Abstract

This article deals with the potential use of by-products from Třinecké železárny company—namely steelworks slag and spent foundry sand (SFS)—as an alternative to natural aggregate in the production of high-strength concrete. The aim of the study was to design and experimentally verify two concrete mixtures. For the first mixture (Mixture 1), natural aggregate was fully replaced by steelworks slag. For the second mixture (Mixture 2), the replacement was made by a combination of steelworks slag and SFS in the same volume ratio. The results have shown that Mixture 1 achieved a strength class of C70/85 and was classified as high-strength concrete. In contrast, Mixture 2, despite optimization of the composition, only achieved a strength class of C35/40, which does not allow for its classification as high-strength concrete.

1. Introduction

The use of converter slag as a partial and complete substitute for natural aggregate in concrete was successfully verified within the framework of research and development in Třinecké železárny, a. s. The use of this by-product brings several benefits—not only by saving natural raw materials and a reduction in costs for concrete production, but also safe and efficient disposal (solidification) of the material which often does not meet the requirements for the use of waste as backfill material according to Table 5.2 in Decree No. 273/2021 Coll.

The subsidiary company Slévárny Třinec, a. s., which is a producer of spent foundry sand (SFS), is striving to find a suitable way of their utilization. The annual production of foundry sands in the Czech Republic amounts to approximately 800,000 tonnes, with less than 10% being recycled. In practice, SFS is used, for example, in mixtures with water glass, bentonite, or cement. On a global scale, it is also used in the overlaying and neutralization of waste in landfills, in cement production, as a filler in asphalt mixtures, or as an opening material in brick production [1]. It can also serve as a soil additive or as part of soilless substrates for plant cultivation. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) supports their use in agriculture due to their proven low environmental risk and ability to improve the physical properties of soil [2].

However, SFS may contain contaminants such as heavy metals or phenols, so thorough quality testing is essential before its use to ensure that the environmental and health standards are met. A key factor for its use is a stable and suitable chemical composition depending on the specific application [3].

Based on the experience gained during the development of concretes with the substitution of natural aggregates by metallurgical by-products at Třinecké železárny company, a study was designed to verify the possibility of adding SFSs to concrete mixtures. Due to the fine fraction of these sands, a concrete formula with a high cement content that could achieve the parameters of high-strength concrete was designed. The fine grains (up to 125 µm) act as a micro aggregate, contributing to the formation of a denser cementing compound. This improves the waterproofing of concrete and its resistance to chemical interaction.

2. Determination of the Properties of the Secondary Raw Materials Used

Converter steelworks slag (CSS) fr. 0/8 mm and spent foundry sand (SFS) fr. 0/4 mm from Třinecké železárny, a.s. were used for the experimental research. The CSS and SFS samples were tested for grain size determination according to EN 933-1 [4] and for bulk density and absorptive capacity according to EN 1097-6 [5]. The determination of bulk density and absorptive capacity was carried out using a pycnometric method and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bulk density and absorptive capacity of CSS fr. 0/8 mm and SFS fr. 0/4 mm.

3. Concrete Mixture Formula Design

When using spent foundry sand (SFS) in concrete mixtures, it is necessary to take into account the possible risk of an alkali–silica reaction (ASR), which can lead to undesirable volume expansion and damage to concrete. This reaction occurs when the alkaline hydroxides present in cement react with certain forms of silicon dioxide, such as opal or tridymite, which may be found in SFS. The result of this reaction is an expansive gel capable of binding water, leading to the formation of cracks and disruption of the cohesion of the concrete [3,6,7].

The main factors influencing the likelihood of ASRs include the composition of the aggregate used—especially the content of reactive forms of silicon dioxide—and the content of alkaline oxides (Na2O and K2O) in cement. The higher the content of these components, the greater the risk of ASR occurrence. In addition to the chemical composition, external conditions such as ambient humidity, temperature, concrete permeability, and exposure time also play a role [8].

To limit or prevent ASRs, microsilica (silica dust) was added to the designed mixtures, which serves as an effective pozzolan. Microsilica reacts chemically with calcium hydroxide to form stable calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), thereby reducing the pH and increasing the density of the concrete structure. This limits moisture penetration and prevents the dissolution of reactive silicates, which significantly reduces the risk of the formation of expansive gels [9].

The designed concrete mixture formula was developed with the aim of achieving the parameters of high-strength concrete, specifically a minimum strength class of C50/60. Natural aggregate was completely replaced by by-products from metallurgical production at Třinecké železárny, a. s. Finely ground blast furnace granulated slag from Kotouč Štramberk and Portland slag cement CEM II/A-S 42.5R were used as the binders. MasterEase 1030 superplasticizer and RheoMATRIX 100 viscosity control additive were used to ensure the mixture’s workability.

Two variants were prepared in order to evaluate the effect of SFS on the properties of the resulting concrete: a comparative mixture without SFS (see Table 2) and a mixture with the addition of SFS (see Table 3). These formulations made it possible to verify how the presence of foundry sands affects the mechanical properties and resistance of the resulting concrete.

Table 2.

Formula of Mixture 1—comparative formula HSC based on CSS fr. 0/8 mm.

Table 3.

Formula of Mixture 2—formula of HSC based on CSS fr. 0/8 mm and SFS fr. 0/4 mm.

4. Production of Test Specimens

Test specimens were produced for concrete testing in order to determine the properties of hardened high-strength concrete according to the designed formulas for Mixtures 1 and 2 (see Table 2 and Table 3). A total of 240 dm3 of concrete mixture was mixed and 94 test specimens were produced. Of these, 36 were cubes with an edge length of 100 mm, 24 were cylinders with a diameter of 100 mm and a height of 200 mm, 30 were prisms with dimensions of 100 × 100 × 400 mm, and 4 were troughs to determine shrinkage.

Filler and microsilica were dosed into the mixing drum and half of the mixing water was added. The mixing time for these components was 120 s. This was followed by the addition of the required amount of cement and finely ground blast furnace slag and the second half of the water. The mixing time was 120 s. The additives were added afterwards in the required quantities and the concrete mixture was mixed for 300 s. The total preparation time for one batch was 540 s.

The test specimen molds were filled in two layers, with one layer compacted for 8 s on a vibrating table. The total compaction time for fresh concrete was 16 s. After compacting the top layer, excess concrete was removed with a trowel and the surface was smoothed with a smoothing trowel to level it with the surface of the mold. The treated surface of the test specimens was protected with foil to prevent water evaporation from the fresh concrete and to avoid disrupting the cement hydration process. The formwork of the test specimens was always removed on the second day and the test specimens were then placed in a water bath at a temperature of 20 °C.

5. Fresh Concrete Tests

5.1. Determination of Consistency

The consistency of the fresh concrete mixture was determined by a cone slump test in accordance with EN 12350-2 [10]. The cone slump test was performed immediately after mixing the concrete mixture. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Measured values of cone slump test for Mixtures 1 and 2.

The cone slump test value for Mixture 1 (CSS) corresponds to slump level S5, i.e., a very fluid mixture. The cone slump test value for Mixture 2 (CSS + SFS) corresponds to slump level S4, i.e., a fluid mixture.

5.2. Determination of Bulk Density and Air Content in Fresh Concrete

The test of the bulk density of fresh concrete and the air content in fresh concrete were performed in accordance with EN 12350-6 [11] and EN 12350-7 [12]. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Bulk density and air content in fresh concrete.

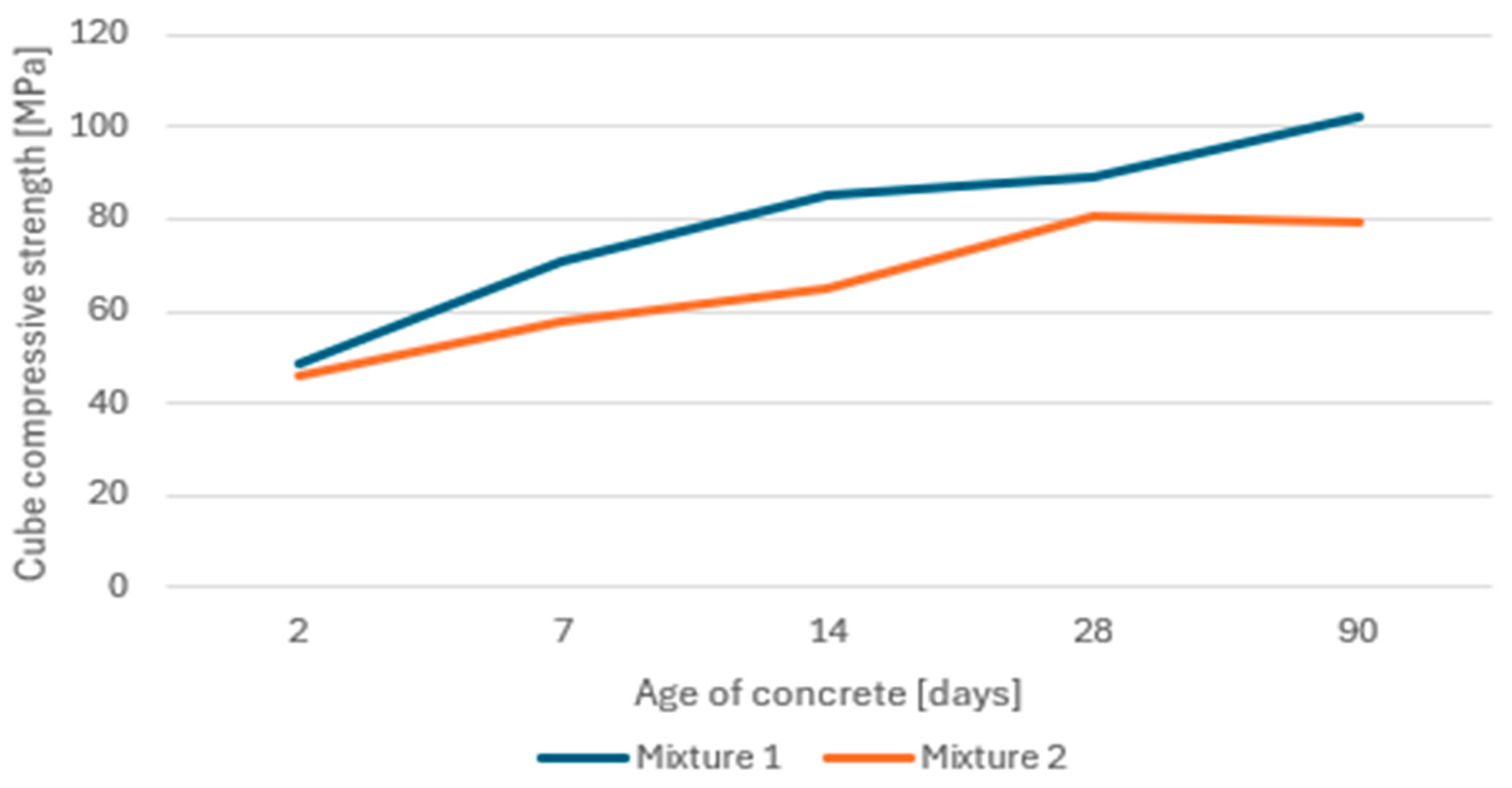

5.3. Cube, Prism, and Cylindrical Strength of Hardened Concrete

The cube strength of hardened high-strength concrete was tested after 2, 7, 14, 28, and 90 days, always on one set of test specimens (one set consisted of three test specimens). The prism and cylindrical strength were tested only after 28 and 90 days, also on one set of three test specimens. Before the actual test, the dimensions of the test specimen and its weight were always determined, and the bulk density was calculated. The measured values of cube strength are presented in Figure 1, and the values of prism and cylindrical strengths measured after 28 and 90 days of concrete hardening are shown in Table 6.

Figure 1.

Cube compressive strength of concrete test specimens.

Table 6.

Prism and cylindrical strengths of concrete test specimens.

The graphic expression of the cube strength of high-strength concrete based on by-products from Třinecké železárny, a.s. shows that Mixture 2 (based on CSS and SFS) achieves lower values compared to Mixture 1 (based on CSS). A very high increase in initial strength was observed and, after 2 days, the cube strength values of the concretes produced according to the designed formulas were almost equal. A significant difference in cube strength was evident after 7 days of concrete age, when the difference between the cube strength values of the tested mixtures was 12.7 MPa (approx. 18%). After 28 days, the cube strength of the designed mixture with SFS reached 80.3 MPa, which is 9.1 MPa (approx. 10%) worse than the reference mixture without SFS. The greatest difference in the strengths of the compared concretes was determined after 90 days, when a significant increase in the cube strength of Mixture 1 was evident, while Mixture 2 with SFS content did not show any further increase. After 90 days of concrete hardening, the strength without SFS was 22% higher.

From the measured values of cube, prism, and cylindrical strengths, it is possible to determine the ratio of fc, prism/fc, cube and the ratio of fc, cylinder/fc, cube. The results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Values of strength ratios after 28 and 90 days.

Table 7 shows that the value of the ratio of fc, prism/fc, cube after 28 days is the same for Mixture 1 and 2. After 90 days, a decrease in this ratio is evident for Mixture 1. This decrease is due to the higher value of the cube strength after 90 days. Table 7 also shows that the value of the ratio of fc, cylinder/fc, cube after 28 and 90 days is almost identical for Mixture 1 and 2. When comparing the values of the ratio of fc, cylinder/fc, cube between Mixtures 1 and 2, a significant difference is already apparent. This difference is caused by the low cylindrical strength value of Mixture 2 after 28 and 90 days. The significant reduction in cylindrical strength in Mixture 2 is caused by the addition of SFS. SFS causes the expansion of fresh concrete, which is associated with the formation of longitudinal cracks in the concrete structure. These cracks, which occur during the hardening of fresh concrete, cause a significant decrease in strength, especially in cylindrical strength, after 28 and 90 days.

5.4. Flexural Tensile Strength

The flexural tensile strength test of concrete was carried out in accordance with ČSN EN 12390-5. The flexural tensile strength was determined after 28 and 90 days of concrete age, always on one set of test specimens produced according to the designed formulas. Prisms with dimensions of 100 × 100 × 400 mm were used as the test specimens. Six prisms were produced for the purpose of the test. Before the actual test, the dimensions, weight, and bulk density of the specimens were determined. The results of the flexural tensile strength tests of the high-strength concrete are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Flexural tensile strength of the concrete test specimens.

The test results show that the flexural tensile strength after 28 days of the reference mixture without SFS is 1.3 MPa (approx. 14%) higher than that of the mixture with SFS. The same difference in strength between the mixtures was maintained even after 90 days of concrete hardening. By comparing the cylindrical strength values at 28 and 90 days, a noticeable increase in flexural tensile strength of 0.5 MPa (approx. 5%) can be observed for Mixture 1. For Mixture 2, there is also a noticeable increase in strength between 28 and 90 days of 0.5 MPa (approx. 6%).

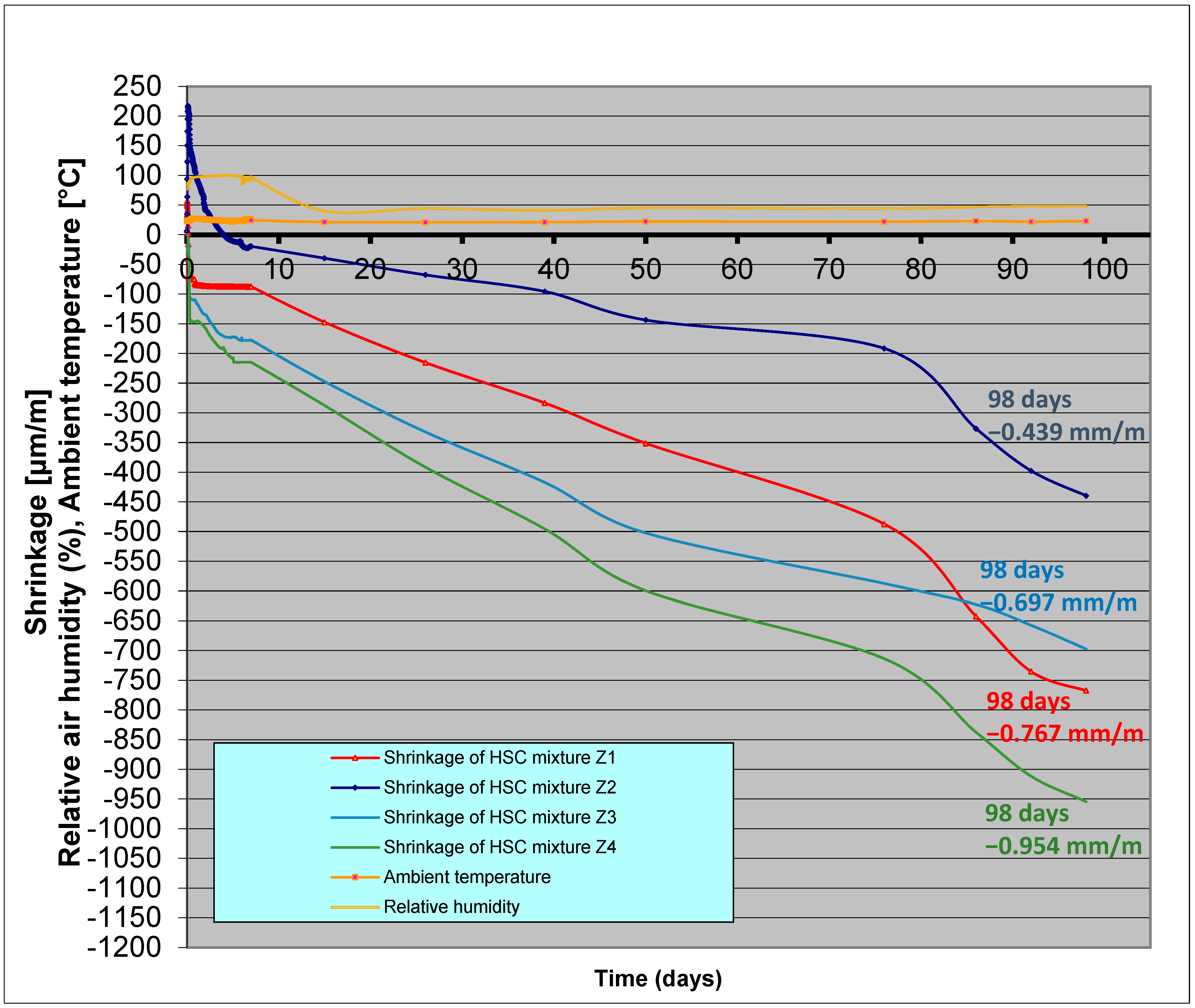

5.5. Determination of Concrete Shrinkage

The shrinkage of concrete for Mixtures 1 and 2 was determined using the trough method, where two 100 × 60 × 1000 mm troughs from Schleibinger Company were used to produce the test specimens. The test specimens for the shrinkage test were stored in a humid environment for 8 days and from day 8 to day 98 in a laboratory environment at a temperature of 21.0 °C. The parameters of the concrete samples produced according to Mixtures 1 and Mixture 2’s formulas for the concrete shrinkage test are presented in Table 9. The shrinkage values of concrete produced according to Mixture 1 and Mixture 2’s formulas are presented in Table 10.

Table 9.

Parameters of concrete samples produced for determining concrete shrinkage.

Table 10.

Concrete shrinkage values after 28 and 90 days.

In the case of Mixture 2 (based on CSS and SFS), an expansion process was observed prior to shrinkage. In the case of Mixture Z1, the volume increase process lasted 0.13 days and the maximum elongation value was 0.056 mm m−1; in the case of Mixture Z2, the volume increased for 4 days and the maximum elongation value was 0.217 mm m−1. The average swelling value was 0.137 mm m−1. A graphical representation of the length changes in the test specimens during the 98-day test is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Shrinkage of concrete Mixtures Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this research focused on the use of by-products from Třinecké železárny, a.s company for the production of high-strength concrete has yielded interesting findings. Mixture 1, containing steelworks slag, met the requirements for classification in strength class C70/85, which proves its suitability for use as high-strength concrete. Mixture 2, which included a combination of steelworks slag and spent foundry sand (SFS), only achieved strength class C35/40, which indicates insufficient strength for classification as high-strength concrete.

The results of the research indicate that the addition of SFS carries certain risks, such as swelling and the associated formation of microcracks during initial setting, which negatively affects the final mechanical properties of the concrete. This undesirable effect is probably caused by the reactions associated with the aluminum content, which can react in the presence of water and calcium hydroxide to release hydrogen, leading to the formation of gases and subsequent microcracks in the concrete structure [13]. This fact was confirmed during the shrinkage tests, where expansion was observed in the SFS mixture during the first hours of concrete curing.

In the future, research could follow the direction of the experimental verification of the effectiveness of anti-shrinkage additives, which could contribute to reducing shrinkage and improving the overall performance of SFS-based concrete. These steps could contribute to a wider and more effective use of industrial waste materials in the construction industry, which would lead to a reduction in environmental impact and greater sustainability of building materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Z. and V.V.; methodology, V.V.; validation, A.E. and T.D.; formal analysis, P.Z.; investigation, J.Š. and M.D.; resources, V.V.; data curation, M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, P.Z.; writing—review and editing, V.V. and A.E.; supervision, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Třinecké železárny, a.s. under research order No. 089/4501292294. The APC was funded by VSB—Technical University of Ostrava.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data created or analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors P.Z. and M.D. were employed by the company Třinecké železárny, a.s. Author J.Š. was employed by BETOTECH, s. r. o. The material investigated in this study originated from Třinecké železárny, a.s, and the research was funded by Třinecké železárny, a.s., with the aim of exploring potential applications for this material. These affiliations did not influence the objectivity of the study. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Profi Press. Molding Mixtures from Foundries. Waste. Available online: https://odpady-online.cz/formovaci-smesi-ze-slevaren/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Beneficial Uses of Spent Foundry Sands. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/smm/beneficial-uses-spent-foundry-sands (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Chifflard, P.; Schütz, M.; Reiss, M.; Foroushani, M.A. Evaluating Chemical Properties and Sustainable Recycling of Waste Foundry Sand in Construction Materials. Front. Built Environ. 2024, 10, 1386511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 933-1; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates—Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution—Sieving Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN 1097-6; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Altaf, S.; Sharma, A.; Singh, K. A Sustainable Utilization of Waste Foundry Sand in Soil Stabilization: A Review. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioli, F.; Abbà, A.; Alias, C.; Sorlini, S. Reuse or Disposal of Waste Foundry Sand: An Insight into Environmental Aspects. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, C.H.; Bradshaw, S. User Guideline for Foundry Sand in Green Infrastructure Construction; University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alkali-Silica Reaction in Concrete. Available online: https://www.understanding-cement.com/alkali-silica.html (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- EN 12350-2; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 2: Slump-Test. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 12350-6; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 6: Density. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 12350-7; Testing Fresh Concrete—Part 7: Air Content. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- Reakce Hliníku a Čerstvé Cementové či Anhydritové Směsi. Materiály pro Stavbu. Available online: https://imaterialy.cz/rubriky/beton/reakce-hliniku-a-cerstve-cementove-ci-anhydritove-smesi_45268-html/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).