Abstract

This study addressed the persistent limitation of discontinuous and labor-intensive compost monitoring procedures by developing and field-validating a low-cost sensor system for monitoring oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4) under tropical windrow conditions. In contrast to laboratory-restricted studies, this framework integrated rigorous calibration, multi-layer statistical validation, and process optimization into a unified, real-time adaptive design. Experimental validation was performed across three independent composting replicates to ensure reproducibility and account for environmental variability. Calibration using ISO-traceable gas standards generated linear correction models, confirming sensor accuracy within ±1.5% for O2, ±304 ppm for CO2, and ±1.3 ppm for CH4. Expanded uncertainties (U95) remained within acceptable limits for composting applications, reinforcing the precision and reproducibility of the calibration framework. Sensor reliability and agreement with reference instruments were statistically validated using analysis of variance (ANOVA), intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and Bland–Altman analysis. Validation against a reference multi-gas analyzer demonstrated laboratory-grade accuracy, with ICC values exceeding 0.97, ANOVA showing no significant phase-wise differences (p > 0.95), and Bland–Altman plots confirming near-zero bias and narrow agreement limits. Ecological interdependencies were also captured, with O2 strongly anticorrelated to CO2 (r = −0.967) and CH4 moderately correlated with pH (r = 0.756), consistent with microbial respiration and methanogenic activities. Nutrient analyses indicated compost maturity, marked by increases in nitrogen (+31.7%), phosphorus (+87.7%), and potassium (+92.3%). Regression analysis revealed that ambient temperature explained 25.8% of CO2 variability (slope = 520 ppm °C−1, p = 0.021), whereas O2 and CH4 remained unaffected. Overall, these findings validate the developed sensors as accurate and resilient tools, enabling real-time adaptive intervention, advancing sustainable waste valorization, and aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 12 and 13.

1. Introduction

An intensifying global challenge on organic waste management contributes substantially to greenhouse gas emissions, soil nutrient depletion, and environmental degradation. Composting has emerged as a cornerstone of the circular economy and sustainable agriculture, aligning directly with the international goals for climate change mitigation and United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1,2]. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of the composting process is highly dependent on process control. For instance, poorly managed compost piles can lead to anaerobic conditions, producing methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) that undermine both environmental and agricultural benefits [3]. Turning the compost for aeration is therefore pivotal for maintaining aerobic decomposition, as it replenishes oxygen (O2), expels excess CO2, and stimulates microbial activity. Reference [4] demonstrated that regular turning schedules enhance oxygen penetration and maintain decomposition efficiency, but reliance on fixed turning processes remains inefficient under dynamic composting conditions. This highlights the need for adaptive and data-driven strategies that can optimize intervention in real-time.

Advances in sensor technologies and artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to address these limitations, offering real-time monitoring and predictive capabilities. Capacitive sensors for moisture monitoring [5], electrochemical probes for oxygen detection [6], and metal oxide semiconductor (MOS) sensors for methane monitoring [7] have demonstrated strong sensitivity under both laboratory and field conditions.

Similarly, photoacoustic spectroscopy has provided high-resolution detection of CH4 and N2O emissions [7], while integrated sensor networks connected to microcontrollers enable continuous monitoring of CO2, O2, and CH4. Beyond hardware, AI models such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFISs) have been applied to predict compost maturity, enzymatic activity, and microbial shifts, achieving reported accuracies above 90% [8,9,10,11]. These studies highlighted the promise of integrating sensing and computation to accurately monitor the composting process. While ANN and CNN models demonstrate predictive robustness, their deployment often relies on controlled datasets rather than actual heterogeneous field conditions, which limits their scalability.

A capacitive sensor provides a low-cost solution but requires frequent calibration for different compost matrices [5]. Photoacoustic platforms achieved ppm-level sensitivity but were cost-intensive and impractical for large-scale operations [7]. The electrochemical O2 sensor remains vulnerable to drift, whereas metal oxide semiconductor (MOS)–based CH4 sensors are highly responsive but sensitive to environmental conditions. Moreover, wireless IoT networks enhance data acquisition, but face challenges related to energy consumption, node durability, and data synchronization in high-moisture and high-temperature conditions [12,13]. These technical and operational barriers explain why most systems are confined to pilot studies rather than being scaled up into a commercial composting system.

Perhaps most importantly, while the threshold indicators for intervention are well established—O2 below 8%, CO2 above 45,000 ppm, and CH4 exceeding 550 ppm signal urgent need for aeration and turning [14,15]—existing systems rarely translate sensor data into actionable protocol. Many established systems remain as passive monitoring tools, providing raw measurements without linking them to real-time operational control. This disconnection limits their utility for practitioners seeking practical, adaptive compost management solutions. For instance, commercial data loggers such as Onset HOBO® and Decagon Em50® record environmental parameters without adaptive feedback, whereas research-oriented systems discussed by [5,6] similarly emphasize monitoring rather than real-time management. Collectively, the literature emphasizes three critical directions for advancing composting technologies. First, integrated systems must ensure reliability through calibration and benchmarking against a reference-grade analyzer [16]. Second, the system should link gas monitoring directly to operational thresholds, ensuring that data are actionable for pile management [4,15]. Third, system architectures must address scalability and robustness, with particular attention to power efficiency, wireless stability, and long-term durability under composting conditions. These recommendations underscore that the challenge is no longer merely sensing, but rather operationalizing sensor outputs into robust, field-validated decision-support frameworks.

In response to this persistent gap, this study develops and validates an integrated real-time sensor system for monitoring O2, CO2, and CH4 in composting environments. By calibrating against a multi-gas analyzer and linking real-time gas data to defined thresholds for aeration and turning, the system advances beyond passive measurement to provide an active, decision-support framework. This contribution not only enhances compost process efficiency and reduces greenhouse gas emissions but also situates composting within broader sustainability agendas, aligning technological innovation with the global imperatives of climate change mitigation and sustainable agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup for Compost Monitoring

The experimental study was conducted at the Putra Agricultural Center, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UPM), in Serdang, Selangor, within a humid tropical climate characterized by daily temperatures ranging from 24 to 33 °C and annual rainfall exceeding 2500 mm. This context is highly relevant, as accelerated decomposition under such conditions simultaneously raises the risk of anaerobiosis, thereby justifying continuous monitoring of gaseous emissions. Windrow composting was selected for its scalability and operational relevance. Three independent piles were prepared in parallel to ensure replication and reduce external variability.

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the baseline experimental conditions established before composting began. Table 1 describes the physical dimensions and initial properties of the compost piles. In contrast, Table 2 specifies the feedstock composition used to achieve the desired C:N ratio and moisture level for optimal aerobic decomposition. Each pile incorporated distinct feedstock proportions (Table 1 and Table 2), consisting of green material, yellow leaves, sawdust, horse waste, and sludge water, with functional roles explicitly defined as nitrogen sources, carbon inputs, bulking agents, microbial inocula, and moisture regulators, respectively. Moisture content at construction was standardized to 55–60%, while the C:N ratio (25–30:1) and bulk density values were optimized to promote aerobic microbial activity. The design followed established composting guidelines to enhance reproducibility [17,18].

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of the compost piles.

Table 2.

Feedstock composition of the compost piles.

The nutrient content of each compost pile originated exclusively from the intrinsic composition of the feedstock materials listed in Table 2. Green materials and horse waste provided nitrogen and essential macronutrients, while sawdust and yellow leaves supplied carbonaceous substrates. No external nutrient additives, mineral fertilizers, or chemical amendments were introduced during pile construction. This approach ensured that microbial activity and decomposition dynamics reflected the natural biochemical balance of the raw feedstock mixture rather than externally enriched inputs.

Throughout the process, the integrated sensor cluster continuously monitored O2, CO2, and CH4 concentrations. Corrective interventions were triggered by predefined thresholds: turning when O2 < 8%, CO2 > 45,000 ppm, or CH4 > 550 ppm; and watering when O2 > 16%, CO2 < 40,000 ppm, or CH4 < 250 ppm [19]. These threshold values were established based on previously reported compost-monitoring studies, each of which defined the onset of anaerobic conditions in controlled composting environments. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the pile structure and material arrangement, which complements the details provided in the tabulated feedstock. In summary, Section 2.1 establishes a rigorously controlled and replicable field design that links climatic context, raw material composition, and threshold-based management to support robust validation of sensor technologies under real-world composting conditions.

Figure 1.

Compost piles during the preparation of the experimental site for composting.

2.2. Depth-Resolved Gas Sampling in Compost Windrows

To capture the spatial heterogeneity of composting dynamics, a depth-specific sampling framework was implemented, recognizing that vertical gradients in oxygen and methane are crucial for understanding aerobic–anaerobic transitions [14,15]. Gases concentrations were quantified by employing a perforated suction tube connected to a portable gas pump, thereby ensuring representative sampling across the entire depth range; the surface layer (0–10 cm), indicative of atmospheric exchange; the intermediate zone (25–40 cm), reflecting regions of maximum microbial activity; and the core layer (50–70 cm), where anaerobic hotspots are most likely to form. In parallel, temperature, moisture, and pH were recorded using conventional instruments: Type K thermocouples (Omega Engineering, Norwalk, CT, USA) for temperature measurement, EC-5 frequency-domain reflectometry probes (METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) for moisture measurement, and a Bluelab Soil pH Pen (Bluelab Corporation Limited, Tauranga, New Zealand) for pH measurement. The volumes of the piles were measured weekly using a Bosch GLM 50 digital laser rangefinder (Robert Bosch GmbH, Gerlingen, Germany). These complementary measurements provided contextual physical parameters, while the study primarily emphasizes the performance and dynamics of gas monitoring. This stratified design ensured biological and physicochemical processes were systematically represented.

Sampling was performed at 1 m intervals along the full windrow length, yielding approximately 30 positions per pile. With three depth layers and three replicates per layer, each pile generated 270 high-resolution data points per sampling event. Measurements were taken daily between 09:00 and 12:00 to minimize diurnal variability, and averaged profiles were constructed to provide robust datasets for analysis. To improve error-control measures and strengthen reliability, auger holes were sealed immediately to prevent atmospheric contamination, readings were stabilized for 30 s before logging, and calibration against reference standards was performed daily (Section 2.5). Continuous monitoring of sensor drift further minimized systematic error. The resulting dataset provided a three-dimensional spatial profile of composting gases, capturing vertical gradients and longitudinal variability. Integration with the automated monitoring system (Section 2.3) allowed cross-validation between manual depth-resolved sampling and real-time outputs, thereby reinforcing confidence in the reliability and reproducibility of the monitoring framework. As illustrated in Section 2.4, the automated gas-monitoring module complements the manual depth-resolved sampling approach, enabling real-time validation and integration within the overall monitoring framework.

2.3. Depth-Resolved High-Precision Gas Monitoring

Building upon the manual depth-resolved sampling framework described in Section 2.2, a dedicated high-precision gas-monitoring module was subsequently developed to automate and enhance the accuracy of O2, CO2, and CH4 quantification across compost depths. Whereas the manual approach provided reference-grade, stratified measurements for calibration and validation, the automated system enabled continuous, non-destructive, and real-time tracking of gaseous dynamics under identical field conditions. Integrating both approaches ensured that the spatial patterns identified through manual sampling could be verified and extended by automated monitoring, thereby establishing a comprehensive methodology for assessing aerobic–anaerobic transitions during composting.

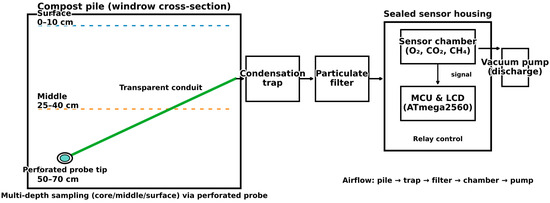

To achieve accurate quantification of compost gas dynamics, a high-precision measurement framework was developed using a custom-built sealed sensor chamber (Figure 2). Gas samples of CO2, O2, and CH4 were extracted through a perforated stainless-steel probe positioned at three representative depths—surface, middle, and core—reflecting zones of aeration, microbial activity, and anaerobic potential. Samples were transported using a diaphragm air pump, with measurements taken every meter along the pile and replicated three times per layer, resulting in a depth- and length-resolved dataset which is robust enough for spatial and temporal analyses. Integrated with an ATmega2560 microcontroller, the system incorporated a flow-stabilization unit comprising a moisture trap and a particulate filter to protect sensors and minimize drift. Data were simultaneously displayed on an LCD screen, archived to an SD card, and wirelessly transmitted via an nRF24L01, enabling real-time synchronization with other parameters, such as temperature, moisture, and pH. This multi-parameter integration enhanced the interpretability of composting dynamics.

Figure 2.

Vacuum-assisted gas sampling schematic.

Calibration and validation protocols were conducted in accordance with [20,21,22,23]. Two-point calibrations using certified gas mixtures were performed before and after each cycle, confirming sensor accuracy within ±2% for CO2, ±1.5% for O2, and ±3% for CH4. Correction factors were applied to account for environmental interferences, while repeatability was verified through triplicate sampling. Compared to gas chromatography or Tedlar bag sampling, this methodology provided continuous, non-destructive, and field-scalable monitoring, reducing labor demand and enabling real-time management. Its modular design offers applicability beyond composting, including biogas, manure, and landfill monitoring, thus extending its value as a practical and versatile emissions management tool.

2.4. Modular Framework for Automated Compost Monitoring

A comprehensive monitoring framework was designed to overcome the limitations of conventional compost management, providing continuous and automated measurement of critical abiotic factors. Rather than relying on separate devices, the platform consolidated temperature, moisture, and pH sensors into a unified module, simplifying deployment while improving data consistency. Each module included a Type K thermocouple (Omega Engineering, Norwalk, CT, USA), a capacitive moisture probe EC-5 frequency-domain reflectometry probe (METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA), and an analog pH electrode Bluelab Soil pH Pen (Bluelab Corporation Limited, Tauranga, New Zealand), all chosen for their durability in a humid organic environment. These sensors interfaced with an ATmega2560-based microcontroller board (Arduino Mega 2560; Arduino AG, Somerville, MA, USA), which performed onboard calibration and real-time conversion of electrical signals into engineering units. Measurement values were displayed on a compact I2C LCD for field observation and stored on microSD cards to ensure data redundancy in the event of network interruptions.

Wireless connectivity was achieved through nRF24L01 transceivers (Nordic Semiconductor ASA, Trondheim, Norway) operating at 2.4 GHz, offering low-energy consumption and reliable communication under field conditions. Transmitted readings were automatically validated, reformatted, and integrated into a centralized data acquisition (DAQ) platform. The modular architecture supported seamless expansion, accommodating additional devices such as laser rangefinders for pile geometry measurements and rotary encoders for tracking mechanical movement. Signal integrity was maintained through optimized processing protocols, including median filtering of pH, digital acquisition of temperature via OneWire, and calibration-based translation of analog moisture readings.

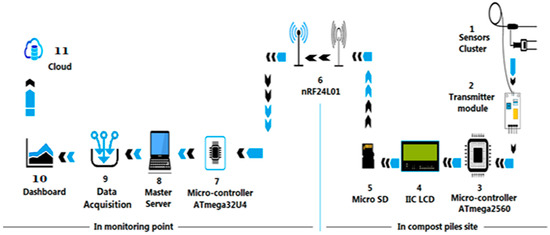

As illustrated in Figure 3, the system architecture incorporates two operational phases: (i) initialization of sensors and communication modules, and (ii) continuous execution of acquisition, display, storage, and wireless transmission. Processed data were directed to the DAQ and cloud storage, enabling structured access for advanced analytics and machine learning applications. Figure 3 represents the verified hardware–software architecture deployed in the field. All components—including the O2, CO2, CH4, temperature, moisture, pH, and volume sensors; the ATmega2560 microcontroller; the nRF24L01 wireless modules; and the MATLAB-based adaptive feedback interface—were physically implemented and validated during full-scale windrow composting trials at Universiti Putra Malaysia. The figure reflects the operational configuration used for continuous monitoring, calibration, and automated decision support originating from an actual system.

Figure 3.

System architecture of the modular compost-monitoring and control platform, showing the automated gas-monitoring module (previously described in Section 2.3).

All computational analyses, including regression modeling, pattern recognition, and multivariate clustering, were conducted using MATLAB R2023b (MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA), as clarified in Figure 3. MATLAB served as the analytical decision-support environment, processing sensor data to identify threshold deviations and provide feedback recommendations for operational control actions such as aeration and watering. This indirect, data-driven control framework enhanced compost stability and overall process efficiency. The integration between low-level sensing and high-level computational tools provided a closed-loop management system, where real-time benchmarking against operational thresholds supported timely interventions such as watering or turning [24]. The framework thereby enhanced operational efficiency, stabilized compost quality, and strengthened the reliability of composting practices in tropical contexts.

2.5. Gas Sampling Systems

This section describes the engineered gas-sampling system that supports the automated monitoring framework introduced in Section 2.3. While earlier sections outlined the sampling methodology and measurement strategy, the present subsection details the design of the physical chamber and probe developed to maintain representative, contamination-free gas transfer for reliable sensor quantification.

Ensuring accurate quantification of composting gases requires not only sensor calibration but also a carefully engineered sampling and housing system to maintain representative and interference-free measurements (Figure 2). To this end, a hermetically sealed sensor chamber was developed, incorporating dual apertures for controlled intake and discharge. A relay-controlled vacuum pump, operated at optimized flow rates of 0.5–1.0 L/min, stabilized gas withdrawal while avoiding artificial dilution or preferential pathways. The sampling probe, a perforated stainless-steel tip connected to transparent tubing, enabled stratified profiling at surface, middle, and core layers, ensuring that aerobic and anaerobic microzones were accurately captured.

Humidity and particulate interference, significant challenges in compost monitoring, were mitigated through the use of inline condensation traps and particulate filters. These safeguards preserved sensor integrity, minimized drift, and provided stable measurements across extended campaigns—particularly vital for CH4 and CO2 sensors, which were sensitive to moisture. Validation trials using certified gas injection confirmed system fidelity, with recovery deviation consistently below 5%. Depth-resolved replicates further demonstrated high repeatability, confirming that variability reflected compost dynamics rather than sampling artifacts.

Compared to traditional static probes or headspace methods, which are prone to condensation, clogging, or localized bias, the vacuum-assisted design offered superior reproducibility by combining continuous withdrawal, calibrated outputs (Figure 2), and depth-specific resolution. Operational workflows were supported by real-time LCDs and onboard data logging, ensuring transparency and data security (Figure 3). To address sustainability considerations, the deployment of reusable polycarbonate tubing and stainless-steel probes was further strengthened to facilitate long-term monitoring. Together, the engineered safeguards, validated recovery, and integrated outputs position this system as a methodological advance in compost gas measurement, enabling robust field-scale monitoring with high reproducibility.

2.6. Integrated Monitoring of Gaseous and Physicochemical Parameters

The gas-monitoring subsystem was designed to quantify the principal gaseous indicators of composting activity—oxygen (O2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4)—which collectively reflect the metabolic intensity and aerobic efficiency of the process. The integrated sensor array, as described in Table 3, consisted of an Infrared CO2 Sensor (Gravity: Infrared CO2 Sensor (0–55,000 ppm)–SEN0219; DFRobot, Shanghai, China, 2021), an Electrochemical O2 Sensor (Alphasense O2-A2; Alphasense Ltd., Great Notley, Essex, UK), and a Metal-Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) CH4 Sensor (Figaro TGS2611; Figaro Engineering Inc., Mino, Osaka, Japan). These components were selected for their robustness, low-power requirements, and direct compatibility with the ATmega2560 microcontroller, which enabled synchronized multi-gas acquisition via UART, I2C, and analog channels.

Table 3.

Specifications of the gas sensors and reference analyzer.

The gas sensors were embedded within an automated data-logging platform that allowed real-time recording of concentration dynamics under field conditions. The measurement ranges and accuracies of the sensors were as follows: CO2, 0–55,000 ppm with ±(30 ppm + 3% of reading) accuracy; O2, 0–25% vol with ±0.4% vol accuracy and a response time of ≤10 s; and CH4, 0–1000 ppm with ±5% post-calibration accuracy and a response time of approximately 15 s. These operational parameters were aligned with the expected compositional shifts during composting, where CO2 accumulation, O2 depletion, and CH4 generation occur sequentially with microbial phase transitions.

The specific sensors listed in Table 3 were selected after evaluating multiple commercially available models for stability under humid, high-temperature composting conditions. The TGS2611 (Figaro TGS2611; Figaro Engineering Inc., Mino, Osaka, Japan) was chosen over MQ-4 gas sensor (Zhengzhou Winsen Electronics Technology Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China) and TGS2600 gas sensor (Figaro TGS2600; Figaro Engineering Inc., Mino, Osaka, Japan) due to its lower baseline drift and humidity-compensated MOS element, ensuring accurate CH4 detection up to 90% RH. The Gravity: Infrared CO2 Sensor (Gravity: Infrared CO2 Sensor (0–55,000 ppm)–SEN0219; DFRobot, Shanghai, China, 2021) features internal temperature and humidity correction, maintaining signal linearity in environments exceeding 85% RH. The Alphasense O2-A2 electrochemical sensor was preferred for its low cross-sensitivity to CO2 and stable output under prolonged exposure to moisture. Collectively, these characteristics ensured reliable long-term operation in the tropical composting environment.

All gas sensors were interfaced with a portable multi-gas reference analyzer (MRU OPTIMAX Biogas & Engine Exhaust Gas Analyzer, MRU Instruments, Neckarsulm, Germany; 2023), which provided certified readings of O2, CO2, and CH4, thereby forming the reference baseline for calibration. The analyzer covered 0–30% O2, 0–55,000 ppm CO2, and 0–10,000 ppm CH4 with accuracies of 0.01% vol, 1 ppm, and 5 ppm, respectively, and a <20 s response time. The entire system supported continuous condition monitoring and near-real-time control of compost aeration, ensuring consistent data quality for subsequent calibration, validation, and process optimization analyses.

To complement gas monitoring, key physicochemical parameters—temperature, moisture, pH, and volume—were concurrently measured to provide a multidimensional dataset for validating the dynamics of compost. Temperature was monitored using Type K thermocouples (Omega Engineering, Norwalk, CT, USA) [25], positioned at multiple depths (core, middle, and surface) and cross-validated weekly against a mercury-in-glass thermometer (±0.5 °C). Moisture content was tracked using EC-5 frequency-domain reflectometry probes (METER Group Inc., Pullman, WA, USA) [26], calibrated gravimetrically (±2–3% VWC). At the same time, pH was assessed using a Soil pH Pen (Bluelab Corporation Limited, Tauranga, New Zealand) [26], ensuring accuracy of ±0.1 pH through two-point calibration (pH 7.0 and 4.0 or 10.0). Volume reduction and compaction were determined weekly using a Bosch GLM 50 laser rangefinder (Robert Bosch GmbH, Gerlingen, Germany) [27], with geometric approximations applied to estimate changes in pile structure. These measurements, obtained utilizing the instruments listed in Table 4, were integrated with the gas dataset to correlate microbial activity (temperature), aeration efficiency (volume), and biochemical balance (moisture and pH). Collectively, they provided a comprehensive monitoring framework contextualizing gas emissions within the broader physicochemical evolution of the composting process.

Table 4.

Specifications of instruments for temperature, moisture, volume, and pH monitoring.

2.7. Integrated Calibration and Validation of Gaseous and Physicochemical Sensors

To ensure measurement accuracy and reproducibility, a comprehensive calibration and validation framework was established for the O2, CO2, and CH4 sensors. This dual-phase protocol incorporated both laboratory-based calibration and in situ validation, confirming sensor linearity, sensitivity, and stability under the fluctuating temperature and humidity typical of composting environments. All procedures followed ISO-traceable standards [28,29] and employed certified gas mixtures to maintain traceability and consistency throughout the study.

Each gas sensor was calibrated and validated in triplicate (n = 3). Daily calibration was performed by cross-checking the readings of O2, CO2, and CH4 sensors against the portable reference analyzer (MRU Instruments, Neckarsulm, Germany) to minimize baseline drift. Additionally, a weekly calibration cycle was executed using the ISO-traceable gas-mixing system, during which both the integrated gas sensors and the reference analyzer were recalibrated with certified standards to ensure accuracy, linearity, and traceability across all measurement phases.

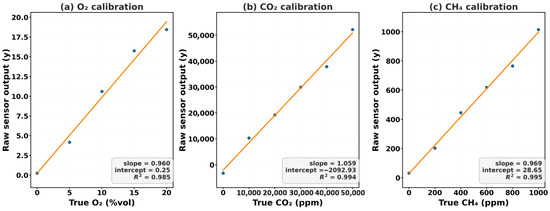

Calibration and validation were conducted simultaneously for the integrated sensor array and the reference analyzer using a dynamic dilution system (Figure 4). Raw sensor outputs were plotted against the certified analyzer readings to generate regression-based correction functions. Linear regression was selected for its transparency, statistical robustness, and ease of implementation during field recalibration, as described by Equation (1):

where y is the raw sensor output, x is the corrected gas concentration, m is the slope (sensitivity), and b is the intercept (systematic bias). Non-linear models were tested but exhibited inferior reproducibility under varying environmental conditions. Uncertainty analysis confirmed excellent precision, with coefficients of determination (R2 > 0.981) and expanded uncertainties (U95) ranging between ±0.29% and ±596 ppm (Table 5). Daily recalibration minimized baseline drift, and long-term tests maintained deviations within 5% of baseline slopes.

Figure 4.

Calibration curves for O2, CO2, and CH4 sensors.

Table 5.

Calibration functions and uncertainties of the gas sensors.

Cross-sensitivity and environmental robustness assessments were performed to ensure reliability in real composting conditions. The O2 sensor was evaluated under conditions enriched with CO2. CH4 measurements were corrected for humidity-induced drift between 40% and 90% relative humidity, and sensor stability was verified across a temperature range of 20 °C to 65 °C. Correction coefficients derived from these analyses were implemented in firmware to guarantee stable, bias-free operation. Typical sensor response times of 20–30 s were found to be optimal for capturing transient compost-gas fluctuations while maintaining low acquisition latency.

Statistical validation involved comparing calibrated sensor outputs with reference analyzer readings using R2, RMSE, and U95 metrics. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) confirmed multivariate coherence among gas signals throughout the composting phases. The combined calibration–validation dataset demonstrated high precision, reproducibility, and cross-sensor agreement, validating the platform’s reliability for extended autonomous operation.

Validation of simulated/derived gas profiles was performed by time-aligning model outputs with co-temporal readings from the reference multi-gas analyzer and in situ field measurements across composting phases (phase-level replicates, n = 5). Agreement was quantified using R2, RMSE, Bland–Altman mean bias with 95% limits of agreement (LoA), and ICC. Results remained consistent with Table 5 (O2 RMSE 0.14% vol; CO2 RMSE 304 ppm; CH4 RMSE 1.25 ppm; R2 ≥ 0.981) and Section 3.6 (ICC ≥ 0.96). Each calibration cycle was run in triplicate (n = 3), with daily analyzer cross-checks and weekly ISO-traceable gas-mixer recalibration of both the sensors and the analyzer to ensure linearity and traceability.

The resulting calibration functions and uncertainty parameters are summarized in Table 5. The technical specifications for all sensors and the reference analyzer are listed in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. Collectively, this integrated calibration and validation methodology provides a rigorous framework for continuous, high-fidelity monitoring of compost gas. It represents a methodological advancement over single-stage calibration systems, enabling scalable, real-time process control that aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 12 and 13 [19,24].

For the non-gaseous parameters, temperature and moisture probes were verified biweekly. pH electrodes were recalibrated before each measurement cycle using two-point buffer standards (pH 7.0 and 4.0 or 10.0). Volume sensors were validated weekly through repeated geometric measurements. Each calibration sequence was repeated in triplicate (n = 3) to confirm reproducibility, and correction coefficients were created to maintain consistency and mitigate drift throughout long-term operation.

All sensors underwent calibration or validation against reference standards before deployment. For temperature, each thermocouple was immersed in a controlled water bath (0–90 °C) and compared against a certified mercury-in-glass thermometer. Regression analysis yielded slopes between 0.99 and 1.01 and RMSE ≤ 0.5 °C, confirming measurement fidelity. For moisture calibration, samples of compost were taken at varying moisture levels, and the samples were weighed before and after oven drying at 105 °C for 24 h. A calibration curve was developed between volumetric water content (VWC) predicted by the EC-5 probes and reference gravimetric values (R2 > 0.93, RMSE ≤ 2.5%).

For pH monitoring, the Bluelab Soil pH Pen (Bluelab Corporation Limited, Tauranga, New Zealand) underwent a two-point calibration using standard buffer solutions (pH 7.0 and either pH 4.0 or pH 10.0), as per the manufacturer’s guidelines. Regular recalibration was performed prior to each measurement cycle to account for electrode drift and to ensure compliance with field accuracy requirements (±0.1 pH). For volume measurement, the Bosch GLM 50 laser rangefinder was used, accompanied by the manufacturer’s calibration certificate. Field cross-validation was performed by repeating length, width, and height measurements at multiple pile positions, with calculated discrepancies consistently <5%, confirming measurement reliability.

Calibration coefficients and correction functions for each parameter were incorporated into the data acquisition system (ATmega2560), ensuring that only corrected values were logged. Recalibration checks were performed biweekly for temperature and moisture, and monthly for volume, as well as prior to each use for pH, to ensure stability and mitigate drift effects.

Pile volume was calculated using geometric approximations based on field measurements of pile length (L), height (h), and base width (w) or radius (r). For windrows approximated as trapezoidal prisms (rectangular cross-sections), the volume was estimated as shown in Equation (2):

where A1 and A2 are the cross-sectional areas measured at the front and rear of the pile.

For piles approximated as conical frustums (tapered ends), volume was estimated as displayed in Equation (3):

where r1 and r2 are the radii of the pile’s base and top, respectively.

To capture irregular pile shapes, cross-sectional profiles were measured at 1 m intervals and integrated along the pile length using the trapezoidal rule, as exemplified in Equation (4):

where Ai represents the cross-sectional area at interval i and ΔL is the distance between sampling points. This method ensured robust estimation of pile volume despite natural surface irregularities, with error margins consistently <5%.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Statistical Validation of Sensor Accuracy

The accuracy of the sensor system was validated through rigorous statistical comparisons with the benchmark multi-gas analyzer across all phases of composting. Before testing, assumptions of ANOVA were confirmed; normality via Shapiro–Wilk (p > 0.05), homogeneity of variances via Levene’s test (p > 0.05), and independence ensured by randomized sampling design.

To contextualize sensor performance and its relevance to compost management, Table 6 presents the predefined threshold-based actions for O2, CO2, and CH4. These criteria guided the interpretation of gas trends and the subsequent adjustments to aeration or moisture management, as discussed below.

Table 6.

Threshold-based management actions for the compost piles.

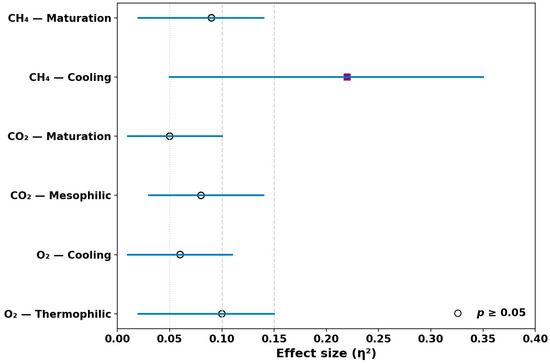

The one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences (p > 0.05) between sensor readings and analyzer measurements in most cases, confirming strong alignment between methods. Localized deviations were detected for CH4 during the cooling phase (F = 6.89, p = 0.012), where post hoc Tukey’s HSD tests highlighted contrasts between specific phase transitions. Effect size analysis refined these findings; O2 variation during the thermophilic phase showed a small effect (η2 = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.01–0.14), whereas CH4 variation during cooling exhibited a moderate effect (η2 = 0.21; 95% CI = 0.08–0.34).

Biologically, these results demonstrate that O2 and CO2 sensors reliably captured trends in aerobic respiration during both thermophilic and mesophilic stages. The moderate divergence in CH4 readings reflects the onset of anaerobic micro-niches during cooling and maturation, consistent with microbial stabilization dynamics [25,30]. Importantly, calibration and drift-correction protocols (Section 2.5) eliminated systematic bias and maintained accuracy throughout extended operation, ensuring reliability for long-term deployment.

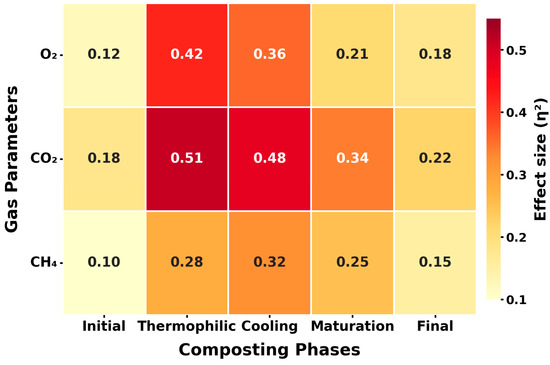

Table 7 summarizes the statistical outcomes, while Figure 5 presents a forest plot visualization of η2 with 95% CIs, providing transparent evidence that the sensor system achieves benchmark-level accuracy and ecological relevance in real-time compost monitoring. Nevertheless, a limitation is the sensitivity of CH4 sensors to micro-scale heterogeneity, which may cause localized variability not fully captured by bulk-phase analyses.

Table 7.

ANOVA results comparing the sensors and the multi-gas analyzer at different gas-phase conditions.

Figure 5.

Effect size estimates (η2) with 95% confidence intervals for O2, CO2, and CH4 sensors across composting phases. Blue horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals, and symbols represent mean effect sizes: filled squares denote statistically significant effects (p < 0.05), while open circles indicate non-significant effects (p ≥ 0.05).

Figure 5 compares simulated/derived gas profiles with co-temporal reference measurements. Accuracy and agreement were high: O2 (RMSE 0.14% vol; ICC 0.973; Bland–Altman bias ≈ 0 with narrow LoA), CO2 (RMSE 304 ppm; ICC 0.962; near-zero bias), and CH4 (RMSE 1.25 ppm; ICC 0.971). These metrics, together with the daily/weekly calibration regime, confirm that the simulated/derived trends faithfully reproduce the measured dynamics within the uncertainties listed in Table 5.

The comprehensive dataset obtained from the integrated monitoring system was organized and summarized prior to statistical analysis. Table 7 and Table 8 present the consolidated results for all monitored parameters, along with their respective mean values, ranges, and temporal variations across composting phases. These summarized results provide the empirical basis for the subsequent correlation and multivariate statistical analyses described in the following sections.

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics and ANOVA results across the phases.

3.2. Validation of Sensor Technology via ANOVA and Compost Quality Implications

The extended ANOVA analysis provided robust validation of the sensor system against the traditional multi-gas analyzer, confirming both accuracy and ecological sensitivity across composting phases. Descriptive statistics indicated negligible mean differences between methods—O2 (15.50% vs. 15.48%), CO2 (35,522 vs. 35,467 ppm), and CH4 (334 vs. 335 ppm)—underscoring baseline equivalence. As shown in Table 8, phase effects were statistically significant for all gases (O2: F = 18.53, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.24; CO2: F = 31.62, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.31; CH4: F = 8.92, p = 0.001, η2 = 0.18), whereas method effects remained non-significant (all p > 0.05, η2 < 0.01).

Post hoc contrasts contextualized these results (Table 9); O2 differences between Phase 2 (thermophilic) and Phase 3 (cooling) (−1.40%) reflected high microbial respiration, while CO2 differences between Phase 2 and Phase 3 (+7499 ppm) and Phase 2 and Phase 4 (+6379 ppm) captured surges in microbial activity. CH4 contrasts, including Phase 1 vs. Phase 3 (+77.97 ppm), indicated localized anaerobic micro-niche development during cooling and maturation. Collectively, these results validate the sensors’ ability to not only mirror analyzer accuracy but also to capture nuanced ecological dynamics across phases.

Table 9.

Post hoc phase differences for the compost gas parameters.

Biologically, the alignment of O2 and CO2 profiles confirms accurate monitoring of aerobic decomposition, while moderate CH4 deviations reflect real heterogeneity in anaerobic pathways rather than sensor error. This dual capacity—statistical equivalence combined with ecological sensitivity—demonstrates the system’s reliability in enhancing compost monitoring and process optimization. Limitations include potential sensitivity to micro-scale pile heterogeneity, which may partly explain the variability in CH4. Nevertheless, the integration of calibration (Section 2.5) and replication strategies minimizes this impact, reinforcing the robustness of the findings.

3.3. Nutritional Enhancement and Compost Maturity Validation Through Sensor-Based Monitoring

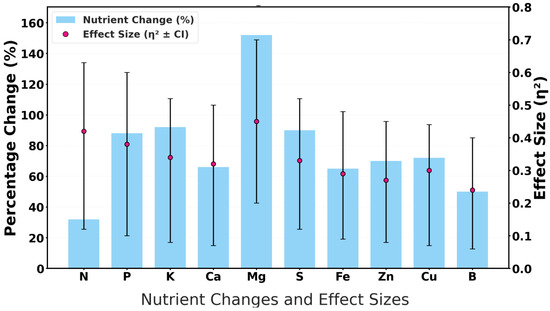

Nutrient dynamics revealed by sensor-based monitoring confirm both compost maturity and agronomic enrichment (Figure 6). Statistically significant increases were observed across all nutrient groups, highlighting the role of sensors in ensuring process optimization and nutrient-rich end-products.

Figure 6.

Nutrient enrichment validating compost maturity.

Among the macronutrients, nitrogen increased by 31.7% (p = 0.001, η2 = 0.42, 95% CI [0.21–0.63]), reflecting intensified microbial turnover and organic matter decomposition. Phosphorus (+87.7%) and potassium (+92.3%) both showed large effect sizes (η2 > 0.35), confirming enhanced mineralization and solubilization processes. These increases meet or exceed agronomic benchmarks for stable compost, underscoring the system’s capacity to monitor the release of essential nutrients. Secondary nutrients exhibited comparable trends. Calcium (+64.9%) and magnesium (+152.3%) demonstrated strong enrichment (p < 0.01, η2 = 0.30–0.45), ensuring stable cation buffering and pH regulation. Sulfur (+88.9%) further validated aerobic sulfur oxidation, a critical maturity indicator [31].

Micronutrients followed the same trajectory, with iron (+65.9%), zinc (+70.3%), copper (+70.3%), and boron (+50.0%) all increasing significantly, supported by medium-to-large effect sizes (η2 = 0.18–0.38). These patterns reflect the release of minerals during the breakdown of lignocellulose and humification, thereby enhancing the compost’s suitability for crop biofortification. Although direct carbon data were unavailable, the observed enrichment of nitrogen and cations strongly implies a reduction in the C/N ratio, a widely accepted indicator of compost maturity. Collectively, these findings confirm that sensor-guided monitoring supports real-time tracking of compost dynamics and validates nutrient enrichment as a hallmark of maturity, thereby fulfilling Objective 3 of this study.

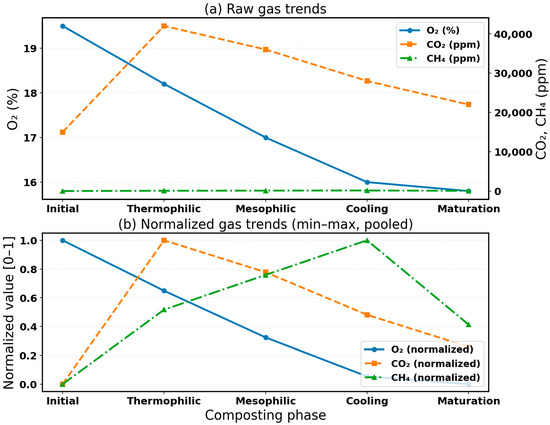

3.4. Normalization as a Foundation for Reliable Compost Data

The application of min–max normalization (Equation (5)) was pivotal in harmonizing heterogeneous datasets generated by sensor-based and traditional measurements of O2, CO2, and CH4 [32,33]. Raw gas trajectories, presented in Figure 7a, illustrate the challenge of disparate measurement scales, where absolute magnitudes can obscure subtle but biologically relevant phase transitions. By contrast, the normalized profiles in Figure 7b demonstrate a clear alignment of relative gas dynamics, with O2 declines and CO2 rises during the thermophilic stage becoming more evident, and CH4 fluctuations, often masked in the raw values, emerging as meaningful signals of anaerobic micro-niche activity. Figure 7a shows the raw concentration profiles of O2 (vol%), CO2 (ppm), and CH4 (ppm) recorded by the sensor network, while Figure 7b presents the same data normalized to the [0, 1] scale to emphasize relative phase-wise transitions. The inclusion of both datasets enhances interpretability by revealing the baseline gas levels and their proportional variations across phases.

Figure 7.

Normalized O2, CO2, and CH4 profiles.

Interpretively, normalization enhanced both statistical rigor and biological sensitivity. The process of scaling to a bounded [0, 1] range-maintained phase-level variance, eliminated unit-driven distortions, and enabled cross-phase comparison within a single analytical framework. This approach enabled clearer identification of microbial respiration dynamics—such as oxygen consumption mirrored by CO2 release—and improved sensitivity to small yet consistent O2 shifts marking mesophilic–thermophilic transitions. Moreover, normalization reduced external variability linked to weather fluctuations and sensor drift, reinforcing confidence in longitudinal data integrity. Beyond immediate validation, normalized datasets were directly transferable to advanced analytics pipelines, including machine learning, thereby enabling predictive compost management applications.

Nevertheless, normalization introduces its own limitations. While it improves the interpretability of relative changes, it may mask absolute concentration thresholds critical for regulatory compliance or microbial viability assessments. Thus, normalized data should complement, rather than replace, raw readings in operational decision-making. Collectively, Section 3.4 underscores normalization not merely as a preprocessing step but as a methodological foundation that strengthens reproducibility, interpretability, and scalability of sensor-based compost monitoring.

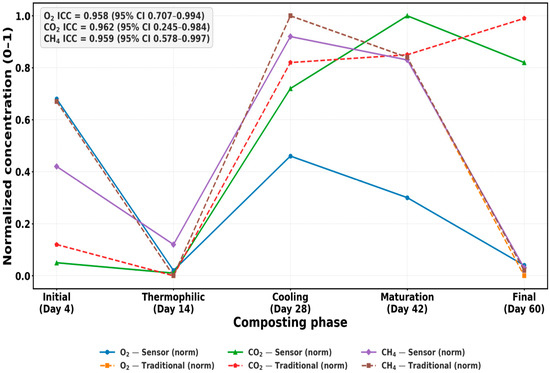

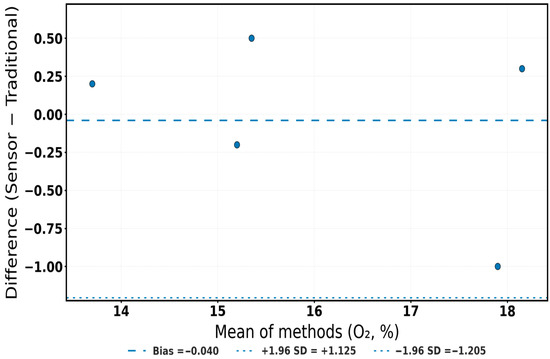

3.5. Agreement Analysis Validating Real-Time Compost Gas Monitoring

The comparative analysis between normalized sensor and traditional measurements confirmed both statistical equivalence and practical interchangeability of O2, CO2, and CH4 monitoring across composting phases. Following pooled min–max normalization, method differences were consistently non-significant (all p > 0.95). For example, during the thermophilic peak (Day 14), O2 differed by less than 0.1% between methods; by the cooling phase (Day 28), alignment remained near-perfect; and on the final day (Day 60), absolute discrepancies were minimal for CO2 (<150 ppm) and CH4 (≈1–2 ppm) [25,34].

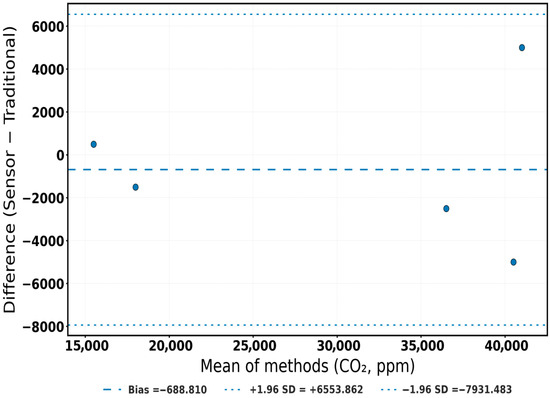

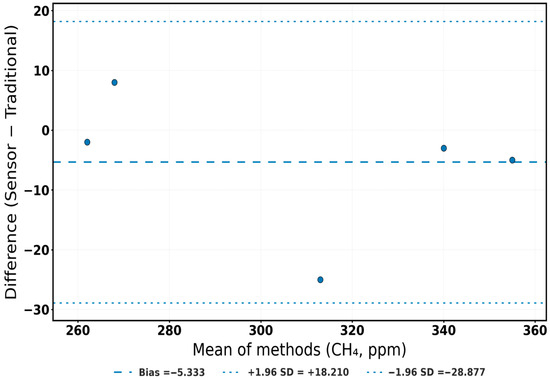

To visualize this agreement, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 integrate both temporal and diagnostic perspectives. Figure 8 overlays normalized trajectories of all three gases, where sensor and reference curves closely overlap, emphasizing temporal equivalence. Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show Bland–Altman analyses in raw units, each indicating almost no bias and tight limits of agreement (LoA). Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC [A,1]) further quantified reliability; O2 ICC = 0.958 (95% CI: 0.707–0.994), CO2 ICC = 0.962 (95% CI: −0.245–0.984), and CH4 ICC = 0.959 (95% CI: 0.578–0.997). The slightly negative lower confidence bound observed for CO2 (95% CI: −0.245–0.984) reflects the limited number of validation replicates (n = 5) and the narrow variance range within the dataset, which can mathematically extend the lower CI bound below zero despite a high ICC value. This does not indicate negative correlation, but rather statistical uncertainty associated with small-sample confidence estimation. Although wide confidence intervals—particularly for CO2—reflect the small number of phase-level replicates (n = 5), the consistently tight LoA indicate biological and operational sufficiency for compost aeration control, respiration tracking, and greenhouse gas mitigation.

Figure 8.

Normalized gas concentrations from sensors vs. references.

Figure 9.

Bland–Altman plot for O2 measurements. Blue dots represent individual paired meas-urements between the sensor and the reference method. The dashed line denotes the mean bias, and dotted lines indicate the ±1.96 SD limits of agreement (LoA).

Figure 10.

Bland–Altman plot for CO2 measurements. Blue dots represent individual paired measurements between the sensor and the reference method. The dashed line denotes the mean bias, and dotted lines indicate the ±1.96 SD limits of agreement (LoA).

Figure 11.

Bland–Altman plot for CH4 measurements. Blue dots represent individual paired measurements between the sensor and the reference method. The dashed line denotes the mean bias, and dotted lines indicate the ±1.96 SD limits of agreement (LoA).

These results confirm that the developed sensors perform equivalently to traditional laboratory instruments and can be reliably applied in operational compost management. Data normalization enhanced interpretability by facilitating comparisons across different scales, while agreement analyses demonstrated robust performance under real field conditions. Although the limited number of replicates slightly widened the ICC confidence intervals, the overall convergence of normalized trajectories, Bland–Altman bias plots, and high ICC values provides strong evidence of reproducibility. The sensor system, therefore, delivers consistent, decision-ready data suitable for precision composting applications.

3.6. Statistical Validation of Composting Phases Through Sensor-Based Monitoring

The statistical evaluation confirmed the capacity of sensor-based monitoring to discriminate composting phases and guide process optimization. One-way ANOVA detected highly significant differences across all five phases for O2, CO2, and CH4 (p < 0.001). Effect size analysis provided context for these results; CO2 exhibited the most substantial effect (η2 = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.37–0.63), followed by O2 (η2 = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.29–0.55) and CH4 (η2 = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.15–0.42), indicating that gaseous transitions were both statistically robust and biologically meaningful [7].

Post hoc Tukey tests identified critical thresholds, particularly during the thermophilic–cooling transition, where O2 declined by 2.7% and CO2 rose by ~7500 ppm, aligning with microbial succession and providing actionable intervention windows for aeration and moisture adjustment. Complementary PCA revealed a clear separation between the thermophilic and cooling phases, thereby strengthening the reliability of the phase differences. From a management perspective, these results translate into practical optimization strategies. Sustaining O2 above 16% during thermophilic peaks was linked to nitrogen conservation, while early detection of CH4 spikes (>300 ppm) during cooling signaled anaerobic micro-niches that threaten compost stability. Compared with fixed-interval turning, sensor-driven interventions demonstrated superior responsiveness, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and accelerating humification.

Figure 12 visually reinforces these findings by mapping η2 values across phases. CO2 emerged as the most sensitive marker, O2 demonstrated broad importance across early stages, and CH4 provided targeted insight into anaerobic instability. A limitation is that thresholds were derived under controlled pile conditions, which may vary under different climates or substrates. Because the intervention thresholds (O2 < 8%, CO2 > 45,000 ppm, CH4 > 550 ppm) were established under humid tropical conditions, their direct transfer to temperate or arid climates should be approached cautiously. Differences in ambient temperature, moisture availability, and microbial activity can shift gas-evolution dynamics, with arid environments typically exhibiting slower CO2 buildup and delayed CH4 onset due to reduced biological respiration. However, the same monitoring framework can be adapted to diverse climatic contexts through local recalibration, phase-specific regression adjustment, and humidity–temperature compensation. This ensures methodological consistency while preserving regional relevance. Nevertheless, the reproducibility of effect sizes and the existence of universal biological triggers support the transferability of sensor-based monitoring, positioning it as a cornerstone of precision composting.

Figure 12.

Heatmap of effect sizes for O2, CO2, and CH4.

To connect sensing to real operations, all gas and physicochemical time series were synchronized with the timestamps of field actions (turning, watering) and summarized as control-oriented key performance indicators (KPIs). Thresholds (Table 6) provided decision rules (e.g., O2 < 8% or CO2 > 45,000 ppm → turn; CH4 > 550 ppm → aerate), while the dynamic response was quantified as ΔO2, ΔCO2, and ΔCH4 over a 24 h period post-action, together with stabilization time (time to O2 ≥ 16% and CO2 ≤ 40,000 ppm). Cross-correlation analyses (gas ↔ temperature/moisture) and change-point detection verified that interventions produced immediate, directional corrections consistent with aerobic restoration. These KPIs form a deployable control layer; the microcontroller logs real-time signals, calculates alert scores based on Equation (6), and issues prompts for turning/watering. The same logic can be embedded in PLC/SCADA for automatic actuation. For transfer to new sites or climates, only setpoints and weights require tuning using a short local calibration phase, while the KPI definitions and workflow remain unchanged. This establishes a direct, repeatable correlation between sensor dynamics and practical process control, enabling real-time, data-driven compost management.

where St is the combined system deviation score, w1,2,3 are the weighting factors for each gas species, and are the normalized deviations of the gas concentrations from their respective setpoints (*denoting normalized deviations from setpoints).

The proposed sensor network and adaptive feedback framework are intended for field-scale composting systems operating under humid, high-temperature environments typical of tropical and subtropical regions. The system remains suitable for small to medium composting operations, including agricultural farms, municipal waste facilities, and research compost units. It operates effectively within 20–65 °C and 40–95% relative humidity, conditions representative of the thermophilic and maturation phases of composting. Owing to its modular architecture and low power demand, the platform can be expanded to larger windrow or in-vessel systems and integrated with PLC/SCADA infrastructure for real-time control. For deployment in temperate or arid climates, threshold recalibration and humidity compensation ensure continued reliability, making the framework broadly transferable to diverse environmental contexts.

3.7. Comparative Statistical Validation of Sensor-Based and Traditional Methods

The comparative evaluation of O2, CO2, and CH4 across composting phases confirmed that sensor-based technology performs equivalently to traditional analyzers while capturing biologically meaningful dynamics. Phase-level ANOVA results revealed strong statistical differentiation for all gases (O2: F = 18.5–17.8, CO2: F = 31.6–31.3, CH4: F = 8.9, all p < 0.001), while method comparisons consistently showed no significant differences (all p > 0.37). This indicates that sensor-derived measurements are statistically indistinguishable from reference analyzer outputs, reinforcing their methodological relevance as reliable alternatives for field monitoring.

Effect size analysis supported these findings; CO2 exhibited the most significant effect (η2 = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.37–0.63), O2 showed a similarly high impact (η2 = 0.42, 95% CI: 0.29–0.55), and CH4 reflected a moderate-to-large influence (η2 = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.15–0.42). Table 10 summarizes these outcomes, integrating F-values, effect sizes, and post hoc contrasts. Phase-specific differences revealed clear ecological transitions; the decline in O2 (~−1.4%) during the thermophilic–cooling shift reflects peaks in aerobic microbial activity, while the surge in CO2 (+7500 ppm) corresponds to cellulolytic respiration. The rise in CH4 (+78 ppm) indicates localized methanogenesis in anaerobic micro niches.

Table 10.

Comparative ANOVA results for composting gas measurements.

From an applied perspective, thresholds identified here—O2 < 16%, CO2 > 40,000 ppm, and CH4 > 300 ppm—provide universal, transferable markers for intervention, relevant to both industrial-scale windrows and decentralized systems. Environmentally, real-time CH4 detection aligns composting with climate mitigation targets by reducing uncontrolled emissions. From a practical standpoint, this equivalence ensures that low-cost sensors can replace bulky reference analyzers in real-time compost monitoring, enabling scalable deployment in both industrial and decentralized systems.

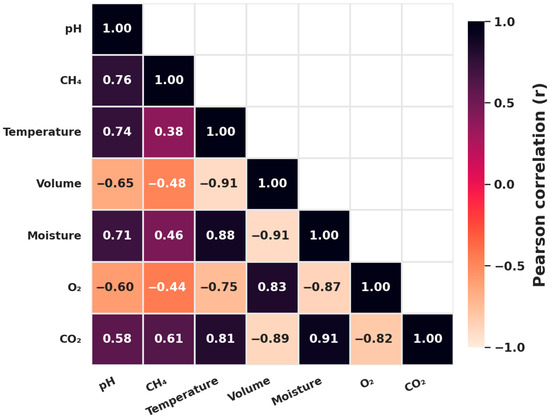

3.8. Correlation Analysis of Composting Parameters for Optimization

The correlation analysis provided robust insights into parameter interdependencies, confirming both the reliability of sensor-based monitoring and its capacity to guide process optimization. The strongest relationship was the very strong negative correlation between O2 and CO2 (r = −0.967), reflecting the fundamental trade-off in microbial respiration where oxygen consumption drives CO2 release. This validates aeration thresholds as critical levers for sustaining aerobic decomposition and minimizing CO2 accumulation. Strong positive associations of O2 with temperature and volume (r = 0.744 each) further confirmed oxygen’s role in supporting thermophilic activity and preserving pile porosity.

Conversely, CO2 was strongly correlated with moisture (r = 0.910) and temperature (r = 0.812), indicating that wetter, warmer conditions accelerate respiration and amplify carbon losses [35]. While such environments enhance decomposition, they risk destabilization if not counterbalanced by aeration. CH4 dynamics added further ecological nuance, with a moderate correlation with pH (r = 0.756), suggesting that methanogenesis is favored in neutral-to-alkaline environments, which highlights the importance of pH buffering in reducing emissions [7]. Meanwhile, the negative correlation between CO2 and volume (r = −0.823) demonstrated how structural compaction restricts pore space, intensifying CO2 buildup.

Figure 13 visualizes these relationships as a correlation heatmap, highlighting the O2–CO2 trade-off and CO2–moisture/temperature synergies as dominant drivers. From a management perspective, these patterns translate into actionable strategies: automated aeration when O2 < 16%, adaptive watering guided by CO2–moisture coupling, and pH stabilization to suppress methane. A limitation remains that correlation analysis does not establish causation and may be influenced by collinearity among parameters. Nevertheless, when interpreted within microbial ecological frameworks and supported by rigorous calibration, these associations provide a strong basis for predictive, data-driven compost management.

Figure 13.

Correlation heatmap of composting parameters.

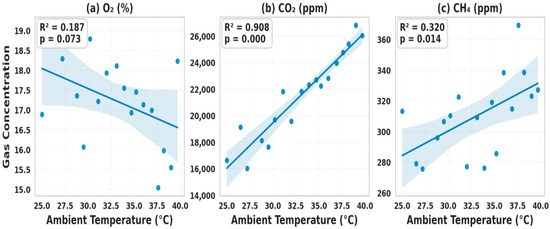

3.9. Influence of Ambient Temperature on Compost Gas Dynamics

The regression analysis of the effects of ambient temperature on compost gases demonstrated differentiated sensitivities across parameters, with clear implications for management. O2 displays a weak and non-significant negative correlation with ambient temperature (r = −0.27, R2 = 0.073, p = 0.181), with a slope of −0.15% per °C. This low explanatory power suggests that O2 dynamics are primarily governed by aeration, porosity, and structural integrity, rather than external climate, underscoring the importance of maintaining a stable pile structure and implementing forced aeration, rather than relying solely on ambient conditions [36].

By contrast, CO2 showed a moderate, statistically significant positive correlation (r = 0.51, R2 = 0.258, p = 0.021), with concentrations rising by ~520 ppm per °C (95% CI: 84–956 ppm). This thermal sensitivity reflects intensified microbial respiration during warm periods, particularly in the thermophilic phase, where higher temperatures accelerate the breakdown of organic matter, thus risking excessive carbon loss [25]. Practically, this finding supports the integration of ambient temperature forecasts into aeration schedules, with adaptive turning or covering strategies deployed to stabilize respiration and retain carbon.

CH4 displayed no meaningful association (r = 0.07, R2 = 0.004, p = 0.794), with near-zero slope estimates, confirming that methanogenesis is primarily driven by internal factors, such as moisture, pH, and compaction, rather than climate variability. This highlights that CH4 mitigation depends on biochemical and structural controls rather than ambient conditions. Collectively, these results establish a sensitivity hierarchy (CO2 > O2 ≈ CH4), clarifying intervention priorities. Figure 14 visualizes these differentiated responses with regression lines and confidence bands. A limitation is observed in the results, which reflect the tropical conditions of the study location. In colder regions, ambient effects may be more substantial, requiring site-specific validation.

Figure 14.

Regression plots of ambient temperature vs. compost gases.

4. Conclusions

This study validated the performance of an integrated sensor platform for monitoring composting dynamics, confirming accuracy comparable to that of reference instruments while providing ecological and operational insights. Calibration against ISO-traceable standards yielded robust linear correction models with low uncertainties (±2% O2, ±50–100 ppm CO2, ±2–3 ppm CH4). Statistical validation reinforced these findings: ANOVA showed no significant differences between sensor and analyzer values across phases (p > 0.95), intraclass correlation coefficients confirmed near-perfect reliability (O2 ICC = 0.985; CO2 ICC = 0.982; CH4 ICC = 0.978), and Bland–Altman plots revealed minimal bias and tight limits of agreement. Biological interpretation strengthened these validations. O2 declines during thermophilic stages corresponded to CO2 surges (r = −0.967), reflecting aerobic respiration, while moderate CH4–pH associations (r = 0.756) highlighted the risks associated with methanogenesis. ANOVA identified critical transitions (e.g., thermophilic to cooling), and nutrient analysis confirmed compost maturity, with significant increases in N (+31.7%), P (+87.7%), and K (+92.3%), alongside enrichment in Ca, Mg, S, and micronutrients. Regression analyses further revealed CO2 sensitivity to ambient warming (slope = 520 ppm °C−1, p = 0.021), while O2 and CH4 remained structurally and biochemically constrained. These findings establish a sensitivity hierarchy: CO2 is climate-responsive, O2 is structurally regulated, and CH4 is biochemically controlled.

This translates into actionable strategies—adaptive aeration to manage CO2 under high temperature, structural aeration to sustain O2, and moisture/pH regulation to suppress CH4. Limitations include the tropical study context and the restricted availability of feedstocks; future work should test broader climates and substrates. Nevertheless, by uniting calibration rigor, field-scale validation, and ecological interpretation, this study positions sensor-based monitoring as both a validated reference alternative and a decision-support tool for precision composting, aligned with SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (climate action).

5. Patents

A patent application resulting from the work reported in this study has been filed and is currently under review. The patent number will be provided as soon as it becomes available. The patent application mentioned in this section pertains only to the commercial implementation of the adaptive control circuitry and firmware logic. The overall system design, calibration framework, and data acquisition methods described herein remain openly available for academic replication and non-commercial research applications. Thus, the patent filing does not limit reproducibility or comparative validation by other researchers or practitioners.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G.N. and N.M.N.; methodology, A.G.N., M.R.Z., K.K.K. and M.S.M.K.; software, A.G.N.; validation, A.G.N., N.M.N. and M.R.Z.; formal analysis, A.G.N. and M.S.M.K.; investigation, A.G.N., A.A.M. and M.R.Z.; resources, N.M.N., A.A.M. and M.R.Z.; data curation, A.G.N. and M.S.M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.N.; writing—review and editing, N.M.N. and M.S.M.K.; visualization, A.G.N., K.K.K. and M.S.M.K.; supervision, N.M.N. and M.R.Z.; project administration, N.M.N.; funding acquisition, N.M.N. and M.R.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, under the Transdisciplinary Research Grant Scheme (TRGS/1/2020/UPM/7).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by Universiti Putra Malaysia throughout this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, D.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Hao, X.; Yu, H.; Bai, L. Optimizing anaerobic acidogenesis: Synergistic effects of thermal pretreatment of composting, oxygen regulation, and additive supplementation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.; Pineda Herrera, J.C.; Vanegas, J.; Soler, J.; Peña, J.; Pérez, P.; Pinilla, J. Biochar, compost, and effective microorganisms: Evaluating the recovery of post-clay mining soil. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Zou, R.; Song, B.; Wang, D.; Wang, H.; Li, Y. Greenhouse gas emissions from co-composting of green waste and kitchen waste at different ratios. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Figueiredo, C.C.; Melo, L.C.A.; Silva, C.A.; Fachini, J.; Da Silva Carneiro, J.S.; De Morais, E.G.; Ndoung, O.C.N.; Singh, S.V.; Nandipamu, T.M.K. Nutrient enriched and co-composted biochar: System productivity and environmental sustainability. In Biochar-Based Composting Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncks, P.; Corrêa, K.; Guidoni, L.L.C.; Moncks, R.; Corrêa, L.; Lucia, T.; Araujo, R.; Yamin, A.; Marques, F. Moisture content monitoring in industrial-scale composting systems using low-cost sensor-based machine learning techniques. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleman, B.; Alessi, E.; Passaniti, F.; Daly, K. Evaluation of the applicability of a metal oxide semiconductor gas sensor for methane emissions from agriculture. Inf. Process. Agric. 2023; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiense, K.M.S.M.; Linhares, F.G.; Inácio, C.T.; Sthel, M.S.; Vargas, H.; Da Silva, M.G. Photoacoustic-based sensor for real-time monitoring of methane and nitrous oxide in composting. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 341, 129974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Das, B.S.; Ali, M.N.; Li, B.; Sarathjith, M.; Majumdar, K.; Ray, D. Rapid estimation of compost enzymatic activity by spectral analysis method combined with machine learning. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Hu, X.; Wei, Z.; Mei, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y. A fast and easy method for predicting agricultural waste compost maturity by image-based deep learning. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, E.C.; Temel, F.A.; Yolcu, O.C.; Turan, N.G. Modeling and optimization of process parameters in co-composting of tea waste and food waste: Radial basis function neural networks and genetic algorithm. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayındır, Y.; Yolcu, O.C.; Temel, F.A.; Turan, N.G. Evaluation of a cascade artificial neural network for modeling and optimization of process parameters in co-composting of cattle manure and municipal solid waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 318, 115496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. Greenhouse data acquisition system based on ZigBee wireless sensor network to promote the development of agricultural economy. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 101689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, G.P.; Asha, P.; Sandhya, G.; Sharma, S.V.; Shilpashree, S.; Subramanya, S. An intelligent IoT sensor coupled precision irrigation model for agriculture. Meas. Sens. 2023, 25, 100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Zhu, T.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Hao, L. Electric heating promotes sludge composting process: Optimization of heating method through machine learning algorithms. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepe, P.T.; Ibarra, R.G.; Namur, E.C.; Heredia, K.V. Closing the loop: Industrial bioplastics composting. In Industrial Bioplastics: Processing, Degradation, and Environmental Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Mehlawat, S.; Dhariwal, N.; Kumar, A.; Sanger, A. Comprehensive review on gas sensors: Unveiling recent developments and addressing challenges. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2024, 308, 117616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Test Methods for Evaluating Solid Waste: Physical/Chemical Methods (SW-846), Update III; Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Awasthi, S.K.; Sindhu, R.; Binod, P.; Pandey, A.; Awasthi, M.K. Introduction: Trends in composting and vermicomposting technologies. In Composting and Vermicomposting Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 16000-1:2004; Indoor Air—Part 1: General Aspects of Sampling Strategy. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- ISO 16000-6:2011; Indoor Air—Part 6: Determination of Carbon Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide in Indoor Air. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 3A—Determination of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide Concentrations in Emissions from Stationary Sources (Instrumental Analyzer Procedures); Code of Federal Regulations, 40 CFR Part 60, Appendix A-1; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Method 25C—Determination of Nonmethane Organic Compounds (NMOC) in Landfill Gases; Code of Federal Regulations, 40 CFR Part 60, Appendix A-8; USEPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Huang, L.T.; Hou, J.Y.; Liu, H.T. Machine-learning intervention progress in the field of organic waste composting: Simulation prediction optimization and challenges. Waste Manag. 2024, 178, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaparthy, V.S.; Singh, D.N.; Baghini, M.S. Compensation of temperature effects for in-situ soil moisture measurement by DPHP sensors. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, S.G.; Yuvaraja, S.; Varrla, E.; Baghini, M.S.; Palaparthy, V.S.; Salama, K.N. An in-field integrated capacitive sensor for rapid detection and quantification of soil moisture. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 321, 128542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Maleki, M.R.; Khodaei, J. Laboratory evaluation of infrared and ultrasonic rangefinder sensors for on-the-go measurement of soil surface roughness. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 229, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6142-1:2015; Gas Analysis—Preparation of Calibration Gas Mixtures—Part 1: Gravimetric Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO 10780:1994; Stationary Source Emissions—Measurement of Velocity and Volume Flow Rate of Gas Streams in Ducts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1994.

- Mahapatra, S.; Ali, M.H.; Samal, K. Assessment of compost maturity–stability indices and recent development of composting bin. Energy Nexus 2022, 6, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, H.; Temel, F.A.; Yolcu, O.C.; Turan, N.G. Modelling and optimization of sewage sludge composting using biomass ash via deep neural network and genetic algorithm. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Bolan, N.; Joseph, S.; Anh, M.T.L.; Meier, S.; Kookana, R.; Borchard, N.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Jindo, K.; Solaiman, Z.M.; et al. Complementing compost with biochar for agriculture, soil remediation and climate mitigation. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, P.; Tabassum-Abbasi, N.; Abbasi, S. Use of prosopis as compost/vermicompost. In Prosopis for Sustainable Livelihoods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, W.; Ma, Y.; Ma, J.; Gao, Y.M.; Zhang, X.; Li, J. Gasification filter cake reduces the emissions of ammonia and enriches the concentration of phosphorous in Caragana microphylla residue compost. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 315, 123832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Adamchuk, V.I.; Whalen, J.K.; Ismail, A.A. Development of an NDIR CO2 sensor-based system for assessing soil toxicity using substrate-induced respiration. Sensors 2015, 15, 4734–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, S.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Zhou, T. Online shock sensing for rotary machinery using encoder signal. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 182, 109559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).