Exploring How Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Cancer via Oxidative Stress

Abstract

1. Introduction

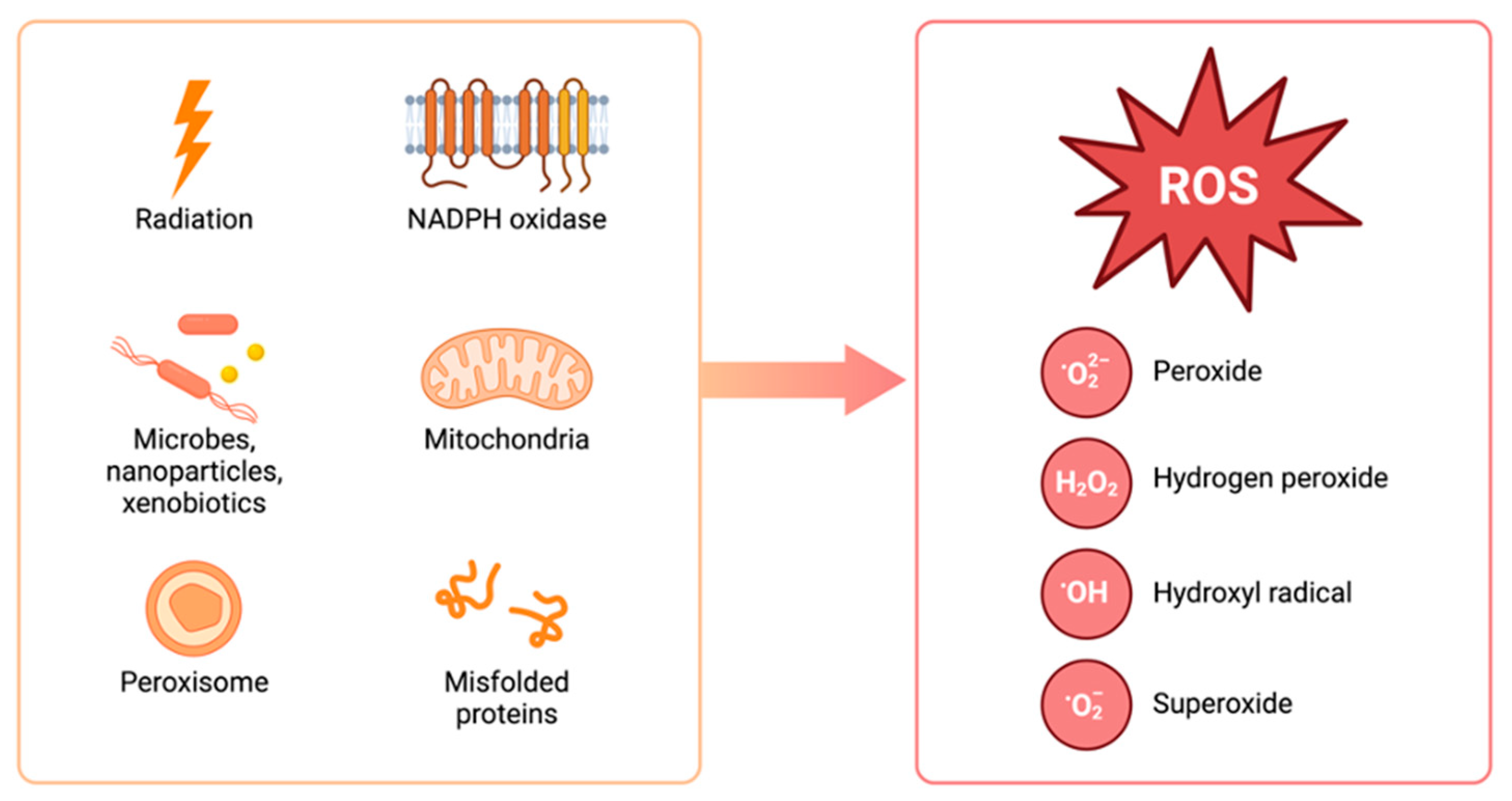

2. ROS and Carcinogenesis

2.1. Genetic Alterations and Genomic Instability

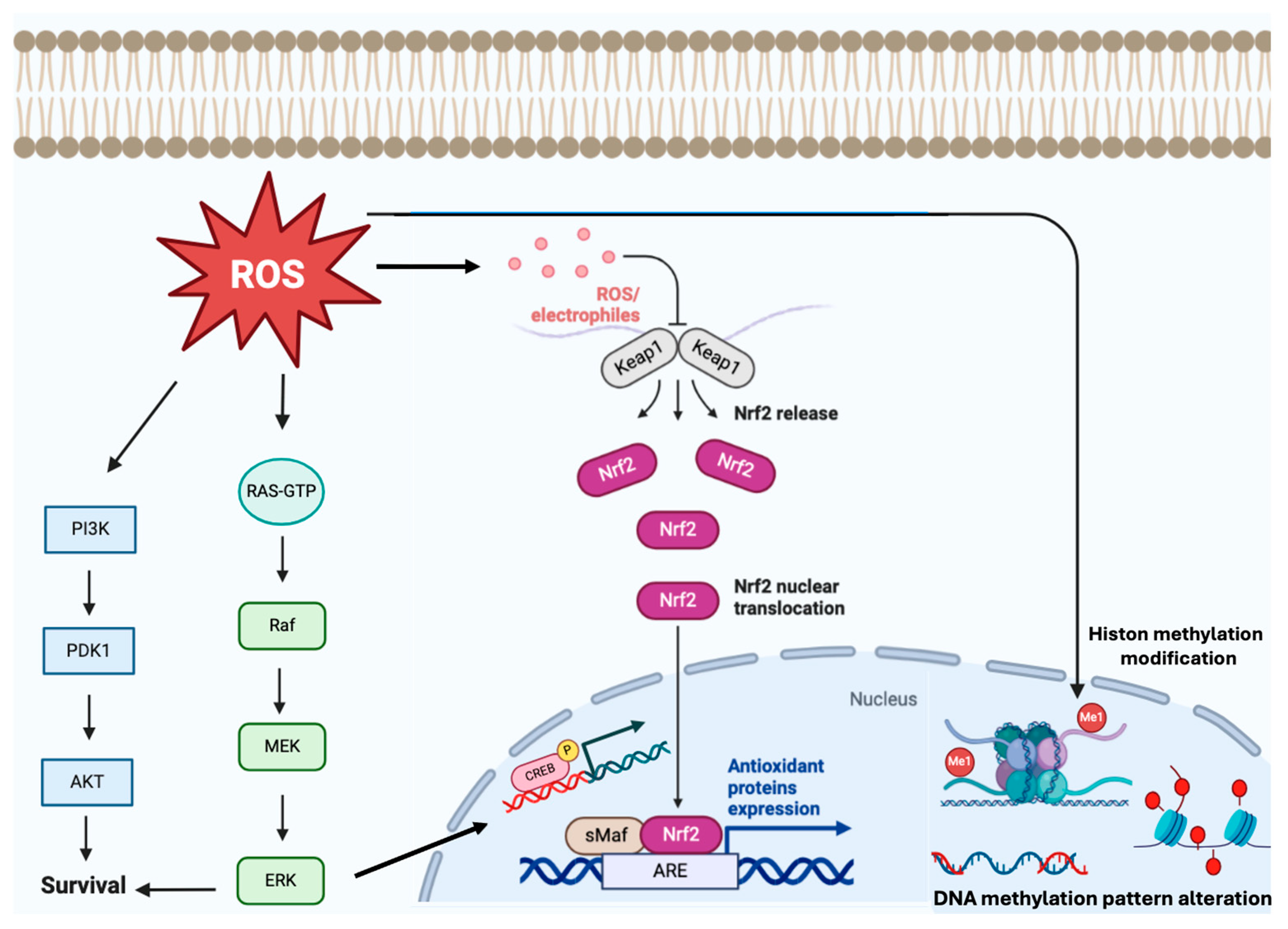

2.2. Epigenetic Alterations, Cell Proliferation and Signaling Pathways

2.3. Angiogenesis and Tumor Vascularization

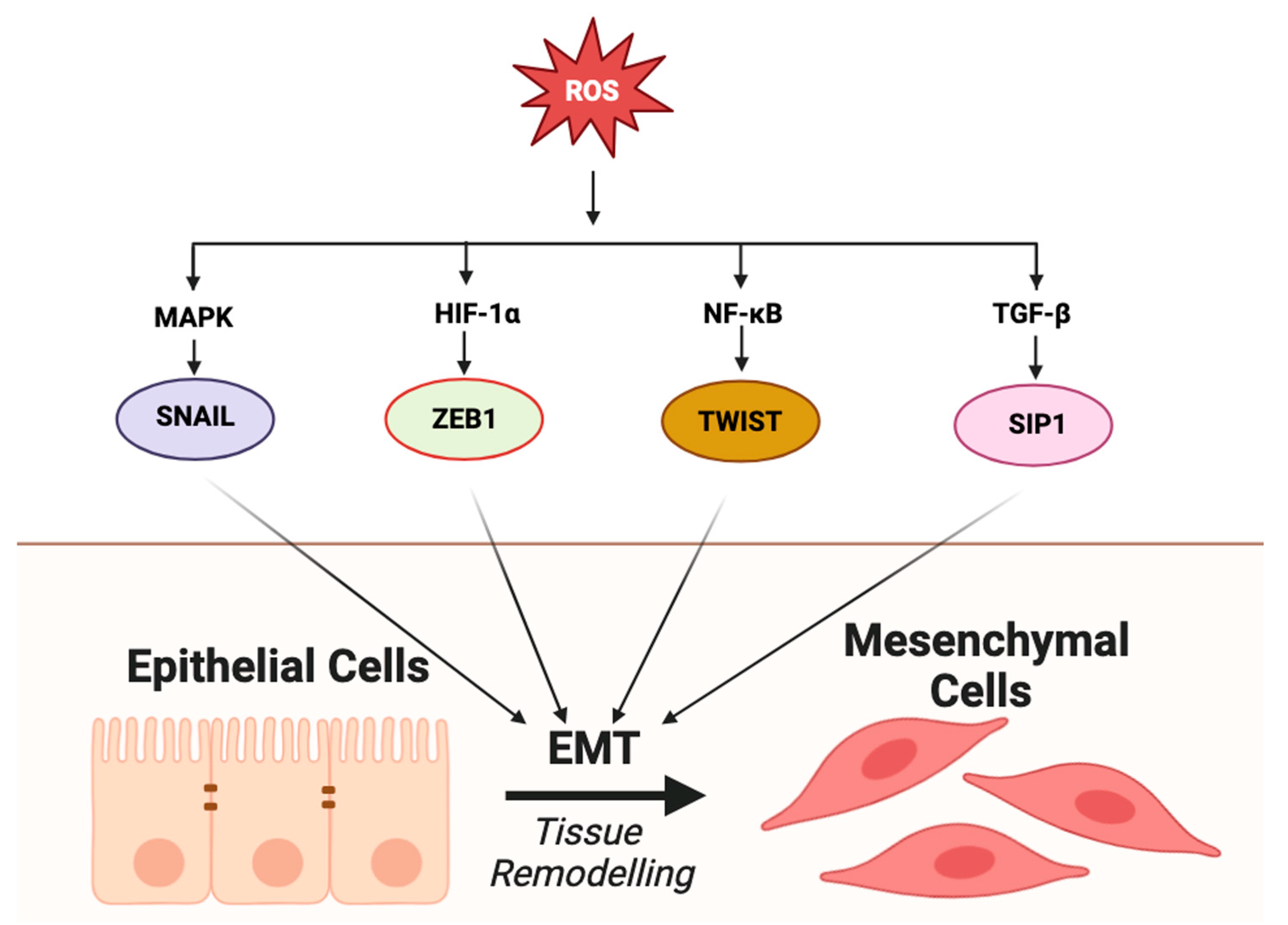

2.4. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) and Metastasis

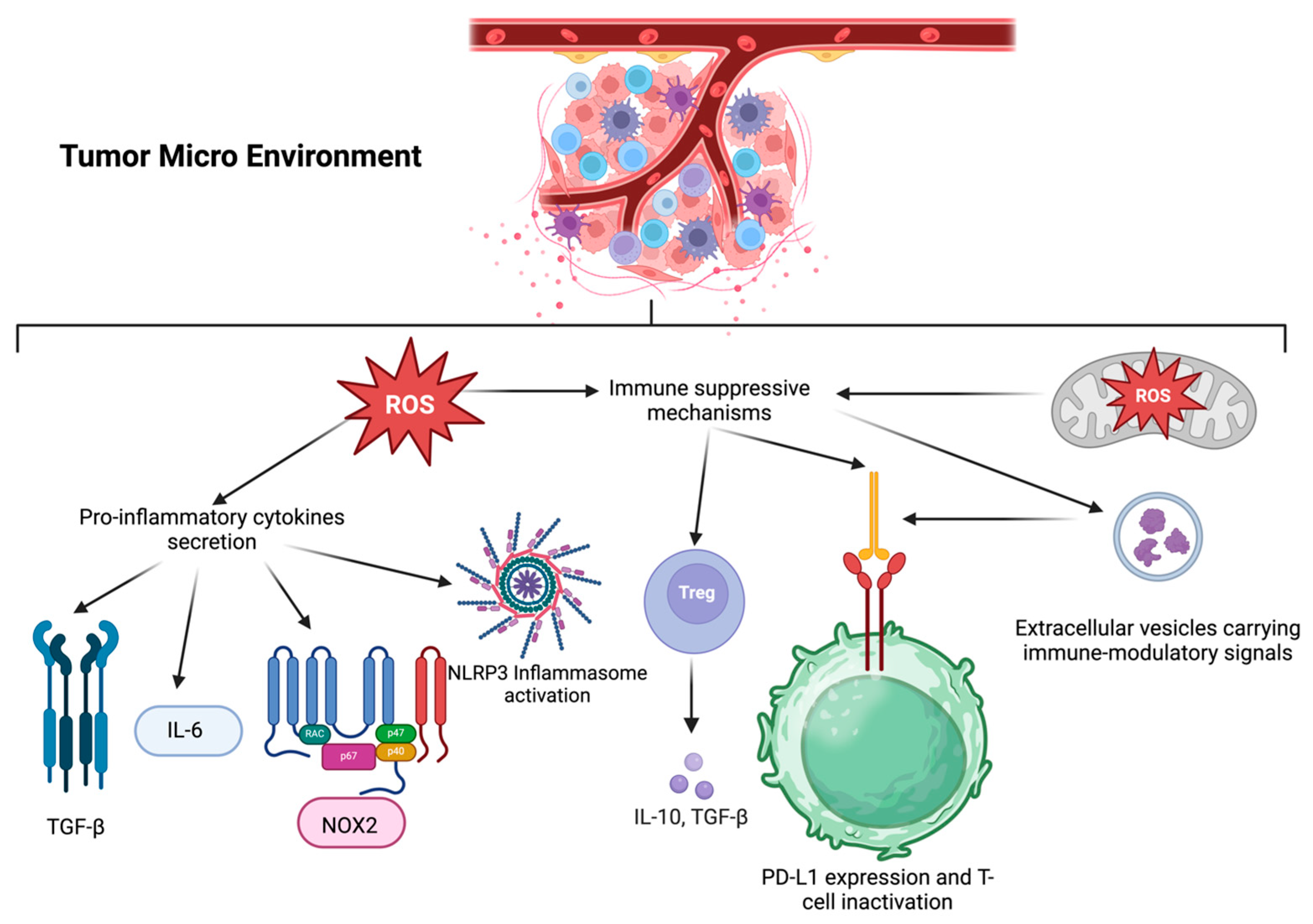

2.5. Tumor Microenvironment (TME) and Immune Response

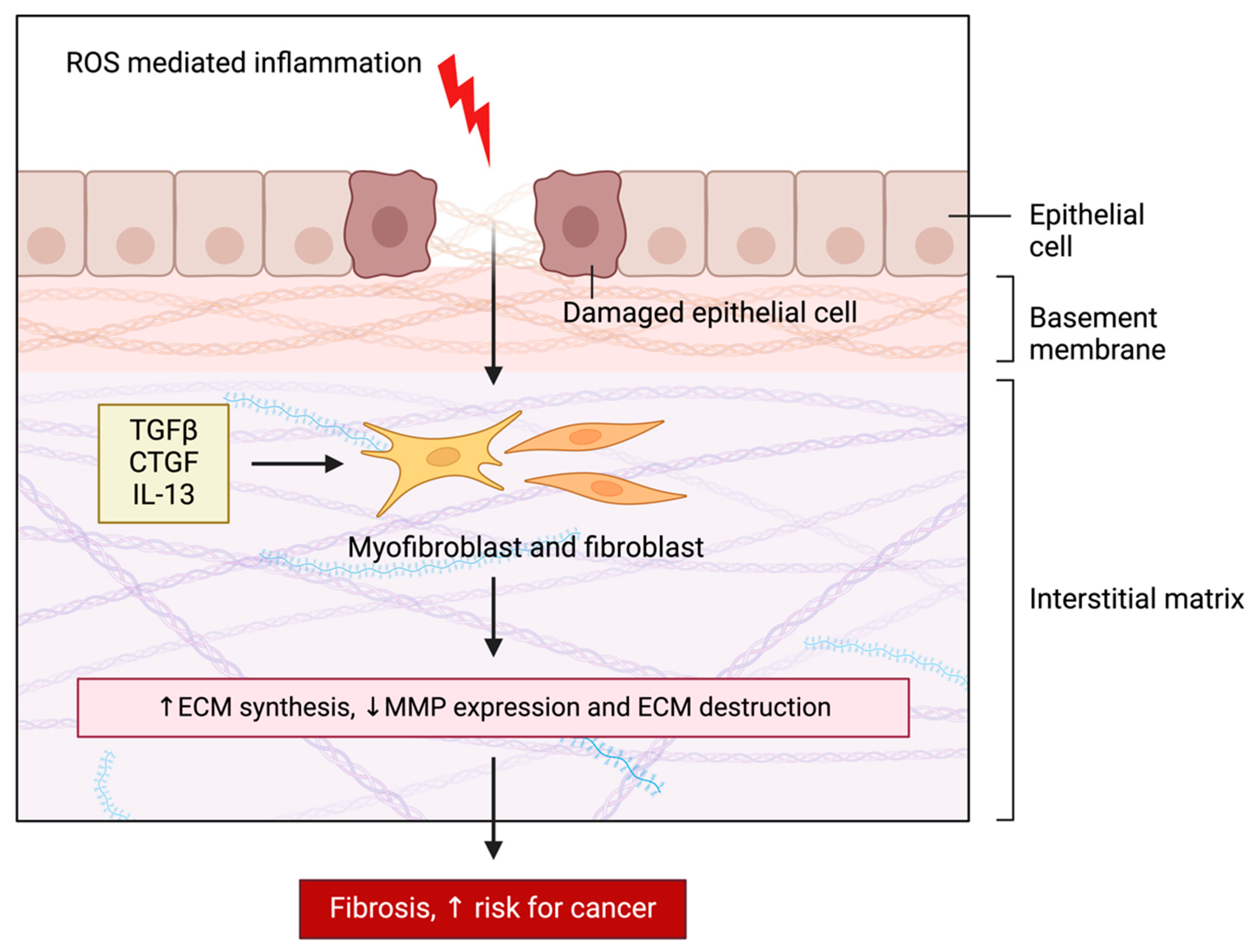

2.6. Remodeling of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM)

3. Therapeutic Targeting of ROS in Cancer

4. Metabolic Reprogramming and Redox Adaptation in Cancer

5. ROS in Specific Cancer Types

5.1. Neuroendocrine Tumors (NET)

5.2. Melanoma

5.3. Neuroblastoma

5.4. Leukemia

5.5. Breast Cancer

5.6. Lung Cancer

5.7. Colorectal Cancer

5.8. Hepatocellular Carcinoma

5.9. Pancreatic Cancer

5.10. Ovarian Cancer

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hakobyan, A.; Meyenberg, M.; Vardazaryan, N.; Hancock, J.; Vulliard, L.; Loizou, J.I.; Menche, J. Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Interplay between Mutational Signatures and Cellular Signaling. iScience 2024, 27, 109873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reczek, C.R.; Chandel, N.S. The Two Faces of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol. 2017, 1, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardaweel, S.K.; Gul, M.; Alzweiri, M.; Ishaqat, A.; ALSalamat, H.A.; Bashatwah, R.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: The Dual Role in Physiological and Pathological Conditions of the Human Body. Eurasian J. Med. 2018, 50, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayani, Z.; Matinahmadi, A.; Tavakolpournegari, A.; Bidooki, S.H. Exploring Stressors: Impact on Cellular Organelles and Implications for Cellular Functions. Stresses 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T. Signal Transduction by Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 194, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, L.A.; Chandel, N.S. Physiological Roles of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Mol. Cell 2012, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D. The Sites and Topology of Mitochondrial Superoxide Production. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrader, M.; Fahimi, H. Peroxisomes and Oxidative Stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2006, 1763, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.D.; Kaufman, R.J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress: A Vicious Cycle or a Double-Edged Sword? Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2007, 9, 2277–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, E.I.; Jay-Gerin, J.-P.; Pain, D. Ionizing Radiation-Induced Metabolic Oxidative Stress and Prolonged Cell Injury. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species. J. Physiol. 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.R.; Yang, S. Hydrogen Peroxide: A Signaling Messenger. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, A.; Muñoz, M.F.; Argüelles, S. Lipid Peroxidation: Production, Metabolism, and Signaling Mechanisms of Malondialdehyde and 4-Hydroxy-2-Nonenal. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Navarro, M.A.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Osada, J. Endoplasmic Reticulum Protein TXNDC5 Interacts with PRDX6 and HSPA9 to Regulate Glutathione Metabolism and Lipid Peroxidation in the Hepatic AML12 Cell Line. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilby, P.R. Singlet Oxygen: There Is Indeed Something New under the Sun. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3181–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, M.; Forman, H.J. Redox Signaling and the MAP Kinase Pathways. BioFactors 2003, 17, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.-H. The NOX Family of ROS-Generating NADPH Oxidases: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Quero, J.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Marmol, I.; Lasheras, R.; Sebastian, V.; Arruebo, M.; Osada, J.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J. Squalene in Nanoparticles Improves Antiproliferative Effect on Human Colon Carcinoma Cells Through Apoptosis by Disturbances in Redox Balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgio, M.; Trinei, M.; Migliaccio, E.; Pelicci, P.G. Hydrogen Peroxide: A Metabolic by-Product or a Common Mediator of Ageing Signals? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Deng, Z.; Lei, C.; Ding, X.; Li, J.; Wang, C. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Tumorigenesis and Progression. Cells 2024, 13, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.-F.; Guerrero, J.; Regalado, R.; Zhou, J.; Notarte, K.; Lu, Y.-W.; Encarnacion, P.; Carles, C.; Octavo, E.; Limbaroc, D.; et al. Insights into Metabolic Reprogramming in Tumor Evolution and Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, K.R.; Tay, Y. The Yin-Yang Regulation of Reactive Oxygen Species and MicroRNAs in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.; Tuli, H.S.; Varol, A.; Thakral, F.; Yerer, M.B.; Sak, K.; Varol, M.; Jain, A.; Khan, M.A.; Sethi, G. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Progression: Molecular Mechanisms and Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolacci, C.; Andreani, C.; El-Gammal, Y.; Scaglioni, P.P. Lipid Metabolism Regulates Oxidative Stress and Ferroptosis in RAS-Driven Cancers: A Perspective on Cancer Progression and Therapy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 706650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Manna, P.P. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Progression and Its Role in Therapeutics. Explor. Med. 2022, 3, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kelly, T.K.; Jones, P.A. Epigenetics in Cancer. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakta-Guha, D.; Guha, G. Oxidative Stress in Orchestrating Genomic Instability-Associated Cancer Progression. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ray, B.K., Roychoudhury, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 841–857. ISBN 978-981-15-9411-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, R.; Suzuki, T.; Kobayakawa, A.; Kamiya, H. Action-at-a-Distance Mutations Induced by 8-Oxo-7,8-Dihydroguanine Are Dependent on APOBEC3. Mutagenesis 2024, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrikus, S.S.; Henry, C.; McDonald, J.P.; Hellmich, Y.; Wood, E.A.; Woodgate, R.; Cox, M.M.; van Oijen, A.M.; Ghodke, H.; Robinson, A. DNA Double-Strand Breaks Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species Promote DNA Polymerase IV Activity in Escherichia coli. Biorxiv 2019, 533422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Wagner, J.R. ROS-Induced DNA Damage as an Underlying Cause of Aging. Adv. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2020, 2, e200024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, F.; Ramnath, N.; Nagrath, D. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Tumor Microenvironment: An Overview. Cancers 2019, 11, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotsantis, P.; Petermann, E.; Boulton, S.J. Mechanisms of Oncogene-Induced Replication Stress: Jigsaw Falling into Place. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marei, H.E.; Althani, A.; Afifi, N.; Hasan, A.; Caceci, T.; Pozzoli, G.; Morrione, A.; Giordano, A.; Cenciarelli, C. P53 Signaling in Cancer Progression and Therapy. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, R.; Acevedo, L.A.; Marmorstein, R. The MEK/ERK Network as a Therapeutic Target in Human Cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Chen, H.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Luo, C.; Tang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Dual Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Application in Cancer Therapy. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 5543–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-H.; Connolly, J.; Shimasaki, N.; Mimura, K.; Kono, K.; Campana, D. A Chimeric Receptor with NKG2D Specificity Enhances Natural Killer Cell Activation and Killing of Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1777–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengjiao, J.; Zhaozhen, W.; Xiao, H.; Jiahui, Z.; Zihe, G.; Xiao, H.; Junfang, Q.; Chen, L.; Yue, W. The PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/ROS/EIF2B Pathway Promotes Breast Cancer Growth and Metastasis via Suppression of NK Cell Cytotoxicity and Tumor Cell Susceptibility. Cancer Biol. Med. 2019, 16, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.S.; Abidin, S.A.Z.; Farghadani, R.; Othman, I.; Naidu, R. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases and Their Signaling Pathways as Therapeutic Targets of Curcumin in Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 772510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, V.; Reiner, D.J.; Alan, J.K.; Mitchell, C.; Edwards, L.J.; Khazak, V.; Der, C.J.; Cox, A.D. Genetic and Functional Characterization of Putative Ras/Raf Interaction Inhibitors in C. Elegans and Mammalian Cells. J. Mol. Signal. 2010, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Chatterjee, J. ROS and Oncogenesis with Special Reference to EMT and Stemness. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 99, 151073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Zou, L. Hallmarks of DNA Replication Stress. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2298–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Ren, C.; Ouyang, Z.; Xu, J.; Xu, K.; Li, Y.; Guo, H.; Bai, X.; Tian, M.; Xu, X.; et al. Stratifying TAD Boundaries Pinpoints Focal Genomic Regions of Regulation, Damage, and Repair. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Kozlov, S.; Lavin, M.F.; Person, M.D.; Paull, T.T. ATM Activation by Oxidative Stress. Science 2010, 330, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levings, D.C.; Lacher, S.E.; Palacios-Moreno, J.; Slattery, M. Transcriptional Reprogramming by Oxidative Stress Occurs within a Predefined Chromatin Accessibility Landscape. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A.; Kosnacova, H.; Chovanec, M.; Jurkovicova, D. Mitochondrial Genetic and Epigenetic Regulations in Cancer: Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, M.; Zhang, J.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. Interplay Among Metabolism, Epigenetic Modifications, and Gene Expression in Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 793428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.-L.; Wong, J. Oxidative DNA Demethylation Mediated by Tet Enzymes. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2015, 2, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periyasamy, L.; Krishnan, A.; Palanichami, M.K.; Ramachandran, I.; Kumaran, R.I.; Behlen, J.; Stanley, J.A.; Muthusami, S. Reactive Oxygen Species: Induced Epigenetic Modification in the Expression Pattern of Oncogenic Proteins. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ed.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1357–1372. ISBN 978-981-16-5422-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R.; Xie, F.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Xi, S.; Huang, Z.; Rong, X. Cross Talk between Acetylation and Methylation Regulators Reveals Histone Modifier Expression Patterns Posing Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications on Patients with Colon Cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2022, 14, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongelli, A.; Mengozzi, A.; Geiger, M.; Gorica, E.; Mohammed, S.A.; Paneni, F.; Ruschitzka, F.; Costantino, S. Mitochondrial Epigenetics in Aging and Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1204483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, Q. Cross-Talk between Oxidative Stress and M6A RNA Methylation in Cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6545728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziech, D.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)––Induced Genetic and Epigenetic Alterations in Human Carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011, 711, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poungpairoj, P.; Whongsiri, P.; Suwannasin, S.; Khlaiphuengsin, A.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Boonla, C. Increased Oxidative Stress and RUNX3 Hypermethylation in Patients with Hepatitis B Virus-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) and Induction of RUNX3 Hypermethylation by Reactive Oxygen Species in HCC Cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 16, 5343–5348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhasarathy, A.; Kajita, M.; Wade, P.A. The Transcription Factor Snail Mediates Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transitions by Repression of Estrogen Receptor-α. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 2907–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.-C.; Klausen, C.; Leung, P.C.K. Hydrogen Peroxide Mediates EGF-Induced Down-Regulation of E-Cadherin Expression via P38 MAPK and Snail in Human Ovarian Cancer Cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.-O.; Gu, J.-M.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.-S.; Park, Y.N.; Park, C.K.; Cho, J.W.; Park, Y.M.; Jung, G. Epigenetic Changes Induced by Reactive Oxygen Species in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Methylation of the E-Cadherin Promoter. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 2128–2140.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, F.; Fazeli, Y.; Khuu, M.; Salcido, K.; Singh, S.; Benavente, C.A. Retinoblastoma Tumor Suppressor Protein Roles in Epigenetic Regulation. Cancers 2020, 12, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, V.H.; Huu, T.N.; Sah, D.K.; Choi, J.M.; Yoon, H.J.; Park, S.C.; Jung, Y.S.; Lee, S.-R. Redox Regulation of PTEN by Reactive Oxygen Species: Its Role in Physiological Processes. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Park, J.; Han, S.-J.; Yang, S.Y.; Yoon, H.J.; Park, I.; Woo, H.A.; Lee, S.-R. Redox Regulation of Tumor Suppressor PTEN in Cell Signaling. Redox Biol. 2020, 34, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Qin, S.; Li, L.; He, Z.; Li, B.; Nice, E.C.; Zhou, L.; Lei, Y. Epigenetic Remodeling under Oxidative Stress: Mechanisms Driving Tumor Metastasis. MedComm–Oncology 2024, 3, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Hevia, D.; Patchva, S.; Park, B.; Koh, W.; Aggarwal, B.B. Upsides and Downsides of Reactive Oxygen Species for Cancer: The Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species in Tumorigenesis, Prevention, and Therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1295–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, R.C.; Felipe, K.B.; Filho, D.W. Editorial: Oncogenic PI3KT/Akt/MTOR Pathway Alterations, ROS Homeostasis, Targeted Cancer Therapy and Drug Resistance. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1372376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, B.; Simon, M.C. Hypoxia Inducible Factors, Stem Cells, and Cancer. Cell 2007, 129, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, B.B.; Sievers, C.; Donohue, L.K.; Gillespie, S.M.; Flavahan, W.A.; Miller, T.E.; Venteicher, A.S.; Hebert, C.H.; Carey, C.D.; Rodig, S.J.; et al. Adaptive Chromatin Remodeling Drives Glioblastoma Stem Cell Plasticity and Drug Tolerance. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 233–246.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordani, M.; Butera, G.; Pacchiana, R.; Masetto, F.; Mullappilly, N.; Riganti, C.; Donadelli, M. Mutant P53-Associated Molecular Mechanisms of ROS Regulation in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmerman, D.M.; Remmers, T.L.; Hillenius, S.; Looijenga, L.H.J. Mechanisms of TP53 Pathway Inactivation in Embryonic and Somatic Cells—Relevance for Understanding (Germ Cell) Tumorigenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfin, S.; Jha, N.K.; Jha, S.K.; Kesari, K.K.; Ruokolainen, J.; Roychoudhury, S.; Rathi, B.; Kumar, D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cell Metabolism. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ippolito, L.; Giannoni, E.; Chiarugi, P.; Parri, M. Mitochondrial Redox Hubs as Promising Targets for Anticancer Therapy. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szanto, I. NADPH Oxidase 4 (NOX4) in Cancer: Linking Redox Signals to Oncogenic Metabolic Adaptation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosios, A.M.; Manning, B.D. Cancer Signaling Drives Cancer Metabolism: AKT and the Warburg Effect. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 4896–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; He, J.; Lian, S.; Zeng, Y.; He, S.; Xu, J.; Luo, L.; Yang, W.; Jiang, J. Targeting Metabolic–Redox Nexus to Regulate Drug Resistance: From Mechanism to Tumor Therapy. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarky, E.; Cantley, L.C. Diverting Glycolysis to Combat Oxidative Stress. In Innovative Medicine: Basic Research and Development; Nakao, K., Minato, N., Uemoto, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Mu, C.; Zheng, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, T. The Cancer Antioxidant Regulation System in Therapeutic Resistance. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Zhou, L.; Huang, Z.; Li, B.; Nice, E.C.; Xu, J.; Huang, C. Antioxidant Therapy in Cancer: Rationale and Progress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Li, D.; Ponnamperumage, T.N.F.; Peterson, A.K.; Pandey, J.; Fatima, K.; Brzezinski, J.; Jakusz, J.A.R.; Gao, H.; Koelsch, G.E.; et al. Generation of Hydrogen Peroxide in Cancer Cells: Advancing Therapeutic Approaches for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2024, 16, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icard, P.; Fournel, L.; Wu, Z.; Alifano, M.; Lincet, H. Interconnection Between Metabolism and Cell Cycle in Cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2019, 44, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Chua, D.; Tan, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Volatile Driver of Field Cancerization and Metastasis. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Lutsenko, S.V.; Terentiev, A.A. Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species–Induced Protein Modifications: Implication in Carcinogenesis and Anticancer Therapy. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 6040–6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushio-Fukai, M. Redox Signaling in Angiogenesis: Role of NADPH Oxidase. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 71, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyano, K.; Okamoto, S.; Yamauchi, A.; Kawai, C.; Kajikawa, M.; Kiyohara, T.; Tamura, M.; Taura, M.; Kuribayashi, F. The NADPH Oxidase NOX4 Promotes the Directed Migration of Endothelial Cells by Stabilizing Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 11877–11890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craige, S.M.; Chen, K.; Pei, Y.; Li, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, C.; Shibata, R.; Sato, K.; Walsh, K.; Keaney, J.J.F. NADPH Oxidase 4 Promotes Endothelial Angiogenesis Through Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Activation. Circulation 2011, 124, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Han, N.; Yin, T.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Liu, D.; Xie, C.; Zhang, M. Lentivirus-Mediated Nox4 ShRNA Invasion and Angiogenesis and Enhances Radiosensitivity in Human Glioblastoma. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 581732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, H.; Harris, A.L. Advances in Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Biology. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Huang, A.; Yang, Q.; Li, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. ROS Impairs Tumor Vasculature Normalization through an Endocytosis Effect of Caveolae on Extracellular SPARC. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J. Anti-Angiogenic Drugs: Involvement in Cutaneous Side Effects and Wound-Healing Complication. Adv. Wound Care 2014, 3, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, X.H.; Hu, J. Role of Pericytes in Angiogenesis: Focus on Cancer Angiogenesis and Anti-Angiogenic Therapy. Neoplasma 2016, 63, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, V.L.J.L. Vascular Galectins in Tumor Angiogenesis and Cancer Immunity. Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 46, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, O.; Biesiekierska, M.; Panthu, B.; Vialichka, V.; Pirola, L.; Balcerczyk, A. The Epigenetic Profile of Tumor Endothelial Cells. Effects of Combined Therapy with Antiangiogenic and Epigenetic Drugs on Cancer Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, L. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2011, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahzadi, R.; Valipour, B.; Fathi, E.; Pirmoradi, S.; Molavi, O.; Montazersaheb, S.; Sanaat, Z. Oxidative Stress Regulation and Related Metabolic Pathways in Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition of Breast Cancer Stem Cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2023, 14, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, E.; Wang, X.; Song, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. An Emerging Master Inducer and Regulator for Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Tumor Metastasis: Extracellular and Intracellular ATP and Its Molecular Functions and Therapeutic Potential. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H.; Nice, E.C.; Huang, C. Redox Regulation in Tumor Cell Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition: Molecular Basis and Therapeutic Strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konno, T.; Melo, E.P.; Chambers, J.E.; Avezov, E. Intracellular Sources of ROS/H2O2 in Health and Neurodegeneration: Spotlight on Endoplasmic Reticulum. Cells 2021, 10, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.-T.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Tang, F.-R.; Cai, W.-Q.; Sethi, G.; Xin, H.-W.; Ma, Z. Insights into Biological Role of LncRNAs in Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Cells 2019, 8, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karicheva, O.; Rodriguez-Vargas, J.M.; Wadier, N.; Martin-Hernandez, K.; Vauchelles, R.; Magroun, N.; Tissier, A.; Schreiber, V.; Dantzer, F. PARP3 Controls TGFβ and ROS Driven Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Stemness by Stimulating a TG2-Snail-E-Cadherin Axis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 64109–64123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitty, J.L.; Filipe, E.C.; Lucas, M.C.; Herrmann, D.; Cox, T.R.; Timpson, P. Recent Advances in Understanding the Complexities of Metastasis. F1000Research 2018, 7, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Nie, X.; Yao, W.; Klinghammer, K.; Sudhoff, H.; Kaufmann, A.M.; Albers, A.E. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Stem Cells of Head and Neck Squamous Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelella, N.S.; Brandle, C.; Kim, T.; Ding, Z.-C.; Zhou, G. Oxidative Stress in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Relevance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; An, M.; Luo, Y.; Chen, C.; Lin, T. Roles of Cancer-Associated Fibroblast Functional Heterogeneity in Shaping the Lymphatic Metastatic Landscape: New Insights and Therapeutic Strategies. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, C.; Tournier, C. Exploring the Function of the JNK (c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase) Signalling Pathway in Physiological and Pathological Processes to Design Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Z.; Yang, R.; Lee, E.; Cuddapah, S.; Choi, B.H.; Dai, W. Oxidative Stress Modulates Expression of Immune Checkpoint Genes via Activation of AhR Signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2022, 457, 116314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-L.; Babuharisankar, A.P.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lien, H.-W.; Lo, Y.K.; Chou, H.-Y.; Tangeda, V.; Cheng, L.-C.; Cheng, A.N.; Lee, A.Y.-L. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in the Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Immunoescape: Foe or Friend? J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, J.; Mukherjee, K.; Mandal, C. Siglecs Modulate Activities of Immune Cells Through Positive and Negative Regulation of ROS Generation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 758588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.-Y.; Lucavs, J.; Ballard, D.; Das, J.K.; Kumar, A.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, X.; Song, J. Metabolic Reprogramming and Reactive Oxygen Species in T Cell Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 652687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Xu, H. Multi-Faced Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species in Anti-Tumor T Cell Immune Responses and Combination Immunotherapy. Explor. Med. 2022, 3, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermot, A.; Petit-Härtlein, I.; Smith, S.M.E.; Fieschi, F. NADPH Oxidases (NOX): An Overview from Discovery, Molecular Mechanisms to Physiology and Pathology. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, E.; Astsaturov, I.; Cukierman, E.; DeNardo, D.G.; Egeblad, M.; Evans, R.M.; Fearon, D.; Greten, F.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Hunter, T.; et al. A Framework for Advancing Our Understanding of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, S.W. Immunotherapeutic Response in Tumors Is Affected by Microenvironmental ROS. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1799–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Tsai, M.-C.; Tu, W.; Yeh, H.-C.; Wang, S.-C.; Huang, S.-P.; Li, C.-Y. Role of the NLRP3 Inflammasome: Insights Into Cancer Hallmarks. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 610492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamarsheh, S.; Zeiser, R. NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Cancer: A Double-Edged Sword. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meitzler, J.L.; Antony, S.; Wu, Y.; Juhasz, A.; Liu, H.; Jiang, G.; Lu, J.; Roy, K.; Doroshow, J.H. NADPH Oxidases: A Perspective on Reactive Oxygen Species Production in Tumor Biology. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 2873–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitovic, D.; Corsini, E.; Kouretas, D.; Tsatsakis, A.; Tzanakakis, G. ROS-Major Mediators of Extracellular Matrix Remodeling during Tumor Progression. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 61, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkretsi, V.; Stylianopoulos, T. Cell Adhesion and Matrix Stiffness: Coordinating Cancer Cell Invasion and Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Subbaram, S.; Carrico, P.M.; Melendez, J.A. Redox-Control of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1: A Critical Link between Free Radicals, Matrix Remodeling and Degenerative Disease. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010, 174, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenkovic, I. Matrix Metalloproteinases in Tumor Invasion and Metastasis. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2000, 10, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.D.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Tew, K.D. Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2020, 38, 167–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, B.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Yang, J.; Yang, L.; Huang, C. Redox Signaling-Mediated Tumor Extracellular Matrix Remodeling: Pleiotropic Regulatory Mechanisms. Cell. Oncol. 2024, 47, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Vega, M.R.; Chapman, E.; Zhang, D.D. NRF2 and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Hu, Q.; Qin, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, B.; Yu, X.; Wang, W. The Relationship of Redox With Hallmarks of Cancer: The Importance of Homeostasis and Context. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 862743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faurobert, E.; Bouin, A.-P.; Albiges-Rizo, C. Microenvironment, Tumor Cell Plasticity, and Cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2015, 27, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, T.R.; Bird, D.; Baker, A.-M.; Barker, H.; Ho, M.W.-Y.; Lang, G.; Erler, J.T. LOX-Mediated Collagen Crosslinking Is Responsible for Fibrosis-Enhanced Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1721–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, W.H.; Ritzenthaler, J.D.; Roman, J. Lung Extracellular Matrix and Redox Regulation. Redox Biol. 2016, 8, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Dou, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Xiao, M. Extracellular Matrix Remodeling in Tumor Progression and Immune Escape: From Mechanisms to Treatments. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minciacchi, V.R.; Freeman, M.R.; Di Vizio, D. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: Exosomes, Microvesicles and the Emerging Role of Large Oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, R.; Singh, A.; Pandey, A.; Mishra, K.P. Reactive Oxygen Species as Mediator of Tumor Radiosensitivity. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2014, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasauer, A.; Chandel, N.S. Targeting Antioxidants for Cancer Therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014, 92, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovic, L.; Zarkovic, N.; Saso, L. Controversy about Pharmacological Modulation of Nrf2 for Cancer Therapy. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, J.; Alconchel, A.; Ortega, S.; Bidooki, S.H.; Gimeno, M.C.; Rodriguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Cerrada, E. N-Heterocyclic Carbene Gold (I) Derivatives with Long Aliphatic Side Chains as Potential Anticancer Agents in Colon Cancer. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2025, 272, 112987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polimeni, M.; Gazzano, E. Is Redox Signaling a Feasible Target for Overcoming Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy? Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Zhang, B.; Fan, Y.; Lin, N. Keap1–Nrf2 Pathway: A Promising Target towards Lung Cancer Prevention and Therapeutics. Chronic Dis. Transl. Med. 2015, 1, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.; Kumar, S.; Varinli, H.; Han, Z.J.; Rider, A.E.; Evans, M.D.M.; Murphy, A.B.; Ostrikov, K. Atmospheric Gas Plasma-Induced ROS Production Activates TNF-ASK1 Pathway for the Induction of Melanoma Cancer Cell Apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2014, 25, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, K.; Hecker, L.; Luckhardt, T.R.; Cheng, G.; Thannickal, V.J. NADPH Oxidases in Lung Health and Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 2838–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheresh, P.; Kim, S.-J.; Tulasiram, S.; Kamp, D.W. Oxidative Stress and Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, Z.N.; Aburawi, H.E.; Semlali, A.; Muhammad, K.; Iratni, R. Oxidative Stress Inducers in Cancer Therapy: Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Zhelev, Z.; Aoki, I.; Bakalova, R.; Higashi, T. Overproduction of Reactive Oxygen Species–Obligatory or Not for Induction of Apoptosis by Anticancer Drugs. Chin. J. Cancer Res. 2016, 28, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, S.K.; Challa, S.R. Phytochemicals as Pro-Oxidants in Cancer. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Therapeutic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-981-16-1247-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Song, M.-H.; Oh, J.-W.; Keum, Y.-S.; Saini, R.K. Pro-oxidant Actions of Carotenoids in Triggering Apoptosis of Cancer Cells: A Review of Emerging Evidence. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Mhatre, V.; Bhori, M.; Marar, T. Vitamins E and C Reduce Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Caused by Camptothecin–an in Vitro Study. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2013, 95, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinovkin, R.A.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Chernyak, B.V. Current Perspectives of Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidants in Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1048177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, K.I. Antioxidants and Cancer Therapy: Furthering the Debate. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2004, 3, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechifor, M.T.; Neagu, T.-M.; Manda, G. Reactive Oxygen Species, Cancer and Anti-Cancer Therapies. Curr. Chem. Biol. 2009, 3, 22–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, J.K. A Paradoxical Chemoresistance and Tumor Suppressive Role of Antioxidant in Solid Cancer Cells: A Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 209845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhuang, P.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, M.; Lun, Y. “Double-Edged Sword” Effect of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Tumor Development and Carcinogenesis. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Increased Oxidative Stress as a Selective Anticancer Therapy. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 294303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Feng, H.; Sundberg, B.; Yang, J.; Powers, J.; Christian, A.H.; Wilkinson, J.E.; Monnin, C.; Avizonis, D.; Thomas, C.J.; et al. Methionine Oxidation Activates Pyruvate Kinase M2 to Promote Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 3045–3060.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfeitas, R.; Uhlen, M.; Nielsen, J.; Mardinoglu, A. New Challenges to Study Heterogeneity in Cancer Redox Metabolism. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Huang, L.; Du, Y.; Gan, F.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y. Antioxidative Stress: Inhibiting Reactive Oxygen Species Production as a Cause of Radioresistance and Chemoresistance. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6620306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Luo, J.; Luan, S.; He, C.; Li, Z. Long Non-Coding RNAs Involved in Cancer Metabolic Reprogramming. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Takada, K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer: Current Findings and Future Directions. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zong, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, K.; Jiang, Z.; Nan, L.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Shan, T.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species and Targeted Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1616781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canon, J.; Rex, K.; Saiki, A.Y.; Mohr, C.; Cooke, K.; Bagal, D.; Gaida, K.; Holt, T.; Knutson, C.G.; Koppada, N.; et al. The Clinical KRAS(G12C) Inhibitor AMG 510 Drives Anti-Tumour Immunity. Nature 2019, 575, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, N.; Jiang, H.; Li, Q.; Xing, D. Reactive Oxygen Species in Anticancer Immunity: A Double-Edged Sword. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 784612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsafti, A.; Scarpa, M.; Castagliuolo, I.; Scarpa, M. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antitumor Immunity—From Surveillance to Evasion. Cancers 2020, 12, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.E.; Alizadeh, D.; Starr, R.; Weng, L.; Wagner, J.R.; Naranjo, A.; Ostberg, J.R.; Blanchard, M.S.; Kilpatrick, J.; Simpson, J.; et al. Regression of Glioblastoma after Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2561–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzner, R.G.; Mackall, C.L. Tumor Antigen Escape from Car T-Cell Therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, L. Combination Therapy: A Feasibility Strategy for CAR T Cell Therapy in the Treatment of Solid Tumors (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 2063–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Altered Metabolism in Cancer: Insights into Energy Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, M.; Tan, D. Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Innovations. Cell Stress Chaperones 2025, 30, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, J.J.; Medina, M.Á. Metabolic Reprogramming at the Edge of Redox: Connections Between Metabolic Reprogramming and Cancer Redox State. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapozzi, V.; Comuzzi, C.; Di Giorgio, E.; Xodo, L.E. KRAS and NRF2 Drive Metabolic Reprogramming in Pancreatic Cancer Cells: The Influence of Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1547582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiliro, C.; Firestein, B.L. Mechanisms of Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer Cells Supporting Enhanced Growth and Proliferation. Cells 2021, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Qin, S.; Zhou, L.; Gao, W.; Shen, Z. Metabolic Adaptation-Mediated Cancer Survival and Progression in Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasiou, D.; Poulogiannis, G.; Asara, J.M.; Boxer, M.B.; Jiang, J.-K.; Shen, M.; Bellinger, G.; Sasaki, A.T.; Locasale, J.W.; Auld, D.S.; et al. Inhibition of Pyruvate Kinase M2 by Reactive Oxygen Species Contributes to Cellular Antioxidant Responses. Science 2011, 334, 1278–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floberg, J.M.; Schwarz, J.K. Manipulation of Glucose and Hydroperoxide Metabolism to Improve Radiation Response. Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 29, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Wu, F.; Shen, X.; Qiu, C.; Zhang, T.; Hong, L.; Zheng, P.; Shao, R.; et al. Compensatory Combination of MTOR and TrxR Inhibitors to Cause Oxidative Stress and Regression of Tumors. Theranostics 2021, 11, 4335–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiebala, M.; Skalska, J.; Casulo, C.; Brookes, P.S.; Peterson, D.R.; Hilchey, S.P.; Dai, Y.; Grant, S.; Maggirwar, S.B.; Bernstein, S.H. Dual Targeting of the Thioredoxin and Glutathione Antioxidant Systems in Malignant B Cells: A Novel Synergistic Therapeutic Approach. Exp. Hematol. 2015, 43, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhakumari, A.; Love-Homan, L.; Fletcher, E.V.M.; Martin, S.M.; Parsons, A.D.; Spitz, D.R.; Knudson, C.M.; Simons, A.L. Susceptibility of Human Head and Neck Cancer Cells to Combined Inhibition of Glutathione and Thioredoxin Metabolism. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazzari, F.; Chow, S.; Cheung, M.; Barghout, S.H.; Schimmer, A.D.; Chang, Q.; Hedley, D. Combined Targeting of the Glutathione and Thioredoxin Antioxidant Systems in Pancreatic Cancer. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 1070–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Xu, I.M.; Chiu, D.K.; Leibold, J.; Tse, A.P.; Bao, M.H.; Yuen, V.W.; Chan, C.Y.; Lai, R.K.; Chin, D.W.; et al. Induction of Oxidative Stress Through Inhibition of Thioredoxin Reductase 1 Is an Effective Therapeutic Approach for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1768–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrend, L.; Henderson, G.; Zwacka, R.M. Reactive Oxygen Species in Oncogenic Transformation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2003, 31, 1441–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, A.; Fang, C.; Yuan, L.; Shao, A.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, D. Oxidative Stress in Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors: Affecting the Tumor Microenvironment and Becoming a New Target for Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumor Therapy. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 2744–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Kardymon, O.L.; Savvateeva, M.V.; Melnikova, N.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Dmitriev, A.A. ROS Generation and Antioxidant Defense Systems in Normal and Malignant Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2019, 6175804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yi, J. Cancer Cell Killing via ROS: To Increase or Decrease, That Is the Question. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 1875–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romo-González, M.; Ijurko, C.; Hernández-Hernández, Á. Reactive Oxygen Species and Metabolism in Leukemia: A Dangerous Liaison. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 889875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samimi, A.; Khodayar, M.J.; Alidadi, H.; Khodadi, E. The Dual Role of ROS in Hematological Malignancies: Stem Cell Protection and Cancer Cell Metastasis. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2020, 16, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Qia, C.; Erkan, M.; Kleeff, J.; Michalski, C.W. Overview on How Oncogenic Kras Promotes Pancreatic Carcinogenesis by Inducing Low Intracellular ROS Levels. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swati; Basak, P.; Mittal, B.R.; Shukla, J.; Chadha, V.D. Systemic Effects of 177Lu-DOTATATE Therapy to Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Tumors: Mechanistic Insights and Role of Exosome. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2025, 52, 4125–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.L.; Indra, A.K. Oxidative Stress in Melanoma: Beneficial Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Therapeutic Strategies. Cancers 2023, 15, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, F.; Schittek, B.; Busch, S.; Garbe, C.; Smalley, K.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Li, G.; Herlyn, M. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways Present Molecular Targets for the Effective Treatment of Advanced Melanoma. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 2986–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The Role of ROS in Tumour Development and Progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedusi, M.; Lee, H.; Lim, Y.; Valacchi, G. Oxidative State in Cutaneous Melanoma Progression: A Question of Balance. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuelli, M.; Sartini, D.; Molinelli, E.; Campagna, R.; Pozzi, V.; Salvolini, E.; Simonetti, O.; Campanati, A.; Offidani, A. The Double-Edged Sword of Oxidative Stress in Skin Damage and Melanoma: From Physiopathology to Therapeutical Approaches. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslanbaeva, L.R.; Santoro, M.M. Adaptive Redox Homeostasis in Cutaneous Melanoma. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.J.; Kabeer, A.; Abbas, Z.; Siddiqui, H.A.; Calina, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cho, W.C. Interplay of Oxidative Stress, Cellular Communication and Signaling Pathways in Cancer. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Paul, P.; Lee, S.; Craig, B.T.; Rellinger, E.J.; Qiao, J.; Gius, D.R.; Chung, D.H. Antioxidant Inhibition of Steady-State Reactive Oxygen Species and Cell Growth in Neuroblastoma. Surgery 2015, 158, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marengo, B.; Raffaghello, L.; Pistoia, V.; Cottalasso, D.; Pronzato, M.A.; Marinari, U.M.; Domenicotti, C. Reactive Oxygen Species: Biological Stimuli of Neuroblastoma Cell Response. Cancer Lett. 2005, 228, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliynyk, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, M.V.; Sainero-Alcolado, L.; Dzieran, J.; Zirath, H.; Gallart-Ayala, H.; Wheelock, C.E.; Johansson, H.J.; Nilsson, R.; Lehtiö, J.; et al. MYCN-Enhanced Oxidative and Glycolytic Metabolism Reveals Vulnerabilities for Targeting Neuroblastoma. iScience 2019, 21, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, K.V.; Cai, J.; Jacob, S.; Kurupi, R.; Fairchild, C.K.; Shende, M.; Coon, C.M.; Powell, K.M.; Belvin, B.R.; Hu, B.; et al. MYCN-Amplified Neuroblastoma Is Addicted to Iron and Vulnerable to Inhibition of the System Xc-/Glutathione Axis. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 1896–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Jiang, Y.; Lai, X.; Liu, S.; Sun, L.; Zhou, Z.-W. A Shortage of FTH Induces ROS and Sensitizes RAS-Proficient Neuroblastoma N2A Cells to Ferroptosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Cao, M.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Qi, J.; Huang, C.; Yan, C.; Liu, X.; Jiang, S.; et al. Inhibition of PINK1 Senses ROS Signaling to Facilitate Neuroblastoma Cell Pyroptosis. Autophagy 2025, 21, 2091–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epp, S.; Egan, D.; Poon, E.; Aziz, A.A.A.; Wynne, K.; Chesler, L.; Halasz, M.; Kolch, W. OXPHOS Targeting of Mycn-Amplified Neuroblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1613751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannan, A.; Germon, Z.P.; Chamberlain, J.; Sillar, J.R.; Nixon, B.; Dun, M.D. Reactive Oxygen Species in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Reducing Radicals to Refine Responses. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J.; Davies, S.; Darley, R.L.; Tonks, A. Reactive Oxygen Species Rewires Metabolic Activity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 632623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopleva, M.; Tabe, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Andreeff, M. Therapeutic Targeting of Microenvironmental Interactions in Leukemia: Mechanisms and Approaches. Drug Resist. Updat. 2009, 12, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faderl, S.; Keating, M.; Do, K.-A.; Liang, S.-Y.; Kantarjian, H.; O’Brien, S.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Manshouri, T.; Albitar, M. Expression Profile of 11 Proteins and Their Prognostic Significance in Patients with Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Leukemia 2002, 16, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCasce, A.S. BCL-2 Is an Effective Target in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Hematol. 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaweme, N.M.; Zhou, S.; Changwe, G.J.; Zhou, F. The Significant Role of Redox System in Myeloid Leukemia: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Applications. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.J.; Darley, R.L.; Tonks, A. Reactive Oxygen Species and Metabolic Re-Wiring in Acute Leukemias. In Acute Leukemias; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, C.; Mato, A.R. BCL-2 As a Therapeutic Target in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 15, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, J.; Tang, Y. Research Progress on the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Initiation, Development and Treatment of Breast Cancer. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2024, 188, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, R.; Surepalli, N.; Farran, B.; Malhotra, S.V.; Nagaraju, G.P. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Critical Roles in Breast Tumor Microenvironment. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 160, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. The Glycolytic Switch in Tumors: How Many Players Are Involved? J. Cancer 2017, 8, 3430–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N. Navigating Metabolism; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Woodbury, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, P.D.; Huang, B.-W.; Tsuji, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Homeostasis and Redox Regulation in Cellular Signaling. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oshi, M.; Gandhi, S.; Yan, L.; Tokumaru, Y.; Wu, R.; Yamada, A.; Matsuyama, R.; Endo, I.; Takabe, K. Abundance of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Is Associated with Tumor Aggressiveness, Immune Response, and Worse Survival in Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022, 194, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Guo, H.; Chen, X. Dissecting the Pleiotropic Roles of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Lung Cancer: From Carcinogenesis toward Therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 1566–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, M.-S.; Chang, J.-H.; Hung, W.-Y.; Yang, Y.-C.; Chien, M.-H. The Interplay of Reactive Oxygen Species and the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor in Tumor Progression and Drug Resistance. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Modulator of Response to Cancer Therapy in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma (NSCLC). In Oxidative Stress in Lung Diseases: Volume 2; Chakraborti, S., Parinandi, N.L., Ghosh, R., Ganguly, N.K., Chakraborti, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 363–383. ISBN 978-981-32-9366-3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.-W.; Zhu, Y.-C.; Ye, X.-Q.; Yin, M.-X.; Zhang, J.-X.; Du, K.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-H.; Hu, J. Lung Cancer with Concurrent EGFR Mutation and ROS1 Rearrangement: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. OncoTargets Ther. 2016, 9, 4301–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ma, J.; Hall, S.R.R.; Peng, R.-W.; Yang, H.; Yao, F. Battles against Aberrant KEAP1-NRF2 Signaling in Lung Cancer: Intertwined Metabolic and Immune Networks. Theranostics 2023, 13, 704–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.A.; De Souza, D.P.; Kersbergen, A.; Policheni, A.N.; Dayalan, S.; Tull, D.; Rathi, V.; Gray, D.H.; Ritchie, M.E.; McConville, M.J.; et al. Synergy between the KEAP1/NRF2 and PI3K Pathways Drives Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with an Altered Immune Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 935–943.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, C.; Liu, S.; Trachootham, D.; Huang, P. Targeting ROS in Cancer: Rationale and Strategies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ArulJothi, K.N.; Kumaran, K.; Senthil, S.; Nidhu, A.B.; Munaff, N.; Janitri, V.B.; Kirubakaran, R.; Singh, S.K.; Gupt, G.; Dua, K.; et al. Implications of Reactive Oxygen Species in Lung Cancer and Exploiting It for Therapeutic Interventions. Med. Oncol. 2022, 40, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Chang, H.; Li, H.; Wang, S. Induction of Reactive Oxygen Species: An Emerging Approach for Cancer Therapy. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Duan, T.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, M.; Han, X.; Xiang, Y.; Huang, X.; Lin, H.; et al. RSL3 Drives Ferroptosis Through GPX4 Inactivation and ROS Production in Colorectal Cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, Y.; Zamyatnin, A.A., Jr.; Werner, J.; Bazhin, A.V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Colorectal Cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 5119–5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachootham, D.; Khoonin, W. Disrupting Redox Stabilizer: A Novel Therapeutic Strategy for Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Commun. 2019, 39, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, H.; Ning, W.; Wu, X.; Xu, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Ivermectin Has New Application in Inhibiting Colorectal Cancer Cell Growth. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 717529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorolla, M.A.; Hidalgo, I.; Sorolla, A.; Montal, R.; Pallisé, O.; Salud, A.; Parisi, E. Microenvironmental Reactive Oxygen Species in Colorectal Cancer: Involved Processes and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers 2021, 13, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Domínguez, A.; Pastor, N.; Martínez-López, L.; Colón-Pérez, J.; Bermúdez, B.; Orta, M.L. The Role of DNA Damage Response in Dysbiosis-Induced Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamah, S.; Lobiuc, A.; Covasa, M. Antioxidant Role of Probiotics in Inflammation-Induced Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, M.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.-N. Reactive Oxygen Species in Colorectal Cancer Adjuvant Therapies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, T.; Selvaggi, F.; Cotellese, R.; Aceto, G.M. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Colorectal Cancer Initiation and Progression: Perspectives on Theranostic Approaches. Cancers 2025, 17, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, N.J.; Giri, R.; Begun, J.; Clark, D.; Proud, D.; He, Y.; Hooper, J.D.; Kryza, T. Reactive Oxygen Species as Mediators of Disease Progression and Therapeutic Response in Colorectal Cancer. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 186–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Serag, H.B. Epidemiology of Viral Hepatitis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012, 142, 1264–1273.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Hu, C.; Yao, M.; Han, G. Mechanism of Sorafenib Resistance Associated with Ferroptosis in HCC. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1207496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas, S.C.; Cogliati, B.; Willebrords, J.; Maes, M.; Colle, I.; van den Bossche, B.; De Oliveira, C.P.M.S.; Andraus, W.; Alves, V.A.F.; Leclercq, I.; et al. Experimental Models of Liver Fibrosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 1025–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Marco, J.; Bidooki, S.H.; Abuobeid, R.; Barranquero, C.; Herrero-Continente, T.; Arnal, C.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Lasheras, R.; Surra, J.C.; Navarro, M.A.; et al. Thioredoxin Domain Containing 5 Is Involved in the Hepatic Storage of Squalene into Lipid Droplets in a Sex-Specific Way. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2024, 124, 109503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuobeid, R.; Herrera-Marcos, L.V.; Arnal, C.; Bidooki, S.H.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Lasheras, R.; Surra, J.C.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Osada, J. Differentially Expressed Genes in Response to a Squalene-Supplemented Diet Are Accurate Discriminants of Porcine Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Navarro, M.A.; Fernandes, S.C.M.; Osada, J. Thioredoxin Domain Containing 5 (TXNDC5): Friend or Foe? Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 3134–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Barranquero, C.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Navarro, M.A.; Fernandes, S.C.M.; Osada, J. TXNDC5 Plays a Crucial Role in Regulating Endoplasmic Reticulum Activity through Different ER Stress Signaling Pathways in Hepatic Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Spitzer, L.; Petitpas, A.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Lasheras, R.; Pellerin, V.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Navarro, M.A.; Osada, J.; et al. Chitosan Nanoparticles, a Novel Drug Delivery System To Transfer Squalene for Hepatocyte Stress Protection. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 51379–51393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidooki, S.H.; Alejo, T.; Sánchez-Marco, J.; Martínez-Beamonte, R.; Abuobeid, R.; Burillo, J.C.; Lasheras, R.; Sebastian, V.; Rodríguez-Yoldi, M.J.; Arruebo, M.; et al. Squalene Loaded Nanoparticles Effectively Protect Hepatic AML12 Cell Lines against Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in a TXNDC5-Dependent Way. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, M.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, K.; Xu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Wan, D.; et al. GLUD1 Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via ROS-Mediated P38/JNK MAPK Pathway Activation and Mitochondrial Apoptosis. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Song, M.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate T Cell Immune Response in the Tumor Microenvironment. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1580967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, P.; Liao, S.; Duan, L.; Zhu, D.; Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Duan, Y. Selenoprotein P Inhibits Cell Proliferation and ROX Production in HCC Cells. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.H.; Guan, Y.J.; Qiu, Z.D.; Zhang, X.; Zi, L.L.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Y.C.; Wang, W.X. System Analysis of ROS-Related Genes in the Prognosis, Immune Infiltration, and Drug Sensitivity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6485871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Meng, Z.; Yu, F. The Involvement of ROS-Regulated Programmed Cell Death in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 197, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Tang, Y.; Li, L.; Tao, X. ROS in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: What We Know. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 744, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, N.; Storz, P. Targeting Reactive Oxygen Species in Development and Progression of Pancreatic Cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2017, 17, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Pauklin, S. ROS and TGFβ: From Pancreatic Tumour Growth to Metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, N.A.; Reyes-Castellanos, G.; Carrier, A. Targeting Redox Metabolism in Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; He, H. Pancreatic Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1296, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schneiderhan, W.; Diaz, F.; Fundel, M.; Zhou, S.; Siech, M.; Hasel, C.; Möller, P.; Gschwend, J.E.; Seufferlein, T.; Gress, T.; et al. Pancreatic Stellate Cells Are an Important Source of MMP-2 in Human Pancreatic Cancer and Accelerate Tumor Progression in a Murine Xenograft Model and CAM Assay. J. Cell Sci. 2007, 120, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, H.; Jiao, F.; Li, N.; Gao, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Quan, M. MST1 Suppresses Pancreatic Cancer Progression via ROS-Induced Pyroptosis. Mol. Cancer Res. 2019, 17, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ge, W.; Martínez-Jarquín, S.; He, Y.; Wu, R.; Stoffel, M.; Zenobi, R. Mass Spectrometry Reveals High Levels of Hydrogen Peroxide in Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202213703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieg, D.C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.-Z.; Jiang, B.-H. ROS and MiRNA Dysregulation in Ovarian Cancer Development, Angiogenesis and Therapeutic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.-H.; Uddin, H.; Jo, U.; Kim, B.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, H.S.; Song, Y.S. ROS Accumulation by PEITC Selectively Kills Ovarian Cancer Cells via UPR-Mediated Apoptosis. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.H.; Siraj, S.; Arshad, A.; Waheed, U.; Aldakheel, F.; Alduraywish, S.; Arshad, M. ROS-Modulated Therapeutic Approaches in Cancer Treatment. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 143, 1789–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Guo, E.; Zhou, B.; Shan, W.; Huang, J.; Weng, D.; Wu, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, S.; Zhang, W.; et al. A Reactive Oxygen Species Scoring System Predicts Cisplatin Sensitivity and Prognosis in Ovarian Cancer Patients. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Imanaka, S.; Shigetomi, H. Revisiting Therapeutic Strategies for Ovarian Cancer by Focusing on Redox Homeostasis (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.-N.; Xie, L.-Z.; Shen, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Fu, Y.; Liu, F.-Y.; Han, F.-J. Insights into the Role of Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Cancer. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8388258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshkovska, Y.; Abramov, A.; Mahira, S.; Thatikonda, S. Understanding the Impact of Oxidative Stress on Ovarian Cancer: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. Future Pharmacol. 2024, 4, 651–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajalakshmi, P.; Natarajan, T.G. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Cancer, and Their Clinical Implications. In Handbook of Oxidative Stress in Cancer: Mechanistic Aspects; Chakraborti, S., Ray, B.K., Roychoudhury, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-981-15-4501-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wang, P.; Huang, C.; Zhou, S. The Crosstalk between Reactive Oxygen Species and Noncoding RNAs: From Cancer Code to Drug Role. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Antony, S.; Meitzler, J.L.; Doroshow, J.H. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Chronic Inflammation-Associated Cancers. Cancer Lett. 2014, 345, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Fu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, P.; Hu, C.; Cheng, X. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2024, 21, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Hydrogen Peroxide as a Central Redox Signaling Molecule in Physiological Oxidative Stress: Oxidative Eustress. Redox Biol. 2017, 11, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis. Pathophysiology 2000, 7, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishehsari, F.; Mahdavinia, M.; Vacca, M.; Malekzadeh, R.; Mariani-Costantini, R. Epidemiological Transition of Colorectal Cancer in Developing Countries: Environmental Factors, Molecular Pathways, and Opportunities for Prevention. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6055–6072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Key Mechanisms/Findings | Pathways and Molecules Involved | Therapeutic Implications | Supporting Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core metabolic reprogramming | Cancer cells remodel metabolism to sustain proliferation, survival, and stress adaptation | Glycolysis, TCA cycle, OXPHOS, glutaminolysis, lipid metabolism | Supports growth in hypoxic and nutrient-limited microenvironments | [162] |

| ROS–metabolism interdependence | Altered metabolism increases ROS; ROS feed back to regulate metabolic enzymes | Mitochondrial ROS, NADPH oxidases | ROS act as signaling molecules rather than byproducts | [163] |

| ROS-driven metabolic shifts | Elevated ROS enhance glycolysis and divert glucose to PPP for NADPH generation | PPP activation, glutamine metabolism | Maintains redox buffering and prevents metabolic collapse | [164] |

| Oncogene-linked redox rewiring | Oncogenic signaling sustains ROS and metabolic flux | KRAS, NRF2 activation; increased PPP and glutamine use | Couples metabolic reprogramming to redox control | [165] |

| ROS-sensitive glycolytic regulation | Key enzymes inhibited by ROS, redirecting glucose metabolism | PKM2, GAPDH inhibition | Boosts NADPH and glutathione synthesis | [166] |

| Compensatory pathways | Upregulation when glycolysis is impaired | Glutaminolysis, lipolysis, TCA replenishment | Maintains ATP and antioxidant capacity | [167,168] |

| Dual antioxidant pathway targeting | Simultaneous inhibition of glutathione and thioredoxin systems induces tumor cell death | BSO (GSH depletion) + auranofin (TrxR inhibition) | Synergistic cytotoxicity in pancreatic, head-and-neck, and B-cell cancers | [169,170,171,172,173] |

| Metabolic–mTOR combination therapy | mTOR inhibitors cooperate with TrxR blockade to trigger oxidative stress and autophagy | Everolimus + auranofin | Suppresses tumor growth with minimal toxicity in xenograft models | [174,175] |

| Therapeutic mechanism summary | Cancer cells can be pushed beyond antioxidant capacity | Lethal ROS accumulation; stress signaling activation | Selective killing of redox-dependent tumors while sparing normal cells | [174,175] |

| Cancer Type | Role of ROS | Mechanisms | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroendocrine Tumors [175,176,177] | Drives tumorigenesis Therapeutic resistance Immune evasion | Enhanced proliferation Reduced apoptosis, Inflammation, Angiogenesis | Targeting ROS with pro-oxidants or antioxidants to modulate redox balance |

| Melanoma [183,184,185,188,259,260] | Promotes aggressive behavior Metastasis Resistance to therapies | Oxidative damage to DNA Activation of MAPK/ERK, PI3K/AKT pathways | Pro-oxidants to increase ROS for apoptosis; antioxidants to sensitize cells to therapies |

| Neuroblastoma [189,190,191,195] | Drives tumor progression EMT Metastasis (especially in hypoxic conditions) | Activation of oxidative phosphorylation mTORC1, MYCN pathways | ROS-targeting strategies to reduce proliferation and metastasis |

| Leukemia [196,197,198,199,200,203] | Modulates microenvironment Promotes drug resistance | Increased ROS linked to anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g., Bcl-2) Metabolic rewiring, DNA damage | Therapies targeting ROS profiles specific to leukemia subtypes |

| Gastrointestinal Malignancies [208,261,262,263,264] | Influences tumor-associated inflammation Immune evasion | Chronic inflammation via ROS-driven cytokine release | Anti-inflammatory agents targeting ROS-mediated pathways |

| Breast Cancer [204,205,206,207,208,265] | Contributes to tumor growth Metastasis Therapy resistance | Elevated ROS from mitochondrial dysfunction Promotion of genomic instability Influence on TME | Balancing ROS levels for targeted therapies to prevent progression and metastasis |

| Lung Cancer [210,211,212,213,214] | Drives initiation Progression Resistance | DNA damage from environmental ROS Activation of NF-kB and NRF2 pathways Promotion of EMT | Targeting oxidative damage pathways to reduce metastasis and chemoresistance |

| Colorectal Cancer [218,219,220,221,222,266] | Facilitates carcinogenesis Metastasis Immune evasion | ROS-induced DNA damage Pro-inflammatory cytokines Microbial dysbiosis | Targeting NOX enzymes and ROS-induced inflammatory pathways |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma [229,230,231,232,239,240,241] | Promotes tumor progression EMT Metastasis | ROS from chronic liver diseases Viral infections Metabolic dysfunction | Therapies to counteract ROS-driven genomic instability and immune suppression |

| Pancreatic Cancer [245,246,247,248,249,250] | Drives aggressive behavior and resistance | ROS from Kras mutations Stromal inflammation Fibrosis | Modulating ROS in tumor–stromal interactions to reduce chemoresistance |

| Ovarian Cancer [63,252,253,254,255] | Promotes tumorigenesis EMT Therapy resistance | Hypoxia-induced ROS production Activation of HIF-1α Antioxidant pathways | Targeting ROS production and antioxidant defenses for improved therapy outcomes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tavakolpournegari, A.; Moosavi, S.S.; Matinahmadi, A.; Zayani, Z.; Bidooki, S.H. Exploring How Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Cancer via Oxidative Stress. Stresses 2025, 5, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040069

Tavakolpournegari A, Moosavi SS, Matinahmadi A, Zayani Z, Bidooki SH. Exploring How Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Cancer via Oxidative Stress. Stresses. 2025; 5(4):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040069

Chicago/Turabian StyleTavakolpournegari, Alireza, Seyedeh Safoora Moosavi, Arash Matinahmadi, Zoofa Zayani, and Seyed Hesamoddin Bidooki. 2025. "Exploring How Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Cancer via Oxidative Stress" Stresses 5, no. 4: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040069

APA StyleTavakolpournegari, A., Moosavi, S. S., Matinahmadi, A., Zayani, Z., & Bidooki, S. H. (2025). Exploring How Reactive Oxygen Species Contribute to Cancer via Oxidative Stress. Stresses, 5(4), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/stresses5040069