Abstract

Coffee, tea, caffeinated soda, and energy drinks are important sources of caffeine in the diet but each present with other unique nutritional properties. We review how our increased knowledge and concern with regard to caffeine in the diet and its impact on human health has been translated into food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG). Using the Food and Agriculture Organization list of 90 countries with FBDG as a starting point, we found reference to caffeine or caffeine-containing beverages (CCB) in 81 FBDG and CCB consumption data (volume sales) for 56 of these countries. Tea and soda are the leading CCB sold in African and Asian/Pacific countries while coffee and soda are preferred in Europe, North America, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Key themes observed across FBDG include (i) caffeine-intake upper limits to avoid risks, (ii) CCB as replacements for plain water, (iii) CCB as added-sugar sources, and (iv) health benefits of CCB consumption. In summary, FBDG provide an unfavorable view of CCB by noting their potential adverse/unknown effects on special populations and their high sugar content, as well as their diuretic, psycho-stimulating, and nutrient inhibitory properties. Few FBDG balanced these messages with recent data supporting potential benefits of specific beverage types.

Keywords:

caffeine; coffee; tea; soda; energy drinks; mate; guidelines; country; consumption; population; public policy 1. Introduction

Caffeine is the most widely consumed psychostimulant in the world [1]. It occurs naturally in coffee beans, tea leaves, cocoa beans, and kola nuts, and is also added to foods and beverages. Important dietary sources include coffee, tea, yerba mate, caffeinated soda (cola-type), and energy drinks [2]. There is increasing public and scientific interest in the potential health consequences of habitual intake of these caffeine-containing beverages (CCB). Rigorous reviews of caffeine toxicity conclude that consumption of up to 400 mg caffeine/day in healthy adults is not associated with adverse effects [3,4,5]. Epidemiological studies support a beneficial role of moderate coffee intake in reducing risk of several chronic diseases, but heavy intake is likely harmful regarding pregnancy outcomes [6]. Health implications of regular tea, mate, and energy drink consumption are inconclusive and most concern for caffeinated soda intake currently pertains to its sugar content and relationship to obesity [7,8,9,10,11,12].

CCB also contribute a wealth of other compounds to the diet that have potential benefits or risks to health and thus it is imperative to consider the context (i.e., beverage type) in which caffeine is consumed [12,13,14,15,16]. Food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) provide context-specific advice on healthy diets that are evidence-based and respond to a country’s public health and nutrition priorities, sociocultural influences, and food production and consumption patterns, among other factors [17]. These factors change over time, and in turn, so do FBDG. Our knowledge and concern with regard to caffeine sources in the diet and their impact on human health has increased over the years. We therefore sought to review how such knowledge and concern has been translated into FBDGs and within the context of what each country actually consumes.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Data Collection Strategy for Dietary Caffeine Guidelines

Figure S1 outlines our data collection strategy. We initially used the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) website, which provided general food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) from each country (http://www.fao.org/nutrition/nutrition-education/food-dietary-guidelines/en/). Each country’s page included the most recent publication date of the guidelines, intended audience, general FBDG messages, downloadable guidelines if available, and contact information of those governmental institutions that established the guidelines.

The general messages from FAO were the first resource for any guidelines pertaining to caffeine or CCB including coffee, tea, yerba mate, energy drinks, and carbonated soft drinks. Beverages were a focus of the current review because they are the primary contributors of caffeine in the diet [2,18]. Other caffeine sources, such as products containing cocoa and kola nut, contribute relatively small amounts to the diet [18]. We considered guidelines for the broader categories of soft drinks or sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) since colas (typically containing caffeine) were rarely distinguished from these other beverages. Non-caffeine-containing teas were also considered because some FBDG provide different guideline for these teas and regular tea (i.e., black or green tea) that might provide additional insight into the underlying reason for the recommendations. We then accessed the downloadable materials if available to search for more caffeine-related messages. For materials published in foreign languages, we found translators using the Cochrane Task Exchange or personal contacts. Additionally, we used the contact information from the FAO page to inquire via email or web applications about any updated or additional caffeine-related guidelines that were not available via the FAO website. Finally, after these search efforts, for countries with limited or no information regarding dietary caffeine, we searched for publications related to national dietary guidelines and contacted the authors for further information.

Countries were classified according to the World Bank income classification [19]. We also used the non-comprehensive World Cancer Research Fund International NOURISHING database to identify actions in place by countries that attempt to regulate dietary caffeine consumption [20,21].

2.2. Data Resource for Dietary Caffeine Consumption

We adopted country-level volume sales of CCB as a proxy measure of CCB consumption and these were estimated using the Euromonitor Passport Global Market Information Database [22]. Euromonitor collects these data from trade associations, industry bodies, business press, company financial reports, and official government statistics. Specifically, we downloaded (bulk format) 2017 country-specific annual sales of (i) coffee, total brewed volume (liters); (ii) tea, total brewed volume (liters); (iii) “other hot drinks,” total brewed volume (liters); (iv) carbonates, total volume (liters); (v) sports and energy drinks, total volume (liters); (vi) ready-to-drink (RTD) coffee, total volume (liters); and vii) RTD tea, total volume (liters). For each country, data for each beverage was presented as a proportion of total CCB volume sales. Total CCB volume sales were also expressed on a per capita basis using total population estimates for 2017 (also downloaded from Euromonitor). For each country, we additionally reviewed the 2017 detailed report to collect information on the most common type or category of each beverage sold. Additional details for “sports and energy drinks,” RTD coffee and RTD tea were not systematically collected as they were not uniformly available across countries. Aside from including yerba mate, the “other hot drinks” category was deemed an unlikely key source of CCB and thus we only make reference to this category as appropriate.

3. Results

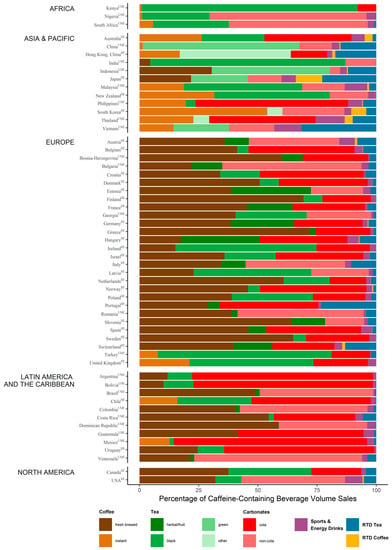

Using the FAO listing of the most recent FBDG from 90 countries as a starting point, we found any mentions of caffeine or CCB in 81 of these, which are summarized in Table 1. Sixty-six of these were published in the last ten years. The oldest guidelines were published by Venezuela (1991) and Greece (1999). Intended audiences for each FBDG are provided in Table S1. Most FBDG were intended for the general, healthy population over 2 years of age with several FBDG including specific guidelines for subgroups of the population such as children and pregnant/nursing mothers. Euromonitor annual volume sales of CCB in 2017 were available for 56 of the 90 FAO countries. Euromonitor data was not available for countries of the Near East (as defined by FAO). Figure 1 presents the percentage of caffeine-containing beverage volume sales per beverage per country. Subcategories of coffee, tea, and carbonates were assigned according to the most commonly, but not exclusively, consumed beverage type in that category. North America (defined by FAO as including Canada and USA) had the highest average country annual total CCB volume sales per capita (348 L/capita), followed by Europe (200 L/capita), Latin America and the Caribbean (153 L/capita), Asia and the Pacific (126 L/capita), and Africa (90 L/capita).

Table 1.

Country Specific Guidelines for Dietary Caffeine.

Figure 1.

Percentage of caffeine-containing beverage volume sales per beverage (Euromonitor 2017). Subcategories of coffee, tea, and carbonates were assigned according to the most commonly, but not exclusively, consumed beverage type in that category. Countries were classified by income based on World Bank 2017. HI: high-income; LI: low-income; LMI: lower-middle-income; UMI: upper-middle-income. Data for RTD beverages were incomplete for Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, India, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Estonia, Georgia, Latvia, Slovenia, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

3.1. Africa

The most commonly consumed CCB in African countries include tea and carbonated soda. Tea is typically of the black type while carbonated drinks are commonly non-cola-type (unlikely caffeinated including lime, ginger ale, tonic water, orange carbonates, and “other”). When coffee is consumed, it is usually of the regular (not decaffeinated, >95% of sales) and instant type. Data for RTD coffee/tea were not complete for these selected African countries.

Five African countries have published FBDG that consider dietary caffeine sources in some context. Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and South Africa discourage high coffee and tea intake because they inhibit iron bioavailability or increase phosphorous levels. South Africa’s guidelines for ages 5+ nevertheless support the intake of these beverages as a means to attain adequate fluid intake, further noting that any diuretic effects of caffeine are only a concern for individuals unaccustomed to regular caffeine intake. Most FBDG discourage caffeinated soda, but only due to their high sugar content.

3.2. Asia and the Pacific

Tea and carbonated soda are the leading CCB sold across Asia and the Pacific countries. High carbonated soda consuming countries prefer the cola type, while low consuming countries prefer non-colas. Black, green, and “other” teas are major tea types consumed. RTD teas are also popular in Japan, Hong Kong, and Vietnam. Most coffee that is consumed is of the regular (>97% of sales) and instant type; instant mixes (coffee, sugar, and cream powder) are especially popular in South Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam, and China.

Six of the fifteen included countries of Asia and the Pacific express caution concerning the iron inhibitory effects of coffee and tea, particularly when these beverages are consumed with meals. China, India, Indonesia, New Zealand, and Korea all advise pregnant and lactating women to minimize their intake of CCB. Indonesia and New Zealand further cite research supporting caffeine limits of 250–300 mg/day for these women. Potential diuretic effects of caffeine are discussed in guidelines for Fiji, Indonesia, and Malaysia. According to Fiji and Indonesia, heavy tea and coffee consumers may need to adjust their water intake, while Malaysian guidelines note little concern regarding the diuretics effects of CCB in amounts typically consumed. India’s guidelines discuss the stimulant effects of caffeine present in coffee and tea and advise moderation when consuming these beverages. Excess consumption of coffee was viewed unfavorably for cardiovascular health, while any potential benefits noted for tea consumption were off-set by its caffeine content. The majority of FBDG discouraged caffeinated soda due to its high sugar content. New Zealand further referenced the caffeine content of these beverages, discouraging the intake of these and other caffeine-containing beverages among children and adolescents. With some concern of caffeine’s impact on bone health, older people in New Zealand are advised to consume no more than 300 mg of caffeine per day. Moderate amounts of tea and coffee are also advised for adults; advice that aims to balance the beneficial and potentially adverse properties of these beverages attributable to polyphenol, caffeine, and tannin content. Sri Lanka also noted that tea without milk and sugar has some antioxidants that benefit health.

3.3. Near East

FBDG for Iran advise the general population to reduce soft drink consumption in the context of reducing overall sugar intake. Lebanon’s guidelines advise individuals to avoid consuming coffee, tea, or caffeinated sodas with meals as they inhibit dietary iron absorption. Despite notes concerning caffeine’s diuretic effects, tea and coffee are the preferred beverages (after water) for hydration. Sweetened beverage intake should be limited according to Qatar’s guidelines and in this context, soda and energy drinks are discouraged and careful attention made to the amount of sugar added to coffee.

3.4. Europe

Overall, coffee and carbonated soft drinks are the top CCB sold in Europe. Netherlands consumes the largest volume of coffee per capita than any other country in the Euromonitor database, followed by Finland and Sweden. U.K. and Turkey prefer instant coffee while the rest of Europe prefers fresh-brewed coffee. Decaffeinated coffee accounts for ≈8% of coffee sold in Spain and U.K. and <5% for other parts of Europe. Most carbonated soft drinks sold are of the cola-type. Ireland, Turkey, U.K., and Latvia prefer tea over other CCB. Ireland consumes the more tea per capita than any other country in the Euromonitor database. Black and fruit/herbal teas are the most commonly consumed teas across Europe. Sports and energy drinks and RTD teas are consumed at varying amounts across Europe while RTD coffee consumption is uncommon.

Thirty European countries have published FBDG that consider dietary caffeine sources in some context. Albania, Georgia, Latvia, and Romania are the only set of guidelines noting the iron inhibitory effects of coffee and tea. Latvia and Croatia’s guidelines stated that coffee and tea can reduce calcium absorption. Albania, Latvia, and Portugal were the only FBDG that discouraged the intake of CCB to meet daily water requirements. Most FBDG that specifically mention limiting soda or the broader SSB category do so in the context of limiting sugar intake. Energy drinks are discouraged in Malta guidelines due to their sugar as well as stimulant content. Albania, Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Latvia, and Romania advise pregnant and lactating women to minimize consumption of coffee, tea, or other CCB (≤200–300 mg caffeine/day). Albania, Denmark, Hungary, and Portugal discourage caffeine intake among children. In Denmark and the U.K., adults are advised to limit caffeine intake to 400 mg/day. In Portugal, this limit is set to 300 mg/day. Netherlands’ guidelines recommend the daily consumption of three cups of green or black tea on the basis of research showing it reduces risk of stroke, blood pressure, and possibly diabetes. Similar benefits are stated for coffee consumption, but the Dutch are only advised to replace unfiltered coffee with filtered coffee due to known cholesterol-raising substances present in the former. Romania notes that tea is an important source of bioflavonoids with antioxidant properties that might protect against cardiovascular disease (CVD) but does not provide recommendations for tea per se. In contrast, Latvia discourages the use of coffee or tea in place of water or herbal teas for hydration, in part, for mental health and heart disease prevention.

3.5. Latin America and the Caribbean

Carbonated soda (mostly cola-type) and coffee (mostly fresh-brewed) are the most commonly sold CCB in Latin America and the Caribbean. Argentina and Uruguay are also heavy consumers of yerba mate [22]. Uruguay has the highest per capita consumption of yerba mate in the world [22,23,24]. Other CCB are less commonly consumed across this region compared to other regions of the world.

Twenty-six countries of Latin America and the Caribbean have published FBDG with some mention of dietary caffeine. All countries advised limiting SSB (including soda). Only seven guidelines made specific reference to coffee, tea or caffeine. Yerba mate was not specifically mentioned in any FBDG. Pregnant and lactating mothers in Chile are advised to limit tea and coffee intake while Colombian guidelines advise they avoid energy drinks. In FBDG of Bolivia, Guatemala and Honduras, coffee, tea, and caffeine more generally, were discouraged as substitutes for water because they are diuretics, acidic and/or lead to digestive system problems. In Mexican guidelines, non-sweetened coffee and tea are limited to four cups/day. In Brazil, unsweetened coffee and tea were acceptable substitutes for water.

3.6. North America

In North America, fresh-brewed coffee and carbonated sodas are the most commonly sold CCB. Tea (mostly black) and other CCB are common as well. The USA consumed the most carbonated soda and sports and energy drinks per capita than any other country in the Euromonitor database.

Canadian and American guidelines for CCB were based on evidence compiled and reviewed, in part, for the purpose of setting national guidelines [4,25]. Canada’s FBDG include caffeine upper limits ranging from 45 to 85 mg/day for ages 4 through 12 years, 2.5 mg/kg body weight for adolescents aged 13+, 400 mg/day for adults, and 300 mg/day for pregnant or breastfeeding women, as well as women planning to become pregnant. In the USA, three to five cups of coffee/day (providing up to ≈400 mg/day caffeine) is considered safe for adults, yet individuals who do not consume regular coffee or other caffeinated beverages are not encouraged to begin doing so. Pregnant and breastfeeding women are encouraged to consult their health care providers for advice concerning caffeine intake. Sodas and energy drinks are discouraged but more with regard to their sugar content. Caution is also advised when mixing caffeine and alcohol.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The goal of the current review was to provide the first world summary of guidelines pertaining to dietary caffeine consumption. CCB, while major contributors to caffeine in the diet, also present with other unique nutritional properties. We therefore leveraged existing FBDG since they emphasize food-specific rather than nutrient-specific advice on healthy diets and are developed by interdisciplinary teams of experts with many sources of information reviewed in the process [17]. We begin our discussion with country differences in consumption habits that extend the macro-level consumption data we present in the current report. These are followed by key themes observed across country FBDG including (i) caffeine-intake upper limits to avoid potential health risks, (ii) CCB as replacements for plain water, (iii) CCB as added-sugar sources, and (iv) health benefits of caffeine-containing beverage consumption.

Consumption habits are greatly affected by factors such as geographical origin, culture, lifestyle, social behavior, and economic status. Although regular coffee dominates over decaffeinated coffee across countries, coffee brewing methods differ and these are only partly captured by Euromonitor data used in the current report. While drip filter coffee is the most popular brewing method worldwide, plunger coffee dominates in northern Europe. Turkish coffee is popular in the Middle East, Greece, Turkey, and Eastern Europe, and Espresso and Moka methods are the most common in Italy, Spain, and Portugal [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Tea habits also vary around the world [38,39,40]. For example, Western countries generally drink black tea, made by pouring boiling water over a teabag in a pot or mug and allowing it to steep before consuming (either with or without milk and/or sugar). In India, Pakistan, and some Middle Eastern countries, black tea is largely prepared by boiling the black leaves in a pan for several minutes prior to consumption (often together with water, milk, and sugar). In China and Japan, the drink is normally prepared from green tea by infusing it in hot (but not boiling) water and only the second and subsequent infusions are consumed [40]. Yerba mate is consumed in several South American countries, where it originated, but is less common to other parts of the world [12,22]. Grounded and dried yerba mate leaves and stems are widely consumed in the form of infusions, such as chimarrão and tererê, prepared with hot and cold water, respectively [15]. Differences in brewing methods as well as the type and processing of beans/leaves/stems used are relevant since all affect the sensorial quality and the amount and type of compounds in a “cup” of coffee, tea, or mate [12,15,41]. For example, one needs to consume about three Turkish and five Espresso coffee cups to acquire the same amount of caffeine in one American cup [41]; details to consider when comparing country guidelines. In contrast to the aforementioned natural sources of caffeine, there is little evidence, to our knowledge, in support of a true cultural component to consumption of caffeine-added beverages such as caffeinated soda and energy drinks. A global and concerning pattern is that caffeine-added beverages, which have potential health risks and no benefits, are the primary contributors to caffeine in the diet of children and adolescents [18,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

FBDG respond to a country’s public health and nutrition priorities, sociocultural influences and food production and consumption patterns, among other factors [17]. Historically, the FBDG have focused on undernutrition and included guidelines aimed at consuming a diverse diet to address energy and nutrient gaps [53]. With time, many FBDG have evolved to include guidelines to support healthy lifestyle and specific recommendations to target various age groups [53]. In general, FBDG of some countries such as Sri Lanka, Sierra Leone, and Bangladesh address nutrient inadequacies in the population [54,55,56,57,58,59], while those of other countries, such as India, Thailand, Iran, Lebanon, and Brazil, address the double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition [54,60,61,62,63,64,65]. FBDG of developed and high-income countries, much of Europe and North America, are largely intended for prevention of chronic disease, adverse symptoms, or side effects [25,66,67]. These nutritional priorities partly determined if and how dietary caffeine sources were incorporated into guidelines.

For infants, children and adolescents, CCB consumption is often simply discouraged in FBDG. Canada is an exception and provides quantitative upper limits for caffeine intake according to age. For some countries, such as Nigeria, South Africa, Greece, and Mexico, it is not uncommon to introduce tea to the diet of children <2 years of age [68,69,70,71,72] and thus caffeine guidelines targeting this age group are highly relevant. Only thirteen country FBDG, spanning Asia and the Pacific, Europe, Latin America, and North America, advise pregnant/nursing women to avoid CCB. Eight of these advised specific caffeine limits, which ranged from 200 to 300 mg/day. Small epidemiological studies report that over 60% of women drink caffeine-containing beverages during pregnancy, but total amounts are generally below advised limits [23,73,74,75,76,77]. For adults, Denmark, U.K., Portugal, Canada, and USA advise to limit caffeine intake to 300 or 400 mg/day. FBDG for Australia, Indonesia, New Zealand, Denmark, Hungary, Malta, Colombia, USA, and Canada state specific concerns for energy drinks, generally defined as any drink with >150 mg of caffeine/liter, but often contain other bioactive ingredients and sugar [16,78]. Some guidelines to avoid or limit caffeine intake were based on human or animal studies of pregnancy outcomes, fetal development, and acute caffeine effects (including diuresis, see below). Other guidelines were in place as a safety-precaution since the long-term adverse effects of caffeine are not clear.

Water is essential for life and thus a staple recommendation in all FBDG. Coffee, tea, and yerba mate are naturally non-caloric beverages and currently make important contributions to total fluid intake for many countries [79,80,81,82], but whether they are suitable substitutes for plain water varies by country guidelines and likely reflects the nutritional priorities of the country. For example, FBDG of African countries stress the importance of consuming “enough safe” water as opposed to listing adequate water-substitutes. They were nevertheless concerned about the iron absorption inhibitory effects of tannins present in coffee and tea [83,84,85,86,87], as were the FBDG of several countries of Asia and the Pacific. For some FBDG, whether coffee or tea were adequate water-substitutes was often dependent on whether the diuretic effects of caffeine were considered significant by the country. European and North American countries rarely noted these diuretic effects.

Caffeine-containing soda is a major contributor to sugar intake along with other SSB and implicated in obesity and other metabolic disease around the globe [88]. Guidelines concerning reductions in soda are thus geared towards reducing sugar intake as opposed to monitoring caffeine intake. Coffee and tea become significant sources of added sugar and energy in the diet for countries such as China, Korea, Malaysia, Spain, Italy, Brazil, and Uruguay that prefer to prepare coffee and tea with sugar and cream, or for countries where instant coffee mixes are highly consumed [37,43,44,82,89,90,91,92,93]. These habits are often overlooked and may off-set any benefits that coffee and tea might offer over other beverage types [89,92]. In our review of guidelines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Qatar, Bulgaria, France, Greece, Italy, Malta, Poland, Turkey, Brazil, Mexico, and the USA advised careful attention to the amount of sugar added to coffee and tea.

While there is currently no evidence of health benefits for caffeine-added beverages, recent reviews concerning coffee, and perhaps tea, suggest some benefits with coffee and tea consumption [6,10]. Some FBDGs make reference to these benefits and a few of these also provide specific guidelines. In 2015, the USA dietary guidelines committee reviewed the literature concerning coffee, specifically, as well as total caffeine on health. Potential benefits of three to five cups of coffee/day were discussed in the committee’s Scientific Report [25]. The favorable message, however, could not yet be applied to children or pregnant women or for an equivalent amount of total caffeine (from any source). The Netherlands also point to benefits of green and black tea consumption and recommend three cups/day. Interestingly, Poland discourages consumption of black tea in particular, and Latvia discourages the use of coffee or tea for hydration, in part, for mental health and heart disease prevention. India also provides an in-depth look at coffee, tea, and caffeine. Coffee and caffeine are viewed negatively and potential benefits with tea are off-set by its caffeine content. Mexican guidelines classify beverages from the most (level 1) to the least (level 5) healthy according to their energy content, nutritional value, and risks to health. Coffee and tea (without sugar) are level 3 beverages, limited to four cups/day. No African studies encourage coffee and tea consumption for health. Taken together, inconsistencies concerning health benefits (and risks) of coffee and tea consumption were observed across FBDG and this may be due to the breadth of research on the topic (function of FBDG development date and country-relevancy) or nutritional priorities of the country.

Most guidelines pertaining to dietary caffeine are evidence-based but there are some exceptions. Portugal’s guidelines, for example, state “in tea, the absorption of caffeine is slower than in coffee, which means the stimulating effect is lower but lasts longer.” Albania guidelines advise menopausal women to avoid coffee (among other foods/beverages) because it worsens “warming.” Peer-reviewed literature supporting these statements were often not available. Missing from guidelines was information on known between-person variation in caffeine metabolism, resulting from lifestyle or genetic factors [94,95]. However, despite enthusiasm for “personalized-caffeine recommendations,” further studies are warranted before they can be included in FBDG.

While FBDG help individuals optimize their caffeine habits, many countries regulate caffeine intake at the food manufacturing level by setting limits to the amount of caffeine added to foods [78,96]. Several countries have specifically enacted measures to regulate the labeling, distribution, and sale of energy drinks [2,8,97,98]. For example, Denmark, Turkey, Norway, Uruguay, Sweden, Lithuania, Latvia, and Iceland have banned or restricted sales to children or those <18 years of age, while Hungary and Mexico apply an additional tax to energy drinks [20,21,99,100]. The USA, Canada, and Mexico have further restrictions on the sale of caffeinated alcohol beverages [101,102]. In view of the health risks associated with the widespread consumption of SSB, many national governments have also taken action to reduce consumption of SSB [20,21,103,104]. While these actions are not targeting caffeine, per se, they are targeting a subset of SSB that contain caffeine which include colas and energy drinks. Unfortunately, all policies in place to regulate caffeine intake are challenged by the fact that major dietary sources of caffeine (i.e., coffee and tea) are exempt since they naturally contain caffeine [105,106].

Our data collection strategy for dietary caffeine guidelines was systematic and comprehensive but may be incomplete. We relied on FAO as a starting point which may have missed FBDG of certain countries or may not have been updated with the latest FBDG. Our approach offered several opportunities to address the latter. Our efforts to search and contact secondary resources was often met with limited success. As described elsewhere, the Euromonitor Passport is not a scholarly database and the data have similar limitations to official government trade and economic statistics [107]. Euromonitor data capture sales volume only, an imperfect measure of consumption because it does not capture products distributed through informal food systems or wastage [108]. Moreover, some beverage categories are not exclusively CCB. For example, sports drinks without caffeine are consumed in greater quantities than energy drinks and thus contributions to overall CCB by the “sports drinks and energy drinks” is likely overestimated. However, these data are abundant, less biased than survey data, and they have been consistently reported across countries and time using standardized measures [107]. Despite these limitations, the current review is a starting resource for country-level guidelines and consumption data pertaining to dietary caffeine.

In summary, FBDG provide an unfavorable view of caffeinated-beverages by noting their potential adverse/unknown effects on special populations as well as their diuretic, psycho-stimulating and nutrient inhibitory properties. Few FBDG balanced these messages with recent data supporting potential benefits of specific beverage-types. FBDG can serve to guide a wide range of food and nutrition policies and programs with the unique opportunity to favorably impact diets and the food system [17]. FBDG undergo review and revisions in keeping with changes in nutrition priorities of a country and advancements in nutrition research. We therefore anticipate modifications to guidelines pertaining to caffeine in future releases of FBDG.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/11/1772/s1, Figure S1: Data Collection Strategy for Dietary Caffeine Guidelines; Table S1: Country Specific Guidelines Pertaining to Dietary Caffeine.

Author Contributions

C.M.R. and M.C.C. designed the data collection framework and collected the data. M.C.C. conceptualized the paper and wrote the first draft. All authors revised and approved the final the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging (K01AG053477 to MCC).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for providing supplemental data on dietary caffeine guidelines: Olu Adetokunbo, Lydia K. Browne, Antje Gahl, Neliya Mikushinska, Ul-Aziha bt. Muhammad, Zsuzsanna Nagy-Lőrincz, Rebone Ntsie, Hólmfríður Þorgeirsdóttir, Lāsma Piķele, Jessica Priem, Silke Restemeyer, Laura Rossi, Guro Smedshaug, Ilze Vamža, Joka van Dusseldorp-Dijkstra, Sara Upplysningen, Dagny Løvoll Warming, and Yurun Wu; as well as the following individuals for their assistance in translating FBDG: H.M. Abdulazeem, Corneliu C Antonescu, Eric Cifaldi, Marina Dujmović, Diane Gal, Janet Lyu, Pawel Rykowski, Morten Svan, and Noni Tobing. Finally, we thank FAO staff (Melissa Vargas) and Northwestern University’s Galter Health Sciences Library research staff (Eileen Wafford, Annie Wescott) for support and guidance on data collection, and Alan Kuang for assistance on data presentation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fredholm, B.B.; Battig, K.; Holmen, J.; Nehlig, A.; Zvartau, E.E. Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol. Rev. 1999, 51, 83–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zucconi, S.; Volpato, C.; Adinolfi, F.; Gandini, E.; Gentile, E.; Loi, A.; Fioriti, L. Gathering consumption data on specific consumer groups of energy drinks. EFSA Support. Publ. 2013, 10, 394E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikoff, D.; Welsh, B.T.; Henderson, R.; Brorby, G.P.; Britt, J.; Myers, E.; Goldberger, J.; Lieberman, H.R.; O’Brien, C.; Peck, J. Systematic review of the potential adverse effects of caffeine consumption in healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents, and children. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 109, 585–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawrot, P.; Jordan, S.; Eastwood, J.; Rostein, J.; Hugenholtz, A.; Feeley, M. Effects of caffeine on human health. Food Addit. Contam. 2003, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies. Scientific opinion on the safety of caffeine. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4102. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, R.; Kennedy, O.J.; Roderick, P.; Fallowfield, J.A.; Hayes, P.C.; Parkes, J. Coffee consumption and health: Umbrella review of meta-analyses of multiple health outcomes. BMJ 2017, 359, j5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Babu, K.; Deuster, P.A.; Shearer, J. Energy drinks: A contemporary issues paper. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breda, J.J.; Whiting, S.H.; Encarnação, R.; Norberg, S.; Jones, R.; Reinap, M.; Jewell, J. Energy drink consumption in Europe: A review of the risks, adverse health effects, and policy options to respond. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, Q.V. Epidemiological evidence linking tea consumption to human health: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, K.; Iqbal, H.; Malik, U.; Bilal, U.; Mushtaq, S. Tea and its consumption: Benefits and risks. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 939–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruanpeng, D.; Thongprayoon, C.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Harindhanavudhi, T. Sugar and artificially sweetened beverages linked to obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM Int. J. Med. 2017, 110, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, C.I.; de Mejia, E.G. Yerba mate tea (ilex paraguariensis): A comprehensive review on chemistry, health implications, and technological considerations. J. Food Sci. 2007, 72, R138–R151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiller, M.A. The chemical components of coffee. In Caffeine; Spiller, G.A., Ed.; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1998; pp. 97–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, D.C.; Hockenberry, J.; Teplansky, R.; Hartman, T.J. Assessing dietary exposure to caffeine from beverages in the US population using brand-specific versus category-specific caffeine values. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 80, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silveira, T.F.F.; Meinhart, A.D.; de Souza, T.C.L.; Cunha, E.C.E.; de Moraes, M.R.; Godoy, H.T. Chlorogenic acids and flavonoid extraction during the preparation of yerba mate based beverages. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLellan, T.M.; Lieberman, H.R. Do energy drinks contain active components other than caffeine? Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 730–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Available online: http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/background/en/ (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Mitchell, D.C.; Knight, C.A.; Hockenberry, J.; Teplansky, R.; Hartman, T.J. Beverage caffeine intakes in the US. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 63, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Country Classification 2017. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Hawkes, C.; Jewell, J.; Allen, K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases: The nourishing framework. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WCRF International Nourishing Framework. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/int/policy/nourishing-database (accessed on 1 October 2018).

- Euromonitor Euromonitor International. Available online: https://www.euromonitor.com/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Matijasevich, A.; Barros, F.C.; Santos, I.S.; Yemini, A. Maternal caffeine consumption and fetal death: A case–control study in Uruguay. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2006, 20, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronco, A.L.; Stefani, E.; Mendoza, B.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Vazquez, A.; Abbona, E. Mate intake and risk of breast cancer in Uruguay: A case-control study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 17, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millen, B.; Lichtenstein, A.; Abrams, S. Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Petracco, M. Technology 4: Beverage preparation: Brewing trends for the new millennium. In COFFEE Recent Developments; Blackwell Science Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotakos, D.B.; Lionis, C.; Zeimbekis, A.; Makri, K.; Bountziouka, V.; Economou, M.; Vlachou, I.; Micheli, M.; Tsakountakis, N.; Metallinos, G.; et al. Long-term, moderate coffee consumption is associated with lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus among elderly non-tea drinkers from the Mediterranean islands (Medis study). Rev. Diabet. Stud. 2007, 4, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Garcia, E.; Guallar-Castillon, P.; Leon-Munoz, L.; Graciani, A.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Coffee consumption and health-related quality of life. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, J.M. Methylxanthine content in commonly consumed foods in Spain and determination of its intake during consumption. Foods 2017, 6, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amicis, A.; Scaccini, C.; Tomassi, G.; Anaclerio, M.; Stornelli, R.; Bernini, A. Italian style brewed coffee: Effect on serum cholesterol in young men. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1996, 25, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraroni, M.; Tavani, A.; Decarli, A.; Franceschi, S.; Parpinel, M.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Reproducibility and validity of coffee and tea consumption in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leurs, L.J.; Schouten, L.J.; Goldbohm, R.A.; van den Brandt, P.A. Total fluid and specific beverage intake and mortality due to IHD and stroke in The Netherlands Cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilyuk, O.; Braaten, T.; Skeie, G.; Weiderpass, E.; Dumeaux, V.; Lund, E. High coffee consumption and different brewing methods in relation to postmenopausal endometrial cancer risk in the Norwegian women and cancer study: A population-based prospective study. BMC Women’s Health 2014, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lof, M.; Sandin, S.; Yin, L.; Adami, H.O.; Weiderpass, E. Prospective study of coffee consumption and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality in Swedish women. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, A.G.; da Costa, T.H. Usual coffee intake in Brazil: Results from the national dietary survey 2008–9. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1615–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, A.M.; Steluti, J.; Goulart, A.C.; Bensenor, I.M.; Lotufo, P.A.; Marchioni, D.M. Coffee consumption and coronary artery calcium score: Cross-sectional results of Elsa-Brasil (Brazilian longitudinal study of adult health). J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e007155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, I.N.; Goldman, J.; Rhodes, D.G.; Hoy, M.K.; Moura Souza, A.; Chester, D.N.; Martin, C.L.; Sebastian, R.S.; Ahuja, J.K.; Sichieri, R.; et al. Difference in adult food group intake by sex and age groups comparing Brazil and United States nationwide surveys. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beresniak, A.; Duru, G.; Berger, G.; Bremond-Gignac, D. Relationships between black tea consumption and key health indicators in the world: An ecological study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigg, D. The worlds of tea and coffee: Patterns of consumption. GeoJournal 2002, 57, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, C.; Birch, M.R.; Dacombe, C.; Humphrey, P.G.; Martin, P.T. Factors affecting the caffeine and polyphenol contents of black and green tea infusions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5340–5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derossi, A.; Ricci, I.; Caporizzi, R.; Fiore, A.; Severini, C. How grinding level and brewing method (Espresso, American, Turkish) could affect the antioxidant activity and bioactive compounds in a coffee cup. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 3198–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, M.M.; Myhre, J.B.; Andersen, L.F. Beverage consumption patterns among Norwegian adults. Nutrients 2016, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.A.; Souza, A.M.; Duffey, K.J.; Sichieri, R.; Popkin, B.M. Beverage consumption in Brazil: Results from the first national dietary survey. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landais, E.; Moskal, A.; Mullee, A.; Nicolas, G.; Gunter, M.J.; Huybrechts, I.; Overvad, K.; Roswall, N.; Affret, A.; Fagherazzi, G. Coffee and tea consumption and the contribution of their added ingredients to total energy and nutrient intakes in 10 European countries: Benchmark data from the late 1990s. Nutrients 2018, 10, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Kawado, M.; Aoyama, N.; Hashimoto, S.; Suzuki, K.; Wakai, K.; Suzuki, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Tamakoshi, A. Coffee consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: The Japan collaborative cohort study. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 24, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesirow, M.S.; Welsh, J.A. Changing beverage consumption patterns have resulted in fewer liquid calories in the diets of US children: National health and nutrition examination survey 2001–2010. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 559–566.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, M.L.; Forshee, R.A.; Anderson, P.A. Beverage consumption in the US population. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 1992–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loftfield, E.; Freedman, N.D.; Dodd, K.W.; Vogtmann, E.; Xiao, Q.; Sinha, R.; Graubard, B.I. Coffee drinking is widespread in the United States, but usual intake varies by key demographic and lifestyle factors-3. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak, M.E.; Sternberg, M.R.; Pao, C.-I.; Ahluwalia, N.; Pfeiffer, C.M. Urine excretion of caffeine and select caffeine metabolites is common in the US population and associated with caffeine intake-4. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nergiz-Unal, R.; Akal Yildiz, E.; Samur, G.; Besler, H.T.; Rakicioglu, N. Trends in fluid consumption and beverage choices among adults reveal preferences for Ayran and black tea in central Turkey. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 74, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena, A.; Lino, C.; Silveira, M.I. Survey of caffeine levels in retail beverages in Portugal. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, A.; Ferreira, C.; Sousa, D.; Costa, S. Consumption patterns of energy drinks in Portuguese adolescents from a city in northern Portugal. Acta Med. Port. 2018, 31, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, J.; Andrade, J. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines: An Overview. Washington: Integrating Gender and Nutrition within Agricultural Extension Services and USAID, 2016. Available online: https://www.agrilinks.org/sites/default/files/resource/files/ING%20TN%20(2016_10%20)%20Food%20Based%20Dietary%20Guideline%20-%20Overview%20(Andrade,%20Andrade).pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- World Health Organization. Regional Consultation on Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Countries in the South-East Asia Region, 6–9 December 2010, New Delhi, India; World Health Organization: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Institue of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders. Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh; Bangladesh Institue of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nutrition Division Federaal Ministry of Health; World Health Organization. Food-Based Dietary Guideline for Nigeria; Federal Ministry of Health: Abuja, Nigeria, 2006.

- Vorster, H.H.; Badham, J.; Venter, C. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S5–S12. [Google Scholar]

- German Ministry of Food Agriculture and Consumer Protection; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Sierra Leone Food Based Dietary Guideline for Healthy Eating. 2016. Available online: https://afro.who.int/publications/sierra-leone-food-based-dietary-guidelines-healthy-eating-2016 (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Harika, R.; Faber, M.; Samuel, F.; Kimiywe, J.; Mulugeta, A.; Eilander, A. Micronutrient status and dietary intake of iron, vitamin a, iodine, folate and zinc in women of reproductive age and pregnant women in Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa: A systematic review of data from 2005 to 2015. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Indians; National Institute of Nutrition: Hyderabad, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goshtaei, M.; Ravaghi, H.; Sari, A.A.; Abdollahi, Z. Nutrition policy process challenges in Iran. Electron. Phys. 2016, 8, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwalla, N.; Nasreddine, L.; Farhat Jarrar, S. The Food-Based Dietary Guideline Manual for Promoting Healthy Eating in the Lebanese Adult Population. The Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut, Lebanese National Council for Scientific Research (CNRS), Ministry of Public Health, 2013. Available online: www.aub.edu.lb/fafs/nfsc/Documents/LR-e-FBDG-EN-III.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2015).

- Fonseca, V.M. Aspects of the Brazilian nutritional situation. Cienc. Saude Colet. 2014, 19, 1328–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population; Ministry of Health of Brazil: Brasília, Brazil, 2015.

- Vorster, H.H.; Kruger, A.; Margetts, B.M. The nutrition transition in Africa: Can it be steered into a more positive direction? Nutrients 2011, 3, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines Summary; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- Kromhout, D.; Spaaij, C.; De Goede, J.; Weggemans, R. The 2015 Dutch food-based dietary guidelines. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwankwo, B.O.; Brieger, W.R. Exclusive breastfeeding is undermined by use of other liquids in rural Southwestern Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2002, 48, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tympa-Psirropoulou, E.; Vagenas, C.; Psirropoulos, D.; Dafni, O.; Matala, A.; Skopouli, F. Nutritional risk factors for iron-deficiency Anaemia in children 12–24 months old in the area of Thessalia in Greece. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urkin, J.; Adam, D.; Weitzman, D.; Gazala, E.; Chamni, S.; Kapelushnik, J. Indices of iron deficiency and Anaemia in Bedouin and Jewish toddlers in southern Israel. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 857–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Castell, D.; González de Cosío, T.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Escobar-Zaragoza, L. Early consumption of liquids different to breast milk in Mexican infants under 1 year: Results of the probabilistic national health and nutrition survey 2012. Nutr. Hosp. 2016, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mennella, J.A.; Turnbull, B.; Ziegler, P.J.; Martinez, H. Infant feeding practices and early flavor experiences in Mexican infants: An intra-cultural study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachidi, S.; Awada, S.; Al-Hajje, A.; Bawab, W.; Zein, S.; Saleh, N.; Salameh, P. Risky substance exposure during pregnancy: A pilot study from Lebanese mothers. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2013, 5, 123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bailey, H.D.; Lacour, B.; Guerrini-Rousseau, L.; Bertozzi, A.-I.; Leblond, P.; Faure-Conter, C.; Pellier, I.; Freycon, C.; Doz, F.; Puget, S. Parental smoking, maternal alcohol, coffee and tea consumption and the risk of childhood brain tumours: The ESTELLE and ESCALE studies (SFCE, France). Cancer Causes Control 2017, 28, 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Mota Santana, J.; Alves de Oliveira Queiroz, V.; Monteiro Brito, S.; Barbosa Dos Santos, D.; Marlucia Oliveira Assis, A. Food consumption patterns during pregnancy: A longitudinal study in a region of the north east of Brazil. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tollånes, M.C.; Strandberg-Larsen, K.; Eichelberger, K.Y.; Moster, D.; Lie, R.T.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Meltzer, H.M.; Stoltenberg, C.; Wilcox, A.J. Intake of caffeinated soft drinks before and during pregnancy, but not total caffeine intake, is associated with increased cerebral palsy risk in the Norwegian mother and child cohort study–3. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, A.; Hutchinson, D.; Wilson, J.; McCormack, C.; Bruno, R.; Olsson, C.A.; Allsop, S.; Elliott, E.; Burns, L.; Mattick, R.P. Adherence to the caffeine intake guideline during pregnancy and birth outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Nutrients 2018, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, L.S.; Mihalov, J.J.; Carlson, S.J.; Mattia, A. Regulatory status of caffeine in the United States. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guelinckx, I.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C.; Moreno, L.A.; Kavouras, S.A.; Gandy, J.; Martinez, H.; Bardosono, S.; Abdollahi, M.; Nasseri, E.; Jarosz, A. Intake of water and different beverages in adults across 13 countries. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özen, A.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Pons, A.; Tur, J. Fluid intake from beverages across age groups: A systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 417–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platania, A.; Castiglione, D.; Sinatra, D.; Urso, M.D.; Marranzano, M. Fluid intake and beverage consumption description and their association with dietary vitamins and antioxidant compounds in Italian adults from the Mediterranean healthy eating, aging and lifestyles (meal) study. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Stefani, E.; Boffetta, P.; Ronco, A.L.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Acosta, G.; Mendilaharsu, M. Dietary patterns and risk of bladder cancer: A factor analysis in Uruguay. Cancer Causes Control 2008, 19, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad Fuzi, S.F.; Koller, D.; Bruggraber, S.; Pereira, D.I.; Dainty, J.R.; Mushtaq, S. A 1-h time interval between a meal containing iron and consumption of tea attenuates the inhibitory effects on iron absorption: A controlled trial in a cohort of healthy UK women using a stable iron isotope. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurrell, R.F.; Reddy, M.; Cook, J.D. Inhibition of non-haem iron absorption in man by polyphenolic-containing beverages. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thankachan, P.; Walczyk, T.; Muthayya, S.; Kurpad, A.V.; Hurrell, R.F. Iron absorption in young Indian women: The interaction of iron status with the influence of tea and ascorbic acid. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, M.; Poulter, J. Impact of tea drinking on iron status in the UK: A review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2004, 17, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savolainen, H. Tannin content of tea and coffee. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1992, 12, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, F.B.; Malik, V.S. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes: Epidemiologic evidence. Physiol. Behav. 2010, 100, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Coffee Organization. Coffee in China; International Coffee Organization: Milan, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amarra, M.S.V.; Khor, G.L.; Chan, P. Intake of added sugar in Malaysia: A review. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 25, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saw, W.; Shanita, S.N.; Zahara, B.; Tuti, N.; Poh, B.K. Dietary intake assessment in adults and its association with weight status and dental caries. Pak. J. Nutr. 2012, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar]

- Je, Y.; Jeong, S.; Park, T. Coffee consumption patterns in Korean adults: The Korean national health and nutrition examination survey (2001–2011). Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guallar-Castillon, P.; Munoz-Pareja, M.; Aguilera, M.T.; Leon-Munoz, L.M.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F. Food sources of sodium, saturated fat and added sugar in the Spanish hypertensive and diabetic population. Atherosclerosis 2013, 229, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, A.; Dahl, M.L. Variation in cyp1a2 activity and its clinical implications: Influence of environmental factors and genetic polymorphisms. Pharmacogenomics 2008, 9, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelis, M.C.; Kacprowski, T.; Menni, C.; Gustafsson, S.; Pivin, E.; Adamski, J.; Artati, A.; Eap, C.B.; Ehret, G.; Friedrich, N. Genome-wide association study of caffeine metabolites provides new insights to caffeine metabolism and dietary caffeine-consumption behavior. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 5472–5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code Standard 2.6.4 Formulated Caffeinated Beverages; Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Kingston, Australia, 2014.

- Thomson, B.; Schiess, S. Risk profile: Caffeine in Energy Drinks and Energy Shots. Institute of Environmental Science & Research Limited, April 2010. Available online: https://www.foodsafety.govt.nz/elibrary/industry/Risk_Profile_Caffeine-Science_Research.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Higgins, J.P.; Tuttle, T.D.; Higgins, C.L. Energy beverages: Content and safety. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hungarian National Institute for Health Development (NIHD). Impact Assessment of the Public Health Product Tax; NIHD: Budapest, Hungary, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Food News. Lithuania Ban on Energy Drink Sales to under 18s Comes in with Broader Restrictions and Warnings. Available online: http://www.ausfoodnews.com.au/2014/11/05/lithuania-ban-on-energy-drink-sales-to-under-18s-comes-in-with-broader-restrictions-and-warnings.html (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Food and Drug Administration US Department of Health and Human Services. Update on Caffeinated Alcoholic Beverages; US Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2010.

- Attwood, A.S. Caffeinated alcohol beverages: A public health concern. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012, 47, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M.; Hawkes, C. Sweetening of the global diet, particularly beverages: Patterns, trends, and policy responses. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, J.C.; Smith-Taillie, L.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B. Designing a food tax to impact food-related non-communicable diseases: The case of Chile. Food Policy 2017, 71, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachenmeier, D.W.; Winkler, G. Caffeine content labeling: A prudent public health policy? J. Caffeine Res. 2013, 3, 154–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, J.; Barnhill, A. Caffeine content labeling: A missed opportunity for promoting personal and public health. J. Caffeine Res. 2013, 3, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuckler, D.; McKee, M.; Ebrahim, S.; Basu, S. Manufacturing epidemics: The role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerleau, J.; Lock, K.; McKee, M. Discrepancies between ecological and individual data on fruit and vegetable consumption in fifteen countries. Br. J. Nutr. 2003, 89, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).