Abstract

Soil acidity severely constrains coffee production by reducing nutrient availability and promoting aluminum toxicity and oxidative stress. Foliar zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have been proposed as redox modulators that can improve nutrient homeostasis under abiotic stress. However, the safe and effective range of Coffea arabica L. remains unclear. In this study, seedlings were grown in acidic soil and sprayed twice with ZnO NPs at 10, 25, 50, and 100 mg L−1. Morphophysiological, biochemical, and ionomic parameters were evaluated fifty days after treatment. Moderate ZnO NPs doses led to intermediate stomatal conductance values, whereas net photosynthesis showed intermediate but non-significant responses only at 10–25 mg L−1, with higher doses (50–100 mg L−1) causing a marked decline. These doses did not significantly modify hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) or malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in leaves or roots. In contrast, the highest dose (100 mg L−1) induced a marked increase in H2O2 without affecting MDA, indicating a partial oxidative response rather than clear lipid peroxidation. Foliar analysis showed that 50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs significantly increased P compared with the optimal soil, while Ca and K remained statistically similar across treatments. Na in the optimal soil was comparable to the 10–25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatments, whereas Na at 50–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs was significantly reduced and foliar Zn increased markedly with increasing nanoparticle dose. Proline accumulation reflected a dose-dependent osmotic adjustment, and chlorophyll ratios indicated adaptive photoprotection. Overall, foliar ZnO NPs mitigated acidity-induced stress through physiological and ionomic adjustment, with 10–25 mg L−1 identified as the physiologically safe range for C. arabica seedlings grown under acidic conditions.

1. Introduction

Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) is a strategic crop in the tropical belt known as the “coffee belt”, with high economic and social relevance for more than 50 producing countries and millions of small farmers [1]. In global terms, it is one of the main agricultural raw materials for export and is a source of livelihood for around 25 million families, especially in tropical and subtropical regions [2]. In the 2022/2023 cycle, global production was estimated at 168.2 million 60 kg bags, which showed stagnation compared to the previous year and underlines the vulnerability of the production system to changing environmental and management conditions [3]. Beyond demand and market, crop performance depends critically on soil and climate factors [4].

On a global scale, acidity affects approximately 30% of Earth’s surface. It affects about 50% of potential arable land, concentrated in tropical and subtropical areas, where more than 40% of soils are acidic, and Ca, Mg, and P deficiencies predominate, along with Al3+ and Mn2+ toxicity [5]. In acidic soils, the greater solubility of aluminum (Al3+) and, sometimes, manganese (Mn) induces root toxicity, growth inhibition, and generates morphological, physiological, biochemical, and nutritional disorders, such as reduced availability of P, Ca, and Mg in soils [6,7,8].

In coffee, various works from cell cultures to seedlings in nutrient solution have shown sensitivity to Al3+, with alterations in root growth, changes in metabolism, cell damage, and the presence of aluminum [9,10,11]. Recent field studies also confirm that pH < 5.0 can predominate on coffee farms, a range that favors Al3+ toxicity and compromises soil fertility [7]. For the Geisha variety, widely recognized for its sensory profile, information on its tolerance to acidic soils is still limited; some studies suggest that it thrives in soils with a pH close to 5–6, implying that its adaptation to very low pH (<5) or conditions of high Al/Mg toxicity still needs to be investigated [12]. In addition to nutritional constraints, soil acidity alters key physiological processes: Al3+ toxicity reduces Ca and Mg absorption and affects stomatal opening, which decreases conductance and net photosynthesis [7,13,14]. At the redox level, acid stress interferes with electron transport. It promotes the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as O2− and H2O2, which can exceed the capacity of the enzymatic antioxidant system (SOD, CAT, APX) and nonenzymatic (carotenoids, phenols) [15,16]. This imbalance increases the risk of lipid peroxidation and compromise of cellular integrity. In coffee, exposure to low pH has been reported to reduce photosynthetic pigments and photochemical efficiency, activating compensatory antioxidant responses [17,18].

To counteract acidity, growers employ practices such as liming with carbonates or hydroxides, applying organic matter, and using fertilizers rich in Ca and Mg to restore cation balance and improve soil buffering capacity [19]. In countries with volcanic or highly leached soils, liming can increase pH by more than 1 unit and double P availability when applied correctly [20]. However, the effectiveness of these practices varies depending on the variety’s texture, cation exchange capacity, and genetics [21].

In parallel, agriculture is exploring nanotechnologies to support crop resilience to abiotic stresses. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) derived from an essential micronutrient have received attention for their potential to modulate nutrition (Zn as a cofactor), antioxidant machinery, and photosynthetic processes, with effects depending on size, dose, coatings, route of application, and plant species [22]. Recent reviews report increases in photosynthetic pigments and antioxidant enzyme activity in response to ZnO NPs in several species; however, they warn that excesses or inadequate formulations can cause phytotoxicity and redox imbalances, which require establishing safety windows and responsible application protocols [22,23].

In coffee, recently, the effect of ZnO NPs under salinity has been reported, with respect to physiological adjustments and the antioxidant system [24]. However, a critical gap remains: to what extent can foliar ZnO NPs buffer oxidative stress and support physiological responses in C. arabica specifically under soil stress (low pH, the presence of Al3+), a frequent scenario in coffee-growing areas.

In this context, the present study aims to evaluate whether the foliar application of ZnO NPs modulates physiological and oxidative status indicators in C. arabica seedlings subjected to acidic soil conditions. Our working hypothesis is that, within safe dose ranges and in a controlled system, ZnO NPs could help sustain pigmentation and attenuate markers of oxidative damage.

2. Results

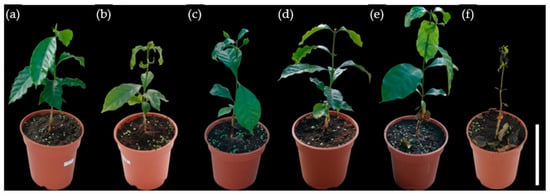

To provide an overview, Figure 1 presents representative photographs of C. arabica seedlings under the different treatments. The control with optimal pH showed vigorous growth and well-expanded leaves, whereas the acidic soil showed smaller leaves and signs of leaf wilt. Seedlings treated with 10 and 25 mg L−1 of ZnO NPs showed a morphology similar to that observed in acidic soil, with no visible improvements in development. At the highest concentrations, 50 and 100 mg L−1 of ZnO NPs, lower overall vigor was observed, particularly at 100 mg L−1, where leaf reduction was more pronounced, and leaf drop was evidenced.

Figure 1.

Representative phenotypic appearance of C. arabica seedlings under ZnO NPs treatments and control conditions. (a) Optimal soil; (b) acidic soil; (c) ZnO NPs 10 mg L−1; (d) ZnO NPs 25 mg L−1; (e) ZnO NPs 50 mg L−1; (f) ZnO NPs 100 mg L−1. White scale bar = 15 cm.

2.1. Relative Chlorophyll Content and Stomatal Conductance (Gs)

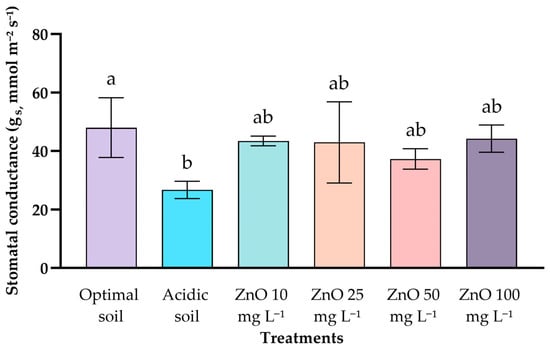

No significant differences in relative chlorophyll content were found between treatments (p = 0.80), with values ranging from 48 to 56 SPAD units. On the other hand, the gs (Figure 2) showed a significant difference only between the controls (plants grown in acidic soil had the lowest conductance (26.7 ± 2.95 mmol m−2 s−1), while the control with optimal pH registered the highest value (47.97 ± 10.22 mmol m−2 s−1). Foliar applications of ZnO NPs (10–100 mg L−1) showed intermediate values (37.3–44.2 mmol m−2 s−1), statistically similar to both controls, without evidence of a significant effect of ZnO NPs on gs.

Figure 2.

Effect of ZnO NPs of coffee seedlings under acid stress on the values of gs. Different letters indicate significant differences according to the Tukey HSD test (p = 0.0255).

2.2. Net Photosynthesis Rate (A, μmol CO2 m−2 s−1)

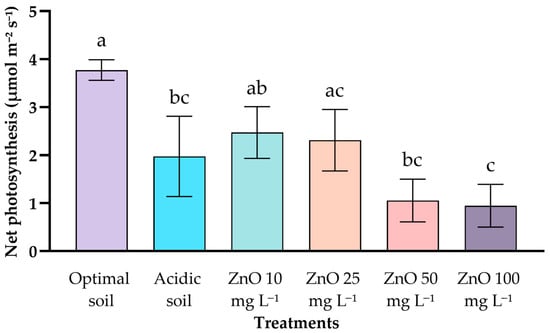

The net photosynthetic rate differed significantly among treatments (Figure 3). The control at optimal pH exhibited the highest value (3.77 ± 0.21 μmol m−2 s−1), while the acidic soil control showed a marked reduction (1.97 ± 0.84 μmol m−2 s−1). Foliar applications of ZnO NPs at 10 and 25 mg L−1 resulted in intermediate photosynthetic rates (2.47 ± 0.54 and 2.31 ± 0.64 μmol m−2 s−1), which were statistically similar to the acidic control. In contrast, higher doses (50 and 100 mg L−1) significantly reduced photosynthesis (1.05 ± 0.44 and 0.95 ± 0.44 μmol m−2 s−1), with the 100 mg L−1 dose being considerably lower than all other treatments. These results indicate a dose-dependent decline in photosynthetic activity at high ZnO NP concentrations, while moderate doses maintained intermediate, non-significant trends relative to the acidic control.

Figure 3.

Effect of ZnO NPs of coffee seedlings under acid stress on photosynthesis. Different letters indicate significant differences according to the Tukey HSD test (p < 0.001).

2.3. Elemental Content in Leaves and Roots

Table 1 shows the mineral nutrient content (μg g−1 dry weight) in leaves of C. arabica seedlings grown in soils with different pH and treated with different concentrations of ZnO NPs. The soil with optimal pH presented the highest concentrations of K (15,354.94 ± 963.14 μg g−1) and Ca (14,822.83 ± 829.93 μg g−1), whereas Mg was higher under acidic soil conditions (3356.89 ± 251.87 μg g−1) than in the optimal pH treatment (2599.46 ± 113.82 μg g−1). Under acidic conditions, K and Ca decreased by 9.72% and 38.36%, respectively, compared with the optimal pH soil.

Table 1.

Mineral nutrient content (μg g−1 DW) in leaves of C. arabica seedlings treated with different concentrations of ZnO NPs.

The application of ZnO NPs modified these patterns. The 50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatment showed the highest P concentration (2101.29 ± 145.36 μg g−1), significantly exceeding only the optimal soil control, while remaining statistically similar to the acidic soil and the other ZnO NPs doses. Although the 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatment resulted in the lowest K concentration, it was not significantly different from the acidic soil, 25 mg L−1, or 100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatments. Ca also increased to 10,902.36 ± 570.84 μg g−1 at 50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, suggesting a partial enhancement of Ca uptake compared with the acidic soil and the 25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatment. Among micronutrients, Zn increased dramatically from 8.65 ± 1.82 μg g−1 (acidic soil) to 52.71 ± 3.67 μg g−1 (100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs), and Mn from 71.04 ± 1.72 μg g−1 (optimal soil) to 263.26 ± 0.63 μg g−1 (25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs). Fe and Cu presented minor variations, possibly associated with competition between divalent cations.

Treatments with ZnO NPs modified the nutritional profile of the roots. The 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs dose promoted the highest accumulation of Ca (23,225.79 ± 653.29 μg g−1) and Mn (168.69 ± 6.89 μg g−1). In contrast, the highest levels of Fe (590.75 ± 70.19 μg g−1) and Zn (28.67 ± 0.52 μg g−1) were recorded with the 100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs treatment, both being significantly greater than those observed under acidic soil conditions. These patterns reflect specific dose-dependent responses to nanoparticle application (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mineral nutrient content (μg g−1 DW) in roots of C. arabica seedlings treated with different concentrations of ZnO NPs.

2.4. Photosynthetic Pigment Content

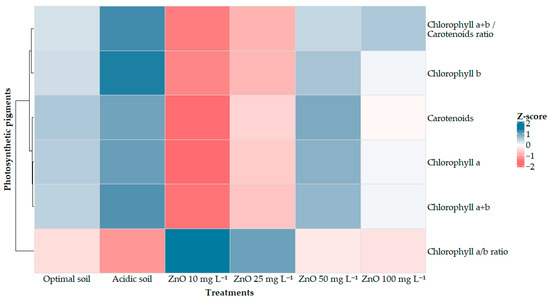

The evaluation of photosynthetic pigments revealed advantageous responses of leaves of plants grown under acidic soil conditions due to the foliar application of ZnO NPs. (Figure 4). In general, the content of chlorophylls (a, b, and total) and carotenoids was significantly affected by the dose, with a marked reduction evident in the heat map with the application of 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, followed by partial recovery at higher concentrations.

Figure 4.

Heat map of photosynthetic pigments in Coffea arabica grown in acidic soil and treated with ZnO NPs. The values are represented as Standardized Z-scores, so the figure shows only relative trends between treatments. The original concentrations (mean ± SE) and statistical differences are shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

In chlorophyll a, the heatmap shows that the highest values correspond to the acidic soil, with no notable differences with respect to the optimal soil or to the treatments with 50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs and 100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs. In contrast, 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs are clearly represented as the point of least intensity (negative z-score) and 25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs as a partial recovery. A similar pattern was observed for chlorophyll b, with maximum values in acidic soil and optimal soil, a sharp decrease at 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, and a progressive recovery at 25–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs.

Consequently, total chlorophyll (a + b) reaches its highest representation in acidic soil, followed by optimal soil. At the same time, treatment with 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs appears as the lowest level, and doses of 25–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs show gradual recovery. Carotenoids showed relatively stable behavior across treatments, with maximum intensities in the acidic and optimal soils. However, 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs is again identified as the treatment with the greatest reduction, while 25–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs tend to recover on the heat map.

The chlorophyll a/b ratio reflected a physiological response to stress, with the highest values at 10 and 25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, higher than in the controls, and decreasing to intermediate levels with 50–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs. In addition, the ratio (a + b)/carotenoids showed its highest intensity in acidic soil and the minimum with 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, with a tendency to recovery between 25 and 100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs; some treatments (50–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) reached levels close to or above optimal soil, although not exceeding the values of acidic soil.

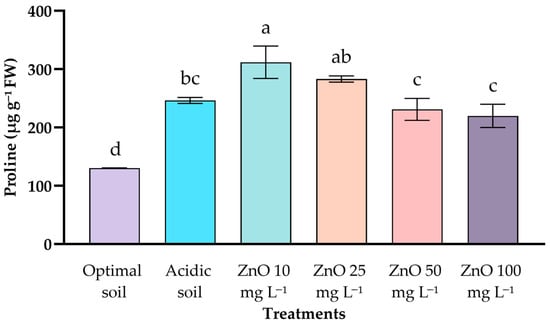

2.5. Proline Content

Proline accumulation showed differential responses among organs to ZnO NPs under acidic soil conditions.

In leaves, no significant differences were recorded between treatments. Values ranged from 315.4 ± 7.0 to 336.3 ± 13.6 μg g−1 FW, remaining comparable between optimal pH control, acid control, and ZnO NPs applications at all concentrations (10–100 mg L−1). In roots, on the other hand, significant differences were detected (Figure 5). The optimal soil treatment presented the lowest value (130.3 ± 0.5 μg g−1 FW), while the control in acidic soil showed a notable increase (246.4 ± 5.2 μg g−1 FW). Application of 10 mg L−1 of ZnO NPs promoted the greatest root accumulation (311.8 ± 27.7 μg g−1 FW), followed by a progressive decrease in doses of 25–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs (220–283 μg g−1 FW).

Figure 5.

Effect of ZnO NPs of coffee seedlings under acid stress on root proline content. Different letters indicate significant differences according to the Tukey HSD test (p < 0.001).

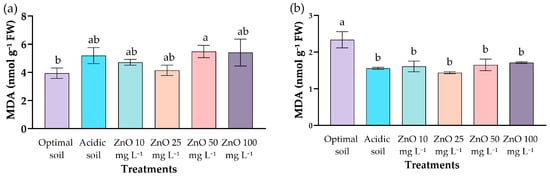

2.6. Lipid Peroxidation in Leaves and Roots

The MDA content in leaves showed significant differences only between the positive control (3.94 ± 0.37 nmol g−1 FW) and the 50 mg L−1 dose of ZnO NPs (5.48 ± 0.44 nmol g−1 FW), which presented the highest value (Figure 6). Both acidic soil (5.19 ± 0.57 nmol g−1 FW) and foliar applications of 10, 25, and 100 mg L−1 of ZnO NPs showed intermediate values (4.14–5.41 nmol g−1 FW) and were statistically similar to each other, with no differences compared to acidic soil (Figure 6a). These results indicate that the application of ZnO NPs did not modify lipid peroxidation levels compared to the acidic soil, except for the 50 mg L−1 treatment, which showed a significant increase in MDA compared to the plantation grown in soil of optimal pH.

Figure 6.

Effect of ZnO NPs of coffee seedlings under acid stress on MDA content in (a) leaves and (b) roots. Different letters indicate significant differences (p = 0.016, p < 0.001) based on Tukey’s HSD test.

In roots (Figure 6b), the trend was reversed. The control at optimal pH had the highest value (2.34 ± 0.22 nmol g−1 FW), while the control in acidic soil and the treatments with ZnO NPs showed lower concentrations (1.44–1.71 nmol g−1 FW), with no significant differences between them.

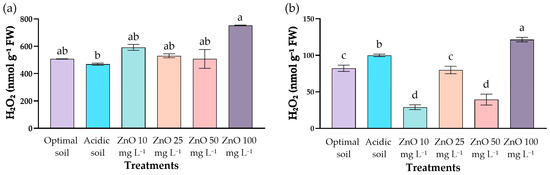

2.7. Hydrogen Peroxide Content

Concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) showed differentiated behaviors between leaves and roots (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of ZnO NPs on H2O2 content in (a) leaves and (b) roots of C. arabica seedlings under acid stress. Different letters indicate significant differences depending on the Kruskal–Wallis test (a) or Tukey’s HSD test (b).

The leaves of plants grown under optimal pH of soil reached 507.4 ± 1.7 nmol g−1 FW of hydrogen peroxide content, whereas the acidic soil showed a slightly lower value of H2O2 (468.9 ± 7.8 nmol g−1 FW) (Figure 7a).

In roots (Figure 7b), the differences were highly significant (p < 0.001). Seedlings with optimal pH recorded the lowest concentration of H2O2 (82.2 ± 4.3 nmol g−1 FW), while those in acidic soil reached 99.9 ± 1.8 nmol g−1 FW. The application of 10 and 50 mg L−1 of ZnO NPs dramatically reduced H2O2 levels (29.0 ± 3.3 and 39.3 ± 7.5 nmol g−1 FW, respectively). In contrast, the higher dose (100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) significantly increased the content (121.5 ± 3.0 nmol g−1 FW).

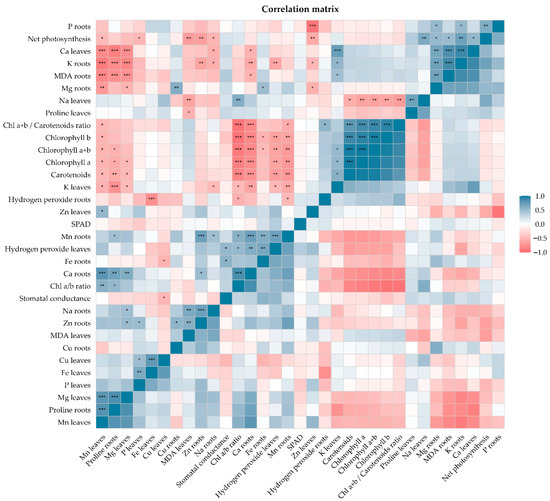

2.8. Physiological, Biochemical, and Nutritional Correlation Matrix

Figure 8 shows the interrelationships among photosynthetic variables, pigments, oxidative stress indicators, and mineral elements in C. arabica seedlings grown in acidic soils. A highly cohesive photosynthetic block was evidenced, where chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll (a + b) and carotenoids presented very high positive correlations (r = 0.93–0.99; p ≤ 10−8), while the chlorophyll a/b ratio was negatively associated with these variables (r = −0.92 to −0.95; p < 0.001), reflecting a coordinated adjustment in the pigment composition under acidity.

Figure 8.

Correlation matrix between physiological, biochemical, and nutritional variables evaluated in coffee seedlings subjected to treatments with ZnO NPs under conditions of stress induced by acidic soil. The lower triangle shows the correlation coefficients obtained by Pearson’s method for normally distributed variables and by Spearman’s method for non-normally distributed variables. The upper triangle indicates the level of statistical significance of each relationship (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). Blue tones represent positive correlations and red tones represent negative ones. The hierarchical order is based on similarity grouping.

Net photosynthesis was positively correlated with K in roots (r = 0.70; p = 0.001) and Ca in leaves (r = 0.54; p = 0.021), and negatively with MDA in leaves (r = −0.68; p = 0.002) and Zn in roots (r = −0.67; p = 0.002). These results indicate that photosynthetic activity is favored by an adequate K–Ca balance and is reduced by oxidative damage and excess Zn in root tissues.

H2O2 in leaves showed negative correlations with chlorophyll a (r = −0.64; p = 0.004) and positive correlations with Mg in roots (r = 0.71; p = 0.001) and Ca in roots (r = 0.61; p = 0.007), evidencing a greater accumulation of Mg and Ca in roots associated with the increase in reactive oxygen species in leaves. Gs was positively correlated with Fe in roots (r = 0.57; p = 0.013) and with foliar H2O2 (r = 0.54; p = 0.020), and negatively with Cu in leaves (r = −0.51; p = 0.032), indicating the participation of metallic micronutrients in stomatal control under acidity.

Finally, a strong antagonism between P and Zn (r = −0.93; p = 2.4 × 10−8) was highlighted, along with negative correlations between calcium in roots and photosynthetic pigments (r = −0.79 to −0.85; p < 0.001). These results show that soil acidification reorganizes the pigment–photosynthesis network, activates antioxidant responses, and modulates ionic gradients (K, Ca, Mn, Zn, and P), forming an adaptive physiological pattern characteristic of C. arabica in acidic environments.

3. Discussion

Foliar application of ZnO NPs generated dose-dependent physiological and ionic responses in C. arabica grown in acidic soils, a scenario that limits photosynthesis, nutrient absorption, and redox balance [7,25]. In our study, moderate doses led to intermediate stomatal conductance and net photosynthesis values, positioned between the optimal and acidic controls but not significantly different from the latter, and enhanced Ca, Fe, P, and K accumulation. In contrast, the highest dose (100 mg L−1) markedly increased H2O2 without significantly affecting MDA, indicating the onset of oxidative stress. These findings address a key gap regarding the safe and functional range of foliar ZnO NPs under soil acidity stress, providing a framework for interpreting the dose-dependent responses described below.

In the present research, the chlorophyll content remained relatively stable across treatments, Consistent with previous studies showing that ZnO NPs do not significantly alter the relative chlorophyll content in coffee, despite associated physiological improvements [22,26]. At the same time, the gs values in our trial remained intermediate between the optimal and acidic controls, a pattern that aligns with reports describing ZnO NP–mediated modulation of gas exchange in coffee and other crops, although these changes are not always statistically significant [24], as in other crops with dose- and formulation-dependent foliar applications [27,28].

In terms of pigments, the effect of ZnO NPs was dose-dependent: 10 mg L−1 intensified stress and reduced pigments, while moderate doses promoted partial recovery. This pattern is consistent with studies showing that optimal doses of ZnO NPs improve photosynthesis and pigment stability by modulating redox reactions and increasing antioxidant activity (SOD, CAT, APX). In contrast, high doses release excessive Zn2+, increase ROS, and accelerate chlorophyll degradation [15,29,30]. Low acidity, the limitation of Mg and Fe, which are essential for chlorophyll synthesis, enhances photooxidative susceptibility [8]. The drop seen at 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs could be explained by synergy between acidity and released Zn. At the same time, intermediate doses exert a protective effect by improving Zn availability and antioxidant response [16].

The increase in the chlorophyll a/b ratio and the reduction in total chlorophyll/carotenoids to 10–25 mg L−1 reflect adaptive photochemical adjustment, associated with a decrease in the size of the LHCII antenna and a greater participation of photoprotective carotenoids. This strategy favors non-photochemical dissipation and protects the PSII [16,31,32]. At higher concentrations (50–100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs), the ratios return to intermediate levels, suggesting photochemical recovery and restoration of the balance between capture and protection pigments. These findings support the idea that ZnO NPs, applied at moderate doses, can act as biostimulants under conditions of acid stress, provided their concentration and ionic release are controlled [33,34,35].

Likewise, the net photosynthetic rate confirmed the operational limit of the ZnO NPs: the soil acid reduced photosynthesis to ≈1.97 μmol m−2 s−1; 10–25 mg L−1 maintained intermediate values between the optimal and acidic controls, without statistically significant recovery relative to the latter; and the highest dose (100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) caused a pronounced decline in photosynthesis [36]. This drop coincides with PSII inhibition and thylakoidal damage under ZnO NPs toxicity [37]. Similarly, Rossi et al. demonstrated in coffee that excess dissolved Zn2+ induces redox imbalance, pigment reduction, and stomatal closure, thereby limiting photosynthetic capacity [22,38,39].

On the other hand, the organ-specific response of proline shows foliar and root maximum invariance at 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs. Recent reviews describe a coupling between proline and reactive oxygen species (ROS): direct sequestration of ROS, stabilization of mitochondrial redox state, and activation of antioxidant defenses [40,41]. Reduction in proline to ≥25 mg L−1 may indicate lower osmotic demand or metabolic feedback under partial restoration of ionic and redox homeostasis, consistent with the hormesis observed with nanomaterials, where low/moderate doses optimize defense and high doses reverse the protective effect [42]. Coherence between greater root proline at 10 mg L−1 ZnO NPs and lower H2O2 in roots at the same range suggests that foliar ZnO triggered systemic signals that favor osmotic adjustment and ROS control in the root system [13,40,41].

The foliar tendency toward increased MDA at 50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs, together with the moderate or low values recorded in roots, suggests an organ-specific pattern of oxidative damage. This behavior coincides with what was reported in Coffea and other cultures treated with ZnO NPs, where intermediate doses reduce lipid peroxidation and structural integrity. However, high doses induce pro-oxidant effects, including ROS accumulation and thylakoidal disorganization [22,43]. The convergence between MDA and elevated H2O2 at high doses reinforces a redox imbalance driven by excess Zn2+, whereas 10–25 mg L−1 likely activate antioxidant mechanisms that limit peroxidation [39,44,45].

H2O2 modulation was dose-dependent and tissue-specific: moderate concentrations promoted antioxidant regulation (↓H2O2), while high concentrations caused oxidative imbalance [15]. This biphasic response aligns with evidence that low doses improve redox damping and photosynthetic stability, whereas high doses induce oxidative damage [46]. Decrease in H2O2 in roots with 10–50 mg L−1 ZnO NPs supports that the availability of ZnO derived from ZnO NPs favors systemic protection and better redox homeostasis [47]. At the same time, its accumulation at high doses reflects saturation of defenses and cell collapse, in agreement with evidence in tea [44,48,49].

In addition, throughout the experimentation, the nutritional content was evaluated, showing that the root–leaf patterns of the ionome reflect coordinated modules of transport and signaling compatible with physiological adjustments under stress [50]. At the whole plant scale, nitrate and phosphate availability “pre-adjusts” the system: the N state governs photosynthetic capacity and amino acid synthesis via the NR–NiR–GS/GOGAT axis, defining the sink strength for cationic co-transport and the supply of organic acids; in parallel, Pi (inorganic phosphate) supports ATP, RuBP regeneration and phospholipid exchange, regulating H+-ATPase/V-ATPase pumps, energy-dependent transport and stomatal function [51,52]. When Pi is limiting, the plant reprograms metabolism (alternative oxidase, organic exudation) and root architecture, while Pi deficiency intensifies Zn and Fe imbalance by P–Zn crosstalk (PHT1/PHO1/PHR1/SPX induction and lipid remodeling) and Fe–P adjustments in uptake/remobilization, expressed as changes in Zn and Fe leaf–root ratios even with constant total supply [51,53].

This “upstream” C–N–P control propagates to K+ and Ca2+ signaling in epidermis and occlusive cells. Leaf enrichment of K (vs. root) usually reflects greater input by AKT1/HAK/KAT and more efficient stomatal regulation (opening/closing), stabilizing photosynthesis and water use under stress [54]. K+ homeostasis depends on rapid activation of plasma membrane H+-ATPase, 14-3-3/CPK, and ROS–Ca2+ loops in occlusive cells; mechanically, these loops couple the flow of K+ with Ca2+ peaks to maintain turgor and protect PSII from Fluctuating light/osmotic [55,56]. Thus, leaves with low K+ and high Ca2+ suggest a tighter stomatal closure (directed by Ca2+) without enough K+ for reopening cycles, which reduces gs and A even with sufficient chlorophyll. On the contrary, high leaf K+ with stable Ca2+ accompanies a better stomatal response and sustained A, consistent with the morphophysiological resilience observed at moderate doses of ZnO NPs [57].

Likewise, Mg2+ acts as the central ion of the chlorophyll molecule and contributes to thylakoidal stacking. At the same time, Mg2+ homeostasis and trafficking (mediated by specific transporters in chloroplasts) are essential to avoid a stromal deficit that limits photosynthesis [58]. In turn, Mn2+ is an integral part of the water oxidation catalytic complex of PSII (the CaMn4O5 cluster) and therefore sets the biochemical ceiling for light capture and oxygen evolution [32]. Typically, Mg-poor leaves (relative to the root) show low SPAD values, lower Rubisco activation, and photochemical necks, signals that covary with the gas exchange measurements in this research [51,59,60]. Mn is essential for the OEC and, together with Fe, for SOD; however, the Fe–Mn antagonism in uptake (IRT1/NRAMP) and xylem load skews the foliar Fe: Mn relationship [61]. The reduction of Fe3+ (FRO2) and its importation as Fe2+ (IRT1) are induced by signs of coumarin deficiency and exudation; however, an excess of Mn2+ competes with IRT1, causing functional iron chlorosis despite a not-so-low total Fe [62].

Finally, Zn and Cu close the micronutrient redox matrix. Zn acts as a cofactor for numerous Zn-finger and Cu/Zn-SOD; its distribution depends on Pi and source–sink flows. Under Pi restriction, the PHT1 pathway and lipid remodeling are induced, accompanied by changes in ZIP/AMF transporters that are usually expressed as higher Zn in roots and selective movement to young leaves; if the leaves show Zn enrichment under Pi restriction, the P–Zn frame predicts it [52,63]. In foliar application, Zn of ZnO NPs can enter through cuticles and stomata, move through phloems, and accumulate in chloroplasts; however, its remobilization may be less efficient than that of ionic Zn2+ (ZnSO4), explaining cases of high leaf Zn without proportional increase in the root or in the whole plant [64]. La homeostasis de Cu SPL7 controlled prioritizes plastocyanin and COX; Low deficiency, activates COPT and miR397/398/408 to sustain transportation In addition, Cu patterns (leaf more constant than root) are compatible with strict plastidial damping and xylem/phloem recycling (YSL–nicotianamine; Golgi HMA7/RAN1 delivery), sustaining the foliar Cu function despite edaphic/translocational “noise” [65].

On the other hand, taking into account the global pattern of correlations, the physiological network under acidity suggests an adjusted pigment modulus that covaries co-energetically to sustain energy capture and management, consistent with the joint regulation of chlorophylls and carotenoids and the use of the chlorophyll a/b ratio as an indicator of photochemical adjustment [66]. Carbon assimilation depends on K–Ca equilibrium, where K+ supports stomatal opening and mesophilic efficiency [67], while Ca2+ stabilizes key components of PSII and OEC (Mn4CaO5 core) [32]. Increased oxidative markers and Zn in roots are associated with photochemical penalty, consistent with the induction of reactive oxygen species and the involvement of PSII in acidic environments [68].

The divergent responses between moderate (25–50 mg L−1) and high (100 mg L−1) ZnO NPs doses can be explained by a balance between Zn2+ availability and the antioxidant capacity of the tissue: low to moderate doses (10–25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) helped maintain ionomic adjustment and partially supported photosynthetic and redox regulation, whereas excessive Zn promotes ROS accumulation and exceeds cellular buffering limits [69,70]. Agronomically, our results identify 10–25 mg L−1 as the physiologically safe operational range for foliar application under acidic soils, while 50 mg L−1 behaved as a transitional dose with early oxidative and photosynthetic penalties, and higher doses pose a clear risk of redox imbalance.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Experimental Conditions

Seedlings of C. arabica var. Geisha were cultured for six months before the start of the experiment. The test was carried out in an experimental greenhouse with an average daytime temperature of 21 °C and a nighttime temperature of 13 °C, a relative humidity of 77%, and an average photosynthetically active radiation of 850 μmol m−2 s−1 under a natural photoperiod of 12 h light/12 h darkness.

The seedlings homogeneous in size and health status were transplanted into 1 kg plastic pots containing acidic soil (pH 2.97 ± 0.05, organic matter 6.37%, sandy-loam texture). The physical and chemical characteristics of the soils used in this experiment are provided in Supplementary Table S2 [71]. During the establishment period (15 days), the plants were watered every three days with Hoagland nutrient solution at 50% concentration [72]. Once established, the plants were arranged under a completely randomized design, with six treatments and five replicates per treatment. Two controls were considered: optimal soil (pH 5.98) and acidic soil (pH 2.97), both without application of ZnO NPs; and four treatments consisting of acidic soil supplemented with ZnO NPs at 10, 25, 50, and 100 mg L−1.

Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs; ≤40 nm, purity > 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were dispersed in distilled water by sonication for 30 min before application. Suspensions were applied foliarly by a single spray to the dropping point (~15 mL plant−1) at 15 and 30 days after transplantation. The experiment was maintained for 60 days, after which physiological and biochemical evaluations were carried out.

4.2. Determination of Relative Chlorophyll Content and Stomatal Conductance

The relative chlorophyll content was determined by direct readings on fully expanded leaves of the middle third of coffee seedlings using a portable chlorophyll meter SPAD-502 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The values were expressed as SPAD units. Gs was measured in the same leaves using a portable SC-1 foliar porometer (Decagon Devices, Pullman, WA, USA), recording the values in mmol m−2 s−1. Measurements were taken on two sheets per plant, and the average of the readings was used for statistical analysis. The evaluations were conducted 50 days after treatment application under controlled greenhouse conditions.

4.3. Measurement of the Net Photosynthesis Rate (A, μmol CO2 m−2 s−1)

It was measured on fully expanded leaves of the middle third of C. arabica seedlings at 50 days of treatment, using a portable LI-6800 photosynthesis system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA). The chamber conditions were adjusted as follows: 600 μmol s−1 airflow, 800 μmol m−2 s−1 photosynthetic photon flux density, 21 °C leaf temperature, 45% relative humidity, and 2.5 rpm fan speed.

4.4. Photochemical Analysis of Photosynthetic Pigments

It was determined from 0.2 g of fresh leaves, which were homogenized in 80% acetone containing magnesium carbonate to prevent chlorophyll degradation. The mixture was centrifuged at 2800 rpm for 10 min at 12 °C, and the supernatant was used for spectrophotometric readings. Absorbances were measured in a UV/Vis spectrophotometer at 663.2, 646.8, and 470 nm. Pigment concentrations were calculated using the following equations described by Lichtenthaler [73].

The results were expressed in fresh weight .

4.5. Elemental Analysis of Leaves and Roots

Herself crushed 0.2 g of freeze-dried plant tissue (leaves and roots) in a nitric acid–hydrochloric mixture following the procedure described by Schmitt [14]. The resulting solution was then filtered and flushed to 25 mL with ultrapure water. Nutrient concentrations were determined by microwave-coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (MP-AES 4100, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), interpolating the values from calibration curves prepared with standard multi-elemental solutions in the ranges of 5, 10, 15, and 20 mg L−1 for P, Ca, Na, K, and Fe, and 2, 5, 10 and 15 mg L−1 for Zn, Mg, Cu and Mn. The results were expressed in μg g−1 of dry mass.

4.6. Colorimetric Quantification of Proline Content

The free proline content was determined following the colorimetric method described by Bates et al. [74]. At 0.5 g of plant tissue, it was homogenized in 5 mL of 3% sulfosalicylic acid (w/v) with a horizontal stirrer for 60 min. It was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30 min, and equal volumes of acid ninhydrin (0.1 M) and glacial acetic acid reagent were added to 1 mL of supernatant. The mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 60 min, rapidly cooled in an ice bath, and 3 mL of toluene was added. The upper phase (supernatant) was recovered, and its absorbance was read at 520 nm in a Genesys 180 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, Madison, WI, USA). Concentrations were calculated by interpolating on a standard curve prepared with L-proline (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). The results were expressed in μmol g−1 dry weight.

4.7. Quantification of MDA (Lipid Peroxidation)

Lipid peroxidation was determined by quantification of malondialdehyde (MDA) using the thiobarbituric acid assay, following the methodology of Velikova et al. [75] with slight modifications. Approximately 200 mg of fresh leaves were homogenized in 2 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (w/v). It was then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min, and 1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid in 20% TCA. The mixture was incubated at 90 °C for 30 min, then rapidly cooled on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min. Absorbance readings were performed on a Genesys 180 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, Madison, WI, USA) at 450, 532, and 600 nm.

MDA content was calculated using the formula [76,77]:

V = final volume of the extract (mL).

W = fresh weight of the sample (g).

4.8. Spectrophotometric Quantification of H2O2 Content

H2O2 content was quantified by spectrophotometry using potassium iodide (KI), following the Loreto and Velikova method [78]. 0.2 g of fresh tissue was cold homogenized with 2 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (w/v). It was then centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, and 1 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of potassium phosphate buffer 10 mM (pH 7.0) and 2 mL of KI 1 M. The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at room temperature, and absorbance was measured at 390 nm on a Genesys 180 UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific™, Madison, WI, USA). The H2O2 content was determined by interpolating on a standard curve prepared with known concentrations of H2O2.

4.9. Data Analysis

The experimental data were organized into spreadsheets and analyzed using ANOVA to determine differences between treatments. When significant differences were detected (p ≤ 0.05), multiple mean comparisons were performed using the Tukey HSD test. When the data did not meet the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk) or homogeneity of variances (Levene), the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was applied, followed by the Dunn post hoc test with Bonferroni correction.

All statistical analyses were carried out in R version 4.5.2 within the RStudio (Version 2025.09.2+418) environment, using the agriculturae, rstatix, FSA, car, dplyr, purrr, and ggplot2 libraries [79,80,81,82,83,84,85]. Comparative figures and bar graphs with means and letters of significance were developed in GraphPad Prism version 10.6.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

5. Conclusions

Foliar application of ZnO NPs in C. arabica seedlings grown under acidic soil conditions triggered dose-dependent physiological and ionomic responses. Low to moderate doses (10–25 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) maintained intermediate stomatal conductance and net photosynthesis values and helped preserve ionomic balance, but did not significantly increase Ca, Fe, P, or K compared with the acidic soil. In contrast, the highest dose (100 mg L−1 ZnO NPs) significantly increased H2O2 levels. However, it did not alter MDA content, indicating a partial oxidative response without clear evidence of lipid peroxidation or structural membrane damage. Overall, our results indicate that 10–25 mg L−1 represents a physiologically safe range that can alleviate acidity-induced stress in Coffea arabica by supporting stable nutrient homeostasis and redox balance, whereas 50 mg L−1 behaves as a transitional dose with early oxidative and photosynthetic penalties. This highlights the potential of foliar ZnO NPs as a complementary nanofertilization strategy for coffee grown under acidic conditions, provided that dose thresholds are carefully controlled.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/stresses5040070/s1, Table S1: Effects of acidic soil and foliar ZnO NP application on photosynthetic pigments of Coffea arabica and Table S2: Physical and chemical properties of the soils used in the experiment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.-L.; methodology, J.B.M.-M. and E.H.; software, A.V.-L.; validation, A.V.-L., J.B.M.-M., and E.H.; formal analysis, A.V.-L.; investigation, A.V.-L.; resources, M.O.-C.; data curation, A.V.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.-L.; writing—review and editing, E.H.; visualization, A.V.-L., E.H., and M.O.-C.; supervision, E.H. and M.O.-C.; funding acquisition, M.O.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the project SNIP No. 352439/CUI No. 2314883, “Creación de los Servicios del Centro de Investigación, Innovación y Transferencia Tecnológica de Café—CEINCAFE”, executed by the Instituto de Investigación para el Desarrollo Sustentable de Ceja de Selva (INDES-CES) at the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza, Peru. In addition, we had the support of the Vice-Rectorate for Research of the Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza (UNTRM).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Laboratorio de Investigación de Suelos y Aguas (LABISAG) for their support in performing the elemental analysis of the samples. We also thank Jorge Alberto Condori Apfata for his valuable guidance in the operation and calibration of the LI-6800 system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ZnO NPs | Zinc oxide nanoparticles |

| Al3+ | Aluminum ion |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| To | Net photosynthetic rate |

| SPAD | Chlorophyll content index (SPAD units) |

| FW | Fresh weight |

| DW | Dry weight |

| PSII | Photosystem II |

| OEC | Oxygen-evolving complex |

| Pi | Inorganic phosphate |

| NR | Nitrate reductase |

| Nir | Nitrite reductase |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| GOGAT | Glutamate synthase |

| H+-ATPase | Proton-translocating ATPase |

| CBL–CIPK | Calcineurin B-like/CBL-interacting protein kinase |

| TBARS | Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| ZIP | Zinc-regulated transporter/Iron-regulated transporter-like protein |

| HMA | Heavy-metal ATPase |

| IRT | Iron-regulated transporter |

| NRAMP | Natural resistance-associated macrophage protein |

References

- Ovalle-Rivera, O.; Läderach, P.; Bunn, C.; Obersteiner, M.; Schroth, G. Projected Shifts in Coffea arabica Suitability among Major Global Producing Regions Due to Climate Change. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Coffee. Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://www.fao.org/markets-and-trade/commodities-overview/beverages/coffee/en (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Daily Coffee News Staff. Major ICO Green Coffee Report Notes “Growing Americas” and “Shrinking Rest of the World.” Daily Coffee News by Roast Magazine. 2023. Available online: https://dailycoffeenews.com/2023/12/05/major-ico-green-coffee-report-notes-growing-americas-and-shrinking-rest-of-the-world/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Nogueira, V. Recent Developments and Prospects in the Coffee Value Chain; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/vanusia-nogueira_myem2024.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Yang, Z.-B.; Rao, I.M.; Horst, W.J. Interaction of aluminium and drought stress on root growth and crop yield on acid soils. Plant Soil 2013, 372, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, K.; Hermoza, N.; Mejia, S.; Romero-Chavez, L.E.; Ottos, E.; Arce, A.; Solórzano Acosta, R. Spatial Analysis of Soil Acidity and Available Phosphorus in Coffee-Growing Areas of Pichanaqui: Implications for Liming and Site-Specific Fertilization. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoe, R.; Thomas, R.H.; Asiedu, S.K.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Fofana, B.; Abbey, L. Aluminum in plant: Benefits, toxicity and tolerance mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1085998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Quintal, E.; Escalante-Magaña, C.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Martínez-Estévez, M. Aluminum, a Friend or Foe of Higher Plants in Acid Soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojórquez-Quintal, J.E.D.A.; Sánchez-Cach, L.A.; Ku-González, Á.; de los Santos-Briones, C.; de Fátima Medina-Lara, M.; Echevarría-Machado, I.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.A.; Teresa Hernández Sotomayor, S.M.; Estévez, M.M. Differential effects of aluminum on in vitro primary root growth, nutrient content and phospholipase C activity in coffee seedlings (Coffea arabica). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 134, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poot-Poot, W.; Rodas-Junco, B.A.; Muñoz-Sánchez, J.A.; Hernández-Sotomayor, S.M.T. Protoplasts: A friendly tool to study aluminum toxicity and coffee cell viability. SpringerPlus 2016, 5, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, M.C.L.; Martinez, H.E.P.; Pereira, P.R.G.; Sampaio, N.F.; Silva, E.a.M. Aluminum tolerance of coffee genotypes in nutrient solution. I. Root and shoot growth and development. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 1998, 22, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Rincón, C.I.; Alarcón Gutiérrez, E.; García Pérez, J.A.; Sánchez-Velásquez, L.R.; Iglesias Andreu, L.G. La variedad de café Geisha y su estatus en el mundo y en México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauduin, S.; Latini, M.; Belleggia, I.; Migliore, M.; Biancucci, M.; Mattioli, R.; Francioso, A.; Mosca, L.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Interplay between Proline Metabolism and ROS in the Fine Tuning of Root-Meristem Size in Arabidopsis. Plants 2022, 11, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Boras, S.; Tjoa, A.; Watanabe, T.; Jansen, S. Aluminium Accumulation and Intra-Tree Distribution Patterns in Three Arbor aluminosa (Symplocos) Species from Central Sulawesi. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149078. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hu, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Dou, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, X. Growth and physiology effects of seed priming and foliar application of ZnO nanoparticles on Hibiscus syriacus L. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravishankar, L.V.; Puranik, N.; Lekkala, V.V.V.; Lomada, D.; Reddy, M.C.; Maurya, A.K. ZnO Nanoparticles: Advancing Agricultural Sustainability. Plants 2025, 14, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acidri, R.; Sawai, Y.; Sugimoto, Y.; Handa, T.; Sasagawa, D.; Masunaga, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Nishihara, E. Exogenous Kinetin Promotes the Nonenzymatic Antioxidant System and Photosynthetic Activity of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Plants Under Cold Stress Conditions. Plants 2020, 9, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxiselly, Y.; Anusornwanit, P.; Rugkong, A.; Chiarawipa, R.; Chanjula, P. Morpho-Physiological Traits, Phytochemical Composition, and Antioxidant Activity of Canephora Coffee Leaves at Various Stages. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2022, 13, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, S.B.; Ali, S.; Bernas, J.; Moudrý, J.; Konvalina, P.; Mushtaq, Z.; Murindangabo, Y.T.; Onyebuchi, E.F.; Baloch, F.B.; Ahmad, M.; et al. Wood ash application for crop production, amelioration of soil acidity and contaminated environments. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 141865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parecido, R.J.; Soratto, R.P.; Perdoná, M.J.; Gitari, H.I.; Dognani, V.; Santos, A.R.; Silveira, L. Liming Method and Rate Effects on Soil Acidity and Arabica Coffee Nutrition, Growth, and Yield. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2021, 21, 2613–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agegnehu, G.; Amede, T.; Erkossa, T.; Yirga, C.; Henry, C.; Tyler, R.; Nosworthy, M.G.; Beyene, S.; Sileshi, G.W. Extent and management of acid soils for sustainable crop production system in the tropical agroecosystems: A review. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B—Soil Plant Sci. 2021, 71, 852–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, L.; Fedenia, L.N.; Sharifan, H.; Ma, X.; Lombardini, L. Effects of foliar application of zinc sulfate and zinc nanoparticles in coffee (Coffea arabica L.) plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpal, V.R.; Nongthongbam, B.; Bhatia, M.; Singh, A.; Raina, S.N.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.D.; Zahra, N.; Husen, A. The nano-paradox: Addressing nanotoxicity for sustainable agriculture, circular economy and SDGs. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Mori, J.B.; Lapiz-Culqui, Y.K.; Huaman-Huaman, E.; Zuta-Puscan, M.; Oliva-Cruz, M. Can Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Alleviate the Adverse Effects of Salinity Stress in Coffea arabica? Agronomy 2025, 15, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Nascente, A.S. Chapter Six—Management of Soil Acidity of South American Soils for Sustainable Crop Production. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 221–275. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128021392000068 (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Melash, A.A.; Bytyqi, B.; Nyandi, M.S.; Vad, A.M.; Ábrahám, É.B. Chlorophyll Meter: A Precision Agricultural Decision-Making Tool for Nutrient Supply in Durum Wheat (Triticum turgidum L.) Cultivation under Drought Conditions. Life 2023, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Ahmad, A.; Alhammad, B.A.; Tola, E. Exogenous Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Improved Antioxidants, Photosynthetic, and Yield Traits in Salt-Stressed Maize. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.A.P.; Valdez-Aguilar, L.A.; Galindo, R.B.; Palomino, A.B.; Urbina, B.A.P. Morphology and Coating of ZnO Nanoparticles Affect Growth and Gas Exchange Parameters of Bell Pepper Seedlings. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzepiłko, A.; Prażak, R.; Święciło, A.; Gawroński, J. The Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on the Quantitative and Qualitative Traits of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi in In Vitro Culture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarin, K.; Usatov, A.; Minkina, T.; Duplii, N.; Kasyanova, A.; Fedorenko, A.; Khachumov, V.; Mandzhieva, S.; Rajput, V.D. Effects of bulk and nano-ZnO particles on functioning of photosynthetic apparatus in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M.A.; Dall’Osto, L.; Ruban, A.V. An In Vivo Quantitative Comparison of Photoprotection in Arabidopsis Xanthophyll Mutants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dau, H.; Grundmeier, A.; Loja, P.; Haumann, M. On the structure of the manganese complex of photosystem II: Extended-range EXAFS data and specific atomic-resolution models for four S-states. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, S.; Yusefi-Tanha, E.; Peralta-Videa, J.R. Interaction of nanoparticles and reactive oxygen species and their impact on macromolecules and plant production. Plant Nano Biol. 2024, 10, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksi, S.; Singh, K.M.; Rani, S.; Sharma, P. Melatonin-functionalized zinc oxide nanoparticles enhance salt stress tolerance in Vigna mungo L. by regulating antioxidants and ion homeostasis. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 5056–5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T.; Fedorenko, A.; Chernikova, N.; Hassan, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Sushkova, S.; Lysenko, V.; Soldatov, M.A.; Burachevskaya, M. Effects of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles on Physiological and Anatomical Indices in Spring Barley Tissues. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mi, K.; Yuan, X.; Chen, J.; Pu, J.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Foliar Application Effectively Enhanced Zinc and Aroma Content in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Grains. Rice 2023, 16, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Liu, Y.; Weng, Y.; Wang, H.; Bai, X. A critical review on the toxicity regulation and ecological risks of zinc oxide nanoparticles to plants. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; White, J.C.; Dhankher, O.P.; Xing, B. Metal-Based Nanotoxicity and Detoxification Pathways in Higher Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7109–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruttkay-Nedecky, B.; Krystofova, O.; Nejdl, L.; Adam, V. Nanoparticles based on essential metals and their phytotoxicity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: A Unified Mechanism in Plant Development and Stress Response? Plants 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spormann, S.; Nadais, P.; Sousa, F.; Pinto, M.; Martins, M.; Sousa, B.; Fidalgo, F.; Soares, C. Accumulation of Proline in Plants under Contaminated Soils—Are We on the Same Page? Antioxidants 2023, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Jurado, S.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Aguirre-Becerra, H.; Esquivel-Escalante, K.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A. Nanoparticles as Potential Eustressors in Plants. Agronomy 2025, 15, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, J.I.; Niño-Medina, G.; Olivares-Sáenz, E.; Lira-Saldivar, R.H.; Barriga-Castro, E.D.; Vázquez-Alvarado, R.; Rodríguez-Salinas, P.A.; Zavala-García, F. Foliar Application of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Zinc Sulfate Boosts the Content of Bioactive Compounds in Habanero Peppers. Plants 2019, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Ding, Z.; Fan, K. Zno nanoparticles: Improving photosynthesis, shoot development, and phyllosphere microbiome composition in tea plants. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, H.; Bai, J.; Cheng, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Geng, Y.; Shao, X. Impact of ZnO NPs on photosynthesis in rice leaves plants grown in saline-sodic soil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Bharati, R.; Kubes, J.; Popelkova, D.; Praus, L.; Yang, X.; Severova, L.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M. Zinc oxide nanoparticles application alleviates salinity stress by modulating plant growth, biochemical attributes and nutrient homeostasis in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1432258. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, H.S.; Othman, H.H.; Abdullah, R.; Edin, H.Y.A.S.; AL-Haj, N.A. Beneficial and toxicological aspects of zinc oxide nanoparticles in animals. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 8, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Liu, J.; Mao, T.; Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Zhai, Y. Nanobiotechnology-mediated regulation of reactive oxygen species homeostasis under heat and drought stress in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1418515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Geng, H.; Zhou, B.; Chen, H.; Yuan, R.; Ma, C.; Liu, R.; Xing, B.; Wang, F. The behavior, transport, and positive regulation mechanism of ZnO nanoparticles in a plant-soil-microbe environment. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120368. [Google Scholar]

- Salt, D.; Baxter, I.; Lahner, B. Ionomics and the Study of the Plant Ionome. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, O.; Hewedy, O.A.; Abdelmoteleb, A.; Ali, M.; Youssef, M.S.; Roumia, A.F.; Seymour, D.; Yuan, Z.-C. Nitrogen Journey in Plants: From Uptake to Metabolism, Stress Response, and Microbe Interaction. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-K.; Sandhu, J.; Bouain, N.; Prom-u-thai, C.; Rouached, H. Towards a Discovery of a Zinc-Dependent Phosphate Transport Road in Plants. Plants 2022, 11, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, I.; Hodgman, T.C.; Lu, C. An Integrative Systems Perspective on Plant Phosphate Research. Genes 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chérel, I.; Gaillard, I. The Complex Fine-Tuning of K+ Fluxes in Plants in Relation to Osmotic and Ionic Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabała, K.; Janicka, M. Structural and Functional Diversity of Two ATP-Driven Plant Proton Pumps. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtoh, H.; Baek, K.-H. Structural and Functional Insights into the Role of Guard Cell Ion Channels in Abiotic Stress-Induced Stomatal Closure. Plants 2021, 10, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabala, S. Regulation of Potassium Transport in Leaves: From Molecular to Tissue Level. Ann. Bot. 2003, 92, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. The oxygen-evolving complex: A super catalyst for life on earth, in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1824721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A.H.; Nayab, S.; Hussain, S.B.; Ali, M.; Pan, Z. Current Understandings on Magnesium Deficiency and Future Outlooks for Sustainable Agriculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos-Laita, L.; Takahashi, D.; Uemura, M.; Abadía, J.; López-Millán, A.F.; Rodríguez-Celma, J. Effects of Fe and Mn Deficiencies on the Root Protein Profiles of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Using Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis and Label-Free Shotgun Analyses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alejandro, S.; Höller, S.; Meier, B.; Peiter, E. Manganese in Plants: From Acquisition to Subcellular Allocation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Levengood, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, C. Plants Under Stress: Exploring Physiological and Molecular Responses to Nitrogen and Phosphorus Deficiency. Plants 2024, 13, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briat, J.-F.; Rouached, H.; Tissot, N.; Gaymard, F.; Dubos, C. Integration of P, S, Fe, and Zn nutrition signals in Arabidopsis thaliana: Potential involvement of PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE 1 (PHR1). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, T.; Liang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Yang, F. Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Applications in Enhancing Plant Stress Resistance: A Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E.; Liu, Y.; Gu, D.; Zhan, X.; Li, J.; Zhou, K.; Zhang, P.; Zou, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Copper: From Deficiency to Excess. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Babani, F. Contents of photosynthetic pigments and ratios of chlorophyll a/b and chlorophylls to carotenoids (a + b)/(x + c) in C4 plants as compared to C3 plants. Photosynthetica 2022, 60, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Potassium Control of Plant Functions: Ecological and Agricultural Implications. Plants 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustakas, M.; Dobrikova, A.; Sperdouli, I.; Hanć, A.; Moustaka, J.; Adamakis, I.-D.S.; Apostolova, E. Photosystem II Tolerance to Excess Zinc Exposure and High Light Stress in Salvia sclarea L. Agronomy 2024, 14, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ur Rehman, F.; Paker, N.P.; Khan, M.; Zainab, N.; Ali, N.; Munis, M.F.H.; Iftikhar, M.; Chaudhary, H.J. Assessment of application of ZnO nanoparticles on physiological profile, root architecture and antioxidant potential of Solanum lycopersicum. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 53, 102874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizan, M.; Hayat, S. Effect of foliar spray of ZnO-NPs on the physiological parameters and antioxidant systems of Lycopersicon esculentum. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2019, 34, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Calidad (INACAL). Laboratorio de Investigación en Suelo y Aguas-LABISAG-Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/es/i/2825857 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil. Circ. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1938, 347, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and Carotenoids: Measurement and Characterization by UV-VIS Spectroscopy. Curr. Protoc. Food Anal. Chem. 2001, 1, F4.3.1–F4.3.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: Protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zeng, B.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, C. Relationship Between Proline and Hg2+-Induced Oxidative Stress in a Tolerant Rice Mutant. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 56, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, R.L.; Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 1968, 125, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreto, F.; Velikova, V. Isoprene Produced by Leaves Protects the Photosynthetic Apparatus against Ozone Damage, Quenches Ozone Products, and Reduces Lipid Peroxidation of Cellular Membranes. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R; Posit PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Henry, L.; Pedersen, T.L.; Takahashi, K.; Wilke, C.; Woo, K.; Yutani, H.; Dunnington, D.; van den Brand, T.; et al. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- de Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research. 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/agricolae/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Kassambara, A. Rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rstatix/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Ogle, D. FSAdata: Data to Support Fish Stock Assessment (‘FSA’) Package. 2023. Available online: https://cran.rstudio.com/web/packages/FSAdata/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Henry, L.; Posit Software, PBC. Purrr: Functional Programming Tools. 2025. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/purrr/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).