Abstract

Construction and demolition (C&D) waste remains a critical challenge in India due to accelerated urbanisation and material-intensive construction practices. This study integrates survey-based assessment with machine learning to identify key causes of C&D waste and recommend targeted minimization strategies. Data were collected from 116 professionals representing junior, middle, and senior management, spanning age groups from 20 to 60+ years, and working across building construction, consultancy, project management, roadworks, bridges, and industrial structures. The majority of respondents (57%) had 6–20 years of experience, ensuring representation from both operational and decision-making roles. The Relative Importance Index (RII) method was applied to rank waste causes and minimization techniques based on industry perceptions. To enhance robustness, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Linear Regression models were tested, with Random Forest performing best (R2 = 0.62), providing insights into the relative importance of different strategies. Findings show that human skill and quality control are most critical in reducing waste across concrete, mortar, bricks, steel, and tiles, while proper planning is key for excavated soil and quality sourcing for wood. Recommended strategies include workforce training, strict quality checks, improved planning, and prefabrication. The integration of perception-based analysis with machine learning offers a comprehensive framework for minimising C&D waste, supporting cost reduction and sustainability in construction projects. The major limitation of this study is its reliance on self-reported survey data, which may be influenced by subjectivity and regional bias. Additionally, results may not fully generalize beyond the Indian construction context due to the sample size and sectoral skew. The absence of real-time site data and limited access to integrated waste management systems also restrict predictive accuracy of the machine learning models. Nevertheless, combining industry perception with robust data-driven techniques provides a valuable framework for supporting sustainable construction management.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is one of the largest consumers of natural resources and a significant contributor to global waste generation [1,2]. Rapid urbanisation and infrastructure expansion in India have further accelerated the production of construction and demolition (C&D) waste [3], leading to landfill pressure, environmental degradation, resource depletion, and economic losses [4]. Understanding the major causes of C&D waste and identifying effective minimization strategies therefore remains essential.

Existing studies show that concrete, tiles, and excavated soil constitute the bulk of construction and demolition waste, often arising from improper planning, material mis-handling, poor workmanship, and inadequate quality control [5,6,7]. Prior work has identified several causative factors, including weak coordination of design documents, indifference to environmental impacts, inefficient site layouts, unskilled manpower, and procurement errors [7,8]. While international research provides extensive insights into sustainable waste management practices, country-specific studies in India—particularly those focused on waste causation and project-level minimization—remain comparatively limited.

Construction and demolition waste management frameworks emphasise reduction, reuse, recycling, energy recovery, and safe disposal [9,10]. However, their implementation is hindered by inadequate segregation facilities, high recycling costs, weak regulatory enforcement, and low stakeholder awareness [11,12]. Sustainable design approaches such as standardisation, supply chain alliances, off-site prefabrication [13], and building information modelling (BIM)-enabled coordination [14,15,16] have demonstrated potential, but adoption remains inconsistent across Indian construction projects.

Most existing construction and demolition waste studies rely on descriptive or case-based methods that do not provide predictive decision-support capability. Only a few studies integrate perception-based prioritisation methods such as the Relative Importance Index (RII) with machine learning models capable of forecasting effective waste minimization strategies [17,18,19]. This reveals a clear methodological gap—particularly in the Indian context—where the fusion of qualitative industry perceptions with quantitative predictive tools remains largely unexplored.

To address these gaps, the present study combines survey-based insights from Indian construction professionals with machine learning techniques (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Linear Regression) to identify and predict the most effective project-level minimization strategies for major waste types. The study aims to strengthen material efficiency, reduce waste generation, and contribute to sustainable and cost-effective construction practices in India.

2. Theoretical Background

Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste management has traditionally relied on qualitative assessments and perception-based prioritization methods such as the Relative Importance Index (RII) to identify key causes and effective mitigation strategies. While these approaches provide valuable insights into industry stakeholder views, they inherently lack predictive validation and quantitative rigor, limiting their ability to forecast waste generation or objectively evaluate intervention outcomes. This gap underscores a need for methodologies that combine qualitative judgment with data-driven, predictive analytics to enhance decision-making robustness.

Machine learning (ML) techniques offer significant potential in overcoming these limitations by enabling the modeling of complex, nonlinear relationships in construction waste data and facilitating the prediction and optimization of waste reduction strategies. Recent advances in ML application to waste management demonstrate capabilities in tasks such as waste classification, generation forecasting, and process optimization, thus transforming traditional waste management from reactive to proactive systems. By integrating perception-driven indices like RII with ML models, this study addresses both the interpretive and predictive aspects of C&D waste management, filling an important methodological void. Consequently, this hybrid approach aligns with sustainability objectives by combining industry expertise with advanced computational tools to better target waste minimization interventions.

3. Methodology

The study on the causes and strategies for minimization of Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste in the Indian construction industry adopted a comprehensive case study–based, mixed-methods design to examine the multifaceted drivers of waste generation and evaluate the effectiveness of minimization strategies [20,21]. This design addressed both a conceptual gap—limited empirical understanding of how specific causes and mitigation practices interact across project stages—and a methodological gap in systematically prioritising those factors for decision-making. By combining quantitative survey analysis with qualitative interpretation, the research integrated numerical rankings with contextual insights, thereby capturing a holistic picture of waste management practices across different project types and organisational settings [22,23].

To quantify the relative influence of different factors, the Cause Significance Index (CSI) was employed for cause analysis, while the Relative Importance Index (RII) was applied to evaluate and prioritise minimization strategies. This dual-index approach ensured measurement precision in identifying both the most critical drivers of C&D waste and the most effective reduction measures, while still allowing triangulation with practitioner narratives and policy context [6,21].

The Relative Importance Index (RII) method has been widely used in construction management research as a robust tool for ranking factors based on respondents’ perceptions, particularly when working with Likert-scale survey data [6]. In the context of C&D waste minimization, RII facilitates systematic ordering of both causative factors and mitigation options by converting qualitative judgments into comparable quantitative scores. This enables the identification of dominant waste drivers—such as poor planning, inadequate skilled manpower, and material handling issues—as well as evidence-based prioritisation of mitigation strategies, including accurate estimation, quality control, prefabrication, and digital planning tools like BIM [6,21].

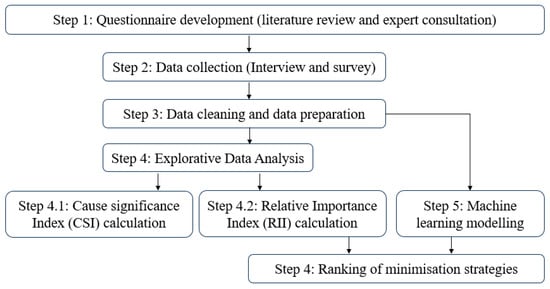

By employing the Relative Importance Index (RII) method, this study identifies and ranks the factors contributing to waste generation and the strategies most valued for minimization, based on inputs from junior, middle, and senior management professionals across Indian construction organisations. The methodological framework of the research is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Methodological Framework of the Study.

3.1. Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire was developed through an extensive review of literature on C&D waste management, combined with expert consultations involving project managers, engineers, and waste management specialists. It comprehensively covered two core dimensions:

- Causes of C&D waste generation (material handling errors, over-ordering, design changes, site management, etc.).

- Strategies for minimization (accurate planning, prefabrication, quality materials, reuse, and advanced technologies).

A 5-point Likert scale was employed, ranging from “Not Significant” (1) to “Highly Significant” (5), enabling respondents to indicate the perceived significance of each factor. The CSI formula was applied to rank waste causes, while the RII method was used to prioritise minimization strategies.

This dual-index approach ensured that the analysis addressed both the sources and solutions for C&D waste, offering a complete decision-making framework for industry stakeholders.

3.2. Data Collection Process

Data was collected in two stages:

- Interview Stage—A subset of respondents participated in semi-structured interviews to finalise the probable causes and minimization technique along with the literature review.

- Survey Stage—All respondents completed the structured questionnaire.

This two-stage process ensured that quantitative rankings were supported by practical, real-world explanations.

All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and their voluntary consent was obtained prior to completing the questionnaire. Participation was anonymous, and the collected data were used solely for academic research.

3.3. Pilot Test and Population Size

A pilot test was conducted using 50% of the predefined target sample to assess the clarity, relevance, and completeness of the questionnaire. Feedback from the pilot participants—representing different professional roles and organisational types—resulted in minor modifications that improved contextual accuracy and user comprehension. The pilot was carried out after the study population had been formally defined, ensuring that the instrument was refined within the boundaries of the intended respondent group.

The population for the study was formally defined prior to data collection as construction professionals working in organisations involved in building, infrastructure, or demolition activities across India. Based on this definition, a population size of 250 professionals from 90 organisations was identified. This group included individuals at junior, middle, and senior management levels to ensure a comprehensive understanding of waste-generating factors and minimization strategies.

Sampling and Survey Process

After incorporating pilot feedback, the final questionnaire was distributed via Google Forms to ensure accessibility and convenience for all respondents. A stratified random sampling approach was employed, with strata based on management levels. This method ensured proportional representation of professionals across different hierarchical tiers.

Out of the predefined population, 116 completed responses were received and included in the final analysis. The structured sampling distribution allowed for meaningful comparisons between the perceptions of various organisational levels regarding the causes of construction and demolition waste and the effectiveness of corresponding mitigation techniques.

3.4. Data Analysis Process for Machine Learning Approach

a. Data Cleaning:

Converted Likert scale responses (Strongly Agree → 5, Not Significant → 1) into numerical form to facilitate quantitative analysis. Additional checks were performed to detect missing or inconsistent responses, ensuring a clean and uniform dataset. This step helped standardize the input variables for machine learning processing and eliminated potential bias arising from ambiguous entries.

b. Feature Engineering:

Grouped the dataset into three major feature categories—Amount, Causes, and Minimization Techniques—to streamline model training. This categorization enabled a clearer understanding of how different types of variables interact and influence waste generation patterns. New derived features were also created where needed to enhance model interpretability and predictive strength.

c. Aggregation:

Calculated average significance scores for each waste type to summarize the overall perception of respondents. The average significance score represents the mean rating across all survey participants for a given waste amount, cause, or minimization technique. This aggregation helped highlight patterns and trends across the dataset and served as a baseline for comparison with machine learning predictions.

d. Machine Learning:

Used a Random Forest Regressor to model the relationship between waste generation, associated causes, and the effectiveness of various minimization techniques. The Random Forest algorithm was selected for its robustness, ability to handle nonlinear relationships, and capacity to manage high-dimensional data. The model provided insights into feature importance and enabled the prediction of the most influential factors contributing to waste minimization.

e. Ranking:

We identified the best minimization technique for each waste type based on predicted importance scores from the model. These predictions were further validated against the average significance scores to ensure alignment between machine learning outputs and survey-based insights. The final ranking offered a data-driven prioritization of techniques to support decision-making in sustainable waste management.

3.5. Explorative Data Analysis Process

a. The Cause Significance Index (CSI) was used to assess and rank the relative importance of the primary causes contributing to construction and demolition (C&D) waste. A higher CSI value indicates a stronger perceived influence of that cause on waste generation.

To assess and rank the causes of C&D waste, the CSI formula was applied:

W—Weight assigned to each factor by respondents.

A—Highest possible weights (e.g., 5 on a 5-point Likert scale).

N—Total number of respondents.

Higher CSI values indicate greater perceived significance of a cause, allowing prioritisation of the most pressing waste drivers.

b. The Relative Importance Index (RII) was applied to evaluate and rank the effectiveness of various waste minimization strategies. Higher RII values reflect a stronger consensus among industry professionals regarding the usefulness of a particular mitigation measure.

For ranking minimization strategies, the RII formula was used:

The same weight and respondent parameters applied, but here the focus was on ranking solution measures. Higher RII values denote strategies with stronger industry consensus on effectiveness.

This CSI–RII dual framework provided a balanced understanding, enabling the identification of critical waste causes and the most impactful mitigation strategies in the Indian construction context.

4. Result and Discussions

The results and discussions have been divided into four subsections such as (a) respondent analysis; (b) analysis of cause and minimization technique using explorative technique; (c) analysis of cause and minimization technique using machine learning approach.

The results and discussion are presented in three subsections:

- (a)

- Analysis of respondents;

- (b)

- Analysis of causes and minimization techniques using an explorative approach;

- (c)

- Analysis of causes and minimization techniques using a machine learning approach;

- (d)

- Comparison of machine learning models.

4.1. Respondent Analysis

In C&D waste minimization and management, analysing respondents’ personal details—such as age, experience, education level, job role, project type, and organisational affiliation—is essential for understanding how demographic factors influence the causes of C&D waste and the effectiveness of its minimization strategies.

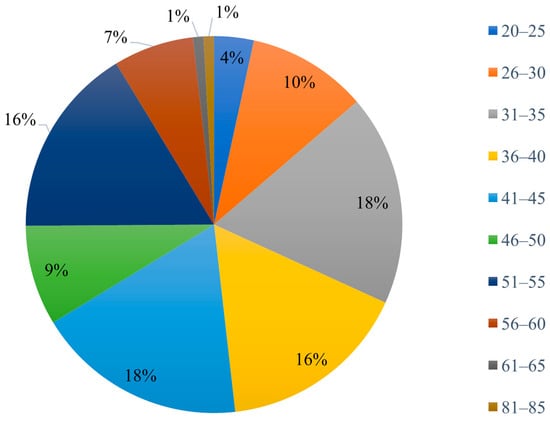

4.1.1. Age Group Distribution of Respondents

The age distribution of respondents shows a well-represented and diverse sample, spanning across various stages of professional life (Figure 2). The largest segments of respondents fall in the 31–35 and 41–45 age groups, each accounting for 18.1%, indicating a strong representation from mid-career professionals. Following these, the 36–40 and 51–55 age groups each account for 16.4% of the sample, indicating substantial representation of mid- to late-career professionals who are likely to occupy managerial or policy-influencing positions. The 26–30 age group makes up 10.3%, reflecting early-career professionals’ engagement in the field. Smaller but meaningful contributions come from the 46–50 (8.6%) and 56–60 (6.9%) age groups. Young professionals (20–25) and senior respondents (61–65 and 81–85) are less represented, each group contributing less than 4% individually. Overall, the data reflects a balanced and mature respondent base, predominantly composed of individuals in the 31 to 55 years age range—key demographics likely involved in planning, execution, and decision-making processes in the construction and waste management sectors.

Figure 2.

Distribution of respondents by age group, reflecting demographic representation in C&D waste management.

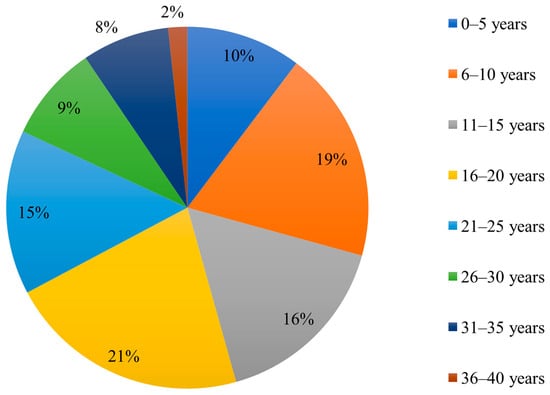

4.1.2. Experience Wise Distribution of Respondents

The respondents exhibit a wide range of professional experience as shown in Figure 3. The majority (57%) have 6 to 20 years of experience, with the highest share (21.6%) falling in the 16–20 years category. Early-career professionals (0–5 years) make up 10.3%, while highly experienced individuals with over 30 years of service represent a smaller portion (9.5%). This mix reflects a respondent pool with a strong blend of fresh perspectives and seasoned expertise.

Figure 3.

Respondents’ professional experience distribution highlighting varied expertise levels.

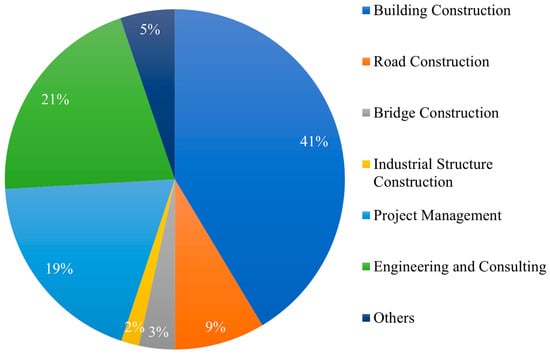

4.1.3. Sector Wise Distribution of Respondents

The project type-wise distribution shows that majority of respondents belong to the Building Construction sector (41.4%), indicating a strong representation from this core area of the construction industry. This is followed by professionals in Engineering and Consulting (20.7%) and Project Management (19%), reflecting significant input from technical advisory and managerial roles. Other sectors such as Road Construction (8.6%), Bridge Construction (3.4%), and Industrial Structure Construction (1.7%) have a smaller but relevant presence. The Others category accounts for 5.2%, showing diversity in sectoral backgrounds. Overall, the distribution demonstrates broad coverage across key construction domains. (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Project type distribution among respondents showing sectoral representation in construction.

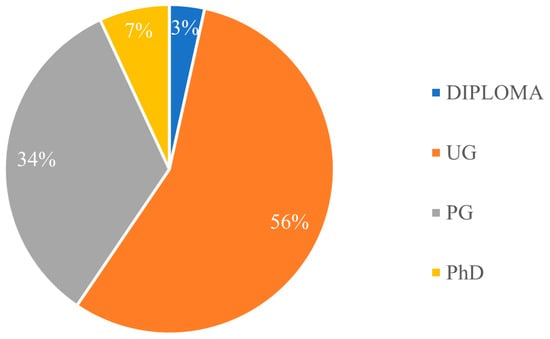

4.1.4. Qualification Wise Distribution of Respondents

The qualification-wise distribution shows that a majority of respondents, 3%, holds Diploma degree, 7% hold a graduation degree, followed by 34% with post-graduation degrees. This indicates that the workforce primarily consists of graduates, with a balanced representation from both technically trained and higher-educated professionals in the construction sector (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Educational qualifications of respondents indicating workforce composition.

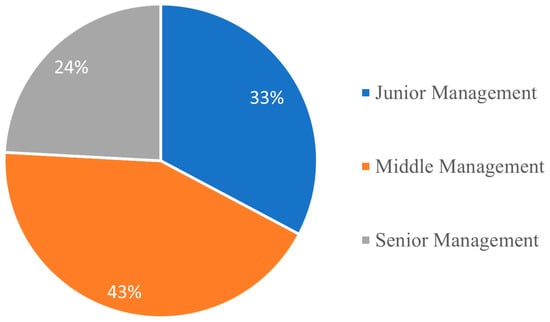

4.1.5. Designation Wise Distribution of Respondents

The designation-wise distribution shows that 43% of respondents belong to middle management, followed by 33% from junior management and 24% from senior management. This diverse representation across all levels of the organisational hierarchy provides a well-rounded perspective, enabling comprehensive insights into safety culture perceptions within Indian construction companies (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Designation-wise distribution of respondents representing organizational hierarchy.

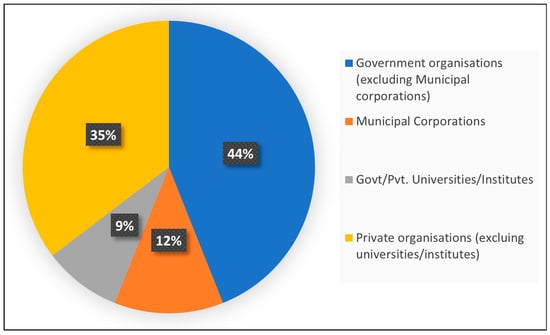

4.1.6. Organization Wise Distribution of Respondents

The organization-wise distribution of respondents in the survey reflects a diverse and well-represented group drawn from various sectors of the construction and infrastructure ecosystem (Figure 7). A total of 116 responses were recorded, spanning government departments, municipal corporations, private companies, and academic or research institutes, indicating a rich blend of perspectives.

Figure 7.

Organizational affiliations of respondents illustrating diversity across public, private, and academic sectors.

Among the major contributors, NBCC India Limited, a premier government construction agency, accounted for the highest number with 36 respondents, showcasing strong participation from central public sector undertakings. Other prominent government organizations included CPWD (3 responses), NHPC, IOCL, and BSNL, among others, collectively contributing 51 responses from non-municipal government bodies. In addition, 14 responses came from various municipal corporations such as the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) and Cuttack Municipal Corporation, reflecting grassroots-level engagement.

The academic and research domain was also well represented, with 41 respondents from reputed institutions such as IIT Bhubaneswar, KIIT University, NIT Agartala, and Institute of Rural Management, Anand, highlighting the inclusion of both technical knowledge and policy-oriented perspectives.

On the other hand, 10 responses were received from private organizations, including firms like AECOM, WSP, and Prasad & Company Pvt Ltd., ensuring industry views on construction practices and demolition waste management were captured. This cross-sectional participation adds significant depth and credibility to the survey findings, enabling a holistic understanding of the current practices, challenges, and opportunities in managing construction and demolition waste.

Awareness and Organizational Policies on Construction and Demolition (C&D) Waste Management.

The survey data reveals a relatively high level of awareness and institutional engagement regarding Construction and Demolition (C&D) waste management:

- Awareness of Guidelines:A significant majority (79.3%) of respondents indicated awareness of existing policies or guidelines related to C&D waste management. This suggests that information dissemination and training regarding waste management practices have reached a wide audience.

- Organizational Policies:About 75.9% of respondents confirmed that their organization has a formal policy for C&D waste minimization. This highlights a proactive approach among many organizations in institutionalizing sustainable construction practices.

However, there is still room for improvement. Approximately 20.7% are unaware of such guidelines, and 24.1% report the absence of a formal policy in their organization, indicating a need for broader policy implementation and awareness programs.

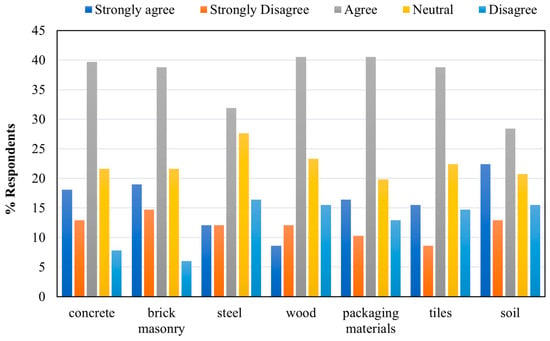

4.2. Types and Causes of Construction and Demolition Waste

Based on the survey data presented in Figure 8 which captures perceptions regarding the types of construction and demolition (C&D) waste, concrete emerged as the most frequently acknowledged waste material, with 39.7% agreeing and 18.1% strongly agreeing to its prevalence. Similarly, brick masonry was identified by a comparable proportion, with 38.8% agreeing and 19% strongly agreeing. Notably, wood and packaging materials recorded the highest “agree” responses (40.5% each), though the “strongly agree” percentages were relatively lower (8.6% and 16.4%, respectively).

Figure 8.

Perceived prevalence of different types of C&D waste materials according to survey respondents.

In contrast, steel exhibited a more dispersed opinion, with 31.9% agreeing, 27.6% remaining neutral, and a relatively high 16.4% disagreeing, indicating mixed views about its contribution to C&D waste. Soil was also recognized as a significant component, with 22.4% strongly agreeing—the highest in that category across all materials—while 28.4% agreed and 15.5% disagreed, reflecting diverse opinions. Tiles followed a similar pattern to concrete and brick masonry, with 38.8% agreement and 15.5% strong agreement.

Overall, the majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that concrete, brick masonry, wood, packaging materials, and tiles constitute major components of construction and demolition waste. Meanwhile, higher neutrality and disagreement for steel and soil suggest varying experiences or perceptions regarding their contribution to C&D waste across different construction contexts.

4.2.1. Cause Analysis of Concrete Waste

Based on the survey data collected from 116 respondents, a comprehensive cause analysis of concrete waste in construction projects reveals multiple contributing factors, with varying degrees of perceived significance.

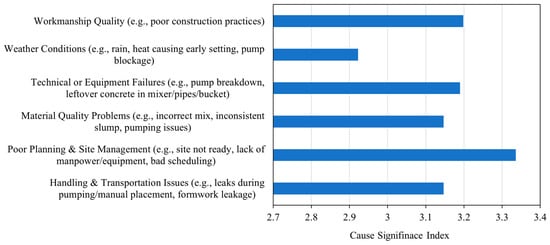

A comprehensive cause analysis of concrete waste was conducted based on responses from 116 construction professionals. The study aimed to identify key contributing factors and quantify their relative impact using the Cause Significance Index (CSI). The results, illustrated in Figure 9, highlight both technical and managerial causes, prioritized by their significance.

Figure 9.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) depicting factors contributing to concrete waste.

Poor Planning and Site Management emerged as the most critical factor, with the highest CSI of 3.34, consistent with findings that strategic site coordination critically influences waste generation [24,25]. This includes issues such as site unpreparedness, scheduling delays, and inadequate coordination of manpower and equipment. Such inefficiencies at the planning stage heavily influence material wastage, reinforcing the need for strategic site management.

Workmanship quality (CSI = 3.20) and equipment failures (CSI = 3.19) closely follow, echoing previous studies emphasizing human factors and technical issues in concrete waste [26,27]. Handling, transportation issues, and material quality problems (CSI = 3.15 each) align with known causes of wastage due to leakage, spillage, and inconsistent mix properties [4]. Weather and testing-related waste are less significant but recognized contributors [25]. Weather Conditions, though generally uncontrollable, showed a CSI of 2.92, reflecting moderate significance. Adverse environmental conditions such as rain or high temperatures can lead to early setting or pumping issues, particularly when unanticipated.

Testing Waste, referring to concrete used for slump and cube testing, had the lowest CSI of 2.77. As an essential part of quality control, this category contributes minimally to overall waste, suggesting that attention should be directed more toward operational inefficiencies.

In conclusion, the findings clearly indicate that human-related factors—notably planning, workmanship, and handling—are more responsible for concrete waste than environmental or procedural aspects. Effective mitigation requires targeted efforts in project management, training and supervision, and equipment maintenance. Addressing these areas can lead to substantial reductions in material wastage and enhance overall construction efficiency.

4.2.2. Cause Analysis of Steel Waste

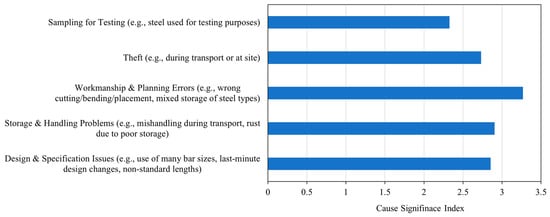

The cause significance index analysis of Construction and Demolition (C&D) steel waste reveals that workmanship and planning errors—such as incorrect cutting, bending, placement, or mixing of different steel types—are the most significant contributors, with the highest index value of 3.27 (Figure 10). This aligns with findings by Karunasena et al. [28] and Awan et al. [29], who emphasize the critical role of skilled labor and accurate planning in reducing steel waste. This is followed by storage and handling problems (2.91), including damage during transport and rusting due to improper storage, consistent with Gupta et al. [24] who discuss material management vulnerabilities. Design and specification issues (2.85), such as the use of multiple bar sizes, last-minute design changes, and non-standard lengths, lead to material wastage as also observed by Bonifazi et al. [4]. Theft of steel during transport or at the construction site (2.73) poses a considerable loss, while sampling for testing purposes (2.33) has the least impact but still contributes to overall waste generation. These findings collectively highlight the need for improved planning, quality control, and site management to minimize steel wastage in construction projects [24,28].

Figure 10.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) illustrating key contributors to steel waste.

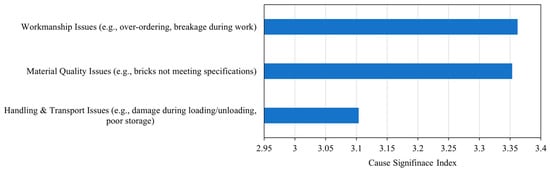

4.2.3. Cause Analysis of Masonry Waste

The relative importance index (RII) analysis of brick masonry-related C&D waste indicates that workmanship issues—such as over-ordering of materials and breakage during construction—are the most significant cause, with the highest RII value of 3.36 (Figure 11). Closely following are material quality issues (3.35), where bricks fail to meet the required specifications, leading to rejection and waste. Handling and transport issues (3.10), including damage during loading, unloading, and improper storage at the site, also contribute notably to brick masonry waste. These results align with recent findings by Shajidha et al. [21] and Gupta et al. [24], which emphasize that improving on-site practices, ensuring quality control during procurement, and adopting better handling and storage methods can substantially reduce brick-related construction waste.

Figure 11.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) highlighting primary causes of brick masonry waste.

4.2.4. Cause Analysis of Cement Mortar Waste

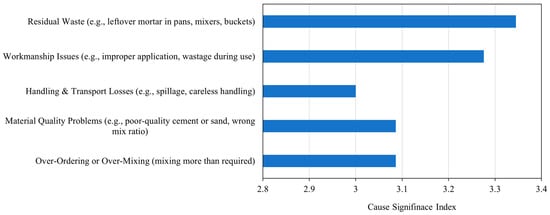

The Cause Significance Index (CSI) analysis of cement mortar (Figure 12) waste shows that residual waste—such as leftover mortar remaining in pans, mixers, and buckets—is the leading contributor, with the highest CSI value of 3.34. This is followed by workmanship issues (3.28), including improper application techniques and wastage during use, which significantly increase material loss. Over-ordering or over-mixing and material quality problems share the same CSI value of 3.09, indicating that preparing more mortar than needed or using poor-quality cement, sand, or incorrect mix ratios also contribute to wastage. Handling and transport losses (3.00), such as spillage and careless handling during movement, further add to the problem. These findings are supported by recent research emphasizing the importance of accurate material estimation, proper mixing practices, quality control, and efficient on-site handling to minimize cement mortar waste in construction projects [30,31,32].

Figure 12.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) highlighting key contributors to cement mortar waste.

4.2.5. Cause Analysis of Wood Waste

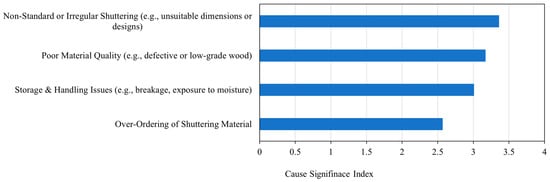

The Cause Significance Index (CSI) analysis of wood waste in construction and demolition (C&D) activities reveals that non-standard or irregular shuttering—such as the use of unsuitable dimensions or designs—is the most significant cause, with the highest CSI value of 3.36 (Figure 13). This is followed by poor material quality (3.17), where defective or low-grade wood leads to premature damage or rejection. Storage and handling issues (3.01), including breakage during movement and deterioration due to moisture exposure, also contribute substantially to waste generation. Over-ordering of shuttering material (2.57) has the least impact but still results in excess material that may not be reused effectively. These findings are consistent with recent studies emphasizing that addressing issues of design standardization, material quality control, and proper handling and storage can greatly reduce wood waste in construction projects [33,34].

Figure 13.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) highlighting key contributors to wood waste.

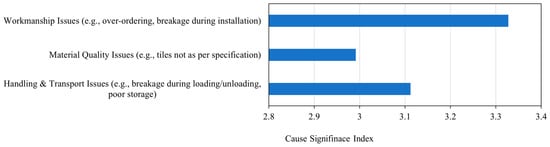

4.2.6. Cause Analysis of Tile Waste

The Cause Significance Index (CSI) analysis of tile waste in construction shows that workmanship issues—such as over-ordering and breakage during installation—are the most significant cause, with the highest CSI value of 3.33 (Figure 14). This is followed by handling and transport issues (3.11), where tiles are damaged during loading, unloading, or due to improper storage at the site. Material quality issues (2.99), including tiles not meeting specifications, also contribute to waste, though to a slightly lesser extent. These findings highlight the need for skilled installation practices, careful material handling, and strict quality checks during procurement to effectively minimize tile waste in construction projects.

Figure 14.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) highlighting key contributors to tile waste.

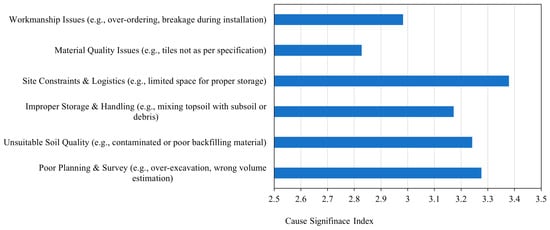

4.2.7. Cause Analysis of Soil Waste

The analysis of soil waste generation in construction indicates that the most critical factor is poor planning and survey, with 30.2% of respondents rating it as significant and 23.3% as highly significant (Figure 15). This includes errors such as over-excavation and inaccurate volume estimation, which directly lead to excess soil waste. Unsuitable soil quality—like contaminated or poor backfilling material—was also a major contributor, with 36.2% rating it as significant. Improper storage and handling, including mixing topsoil with subsoil or debris, had similar trends, with 33.6% marking it as significant. Site constraints and logistics, such as limited space for proper soil storage, were considered a notable issue by 27.6% of respondents, though a higher percentage (24.1%) found it only moderately significant. Interestingly, material quality issues and workmanship issues were generally perceived as less critical for soil waste compared to other causes, with lower “highly significant” ratings of 10.3% and 12.9%, respectively.

Figure 15.

Cause Significance Index (CSI) highlighting key contributors to soil waste.

These outcomes align with contemporary studies highlighting the critical role of meticulous project planning, enhanced surveying accuracy, and effective practices in storage, handling, and soil quality control to significantly reduce soil waste generation during construction activities [35,36].

4.3. Minimization of Construction and Demolition Waste

This section presents the analysis of construction and demolition (C&D) waste minimization strategies, structured across major material categories, namely concrete, steel, masonry, cement mortar, wood, tiles, and soil. The findings are based on survey data and analysed using the Relative Importance Index (RII) method to prioritise the perceived significance of different minimization techniques. Each subsection highlights the most effective strategies for reducing material wastage, supported by percentage ratings from respondents and comparative RII scores.

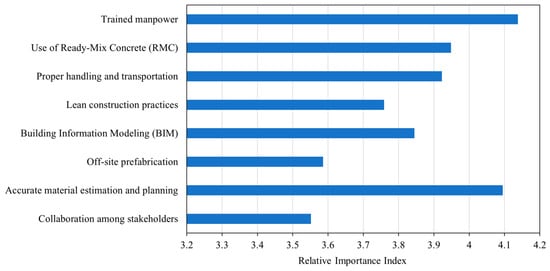

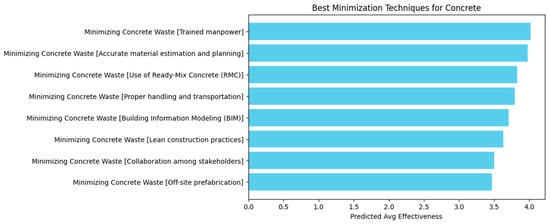

4.3.1. Minimization of Concrete Waste

The analysis of minimization strategies for concrete waste highlights several key measures with varying degrees of perceived significance and relative importance (Figure 16). Trained manpower emerged as the most critical factor, with the highest RII value of 4.14 and 50% of respondents rating it as highly significant. Skilled personnel ensure proper mixing, placement, and curing, thereby reducing errors and waste. Accurate material estimation and planning ranked second (RII = 4.09), with nearly half (49.1%) rating it highly significant, underscoring the importance of precise quantity calculations and scheduling to avoid over-ordering or under-utilisation of concrete.

Figure 16.

Relative Importance Index (RII) of strategies to minimize concrete waste.

Use of Ready-Mix Concrete (RMC) (RII = 3.95) and proper handling and transportation (RII = 3.92) were also rated highly, reflecting their role in minimising wastage due to on-site mixing errors, spillage, and premature setting. Building Information Modeling (BIM) (RII = 3.84) and lean construction practices (RII = 3.76) were recognised as effective modern approaches, improving coordination, reducing rework, and optimising resource use. Off-site prefabrication (RII = 3.59) was considered moderately to highly significant, benefiting waste reduction through precision manufacturing in controlled environments.

Finally, collaboration among stakeholders (RII = 3.55) was identified as an important but slightly lower-ranked factor, suggesting that effective communication and coordination between designers, contractors, and suppliers can still play a vital supporting role in waste minimization. Overall, the results indicate that a combination of technical measures, skilled workforce, and advanced planning tools is essential to significantly reduce concrete waste in construction projects [37,38].

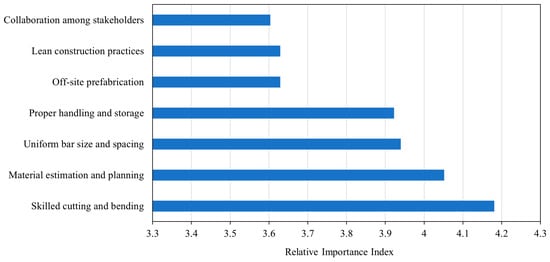

4.3.2. Minimization of Steel Rebar Waste

Figure 17 shows the analysis of steel rebar waste minimization strategies indicating that skilled cutting and bending is the most critical factor, achieving the highest RII value of 4.18, with half of the respondents rating it as highly significant. Precision in cutting and bending reduces off-cuts, rework, and material rejection, directly lowering wastage [28,29]. Material estimation and planning follows closely (RII = 4.05), where accurate quantity assessment and sequencing ensure steel is efficiently procured and utilized, minimizing surplus and scrap [24]. Uniform bar size and spacing (RII = 3.94) was also recognized as important, as standardization simplifies fabrication, reduces on-site alterations, and enhances reuse potential [4]. Proper handling and storage (RII = 3.92) plays a significant role in preventing damage, rusting, and contamination, ensuring steel remains fit for use throughout project duration [29]. Modern approaches such as off-site prefabrication and lean construction practices (both RII = 3.63) were considered moderately to highly significant, reflecting their potential to reduce waste through controlled manufacturing and optimized workflows [4]. Collaboration among stakeholders (RII = 3.60), while slightly lower-ranked, remains relevant for better coordination among designers, contractors, and suppliers to avoid design and supply mismatches [24]. Overall, minimizing steel rebar waste requires combining skilled workmanship, precise planning, standardization, efficient handling, complemented by modern construction practices and strong stakeholder coordination—ensuring material efficiency, cost savings, and sustainability in steel-intensive construction projects.

Figure 17.

Relative Importance Index (RII) of approaches to reduce steel rebar waste.

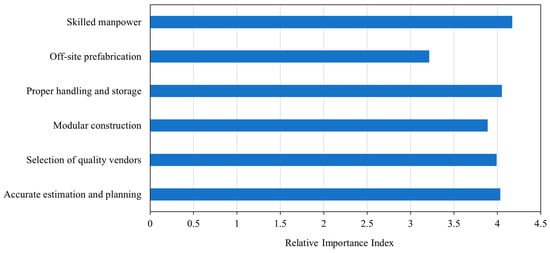

4.3.3. Minimization of Masonry Waste

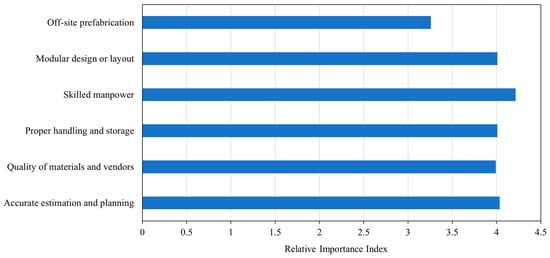

The analysis of brick masonry waste minimization measures shows that skilled manpower is the most crucial factor, with the highest RII value of 4.17 and 54.3% of respondents rating it as highly significant (Figure 18). Skilled workers help reduce breakage during handling and laying, ensure uniform mortar application, and optimize brick usage, thereby significantly reducing waste [21,24]. Proper handling and storage (RII = 4.05) ranks second, as careful transportation, stacking, and protection from environmental factors prevent material damage before use [4]. Accurate estimation and planning (RII = 4.03) play a vital role by aligning material orders closely with actual project requirements, avoiding both excess stock and shortages [24]. Selection of quality vendors (RII = 3.99) contributes to waste reduction by ensuring bricks meet strength and dimensional specifications, minimizing rejection and replacement [21]. Modern methods such as modular construction (RII = 3.89) further reduce waste by standardizing brick sizes and layout designs to match project dimensions, while off-site prefabrication (RII = 3.22), though less widely adopted, offers potential benefits in reducing on-site handling losses and improving quality control [4]. Overall, minimizing brick masonry waste requires a combination of skilled labor, precise planning, quality material sourcing, and efficient handling, complemented by modern construction techniques to achieve sustainable and cost-effective building practices.

Figure 18.

Relative Importance Index (RII) prioritizing masonry waste minimization techniques.

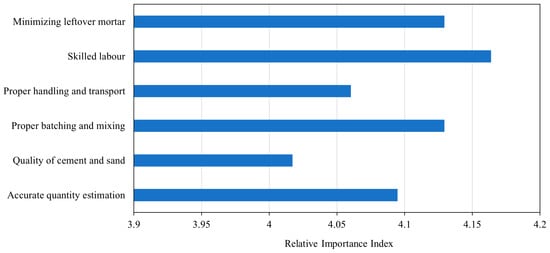

4.3.4. Minimization of Cement Mortar Waste

The analysis of cement mortar waste minimization strategies highlights skilled labour as the most influential factor (Figure 19), with the highest RII value of 4.16 and nearly half of the respondents (49.1%) rating it as highly significant. Skilled workers ensure correct application techniques, optimal mortar usage, and reduced losses during construction. Proper batching and mixing and minimising leftover mortar both follow closely (RII = 4.13), emphasizing the importance of preparing only the required quantity with the right proportions, thereby reducing waste from unused or expired mortar. Accurate quantity estimation (RII = 4.09) also plays a critical role in aligning material procurement with actual needs, avoiding over-preparation. Proper handling and transport (RII = 4.06) ensures protection from spillage, contamination, and premature setting during movement on-site. Additionally, quality of cement and sand (RII = 4.02) is essential for durable mortar performance, reducing rework and associated waste. Overall, minimizing cement mortar waste requires a well-trained workforce, precise material estimation, quality-controlled mixing, and careful handling, supported by measures to prevent leftover accumulation. These practices contribute not only to material reduction but also cost efficiency and sustainability in construction projects [30,31,32].

Figure 19.

Relative Importance Index (RII) highlighting critical measures to limit cement mortar waste.

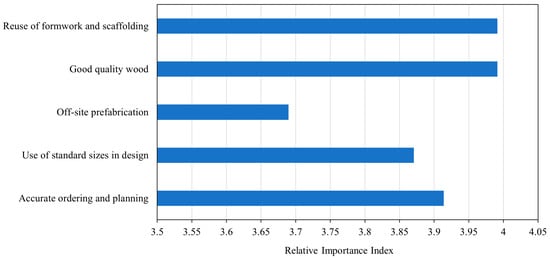

4.3.5. Minimization of Wood Waste

The analysis of wood waste minimization strategies reveals that using good quality wood and reusing formwork and scaffolding are the most impactful measures, both achieving the highest RII value of 3.99 (Figure 20). High-grade timber reduces damage, warping, and rejection during construction, while repeated use of formwork and scaffolding extends material lifespan, lowering demand for new wood and minimizing waste [33,34]. Accurate ordering and planning (RII = 3.91) is crucial for procuring only necessary quantities, reducing risks of surplus material degradation or waste [39]. Use of standard sizes in design (RII = 3.87) supports waste reduction by optimizing cutting patterns and minimizing off-cuts. Off-site prefabrication (RII = 3.69), though slightly lower in ranking, remains significant by enabling precise cutting, better quality control, and reduced on-site handling losses [33]. Overall, minimizing wood waste requires an integrated approach focusing on material quality, reuse practices, precise planning, standardized design, and prefabrication where feasible. These strategies reduce environmental impact and improve cost efficiency and resource utilization in construction projects.

Figure 20.

Relative Importance Index (RII) on wood waste mitigation strategies.

4.3.6. Minimization of Tile Waste

The analysis of tile waste minimization strategies indicates that skilled manpower is the most significant factor, with the highest RII value of 4.22 and over half of the respondents (54.3%) rating it as highly significant (Figure 21). Experienced workers can ensure accurate cutting, proper installation, and minimal breakage, directly reducing tile wastage. Accurate estimation and planning (RII = 4.03) ranks next in importance, helping to avoid over-ordering and ensuring optimal utilisation of tiles based on project requirements.

Figure 21.

Relative Importance Index (RII) of techniques for tile waste minimization.

Proper handling and storage and modular design or layout share the same RII value of 4.01, both contributing significantly to waste reduction. Careful transportation, stacking, and storage protect tiles from damage before installation, while modular layouts optimise cutting patterns and minimise off-cuts. Quality of materials and vendors (RII = 3.99) also plays an essential role by ensuring that tiles meet specifications, thereby reducing rejection rates.

Off-site prefabrication (RII = 3.26), though less common in tile works, can still help in specific applications by enabling precision cutting and assembly in controlled environments, thereby reducing on-site waste.

Overall, minimising tile waste requires a skilled workforce, precise planning, proper handling, quality materials, and design optimisation, with prefabrication as a supplementary measure where feasible. These integrated practices can significantly improve material efficiency, reduce costs, and support sustainable construction.

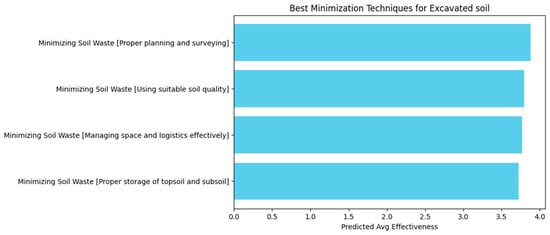

4.3.7. Minimization of Soil Waste

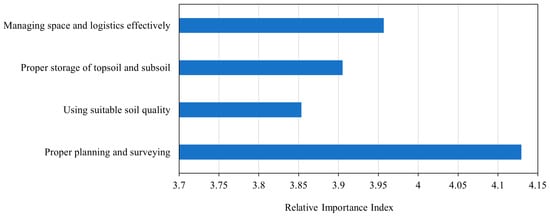

The analysis of soil waste minimization strategies shows that proper planning and surveying is the most significant measure, with the highest RII value of 4.13 and 48.3% of respondents rating it as highly significant (Figure 22). Accurate site surveys, excavation planning, and volume estimation help prevent over-excavation and unnecessary soil removal [39,40]. Managing space and logistics effectively (RII = 3.96) is critical, as well-organized site layouts and storage arrangements preserve soil for reuse rather than waste due to contamination or disposal [39]. Proper storage of topsoil and subsoil (RII = 3.91) prevents mixing or degradation of soil layers, maintaining suitability for landscaping, backfilling, or other applications. Using suitable soil quality (RII = 3.85) further supports waste minimization by ensuring soil meets project specifications, reducing rejection and disposal [40]. Overall, reducing soil waste requires a planning-led approach supported by effective logistics, careful handling, and quality control to ensure excavated soil is managed as a reusable resource [39].

Figure 22.

Relative Importance Index (RII) for effective soil waste management strategies.

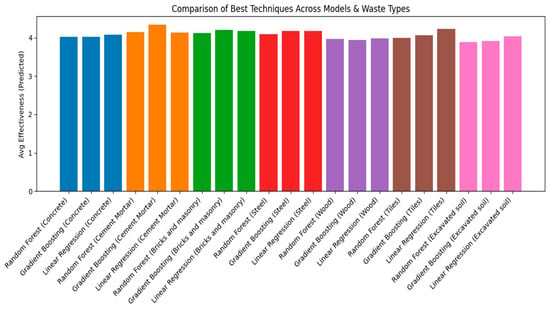

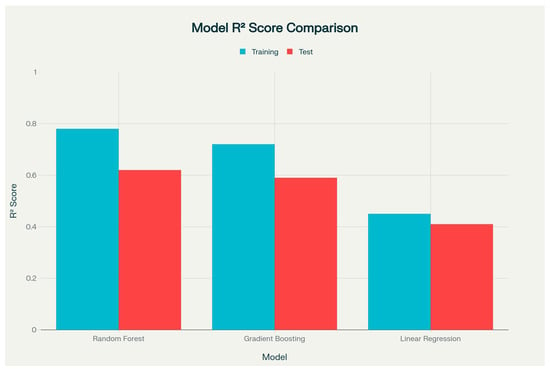

4.4. Analysis Machine Learning Models

To evaluate the robustness of waste minimization technique predictions, three machine learning models were applied: Random Forest Regressor, Gradient Boosting Regressor, and Linear Regression. Table 1 summarizes their prediction performances in terms of mean R2, with Random Forest achieving the highest accuracy (0.62), followed by Gradient Boosting (0.59), and Linear Regression (0.41).

Table 1.

Cross-validation performance metrics (5-fold CV) for machine learning models (MAE, RMSE, R2).

The Random Forest model was selected due to its ability to effectively handle categorical-to-numeric survey data, capture complex non-linear interactions among waste causes, amounts, and minimization methods, and provide feature importance insights, which aid interpretation of impactful techniques. Additionally, its robustness against noise and reduced risk of overfitting outperform simpler models [37,41,42].

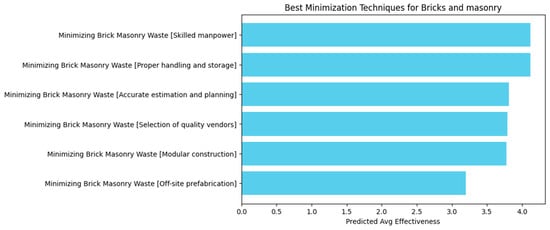

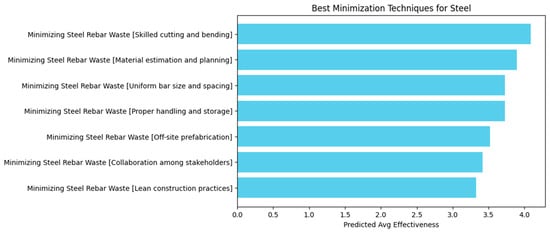

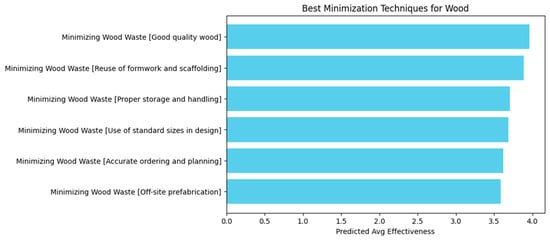

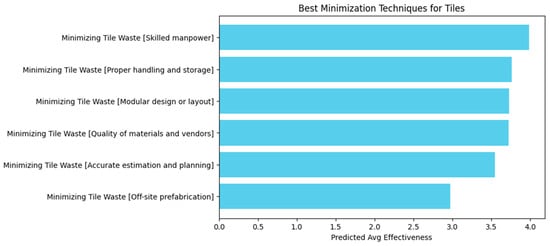

The modeling results corroborate the Relative Importance Index (RII) analysis presented earlier (Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29 and Figure 30). The best identified minimization techniques per waste type, with average effectiveness scores, are

Figure 23.

Comparison of machine learning models’ performance in predicting waste minimization effectiveness.

Figure 24.

Most effective minimization technique identified for concrete waste.

Figure 25.

Most effective minimization technique identified for cement mortar waste.

Figure 26.

Most effective minimization technique identified for bricks and masonry waste.

Figure 27.

Most effective minimization technique identified for steel waste.

Figure 28.

Most effective minimization technique identified for wood waste.

Figure 29.

Most effective minimization technique identified for tile waste.

Figure 30.

Most effective minimization technique identified for excavated soil waste.

- Concrete: Trained manpower (Avg = 4.02);

- Cement Mortar: Skilled labour (Avg = 4.14);

- Bricks and Masonry: Skilled manpower (Avg = 4.12);

- Steel: Skilled cutting and bending (Avg = 4.09);

- Wood: Good quality wood (Avg = 3.96);

- Tiles: Skilled manpower (Avg = 3.99);

- Excavated Soil: Proper planning and surveying (Avg = 3.88).

4.4.1. Comparison of Machine Learning Models

To strengthen the statistical validity of the model performance, 5-fold cross-validation was conducted for all three models. Cross-validation helps ensure that the results are not biased by a single train–test split and improves reliability. The following metrics were computed: Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and the mean cross-validation R2 (Table 1). The confidence intervals (95% CI) for the predicted minimization effectiveness scores were also included. These additional metrics confirm the robustness and generalizability of the Random Forest model, which outperformed the Gradient Boosting and Linear Regression models across all validation measures.

The inclusion of confidence intervals and cross-validation metrics provides additional statistical assurance regarding the stability and predictability of the selected Random Forest model.

4.4.2. Training vs. Testing Performance Analysis

To evaluate the generalization capability of the machine learning models, training and test R2 values were computed for Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Linear Regression (Table 2). The Random Forest model demonstrated minimal performance reduction between training and test sets, indicating good generalization. In contrast, the Linear Regression model exhibited notable underfitting, while the Gradient Boosting model displayed mild overfitting.

Table 2.

Cross-validation performance metrics (5-fold CV).

The training–test performance comparison highlights the robustness of the Random Forest model and supports its selection as the optimal model for predicting waste minimization strategies.

The grouped bar chart (Figure 31) clearly shows that Random Forest has the highest R2 scores for both training and test data, indicating strong predictive performance and relatively good generalization compared to the other models. Gradient Boosting comes next, with slightly lower R2 values, suggesting a bit more overfitting but still solid overall accuracy. Linear Regression has the lowest R2 on both training and test datasets, meaning it struggles to capture complex patterns in your data. The difference between training and test R2 for each model visualizes the extent of overfitting, with Linear Regression showing the smallest gap and Random Forest the largest, yet Random Forest maintains better performance overall.

Figure 31.

Comparison of training and test performance for Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and Linear Regression.

This alignment between data-driven modeling and expert survey assessments strengthens confidence that workforce skill, precise planning, quality control, and advanced technological practices are critical in minimizing C&D waste effectively [37].

5. Optimal Minimisation Techniques for Major C&D Waste Types

Table 3 provides a consolidated overview of the most effective minimisation techniques for major construction and demolition waste types, derived from both the Relative Importance Index (RII) analysis and machine learning model outputs. The table synthesises the top two to three strategies for each material category—such as concrete, steel, masonry, cement mortar, wood, tiles, and soil—along with their core benefits and practical implications. By presenting the key actions that significantly reduce material wastage, this summary offers a clear and actionable reference for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers aiming to enhance resource efficiency and promote sustainable construction practices.

Table 3.

Best Minimisation techniques for major construction and demolition waste types.

This integrated overview aligns with recognition from machine learning analysis, where these same top-rated techniques scored highest in effectiveness prediction models, reinforcing workforce skill, planning precision, and material handling as cornerstones for waste reduction in C&D projects [37,42].

6. Practical Implications of the Study

The practical and policy implications of the study highlight the urgent need for stricter enforcement and standardization of C&D waste management practices in line with India’s updated regulations under the C&D Waste Management Rule 2025. Practically, the findings advocate for integrating advanced waste minimization techniques, such as skilled labor training and use of modern construction technologies, into routine project management to reduce waste at source. Policy-wise, the results support the formulation of comprehensive incentive schemes for environmentally sustainable practices and mandatory compliance for all construction projects, particularly in urban development. Additionally, promoting awareness campaigns and establishing robust monitoring mechanisms can ensure adherence to regulations, ultimately facilitating a transition towards sustainable construction practices that align with India’s goals for environmental conservation and circular economy principles.

7. Conclusions

This study conducted a systematic assessment of construction and demolition (C&D) waste generation and corresponding minimization strategies within the Indian construction sector, based on empirical data obtained from 116 industry professionals representing all major managerial levels. The respondent profile demonstrated adequate diversity, with 43% from middle management, 57% possessing 6–20 years of experience, and 41.4% employed in building construction, thereby ensuring that the findings reflect a broad spectrum of practical expertise.

The analytical approach integrated exploratory statistical techniques with a machine-learning-based evaluation framework, enabling a robust identification of key waste-generating factors and the relative effectiveness of mitigation measures. Quantitative cause analysis revealed that poor planning and site management constituted the most significant contributor to concrete waste (CSI = 3.34), whereas workmanship deficiencies were most influential for steel waste (CSI = 3.27). Additionally, irregular shuttering practices were identified as the dominant factor affecting wood waste generation (CSI = 3.36).

Evaluation of minimization strategies demonstrated that skilled manpower consistently ranked as the most effective intervention across several waste categories, including concrete (average effectiveness = 4.02, RII = 4.14), brick masonry (avg = 4.12, RII = 4.17), cement mortar (avg = 4.14, RII = 4.16), and tiles (avg = 3.99, RII = 4.22). For steel waste, skilled cutting and bending operations emerged as the most impactful strategy (avg = 4.09, RII = 4.18), while enhanced planning and surveying procedures were identified as the most critical for soil waste minimization (avg = 3.88, RII = 4.13).

Collectively, these findings provide a quantitative evidence base for prioritizing waste-causing factors and selecting targeted, high-impact minimization strategies. The results offer valuable guidance for practitioners, policymakers, and researchers seeking to improve resource efficiency and promote sustainable construction practices in the Indian context.

However, limitations include reliance on self-reported survey data, which may introduce bias, and a focus on specific regions that may limit broader generalizability. Practical and policy implications align strongly with India’s Construction & Demolition Waste Management Rules 2025, emphasizing the need for strict enforcement of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), mandatory recycling targets, and integration of sustainable practices throughout project lifecycles. These rules mandate minimum recycled material use and promote accountability via digital tracking, fostering a circular economy. The study’s findings support policy directions to enhance workforce training, modernize construction practices, and develop robust infrastructure for C&D waste recycling and reuse, thus contributing to environmental sustainability and resource efficiency in India’s construction industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R.B. and C.G.S.; methodology, D.R.B. and A.K.P.; software, D.R.B.; formal analysis, C.G.S.; investigation, C.G.S., D.R.B. and S.K.P.; resources, C.G.S.; data curation, D.R.B. and S.K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.S.; writing—review and editing, D.R.B., S.K.P. and A.K.P.; visualization, D.R.B.; supervision, D.R.B.; project administration, D.R.B. and S.K.P.; Funding acquisition, S.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| C&D | Construction and Demolition |

| RII | Relative Importance Index |

| CSI | Cause Significance Index |

References

- Al-Numan, B.S.O. Construction industry role in natural resources depletion and how to reduce It. In Natural Resources Deterioration in MENA Region: Land Degradation, Soil Erosion, and Desertification; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.; Singhal, S.; Jain, N.K. Construction and demolition waste (C & DW) in India: Generation rate and implications of C & DW recycling. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2021, 21, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Sakthibala, R.K.; Vasanthi, P.; Hariharasudhan, C.; Partheeban, P. A critical review on recycling and reuse of construction and demolition waste materials. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 12, 100375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifazi, G.; Grosso, C.; Palmieri, R.; Serranti, S. Current trends and challenges in construction and demolition waste recycling. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 53, 101032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayhan, D.S.A.; Bhuiyan, I.U. Review of construction and demolition waste management tools and frameworks with the classification, causes, and impacts of the waste. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2024, 6, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, E.R.; El-Mahdy, G.M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Daoud, A.O. Analysis of factors affecting construction and demolition waste safe disposal in Egypt. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 70, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweis, G.J.; Hiari, A.; Thneibat, M.; Hiyassat, M.; Abu-Khader, W.S.; Sweis, R.J. Understanding the Causes of Material Wastage in the Construction Industry. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 15, 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhães, R.F.; Danilevicz, Â.d.M.F.; Saurin, T.A. Reducing construction waste: A study of urban infrastructure projects. Waste Manag. 2017, 67, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazmi, S.; Abdelmegid, M.; Sarhan, S.; Poshdar, M.; Gonzalez, V.; Bidhendi, A. An integrated framework to improve waste management practices and environmental awareness in the Saudi construction industry. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 10, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, A.B.; Gonçalves, A.F.; Martins, I.M. Construction and demolition waste generation and management in Lisbon (Portugal). Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragossnig, A.M. Construction and demolition waste—Major challenges ahead! Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 345–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament & Council. Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives (European Waste Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L 312, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dainty, A.R.; Brooke, R.J. Towards improved construction waste minimisation: A need for improved supply chain integration? Struct. Surv. 2004, 22, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, C.; Teicholz, P.; Sacks, R.; Liston, K. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, B. BIM and Construction Management: Proven Tools, Methods, and Workflows, 1st ed.; Wiley Publish, Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, N.; Dinesen, B. Building Information Modelling: Construction the Business Case; British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nagalli, A. Estimation of construction waste generation using machine learning. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Waste Resour. Manag. 2021, 174, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, X. Machine learning in construction and demolition waste management: Progress, challenges, and future directions. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, C.G.; Biswal, D.R.; Udgata, G.; Pradhan, S.K. Estimation, Classification, and Prediction of Construction and Demolition Waste Using Machine Learning for Sustainable Waste Management: A Critical Review. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElshabElshaboury, N.; Al-Sakkaf, A.; Mohammed Abdelkader, E.; Alfalah, G. Construction and Demolition Waste Management Research: A Science Mapping Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shajidha, H.; Gupta, S.; Kumar, R. Sustainable waste management in the construction industry: Focusing on masonry waste reduction strategies. Front. Sustain. Cities 2025, 7, 1582239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, R.; Arul, T.; Ashfaq, S. A mixed-methods study of sustainable construction practices. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 430, 139087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, A.; Lonergan, M.; Huang, T.; Azghadi, M.R. Analyzing mixed construction and demolition waste using advanced data-driven methods. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 217, 108218. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Jha, K.N.; Vyas, G. Construction and demolition waste causative factors in building projects: Survey of the Indian construction industry experiences. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2024, 24, 432–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, Z.; Nan, C. Concrete construction waste pollution and relevant recycling measures. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2020, 19, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Hosny, S.; Ahmed, Y.; Hussien, A. Causes of Reinforced Concrete Materials Waste in Construction Projects. Egypt. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2022, 40, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.-Y.; Cade, W.; Behdad, S. Circular economy of construction and demolition waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 171, 105609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunasena, G.; Gurmu, A.; Shooshtarian, S.; Udawatta, N.; Ranthika Perera, C.S.; Maqsood, T. Effect of construction defects on construction and demolition waste management in building construction: A systematic literature review. Integr. Environ. Assess Manag. 2025, 21, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Melhem, N.N.; Maher, R.A.; Sundermeier, M. Waste-based management of steel reinforcement cutting in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, A.H.M.M.; Abass, M.A.A. The Effects of Waste Materials on Cement Mortar Properties [Case Study: Fly Ash and Cement Dust]. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokareva, A.; Waldmann, D. Durability of cement mortars containing fine demolition wastes as supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 477, 141316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, Y.M.; Elamary, A.S.; Abo-El-Wafa, W. Performance of plain concrete and cement blocks with cement partially replaced by cement kiln dust. Materials 2021, 14, 5647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H.; Ahmadi, Z.; Hashemi, E.; Talebi, S. A review of the circular economy approach to the construction and demolition wood waste: A 4 R principle perspective. Clean. Waste Syst. 2025, 11, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alwis, A.M.L.; Bazli, M.; Arashpour, M. Automated recognition of contaminated construction and demolition wood waste using deep learning. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMS India. Construction Waste Reduction: Strategies for a Sustainable Future. 2025. Available online: https://amsindia.co.in/construction-waste-reduction/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- ONIndus. Construction Waste Management: Strategies for a Sustainable Future. 2025. Available online: https://www.onindus.com/construction-waste-management/ (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Mohammad, A.H. Management practice strategies across all project stages. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2025, 17, 10850. Available online: https://etasr.com/index.php/ETASR/article/view/10850 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Bamisaye, M.E.; Ajayi, B.O.; Sereewatthanawut, I. Sustainable waste management of construction materials: Mathematical modelling and analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 27, 200274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, S.; Lundberg, K.; Svedberg, B.; Knutsson, S. Sustainable management of excavated soil and rock in urban areas–a literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 93, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enva.com. How Contaminated Soil Affects Construction Projects. Environmental Case Studies. 2025. Available online: https://enva.com/case-studies/contaminated-soil-in-construction-projects (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Lafebre, H.; Songonuga, O.; Kathuria, A. Contaminated soil management at construction sites. Pract. Period. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste Manag. 1998, 2, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, G.-W.; Choi, S.-H.; Hong, W.-H.; Park, C.-W. Development of Machine Learning Model for Prediction of Demolition Waste Generation Rate of Buildings in Redevelopment Areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).