Structural Model of Key Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Organic Dining Restaurants Within Green Hotels

Abstract

1. Introduction

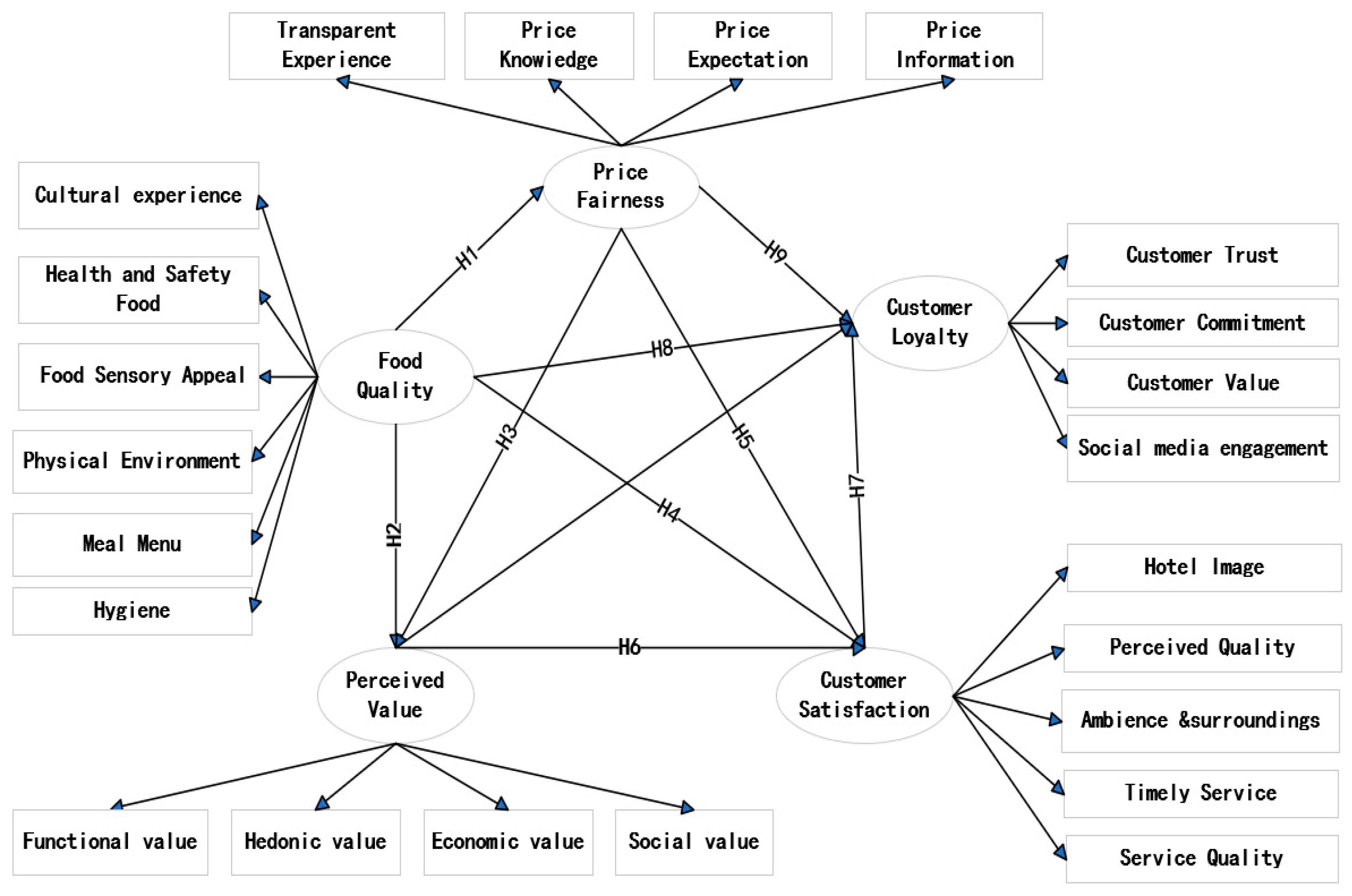

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Foundational Stimuli: Perceived Food Quality and Price Fairness

2.2. The Organism: The Cognitive-Affective Core of the Experience

2.3. The Response: The Ultimate Objective of Customer Loyalty

2.4. The Dynamic Process: Sequential Mediation in Loyalty Formation

3. Research Design and Method

3.1. Phase 1: Qualitative Instrument Refinement and Contextualization

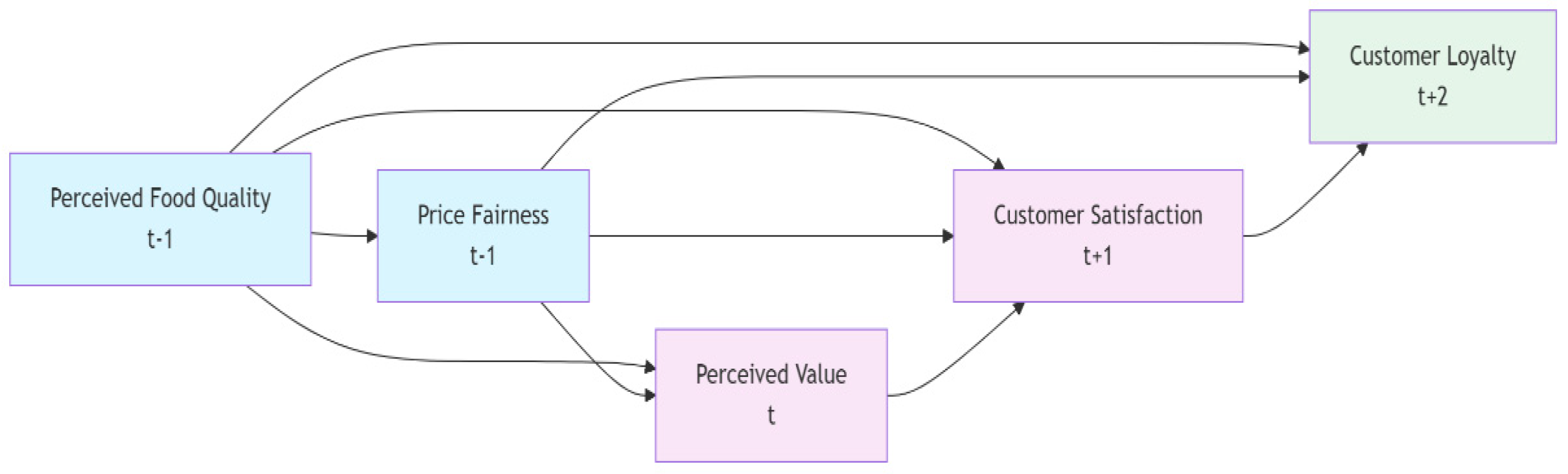

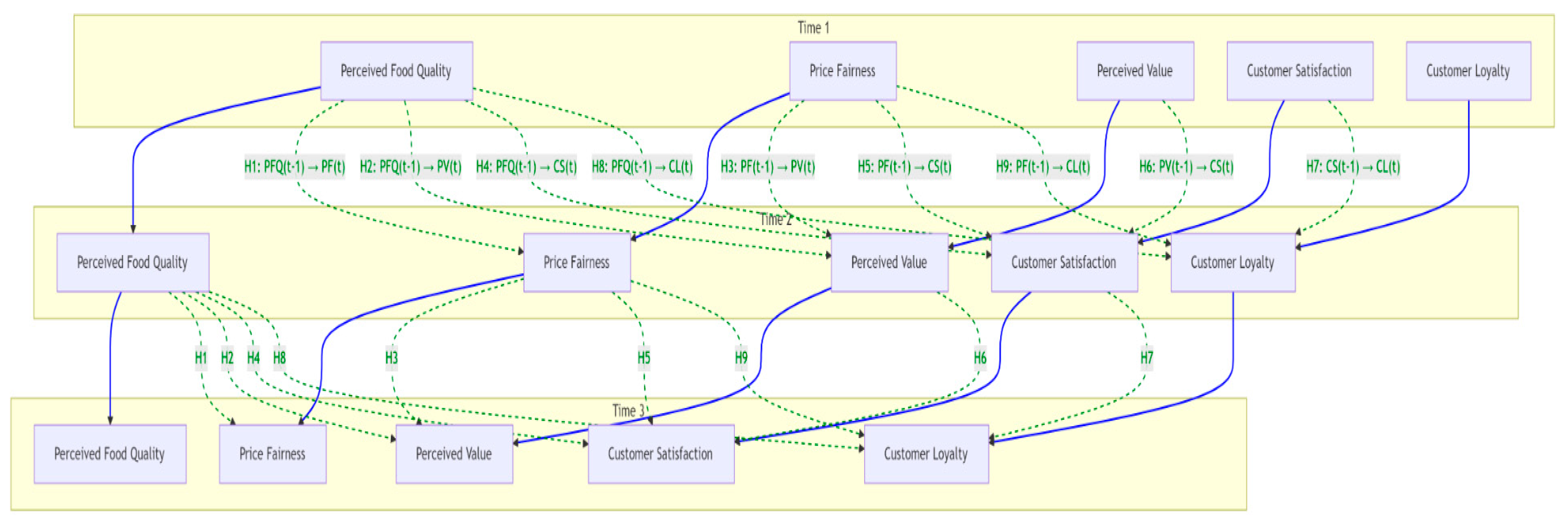

3.2. Phase 2: Longitudinal Panel Survey and Procedure

3.3. Measures

3.4. Data Analysis Strategy

3.5. Control for Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analysis: Exploratory Factor Analysis

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Implications for Research and Practice

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Managerial Implications

7.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct and Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|

| Food Quality (FQ) | |

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) = 0.935; Bartlett’s Test: χ2 = 13,452.17, p < 0.001; Cumulative Variance Explained = 72.8% | |

| Factor 1: Cultural Experience (ce) | |

| 1. Experiencing this organic food restaurant offers unique Chinese traditions. | 0.871 |

| 2. Dining at this organic food restaurant provides an opportunity to increase my knowledge of Chinese culture. | 0.853 |

| 3. Dining at this organic food restaurant helps me understand the local lifestyle. | 0.829 |

| 4. Dining at this organic food restaurant allows me to experience things I do not usually see. | 0.840 |

| Factor 2: Health and Safety Food (hsf) | |

| 5. This organic food restaurant provides fresh food, ingredients, and recipes. | 0.838 |

| 6. This organic food restaurant provides nutrient-rich food, ingredients, and recipes. | 0.841 |

| 7. This organic food restaurant provides clean food, ingredients, and recipes. | 0.839 |

| 8. The food at this organic food restaurant is good for my health. | 0.836 |

| Factor 3: Food Sensory Appeal (fsa) | |

| 9. This organic food restaurant has appealing flavours. | 0.830 |

| 10. The food at this organic food restaurant smells good. | 0.845 |

| 11. The food at this organic food restaurant is tasty. | 0.842 |

| 12. The food at this organic food restaurant has a pleasant texture. | 0.833 |

| Factor 4: Physical Environment (PE) | |

| 13. The restaurant’s dining area is neat and clean. | 0.824 |

| 14. The restaurant is easily accessible. | 0.831 |

| 15. The restaurant provides clear information about its service times. | 0.812 |

| 16. The restaurant has a pleasant and comfortable atmosphere. | 0.818 |

| Factor 5: Meal Menu (me) | |

| 7. This organic food restaurant offers a variety of menu items. | 0.826 |

| 18. This organic food restaurant provides a menu with healthy choices. | 0.830 |

| 19. This organic food restaurant offers an ethnic and local cuisine experience. | 0.815 |

| 20. This organic food restaurant offers a takeaway service. | 0.832 |

| Factor 6: Hygiene (he) | |

| 21. This restaurant’s food products are hygienic. | 0.825 |

| 22. This restaurant’s food products are cooked under clean conditions. | 0.829 |

| 23. The sanitation related to this restaurant’s food products is well-managed. | 0.823 |

| 24. This restaurant’s food and beverages are clean and safe to consume. | 0.814 |

| Price Fairness (PF) | |

| KMO = 0.912; Bartlett’s Test: χ2 = 9877.41, p < 0.001; Cumulative Variance Explained = 70.3% | |

| Factor 1: Treatment Experience (te) | |

| 25. This hotel’s organic food restaurant treats me fairly. | 0.883 |

| 26. I am satisfied with the overall experience at this hotel’s organic food restaurant. | 0.828 |

| 27. The price I paid for the organic food was justified. | 0.812 |

| 28. The dining experience at this hotel’s organic food restaurant is worth the money I paid. | 0.830 |

| Factor 2: Price Knowledge (pk) | |

| 29. There is a price discrepancy between what I paid today and what I have paid on previous visits. | 0.821 |

| 30. The offered rate for the organic food is questionable. | 0.813 |

| 31. Considering all aspects, the price for the organic food is justified. | 0.825 |

| 32. I feel well-informed about this restaurant’s pricing policies and any changes to its rates. | 0.808 |

| Factor 3: Price Expectation (pen) | |

| 33. This is the price I would expect to pay for an organic meal… | 0.862 |

| 34. The condition of this restaurant justifies the price I paid. | 0.785 |

| 35. This price aligns with my expectations for the services provided… | 0.838 |

| 36. I believe the price I paid is reasonable for the amenities and services… | 0.804 |

| Factor 4: Price Information (pi) | |

| 37. Information about the organic food rate influences my decision to choose this restaurant. | 0.810 |

| 38. My knowledge of this restaurant’s organic food rating comes from advertisements. | 0.801 |

| 39. I compare prices among different restaurants… before making a decision. | 0.828 |

| 40. The organic food rate is a rip-off. | 0.776 |

| Perceived Value (PV) | |

| KMO = 0.941; Bartlett’s Test: χ2 = 11,024.65, p < 0.001; Cumulative Variance Explained = 74.1% | |

| Factor 1: Functional Value (fv) | |

| 41. The service at this restaurant is very reliable. | 0.852 |

| 42. The service at this restaurant performs well. | 0.841 |

| 43. The service at this restaurant meets an acceptable standard of quality. | 0.849 |

| 44. The service at this restaurant is consistently performed. | 0.857 |

| Factor 2: Hedonic Value (hv) | |

| 45. The service at this restaurant is enjoyable. | 0.884 |

| 46. The service at this restaurant encourages me to return. | 0.843 |

| 47. The service at this restaurant makes me feel relaxed. | 0.822 |

| 48. The service at this restaurant makes me feel good. | 0.868 |

| Factor 3: Economic Value (EV) | |

| 49. The service at this restaurant is fairly priced. | 0.842 |

| 50. Compared to other equivalent services, this restaurant is economical. | 0.863 |

| 51. The service at this restaurant offers good value for money. | 0.820 |

| 52. I believe the pricing… reflects the quality and benefits received. | 0.829 |

| Factor 4: Social Value (sv) | |

| 53. The service at this restaurant would earn me social recognition. (ethical). | 0.850 |

| 54. The service at this restaurant helps me leave a positive impression on others. (ethical). | 0.852 |

| 55. The service at this restaurant makes me feel accepted by society. (ethical). | 0.846 |

| 56. The service at this restaurant connects me to a modern and progressive community. (ethical). | 0.861 |

| Customer Satisfaction (CS) | |

| KMO = 0.955; Bartlett’s Test: χ2 = 12,983.22, p < 0.001; Cumulative Variance Explained = 73.9% | |

| Factor 1: Service Quality (sq) | |

| 57. The service staff is courteous and professional. | 0.880 |

| 58. I feel valued by the attention provided by the service staff. | 0.861 |

| 59. The quality of service is consistent with each visit. | 0.837 |

| 60. The quality of service encourages me to return to this restaurant. | 0.844 |

| Factor 2: Timely Service (ts) | |

| 61. The service staff delivers food promptly. | 0.881 |

| 62. I am satisfied with the wait time before being served. | 0.825 |

| 63. This restaurant provides timely service during peak hours. | 0.860 |

| 64. The staff responds quickly to additional requests. | 0.853 |

| Factor 3: Ambience & Surroundings (as) | |

| 65. The atmosphere… enhances my overall dining experience. | 0.828 |

| 66. I am satisfied with the cleanliness of the restaurant’s environment. | 0.816 |

| 67. The decor and lighting… create a comfortable atmosphere. | 0.830 |

| 68. The background music and temperature contribute positively… | 0.835 |

| Factor 4: Perceived Quality (pq) | |

| 69. Overall evaluation of the quality of the experience. | 0.826 |

| 70. Evaluation of the customisation experience… | |

| 71. Evaluation of the reliability of the experience. | 0.814 |

| 72. Evaluation of the service’s responsiveness… | 0.831 |

| Factor 5: Hotel Image (hi) | |

| 73. This restaurant can be trusted in its claims and actions. | 0.828 |

| 74. This restaurant is stable and well-established. | 0.834 |

| 75. This restaurant contributes positively to society. | 0.879 |

| 76. This restaurant is attentive to its customers. | 0.858 |

| Customer Loyalty (CL) | |

| KMO = 0.923; Bartlett’s Test: χ2 = 10,115.89, p < 0.001; Cumulative Variance Explained = 71.5% | |

| Factor 1: Customer Trust (ct) | |

| 77. Many people I know use the services of this restaurant. | 0.872 |

| 78. My behaviour is influenced by those who also use this restaurant. | 0.821 |

| 79. People whose opinions I value also use this restaurant. | 0.876 |

| 80. I trust the service of this restaurant because it is recommended by people I respect. | 0.833 |

| Factor 2: Customer Commitment (cc) | |

| 81. I will continue to pay for the services offered by this restaurant. | 0.815 |

| 82. In the future, I will be fully committed to its services. | 0.851 |

| 83. I will not pay for this restaurant’s services in the future. (Reversed) | 0.828 |

| 84. I feel a sense of loyalty towards this restaurant and its services. | 0.840 |

| Factor 3: Customer Value (CV) | |

| 85. I would choose this restaurant’s services because they are worth the cost. | 0.881 |

| 86. The services offered by this restaurant are worthwhile. | 0.832 |

| 87. The services at this restaurant provide good value for money. | 0.845 |

| 88. The benefits of this restaurant’s services outweigh the costs I incur. | 0.842 |

| Factor 4: Social Media Engagement (SE) | |

| 89. Engaging in conversations on the WeChat Moments of this restaurant. | 0.848 |

| 90. Sharing posts from this restaurant on my own WeChat Moments. | 0.837 |

| 91. Recommending this restaurant’s WeChat Moments to my contacts. | 0.841 |

| 92. Uploading product-related videos, audio, pictures, or images. | 0.817 |

| Note. Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring. Rotation Method: Promax with Kaiser Normalisation. | |

References

- Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 267–299). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R. R., Al Asheq, A., & Pabel, A. (2023). A systematic review of service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty in the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 56, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P. (1992). The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions, and behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(2), 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J., & de Ruyter, K. (1998). On the relationship between store image, store satisfaction, and store loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 32(5/6), 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R. N., Kannan, P. K., & Bramlett, M. D. (2000). Implications of loyalty program membership and service experiences for customer retention and value. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J. T., & Chen, S. L. (2001). The relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 13(5), 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Park, S., & Kim, J. (2024). From likes to loyalty: The role of brand community engagement in translating satisfaction into advocacy in the restaurant industry. Journal of Service Research, 27(1), 112–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. S., & Chang, C. H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(3), 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C. G., & Qu, H. (2008). Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction, and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tourism Management, 29(4), 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Hospitality Association. (2023). Annual report on the state of China’s hotel industry. CHA. [Google Scholar]

- China Tourism Academy. (2023). Annual report on China’s tourism economy. CTA. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J. J., Jr., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel, S. E. (1995). Causal analysis with panel data. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20(1), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Impact of hotel-restaurant image and quality of physical environment, food, and service on consumer loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 63, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. (2002). Stimulus–organism–response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(1), 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S. S., & Namkung, Y. (2009). Perceived quality, emotions, and behavioral intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. Journal of Business Research, 62(4), 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. D., Gustafsson, A., Andreassen, T. W., Lervik, L., & Cha, J. (2001). The evolution and future of national customer satisfaction index models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(2), 217–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1986). Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. The American Economic Review, 76(4), 728–741. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, M. W. (2017). Cross-lagged panel analysis. In M. Allen (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods. SAGE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F. A. (2019). The influence of perceived food quality, price fairness, perceived value, and satisfaction on customers’ revisit and word-of-mouth intentions towards organic food restaurants. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 50, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., & Rahman, Z. (2022). Unpacking green value: A meta-analytic review and research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production, 345, 1311. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., & Johnson, C. (2024). Value as the cornerstone of satisfaction: A meta-analysis of 30 years of service research. Journal of Service Research, 27(2), 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S., Kim, H., & Lee, Y. (2023). The role of authenticity and perceived transparency in building trust in green hotel brands. Tourism Management, 95, 104678. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J., & Wang, Y. (2024). Digitalization and sustainability in hospitality: An integrated framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 118, 103681. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Consuegra, D., Molina, A., & Esteban, Á. (2007). An integrated model of price, satisfaction, and loyalty. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 16(7), 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. (2002). Longitudinal research (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namkung, Y., & Jang, S. (2007). Does food quality really matter in restaurants? Its impact on customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 31(3), 387–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., & Jones, P. (2025). The temporal decay of satisfaction’s influence on loyalty: A longitudinal study in the airline industry. Journal of Marketing, 89(1), 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H. (2000). The effect of brand class, brand awareness, and price on customer value and behavioral intentions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24(2), 136–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(Suppl. S1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J. C., & Jacoby, J. (1972). Cue utilization in the quality perception process. In M. Venkatesan (Ed.), ACR special volumes (vol. 3, pp. 167–179). Purdue University ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y. (2025). Feeling your way to a decision: Building customer loyalty by managing your customer’s emotions. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y., & Chen, L. (2025). Building brand equity in competitive hospitality markets: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 105, 103712. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, G., Singh, P. K., & Yadav, R. (2023). Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to explicate the impact of green practices on green brand equity and loyalty. Journal of Cleaner Production, 407, 1370. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R. A., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2024). Advancing customer engagement research: A call for dynamic and process-oriented approaches. Journal of Service Research, 27(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reichheld, F. F. (2003). The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K., Lee, H. R., & Kim, W. G. (2012). The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(2), 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Becker, J. M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 27(3), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2024). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, M., & Bauer, C. (2023). Relational consequences of price unfairness in service relationships: A longitudinal study. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 33(4), 510–531. [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, J. N., Newman, B. I., & Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A., & Jones, B. (2023). The ethical consumer 2.0: Value perceptions in sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 50(1), 123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M., Vinzi, V. E., Chatelin, Y. M., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modeling. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2009). Identifying factors affecting panel attrition: Evidence from the HILDA survey. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 172(2), 427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L., Monroe, K. B., & Cox, J. L. (2004). The price is unfair! A conceptual framework of price fairness perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C., & Park, J. (2022). The dynamics of attitude formation and change: A longitudinal investigation. Psychological Science, 33(5), 724–736. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct & Sub-Dimension | Original Item Example (from Literature) | Key Qualitative Insight from Expert Interviews & Focus Groups | Adapted Item Used in Survey (Example) | Rationale for Adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Quality (FQ) | ||||

| Cultural Experience (CE) | “The food is authentic.” (General authenticity item) | “Authenticity isn’t just about ingredients. For our guests, it’s about connecting with the local culture—the story of the dish, the traditional cooking methods. It’s a cultural performance.” | The restaurant’s menu skillfully incorporates local culinary traditions, telling a story about the origin of the food. | To move beyond a simple concept of authenticity to the richer, specific dimension of “Cultural Experience,” which was identified as a key driver of perceived quality in this high-end context. |

| Health & Safety Food (HSF) | “This restaurant provides healthy choices.” (Konuk, 2019) | “Guests demand tangible proof of safety—certifications, visible hygiene, and trust in the kitchen’s process. ‘Healthy’ is not enough; ‘safe’ is the foundation.” | I have complete confidence in the health and safety standards of the food prepared at this restaurant. | To capture the critical dimension of “Health and Safety,” which experts noted is a non-negotiable baseline expectation that supersedes general “healthiness” in the luxury dining landscape. |

| Food Sensory Appeal (FSA) | “The food tastes good.” (Namkung & Jang, 2007) | “The sensory experience is everything. It’s the visual ‘wow’ when the plate arrives, the complex aroma, the perfect texture. It must be an artistic and multi-sensory journey.” | The presentation of the food is visually artistic and appealing. | To operationalize a multi-faceted “Sensory Appeal” that includes visual aesthetics, aroma, and texture, moving beyond a one-dimensional “taste” item to reflect the high-end dining experience. |

| Physical Environment (PE) | “The restaurant’s atmosphere is pleasant.” (Ryu et al., 2012) | “The environment must be an extension of the brand. It must feel exclusive, luxurious, and thoughtfully designed. ‘Pleasant’ is too generic; ‘immersive’ is the goal.” | The restaurant’s interior design and decor create a sense of luxury and exclusivity. | To specify the “Physical Environment” beyond simple pleasantness, focusing on the concepts of luxury and exclusivity that are central to the value proposition of a fine-dining hotel restaurant. |

| Meal Menu (MM) | “This restaurant offers a lot of choices.” (Ryu et al., 2012) | “It’s not about the number of choices, but the quality of the choices. The menu must be creative, well-curated, and feature unique dishes you can’t find elsewhere.” | The menu offers a good selection of creative and interesting dishes. | To shift the focus from menu quantity to menu quality and creativity, which experts identified as a more accurate indicator of food quality in a fine-dining setting. |

| Hygiene (HY) | “This restaurant is clean.” (General hygiene item) | “In luxury dining, hygiene must be impeccable and visible. It’s the clean cutlery, the spotless glassware, the pristine restrooms. It is an absolute, not a relative, standard.” | The restaurant’s premises, including tableware and staff appearance, are impeccably clean and well-maintained. | To elevate the standard from simply “clean” to “impeccably clean and well-maintained,” reflecting the zero-tolerance expectation for hygiene in a premium environment. |

| Price Fairness (PF) | ||||

| Treatment Experience (TE) | “I was treated fairly.” (General fairness item) | “Fairness isn’t just about the bill. It’s about being treated with respect regardless of what you order. VIP treatment should feel genuine. This sense of being valued is fairness.” | The restaurant staff treats all customers with equal respect and professionalism, making me feel valued. | To specify the concept of ‘fairness’ to the interpersonal “Treatment Experience,” which experts highlighted as crucial. It reframes fairness from a purely economic concept to a relational one. |

| Price Knowledge (PK) | “I am well-informed about pricing.” (Martín-Consuegra et al., 2007) | “Customers feel the price is fair when they understand it. They have knowledge of market rates for this level of quality and know what to expect. There are no surprises.” | Based on my knowledge of fine dining, the prices at this restaurant are appropriate. | To capture the customer’s a priori “Price Knowledge” and comparison frame, which experts identified as a key antecedent to forming a fairness judgment. |

| Price Expectation (PEx) | “The price was what I expected.” (General expectation item) | “The expectation is set by the brand, the location, and the reputation. A high price is fair if it matches these high expectations. The gap determines fairness.” | The prices charged were consistent with the expectations I had for a restaurant of this caliber. | To frame fairness explicitly in terms of the congruence between “Price Expectation” and the actual price, which was a recurring theme in how luxury consumers rationalize high costs. |

| Price Information (PI) | “The price was clearly stated.” (General information item) | “Transparency is key. The menu must be clear, with no hidden charges. Any surcharges should be explained up front. Clarity prevents feelings of being tricked.” | All prices and potential additional charges were clearly communicated to me before I ordered. | To focus on the clarity and completeness of “Price Information” to prevent negative surprises, a procedural aspect of fairness that experts emphasized as critical for trust. |

| Perceived Value (PV) | ||||

| Functional Value (FV) | “The service is reliable.” (Sheth et al., 1991) | “The core function is flawless execution. The meal progresses smoothly, the service is anticipatory, and every detail works. It’s the promise of a perfect, hassle-free experience.” | This dining experience delivered on all its promises in terms of quality and execution. | To define “Functional Value” as the flawless execution of a complex service promise, which is the core utility that luxury consumers are paying for, beyond simple reliability. |

| Hedonic Value (HV) | “This experience was enjoyable.” (Babin et al., 1994) | “The enjoyment comes from the holistic experience—the sensory pleasure, the calm atmosphere, the feeling of doing something good for yourself. It’s an indulgent but guilt-free pleasure.” | The overall experience was a delightful and memorable sensory indulgence. | To specify the nature of “Hedonic Value” as a memorable “sensory indulgence,” capturing the luxurious and multi-faceted pleasure unique to this dining context. |

| Economic Value (EV) | “This restaurant is a good value for the money.” (Dodds et al., 1991) | “Value for money in this segment is not about being cheap. It’s about the feeling that ‘it was worth it.’ The feeling that what you received was greater than the financial cost.” | Considering the total experience, I received excellent value for the money I spent. | To position “Economic Value” explicitly as a holistic “worth it” judgment (total experience vs. cost), which is distinct from a simple price-to-quality ratio. |

| Social Value (SV) | “My friends would think highly of me for using this.” (Sheth et al., 1991) | “This is a place to be seen. Dining here is a signal of status, taste, and success. It’s about social currency, both in-person and on social media.” | Dining at this restaurant enhances my social standing and the image I project to others. | To directly operationalize the critical “Social Value” and status-signaling function of luxury dining, which was identified as a primary, though often unstated, motivator. |

| Customer Satisfaction (CS) | ||||

| Service Quality (SQ) | “The server was helpful.” (General service item) | “Service quality is about professionalism, knowledge, and anticipation. Staff must be able to explain the menu, make recommendations, and be attentive without being intrusive.” | The service provided by the staff was highly professional, attentive, and knowledgeable. | To specify “Service Quality” with the attributes of professionalism, attentiveness, and knowledge, which are the hallmarks of luxury service, not just helpfulness. |

| Timely Service (TS) | “The service was fast.” (General speed item) | “It’s not about speed, it’s about timing. The pacing of the meal must be perfect—not too rushed, not too slow. Dishes must arrive at the right temperature and right moment.” | All aspects of the service were delivered promptly, with a well-paced meal. | To replace the generic concept of “speed” with the more sophisticated and contextually appropriate concept of “Timely Service” and “pacing,” which is critical to a fine-dining experience. |

| Ambience & Surroundings (AS) | “The restaurant’s atmosphere is pleasant.” (Ryu et al., 2012) | “It’s more than ‘pleasant.’ The ambience must transport you. The music, lighting, interior design, and even the scent must create a cohesive, immersive, and exclusive world.” | The restaurant’s overall ambience and surroundings created a special and memorable atmosphere. | To elevate the measurement from a simple “pleasant atmosphere” to the more encompassing and emotive concept of a memorable “Ambience and Surroundings.” |

| Perceived Quality (PQ) | “I am satisfied with the quality.” (Oliver, 1980) | “Satisfaction is a direct result of our quality promises being met or exceeded. When guests acknowledge the high quality, they are expressing a form of satisfaction.” | My experience confirms that this restaurant delivers an exceptionally high level of quality. | To frame a dimension of satisfaction as a cognitive confirmation of “Perceived Quality,” linking the FQ construct to the CS construct as an explicit appraisal of performance. |

| Hotel Image (HI) | “My opinion of this brand is positive.” (Brand equity item) | “The restaurant’s reputation is inseparable from the hotel’s. A good meal reinforces the luxury image of the entire hotel, and that feeling is part of the satisfaction.” | This dining experience has enhanced my overall positive image of the hotel. | To explicitly link satisfaction with the dining experience to the broader “Hotel Image,” which experts saw as a key cognitive outcome and a component of overall satisfaction. |

| Customer Loyalty (CL) | ||||

| Customer Trust (CT) | “I trust this service provider.” (Morgan & Hunt, 1994) | “Trust is the foundation. It’s trust in their food safety, trust that they will consistently deliver, and trust that they will handle any problem with integrity. Without this, there is no loyalty.” | I have complete trust in this restaurant to consistently deliver a safe and high-quality experience. | To operationalize “Customer Trust” as a specific, foundational belief in the restaurant’s competence and integrity, which was identified as a necessary precursor for commitment. |

| Customer Commitment (CC) | “I am committed to this brand.” | “Commitment is the ‘stickiness.’ It’s a psychological decision to stay with us even when a new, trendy place opens. It’s a resilient bond that goes beyond just satisfaction.” | I feel a strong sense of commitment to continue my relationship with this restaurant in the long term. | To capture “Customer Commitment” as a conscious, long-term relational intent, differentiating it from fleeting satisfaction and establishing it as a core component of psychological loyalty. |

| Customer Value (CV) | “I get a lot of value from this relationship.” | “Loyal customers feel they receive ongoing value—not just from one meal, but from the relationship. This could be through recognition, special offers, or just the consistent value they know they’ll get.” | I believe my ongoing patronage of this restaurant provides me with superior value compared to other options. | To capture loyalty’s “Customer Value” dimension, framing it as a cognitive assessment of the superior, long-term benefits derived from the continued relationship. |

| Social Media Engag (SME) | “Our most loyal customers are our digital ambassadors. They post photos, check in, and write positive reviews. This online advocacy is the new word-of-mouth and a clear sign of loyalty.” | I am likely to post positive content about this restaurant on my social media accounts (WeChat, Dianping). | To introduce “Social Media Engagement” as a new, contemporary behavioral dimension of loyalty. This adaptation was a direct result of the qualitative finding that digital advocacy is a primary way modern consumers express their loyalty. | |

| Construct | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Food Quality (PFQ) | 0.912 | 0.933 | 0.678 |

| Price Fairness (PF) | 0.887 | 0.915 | 0.634 |

| Perceived Value (PV) | 0.901 | 0.928 | 0.691 |

| Customer Satisfaction (CS) | 0.924 | 0.945 | 0.712 |

| Customer Loyalty (CL) | 0.898 | 0.921 | 0.655 |

| PFQ | PF | PV | CS | CL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFQ | |||||

| PF | 0.651 | ||||

| PV | 0.703 | 0.688 | |||

| CS | 0.645 | 0.671 | 0.754 | ||

| CL | 0.639 | 0.692 | 0.721 | 0.783 |

| Construct | Step 2: Compositional Invariance (p-Value) | Step 3: Equality of Means (p-Value) | Step 3: Equality of Variances (p-Value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFQ | 0.451 | 0.512 | 0.488 | ||

| PF | 0.389 | 0.401 | 0.423 | ||

| PV | 0.517 | 0.589 | 0.601 | ||

| CS | 0.612 | 0.677 | 0.654 | ||

| CL | 0.404 | 0.432 | 0.465 | ||

| Assessment | Supported | Supported | Supported | ||

| Path | Path: T1 → T2 (β) | Path: T2 → T3 (β) | Hypothesis | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autoregressive Paths | ||||

| PFQ(t−1) → PFQ(t) | 0.58 *** | 0.61 *** | - | Yes |

| PF(t−1) → PF(t) | 0.55 *** | 0.59 *** | - | Yes |

| PV(t−1) → PV(t) | 0.62 *** | 0.64 *** | - | Yes |

| CS(t−1) → CS(t) | 0.60 *** | 0.63 *** | - | Yes |

| CL(t−1) → CL(t) | 0.65 *** | 0.68 *** | - | Yes |

| Cross-Lagged Paths | ||||

| PFQ(t−1) → PF(t) | 0.28 *** | 0.26 *** | H1 | Yes |

| PFQ(t−1) → PV(t) | 0.19 *** | 0.17 *** | H2 | Yes |

| PF(t−1) → PV(t) | 0.25 *** | 0.23 *** | H3 | Yes |

| PFQ(t−1) → CS(t) | 0.11 ** | 0.09 * | H4 | Yes |

| PF(t−1) → CS(t) | 0.15 *** | 0.13 *** | H5 | Yes |

| PV(t−1) → CS(t) | 0.22 *** | 0.20 *** | H6 | Yes |

| CS(t−1) → CL(t) | 0.18 *** | 0.16 *** | H7 | Yes |

| PFQ(t−1) → CL(t) | 0.08 * | 0.07 * | H8 | Yes |

| PF(t−1) → CL(t) | 0.12 ** | 0.11 ** | H9 | Yes |

| Hypothesis: Path | β | t-Value | p-Value | 95% CI [LLCI, ULCI] | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H10: PFQ → PV → CL | 0.052 | 5.11 | 0.000 | [0.038, 0.071] | Yes |

| H11: PFQ → CS → CL | 0.021 | 3.89 | 0.000 | [0.011, 0.035] | Yes |

| H12: PF → PV → CL | 0.063 | 5.86 | 0.000 | [0.047, 0.085] | Yes |

| H13: PF → CS → CL | 0.027 | 4.15 | 0.000 | [0.016, 0.042] | Yes |

| H14: PFQ → PV → CS → CL | 0.031 | 4.98 | 0.000 | [0.022, 0.045] | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, Y.; Muangmee, C.; Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Sattabut, T. Structural Model of Key Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Organic Dining Restaurants Within Green Hotels. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050271

Pan Y, Muangmee C, Meekaewkunchorn N, Sattabut T. Structural Model of Key Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Organic Dining Restaurants Within Green Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality. 2025; 6(5):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050271

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Yingwei, Chaiyawit Muangmee, Nusanee Meekaewkunchorn, and Tatchapong Sattabut. 2025. "Structural Model of Key Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Organic Dining Restaurants Within Green Hotels" Tourism and Hospitality 6, no. 5: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050271

APA StylePan, Y., Muangmee, C., Meekaewkunchorn, N., & Sattabut, T. (2025). Structural Model of Key Determinants of Customer Loyalty in Organic Dining Restaurants Within Green Hotels. Tourism and Hospitality, 6(5), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp6050271