Abstract

Malaria remains one of the devastating illnesses, and drug-resistant malaria has incurred enormous societal costs. A few host kinases are vital for the liver stage malaria and might be promising drug targets against drug-resistant malaria. STK35L1 is one of the host kinases that is highly upregulated during the liver stage of malaria, and the knockdown of STK35L1 significantly suppresses Plasmodium sporozoite infection. In this study, we retrieved the promoter region of STK35L1 based on 5′ complete transcripts, transcription start sites, and cap analysis of gene expression tags. Furthermore, we identify transcriptionally active regions by analyzing CpG islands, histone acetylation (H3K27ac), and histone methylation (H3K4me3). It suggests that the identified promoter region is active and has cis-regulatory elements and enhancer regions. We identified various putative transcription factors (TFs) from the various high-throughput ChIP data that might bind to the promoter region of STK35L1. These TFs were differentially regulated during the infection of Plasmodium sporozoites in HepG2 cells. Our molecular modeling study suggests that, except for SMAD3, the identified TFs may be directly bound to the promoter. Together, the data suggest that these TFs may play a role in sporozoite infection and in regulating STK35L1 expression during the liver stage of malaria.

1. Introduction

Malaria, caused by the Plasmodium genus, remains one of the devastating illnesses, causing 263 million infections and 597,000 deaths globally in 2023 [1]. The development of resistance to anti-malarial drugs has incurred enormous societal costs, hindering the development of effective prophylactic agents. Currently, only a few effective drugs against malaria are available [2]. Host and parasite protein kinases are crucial in the invasion and survival of parasites during malaria infection and might be promising drug targets against drug-resistant malaria [3]. Few studies have identified various host kinases that may be crucial for the liver stage of the parasite’s infection [4,5,6,7]. A kinome-wide RNAi screening revealed that STK35L1 was among the top five hits that were responsible for the infection of the Huh7 hepatoma cell line by Plasmodium berghei (P. berghei) [5]. Later, we demonstrated that STK35L1 was highly upregulated during the infection of P. berghei sporozoites in both HepG2 cells and mice, and the knockdown of STK35L1 significantly suppressed sporozoite infection [7].

STK35L1 is a member of the NKF4 family of Ser/Thr kinases, localized in the nucleus and nucleolus. We reported that STK35L1 interacts with nuclear actin, regulates the expression of crucial cell cycle and DNA repair genes, and is essential for endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis [8,9]. STK35L1 is also associated with development, as STK35L1 knockout mice display abnormalities in testis, ovary, and eye development [10]. STK35L1 has been established as a critical regulator in diverse cellular processes, including the cell cycle, cell migration, apoptosis, and the DNA damage response, as well as processes regulated through these pathways, such as spermatogenesis. STK35L1 has been shown to alter several DNA repair genes (GADD45A, DDX11, and RAD51) [8], and the knockdown of STK35L1 in RPE1 cells led to G2/M phase cell cycle arrest upon cisplatin-induced DNA damage [11]. Constitutive overexpression of STK35L1 enhances caspase-independent cell death under oxidative stress conditions, during which there occurs a collapse of the Ran gradient, leading to the accumulation of importin α in the nucleus, and a subsequent block of nuclear protein import occurs [12]. Interestingly, in the osteosarcoma cell line U2OS and colorectal cancer cell lines SW620 and HCT116, the knockdown of STK35L1 led to enhanced apoptosis via the caspase-dependent pathway [13,14]. In colorectal cancer, elevated STK35L1 expression promotes cell survival and tumor growth [14]. The expression of STK35L1 has been recently linked to various stages of AML, supporting cell proliferation, amino acid biosynthesis, and transport in AML [15].

Previously, a report showed that P. yoelii infection increased the activation of STAT1 and STAT3 during the early infection [16]. Another report showed that STAT3 was activated via phosphorylation during the infection of P. berghei in the cerebral malaria mouse model, suggesting a crucial role in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria [17]. We also reported the upregulation of STAT3 in HepG2 cells after infection with P. berghei sporozoites, and its activation is required for the upregulation of STK35L1 [7]. STAT3 is a member of the STAT family of transcription factors, which comprises a total of seven members [18]. STAT3 is present in its latent form in the cytoplasm, where it is activated by various signals that induce phosphorylation through JAK, leading to its homodimerization and subsequent transport into the nucleus [19]. STAT3 is the only transcription factor identified so far that regulates the expression of STK35L1 [7,13]. A limited number of studies have been conducted to date to understand the transcriptional regulation of the human host during the liver stage of malaria. A study reported the altered expression of FOXM1, SOX4, E2F8, E2F7, SMAD4, and MYBL2 transcription factors upon infection with P. falciparum sporozoites in HepG2-A16 [20]. Another study that undertook the expression profiling of P. berghei ANKA-infected and non-infected Hepa1-6 cells reported the downregulation of STAT5A and FOXA2 transcription factors [21].

In this study, we characterized the STK35L1 promoter. By utilizing ChIP experimental data from ENCODE and published resources, we identified various transcription factors (TFs) that may interact with the STK35L1 promoter. To validate the direct binding of the TFs, AlphaFold models were generated, and interacting promoter DNA sequences for TFs were identified. We asked whether the identified TFs are differentially expressed during the sporozoite infection. Indeed, we report for the first time that all identified TFs, except E2F4, were differentially regulated during the infection of P. berghei sporozoites in HepG2 cells. These findings suggest that these TFs may play a pivotal role during the liver stage of malaria.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Characterization of the Human STK35 Promoter

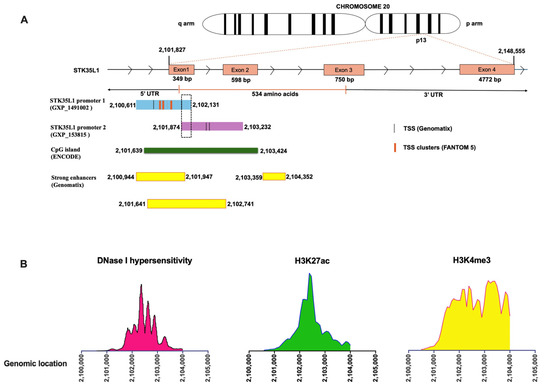

To identify the functional promoter regions of the human STK35 gene, we analyzed the 5′ UTR region of the STK35 genomic locus using the Genomatix software suite v3.10 with the Eldorado/Gene2Promoter tool. Two promoter regions named promoter 1 and promoter 2 (Supplementary File S1) were selected based on experimentally verified 5′ complete transcripts, transcription start sites (TSS), and cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) tags. The promoter 1 (GXP_1491002) was a 1521 bp long region, starting from the genomic location 2100611 to 2102131, and consisted of 3 TSS (genomic positions at 2101612, 2101883, and 2102032) (Figure 1A). The promoter 2 (GXP_153815) was a 1359 bp long region starting from the genomic location 2101874 to 2103232, with a small part overlapping with the promoter 1 and containing 2 TSS (genomic position at 2102892 and 2102909) (Figure 1A). We also analyzed the CAGE data from the FANTOM 5 consortium [22], which identified three TSS clusters in the same region (2101804 to 2102038) (Table S1). These data suggest the promoter regions are transcriptionally active.

Figure 1.

Cis-regulatory elements of STK35L1 Promoter regions. (A) The cartoon illustrates the genomic locations of identified STK35L1 promoters, featuring 5 TSS regions, CpG islands (green), and strong enhancers (yellow boxes). The dashed box shows the overlapping areas of promoter 1 and promoter 2. (B) The line plot displays the aggregated DNase I-seq signals (DNase I hypersensitivity) and ChIP-seq (H3K27ac, H3K4me3) in the genomic locus of promoter regions.

Further, we checked whether the chromatin in the promoter region is accessible to the transcription machinery. We analyzed the DNase-seq and ChIP-seq data from the ENCODE consortium [23], which comprises data from various human primary cells and cell lines. We found that the promoter regions exhibited DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs), indicating that these regions are histone-free and transcriptionally active (Figure 1B, left panel). Furthermore, to identify cis-regulatory transcriptionally active regions, we analyzed CpG islands (CGIs), histone acetylation mark (H3K27ac), and histone methylation mark (H3K4me3) using ENCODE data. Indeed, the identified promoter regions contain CpG islands (from 2101639 to 2103424), as well as H3K27ac and H3K4me3 (Figure 1A, middle and right panels). These data suggest that the identified promoters of STK35L1 are active and have cis-regulatory elements (CRE) and enhancer regions.

2.2. Identification of Putative Transcription Factors Binding to the STK35L1 Promoter Region

We further analyzed the CRE in the identified promoter regions to retrieve putative TFs that might bind to the STK35L1 promoter and regulate its expression in HepG2 cells. We utilized the MatInspector tool from Genomatix [24] and the Enrichr web server [25] to analyze data from various high-throughput datasets (ChEA 2022 [26] and ENCODE [23]) (Table 1 and Table S2). Various TFs were identified from these datasets that we further compared, and a total of 16 TFs (Table 1) were selected that were commonly identified by all the datasets in the CRE and promoter region of STK35L1. In our previous study, we identified STAT3 as the only member of the STAT family among STAT1, STAT2, and STAT4 that was upregulated during the sporozoite infection in HepG2 cells and regulated the STK35L1 expression [7]; therefore, in this study, we undertook the analysis of the other members of the STAT family of transcription factors.

Table 1.

List of the selected transcription factors found in the promoter region of STK35L1 with their NCBI gene and protein IDs.

2.3. Identification of Transcription Factors Binding Regions in the Promoter of STK35L1

As the putative TFs identified from the ChIP experimental data from ENCODE and published resources, there is a higher chance that they interact directly or indirectly with the promoter of STK35L1. To answer whether the identified TFs bind directly to the promoter of STK35L1, we analyzed the promoter using the Genomatix/MatInspector [24]. The binding motifs of STAT3, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6, E2F1, E2F3, E2F4, and E2F6 were identified with a matrix similarity of >0.75 and are shown in Table S3. These data suggest that the identified putative TFs may bind directly to the promoter of STK35L1.

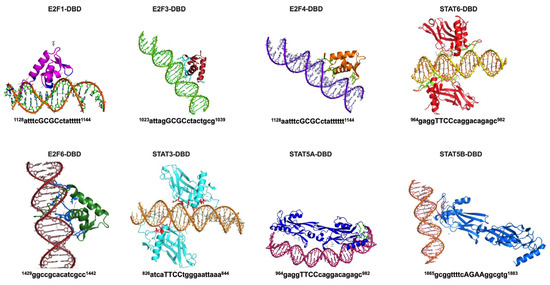

To validate the direct binding of TFs, we modeled each TF-promoter DNA interaction in AlphaFold 3.0 (AF3) [27] (Figure 2). AF3 can model biomolecular interactions, such as protein–protein, protein–DNA, protein–RNA, and protein–ligand interactions with high accuracy. The interaction of residues present in the DNA-binding domain of TF and DNA was identified by AF3 for STAT3, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6, E2F1, E2F3, E2F4, and E2F6. Notably, the promoter regions were found to be similar to the DNA motifs identified by Genomatix/MatInspector (Figure 2, Table S3), suggesting that these sites may be putative binding sites for these transcription factors in the STK35L1 promoter. The DNA binding motif identified by AF3 for E2F6 was 10 bp upstream of the motif recognized by the Genomatix/MatInspector (Figure 2, Table S3). The DNA binding regions of other transcription factors E2F2, FOXA1, FOXA2, FOXG1, TCF3, MYBL2, and SOX2 (Figure S1) were uniquely identified by the AlphaFold models. No interaction of SMAD3 was observed with the STK35L1 promoter, suggesting that it may interact with the STK35L1 promoter indirectly.

Figure 2.

AlphaFold model of TF-promoter complex. The TF-DNA complexes were generated using the AF3 server. The DNA-binding domain (DBD) of each TF interacts with the promoter region, as shown here. The bases interacting with DBD and their position in the promoter region are shown below each model.

2.4. Expression of Identified Transcription Factors in HepG2 Cells

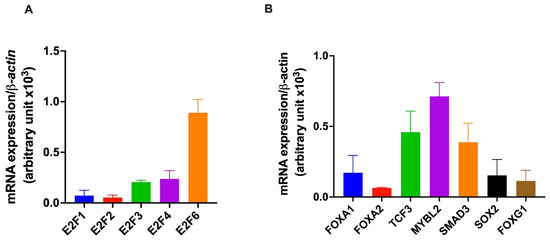

The basal expression of the selected TFs (Table 1) was measured via qPCR in HepG2 cells under normal physiological conditions. Among the selected E2F family members, E2F6 was highly expressed, with the expression of other members in the order of E2F4≈, E2F3 >> E2F1 > E2F2 (Figure 3A). Furthermore, we found that the selected members of the FOX family (FOXA1, FOXA2, and FOXG1) were expressed in the HepG2 cells. The expression of FOXA1 and FOXG1 was ~2-fold higher than that of FOXA2.

Figure 3.

Basal expression of transcription factors in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were grown under standard cell culture conditions, and total RNA was isolated from the cells at various passages. The expression of genes was quantified using quantitative PCR (qPCR). The bar graph shows the basal expression of E2F family members (A) and the other selected transcription factors (TCF3, MYBL2, SMAD3, FOXA1, FOXA2, FOXG1, and SOX2 (B). The housekeeping gene β-actin was used for data normalization.

The expression of other TFs (TCF3, MYBL2, SMAD3, and SOX2) was also observed in HepG2 cells (Figure 3B). MYBL2 was abundant among all, and the level of expression was comparable to E2F6. The expression of TCF3 and SMAD3 was ~1.5 fold and ~1.8 fold lower than the expression of MYBL2, respectively (Figure 3B). The expression of SOX2 was ~4.7-fold lower than MYBL2. These data suggest an active role of all the TFs in the normal physiology of HepG2 cells and may play a role in the infection of Plasmodium sporozoites in HepG2 cells.

2.5. STK35L1-Linked TFs Were Differentially Expressed During Plasmodium Sporozoites Infection in HepG2 Cells

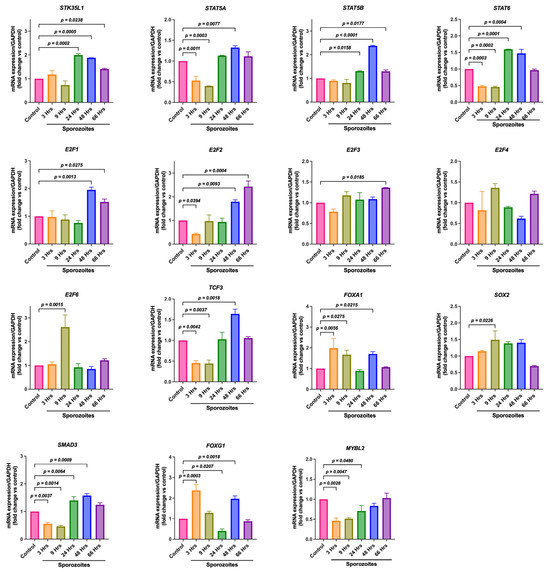

We asked whether the selected TFs are differentially regulated during the infection of Plasmodium sporozoites in HepG2 cells. The expression of these TFs in non-infected (control) and infected cells was measured by qPCR at different time points (3 h, 9 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 66 h) after infection. Among all the transcription factors studied, it was found that STAT5A, STAT6, E2F2, TCF3, and SMAD3 were significantly downregulated during early sporozoite infection (at 3 h and 9 h). However, these TFs were significantly upregulated at 48 h of sporozoite infection (Figure 4). SOX2 and E2F6 were found to be substantially upregulated at 9 h of sporozoite infection (Figure 4). Interestingly, the FOX family members, FOXA1 and FOXG1, were significantly upregulated during the initial sporozoite infection (3 h) and then downregulated at 24 h but recovered by 48 h of sporozoite infection (Figure 4). E2F1 and STAT5B were found to be upregulated at 48 h of sporozoite infection (Figure 4). Interestingly, MYBL2 showed significant downregulation during the sporozoite infection, suggesting its negative correlation with the infection. No significant changes were observed in the expression of E2F3 until 48 h after sporozoite infection; however, it was significantly upregulated at 66 h (Figure 4). No significant changes were observed in the expression of E2F4 at any time point of sporozoite infection (Figure 4). Collectively, these data suggest that, except for E2F4, all the TFs (STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6, E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, E2F6, TCF3, FOXA1, FOXG1, SMAD3, and SOX2) were differentially regulated during the sporozoite infection and might play a crucial role during the liver stage of malaria.

Figure 4.

Differential expression of STK35L1 promoter-linked TFs during Plasmodium infection in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were infected with P. berghei ANKA sporozoites, and the expression of STK35L1, E2F family members, and other selected transcription factors FOXA1, FOXA2, FOXG1, MYBL2, SMAD3, STAT5A, STAT5B, STAT6, SOX2, and TCF3 was measured using qPCR at different time points and is shown here. Data were normalized with the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

2.6. Upregulation of the Selected TFs Is Independent of STAT3 Activation During the Plasmodium Infection in HepG2 Cells

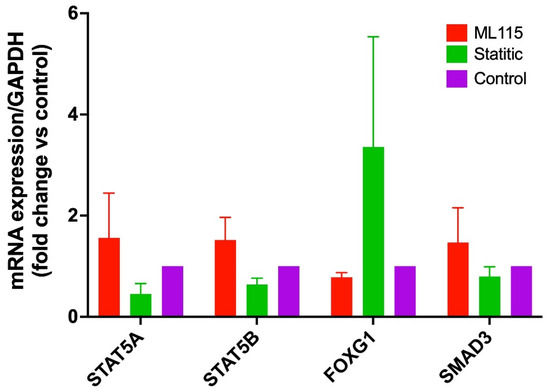

Previously, we have shown that STAT3 is significantly upregulated during the sporozoite infection, and it regulates the expression of STK35L1 during the liver stage of malaria [7]. We asked whether the differential expression of identified TFs during Plasmodium sporozoites infection in HepG2 cells is regulated via activation of STAT3. To examine the role of STAT3 activation, we used specific STAT3 activator ML115 [28] and STAT3 inhibitor Stattic [29]. We observed that there is no significant effect of STAT3 activation on all the TFs examined, indicating STAT3-independent regulation in HepG2 cells (Figure 5), which suggests that they may regulate the expression of STK35L1 through an alternative regulatory signaling pathway.

Figure 5.

Expression of differentially regulated transcription factors after sporozoite infection under STAT3 activator and inhibitor treatment. HepG2 cells were grown in standard cell culture conditions and were treated with STAT3 inhibitor (Stattic, 10 µM) and STAT3 activator (ML115, 4 µM) for 6 hrs. The expression of TFs was quantified by qPCR. The bar graph shows no significant effect of STAT3 activation and inhibition on the expression of these TFs. The housekeeping gene GAPDH was used for data normalization.

3. Discussion

Drug-resistant malaria contributes to the elevated rate of morbidity and mortality, demanding urgent efforts to develop new drug inhibitors and approaches to overcome this problem. STK35L1 has been established as a host kinase crucial for the parasite’s infection during the liver stage of malaria [7]. In this study, we identified and characterized the promoter of STK35L1. We identified various TFs that might bind to the promoter region of STK35L1. These TFs were differentially regulated during the infection of Plasmodium sporozoites in HepG2 cells, suggesting their putative role in regulating the Plasmodium infection during the liver stage of malaria.

The identification of the promoter region is crucial for elucidating the physiological functions and mapping the orchestration of highly specific expression and regulation of any gene [30]. In this study, we used experimental CAGE data from Genomatix and FANTOM 5 to identify TSS and CRE in the 5′ UTR region of the STK35L1 gene. CAGE is a high-throughput method that utilizes the 5′ caps of the mRNA transcripts for mapping and identifying the TSS [31]. Based on the TSS, the promoter regions were identified and further analyzed for histone-free chromatin regions. For an active expression of a gene, the promoter region and CRE should be histone-free, allowing them to be accessible to the transcription machinery for the initiation of transcription. We utilized the experimental datasets from the ENCODE project, which comprise DNA-seq and ChIP-seq data from 864 human cell types [32]. Chromatin, where it lost its condensed structure, is highly sensitive to the DNase I enzyme, making the DNA exposed for the interaction with various transcription and regulatory factors. CGIs are regions with elevated CpG density and G + C content, and they colocalize with the majority of promoters [33]. CGIs are relatively nucleosome-deficient, allowing greater accessibility of DNA to the transcriptional regulators [34]. In this study, CGIs and DHSs were identified using the ENCODE project data in the promoter region of STK35L1, confirming that the identified promoter region is histone-free and active.

Epigenetic modifications, such as post-translational modifications of histones, play a crucial role in regulating gene expression. H3K4me3 modification is highly enriched at the TSS and enhances transcription by attracting various transcription-associated factors [35]. Similarly, H3K27ac is also associated with active enhancer and promoter regions. In this study, we reported both types of epigenetic modification in the promoter regions, indicating the presence of CREs. These data suggest that the identified promoter region of the STK35L1 gene is active and functional and contains CREs.

The E2F family comprises 9 members that regulate a wide variety of genes through both activation and repression, playing a crucial role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [36]. The E2F family is associated with and regulated by retinoblastoma (Rb) during the progression of the cell cycle from G1 to S phase [37]. The E2F family of transcription factors also regulates genes related to DNA damage repair [37]. On the other hand, Plasmodium requires host cells for survival and intracellular protection to facilitate the growth and development of parasites within hepatocytes during infection [21,38]. The role of the E2F family at the liver stage of malaria is yet unknown. Here, we found that E2F1, E2F2, E2F3, and E2F6 were significantly upregulated during sporozoite infection in HepG2 cells, indicating that E2F family members may be essential in the liver stage of malaria.

FOXG1 belongs to the human forkhead box gene family and acts as a transcriptional repressor, thereby maintaining an undifferentiated state in hepatoblastomas [39]. Here, we report significant upregulation of FOXG1 and FOXA1 during early sporozoite infection in HepG2 cells, suggesting their role during the early stages of malaria infection. These TFs may have a specific role in hepatocytes during the infection; however, the exact function in the liver stage of malaria remains to be explored.

Furthermore, we previously reported that STAT3 activation is required for the upregulation of STK35L1 and STAT3 in HepG2 cells during malaria [7]. In line with the previous study, we also found the significant downregulation of STAT5A during the early stages of sporozoite infection [21]. STAT5A plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of various tumors by activating its downstream genes, which are involved in the growth and survival of cancer. However, its role in the liver stage of malaria has not yet been deciphered [40,41]. Additionally, we found that STAT6, but not STAT5B, is downregulated in the early stage of infection. These data suggest that the STAT family members might be important in the liver stage of malaria.

MYBL2 is a TF factor belonging to the MYB family of TFs, which interacts with cyclin A and promotes the progression of the cell cycle. Previous studies have shown that it is highly expressed in cancer cells as well as in several human tumors [42]. In this study, we reported significant downregulation of MYBL2 during sporozoite infection, suggesting a negative association with sporozoite infection during the liver stage of malaria. The role of MYBL2 in malaria is not yet understood, but it may play a role in altering cell cycle genes during hepatocyte infection. TCF3 belongs to the family helix–loop–helix and can increase proliferation while simultaneously suppressing apoptosis. Remarkably, TCF3 accelerated the rate of angiogenesis and DNA synthesis [43]. Here, we reported significant downregulation of TCF3 during early sporozoite infection; however, highly significant upregulation of TCF3 was observed at 48 h post-infection. During P. yoelii infection, the parasite develops cellular defense strategies and immune suppression, which leads to the activation of several signaling pathways by stimulating the expression of host-specific genes. Some of these genes, such as TCF3, CDKN2A, PARP1, and let-7a-5p, were reported to be involved in cell proliferation and DNA synthesis [44]. Here, we found significant upregulation of SOX2 during sporozoite infection in HepG2 cells. SOX2 is associated with cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis in various types of cancer [45]. Additionally, the overexpression of SOX2 in cancer is positively correlated with drug resistance [46]. The role of SOX2 in sporozoite infection has not been explored.

The SMAD family comprises eight members: SMAD1 through SMAD8. Activation of these TFs occurred through the phosphorylation of TGF-β and activin receptors. Receptor-activated SMADs are known as R-SMADs and are translocated into the nucleus by forming a heterotrimeric complex [47]. The ligand (TGF-β) binds to its receptor and activates its receptor’s kinase domains, which initiates the phosphorylation cascade of the SMAD TFs. TGF-β is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that plays a crucial role in preventing severe malaria in mice. TGF-β secretion during the pathogenesis of malaria is correlated with a decreased clinical malaria burden in humans [48]. In this study, we reported that SMAD3 is significantly upregulated in HepG2 cells infected with P. berghei sporozoites. The role of SMAD3 during the liver stage of malaria is yet to be explored. These data suggest that the differential expression of these TFs during Plasmodium sporozoites infection in HepG2 cells is regulated by a STAT3-independent signaling pathway.

Together, in this study, we identified and characterized the STK35L1 promoter using ChIP experimental data from ENCODE and published resources. We identified various transcription factors (TFs) that may interact with the STK35L1 promoter. To validate the direct binding of the TFs, AlphaFold models were generated, and interacting promoter DNA sequences for TFs were identified. We report for the first time that all identified TFs, except E2F4, were differentially regulated during the infection of P. berghei sporozoites in HepG2 cells. These findings suggest that these TFs may play a pivotal role during the liver stage of malaria.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

All the primers involved in this study were procured from Eurofins, Karnataka, India. ML115, a specific activator, and STAT3, a specific inhibitor of STAT3, were procured from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

4.2. Mosquito Rearing and Sporozoite Production

C7BL/6 mice were bred in the institute’s facilities according to the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of NII, New Delhi, India, and all experiments were conducted in accordance with the CPCSEA guidelines (Government of India). The GFP-expressing P. berghei ANKA sporozoites were produced as described before [7]. In brief, the starved mosquitoes were fed on 6 to 8-week-old mice. After infection, mosquitoes were maintained at 19 °C, 70–80% relative humidity, and a 12 h light cycle for 18 days. The mosquitoes were fed on a 20% sucrose solution during this period. After 18 days, mosquitoes were washed and dissected in complete DMEM without antibiotics. Salivary glands were isolated and ground gently in complete DMEM to release the sporozoites. The number of sporozoites was determined using a hemocytometer.

4.3. Cell Culture and HepG2 Cell Infection

All in vitro experiments were conducted using the HepG2 cell line, which was routinely cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For gene expression analysis, cells were grown (1 × 106 cells/well) in 6-well plates. After 4 h, sporozoites (1 × 105 sporozoites/well) were added, and then the cells were harvested at various time points after infection. The infected cells were sorted via FACS (BD FACSAria™, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The control (non-infected) and GFP-positive cells (infected) were lysed using Trizol reagent, and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

4.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

The cDNA was synthesized with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The gene-specific primers (Table S4) were designed using the NCBI Primer Blast tool, and qPCR was performed on a Mastercycler ep realplex (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and a CFX Opus 96 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Cycling program: 7 min at 95 °C and then 40 cycles with 10s at 95 °C and 20s at 60 °C. The specificity of the amplicons was analyzed by thermal dissociation curve and agarose gel electrophoresis. Data were normalized against the housekeeping gene, GAPDH.

4.5. Promoter Prediction

The ElDorado/Gene2Promoter tool of the Genomatix software suite v3.10 with the Eldorado/Gene2Promoter tool was used for the identification of the promoter of STK35L1. The sequences of the selected promoter regions were retrieved in GenBank format using Genomatix with a custom-defined length, i.e., 1000 bp upstream to the first TSS and 500 bp downstream of the last TSS. The cis-regulatory features of the promoter were analyzed using data collected from the ENCODE consortium [23], which comprises data from 864 human cell types, accessed through the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu, accessed on 10 January 2024).

The transcription factor binding sites were predicted by the MatInspector tool (Genomatix software suite v3.10), which uses nucleotide/positional weight matrix (NWM/PWM) to describe the TFBS. Enrichr, an open web resource that consolidates various in vitro studies under one umbrella (ChEA 2022 [26], FANTOM5 [22], and ENCODE [23]), was used to identify putative transcription factors associated with STK35L1.

4.6. Protein–DNA Modelling

For modeling the transcription factors and the promoter complex, we utilized the AlphaFold 3 server (https://alphafoldserver.com, accessed on 10 November 2025). The sequence of the transcription factors was retrieved from the NCBI (Table 1). The retrieved transcription factor protein sequences, along with the STK35L1 promoter nucleotide sequence, were submitted to the AlphaFold server. For each transcription factor-DNA model, 5 models ranking 0–4 were predicted, which were analyzed. The visualization of the model and image generation were done using PyMol (version 2.5.4) software.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed three times independently with different cell passages. Statistical analysis was performed on GraphPad PRISM 7 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) using one-way ANOVA. The p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results were calculated as the mean ± SD, and the data are shown as the mean + SD.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/kinasesphosphatases3040026/s1. Table S1: List of TSS and their genomic coordinates; Table S2: List of transcription factors identified in different high-throughput datasets; Table S3: List of putative binding regions of TFs identified by Genomatix/MatInspector; Table S4: List of Primers used in qPCR; Supplementary File S1: The sequences of identified promoters; Figure S1: Models of TF-promoter complex.

Author Contributions

A.Y.: conceptualization, methodology, writing- original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, investigation, validation, data curation. P.K.S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, validation, data curation, visualization, formal analysis. M.H.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, software. P.G. (Pragya Gehlot): visualization, writing—review and editing, formal analysis. S.B.: visualization, writing—review and editing, investigation. M.S.: visualization, writing—review and editing. K.G.: visualization, writing—review and editing. A.P.A.: investigation. M.T.: visualization, writing—review and editing. D.M.S.: visualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. A.P.S.: visualization, conceptualization, validation, methodology, supervision. D.B.: Writing—review and editing, visualization, investigation, conceptualization, validation. P.G. (Pankaj Goyal): conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, investigation, validation, data curation, formal analysis, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research: 6/9-7(234)2020/ECD-II, Science and Engineering Research Board: DST-SERB CRG/2022/007356, and the Department of Biotechnology, Govt of India (DBT Builder Project (BT/INF/22/SP44383/2021).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been pre-approved by the Ethic committee name-Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBSC), Central University of Rajasthan (CURAJ), India, (DBT/OM-BT/BS/17/555/2013-PID, Approval Date: 8 May 2019), and Ethics Committee Name: Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), National Institute of Immunology (NII), New Delhi, India, (IAEC/NII#535/19, Approval Date: 30 July 2020).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

A.Y. and P.G. (Pragya Gehlot) are the recipients of fellowships from DBT, Govt. of India (DBT/2020/CUR/1470) and CSIR, Govt. of India (CSIR-NET SRF; 09/1131(0039)/2019-EMR-I), respectively. We thank the Kinases and Phosphatases editorial staff and MDPI for the free APC support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| STAT | Signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| SMAD | Suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic |

| MYBL2 | MYB Proto-Oncogene Like 2 |

| TCF3 | Transcription factor 3 |

| FOX | Forkhead-box |

| TF | Transcription factor |

| AF3 | AlphaFold 3.0 |

References

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2024: Addressing Inequity in the Global Malaria Response; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- von Seidlein, L.; Peto, T.J.; Landier, J.; Nguyen, T.-N.; Tripura, R.; Phommasone, K.; Pongvongsa, T.; Lwin, K.M.; Keereecharoen, L.; Kajeechiwa, L.; et al. The impact of targeted malaria elimination with mass drug administrations on falciparum malaria in Southeast Asia: A cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2019, 16, e1002745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerig, C.; Abdi, A.; Bland, N.; Eschenlauer, S.; Dorin-Semblat, D.; Fennell, C.; Halbert, J.; Holland, Z.; Nivez, M.-P.; Semblat, J.-P.; et al. Malaria: Targeting parasite and host cell kinomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arang, N.; Kain, H.S.; Glennon, E.K.; Bello, T.; Dudgeon, D.R.; Walter, E.N.F.; Gujral, T.S.; Kaushansky, A. Identifying host regulators and inhibitors of liver stage malaria infection using kinase activity profiles. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudêncio, M.; Rodrigues, C.D.; Hannus, M.; Martin, C.; Real, E.; Gonçalves, L.A.; Carret, C.; Dorkin, R.; Röhl, I.; Jahn-Hoffmann, K.; et al. Kinome-wide RNAi screen implicates at least 5 host hepatocyte kinases in Plasmodium sporozoite infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adderley, J.D.; John von Freyend, S.; Jackson, S.A.; Bird, M.J.; Burns, A.L.; Anar, B.; Metcalf, T.; Semblat, J.-P.; Billker, O.; Wilson, D.W.; et al. Analysis of erythrocyte signalling pathways during Plasmodium falciparum infection identifies targets for host-directed antimalarial intervention. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.K.; Kalia, I.; Kaushik, V.; Brünnert, D.; Quadiri, A.; Kashif, M.; Chahar, K.R.; Agrawal, A.; Singh, A.P.; Goyal, P. STK35L1 regulates host cell cycle-related genes and is essential for Plasmodium infection during the liver stage of malaria. Exp. Cell Res. 2021, 406, 112764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Behring, A.; Kumar, A.; Siess, W. STK35L1 associates with nuclear actin and regulates cell cycle and migration of endothelial cells. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, P.; Behring, A.; Kumar, A.; Siess, W. Identifying and characterizing a novel protein kinase STK35L1 and deciphering its orthologs and close-homologs in vertebrates. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, Y.; Whiley, P.A.F.; Goh, H.Y.; Wong, C.; Higgins, G.; Tachibana, T.; McMenamin, P.G.; Mayne, L.; Loveland, K.L. The STK35 locus contributes to normal gametogenesis and encodes a lncRNA responsive to oxidative stress. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio032631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, T.; Xu, P.; Liu, Z.; Ma, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Mapping functional elements of the DNA damage response through base editor screens. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 115047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Yamashiro, T.; Asally, M.; Masui, A.; Wong, C.; Loveland, K.L.; Yoneda, Y. Nuclear retention of importin α coordinates cell fate through changes in gene expression. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S. Serine/Threonine kinase 35, a target gene of STAT3, regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of osteosarcoma cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 45, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhu, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Qian, J. STK35 Is ubiquitinated by NEDD4L and promotes glycolysis and inhibits apoptosis through regulating the AKT signaling pathway, influencing chemoresistance of colorectal cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 582695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanskaya, S.A.; Moreno, R.Y.; Lu, B.; Feng, R.; Yao, Y.; Irani, S.; Klingbeil, O.; Yang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Demerdash, O.E.; et al. SCP4-STK35/PDIK1L complex is a dual phospho-catalytic signaling dependency in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Qin, L.; Liu, G.; Zhao, S.; Peng, N.; Chen, X. Dynamic balance of pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 in C57BL/6 mice infected with lethal Or nonlethal Plasmodium yoelii. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2008, 5, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Amodu, A.S.; Pitts, S.; Patrickson, J.; Hibbert, J.M.; Battle, M.; Ofori-Acquah, S.F.; Stiles, J.K. Heme mediated STAT3 activation in severe malaria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Jove, R. The STATs of cancer—new molecular targets come of age. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, G.B.; Reichenbach, P.; Schindler, U.; Horvath, C.M.; Fritz, S.; Nabholz, M.; Bucher, P. DNA binding specificity of different STAT proteins: Comparison of in vitro specificity with natural target sites. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6675–6688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, R.; de la Vega, P.; Paik, S.H.; Murata, Y.; Ferguson, E.W.; Richie, T.L.; Ooi, G.T. Early transcriptional responses of HepG2-A16 liver cells to infection by Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 26396–26405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, S.S.; Carret, C.; Grosso, A.R.; Tarun, A.S.; Peng, X.; Kappe, S.H.I.; Prudêncio, M.; Mota, M.M. Host cell transcriptional profiling during malaria liver stage infection reveals a coordinated and sequential set of biological events. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizio, M.; Harshbarger, J.; Shimoji, H.; Severin, J.; Kasukawa, T.; Sahin, S.; Abugessaisa, I.; Fukuda, S.; Hori, F.; Ishikawa-Kato, S.; et al. Gateways to the FANTOM5 promoter level mammalian expression atlas. Genome Biol. 2015, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunham, I.; Kundaje, A.; Aldred, S.F.; Collins, P.J.; Davis, C.A.; Doyle, F.; Epstein, C.B.; Frietze, S.; Harrow, J.; Kaul, R.; et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 2012, 489, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartharius, K.; Frech, K.; Grote, K.; Klocke, B.; Haltmeier, M.; Klingenhoff, A.; Frisch, M.; Bayerlein, M.; Werner, T. MatInspector and beyond: Promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 2933–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.Y.; Tan, C.M.; Kou, Y.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Meirelles, G.V.; Clark, N.R.; Ma’Ayan, A. Enrichr: Interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachmann, A.; Xu, H.; Krishnan, J.; Berger, S.I.; Mazloom, A.R.; Ma’ayan, A. ChEA: Transcription factor regulation inferred from integrating genome-wide ChIP-X experiments. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2438–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madoux, F.; Koenig, M.; Nelson, E.; Chowdhury, S.; Cameron, M.; Mercer, B.A.; Roush, W.; Frank, D.; Hodder, P. Modulators of STAT transcription factors for the targeted therapy of cancer (STAT3 activators). In Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program [Internet]; National centre for Biotechnology Information: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schust, J.; Sperl, B.; Hollis, A.; Mayer, T.U.; Berg, T. Stattic: A small-molecule inhibitor of STAT3 activation and dimerization. Chem. Biol. 2006, 13, 1235–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberle, V.; Stark, A. Eukaryotic core promoters and the functional basis of transcription initiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, T.; Kondo, S.; Katayama, S.; Waki, K.; Kasukawa, T.; Kawaji, H.; Kodzius, R.; Watahiki, A.; Nakamura, M.; Arakawa, T.; et al. Cap analysis gene expression for high-throughput analysis of transcriptional starting point and identification of promoter usage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 15776–15781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Hitz, B.C.; Gabdank, I.; Hilton, J.A.; Kagda, M.S.; Lam, B.; Myers, Z.; Sud, P.; Jou, J.; Lin, K.; et al. New developments on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D882–D889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.M.; Bird, A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Carrozzi, V.R.; Braas, D.; Bhatt, D.M.; Cheng, C.S.; Hong, C.; Doty, K.R.; Black, J.C.; Hoffmann, A.; Carey, M.; Smale, S.T. A unifying model for the selective regulation of inducible transcription by CpG islands and nucleosome remodeling. Cell 2009, 138, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beacon, T.H.; Delcuve, G.P.; López, C.; Nardocci, G.; Kovalchuk, I.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Davie, J.R. The dynamic broad epigenetic (H3K4me3, H3K27ac) domain as a mark of essential genes. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, D.; David, G.J. Distinct and overlapping roles for E2F family members in transcription, proliferation and apoptosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bracken, A.P.; Ciro, M.; Cocito, A.; Helin, K. E2F target genes: Unraveling the biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epiphanio, S.; Mikolajczak, S.A.; Gonçalves, L.A.; Pamplona, A.; Portugal, S.; Albuquerque, S.; Goldberg, M.; Rebelo, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Akinc, A.; et al. Heme oxygenase-1 Is an anti-inflammatory host factor that promotes murine plasmodium liver infection. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 3, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, A.M.; Nguyen, Y.; Guanaratne, P.; Pulliam, J.; Lopez-Terrada, D.; Margolin, J.; Finegold, M. FOXG1 is overexpressed in hepatoblastoma. Hum. Pathol. 2007, 38, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Shang, L.; Pan, B.-Q.; Wang, X.-M.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Hao, J.-J.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhan, Q.-M.; et al. Calreticulin promotes migration and invasion of esophageal cancer cells by upregulating neuropilin-1 expression via STAT5A. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 6153–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagvadorj, A.; Kirken, R.A.; Leiby, B.; Karras, J.; Nevalainen, M.T. Transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 promotes growth of human prostate cancer cells in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicirò, Y.; Sala, A. MYB oncoproteins: Emerging players and potential therapeutic targets in human cancer. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Fan, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, R.; Wang, X.; Bo, H.; Zhu, F.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Z.; Xing, L.; et al. TCF3 regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of human spermatogonial stem cells by targeting PODXL. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 695545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wu, J.; Pattaradilokrat, S.; Tumas, K.; He, X.; Peng, Y.-C.; Huang, R.; Myers, T.G.; Long, C.A.; Wang, R.; et al. Detection of host pathways universally inhibited after Plasmodium yoelii infection for immune intervention. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, D.; Hüser, L.; Elton, J.J.; Umansky, V.; Altevogt, P.; Utikal, J. SOX2 in development and cancer biology. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D.; Bauer, J.; Wise, P.; Krüger, M.; Simonsen, U.; Wehland, M.; Infanger, M.; Corydon, T.J. The role of SOX family members in solid tumours and metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 67, 122–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. Smad-dependent and smad-independent pathways in TGF-β family signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, F.M.; de Souza, J.B.; Corran, P.H.; Sultan, A.A.; Riley, E.M. Activation of transforming growth factor β by malaria parasite-derived metalloproteinases and a thrombospondin-like molecule. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 198, 1817–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).