sector, food processing, or food service workers; as well as 5—consumers and customers, understood as members of the general public who potentially use products such as cosmetics or restaurant services. Each of these five stakeholder sectors was represented equally in all participating countries, with 40 respondents per sector per country, which ensured comparability of the results across different national contexts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic distribution of respondents.

The majority of respondents were students in fields such as cosmetology, gastronomy, food technology, biotechnology, and environmental engineering, comprising 21–47% of the total sample, depending on the country. A significant portion of the respondents were owners and employees of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (30–47%) and personnel from large enterprises (29–41%). In contrast, representatives from non-governmental organisations (3–6%), public administration (1–5%), and academia (3–6%) formed smaller groups. Respondents spanned all age categories, with the largest proportions among individuals aged 26–35 (21–41%) and 36–50 years (25–39%). The youngest cohort (18–25 years) constituted 25–33% of the participants, while those over 50 years represented 8–16%. In PLPL, younger respondents were predominant (61% under 35), whereas in FI and SE, older age groups were more prominently represented. The gender distribution was balanced, with women comprising between 43% (LV) and 58% (LT), and men accounting for 42–57%. Cross-country differences in the gender structure were minor and exhibited no consistent patterns. The educational profile of respondents indicated a generally high level of attainment: master’s degrees were most prevalent (35–49%), followed by bachelor’s or engineering degrees (32–48%), while 10–21% held doctoral or postgraduate qualifications. Secondary education accounted for 19–50% of the responses, and primary education was marginal (0–1%).

Distinct differences in the sample compositions were observed across countries. In PL, the sample was mainly composed of students (35%) and employees of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (30%), reflecting a younger demographic. In LT, SME representatives formed the largest group (47%), accompanied by a relatively high proportion of highly educated respondents. In LV, students (36%) and employees of large enterprises (36%) were the most prevalent, with women comprising the majority (58%). In FI, employees of large enterprises were most common (41%), with the 26–35 age group being the largest (39%) and nearly equal gender distribution. In SE, employees of large enterprises (47%) and students (20%) were the most prominent groups, with individuals aged 26–35 years forming the largest cohort (32%).

Overall, the research sample exhibited considerable diversity in terms of occupational role, age, gender, and educational background. Despite this heterogeneity, distinct country-specific trends were evident: in PL, LT, and LV, students constituted a relatively larger proportion of respondents, whereas in FI and SE, employees of large enterprises predominated. This diverse yet structured composition provides a robust foundation for analyzing stakeholder attitudes and perceptions across the countries studied.

2.2.4. Development Process of Education Roadmap

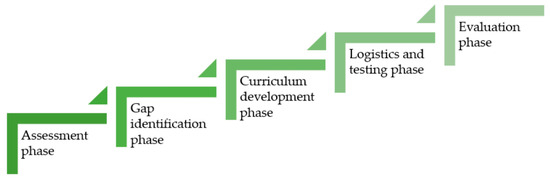

The development of the Education Roadmap followed a structured and data-driven methodology aimed at identifying educational priorities, gaps, and tools necessary for enhancing CE knowledge transfer within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. This approach combines elements of desk research, conceptual modelling, and empirical analysis, integrating quantitative results from stakeholder surveys with qualitative assessments derived from expert opinions and existing educational materials. Desk research provides a theoretical and contextual basis by systematically reviewing the scientific literature, educational programmes, and institutional resources related to CE education in the forestry sector. The primary goal was to create a roadmap that aligns educational content with sectoral needs, ensuring effective dissemination of CE principles across formal and informal learning environments (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phases of the Education Roadmap development process illustrating the sequential stages from assessment to evaluation within the CE education framework.

The methodology is based on a five-phase framework encompassing assessment, gap identification, curriculum development, pilot implementation, and evaluation. In the assessment phase, existing educational programmes, online courses, policy documents, and stakeholder survey responses were analysed to map the current landscape of CE-related education [43,44]. This step provides insights into the accessibility, content scope, and perceived effectiveness of available educational resources. The gap identification phase focuses on determining the missing or underrepresented areas within the current educational offer. Respondents’ feedback on barriers, such as limited access to experts, low public awareness, and a lack of structured materials, translated into measurable knowledge gaps within both formal and informal education systems. The curriculum development phase involved the formulation of a structured Education Roadmap, defining thematic priorities (e.g., recycling technologies, CE policy, and sustainable resource management), and aligning them with target groups (students, entrepreneurs, policymakers, and NGOs). For each priority area, the roadmap specified the most suitable educational formats, including (MOOCs), webinars, mobile applications, and case-based learning modules. This approach ensured the integration of economic, environmental, and social perspectives into the educational framework. Pilot educational initiatives were designed and implemented during the logistics and testing phases to test the feasibility and reception of the proposed learning tools. These pilot studies were conducted among selected stakeholder groups, enabling the assessment of content clarity, user engagement, and applicability in professional contexts. Finally, the evaluation phase focused on the development of feedback instruments, such as pre- and post-training questionnaires, to measure the effectiveness of pilot campaigns. The analysis covered knowledge acquisition, attitudinal change towards CE principles, and the persistence of barriers identified earlier. The findings were then used to refine the roadmap through a continuous improvement process, ensuring periodic updates (every 2 to 3 years) in response to emerging educational and technological trends.

Following this methodological process, a conceptual framework for the Education Roadmap was developed, based on the theoretical foundations of CE education and sustainability learning. The framework is illustrated as a schematic diagram in which individual components, representing the main educational blocks, are interconnected through directional linkages that illustrate the hypothesized relationships between them. Each block corresponds to a specific stage of the educational process, encompassing assessment, gap identification, curriculum development, pilot implementation, and evaluation.

The conceptual model assumes a dynamic and adaptive structure, allowing flexibility in application, depending on regional priorities, stakeholder groups, and available resources. This implies that certain elements may be expanded, omitted, or integrated differently in specific national or institutional contexts. Rather than exhaustively representing all possible educational interactions, the framework serves as a guiding structure that visualizes how formal, non-formal, and informal education systems can cooperate to strengthen CE knowledge and competencies within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. The resulting Education Roadmap provides a strategic and adaptive framework for guiding CE education development, fostering a transition towards a more circular and knowledge-based forestry bioeconomy in the BRS.

2.3. Stakeholder Segmentation Analysis

To enhance the comprehension of stakeholder diversity and ensure that the Education Framework is better aligned with specific user needs, a segmentation analysis was conducted using the survey dataset. The analysis included responses from five BRS countries—FI, SE LV, LT and PL-encompassing five principal stakeholder groups: (1) students and young academics (18–24 years); (2) entrepreneurs from the water and wastewater sector; (3) entrepreneurs from the cosmetics industry; (4) representatives of the food processing and gastronomy sector; and (5) consumers as potential end-users of bio-based products. The aggregated data were standardized using the z-score method (mean = 0, SD = 1) to ensure comparability across variables and countries. Stakeholder segmentation was subsequently performed using the K-means clustering algorithm (K = 3) implemented in Origin(Pro) (OriginLab, version 2025b). The number of clusters was determined based on theoretical assumptions reflecting three dominant engagement dimensions (Academic, Practical, and Decision) and verified through visual inspection of centroid distances [45]. This segmentation procedure provided a structured analytical foundation for distinguishing stakeholder profiles and tailoring the Education Framework to the specific characteristics and needs of different groups across the BRS.

3. Results

3.1. Educational Content Review

The review of educational content provided a comprehensive overview of existing CE learning initiatives within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. The analysis was conducted through a systematic desk study of academic, institutional, and open-access sources, encompassing both formal and informal education formats. Identified resources included university programmes, professional training courses, and digital learning materials. These were categorized according to their format, thematic focus, and target audience to enable comparative evaluation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Overview of existing educational programmes and initiatives related to CE in the forestry sector of the BRS.

The thematic assessment was conducted within the comprehensive regulatory and policy framework established by the European Union to facilitate the transition to a CE and bio-based sectors. At the EU level, three key strategic documents shape the educational and institutional contexts of forestry and bioeconomy learning. The Circular Economy Action Plan [46], under the European Green Deal, defines overarching priorities for resource circularity, product design, and sustainable value chains, encouraging the inclusion of CE principles in professional and environmental education. Complementarily, the European Bioeconomy Strategy [47] promotes the sustainable use of biological resources and emphasises the role of education, training, and research in advancing a circular and innovation-driven bioeconomy. Regionally, the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region-Policy Area Bioeconomy (PA Bioeconomy) provides a collaborative framework for integrating these principles across forestry, agriculture, and fisheries, thereby supporting joint educational projects and knowledge—sharing initiatives among Baltic countries [48].

In light of this policy context, the thematic assessment identified that the majority of existing educational materials in the BRS predominantly address broad themes such as sustainability, waste management, and renewable energy. However, there is a notable scarcity of content explicitly focused on the circular bioeconomy and forestry. Resources dedicated to forest biomass utilisation, bio-based value chains, or circular innovation within the forestry sector are relatively limited, suggesting that the integration of sector-specific knowledge into CE education remains insufficient. Furthermore, case-based learning and practical applications, which are essential for cultivating operational competencies, were found to be underrepresented across the reviewed programmes [50].

Geographically, the most advanced frameworks for CE education are found in Nordic and Western European countries, where universities and innovation networks have developed structured curricula and research-based learning modules [22,23,24,25]. Conversely, educational programmes in Central and Eastern Europe, including the LT, LV and PL, predominantly focus on traditional forest management and resource efficiency. Instances that explicitly incorporate circular bioeconomy principles or the value-added utilisation of forest residues are relatively uncommon, and locally available educational resources—especially those in national languages—are limited [26,27,28,53].

The analysis of target audiences revealed a pronounced emphasis on higher education institutions and university students, with relatively fewer training opportunities specifically designed for industry professionals, policymakers, and the general public. Although several nonformal and lifelong learning initiatives have been identified, they generally lack systematic alignment with formal educational pathways, resulting in a fragmented landscape of CE-related learning opportunities [51,54].

From a methodological perspective, the comparative review identified significant heterogeneity in the integration of CE competencies across various programmes. Conceptual elements, such as sustainability principles, resource circularity, and environmental ethics, are frequently incorporated [48]. However, applied components, including life cycle assessment (LCA), bio-based business models, and digital management tools for forest resources, have been inconsistently integrated [23,24,48]. Interdisciplinary connections between environmental, technological, and socio-economic dimensions are often partial or implicit, rather than explicitly structured within curricula.

The findings suggest that education related to the CE within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors across the BRS is characterised by fragmentation and uneven development across countries and educational levels. Although existing initiatives, particularly those originating from Nordic countries, offer a valuable foundation, significant gaps remain in the practical application of CE principles and the availability of materials tailored to various stakeholder groups. Addressing these deficiencies is crucial for aligning forestry education with the strategic objectives of the CE and enhancing the sector’s contribution to sustainable regional development [49].

Existing roadmap studies in environmental and forestry-related education serve as valuable reference for this study. Research in environmental economic education underscores the necessity of integrating ecological and economic knowledge, highlighting the competencies that promote sustainability and circularity [55]. Studies published in Forest Policy and Economics demonstrate that educational and policy roadmaps in the forestry sector are instrumental in identifying priority skills and adapting learning strategies to address emerging environmental and market challenges through multi-stakeholder engagement and flexible training formats [56]. Furthermore, analyses available on the Dialnet platform emphasise the significance of combining formal and non-formal education to develop effective and inclusive roadmaps that align with evolving environmental policies [57].

Unlike other approaches, our proposed Education Roadmap stands out by concentrating on the forest bioeconomy of the Baltic Sea Region. It uniquely integrates three educational domains-formal, non-formal, and informal-and is grounded in empirical stakeholder segmentation across five countries. This results in a regionally adapted, multi-actor framework that more comprehensively advances circular economy principles within the forestry sector than existing roadmaps.

3.2. Educational Opportunities in Forest Management and Biomass Processing

3.2.1. Perceptions of Educational Opportunities in Forestry and Bioeconomy Sectors

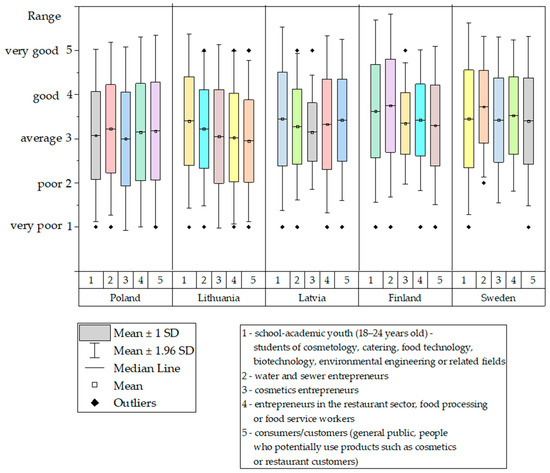

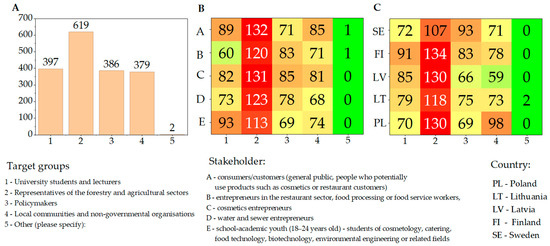

The analysis of survey responses provides insights into how different stakeholder groups across the BRS perceive current educational opportunities related to the circular bioeconomy and forestry. The comparative results revealed clear cross-country and inter-stakeholder differences in the assessment of existing learning frameworks and training accessibility (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Evaluation of current educational opportunities in forest management and biomass processing, categorized by country and stakeholder group.

Polish respondents provided the most critical evaluations, with median scores around “average” (3) and wide dispersion, indicating considerable variation. Participants from FI and SE expressed more favorable opinions, with medians approaching “good” (4) and fewer negative outliers. LT and LV showed intermediate ratings from average to good, with narrower variability than PL. Among stakeholder categories, academic youth (Group 1) assessed opportunities as average, though more positively in Nordic countries. Entrepreneurs from water and sewage (Group 2) and food and gastronomy (Group 4) provided the lowest evaluations, between poor and average, suggesting misalignment with sectoral needs. Cosmetics entrepreneurs (Group 3) reported higher satisfaction, particularly in LT and FI, where median scores reached “good.” Consumers (Group 5) were the most optimistic, assessing opportunities as average or good. The results show that perceptions vary across geographical and professional dimensions. Nordic countries and consumer groups viewed educational offerings more favourably, while Polish stakeholders and sector-specific entrepreneurs expressed greater dissatisfaction, indicating gaps in relevant learning resources.

The disparities in access to formal CE education among the Baltic Sea Region countries arise from a combination of institutional, economic and infrastructural factors. Nations with higher levels of economic development typically possess more advanced recycling and innovation infrastructure, which facilitates the incorporation of CE principles into formal curricula. The coherence of national and regional policies supporting CE education is crucial for enabling institutions to effectively adopt and update training programs. Additionally, public awareness and demand for circular bioeconomy skills further influence educational offerings. In contrast, countries with less developed infrastructure and limited institutional support face challenges in expanding access to CE education, leading to regional imbalances that require targeted policy and financial interventions to bridge these gaps.

3.2.2. Reported Barriers to Acquiring Knowledge About Innovative Uses of Forest Biomass

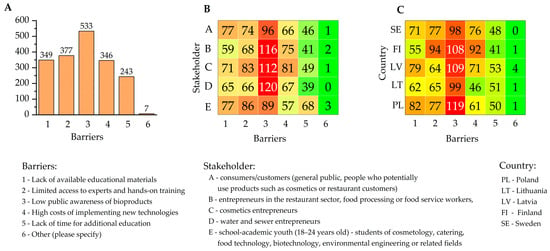

Understanding the barriers hindering knowledge acquisition is essential for designing effective educational interventions. The following analysis summarises the main constraints identified by survey respondents across the BRS, highlighting both general patterns and country—or stakeholder-specific differences (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reported barriers to acquiring knowledge about innovative uses of forest biomass: (A) overall distribution, (B) country-level comparison, (C) stakeholder group comparison.

Figure 5A shows the distribution of barriers identified by respondents. The most significant obstacle was low public awareness of bioproducts (Barrier 3), reported by over 500 participants. This indicates that education challenges extend beyond lack of teaching materials, reflecting a broader systemic issue: insufficient societal understanding limits demand for educational content and motivation to develop it. Common barriers included limited access to experts and practical training (Barrier 2) and lack of educational materials (Barrier 1), indicating educational infrastructure weaknesses. High implementation costs (Barrier 4) and lack of time for learning (Barrier 5) were reported less frequently, suggesting main challenges relate to knowledge accessibility rather than financial or time constraints. Few open-ended responses (Barrier 6) confirmed the predefined categories captured key challenges.

Figure 5B shows variations among stakeholder groups. Entrepreneurs from water and sewage (Group D) and food service sectors (Group B) reported strongest barriers, particularly regarding public awareness (Barrier 3) and expert access (Barrier 2). This shows sectors requiring technological innovation face greater challenges accessing specialized knowledge. Cosmetics entrepreneurs (Group C) and academic youth (Group E) emphasized lack of educational materials and high costs (Barriers 1 and 4), indicating misalignment between available training and their needs. Consumers (Group A) reported barriers more evenly, showing general awareness but less sector-specific expertise. Results indicate critical barriers affect stakeholders engaged in technological innovation, while consumers and students express broader perspectives.

Figure 5C compares responses across countries. PL and LV showed highest perceived barriers, with limited expert access and low public awareness being prominent, reflecting gaps in bioeconomy education and support. LT and SE showed similar but less intense trends. FI, with advanced forestry education systems, noted awareness and cost barriers, while time constraints were least reported. Nordic countries demonstrated moderate barrier profiles, whereas PL and Baltic states faced more pronounced structural limitations in bioeconomy education and knowledge transfer.

3.2.3. Priority Topics for Education on Sustainable Forest Biomass Use

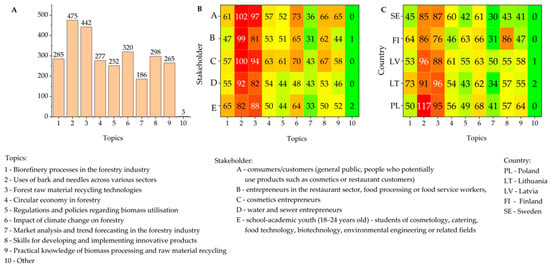

To guide the design of future educational programmes, respondents were asked to indicate the topics that should be prioritized in curricula related to the sustainable use of forest biomass. The results showed distinct trends across the BRS, highlighting both shared and country-specific priorities (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Priority topics for education on sustainable forest biomass use according to survey respondents (A) overall distribution, (B) stakeholder group comparison, (C) country-level comparison.

The distribution (Figure 6A) shows that highest-ranked topics include bark and needles use across sectors (2), forest raw material recycling technologies (3), and biorefinery processes (1). These preferences reflect emphasis on applied and technological dimensions of the circular bioeconomy, highlighting the need for practice-oriented, innovation-driven education. Topics like CE in forestry (4), regulations on biomass utilisation (5), and skills for implementing innovative products (8) received considerable attention, underscoring the importance of regulatory awareness and innovation capacity. Market analysis (7) and climate change impacts on forestry (6) were rated lower, suggesting these areas may be adequately addressed or less relevant to current needs.

Comparing stakeholder groups (Figure 6B), academic youth (E) and cosmetics entrepreneurs (C) showed strong interest in technological and innovation-oriented topics (1–3, 8), reflecting their engagement with applied sciences and product development. Entrepreneurs in restaurant and water management sectors (B, D) showed balanced priorities but assigned lower importance to policy concerns. Consumers (A) emphasized areas associated with bio-based applications and recycling technologies, indicating product-oriented understanding of circularity.

At country level (Figure 6C), PL and LV prioritized biorefinery and recycling topics (1–3), showing interest in practical technological solutions. FI and SE emphasized climate change adaptation and innovation skills (6, 8), reflecting advanced integration of CE principles in forestry education. LT presented a balanced profile, combining technological development with regulatory issues. The findings show that educational priorities in the BRS focus on technological innovation, resource recovery, and biorefinery processes, while policy frameworks and market analysis remain secondary. These results highlight the need to strengthen applied bioeconomy competencies and foster collaboration among education, research, and industry stakeholders to advance sustainable forest biomass utilisation.

3.2.4. Actions Supporting Knowledge Transfer in Forest Management

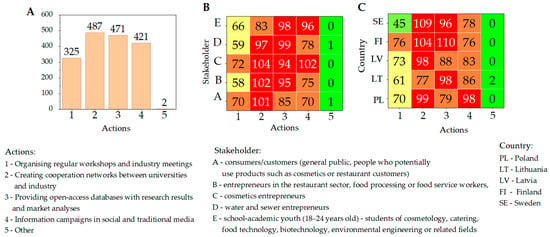

To identify the most effective approaches for strengthening knowledge exchange in the forestry sector, respondents were asked to prioritize actions facilitating collaboration, accessibility, and innovation in education (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Actions supporting knowledge transfer in forest management (A) overall distribution, (B) stakeholder group comparison, (C) country-level comparison.

The results (Figure 7A) revealed an emphasis on networking and cooperation measures, with the most selected actions being collaborative networks between universities and industries (2) and open-access databases containing research results and market analyses (3). This was followed by information campaigns through social and traditional media (4), regular workshops, and industry meetings (1). These categories indicate a strong demand for interactive and accessible mechanisms to enhance knowledge transfer in sustainable forestry and the circular bioeconomy sector. The “Other” responses (5) confirmed the adequacy of the proposed actions in the questionnaire.

The stakeholder comparison (Figure 7B) shows a consistent preference for institutional cooperation and data-sharing initiatives (2–3) across respondent groups. Cosmetics entrepreneurs (C) and academic youth (E) emphasized digital databases and media communication, reflecting a preference for online resources. Entrepreneurs in the water management (D) and restaurant (B) sectors highlighted networking and partnerships with educational institutions, showing the need for direct knowledge exchange channels. Consumers (A) expressed a balanced perspective, recognizing collaborative dissemination models while maintaining an awareness of communication strategies.

At the country level (Figure 7C), FI and SE showed the strongest support for cooperative networks and open-access platforms, corresponding to their developed innovation ecosystems and digital knowledge-sharing cultures. PL and LT prioritized information campaigns and workshops, suggesting a greater reliance on traditional outreach. LV presented a balanced response profile with a preference for database-based knowledge dissemination. The findings indicate that stakeholders across the BRS favor collaborative, transparent, and technology-supported approaches to knowledge transfer in forest management. These insights emphasize the importance of strengthening partnerships, broadening access to research outputs, and improving communication between academia, industry, and society to integrate CE principles into forestry education and practice.

3.2.5. Preferred Formats of Educational Materials on Sustainable Forest Biomass Use Among Different Stakeholder Groups Across the BRS Countries

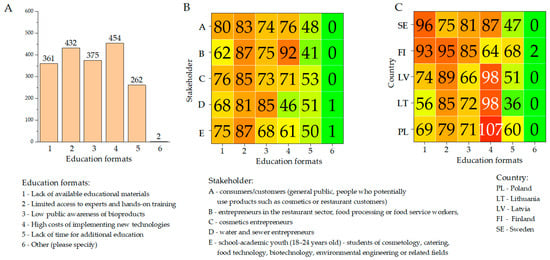

To better understand how knowledge transfer can be effectively tailored to different audiences, the survey explored stakeholder preferences regarding educational formats related to sustainable forest biomass use (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Preferred formats of educational materials on sustainable forest biomass use among different stakeholder groups across the BRS countries: (A) overall distribution, (B) stakeholder-group comparison, and (C) country-level comparison.

The results (Figure 8A) show that interactive workshops and webinars (2) and online learning formats (1) were the most selected options across countries. These preferences indicate a shift towards flexible, digital, and participatory learning environments that promote interaction and knowledge exchange among students. Traditional printed materials and self-study formats (3) ranked lower, suggesting that stakeholders increasingly value dynamic, collaborative, and technology-enhanced approaches.

Notable differences were observed among the stakeholder groups (Figure 8B). Academic youth (E) and consumers (A) preferred digital learning tools, highlighting the importance of accessibility and online engagement in the learning process. Entrepreneurs in the restaurant (B) and cosmetics (C) sectors favored interactive workshops and case-based training, reflecting their need for applied learning that connects education with business innovation. Entrepreneurs from the water and sewage sector (D) showed lower engagement with online tools, suggesting a preference for structured, technical, or in-person formats.

At the country level (Figure 8C), FI and SE showed a strong inclination towards digital and hybrid learning modes, reflecting their advanced e-learning infrastructure and awareness of circular bioeconomy principles. PL and LT exhibited balanced preferences, maintaining an interest in traditional materials and face-to-face workshops, indicating a transition between conventional and digital learning. Latvian respondents prioritized interactive and practice-based activities, emphasizing experiential learning. The findings show increasing diversification and digitalization of educational preferences across the BRS. Stakeholders favor interactive, collaborative, and technology-supported formats, highlighting the need for a multi-format framework that balances digital accessibility with practical opportunities tailored to the forestry and bioeconomy sectors.

3.2.6. Identification of Key Target Groups for Education on Sustainable Forest Biomass Use

Identifying key target groups for education on the sustainable use of forest biomass is essential for aligning learning initiatives with real sectoral needs. Understanding which actors should be most actively engaged allows for a more efficient allocation of resources and ensures that educational efforts directly support the implementation of CE principles in forestry. The survey results highlight clear preferences among respondents, revealing both cross-country and inter-stakeholder differences in the perceived importance of specific groups (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Target groups to be most involved in education on sustainable forest biomass use management (A) overall distribution, (B) stakeholder group comparison, (C) country-level comparison.

Figure 9A shows the distribution of responses regarding the target groups for education on sustainable forest biomass use. Respondents identified forestry and agricultural sector representatives (Group 2) as key actors, given their direct connection to biomass production and CE) implementation in the state. University students and lecturers (Group 1) were the second most selected category, highlighting academia’s role in embedding sustainability into formal education. Policymakers (Group 3) and local communities or NGOs (Group 4) were also recognized as important participants, although less frequently, for their supportive and awareness-raising functions. The minimal selection of “Other” indicates agreement on these four main target groups. Figure 9B compares the stakeholder perspectives. All groups agreed that forestry and agricultural practitioners should lead such educational initiatives. Cosmetics and food sector entrepreneurs (Groups B and C) emphasized practitioners and students (Groups 1 and 2) as key drivers of innovation and knowledge transfer. Academic youth (Group E) and consumers (Group A) prioritized policymakers and NGOs (Groups 3 and 4), reflecting expectations for institutional support and public communication on sustainable biomass management. Figure 9C shows the response distribution across countries. FI and LV strongly supported professional and academic involvement (Groups 1 and 2), reflecting their established forestry education systems and CE integration in education. PL and LT favored local community and NGO participation (Group 4), indicating recognition of the social dimension of sustainability education. SE showed balanced responses across the target groups, consistent with its inclusive environmental learning approach. The results demonstrate a shared understanding that effective education on sustainable forest biomass use should combine professional expertise, academic engagement, and community participation. Cross-sectoral collaboration among forestry practitioners, universities, policymakers, and local organisations is essential for developing comprehensive CE-oriented education programmes.

3.3. Cluster Analysis and Implication for the CE Educational Strategy

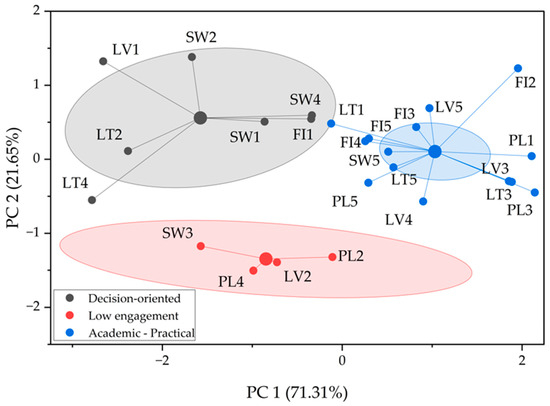

The stakeholder survey conducted across five BRS countries-PL, LT, LV, SE, and FI-targeted five main stakeholder groups: (1) students and young academics (18–24 years), (2) entrepreneurs in the water and wastewater sector, (3) entrepreneurs in the cosmetics industry, (4) representatives from the food processing and gastronomy sector, and (5) consumers as potential end-users of bio-based products. The data were standardized using the z-score method to ensure comparability across variables and countries. Subsequently, K-means clustering analysis (K = 3) was performed using OriginPro (OriginLab, version 2025b). The number of clusters was determined based on theoretical assumptions reflecting three engagement dimensions-Academic, Practical, and Decision-and verified through visual inspection of centroid distances. This segmentation identified three distinct clusters of stakeholders, each varying in their level and type of engagement with circular bioeconomy and forestry education.

As summarized in Table 4, the cluster centroids indicate clear differentiation between stakeholder profiles across the three engagement dimensions.

Table 4.

Cluster centroids across engagement dimensions.

Cluster 1 (Decision-oriented, marked in grey) consisted of stakeholders with high decision-making activity but lower academic and practical involvement, mainly representing public administration bodies, regulatory institutions, and water-sector enterprises. Cluster 2 (Low engagement, marked in red) comprised a smaller number of respondents from PL, LV, and SE, mostly consumers and small entrepreneurs, who exhibited limited participation in innovation and science-business cooperation. Cluster 3 (Academic-Practical, marked in blue) included the majority of respondents from FI, LT, LV, PL, and SE. This group showed high academic and practical engagement, indicating strong connections between science, innovation, and real-world applications.

To statistically verify differences between the three stakeholder clusters, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for each engagement dimension (Academic, Decision, Practical). ANOVA tests whether the mean values of a variable differ significantly across multiple groups, taking into account both between-group and within-group variability. The results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

ANOVA results for differences between clusters.

Cluster analysis revealed three distinct stakeholder profiles across the five BSR countries: Cluster 1—Decision-oriented: This group, primarily composed of institutional actors, policymakers, and regulatory stakeholders, showed high engagement in decision-making but lower involvement in academic and practical activities. Their strategic role positions them as key facilitators in implementing circular economy (CE) education and policy initiatives. Cluster 2—Low engagement: Mainly consisting of consumers and small enterprises, this cluster exhibits limited involvement in academic, practical, and decision-making dimensions. This underscores the need for awareness-raising and basic educational interventions to foster understanding and adoption of CE principles. Cluster 3—Academic-Practical: The largest and most balanced cluster, it integrates strong academic, practical, and decision-making engagement. Stakeholders in this group demonstrate a high interest in applied, innovation-oriented education that links research, industry, and real-world CE applications. One-way ANOVA confirmed that the differences between clusters were statistically significant across all engagement dimensions (Academic, Decision, Practical; p < 0.0001). This indicates that the identified clusters are theoretically distinct and empirically robust. The Academic-Practical cluster dominates most countries, suggesting the widespread potential for targeted educational strategies focused on innovation and applied learning. Meanwhile, the presence of Decision-oriented and Low-engagement clusters highlights the need for differentiated CE educational approaches tailored to stakeholder roles, influence, and engagement levels. Overall, these findings support a tiered CE educational strategy, combining advanced, innovation-driven training for highly engaged stakeholders with foundational awareness-raising for less engaged groups, and leveraging policymakers’ influence to foster the systemic adoption of circular bioeconomy principles.

The structure presented in Table 6 shows that the Academic-Practical cluster (Cluster 3) dominates across most countries, suggesting a generally high level of interest in applied, innovation-oriented education. The Decision-oriented cluster (Cluster 1), more prominent in LT, FI, and SE, represents institutional actors and policymakers with strategic potential for CE implementation. In contrast, the Low-engagement cluster (Cluster 2)-mainly composed of consumers and small enterprises—highlights areas where awareness-raising and basic educational activities are most needed.

Table 6.

Distribution of stakeholder groups (1–5) and countries across K-means clusters.

A two-dimensional projection of the K-means results is shown in Figure 10. Each point represents a stakeholder group from a specific country, positioned along two principal components derived from the normalized dataset. The first component (PC1) primarily corresponds to the academic-practical dimension, while the second (PC2) reflects the decision-making dimension. Together, these components explain 92.96% of the total variance, confirming the robustness of the segmentation model. Three clearly separated clusters are observable: the Decision-oriented cluster (gray), located in the upper part of the plot, represents actors with high institutional and managerial roles; the low engagement cluster (red) occupies the lower part, illustrating limited innovation participation; and the Academic-Practical cluster (blue) appears on the right side, representing groups strongly linked to education, applied research, and cross-sectoral innovation. The ellipses represent the 95% confidence regions around the cluster centroids, visualizing within-group variations. The distribution of points confirms the internal consistency of the identified segments and their alignment with theoretical assumptions.

Figure 10.

Stakeholder segmentation map (K-means clustering) showing three groups of respondents according to their engagement dimensions: Decision-oriented (grey), Low engagement (red), and Academic-Practical (blue).

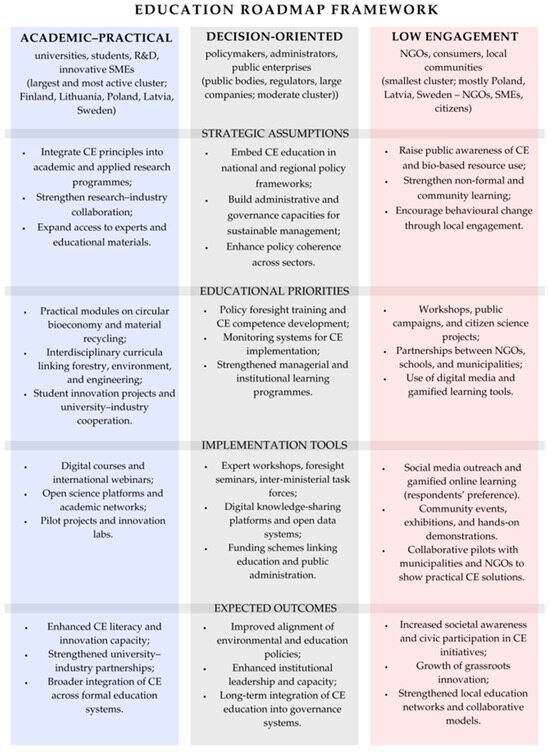

3.4. Conceptual Framework for the Education Roadmap

The Education Roadmap model (Figure 11) was developed to integrate insights from a stakeholder survey, K-means clustering analysis, and a review of educational content related to the CE within the forestry and bioeconomy sectors of the BSR. This model serves as a framework for developing competencies, promoting cooperation, and facilitating knowledge exchange among three stakeholder groups: academic-practical, decision-oriented, and low-engagement. An analysis of policy documents and educational strategies shows that CE education development in forestry is embedded in the European Union’s regulatory framework. Three strategic documents significantly influence this: the Circular Economy Action Plan (2020) [46], which, under the European Green Deal, emphasises integrating circular principles into environmental and vocational education; the EU Bioeconomy Strategy [47], which supports the sustainable use of biological resources and the development of skills for innovation and circularity; and the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region-Policy Area Bioeconomy [48], which offers a collaborative platform for educational cooperation across the region.

Figure 11.

Conceptual framework for the Education Roadmap integrating insights from desk research and empirical analysis. The model is represented as a tree structure with three branches: academic-practical, decision—oriented and low engagement. Each containing four layers: strategic assumptions, educational priorities, implementation tools and expected outcomes. The branches converge into a shared Education Roadmap framework and a circular knowledge loop ensuring feedback and continuous improvement.

A thorough review of current educational initiatives has highlighted significant geographical and thematic disparities in forestry education concerning the CE. Sixteen national and regional initiatives were identified, spanning both formal and non-formal educational formats. These include university-level programmes, such as those offered by the University of Helsinki, the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, and the University of Agriculture in Krakow, as well as open-access learning platforms like the FAO e-learning Academy and EIT Climate-KIC. The most advanced educational frameworks are found in Nordic countries, where CE principles are systematically integrated into academic curricula and industry-focused learning processes. In contrast, Central and Eastern European countries, including LT, LV, and PL, primarily focus on traditional forest management and resource efficiency, with limited incorporation of circular bioeconomy content in their FMPs.

Within BSR, there is a discernible deficiency in educational resources available in national languages, coupled with limited access to experts and a lack of systemic integration between formal and informal education. Higher education institutions and university students continue to be the primary focus, whereas training opportunities for policymakers, industry representatives and the general public remain limited. These observations highlight the need for a comprehensive and inclusive framework that addresses the diverse educational needs of various stakeholder groups.

In the academic-practical dimension, respondents prioritized topics such as biorefinery processes, forest resource recycling, and the use of by-products such as bark and needles. Preferred learning formats included MOOCs, webinars, and open-access knowledge platforms. These align with literature trends emphasizing digital learning and university-industry cooperation in developing circular competencies. Priorities include the creation of interdisciplinary modules, student innovation projects, and expansion of digital resources and expert networks.

In contrast, the decision-oriented cluster placed greater emphasis on regulatory, governance, and policy aspects of CE implementation. Respondents from this group highlighted the importance of biomass regulation, cross-sectoral policy coordination, and monitoring mechanisms for CE education. Their training needs focus on foresight seminars, policy workshops, and expert exchange sessions that help translate academic knowledge into practical governance tools. Such initiatives can enhance institutional leadership, policy coherence, and long-term sustainability of educational reforms.

The low-engagement cluster, mainly comprising small enterprises, communities, and NGOs, revealed significant educational gaps. Key barriers include low public awareness, limited access to materials and expertise, and a lack of training time. Therefore, non-formal and community education should be prioritized through information campaigns, workshops, and initiatives that link schools, municipalities, and NGOs. These measures can foster acceptance and innovation, supporting behavioural changes towards circular forestry practices.

The proposed Education Roadmap is designed as a dynamic and adaptable framework that prioritises inclusive, multi-stakeholder engagement in the education of children with disabilities. Key participants include academic institutions, industry partners, policymakers, NGOs, and local communities, who collaboratively design pilot educational initiatives that can be progressively scaled based on feedback and their demonstrated effectiveness. Implementation is expected to occur through iterative cycles that combine capacity building, resource sharing, and policy integration to address governance fragmentation and resource scarcity issues. Feedback mechanisms are embedded to ensure continuous refinement, and policy alignment guarantees the sustainability of interventions. The roadmap underscores the need for flexible and modular learning pathways that can be adapted to country-specific contexts within the BSR.

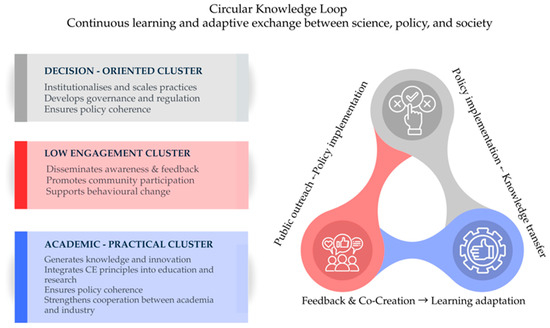

The Education Roadmap model integrates three stakeholder perspectives within a Circular Knowledge Loop (Figure 12), promoting continuous learning, adaptation, and reciprocal feedback. In this loop, the academic-practical group is responsible for generating knowledge and innovation, decision-oriented institutions are tasked with formalizing and scaling best practices, and the low-engagement group disseminates awareness and provides societal feedback. This cyclical mechanism establishes an adaptive, multi-level learning system that strengthens the connections between research, policy, and public engagement.

Figure 12.

Conceptual model of the circular knowledge loop illustrating the interaction between academic-practical (blue), decision-oriented (grey), and low engagement (red) clusters within the Education Roadmap framework.

By combining literature review findings with empirical data, the model provides a comprehensive framework for CE education in the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. It reflects regional asymmetries in educational development while offering tools for capacity building and knowledge alignment across countries. Through the Circular Knowledge Loop, knowledge generated in academic environments is transformed into policy frameworks and community practices, and subsequently reintegrated into educational systems as feedback for continuous improvement.

Ultimately, the Education Roadmap represents a coherent, empirically grounded, and policy-aligned framework for advancing CE education in forestry and bioeconomy sectors across the BRS. Its implementation can enhance human capital development, foster innovation, and strengthen environmental awareness, contributing to a sustainable transition towards a circular and low-carbon bioeconomy.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore a persistent gap between the strategic goals of the CE transition and the educational frameworks currently supporting its implementation in the forestry and bioeconomy sectors of the BSR. Both the literature review and empirical data indicate that existing educational activities, whether formal or informal, are fragmented and primarily focused on general or cross-sectoral CE topics, such as waste management, recycling, or renewable energy use. While these areas are undeniably relevant to circularity, they are not adequately tailored to the specific context, processes, and challenges of the forestry sector in which they operate [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,44]. Consequently, educational offerings in the BSR often lack forestry-oriented content, particularly regarding forest-based value chains, biomass cascading, and the integration of ecological and technological aspects of sustainable resource management. This misalignment restricts the ability of current educational systems to equip stakeholders with the practical competencies needed to apply CE principles in forestry [18,19,45].

These findings highlight the urgent need for educational frameworks that are integrated, practice-oriented, and tailored to specific sectors, effectively connecting scientific knowledge, industrial applications, and policy objectives in a coherent and practical manner. Respondents from all participating countries emphasized the crucial role of collaboration between universities, research institutions, and enterprises as a foundation for effective knowledge transfer and innovation. However, such collaborations are often fragmented, short-term, and project-based, lacking institutional continuity and cross-sectoral coordination. These observations are consistent with previous studies that stress that sustainable bioeconomy transitions depend not only on technological capacity but also on social learning mechanisms that foster mutual understanding between academia, industry, and local communities [15,18,19,47]. Research has further shown that capacity-building in CE education requires long-term partnerships and institutional learning networks capable of translating innovation into practice [24,25,44,48].

The analysis further revealed notable differences among countries and stakeholder groups. Respondents from FI and SE expressed higher satisfaction with the available learning opportunities, reflecting their advanced, innovation-driven education systems, where circular bioeconomy topics are increasingly integrated into forestry curricula [42,43]. In contrast, participants from PL, LV, and LT highlighted structural limitations, such as insufficient access to experts, a lack of forestry-focused educational materials, and limited opportunities for practical training. These disparities underscore the need to enhance transnational cooperation and facilitate the transfer of educational practices and teaching models from countries with established circular economy frameworks to those still developing sector-specific educational pathways for circular economy [44,46]. Coordinated regional efforts could thus help bridge existing gaps and promote a more balanced and inclusive circular economy transition across the BRS.

The observed diversity in educational needs and stakeholder engagement across the five Baltic Sea Region countries can be attributed to several contextual factors. First, varying levels of institutional maturity affect the effectiveness of circular economy (CE) principle integration into policy and educational frameworks. Countries with more developed governance systems and institutional support mechanisms tend to have better infrastructure and incentives for CE education, fostering greater stakeholder awareness and capacity building. Second, differences in educational systems significantly influence the availability and accessibility of CE-related content. In some countries, flexible, integrated formal and informal education programs enable more effective dissemination of circular bioeconomy knowledge, whereas others may be limited by rigid curricula or less developed lifelong learning structures. Third, the maturity of national CE policies determines the extent to which CE concepts are embedded across sectors. Regions with advanced CE strategies show greater alignment between educational priorities and policy goals, thus facilitating strategic capacity building. Finally, social and cultural factors, including attitudes towards sustainability, innovation culture, and traditions of cross-sector collaboration, affect stakeholder motivation and the effectiveness of educational initiatives. Variations in these factors contribute to different levels of engagement and knowledge among countries. These explanations align with the broader literature, which emphasises that successful CE adoption relies heavily on institutional robustness, policy coherence, and the socio-cultural context. Incorporating these theoretical insights enhances the study’s academic value by contextualising empirical differences within the established frameworks of institutional and systemic factors.

From a policy and institutional perspective, the findings suggest that education should be recognized as a strategic driver of circular transformation rather than merely a supplementary or supportive element. National authorities and sectoral organisations should prioritize creation of interdisciplinary learning platforms that explicitly incorporate forestry-related aspects of the circular economy (CE), including environmental sciences, material technologies, management, and innovation. These platforms have the potential to bridge the gap between academic knowledge and industrial needs, especially in sectors closely linked to forestry, such as food processing, cosmetics, and water management, which showed lower satisfaction levels in this study. Additionally, expanding the use of digital and hybrid learning formats, which are highly valued by younger respondents and consumers, can improve accessibility, adaptability, and participation in CE-related education [19,25,47].

The proposed conceptual Education Roadmap offers a practical and forward-thinking framework for addressing these challenges. By outlining core competencies, stakeholder responsibilities, and key thematic areas, the roadmap provides strategic guidance for aligning educational content and delivery methods with the goals of sustainable forest management and circular bio-economy development. This notably emphasises the need to move beyond generic circular economy education towards sector-specific learning approaches that reflect the unique dynamics of forestry and related industries [15,18,44]. Furthermore, the roadmap advocates long-term partnerships among academia, industry, NGOs, and local communities, fostering a cohesive and inclusive educational ecosystem. In this context, education acts not only as a catalyst but also as a bridge in the transition towards a sustainable, resource-efficient, and innovation-driven forestry bioeconomy in the BRS.

Our approach stands out from the more generalised CE education models used in other regions or sectors by uniquely integrating quantitative stakeholder input from multiple countries with qualitative analyses of educational content specifically tailored to the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. This sectoral and regional contextualisation enhances the roadmap’s relevance and applicability, complementing broader CE educational efforts by offering targeted strategies that address distinct challenges and opportunities in forestry, such as biomass valorization and circular supply chains. This framework provides novel insights and a practical foundation for scaling CE education in bioeconomy-dependent regions worldwide.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study presents a succinct Conceptual Framework for an Education Roadmap designed to incorporate circular economy principles into forestry and bioeconomy education throughout the BSR. The framework underscores the importance of coordinated action among key stakeholder groups and emphasises that effective CE education necessitates systemic alignment among learning environments, governance structures, and societal engagement. The findings suggest that enhancing CE education involves integrating circular competencies into higher education and professional training, improving policy coherence and institutional capacity to embed circular learning in regional strategies, and increasing awareness and participation through accessible tools for broader society. To accelerate this transition, long-term partnerships among universities, research organisations, public authorities, and civil society should be prioritised. Digital learning formats, transnational cooperation, and pilot initiatives offer promising avenues for scaling and harmonising CE-related curricula in the forestry and bioeconomy sectors. Overall, the proposed framework establishes a foundation for an adaptive and collaborative education ecosystem capable of supporting a regional shift toward a circular economy. Future efforts should focus on operationalising the roadmap, testing it in real educational settings, and evaluating its impact on CE adoption across the BSR. The developed education roadmap fosters the realization of SDGs, particularly by enhancing quality education, promoting responsible consumption and production, and supporting sustainable management of forest ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Concept M.S., methodology, M.S.; software, E.W.; validation, M.S., E.W. and P.M.; formal analysis M.S.; investigation, E.W., P.M.; resources, E.W., P.M.; data curation, P.M., E.W.; writing—original draft preparation, E.W.; writing—review and editing, M.S.; visualization, E.W.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

European Regional Development Fund: #C023; Mineral and Energy Economy Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences: Subvention of the Division of Biogenic Raw Materials.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with recognised ethical standards for social research and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1975, revised in 2013). Participation was entirely voluntary, and all respondents were informed about the purpose of the study, the confidentiality of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any time. The survey did not involve any personal, medical, or sensitive data, and no identifying information was collected. The research complied with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and national standards for research integrity. Given the nature of the study, an anonymous survey addressing knowledge about education aspects in forestry sector, it was conducted in line with institutional ethical guidelines applicable to non-interventional social research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References