Abstract

Corrosion of steel structures remains a persistent challenge in construction, particularly in coastal and industrial environments where chloride-induced degradation accelerates structural failure. This study presents an eco-friendly approach to improve the corrosion protection of the steel by incorporating Lawsonia inermis (henna) leaf extract into zinc–aluminum silicate coatings. The henna extract was added at varying concentrations (0–12 wt%) to evaluate its influence on structure, adhesion, and electrochemical performance of the coating. Physicochemical characterizations including FTIR, XRD, XRF, and SEM revealed that a 5 wt% addition optimized pigment dispersion, resulting in a denser and more homogeneous coating microstructure. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and potentiodynamic polarization tests after 35 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution demonstrated that this formulation achieved the highest impedance and polarization resistance, confirming enhanced corrosion resistance. The improvement was attributed to the dual action of the henna extract: (i) as a dispersant, promoting uniform Zn–Al pigment distribution and reducing porosity, and (ii) as a green corrosion inhibitor, forming an adsorbed protective film on the steel surface. This work highlights the potential of bio-derived additives to enhance the long-term durability of steel infrastructure and supports the development of sustainable protective materials for construction applications.

1. Introduction

Corrosion of structural steel remains a critical challenge in the construction and maintenance of modern infrastructure, particularly in marine and industrial environments where aggressive chloride exposure accelerates material degradation [1]. Among the protection methods, the application of protective coatings is considered the most practical and effective solution to minimize corrosion damage [2]. In this field, silicate-based inorganic zinc-rich (IOZ) coatings have long been recognized as the standard for long-term corrosion protection in harsh operating environments, such as marine environments and industrial atmospheres [3].

The primary protection mechanism of zinc-rich paints is based on galvanic protection, in which a high zinc powder content (>80 wt% in the dry film) provides sacrificial cathodic protection to the underlying steel substrate [4]. The protection mechanism is established by the following electrochemical reactions:

Anode: Zn → Zn2+ + 2e−

Cathode: O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH−

During curing, a dense and ceramic-like silicate network is simultaneously formed, imparting superior thermal stability and abrasion resistance [5]. Performance can be further improved by incorporating hybrid pigment systems. In particular, the inclusion of flake pigments such as zinc–aluminum (Zn–Al) enhances barrier effectiveness by generating a tortuous, ‘zigzag’ diffusion pathway that slows the penetration of corrosive species toward the steel substrate, thus providing a synergistic combination of barrier protection and galvanic protection [6,7].

Despite their proven effectiveness, the pursuit of greater durability and environmental compatibility continues to motivate the search for novel additives. One promising direction is the development of ‘green’ corrosion inhibitors derived from plant sources, driven by growing regulatory and environmental pressures to replace traditional toxic inhibitors such as hexavalent chromium compounds [8]. Plant extracts are naturally enriched with phytochemicals containing heteroatoms (N, O, S) and π-electron systems, which promote strong adsorption onto metal surfaces, enable the formation of protective molecular films, and suppress the electrochemical processes responsible for corrosion [9].

Among the various natural candidates, Lawsonia inermis extract is particularly attractive due to its abundance, low cost, and inherent non-toxicity [10,11]. Its primary active compound, lawsone (2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), is believed to be central to the inhibition mechanism, as it can form stable chelate complexes with metal cations (e.g., Fe2+) on the steel surface according to: Fe2+ + nL → [Fe(L)n]2+ [12]. The anticorrosion capability of henna extract has been confirmed in several studies, predominantly within organic polymer matrices. For instance, Khoshkhou et al. demonstrated that incorporating 3% henna extract into a TMSM–PMMA hybrid coating on low-carbon steel reduced the corrosion rate from 1.90 MPY to 0.02 MPY in 0.1 M HCl solution [13]. Similarly, for aluminum alloys, Wan Nik et al. reported that lawsone contributed to chemisorption and/or physisorption, leading to the formation of an insulating surface layer, achieving an inhibition efficiency of 88% at a henna concentration of 500 ppm in seawater [14]. In another study, Zulkifli et al. evaluated different loadings of henna leaf extract (HLE) in an acrylic coating and found that the formulation containing 0.2 wt/vol% HLE (AC2) delivered the best corrosion protection performance for 5083 aluminum alloy [15].

However, an overview of published works shows that existing studies mainly focus on the application of henna extract in organic polymer matrices (such as PMMA, epoxy, acrylic) or as an inhibitor in aqueous solutions. Its efficacy, compatibility, and mechanism when directly incorporated into a reactive inorganic coating matrix, such as potassium silicate, remains an area that has not been fully explored.

To contribute to filling this gap, our study systematically investigated the effect of L. inermis leaf extract as a functional additive in potassium silicate coatings formulated with a hybrid pigment system consisting of 50 wt% zinc spheres and 5 wt% Zn-Al flakes on carbon steel substrates. The effects of extract concentration on the physicochemical properties (FTIR), crystal structure (XRD), surface elemental composition distribution (XRF), microstructural morphology (SEM), adhesion, and especially the corrosion protection of the paint films were evaluated by electrochemical techniques such as Open Circuit Potential (OCP), Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), and Dynamic Potential Polarization. The main goal is to elucidate the resonant protection mechanism from the integration of green inhibitors into advanced inorganic composite coating systems, thereby expanding the scope of application in the development of high-performance and durable protective coatings.

2. Materials and Methods

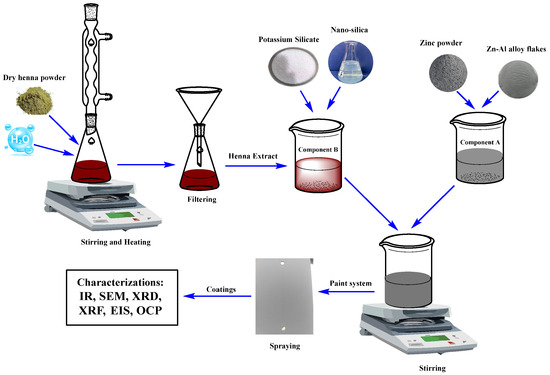

2.1. Overall Experimental Workflow and Flowchart

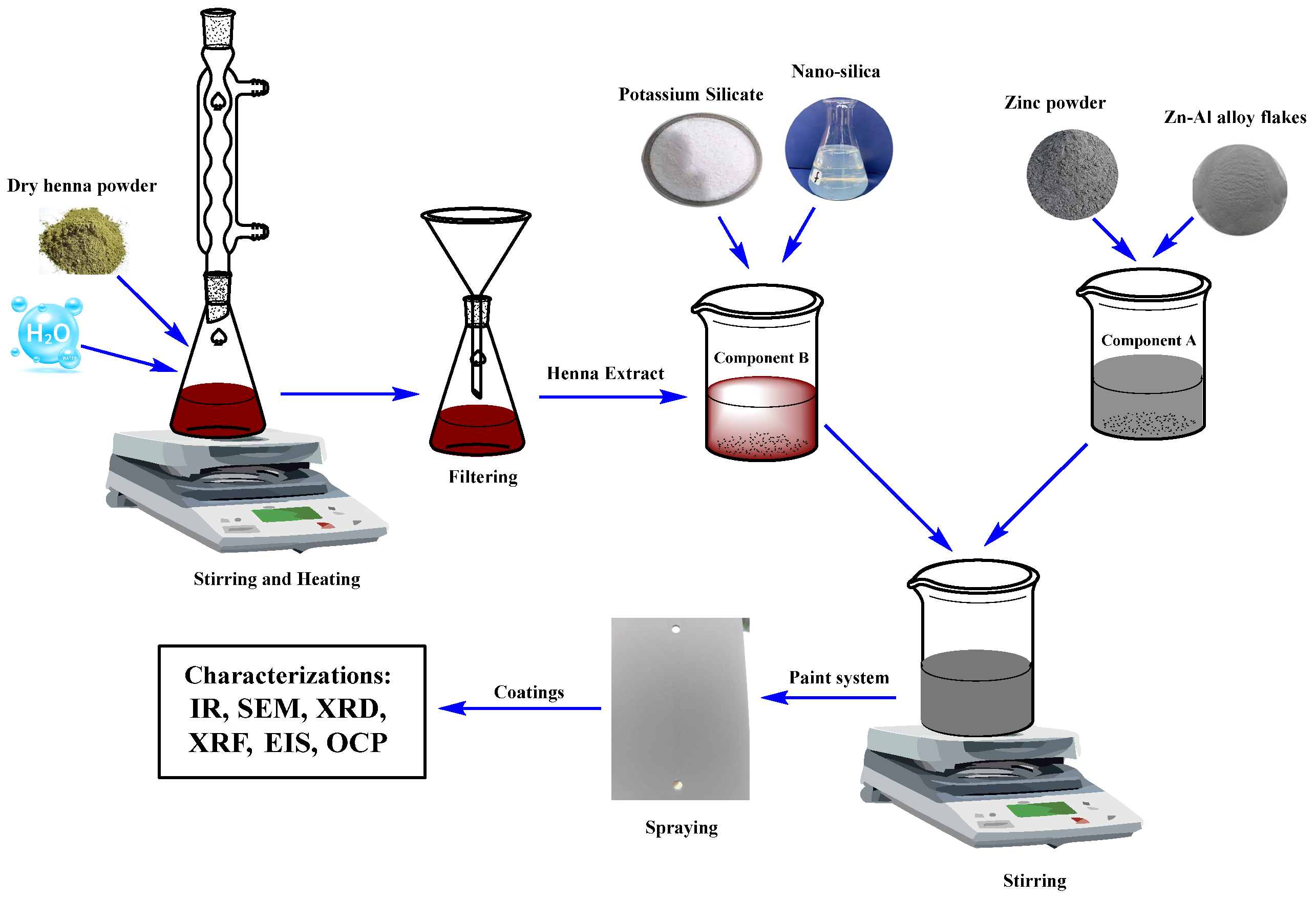

This study employed a two-component zinc-rich silicate coating system (Figure 1). Component A consisted of a solid blend of spherical zinc powder and zinc–aluminum alloy flakes, whereas Component B was a potassium silicate solution (K2O·nSiO2) that served as the inorganic binder. The experimental workflow comprised three main stages:

Figure 1.

Overall experimental flowchart of the study with three main stages.

- (1)

- Material Preparation:

L. inermis (henna) liquid extract was obtained by filtration. Separately, the Zn-Al pigments and silicate binder components were accurately weighed according to the coating formulation.

- (2)

- Paint Formulation and Sample Preparation:

The henna extract was incorporated into Component B at concentrations ranging from 0 to 12 wt%. The modified Component B was then mixed with Component A and applied onto pretreated CT3 steel substrates to produce the coating samples.

- (3)

- Analysis and Evaluation:

The cured coatings were characterized using FTIR, XRD, XRF, and SEM to assess structural and compositional features. Adhesion performance was measured, and electrochemical corrosion behavior was evaluated by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) following immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for specified periods.

2.2. Extract Preparation

Commercial henna powder (HNCO Organics Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, India) was dried at 105 °C for 60 min to remove moisture. Then, 50 g dry henna powder was dispersed in 500 mL of distilled water, boiled, and stirred for 30 min. The mixture was cooled and filtered through Whatman filter paper to collect the liquid extract.

The total polyphenol content in the extract was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm using an UV–VIS Spectrophotometer SP-UV1100 (DLAB Scientific Co. Ltd., Beijing, China). The polyphenol content in the extract was determined to be 1.03 ± 0.04 wt%, indicating that each 100 g of liquid extract contains 1.03 ± 0.04 g of polyphenols. The remaining mass is composed of the aqueous solvent and other co-extracted constituents, such as lawsone, tannins, and related phytochemicals. This liquid extract is used directly for mixing into component B of the paint system, which is the liquid component that acts as a film-forming agent. An aliquot of this liquid extract was concentrated to dryness using a rotary evaporator to obtain a dry henna extract powder, named Dried Aqueous Henna Extract (DAHE). This extract powder was used only for FTIR spectra of the pure inhibitor.

2.3. Coating Preparation

CT3 steel substrates (composition: 96.84% Fe; 0.10% C; 0.75% Al; 0.19% Si; 2.11% Cu) were abraded with sandpaper up to P1200 grit, ultrasonically degreased in methanol, rinsed with deionized water, and air-dried. Prior to coating, the cleaned substrates were treated with a Zr4+-based conversion layer to enhance adhesion and corrosion resistance.

The cleaned bare steel samples were immersed in the Zr-based conversion coating solution of hexafluorozirconic acid at a concentration of Zr4+ 50 ppm for 4 min at room temperature, then the pretreated samples were washed with distilled water and dried in hot air at 70 °C.

A two-component zinc-rich silicate coating was used, consisting of components A and B mixed at a mass ratio of 55:45 (w/w). Component A contained spherical zinc powder and Zn-Al alloy flakes blended at a 10:1 (w/w) ratio. The spherical zinc powder (purity ≥ 99.5%, particle size 5–7 μm; Zn:ZnO = 50.3:49.7 w/w) was supplied (Jotun PaintsHo Chi Minh City, Vietnam), while the Zn–Al alloy flakes (particle size 5–7 μm; Zn/Al = 80:20 w/w) were obtained (Hunan Jinhao New Material Technology Co., Ltd., Luxi, China).

Component B consisted of a potassium silicate solution (K2O·nSiO2), which forms a crosslinked Si–O–Si silicate network upon curing and provides the silica source required for film formation. Nanosilica particles (9–10 nm) were incorporated into this component to achieve a SiO2:K2O molar ratio of 5:1, selected to increase coating hardness and reduce surface defects.

For corrosion inhibitor modification, the prepared liquid extract was added to component B at concentrations of 0, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12 wt%. After thorough mixing, the resulting formulations were designated as H0, H3, H5, H8, H10, and H12, respectively.

The coating mixtures were mechanically stirred for 30 min and applied onto the steel substrates by spray-coating to achieve a dry film thickness of 100 ± 10 μm. All coated samples were allowed to cure under ambient laboratory conditions for at least 7 days before characterization and corrosion testing.

2.4. Characteristic Analysis Methods

To analyze the characteristics of the paint films, a variety of methods were used. The surface morphology was examined using a JMS-6510LV (Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) device after the samples were stabilized at room temperature, cut into 1 × 1 cm pieces, and coated with a layer of gold powder to support surface conductivity.

Chemical analysis was performed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) on a Nicoletis10 spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Madison, WI, USA). For this analysis, the henna extract was evaporated to dryness and placed on a sample holder with a diffuse reflectance measurement accessory.

The crystal phase structure (XRD) was determined using a D8-ADVANCE device (Bruker Corporation, Karlsruhe, Germany) after the paint samples had dried for 7 days. The measurements were performed using CuKα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA, recording diffraction patterns in the angle range of 4–80° (2θ) with a step size of 0.02° and a scanning time of 0.4 s/step.

The elemental composition was determined by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy using a VietSpace model XRF 5006-2020 on 5 × 5 cm samples at room temperature, with a wavelength range of 0.01 to 10 nm. Finally, the adhesion of the paint film was quantified by the pull-off test according to ASTM D4541.

Electrochemical studies were carried out using an Autolab PGSTAT 302N device (Metrohm Autolab B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands) with a three-electrode system, consisting of a platinum electrode (auxiliary), an Ag/AgCl electrode (reference), and a sample (working). Prior to EIS and polarization tests, the coated steel specimens were mounted using a cylindrical plastic tube of known diameter, into which a 3.5 wt% NaCl electrolyte was added. The temperature of the electrolyte was controlled at 25 ± 1 °C throughout all measurements. EIS was performed after an initial stabilization period of 1 day, and subsequently after 14 days and 35 days of immersion.

Potentiodynamic polarization measurements were conducted to investigate the corrosion current density (icorr) and corrosion potential (Ecorr). The potential was scanned at ±150 mV relative to the open circuit potential (OCP) at a scan rate of 0.01 V/s. The corrosion current density was collected by Tafel extrapolation at ± 50 mV around the OCP. EIS and polarization tests were conducted on the same specimens. Because polarization measurements are destructive, the polarization test was carried out only after completing the EIS measurement at the 35-day immersion time.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed over an area of 3.46 cm2 in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution at a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz, with an alternating potential amplitude of 10 mV.

Each sample was tested at least three times to ensure the repeatability of the measurements, and the obtained data were analyzed using Nova 2.1 software.

All primary quantitative results, including adhesion and total coating impedance, are presented as the mean values ± standard deviation SD, based on a minimum of three experimental repetitions for each sample to ensure the reliability and repeatability of the data. Qualitative and semi-quantitative analyses (XRD, XRF, SEM, FTIR) were performed three times on coating samples.

3. Results and Discussion

This study focused on evaluating the effectiveness of L. inermis extract as a green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel when incorporated into a water-based zinc-rich potassium silicate paint system. The physicochemical properties, surface morphology, and corrosion protection of paint films with different concentrations of the extract were systematically investigated. The addition of the extract is expected to improve the corrosion protection of the coating through a dual mechanism of action from the physical barrier of the paint system and the active inhibition of organic compounds contained in the extract. The results obtained will provide a basis for the development of environmentally friendly paint systems.

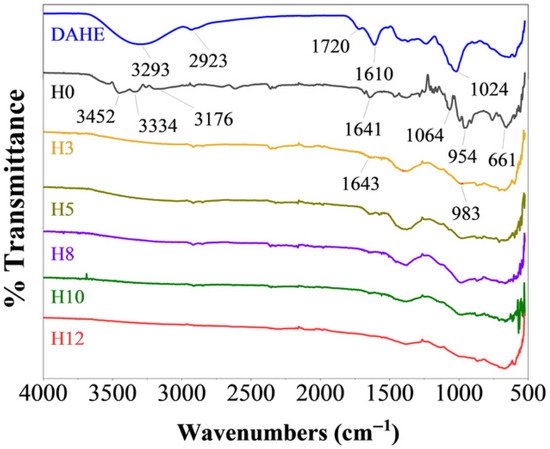

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Analysis (FTIR)

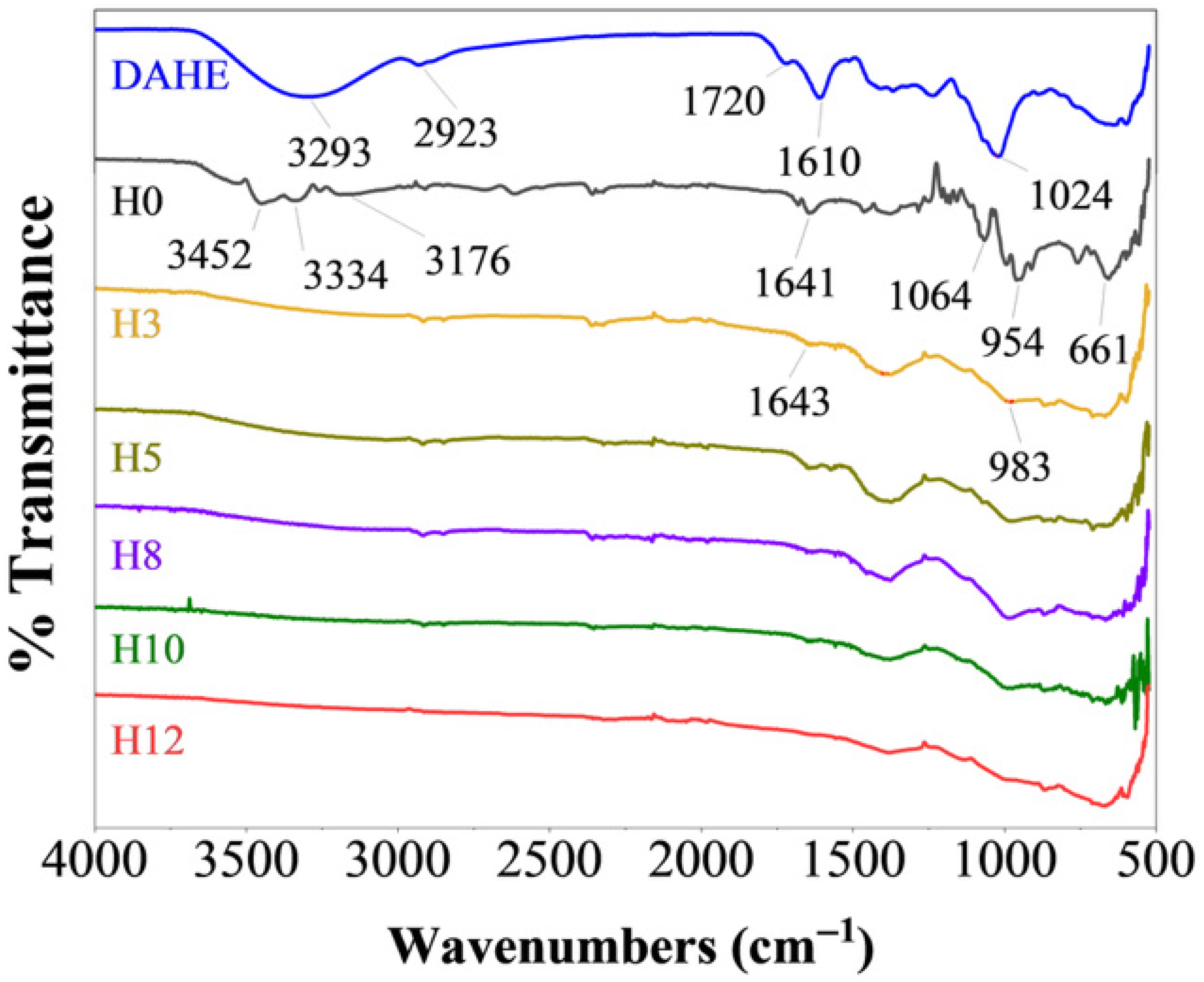

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to verify the presence of henna extract in the coating matrix and to examine its interaction with the silicate network, as shown in Figure 2. The spectrum of the dried L. inermis extract (DAHE powder) displayed characteristic absorption features typical of polyphenolic constituents. A broad band at 3293 cm−1 corresponded to the O–H stretching vibration, indicative of hydroxyl groups abundant in phenolic compounds [16]. The strong bands at 1720 cm−1 (C=O stretching) and 1610 cm−1 (aromatic C=C) were associated with key constituents such as lawsone and flavonoids [17]. Additional peaks at 2923 cm−1 (C–H stretching) and 1024 cm−1 (C–O stretching) further confirmed the complex organic matrix of the extract [18].

Figure 2.

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of DAHE powder and coating samples with different extract contents.

The FTIR spectrum of the unmodified coating (H0) exhibited typical features of potassium silicate-based inorganic films. A broad absorption band in the 3452–3176 cm−1 region, together with the peak at 1641 cm−1, corresponded to O–H stretching and bending vibrations, arising from silanol groups and physically adsorbed water molecules. The dominant absorption band between 1064–954 cm−1 was assigned to the asymmetric stretching of Si–O–Si linkages, representing the main structural framework (“backbone”) of the silicate network [19,20]. Additionally, the band observed at approximately 661 cm−1 was attributed to O–Si–O deformation vibrations, consistent with the formation of a condensed silicate matrix [21].

Distinct spectral changes were observed in the coatings containing henna extract compared with the control sample (H0). The FTIR spectra of H3, H5, H8, H10, and H12 exhibited broader and flatter absorption profiles across the entire wavenumber range, indicating the formation of a denser and more complex hydrogen-bonding network between polyphenolic constituents and the silicate matrix [22]. This enhanced hydrogen bonding suggests strong physicochemical interactions between the extract and the inorganic framework.

A further indication of these interactions is the shift of the main Si–O–Si asymmetric stretching band. In the extract-containing coatings, the band maximum moved to lower wavenumbers, centered around 983 cm−1. Such a red shift is commonly associated with modifications to the chemical environment of the siloxane network, consistent with coordination or hydrogen bonding between polyphenolic –OH groups and the Si–O–Si backbone.

Additionally, the appearance of a peak at approximately 1643 cm−1 provides further confirmation of the incorporation of organic constituents into the coating structure. This band corresponded to the bending vibration of –OH groups or the C=O stretching of polyphenolic compounds, demonstrating that the henna extract was successfully embedded within the silicate network of the cured film.

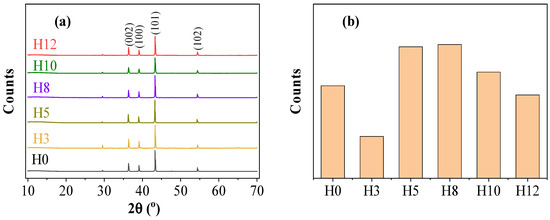

3.2. Crystal Structure Analysis by X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

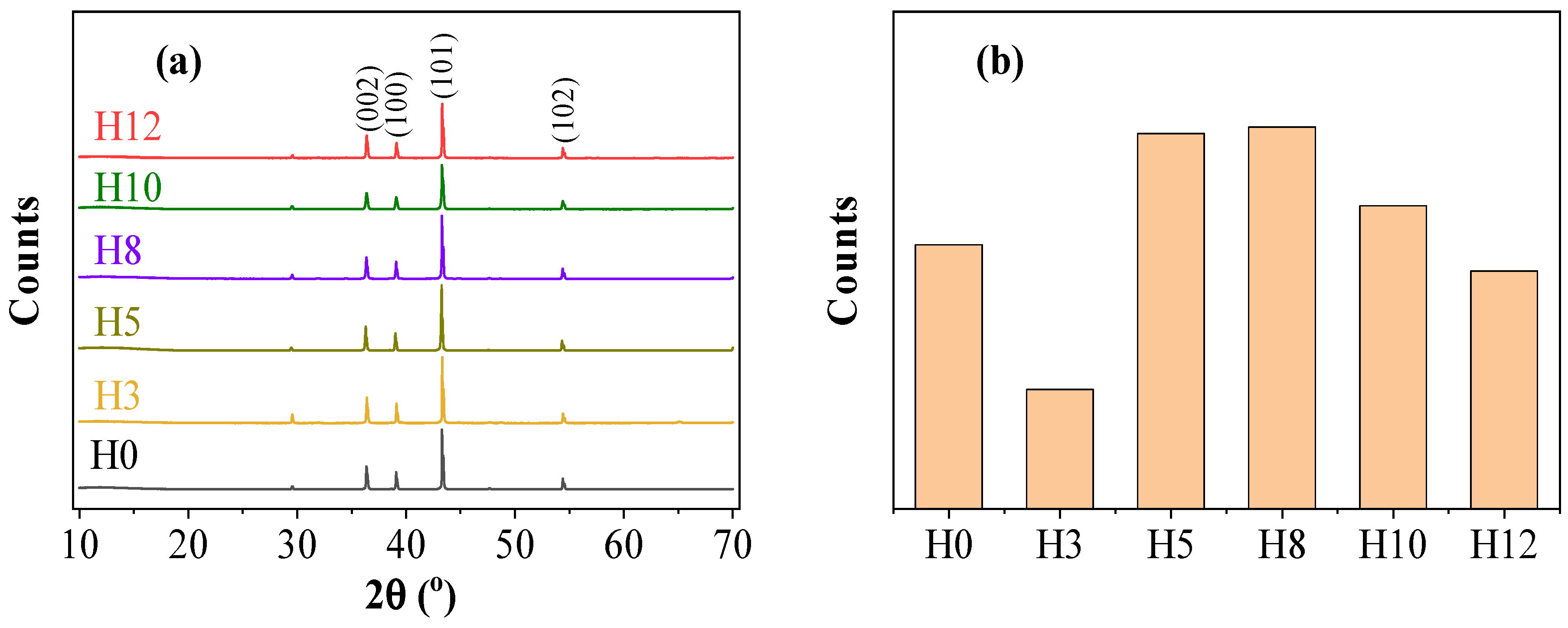

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted to determine the crystalline phases present in the paint film and evaluate the effect of extract addition on the structure of the pigment particles. Figure 3 shows the XRD patterns of samples H0, H3, H5, H8, H10, H12 and the change in intensity of the main diffraction peak.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the paint films: (a) XRD patterns of the samples and (b) intensity of the main diffraction peak (101) at 2θ ≈ 43.28°.

As shown in Figure 3a, all coating samples exhibited diffraction peaks at 2θ = 36.2°, 38.9°, 43.2°, 54.3°, and 70.6°, corresponding to the (002), (100), (101), (102), and (110) planes of hexagonal close-packed (hcp) metallic zinc [23]. The (101) peak at 43.2° was the most intense reflection. The absence of new peaks or detectable peak shifts across all extract-containing samples indicates that the crystalline structure of zinc remained unchanged upon addition of the henna extract, suggesting no chemical modification of the pigment phase.

Although the peak positions remained constant, the intensity variation of the (101) peak revealed a more complex structural effect, as shown in Figure 3b. The diffraction intensity did not follow a monotonic trend with extract concentration. Relative to the control sample (H0), reduced intensities were observed for H3, H10, and H12, whereas samples H5 and H8 exhibited higher intensities, with H5 showing the most pronounced enhancement.

The significant increase in intensity at H5 was attributed to the improvement in pigment dispersion in the paint matrix. At an optimal concentration (5 wt%), the polyphenolic compounds in the extract are likely adsorbed onto the pigment surface, reducing particle agglomeration and promoting uniform distribution within the liquid paint matrix. Enhanced dispersion facilitates a more ordered packing of zinc particles during solvent evaporation and curing, favoring a preferential orientation of the (101) planes and thereby increasing the corresponding diffraction intensity [24]. This observation suggests that the henna extract functions not only as a corrosion inhibitor but also as a microstructural modifier within the coating.

The lower intensities at low (H3) and high (H10, H12) extract concentrations indicate suboptimal pigment dispersion. At low concentrations (H3), polyphenol adsorption onto the pigment surface is insufficient for effective dispersion. At high concentrations (H10, H12), excessive amounts of organic extract may disturb the particle arrangement, increasing X-ray attenuation and leading to a decrease in peak intensity. These results indicate the effect of extract concentration on pigment orientation, with a concentration of 5 wt% (H5) producing the most ordered arrangement of zinc particles in the coating.

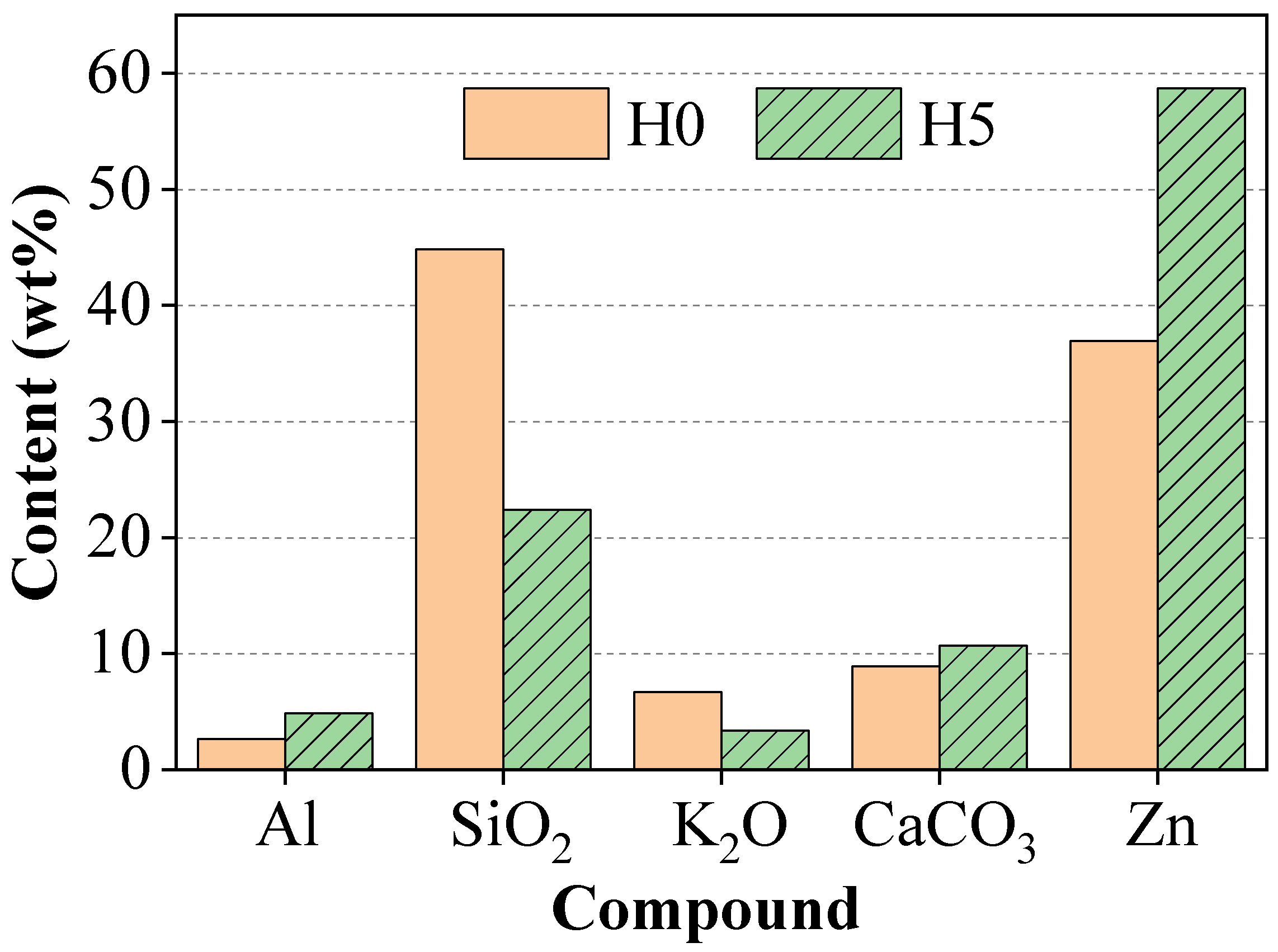

3.3. Surface Elemental Composition Analysis by X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

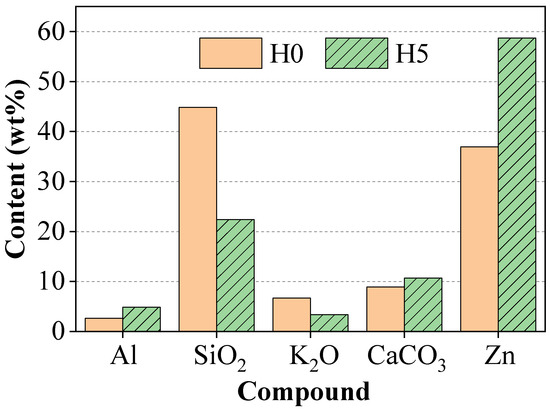

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was performed to determine and compare the elemental composition of the surface of the control paint film (H0) and the paint film containing the inhibitor (H5). The quantitative results (presented in Figure 4) showed an observable change in the surface composition in the presence of henna extract. Specifically, compared to sample H0, the surface of sample H5 showed a clear increase in Zn and Al content, while a significant decrease in Si content was recorded.

Figure 4.

XRF analysis results of the control sample (H0) and the paint sample containing 5 wt% extract (H5).

The analysis further confirmed the finding that at the optimum concentration (5 wt%), the polyphenol compounds in the extract act effectively as a dispersant. This promotes a uniform and stable distribution of the particles in the paint matrix in the liquid phase [24].

This result is consistent with the structural and morphological analysis. Furthermore, the ordered arrangement of the particles is also consistent with the XRD results, in which the increased diffraction intensity in sample H5 indicates the preferential orientation of the zinc particles.

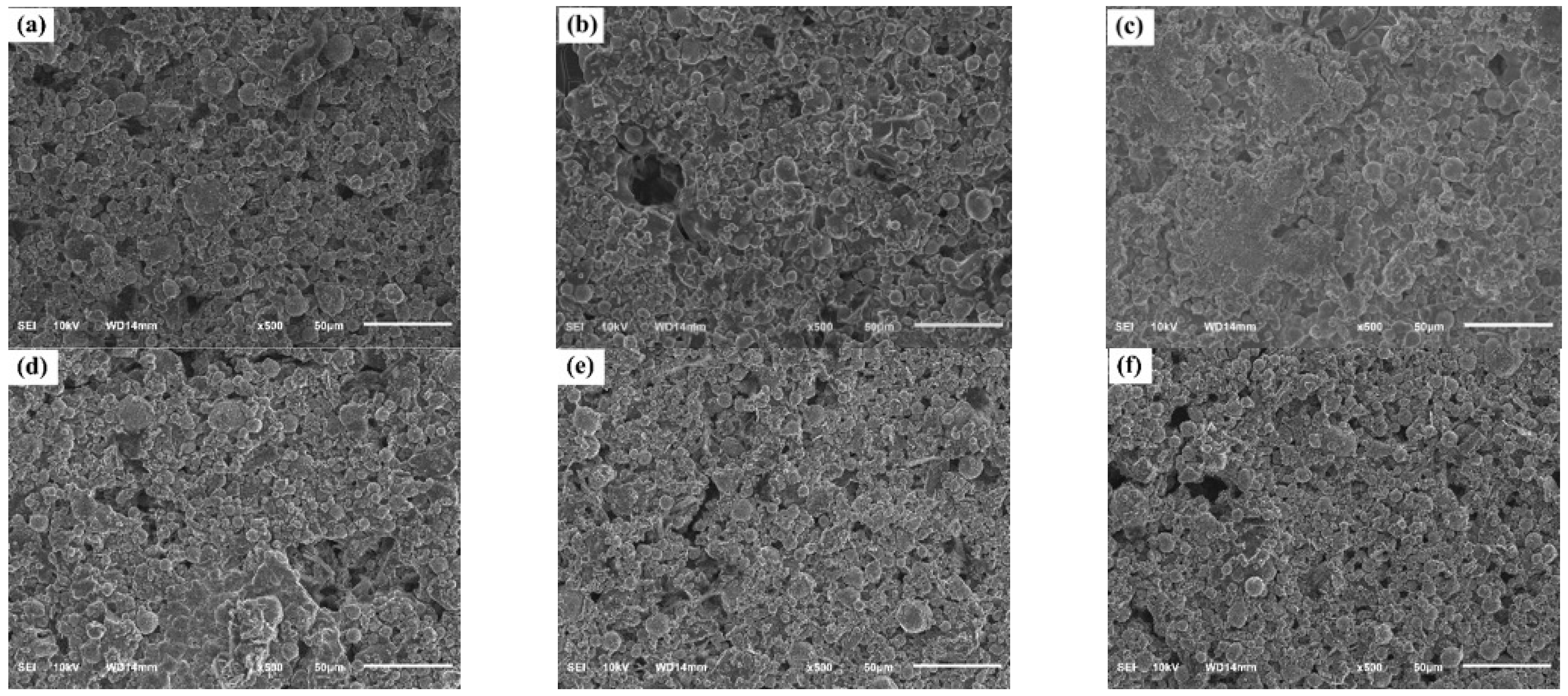

3.4. Surface Morphology Analysis

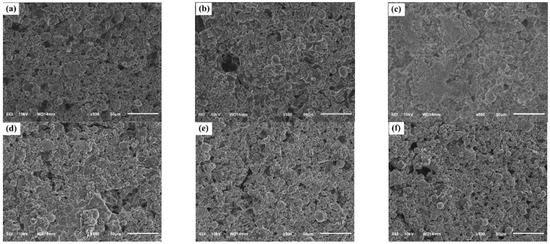

The surface morphology of the coating films was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and the images are presented in Figure 5. All samples exhibited a characteristically rough microstructure composed of spherical zinc particles and flake-shaped Zn–Al pigments embedded within the silicate matrix.

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showing the surface morphology of paint films: (a) H0, (b) H3, (c) H5, (d) H8, (e) H10, and (f) H12.

In the control coating (H0), the surface appeared relatively porous, with numerous micro-voids and gaps between adjacent pigment particles. Such a microporous network is typical of zinc-rich silicate coatings and plays an important role in maintaining electrical connectivity between zinc particles, thereby supporting the cathodic protection mechanism [25]. Nevertheless, excessive porosity can create pathways that facilitate the ingress of corrosive species—particularly water molecules and chloride ions—potentially compromising long-term protective performance.

With the incorporation of the extract, clear concentration-dependent changes in surface morphology were observed. At low to moderate extract loadings (3 wt% (H3) and 5 wt% (H5)), the coating surface became noticeably more compact and uniform compared with the control H0. In particular, sample H5 exhibited closely packed pigment particles with a marked reduction in both the size and number of surface pores. Such densification of the coating microstructure enhances the physical barrier properties, thereby hindering electrolyte ingress and contributing to improved corrosion resistance [26].

However, at higher extract concentrations (8–12 wt%; samples H8, H10, and H12), the coating surface gradually became less homogeneous. For sample H12, the formation of pigment agglomerates and an increase in surface porosity were clearly evident. These defects likely arise from an excess of organic constituents interfering with the condensation and crosslinking of the silicate network, or promoting pigment–pigment interactions that result in particle agglomeration [27]. Such structural irregularities may compromise both barrier performance and the continuity of the zinc network required for effective cathodic protection.

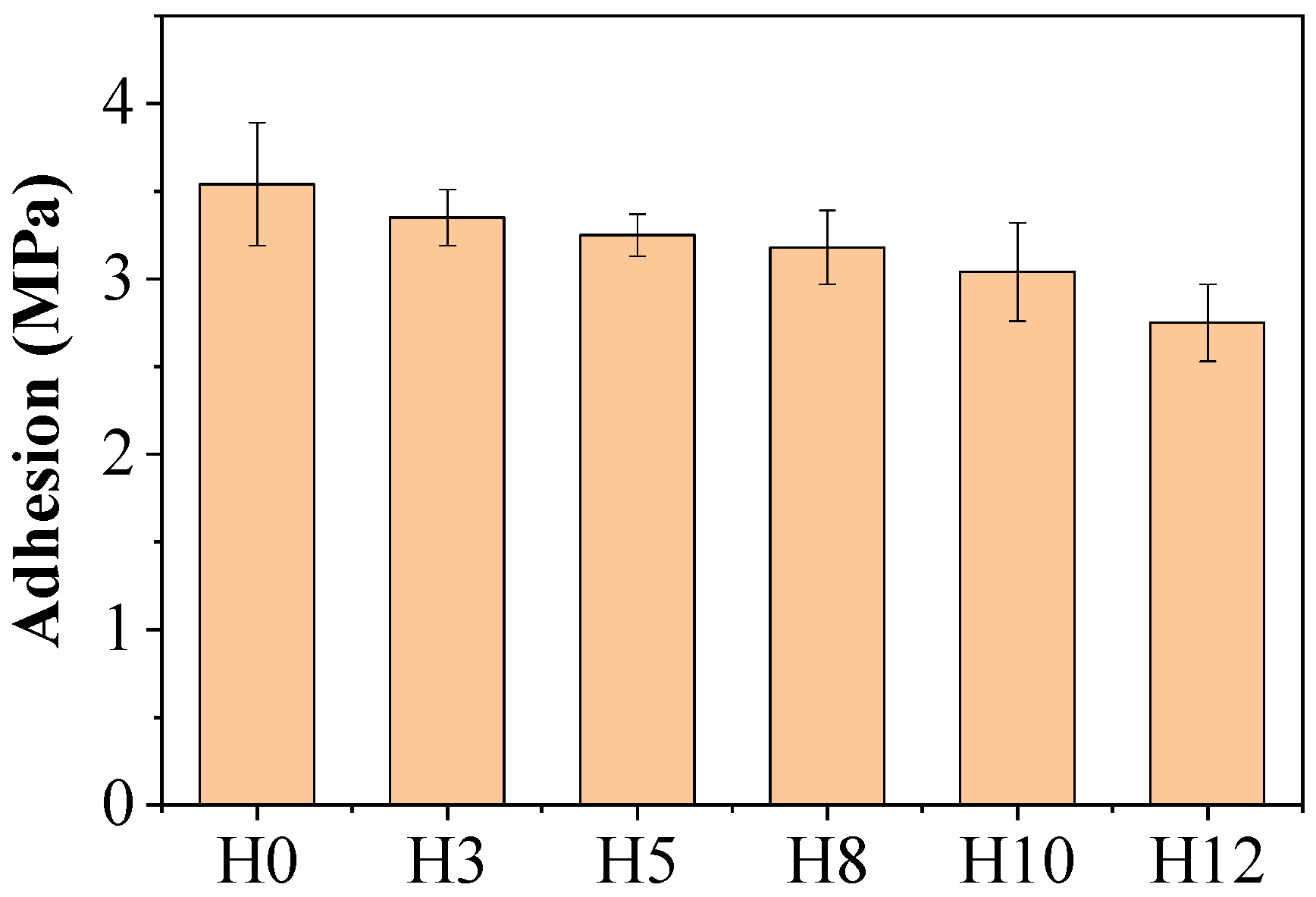

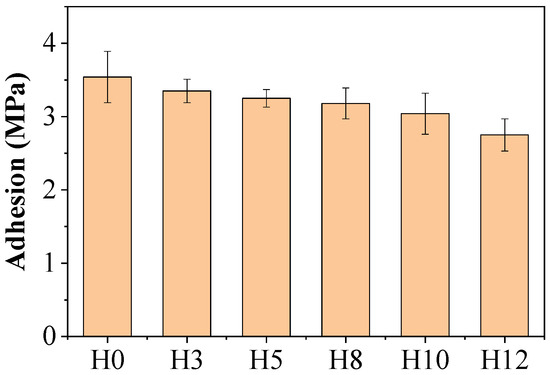

3.5. Adhesion Analysis (Pull-Off Test)

Figure 6 presents the pull-off adhesion results (ASTM D4541) for the coating films on carbon steel substrates. The control sample H0 exhibited the highest adhesion strength at 3.5 MPa. Upon incorporation of the henna extract, the adhesion values gradually decreased with increasing extract concentration, with sample H12 (12 wt%) showing the lowest value of 2.8 MPa.

Figure 6.

Test results of adhesion of paint films according to extract content, along with standard deviation SD values.

This adhesion loss can be explained by several mechanisms. First, the organic compounds present in the extract, mainly polyphenols, may hinder the formation of Si–O–Si cross-linked networks of the potassium silicate binder. The organic molecules also coat the pigment particles, reducing the direct interaction between the pigment and the silicate binder. This indicates that the presence of these molecules disrupt the continuity of the inorganic structure, resulting in a reduction in the adhesion strength of the paint film [28].

Second, at high extract concentrations, organic molecules tend to migrate and concentrate at the interface between the paint and the metal substrate. This accumulation can form a boundary layer, which impedes the direct interaction and chemical bonding between the silicate binder and the steel surface, consequently reducing the adhesion strength [29]. Furthermore, the adsorption of organic compounds onto the surface of zinc pigment particles can also negatively impact their wetting and subsequent bonding with the binder, contributing to a reduction in the overall mechanical integrity of the entire coating.

This finding highlights the importance of optimizing the inhibitor concentration, as excessive amounts, while potentially beneficial for corrosion resistance, can compromise essential mechanical properties such as adhesion.

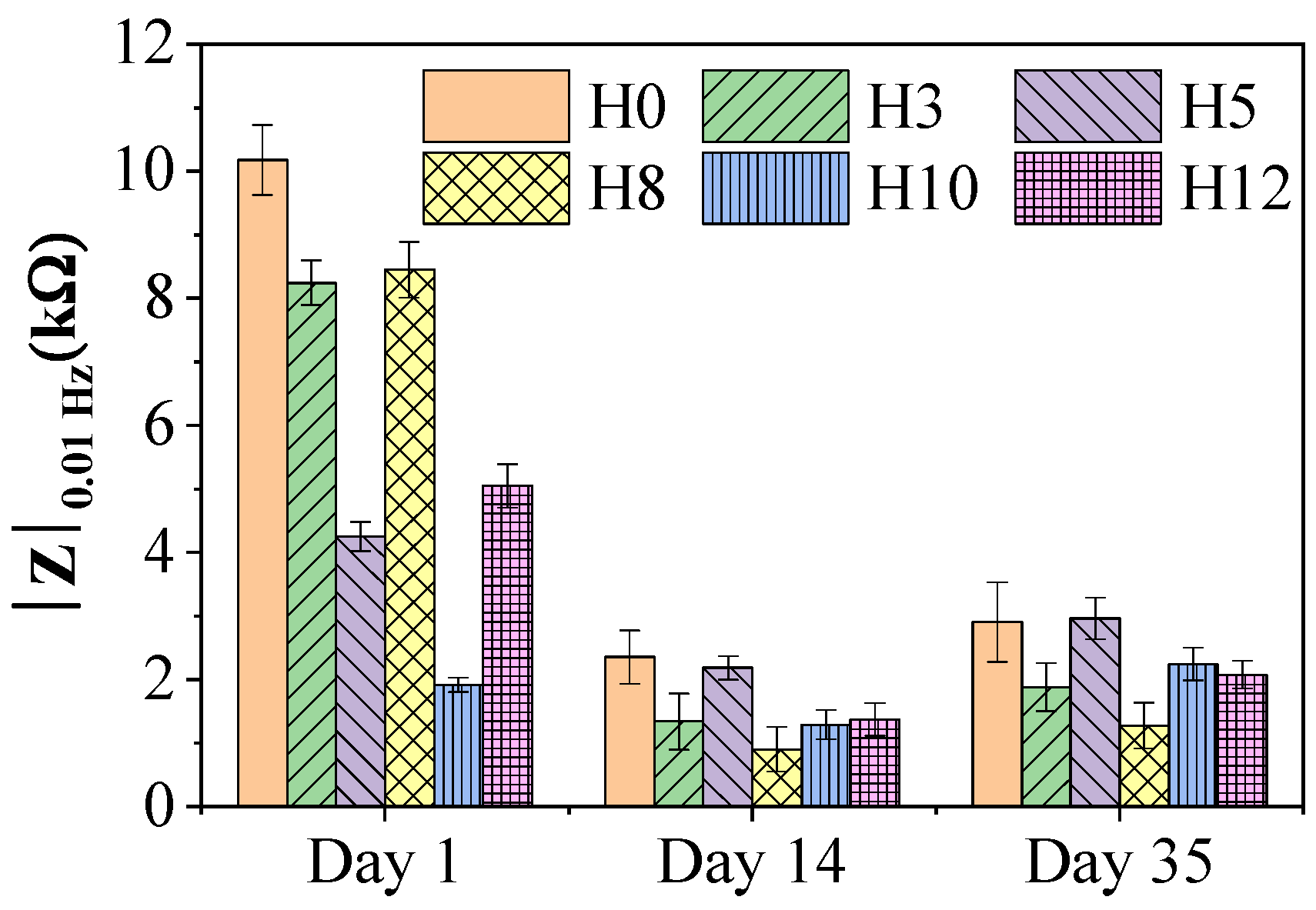

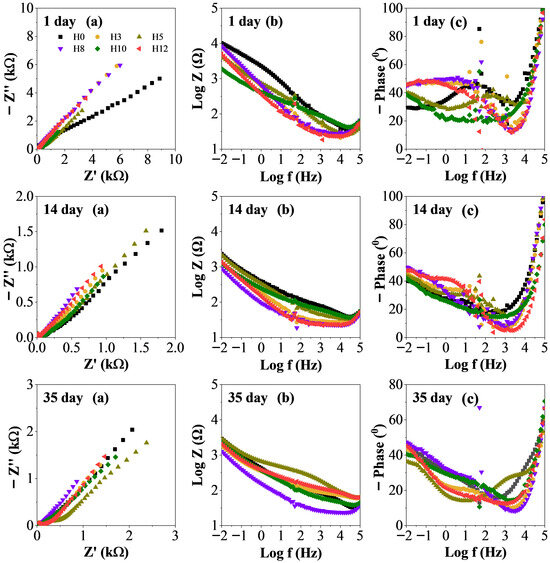

3.6. Electrochemical Impedance Spectrum (EIS) Analysis

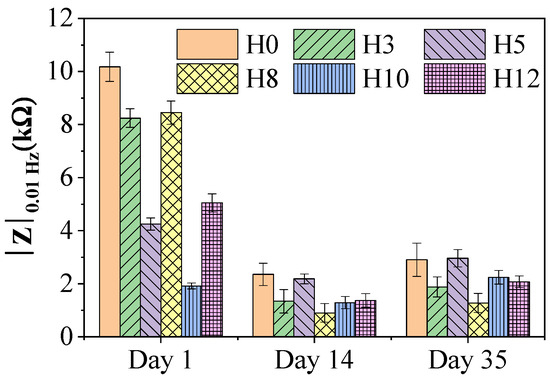

To evaluate the corrosion protection of the coatings over time, EIS measurements were performed after immersion cycles of the samples in a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Figure 7 shows the variation of the impedance modulus at low frequency (|Z|0.01 Hz)—a parameter reflecting the total impedance of the system and commonly used to evaluate the corrosion protection performance of the coating [30]. A higher value of |Z|0.01 Hz indicates a better protection of the coating.

Figure 7.

Impedance module value at low frequency (|Z|0.01 Hz) of paint films after 1 day, 14 days, and 35 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, along with standard deviation values.

The graph shows that all paint samples had an observable decrease in impedance value after the initial 14 days of immersion, and then tended to stabilize until day 35. This initial decrease is a common phenomenon, reflecting the process of electrolyte solution penetrating through the pores and micro-defects of the paint film to reach the base metal surface [31].

When comparing the performance between samples, on the first day, the control H0 paint film showed the highest impedance value. However, over time, the protective performance of H0 decreased substantially. By day 35, the H5 paint film (containing 5 wt% extract) showed the highest |Z|0.01 Hz value among all the samples, surpassing the control H0. This improved performance can be attributed to the synergistic effect of two mechanisms.

The first mechanism is the enhancement of the barrier properties. As evidenced by XRD and SEM analyses, the 5 wt% extract concentration seemed to act as a dispersant, resulting in a dense, homogeneous, and less porous paint film microstructure [26]. Such structural refinement significantly reduces electrolyte ingress, thereby delaying the onset of corrosion processes.

The second mechanism becomes dominant once the electrolyte reaches the steel substrate. The organic molecules from the henna extract can migrate with the solution and adsorb onto the metal surface, forming a protective molecular layer. This adsorbed film suppresses the electrochemical reactions responsible for corrosion, enabling the system to maintain high impedance over prolonged immersion [29,32].

Coatings containing other extract concentrations (H3, H8, H10, H12) exhibited lower |Z|0.01 Hz values than both H5 and H0 on day 35. This behavior reinforces the presence of an optimal inhibitor concentration. At concentrations below 5 wt%, the extract content is insufficient to form an effective protective layer at the metal interface. Conversely, at higher concentrations, excess organic material may disrupt the structural integrity of the coating—consistent with SEM observations and reduced adhesion—creating more pathways for electrolyte penetration and diminishing the overall protection.

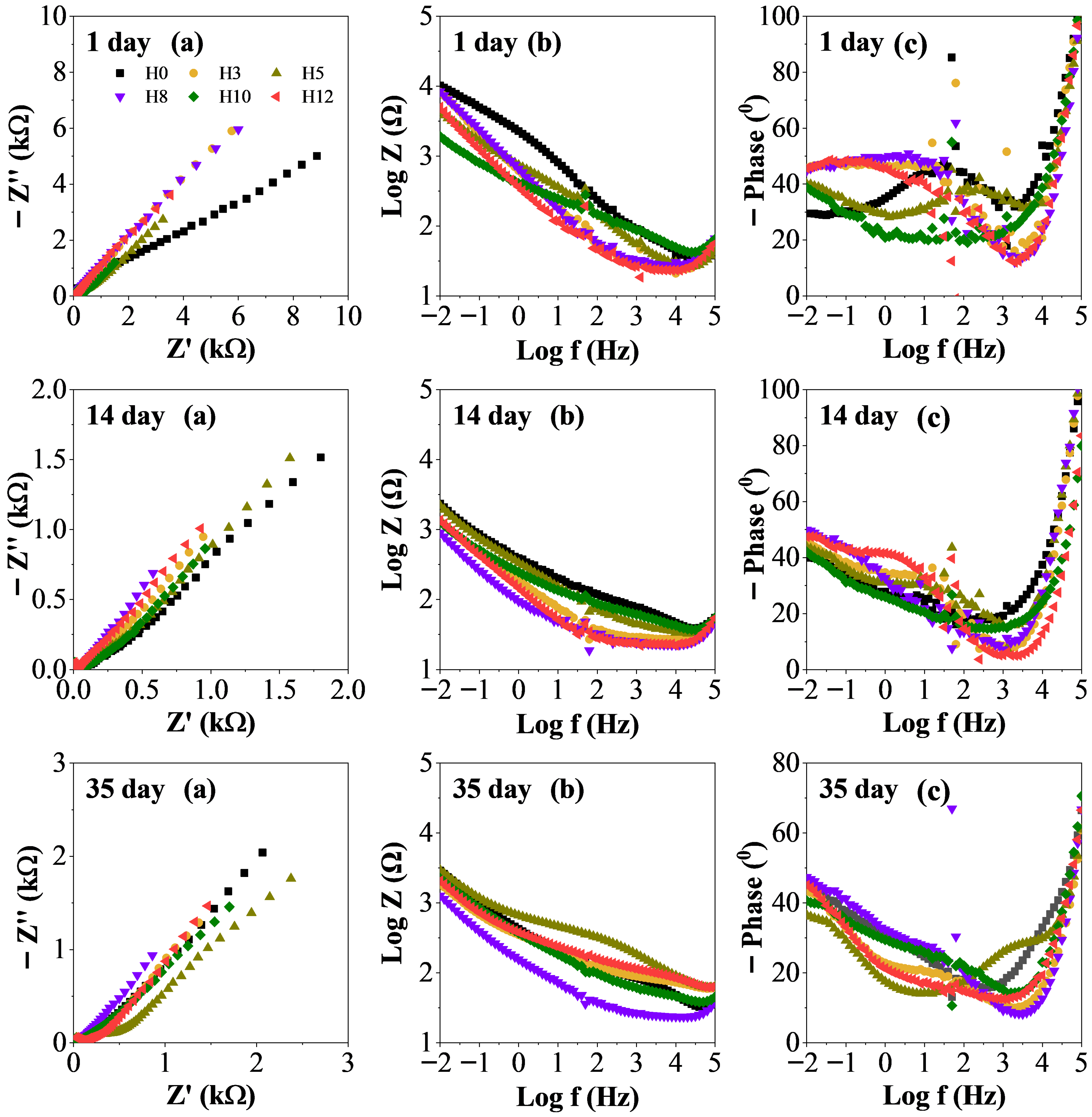

3.7. Detailed EIS Analysis

Figure 8 presents detailed electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data in the form of Nyquist (a), Bode (b), and phase angle (c) of samples at 1, 14, and 35 days of immersion. These plots provide a more detailed insight into the mechanism and kinetics of the corrosion process, complementing the summary data in Figure 7.

Figure 8.

Electrochemical impedance spectra of samples versus immersion time in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution, Nyquist plot (a), Bode plot (b), and phase angle plot (c).

Over the 35-day immersion period, all samples exhibited notable evolution in their impedance responses. In the Nyquist plots (Figure 8a), the progressive reduction in the diameter of the semicircles indicates a decrease in charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is inversely correlated with the corrosion rate [33]. This decline reflects the gradual deterioration of coating protection as electrolyte penetration increases.

The Bode phase angle plot of the pigments (Figure 8c) further support these observations. The shift of the maximum phase angle toward lower frequencies, particularly evident in sample H5 at long immersion times, suggests enhancement and persistence of the coating’s capacitive behavior. This behavior is indicative of improved barrier resistance and a slower rate of water and ion permeation. Conversely, for samples exhibiting poorer performance (e.g., H0), the emergence of two well-separated time constants in the medium- and low-frequency regions after 14 and 35 days confirms coating degradation. The high-frequency time constant corresponds to the coating layer (Rc, Cc), while the low-frequency time constant reflects the charge-transfer process and double-layer capacitance at the metal/coating interface (Rct, Cdl). Their appearance signals a transition from dominant barrier protection to weakened sacrificial protection mechanisms.

A similar trend is evident in the Bode magnitude plots (Figure 8b), where the decrease in low-frequency impedance and the appearance of an additional low-frequency relaxation process denote electrolyte ingress and active corrosion occurring at the steel surface beneath the coating [33].

By day 35, differences in protective performance among the samples became most pronounced. Sample H5 exhibited the largest semicircle diameter on the Nyquist plot, indicating the highest Rct and thus the highest corrosion resistance. In contrast, sample H12 showed the smallest semicircle, while the control sample H0 displayed an intermediate response. Samples H3, H8, and H10 also exhibited smaller semicircles than H5, consistent with the overall protection trends observed previously. These results indicate that the H5 coating maintained its capacitive (barrier-dominated) behavior more effectively than the other formulations during prolonged exposure to the corrosive environment.

In contrast, sample H12 exhibited the smallest semicircular diameter and the lowest impedance value, indicating a high corrosion rate. This further suggests that the 12 wt% extract concentration was too high, which may have altered the paint film structure and reduced the protective ability. The control sample H0 had a performance between H5 and H12, which indicates that while it had high initial barrier properties, it lacked an active protection mechanism to resist long-term corrosion once the electrolyte had penetrated. Therefore, these detailed EIS data further support the conclusion that the 5 wt% concentration of henna extract (sample H5) provides the optimal combination of barrier protection and active inhibition mechanisms, resulting in the most effective anti-corrosion efficacy.

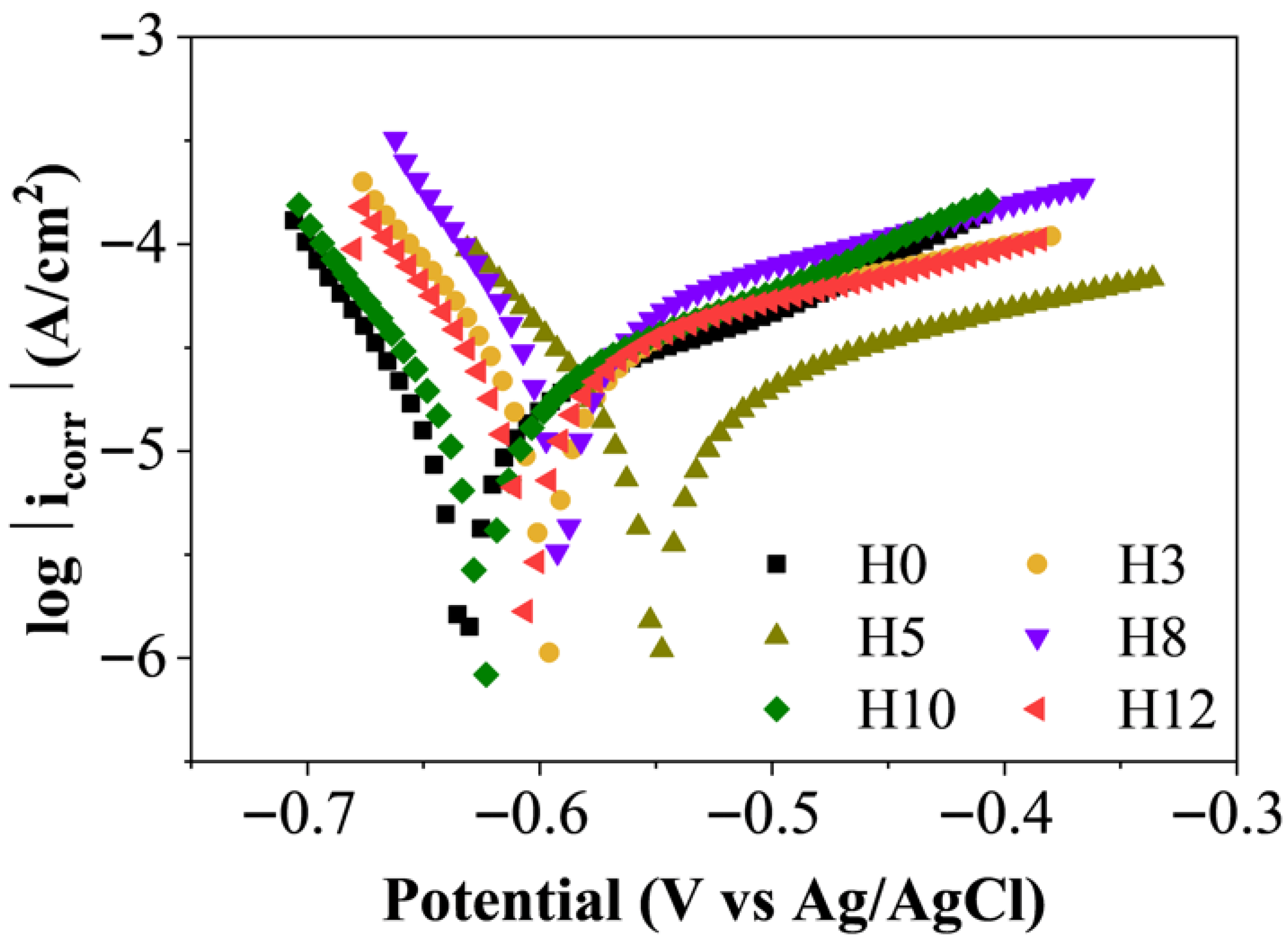

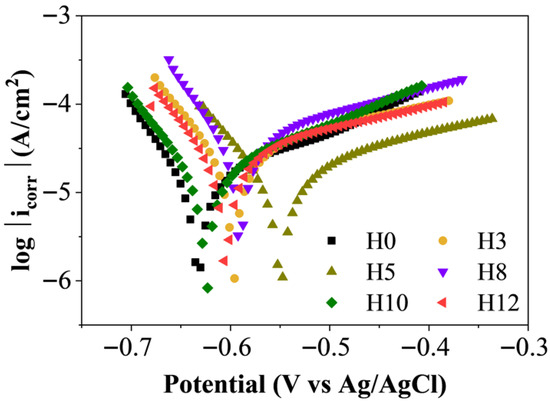

3.8. Polarization Curve Analysis (Potentiodynamic Polarization)

To further assess corrosion inhibition performance and clarify the underlying mechanisms, potentiodynamic polarization measurements were performed after 35 days of immersion. Figure 9 and Table 1 summarize the polarization curves and corresponding electrochemical parameters, providing insight into the kinetics of anodic and cathodic processes occurring at the coating/steel interface.

Figure 9.

Graph showing polarization curve when the sample is immersed in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for 35 days.

Table 1.

Electrochemical parameters extracted from the polarization curves of the paint films after 35 days of immersion in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution for 35 days.

From Table 1, it is evident that the corrosion potentials (Ecorr) of all extract-containing samples (H3–H12) shifted toward more positive values compared with the control coating H0 (−0.633 V). The most positive value was observed for H5 (−0.55 V). A positive shift in Ecorr typically indicates anodic inhibition, suggesting that the extract reduces the dissolution tendency of the metal substrate [34]. However, examination of the polarization curves shows that both the anodic and cathodic branches shifted in the presence of the extract relative to H0. Combined with the observed changes in both anodic (βa) and cathodic (βc) Tafel slopes (Table 1), these results demonstrate that the henna extract functions as a mixed-type inhibitor, simultaneously suppressing metal dissolution at the anode and the oxygen reduction reaction at the cathode [35]. Similar mixed-type inhibition behavior for L. inermis extracts has been reported in previous studies [13,36].

A key parameter for evaluating corrosion performance is the corrosion current density (icorr), which is directly proportional to the corrosion rate. The results show that sample H5 (5.385 μA/cm2) had a slightly higher icorr value than H0 (4.507 μA/cm2), whereas the other extract-containing samples displayed substantially higher icorr values. At first glance, this appears inconsistent with the EIS results, where H5 clearly outperformed H0.

This discrepancy can be rationalized by considering the electrochemical behavior of zinc-rich coatings. A lower icorr value for H0 may not solely reflect lower steel corrosion but may instead indicate a passive state dominated by sacrificial zinc dissolution. In zinc-rich silicate coatings, the measured icorr includes contributions from the anodic dissolution of zinc particles, which provide cathodic protection to the steel substrate [37]. Thus, the low icorr value of H0 may simply reflect the reduced activity of zinc dissolution rather than superior overall protection. Conversely, the slightly higher icorr value of H5 may signify an actively operating cathodic protection system, in which zinc particles dissolve to protect the underlying steel.

This difference can be explained as a low icorr value such as that of sample H0 may indicate that the system is in a passive state. In this system, the measured icorr reflects not only the corrosion of the steel substrate but also includes the current generated by the sacrificial dissolution of zinc particles, which is the main protection mechanism (cathodic protection). Therefore, a low icorr value such as that of sample H0 may simply indicate that the system is in a relatively passive state. On the other hand, a higher icorr value of sample H5 may be an indication of an active cathodic protection system, in which zinc particles are actively dissolving to protect the steel [37].

Given this complexity, polarization resistance (Rp), which is inversely related to corrosion rate at the metal interface, serves as a more reliable indicator of true substrate protection [38]. As shown in Table 1, H5 exhibited the highest Rp value (1939.4 Ω), surpassing both H0 (1694.5 Ω) and the other extract-containing samples. This trend aligns well with the EIS results, confirming that the 5 wt% extract loading provided the best overall protection. This finding is consistent with previous reports on coatings containing henna extract, where an optimum concentration enhances performance, while either insufficient or excessive extract content leads to reduced protective efficiency [32,39].

4. Conclusions

The findings of this study revealed a strong quantitative correlation between the concentration of L. inermis extract and the corrosion-protection efficiency of the zinc-rich silicate coating. This relationship reflects the extract’s dual functionality: (i) enhancing pigment dispersion within the matrix, and (ii) providing eco-friendly active corrosion inhibition at the metal/coating interface. The formulation containing 5 wt% extract (H5) delivered the best overall performance, exhibiting the highest low-frequency impedance (|Z|0.01 Hz) after 35 days. At this optimal level, the extract facilitated uniform zinc pigment distribution and promoted the formation of a denser, more coherent microstructure, thereby strengthening barrier resistance and limiting electrolyte penetration. Simultaneously, its polyphenolic constituents adsorbed onto the steel surface to form a stable protective film, ensuring sustained active inhibition. In contrast, higher extract loadings (8–12 wt%) deteriorated coating performance by disrupting the silicate network, yielding a more porous structure and progressively reducing adhesion strength—from 3.5 MPa in the control to 2.8 MPa at 12 wt%. Overall, these findings emphasize that appropriate optimization of green inhibitor content is essential to achieve the best balance of barrier protection, active corrosion inhibition, and mechanical durability in sustainable zinc-rich coating systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.T.N.; methodology: L.T.N. and N.H.; formal analysis and investigation: T.A.K. and P.M.P.; writing—original draft preparation: L.T.N., N.H. and T.-D.N.; writing—review and editing: T.-D.N., L.T.N. and N.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Grant Number CSCL18.02/24-25.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lobo, R.E.; Guzmán, B.; Orrillo, P.A.; Domínguez, C.C.; Jimenez, L.E.; Torino, M.I. Corrosion: Basics, adverse effects and its mitigation. In Sustainable Food Waste Management: Anti-Corrosion Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.S.; Patil, V.J.; Gite, V.V. High performance coating formulation using multifunctional monomers and reinforcing functional fillers for protecting metal substrate. Pigm. Resin Technol. 2025, 54, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakaei, M.; Danaee, I.; Zaarei, D. Investigation of corrosion protection afforded by inorganic anticorrosive coatings comprising micaceous iron oxide and zinc dust. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.X.; Li, B.J.; Peng, Y.L.; Yue, W.T. Influence of zinc content on anti-corrosion performance of zinc-rich coatings. AMM 2013, 423, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Liang, M.J.J.o.A. The formation mechanism of the composited ceramic coating with thermal protection feature on an Al12Si piston alloy via a modified PEO process. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 682, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahayata, B.; Mahanta, S.K.; Upadhyay, P.; Mendon, R.R.; Basu, A.; Das, S.; Mallik, A. An approach to improve corrosion resistance in electro-galvanized Zn-Al composite coating by induced passivity. Mater. Lett. 2023, 351, 135013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubielewicz, M.; Langer, E.; Krolikowska, A.; Komorowski, L.; Wanner, M.; Krawczyk, K.; Aktas, L.; Hilt, M. Concepts of steel protection by coatings with a reduced content of zinc pigments. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 161, 106471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, A.; Bahmani, E.; Aghdam, A.S.R. Plant extracts as sustainable and green corrosion inhibitors for protection of ferrous metals in corrosive media: A mini review. Corros. Commun. 2022, 5, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Solanki, A.S.; Thakur, A.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.K. Phytochemicals as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in sulfuric acid solutions: A review. Corros. Rev. 2024, 42, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Karthiga, N.; Keerthana, R.; Umasankareswari, T.; Krishnaveni, A.; Singh, G.; Rajendran, S. Extracts of leaves as corrosion inhibitors-An overview and corrosion inhibition by an aqueous extract of henna leaves (Lawsonia inermis). Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2020, 9, 1169–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, A.; Ashiq, K.; Khalid, M.; Munir, A.; Akbar, J.; Ahmed, A. An up-to-date review on the phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of the Lawsonia inermis. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2024, 34, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamafo Fouegue, A.D.; Ghogomu, J.N.; Bikélé Mama, D.; Nkungli, N.K.; Younang, E. Structural and antioxidant properties of compounds obtained from Fe2+ chelation by juglone and two of its derivatives: DFT, QTAIM, and NBO studies. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2016, 2016, 8636409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshkhou, Z.; Torkghashghaei, M.; Baboukani, A.R. Corrosion inhibition of henna extract on carbon steel with hybrid coating TMSM-PMMA in HCL solution. OJSTA 2018, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik, W.W.; Zulkifli, F.; Sulaiman, O.; Samo, K.; Rosliza, R. Study of henna (Lawsonia inermis) as natural corrosion inhibitor for aluminum alloy in seawater. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2012, 36, 012043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, F.; Ali, N.a.; Yusof, M.S.M.; Isa, M.; Yabuki, A.; Nik, W.W. Henna leaves extract as a corrosion inhibitor in acrylic resin coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Iwata, S. Theoretical studies of geometric structures of phenol-water clusters and their infrared absorption spectra in the O–H stretching region. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Mukhopadhyay, D.P.; Chakraborty, T. On the origin of donor O–H bond weakening in phenol-water complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 204306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, A.; El-Gendy, N.S. Thermodynamic, adsorption and electrochemical studies for corrosion inhibition of carbon steel by henna extract in acid medium. Egypt. J. Pet. 2013, 22, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muroya, M. Infrared spectra of SiO2 coating films prepared from various aged silica hydrosols. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1991, 64, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lópes, A.; Frost, R.L.; Scholz, R.; Xi, Y.; Amaral, A. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Characterization of the Silicate Mineral Gilalite Cu5Si6O17·7H2O. Spectrosc. Lett. 2014, 47, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R. Some applications of infrared spectroscopy in the examination of painting materials. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 1979, 19, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapolova, E.; Korolev, K.; Lomovsky, O. Mechanochemical interaction of silicon dioxide with chelating polyphenol compounds and preparation of the soluble forms of silicon. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devan, R.S.; Lin, J.-H.; Huang, Y.-J.; Yang, C.-C.; Wu, S.Y.; Liou, Y.; Ma, Y.-R. Two-dimensional single-crystalline Zn hexagonal nanoplates: Size-controllable synthesis and X-ray diffraction study. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4339–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Lin, Z.; Ju, Y.; Rahim, M.A.; Richardson, J.J.; Caruso, F. Polyphenol-mediated assembly for particle engineering. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morcillo, M.; Svoboda, M.; Feliu Jr, S.; Kanápek, B.; Simancas, J.; Kubátova, H.J.P. A new pigment to be used in combination with zinc dust in zinc-rich anti-corrosive paints. Pigm. Resin. Technol. 1998, 27, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawiah, B.; Asinyo, B.K.; Frimpong, C.; Howard, E.K.; Seidu, R.K. An overview of the science and art of encapsulated pigments: Preparation, performance and application. Color. Technol. 2022, 138, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becit, B.; Duchstein, P.; Zahn, D. Molecular mechanisms of mesoporous silica formation from colloid solution: Ripening-reactions arrest hollow network structures. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Liao, W.C.; Barrantes, A.; Edén, M.; Tiainen, H. Silicate-phenolic networks: Coordination-mediated deposition of bioinspired tannic acid coatings. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 9870–9874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcoen, K.; Gauvin, M.l.; De Strycker, J.; Terryn, H.; Hauffman, T. Molecular Characterization of Multiple Bonding Interactions at the Steel Oxide–Aminopropyl triethoxysilane Interface by ToF-SIMS. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.-M.; Cao, F.-Y.; Jiang, P.; Xie, J.-P. Barrier effect of zinc-rich coatings and evolutionary law of equivalent circuit elements of coatings. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 493, 144274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor, Y.B.; Sutter, E.; Takenouti, H.; Orazem, M.E.; Tribollet, B. Interpretation of electrochemical impedance for corrosion of a coated silver film in terms of a pore-in-pore model. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2014, 161, C573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.; Hegazi, M.; El-Azaly, A. Henna extract as green corrosion inhibitor for carbon steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 4668–4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croll, S.; Croes, K.; Keil, B. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: Characterizing the performance of corrosion protective pipeline coatings. In Proceedings of the Pipelines 2015, Baltimore, MD, USA, 23–26 August 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumya, Y.; Idouhli, R.; Oukhrib, A.; Khadiri, M.; Abouelfida, A.; Benyaich, A. Synthesis, electrochemical, thermodynamic, and quantum chemical investigations of amino cadalene as a corrosion inhibitor for stainless steel type 321 in sulfuric acid 1M. Int. J. Electrochem. 2020, 2020, 5620530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, H.; Vashi, R. The study of henna leaves extract as green corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in acetic acid. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2016, 8, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbout, J.; Touzani, R.; Bouklah, M.; Hammouti, B. An insight on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel in aggressive medium by henna extract. Int. J. Corros. Scale Inhib. 2021, 10, 1042–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wint, N.; Wijesinghe, S.; Yan, W.; Ong, W.; Wu, L.; Williams, G.; McMurray, H. The Sacrificial Protection of Steel by Zinc-Containing Sol-Gel Coatings. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofian, A.H.; Noda, K. Corrosion resistance and mechanism of zinc rich paint in corrosive media. ECS Trans. 2014, 58, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, H.; Zulkifli, F.; Suriani, M.; Sabri, M.M.; Nik, W.W. Lawsonialnermis extract enhances performance of corrosion protection of coated mild steel in seawater. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 78, 01091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).