Abstract

Integrating emerging Industry 4.0 technologies into smart factories has been widely discussed, particularly challenges regarding the practical use of a blockchain; one remaining challenge is the role of a blockchain beyond logistics and traceability, as well as its ability to support explicit trust measurement in real industrial environments. Existing studies often treat trust as a conceptual or cloud-oriented construction, without linking it to measurable production events. This study proposes a blockchain service-level agreement (SLA) to measure trust at an open-source frugal smart factory (SF). Trust is defined as a dynamic quantitative score derived from measurable process events, including estimated and response times, assembly correctness, and transaction outcomes; all of this is calculated through a smart contract implemented on a blockchain network. The approach is implemented in a tangram puzzle assembly process that integrates cyber-physical systems, edge computing, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, data analytics, cybersecurity, and the blockchain within a unified SF architecture. The framework was experimentally validated across four representative assembly scenarios: (i) the SF delivered the puzzle in time and was correctly assembled ( = 0.1734), (ii) the puzzle was completed within tolerance time ( = 0.0649), (iii) the puzzle was delivered on time and was incorrectly assembled ( = 0.0005), and (iv) the puzzle was completed outside the tolerance time and was correctly assembled ( = 4.91 × ); demonstrating that the model accurately estimates expected assembly times and updates trust without manual intervention during a physical manufacturing task, addressing the limitations of prior conceptual and cloud-based approaches. The main research contributions include an operational SLA-based trust model, the demonstration of the feasibility of applying blockchain-based SLAs in a physical SF environment, and evidence that a blockchain can be justified as a mechanism for managing and measuring trust in SF, rather than solely for traceability or logistics.

Keywords:

service-level agreement; trust; blockchain; smart contract; smart factory; open-source; Industry 4.0 1. Introduction

A smart factory (SF) is composed of the use of common automation with the incorporation of new technology trends; it promotes the migration from automation to digitization [1,2]. Digital transformation (DT) includes data analysis, big data, automation robots, simulation, the Internet of Things (IoT), cybersecurity, cloud computing, 3D printing, augmented reality, and others; it helps companies gain competitive advantages by improving their organization flexibility and resilience and enhancing their dynamic capacity [3]. Small and medium enterprises play a vital role in promoting technological innovation, and concerning technology trends, they have not been fully explored or are in the research phase; their features need to be proven to understand the challenges, compatibility, and support with different technologies, and the human factor involved [4,5,6,7,8].

One of these new technological trends is the blockchain (BC). According to Vashishth et al. [9], the most important blockchain applications include financial services, healthcare, voting systems, and cryptocurrency. Additionally, Lee et al. [10] identified the blockchain as a novel decentralized architecture and distributed computing paradigm, with features such as trust, security, chronological data, and collective maintenance [11]. Particularly, the blockchain has become a technological trend in the manufacturing sector, but the potential use of its attributes (immutability, transparency, audibility, decentralization, etc.), operational costs (computational, gas, transaction times, etc.), trust (data breaches, user and service provider conditions through a smart contract, response times, etc.), traceability (origin, supply chain, etc.) remain unclear. Specifically, the blockchain challenges for the manufacturing system implementation include storage capacity, implementation costs, real-time implementation, specific consensus mechanisms, trust and reliability, scalability, and security, among others [12,13,14,15].

In the same way, an important challenge to overcome within the SF environment is the adequate representation of reciprocal agent–device trustworthiness for device collaboration, including device reliability, reputation, and trust measures [16,17]. As has been observed, a common challenge mentioned within the state of the art is trust, because it is linked to digitization challenges, including security issues and a lack of digital culture [18,19]. To clarify the concept of trust applied to smart manufacturing, Kohn et al. [20], presented a review of the concept of trust in automation (TiA), mentioning that trust is the integration of a small set of popular self-report measures (for example, a checklist for trust, the dynamic reporting of trust, and a trust scale, among others); at the same time, it is defined as a rich and complex construct that involves a multitude of measures and approaches to study. Jeong et al. [21] stated that trust is an important factor for information sharing among devices in smart manufacturing systems because it is related to reliability and secure operations at a factory. They identified two types of trust: (i) trust in performance (regarding what a trustee will do) and (ii) trust in a belief (regarding what a trustee believes). Tan et al. [22] investigated the building of a trust model in cloud computing, identifying that it is required to define (i) how to reduce the effect of a subjective evaluation on a trust score, (ii) how to prevent collusion cases of cloud service consumers, (iii) how to prevent cloud providers from providing malicious fake services, (iv) the ability to update trust scores dynamically, and (v) a more comprehensive excavation on trust factors.

Alternatively, the integration of the blockchain and smart contracts has been explored in fields such as data storage and management, big data, cloud computing, and network management; the most common applications are oriented toward the IoT and industrial processes through the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) and smart contracts [23]. In recent years, the use of service-level agreements (SLAs) has been linked with blockchain and smart contracts because it is possible to design a framework for the definition and enforcement of SLAs in a blockchain by transforming them into smart contracts [24,25]. The application of the SLAs has been limited to the cloud, the edge, or the IoT, but actually, their case of use in an SF architecture has not been explored yet; this represents an area of opportunity to explore their interconnection, pros and cons, challenges, and implementation. To clarify the SLA concept, Raza et al. [26] defined an SLA as a key document between a service provider and a consumer that binds them for a certain period with the commitment of defined services regarding service provision terms and quality [27]. As mentioned by Azzahra et al. [28], SLAs specify what service the providers are delivering to their customers, containing information about the parameters that are specified by metrics. Similarly, Badshah et al. [29] mentioned that penalties in the SLA are imposed on the supplier to satisfy customers, so they defined a threshold value for SLA metrics such as response times, execution times, availability, and bandwidth.

After the above information was analyzed, several gaps were identified, including a lack of operational trust models that map measurable real-world events to a quantitative trust score, limited demonstrations of SLAs implemented using a blockchain at a physical SF, and little evidence demonstrating how an SLA-based trust mechanism can be integrated with edge, cloud, and automated devices for real-world assembly tasks. Specifically, this paper addresses these gaps by designing, implementing, and evaluating an SLA Trust model embedded in Smart Contracts and deployed in an open-source Frugal SF environment. This work considers Trust as a quantitative score derived from measurable SLA conditions, connecting Edge agents, MQTT (Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) communication, and Blockchain. This work evolves Trust from a conceptual model to a more automated mechanism applicable to real manufacturing processes. The research is focused on presenting a new proposal to measure trust in an SF assembly process, through an SLA (validation of the customer requirements) based on the blockchain, integrated with cyber–physical systems (CPS), edge computing (EC), artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing (CC), data analytics (DA), and cybersecurity (CS). The proposed model represents trust as a dynamic score calculated using various SLA conditions; unlike previous studies, this research implements and validates a blockchain-based trust model within a frugal SF process. In summary, the core theoretical contribution of this paper focuses on measuring trust as a computable attribute based on an SLA, using blockchain, and derived from measurable physical events. From a practical perspective, this study presents the design, implementation, and validation of an SLA deployed in an open-source, frugal SF assembly process. Unlike prior studies that remain conceptual or cloud-oriented, the proposed approach integrates multiple smart factory subsystems, allowing trust measurement within a physical process.

Regarding the structure of this manuscript, the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the related work on the blockchain, smart contracts, and SLAs in an SF environment, as well as the research that integrated the terms of trust and SLAs. Section 3 explains the integration of the new technology trend (blockchain) into a defined open-source SF architecture, indicating the BC interconnections with the other elements (CPS, EC, AI, CC, DA, and CS), and identifies the parameters, metrics, and penalties to measure trust through an SLA. Section 4 explains the case study to test the SLA in the open-source SF and also details the SLA parameters, metrics, and penalties. Section 5 presents the results of the SLA parameters, metrics, and penalties applied to the SF. Furthermore, Section 6 interprets the proposed SLA-based trust model, reviewing the experimental findings. Finally, insights, limitations, and future work are summarized in Section 7.

2. Literature Review

In recent years, the application of a blockchain in the SF has begun to be investigated due to its characteristics (immutability, transparency, auditability, decentralization, etc.), and as a result, the blockchain could be the key to solving SF challenges. Although traditional databases enable efficient data handling, their centralized architectures expose them to single-point failures; in contrast, the blockchain offers a decentralized scheme that provides data integrity and traceability. Furthermore, its immutability and auditability represent a more effective way to manage sensitive and distributed information in SF environments. Particularly, for a blockchain in the SF scope, some cases include solutions to the SF and integrate a secure and private model through blockchain and IIoT (sensing, management, storage, and application layers); see ref. [30]. On the other hand, there are models for resource management in the SF (centralized model) that can interact and organize through smart contracts and based on a multi-agent approach and ERP organizational strategy [31]. Specifically, Liu et al. [32] explain the applicability of a blockchain in the customization of different products, presenting a collaborative customization framework to moderate, maintain, and manage a decentralized consensus on customization by automating transactions through smart contracts. Additionally, smart contracts are electronic transaction protocols that execute the terms of a contract to satisfy common contractual conditions; they are a secure and unstoppable computer program representing an agreement that is automatically executable (when a certain condition is met) and enforceable [33,34].

Furthermore, the integration of smart contracts with the blockchain has developed several architectures, for example, the case of Yalcinkaya, which presented a Blockchain reference architecture for the ISA95-compliant traditional and smart manufacturing systems, where the smart contracts are included as a fundamental part of the ledger tier; the smart contracts interact with the integration tier (MQTT Broker) and the enterprise tier (ERP—Enterprise Resource Planning, certificate authority, the enterprise API—Application Programming Interface, and the database) [35]. Additionally, Teslya et al. [36] also present a blockchain-based platform architecture for the IIoT, where smart contracts are used to process and store the information of the Smart-M3 platform. Finally, Kochovski et al. [37] presented a smart contract architecture to provide SLA management for decentralized computing environments such as virtual machines, cloud services consumers, and cloud providers.

Concerning the use of an SLA in the SF, an SLA is an agreement between a user (SF customer) and a service provider (SF) regarding service provision terms and quality; for this reason, the SLAs are considered documents that specify what service the providers are delivering to their customers [27,28]. In the same way, recent investigations about the SLA application are oriented toward (i) developing technology and applications for cloud manufacturing [38], (ii) cloud SLA using smart contracts and key techniques to ensure trust [39], (iii) SLA monitoring for IoT ecosystems through the smart contract and the blockchain [40], and task-scheduling problems to optimize SLA satisfaction in terms of the number of tasks whose hard deadlines are met for device–edge–cloud cooperative computing [41].

An SLA presents different challenges, such as the use of licensed–protected applications, or the specifications required for the modification of existing agreements (re-negotiation), through cloud computing environments; there are also gaps in the current mechanisms for negotiating and creating SLAs in cloud environments. Another important aspect mentioned by Hamdi et al. [42] is that SLAs have just been integrated into environments such as the cloud, the edge, or the IoT; the main applications for the quality of service (QoS) were uptime, throughput, availability, latency success/fail rates, response times, etc. Equally importantly, several studies have been conducted concerning the implementation of the SLA to solve trust issues, which is a research niche in the use of DLTs in the SF; some of them include the research of Uriarte et al. [24], which proposes an SLA model for cloud manufacturing in Industry 4.0, integrating the blockchain and smart contracts (SLABSC) to address trust issues among cloud service providers (CSPs), cloud service consumers (CSCs), and third-party monitoring. The proposed method provided data security and was used to supervise cloud service providers to ensure better services.

In the same way, Zhou et al. [39] presented a model for enforcing trustworthy cloud SLAs using smart contracts and game theory, particularly focusing on the use of blockchain technology and introducing the possibility of detecting and reporting SLA violations (unbiased random selection, the payoff function, the Nash equilibrium, and witness audits), aiming to address the challenges of trust in traditional cloud SLAs. The model is implemented using smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain and is demonstrated to be feasible through experimental studies. Table 1 synthesizes representative studies on the blockchain, smart contracts, smart factories, and SLA-based trust models, highlighting their focus, implementation status, and measured outcomes to position the contribution of this work within the existing research landscape.

Table 1.

Comparative overview of blockchain, smart factory, and SLA-based Trust research, summarizing each study’s main features.

According to the prior art reviewed, an SLA based on a blockchain to measure the trust in an SF has not been proposed, nor has one been proposed that provides flexibility, adaptability, and digitization to the SF simultaneously. The proposed research presents the integration of technology trends (for the manufacturing field) in an SF architecture, intending to maintain the features of the SF (digitization, flexibility, and adaptability). The most important characteristic is the full integration with open-source software, to use an SLA for Trust measurement in an assembly process. Our proposal can serve as a good alternative for small and medium enterprises’ digital transformation to reach Industry 4.0 requirements. In summary, only a limited number of studies have addressed trust measurement through SLAs embedded in a blockchain. Specifically, the research by Tan et al. [38] and Zhou et al. [39] represents the closest approach, as they also propose trust mechanisms based on SLAs combined with smart contracts. However, these studies remain at a conceptual level or focus on cloud-oriented environments. In contrast, this research implements a blockchain SLA Trust model within a frugal smart factory environment. The proposed approach measures trust throughout an entire assembly process (integrating all elements of the smart factory, not just the cloud), representing a more robust and complex evaluation of trust under realistic operating conditions. For this reason, this work constitutes one of the first implementations of an SLA trust model embedded in smart contracts and experimentally validated in a smart factory environment. Based on the gaps identified in the existing literature, particularly the lack of experimentally validated SLA-based trust models in smart factory environments, the next section presents the proposed methodology, detailing the system architecture, trust model, and SLA formulation.

3. Methodology

To address the gaps identified in the literature, this section presents the methodology adopted in this research. For clarity and conceptual consistency, the key terms used throughout the manuscript are first defined and standardized. Subsequently, a subsection describing the blockchain integration into a defined SF architecture is presented, explaining the interconnection with the SF elements, the process interactions, and the protocols. The third part reviews the parameters, metrics, and penalties required to implement the SLA agreements in order to ensure the measurement of trust. Finally, the description of the SLA for a trust measurement algorithm is explained, detailing the steps implemented in the smart contract to ensure that SLA conditions have been satisfied.

3.1. Terminology and Definitions

For clarity and consistency throughout this manuscript, the key terms are used with the following meanings. A smart factory (SF) refers to a manufacturing environment integrating cyber–physical systems, edge computing, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, data analytics, cybersecurity, and a blockchain. Trust is defined as a quantitative and dynamic score computed from measurable process-level events. A service-level agreement (SLA) denotes a formal set of measurable conditions, metrics, and penalties governing the manufacturing service. The blockchain refers to the distributed ledger infrastructure and its associated smart contracts used to automate SLA enforcement and trust computation. These definitions are applied consistently across all sections to avoid ambiguity and ensure conceptual coherence.

3.2. Smart Factory Architecture

Nowadays, a diversity of SF architectures has been studied in an attempt to explain how emerging and trending Industry 4.0 technologies can be integrated into SF architectures [43]. An example is the open-source SF architecture presented by Fortoul-Diaz et al. [44], composed of technological trends (CPS, EC, AI, CC, DA, and CS) integrated to demonstrate tangram assembly puzzles; these kinds of architectures are compatible with industry tools for transitioning conventional facilities into digitized facilities [43,45]. A pending challenge is estimating the level of trust between the customer and the factory to produce a good. To overcome this challenge, an SLA based on BC as a tool to measure trust is proposed, enhancing the SF features (flexibility, adaptability, and digitization) and compatibility together. The proposed solution to this challenge is explained in detail below.

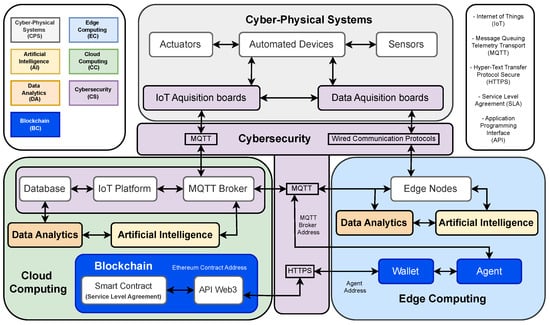

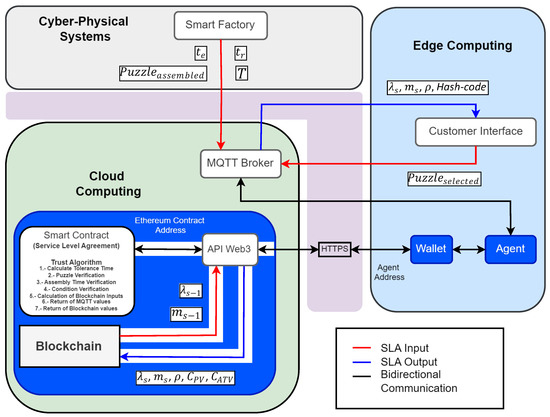

As revealed in Figure 1, the integration of a blockchain into the SF architecture implies running different components on the edge and cloud computing, as happens with the DA and AI that run in both computing. For instance, a blockchain running on the cloud requires the deployment of smart contracts (Sepholia), the definition of the contract address (Ethereum Contract Address), and the Web3 API (Alchemy or Infura) that acts as a bridge, attending to the connections between the agent and smart contract that are deployed on the edge and the cloud, respectively. On the other hand, the components running on the edge include the agent and the wallet. The agent invokes the smart contract through the remote procedure call (RPC) or Web3 API, using the Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS); the connection with the physical components is established through the Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol using a broker server.

Figure 1.

Proposed open-source smart factory architecture integrating seven elements: cyber–physical systems (CPSs), edge computing (EC), artificial intelligence (AI), cloud computing (CC), data analytics (DA), cybersecurity (CS), and a blockchain (BC). The colored regions highlight each component, and the rows represent how they interconnect through different communication protocols.

Both connections are bidirectional, which means that the agent can start the connection or wait for data. In conjunction, the wallet (Metamask) stores the agent’s private keys on the edge to control the transactions’ flow, and the agent uses funds to pay the gas. Moreover, there are two types of interactions: consulting events and transactions. First, consulting events are interactions that do not modify the state of the blockchain (they do not require gas consumption or a new blockchaining). Second, transactions are interactions that modify the state of the blockchain (they require gas consumption and a new blockchaining). As a result of both interactions, a hash code is generated, and the agent always starts the interaction by invoking the smart contract.

3.3. Trust, Penalties, and Rewards Model

In fact, Tan et al. [22] mention that the parameters to monitor trust can also be used to determine whether the SLA agreements are met; the trust score can be updated after the completion of a transaction, it is essential to the quality of service and the interests of the consumers, and it involves parameters such as availability, reliability, integrity, the average degree of fulfillment, similarity, and the integrated value. Additionally, the implicit factor of the successful rate helps determine the trust score, and it represents a positive stimulus for providers; it is calculated using Equation (1):

where denotes the mean of the total transactions (successful transactions), denotes the previous result of transactions (equal to the sum of , related to each previous transaction), is the actual value of the successful transaction (1 if successful and 0 if failed), and is the number of transactions. The maximum score of tends to 1 (100%) because this is a normalized value.

Equally importantly, Badshah et al. [29] mention that reliable monitoring develops trust between the customer and the service provider (factory) because the monitoring process is performed according to the agreed conditions in the SLA. The SLA formal expressions have an if–then structure, which means that specific actions will be performed when the conditions are met. Moreover, penalties () are imposed on the supplier (factory), taking into account the threshold values agreed in the SLA, which means that the customer benefits from failure in the delivery of services or goods (for example, by paying lower or free costs). Some SLA metrics related to monitoring are the response time, the execution time, and availability, among others. In particular, the response time represents the waiting time for the consumer’s requirement (time invested to complete the process), depending on the availability of the resources.

The () is calculated as follows:

where is the condition of puzzle verification, is the condition of the assembly time verification, is the penalty tolerance (given in case of the estimated time being exceeded and accorded at the beginning of each SLA), and is the percentage penalty (percentage value of ). According to Equation (2), there is no penalty () when both conditions ( and ) are met through the SF.

Indeed, when is not reached but is reached, there is a percentage penalty ( = ). On the other hand, when none of the conditions are met by the factory, a total penalty is applied (). Failure to comply with the agreements within the SLA also represents a negative point for the supplier, since this directly impacts the factory trust (successful transactions). In conjunction, the rewards can be applied to the SF only if the task was correctly performed ( = 1); the rewards for a SF consist in no penalization (the price remains without changes, ( = 0); according to Badshah et al. [29], customers always receive economical benefits due to SF penalization, and it is expected that the SF will complete the terms and conditions previously stipulated. Finally, for this research, we define trust in an SF as a set of individual measurements (availability, response time, successful transactions, etc.), related to the process success or failure carried out within the factory to estimate a level of trust (score) between the customer and the factory to produce a good. We also define an SLA applied to SF as a set of rules (conditionals such as if, else, or if–else) via an embedded algorithm (e.g., blockchain smart contracts) in edge (agent and wallet) and cloud (API Web3) computing that incorporates the terms (the goods to be fabricated) and conditions (estimated time and tolerance time) negotiated between the customer and the factory. At least, the SLA should include (i) service parameters (successful transactions), (ii) specific measurable metrics (response time), and (iii) penalties (cost reduction in the goods’ price) evaluated according to the set of rules agreed upon between the customer and the factory.

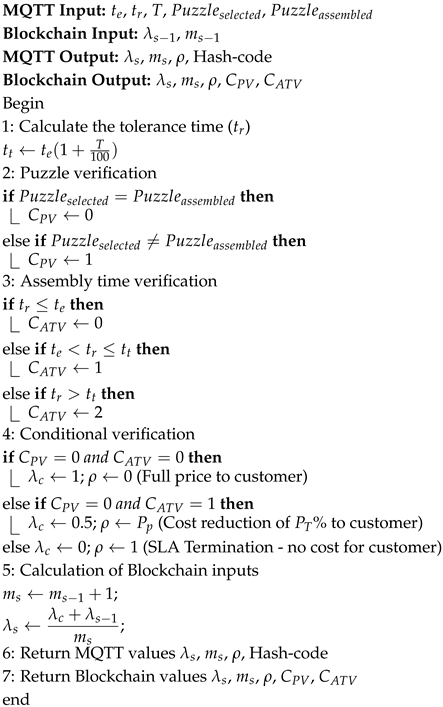

3.4. SLA for Trust Measurement Algorithm

Once the concepts of trust measurement, SF penalties and rewards, and metrics are defined, a smart contract is designed to execute the set of rules. The smart contract receives or sends data from the MQTT broker and the blockchain. With respect to the MQTT inputs, the MQTT broker sends the estimated time () calculated by the factory to complete the assembly process (a detailed explanation of the calculation will be given in Section 4.3), the response time () that the SF takes to complete the assembly process, the tolerance (T, is a percentage) that is used to calculate the tolerance time () to not receive a penalty, the selected puzzle (selected by the customer through an interface), and the final assemble puzzle by the factory (computer vision).

In conjunction, with respect to the blockchain inputs, the previous value of the successful transaction (trust score, ) and the previous value of the number of transactions () are obtained through a consultation of event interactions (it does not modify the state of the blockchain and does not require gas consumption); these are the blockchain inputs. Essentially, the algorithm starts by calculating the tolerance time (), adding the equivalent percentage of the tolerance (T) to the estimated time (). As a second step in the algorithm, the puzzle verification is performed by comparing the assembled puzzle and the selected puzzle to obtain the condition of puzzle verification (, 0 for equal puzzles or 1 for different puzzles). The third step is the assembly time verification, when the values of the estimated time () and the tolerance time () are compared with the response time () to obtain the condition of assembly time verification (, 0 if the estimated time did not exceed the estimated time, 1 if the time is between both limits, and 2 if the tolerance time was exceeded).

Subsequently, in the fourth step, the conditional verification is applied to the values of and to obtain the values of the penalty (, 0 if = 0 and = 0, calculation if = 0 and = 1, and 1 otherwise) and the actual value of the successful transaction (). In the fifth step, the calculation of the number of transactions () and the new values of the successful transactions () is performed. After the calculation and conditional verification, in the sixth step, the smart contract sends to the MQTT Broker the new values of the successful transactions (), the new value of the number of transactions (), the penalties () calculated for the factory (as a percentage for cost reduction to the customer), and the hash code as a result of the transaction with the blockchain; these are the MQTT outputs. Finally, in the seventh step, the smart contract generates a new transaction (requires gas consumption and new blockchaining) to include in a new block the new values of the successful transactions (), the new value of the number of transactions (), the penalties () calculated for the factory (as a percentage for cost reduction to the customer), the value of the condition for puzzle verification (), and the value of the condition for assembly time verification (); these are the Blockchain outputs. To sum up, Algorithm 1 summarizes the proposed SLA for a trust measurement algorithm implemented as a smart contract, detailing how inputs from the smart factory and blockchain are processed to compute the trust score, penalties, and updated transaction history.

The trust algorithm based on the SLA conditions was implemented through the smart contract deployed in the blockchain. The SF sends the input parameters of the trust algorithm to the agent (running on the edge) through the MQTT protocol. Subsequently, the agent (using the wallet) invokes through the HTTP protocol the smart contract (using the API Web3) evaluating the input parameters according to the set of rules (SLA conditions) and obtaining as a result the trust score and the penalty for the SF. A detailed explanation of this algorithm and its implementation in the SF is presented in Section 4.4. In brief, integrating a blockchain into the architecture fulfills SF flexibility (the ability of the production system to reconfigure efficiently) feature; it proves that the SF can work even if a new technology trend is added as an essential part of the architecture. In the same way, the SLA set of rules accomplishes the SF adaptability (quickly adjusts to changes in product demand) feature, because the conditionals adjust to the customer’s requirements. In fact, the SF digitization feature is reached through the smart contract because it allows the conversion of physical input into cyber data. Finally, the three fundamental features (flexibility, adaptability, and digitization) of the SF are met, verifying that the interconnection of the seven elements allows the validation of the SF architecture.

| Algorithm 1: SLA for Trust Measurement |

|

The SLA for the trust measurement algorithm is implemented as a blockchain smart contract. The algorithm shows how the contract receives MQTT inputs from the smart factory and blockchain inputs and then evaluates the SLA conditions to compute the new trust score. The resulting SLA outputs are sent back to the SF via MQTT and the Sepolia Blockchain to provide immutable and traceable trust records.

3.5. Modeling Assumptions and Constraints

To ensure the viability and stability of the proposed trust measurement approach, we propose several experimental approaches. First, we assume that the devices in the Frugal SF operate reliably and provide accurate and uninterrupted time measurements during the tangram assembly process. Additionally, the expected time and tolerance values defined in the SLA are considered representative of real operational conditions. Finally, the smart contract is executed without variability introduced via the network, and the number of samples in the case study is sufficient to validate the algorithm. The model also presents certain constraints. First, it is restricted to a Frugal SF environment, where the case study may not reflect all conditions of large-scale industrial operations. Furthermore, once the smart contract is deployed, it cannot be modified. Finally, the penalties and rewards are based on fixed rules, and the measurement relies on quantitative metrics, making it difficult to assess the qualitative nature of the process.

Based on the assumptions and constraints described above, the proposed methodology is instantiated and evaluated through an open-source smart factory case study. For this reason, the following section details the implementation and experimental setup adopted to validate the proposed approach, including the smart factory layout, the hardware and software configuration, and the deployment of the SLA blockchain-based smart contract.

4. Implementation and Experimental Setup

The proposed SLA-based trust measurement algorithm was implemented within an open-source smart factory architecture. The first subsection explains the asset’s location in the layout of the SF and the assembly process. The second part presents the technical configuration of the hardware and software in the SF. Finally, the SLA implementation describes the parameters, metrics, and penalties described in Section 3.3 to achieve the trust measurement through the design of a smart contract, so the integration between the blockchain element and the SF is validated.

4.1. Case Study: SLA Implementation in the SF

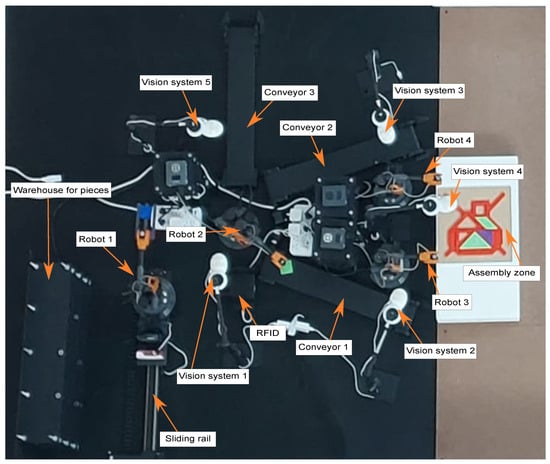

This case study aimed to test the interaction between the elements (CPS, EC, AI, CC, DA, CS, and BC) of the open-source SF architecture presented in Figure 1; the SF process was composed of different stations to achieve the tangram puzzle assembly. Solving the tangram puzzle is relevant due to its capacity to generate multiple valid configurations involving diverse geometric shapes, sizes, and colors; all pieces must be used without overlap, and the task effectively assesses the SF’s flexibility and adaptability. Furthermore, it incorporates pick-and-place, assembly, and manipulation actions characteristic of industrial robotic operations. Figure 2 presents the complete layout of the Frugal SF used as a case study, showing the physical arrangement of the Wlkata Mirobot robots, conveyors, vision systems, the RFID module, the warehouse for pieces, and the assembly zone involved in the tangram puzzle assembly process.

Figure 2.

Layout of the Frugal SF for tangram assembly. The layout includes four six-degree-of-freedom Wlkata Mirobot arms, three Wlkata conveyors, one sliding rail, five wireless vision systems, an RFID module, a warehouse for pieces, and an assembly zone, organized into pick-and-place stations that cooperate to complete the assembly process.

In addition, each robot arm has a rack for its peripherals (plug-in charger, robot controller hardware, and pneumatic pump). Particularly, the stations involved in the pick-and-place process for the tangram puzzle assembly included the following: (i) the warehouse station that stores the tangram pieces (24 pieces maximum), (ii) the dispatch station that exchanges pieces between the warehouse and the assembly stations, and (iii) the assembly stations that locate the pieces in the required position of the pallet, according to the puzzle selected by the customer. The SF generally assembled at least four tangram puzzles (birds, houses, rockets, and a swan). The customer selects the target puzzle through a web interface running on the edge; once the pallet for assembly is located in the assembly zone, vision system identifies the pieces required in the pallet and confirms the customer’s requirement to start the assembly. Figure 3 details the three main stations involved in the tangram pick-and-place process, highlighting how the robots, conveyors, RFID, and vision systems collaborate to move each piece from storage to its final position on the pallet according to the customer-selected puzzle. The figure also illustrates the sequential flow of operations: piece retrieval from the warehouse, RFID identification, distribution via conveyors, and final placement via Robots 3 and 4 in the right and left assembly zones.

Figure 3.

Stations of the Smart Factory tangram assembly process: (a) warehouse station, where 24 racks store pieces and Robot 1 retrieves the required piece; (b) dispatch station, where Robot 1 places the piece on the RFID module for tag reading and Robot 2 sends it to the appropriate conveyor; (c) right and left assembly stations, where Robots 3 and 4 pick pieces from the conveyors and place them in their final positions on the pallet according to the selected puzzle.

Next, an ordering algorithm running on the edge creates two-piece arrays to distribute the pieces on each side of the assembly zone (left and right) via Robots 3 and 4. Meanwhile, Robot 1 consults the database on the cloud to verify the position of the piece inside the warehouse; once the row and column are identified, Robot 1 moves through the sliding rail to the warehouse location (see Figure 3a). Subsequently, Robot 1 performs the picking routine and moves to the RFID module, leaving the piece to read the tag information (size, form, and color). The process continues with Robot 2, identifying the position of the piece in the RFID module through Vision System 1 and performing the Behavioral Cloning algorithm, where the centroid of the piece is mapped to the workspace of Robot 2 (see Figure 3b). Once Robot 2 picks the piece, it is placed in the required conveyor belt position (left or right). In addition, if the piece is required to be located on the right side of the assembly, the factory activates conveyor 1; once the piece is located in the vision system 2 area, it executes a Behavioral Cloning algorithm to pick the piece in the workspace of Robot 3. In conjunction, if the piece is required to be located on the left side of the assembly, the factory activates Conveyor 2; once the piece is located in the Vision System 3 area, it executes a Behavioral Cloning algorithm to pick the piece in the workspace of Robot 4. See Figure 3c) for both cases. Additionally, Robots 3 and 4 collaborate to locate the piece in the required position in the pallet puzzle; this characteristic promotes SF flexibility (layout reconfiguration). The previously explained process is repeated for each piece until the tangram puzzle is completed; the main parameters and metrics are stored in reports, and they are also sent as MQTT inputs to the Agent running in the Edge, so the Algorithm 1 (SLA for Trust measurement) can be executed. The setup configuration and devices used in the SF are described in the next subsection.

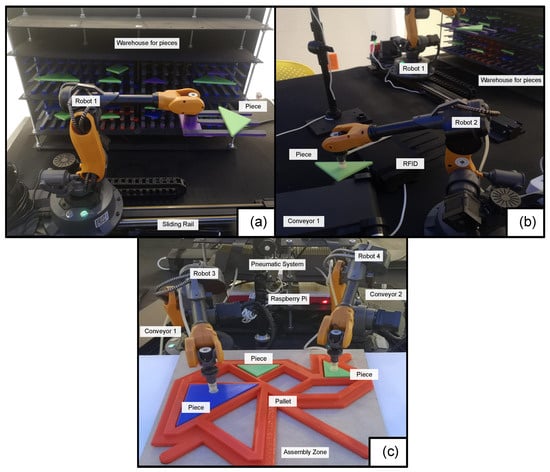

4.2. Experimental Setup

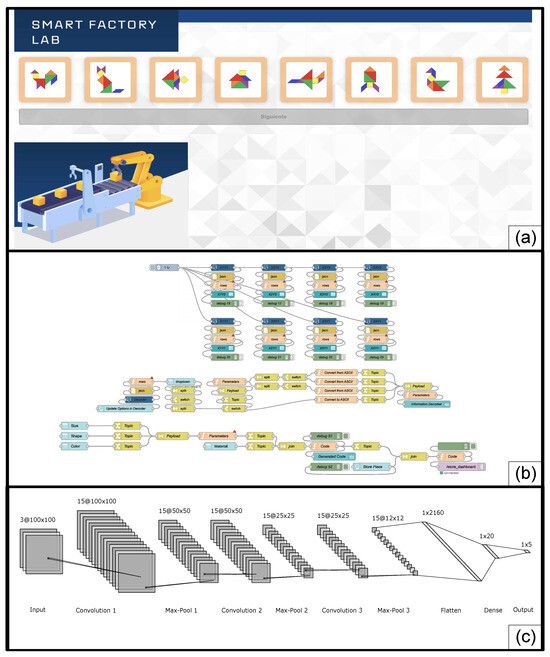

This section describes the configuration, devices, protocols, algorithms, and software used to implement the trust measurement in the tangram puzzle assembly process for an open-source SF with an SLA implemented in a blockchain. Figure 4 illustrates the main software components of the experimental setup used to implement trust measurement in the tangram assembly SF, including the web interface for puzzle selection, node-RED flows for data handling, and the CNN model for piece recognition. In the first part of the experiment, the client selects the puzzle to assemble through the web interface running in edge computing with Python and Flask (version 3) programming (see Figure 4a). Once the puzzle has been selected, Robot 1 (Wkata V.3) mounted on the Sliding Rail (Wlkata V.1) takes out each piece required for the puzzle; according to the Best Fit algorithm [46], each piece is placed on the RFID sensor (RC522) via Robot 1 to read the RFID tag (Mifare Classic 1k NFC Tag RFID). The data is sent to the ESP32 board connected to WiFi to encrypt the information using the AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) algorithm with the CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode, and subsequently, the message is sent to the cloud through the MQTT protocol with a quality of service (QoS) of 2.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup: (a) web interface running on the edge (Python 3.7/Flask) for customer puzzle selection and confirmation; (b) node-RED flows receiving encrypted RFID data from the MQTT broker, decrypting payloads, querying the PostgreSQL database, and updating process information; (c) 10-layer CNN model (convolution, pooling, flatten, dense, and output layers) implemented in Python 3.7 to recognize the tangram piece’s shape, size, and position and integrate its output with the vision system at the edge nodes.

The MQTT Broker (Eclipse Mosquitto V.5) redirects the message to the Node-RED (V.3) platform to decrypt the payload and build a query for requesting the data from the PostgreSQL (V.14) database and comparing information stored in the RFID tag. Some examples of the Node-RED flow for this case study are presented in Figure 4b. Once the RFID information is validated, Robot 2 distributes the piece to the required assembly station (left or right, according to the assembly of the coordinate’s necessary position) through the corresponding conveyor. When the piece reaches the Vision System (number 2 for left side assembly and number 3 for right side assembly), it detects the piece contour, centroid, and orientation through a WiFi HiLook camera (1920 × 1080 pixels) using a Python script implemented through the OpenCV library (version 4.8).

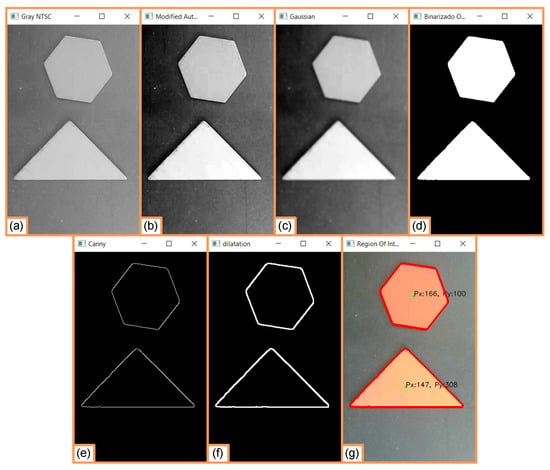

At the same time, the Deep Learning (DL) model analyzes the piece to detect the shape, size, and position through a convolutional neural network (CNN). The proposed dataset used to train the CNN includes 10,000 images (including triangle, square, and rhomboid shapes), each with different features. The CNN model (see Figure 4c) was developed using ten layers (input, first convolution and pool, second convolution and pool, third convolution and pool, flatten, dense, and output) for shape recognition, so the DL output was integrated with the vision system results in the edge nodes. To ensure reliable detection under changing lighting, the vision systems apply a dedicated image-processing pipeline that standardizes brightness and contrast, removes noise, segments the piece, and extracts robust contours and centroids for robotic pick-and-place, as shown in Figure 5. Concerning the robot work-space mapping, each Mirobot arm executes the pick-and-place routine through a Behavioral Cloning algorithm (it uses the demonstrator policy to replicate the actions in unseen scenarios), which maps the location of the piece centroids (px, py) to the physical Cartesian coordinates (X, Y, Z). The result of the calculated position is sent to the assembly robot through the downstream channel, so the piece is picked with the robot´s end-effector (suction cup).

Figure 5.

Vision system preprocessing pipeline for robust piece detection: (a) grayscale NTSC conversion; (b) auto-contrast normalize brightness; (c) Gaussian filter to reduce image noise; (d) Otsu binary threshold to separate the piece from the background; (e) canny edge detection to extract object boundaries; (f) edge dilatation to reinforce weak or discontinuous edges; (g) contour highlight in the region of interest.

To sum up, the edge nodes (Raspberry Pi and Jetson Nano) run the following: (i) the routine scripts (Python 3.7) for the automated devices (robot and conveyor position, visual feedback, and emergency stop), (ii) the DL models (shape, size, and position), (iii) the Behavioral Cloning models (mapping of the piece’s centroid to the robot Cartesian coordinates), and (iv) the cloud information (data exchange using MQTT and HTTPS). Concerning the assembly process, all the information from the sensors, the AI model results, and the Python 3.7 script results are sent to the cloud for processing and storage using upstream communication. Moreover, the IoT platform receives the information from the MQTT Broker and stores the data in the database. In addition, the connections in the cloud between PostgreSQL, Python, and Grafana require configuring the IP address, the port (5432), the database name, and PostgreSQL authentication. Additionally, the information is displayed on dashboards to show the assembly data in real time (Grafana and Node-RED). Finally, when the SF ends the assembly process, the Python 3.7 scripts generate the assembly reports with the main features of the assembled puzzle (estimated time, response time, tolerance, and puzzle selected, among others). All information is sent through the MQTT broker to the agent (the MQTT inputs in Algorithm 1) running on the edge to proceed with the trust measurement and the SLA validations.

4.3. Tangram Puzzle Assembly Time Modeling

This subsection presents the process, followed by the SF, to determine the estimated time (); the initial analysis required to measure the whole time (in seconds) that is taken to move all the tangram´s pieces from its stored location in the warehouse to the final point at the assembly station (time elapsed from the first warehouse´s picking piece until the last assembly´s area placing). Additionally, it was identified that several factors affect the time measured, including (i) the position in the warehouse, (ii) the orientation of the piece, and (iii) the shape of the piece. For this reason, and as mentioned by Montgomery [47], a completely randomized design in which the effect of different factors is investigated must be performed in random order, so the environment in which the treatments are applied is as uniform as possible.

The study to investigate the effects of several factors on a continuous variable is called the analysis of variance (ANOVA), and for this case study, we specifically are using the mixed-effects analysis. The factors that are taken into account for the mixed-effects analysis include the following:

- Cases: slow (the furthest position in the warehouse), typical (the mean positions in the warehouse), and fast (the nearest position in the warehouse).

- Rotation angle: 0° and 45°.

- Shape: big triangle, medium triangle, small triangle, square, and rhomboid.

- Replication: three.

As a result, 90 scenarios (five shapes × two rotation angles × three cases × three replications) were performed; in each of the 90 scenarios, a real-time measurement of the SF to move each piece from the position in the warehouse to the assembly stations was recorded. Furthermore, the mixed-effects model (obtained using the Minitab software 21.4.0) allows us to estimate the time () that is taken to move one piece from a specific cell of the warehouse to the particular point of the assembly station, and it is described in Equation (3):

Sl represents the slow case, Fa is the fast case, and Ty is the typical case, and each case is mutually exclusive, which means that just one can be considered true at a time. On the other hand, there is a part of the equation that considers the shape (mutually exclusive), Sq represents the square shape, Rh is the rhomboid shape, and Tr represents the triangle shape. The mixed-effects model also identified a correlation between the angle (0 and 45) and the shape (Sq, Rh, Tr); for , the equation shows that both angles require different coefficients, according to the mutually exclusive combination between the variables mentioned (angle and shape). In addition, a best-fit algorithm was implemented to pick up the required piece and perform a puzzle in the shortest time, taking into account the following proposed hierarchy: (i) availability (presence or absence of a piece), (ii) priority (faster case), and (iii) sub-slot position (nearest to the warehouse origin).

4.4. Service-Level Agreement Implementation

This section explains the configuration of the SLA for the trust measurement algorithm (see Algorithm 1), implemented through a smart contract developed using the Solidity software; as previously mentioned in Section 3.4, the SLA receives and sends data from the MQTT broker and the blockchain, respectively. Furthermore, the smart contract was designed as a component that implements the SLA logic and measures trust levels; it defines structured state variables to store parameters, such as transaction success, penalties, the puzzle, and assembly validation conditions. The contract provides a minimal set of functions to store new SLA values, retrieve historical trust values, and query blockchain state information. This design ensures the execution of the SLA rules, and trust values are calculated and stored directly at the blockchain level in an immutable and traceable manner. Figure 6 summarizes how the SLA for trust measurement is embedded in the SF, showing which variables are produced via the physical process and customer interface, whose values are retrieved from the blockchain, and how the smart contract returns updated trust scores, penalties, and transaction metadata back to the factory via MQTT; it graphically presents the SLA inputs and outputs, relating the information with the SF elements and the source of the data generated. Specifically, the SF sends the MQTT SLA inputs of , , , and T; the customer interface sends the MQTT SLA input of the .

Figure 6.

Information flow for the SLA trust measurement algorithm in the SF: red arrows indicate the SLA inputs to calculate the trust score, blue arrows represent the SLA outputs generated via the smart contract, stored on the blockchain as immutable records of each assembled puzzle.

The Blockchain SLA inputs ( and ) that run on Sepolia are obtained from an interaction, specifically a consult event. On the other hand, the smart contract returns the MQTT SLA output values of , , , and a hash code to the customer interface; at the same time, the smart contract performs a transaction to store the output values of , , , , and in the blockchain that is running on Sepolia. The smart contract was programmed in Solidity, which includes six steps:

- The structure of the SLA storage contract included variables such as averageNoteTransaction (string), penalization (uint256), puzzleVerification (uint256), assembleTimeVerification (uint256), and numberTransaction (uint256).

- The public address owner that contains the mapping assembly (uint256) to store transactions by block number, lastBlockNumber (uint256 public) to store the number of the last block, last (uint256 public) to store the number builder, and owner, which is the sender of the deployment transaction.

- The function newAssembly to register a new transaction, and it can only be called by the owner.

- The function getAverageNoteTransaction to get the average value note transaction.

- The function getNumberLastBlock to get the value of the last block number.

- The function getLastBlockHash to obtain the number of the last block.

In addition, the smart contract required the definition of the caller, the private key, the contract address, the mnemonic variable, and the alchemyURL. Once the smart contract is displayed, an instance of it is created, separating into two entities, abi and address. In conjunction, an API was developed to invoke the smart contract through the RPC, the MQTT configuration, the smart contract parameters and transactions, and the callback function; see Algorithm 1 for more details. Next, the smart contract was deployed on the Sepolia test blockchain, and the Etherscan Explorer was used to visualize transactions. The deployment of the smart contract involved the definition of the Sepolia Blockchain testnet parameters and the wallet. Finally, the visualization of the deploy transaction through the Etherscan explorer was realized. Once the smart contract performs an interaction to store the output values, a new transaction is added to the blockchain; if the transaction is executed, it must be signed with the private key, and the Tx-receipt sends a notification that the transaction was made correctly. Based on this implementation and deployment, the following section presents the experimental results obtained from applying the proposed SLA algorithm for trust measurement, including the evaluation of time estimation accuracy and the behavior of the SLA conditions during the smart factory assembly process.

5. Results

This section presents the experimental results obtained from implementing the SLA deployed in the blockchain to measure trust in the SF. The first part presents the results of calculating the estimated time () for assembly in a Python 3.7 function to determine the error between this variable and the measured time in the assembly puzzles in order to configure the SLA parameters. The second part presents the results of the implementation of the SLA for trust measurement, including the main cases of the conditional verification tested in the SF.

5.1. Mixed-Model Effect Implementation

In particular, Equation (3) was programmed within a Python script. It was evaluated with input vectors that included sequences of the assembled tangram puzzles (location within the warehouse or case, shape and size, and angle storage), so the prediction of was validated. The rocket puzzle was selected as a puzzle under study due to its presenting a rectangular area where both assembly stations can collaborate, becoming the case with a higher area to cover. Specifically, Table 2 presents a comparison between the values estimated by the SF for , according to Equation (3), and the real-time measurements (the time it took the factory to move each piece from the warehouse to the assembly stations) for the Rocket puzzle. The table also includes information about the figure (piece shape and size), case (location within the warehouse), and the angle at which the piece was stored. The last two columns filled the total time for the estimated (683.22 s) and (682.57 s) measured time. According to the comparison for both , the estimated value achieved presents a 99.90% accuracy for Rocket.

Table 2.

Comparison between the estimated assembly time calculated via the SF using the mixed-effects model and the measured assembly time required to move each rocket puzzle piece from its warehouse location to the assembly stations.

To analyze how the warehouse location and the storage angle affect the time to move a piece, Table 3 reports three representative corner scenarios (fast, typical, and slow) selected from the 90 experimental cases of the mixed-effects model. All the pieces from the tangram puzzle were tested in all the positions in the warehouse. The warehouse matrix consists of an x-axis with four slots and a y-axis with two slots; each intersection slot has three sub-slots (z-axis). The total number of sub-slots is 24, the maximum storage capacity of Tamgram pieces.

Table 3.

Representative fast, typical, and slow warehouse corners used to verify the mixed effects model prediction of the estimated time as a function of warehouse location (x, y, z) and storage angle.

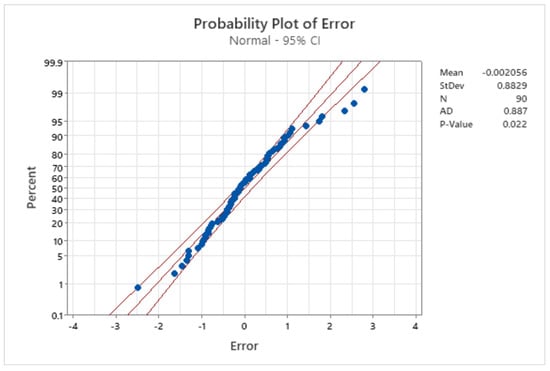

As observed, the fastest time was achieved with the following features: a piece stored at 0 degrees in a warehouse cell (x = 1, y = 2, z = 1) near the distribution station, taking a time of 72.82 s. On the other hand, the typical time was achieved with the following features: a piece stored at 45 degrees in an intermediate warehouse cell (x = 2, y = 1, z = 1), taking a time of 93.48 s. The slowest time was achieved with the following features: a piece stored at 0 degrees in a warehouse cell (x = 4, y = 2, z = 2) far from the distribution station, taking a time of 105.01 s. Finally, the last column represents the error between the estimated and the measured time in seconds and percentages. To validate the suitability of the mixed-effects model for SLA configuration, the prediction errors between the estimated assembly time () and the measured time () were analyzed across the 90 experimental scenarios, and their distribution was evaluated using a normal probability plot with 95% confidence, shown in Figure 7; the p-value obtained is 0.022, and it is smaller than 0.05, indicating that the mixed effect model for the estimated time () is adequate to be implemented within the SLA for the Trust measurement. Additionally, the point values are within the limits of the normal distribution, following a positive correlation of the data.

Figure 7.

Normal probability plot of the prediction error (estimated time–measured time) for the 90 tangram scenarios used to calibrate the mixed effects time model; the approximately linear trend of points within the confidence bounds, together with a mean error of 0.002056 s, a standard deviation of 0.8829 s, and a p-value of 0.022, indicates that the residuals are compatible with a normal distribution and that the mixed-effects model is adequate for the estimated time within the SLA for Trust measurement.

5.2. SLA for Trust Measurement Evaluation

This section presents the results of the SLA for trust measurement implementation; here, the different conditional verifications (see step 4 of Algorithm 1) are tested according to the values of puzzle verification () and assembly time verification (). The four cases tested include the following:

- The measured time () is less than the estimated time (), and the selected and assembled puzzles are the same.

- The measured time () is greater than the estimated () time but less than the tolerance time (), and the selected and assembled puzzles are the same.

- The measured time () is less than the estimated time (), but the selected puzzle is different than the assembled puzzle

- The measured time () is greater than the tolerance time (), and the selected and assembled puzzles are the same.

To evaluate how different combinations of assembly time and puzzle correctness affect penalties and trust updates, Table 4 summarizes the four SLA verification cases tested in the smart factory and also the conditional verification calculated through the SLA, obtaining as a result the values of the actual transaction () and the penalty () for each case. Hence, the puzzle selected to test the SLA for the trust measurement algorithm was the rocket (worst-case due to the higher area to cover) because it presents a rectangular area where both assembly stations can collaborate.

Table 4.

Conditional verification of the SLA-based trust measurement for four representative rocket-puzzle scenarios, illustrating how the SLA rules are applied within the SF.

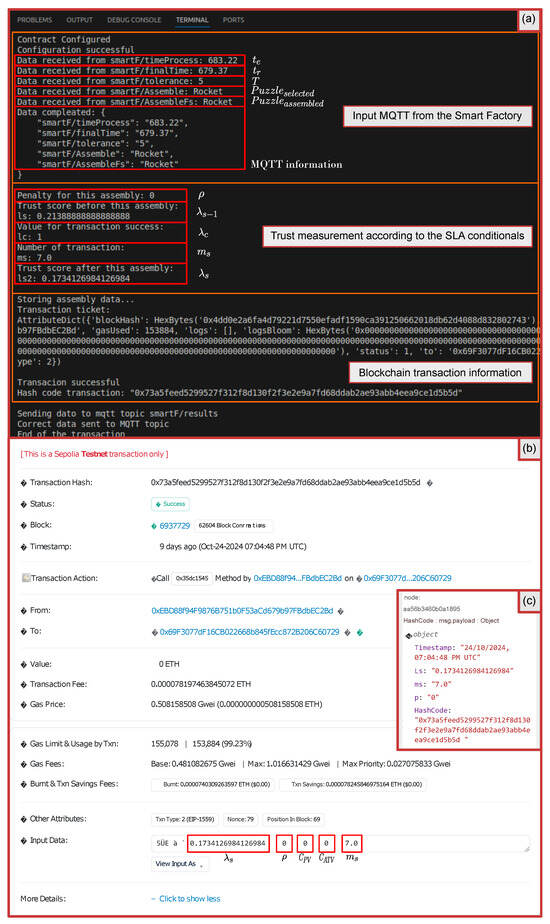

To illustrate how the SLA-based Trust algorithm behaves when the factory delivers the correct puzzle faster than the estimated time and incurs no penalty, Figure 8 shows the full transaction flow for Case 1. In fact, Figure 8a demonstrates the SLA for Trust Measurement implemented for the first case, obtaining the MQTT inputs coming from the SF, including the estimated time (, with topic: SmartF/timeProcess), the measured time (, with topic: SmartF/finalTime), the tolerance (T, with topic: SmartF/tolerance), the puzzle selected (, with topic: SmartF/Assemble), and the puzzle assembled (, with topic: SmartF/AssembleFs). The Case 1 logs contain information about the input values sent via the SF, including = 683.22 s, = 679.37 s, tolerance = 5%, = Rocket, and = Rocket. The penalty for the assembly ( = 0), the trust score before the assembly ( = 0.2138), the value of the actual transaction ( = 1), the number of transactions ( = 7), and the trust score after the assembly ( = 0.1734). and were fixed at 0.1734 and 7 to demonstrate the trust variation for the four cases. If a trust () value close to 1 were chosen and a high value for the number of transactions , the reduction in trust by several orders of magnitude would not be reflected, as it is presented in the results. To illustrate how the SLA inputs propagate through the trust algorithm, Table 5 details, for each of the four rocket cases, the SF inputs, penalties, transactions, and updated trust scores.

Figure 8.

Transaction information for Case 1, where the measured time is less than the estimated time, and the assembled and selected puzzles are the same. The figure presents (a) the terminal logs for the input MQTT parameters, the trust calculation, and the Blockchain transaction information; (b) the Sepholia Transaction Hash (0x73a5feed5299527f312f8d130f2f3e2e9a7fd68ddab2ae93abb4eea9ce1d5b5d) allows for finding the returned blockchain values from the SLA algorithm (step 7); (c) the returned MQTT values from the SLA algorithm (step 6).

Table 5.

Important input values (, , tolerance, , and ) for the SLA for trust measurement, and calculations performed via the SLA (, , , , ).

Once the information is stored in the blockchain, the transaction ticket is returned (blockchain values), including information such as the blockHash (HexBytes), blockNumber (6937729), cumulativeGasUsed (18227673), effectiveGasPrice (508158508), gasUsed (153884), and the hash code transaction (see Figure 8b). In the same way, the information of the case 1 transaction is displayed in Sepholia Testnet Etherscan, including the timestamp, the transaction action, transaction fee (0.000078197463845072 ETH), the gas price (0.508158508 Gwei), and the input data (see Figure 8b). Additionally, the returned MQTT values are presented in Figure 8c, including values such as the timestamp (24 October 2024, 07:04:48 PM UTC), (0.1734126984126984), (7.0), (0), and the hashcode. Appendix A shows the figures (see Figure A1, Figure A2, and Figure A3) for the other cases related to terminal logs that returned Blockchain values and MQTT, in the same way that was explained above for case one. All the information about the four cases related to the input values and the calculation of trust () performed via the SLA are summarized in Table 5. Remarkably, case one corresponded to the SF delivering the puzzle in time and was correctly assembled ( = 0.1734), case two corresponds that the puzzle was completed within tolerance time ( = 0.0649), case three corresponds that the SF delivering the puzzle in time and was incorrectly assembled ( = 0.0005), and case four corresponds that the puzzle was completed outside tolerance time and was correctly assembled ( = 4.91 × ). The trust () decreases because the cases (except case one) presented penalization for tolerance ( = 0.05), exceeded time ( = 1), or fault in the assembly ( = 1).

To complement the SLA and trust results, Table 6 compiles the main on-chain metrics returned via the Sepolia testnet after registering each SLA transaction, showing how gas usage, gas price, and transaction fees vary across the four rocket cases. Indeed, it was verified that the value of gasUsed is the same for all the transactions because, in each of the transactions, the same number of values is being used for storage within the blockchain. Additionally, it is observed that, for each case, the parameters within the Sepolia Testnet transaction vary, for example, the blockNumber, the cumulativeGasUsed, effectiveGasPrice, transaction fee, and the gas price; all of this information is also presented in Figure 8b but summarized in Table 6. Finally, it can be stated that the validation of the SLA for trust measurement was performed correctly due to the calculation of within the four cases presented in this section, which were performed according to the algorithm proposed for the case study of the SF, taking into account the input values coming from the factory (MQTT), and the previous values of the SLA calculations (blockchain).

Table 6.

Relevant values returned after the SLA for trust measurement are calculated, presented in Etherscan (Sepholia Blockchain testnet), after the transaction is registered.

While these results demonstrate the technical feasibility and correctness of the proposed SLA-based trust model, their broader implications, limitations, and relevance in comparison with existing approaches require further interpretation.

6. Discussion

This section interprets the implications of the proposed SLA-based trust model by analyzing the experimental findings within the context of SF and the challenges identified in the literature. Prior research highlights that, although Industry 4.0 technologies have been widely studied, trend technologies such as the blockchain have not yet been fully integrated into SF architectures. The use of the blockchain in application fields, such as the manufacturing sector, remains unclear and has not yet been justified. To clarify the concept employed in this work, we define trust in an SF as a set of individual measurements (availability, response time, and successful transactions) related to the process rewards or penalization within the factory to estimate a level of trust between the customer and the factory to produce a good. Building on this definition, it is important to emphasize that the blockchain attributes intrinsically promote trust between stakeholders but do not necessarily measure trust.

The proposed SLA applied to the SF was built as a set of rules via an algorithm embedded in edge and cloud computing, incorporating terms and conditions negotiated between the customer and the factory. From an operational management perspective, the proposed research defines trust as a mechanism that must be improved and measured, rather than a qualitative attribute. Building on previous research on SLA-based governance in distributed and automated systems, the use of SLAs enables the formalization of performance expectations and compliance verification. By integrating SLA logic into blockchain-based smart contracts, the proposed approach extends these principles to an SF environment, where trust can be continuously evaluated based on observed production events, rather than subjective assessments. The technical design choices adopted in this work are grounded in automation and the Industry 4.0 literature, which emphasizes decentralized control, traceability, and real-time monitoring across heterogeneous systems. Unlike traditional cloud-based trust models or purely conceptual trust models, the proposed framework combines SF components and blockchain technology to capture physical process data and enforce SLA conditions at runtime.

These concepts were experimentally validated in our tangram assembly case study, which included the assembly process of a tangram puzzle through different stations. Four cases encompass all the SLA algorithm conditions to test the proposed system. As was observed, the mixed-effect model used to estimate the assembly time achieved 99.9% accuracy for the rocket case; it proved adequate for estimating the time () the SF took to assemble the puzzle. The potential errors in calculating the mixed-effects model include: false positive and false negative results caused by incorrect computer vision shape detection, a lack of data, and no independence in the data provided to the model. A notable limitation is the factory layout, and if it were reconfigured, it would require recalibration of the mixed-effects model because the model should be custom-made, according to the features of the process studied. The results of the four cases stipulated in the SLA indicated that the calculation of all the parameters (, , , and ) allowed the trust measurement (), in concordance with the proposed SLA algorithm. Concerning the scalability perspective, deploying the proposed smart contract in a production SF would require practical architectural adjustments, rather than a fundamental redesign. To achieve maximum performance, the contract should be migrated from public test networks to a restricted blockchain environment. To ensure maximum security and transparency on the blockchain, it is required to avoid excessive on-chain storage and gas consumption; non-critical operational data should remain in traditional databases, while the smart contract stores only essential trust variables and cryptographic references.

Although the Sepolia testnet served for initial validation, implementing a blockchain solution in a standalone SF presents several practical challenges. SF environments typically require private or permissioned blockchains to ensure confidentiality, low latency, and the integration of appropriate industrial security policies. In some cases, this limitation steams from computational and storage resources, consensus mechanisms, and the efficient execution of smart contracts. Furthermore, network reliability and scalability must be addressed, as factories may face intermittent connectivity or real-time processing requirements. Robust security and protection against both internal and external threats are also critical for practical implementation in real-world industrial environments. Based on these observations, the following section summarizes the main findings of this study, highlights the contributions, discusses its limitations, and outlines directions for future research.

7. Conclusions

Based on the reviewed state of the art, the proposed blockchain-based system for measuring trust in a frugal SF assembly process addresses an identified gap in the integration of blockchain technologies within SF environments. This work has introduced an operational and validated approach to trust measurement, moving beyond conceptual and cloud-oriented models. In addition, the proposed solution establishes a novel integration within an SF architecture composed of seven key elements: cyber-physical systems, edge computing, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, data analytics, cybersecurity, and the blockchain.

To configure the SLA, a mixed-effects model was proposed, implemented through a Python script, and evaluated with 90 input vectors, identifying that the model was adequate to predict the estimated time () within the SLA for trust measurement. Implementing the SLA confirms that a blockchain can be applied in an SF in different fields, not just logistics or traceability, opening new applications and solving some challenges in the manufacturing sector. As a synthesis, the main contributions of this research included a functional interpretation of trust as an SLA metric based on production conditions, the implementation of a smart contract to establish SLA conditions, compute trust, and record results on-chain, and an experimental validation in an open-source frugal SF process. It demonstrates the feasibility, accuracy of time estimation (mixed-effects model), and traceability of trust updates. Few studies have investigated trust measurement through SLAs embedded in a blockchain; although these studies present a trust mechanism based on SLA implementation via smart contracts, their scope remains largely conceptual or is limited to the cloud. As a result, the proposed approach offers a more robust and realistic trust evaluation, representing one of the first practical implementations of an SLA trust model in an SF environment.

This study involved diverse limitations, such as the use of a defined number of spaces in the warehouse (24 spaces), a defined orientation of the pieces within the warehouse, and the fact that the algorithm for trust measurement only requires a specific number of inputs and gives a certain number of outputs. Furthermore, the public blockchain network used for testing does not provide the latency and access control associated with real-world applications. Future work will focus on a study that proposes and tests different models to predict the estimated time, testing the proposed system in an industrial environment, integrating new technological trends into the SF architecture, or using a Dynamic SLA for automation orchestration. Moreover, the scalability of the SLA for trust measurement in a real SF is still under research, due to the application of all the elements of the architecture required to be developed in a real factory, and as a complex scenario, it required more variables to study. Finally, although the research did not include the analysis of operational or transaction latencies, due to the blockchain used in the case study having been the Sepolia testnet, both concepts will be taken into consideration as a promising direction for future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.F.-D. and F.C.-S.; Methodology, J.A.F.-D., J.C.-H. and F.C.-S.; Software, J.A.F.-D., L.A.C.-M., J.C.-H. and J.D.M.-S.; Validation, J.A.F.-D., J.C.-H. and J.D.M.-S.; Formal analysis, L.A.C.-M.; Investigation, J.A.F.-D., J.C.-H. and J.D.M.-S.; Resources, L.A.C.-M. and F.C.-S.; Data curation, J.A.F.-D. and J.D.M.-S.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.A.F.-D., L.A.C.-M., J.C.-H. and J.D.M.-S.; Writing—review and editing, J.A.F.-D., L.A.C.-M. and F.C.-S.; Visualization, J.D.M.-S.; Supervision, J.A.F.-D. and F.C.-S.; Project administration, F.C.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONACHYT grant number 655053. The APC was funded by Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

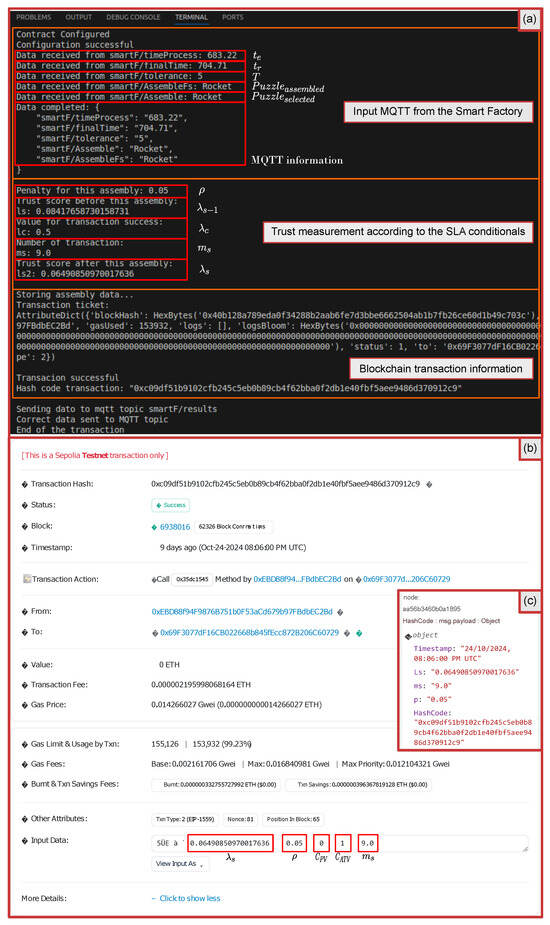

Figure A1.

Transaction information for Case 2, where the measured time is between the estimated time and the tolerance time, and the assembled and selected puzzles are the same. The figure presents (a) the terminal logs for the input MQTT parameters, the trust calculation, and the blockchain transaction information; (b) the Sepholia Transaction Hash (0xc09df51b9102cfb245c5eb0b89cb4f62bba0f2db1e40fbf5aee9486d370912c9) allows for finding the returned Blockchain values from the SLA algorithm (step 7); (c) the returned MQTT values from the SLA algorithm (step 6).

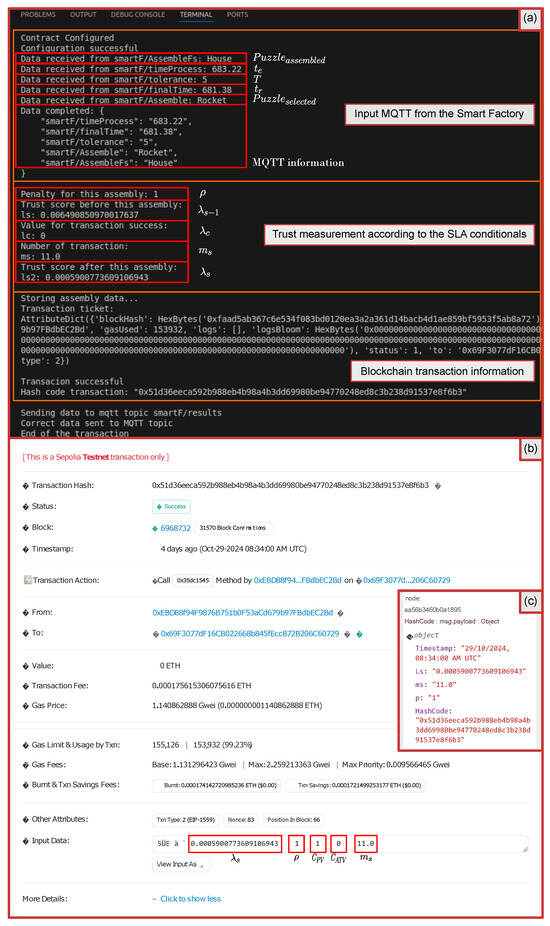

Figure A2.

Transaction information for Case 3, where the measured time is less than the estimated time, but the assembled and selected puzzles are different. The figure presents (a) the terminal logs for the input MQTT parameters, the trust calculation, and the blockchain transaction information; (b) the Sepholia Transaction Hash (0x51d36eeca592b988eb4b98a4b3dd69980be94770248ed8c3b238d91537e8f6b3) allows for finding the returned blockchain values from the SLA algorithm (step 7); (c) the returned MQTT values from the SLA algorithm (step 6).

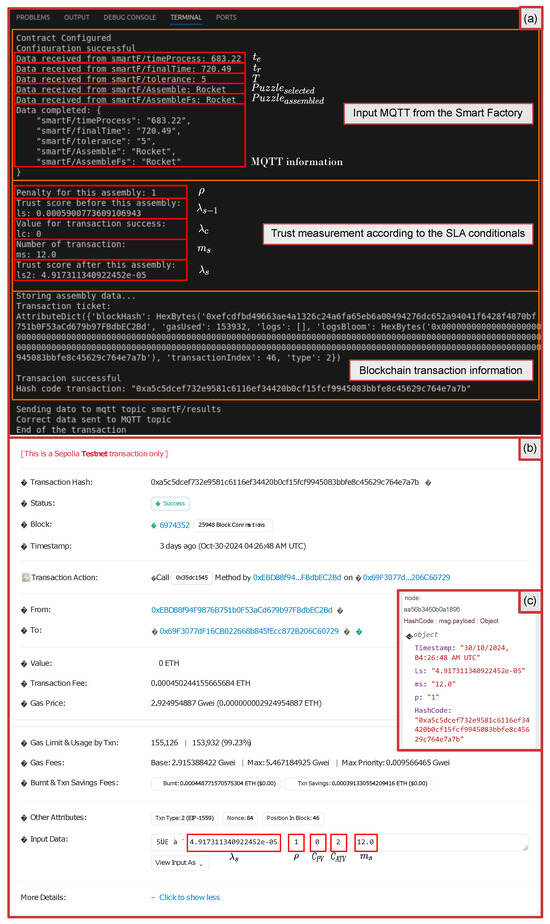

Figure A3.

Transaction information for Case 4, where the measured time is greater than the tolerance time, and the assembled and selected puzzles are the same. The figure presents (a) the terminal logs for the input MQTT parameters, the trust calculation, and the blockchain transaction information; (b) the Sepholia Transaction Hash (0xa5c5dcef732e9581c6116ef34420b0cf15fcf9945083bbfe8c45629c764e7a7b) allows for finding the returned blockchain values from the SLA algorithm (step 7); (c) the returned MQTT values from the SLA algorithm (step 6).

References

- Kamble, S.S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Gawankar, S.A. Sustainable Industry 4.0 framework: A systematic literature review identifying current trends and future perspectives. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Dave, P.; Hanchate, A.; Sagapuram, D.; Natarajan, G.; Bukkapatnam, S.T.S. Implementing an open-source sensor data ingestion, fusion, and analysis capability for smart manufacturing. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 33, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, F.D.; Mamede, H.S. Digital transformation for SMEs in the retail industry. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.; Amorim, M.; Melão, N.; Cohen, Y.; Rodrigues, M. Digitalization: A literature review and research agenda. Lect. Notes Multidiscip. Ind. Eng. 2020, 201, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhi, E.; Huet, J.-C.; Fortineau, V.; Lamouri, S. A methodology for cloud manufacturing architecture in the context of Industry 4.0. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2020, 68, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaloopour, L.; Su, Y.; Raskob, F.; Meuser, T.; Chakraborty, P.; Kreutzer, M.; Hollick, M.; Strufe, T.; Franchi, N.; Jamali, V. Resilience-by-design in 6G networks: Literature review and novel enabling concepts. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155666–155695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, R. From 5G-Advanced to 6G in 2030: New services, 3GPP advances, and enabling technologies. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 63238–63270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, T.; Peddi, A.V.; Ponaganti, S.; Veeramalla, S.T. A Survey on Various Security Protocols of Edge Computing. J. Supercomput. 2024, 81, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, B.; Chaudhary, S.; Panwar, R. Intelligent resource allocation and optimization for industrial robotics using AI and blockchain. In Intelligent Resource Allocation and Optimization for Industrial Robotics Using AI and Blockchain; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 82–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Huo, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.Z.; Ng, K.K. Design of a smart manufacturing system with the application of multi-access edge computing and blockchain technology. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 28659–28667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayana, K.; Kulkarni, P.M.; Dandannavar, P.S.; Tigadi, B.S.; Gokhale, P.; Naik, S. Blockchain technology for manufacturing sector. EAI Endorsed Trans. Internet Things 2024, 10, e7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Azamfar, M.; Singh, J. A blockchain-enabled cyber-physical system architecture for Industry 4.0 manufacturing systems. Manuf. Lett. 2019, 20, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, V.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, B.; Chaudhary, S.; Panwar, R. Security and privacy challenges in blockchain-based supply chain management: A comprehensive analysis. In Achieving Secure and Transparent Supply Chains with Blockchain Technology; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; p. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, N.; Corn, M.; Škulj, G.; Diaci, J.; Podržaj, P. Scalability solutions in blockchain-supported manufacturing: A survey. Stroj. Vestn./J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 68, 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]