Abstract

This study investigates the influence mechanism of key factors on the heating value of syngas during underground coal gasification (UCG) and proposes an optimization path for enhanced energy conversion efficiency based on typical global field test data. Integrating data review and pattern analysis, it systematically explores the influence of core factors, including coal seam characteristics, reactor structure, and gasification agent ratio. It is found that the relationship between syngas heating value and coal rank is not simply linear, with representative heating values ranging from 4.13 to 11.96 MJ/m3. Medium-rank coal, characterized by “medium volatile matter and low ash content”, yields high-heating-value syngas when paired with air/steam as the gasification agent. Shaftless reactor structures demonstrate superior overall performance compared to shaft-based designs, with the representative heating value improving from 3.83 MJ/m3 to 7.8 MJ/m3. The combination of U-shaped horizontal wells with the Controlled Retracting Injection Point (CRIP) technology improves the heating value. Effective control over the syngas heating value can be achieved by optimized composition and ratio of the gasification agent, with representative value of 9.10 MJ/m3 in oxygen-enriched steam gasification compared to 4.28 MJ/m3 in air gasification. Based on an evaluation of data fluctuation characteristics, the significance ranking of the factors is as follows: gasification agent, coal rank, and reactor structure. Consequently, an engineering optimization path for enhancing UCG syngas heating value is proposed: prioritize optimizing the composition and ratio of the gasification agent as the primary means of heating value control; on this basis, rationally select coal rank resources, focusing on process compatibility to mitigate performance fluctuations; and then incorporate advanced reactor structures to construct a synergistic and efficient gasification system. This research can provide theoretical support and data references for engineering site selection, process design, and operational control of UCG projects.

1. Introduction

1.1. The UCG Technology

Underground coal gasification (UCG) is a highly promising green technology that converts in situ coal seams into combustible gas without the need for physical mining. The UCG process can utilize coal seams that are too deep or too thin to be extracted by conventional methods, thereby significantly increasing the globally recoverable coal reserves. Compared to underground and open-pit mining, UCG offers advantages in safety, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness.

The concept of UCG was first proposed in 1868 by the German scientist William Siemens. By the late 19th century, the Russian scientist Dmitri Mendeleev had outlined a UCG process [1]. Since 1930s, a series of field trials globally have been conducted, including shaft-type and shaftless methods [2,3,4,5,6,7].

From 1957 to 1962, the UCG practices in the former Soviet Union produced a cumulative total of 50 billion cubic meters of syngas [8]. However, in 1964, the Soviet government deemed the UCG process too complex and relatively costly, resolving to halt new UCG projects [9]. Despite this, some projects continued to operate until the 1990s [2,10]. Many European Union countries, rich in coal resources, also conducted UCG trials. The development of UCG technology in Australia originated from a preliminary study on UCG conducted for the Anna lignite deposit in South Australia [11]. This eventually led to power generation and gradual plans for commercialization. In 1997, Linc Energy established a power plant using UCG syngas [11,12,13], and several trials were subsequently initiated [14].

Despite stagnation of field tests in many countries, the potential of UCG for resource development and industrial application as an unconventional coal utilization technology has attracted extensive attention. By converting coal into syngas in situ underground, UCG can not only exploit coal resources that are difficult to access via traditional mining methods but also extract effective components for residential gas supply, power generation, and the production of chemical products, including hydrogen, amine, and synthetic oil–gas [15,16,17], which holds significant practical significance and long-term strategic value for optimizing coal-dominated energy structures such as in China [18].

The core risk for UCG industrialization lies in environmental protection [19], yet its environmental hazards are far less severe than those of solid-state coal mining, and such risks can be prevented and controlled through geological site selection and engineering measures. In terms of site selection, avoiding water-conducting structures and ensuring a safe distance between coal seams and overlying as well as underlying aquifers can mitigate the risks of ground subsidence and pollution. In terms of engineering, controlling operating pressure and equipping with environmental protection devices can prevent the cross-flow of gasification products and recover volatile hazardous substances [20].

The gas produced by coal gasification process is commonly referred to as synthesis gas or syngas. The core process involves converting solid coal into syngas (primarily composed of CO, H2, and CH4) through thermochemical reactions. The entire process can be divided into three stages: combustion, pyrolysis, and gasification. The specific mechanisms are as follows:

Combustion Stage (corresponding to oxidation reactions): This stage releases heat through oxidation reactions, providing the high-temperature conditions necessary for subsequent reactions. It serves as the foundation driving the reduction and pyrolysis reactions, effectively “igniting and supplying heat” to the underground gasifier.

Pyrolysis Stage (corresponding to drying and pyrolysis reactions): Heating causes the organic matter in coal to decompose, releasing volatiles (such as H2, CH4, tar, etc.) while simultaneously removing moisture from the coal. The volatiles released during pyrolysis directly contribute to the syngas composition and provide feedstock for methanation reactions.

Gasification Stage (corresponding to reduction and gasification reactions): Reduction reactions are the primary source of syngas. Their endothermic nature relies on heat supplied by the combustion stage, creating an energy coupling of “exothermic oxidation–endothermic reduction”.

Major reactions for these three stages are listed in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Fundamental reactions in UCG.

1.2. Key Processes

The core of UCG involves the in situ conversion of coal seams through steps such as well drilling, channel construction, gasification agent injection, reaction control, and gas collection and treatment. Specifically:

- (1)

- Well Drilling: The purpose is to establish connection channels between the surface and the reactor underground for injecting the gasification agent and extracting the syngas. Wells include injection wells, production wells, and monitoring wells. Common well layout configurations include linear and U-shaped wells.

- (2)

- Channel Construction: The purpose is to establish a stable gasification reaction zone within the coal seam, ensuring full contact between the gasification agent and the coal. Technical methods include reverse combustion linking, hydraulic fracturing, and directional drilling. The constructed channels are expected to have sufficient permeability, stability, and controllability.

- (3)

- Gasification Agent Injection: The purpose is to provide the oxygen and steam necessary for chemical reactions and to regulate the syngas composition. Common gasification agent components include oxygen (O2) and steam (H2O). Injection methods include continuous injection and pulsed injection, or forward gasification and reverse gasification.

- (4)

- Gasification Reaction Control: The purpose is to maintain an efficient and stable gasification process, avoiding coal seam collapse or pollution in neighboring aquifers through a controlled injection rate of agent and reaction pressure.

- (5)

- Syngas Collection and Treatment: The purpose is to extract the syngas and purify it of impurities to meet the requirements for subsequent utilization. This generally involves surface treatment processes, including dust removal, cooling, desulfurization, and CO2 capture. Utilization pathways for the syngas typically include power generation, chemical feedstock, and hydrogen production.

2. Review of Field Test Data

Based on the main process flow and reaction mechanisms, this section compiles and reviews the heating value of syngas from various UCG projects globally, with statistical categorization based on three main influencing factors: coal seam characteristics, reactor structure, and gasification agent ratio.

2.1. Influences of Coal Seam Characteristics

The collected project data, listed in the order of coal rank, are summarized in Table 2.

Natural conditions of energy reservoirs, including coal seams, form the fundamental constraints for engineering implementation and outcomes of project development [21,22,23]. This is the same for the case of UCG, where coal quality decisively influences the gasification reaction process and syngas quality [24,25,26]. It directly affects the thermodynamic equilibrium and kinetic pathways of multiphase reactions such as pyrolysis, gasification, and combustion, thereby systematically altering the composition distribution and energy density of syngas.

Table 2.

List of global UCG field tests, by coal ranks [3,5,27].

Table 2.

List of global UCG field tests, by coal ranks [3,5,27].

| Coal Rank | Test Time | Local | Coal Type | Reactor Structure | Gasification Agent | Syngas Heating Value (MJ/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 1935 | Gorlovskaya | Lignite | Shaft-based | Oxy–air | 4.18 |

| 1956~1962 | Angern | Lignite | Vertical well | Oxy–air | 3.6 | |

| 1935~1936 | Leninsk-Kuznetsk | Lignite | Shaft-based | Air | 4.6 | |

| Medium | 1997 | Yilan Coal Mine, Heilongjiang | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 5.00 |

| 1998 | Yima North Open-Pit Mine | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 5.24 | |

| 1958 | Hujiawan Coal Mine, Datong | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 3.81 | |

| 1958 | Jiaohe Coal Mine, Jilin | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 3.49 | |

| 1958 | Xingshan Coal Mine, Hegang | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 5.53 | |

| 2000 | Suncun Coal Mine, Xinwen | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air/steam | 5.21 | |

| 2001 | Xiezhuang Coal Mine, Xinwen | Bituminous | Hybrid | Air/steam | 8.37 | |

| 1994 | Xinhe Coal Mine, Xuzhou | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air/steam | 11.83 | |

| 1996 | Liuzhuang Coal Mine, Tangshan | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air/steam | 12.24 | |

| 1978 | Rocky Hill | Sub-bituminous | Hybrid | Air | 7.4 | |

| 1998 | Hebi No.3 Coal Mine | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 4.82 | |

| 2001 | Panzhihua Coal Mine | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Air | 4.20 | |

| 2010 | Yuan’ankou Coal Mine, Huating | Bituminous | Hybrid | Air/steam | 3.47~10.72 | |

| 1940 | Lisichanskaya | Bituminous | Shaft-based | Oxy–air | 3.75 | |

| 1979 | Pricetown 1 | Bituminous | Vertical well | Air | 6.9 | |

| 2016 | Shanjiashu Coal Mine, Panjiang | Bituminous | Hybrid | Air/steam | 9.00 | |

| High | 2001 | Lifuyu Coal Mine, Xiyang | Anthracite | Shaft-based | Air/steam | 11.91 |

| 1949~1950 | Djerada | Anthracite | Shaft-based | Air | 1.3~2.5 | |

| 1986~1987 | Thulin | Anthracite | Vertical well | Air | 21 |

From the field test data presented in Table 2, it can be observed that a higher degree of coalification generally leads to a higher syngas heating value. However, this is not a strictly positive correlation. Low-rank coals often have high ash and moisture content. Excessively high ash content can inhibit reaction efficiency, potentially reducing the heating value. Coal suitable for UCG should possess characteristics of “high volatile matter and low caking propensity”, which are more readily met by low- to medium-rank coals. While high-rank coals (like anthracite) have low volatile matter and high fixed carbon content, despite their high carbon content, their low reactivity may lead to decreased CO/H2 generation efficiency, resulting in syngas that does not necessarily have a higher heating value [8].

Moisture, ash content, volatile matter, and the proportion of fine particles in the coal all affect its combustion value [28]. It is suggested [29] that when the volatile matter content is fixed, the height of coal microcrystals shows a negative linear relationship with ash content. An increase in ash content leads to a lower degree of graphitization and increased disorder in the carbon structure, indicating that ash inhibits combustion. Other factors, such as the carbon–hydrogen ratio and oxygen–carbon ratio, also play a role [30]. Therefore, the relationship between UCG syngas heating value and the degree of coalification cannot be considered simply linear.

2.2. Reactor Structure

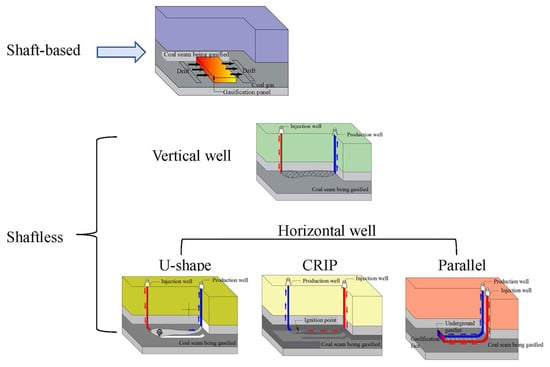

The reactor structures in UCG (UCG) are primarily categorized into two main types: shaftless and shaft-based. The shaft-based type, represented by the mineshaft method, requires the excavation of vertical shafts and tunnels or utilizes existing mine roadways to access the coal seam. While this approach facilitates process control, it suffers from high construction costs, the need for underground manual operations, and significant safety risks. In contrast, the shaftless method achieves gasification through drilling from the surface and mainly includes two configurations: vertical wells and horizontal wells. The vertical well configuration typically involves drilling one injection well and one production well. As a current advanced technology, the horizontal well configuration mostly adopts a “U-shaped” structure, where two vertical wells are connected by a horizontal borehole within the coal seam, forming a long-distance, stable, and controllable gasification channel. The structures of shaft-based reactors and representative shaftless reactors are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of shaft-based reactor and representative shaftless reactors.

Table 3 lists representative UCG trial projects categorized by reactor structure. It can be observed that, under the same coal type and gasifying agent conditions, different gasification processes significantly affect the heating value of syngas.

Table 3.

List of global UCG field tests, by reactor structure.

From the perspective of reactor structure, long-channel, large-cross-section gasifiers [31] provide a larger reaction surface area and a longer pyrolysis and drying zone, which facilitate the formation of a stable high-temperature reaction field. This promotes thorough cracking of volatiles and methanation reactions, thereby increasing the content of combustible components in the syngas and enhancing its heating value.

The influence of a good layout on syngas heating value is primarily reflected in the uniformity of gasifying agent distribution and the completeness of the gasification reaction. An appropriate well spacing and layout ensure even penetration of the gasifying agent into the coal seam, promoting comprehensive gasification reactions. If the well spacing is too large, it may lead to poor connectivity of gasification channels, incomplete local coal gasification, and an increase in inert components such as CO2, thereby reducing the heating value.

As a critical step in the formation of gasification channels, the linkage method directly affects the geometric shape and thermodynamic conditions of the gasification channels by controlling the direction and speed of combustion. Significant differences exist between forward combustion linkage and reverse combustion linkage in terms of channel quality, linkage speed, and gas distribution, which in turn influence the heating value of the syngas.

In experiments with bituminous coal from the former Soviet Union, when the same gasification process and gasifying agent were used, subsequent trials yielded syngas with a higher heating value. This reflects how improved process control maturity helps optimize the reaction process, thereby increasing the proportion of combustible components and the heating value.

Research on UCG projects for U.S. bituminous coal shows that when using a vertical well reactor with air as the gasifying agent, the linkage method of vertical well connection produced the highest syngas heating value, while the hydraulic fracturing linkage method yielded the lowest. This is closely related to differences in the stability and permeability of gas flow channels under different linkage methods. When the gasifying agent was changed to an oxygen-enriched air/H2O mixture, the Controlled Retracting Injection Point (CRIP) linkage method produced syngas with a higher heating value, confirming the importance of the synergistic effect between specific linkage methods and gasifying agents in enhancing heating value.

According to field trial data, the impact of different coal types and process combinations on syngas heating value varies significantly. In field trials with Australian sub-bituminous coal, although the optimal process configuration was not clearly identified, the use of the CRIP linkage method demonstrated potential for generating high-heating-value syngas, indicating its advantage in optimizing reaction conditions. In EU anthracite projects, the Belgian Thulin project employed vertical wells with hydraulic fracturing linkage, while the UK Newman Spinney project used vertical wells and an integrated reactor type. Both produced syngas with higher heating values than other processes.

2.3. Gasification Agent Ratio

The ratio of the gasification agent primarily influences the process by affecting reaction pathways, product distribution, and thermodynamic conditions. Representative UCG field test projects are categorized in Table 4 according to the type of gasification agent used.

Table 4.

List of global UCG field tests, by reaction agent.

In the US Hoe Creek project, using oxy–air/H2O as the gasification agent nearly doubled the syngas heating value compared to using air alone. The Rawlins 1 sub-bituminous coal project achieved an approximately 40% increase in heating value under oxy–air/H2O gasification conditions. In the Belgian Bois-La-Dame project, switching the gasification agent from air to oxy–air/H2O increased the heating value by 1.6 to 3.7 times. These results consistently demonstrate that introducing oxygen and steam significantly optimizes the gasification reaction pathways and product composition.

The Australian Bloodwood Creek project further revealed that using an oxy–air/H2O combination as the gasification agent yielded a higher heating value than the oxy–air condition, indicating a synergistic effect between the gasification agent combination and the process method. In Chinese cases, although the Xinhe project employed a shaft-type process, its heating value using air/steam as the gasification agent was still higher than that of the Mazhuang project using a hybrid process with air gasification, showing an increase of 135.66%. In the Xintai Suncun project, using air/steam for gas coal gasification increased the heating value by 39.84% compared to the Datong Huijiawan project. The Panjiang Shanjiaoshu project achieved a 57.07% increase in heating value during coking coal gasification. Besides changing the gasification agent from steam to steam/air, the shift from a shaft-type to a hybrid process was also a key factor, further confirming the joint regulatory effect of the gasification agent and process synergy on heating value.

Research indicates that when air is used as the gasification agent, the dilution effect of nitrogen reduces the proportion of combustible components, typically resulting in a heating value only about half that under oxygen gasification conditions [32]. Oxygen-enriched agent helps utilize moisture in the coal seam to participate in the water–gas reaction, increasing H2 and CO content. However, difficulty in maintaining stable steam content can lead to fluctuations in gas composition [33]. Adjusting the gasification agent to a steam–oxygen mixture can improve reaction efficiency [34]. As the steam/oxygen ratio increases, H2 and CH4 content correspondingly rise. Nevertheless, it is essential to rationally control the oxygen supply and steam ratio to maintain the thermal balance and reaction stability in the gasification zone.

In summary, switching the gasification agent from air to oxygen-enriched/steam combinations is a key pathway to enhancing syngas heating value. Combined gasification agents effectively increase the content of combustible components, thereby improving heating value by intensifying oxidation reactions and promoting water–gas reactions. Further exploration of the gasification agent ratio and its synergistic mechanisms with process parameters such as reactor type and linking methods represents an important direction for optimizing UCG syngas quality.

3. Analysis on Influencing Factors

3.1. Coal Seam Characteristics

3.1.1. Influencing Factors

Coal seam characteristics include parameters such as coal rank, seam thickness, burial depth, and dip angle [35]. Suitable coal seam thickness for UCG projects typically ranges from 1.5 to 15 m and has a significant influence on the syngas heating value [36]. Research shows that higher coal ranks require a lower minimum seam thickness: lignite usually requires more than 2.0 m, whereas bituminous coal and anthracite can be as low as 0.8 m. Furthermore, in thick coal seams, the ratio of partings to coal seam thickness should ideally be less than 0.5, and the thickness of a single parting layer should not exceed 0.5 m to ensure stable gasification [37,38].

Regarding burial depth, successfully implemented UCG projects are mostly located within the depth range of 100 to 500 m [39]. Shallow coal seams have low gasification pressure and high heat loss, potentially resulting in poor gas quality [40]. As burial depth increases, formation pressure rises, and the porosity and permeability of the surrounding rock decrease, helping to reduce the escape of the gasification agent and syngas [41]. Although deep coal seam gasification can reduce the risk of groundwater contamination and increase CH4 generation potential, it imposes higher demands on geological exploration and process technology levels [39].

Concerning the coal seam dip angle, the applicable range for UCG is generally between 0° and 70° [39,42]. Studies indicate that a gasification dip angle of around 35° is relatively optimal, as it can effectively avoid the impact of ash and slag falling after combustion [43,44], but it places more stringent requirements on gasifier site selection [45].

In summary, the influences of factors such as coal seam thickness, burial depth, and dip angle are relatively well understood. This section will focus on the influence of coal rank on the heating value of UCG syngas.

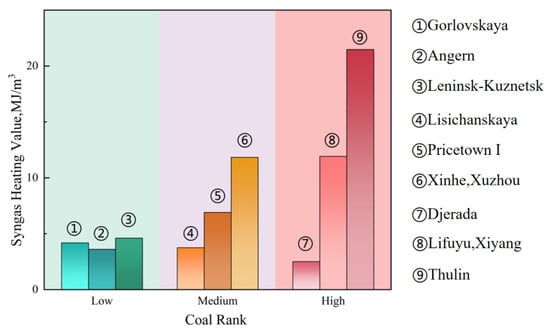

3.1.2. Influence of Coal Rank

Field trial data reveal the complex influence of coal rank on syngas heating value. As shown in Figure 2, in low-rank coal trials, the former Soviet Union’s Gorlovskaya project (lignite) achieved syngas heating values of 4.18 MJ/m3 and 4.60 MJ/m3, respectively, while the Angren project reached 3.60 MJ/m3—their heating value levels approach those of some medium-rank coal projects. The medium-rank coal group includes the Lisichanskaya, Pricetown I, and Xuzhou Xinhe projects; the high-rank coal group comprises the Djerada, Xiyang Lifuyu, and Thulin projects.

Figure 2.

Syngas heating value of typical field tests with different coal ranks.

The data show a complex pattern: while some medium- and high-rank coal cases exceed certain low-rank coal projects in heating value, others show the opposite trend. This confirms that the relationship is not simply linear but is governed by a combination of factors, including coal composition, gasification technology, and reaction conditions.

3.1.3. Summary of Influences

Although low-rank coal has low fixed carbon content, its high volatile matter and strong reactivity facilitate the generation of H2 and CH4 under identical process conditions.

Medium-rank coal balances carbon content with reactivity, exhibiting the potential for higher syngas heating values under suitable conditions. For instance, the Chinese Xuzhou Xinhe and Tangshan Liuzhuang projects, using air/steam agents, achieved syngas heating values of 11.83 MJ/m3 and 12.24 MJ/m3, respectively. This performance stems from the “medium volatile matter and low ash content” of bituminous coal, which avoids the high moisture heat penalty of low-rank coal and the conversion challenges due to low reactivity in high-rank coal.

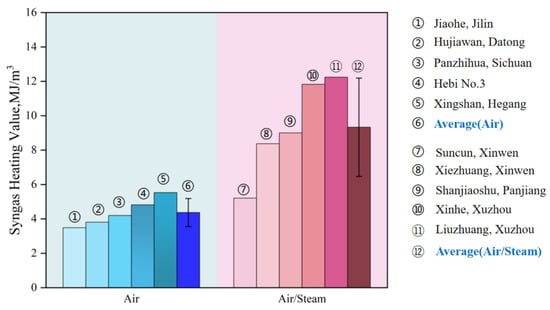

Figure 3 further compares the individual and average syngas heating values of medium-rank coals with air or air/steam injection. An obvious improvement can be observed when switching from air to air/steam injection, and medium-rank coals have the potential to yield higher heating values with air/steam reaction agents.

Figure 3.

Comparison of individual and average syngas heating values of medium-rank coals with air or air/steam injection.

The inherent contradiction between high fixed carbon content and low reactivity in high-rank coals is evident. For example, the Chinese Xiyang Lifuyu anthracite project (190 m depth, air/steam) achieved 11.91 MJ/m3 through system optimization. In contrast, the Djerada anthracite project (air only) yielded only 1.3–2.5 MJ/m3—a difference of 4–9 times. This comparison demonstrates that unlocking the conversion potential of high-rank coal requires synergistic intensification of gasification conditions (e.g., high temperature, high pressure).

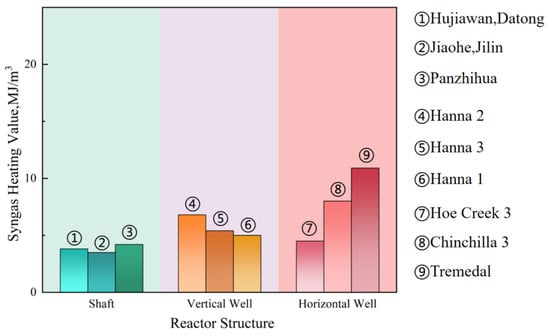

3.2. Influence of Reactor Structure

Field trial data reveal a clear correlation between reactor type and syngas heating value. As shown in Figure 4, shaft-based reactors (e.g., Datong Huijiawan, Jilin Jiaobe, Panzhihua) yielded syngas with heating values in the range of 3.49–4.20 MJ/m3. Vertical well reactors (e.g., Hanna series) achieved 5.0–6.8 MJ/m3. Horizontal well reactors (e.g., Hoe Creek 3, Chinchilla 3, Tremedal) demonstrated a broader and higher range of 4.5–10.9 MJ/m3.

Figure 4.

Syngas heating value of typical field tests with different reactor structures.

This performance hierarchy is attributed to the superior gasification reaction channel provided by shaftless methods, particularly horizontal wells. For example, the long channel length (typically >100 m) in horizontal wells more than doubles that of vertical wells (<50 m), significantly extending gas residence time and promoting more complete gasification reactions. This is evidenced by the high heating values achieved in projects such as the Australian Chinchilla (8.0 MJ/m3) and the Spanish El Tremedal “U”-shaped well (11 MJ/m3).

Furthermore, the linking method proves to be a critical factor within a given reactor type. A comparative analysis of U.S. trials illustrates this point: the Rocky Mountain 1 project, employing directional drilling combined with CRIP technology, achieved a high syngas heating value of 10.3–11.3 MJ/m3. In contrast, the contemporaneous Hanna 1 project, which used hydraulic fracturing for linking, yielded a significantly lower value of 4.20–5.0 MJ/m3. The advantage of CRIP technology lies in its precise control over the burn front advance rate (0.5–1.0 m/d), which helps maintain process continuity and stability by avoiding channel blockages common in less controlled methods.

3.3. Influence of Gasification Agent

The performance of different gasification agents is quantified in Figure 5. Projects using only air (e.g., Jilin Jiaoke, Datong Huijiawan, Hegang Xingshan) yielded syngas with heating values of 3.49 MJ/m3, 3.81 MJ/m3, and 4.53 MJ/m3, respectively. In contrast, projects employing air/steam mixtures (e.g., Xuzhou Xinhe, Tangshan Liuzhuang, Xintai Suncun) achieved significantly higher values of 11.83 MJ/m3, 12.24 MJ/m3, and 5.73 MJ/m3. The oxy–air/steam combination (e.g., Hoe Creek 3, Rawlins 1, Hoe Creek 2) resulted in heating values of 8.4 MJ/m3, 8.4 MJ/m3, and 10.5 MJ/m3, respectively.

Figure 5.

Syngas heating value of typical field tests with different reaction agents.

This data reveals a clear ‘step-wise improvement’ pattern correlating with agent complexity. Switching from air to air/steam results in the most significant leap in heating value, primarily due to steam driving the water–gas reaction. For instance, China’s Xuzhou Xinhe project (air/steam) showed a 135.66% increase compared to the Xuzhou Mazhuang project (air) using similar coal.

Further enhancement is observed with oxy–air/steam agents. The U.S. Hoe Creek 2 project saw a 144% increase (from 4.3 to 10.5 MJ/m3), and Belgium’s Bois-La-Dame project improved by 1.6–3.7 times. Notably, the Australian Bloodwood Creek project under oxy–air/steam conditions yielded a heating value 20–140% higher than under oxy–air alone, highlighting the synergistic effect of steam and oxygen.

While the oxy–air/steam combination demonstrates robust performance, its superiority over the air/steam mixture in terms of maximum achievable heating value requires further systematic investigation, as the current dataset shows overlapping performance ranges (e.g., 8.4–10.5 MJ/m3 for oxy–air/steam vs. up to 12.24 MJ/m3 for air/steam).

3.4. Ranking the Influence Factors

As can be seen from Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, whether by selecting coal resources of higher ranks, modifying the reactor structure, or changing the gasification agent composition and ratio, all have positive effects on increasing syngas heating value. Further analysis and organization of the data from Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 are presented in Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 5.

Syngas heating value in Figure 1.

Table 6.

Syngas heating value in Figure 2.

Table 7.

Syngas heating value in Figure 3.

Regarding coal rank, the average syngas heating value shows an increasing trend with higher coal rank. Based on the average data for each group in Table 5, low-rank coal averages 4.13 MJ/m3, medium-rank coal averages 7.49 MJ/m3 (an increase of 81.36% from low-rank coal), and high-rank coal reaches 11.96 MJ/m3 (a 59.68% increase compared to medium-rank coal). Although high-rank coal has the potential for high heating values, the actual value is significantly constrained by process compatibility, reflecting certain limitations in the influence of coal rank itself.

In terms of reactor structure, shaftless designs are generally superior to shaft-based ones. In Table 6, the average heating values for vertical well and horizontal well configurations are 5.73 MJ/m3 and 7.8 MJ/m3, respectively. These represent increases of 49.61% and 103.66% compared to the shaft-based (mineshaft) average of 3.83 MJ/m3. Among shaftless types, the average heating value for horizontal wells is 36.13% higher than for vertical wells. The improvement from reactor structure shows a step-like increase, but the magnitude of increase is less than that achieved by changing the coal rank. Horizontal wells, by providing a longer gasification channel and more sufficient gas–solid reaction time, demonstrate the best heating value performance; however, their techno-economic feasibility still requires comprehensive evaluation. Comparing the influence of coal rank and reactor structure overall, changing the coal rank has a more significant effect on enhancing the heating value.

For the gasification agent, its type and ratio demonstrate the strongest control capability. As shown in Table 7, the average heating value using only air is 4.28 MJ/m3. After introducing steam, the heating value increases to 9.93 MJ/m3, a rise of 132.01%. When further combined into an oxy–air/steam system, the heating value is 9.10 MJ/m3. Although this is a 112.62% increase compared to using air alone, it is slightly lower than the air/steam system. Overall, adjustment of the gasification agent is not only highly effective but also offers advantages in operational flexibility and cost-effectiveness.

To quantitatively evaluate the impact of each of the investigated factors—coal rank, reactor structure and gasification agent—we proposed an analytical method based on data fluctuation characteristics. This method defines the following two key metrics:

Intra-group deviation (Sin-group): Refers to the relative deviation between individual data points and the group mean under the influence of only one factor (coal rank, reactor structure, or gasification agent) of a given factor. This metric characterizes the dispersion degree of data within the group and is calculated by Equation (1):

where Xi is the individual value, and is the mean value within the group.

Inter-group deviation (Sgroup): Reflects the overall fluctuation amplitude of syngas heating value caused by variations between different levels of a factor. This metric is used to assess the significance of the factor’s influence on heating value and is calculated by Equation (2):

where is the overall average of all three group means.

The specific calculation results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

UCG Syngas fluctuation amplitude.

The results indicate that, for both coal rank and reactor structure, the intra-group variation exceeds the inter-group variation. This implies that although adjusting these parameters can increase the overall heating value of syngas, it also leads to greater data dispersion, reflecting higher instability in heating value output under such conditions. Hence, while these factors improve heating value, they simultaneously introduce significant performance fluctuations.

In contrast, for the gasification agent, the inter-group variation is greater than the intra-group variation. This indicates that modifying the gasification agent produces more pronounced overall changes in syngas heating value, while exhibiting relatively low dispersion within groups, suggesting better stability and controllability.

Thus, among the three factors, the gasification agent is regarded as the primary factor influencing syngas heating value, offering the most prominent and stable regulatory effect. When comparing coal rank and reactor structure via the same method, it indicates that modifying the reactor structure has a more significant impact on enhancing heating value.

In summary, the influence of each factor on syngas heating value can be ranked as follows: gasification agent, coal rank, and reactor structure. In practical engineering, it is recommended to prioritize the optimization of the gasification agent, combined with coal rank characteristics and reactor structure selection, to achieve systematic improvement in syngas heating value.

3.5. Multi-Factor Synergistic Interactions

A comprehensive analysis of the impact of coal rank, gasifier type, and gasifying agent on the heating value of syngas produced from underground coal gasification reveals that these three factors exhibit significant synergistic effects rather than simple independent additive influences. The essence of their interaction lies in the fact that the gasifying agent, as the most active “regulatory variable”, depends for its effectiveness on the “raw material basis” provided by coal rank and the “reaction environment” determined by the gasifier type.

Specifically, higher-rank coals possess the material potential to produce high-heating-value syngas due to their high fixed carbon content. However, realizing this potential depends on whether the gasifying agent can effectively overcome the kinetic limitations of their lower reactivity. For instance, for high-rank coals, the use of oxygen-enriched or oxygen-steam mixed gasifying agents can significantly raise the temperature in the gasification zone, accelerating carbon conversion and thereby translating their high heating potential into actual high-heating-value syngas. Conversely, if only air is used as the gasifying agent for high-rank coals, the low-temperature conditions may lead to incomplete reactions, resulting in actual heating values that could even be lower than those of lower-rank coals treated with appropriate gasifying agents. This explains why some high-rank coal projects exhibit fluctuating or lower-than-expected measured heating values.

The gasifier type further modulates this interaction by coupling with the flow and mixing characteristics of the gasifying agent. For example, horizontal wells provide longer controllable reaction channels, creating ideal conditions for the use of complex multi-component gasifying agents (such as oxygen-steam mixtures). This allows for more thorough and gradual reactions with the coal, synergistically enhancing the potential for higher syngas heating values.

Therefore, the production of high-heating-value syngas is the result of the matching and synergistic interaction of these three factors. Specifically, the gasifier type ensures reaction efficiency, while the gasifying agent overcomes the kinetic barriers of the coal, ultimately enabling stable and high-heating-value syngas production. The core of future process optimization lies in seeking the optimal coupling range for these three factors from a systemic perspective, rather than pursuing the extreme values of any single factor in isolation.

3.6. Technical Pathways for Enhancing Syngas Heating Value

Based on the significance analysis of the impacts of coal seam characteristics and process parameters on syngas heating value, the following three optimized technical pathways are proposed, ranked in descending order of their contribution to heating value enhancement:

Utilize Oxygen-Enriched Gasification Agents: As the primary influencing factor for heating value, the gasification agent composition exhibits the most significant inter-group fluctuation range (44.92%). Adjusting components such as oxygen concentration can substantially increase gasification reaction intensity and syngas heating value, with stable and highly controllable effects.

Select High-Rank Coal Resources: Although an increase in coal rank is accompanied by considerable intra-group fluctuation (79.52%), the average heating value increase is significant (high-rank coal reaches 11.96 MJ/m3). Attention should be paid to process compatibility to suppress heating value fluctuations during actual operation.

Promote Shaftless Horizontal Well Reactor Structures: The horizontal well structure demonstrates the best performance among reactor types, achieving an average heating value of 7.80 MJ/m3, which is a 103.66% improvement over the shaft-based (mineshaft) type. Its extended gasification channel facilitates more complete reactions, making it a crucial technical option for enhancing the system’s stable output.

In summary, engineering practices should prioritize optimizing the gasification agent composition and synergistically promote the selection of appropriate coal ranks alongside the application of advanced reactor structures to achieve systematic enhancement of syngas heating value.

4. Conclusions

Based on global UCG field test data, this study systematically investigated the influence patterns of coal seam characteristics, reactor structure, and gasification agents on syngas heating value. It clarified the mechanisms, influencing patterns, and factor selection criteria for each element. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Coal Seam Characteristics

Coal rank is not a single linear determinant of heating value and is also influenced by factors such as seam thickness, burial depth, and dip angle. For a given coal rank, the syngas heating value is also governed by the synergistic effects of volatile matter, ash content, and moisture. Low-rank coals, leveraging high volatile matter and strong reactivity, can achieve baseline heating value output under conventional processes. Medium-rank coals, balancing moderate carbon content with reactivity, exhibit optimal heating value potential when matched with suitable gasification agents. Although high-rank coals have high fixed carbon content, they rely on intensified process conditions like high temperature and high pressure for effective conversion, and their actual heating value is significantly affected by process compatibility.

(2) Reactor Structure

Reactor structure is a key controllable factor affecting UCG syngas heating value. Research shows that shaftless gasifiers significantly outperform shaft-based structures in syngas heating value performance. Among them, horizontal wells, especially those with a “U” shape, due to gasification channel lengths exceeding 100 m and gas residence times extending to tens of seconds, significantly promote more complete gasification reactions, achieving syngas heating values of 8.0–11.0 MJ/m3. Vertical well configurations, limited by shorter gasification channels typically less than 50 m, have a heating value range of 5.0–6.8 MJ/m3. Shaft-based (mineshaft) types, constrained by limited reaction space, achieve heating values of only 3.5–4.2 MJ/m3. These data clearly indicate that horizontal wells perform best, followed by vertical wells, with shaft-based types being the least effective.

Regarding linking technology, CRIP-based technologies, through precise control of the burn front advance, effectively improve gasification agent utilization and reaction stability. Systems using CRIP achieve significantly higher syngas heating values compared to those using traditional linking methods like hydraulic fracturing. Furthermore, hybrid reactor structures demonstrate improved adaptability under complex geological conditions, offering a viable technical alternative for areas with challenging geology.

(3) Gasification Agent Ratio

Gasification using only air, limited by the diluting effect of N2, yields the lowest heating value. Introducing steam significantly promotes the water–gas reaction, increasing the hydrogen proportion and substantially boosting the syngas heating value. Using an oxy–air/steam composite gasification agent further optimizes gas composition and heating value levels, as the oxygen enhances combustion intensity, providing the necessary thermal conditions for endothermic reactions. However, it must be acknowledged that inducing oxygen to enrich the agent might be constrained by higher operational costs or oxygen supply challenges in remote project sites. Therefore, a balanced cost-effectiveness analysis should be conducted to make decisions about the agent ratio.

Regarding ratio optimization, there is a suitable range for the steam-to-oxygen ratio; projects like the US Hoe Creek 2 and Belgium’s Bois-La-Dame suggest an optimal steam/O2 ratio range of 1–3, which helps balance hydrogen production and carbon conversion efficiency, achieving synergistic optimization of syngas heating value and composition. In summary, rational configuration of the gasification agent composition and ratio allows for effective control of syngas heating value, with oxygen-enriched steam gasification demonstrating significant technical advantages.

(4) Ranking the Influencing Factors

Comprehensive analysis reveals that coal rank, reactor structure, and gasification agent significantly influence UCG syngas heating value, but their influence mechanisms and degrees differ markedly. Based on data analysis and fluctuation characteristic evaluation, the significance ranking of the factors is gasification agent, coal rank, and reactor structure.

The gasification agent, as the factor with the greatest controllability, contributes most significantly to heating value enhancement through changes in its composition and exhibits good stability. Although coal rank has a fundamental influence on heating value, its effect is constrained by both coal composition and process compatibility, accompanied by considerable performance fluctuation. The reactor structure provides engineering assurance for the gasification process by optimizing the reaction space geometry and reactant residence time, but its influence on syngas is relatively limited when adopted alone.

(5) Multi-factor synergistic effort

The heating value of syngas is not determined by any single factor in isolation, but by their systematic interaction. The gasifying agent acts as a key regulatory variable, whose effectiveness depends on both the inherent reactivity of the coal and the reaction environment shaped by the gasifier. Therefore, achieving stable, high-heating-value syngas output relies on optimizing the coupling of these three elements, rather than maximizing any one individually. Future process development should prioritize this integrated, system-level approach.

Based on the above research, the following engineering optimization path is summarized: optimizing the composition and ratio of the gasification agent as the core means for heating value control; on this basis, appropriately select coal rank resources, emphasizing process compatibility to suppress performance fluctuations; incorporate advanced reactor structures to build a synergistic and efficient gasification system. This technical pathway provides a theoretical basis and engineering guidance for the stable enhancement of syngas heating value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.P.; Methodology, C.L. and Y.Z.; Validation, S.P.; Formal analysis, C.L., R.G. and S.L.; Investigation, C.L., S.P. and Q.H.; Data curation, R.G.; Writing—original draft, C.L.; Writing—review & editing, C.L., Y.Z., R.G., Q.H. and S.L.; Visualization, S.L.; Supervision, P.P.; Project administration, P.P.; Funding acquisition, C.L. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province, grant number [grant No. [2023]128] and Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd. [grant No. GZKJXM20232568). The APC was funded by the Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Province grant number [grant No. [2023]128].

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Chaojie Li, Ying Zhang, Ruyue Guo, Siran Peng, and Quan Hu were employed by the company Electric Power Research Institute of Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd. and Guizhou University, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Science and Technology Program of Guizhou Power Grid Co., Ltd. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zou, C.; Chen, Y.; Kong, L.; Sun, F.; Chen, S.; Dong, Z. Underground coal gasification and its strategic significance to the development of natural gas industry in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2019, 46, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G. UCG—Part I: Field demonstrations and process performance. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 158–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yi, T.; Yang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L. Underground coal gasification field tests in China: History and prospects. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S. Chemical mining technology for deep coal resources. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2017, 46, 679–691. [Google Scholar]

- Gregg, D.W.; Edgar, T.F. Underground coal gasification. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. 1978, 24, 753–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarenko, S.N.; Kreinin, E.V. Underground Coal Gasification in Kuzbass: Present and Future; Institute of Coal; Kemerovo Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences: Kemerovo, Russia, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Liu, S. Thoughts on commercial application of new UCG process LLTS–UCG. Sci. Technol. Guide 2003, 52, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutto, A.W.; Bazmi, A.A.; Zahedi, G. Underground coal gasification: From fundamentals to applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2013, 39, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yi, T.; Li, P.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Z. UCG industrialization in the Soviet Union: History and comments. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Capp, J.P.; Lowe, R.W.; Simon, D.W. Underground Gasification of Coal, 1945–1960: A Bibliography; Bureau of Mines: Washington, DC, USA, 1963.

- Austa Energy and Linc Energy N L. Preliminary Feasibility Study: UCG Fired Power Station near Ipswich, Queensland; Linc Energy: Brisbane, Australia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beath, A.; Wendt, M.; Mallett, C. Optimisation of UCG for improved performance and reduced environmental impact. In Proceedings of the 9th Australian Coal Science Conference, Brisbane, Australia, 26–29 November 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Beath, A.C.; Mark, M.R.; Mallett, C.W. An evaluation of the application of UCG technologies to electricity generation and production of synthesis gas. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soil Science, Cairns, Australia, 2–6 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. The development of UCG in Australia. In Underground Coal Gasification and Combustion; Michael, S.B., Alexander, Y.K., Eds.; Elsevier, Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nakaten, N.; Kempka, T. Techno-economic comparison of onshore and offshore underground coal gasification end–product competitiveness. Energies 2019, 12, 3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, W.; Liu, S. Comparative techno−eco nomic performance analysis of underground coal gasification and surface coal gasification based coal–to–hydrogen process. Energy 2022, 258, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Jin, J.; Zhou, Z. Research advances on the techno–economic evaluation of UCG projects. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Wu, C. A review: Geological feasibility and technological applicability of underground coal gasification. Coal Geol. Explor. 2022, 50, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Yi, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Jin, J.; Wang, L. Dilemma and countermeasure of policy construction of UCG industry. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Yi, T.; Wang, L.; Jin, J.; Zhou, Z.; Kong, W. Analysis of geological conditions for risk control of UCG project. J. China Coal Soc. 2023, 48, 290–306. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep–Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Liang, J.; Guo, S. Factors influence to stability of coal underground gasification. Coal Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11760:2005; Classification of Coals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- GB/T 5751–2009; National Technical Committee for Standardization of Coal of China. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Yi, T.; Chen, K.; Qin, Y. UCG pilot tests in the United States and their contributions to modern UCG technologies. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Youssefi, R.; Segers, T.; Norman, F.; Maier, J.; Scheffknecht, G. Experimental investigations of the ignitability of several coal dust qualities. Energies 2021, 14, 6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.; Liang, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Jiang, C. Effect of ash on coal structure and combustibility. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2019, 26, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Girolamo, A.; Grufas, A.; Lyamin, I.; Nishio, I.; Ninomiya, Y.; Zhang, L. Ignitability and combustibility of Yallourn pyrolysis char blended with pulverized coal injection coal under simulated blast furnace conditions. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 1858–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J. Development Prospects of Underground Coal Gasification in China. Coal Convers. 1994, 39–45. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=OfZxIIxxsvCrL_DRVTbzndN3yuyR_bQ8VNyauzuw3PI-Anb_eFIdko5uierRYETLdm8uLB2qxe5mfz-11SAE6xCEonBXpmwpyO9wTnKRw66ke6gHr5Edy4E0wBd-pwjfOXtAkBgCepIIk3Ku1yV9BjO7v5ibY0lBdKGkUQNz3hk=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Yang, L.H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S. Characteristics of temperature field during the oxygen-enriched underground coal gasification in steep seams. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2009, 32, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S. Underground coal gasification using oxygen and steam. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2009, 31, 1883–1982. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, G.; Sahajwalla, V. A mathematical model for the chemical reaction of a semi–infinite block of coal in UCG. Energy Fuels 2005, 19, 1679–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Yu, L.; Yang, F.; He, J.; Fan, B. Analysis on evaluation index of coal underground gasification resource conditions. Coal Chem. Ind. 2019, 42, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Song, R.; Lan, T. Review on characteristics and utilization of entrained—Flow coal gasification residue. Coal Sci. Technol. 2021, 49, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Qin, Y.; Li, G.; Shen, J.; Song, X.; Zhu, S.; Han, L. Research progress on influencing factors and evaluation methods of under ground coal gasification. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Zhou, R.; Pan, J.; Zhao, W.; Pan, X.; Peng, A. Location seletion and groundwater pollution prevention & control regarding UCG. Coal Sci. Technol. 2013, 41, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, Q.; Ping, L.; Huo, C.; Yang, H. Study on evaluation of geological conditions for UCG: Taking Zhuzhai Minefield of Jiangsu Province as an example. J. Henan Polytech. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, S.; Qin, Y.; Zhu, S.; Kong, Q.; Yang, L.; Sun, P. Progress of research on coal underground gasification impacting factors. Coal Geol. China 2020, 32, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, L. Study on the Overlying Strata Movement by UCG Mining in Matigou Coal Mine; China University of Mining & Technology: Xuzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Koukouzas, N.; Green, M.; Sheng, Y. Recent development on underground coal gasification and subsequent CO2 storage. J. Energy Inst. 2016, 89, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y. Mineral Resource Assessment and Its Application Research; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, M. Analysis of underground gasification geological condition in Yushugou coalmine area, Northern Hebei. Coal Geol. China 2008, 20, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. Geological conditions of underground coal gasification. Coal Geol. China 1995, 7, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.