Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has reignited interest in traditional medicinal plants as potential therapeutic agents. This study examined the chemical composition, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from six Moroccan medicinal plants, namely, Eucalyptus globulus, Artemisia absinthium, Syzygium aromaticum, Thymus vulgaris, Artemisia alba, and Santolina chamaecyparissus, which are commonly used by the Moroccan population for COVID-19 prevention. The chemical composition of each essential oil was determined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) to identify key compounds. Cytotoxicity was evaluated in the Vero E6 cell line, which is frequently used in SARS-CoV-2 research, using the neutral red assay, with oil concentrations ranging from 25 to 100 µg/mL. Antimicrobial activity was tested against standard reference strains, including Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853), Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 25923), Candida albicans (ATCC 10231), and Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), using the disc diffusion method. GC–MS analysis revealed significant components such as spathulenol (15%) and caryophyllene oxide (7.67%) in Eucalyptus globulus and eugenol (54.96%) in Syzygium aromaticum. Cytotoxicity assays indicated that higher concentrations of essential oils significantly reduced cell viability, with Thymus vulgaris showing the highest IC50 (8.324 µM) and Artemisia absinthium the lowest (18.49 µM). In terms of antimicrobial activity, Eucalyptus globulus had the strongest effect, with a 20 ± 0.00 mm inhibition zone against Bacillus subtilis, whereas both Syzygium aromaticum and Artemisia herba-alba had a 12.25 ± 0.1 mm inhibition zone against the same strain. These findings suggest that these essential oils have significant therapeutic potential, particularly in combating antimicrobial resistance and exerting cytotoxic effects on viral cell lines. Further research is necessary to explore their mechanisms of action and ensure their safety for therapeutic use.

1. Introduction

Since the Middle Ages, aromatherapy has been employed in traditional pharmacopoeia for a wide range of applications, including cancer treatment; anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antiviral activities; and insecticidal, medicinal, and cosmetic uses [1]. The essential oils derived from these plants contain a complex mixture of volatile compounds, such as monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, phenolic derivatives, and aliphatic compounds, which are believed to contribute to their therapeutic effects [2]. The chemical composition of these oils can vary significantly depending on the plant species, geographic origin, and extraction methods [2]. To date, the importance of aromatic oils remains significant, with an increased understanding of their mechanisms of action on various biological and medicinal activities, such as their cytotoxic and antimicrobial effects.

Like many other countries, Morocco has a long history of the use of aromatic medicinal plants for curative and preventive purposes. Its Mediterranean location and diverse climatic conditions enrich its vegetation and plant species. In addition, the herbal market in Morocco has good knowledge of the benefits and medicinal uses of plants, which means that the majority of Moroccans consumed different plants at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, not only because of the lack of other treatments but also because they are less expensive and more available [3]. Moreover, numerous ethnobotanical studies conducted during the pandemic in all of Morrocco’s prefectures provide valuable insights into traditional knowledge and practices related to the use of these plants, serving as a basis for scientific investigation. The aromatic medicinal plants examined in this study, including Thymus vulgaris L., Eucalyptus globulus, and Artemisia absinthium L., are among the most widely distributed and used by the Moroccan population for treating respiratory ailments. For example, Artemisia absinthium and Thymus vulgaris L. are commonly consumed as tea by Moroccans during the winter season. On the other hand, cytotoxic effects were observed in vitro against bacteria and eukaryotic cells, causing membrane damage, depolarization of mitochondrial membranes by decreasing the membrane potential, coagulation of the cytoplasm, and damage to cellular lipids and proteins, as well as exerting prooxidant activity [1]. These cytotoxic properties can disrupt the cellular function of microorganisms, making essential oils effective as antiseptic and antimicrobial agents for personal hygiene and air purification [1]. This attribute makes essential oils promising candidates for further research on multidrug-resistant bacteria. Indeed, aromatic plants have demonstrated notable activity in various studies [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. The rise of multidrug resistance, combined with the adverse effects of current antibiotics on public health and the lack of new effective antibiotics, underscores the urgent need to explore alternative treatments [12].

Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has highlighted the urgent need for effective treatments and preventive measures. Various studies have reported the promising anti-COVID-19 properties of essential oils from plants such as Mentha pulegium, Mentha microphylla, Mentha vilosa, Mentha thymifolia, Illicium verum, Syzygium aromaticum, Citrus limon, and Pelargonium graveolens. These essential oils have demonstrated a selectivity index (SI) of more than four against SARS-CoV-2 [13]. The vaporous nature of essential oils gives them an advantage in targeting the respiratory system, where SARS-CoV-2 primarily infects. Eucalyptol, for example, has been shown to have a direct virucidal effect by interfering with the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins to ACE2 receptors. This compound tends to concentrate in the lungs, particularly in the lower respiratory tract, where it may exert a local virucidal effect [14,15].

The cytotoxicity of essential oils may correlate with their antiviral activity, as previous research has demonstrated a direct relationship between high cytotoxicity and strong anti-SARS-CoV-2 effects. For example, essential oils such as Syzygium aromaticum, Cymbopogon citratus, Citrus limon, Pelargonium graveolens, Origanum vulgare, and Matricaria recutita exhibited high antiviral activity, which was accompanied by high cytotoxicity. In contrast, Zingiber officinalis, Melaleuca alternifolia, and Rosmarinus officinalis showed lower cytotoxicity and, correspondingly, lower anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity [16].

This study offers new insights into the chemical composition, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Moroccan medicinal plants, including Artemisia absinthium L., Syzygium aromaticum, Artemisia herba-alba, Eucalyptus globulus, Thymus vulgaris L., and Santolina chamaecyparissus. Although these plants have been investigated in prior research,

These plants species have received considerable attention, and numerous biological activities have been reported for the corresponding essential oils. A noteworthy difference in the chemical composition of oils collected in different geographical areas emerges from the analysis of these studies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Regarding E. globulus, the monoterpene 1,8-cineole (30%), is usually identified as the major components of its essential oil [24]. A. absithium is probably the species presenting more variability in the chemical composition of its essential oils, although β-thujone and trans-sabinyl acetate are recognized as major components of its essential oil [25]. Eugenol is the major compound of clove (S. aromaticum) essential oil, accounting for at least 50% [26]. composition. The major component of thyme essential oil is thymol, although the presence of p-cymene is also significant in this essential oil [27]. A. alba is characterized by a high content of camphor [28]. Finally, artemisia ketone is generally the major constituent identified in the essential oil of S. chamaecyparissus [29].

In addition to the remarkable number of biological applications attributed to these essential oils, three of them, namely E. globulus, S. aromaticum and T. vulgaris, have been evaluated for their potential anti-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) effects [30].

The observed strong geographic influence on the chemical composition of the essential oils, as well as the evidence of their potential activity against COVID-19, led us to conduct this study. Thus, by identifying their chemical compounds and establishing noncytotoxic concentrations, we provide valuable data that can guide further exploration of these essential oils for potential antiviral or anti-COVID-19 applications. Notably, this research included Artemisia absinthium L., Santolina chamaecyparissus, and Artemisia herba alba, which were tested on the Vero E6 cell line for the first time, offering essential insights into the safe and effective use of these oils in therapeutic contexts.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils

The essential oil yields obtained from the studied plants ranged from 0.3% to 7.5% (v/w), with S. aromaticum showing the highest yield at approximately 7.5%, followed by E. globulus (3.0%), T. vulgaris (2.0%), A. absinthium (1.2%), S. chamaecyparissus (0.8%), and A. herba-alba (0.5%). Variations in yield can be attributed to differences in plant material, harvesting conditions, and extraction techniques.

The complexity of the essential oils was identified and quantified by chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. Our findings revealed differences from those of previous analyses, highlighting variations in the chemical profiles and potential implications for their use.

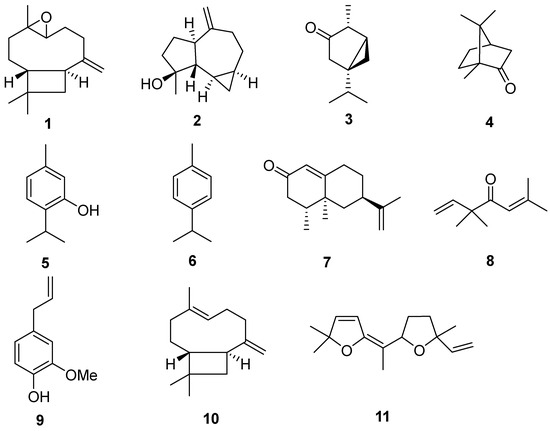

In the absinthe oil analyzed, 51 compounds were identified, representing 99.81% of the total compounds. The results revealed that the oil is rich in α-thujone (3) (29.02%) and camphor (4) (24.34%), with notable amounts of chamazulene (6.92%) and (−)-4-terpineol (3.68%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chemical composition of A. absinthium L. (boldface indicates a major compound).

As previously stated, in most of the previous studies, the presence of the β-thujone isomer has been usually reported to be greater than that of its isomer α-thujone (3) in the oil [31]. Contrary to expectations, our study revealed that α-thujone (3) was present at a remarkably high level of 29%, whereas β-thujone was detected at only 1.67%. Surprisingly, another Moroccan study revealed that A. absinthium essential oil was rich in 3,3,5-trimethylcyclohexene (27.93%), which was absent in our study, and camphor (4) (22.50%, a level similar to what we found), but no α-thujone or β-thujone were detected in the sample [22]. At least 17 major compounds, including myrcene, sabinene, sabinyl acetate, epoxyocimene, chrysanthenol, chrysanthenyl acetate, linalool, chamazulene and β-pinene, have been identified in plant oil across Europe [31,32,33,34,35,36]. However, our sample was devoid of cis-epoxycimene, chrysanthenol, chrysanthenyl acetate and β pinene. Another interesting compound identified in our sample was arborescin, a sesquiterpene compound scarcely found in wormwood oil from other geographical regions. It is worth noting that sage and lavender essential oils, whose main components include, as in our oil, camphor, α-thujone, and terpinen-4-ol, showed promising antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral activity, making these oils and compounds good candidates for the development of new antiviral agents [37].

The chemical composition of E. globulus labill comprised 67 compounds, representing 99.26% of the total oil (Table 2). Our oil analysis detected spathulenol (2) (structure shown in Figure 1) as an abundant component at 15%, whereas the predominant compounds, 1,8-cineole or eucalyptol, the best-known molecules in eucalyptus oil, accounted for only 4.52%. These results contradict those of another Moroccan study conducted in the province of Ouejda, where the results revealed 79.85% 1,8-cineole, whereas no trace of spathulenol was detected (2) [38]. On the other hand, other molecules were determined in our study to be major compounds but were absent in other works [39,40,41], such as caryophyllene oxide (1) (7.67%), trans-caryophyllene (10) (7.33%) and farnesol (7.52%). 1,8-Cineole, major component of this essential oil, is known for its antiviral potential against different human pathogen DNA and RNA viruses including rhinoviruses. Additionally, a recent permit proposes that this substance, the major propones que esta sustancia, componente mayor component of Coldmix®—a commercially available Eucalyptus aetheroleum and Abies aetheroleum blend for medicinal applications (Anadolu Hayat Essence & Chemical Ind. Co., Eskişehir, Turkey), may contribute or is even responsible for the anticovid activity attributed to this mixture [42].

Table 2.

Chemical composition of E. globulus (boldface indicates a major compound).

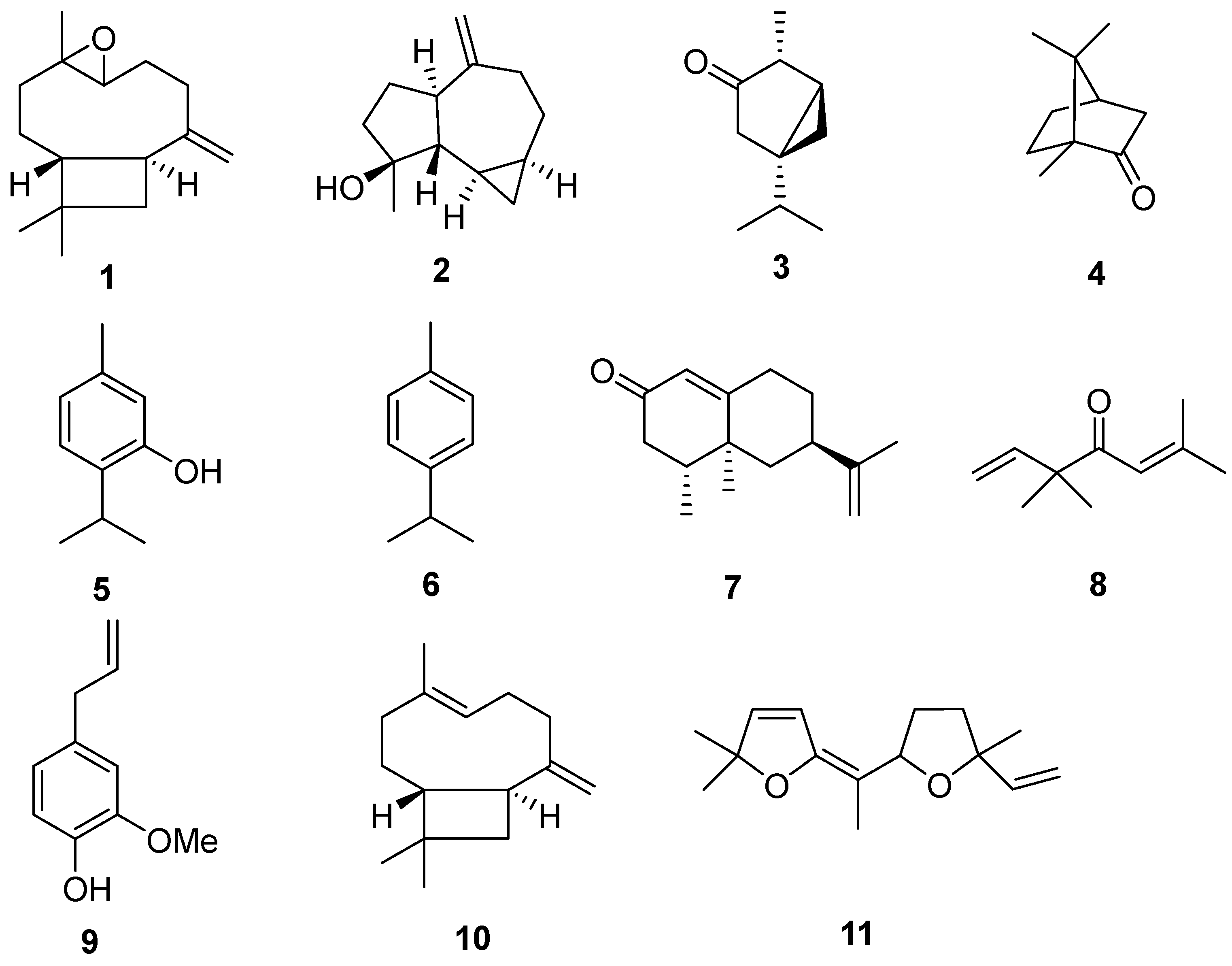

Figure 1.

Major compounds identified in the essential oils of six plants: caryophyllene oxide (1), spathulenol (2), α-thujone (3), camphor (4), thymol (5), p-cymene (6), longiverbenone (7), artemisia ketone (8), eugenol (9), trans-caryophyllene (10) and davana ether (11).

The chromatographic profile of S. aromaticum oil (Figure 2) revealed 16 compounds, representing 99.72% of the total oil content (Table 3). The main compound was eugenol (9) (54.96%), followed by trans-caryophyllene (10) (29.18%). These molecules are the best-known clove essential oils in various studies [13,14,15,16]. In addition to these two molecules, two components were interestingly found in our sample, α-cubebene (1.34%) and α-copaene (1.9%), which are absent from most of the publications cited above. Significantly, in silico studies indicate that eugenol exhibits a strong affinity for the structural components of SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, the oral administration of eugenol proved to reduced COVID-19 symptoms in mice treated with the SARS-CoV-2 spike S1 protein [43].

Figure 2.

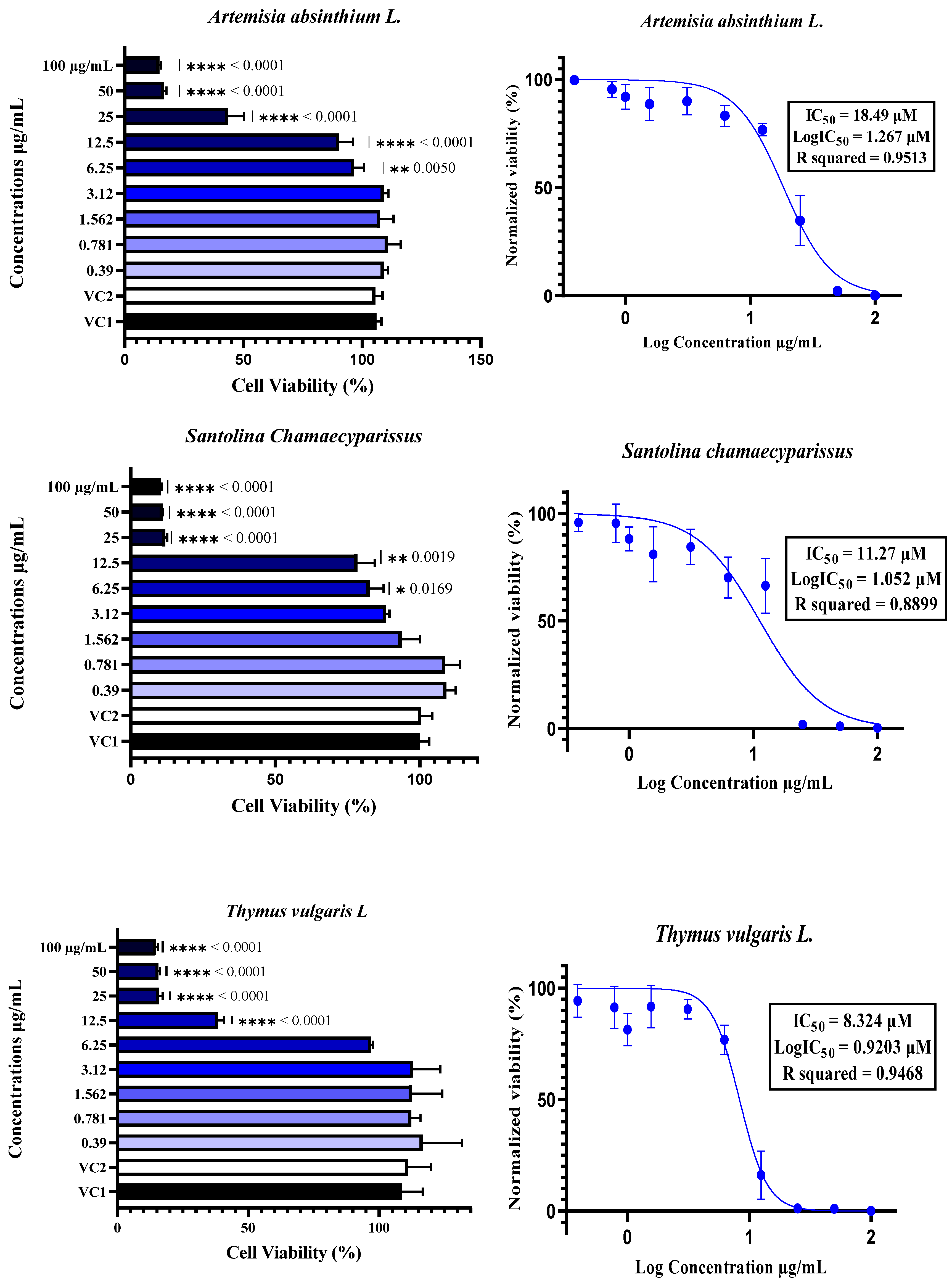

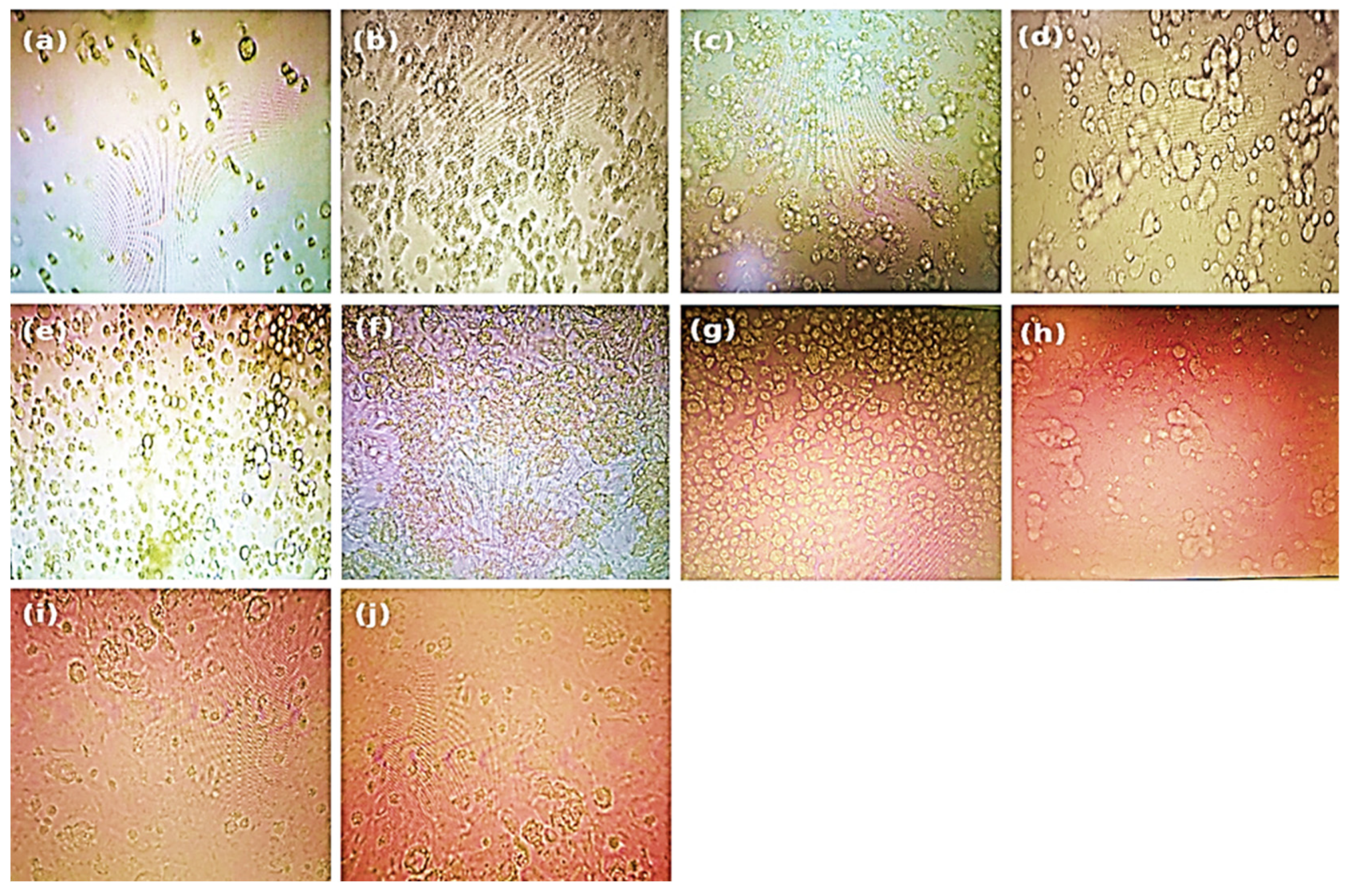

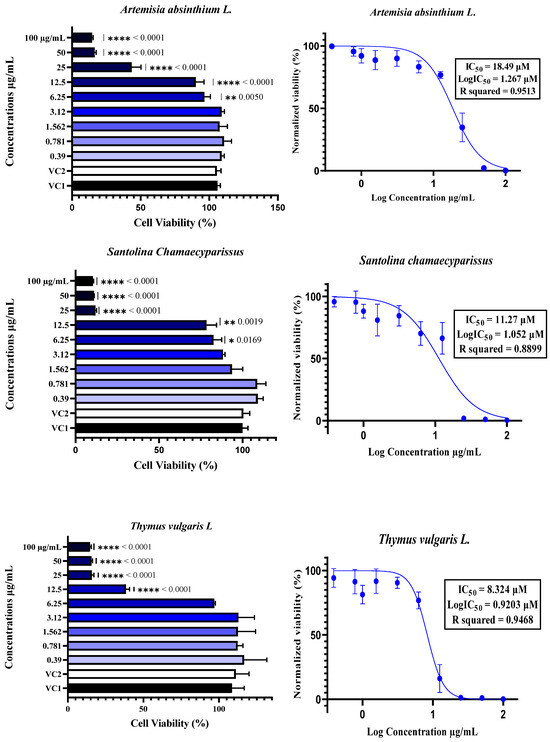

The cytotoxicity of plant essential oils (EOs) to Vero E6 cells was assessed by treating the cells with EOs at concentrations ranging from 0.39 µM to 100 µM. Cytotoxicity was determined using the neutral red uptake assay, with the results expressed as a percentage of cell viability compared with Vehicle Control 1 (VC1: untreated cells) and Vehicle Control 2 (VC2: DMSO/TWEEN 20-treated cells). The data are expressed as the means ± SDs, n = 4. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated by normalizing the data and applying nonlinear regression analysis. Comparisons between different concentrations and controls were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. In the figures, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, *** indicates p < 0.001, and **** indicates p < 0.0001.

Table 3.

Chemical composition of S. aromaticum (boldface indicates a major compound).

The characterization of T. vulgaris essential oil via GC–MS analysis revealed a total of 40 compounds, collectively accounting for 100% of the composition of the oil. Among these, 14 compounds were found to have concentrations greater than 1%, with individual percentages ranging from 1.28% to 33.33% (Table 4). The major component identified was thymol (5), an active monoterpene, which comprised 33.33% of the essential oil. This was followed by significant quantities of its terpenic hydrocarbon precursors, p-cymene (6) (25.87%) and γ-terpinene (7.21%). Additionally, a noteworthy concentration of carvacrol (5.23%), which is another phenolic monoterpene related to thymol (5), was observed. Furthermore, camphor was demonstrated to be a chemical type in thyme essential oil from eastern Morocco at a concentration of 39.39%, but was not detected in our study [44]. With regard to the antiviral activity of thymol, in vitro studies revealed its antiviral potential against SARS-CoV-2, probably due to its phenol ring structure [45].

Table 4.

Chemical composition of T. vulgaris (boldface indicates a major compound).

For A. herba-alba, 50 compounds were detected in the GC/MS analysis, representing 96.73% of the total oil (Table 5). Among these compounds, davana ether (11) was found to be the main compound, with a concentration of 14.48%. Notably, we did not detect the presence of camphor in our analysis. Camphor is a compound whose content is particularly high in A. alba [44,46,47]. In another Moroccan study, davanone was identified as the main chemotypic compound of the essential oil, followed by davana ether (11) [48]. This suggests the presence of specific and advanced biosynthetic pathways. Other davanone derivatives, such as nordavanone (2.19%) and davana furan (1.31%), have also been detected; these compounds are valuable ingredients in perfumery and aromatherapy and are generally isolated from the essential oil of Artemisia pallens [48]. Three other oxygenated monoterpenes were recognized as fingerprints of this essential oil in addition to those mentioned above: chrysanthenone, cis chrysanthenyl acetate and 1,8-cineole, as published in [49,50], where they were classified as major compounds compared with the low traces found in our sample (cis chrysanthenyl acetate (0.97%) and 1,8-cineole (0.67%)) (see the full Table S5). This may be explained by the difference in harvesting time, since camphor plays a role in the chrysanthenone biosynthesis pathway.

Table 5.

Chemical composition of A. herba-alba (boldface indicates a major compound).

S. chamaecyparissus essential oil was also studied, yielding 70 compounds, accounting for 99.98% of the oil (Table 6). The predominant compound observed was longiverbenone (7) (nootkatone), with a proportion of 18.15%, followed by artemisia ketone (8) (15.58%). This contrasts with previous reports [23,51], in which artemisia ketone (8) was detected as the main compound, with a proportion close to 15.65%, whereas nookatone (7) accounted for only 6.97%. According to numerous revised articles, various chemotypes from different regions have been noted to be completely devoid of nootkatone (7) [52,53,54,55,56,57]. Other compounds known as fingerprints of this plant were detected in different proportions, such as α-curcumene (4.82%), spathulenol (2) (4.41%) and epizanone (3.19%). It is worth noting that nootkatone, the major component of this oil proved to moderately inhibit SARS-CoV-2 [58]. A complete list of all the identified compounds and their characteristics can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 6.

Chemical composition of S. chamaecyparissus (boldface indicates a major compound).

2.2. Cytotoxicity of Essential Oils

The cytotoxicity of essential oils was evaluated in Vero E6 cells, a widely accepted model for SARS-CoV-2 research, using a neutral red uptake assay after 48 h of incubation at concentrations ranging from 0.39 to 100 µg/mL (Figure 3). The results revealed a clear dose-dependent cytotoxic effect, with essential oils exhibiting significantly reduced cell viability at concentrations ≥12.5 µg/mL, as confirmed by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). The IC50 values varied notably among the six essential oils, ranging from 8.32 µM for T. vulgaris to 18.49 µM for A. absinthium. This variation appears to be strongly linked to the chemical composition of the oils. T. vulgaris, which had the greatest degree of cytotoxicity, contains thymol (5) and carvacrol, both of which are phenolic compounds with well-documented membrane-disruptive and apoptosis-inducing effects on cancer and epithelial cell lines [59,60,61,62]. However, the relatively lower concentration of carvacrol (5.23%) in our sample than the 25.5% reported in [16] could explain the moderate toxicity compared with the previously reported CC50 value of 2 µg/mL. E. globulus oil, which had similar cytotoxic potency (IC50 = 8.36 µM), had a different chemical profile than typically reported: instead of a high content of 1,8-cineole (86.6%) [16], our sample was rich in spathulenol (2) (15%), an alcohol with known moderate cytotoxic properties [16,63,64]. S. aromaticum presented an IC50 of 12.17 µM, which may be attributed to its eugenol (9) content (54.96%), a phenolic compound associated with strong cytotoxic effects [59,65]. Similarly, S. chamaecyparissus displayed an IC50 of 11.27 µM, which could be explained by the unusually high content of nootkatone (7) (18.15%) in our sample. Nootkatone (7), a sesquiterpenoid ketone rarely identified in Santolina oils, has shown potent cytotoxic activity in HL-60 and retinoblastoma cell lines, which is attributed to ROS generation, NF-κB suppression, autophagy induction, and cell cycle arrest [66,67,68,69]. In the case of A. herba-alba (IC50 = 13.69 µM) and A. absinthium (IC50 = 18.49 µM), the variability in toxicity relative to the literature data [70,71,72] can likely be attributed to differences in the chemotype and constituent ratios. The greater toxicity of A. absinthium in our study may be explained by its significant thujone (3) content (29.02%), a monoterpene shown to be cytotoxic at low micromolar concentrations across multiple cancer cell lines [73,74]. These findings highlight that its cytotoxicity is not solely dependent on major constituents but also on the complex interactions among minor compounds, which may modulate their absorption, solubility, and bioavailability [63,75]. Additionally, functional group analysis from previous chemometric studies [16] supports our observations, showing that phenols, alcohols, aldehydes, and esters tend to increase cytotoxic and antiviral activity, whereas ethers and hydrocarbons may reduce it. Therefore, the stronger cytotoxic effects observed in T. vulgaris, S. aromaticum, and E. globulus may be attributed directly to the relative abundance of active functional groups. Overall, the observed cytotoxic profiles are strongly correlated with the phytochemical composition, the concentration and type of functional groups present, and the potential synergistic interactions between constituents, confirming the relevance of the essential oil chemotype in determining bioactivity.

Figure 3.

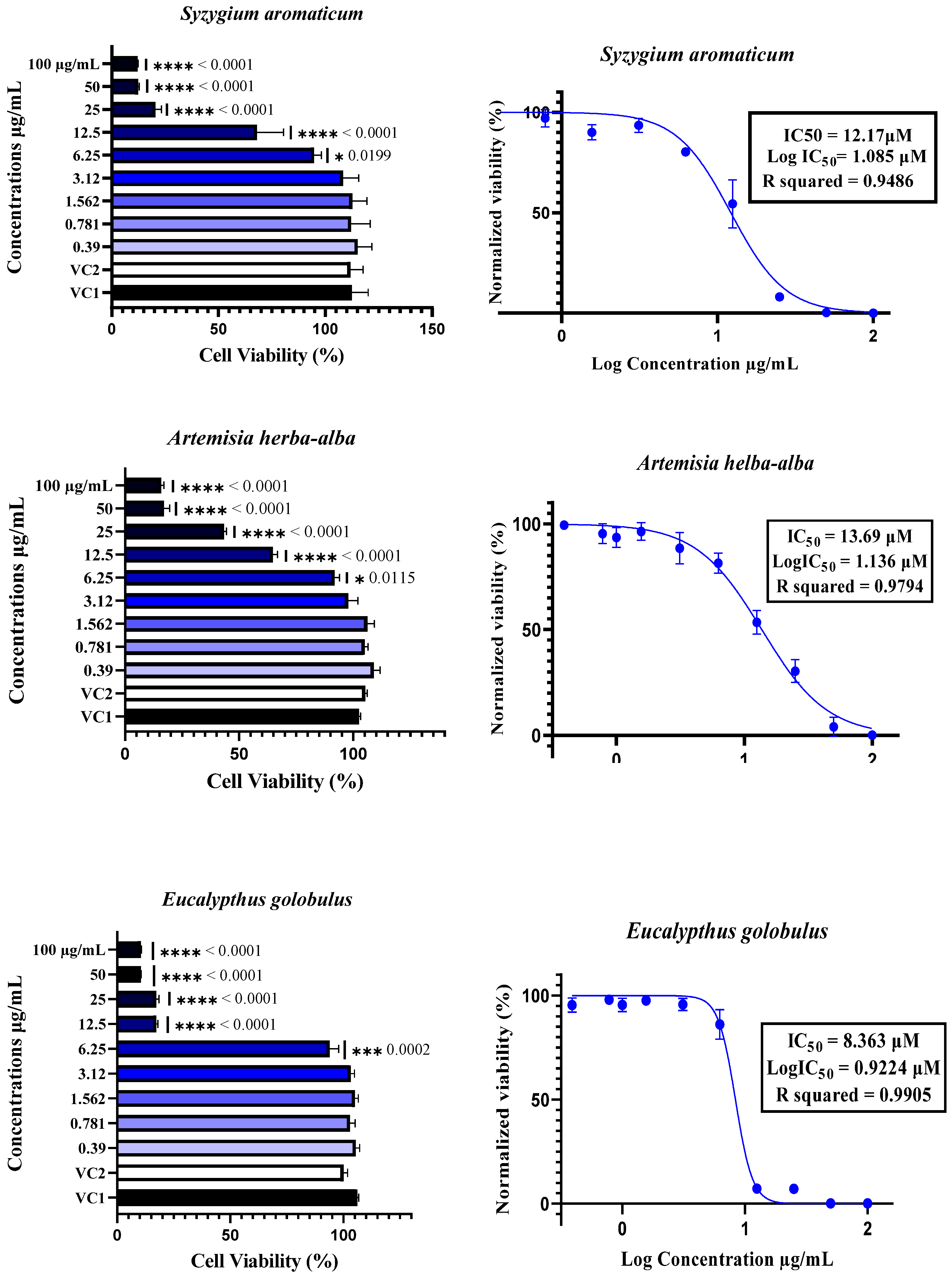

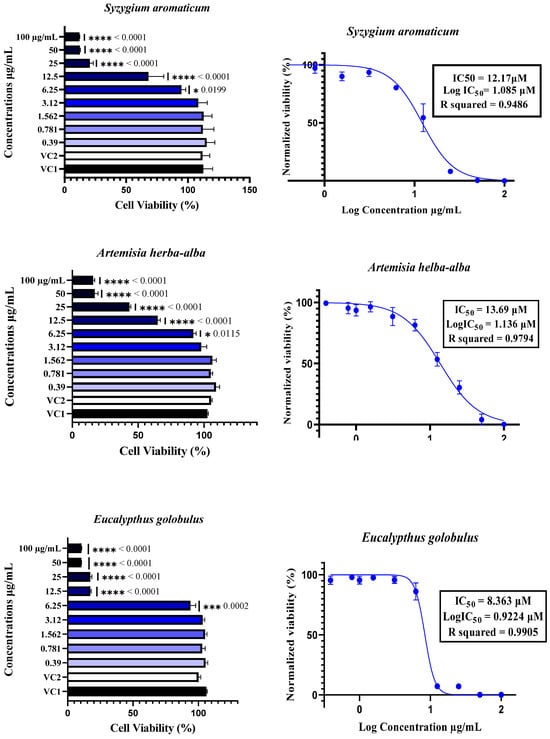

Microscopic evaluation of the monolayers revealed dose-dependent cytotoxic effects, with particular attention to cell rounding and other prominent morphological alterations compared with those of the control cells after 48 ± 2 h of incubation with the treatment concentrations, prior to performing the neutral red assay. The treatments used were as follows: (a) 100 µg/mL, (b) 50 µg/mL, (c) 25 µg/mL, (d) 12.5 µg/mL, (e) 6.25 µg/mL, (f) 3.12 µg/mL, (g) 1.562 µg/mL, (h) 0.781 µg/mL, (i) 0.39 µg/mL, and (j) untreated control.

2.3. Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial efficacy of the essential oils, as presented in Table 7, was evaluated against standard antibiotics and antifungal agents (Table 8) using inhibition zone diameters as the primary metric. E. globulus showed moderate activity against E. coli (11 mm; +), although it was less effective than gentamicin and nalidixic acid (18 mm; ++), which is consistent with prior reports indicating limited gram-negative activity for Eucalyptus species, with minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) ranging from 1000–2000 µg/mL [17]. This moderate efficacy may reflect the specific phytochemical profile of the tested oil, which included compounds such as farnesol, which was shown to exhibit antimicrobial activity against E. coli and Aspergillus niger, with inhibition zones of 12 mm and 11 mm, respectively, at 50 μg/mL [76]. P. aeruginosa was resistant to all the essential oils tested and showed only minimal sensitivity to gentamicin (10 mm; +), reflecting its well-known resistance mechanisms, including a restrictive outer membrane [77] and active efflux pumps [78] that limit the intracellular accumulation of lipophilic agents such as terpenes and phenolics.

Table 7.

Comparative evaluation of essential oils for antimicrobial potential against reference microbial strain.

Table 8.

Comparative antimicrobial efficacy of reference antibiotics and antifungal agents against reference microbial strain.

In contrast, gram-positive bacteria such as B. subtilis were more responsive: E. globulus exhibited extreme sensitivity (+++, 20 mm), comparable to nalidixic acid. This heightened activity may be linked to better membrane permeability and the presence of bioactive components such as 1,8-cineole, spathulenol, β-caryophyllene, and caryophyllene oxide, all of which have demonstrated antimicrobial activity depending on their concentration and synergistic interactions [79,80]. S. aromaticum and A. herba-alba also showed moderate sensitivity (++) to B. subtilis, likely due to the high eugenol content in clove oil, which results in strong antimicrobial effects across a wide spectrum of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria as well as fungi [81]. A. herba-alba contains potent phenolic and ketonic components that have demonstrated high antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and Shigella sp. at low concentrations (0.07–10 mg/mL) [82].

Similarly, T. vulgaris exhibited moderate inhibitory effects (15 mm; +) on S. aureus, which is consistent with the high levels of thymol and carvacrol. These phenolic compounds target bacterial membranes, disrupt metabolic processes, and are also effective against multidrug-resistant strains such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, with MICs between 32–128 µg/mL [83]. In contrast, S. epidermidis exhibited limited sensitivity to essential oils, whereas gentamicin showed moderate efficacy (12 mm; +). This reduced susceptibility may be due to biofilm formation and gene transfer mechanisms that increase resistance [7].

For C. albicans, S. chamaecyparissus showed slight sensitivity (+, 11.75 ± 0.1 mm), whereas itraconazole exhibited extreme sensitivity (+++, 19 mm). This reduced antifungal effect may stem from differences in essential oil composition, including lower levels of potent antifungals such as nootkatone or a greater proportion of less active monoterpenes [69]. These findings contrast with those of Abd El-Baky et al. [84], who reported strong antifungal activity in oils rich in borneol, linalool, and eugenol. Additionally, Candida glabrata ATCC 28226 and Malassezia furfur ATCC 4342 were tested but showed no sensitivity to any of the essential oils evaluated, indicating that further investigations are needed to better understand these fungal responses. While the antifungal data are limited, the results against C. albicans suggest potential for S. chamaecyparissus, which warrants further exploration.

Importantly, the antimicrobial performance of these essential oils closely correlated with their dominant phytochemical profiles. The presence of phenolic compounds (eugenol, thymol, carvacrol), ketones (thujone, artemisia ketone, nootkatone), and sesquiterpenes (spathulenol, caryophyllene oxide) was consistently associated with stronger antimicrobial effects. These compounds act through various mechanisms, including disruption of cell membranes, inhibition of metabolic enzymes, and interference with quorum sensing. This structure–activity relationship underscores the need for detailed chemical profiling when evaluating essential oil bioactivity and supports their potential role, although currently limited, as adjuncts in antimicrobial treatment strategies.

The obtained results show poor agreement with previously reported data. The differences observed between our findings and those in the literature can be attributed to a combination of ecological, genetic, and methodological factors known to influence essential oil biosynthesis. The qualitative and quantitative composition of essential oils is strongly affected by environmental parameters such as altitude, temperature, humidity, photoperiod, and soil nutrient availability, all of which modulate the enzymatic pathways involved in terpene formation [1,85].

In the case of A. absinthium, the predominance of α-thujone and camphor observed in Moroccan samples may be linked to enhanced activity of the sabinene-derived thujone biosynthetic pathway, which has been characterized in related Artemisia species [86]. Environmental stressors typical of semi-arid regions, such as elevated temperature and solar radiation, are known to influence monoterpene metabolism and could thereby favor α-thujone accumulation [87]. The comparatively low β-thujone content may reflect population-specific chemotypic variation rather than differences in isomerization efficiency [88].

Similarly, in Eucalyptus globulus, the relatively low proportion of 1,8-cineole and the higher abundance of spathulenol may reflect species- and environment-specific variability in volatile composition. In Eucalyptus, temperature and other abiotic factors, which are typical of Moroccan coastal ecosystems, are known to influence monoterpene emissions and alter the relative abundance of compounds, while variation in essential oil composition across taxa and populations is largely determined by species identity, developmental stage, and growth conditions [89,90]. Additionally, Differences may also arise from post-harvest and methodological factors. The moisture level and storage duration of plant material prior to hydrodistillation can alter volatile compound stability, while the distillation time, temperature, and apparatus configuration can influence the relative recovery of low-boiling versus high-boiling constituents [91]. In Thymus vulgaris, the observed predominance of thymol over its precursors p-cymene and γ-terpinene likely reflects the harvest stage, since oxidative conversion of γ-terpinene to thymol increases near flowering [92]. Chemotypic variation is further enhanced by genetic polymorphism and potential hybridization within plant populations, giving rise to locally adapted chemical phenotypes [93].

Overall, the enrichment of oxygenated terpenes (e.g., spathulenol, camphor, thymol) in our samples may enhance antimicrobial potency and cytotoxic selectivity, suggesting that Moroccan chemotypes could represent valuable sources of bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical and therapeutic applications.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Collection

Aromatic medicinal herbs (Artemisia absinthium L., Syzygium aromaticum, Artemisia herba-alba, and Eucalyptus globulus) were procured from a local herb store in Rabat, Morocco, in March 2022. The medicinal plants were identified morphologically with the assistance of Professor Khamar Hamid from the Botany Department at the Scientific Institute of Mohammed V University in Rabat, Morocco. Additional plant species, including Santolina chamaecyparissus and Thymus vulgaris L., were provided in May 2022 by the National Agency for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (ANPMA) in Taounate, Morocco. This study utilized the aerial parts of Artemisia absinthium L., Santolina chamaecyparissus, Artemisia herba-alba, Eucalyptus globulus, and Thymus vulgaris L., as well as the seeds of Syzygium aromaticum, to accurately reflect their traditional usage by the Moroccan population.

3.2. Extraction of Essential Oils

The fresh aerial parts were dried at room temperature in the dark in an open drying room for ten days. After drying, they were pulverized into small pieces using a Willy mill and labeled. The essential oils from the six species were prepared using a conventional hydrodistillation method in a Clevenger-type apparatus, following a slightly modified version of the method described by [94]. Specifically, 200 g of each sample was accurately weighed and combined with 1 L of distilled water in a 2 L flask connected to a Clevenger-type apparatus with a Dean–Stark distillation tank. The mixture was heated to 100 °C for 3 h, as per the standard procedure of the European Pharmacopoeia. The concentrated essential oil was then manually separated from the aromatic water and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove any residual moisture, ensuring that the essential oil remained dry. The final extracts were stored in amber-colored bottles at −20 °C for subsequent cytotoxicity testing.

3.3. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectroscopy Analysis

The essential oils were analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) by a Shimadzu GC-2010 gas chromatograph coupled to a Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 Ultra mass detector (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) operating with electron ionization at 70 eV. Sample injections (1 μL) were performed using an AOC-20i autosampler, and a 30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. capillary column with a 0.25-μm film thickness Teknokroma (Barcelona, Spain) TRB-5 (95% dimethyl-diphenylpolysiloxane, 5%) was used. The operating conditions were as follows: split ratio of 20:1, injector temperature of 300 °C, transfer line temperature of 250 °C, and initial column temperature of 70 °C. The temperature was then increased to 290 °C at a rate of 6 °C/min. Full-scan mode (m/z 35–450) was used for detection. The identities of the compounds were determined by comparing their electron ionization mass spectra and retention data with those in the Wiley 229 and NIST 17 mass spectral databases. For quantification, the relative area percentages of all peaks obtained in the chromatograms were used. All extracts (4 μg/μL) were dissolved in 100% dichloromethane for injection.

3.4. Cytotoxicity Assay of Essential Oils

3.4.1. Vero-E6 Cells

The potential effects of essential oils on cell morphology and viability were investigated in vitro using the Vero-E6 cell line, which has been shown to be highly sensitive to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The cell line used in this study corresponds to green monkey kidney fibroblasts (Cercopithecus aethiops) maintained in continuous culture (ATCC-CRL-1586, Vero cells, passage 3). The cells were originally obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and provided for this study by the Centre National de Référence (CNR), Lyon, France.

3.4.2. Culture Medium and Preparation of Plates

The culture medium used for maintaining and growing the cells was Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Vacaville, CA, USA), which was modified with Earle’s salts (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and nonessential amino acids. The medium was buffered with 7.5% sodium bicarbonate to a pH of 6.90 ± 0.1 under CO2. Sterile fetal bovine serum (FBS) (10%) (Gibco, USA) was added to the DMEM. Vero-E6 cells were cultured as monolayers in tissue culture flasks (75–25 cm2) under standard conditions of 37 °C ± 1 °C, 90% ± 5% humidity, and 5.0% ± 1% CO2/air. The cell morphology was monitored daily using a phase-contrast microscope to ensure optimal growth conditions. After reaching 80% confluence, the cells were detached from the flasks with 0.5% trypsin diluted in PBS (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For the experiment, a 3.105 cells/mL cell suspension was prepared and added to 96-well microtiter plates (200 µL per well). The plates were then incubated for 24 ± 2 h under the same conditions to allow for cell recovery and adhesion, forming a monolayer of less than 50% confluence.

3.4.3. Preparation of Essential Oils

To prepare the essential oils, 10 µL of each oil (equivalent to 1 mg) was solubilized in a mixture of two emulsifiers, DMSO and TWEEN 20, at a concentration of 2% (v/v). This mixture was optimized to ensure complete solubilization and improve the diffusion of volatile molecules while minimizing toxicity to the cells. The resulting homogeneous stock solution for each essential oil was then prepared for the assay. Each stock solution was further diluted in culture medium (without FBS) using a titration plate. The initial dilution was 1/10, followed by a series of double dilutions over a range of concentrations from 100 µg/mL to 0.39 µg/mL.

3.4.4. Cytotoxicity Evaluation via the Neutral Red Colorimetric Assay (NR)

The cytotoxicity of the selected essential oils was evaluated at the National Hygiene Institute in Rabat, Morocco, using the neutral red uptake (NRU) assay, which is based on the method described in [95] with some optimizations. The NRU assay uses neutral red dye, a weak cationic dye that readily penetrates cell membranes by passive nonionic diffusion. The dye accumulates in lysosomes, where it binds to anionic and phosphate groups in the lysosomal matrix via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions.

The essential oils were tested at various concentrations, ranging from 100 to 0.39 µg/mL, in quadruplicate for each. Two control columns were included: one containing the respective solvent and the other containing untreated cells. Immediately after the oils were added, adhesives were applied to the plates to prevent contamination by vapors from high doses. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After the incubation period, the cells were rinsed with prewarmed D-PBS to remove any residual oil. The cells were then incubated for 3 h in neutral red medium prepared in DMEM at a concentration of 40 µg/mL to allow for the formation of NR crystals, indicating cell viability. Following the 3-h incubation, the NR medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed with D-PBS before adding a NR Desorb solution consisting of 50% ethanol, 96%, 49% deionized water, and 1% glacial acetic acid to extract the NR dye from the cells. The plates were shaken for 10 min to ensure thorough extraction, and absorbance measurements were then taken at 540 nm ± 10 nm using a microplate reader (Multiskan EX, Thermo Scientific).

Cell viability was calculated using the following formula:

where OD refers to optical density, control cells refer to solvent-treated cells, and the OD of essential oils refers to treated cells.

% Cell viability = (OD of essential oils/OD of control cells) ×100

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity

3.5.1. Microbial Strains

The eight microbial strains used in this study were selected as standard reference strains commonly employed for evaluating antimicrobial and antifungal activity. These include two gram-negative bacterial strains: Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853; three gram-positive strains: Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923; and three fungal strains: Candida albicans ATCC 10231, Candida glabrata ATCC 28226, and Malassezia furfur ATCC 4342.

3.5.2. Preparation of the Inoculums

Before antimicrobial tests were conducted, all microbial strains were subcultured under appropriate conditions to ensure viability and standardized growth. Bacterial strains (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and S. aureus) were incubated overnight at 37 °C for 24 h on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA). Fungal strains (C. albicans, C. glabrata, and M. furfur) were cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. Well-isolated colonies were collected using a sterile platinum loop and suspended in sterile saline solution. The optical density of the bacterial suspensions was adjusted to a range of 0.4–0.6 at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer, corresponding to a final concentration of 106–107 CFU/mL [96].

3.5.3. Disk Diffusion Method on Agar

To evaluate the sensitivity of the microbial strains to the different essential oils, a disk diffusion method was employed [96]. Briefly, 10 µL of diluted essential oil samples (20 mg/mL, dissolved in 10% DMSO/0.5% Tween 20) were applied to sterile filter paper discs with a diameter of 6 mm. The discs were then placed on Mueller–Hinton agar previously inoculated with the test microorganisms using a sterile loop. For the fungal strains, potato dextrose agar was used. A disk with an equivalent volume of 10% DMSO/0.5% Tween 20 served as the negative control. The positive controls included commercially available antibiotic discs (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), such as gentamicin (10 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), spectinomycin (100 μg), penicillin (6 μg), fluconazole (30 μg), and itraconazole (30 μg). The Petri dishes were incubated at 4 °C for 2 h to facilitate compound diffusion. The diameters of the inhibition zones were subsequently measured in millimeters after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C for bacteria and 48 h at 28 °C for yeast.

The results are expressed as the diameter of the inhibition zone and are categorized according to the sensitivity of the strains to the extracts as follows [97]:

- Not Sensitive (−) or Resistant: Diameter < 8 mm

- Sensitive (+): Diameter between 9 and 14 mm

- Very Sensitive (++): Diameter between 15 and 19 mm

- Extremely Sensitive (+++): Diameter > 20 mm

3.6. Data Analysis

Relative cell viability was expressed as a percentage of the vehicle control (VC). The mean neutral red uptake (NRU) values from four replicates per concentration were calculated, with blank values subtracted. The IC50 value was determined by fitting a nonlinear regression curve to the normalized data using GraphPad Prism software version 9.1.0, with the results reported as the means ± SDs Statistical differences between the experimental and control values were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, with the significance level set at p < 0.05.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study evaluated the cytotoxic effects of various essential oils extracted from aromatic medicinal plants commonly used in Morocco for COVID-19 prevention and treatment via Vero E6 cells. T. vulgaris L., E. globulus, and S. chamaecyparissus presented the most potent cytotoxic activities. The variations in cytotoxicity compared with those reported in previous studies were attributed to differences in chemical composition, cell lines, and assay methodologies. Key compounds such as thymol, carvacrol, eugenol, and thujone significantly contributed to the observed effects.

The assessment of antimicrobial activity against a range of standard bacterial and fungal strains revealed variable effectiveness. Differences in strain biology and essential oil chemistry were highlighted, demonstrating the limited potential of these oils as alternatives to traditional treatments for resistant strains. Further investigation is necessary to understand the mechanisms of action of essential oils and their active compounds and to optimize their use in antimicrobial therapies.

These findings support the need for continued research to explore the therapeutic potential of these essential oils in treating COVID-19 and other viral infections. Future studies should include comprehensive in vitro and in vivo analyses to better understand the antiviral mechanisms and validate the efficacy of these oils against SARS-CoV-2. Our laboratory is currently investigating the antiviral properties of these essential oils, which may lead to novel, plant-based therapeutic strategies for combating viral infections.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules30214179/s1, Figure S1: Gas chromatography chromatograms of the essential oils extracted from the following plants: (1) A. absinthium L.; (2) E. globulus; (3) T. vulgaris; (4) S. aromaticum; (5) A. herba-alba; and (6) S. chamaecyparisses; Table: S1: Chemical composition of Artemisia absinthium; Table: S2: Chemical composition of Eucalypthus globulus; Table: S3: Chemical composition of thymus vulgaris; Table S4: Chemical composition of Syzgium aromatic; Table: S5: Chemical composition of artemisia helba-alba; Table: S6: Chemical composition of Santolina chamaecyparisses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B., J.F.Q.d.M. and H.Z.; methodology, H.Z., A.G.-C. and J.F.Q.d.M.; software, A.G.-C. and H.Z.; validation, H.Z., S.L., J.F.Q.d.M. and B.B.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, H.Z.; resources, A.G.-C., S.L. and J.F.Q.d.M. and editing, S.L. and J.F.Q.d.M.; visualization, B.B. and J.F.Q.d.M.; supervision, J.F.Q.d.M. and B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Grants PID2024-156361OB-C22 (State Research Agency, 10.13039/501100011033) and Unidad Asociada UGR-CSIC BIOPLAG.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article/Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Hicham Omzil for hosting at the laboratory at the National Institute of Health. We would like to acknowledge Latifa Tajoune for her technical assistance and Abdelghafour Talibi for his support with the statistical analysis and review. Additional thanks to the National Agency for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants (ANPMA) in Taounate for supplying the plants and to Hamid Khamar for plant identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EOs | Essential oils |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| IC50 | Inhibitory concentration 50% |

References

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Németh, Z.É. Sources of variability of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) essential oil. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2016, 3, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Douira, A.; Zidane, L. COVID-19, prevention and treatment with herbal medicine in the herbal markets of Salé Prefecture, North-Western Morocco. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 42, 101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swamy, M.K.; Akhtar, M.S.; Sinniah, U.R. Antimicrobial Properties of Plant Essential Oils against Human Pathogens and Their Mode of Action: An Updated Review. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2016, 2016, 3012–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Yiap, B.C.; Ping, H.C.; Lim, S.H.E. Essential oils, a new horizon in combating bacterial drug resistance. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 8, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wińska, K.; Mączka, W.; Łyczko, J.; Grabarczyk, M.; Czubaszek, A.; Szumny, A. Essential Oils as Antimicrobial Agents—Myth or Real Alternative? Molecules 2019, 24, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, P.S.X.; Lim, S.H.E.; Hu, C.P.; Yiap, B.C. Combination of Essential Oils and Antibiotics Reduce Antibiotic Resistance in Plasmid-Conferred Multidrug Resistant Bacteria. Phytomedicine 2013, 20, 710–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visan, A.I.; Negut, I. Coatings Based on Essential Oils for Combating Antibiotic Resistance. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabri, C.; Kadiri, F.Z.; Sabri, S.; Razzak, S.; Salam, M.R.; Taboz, Y. Antimicrobial Efficacy and Chemical Composition of Essential Oils from Moroccan Medicinal Plants against Multidrug-Resistant Salmonella Strains. World Vet. J. 2025, 15, 292–304. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Tian, Q.; Husien, H.M.; Tao, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Bo, R.; Li, J. The Synergy of Tea Tree Oil Nano-Emulsion and Antibiotics against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxad131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbad, I.; Soulaimani, B.; Iriti, M.; Barakate, M. Chemical Composition and Synergistic Antimicrobial Effects of Essential Oils from Four Commonly Used Satureja Species in Combination with Two Conventional Antibiotics. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, 20240–22093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbaoui, A.; Jamaly, N.; Aneb, M.H.; Idrissi, A.; Bouksaim, M.; Gmouh, S.; Amzazi, S.; Moussaouiti, M.E.; Benjouad, A.; Bakri, Y.; et al. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils from Six Moroccan Plants. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 4593–4600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqhrammullah, M.; Rizki, D.R.; Purnama, A. Antiviral Molecular Targets of Essential Oils Against SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsebai, M.F.; Albalawi, M.A. Essential Oils and COVID-19. Molecules 2022, 27, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, J.; Salehi, B.; Schnitzler, P.; Kobarfard, F.; Fathi, M.; Eisazadeh, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M. Susceptibility of herpes simplex virus type 1 to monoterpenes thymol, carvacrol, p-cymene and essential oils of Sinapis arvensis L.; Lallemantia royleana Benth. and Pulicaria vulgaris Gaertn. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 63, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Neto, L.; Monteiro, M.L.G.; Fernández-Romero, J.; Teleshova, N.; Sailer, J. Essential oils block cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 delta variant. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, L.C.A.; Filomeno, C.A.; Teixeira, R.R. Chemical variability and biological activities of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils. Molecules 2016, 21, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Orav, A.; Karileet, M.; Džaniašvili, M.; Koliadzhyn, T.; Grytsyk, A.; Koshovyi, O. Variation in the composition of the essential oil of commercial Artemisia absinthium L. herb samples from different countries. ScienciRise Pharm. Sci. 2024, 2, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Malaspina, P.; Polito, F.; Mainetti, A.; Khedhri, S.; De Feo, V.; Cornara, L. Exploring chemical variability in the essential oil of Artemisia absinthium L. in relation to different phenological stages and geographical location. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e00743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán-Atero, R.; Aghababaei, F.; Rodríguez García, S.; Hasiri, Z.; Ziogkas, D.; Moreno, A.; Hadidi, M. Clove essential oil: Chemical profile, biological activities, encapsulation strategies, and food applications. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathy, H.M.; Ahmed, M.N.; Goda, H.A.; Moselhy, M.A. Thyme essential oil potentials as a bactericidal and biofilm-preventive agent against prevalent bacterial pathogens. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 31644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ickovski, J.D.; Jovanović, O.P.; Zlatković, B.K.; Đorđević, M.M.; Stepić, K.D.; Ljupković, R.B.; Stojanović, G.S. Variations in the composition of essential oils of selected Artemisia species as a function of soil type. J. Serbian Chem. Soc. 2021, 86, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aati, H.Y.; Sarawi, W.; Attia, H.; Ghazwani, R.; Aldmaine, L. Exploring the phytochemical profile and therapeutic potential of Saudi native Santolina chamaecyparissus L. essential oil. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Deepa, N.; Chauhan, S.; Tandon, S.; Verma, R.S.; Singh, A. Antifungal action of 1,8-cineole, a major component of Eucalyptus globulus essential oil, against Alternaria tenuissima via overproduction of reactive oxygen species and downregulation of virulence and ergosterol biosynthetic genes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 214, 118580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, M.; Lončar, B.; Cvetković, M.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Vujisić, L.; Puvača, N.; Pezo, L. Correlation between weather conditions and volatile organic compound profiles in Artemisia absinthium L. essential oil and recovery oil from hydrolate. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2025, 122, 105029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggini, V.; Semenzato, G.; Gallo, E.; Nunziata, A.; Fani, R.; Firenzuoli, F. Antimicrobial activity of Syzygium aromaticum essential oil in human health treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijałkowska, A.; Wesołowska, A.; Rakoczy, R.; Jedrzejczak-Silicka, M. A comparative study of thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) essential oils and thymol—Differences in chemical composition and cytotoxicity. Chem. Process Eng. New Front. 2024, 45, e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A.; Rosselli, S.; Bruno, M.; Spadaro, V.; Raimondo, F.M.; Senatore, F. Chemical composition of essential oil from Italian populations of Artemisia alba Turra (Asteraceae). Molecules 2012, 17, 10232–10241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončar, B.; Cvetković, M.; Rat, M.; Stanković Jeremić, J.; Filipović, J.; Pezo, L.; Aćimović, M. Chemical composition, chemometric analysis, and sensory profile of Santolina chamaecyparissus L. (Asteraceae) essential oil: Insights from a case study in Serbia and literature-based review. Separations 2025, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakallı, E.A.; Teralı, K.; Karadağ, A.E.; Biltekin, S.N.; Koşar, M.; Demirci, B.; Başer, K.H.; Demirci, F. In vitro and in silico evaluation of ACE2 and LOX inhibitory activity of Eucalyptus essential oils, 1,8-cineole, and citronellal. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2022, 17, 1934578X221109409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chialva, F.; Liddle, P.A.P.; Doglia, M.; Rossi, M. Lebensmittel-Untersuchung und-Forschung Chemotaxonomy of Wormwood (Artemisia Absinthum, L.) I. Composition of the Essential Oil of Several Chemotypes Chemotaxonomie von Wermut (Artemisia Absinthum L.). Z. Lebensm. Unters. Forsch. 1983, 176, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Mohamed, D.; Khawla, N.; Rafii, S.; Keltoum, E.B. Chemical composition and toxicity of Moroccan mentha spicata and artemisia absinthium essential oils against phthorimaea operculella, the potato moth. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 39, 3011–3020. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaeinodehi, A.; Khangholi, S. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Artemisia absinthium growing wild in Iran. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2008, 11, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, P.; Radulović, N.; Palić, R.; Stojanović, G. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Serbian wild-growing Artemisia absinthium and Artemisia vulgaris. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 4780–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucciarelli, M.; Caramiello, R.; Maffei, M.; Chialva, F. Essential oils from some Artemisia species growing spontaneously in North-West Italy. Flavour Fragr. J. 1995, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezhadali, A.; Parsa, M. Study of the Volatile Compounds in Artemisia Sagebrush from Iran using HS/SPME/GC/MS. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2010, 1, 287–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Baker, D.H.; Amarowicz, R.; Kandeil, A.; Ali, M.A. Antiviral activity of Lavandula angustifolia L. and Salvia officinalis L. essential oils against avian influenza H5N1 virus. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 4, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Ouazzou Loran, S.; Bakkali, B.; Laglaoui, A.; Rota, C. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Thymus algeriensis, Eucalyptus globulus and Rosmarinus officinalis from Morocco. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 14, 2643–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkat-Madouri, L. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus from Algeria. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 78, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čmiková, N. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of Eucalyptus globulus Essential Oil. Plants 2023, 12, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almas, I.; Innocent, E.; Machumi, F.; Kisinza, W. Chemical composition of essential oils from Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus maculata grown in Tanzania. Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başer, K.H.; Karadağ, A.E.; Biltekin, S.N.; Ertürk, M.; Demirci, F. In vitro antiviral evaluations of Coldmix®: An essential oil blend against SARS-CoV-2. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Nie, Y.-K.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Guo, D.-Y. Antiviral properties of the natural product eugenol: A review. Fitoterapia 2025, 185, 106674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, H.; Ali, F. Essential oil composition of artemisia herba-alba from Southern Tunisia. Molecules 2009, 14, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa-Hedeab, G.; Hegazy, A.; Mostafa, I.; Eissa, I.H.; Metwaly, A.M.; Elhady, H.A.; Eledrdery, A.Y.; Alruwaili, S.H.; Alibrahim, A.O.; Alenazy, F.O.; et al. In vitro antiviral activities of thymol and limonin against influenza A viruses and SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salido, S.; Valenzuela, L.R.; Altarejos, J.; Nogueras, M.; Sánchez, A.; Cano, E. Composition and infraspecific variability of Artemisia herba-alba from southern Spain. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dra, A. Effectiveness of essential oil from the artemisia herba-alba aerial parts against multidrug-resistant bacteria isolated from food and hospitalized patients. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 2995–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houti, H. Moroccan Endemic Artemisia herba-alba Essential Oil: GC-MS Analysis and Antibacterial and Antifungal Investigation. Separations 2023, 10, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaćković, P. Composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils of Artemisia judaica, A. Herba-Alba and A. arborescens from Libya. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2015, 67, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, G.; Caputo, L.; La Storia, A.; De Feo, V.; Mauriello, G.; Fechtali, T. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of artemisia herba-alba and origanum majorana essential oils from Morocco. Molecules 2019, 24, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad Khubeiz, M.; Mansour, G. In Vitro Antifungal, Antimicrobial Properties and Chemical Composition of Santolina chamaecyparissus Essential Oil in Syria. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 8, 372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Demirci, B.; Özek, T.; Baser, K.H.C. Chemical composition of Santolina chamaecyparissus L. Essential oil. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2011, 12, 625–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel Hadj Salah-Fatnassi, K.; Hassayoun, F.; Cheraif, I.; Khan, S.; Jannet, H.B.; Hammami, M.; Aouni, M.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antifungal activities of flowerhead and root essential oils of Santolina chamaecyparissus L., growing wild in Tunisia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djeddi, S.; Djebile, K.; Hadjbourega, G.; Achour, Z.; Argyropoulou, C.; Skaltsa, H. In vitro Antimicrobial Properties and Chemical Composition of Santolina chamaecyparissus Essential Oil from Algeria. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1934578X1200700735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorizzi, M. Starfish Saponins, 52. Chemical Constituents from the Starfish Echinaster brasiliensis. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 2149–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognolini, M. Comparative screening of plant essential oils: Phenylpropanoid moiety as basic core for antiplatelet activity. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1419–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan Elsharkawy, E. Antitcancer effect and Seasonal variation in oil constituents of Santolina chamaecyparissus. Chem. Mater. Res. 2014, 6, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, N.; Kronenberger, T.; Xie, H.; Rocha, C.; Pöhlmann, S.; Su, H.; Xu, Y.; Laufer, S.A.; Pillaiyar, T. Discovery of polyphenolic natural products as SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors for COVID-19. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitkar, S. Cytotoxic effects on cancerous and non-cancerous cells of trans-cinnamaldehyde, carvacrol, and eugenol. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 95394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, A.N.; Abed, I.J. Evaluating the in vitro cytotoxicity of thymus vulgaris Essential Oil on MCF-7 and HeLa cancer cell lines. Iraqi J. Sci. 2021, 62, 2862–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorn, T.; Peter, K.; Plinkert, P.T.; Efferth, T. Cytotoxicity of Thymus vulgaris Essential Oil Towards Human Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2011, 31, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, C.; Dal Sasso, M.; Culici, M.; Bianchi, T.; Bordoni, L.; Marabini, L. Anti-inflammatory activity of thymol: Inhibitory effect on the release of human neutrophil Elastase. Pharmacology 2006, 77, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćavar Zeljković, S.; Schadich, E.; Džubák, P.; Hajdúch, M.; Tarkowski, P. Antiviral Activity of Selected Lamiaceae Essential Oils and Their Monoterpenes Against SARS-CoV-2. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 893634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazraei, H.; Shamsdin, S.A.; Zamani, M. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Apoptotic Assay of Eucalyptus globulus Essential Oil in Colon and Liver Cancer Cell Lines. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2022, 53, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benencia, F.; Courrges, M.C. In vitro and in vivo activity of eugenol on human herpesvirus. Phytother. Res. 2000, 14, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, T.; Faustino-Rocha, A.I.; Barros, L.; Finimundy, T.C.; Matos, M.; Oliveira, P.A. Santolina chamaecyparissus L.: A Brief Overview of Its Medicinal Properties. Med. Sci. Forum 2023, 8, 14281. [Google Scholar]

- Elsharkawy, E.; Aljohar, H. Anticancer screening of medicinal plants growing in the Northern Region of Saudi Arabia. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2016, 6, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliszczyńska, A.; Łysek, A.T.; Janeczko Świtalska, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Wawrzeńczyk, C. Microbial transformation of (+)-nootkatone and the antiproliferative activity of its metabolites. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 2464–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-B.; Li, J.-L.; Xu, F.-F.; Han, X.-D.; Wu, Y.-S.; Liu, B. (+)-Nootkatone: Progresses in Synthesis, Structural Modifications, Pharmacology and Ecology Uses. Curr. Chin. Sci. 2022, 2, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshirsagar, S.G.; Rao, R.V. Antiviral and immunomodulation effects of artemisia. Medicina 2021, 57, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.A. Phytochemical Analysis, Antioxidant Potential, and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Traditionally Used Artemisia absinthium L. (Wormwood) Growing in the Central Region of Saudi Arabia. Plants 2022, 11, 11081028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilaoui, M.; Mouse, H.A.; Jaafari, A.; Zyad, A. Comparative phytochemical analysis of essential oils from different biological parts of artemisia herba alba and their cytotoxic effect on cancer cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 131799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, B.; Vasilijević, B.; Mitić-Ćulafić, D.; Vuković-Gačić, B.; Knežević-Vukćević, J. Comparative study of genotoxic, antigenotoxic and cytotoxic activities of monoterpenes camphor, eucalyptol and thujone in bacteria and mammalian cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2015, 242, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díaz, R.A. Trypanocidal, trichomonacidal and cytotoxic components of cultivated Artemisia absinthium Linnaeus (Asteraceae) essential oil. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2015, 110, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassolé, I.H.N.; Juliani, H.R. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules 2012, 17, 3989–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, C.P.; Cui, B.; Zhang, H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tran, H.D.; Tran, D.K.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Tran, D.X. Characterization of (2E,6E)-3,7,11-Trimethyldodeca-2,6,10-Trien-1-Ol (farnesol) with antioxidant and antimicrobial potentials from Euclea crispa (Thunb.) leaves. Int. Lett. Nat. Sci. 2020, 80, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaara, M. Agents That Increase the Permeability of the Outer Membrane. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, H.P. Efflux as a mechanism of resistance to antimicrobials in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and related bacteria: Unanswered questions. Genet. Mol. Res. 2003, 1, 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- Pyo, Y.; Jung, Y.J. Microbial Fermentation and Therapeutic Potential of p-Cymene: Insights into Biosynthesis and Antimicrobial Bioactivity. Fermentation 2024, 10, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.R.R.; Fernandes, C.C.; Gonçalves, D.S.; Martins, C.H.G.; Miranda, M.L.D. Chemical composition and anti- Xanthomonas citri activities of essential oils from Schinus molle L. fresh and dry leaves and of its major constituent spathulenol. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 38, 3476–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, A. Antimicrobial activity of eugenol and essential oils containing eugenol: A mechanistic viewpoint. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 43, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilia, A.R.; Santomauro, F.; Sacco, C.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Donato, R. Essential Oil of Artemisia annua L.: An Extraordinary Component with Numerous Antimicrobial Properties. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 1, 159819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacomin, A.C.; Buhl, B.; Klegin, C.; Hoehne, L.; Ferla, N.J.; Ethur, E.M. Antimicrobial activity and synergistic effect of carvacrol and thymol against foodborne pathogens. Cuad. Educ. Y Desarro. 2024, 16, 6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud Abd El-Baky, R.; Shawky, Z. Eugenol and linalool: Comparison of their antibacterial and antifungal activities. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 10, 1860–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, J.S.; Karuppayil, S.M. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oils. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Luo, D.; Miao, Y.; Gui, C.; Liu, Q.; Liu, D. Comparative transcriptome analysis of high- and low-thujone-producing Artemisia argyi reveals candidate genes for thujone synthetic and regulatory pathway. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakowska, O.; Węglarz, Z.; Żuchowska, A.; Styczyńska, S.; Zaraś, E.; Bączek, K. Intraspecific variability of wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) occurring in Poland in respect of developmental and chemical traits. Plants 2025, 14, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajimehdipoor, H.; Zahedi, H.; Kalantari Khandani, N.; Abedi, Z.; Pirali-Hamedani, M.; Adib, N. Investigation of α- and β-thujone content in common wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) from Iran. J. Med. Plants 2008, 7, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guidolotti, G.; Pallozzi, E.; Gavrichkova, O.; Scartazza, A.; Mattioni, M.; Loreto, F.; Calfapietra, C. Emission of constitutive isoprene, induced monoterpenes, and other volatiles under high temperatures in Eucalyptus camaldulensis: A 13C labelling study. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaissi, A.; Rouis, Z.; Abid Ben Salem, N.; Mabrouk, S.; Ben Salem, Y.; Bel Haj Salah, K.; Aouni, M.; Farhat, F.; Chemli, R.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F.; et al. Chemical composition of 8 eucalyptus species’ essential oils and the evaluation of their antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activities. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 28, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, K.; Gupta, R.; Bhise, S.; Bansal, M. Effect of hydro-distillation process on extraction time and oil recovery at various moisture contents from Mentha leaves. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Res. Inven. 2014, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Naghdi Badi, H.; Abdollahi, M.; Mehrafarin, A.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Tolyat, M.; Qaderi, A.; Ghiaci Yekta, M. An overview on two valuable natural and bioactive compounds, thymol and carvacrol, in medicinal plants. J. Med. Plants 2017, 16, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, H.; Fatahi, R.; Zamani, Z.; Shokrpour, M.; Sheikh-Assadi, M.; Poczai, P. RNA-seq analysis reveals narrow differential gene expression in MEP and MVA pathways responsible for phytochemical divergence in extreme genotypes of Thymus daenensis Celak. BMC Genom. 2024, 4, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yang, B. Extraction of essential oils from five cinnamon leaves and identification of their volatile compound compositions. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2009, 10, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repetto, G.; del Peso, A.; Zurita, J.L. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/ cytotoxicity. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 3, 1125–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, J.H.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Alexander, B.D.; Andes, D.; Brown, S.D.; Diekema, D.J.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Fowler, C.L.; Johnson, E.M.; Knapp, C.C.; et al. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts: Approved Guideline, 2nd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kaboré, D.; Ouedraogo, M.; Kaboré, F.; Lompo, M.; Bonzi-Coulibaly, Y.L.; Bassolé, I.H.N. Biochemical Characterization and Antimicrobial Properties of Extracts from Four Food Plants Traditionally Used to Improve Drinking Water Quality in Rural Areas of Burkina Faso. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).