Comparison of Classifier Calibration Schemes for Movement Intention Detection in Individuals with Cerebral Palsy for Inducing Plasticity with Brain–Computer Interfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Setup

2.3. Recordings

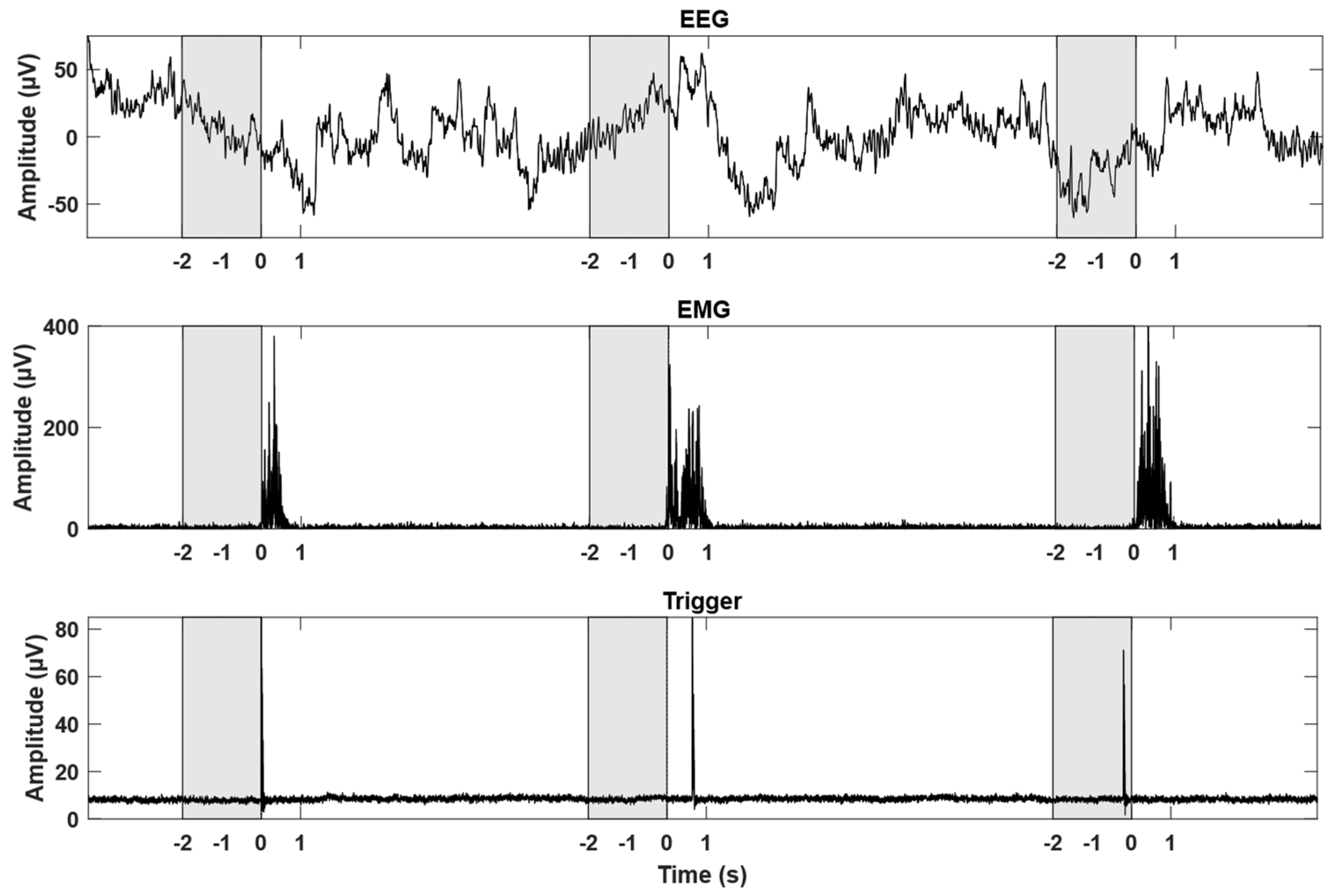

2.4. EMG Onset Detection and Pre-Processing

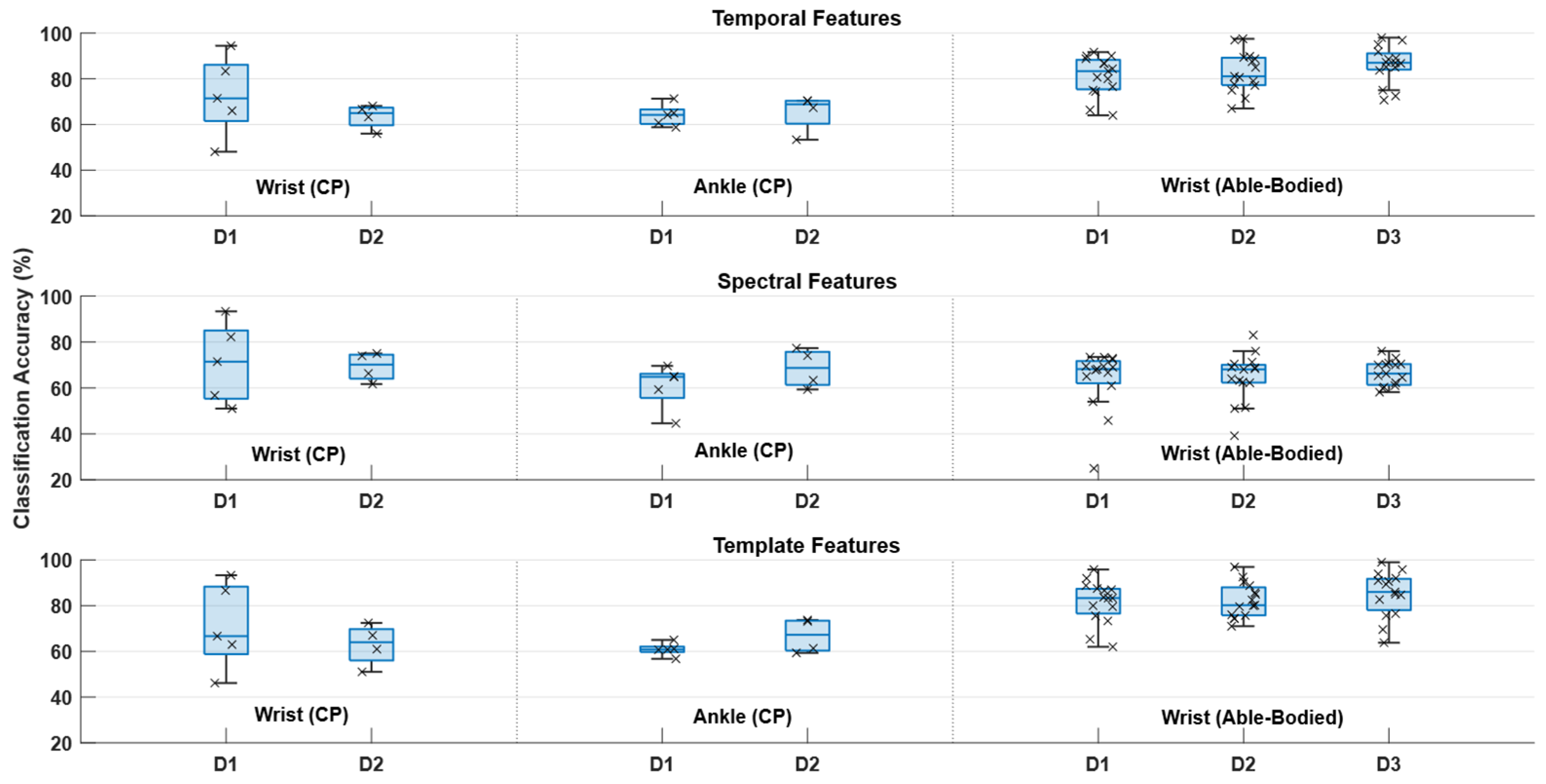

2.5. Feature Extraction

2.6. Classification Scenarios

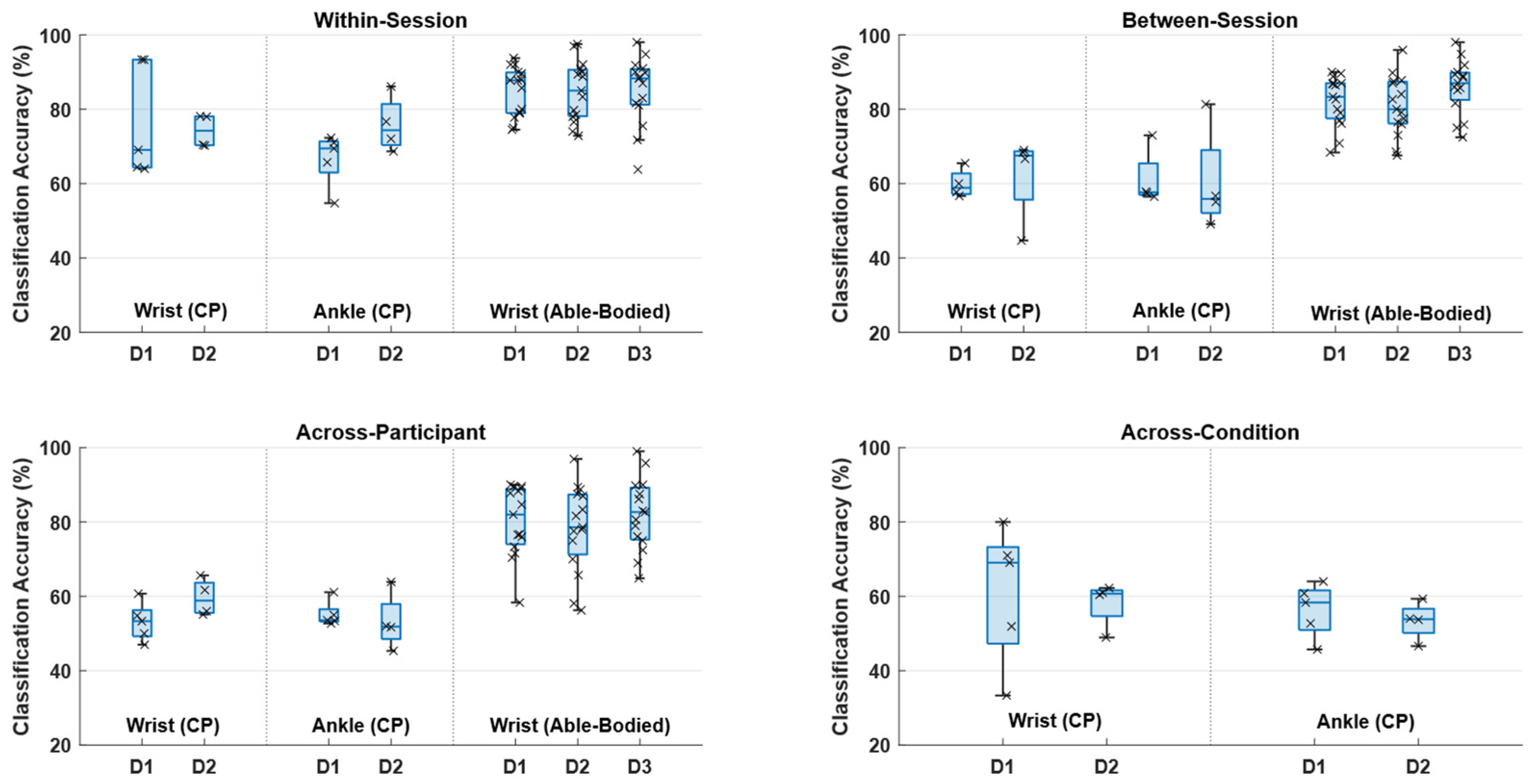

2.6.1. Within-Session

2.6.2. Between-Session

2.6.3. Across-Participant

2.6.4. Across-Condition

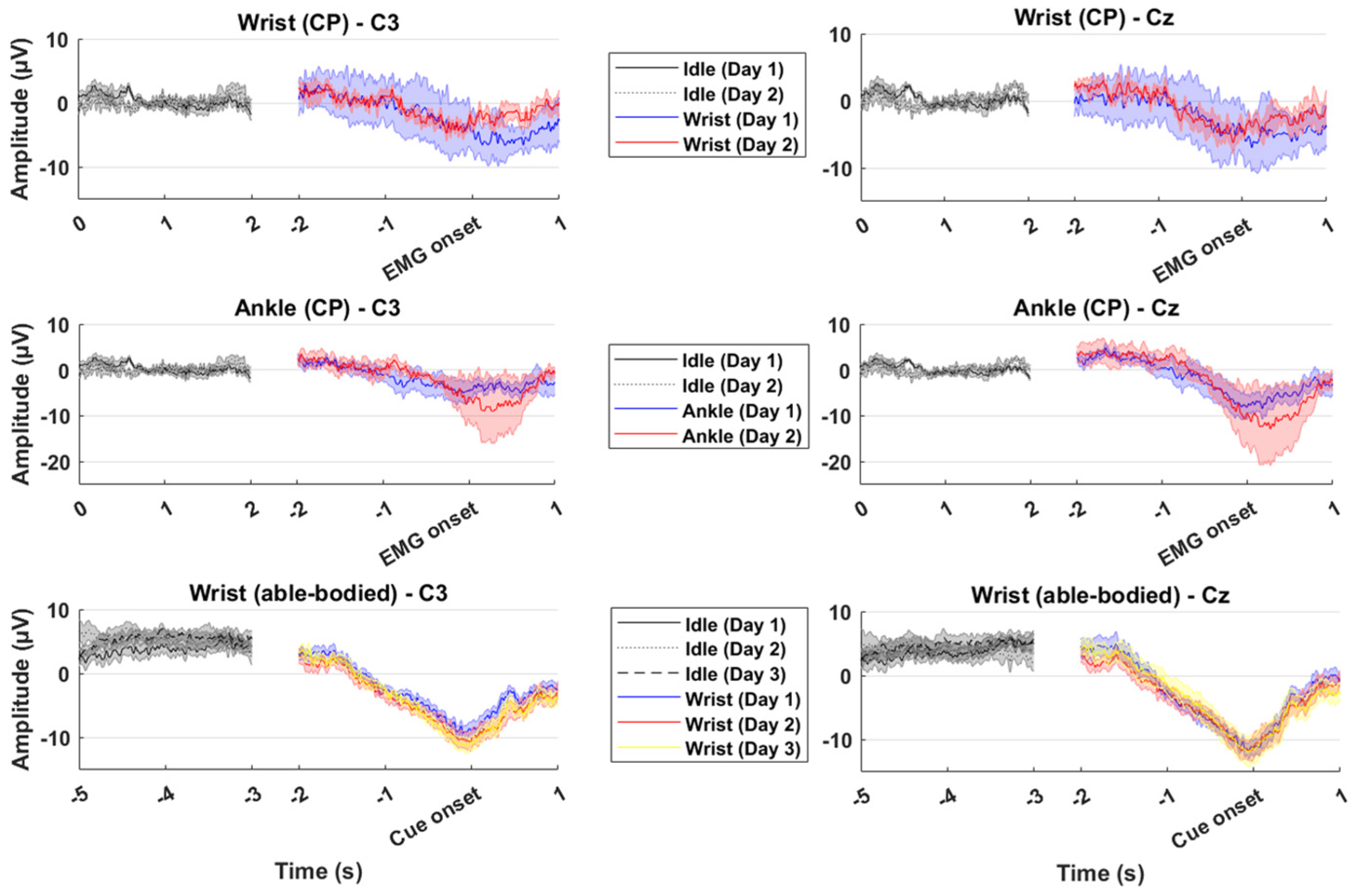

2.7. Feature Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| CP | Cerebral Palsy |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ERD | Event-Related Desynchronization |

| MRCP | Movement-Related Cortical Potential |

References

- Wolpaw, J.R.; Birbaumer, N.; McFarland, D.J.; Pfurtscheller, G.; Vaughan, T.M. Brain-computer interfaces for communication and control. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2002, 113, 767–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán, J.R.; Rupp, R.; Müller-Putz, G.R.; Murray-Smith, R.; Giugliemma, C.; Tangermann, M.; Vidaurre, C.; Cincotti, F.; Kübler, A.; Leeb, R.; et al. Combining brain–computer interfaces and assistive technologies: State-of-the-art and challenges. Front. Neurosci. 2010, 4, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasiucci, A.; Leeb, R.; Iturrate, I.; Perdikis, S.; Al-Khodairy, A.; Corbet, T.; Schnider, A.; Schmidlin, T.; Zhang, H.; Bassolino, M. Brain-actuated functional electrical stimulation elicits lasting arm motor recovery after stroke. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervera, M.A.; Soekadar, S.R.; Ushiba, J.; Millán, J.d.R.; Liu, M.; Birbaumer, N.; Garipelli, G. Brain-computer interfaces for post-stroke motor rehabilitation: A meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2018, 5, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse-Wentrup, M.; Mattia, D.; Oweiss, K. Using brain-computer interfaces to induce neural plasticity and restore function. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8, 025004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, I.K.; Navid, M.S.; Rashid, U.; Amjad, I.; Olsen, S.; Haavik, H.; Alder, G.; Kumari, N.; Signal, N.; Taylor, D. Associative cued asynchronous BCI induces cortical plasticity in stroke patients. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Leone, A.; Dang, N.; Cohen, L.G.; Brasil-Neto, J.P.; Cammarota, A.; Hallett, M. Modulation of muscle responses evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation during the acquisition of new fine motor skills. J. Neurophysiol. 1995, 74, 1037–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrachacz-Kersting, M.; Jiang, N.; Stevenson, A.J.T.; Niazi, I.K.; Kostic, V.; Pavlovic, A.; Radovanović, S.; Djuric-Jovicic, M.; Agosta, F.; Dremstrup, K.; et al. Efficient neuroplasticity induction in chronic stroke patients by an associative brain-computer interface. J. Neurophysiol. 2016, 115, 1410–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L.B.; Rose, S.E.; Boyd, R.N. Rehabilitation and neuroplasticity in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, B. Clinical usefulness of brain-computer interface-controlled functional electrical stimulation for improving brain activity in children with spastic cerebral palsy: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2491–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadavji, Z.; Kirton, A.; Metzler, M.J.; Zewdie, E. BCI-activated electrical stimulation in children with perinatal stroke and hemiparesis: A pilot study. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1006242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobrov, P.D.; Biryukova, E.V.; Polyaev, B.A.; Lajsheva, O.A.; Usachjova, E.L.; Sokolova, A.V.; Mihailova, D.I.; Dement’Eva, K.N.; Fedotova, I.R. Rehabilitation of patients with cerebral palsy using hand exoskeleton controlled by brain-computer interface. Bull. Russ. State Med. Univ. 2020, 4, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi, A.; Kline, J.; Gravunder, A.; Phillips, C.; Parker, S.M.; Damiano, D.L. Development and evaluation of a BCI-neurofeedback system with real-time EEG detection and electrical stimulation assistance during motor attempt for neurorehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1346050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, I.K.; Kersting, N.M.; Jiang, N.; Dremstrup, K.; Farina, D. Peripheral Electrical Stimulation Triggered by Self-Paced Detection of Motor Intention Enhances Motor Evoked Potentials. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2012, 20, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochumsen, M.; Navid, M.S.; Rashid, U.; Haavik, H.; Niazi, I.K. EMG-versus EEG-Triggered Electrical Stimulation for Inducing Corticospinal Plasticity. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2019, 27, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Jiang, N.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Lin, C.; Asin, G.; Moreno, J.; Pons, J.; Dremstrup, K.; Farina, D. A Closed-Loop Brain-Computer Interface Triggering an Active Ankle-Foot Orthosis for Inducing Cortical Neural Plasticity. Biomed. Eng. IEEE Trans. 2014, 20, 2092–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Jochumsen, M.; Cremoux, S.; Robinault, L.; Lauber, J.; Arceo, J.; Navid, M.; Nedergaard, R.; Rashid, U.; Haavik, H.; Niazi, I. Investigation of Optimal Afferent Feedback Modality for Inducing Neural Plasticity with A Self-Paced Brain-Computer Interface. Sensors 2018, 18, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, H.; Hallett, M. What is the Bereitschaftspotential? Clin. Neurophysiol. 2006, 117, 2341–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfurtscheller, G.; Da Silva, F.L. Event-related EEG/MEG synchronization and desynchronization: Basic principles. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 1842–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Kristensen, S.R.; Niazi, I.K.; Farina, D. Precise temporal association between cortical potentials evoked by motor imagination and afference induces cortical plasticity. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Fong, M.; Murphy, B.A.; Sinkjaer, T. Changes in excitability of the cortical projections to the human tibialis anterior after paired associative stimulation. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 97, 1951–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis-Escalante, T.; Müller-Putz, G.; Pfurtscheller, G. Overt foot movement detection in one single Laplacian EEG derivation. J. Neurosci. Methods 2008, 175, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, E.; Chavarriaga, R.; Silvoni, S.; Millán, J.R. Detection of self-paced reaching movement intention from EEG signals. Front. Neuroeng. 2012, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochumsen, M.; Niazi, I.K.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Farina, D.; Dremstrup, K. Detection and classification of movement-related cortical potentials associated with task force and speed. J. Neural Eng. 2013, 10, 056015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, I.K.; Jiang, N.; Tiberghien, O.; Nielsen, J.F.; Dremstrup, K.; Farina, D. Detection of movement intention from single-trial movement-related cortical potentials. J. Neural Eng. 2011, 8, 066009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, R.; Jiang, N.; Lin, C.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Dremstrup, K.; Farina, D. Enhanced Low-latency Detection of Motor Intention from EEG for Closed-loop Brain-Computer Interface Applications. Biomed. Eng. IEEE Trans. 2013, 61, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, J.; Serrano, J.I.; Del Castillo, M.D.; Monge-Pereira, E.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Alguacil-Diego, I.; Pons, J.L. Detection of the onset of upper-limb movements based on the combined analysis of changes in the sensorimotor rhythms and slow cortical potentials. J. Neural Eng. 2014, 11, 056009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochumsen, M.; Niazi, I.K.; Taylor, D.; Farina, D.; Dremstrup, K. Detecting and classifying movement-related cortical potentials associated with hand movements in healthy subjects and stroke patients from single-electrode, single-trial EEG. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 056013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochumsen, M.; Niazi, I.K.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Jiang, N.; Farina, D.; Dremstrup, K. Comparison of spatial filters and features for the detection and classification of movement-related cortical potentials in healthy individuals and stroke patients. J. Neural Eng. 2015, 12, 056003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofner, P.; Schwarz, A.; Pereira, J.; Wyss, D.; Wildburger, R.; Müller-Putz, G.R. Attempted Arm and Hand Movements can be Decoded from Low-Frequency EEG from Persons with Spinal Cord Injury. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Larraz, E.; Montesano, L.; Gil-Agudo, A.; Minguez, J. Continuous decoding of movement intention of upper limb self-initiated analytic movements from pre-movement EEG correlates. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, A.; Aliakbaryhosseinabadi, S.; Blicher, J.; Farina, D.; Mrachacz-Kersting, N.; Dosen, S. Online control of an assistive active glove by slow cortical signals in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neural Eng. 2021, 18, 046085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jochumsen, M.; Petersen, B.S.; Vestergaard, L.M.; Falborg, N.F.; Wisler, L.; Olesen, M.V.; Andersen, M.S.; Sørensen, N.B.; Jørgensen, S.T. Detection of movement-related cortical potentials associated with upper and low limb movements in patients with multiple sclerosis for brain-computer interfacing. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 046026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.S.; Shiels, T.A.; Lin, C.S.; John, S.E.; Grayden, D.B. Decoding imagined movement in people with multiple sclerosis for brain–computer interface translation. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 016012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.S.; Shiels, T.A.; Lin, C.S.; John, S.E.; Grayden, D.B. Feasibility of source-level motor imagery classification for people with multiple sclerosis. J. Neural Eng. 2025, 22, 026020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochumsen, M.; Poulsen, K.B.; Sørensen, S.L.; Sulkjær, C.S.; Corydon, F.K.; Strauss, L.S.; Roos, J.B. Single-trial movement intention detection estimation in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A movement-related cortical potential study. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 046036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochumsen, M.; Shafique, M.; Hassan, A.; Niazi, I.K. Movement intention detection in adolescents with cerebral palsy from single-trial EEG. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 15, 066030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, I.; Billinger, M.; Laparra-Hernandez, J.; Aloise, F.; Garcia, M.L.; Faller, J.; Scherer, R.; Muller-Putz, G. On the control of brain-computer interfaces by users with cerebral palsy. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Billinger, M.; Wagner, J.; Schwarz, A.; Hettich, D.T.; Bolinger, E.; Garcia, M.L.; Navarro, J.; Müller-Putz, G. Thought-based row-column scanning communication board for individuals with cerebral palsy. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuper, C.; Muller, G.R.; Kubler, A.; Birbaumer, N.; Pfurtscheller, G. Clinical application of an EEG-based brain-computer interface: A case study in a patient with severe motor impairment. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2003, 114, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherian, S.; Selitskiy, D.; Pau, J.; Davies, T.C.; Owens, R.G. Training to use a commercial brain-computer interface as access technology: A case study. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2016, 11, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherian, S.; Selitskiy, D.; Pau, J.; Claire Davies, T. Are we there yet? Evaluating commercial grade brain–computer interface for control of computer applications by individuals with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochumsen, M.; Knoche, H.; Kidmose, P.; Kjær, T.W.; Dinesen, B.I. Evaluation of EEG Headset Mounting for Brain-Computer Interface-Based Stroke Rehabilitation by Patients, Therapists, and Relatives. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jochumsen, M.; Niazi, I.K.; Nedergaard, R.W.; Navid, M.S.; Dremstrup, K. Effect of subject training on a movement-related cortical potential-based brain-computer interface. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2018, 41, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Larraz, E.; Ibáñez, J.; Trincado-Alonso, F.; Monge-Pereira, E.; Pons, J.L.; Montesano, L. Comparing recalibration strategies for electroencephalography-based decoders of movement intention in neurological patients with motor disability. Int. J. Neural. Syst. 2018, 28, 1750060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, U.; Niazi, I.K.; Signal, N.; Farina, D.; Taylor, D. Optimal automatic detection of muscle activation intervals. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2019, 48, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiro, T.M.; Perez, P.S.; Baranauskas, J.A. How many trees in a random forest? Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference, MLDM 2012, Berlin, Germany, 13–20 July 2012; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 154–168. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, I.; Faller, J.; Scherer, R.; Sweeney-Reed, C.M.; Nasuto, S.J.; Billinger, M.; Müller-Putz, G.R. Exploration of the neural correlates of cerebral palsy for sensorimotor BCI control. Front. Neuroeng. 2014, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadavji, Z.; Zhang, J.; Paffrath, B.; Zewdie, E.; Kirton, A. Can Children with Perinatal Stroke Use a Simple Brain Computer Interface? Stroke 2021, 52, 2363–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A.; Brandstetter, J.; Pereira, J.; Müller-Putz, G.R. Direct comparison of supervised and semi-supervised retraining approaches for co-adaptive BCIs. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2019, 57, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarriaga, R.; Sobolewski, A.; Millán, J.d.R. Errare machinale est: The use of error-related potentials in brain-machine interfaces. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Putz, G.R.; Kaiser, V.; Solis-Escalante, T.; Pfurtscheller, G. Fast set-up asynchronous brain-switch based on detection of foot motor imagery in 1-channel EEG. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2010, 48, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Putz, G.R.; Scherer, R.; Brunner, C.; Leeb, R.; Pfurtscheller, G. Better than random? A closer look on BCI results. Int. J. Bioelectromagn. 2008, 10, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, B.; Abou-Zeid, H.; Kirton, A.; Kinney-Lang, E. Benchmarking motor imagery algorithms for pediatric users of brain-computer interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2024 46th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Orlando, FL, USA, 15–19 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jochumsen, M.; Hougaard, B.I.; Kristensen, M.S.; Knoche, H. Implementing Performance Accommodation Mechanisms in Online BCI for Stroke Rehabilitation: A Study on Perceived Control and Frustration. Sensors 2022, 22, 9051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Groll, V.G.; Leeuwis, N.; Rimbert, S.; Roc, A.; Pillette, L.; Lotte, F.; Alimardani, M. Large scale investigation of the effect of gender on mu rhythm suppression in motor imagery brain-computer interfaces. Brain-Comput. Interfaces 2024, 11, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient | Age | Gender | Diagnosis | Most Affected Side | Able to Wash Hair | Walking Ability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | Male | CP (Diplegia) | Right | Yes, 2 hands | Yes, with cane |

| 2 | 40 | Male | CP (Tetraparesis) | Right | No | No, sits in electrical wheelchair |

| 3 | 34 | Male | CP (Tetraparesis) | Right | No | No, sits in electrical wheelchair |

| 4 | 19 | Male | CP | Right | Yes, 2 hands | Yes, with walker |

| 5 | 22 | Male | CP (Hemiplegia) | Right | Yes, 2 hands | Yes |

| Within-Session | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist (CP) | 75 25 | 76 24 | |

| 27 73 | 27 73 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 64 36 | 75 25 | |

| 32 68 | 25 75 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 85 15 | 85 15 | 87 13 |

| 16 84 | 16 84 | 15 85 | |

| Between-Session | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

| Wrist (CP) | 53 47 | 63 37 | |

| 33 67 | 38 62 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 53 47 | 65 35 | |

| 30 70 | 42 58 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 81 19 | 81 19 | 88 12 |

| 16 84 | 19 81 | 15 85 | |

| Across-Participant | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

| Wrist (CP) | 44 56 | 53 47 | |

| 38 62 | 34 66 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 48 52 | 40 60 | |

| 38 62 | 35 65 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 78 22 | 79 21 | 81 19 |

| 16 84 | 22 78 | 16 84 | |

| Across-Condition | Day 1 | Day 2 | |

| Wrist (CP) | 50 50 | 50 50 | |

| 33 67 | 34 66 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 49 51 | 40 60 | |

| 37 63 | 32 68 |

| Temporal | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist (CP) | 69 31 | 63 37 | |

| 29 71 | 36 64 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 64 36 | 61 39 | |

| 37 63 | 32 68 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 82 18 | 83 17 | 89 11 |

| 21 79 | 19 81 | 15 85 | |

| Spectral | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

| Wrist (CP) | 66 34 | 72 28 | |

| 33 67 | 34 66 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 60 40 | 69 31 | |

| 40 60 | 32 68 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 66 34 | 67 33 | 69 31 |

| 34 66 | 36 64 | 35 65 | |

| Template | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 |

| Wrist (CP) | 68 32 | 64 36 | |

| 32 68 | 39 61 | ||

| Ankle (CP) | 59 41 | 67 33 | |

| 38 62 | 35 65 | ||

| Wrist (Able-Bodied) | 81 19 | 83 17 | 87 13 |

| 20 80 | 19 81 | 15 85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jochumsen, M.; Sulkjær, C.S.; Dalgaard, K.S. Comparison of Classifier Calibration Schemes for Movement Intention Detection in Individuals with Cerebral Palsy for Inducing Plasticity with Brain–Computer Interfaces. Sensors 2025, 25, 7347. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237347

Jochumsen M, Sulkjær CS, Dalgaard KS. Comparison of Classifier Calibration Schemes for Movement Intention Detection in Individuals with Cerebral Palsy for Inducing Plasticity with Brain–Computer Interfaces. Sensors. 2025; 25(23):7347. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237347

Chicago/Turabian StyleJochumsen, Mads, Cecilie Sørenbye Sulkjær, and Kirstine Schultz Dalgaard. 2025. "Comparison of Classifier Calibration Schemes for Movement Intention Detection in Individuals with Cerebral Palsy for Inducing Plasticity with Brain–Computer Interfaces" Sensors 25, no. 23: 7347. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237347

APA StyleJochumsen, M., Sulkjær, C. S., & Dalgaard, K. S. (2025). Comparison of Classifier Calibration Schemes for Movement Intention Detection in Individuals with Cerebral Palsy for Inducing Plasticity with Brain–Computer Interfaces. Sensors, 25(23), 7347. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25237347