Abstract

Model predictive control (MPC) ensures stable motor operation provided that accurate motor parameters and state information are available. However, in certain environments, direct sensor measurement of rotor position and speed is infeasible, and sensorless methods are required to estimate the rotor position and speed. Sensorless methods utilizing a sliding mode observer (SMO) and a quadrature phase-locked loop (QPLL) are widely adopted, but it may encounter issues such as inaccurate motor parameters and delayed measurement results. To address these challenges, this paper proposes an integrated method that employs a nonlinear extended state observer (NLESO) to reduce observation delays in rotor position estimation. Additionally, a model reference adaptive system (MRAS)-based inductance observer is utilized to correct parameter inaccuracies. This combined approach achieves robust motor control with low delay. Simulation results validate the effectiveness and robustness of the proposed method.

1. Introduction

Field-oriented control (FOC) is the most utilized method in PMSM control. It uses Park transfer and Clark transfer to analyze the three phrase currents in a rotor synchronous coordinate system [1]. Based on FOC, model predictive control has the advantages of fast dynamic response and stable current control [2,3]. Its basic principle is to predict the current for one or several future control periods, and then select the optimal control input through a cost function [4]. Its control effect relies on the precision of motor parameters and rotor position information [5]. Researchers have proposed a model predictive control method based on an incremental model, which eliminates the interference of inaccurate resistance and flux linkage on current prediction [6]. Traditional methods for obtaining rotor position information for motors mainly use mechanical sensors, but these sensors have the disadvantages of low resolution and high signal delay in high-speed environments [7,8]; meanwhile, in some extreme environments, the usage of mechanical sensors cannot be satisfied [9].

Sliding mode observer is a commonly used PMSM sensorless control method [10]. It constructs a current observer based on the voltage equation of the motor, uses current as the reference value, modifies the input value through a sliding mode control strategy, and tracks the estimated current to the reference current [11,12]. When the estimated current and the reference current are consistent, the sliding mode control input is equivalent to the actual back electromotive force (back-EMF) [13]. After low-pass filtering, the quadrature phase-locked loop is used to calculate the rotor position [12]. The sign function in the traditional sliding mode observer achieves system state convergence through high-frequency switching, but this switching action can cause significant system chattering [14,15]. The low-pass filter also increases the phase delay of the system [16]. On the other hand, the traditional QPLL has a lag in speed measurement when the motor speed changes, which cannot accurately measure the current speed and increases the rotor position estimation error [17]. To solve the above problems, researchers have proposed various improvement methods. Article [18] proposes using an improved full-order sliding mode observer, which has high estimation accuracy and stronger oscillation suppression ability for rotor position observation within a wide speed range, compared to traditional full-order sliding mode observers. In article [19], researchers combine the back-EMF model with the super-twisting algorithm to propose a super-twisting algorithm sliding mode observer, which simultaneously considers the uncertainties and unmodeled dynamics in the back-EMF model, giving the designed system smaller chatter, better estimation, and faster convergence. Article [20] designed a position compensation PLL, alleviating the position error introduced by the speed acceleration and deceleration ramps.

When the parameters of the motor change, there will be a significant deviation between the predicted value and the actual value in model predictive control [21,22], and the sliding mode observer’s estimates will also contain significant errors. Online parameter identification for correcting motor parameters suffers from high computational burden and introduces significant delays; adopting a robust control method is more effective [23]. Researchers have proposed some improved disturbance observers such as the Luenberger observer [24], sliding mode observer [25], and generalized proportional-integral observer [26] to observe disturbances caused by parameter mismatch. An inductance estimation method based on an adjustable model is designed in article [27], which can quickly estimate the value of inductance. However, the calculation process requires motor speed and the sliding mode observation of the motor speed requires the inductance of the motor, making it unsuitable for direct application in sensorless observation schemes. Article [28] proposes an online correction method for parameter bias in sensorless observation based on the least squares method, but the computational complexity involved in the calculation is high, and it requires high-precision parameter accuracy.

2. Methodology of the Research

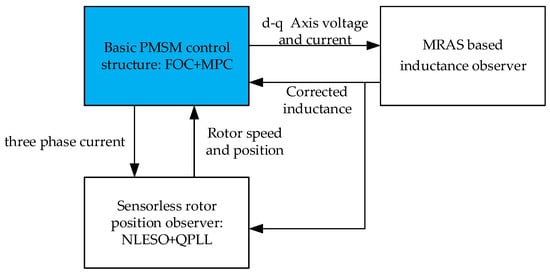

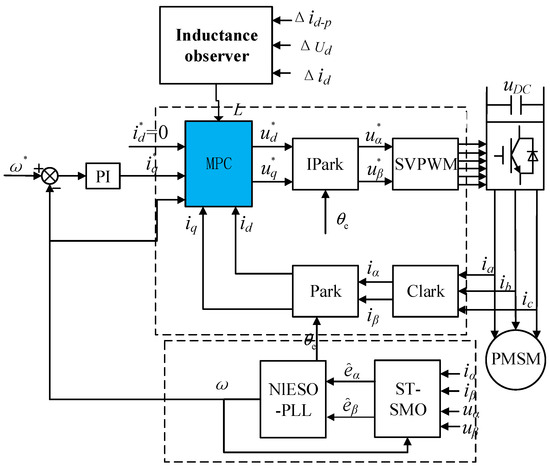

This paper primarily improves the existing method in two aspects: lower delay sensorless control and parameter robustness. A position observation and a parameter estimation system for model predictive control are proposed to address the issues of observation delay in sliding mode observers and sensorless motor parameter identification. Based on incremental model predictive control, a nonlinear super-twisting sliding mode observer (STSMO) is utilized to observe the back electromotive force during the model predictive control calculation period. A nonlinear extended state observer-based quadrature phase-locked loop (NLESO-QPLL) is designed to suppress high-frequency disturbances in the system and eliminate ramp response errors, replacing the low-pass filter to reduce the observation delay of the motor rotor position. The calculations of the STSMO and NLESO-QPLL converge within the MPC control interval to ensure real-time observation. Finally, based on the principle of the model reference adaptive system (MRAS), an iterative inductance observer is designed to correct the inductance parameter, and the inductance observation results are applied back to MPC and sliding mode observers to complete sensorless robust control of the motor. The structure of the methodology is shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Three main modules and the data flow between them.

2.1. Model of MPC and STSMO

This section mainly introduces the basic models of motor current control, which have been previously reported in the literature. The classic FOC employs the PARK transformation (Equation (1)) to convert the collected three-phase currents into currents in the stationary coordinate system. Subsequently, it utilizes the CLARK transformation (Equation (2)) to rotate and transform into flux linkage current and torque current .

In article [5], scholars have proposed an incremental formula for MPC; it uses the measured current increment , to predict the current increment , at the next moment:

In Equation (3), is sample time, is motor resistance, is motor inductance, and is rotor speed. When the prediction horizon is 1 and the d-axis current controlled to be 0, the optimal control output , at this time is as follows:

Then, the principle of STSMO is analyzed. The mathematical model of the PMSM in the α β coordinate system is as follows:

In this formula, represent the voltage components on the α-β axis; and represent the back voltage components on the α-β axis, and they contain the information of rotor position. The formula is as follows:

represents the rotational speed, represents the flux linkage, and represents the position of rotor. ,, representing the measurement deviation of current on the α-β axis.

Based on the super-twisting sliding mode theory, the back-EMF observer is designed as Equations (7) and (8). Due to the significant difference between the maximum and minimum values of the system signals, the hyperbolic tangent function is employed to process the observed signals to mitigate chattering. The expression of the observer is as follows:

2.2. Model of Improved QPLL

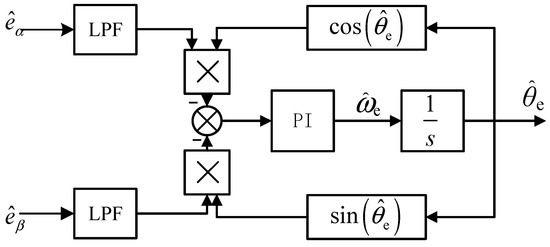

Back-EMF observation is always affected by random disturbances and computational accuracy perturbations, resulting in noise in the results. The traditional approach is to first perform low-pass filtering (LPF) on the observation results and then employ a QPLL to extract position information. However, in this process, the low-pass filter introduces system delay, and the PI-based QPLL structure can also lead to inaccurate observation results.

The block diagram of the traditional QPLL system is shown in Figure 2. Its basic principle is illustrated in Equation (9), where E represents the amplitude of the back electromotive force. First, a sine signal of the rotor position error is obtained through quadrature calculation. When the rotor position error is tiny, we can approximately assume . Through a PI regulator, the rotor position estimation error is adjusted to 0, and the output of the PI controller is the estimated speed. The estimated rotor position is obtained through an integrator.

Figure 2.

Traditional LPF-QPLL structure.

When the speed of the PMSM undergoes a ramp change with an acceleration of , the expression for the rotor angle after Laplace transformation is . According to the final value theorem, the expression for the steady-state error of the QPLL at this time is as follows:

When the speed of a PMSM undergoes a ramp change, the PI-based QPLL cannot achieve zero steady-state-error rotor tracking.

Using the expansion state variable to represent the differential of the electrical angle acceleration, which represents the unknown disturbance affecting the change in angular acceleration, the mathematical model of PMSM dynamics can be re-expressed as follows:

Define the state vector as follows:

Using the basic theory of the extended state observer, construct a third-order linear ESO system using the following equation:

In the formula, ,, and are the error gain coefficients. The error variables are as follows:

The following is a proof showing that the observation is an unbiased estimate:

Differentiating Equation (14) and substituting Equations (13) and (11) into it, we can obtain the following:

By applying the Laplace transform to Equation (15), we can obtain the following:

According to Equation (16), the transfer function of rotor position estimation can be obtained as follows:

According to the final value theorem, the steady-state error of the system’s ramp response is as follows:

From Equation (18), it is clear that when the motor speed changes in a ramp manner, the rotor position can achieve zero steady-state-error tracking after using the ESO. To ensure the stability of the system, it is necessary to ensure that all poles of Equation (18) are located in the negative half-axis region. If the three poles of the observer are set to be , then the desired characteristic equation is as follows:

From the transfer function of the system, it can be observed that the ESO system possesses low-pass filtering capability. When ω is large, the convergence speed is fast, but the random errors will be amplified, and when the value is small, it is exactly the opposite.

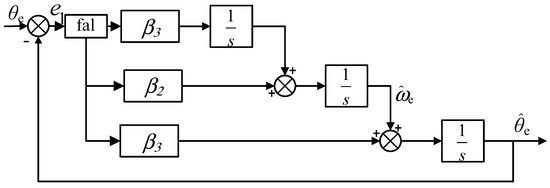

Simulation results of ESO show that sudden fluctuations have a significant impact on the system. From the ADRC theory, replace the direct error in the ESO with a nonlinear function. This approach magnifies small errors and limits large ones, so it can suppress high-frequency noise to a certain extent, and does not affect the convergence of the system. The final NLESO expression is the following:

The structure of the nonlinear extended state observer is shown in Figure 3:

Figure 3.

Structure of NLESO.

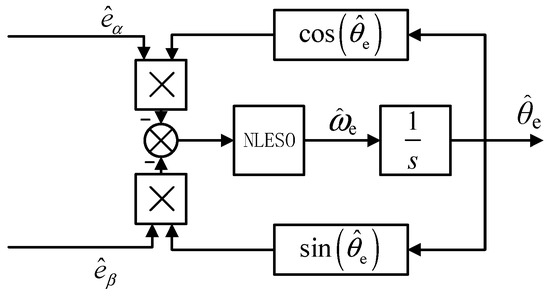

Finally, as shown in Figure 4, we can obtain the structure of the improved QPLL:

Figure 4.

Improved NLESO-QPLL structure.

2.3. Model of Iterative Inductance Observer

In the control of a motor, the change in rotor position of the motor is much slower than the change in current speed. Assume that within the calculation interval of MPC, the system’s speed variation is minimal. Based on the principle of MRAS, an iterative inductance observation function is designed:

In the above formula, represents the predicted current increment, and the calculated formula is as follows:

denotes the actual current increment on the d-axis, is the value of at moment k, is sample time of MPC, and is the inductance measured currently; is a weighting factor, set to to ensure that the two terms are on the same order of magnitude.

When approaches 0, it indicates that the predicted current increment is very close to the actual current increment and is close to the actual motor parameters. According to the extreme value condition of Equation (22), , we can obtain the extreme value solution as follows:

With the initial condition, we can calculate the result of Equation (20) and take it into Equation (21), and utilize the result of Equation (21) in the next measurement of the rotor position. With this circle, we can reduce the error of L to an acceptable range.

The following proves the stability of the proposed inductance observer. Consider the prediction formula of :

Defining , and substituting (4) into (25), we can obtain the following:

Substitute Equation (24) into this, and simplify through order of magnitude analysis:

Since can be considered essentially constant, and the control objective is , the last term in Equation (27) is regarded as a small disturbance. By performing a z-transform on (28), the transfer function between and can be obtained as follows:

From the basic properties of this transfer function, it can be observed that as long as remains , the system will be stable.

3. Simulation Experiment

The overall controller structure obtained from the article is shown in Figure 5. The dotted box above containing MPC and FOC is the basic PMSM current control module. The dotted box below contains the NLESO and STSMO combined as the sensorless rotor position measurement module, and the inductance observer employs the method proposed in Section 2.3, aiming to correct the resistance parameters in the MPC module. The parameters marked with an asterisk represent reference values.

Figure 5.

Overall motor controller structure.

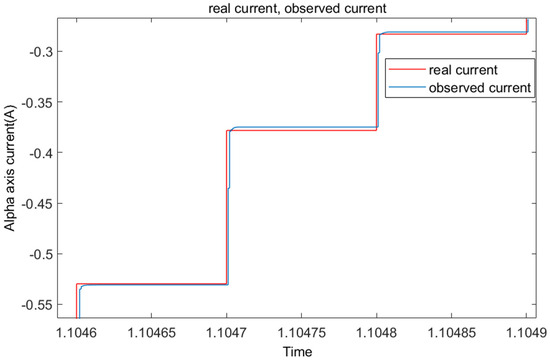

In this system, the calculated frequency of MPC and the inductance observer is Hz, and the calculated frequency of the STSMO and NLESO-QPLL is Hz to ensure the STSMO can converge within the interval of MPC. As shown in Figure 6, after 10 iterations, the current observed by the STSMO is close to the real current, which means it achieves convergence. Considering the convergence time of the STSMO, this interval can be reduced to 10 times the MPC frequency at most, which is Hz.

Figure 6.

Convergence curve of STSMO: actual current and observed current.

Due to the poor performance of the sliding mode observer at low speeds, the motor speed output is used during the startup phase. After the system completes startup within 0.5 s, the output of the improved quadrature phase-locked loop is switched to be the input of the MPC. The target state is set as follows: the reference speed is 30 rad/s in 0–0.6 s and 150 rad/s in 0.6–2 s to simulate the performance at different speeds. The external input torque is 0.1 N·m in 0–1 s and 2.5 N·m to test the proposed method at different loads. To verify the function of the module, the known inductance is changed to 0.6 times the nominal value at 0.5 s, and to 1.5 times the actual value at 1.2 s.

The main parameters of the motor in the simulation model are shown in Table 1. Most parameters of the system come from manually adjusting the parameters and observing the response results.

Table 1.

Real values for parameters of the surface-mounted PMSM.

Under these conditions, through comparison and improvement, the coefficients in Equations (7) and (8) are determined to be as follows:

taking into account both error and convergence speed, and with ω = 160. The coefficient in Equation (20) is as follows:

Adjusting the parameter in Equation (21) considering the results of simulation, the coefficient is as follows:

To better demonstrate the research findings of this paper, the method used in article [25] is reproduced in this paper. This paper employs an ESO-based rotor position error compensation method for comparison with the method used in this paper. For convenience, the method used in that paper is denoted as ESO + LPF. To verify the effectiveness of the method for estimating motor parameters, this paper replicates the recursive least squares (RLS) algorithm used in article [28]. The specific simulink model can be downloaded in the supplementary materials.

First, test the proposed method for improving observation delay. Since using LPF will result in unavoidable phase delay, compare the difference between observed and actual rotor positions. The first-order LPF is defined as follows:

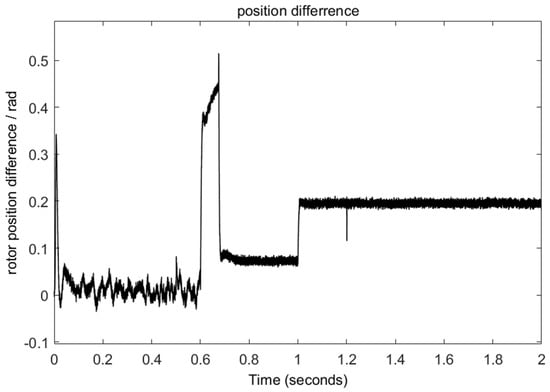

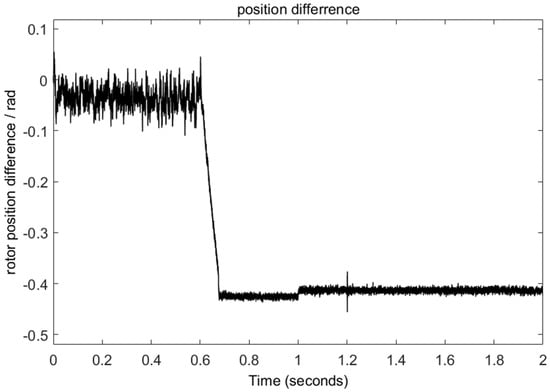

The comparison of rotor position errors is presented in Figure 7 and Figure 8. When using LPF + ESO, the difference is about 0.1 rad at low-speed conditions, 0.48 rad at high-speed, low-load conditions, and 0.47 rad at high-speed, high-load conditions. When using the NLESO, the difference is about 0.018 rad at low speed, 0.083 rad at high-speed, low-load conditions, and 0.205 rad at high-speed, high-load conditions. These results demonstrate that the proposed method can reduce the delay in rotor position estimation. Although the error value increases under high-load conditions, it is still smaller than using LPF.

Figure 7.

Rotor position estimation error using NLESO.

Figure 8.

Rotor position estimation error using ESO + LPF.

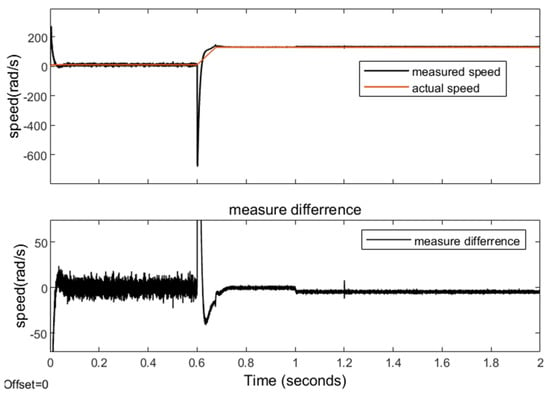

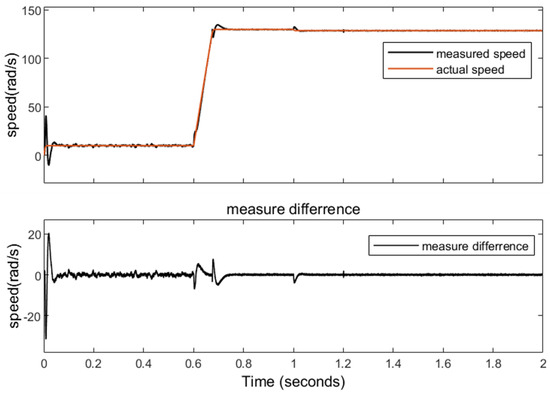

Then, verify the improvement of the quadrature phase-locked loop using an NLESO. Compare the speed observation results using the ESO, LPF + ESO, and NLESO. The results are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. Figure 9 presents the results of using an ESO without LPF. At low-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.004 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.3 rad/s. At high-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.004 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.3 rad/s. At high-speed, high-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.004 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.3 rad/s. The results indicate that employing an ESO without LPF not only induces significant chattering but also leads to a large overshoot during speed transients and a steady-state error after torque application.

Figure 9.

Results of speed measurement with an ESO but without LPF.

Figure 10.

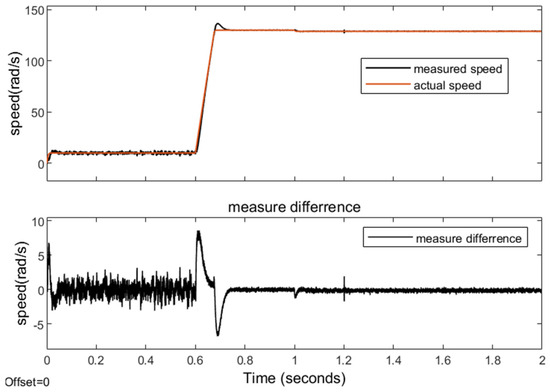

Results of speed measurement with LPF + ESO.

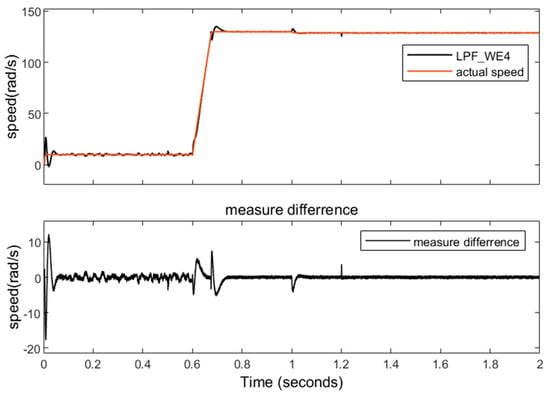

Figure 11.

Results of speed measurement with an NLESO.

The results of using LPF + ESO are shown in Figure 10. At low-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.0049 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.7 rad/s. At high-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.02 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.1 rad/s. At high-speed, high-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.14 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.18 rad/s. After using a low-pass filter, the error in observation results has been reduced in various situations, and the fluctuation in observation results during speed changes has also been significantly reduced.

The results of using an NLESO are shown in Figure 11. At low-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.006 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.56 rad/s. At high-speed, low-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.066 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.25 rad/s. At high-speed, high-load conditions, the mean of the difference is 0.052 rad/s, and the mean absolute error is 0.24 rad/s. Both LPF + ESO and the NLESO eliminate the ramp error, and their results are similar at high speeds. The NLESO shows 20–30% reduction in mean absolute error at low speeds. This confirms that the nonlinear function in the NLESO provides similar noise suppression without sacrificing dynamic response compared to LPF.

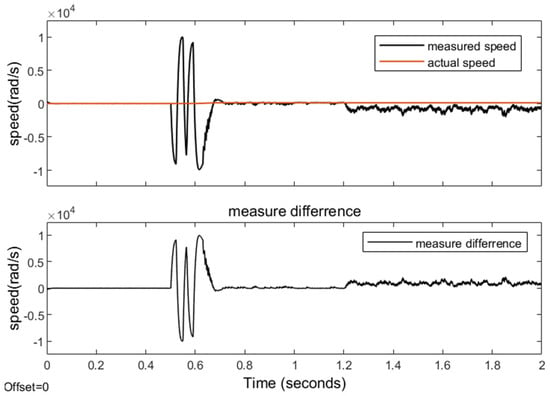

Temperature primarily affects the resistance, inductance, and flux linkage of the motor. Finally, verify the results of inductance observation. The results of not using an inductance observer are shown in Figure 12. In comparison with Figure 11, it is evident that at 0.5 s and 1.2 s, parameter variations significantly impact the speed measurement accuracy due to calculation errors; the estimated speed exhibits oscillations and fails to achieve precise tracking performance. No matter whether the inductance becomes larger or smaller, the speed observation results are unacceptable. With the inductance observer, the speed estimation error is reduced greatly, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed observer.

Figure 12.

Results of speed measurement without an inductance observer.

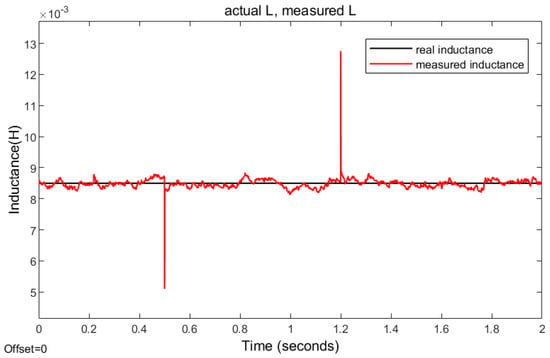

Figure 13 shows the observation results of the inductance estimator during a sudden change in inductance. At 0.5 s, the known inductance was suddenly changed to 0.6 times its nominal value and adjusted back to the actual value. At 1.2 s, the known inductance was changed to 1.5 times its nominal value and adjusted back to the actual value within 0.01 s. It can be observed that, regardless of whether the inductance increases or decreases and whether the load is high or low, the inductance observer can correct it to a value close to the actual inductance.

Figure 13.

Output of the inductance observer when the inductance changes.

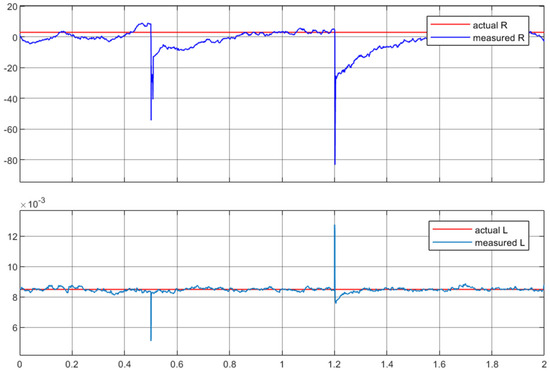

Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the simulation results of RLS. It can be observed that when using the comparison method, a fast estimation of the motor state can also be achieved, and the observation results are very close to those obtained using the MRAS method proposed in this paper. At the same time, the inductance observation curve has almost no deviation. Analysis of the resistance estimation results indicates that this method fails to achieve effective resistance correction under our specific experimental conditions. However, even if the resistance parameter changes significantly, it will not have a significant impact on the rotor position estimation. In this model, even if the resistance doubles, the impact on the results can be almost negligible. This also proves that the method proposed in this article is more concise.

Figure 14.

Results of speed measurement with RLS.

Figure 15.

Results of resistance and inductance measurement with RLS.

From the simulation above, the simulation results indicate that the incremental model predictive control generates significant high-frequency noise, and inaccurate inductance will lead to inaccurate speed measurement. After improving the method with an NLESO-QPLL and iterative inductance observer, the results show that the high-frequency noise has been well suppressed by the NLESO. Both theory and simulation demonstrate that parameter mismatch can seriously affect the results of sensorless observation, while the use of the designed inductance observer can significantly reduce its impact.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Key Findings

To meet the requirements of low delay and robust control for PMSM sensorless control, this study proposes an integrated scheme combining an STSMO, NLESO-QPLL, and MRAS-based inductance observer. Simulation results confirm that the proposed method achieves robust sensorless control of the PMSM. Through comparative experiments with methods proposed in other papers studying sensorless control, it is also demonstrated that the method proposed in this paper is more compatible with the incremental model predictive control FOC method, and the inductance parameter correction method exhibits strong robustness.

Existing methods have proposed using an extended state observer and a low-pass filter to improve sensorless position tracking results for rotors. Considering that the transfer function of the extended state observer has the ability to suppress high-frequency noise, this paper proposes using a nonlinear function to process the error signal of the extended state observer, thereby suppressing the overshoot during state changes and the large oscillations during stabilization. The results are compared in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, demonstrating that removing the low-pass filter can significantly reduce the observation delay, and using a nonlinear module can also achieve noise suppression effects close to those achieved with the low-pass filters.

Currently, researchers have proposed using an MRAS-based inductance observer in sensor-based motor control systems to mitigate the impact of sudden changes in motor parameters, and this research extended it into the sensorless control field. Based on the condition where the initial speed is known, this paper extends this observer to the sensorless domain using an iterative approach, and verifies the correction capability of the inductance observer and its enhancement of control robustness through simulation.

4.2. Limitations and Future Work

The conclusions of this paper are primarily based on theoretical derivation and simulation, with data sampling and computation assuming ideal conditions. However, the process noise encountered in actual experiments may be greater than that in simulations. Additionally, the FOC used in this paper does not incorporate improved dead-zone control, which can lead to discrepancies between actual output and theoretical derivation due to the inverter in actual motor control. Currently, we are developing an actual experimental control platform based on FPGA to further verify the theory.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://github.com/threeshaw/incMPC_STSMO_QPLL_MRAS.git (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; Methodology, S.X. and Z.Y.; Software, S.X.; Validation, S.X.; Investigation, S.X.; Data curation, S.X.; Writing–original draft, S.X.; Writing–review & editing, S.X. and Z.Y.; Supervision, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Model predictive current control for PMSM drives with parameter robustness improvement. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, A.; Kanchan, R.; Stolze, P.; Kennel, R. Model-Based Predictive Control of Electric Drives; Cuvillier Verlag: Lower Saxony, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Holtz, J. Predictive finite-state control—When to use and when not. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 4225–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo, J.L.; Olloqui, A.; Rivera, M.; Macias, M.E.; Probst, O.; Micheloud, O.M.; Rodriguez, J. Model-based predictive rotor current control for grid synchronization of a DFIG driven by an indirect matrix converter. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2014, 2, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, Y.W.; Zargari, N.R. Discrete-time SMO sensorless control of current source converter-fed PMSM drives with low switching frequency. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 2120–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Luo, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhang, X. Robust model predictive control for a three-phase PMSM motor with improved control precision. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 838–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.L.; Li, Y.C.; Li, Z.X.; Zhu, J.H. Research on sensorless control of PMSM based on novel double- sliding mode MRAS. IEICE Electron. Express 2024, 21, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J. An improved Q-PLL to overcome the speed reversal problems in sensorless PMSM drive. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC-ECCE Asia), Hefei, China, 22–26 May 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1884–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Yao, X. An enhanced SMO-based permanent-magnet synchronous machine sensorless drive scheme with current measurement error compensation. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2020, 9, 4407–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Lai, C.; Iyer, K.L.V. A review of sliding mode observer based sensorless control methods for PMSM drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 11352–11367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Son, J.; Lee, J. A high-speed sliding-mode observer for the sensorless speed control of a PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 58, 4069–4077. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Sun, S.; Liu, A.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, K. Robustness improvement of model-based sensorless SPMSM drivers based on an adaptive extended state observer and an enhanced quadrature PLL. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 4802–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, N.N.; Fan, L.; Zhang, Z. Sensorless PMSM Control with Sliding Mode Observer Based on Sigmoid Function. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Akbari, H.; Mousavi, S.; Beheshtipour, Z. Design of an adaptive terminal sliding mode to control the PMSM chaos phenomenon. Syst. Sci. Control. Eng. 2023, 11, 2207593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Q.; Huang, D.Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.Y. Deadbeat Predictive Speed Control of PMSM via Enhanced Low-Gain Disturbance Observer Design and Inertia Identification. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2524–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, O.; Khlaief, A.; Abassi, M.; Chaari, A.; Boussak, M. Position sensorless vector control of PMSM drives based on SMO. In Proceedings of the 2015 16th International Conference on Sciences and Techniques of Automatic Control and Computer Engineering (STA), Monastir, Tunisia, 21–23 December 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 545–550. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, Z.; Novak, M. Adaptive PLL-based sensorless control for improved dynamics of high-speed PMSM. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 10154–10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Xiong, S. Adaptive robust sensorless control for PMSM based on super-twisting algorithm back EMF observer and extended state observer. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 9295–9307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Gu, J.; Yu, Y. Resolver-to-Digital conversion based on enhanced single degree-of-freedom ADRC for acceleration position error suppression in PMSM drives. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 11, 7184–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, C.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Lee, C.H.T. Enhanced Position Estimation Accuracy Based on Improved Super-Twisting Observer and Position Compensation PLL for PMSM Sensorless Control. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 72, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R.; Chen, J.; Hu, P.; Li, J. Optimizing Sensorless Control in PMSM Based on the SOGIFO-X Flux Observer Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; He, L. FPGA-based predictive speed control for PMSM system using integral sliding-mode disturbance observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Davari, S.A.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Khaburi, D.A.; Rodrieguez, J.; Kennel, R. Finite control set model predictive torque control of induction machine with a robust adaptive observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 64, 2631–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, F.X.; Wang, J.X.; Rodríguez, J. Zynq Implemented Luenberger Disturbance Observer Based Predictive Control Scheme for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 1770–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Luo, H.; Yin, Q. Position Error Compensation Strategy for PMSM Without Position Sensor Based on Extended State Observer. In Proceedings of the 2025 44th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Chongqing, China, 28–30 July 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y. Robust model predictive current control based on inductance and flux linkage extraction algorithm. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 14893–14902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Y. A Simple Motor-Parameter-Free Model Predictive Current Control for PMSM Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 3292–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghlache, A.; Djerioui, A.; Mekki, H.; Zeghlache, S.; Benkhoris, M.F. Robust Sensorless PMSM Control with Improved Back-EMF Observer and Adaptive Parameter Estimation. Electronics 2025, 14, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.