Abstract

As destinations featured in films and television programs attract growing numbers of tourists, exploring the factors that sustain film tourists’ loyalty and advocacy has become increasingly important. This study explores the determinants of post-visit behaviors through the lens of cognitive appraisal theory (CAT), investigating how perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction shape revisit and word-of-mouth (WOM) intentions among 436 Chinese film tourists visiting Thailand. Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to capture both symmetrical and configurational effects. The SEM results reveal that perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction significantly enhance WOM intentions. The complementary fsQCA findings reveal multiple causal pathways leading to high revisit and WOM intentions. The study advances theoretical understanding by demonstrating the applicability of CAT to film tourism and showing how tourists’ cognitive evaluations and emotional appraisals jointly shape their post-visit behavioral intentions. The findings also offer practical guidance for developing authenticity-based strategies to foster loyalty and positive destination advocacy.

Keywords:

authenticity; perceived value; satisfaction; revisit intentions; word-of-mouth; film tourism; SEM; fsQCA 1. Introduction

Watching films and television (TV) series is one of the most common leisure activities worldwide, offering audiences entertainment, escapism, and emotional engagement (Irimiás et al., 2021). As viewers immerse themselves in fictional narratives, they develop strong connections with the characters and the settings depicted on screen (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023). This emotional connection often translates into a desire to visit the destinations featured in their favorite films or TV series, contributing to the rise of film tourism (D. Shi et al., 2024). Film tourism occurs when audiences extend their media consumption into travel experiences, visiting real-world destinations that have been depicted in audio–visual media as a form of leisure engagement (Teng & Chen, 2020). With the expansion of streaming platforms, audiences are repeatedly exposed to on-screen characters and locations, strengthening their emotional attachment and influencing their travel choices (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023). This constant exposure enhances their familiarity with on-screen destinations, increasing the likelihood of translating their virtual engagement into actual visitation (Vila et al., 2021). Consequently, film tourism has become an increasingly significant sector within the tourism industry, offering destinations new opportunities for place marketing and economic growth (Wu & Lai, 2023). Many destinations have capitalized on this trend by promoting film-related sites, creating guided tours, and integrating cinematic themes into their marketing campaigns (St-James et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021).

According to Yao and Yang (2024), the release of popular films and TV series often leads to a significant surge in tourist arrivals and online search activity related to the filming locations. However, once audience enthusiasm fades, maintaining the destination’s reputation and sustaining tourist interest become critical challenges for film-related destinations. Therefore, it is essential to identify the key determinants that shape film tourists’ post-visit behaviors, particularly their revisit and word-of-mouth (WOM) intentions. Understanding these factors will enable tourism stakeholders to formulate strategies that improve film tourists’ experiences and foster long-term engagement with film-related destinations (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023).

Among the key elements influencing film tourists’ perceptions and evaluations, authenticity plays a crucial role in shaping their cognitive and emotional responses to film-related destinations (Li et al., 2021; Teng & Chen, 2020). Perceived authenticity refers to the extent to which a destination or site is seen as genuine (Kolar & Zabkar, 2010). It serves as a powerful motivator for tourists seeking meaningful experiences (Wareebor et al., 2025). Prior studies in cultural and heritage tourism have consistently identified authenticity as a critical determinant of perceived value (e.g., Atasoy & Eren, 2023), tourist satisfaction (e.g., Yildiz et al., 2024), and behavioral intentions (e.g., Park et al., 2019). However, despite the growing academic and practical interest in film tourism as a form of cultural tourism (Marin et al., 2021), limited research has examined how authenticity shapes film tourists’ perceived value, satisfaction, revisit intentions, and WOM intentions. This gap calls for a deeper understanding of how perceived authenticity affects the film tourists’ post-visit behavioral intentions.

To address the research gap, this study applies cognitive appraisal theory (CAT) as its theoretical foundation (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). CAT posits that individuals evaluate experiences through a cognitive appraisal process, which elicits emotional responses and ultimately shapes behavioral reactions (Bagozzi, 1992). Applying CAT in the context of film tourism allows for a comprehensive understanding of how tourists’ cognitive evaluations of authenticity shape their emotional responses and behavioral reactions, including revisit and WOM intentions.

Moreover, previous film tourism research has predominantly employed symmetrical analytical methods, such as structural equation modeling (SEM), to investigate direct and linear relationships between variables (e.g., Teng & Chen, 2020; Li et al., 2021). While these approaches are useful for identifying net effects, they often overlook the complex and configurational nature of tourist behavior, where multiple combinations of factors can result in the same outcome (Han et al., 2025). To overcome this limitation, this study applies fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA), an asymmetric method that identifies both necessary and sufficient conditions for outcomes (Rasoolimanesh et al., 2022). fsQCA complements traditional quantitative techniques by capturing the causal complexity inherent in tourism behavior and identifying multiple pathways that can lead to similar post-visit intentions (Cifci et al., 2023).

Accordingly, this research aims to investigate how perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction influence film tourists’ revisit and WOM intentions. In particular, it aims to address the following research questions:

- (1)

- Does perceived authenticity influence film tourists’ perceived value and satisfaction?

- (2)

- Do perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction significantly influence film tourists’ revisit and WOM intentions?

- (3)

- What combinations of factors lead to high levels of revisit and WOM intentions?

By applying CAT to develop a conceptual framework and integrating SEM with fsQCA, the study advances the theoretical understanding of film tourism behavior and provides empirical evidence of the complex interrelationships among perceived authenticity, perceived value, satisfaction, and post-visit intentions. The findings offer theoretical contributions to the film tourism research and practical guidance for destination managers and marketers seeking to improve authenticity-based experiences and foster long-term tourist engagement.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Authenticity in Film Tourism

Authenticity has been a core concept in tourism studies since MacCannell (1973) first introduced it as a crucial element in understanding tourist behavior. Despite its broad use, the concept of authenticity remains inconsistent and context-dependent (T. Zhang & Yin, 2020; Nguyen, 2020). In cultural tourism studies, Kolar and Zabkar (2010) defined authenticity as “tourists’ enjoyment and perceptions of how genuine are their experiences” (p. 655). Authenticity in the context of heritage tourism is intimately related to acknowledging and preserving the extraordinary worth of world heritage assets (Qu et al., 2024). The pursuit of authentic experiences has been recognized as an important motivator for tourists in selecting travel destinations (Manley et al., 2023; Wareebor et al., 2025; Zhao & Li, 2023). Consequently, preserving authenticity has become essential and is frequently utilized as an effective marketing tool (Nguyen & Cheung, 2016; Qu et al., 2024).

Wang (1999) identified three key forms of authenticity that have become central to tourism studies: objective, constructive, and existential authenticity. Objective authenticity pertains to the inherent properties of toured objects and can be evaluated using absolute and verifiable criteria (Wang, 1999). In contrast, constructive authenticity is a kind of authenticity that emerges through social constructs, shaped by the beliefs, imaginations, and expectations of tourists and tourism producers (Mkono, 2012; Wang, 1999). Existential authenticity, distinct from object-related authenticity, focuses on personal experiences and states of being. It emphasizes self-fulfillment and identity exploration through tourism activities, often independent of the physical authenticity of the destination or objects (Wang, 1999). Drawing on the multidimensional concept of authenticity, prior research emphasizes that constructive and existential authenticity are grounded in subjective evaluations, reflecting individual interpretations rather than objective measures (Zhou et al., 2023). Consequently, understanding how to measure tourists’ perceived authenticity and developing context-specific assessment criteria are essential.

Regarding film tourism, prior research has demonstrated that tourists who are induced to explore destinations depicted in their favorite films or TV series actively seek authentic film tourism experiences (Teng & Chen, 2020; Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023). These tourists often view their travels as a form of pilgrimage, where visiting film-related destinations becomes a meaningful activity (Buchmann et al., 2010; Gómez-Morales et al., 2022). For instance, photographing oneself while re-enacting iconic scenes is a prevalent means through which film tourists interact with filming sites and relive memorable cinematic experiences (St-James et al., 2018). In recent years, the increasing number of travelers visiting locations featured in films or TV programs to confirm the notion, “We’ve seen it in the movies, let’s see if it’s true” (Bolan et al., 2011, p. 102), has intensified scholarly and industry interest in understanding how authenticity shapes film tourism experiences (Li et al., 2021; Teng & Chen, 2020). Film-related destinations refer to sites or locations that have served as filming sites or are closely connected to film production (Hao et al., 2024). These locations are often simulations, constructed, or altered for cinematic purposes (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023), which may conflict with the notion of authenticity. Despite this, authenticity remains a crucial element of film tourism (Teng & Chen, 2020).

Buchmann et al. (2010), in their case study of film tourism in New Zealand inspired by The Lord of the Rings films, revealed that actual visits can blur the boundary between fantasy and reality. Similarly, Li et al. (2021) conducted research using the Game of Thrones series as a case study, indicating that film tourists perceive both actual film locations and the story’s setting locations as authentic. As such, even when tourists are aware that a destination is not the “real” film set, they can still perceive the film-related destination as authentic based on their prior viewing experiences, emotional connections, and on-site leisure activities (Buchmann et al., 2010; S. Zhang & Lo, 2024). Extant research (e.g., Li et al., 2021; Teng & Chen, 2020; Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023), thus, has widely applied constructive and existential authenticity to measure film tourists’ perceived authenticity at film-related destinations. However, as noted by Buchmann et al. (2010), even subjective evaluations of authenticity rely on some degree of objective authenticity. While existential authenticity focuses on activity-based experiences, it must still be grounded in a sense of reality, as destinations overwhelmed by artificial elements may fail to resonate with tourists’ expectations (Zhou et al., 2023). Therefore, this study adopts Wang’s (1999) multidimensional framework, incorporating objective, constructive, and existential authenticity, to measure film tourists’ perceptions of their experiences at film-related destinations.

2.2. Overall Perceived Value

Perceived value is widely recognized as a fundamental concept in marketing research due to its strong influence on consumer decision-making and behavioral intentions (Cronin et al., 2000). It generally reflects an individual’s evaluation of a product or service by comparing the benefits received with the costs or efforts incurred (Zeithaml, 1988). In the tourism context, perceived value represents tourists’ overall assessment of a destination based on the balance between the experiences or benefits obtained and the resources expended during their visit (Phi et al., 2024; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2015). Typically, perceived value is primarily shaped by tourists’ subjective judgment; therefore, it varies between tourists, between cultures, and over time (Atasoy & Eren, 2023; Fu et al., 2018). Understanding perceived value benefits tourism operators by shedding light on tourists’ satisfaction with their travel experiences and predicting tourists’ behavioral intentions toward a destination (C.-F. Chen & Chen, 2010; Jeong & Kim, 2020; Ramseook-Munhurrun et al., 2015).

Prior studies have revealed that authenticity significantly impacts tourists’ perceived value (Atasoy & Eren, 2023; S. Lee & Phau, 2018). In experiential consumption context, the authenticity of souvenirs serves as an antecedent to perceived value, thereby influencing tourists’ intentions to repurchase such souvenirs (Fu et al., 2018; Lin & Wang, 2012). In addition, S. Lee and Phau (2018) identified that both object-based authenticity and existential authenticity positively influence the overall perceived value of a cultural heritage destination. Yet, the significance of authenticity on overall perceived value within film tourism context is still not well explored. To extend the existing knowledge, it would be postulated that:

H1:

Perceived authenticity positively influences overall perceived value in film tourism experiences.

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction

Satisfaction has long been a central concept in both marketing and tourism studies (Jeong & Kim, 2020; Lu et al., 2015). It generally refers to the degree of positive emotion a consumer experiences following the use of a product or service (Rust & Oliver, 1994). Regarding the leisure and tourism context, satisfaction arises when a destination, tourism product, or travel experience meets the tourist’s expectations (C.-F. Chen & Chen, 2010; S. Lee & Phau, 2018). Hence, tourist satisfaction is a crucial assessment tool for evaluating travel experiences because it significantly impacts tourists’ destination decision-making and post-visit behavioral intentions (Baghirov et al., 2025; Lu et al., 2015).

The literature on psychology and behavior provides valuable insights into understanding tourist satisfaction. According to CAT, satisfaction can be conceptualized as an emotional response arising from cognitive evaluations of tourist experiences (Taylor et al., 2018). Building on this, previous tourism studies have extensively examined the interplay between satisfaction and various variables, with a substantial body of research highlighting the strong association between perceived value and satisfaction across diverse tourism contexts (e.g., S. Lee & Phau, 2018; Jeong & Kim, 2020). Consequently, this research posits that film tourists are more likely to be satisfied when they perceive greater value in a film-related destination. We thus hypothesize that:

H2:

Overall perceived value positively influences satisfaction with film tourism experiences.

Perceived authenticity is commonly viewed as having an evaluative judgment nature (Nguyen & Cheung, 2016). In the marketing and tourism fields, several studies have posited authenticity as a form of cognitive appraisal (Jiang, 2020; Song et al., 2025; J.-H. Kim et al., 2020). For instance, J.-H. Kim et al. (2020) demonstrated that perceived authenticity serves as an antecedent to positive emotional responses in a restaurant context. Consistent with CAT (Lazarus, 1991), such appraisals can trigger emotional outcomes, including satisfaction. Recently, there has been a growing body of empirical studies indicating that authenticity predicts tourist satisfaction in the cultural heritage context (Domínguez-Quintero et al., 2020; Yildiz et al., 2024). However, the relationships between film tourists’ perceived authenticity and satisfaction in the context of film tourism remain unclear and are yet to be investigated. Thus, the following hypothesis is established:

H3:

Perceived authenticity positively influences satisfaction with film tourism experiences.

2.4. The Antecedents of Revisit Intentions and WOM Intentions

Revisit and WOM intentions are two critical post-consumption behavioral responses that indicate a tourist’s long-term engagement with a destination (Nazarian et al., 2024). Revisit intentions refer to a tourist’s likelihood of returning to a previously visited destination, while WOM intentions involve the willingness to recommend the tourism destination to others (Fu et al., 2018; Y. Zhang et al., 2025). From a destination management perspective, encouraging repeat visits is cost-effective, as retaining previous tourists requires significantly less investment than attracting new tourists (Baghirov et al., 2025). Meanwhile, WOM plays a vital role in influencing travel decisions, as tourists often rely on recommendations from others when choosing destinations (Abubakar et al., 2017). Unlike commercial marketing efforts, WOM is considered more credible because it is based on real tourist experiences and shared without promotional intent (Zheng et al., 2025). Thus, identifying the key elements that influence revisit and WOM intentions is crucial for tourism managers looking to sustain visitor interest and attract new tourists.

Prior research has identified perceived value and satisfaction as key antecedents of tourist revisit and WOM intentions (Hosany et al., 2017; Baghirov et al., 2025; Phi et al., 2024). When tourists perceive greater value in their experiences, they are more inclined to hold positive evaluations and remain loyal to the destination (Atasoy & Eren, 2023). Similarly, satisfaction reflects a tourist’s emotional reaction to the overall experience, which is a well-established predictor of future behavioral intentions (Hosany et al., 2017). Grounded in CAT, when tourists appraise their experiences positively, they are more inclined toward favorable behavioral outcomes, such as revisiting the destination or recommending it to others (Atasoy & Eren, 2023).

Beyond perceived value and satisfaction, authenticity has emerged as a crucial factor influencing post-visit behaviors, particularly in niche tourism contexts such as cultural heritage and film tourism (Bryce et al., 2015; Li et al., 2021). Within the CAT framework, authenticity functions as a positive cognitive appraisal in which tourists assess the congruence between their media-induced expectations and the reality of the destination (Teng & Chen, 2020; Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023). When this appraisal is favorable, it triggers positive emotional responses that increase tourists’ willingness to engage in subsequent behavioral outcomes (Atasoy & Eren, 2023; Song et al., 2025). Prior studies further demonstrate that such cognitive evaluations play a direct role in shaping tourist behaviors across various tourism contexts (e.g., Sohn et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2023). However, the role of authenticity in enhancing revisit and WOM intentions remains inconclusive, and prior research has not fully examined how these two behavioral outcomes may operate differently within film tourism contexts.

A growing body of tourism and hospitality literature provides substantial empirical support for the view that WOM intentions act as an important antecedent to revisit intentions (Abubakar et al., 2017; Nazarian et al., 2024). According to Juliana et al. (2025), positive WOM reflects tourists’ attitudinal commitment and emotional connection to a destination, signaling a deeper level of satisfaction and psychological engagement. Therefore, tourists who actively recommend a destination often reinforce their own positive evaluations through the act of sharing, which subsequently strengthens their intention to return (Abubakar et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the specific influence of WOM on film tourists’ revisit intentions has not yet been fully established, particularly within film tourism contexts.

To address the research gaps, the study posits the following hypotheses:

H4:

Perceived authenticity positively influences revisit intentions among film tourists.

H5:

Overall perceived value positively influences revisit intentions among film tourists.

H6:

Satisfaction positively influences revisit intentions among film tourists.

H7:

Perceived authenticity positively influences WOM intentions among film tourists.

H8:

Overall perceived value positively influences WOM intentions among film tourists.

H9:

Satisfaction positively influences WOM intentions among film tourists.

H10:

WOM intentions positively influence revisit intentions among film tourists.

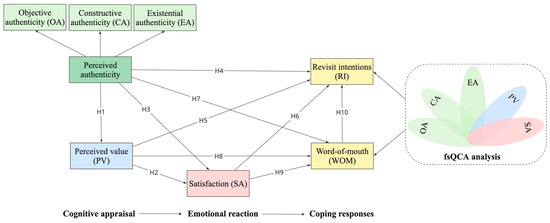

Based on CAT and the hypotheses developed in the preceding discussion, Figure 1 presents the proposed conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework based on cognitive appraisal theory (CAT).

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative research design using a structured questionnaire to examine the determinants of post-visit behavioral intentions among Chinese film tourists visiting Thailand. Data were collected through an online survey distributed to individuals who had traveled to Thailand after being inspired by Thai films or TV productions. Given the dispersed nature of this population and the difficulty of distinguishing film tourists from general travelers at destinations, online recruitment was considered the most effective and feasible strategy (Teng & Chen, 2020). Prior studies similarly highlight that online platforms offer efficient access to geographically dispersed and niche groups, facilitating rapid, cost-effective data collection with strong response potential (Evans & Mathur, 2005).

To enhance response accuracy and ensure reliable recall of film-induced travel experiences, screening criteria were implemented. Participants were required to have visited a film-related site in Thailand within the past six months. This timeframe aligns with recommendations in tourism and behavioral research, which emphasize that shorter recall periods reduce memory decay and enhance data quality, as recall bias increases significantly beyond six months (Tourangeau et al., 2000; Agapito et al., 2017). Although a shorter recall window could further reduce recall bias, a six-month criterion represents a practical compromise between improving memory accuracy and securing an adequate sample for a relatively niche group such as film tourists. Similar media-related tourism studies have adopted a six-month inclusion window to ensure recent experience while maintaining feasible recruitment (Ba & Song, 2022; Balaskas et al., 2025)

3.2. Study Setting and Data Collection

The research focused on Thailand as the study setting, with Chinese film tourists as the target population. In recent years, Thai films and TV dramas have become increasingly popular across Asia, particularly among Chinese viewers (Jirattikorn, 2021). Previous research indicates that such screen productions have significantly contributed to the growth of Thailand’s tourism sector by increasing Chinese audiences’ awareness and understanding of Thai culture and society (Y. Shi, 2020; Jiang et al., 2018). In recent decades, many Thai TV series have sparked substantial discussion and garnered praise among Chinese audiences, consequently attracting a significant influx of film tourists to the filming locations (Jiang et al., 2018; D. Shi et al., 2024). Thus, the population for this study comprises Chinese film tourists who have been influenced by Thai films or TV programs to visit film-related destinations in Thailand.

Since the target population comprised Chinese tourists, data were collected using an online questionnaire distributed through SoJump, a well-known survey platform in China (X. Chen & Chen, 2020). A self-administered questionnaire survey was developed, employing a convenience sampling method to recruit respondents. This non-probability sampling approach was considered appropriate for accessing a specific and information-rich group that is difficult to identify within broader tourist populations. Film tourists are typically embedded within the general tourist stream, making on-site recruitment or probability-based sampling impractical (Wen et al., 2018; Teng & Chen, 2020). Additionally, the overall population size of Chinese film tourists is unknown and cannot be systematically enumerated, further supporting the use of convenience sampling. While this approach enabled efficient access to the target group, it may introduce sampling bias, as individuals who are more active on social media or more interested in film tourism could be overrepresented. Although this limitation means the sample may not fully represent the broader population, convenience sampling remains appropriate for quantitative research involving hard-to-identify populations, and the screening criteria helped ensure the relevance and quality of the responses (Farrokhi & Mahmoudi-Hamidabad, 2012; Juliana et al., 2025).

The survey link and QR code were shared on various social media platforms in China to reach the target population. Screening questions were included to ensure participants met specific eligibility criteria: they must be of Chinese nationality, aged 18 years or older, and have visited film-related locations in Thailand within the past six months after being influenced by Thai films or TV productions.

A pilot survey was administered to 70 respondents through the SoJump platform to assess the clarity, validity, and reliability of the measurement items. Following satisfactory results, the formal data collection was carried out between November 2024 and February 2025. After collecting the responses, 28 invalid submissions were removed, resulting in a final dataset of 436 valid responses. The study employed SEM to analyze the proposed conceptual framework. Based on Collier (2020), the recommended sample size for SEM requires 10–15 observations per indicator variable. With 26 indicator items included in this study, the final sample size exceeded the minimum threshold, ensuring reliable and meaningful results. Table 1 shows the respondents’ demographic profile.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of respondents.

3.3. Measures

Building on previous literature, authenticity was assessed across three dimensions: objective, constructive, and existential authenticity, comprising 14 items adapted from Teng and Chen (2020), Li et al. (2021), and Aguilar-Rivero et al. (2023). Overall perceived value was assessed using 5 items, adapted from C.-K. Lee et al. (2007) and S. Lee and Phau (2018). Tourist satisfaction was measured with 3 items modified from C.-K. Lee et al. (2007) and Jeong and Kim (2020). Revisit intentions and WOM intentions were each measured with 2 items based on Teng and Chen (2020). All measurement items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale (see Appendix A).

3.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics for respondents’ demographic profiles were generated using SPSS version 27.0. AMOS version 24.0 was then utilized to perform confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and evaluate the measurement model’s fit through multiple goodness-of-fit indices. Upon establishing the reliability and validity of the constructs, SEM was conducted in AMOS 24.0 to test the proposed hypotheses. Finally, to explore alternative causal configurations leading to high levels of revisit intention and WOM intention, fsQCA was carried out using fsQCA version 4.1.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

To assess the reliability and validity of the measurement constructs, CFA was performed using the maximum likelihood estimation method. The results indicated an acceptable model fit, with χ2/df = 1.950, CFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.906, SRMR = 0.052, and RMSEA = 0.072. The results indicate that the proposed measurement model aligns well with the observed data (Hair et al., 2019). Convergent validity was confirmed as all standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.644 to 0.944, exceeding the threshold of 0.50. The composite reliability (CR) values, which varied between 0.774 and 0.932, were above the recommended cut-off of 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency of the constructs. The average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.543 to 0.819, surpassing the recommended value of 0.50, indicating that the constructs captured a substantial amount of variance from their respective indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha (α) values ranged from 0.773 to 0.929, further supporting the reliability of the measurement scales (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Table 2 presents the standardized factor loadings of each item, CR, AVE, and α of each construct.

Table 2.

Results of the CFA.

The heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations was employed to evaluate discriminant validity, as it is recognized as a more robust criterion compared to traditional methods such as the Fornell–Larcker criterion. Following the guidelines established by Henseler et al. (2015), discriminant validity is established when the HTMT ratio is below 0.85. As presented in Table 3, all HTMT ratios in this research were below the recommended cut-off value, confirming that the constructs were clearly differentiated from one another.

Table 3.

Results of discriminant validity.

4.2. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The structural model proposed in this study included a second-order latent construct of perceived authenticity, composed of three first-order dimensions: objective, constructive, and existential authenticity. All first-order factors demonstrated significant relationships with the latent second-order factor, as indicated by their standardized loadings (objective authenticity: β = 0.748 ***; constructive authenticity: β = 0.941 ***; existential authenticity: β = 0.903 ***). Furthermore, these first-order factors explained 55.9%, 88.5%, and 81.6% of the total variance for perceived authenticity, respectively. These findings confirm the validity of the latent higher-order structure in this study.

The overall model demonstrated an acceptable level of fit, as indicated by χ2/df = 2.745, CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.950, SRMR = 0.042, and RMSEA = 0.063 (Hair et al., 2019). As illustrated in Table 4, perceived authenticity had a significant positive effect on perceived value (β = 0.839, p < 0.001), while perceived value positively influenced satisfaction (β = 0.577, p < 0.001). Additionally, perceived authenticity exhibited a direct positive effect on satisfaction (β = 0.322, p < 0.001), thereby supporting H1, H2, and H3. Furthermore, perceived authenticity exerted a significant influence on revisit intentions (β = 0.173, p = 0.012), supporting H4. However, perceived value (β = 0.026, p = 0.752) and satisfaction (β = 0.015, p = 0.817) did not exhibit a significant direct effect on revisit intentions. Consequently, H5 and H6 were not supported. In terms of WOM intentions, perceived authenticity (β = 0.202, p = 0.018), perceived value (β = 0.416, p < 0.001), and satisfaction (β = 0.219, p = 0.008) all had significant effects on WOM intentions, supporting H7, H8, and H9. Furthermore, WOM intentions significantly influenced revisit intentions (β = 0.815, p < 0.001), providing support for H10.

Table 4.

Results of hypothesis testing.

4.3. Necessary Condition Analysis

Before identifying sufficient configurations, an analysis of necessary conditions was conducted to examine whether any single condition consistently leads to high levels of revisit intention or WOM. Table 5 displays the results of this analysis. For revisit intention, none of the conditions met the recommended consistency threshold of 0.90 (Schneider & Wagemann, 2012), suggesting that no individual condition can be considered necessary for the outcome. A similar pattern was found for WOM, as none of the conditions reached the 0.90 threshold. Overall, these findings suggest that no individual factor alone is necessary to generate high revisit or WOM intentions.

Table 5.

Results of necessary condition analysis.

4.4. Sufficient Condition Analysis

To identify the sufficient conditions leading to high revisit and WOM intentions, a sufficient condition analysis was conducted. Table 6 presents the configurations associated with high revisit intentions. Four distinct combinations of causal conditions were identified, each representing an alternative pathway through which film tourists develop strong intentions to revisit film-related destinations. The overall solution consistency is 0.808, and the solution coverage is 0.736, indicating that these configurations collectively provide a reliable and substantial explanation of the outcome (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Configuration 1 highlights the joint presence of objective authenticity and constructive authenticity as core conditions, coupled with the absence of perceived value and satisfaction. This suggests that for some tourists, experiencing authentic film tourism experience, both objectively and constructively, is sufficient to stimulate revisit intentions, even when their perceived value or satisfaction is relatively low. Configuration 2 features constructive authenticity, existential authenticity, and perceived value as peripheral conditions, with satisfaction emerging as a core condition. Configuration 3 shows that the peripheral presence of perceived value, combined with satisfaction as a core condition and the absence of authenticity, can also lead to high revisit intentions. This implies that positive evaluations and perceived value may compensate for the lack of authenticity in motivating return visits. Configuration 4 combines the presence of objective and constructive authenticity as core conditions and existential authenticity as a peripheral condition with the absence of satisfaction. This pathway suggests that strong perceptions of authenticity can independently encourage revisit intentions, even when overall satisfaction is limited.

Table 6.

Configurations leading to high revisit intentions.

Table 7 presents the configurations that explain high levels of WOM among film tourists. Three distinct causal pathways were identified. The overall solution consistency is 0.832, and the solution coverage is 0.742, indicating that these configurations collectively provide a robust and comprehensive explanation of the outcome (Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Configuration 1 shows that the presence of objective, constructive, and existential authenticity as core conditions, together with the absence of satisfaction, can lead to strong WOM intentions. This finding suggests that even when tourists are not fully satisfied, deeply authentic film tourism experiences can still motivate them to share positive recommendations. Configuration 2 identifies constructive authenticity, existential authenticity, and satisfaction as core conditions, with perceived value as a peripheral condition. This pathway implies that when film tourists perceive authenticity across multiple dimensions and experience satisfaction, they are highly likely to engage in positive WOM behaviors. Configuration 3 indicates that the absence of authenticity dimensions does not necessarily prevent WOM, provided that perceived value and satisfaction are present. This finding suggests that even in less authentic settings, tourists who perceive high value and satisfaction may still recommend the destination to others.

Table 7.

Configurations leading to high WOM.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to examine the influence of perceived authenticity, overall perceived value, and satisfaction on film tourists’ revisit and WOM intentions, utilizing CAT as the theoretical framework. By integrating SEM and fsQCA, the empirical findings provide valuable insights into the psychological mechanisms underlying film tourists’ post-visit behaviors.

The SEM results confirm that perceived authenticity plays a fundamental role in enhancing perceived value and satisfaction among film tourists, thereby supporting H1 and H3. The significant positive effect of perceived authenticity on perceived value aligns with previous studies in cultural heritage tourism, which identify authenticity as a fundamental antecedent shaping tourists’ evaluations of the worth of their travel experiences (Atasoy & Eren, 2023; Kolar & Zabkar, 2010). This finding suggests that in the film tourism context, tourists perceive higher value when they regard film-related destinations as authentic, reinforcing the importance of authenticity in their overall evaluation. Likewise, perceived authenticity was found to significantly enhance satisfaction, supporting the notion that authenticity contributes to tourists’ emotional fulfillment and enjoyment of their visits (Zhou et al., 2023; J.-H. Kim et al., 2020). Furthermore, perceived value exerted a significant positive effect on satisfaction, supporting H2 and aligning with existing literature suggesting that higher perceived value often translates into more positive affective evaluations of the tourism experience (Phi et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2022).

Regarding the role of perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction in revisit intentions, the SEM findings indicate that perceived authenticity exerted a significant positive effect on revisit intentions, thereby supporting H4. This finding implies that when film tourists perceive a film-related destination as authentic, their likelihood of returning increases. This result is consistent with prior studies emphasizing the importance of perceived authenticity in fostering destination loyalty among film tourists (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023; Li et al., 2021; Teng & Chen, 2020). Unexpectedly, perceived value and satisfaction were found to have no significant effect on revisit intentions, resulting in the rejection of H5 and H6. This result contrasts with traditional tourism literature, which often identifies satisfaction and perceived value as key drivers of repeat visits (Baghirov et al., 2025; Phi et al., 2024). A possible explanation for this divergence is that film tourists differ fundamentally from general leisure tourists. Prior research suggests that many film tourists travel with a sense of symbolic pilgrimage, where the desire to connect with narratives, characters, and filmic settings surpasses functional evaluations of service quality or value (Aguilar-Rivero et al., 2023; Gómez-Morales et al., 2022; Hao et al., 2024). As a result, even when tourists perceive the trip as valuable and satisfying, these utilitarian assessments may play a limited role in shaping revisit decisions. Instead, revisit intentions appear more strongly grounded in whether the destination continues to evoke narrative immersion, emotional meaning, and a sense of being “true” to the film text (St-James et al., 2018). This aligns with evidence that film tourists prioritize emotional resonance and narrative authenticity over cognitive or utilitarian evaluations when forming behavioral intentions (Hao et al., 2024). Additionally, some film tourists exhibit novelty-seeking tendencies, using their visit to verify whether the real filming site aligns with its on-screen representation (Bolan et al., 2011). For these tourists, perceived authenticity becomes the dominant factor shaping revisit intention, as confirming and re-experiencing that authenticity holds more motivational weight than perceived value or satisfaction.

In contrast, perceived authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction were found to significantly influence WOM intentions, supporting H7, H8, and H9. These findings align with prior research emphasizing the role of perceived value and satisfaction in motivating tourists to share positive experiences (Andersen et al., 2025). In film tourism context, tourists who perceive a destination as highly authentic are more inclined to recommend it to others. This underscores the importance of destination marketers in enhancing perceived authenticity, value, and satisfaction to stimulate positive WOM, which can attract potential visitors and reinforce the destination’s appeal. Additionally, this study discovered that WOM intentions were a powerful indicator of revisit intentions, supporting H10. This supports existing literature suggesting that tourists who engage in positive WOM may develop a stronger emotional connection with the location, raising their likelihood of returning (Abubakar et al., 2017; Nazarian et al., 2024). Notably, although perceived value and satisfaction did not directly influence revisit intentions, the strong effect of WOM suggests that sharing positive experiences may prompt tourists to reflect on their film-related experiences and relive their emotional connections to the location, ultimately triggering their intention to revisit.

Beyond the symmetrical SEM findings, the fsQCA results provide complementary insights by uncovering how different combinations of multidimensional authenticity, perceived value, and satisfaction jointly lead to high revisit and WOM intentions. Four causal configurations were identified for high revisit intentions, confirming that multiple pathways can produce the same behavioral outcome (Han et al., 2025; J. J. Kim et al., 2023; Pappas & Woodside, 2021). Configurations 1 and 4 highlight the joint presence of objective and constructive authenticity as core conditions, even when perceived value and satisfaction are absent. This finding suggests that authenticity, whether grounded in tangible film settings or constructed through tourists’ interpretive engagement, can independently motivate revisit intentions, reinforcing its symbolic and experiential significance in film tourism (Hao et al., 2024; Li et al., 2021). Although the SEM findings indicated that perceived value and satisfaction did not significantly influence revisit intentions when examined individually, Configurations 2 and 3 reveal that when film tourists perceive high value and experience overall satisfaction with their trip, these factors can still lead to strong revisit intentions. This highlights that satisfaction and perceived value may act as alternative pathways that compensate for weaker perceptions of authenticity, demonstrating the multifaceted nature of post-visit behavioral formation among film tourists.

Similarly, three causal pathways were found for high WOM intentions. Configuration 1 suggests that the coexistence of objective, constructive, and existential authenticity can foster strong WOM, even in the absence of satisfaction, emphasizing the persuasive power of authentic film experiences. Configuration 2 combines constructive and existential authenticity with satisfaction, highlighting the emotional basis of recommendation behavior. Configuration 3 indicates that perceived value and high satisfaction can still generate WOM even when authenticity is weak, suggesting that tourists may promote destinations based on hedonic or service-related experiences (Baghirov et al., 2025; Jeong & Kim, 2020).

Overall, these fsQCA findings complement SEM results, revealing that while authenticity remains a dominant driver, satisfaction and value can reinforce or substitute it under certain conditions. The integrated SEM–fsQCA approach thus uncovers the configurational complexity of film tourists’ post-visit behaviors, advancing theoretical understanding of authenticity-driven experiences and behavioral heterogeneity in film tourism.

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

The present study advances theoretical understanding in film tourism by integrating CAT with a combined SEM–fsQCA approach to examine the complex mechanisms driving film tourists’ post-visit behaviors. The findings reinforce the pivotal role of perceived authenticity in shaping tourists’ cognitive and emotional appraisals, thereby influencing their revisit and WOM intentions. The results extend existing research by demonstrating that authenticity not only enhances perceived value and satisfaction but also directly stimulates revisit intentions—highlighting its centrality in film tourism experiences. Notably, while perceived value and satisfaction did not significantly predict revisit intentions in the symmetrical SEM model, the configurational analysis revealed that these factors, when combined with high authenticity perceptions or with each other, can still lead to strong revisit intentions. This underscores the value of adopting an asymmetric perspective to capture the multifaceted and interdependent nature of tourists’ behavioral motivations. Furthermore, the strong relationship between WOM and revisit intentions illustrates WOM as a key reinforcing mechanism that sustains tourists’ psychological engagement with film destinations over time.

From a managerial standpoint, this study provides practical guidance for destination marketers and tourism planners seeking to enhance the appeal and sustainability of film-related destinations. Given the dominant influence of authenticity, destination managers should focus on preserving the original essence of filming sites, maintaining accurate representations of cinematic settings, and embedding storytelling elements that strengthen visitors’ emotional and symbolic connection to the film narrative. In addition, destination marketers should leverage WOM as a strategic communication channel by encouraging visitor-generated content, fostering online engagement, and designing campaigns that inspire film tourists to share their experiences. Such efforts not only amplify the destination’s visibility but also cultivate a self-sustaining cycle of engagement and loyalty among film tourists.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Although this research provides important implications, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study focused solely on Chinese film tourists visiting Thailand, which may limit the findings’ applicability in other cultural and geographic contexts. Future research could apply the proposed framework to different destinations or tourist groups to examine whether the observed relationships hold across diverse settings. Second, while the quantitative approach effectively identified both linear and configurational relationships, it may not fully capture the deeper motivations and emotional meanings underlying film tourists’ experiences. Future studies could employ qualitative or mixed-method designs to explore these psychological and experiential dimensions in greater depth. Finally, this study highlighted the importance of WOM in shaping revisit intentions but did not distinguish between communication channels such as social media, online reviews, or personal recommendations. Future studies could examine how these different forms of WOM influence destination loyalty and long-term engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S. and P.P.-a.; methodology, D.S.; software, D.S.; validation, D.S. and P.P.-a.; formal analysis, D.S.; investigation, D.S.; data curation, D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S. and P.P.-a.; visualization, D.S.; supervision, P.P.-a.; project administration, P.P.-a.; funding acquisition, D.S. and P.P.-a. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism—Full Grants for FHT—Ph.D. Research, Prince of Songkla University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Prince of Songkla University, Phuket campus (protocol code: psu.pk 026/2024; date of approval: 18 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Items

Table A1.

Measurement items.

Table A1.

Measurement items.

| Code | Constructs/Items |

|---|---|

| OA | Objective authenticity |

| OA1 | Unique architecture in Thailand. |

| OA2 | Natural landscape/scenery in Thailand. |

| OA3 | I can associate the plots/scenes/characters from the film/TV series with Thailand. |

| CA | Constructive authenticity |

| CA1 | The overall architecture and impression of the Thai film-related destination inspired me. |

| CA2 | The film-related destination reflected the culture of Thailand in an authentic way. |

| CA3 | I liked the way the Thai film-related destination blends with the attractive landscape/scenery/historical sites, which offer many other interesting places for sightseeing. |

| CA4 | I liked the information about Thai film-related destinations and found them interesting. |

| CA5 | I can tell the characteristics of the people living in Thailand during my visit to the film-related destination. |

| CA6 | I can tell the cultural/historical character of Thailand during my visit to the film-related destination. |

| EA | Existential authenticity |

| EA1 | I liked the special arrangements and events connected to the film-related destination in Thailand. |

| EA2 | I enjoyed the unique Thai cultural experience at the film-related destination in Thailand. |

| EA3 | I was informed about the Thai culture after visiting the film-related destination in Thailand. |

| EA4 | During the visit, I enjoyed the re-enacting experiences. |

| EA5 | I tried to seek unusual experiences to pursue self-fulfillment or self-satisfaction during my visit to the film-related destination in Thailand. |

| PV | Overall perceived value |

| PV1 | Visiting the film-related destination gave me pleasure. |

| PV2 | Overall, visiting the film-related destination was valuable and worth it. |

| PV3 | The value of visiting the film-related destination was more than what I expected. |

| PV4 | After visiting the film-related destination, my image of Thailand was improved. |

| PV5 | The choice of visiting the film-related destination was a good decision. |

| SA | Satisfaction |

| SA1 | Overall satisfaction with the film-related destination. |

| SA2 | Satisfaction with the film-related destination when compared with my expectations. |

| SA3 | Satisfaction with the film-related destination when considering the time and effort I invested. |

| RI | Revisit intentions |

| RI1 | I would like to come back to this film-related destination in the near future. |

| RI2 | I am interested in visiting other film-related destinations in Thailand in the near future. |

| WOM | Word-of-mouth intentions |

| WOM1 | I would recommend this film-related destination to others. |

| WOM2 | I would like to recommend other film-related destinations in Thailand to others. |

References

- Abubakar, A. M., Ilkan, M., Meshall Al-Tal, R., & Eluwole, K. K. (2017). eWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D., Pinto, P., & Mendes, J. (2017). Tourists’ memories, sensory impressions and loyalty: In loco and post-visit study in Southwest Portugal. Tourism Management, 58, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Rivero, M., Moral-Cuadra, S., López-Guzmán, T., & Solano-Sánchez, M. Á. (2023). Authenticity and motivations towards film destination. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(5), 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C., Nyhus, E. K., & Engeset, M. G. (2025). How pre-vacation factors influence post-vacation word-of-mouth. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, F., & Eren, D. (2023). Serial mediation: Destination image and perceived value in the relationship between perceived authenticity and behavioural intentions. European Journal of Tourism Research, 33, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, D., & Song, L. (2022). The impact of after-travel sharing on social media on tourism experience from the perspective of sharer: Analysis on grounded theory based on interview data. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, 2022(1), 7202078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghirov, F., Bozbay, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Individual factors impacting tourist satisfaction and revisit intention in slow tourism cities: An extended model. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 11, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaskas, S., Nikolopoulos, T., Bolano, A., Skouri, D., & Kayios, T. (2025). Neurotourism aspects in heritage destinations: Modeling the impact of sensory appeal on affective experience, memory, and recommendation intention. Sustainability, 17(18), 8475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, P., Boy, S., & Bell, J. (2011). “We’ve seen it in the movies, let’s see if it’s true”: Authenticity and displacement in film-induced tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 3(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryce, D., Curran, R., O’Gorman, K., & Taheri, B. (2015). Visitors’ engagement and authenticity: Japanese heritage consumption. Tourism Management, 46, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, A., Moore, K., & Fisher, D. (2010). Experiencing film tourism: Authenticity & fellowship. Annals of Tourism Research, 37(1), 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F., & Chen, F.-S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., & Chen, H. (2020). Differences in preventive behaviors of COVID-19 between urban and rural residents: Lessons learned from a cross-sectional study in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cifci, I., Cüneyt, K. O., Sunil, T., & Rasoolimanesh, S. M. (2023). Demystifying meal-sharing experiences through a combination of PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32(7), 843–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Quintero, A. M., González-Rodríguez, M. R., & Paddison, B. (2020). The mediating role of experience quality on authenticity and satisfaction in the context of cultural-heritage tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(2), 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. R., & Mathur, A. (2005). The value of online surveys. Internet Research, 15(2), 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhi, F., & Mahmoudi-Hamidabad, A. (2012). Rethinking convenience sampling: Defining quality criteria. Theory & Practice in Language Studies (TPLS), 2(4), 784–792. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Liu, X., Wang, Y., & Chao, R.-F. (2018). How experiential consumption moderates the effects of souvenir authenticity on behavioral intention through perceived value. Tourism Management, 69, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Morales, B., Nieto-Ferrando, J., & Sánchez-Castillo, S. (2022). (Re)Visiting game of thrones: Film-induced tourism and television fiction. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 39(1), 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Pearson Prentice. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., Kim, S., Baah, N. G., Quan, L., Al-Ansi, A., & Chi, X. (2025). Antecedents of customer retention in the green hotel context: Exploring the optimum combination of cognitive and affective factors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 8(5), 1761–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X., Jiang, E., & Chen, Y. (2024). The sign Avatar and tourists’ practice at Pandora: A semiological perspective on a film related destination. Tourism Management, 101, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S., Prayag, G., Van Der Veen, R., Huang, S., & Deesilatham, S. (2017). Mediating effects of place attachment and satisfaction on the relationship between tourists’ emotions and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 56(8), 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irimiás, A., Mitev, A. Z., & Michalkó, G. (2021). Narrative transportation and travel: The mediating role of escapism and immersion. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y., & Kim, S. (2020). A study of event quality, destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty among sport tourists. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 32(4), 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. (2020). A cognitive appraisal process of customer delight: The moderating effect of place identity. Journal of Travel Research, 59(6), 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Thanabordeekij, P., & Chankoson, T. (2018). Factors influencing Chinese consumers’ purchase intention for Thai products and travel in Thailand from Thai dramas and films. PSAKU International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 7(1), 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirattikorn, A. (2021). Between ironic pleasure and exotic nostalgia: Audience reception of Thai television dramas among youth in China. Asian Journal of Communication, 31(2), 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, J., Sihombing, S. O., & Antonio, F. (2025). Unveiling memorable tourism experiences effect on positive EWOM: Focus on the role of positive and negative emotion. Cogent Social Sciences, 11(1), 2557073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H., Song, H., & Youn, H. (2020). The chain of effects from authenticity cues to purchase intention: The role of emotions and restaurant image. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 85, 102354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J., Kim, S., Hailu, T. B., Ha, H., & Han, H. (2023). Impacts of UAM on tourism: The roles of innovative characteristics, motivated consumer innovativeness, attitude, problem awareness, and cultural differences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(12), 1452–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, T., & Zabkar, V. (2010). A consumer-based model of authenticity: An oxymoron or the foundation of cultural heritage marketing? Tourism Management, 31(5), 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-K., Yoon, Y.-S., & Lee, S.-K. (2007). Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: The case of the Korean DMZ. Tourism Management, 28(1), 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Phau, I. (2018). Young tourists’ perceptions of authenticity, perceived value and satisfaction: The case of Little India, Singapore. Young Consumers, 19(1), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Tian, W., Lundberg, C., Gkritzali, A., & Sundström, M. (2021). Two tales of one city: Fantasy proneness, authenticity, and loyalty of on-screen tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 60(8), 1802–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H., & Wang, W.-C. (2012). Effects of authenticity perception, hedonics, and perceived value on ceramic souvenir-repurchasing intention. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 29(8), 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L., Chi, C. G., & Liu, Y. (2015). Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tourism Management, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B., Li, L., & Sun, Y. (2022). Understanding the influence of consumers’ perceived value on energy-saving products purchase intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 640376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacCannell, D. (1973). Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. American Journal of Sociology, 79(3), 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, A., Silk, M., Chung, C., Wang, Y.-W., & Bailey, R. (2023). Chinese perceptions of overseas cultural heritage: Emotive existential authenticity, exoticism and experiential tourism. Leisure Sciences, 45(3), 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, D., Sava, C., Petroman, C., Văduva, L., & Petroman, I. (2021). Cinematographic tourism subtype of cultural tourism. Quaestus, (18), 377–387. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/cinematographic-tourism-subtype-cultural/docview/2547076837/se-2?accountid=167725 (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Mkono, M. (2012). A netnographic examination of constructive authenticity in Victoria Falls tourist (restaurant) experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, A., Shabankareh, M., Ranjbaran, A., Sadeghilar, N., & Atkinson, P. (2024). Determinants of intention to revisit in hospitality industry: A cross-cultural study based on globe project. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 36(1), 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H. H. (2020). A reflective–formative hierarchical component model of perceived authenticity. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(8), 1211–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. H. H., & Cheung, C. (2016). Chinese heritage tourists to heritage sites: What are the effects of heritage motivation and perceived authenticity on satisfaction? Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(11), 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I. O., & Woodside, A. G. (2021). Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA): Guidelines for research practice in Information Systems and marketing. International Journal of Information Management, 58, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E., Choi, B.-K., & Lee, T. J. (2019). The role and dimensions of authenticity in heritage tourism. Tourism Management, 74, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phi, L. N., Phuong, D. H., & Huy, T. V. (2024). How perceived crowding changes the interrelationships between perceived value, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: The empirical study at Hoi An. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10(1), 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C., Timothy, D. J., Wang, Z., & Su, Y. (2024). Bottom-up heritage conservation, tourists’ demand and homestays as purveyors of cultural authenticity. Tourism Recreation Research, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P., Seebaluck, V. N., & Naidoo, P. (2015). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, perceived value, tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Case of Mauritius. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 175, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Seyfi, S., Rather, R. A., & Hall, C. M. (2022). Investigating the mediating role of visitor satisfaction in the relationship between memorable tourism experiences and behavioral intentions in heritage tourism context. Tourism Review, 77(2), 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R. T., & Oliver, R. L. (1994). Service quality: Insights and managerial implications from the frontier. In Service quality: New directions in theory and practice. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C. Q., & Wagemann, C. (2012). Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: A guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D., Soonsan, N., & Phakdee-Auksorn, P. (2024). The effect of audience involvement on previsit behavioral intentions: The mediating role of place attachment. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 11(2), 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. (2020, October 23–25). An analysis of the popularity of thai television drama in China, 2014–2019. Proocedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2020), Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, H. K., Lee, T. J., & Yoon, Y. S. (2016). Relationship between perceived risk, evaluation, satisfaction, and behavioral intention: A case of local-festival visitors. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(1), 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Yang, H., & Sthapit, E. (2025). Robotic service quality, authenticity, and revisit intention to restaurants in China: Extending cognitive appraisal theory. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 37, 1497–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-James, Y., Darveau, J., & Fortin, J. (2018). Immersion in film tourist experiences. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(3), 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S., DiPietro, R. B., & So, K. K. F. (2018). Increasing experiential value and relationship quality: An investigation of pop-up dining experiences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 74, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, H.-Y., & Chen, C.-Y. (2020). Enhancing celebrity fan-destination relationship in film-induced tourism: The effect of authenticity. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, N. A., Brea, J. A. F., & Carlos, P. d. (2021). Film tourism in Spain: Destination awareness and visit motivation as determinants to visit places seen in TV series. European Research on Management and Business Economics, 27(1), 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. (1999). Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(2), 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareebor, S., Suttikun, C., & Mahasuweerachai, P. (2025). Perceived authenticity and tourist behavior toward local restaurants: An empirical study in Thailand. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H., Josiam, B. M., Spears, D. L., & Yang, Y. (2018). Influence of movies and television on Chinese tourists perception toward international tourism destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 28, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., & Lai, I. K. W. (2023). How to promote film tourism more effectively? From a perspective of self-congruity and film tourism experience. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 28(6), 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Pratt, S., & Yan, L. (2023). Residents’ engagement in developing destination mascots: A cognitive appraisal theory-based perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 40(2), 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R., & Yang, J. (2024). Exploring the appeal of villainous characters in film-induced tourism: Perceived charismatic leadership and justice sensitivity. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, N., Öncüer, M. E., & Tanrisevdi, A. (2024). Examining multiple mediation of authenticity in the relationship between cultural motivation pattern and satisfaction: A case study of Şirince in Turkey. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 7, 676–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., & Lo, Y.-H. (2024). Tourists’ perceived destination image and heritage conservation intention: A comparative study of heritage and film-induced images. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 10, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., & Yin, P. (2020). Testing the structural relationships of tourism authenticities. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Guo, W., Sheng, Y., & Li, S. (2025). Word-of-mouth evaluation of ancient towns in Southern China using web comments. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-F., & Li, Z.-W. (2023). Destination authenticity, place attachment and loyalty: Evaluating tourist experiences at traditional villages. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(23), 3887–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Wang, X., & Mao, Y. (2025). Secrets of more likes: Understanding eWOM popularity in wine tourism reviews through text complexity and personal disclosure. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(3), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., He, Z., & Li, X. (2023). Quantifying authenticity: Progress and challenges. Journal of Travel Research, 62(7), 1460–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).