Abstract

The Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) has been linked with physical and mental health benefits. Previous research, however, suggests that adoption and adherence to a Mediterranean diet might be difficult for people who live outside of the Mediterranean region. The aim of this systematic review was to investigate the factors that influence adoption and adherence to a Mediterranean style diet in adults aged 18 years old and over, as identified in published observational and qualitative studies. Following registration of our protocol on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42018116515), observational and qualitative studies of adults’ perceptions and experiences relevant to following a Mediterranean style diet were identified using systematic searches of databases: MEDLINE, the Cochane Library, CINAHL, Web of Science and Scopus, over all years of records until February 2022. A narrative synthesis was then undertaken. Of 4559 retrieved articles, 18 studies fulfilled our inclusion criteria and were included. Factors influencing adoption and adherence to a MedDiet were identified and categorized as: financial, cognitive, socio-cultural, motivational, lifestyle, accessibility & availability, sensory & hedonic and demographic. Similar barriers and facilitators are often reported in relation to healthy eating or the consumption of specific healthy foods, with a few exceptions. These exceptions detailed concerns with specific components of the MedDiet; considerations due to culture and traditions, and concerns over a cooler climate. Suggestions for overcoming these barriers and facilitators specific to adoption and adherence to the Mediterranean diet are offered. These data will inform the development of future studies of robust methodology in eating behaviour change which offer pragmatic approaches for people to consume and maintain healthy diets.

Keywords:

Mediterranean diet; MedDiet; barriers; facilitators; adoption; adherence; adults; systematic review 1. Introduction

The Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) reflects the typical traditional dietary pattern of the Mediterranean region. It is characterized by the daily consumption of fruit and vegetables, a high consumption of unrefined whole grains and pulses, and a high consumption of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), primarily from olive oil. It also includes a moderate consumption of fish and alcohol, predominantly in the form of red wine, a low-to-moderate intake of dairy products (usually in the form of yogurt and cheese), and a low consumption of poultry and red meats [1].

Observational research demonstrates a protective role for the MedDiet for many global health concerns, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), recurrent cardiac events and CVD mortality [2], metabolic syndrome [3], abdominal adiposity [1], and excessive gestational weight gain [4]. Further evidence justifying the promotion of the MedDiet for health benefit comes from randomized trials [2]. For instance, the PREDIMED study showed that a MedDiet supplemented with nuts could exert a beneficial effect on CVD risk and several secondary outcomes [5]. Studies during pregnancy reveal that greater adherence to a MedDiet may protect against offspring cardiometabolic risk [6], and prospective studies among pregnant women, showed that low MedDiet adherence was associated with higher blood pressure and preeclampsia risk [7,8].

While health benefits are recognised however, adoption and adherence to the MedDiet outside of the Mediterranean region entail difficulties and rates of adherence are decreasing in Mediterranean and southern Europe [9]. Studies suggest various barriers to the consumption of a Mediterranean style diet, but a comprehensive account may be informative. This work aimed to identify all studies investigating any barriers or facilitators to adopting or adhering to a Mediterranean style diet, in order to obtain an evidence-based insight of reasons that influence MedDiet adoption and adherence. To the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has yet been undertaken with this aim.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was conducted following the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD)’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care [10]. Barriers and facilitators to following a MedDiet were compiled according to defined outcome categories. Methods and inclusion/exclusion criteria were determined in advance and a protocol for the review was developed and sent to an advisory group of the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The protocol was published in PROSPERO on 23 November, 2018 (registration no. CRD42018116515).

2.1. Systematic Search Strategy

Search terms were generated by team discussion and an initial review of the literature. Relevant words were combined using logical ANDs and ORs to create one search string that included terms related to “Mediterranean diet”, “barriers”, “facilitators” and “adults”. This search string was: (“Mediterranean diet”* OR med-diet OR MD OR “Mediterranean style diet”* OR “Mediterranean-style diet”*) AND ((Barrier* OR obstacle* OR difficult*) OR (enabler* OR facilitator* OR factor* OR reason* OR determinant* OR motivator* OR characteristic*)) AND (adult* OR mature* OR elder* OR aged).

Electronic databases: MEDLINE, the Cochrane library, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Science and Scopus were investigated from inception by searching in “title”, “abstract” and “keywords” fields until February, 2022. Searches were not limited by study design, but they were limited by language of publication, where only English articles were considered. Search results were exported into EndNote, duplicates were deleted, and the remainder imported into COVIDence (www.COVIDence.org (accessed on 1 January 2019)) [11]. All studies were initially independently screened on titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria by two researchers (FT, DV) with no conflicts. Full texts for all potentially eligible papers were obtained. Citation tracking and reference lists of all retrieved articles were also reviewed by hand for any further eligible articles.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The review included only observational and qualitative studies. Any observational (e.g., cross-sectional, cohort) study was acceptable. Studies were included if they reported on factors that influence the adoption of or adherence to a Mediterranean style diet or a dietary intervention that includes similar food patterns, in adults aged 18 years and older. Only peer reviewed full journal papers, published in English, were included. Studies were excluded if they focused on children or adolescents; if they focussed on diets other than the MedDiet, such as a vegetarian diet or PALEO diet; if they included only single components of a MedDiet (where we considered “fruit and vegetables” as a single component), and if they were not published in English. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were piloted by three researchers (FT, DV, KA). Then, the assessment was performed for the full list of identified studies by two researchers (DV, FT). Disagreements were resolved between the two researchers or by consultation with a third author (CH or KA).

2.3. Data Extraction

Data from all studies were subsequently extracted by two researchers (FT, DV) using the COVIDence tool, an online tool designed to streamline the process of conducting a systematic review [11]. Data on each study included details of country of origin, participant demographics, sample size, data collection method and outcomes. Data on factors influencing adoption or adherence to the MedDiet included all reported barriers and facilitators. Factors were categorized as: availability/accessibility (relating to procurement); cognitive (relating to knowledge, thoughts and understanding); demographic (relating to gender, age, socio-economic status); financial (relating to cost and financial concerns); lifestyle (relating to other lifestyle characteristics, e.g., physical activity, smoking habits); motivational (relating to willingness); sensory & hedonic (relating to sensory aspects of foods, including liking and pleasure); and socio-cultural (relating to societal and cultural concerns). All barriers and facilitators were included in the review, regardless of the frequency/number of respondents who reported them. Other researchers (CH, KA) independently checked the extracted data for accuracy and completeness, and uncertainties were resolved by discussion. Uncertainties considered the categorisation of barriers and facilitators, and variations in reporting style between papers.

2.4. Risk of Bias

All included studies were also assessed for risk of bias. Risk of bias in observational studies was evaluated using the STROBE Statement for Observational Studies in Nutritional Epidemiology [12] and risk of bias in qualitative studies was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool [13]. Two authors (FT, DV) independently evaluated the included studies, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion. Final judgements were summed to provide a total score.

3. Results

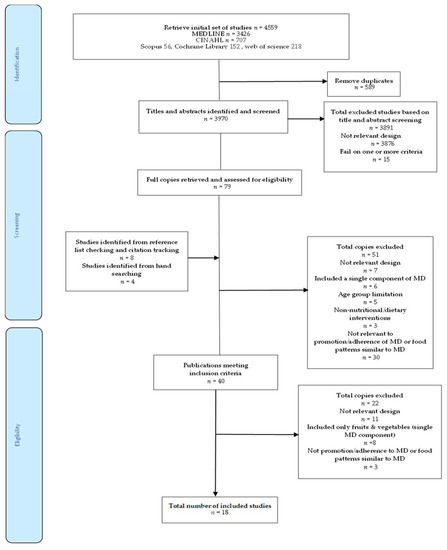

Searches were most recently conducted on 22 February 2022 to result in the identification of 4559 citations, of which 79 were screened on full text. In total, 18 studies were included in the review. The detailed study selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of the search strategy and study selection process.

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

Characteristics of the included studies and ratings of risk of bias are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Of the 18 included studies, 12 were observational studies, all cross-sectional in design [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], and 6 were qualitative studies [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Four studies, all qualitative [26,27,28,30] were related to adoption of MedDiet and 14 studies, both qualitative [29,31] and observation studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] were related to adherence to MedDiet. Four studies were based in Mediterranean regions—one each from Italy [14] and Greece [17], and two from Spain [15,16], and all others were conducted in non-Mediterranean regions. Seven of these studies were conducted in the United Kingdom [22,23,25,26,28,29,30] four studies were conducted in the USA [17,18,20,21], two studies were conducted in Australia [24,31] and one was conducted in the Netherlands [19].

Table 1.

Observational studies investigating barriers or facilitators to adopting or adhering to a Mediterranean style diet.

Table 2.

Qualitative studies investigating barriers or facilitators to adopting or adhering to a Mediterranean style diet.

Sample sizes ranged from 11 participants [29] to 67 participants [30] for the qualitative studies and from 236 participants [17] to 36,032 participants [14] for the observational studies. Two studies included females only [16,28].

3.2. Findings of Included Studies

Barriers and facilitators in all eight categories are given in Table 3. Many barriers and facilitators were reported, and barriers and facilitators were identified within all eight categories.

Table 3.

Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to adoption or adherence to Mediterranean diet.

In relation to availability and accessibility, barriers included difficulties in accessing suitable foods, due to limited availability, choice and possibly due to season, and facilitators included good access to foods in general, e.g., due to good access to preferred retail outlets and suitable food provision in catering outlets. Linked to accessibility, high food costs were also reported as barriers to MedDiet consumption, high relative food costs (high food insecurity) or the increased consumption of foods that are perishable and so may result in increased food waste. Conversely however, financial facilitators included consideration that the MedDiet is good value for money and the recognition that many foods that are consumed in large quantities within the diet are relatively cheap, while more expensive food items, such as meat, should be consumed less often. Low income was also given as a financial barrier, as was a lower level (non-managerial/non-professional) occupation. Gender, age and education were other demographic barriers and facilitators, such that following a MedDiet was more likely in females, older individuals, and those with a higher education. Related lifestyle characteristics included physical activity habits, smoking habits, obesity and the presence of medical concerns and conditions.

In the cognitive domain, barriers included a lack of knowledge of the MedDiet, a lack of knowledge of the details of the diet, e.g., which specific foods were included and how these could be incorporated into meals, and a lack of knowledge of the value of the diet for health, or confusions and concerns over the health implications of some of the food components. Facilitators included perceptions of improved diet quality, including the consideration of naturalness, a range of health benefits and positive outcomes, affecting physical health, body-weight and well-being, and some environmental benefits. Sensory and hedonic barriers and facilitators focused on the taste, smell and pleasure to be gained from recommended foods, the loss of pleasure as a result of giving up foods that should be consumed in lower quantities, and degree of familiarity with the recommended foods. Motivational facilitators included factors such as high self-efficacy, high self-regulation and willingness to change, while motivational barriers considered the reverse, plus some concerns over restriction. Socio-cultural barriers and facilitators included aspects of the individual’s family and living circumstances, type of upbringing, aspects of the individual’s lifestyle and situation, e.g., working night shifts, time available for cooking, cooking skills, and aspects of the wider culture, including the climate. In relation to the wider culture, cultural differences, such as traditional meal patterns and traditional dining patterns were reported as barriers, and changes to these patterns were reported as facilitators. Similarly, a cold climate was reported as a barrier, while a warm climate was a facilitator.

4. Discussion

The present research aimed to systematically identify and summarize all published observational and qualitative studies that investigated barriers and facilitators influencing adoption and adherence to a Mediterranean style diet. Our searches identified twelve observational studies, and six qualitative studies. A number of barriers and facilitators were found for each of the categories.

These barriers and facilitators are largely reported also in relation to healthy eating, or the consumption of specific healthy food items, such as fruits and vegetables. Poor availability and accessibility are a commonly reported barrier to healthy eating [31,32], but specific foods that form part of the MedDiet may incur specific concerns. There can be limited access to a range of MedDiet components in shops and supermarkets in non- Mediterranean regions, for example [2].

Financial concerns are also frequently reported as barriers to healthy eating [32,33,34,35,36], alongside perceptions that healthier diets or dietary patterns closer to dietary guidelines are more expensive or poorer value for money due to lower energy content or likely food waste [32,34,37]. A Mediterranean dietary pattern has even been explicitly demonstrated as more expensive than some Western diets [35,38]. Higher household income is also often positively associated with higher diet quality in adults [39], while lower household incomes have been consistently associated with poorer diet quality [34,40]. Some research also suggests higher costs to be associated with the consumption of specific key components of the MedDiet [38], but Goulet et al. [41] using a nutritional intervention promoting a Mediterranean food pattern in North America, found a negative association between adherence to MedDiet and an increase of daily food expenses.

Healthy eating is well recognised as socially patterned, based on gender, age, socio-economic status, income and education [42,43,44,45,46,47], and tends to co-exist with other healthy lifestyle behaviours, such as non-smoking and higher levels of physical activity [15,44,45,46]. Cognitive factors, such as a lack of knowledge or concerns and confusions over knowledge [37,48,49], motivational factors, such as a lack of willpower [22,33,36,37,45], and sensory or hedonic factors [22,33,34,36,43,45,48] are also frequently reported. Specific challenges to following the MedDiet in this respect, might be low liking or a low familiarity with some of the specific tastes and food items to be included.

Living situation or aspects of the living situation, such as an unsupportive partner, too little time or inadequate cooking skills are also relevant to healthy eating [24,32,33,34,36,37,45], but again specific concerns may arise over some of the specific food components of the MedDiet. The MedDiet, for example, is high in pulses and legumes, and lack of knowledge or confidence in how to best prepare pulses has been found to hinder the regular consumption of pulse-centric diets [50]. Concerns over cultural differences, such as changes to traditional meal patterns and traditional dining patterns and perceptions around unsuitable climate may similarly by specific to adoption and adherence to the MedDiet. Previous research also highlights the difficulty of the transferability of the MedDiet to non-Mediterranean countries [3].

Barriers and facilitators that are specific to the MedDiet, thus, detailed concerns with specific components of the MedDiet, considerations due to culture and traditions, and concerns over a cooler climate. Components of the MedDiet of concern included the high amount of olive oil to be consumed, which can be expensive and was considered to potentially lead to weight gain, the high consumption of pulses and legumes, which can be time-consuming and difficult to cook, or can be difficult to make tasty and pleasurable, the moderate consumption of fish, which for some people is unappealing and the low consumption of red meat which again for some can be unappealing. Suggestions to overcome knowledge-based concerns include education on the value of all food components for health and wellbeing [3,50,51], and on the value of all foods combined [3,51]. Benefit may be gained particularly from education on benefits for body weight or appearance [31,33,37]. Suggestions to overcome financial concerns may also lie in education, on the low cost of some MedDiet components, such as pulses and legumes [41,51], or on possible alternatives to some food components to create an adapted version of a Mediterranean style diet, e.g., through the use of locally available rapeseed oil and nuts [51,52,53]. Suggestions to overcome sensory and hedonic concerns may again benefit from increased choice in local markets, for fish, fruits and vegetables, plus the promotion of recipes and tastings [51]. Suggestions to overcome practical concerns include the increased availability of pre-prepared foods, the promotion of simple and easy recipes [36,50,51], and the promotion of cooking classes and skill development [34,36,50].

In relation to culture, tradition and climate, few changes can be made to these external factors, but suggestions can again be made to change perceptions towards them. Recipes for warm dishes, for example, have been suggested to encourage the perception that the MedDiet is suitable for cooler climates [30,51]. Use of substitutions for some food components will increase perceptions of flexibility and allow perceived differences to be reduced [52,53]. Focus on the similarities between the eating patterns in different countries may also be helpful. Some tailoring specific to cultures, traditions and individual tastes may also be beneficial.

Strengths of the review include the use of systematic searches and processes, such that all processes were undertaken by two authors independently. The studies found represent the perceptions and experiences of over twenty-five thousand men and women from nine different countries. As limitations, the review only considered studies written in English, and focused only on healthy adults, and as a result, the findings may not be transferable to non-healthy and underage populations, or to some locations. We also did not search for unpublished studies, and only four studies were found that had been conducted within the Mediterranean region. Further studies would have allowed distinction between barriers and facilitators based on geographical location, and may have provided some insights specifically in relation to location and culture.

5. Conclusions

This synthesis of observational and qualitative studies provides insight into the barriers and facilitators that can influence adoption and adherence to a Mediterranean Diet in healthy adults. A range of barriers and facilitators were found. Similar barriers and facilitators are often reported in relation to healthy eating or the consumption of specific healthy foods, with a few exceptions. These exceptions detailed concerns with specific components of the MedDiet, e.g., the weight implications of a high fat consumption through increased oil and nut use, the cost of olive oil, the preparation time and skills required for consuming pulses; considerations due to culture and traditions, and concerns over a cooler climate. Suggestions for overcoming these barriers and facilitators specific to adoption and adherence to the Mediterranean diet are offered. These data will inform the development of future studies of rigorous designs and robust eating behaviour methodology, which can offer pragmatic approaches for people to consume and maintain healthy diets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, F.T. and K.M.A. Study design by D.V., K.M.A. and F.T. Data collection was performed by D.V. and F.T. with input from C.H. and K.M.A. when consensus was needed. All authors contributed to analysis. The draft was written by D.V. with assistance from F.T., C.H. and K.M.A. Supervision, F.T. and K.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The project was conducted as part of a Master’s by Research (MRes) project completed by Dimitrios Vlachos, supervised by Fotini Tsofliou and Katherine Appleton.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Romaguera, D.; Norat, T.; Mouw, T.; May, A.M.; Bamia, C.; Slimani, N.; Travier, N.; Besson, H.; Luan, J.; Wareham, N.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Lower Abdominal Adiposity in European Men and Women. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 1728–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-González, M.Á.; Hershey, M.S.; Zazpe, I.; Trichopoulou, A. Transferability of the Mediterranean Diet to Non-Mediterranean Countries. What Is and What Is Not the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortosa, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Basterra-Gortari, F.J.; Nuñez-Cordoba, J.M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. Mediterranean Diet Inversely Associated with the Incidence of Metabolic Syndrome: The Sun Prospective Cohort. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 2957–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spadafranca, A.; Piuri, G.; Bulfoni, C.; Liguori, I.; Battezzati, A.; Bertoli, S.; Speciani, A.F.; Ferrazzi, E. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Serum Adiponectin Levels in Pregnancy: Results from a Cohort Study in Normal Weight Caucasian Women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.-I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzi, L.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Georgiou, V.; Joung, K.E.; Koinaki, S.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Margioris, A.; Sarri, K.; Vassilaki, M.; Vafeiadi, M.; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet during Pregnancy and Offspring Adiposity and Cardiometabolic Traits in Childhood. Pediatric Obes. 2017, 12, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minhas, A.S.; Hong, X.; Wang, G.; Rhee, D.K.; Liu, T.; Zhang, M.; Michos, E.D.; Wang, X.; Mueller, N.T. Mediterranean-Style Diet and Risk of Preeclampsia by Race in the Boston Birth Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e022589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, S.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P.M.; Vujkovic, M.; Bakker, R.; den Breeijen, H.; Raat, H.; Russcher, H.; Lindemans, J.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; et al. Major Dietary Patterns and Blood Pressure Patterns during Pregnancy: The Generation R Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 1–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsofliou, F.; Theodoridis, X.; Arvanitidou, I. Chapter 14: Toward a Mediterranean-style diet outside the Mediterranean countries. In The Mediterranean Diet: An Evidence-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Preedy, V., Watson, R., Eds.; Academic Press Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- University of York. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic Reviews: Crd’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care, 3rd ed.; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: York, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kellermeyer, L.; Harnke, B.; Knight, S. Covidence and Rayyan. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörnell, A.; Berg, C.; Forsum, E.; Larsson, C.; Sonestedt, E.; Akesson, A.; Lachat, C.; Hawwash, D.; Kolsteren, P.; Byrnes, G.; et al. Perspective: An Extension of the Strobe Statement for Observational Studies in Nutritional Epidemiology (strobe-Nut): Explanation and Elaboration. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 652–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2019).

- Cavaliere, A.; Donzelli, F.; Banterle, A.; De Marchi, E. Is the Mediterranean Diet for All? An Analysis of Socioeconomic Inequalities and Food Consumption in Italy. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 1327–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, C.; Romaguera-Bosch, D.; Tauler-Riera, P.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Pericas-Beltran, J.; Martinez-Andreu, S.; Aguilo-Pons, A. Clustering of Lifestyle Factors in Spanish University Students: The Relationship between Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, Physical Activity and Diet Quality. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 2131–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmedo-Requena, R.; Fernández, J.G.; Prieto, C.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Bueno-Cavanillas, A.; Jiménez-Moleón, J.J. Factors Associated with a Low Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Pattern in Healthy Spanish Women Before Pregnancy. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodoridis, X.; Grammatikopoulou, M.G.; Gkiouras, K.; Papadopoulou, S.E.; Agorastou, T.; Gkika, I.; Maraki, M.I.; Dardavessis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Food Insecurity and Mediterranean Diet Adherence among Greek University Students. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, R.M.; Frugé, A.D.; Greene, M.W. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in a Portuguese Immigrant Community in the Central Valley of California. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, S.C.; Neter, J.E.; van Stralen, M.M.; Knol, D.L.; Brouwer, I.A.; Huisman, M.; Visser, M. The Role of Perceived Barriers in Explaining Socio-Economic Status Differences in Adherence to the Fruit, Vegetable and Fish Guidelines in Older Adults: A Mediation Study. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B.H.; Croff, J.; Wheeler, D.; Miller, B. Mediterranean Diet Adherence in Cardiac Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.J.; Jackson, O.; Rahman, I.; Burnett, D.O.; Frugé, A.D.; Greene, M.W. The Mediterranean Diet in the Stroke Belt: A Cross-Sectional Study on Adherence and Perceived Knowledge, Barriers, and Benefits. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.; McCrum, L.-A.; Mathers, J.C. Association of Mediterranean Diet and Other Health Behaviours with Barriers to Healthy Eating and Perceived Health among British Adults of Retirement Age. Maturitas 2014, 79, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, A.; Wood, L.; Sebire, S.J.; Jago, R. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among Employees in South West England: Formative Research to Inform a Web-Based, Work-Place Nutrition Intervention. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scannell, N.; Villani, A.; Swanepoel, L.; Mantzioris, E. Understanding the Self-Perceived Barriers and Enablers Toward Adopting a Mediterranean Diet in Australia: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour Framework. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, T.Y.N.; Imamura, F.; Monsivais, P.; Brage, S.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Dietary Cost Associated with Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet, and Its Variation by Socio-Economic Factors in the Uk Fenland Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, L.; Bremner, S.; Houghton, D.; Henderson, E.; Avery, L.; Hardy, T.; Hallsworth, K.; McPherson, S.; Anstee, Q.M. Barriers and Facilitators to Mediterranean Diet Adoption by Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Northern Europe. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2019, 17, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardin-Fanning, F. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet in a Rural Appalachian Food Desert. Rural Remote Health 2013, 13, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretowicz, H.; Hundley, V.; Tsofliou, F. Exploring the Perceived Barriers to Following a Mediterranean Style Diet in Childbearing Age: A Qualitative Study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, G.; Keegan, R.; Smith, M.F.; Alkhatib, A.; Klonizakis, M. Implementing a Mediterranean Diet Intervention into a Rct: Lessons Learned from a Non-Mediterranean Based Country. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2015, 19, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.E.; McEvoy, C.T.; Prior, L.; Lawton, J.; Patterson, C.C.; Kee, F.; Cupples, M.; Young, I.S.; Appleton, K.; McKinley, M.C.; et al. Barriers to Adopting a Mediterranean Diet in Northern European Adults at High Risk of Developing Cardiovascular Disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 31, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacharia, K.; Patterson, A.J.; English, C.; MacDonald-Wicks, L. Feasibility of the Ausmed Diet Program: Translating the Mediterranean Diet for Older Australians. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihlstrom, L.; Long, A.; Himmelgreen, D. Barriers and Facilitators to the Consumption of Fresh Produce among Food Pantry Clients. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, L.M.; Hutchesson, M.J.; Rollo, M.E.; Morgan, P.J.; Collins, C.E. Motivators and Barriers to Engaging in Healthy Eating and Physical Activity: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Young Adult Men. Am. J. Men’s Health 2017, 11, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Machín, L.; Girona, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Giménez, A. Comparison of Motives Underlying Food Choice and Barriers to Healthy Eating among Low Medium Income Consumers in Uruguay. Cad. De Saúde Pública 2017, 33, e00213315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, C.N.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Alonso, A.; Pimenta, A.M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Costs of Mediterranean and Western Dietary Patterns in a Spanish Cohort and Their Relationship with Prospective Weight Change. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andajani-Sutjahjo, S.; Ball, K.; Warren, N.; Inglis, V.; Crawford, D. Perceived Personal, Social and Environmental Barriers to Weight Maintenance among Young Women: A Community Survey. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2004, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munt, A.E.; Partridge, S.R.; Allman-Farinelli, M. The Barriers and Enablers of Healthy Eating among Young Adults: A Missing Piece of the Obesity Puzzle: A Scoping Review. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydén, P.; Sydner, Y.M.; Hagfors, L. Counting the Cost of Healthy Eating: A Swedish Comparison of Mediterranean-Style and Ordinary Diets. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, A.; Monsivais, P.; Drewnowski, A.; Cook, A.J. Does Diet Cost Mediate the Relation between Socioeconomic Position and Diet Quality? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition Quality of Food Purchases Varies by Household Income: The Shopper Study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulet, J.; Lamarche, B.; Lemieux, S. A Nutritional Intervention Promoting a Mediterranean Food Pattern Does Not Affect Total Daily Dietary Cost in North American Women in Free-Living Conditions. J. Nutr. 2008, 138, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; McGill, R.; Woodside, J.V. Fruit and vegetable consumption in older individuals in Northern Ireland: Levels and patterns. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; Dinnella, C.; Spinelli, S.; Morizet, D.; Saulais, L.; Hemingway, A.; Monteleone, E.; Depezay, L.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Hartwell, H. Consumption of a High Quantity and a Wide Variety of Vegetables Are Predicted by Different Food Choice Motives in Older Adults from France, Italy and the Uk. Nutrients 2017, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabshahi, S.; Lahmann, P.H.; Williams, G.M.; Marks, G.C.; van der Pols, J.C. Longitudinal Change in Diet Quality in Australian Adults Varies by Demographic, Socio-Economic, and Lifestyle Characteristics. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMorrow, L.; Ludbrook, A.; Olajide, D.; Macdiarmid, J.I. Perceived Barriers Towards Healthy Eating and Their Association with Fruit and Vegetable Consumption. J. Public Health 2017, 39, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, E.; Hunt, K.; Popham, F.; Benzeval, M.; Batty, G.D. The Role of Health Behaviours Across the Life Course in the Socioeconomic Patterning of All-Cause Mortality: The West of Scotland Twenty-07 Prospective Cohort Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 47, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schoufour, J.D.; de Jonge, E.A.L.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Hofman, A.; Nunn, S.P.T.; Franco, O.H. Socio-Economic Indicators and Diet Quality in an Older Population. Maturitas 2018, 107, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, K.M.; McGill, R.; Neville, C.; Woodside, J.V. Barriers to Increasing Fruit and Vegetable Intakes in the Older Population of Northern Ireland: Low Levels of Liking and Low Awareness of Current Recommendations. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, R.H. Adverse Outcomes Associated with Media Exposure to Contradictory Nutrition Messages. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didinger, C.; Thompson, H. Motivating Pulse-Centric Eating Patterns to Benefit Human and Environmental Well-Being. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Moore, S.E.; Erwin, C.M.; Kontogianni, M.; Wallace, S.M.; Appleton, K.M.; Cupples, M.E.; Hunter, S.J.; Kee, F.; McCance, D.; et al. Trial to Encourage Adoption and Maintenance of a Mediterranean Diet (team-Med): A Randomised Pilot Trial of a Peer Support Intervention for Dietary Behaviour Change in Adults from a Northern European Population at High Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 15, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Moore, S.E.; Appleton, K.M.; Cupples, M.E.; Erwin, C.; Kee, F.; Prior, L.; Young, I.S.; McKinley, M.C.; Woodside, J.V. Development of a Peer Support Intervention to Encourage Dietary Behaviour Change Towards a Mediterranean Diet in Adults at High Cardiovascular Risk. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, C.T.; Moore, S.E.; Appleton, K.M.; Cupples, M.E.; Erwin, C.M.; Hunter, S.J.; Kee, F.; McCance, D.; Patterson, C.C.; Young, I.S.; et al. Trial to Encourage Adoption and Maintenance of a Mediterranean Diet (team-Med): Protocol for a Randomised Feasibility Trial of a Peer Support Intervention for Dietary Behaviour Change in Adults at High Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).