1. Introduction

Auxetic materials and structures belong to a distinctive class of mechanical systems characterized by a negative Poisson’s ratio. Unlike conventional materials, which contract laterally under tensile loading and expand laterally under compression, auxetic structures exhibit the opposite behaviour. They expand laterally when stretched and contract laterally when compressed. This counterintuitive response stems from engineered geometries, such as re-entrant honeycombs, chiral lattices, and rotating-unit designs [

1,

2].

These unique deformation mechanisms endow auxetic architectures with enhanced properties, including improved energy absorption, superior fracture resistance, increased shear stiffness, and remarkable indentation resilience [

3]. Such traits render them promising for applications in protective systems, biomedical implants, aerospace components, and energy-absorbing devices [

4,

5]. Consequently, research on auxetic structures has flourished, encompassing analytical, numerical, and experimental studies [

6,

7,

8].

The rise in additive manufacturing has further propelled advancements in this field by enabling precise fabrication of intricate geometries. Among several techniques, stereolithography (SLA) has proven particularly advantageous for fabricating auxetic lattices due to its high resolution and ability to produce smooth, defect-free surfaces that reduce stress concentrators [

9]. Additionally, the development of high-toughness photopolymer resins for SLA further supports the creation of robust auxetic structures capable of withstanding substantial deformation [

10].

Despite these developments, the literature has predominantly focused on compression scenarios [

10,

11] or on idealized analytical and numerical modelling [

6]. Experimental insight into the tensile behaviour of auxetic lattices remains limited. Likewise, the role of geometric refinement, such as using filleted corners to alleviate stress concentration and facilitate smoother deformation, has not been systematically investigated, especially in SLA-fabricated auxetic structures. The present work addresses this gap by examining the mechanical response of re-entrant auxetic lattices fabricated via SLA under both compression and tension. Combining finite element analysis with experimental validation, deformation mechanisms, energy absorption capacity and failure modes are assessed in both a standard re-entrant design and its counterpart with corner fillets, offering an understanding of how geometry and high-resolution additive manufacturing influence mechanical behaviour.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Design

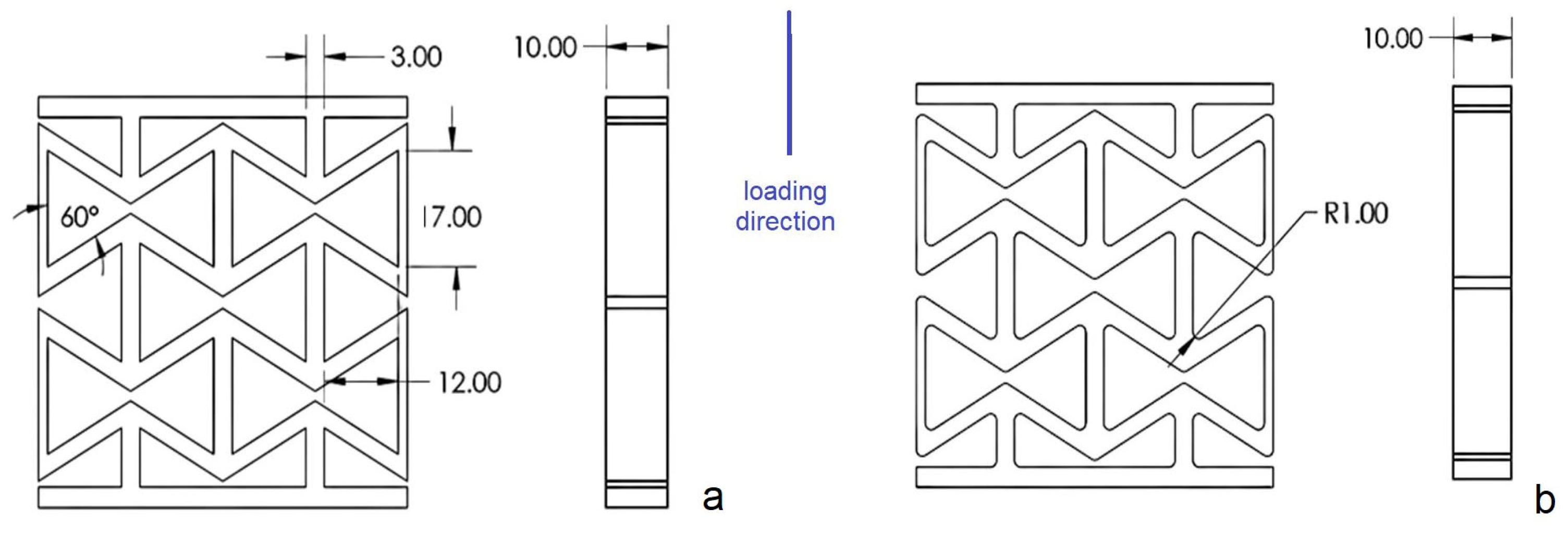

Two re-entrant auxetic lattices were studied: a reference design and its filleted variant in which sharp internal corners were rounded to reduce local stress concentration. Both designs share identical in-plane dimensions of 54 × 54 mm

2 and a thickness of 10 mm. Geometric parameters of the re-entrant cell, such as cell angle (60°), strut length (17 mm), and strut thickness (3 mm), were preserved across the two configurations. In the filleted design, corner radius was set to R = 1 mm, introducing a smoother stress distribution compared to the sharp-cornered reference design. The two designs are illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Material

Specimens were printed with an Anycubic™ Tough Resin™ (Shenzhen Anycubic Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). Manufacturer data for the cured resin are: density 1.10–1.15 g·cm

−3, tensile modulus 0.8–1.2 GPa, tensile strength 50–60 MPa, elongation at break 30–50%, and Izod impact strength >50–60 J·m

−1 [

12]. These values informed the elastic material model used in the simulations.

2.3. Additive Manufacturing Process

The specimens were fabricated using an Anycubic™ Photon Mono X2™ stereolithography printer (Shenzhen Anycubic Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). The build orientation was selected so that the printed layers were parallel to the principal loading direction for both compression and tension specimens. Printing files were prepared to minimize support scars on load-critical surfaces and to ensure dimensional accuracy. After printing, the specimens were cleaned in isopropyl alcohol to remove uncured resin, supports were carefully detached, and post-curing was carried out according to the resin manufacturer’s recommendations to achieve full polymerization and consistent mechanical properties. Post-curing was performed in an Elegoo Mercury X UV chamber (Shenzhen Elegoo Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, Guangdong, China)at room temperature (25 °C) for 7 min, which provided uniform irradiation from all sides and ensured complete solidification of the resin.

2.4. Finite Element Analysis

Numerical simulations were carried out in SolidWorks Simulation™ 2023 (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France) to replicate the mechanical response of the auxetic lattices under compression and tension. A linear elastic material model was adopted to capture the initial structural response and enable direct comparison with the small-displacement experimental regime.

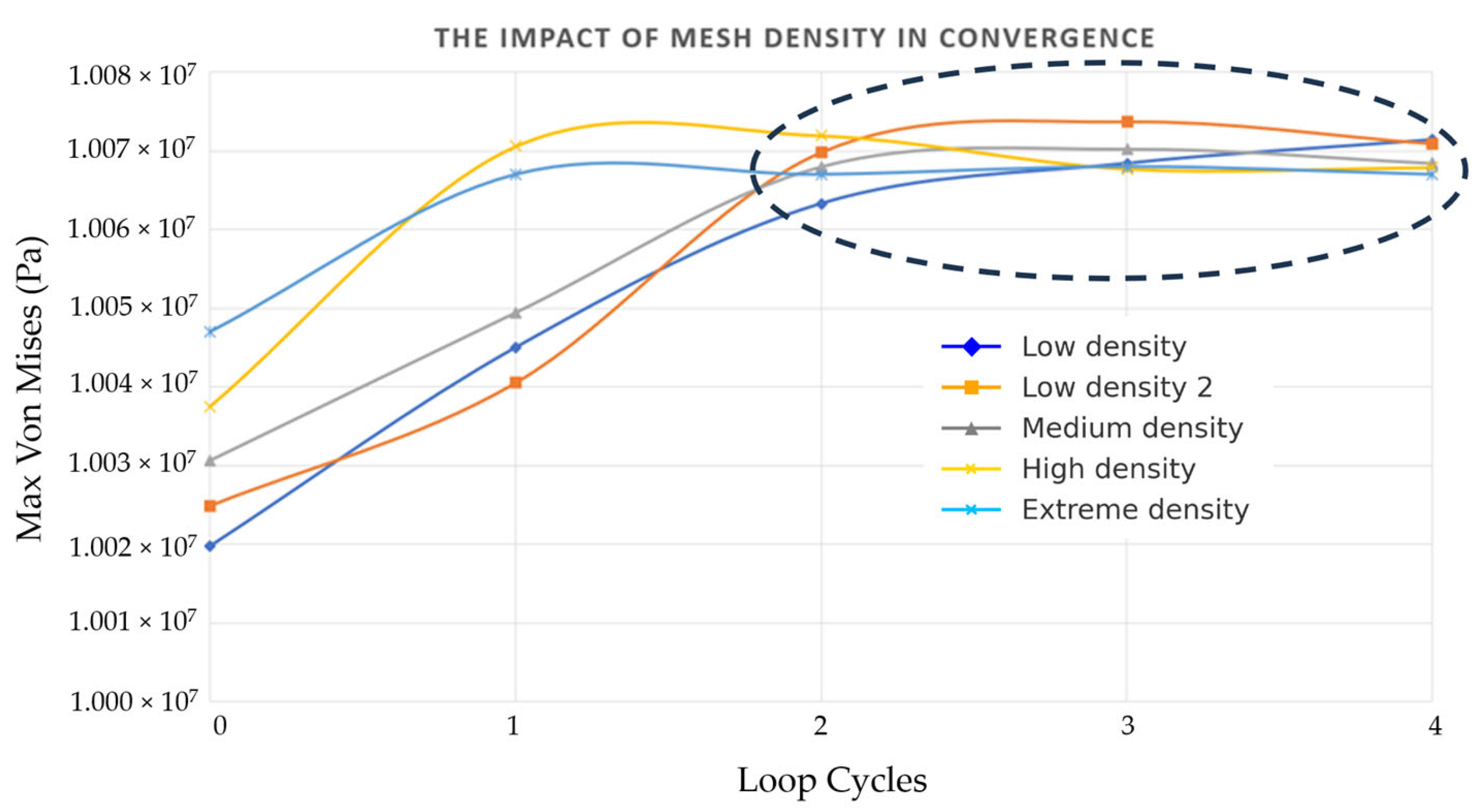

An h-adaptive meshing strategy was implemented, whereby the mesh was automatically refined in regions of high stress gradients (e.g., at filleted corners) and coarsened in regions of uniform stress. The accuracy of the mesh was evaluated through a convergence study of the maximum von Mises stress (

Figure 2). Five different initial mesh densities were considered: Low density 1, Low density 2, Medium density, High density, and Extreme density, to examine the effect of starting element size distribution on convergence. Low density 1 and Low density 2 correspond to two independent coarse meshes with slightly varied initial discretizations, included to confirm that the convergence behaviour was independent of the starting mesh configuration. Results demonstrated that beyond two refinement cycles, stress variations became negligible across all initial densities, confirming mesh independence. All simulations were therefore conducted with four refinement cycles, ensuring a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency.

For the compression simulations, the structure was placed between a rigid top platen, subjected to a prescribed vertical displacement, and a fully fixed bottom platen. For the tensile simulations, one grip was constrained while a uniform displacement was applied to the opposite side. Lateral faces of the specimen were left traction-free to allow natural Poisson’s effect. Global load–displacement curves were obtained from the reaction forces recorded at the loaded boundaries.

2.5. Mechanical Testing

Quasi-static tests in compression and tension were carried out on an InstronTM 4482 universal testing machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). For compression, the crosshead applied a 12 mm total displacement at a speed of 5 mm·min−1. For tension, specimens were pulled to failure at a constant rate. Deformation was recorded using the machine extensometer and synchronized photos, allowing qualitative comparison of deformation modes between experiment and simulation. For the elastic-range validation, the reference lattice was compressed to 3 mm axial displacement so that direct comparison with the linear simulations was possible.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Compression Behaviour

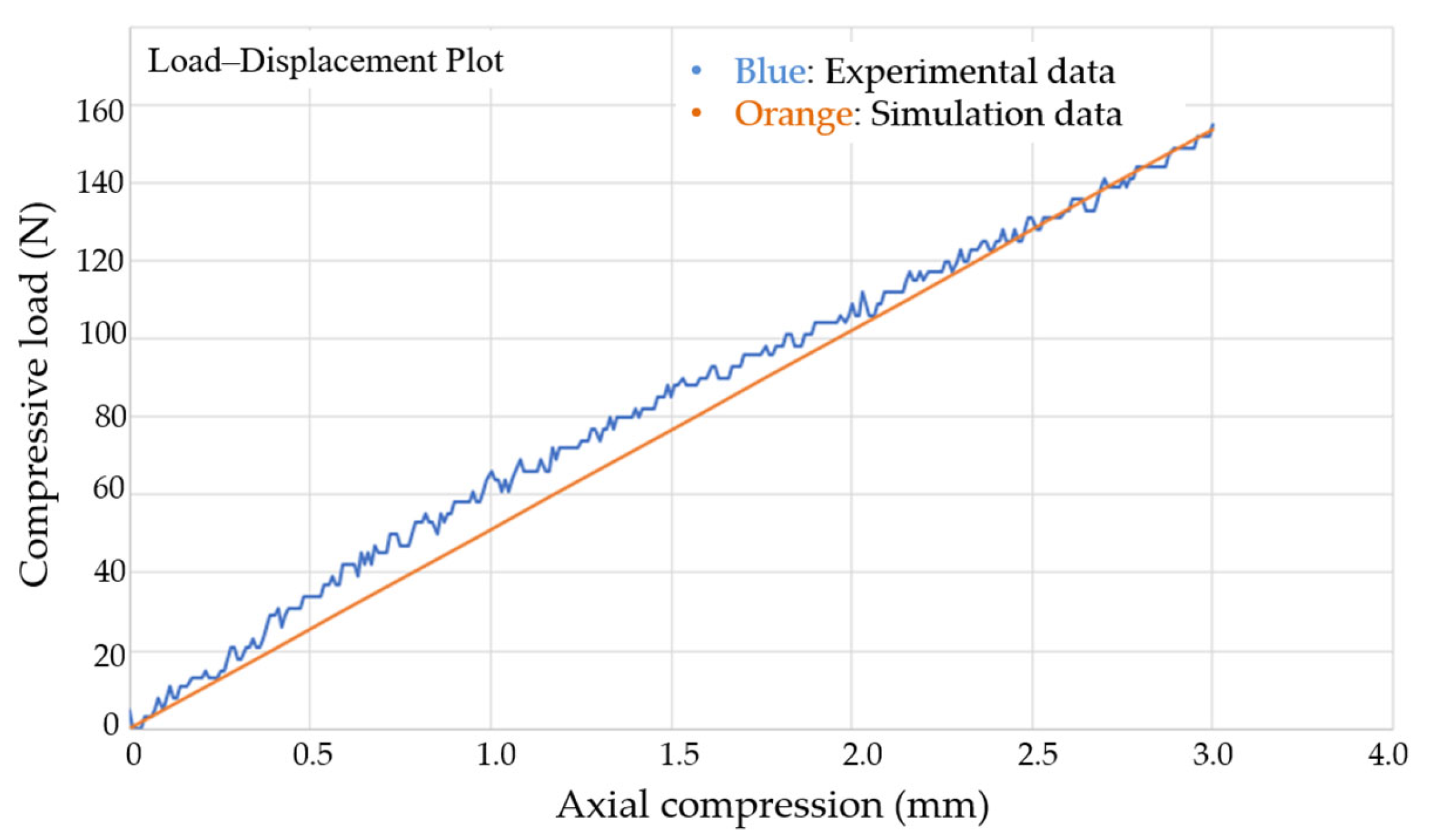

The initial comparison between simulation and experiment confirmed the validity of the elastic response prediction. As shown in

Figure 3, both numerical and experimental results displayed very similar deformation patterns, including localized curvature at the specimen edges during load application. The corresponding load–displacement curves (

Figure 4) exhibited strong agreement up to 3 mm of compression, with only a 6.7% relative error in absorbed energy between simulation and experiment confirming the reliability of the finite element model for further analysis.

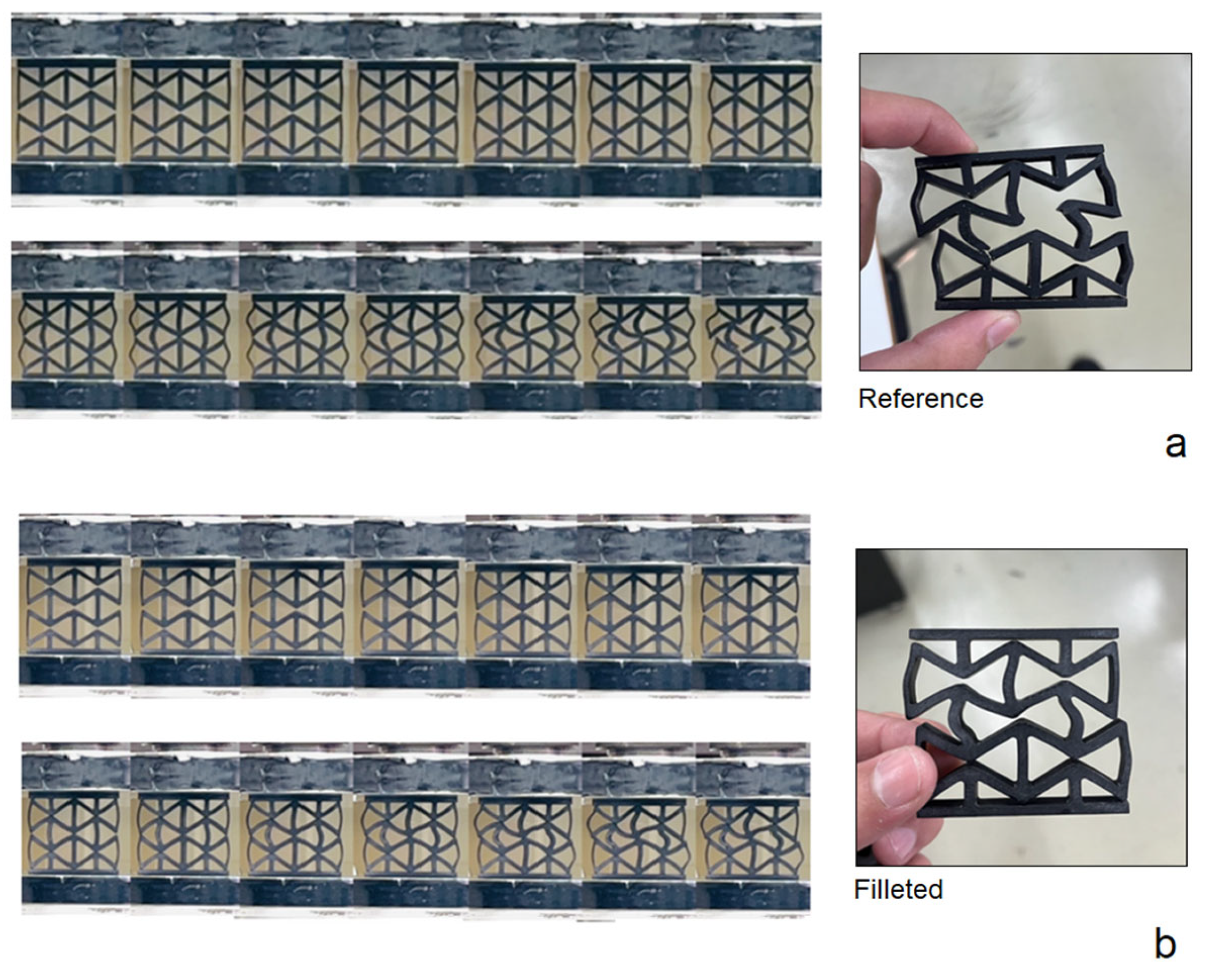

Beyond the elastic region, clear differences emerged between the two geometries. The deformation sequence of the reference and filleted re-entrant structures is presented in

Figure 5. The reference design displayed abrupt buckling and asymmetric collapse, leading to localized failure and fracture of one wall. In contrast, the filleted structure deformed more gradually, with no broken walls, showing improved symmetry compared to the reference geometry and damage tolerance.

These behaviour differences were also reflected in the load–displacement response (

Figure 6). The reference geometry reached a higher peak load (~3.4 kN) but exhibited brittle collapse immediately afterward. Conversely, the filleted geometry sustained a lower maximum load (~2.7 kN) earlier peak and smoother post-peak response, thus preserving stability over a wider strain range and delaying catastrophic failure.

Energy absorption analysis based on the area under the load-displacement curves of

Figure 6 revealed that the reference design achieved a higher total absorption (19.8 J) compared to the filleted structure (16.3 J). However, the distribution of energy absorption differed significantly. In the reference structure energy concentrated around the peak load and the structure collapsed abruptly, while the filleted geometry absorbed energy more smoothly as it deformed. This smoother response suggests greater suitability for applications requiring controlled failure and progressive load dissipation.

3.2. Tensile Behaviour

Under tensile loading, both geometries exhibited auxetic expansion through rotation of the re-entrant cells, but their failure mechanisms diverged significantly (

Figure 7).

The reference specimen fractured abruptly, separating into two parts after limited extension, reflecting a brittle failure mode with a lateral deformation of approximately 1 mm. In contrast, the filleted geometry underwent progressive unfolding, delaying crack initiation and reaching lateral deformations of about 3.5 mm before final rupture. No complete wall breakage occurred, indicating improved ductility and structural continuity.

Numerical analysis corroborated these experimental findings. Von Mises stress concentrations were predicted at the same strut junctions where cracks appeared in the tests (

Figure 8). The redistribution of stresses in the filleted geometry allowed the auxetic units to rotate further, thereby postponing critical failure.

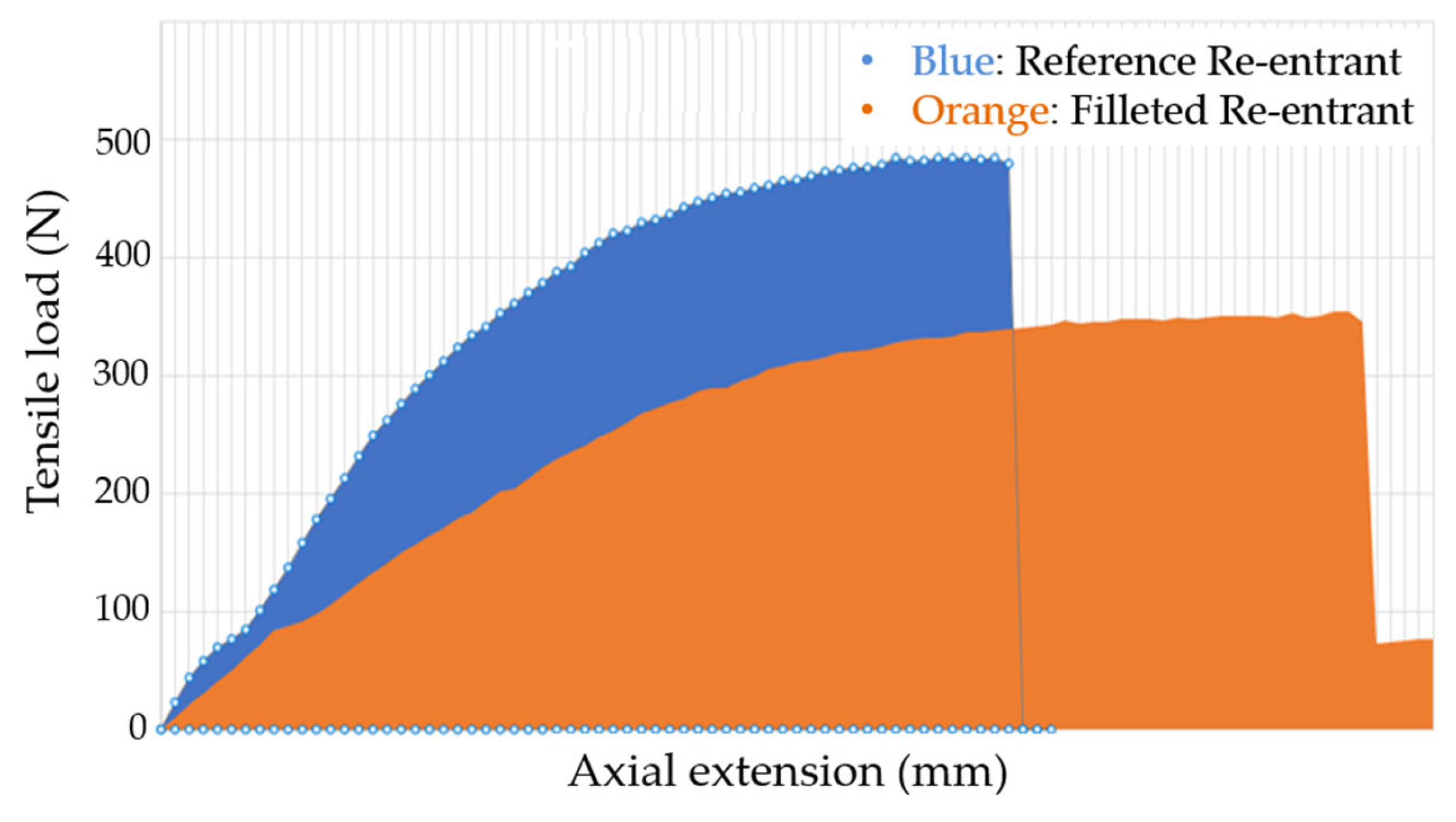

The tensile load–displacement curves (

Figure 9) illustrate this difference clearly. Although the reference design sustained a slightly higher peak load, it failed catastrophically at small extensions. The filleted variant reached a lower maximum load but accommodated a much broader strain range and absorbed slightly more energy (4.18 J versus 4.10 J). This trade-off emphasizes that while peak strength is reduced, ductility, toughness, and predictability are enhanced. Such a response is especially valuable in applications where large reversible deformations and avoidance of sudden fracture are critical, such as biomedical implants or energy-absorbing systems.

4. Conclusions

This work examined the deformation and energy absorption of SLA-fabricated re-entrant auxetic lattices under compression and tension, comparing a reference geometry with sharp corners to a filleted variant.

The results show that geometric refinement strongly influences structural performance. The reference geometry demonstrated higher peak strength and greater energy absorption under compression but exhibited slightly lower energy absorption under tension. In both cases, it failed abruptly through localized buckling or brittle fracture, respectively. In contrast, the filleted design, although slightly weaker in peak load, redistributed stresses more effectively, enabling smoother deformation, larger strains under tension, and improved damage tolerance under compression. This trade-off highlights that corner filleting is an efficient strategy to enhance ductility and predictability at the expense of maximum strength.

These findings are particularly relevant for applications where structural reliability and controlled energy dissipation are prioritized over absolute strength, such as protective systems, biomedical implants, and crash-resistant aerospace components.

Future work will extend the investigation to dynamic and cyclic loading conditions, assess the influence of multi-material SLA printing, and integrate topology optimization and generative design approaches to identify geometric designs that simultaneously maximize energy absorption and structural stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.-C.V.; methodology, G.-C.V. and I.P.; validation, A.S.; investigation, A.S.; resources, G.-C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.; writing—review and editing, G.-C.V.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, G.-C.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yang, W.; Li, Z.M.; Shi, W.; Xie, B.H.; Yang, M.B. Review on auxetic materials. J. Mat. Sci. 2004, 39, 3269–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Das, R.; Tran, P.; Ngo, T.D.; Xie, Y.M. Auxetic Metamaterials and Structures: A Review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.E.; Alderson, A. Auxetic Materials: Functional Materials and Structures from Lateral Thinking! Adv. Mater. 2000, 12, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Lin, C.; Wu, F.; Li, Z.; Liao, J. Lattice structures with negative Poisson’s ratio: A review. Mat. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, V.A.; Senatov, F.S.; Veveris, A.A.; Skrybykina, V.A.; Díaz Lantada, A. Auxetic Metamaterials for Biomedical Devices: Current Situation, Main Challenges, and Research Trends. Materials 2022, 15, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Photiou, D.; Silk, R.; Gibson, M.A.; Todd, I.; Hague, R.; Todd, R. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of 3D-Printed Auxetic Structures Using Additive Manufacturing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farshbaf, S.; Dialami, N.; Cervera, M.; Bakhshan, H.; Chakherlou, N.T. Enhancing the Mechanical Performance of Additively Manufactured Auxetic Structures Through Design Modifications: Experimental and Numerical Analysis. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 4143–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavidelnia, N.; Malekzadeh, P.; Rafiee, A.; Kadkhodaei, M. Idealized 3D Auxetic Mechanical Metamaterial: Analytical, Numerical, and Experimental Validation for Re-Entrant Structures. Materials 2021, 14, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.; Mahesh, V.; Harursampath, D. On the Application of Additive Manufacturing Methods for Auxetic Structures: A Review. Adv. Manuf. 2021, 9, 342–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malekan, M.; Sigurjónsson, B. On the mechanical behavior of polymeric lattice structures fabricated by stereolithography 3D printing. Eng. Rep. 2024, 6, e13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomarah, A.; Masood, S.H.; Sbarski, I.; Faisal, B.; Gao, Z.; Ruan, D. Compressive properties of 3D printed auxetic structures: Experimental and numerical studies. Virt. Phys. Prototyp. 2019, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anycubic Co., Ltd. Tough Resin Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://eu.anycubic.com/products/tough-resin-2-sale-for-resin-3d-printer?variant=51415176020286 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).