1. Introduction

The traffic assignment problem is a foundational element in transportation planning, tasked with allocating system-wide travel demand across a congestible network. The primary objective is to determine route flows and the resulting traffic conditions, such as congestion levels [

1]. This process fundamentally requires a comprehensive understanding of both transportation supplies including the road network, public transportation services, and their operational characteristics and traffic demand, typically represented by an Origin-Destination (O-D) matrix.

The selection of traveler routes, known as route generation or enumeration, is a critical component, especially within Stochastic User Equilibrium (SUE) traffic assignment models. The need to consider multiple routes per O-D pair reflects real-world cognitive biases and information imperfections inherent in route choice [

2]. Ref. [

3] discussed the complexity of route choice between electric and conventional vehicles mode.

Sustainable transportation planning requires accurate traffic assignment models that can reliably estimate network-wide congestion levels, vehicle-hours traveled, fuel consumption, and emissions. Stochastic User Equilibrium (SUE) models assume a critical role in this context by incorporating traveler perception uncertainty and behavioral realism, enabling more credible evaluation of sustainability-oriented policies. However, the computational efficiency of these models depends on appropriate route set sizing; excessive route enumeration increases burden without proportional accuracy gains, while insufficient coverage undermines the reliability of sustainability assessments.

In real-world networks, the number of possible routes increases exponentially with network size, making the explicit definition and selection of actually used routes a significant computational challenge, even for small networks. The most straightforward approach is to generate K-paths for each O-D pair. While [

4] proposed a constrained method to find feasible K-shortest paths, determining what percentage of demand effectively utilizes a specific number of generated routes remains a persistent challenge.

In terms of required route set in traffic assignment, ref. [

5] states that a large number of routes are required to achieve acceptable coverage, highlighting the importance of securing enough alternative routes during the pathfinding and modeling process. However, other researchers have presented contrasting observations, particularly in the context of deterministic user equilibrium (UE) traffic assignment models. Ref. [

6] analyzed the characteristics of route sets in the solution of deterministic UE models and observed an average of 2.686 routes per O-D pair. Specifically, they noted that 56% of O-D pairs were connected by only a single route. Ref. [

7] used the gradient projection algorithm to solve the deterministic UE model and found that most O-D pairs had an average of three or fewer routes. In contrast to deterministic approaches, studies involving stochastic traffic assignment generally indicate a requirement for a greater number of routes to achieve stable and accurate results. Ref. [

8] analyzed the number of routes required when performing logit-based stochastic traffic assignment and found that an average of 30 or more routes per O-D pair were needed for the traffic patterns to stabilize. Ref. [

9] analyzed the correlation between Global Positioning System (GPS) data and route generation algorithms and determined that generating approximately 40 routes per O-D pair captured 80% of observed traffic volume.

The primary objective of this research is twofold: (1) to investigate traffic patterns based on a given number of routes, and (2) to determine the minimum requisite number of routes required for traffic patterns to stabilize within SUE traffic assignment. Against this background, efficient transportation planning is closely linked to the broader goal of sustainability, extending beyond mere congestion mitigation. Accurate and efficient traffic assignment models are essential for reducing fuel consumption, emissions, and overall societal costs. In particular, improving the behavioral realism of route choice, addressed in this study, is crucial for supporting Transportation Demand Management (TDM) strategies and route choice modeling for future eco-friendly vehicles (e.g., electric vehicles). Therefore, by determining the minimum number of routes required for the stability and efficiency of SUE models, this research contributes practical guidelines for reducing computational burden and designing sustainable transportation networks.

This investigation provides the first systematic comparative analysis of the influence of route set size on Weibit-based SUE models (MNW and PSW). Unlike prior work which primarily focused on Logit models, this study quantifies the requisite number of routes for flow stabilization in the Weibit SUE framework and compares these stability characteristics against established logit-based SUE models (i.e., MNL and PSL). The route set used in this study was adopted from the route set utilized in [

8], which integrates the link elimination method and the penalty method (specifically, applying a 5% penalty to travel times on shortest path links).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces relevant studies concerning logit-based and weibit-based route choice models, including theoretical background and model formulation.

Section 3 provides the solution algorithm for solving the logit- and weibit-based SUE traffic assignment model for a given route set.

Section 4 presents numerical experiments demonstrating flow stability and the required number of routes across the four SUE models. Finally,

Section 5 provides concluding remarks.

2. Logit and Weibit Route Choice Model

This section provides a brief explanation of logit and weibit based route choice models, including their theoretical background and mathematical formulations.

2.1. Overview of Logit and Weibit Route Choice Model

The Random Utility Maximization (RUM) framework remains the foundational theoretical underpinning for modeling discrete choices, particularly within the context of route choice [

10]. This paradigm asserts that a decision-maker assesses the utility of each available, mutually exclusive alternative (route) and invariably selects the option that maximizes their perceived utility.

Among the earliest and most widely adopted RUM-based models is the Multinomial Logit (MNL) model [

11]. Its enduring popularity stems from its mathematical tractability: it is derived under the assumption of independently and identically Gumbel-distributed error terms, resulting in choice probabilities calculable through a closed-form equation. This computational advantage has facilitated its extensive application across diverse transportation studies [

12]. Despite its tractability, the MNL model’s foundational assumptions impose significant behavioral limitations in the route choice domain. Specifically, the Independence from Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) property and the prerequisite of constant error variance are often considered behaviorally unrealistic. Although Nested Logit-Based models were developed to address the IIA (Independence from Irrelevant Alternatives) problem [

8,

13,

14], the model has limitations in fully resolving the Independence component of IIA.

To circumvent these restrictions, alternative model structures, notably the weibit-based models, have been proposed. This models primarily includes the Multinomial Weibit (MNW) model [

15] and subsequent extensions, such as the path Size Weibit (PSW) model [

16,

17]. Furthermore, the Weibit model has recently found application in location problems [

18]. These models replace the Gumbel distribution assumption with a Weibull distribution for the error terms (or perceived costs). A key motivation for using the Weibull distribution is its ability to relax the assumption of identically distributed errors, thereby allowing the model to capture heterogeneous perception variance the idea that the degree of uncertainty in perceiving route costs might vary depending on the cost itself (e.g., longer trips might have greater perceived variability) [

19]. Crucially, this innovation often maintains a closed-form structure for choice probabilities, preserving the computational efficiency prized in the MNL framework. The PSW model represents a further methodological refinement, incorporating mechanisms analogous to the Path Size Logit (PSL) modification of the MNL to directly address the route overlap problem (i.e., the Irrelevant Alternatives problem) [

17]. The PSW model can, therefore, effectively mitigate the constraints imposed by the IIA property. Recent research has robustly validated weibit-based choice models across various contexts, including road travel mode, and railway itinerary choices [

20,

21,

22]. Notably, ref. [

23] found that a multiplicative error structure, which evaluates relative utility differences, may outperform the standard additive utility function. This suggests the weibit model, with its focus on relative differences, could be superior to the traditional logit model in some scenarios.

2.2. Route Choice Probability

The assumption of logit models is that the random error terms within the utility functions of various alternatives are independent and identically distributed (IID) following a Gumbel distribution with a consistent variance. The utility function, shown in Equation (1), is composed of the sum of a deterministic disutility and a random error

where

is the deterministic disutility; and

is the random error term associated with alternative

i.

Along with the utility function above, the basic multinomial logit model for route choice is formulated as:

where

θ is the dispersion parameter,

is the set of routes between O-D pair

rs;

is the cost on route

k between O-D pair

rs.

In contrast to MNL model, which employs an additive utility function, the foundational MNW model is developed a multiplicative form of the disutility function.

where

is the location parameter with alternative

i.

The basic multinomial weibit model for route choice is formulated as:

where

is a shape parameter; and

is a location parameter between O-D pair

rs.

From Equations (2) and (4), we can see that the probability of the MNL is determined by the difference in disutility, while the probability of the MNW is determined by the relative difference in disutility between each alternative. Refs. [

20,

21] provide further information on the derivation of these formulas and a comprehensive discussion of Gumbel and Weibull distributions, and ref. [

14] conducted research on the location parameter of the weibit model.

As mentioned above, the MNL model assumes IID property, whereas the MNW model relaxes the assumption of identical perception variances. The path size (PS) factor was introduced to relax not only the identical perception variances assumption but also the independent distributed assumption [

16]. Ref. [

24] developed the PSL model to address the route overlapping problem inherent in the MNL formulation. The PSL model introduces correction terms based on path size factors that penalize routes according to their degree of overlap with other alternatives.

where

is the PS factor of route

k between O-D pair

rs;

la is the length of link

a;

is the length on route

k between O-D pair

rs; and

is the route-link indicator, 1 if link

a is on route

k for between the O-D pair

rs and 0 otherwise. Routes that heavily overlap with other alternatives will have a smaller PS value, whereas a larger PS value indicates more distinct paths.

The PSL probability and PSW probability, incorporating the PS factor, are as follows.

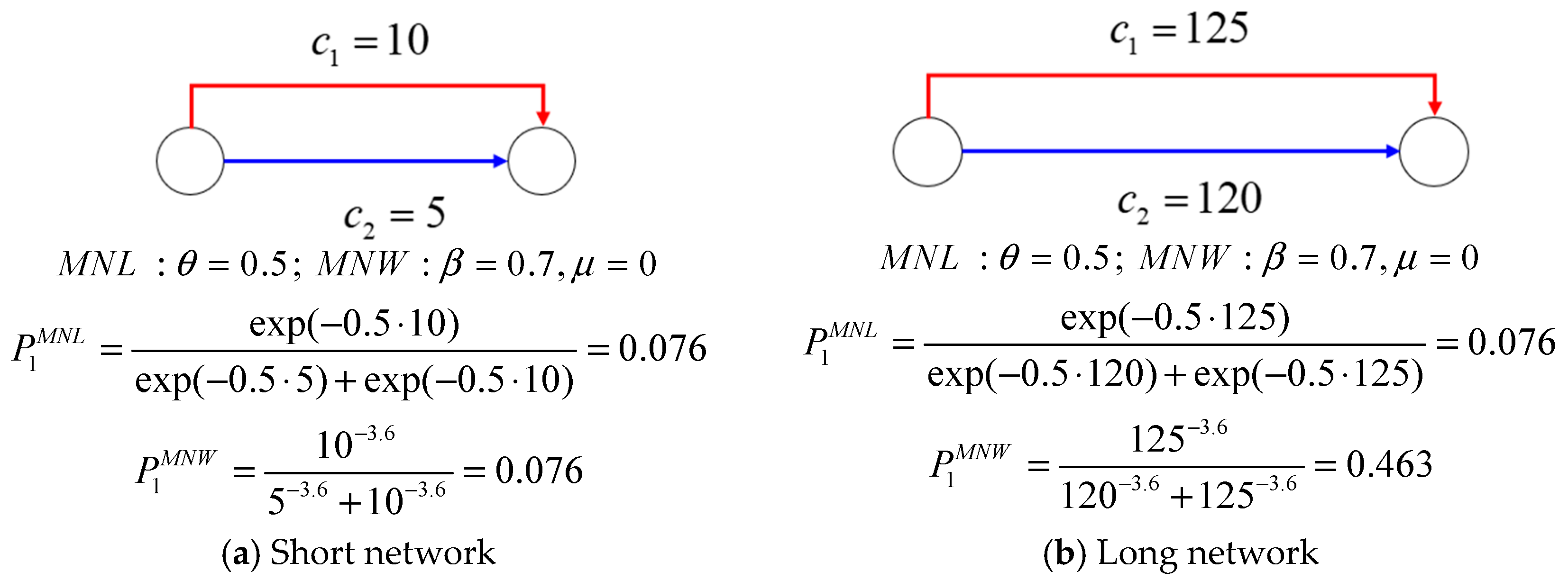

Figure 1 illustrates the route choice probabilities for both the MNL and MNW models. In both networks, the travel cost of the upper route (c

1) is 5 units (e.g., 5 min) greater than the travel cost of the lower route (c

2). However, in the short network, the upper route cost is twice that of the lower route, while in the long network, it is only less than 4%. The MNL model primarily considers only the absolute difference in route travel time. This indicates that even with different route costs, it results in the same route choice probability for both the short network and long network. This drawback results from the inability to account for perception variance associated with different costs. In contrast, the MNW model considers the relative difference in travel costs. The model recognizes that a cost difference in five units is more significant on a short network than on a long network. Unlike the MNL model, the MNW model does not require the identically distributed assumption that is a prerequisite for each route in the MNL model. This allows the MNW model to better capture route-specific perception variance.

Figure 2 illustrates the impact of route overlap in both the MNW and PSW models. In each network, there are three available routes; while routes 1 and 2 have identical travel times, the proportion of overlap between these two routes is set at 80% and 90%, respectively. In the case of the MNW model, route overlap is not accounted for, resulting in identical probability values for routes 1 and 2 regardless of the degree of overlap. Thus, the choice probability for the two routes (i.e., route 1 and route 2) is computed as 14%. In contrast, the PSW model produces different outcomes depending on the overlap ratio. When the overlap between routes 1 and 2 is 80%, these two routes choice probability is 9.0%, and when the overlap increases to 90%, these two routes choice probability decreases to 8.3%. If the overlap reaches 100%, the two routes are effectively indistinguishable and can be considered as a single route, resulting in a value identical to that shown in

Figure 1a, which is 7.6%.

2.3. Route Choice Probability Model Formulations

In SUE, a concept introduced by [

25,

26], no drivers can reduce their perceived travel time by independently changing routes. Unlike deterministic models that assume drivers choose the shortest path, SUE incorporates a probabilistic route choice model. Ref. [

27] developed the initial logit-type mathematical programming (MP) formulation for logit-based SUE, while [

16] provided an MP formulation for the weibit-based SUE model. Both logit and weibit models were later formulated as unconstrained mathematical programs by [

17,

26] respectively. In this paper, the variational inequality (VI) formulation based on [

28,

29] is presented as follows.

where

represents the feasible set defined by Equations (9) and (10):

Equation (9) is the travel demand conservation constraint between O-D pair

rs; and Equation (10) is a non-negativity constraint on the route flows. The optimal flow pattern (

) is represented by the vector form,

is a general mapping from the feasible flow set (

). This mapping

can define as a gap function between the current and the auxiliary flow patterns.

where

P(f) is the vectors of route choice probability under current flow pattern

f, and

q is the vector of O-D demands. Then, the formulation presented in Equation (8) is as follows.

3. Solution Algorithm

A solution algorithm for SUE traffic assignment, which utilizes a pre-generated route set, is presented in this section.

3.1. Route Set Generation

Route choice setting is complicated, especially in large urban areas where thousands of potential routes can exist and are hard to enumerate [

30]. Hence, generating available route sets is a crucial problem in route generation. Various methodologies have been proposed in existing literature. Ref. [

9] recently reviewed nineteen methods used in the research and categorized them into three main approaches: Link elimination, Link penalty, and Labeling.

Link elimination: This algorithm builds upon the K-shortest path algorithm. When determining the K-shortest paths (typically based on distance or time), certain links from previously found shortest paths are eliminated from the network.

Link penalty: Similarly to link elimination, the link penalty method also aims to find alternative routes. However, instead of deleting links from the original network, it adds a fixed penalty to links that were part of a previously identified shortest path. This penalty makes those links less attractive, encouraging the algorithm to find new shortest paths that avoid them.

Labeling: The labeling method stands apart from the previous two. It begins by defining a specific label or optimization goal before calculating a route. The algorithm then searches for routes that best achieve this target.

For the comparative analysis of logit and weibit-based SUE models, ensuring a diverse and behaviorally relevant set of routes is essential to accurately capture traveler choices. To achieve this, the study adopted the robust hybrid algorithm utilized by [

8]. This method iteratively generates paths by intelligently combining two established techniques: the link elimination method proposed by [

31] and the penalty method proposed by [

32]. The procedure for each O-D pair is as follows:

Shortest Path Identification: The algorithm first identifies the shortest path based on current travel times.

Iterative Path Search: In each iteration, the algorithm applies the methods to force the generation of distinct alternative routes. Specifically, links comprising the previously identified shortest path are either entirely removed from the network (following [

31]’s approach), or a 5% penalty is applied to their travel times (following [

32]’s approach). This penalty makes those specific links less attractive for subsequent shortest path searches, promoting the selection of genuinely different detours.

Termination: This iterative application of the hybrid strategy continues until no new paths can be found between the O-D pair, thereby creating a comprehensive and diversified route set for the SUE assignment.

This transparent approach ensures that the route set of 174,491 routes used across the Winnipeg network, averaging about 40 routes per O-D pair, is based on a sound and reproducible methodology. Furthermore, this specific route set is well established and has been used in previous studies (e.g., [

14,

16,

17,

33]) for analyzing route choice models.

3.2. Self-Regulated Averaging (SRA) Scheme

To solve the VI formulation in Equations (8)–(10) mentioned above, route-based algorithm is adopted. Overall, it is similar to the partial linearization algorithm [

34,

35], but to determine the step size, the SRA scheme developed by [

36] is adopted to determine a suitable step size for updating the solution vector. Recently, SRA scheme was applied to solve the nested logit-based stochastic user equilibrium problem [

13].

The SRA scheme updates the stepsize as follows.

where λ

1 > 1 and 0 < λ

2 < 1.

and

are the vector forms of

and

at two consecutive iterations

n − 1 and

n, where

is the auxiliary flow on route

k between O-D pair rs. Consistent with the Method of Successive Averages (MSA) scheme, convergence is guaranteed by satisfying specific conditions, as established by [

36,

37,

38].

Similarly to the MSA method, the SRA scheme uses a decreasing stepsize sequence. However, SRA more effectively manages the reduction speed by employing parameters and based on the residual error (the difference between the current and auxiliary solutions in two subsequent iterations). Specifically, triggers a faster stepsize decrease (via Equation (14)) when the residual error increases. Conversely, is used to slow the stepsize reduction if the residual error is low, thereby preventing slow convergence.

3.3. Stopping Criterion

A convergence check is performed using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

where

is the auxiliary route flow vector,

is the number of routes in the route set, and

is the tolerance error.

It is important to note that the stopping criterion in Equation (16) offers a more conservative approach compared to the commonly adopted criterion (i.e., ) because .

The criterion can also be directly interpreted as a reflection of the fixed-point formulation.

3.4. Solution Procedure

The detailed algorithmic steps for solving the SUE traffic assignment problem are provided as follows. Following initialization, the costs associated with a predefined set of routes are computed. Subsequently, the algorithm performs the search direction phase, which necessitates a mapping operation incorporating the probability functions detailed in Equations (2) and (3). This is followed by a flow update process, executed via the SRA algorithm. Finally, the convergence check with a RMSE is performed. Note that SUE traffic assignment for each route set size (

K, ranging from

K = 2 to 50) was performed as a separate and independent experiment using the algorithm. This indicates that all variables, including the flow vector (

f) and the general mapping flow vector (

), were re-initialized for every change in K, thereby ensuring the comparability of results across all experiments. Consequently, a total of 49 complete SUE assignments were executed.

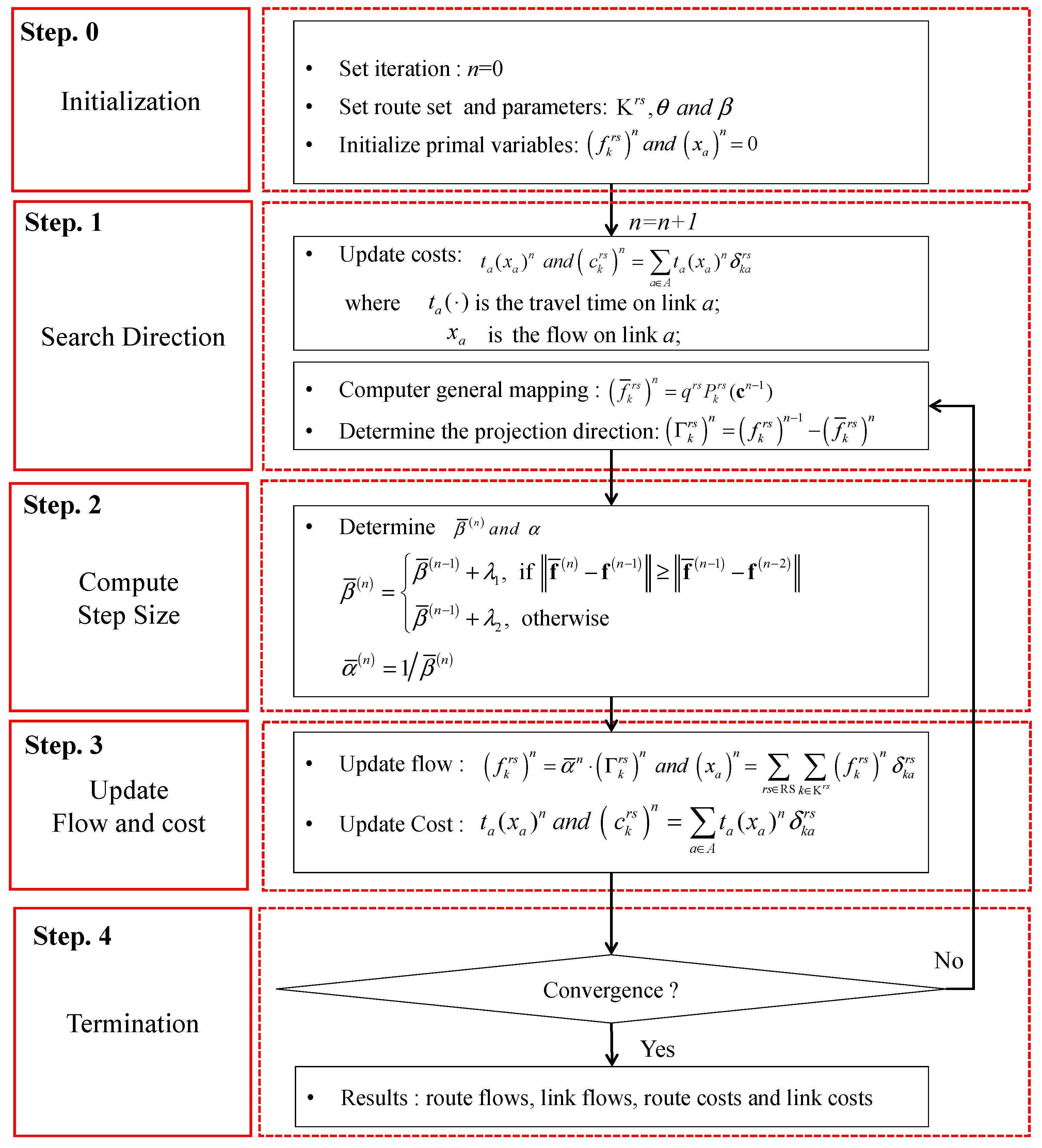

Figure 3 presents the detailed solution procedure.

4. Numerical Results

In this section, we present numerical experiments to examine the customized solution algorithm and analyze the impact of the number of paths used. Experiment 1 is designed to examine the customized solution algorithm. Experiment 2 focuses on assignment results regarding perceived travel time, specifically looking at the influence of the routes used. Experiment 3 conducted a sensitivity analysis on the dispersion parameter for the logit-based models and the scaling parameter for the weibit-based models. Finally, Experiment 4 focuses on assignment results with considerations of route overlapping.

4.1. Description of the Experiments

The Winnipeg network, shown in

Figure 4, is used to conduct these experiments. This network consists of 154 zones, 948 nodes, 2535 links, and 4345 O-D pairs. The network structure, O-D trip data, and link performance parameters are obtained from Bentley open path (Emme 2024) software. For the experiments, a pre-generated route set from [

8] was adopted. This set comprises 174,491 routes, averaging about 40 routes per O-D pair. This specific route set is well established and has been used in previous studies (e.g., [

16,

17,

33]) for analyzing route choice models and path-based traffic assignment. The link volume-delay function is based on the BPR function in Equation (17). Additionally, an additive route travel function, shown in Equation (18), is employed, as described by [

8,

23].

where

is the free flow travel time on link

a;

Ca is the capacity of link

a; and

and

are the parameters obtained from Emme.

Regarding the other model parameters, a dispersion parameter of

θ = 0.5 was applied to both the MNL and PSL SUE models [

8]. For the MNW and PSW SUE models, a scaling parameter of

= 4.3 [

24] was used, and location parameters were set to zero [

16]. For the SRA line search method, the parameters are set as: λ

1 = 1.5 and λ

2 = 0.01.

4.2. Convergence Characteristics

Experiment 1 is designed to examine the convergence characteristics, demonstrating the stability and efficiency of the customized Self-Regulated Averaging (SRA) solution algorithm for the four SUE model formulations. The customized solution algorithm achieved a convergence accuracy of 1 × 10

−8. Note that the tolerance error used in the stopping criterion is much stricter than the typical one (i.e., 0.01 percent or 1 × 10

−4) required in practice [

39].

Figure 5 presents the results when 50 paths (out of a total of 174,491 paths) are used for maximum route generated O-D pair. As shown in

Figure 5, all models demonstrated convergence within 3 s. However, it is notable that PSL and PSW, which incorporate the path size factor, exhibit slightly longer convergence times due to the PS factor calculation process. When comparing logit-based and weibit-based models, the weibit-based model converged faster. This can be attributed to the fact that for the given routes, logit-based models do not account for perceived variability in long-distance O-D pairs, leading to more congestion and consequently requiring a longer convergence time.

4.3. Effect of Used Route Size

This section investigates the model-inherent behavioral properties of the logit and weibit-based SUE models by comparing the minimum perceived total travel time in the network based on the number of routes used between MNL and MNW. The core SUE principle states that travelers choose routes to minimize their own perceived travel time, leading to an equilibrium where no traveler feels they can unilaterally reduce their perceived travel time by switching routes. For each O-D pair, the expected perceived travel time for logit-based models [

40] and weibit-based models [

16] is as follows.

where

and

the minimum perceived travel time for logit-based model and weibit-based model, respectively, between O-D pair

rs.

Table 1 and

Figure 6 demonstrate that increasing route diversity contributes significantly to overall system efficiency. This improvement is evidenced by a noticeable reduction in both the perceived total travel time and the average route travel time across the two models. The observed efficiency gain primarily results from the inclusion of additional non-dominated and behaviorally efficient routes within the travelers’ choice set, promoting a more balanced flow distribution across shorter and less congested routes. However, the marginal benefit of adding new routes diminishes beyond a certain threshold, approximately 30 routes per O-D pair. Specifically, as the number of available routes increases from 5 to 30, the perceived total travel time decreases markedly by 2050 h for the MNL model and 3716 h for the MNW model (from 15,293 to 13,243 h in MNL, and from 13,488 to 9772 h in MNW). In contrast, further expansion of the route set from 30 to 50 routes yields only minor additional reductions of 196 h and 422 h in MNL and MNW, respectively (from 13,243 to 13,047 h in MNL, and from 9772 to 9350 h in MNW). These results suggest that the majority of effective and behaviorally relevant routes are already captured within a route set of approximately 30 routes per O-D pair. Accordingly, setting the route generation limit around 30 routes appear sufficient to ensure stable convergence and efficient traffic assignment outcomes in both MNL and MNW frameworks.

For a more granular investigation,

Table 2 presents results obtained by categorizing the O-D pairs into three groups based on their uncongested shortest-path travel times: short (2.07–10.16 min, 1448 pairs), medium (10.77–16.12 min, 1448 pairs), and long (16.13–37.05 min, 1448 pairs). This grouping enables a comparative analysis of model behavior across different travel-time scales. Overall, the general trend observed in

Table 2 aligns with the pattern shown previously in

Table 1. The MNL model demonstrated a consistent response across short, medium, and long-distance O-D groups, whereas the MNW model exhibited more distinct variations depending on travel-time category. For short-distance pairs, the increase in the number of routes had only a negligible influence, with minimal difference observed between the 45 route and 50 route scenarios. In the medium group, perceived total travel time decreased as the route count increased, although to a lesser extent than in the long group. The MNW model followed a trend similar to that of the MNL model, albeit with a more pronounced reduction in travel time. For long-distance O-D pairs, both models exhibited clearer decreases in perceived total travel time as the number of available routes increased. Notably, even at the upper bound of 50 generated paths per O-D pair, the MNW model continued to yield substantially greater improvements compared to the MNL model. This sustained improvement in the MNW model for long-distance pairs is rooted in behavioral realism because route choice uncertainty (perception variance) is inherently greater for longer trips. Since the MNW model accounts for this cost-dependent perception variance, it requires a slightly larger set of distinct alternatives beyond the 30 routes threshold sufficient for shorter trips to fully represent the broader spectrum of perceived possibilities and efficient detours required for a stable equilibrium under high uncertainty.

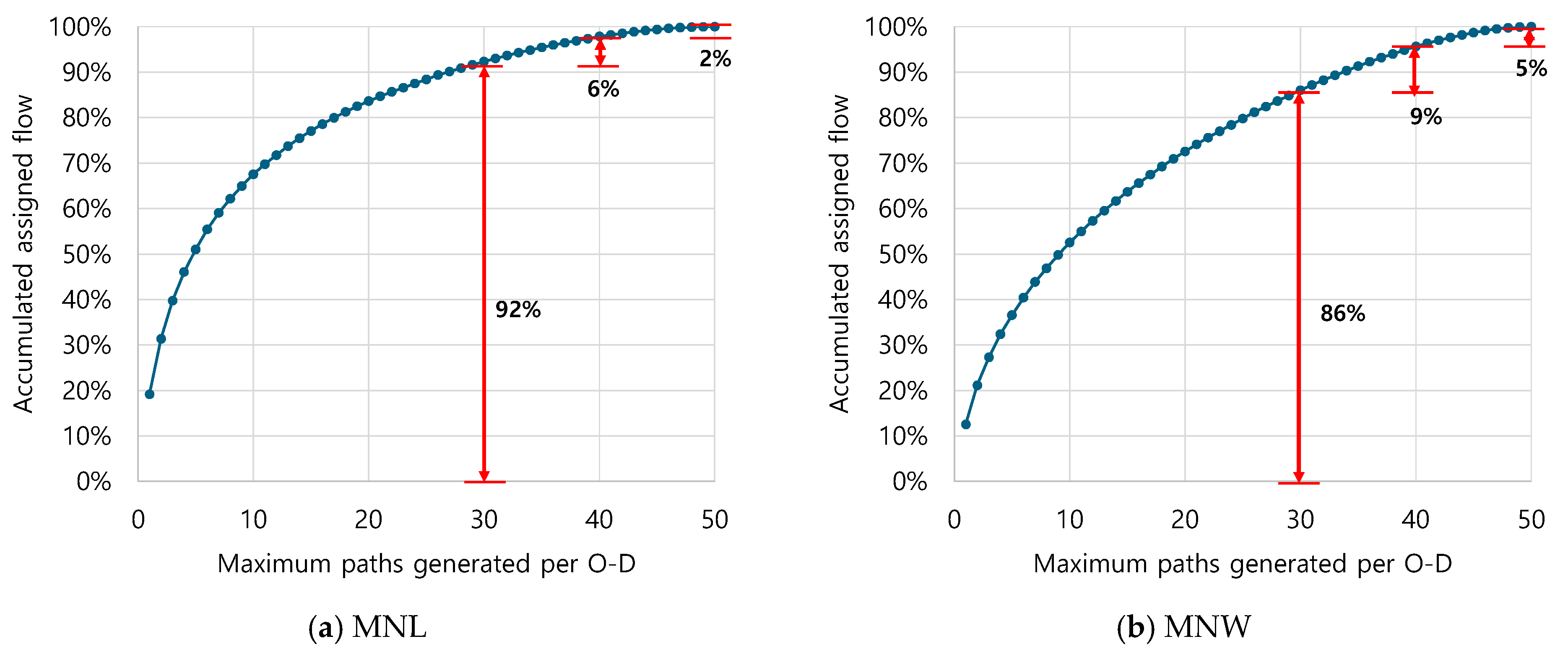

Figure 7 presents the percentage of assigned traffic flows corresponding to the number of routes used. In the MNL model, approximately 92% of total demand is assigned within the 30 routes per O-D pair. When the number of routes increases from 30 to 40, an additional 6% of demand is captured, and only 2% more is assigned when expanding from 40 to 50 routes. This outcome corroborates the earlier finding that most travel demand is concentrated within approximately 30 efficient and behaviorally relevant routes, while the influence of adding further routes remains marginal. In the MNW model, about 86% of total demand is assigned within the 30 routes per O-D pair. When the path set expands to 40 routes, the captured demand rises to 95%, indicating that additional routes beyond 30 contribute to improved coverage of travelers perceived route choices. This pattern is particularly evident for longer trips, where the perception variance effect in MNW is more pronounced than in MNL. Consequently, MNW tends to require a slightly larger set of routes to represent the full spectrum of travelers’ route preferences. Nonetheless, the use of approximately 40 routes appears sufficient to capture over 95% of total demand, suggesting that further expansion yields limited additional benefit.

4.4. Sensitivity Analyses of Model Parameters

The preceding analysis in

Section 4.2 was conducted using standard model parameters adopted from established literature, a dispersion parameter

θ = 0.5 for the logit-based models (MNL and PSL) and a scaling parameter

β = 4.3 for the weibit-based models (MNW and PSW). The selection of these specific values carries distinct behavioral implications. For example, at

θ = 0.5, the MNL model assigns 92% of flow to the shorter route and 8% to the longer route, given a fixed 5-unit cost difference, regardless of total path length. This behavior highlights the parameter’s independence from absolute route cost. Conversely, the

β = 4.3 parameter in the MNW model results in a more dispersed flow allocation, particularly toward relatively longer travel routes, reflecting its inherent heterogeneous perception variance. In the following analyses, a sensitivity analysis is performed on the key behavioral parameters

θ = 0.4 and

β = 3.6 to confirm the robustness of the findings. The different parameter settings tested in the two-route example are summarized in the following

Table 3.

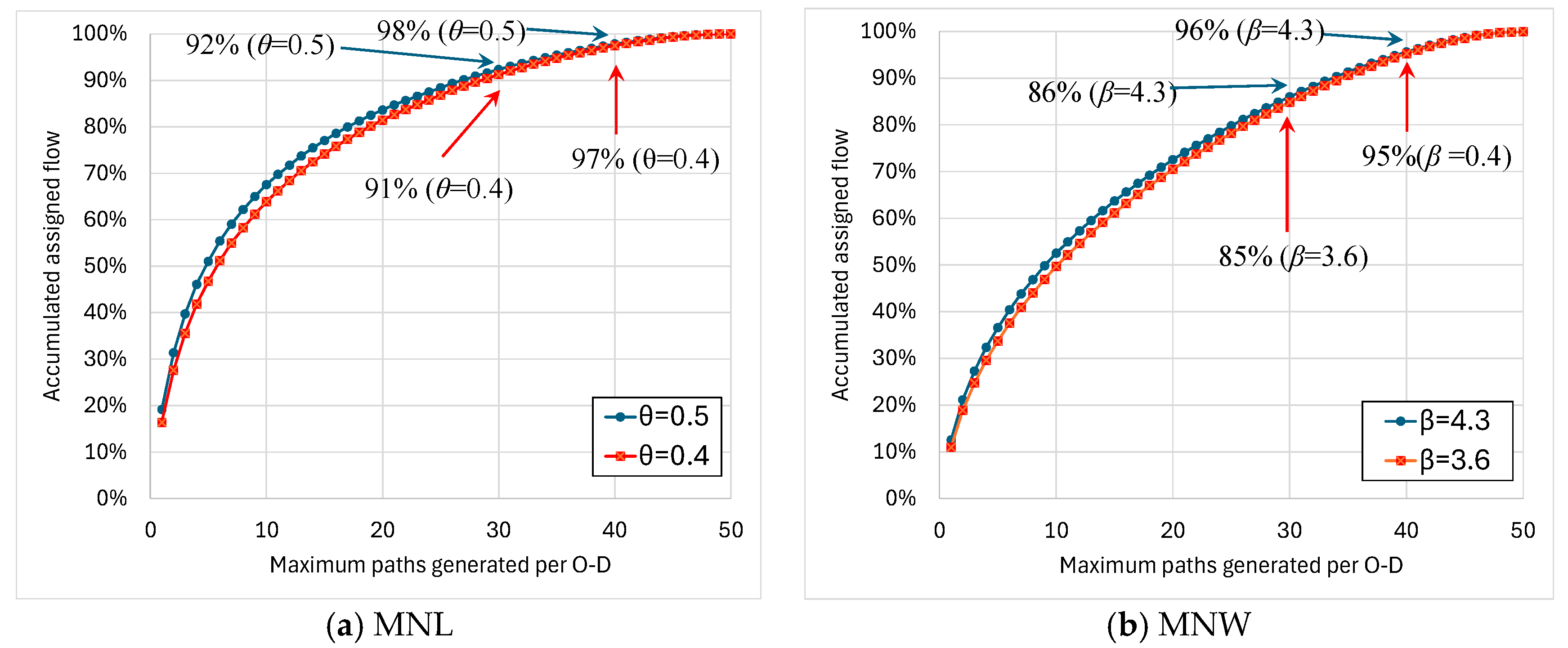

Figure 8 presents the results of the parameter sensitivity analysis, comparing assigned traffic flows corresponding to the number of routes used (e.g., Case 1:

θ = 0.5,

β = 4.3) and the sensitivity test (Case 2:

θ = 0.4,

β = 3.6). A critical observation across all models and cases is the robustness of the stabilization threshold. Notably, the difference in the percentage of accumulated flow assigned up to the 30th and 40th routes was found to be only 1%. Although using different parameters results in differences in the assigned traffic volume and the corresponding travel time, the requisite number of routes required for stability exhibits a consistent pattern across the cases.

4.5. Effect of Route Overlapping

This section analyzes the flow discrepancies between the base models and the PS models (MNL vs. PSL, and MNW vs. PSW) to assess the model-inherent behavioral sensitivity to route overlap effects.

Table 4 is dedicated to comparing the average PS values of the network, based on the number of routes used, and the assigned traffic flows of the two models. The comparison of assigned traffic flows was conducted using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for link flow.

where

is the number of links

As shown in

Table 4, increasing the maximum number of generated routes per O-D pair leads to a decrease in the PS value, where a smaller PS value indicates a higher degree of route overlap. This pattern implies that as additional routes are considered, the similarity among routes increases, thereby lowering the PS value. At the same time, a comparison of link flows between the models without PS consideration and those incorporating PS shows a decreasing trend in the MAE. Although the PS value decreases with the inclusion of more routes, the overall traffic flow patterns remain largely consistent, suggesting that the influence of route overlap becomes less significant as the number of routes increases. It is also noteworthy that the difference in link flow is more pronounced for the weibit-based model than for the logit-based model. Specifically, the logit-based model reaches a stable state after approximately 25 routes, with negligible variations thereafter, whereas the weibit-based model continues to exhibit changes until stabilizing only after around 45 routes. This result indicates that the weibit-based model is more sensitive to route overlap effects in the process of achieving stochastic user equilibrium (SUE).

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the flow allocation comparison and route flow distributions as the PS value with 50 maximum routes. The flow allocation results are depicted in GIS maps with coded color and thickness to highlight the link flow differences (e.g., green color indicates that PSL and PSW link flows are higher than MNL and MNW link flows). From these figures, there are visible differences in the assignment results between the logit-based models and weibit-based models. Particularly, the flow allocations for the weibit-based models show a significant difference in ring road (or outer road), where roads are less overlapping even if the route is a detour. This is because, in CBD areas, roads are relatively denser, leading to many overlapping routes. Consequently, there was a propensity for flow to use outer roads to avoid these overlapping routes. Conversely, in the case of the logit-based model, although some differences arise compared to the weibit-based model, this is because the logit-based model uses the same perception variance for both short- and long-distance trips. In this case, travel time tends to be considered more important than overlap compared to the weibit model. Generally, the use of outer roads is more prevalent in long-distance travel, and the weibit model, which considers the perception variance of long-distance travel, appears to show a greater impact of route overlap. In addition, it clarifies that weibit models’ superior overlap sensitivity and preference for outer-ring routes arise from their multiplicative error structure and cost-dependent perception variance, fundamentally distinguishing them from logit models’ ID assumptions. Unlike logit models, which employ additive utility as shown in Equation (2) and assume constant perception variance across all routes, weibit models use a multiplicative formulation as shown in Equation (3), where perception variance scales with route cost magnitude. This cost-heterogeneity increases uncertainty differentiation (i.e., high-cost inner-city routes exhibit larger perceived variability, while lower-effective-cost outer routes have smaller perceived variability, making them relatively more attractive). In PSW, this interacts with the PS factor, which penalizes overlap more aggressively under heterogeneous variance, driving stronger flow redistribution toward less-correlated peripheral routes.

Figure 10 illustrates route flows distribution according to the PS factor defined in Equation (2). As a reminder, a lower PS value reflects greater overlap among routes, whereas a higher PS value signifies that the routes are more distinct. The results show that the MNL and MNW models tend to allocate a higher proportion of route flows to routes with lower PS values than the PSL and PSW model, respectively. This occurs because the MNL and MNW models do not account for route overlap, whereas the PSL and PSW models incorporate the PS factor to adjust route choice probabilities and allocate flows more realistically among overlapping routes.

5. Conclusions

This study provided the first comprehensive comparative analysis quantifying the impact of route set size on the performance and behavioral realism of both logit-based and weibit-based SUE models. Crucially, it addresses a critical gap in the literature by systematically determining the route set size required for stable weibit SUE assignment, which was not previously reported in studies focusing on weibit model formulation. Based on the number of generated route sets per O-D pair, the analysis examined how increasing route diversity affects system-wide travel efficiency, the distribution of assigned demand, and route overlap effects.

The numerical experiments, conducted using a real-world network, revealed several key insights. First, increasing the diversity of routes available for assignment led to efficiency gains, evidenced by substantial reductions in both the perceived total travel time and the average route travel time. These improvements are primarily attributed to the inclusion of additional, non-dominated alternatives that enable a more balanced allocation of traffic across the network, thereby relieving congestion on major routes. Notably, these gains were most pronounced when the route set was expanded to approximately 30 routes per O-D pair, after which the marginal benefit of adding further routes diminished rapidly. Analysis of the assigned demand percentages reinforced this finding. For the MNL model, approximately 92% of total demand was covered by the 30 routes, with only marginal additional demand assigned as the number of routes increased beyond this threshold. Similarly, the MNW model covered 86% of demand within the 30 routes, capturing up to 95% when the path set expanded to 40 routes. This pattern was particularly evident for longer trips, indicating that the greater perception variance accounted for in the MNW model required a slightly larger path set to adequately represent realistic behavioral choices. However, even in this context, expanding the route set beyond 40 provided little additional value, suggesting a practical upper bound for efficient route enumeration in large-scale applications. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrated that the MNW model exhibited greater sensitivity to route overlap than the logit-based model, resulting in increased allocation to less congested, non-overlapping peripheral routes. This indicates that the MNW model, by capturing heterogeneous perception variances, provides a superior behavioral representation, especially in networks with substantial route redundancy or overlap.

Based on these findings, the study recommends that a route set size of approximately 30 to 40 alternatives per O-D pair is sufficient to achieve stable, efficient, and behaviorally valid traffic assignment outcomes in both MNL and MNW models. This has practical implications for network planners and modelers, as it alleviates the computational burden associated with excessive route generation without compromising assignment quality. Moreover, the results underscore the importance of accounting for behavioral variance and route overlap when selecting or designing SUE model formulations for real-world applications. Specifically from a sustainability perspective, these findings yield two vital practical implications for transportation planning. Firstly, establishing a stable route set size of 30–40 routes per O-D pair provides a crucial computational efficiency benchmark, which is essential for modelers conducting frequent policy scenario analysis related to emissions and fuel consumption without incurring excessive time and energy costs. Secondly, for sustainable network design and TDM strategy evaluation, the weibit-based models (MNW and PSW) are strongly recommended. Their enhanced sensitivity to overlap and greater propensity to distribute flows to less-congested peripheral routes offers a more realistic representation of traffic redistribution, which is a prerequisite for accurately estimating the environmental benefits (e.g., reduced emissions and vehicle-hours traveled) of investments in outer ring infrastructure or CBD congestion mitigation schemes. This guidance supports the direct integration of advanced SUE models into real-world sustainability assessments and low-carbon mobility transitions.

Future research can specifically address the generalizability of the findings by exploring the variability in SUE outcomes introduced by different route set generation methods and the choice of random seeds, which is a recognized limitation in the current study. To better distinguish behavioral interpretations arising from model properties versus those resulting from route set structure, it is proposed to expand the current framework to a multi-class [

41] SUE model that can capture diverse traveler preferences beyond the simple minimum-time route assumption. Comparative analyses of the requisite route set size should be conducted across diverse network structures, using various generation heuristics (e.g., K-shortest path, labeling methods), and employing the multi-class framework to explicitly investigate the interaction between route set structure and heterogeneous user behavior. Furthermore, future directions may include the exploration of qualitative route attributes, the refined quantification of perception variance, and the applicability of these results to other assignment frameworks, such as random regret minimization [

42] and dynamic assignment models that consider time dependency. Continued development of efficient route generation algorithms and the integration of real-world behavioral data will further enhance the practical utility and robustness of SUE traffic assignment models for transportation planning.