Abstract

The design-related behaviour of structural dynamics for electric-assisted bicycle (e-bike) drive units significantly influences the mechanical system—e.g., vibrations and durability, stresses and loads, or functionality and comfort. Identifying the underlying mechanical principles opens up optimisation possibilities, such as improved e-bike design and user experience. Despite its potential to enhance the system, the structural dynamics of the drive unit have received little research attention to date. To improve the current situation, this paper uses a flexible multibody modelling approach, enabling new insights through virtual trials and analyses that are not feasible solely from measurements. The incorporation of the drive unit’s system-level topology regarding mass, moment of inertia, stiffness, and damping enables the analysis of critical system states. Experiments accompany the analysis and validate the model by demonstrating a load-dependent shift of the first torsional mode around 35 Hz to 60 Hz, capturing comparable resonance frequency ranges up to 6 kHz, and yielding qualitatively consistent peak positions in both steady-state and ramp-up analyses (mean deviations of 0.03% and 0.06%, respectively). Theoretical considerations of the multibody system highlight the effects, and the stated modelling restrictions make the method’s limitations transparent. The key findings are that the drive unit’s structural dynamic behaviour exhibits solely one structural mode until 0.5 kHz, and further 27 modes up to 10 kHz, solely originating due to the multibody arrangement of the drivetrain. These modes are also load-dependent and lead to resonances during operation. In summary, the approach enables engineers, for the first time, to significantly improve the structural dynamics of the e-bike drive unit using a full-scale system model.

1. Introduction

By 2025, the e-bike drive is an indispensable and well-established means of transportation, evident by a 53% share of bicycle sales in Germany in the previous year [1] and globally increasing market trends [2]. Current peak variants are able to produce a torque of at least 100 at 750 with an increasing trend [3,4]. The e-bike drive unit consists of a highly integrated design, including the electric motor, the gear stages, any freewheels, the sensors, and the electronics. Its housing is directly located within the bicycle frame, which leads to a direct transmission of any forces or motions from the drive unit. As a consequence, the structural dynamics of the drive unit have a decisive influence on the entire bicycle system in terms of vibration and durability, stresses and loads, and functionality and comfort. For instance, any excitation originating from the drive unit is transmitted through the transfer path of the frame and perceived by the rider in the form of noise, vibrations, or harshness [5], e.g., influencing the ride comfort. Similarly, a freewheel may alter the system behaviour [6] such that the mechanical functionality may be influenced or vibrations arise with all its consequences.

High-fidelity system simulations that consider structural dynamics are state of the art in the automotive sector [7,8], but there is a lack of methods and tools in the bicycle industry. For example, the testing procedures of current norms and regulations are solely based on measurement techniques [9,10,11].

Currently, no validated and robust system model exists that represents these structural dynamics for the e-bike drive unit—to the best of our knowledge. Current knowledge in this field is predominantly based on personal experience and measurement techniques. As a consequence, the internal mechanisms and structural dynamics of the e-bike drive unit system remain insufficiently investigated. Either complex interactions are not known, or analyses are not feasible solely by measurements. As a result, the manufactures face challenges for determining comfort-related topics such as noise, vibration, and harshness, for predicting the component durability related to dynamic stresses and loads, and for evaluating requests related to innovative designs and functionalities. A computer-assisted simulation analysis of the entire system allows us to gain these insights or—at least—to significantly contribute to them.

Moreover, developing a system model and applying a highly-fidelity system simulation enable virtual prototyping, which facilitates system analysis and accelerates product development [12,13]. For instance, a design concept can be tested virtually, the influence of a single component or parameter can be identified, and the primary interactions determined based on sensitivities. Flexible multibody simulation represents a key methodology for analysing the system-level dynamic behaviour. Next to analysing the dynamic behaviour of automotive applications [7,8], it can be used to identify the system-level response under electromagnetic excitation [14] , to assess critical and undesired component mode shapes [15], or to enable structural design optimisation [16] (to mention a few).

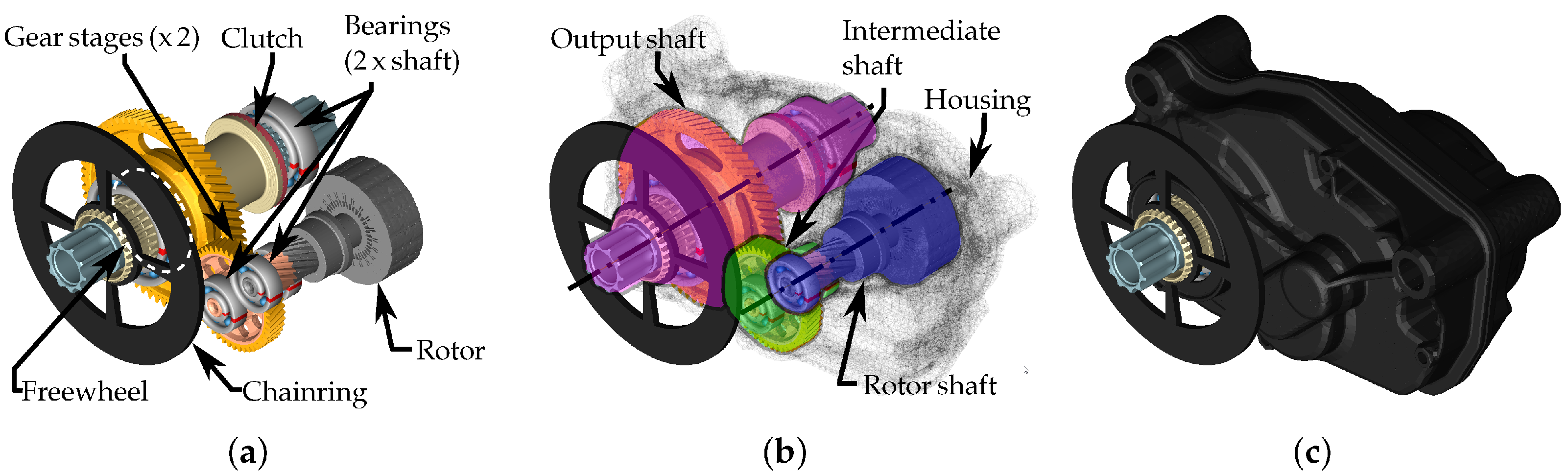

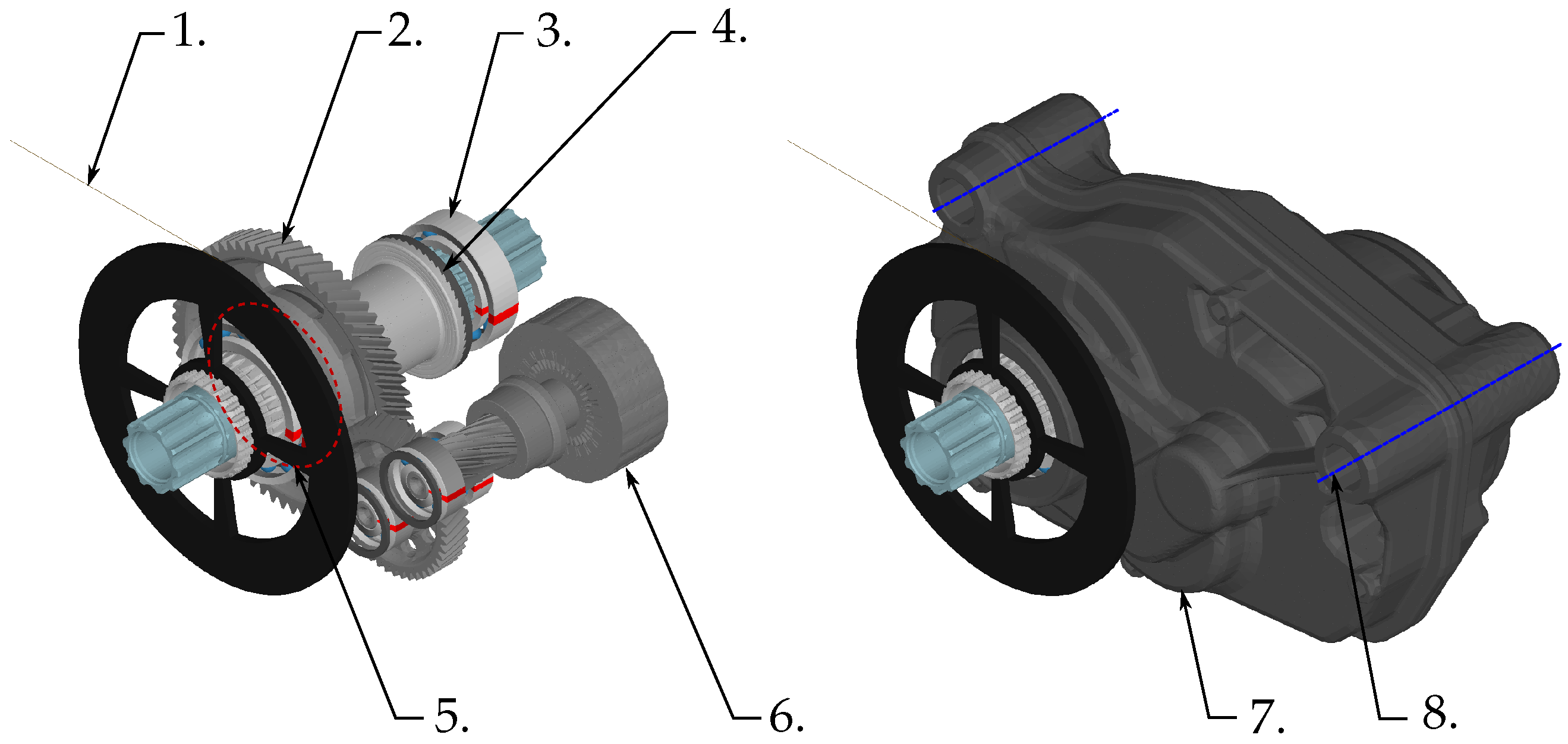

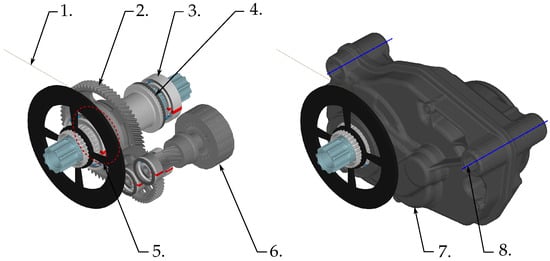

For clarity, Figure 1 introduces the referenced e-bike drive unit system, which is developed as a simulation model in this work.

Figure 1.

Holistic e-bike drive unit as a flexible multibody dynamic model. (a) Visible rotational components of the drivetrain. (b) Subsystem declarations of the assembly indicated by different colours. (c) Illustration of the total system.

The scope of this paper is to present a comprehensive system-level model of the e-bike drive unit based on flexible multibody dynamic simulation (as indicated in Figure 1) and to report novel results regarding its structural dynamic behaviour. The methodology and results are based upon previous work, which deals with the general methodology [5], the freewheel mechanics [6], and the validation procedure [17]. In this paper, these aspects are integrated and further developed, allowing us to complement the modelling and gain new insights into the structural dynamics of e-bike drive units.

2. Materials and Methods

This work relies on the methodology presented in previous studies, which is based on a flexible multibody dynamics (MBD) approach [5]. It is augmented by the latest modelling and numerical considerations, the revealed topology, and the verification and validation related to the e-bike drive unit.

2.1. Theory of Flexible Multibody Dynamics

From a methodological point of view, flexible MBD modelling enables a suitable balance between high-fidelity model resolution and reduced computational effort. This balance is necessary, since the consideration of transient dynamics entails a large number of equations and limited parallelisation opportunities, so that computational operations must be reduced to achieve efficient calculation. This is accomplished in a preprocessing step based on the finite element method (FEM), in which the inherent structural flexibility of a component is transformed into a modal reduced representation using component mode synthesis (CMS), in particular, according to Craig–Bampton with subsequent orthonormalisation. Thereby, the associated reduction in degrees of freedom consequently reduces the number of arithmetic operations to be performed. The exchange medium from FEM to MBD is called the modal neutral file (MNF) and provides reduced modal data for the flexible body in a unit-consistent form.

Based on the floating frame of reference formulation (FFRF), the representation in the MBD is a superposition of the rigid motion and the relative (small) deformation resulting in the actual position using global coordinates

where is the rigid translation, the undeformed body-referred position, and the rotation matrix in the inertial system. To efficiently calculate the elastic deformation and approximate a solution, the approach of the product method is applied. It allows us to separate the relative deformation into location-dependent () and time-dependent () components [18], resulting in

where denotes the i-th mode-shape vector. This decomposition constitutes a Rayleigh–Ritz approximation to reduce the number of degrees of freedom N while retaining an accurate description of the dynamic behaviour [19]. The Craig–Bampton method is then used to obtain the location-dependent components. It partitions the basis as , with the generalised coordinates [19]. Here, contains the constraint (static) modes associated with the physical interface degrees of freedom , while contains the fixed-interface normal modes with modal coordinates . Equation (2) inserted in (1) results in the following representation of with additional first and second derivatives [20]

This allows us to consider a flexible representation for a single body. To scale the formula to a namely multibody system, the generalised coordinates are used and also separated into the rigid and flexible components [21]

with, e.g., the rigid component of position and rotation angle and the change in shape represented through the modal coordinates . The equation of motion containing several coupled substructures, such as flexible bodies, can be written in the following format [22]

where the generalised representation contains the external excitation forces, the Coriolis, centrifugal forces, and the constraint forces [22]. Considering a flexible structure and using the FFRF formulation with the partition from Equation (6), Equation (7) turns into the following block representation, which is derived from [21]

where and are derived by the Craig–Bampton (CB) method. In contrast, rigid bodies do not contain any body-related elastic degrees of freedom. Therefore, no stiffness or damping is associated with them. The system’s ability to vibrate additionally results from the nature of the coupling between the bodies. Considering a joint connection e modelled by a bushing, the constraint forces are calculated by additional stiffness and damping terms on the principle of virtual work in accordance with [23], yielding

where the delta implies the relative displacement between the two bodies, exemplarily named a and b, with . The stiffness and damping terms are transferred by to the reference system through . The Jacobian elements related to the rigid and flexible components of the point motion from Equation (1) are [23]

This provides the relative representation between the two locations i and j on the connected parts by

Augmenting Equation (8) by (9) and (11) and resorting enables the subdivided representation of rigid, flexible, and mixed terms

Neglecting the damping and remaining forces allows us to transform it into the formula of an eigenvalue problem such that

Building the Schur complement of Equation (13) according to [24] by solving for through substituting of the second row in the first row

provides

It represents the influence of the flexible shares on the stiffness and mass matrices related to the rigid component . At very low frequencies, the inherent flexible term of the structure () contributes to a static flexibility, which impacts the rigid behaviour, since

Thereby, the effective stiffness solely relates to the stiffness components.

In contrast, for very high frequencies, the inertia associated with the flexible deflections can no longer follow the motion and acts as pure rigid mass inertia, since

In this case, the effective stiffness is determined solely by the mass components.

2.2. Topology and Modelling

The methodology from our previous work—reported in [5]—applies a flexible MBD approach to predict the structural dynamic behaviour of the e-bike drive unit. The yielding topology and modelling assumptions are presented in the following.

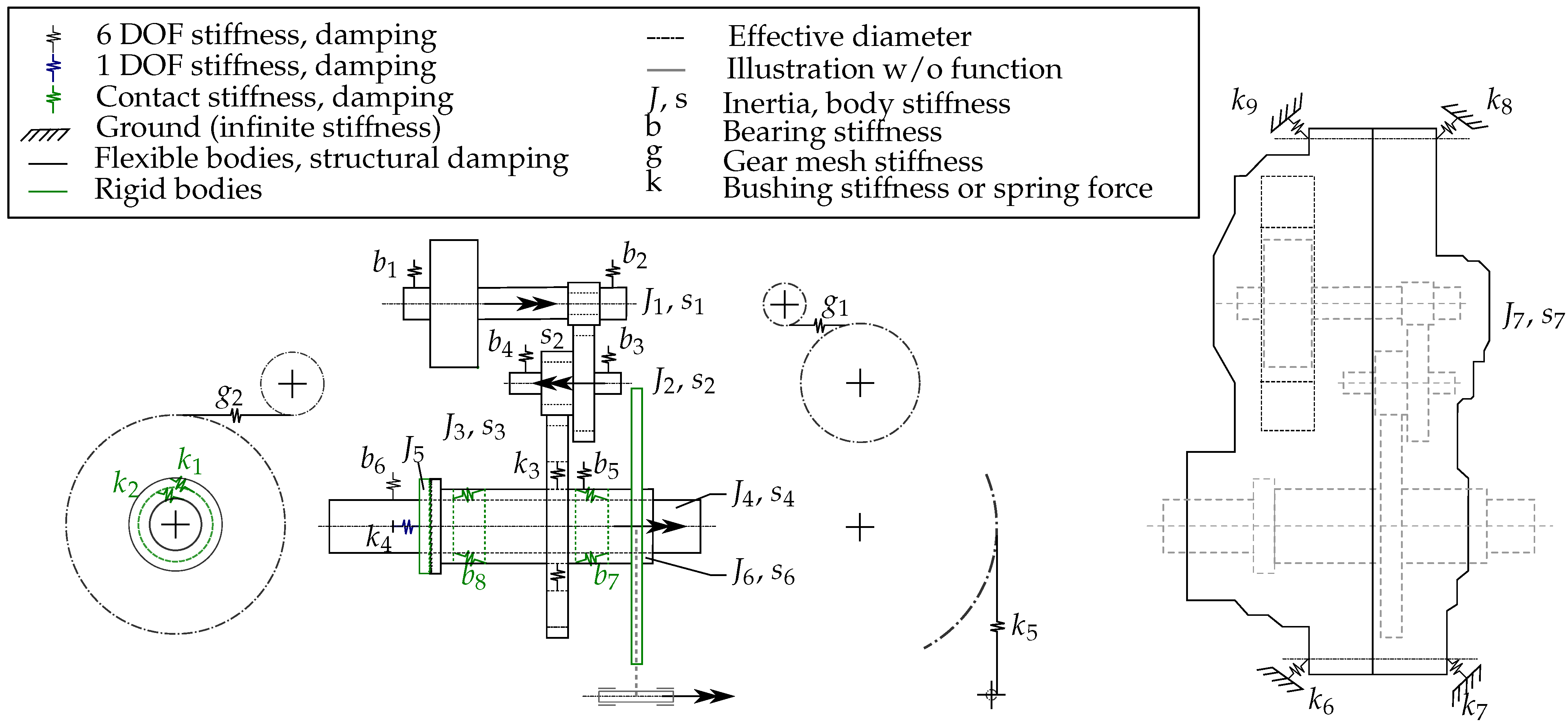

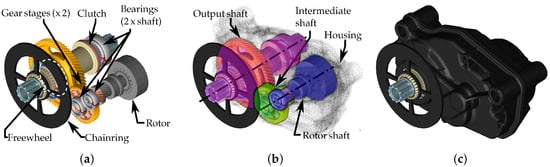

The topology of the holistic model captures all interactions that are not explicitly represented in the graphical user interface from the model assembly (compare Figure 1). It reveals the considered components, the applied simplifications, and the defined boundaries of the system (see Figure 2). The illustrated shapes and locations are derived from the applied e-bike drive unit. The integrated legend explains the symbols, line styles, and employed parameters.

Figure 2.

Topology of the holistic multibody dynamic model revealing the interactions of shafts, bearings, gears, freewheels, and housing.

The individual bodies predominantly contribute mass and mass moment of inertia to the system (J), while the bearings, gear meshing, motor freewheel, rider freewheel (clutch), slide bearings, and bicycle chain additionally provide stiffness () and damping between the bodies. The damping is associated with the stiffness and is therefore not represented separately. This total arrangement enables rigid-body modes at the system level. Additionally, the elasticity of flexibly implemented bodies superimposes with their rigid motions, introducing a stiffness (s) and minor damping to the entire system. The structural damping is less than 1% of the critical damping for steel or aluminium [25] and is therefore generally adjusted. Regardless, if a flexible body mode is excited, its structural flexibility has an influence on the interaction in the system, as evident by the coupling term from Equation (14). Given both relatively thin material and high torque, the structural flexibility must be considered in the model. For very low frequencies, its static stiffness dominates the effective system stiffness (see Equation (15)), and for very high frequencies, its mass moment of inertia dominates (see Equation (16)). In conjunction with the other given stiffnesses that connect the individual rigid and flexible bodies (), system resonances or anti-resonances occur when the determinant of Equation (13) equals zero or, respectively, the transfer function produces poles under forced excitation [26]. Therefore, it is relevant to consider each stiffness influence in the system, which is of a similar dimension to the one of the structural flexibility.

The applied boundary conditions are the housing assembly fixation to the ground and the dynamic constraint on which the chain stiffness is linked. Additionally, a given electric motor force is applied, or torque, respectively. The dynamic constraint allows us to either predetermine an angular acceleration or to apply a resistance torque, which requires us to specify a resistance mass moment of inertia. Defining a specific angular acceleration prevents the rotational motion from oscillating. This is considered legitimate for the brake or system applied after the bicycle chain because the mass moment of inertia relative to the drive is relatively high.

Table 1 summarises the approaches for parameter acquisition with respect to the topology and the subsequent modelling procedure.

Table 1.

Parameter acquisition for the modelling process.

The approach employing Bearing AT (i) and Gear AT (ii) is based on the geometric data, material density, and Young’s modulus. From these parameters, a Nastran routine is generated, which determines the resulting elastic properties in a finite element (FE) preprocessing step. The obtained elasticity information is subsequently transferred into a surrogate model, where it is represented as surrogate stiffness during the flexible MBD simulation dependent on the location determination at the current time step.

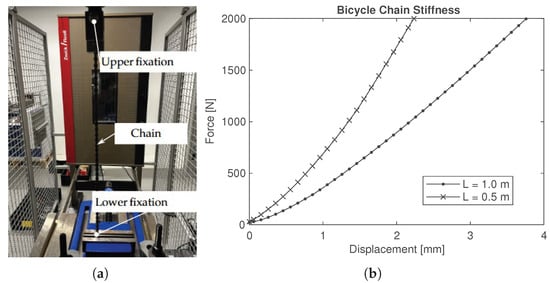

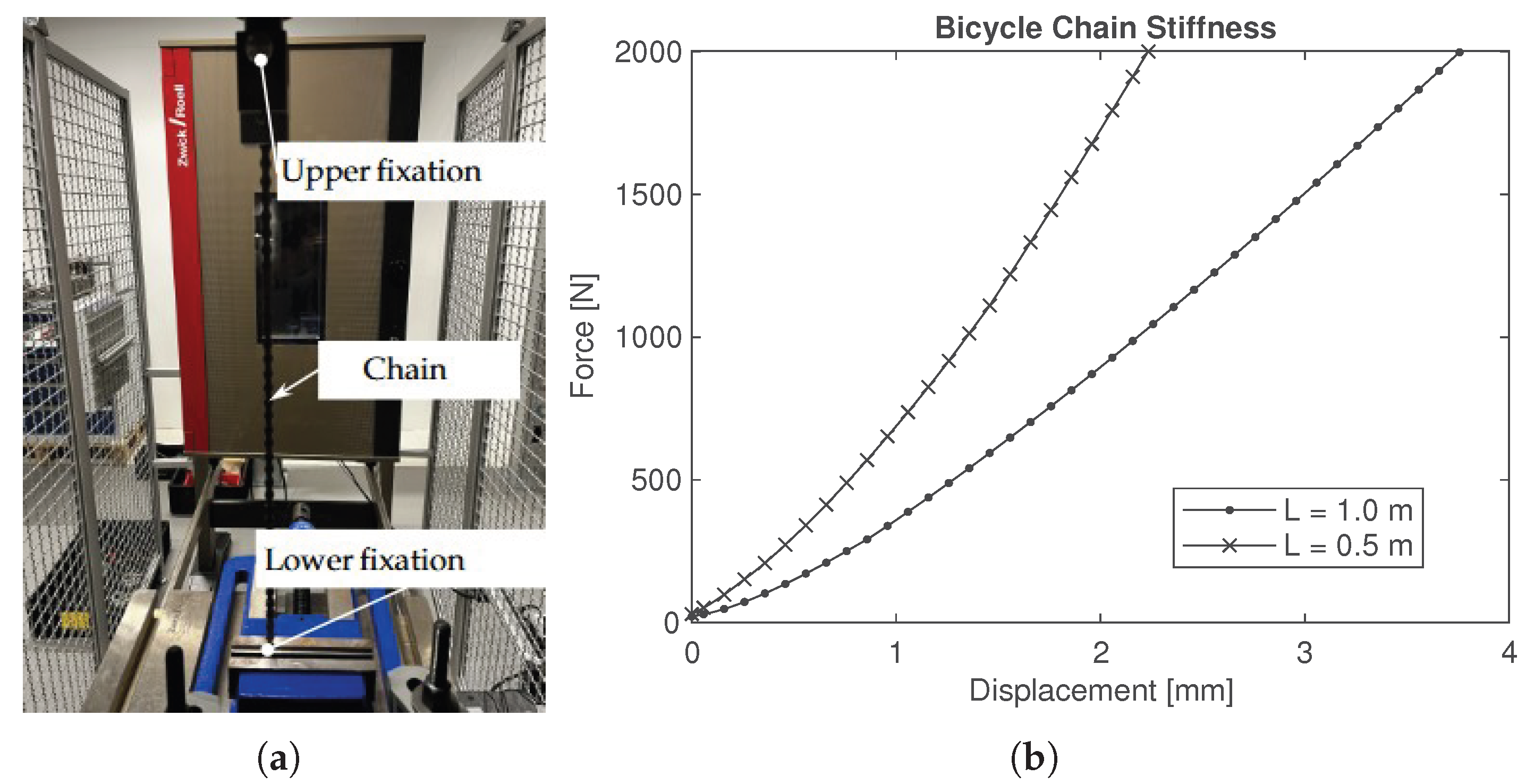

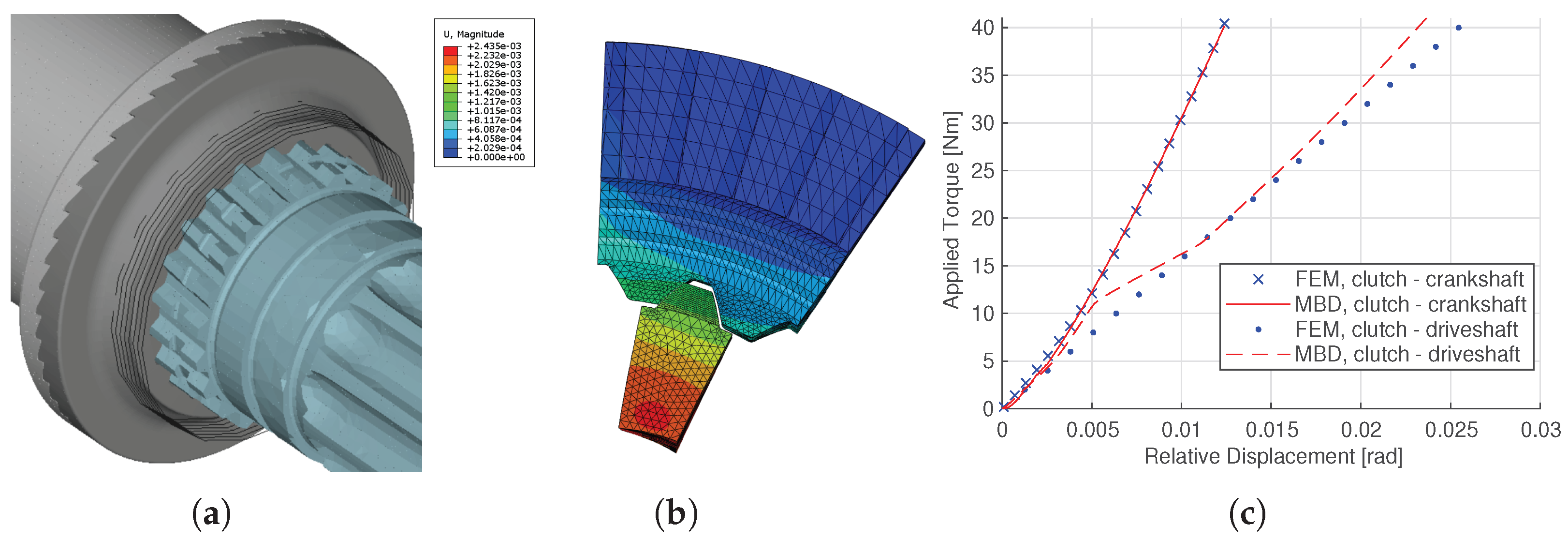

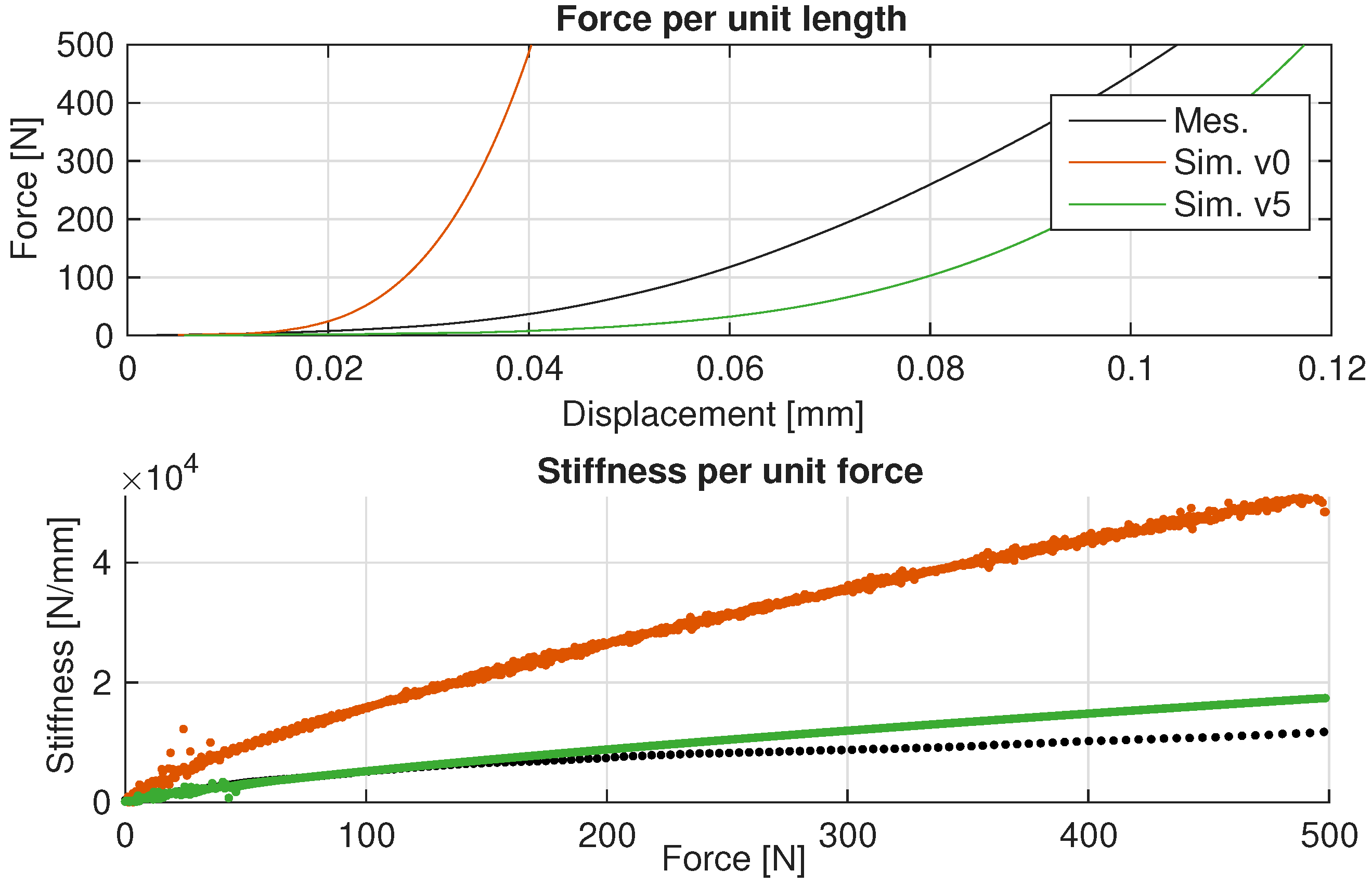

The clamping bodies of the frictionally engaged freewheel (iii) as well as the bicycle chain (iv) are simplified and implemented as pure surrogate stiffness. Therefore, the approaches use measurements to determine the change under load for force and displacement, or torque and angular displacement, respectively. For the freewheel, reference is made to our previous work, Steinbach et al. [6], without further elaboration. The procedure for the bicycle chain becomes evident from Appendix A.1. The resulting stiffness curves are implemented and interpolated as Akima [27] spline elements in the flexible MBD.

The contact stiffness for both clutch (v) and slide bearings (vi) is determined using a nonlinear FE preprocessing step, under which force and deformation are determined at a specific reference point by applying a certain motion. With the yielding characteristic, the same motion is applied at the reference point in a separate MBD optimisation. Therefore, the sequential quadratic programming (SQP) method is used to approximate the stiffness coefficient and the exponent of the contact force (). The MSC Adams specific routine used is called MSCSQP. For better calculation performance in the holistic MBD model, these contacts are implemented on rigid geometries relative to each other. An example illustration of this procedure is given in Appendix A.2.

The remaining structural parts (vii) are modal-reduced in an FE preprocessing step, during which the interface nodes are defined, which are needed for the MBD coupling. The modal reduction uses the component mode synthesis (CMS) principle. Therefore, the Lanczos solver is used for frequency calculation in the FE. The yielding files are converted to the MBD unit system and implemented as modal-neutral files (MNFs).

2.3. Dynamic System Relations

The transmission of the electromagnetic motor air gap forces predominantly arise as torsional torque over the drivetrain. The gear ratios act in this direction of rotation and increase the torque. This geometry-induced torsional characteristic has a significant influence on the dynamic relations of the system, as shown in the following. For a typical gear stage system, the total gear ratio is given as

which results in our case of two gear stages to

The tooth number acts at the rotor shaft, at the output shaft, and in between. There is a gear reduction since is referred to in Equation (17). The resulting total mass moment of inertia acting for the rotation analysed at the rotor shaft is

with the index imposing the rotational axis. For the applied case of the topology from Figure 1, this can be reduced for the gear stages to

Noticeably, acts as resistance to the rotor shaft’s torsional motion. With a gear reduction (), the proportional impact of the resistance from the individual mass moments of inertia () significantly reduces the higher the resulting ratio i is, since

This implies that the effective torsional mass moment of inertia is dominated by the rotor shaft for the input. In the opposite direction, at the output, the behaviour is reversed, since

with

As a consequence, the resistance caused by significantly increases and the drivetrain is hard to rotate, for example, when using the bicycle without electric motor support and no active freewheeling clutch. The torsional stiffness from any element within the drivetrain decreases quadratically, referred from the output to the input (rotor shaft) , since

with increasing angular deflection of . This indicates that any torsional stiffness referred to the input (rotor shaft) becomes significantly reduced the higher the gear ratio is at its position. This likewise applies to any torsional stiffness at other positions, for example, when considering the second shaft as output ().

The e-bike drive unit is typically tested under constant torque at a constant speed or at a linearly increasing speed. In the modelling, this can be achieved by constraining the angular acceleration, angular velocity, or angular displacement, which reduces the corresponding degree of freedom. It may have a significant influence on the system behaviour, depending on the specific system and its parametrisation. To leave this degree of freedom unconstrained, the initial and final rotational speeds can be approximated as follows to obtain the angular acceleration ()

with the duration of the increase. The resistance torque can be determined as follows, assuming a defined input torque of the rotor and negligible damping.

This output torque enables a linear ramp up equivalent to the required angular acceleration . Since spur gears have high efficiencies ( [28]), this assumption is considered valid for a simplified analysis. It differs as damping increases, but may serve as an initial indicator. This representation is required for a more precise analysis in the modelling, particularly when the e-bike drive unit is to be investigated without the bicycle chain. Control effects could also be incorporated, but this is outside the scope of this work.

2.4. Test Environment

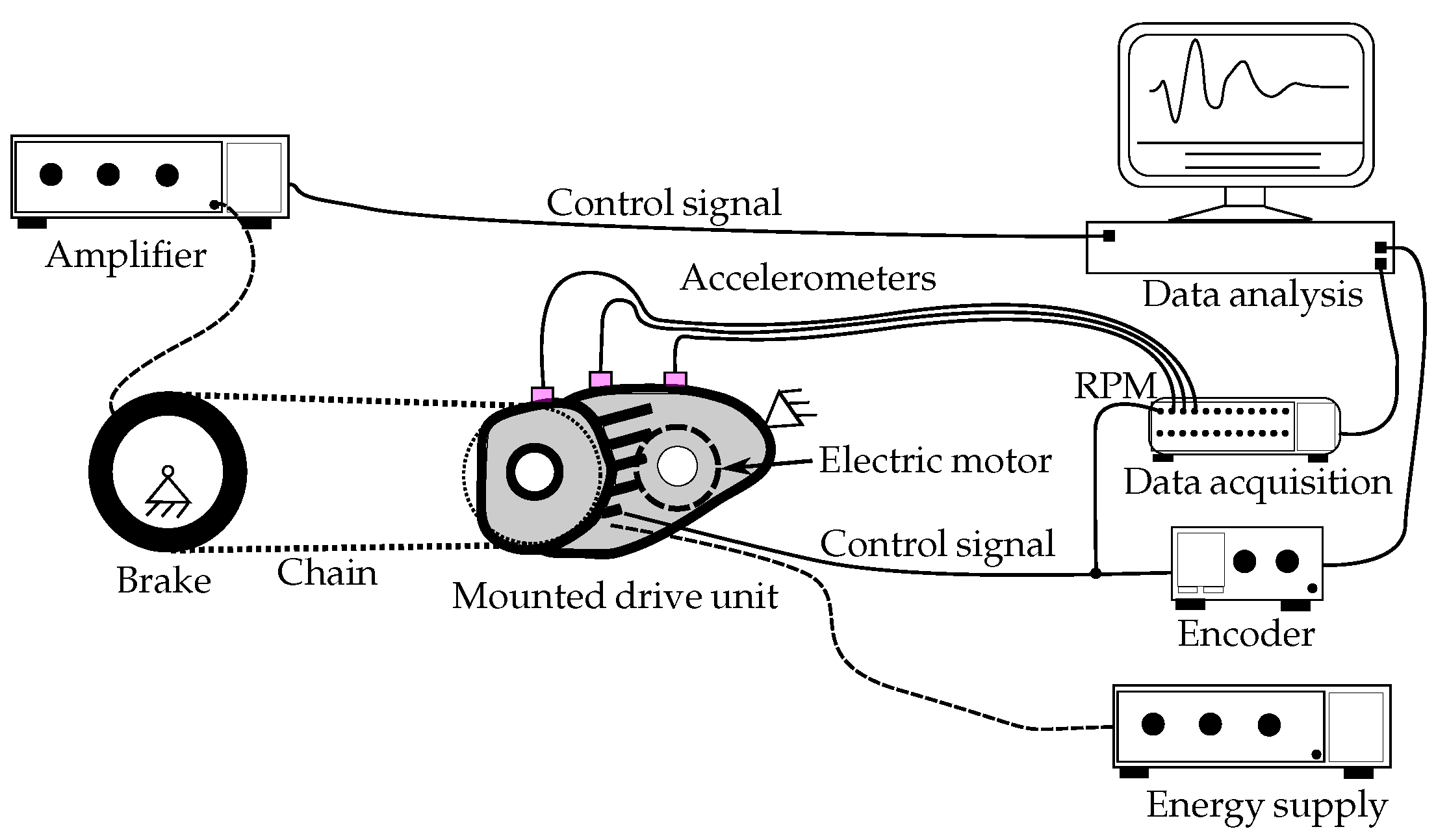

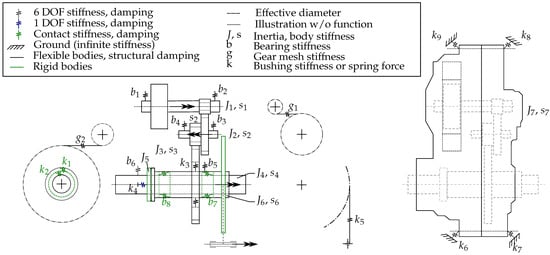

The test environment provides the framework for both the experimental measurement and the numerical simulation. It defines the boundary conditions that need to be similar to ensure a consistent comparison. Figure 3 presents the schematic measurement setup, whose basic mechanical setup is also reproduced in the modelling.

Figure 3.

Schematic measurement setup including the mounted and controlled drive unit, the data acquisition-related equipment, and the implementation of a brake to apply a resistance torque.

A computer performs the data analysis and controls the input parameters for the data acquisition module, the drive unit, and the magnetic powder brake. The drive unit’s control is internally governed. This is why an encoder is required to insert the input parameters, such as speed over time, and to receive the drive unit’s output signals. The data acquisition module captures the drive unit’s revolutions per minute (rpm) as a reference signal and has an internal decoder. The acceleration sensors measure the drive unit’s dynamic (surface) accelerations, whose signals are also recorded by the data acquisition module. The drive unit’s electric motor is powered separately via an energy source. The magnetic powder brake generates its braking torque through friction between a rotor and a stator using ferromagnetic powder. The amplifier and the degree of resulting friction indirectly control its torque magnitude. A bicycle chain connects the brake to the drive unit, which is mounted on a test rig.

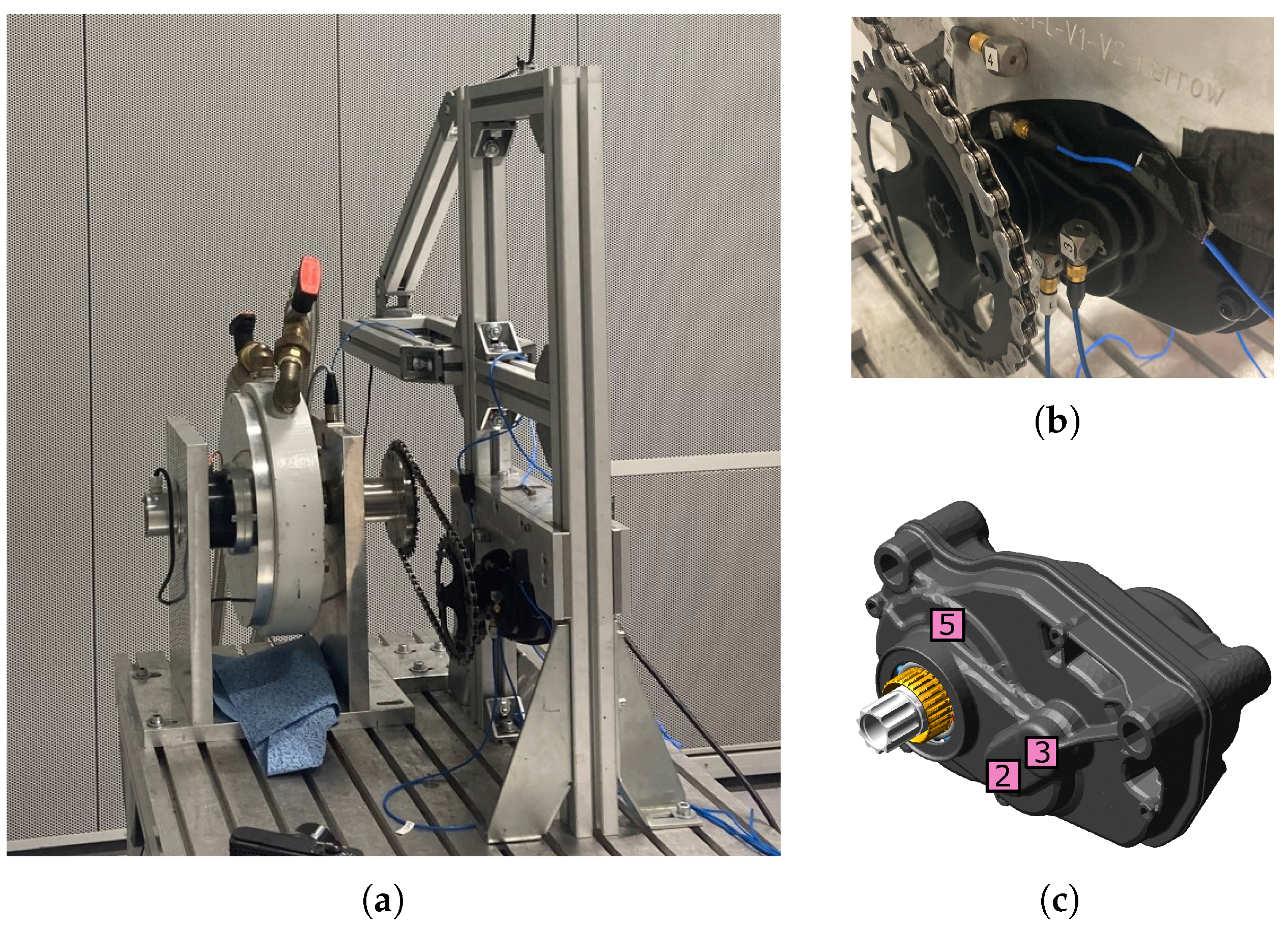

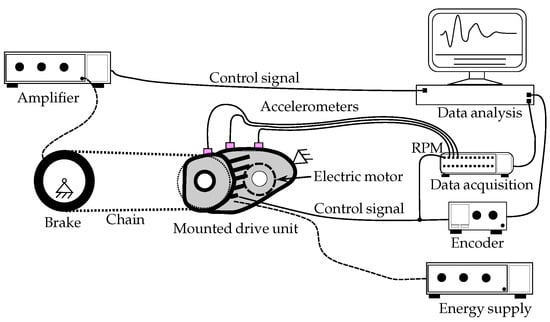

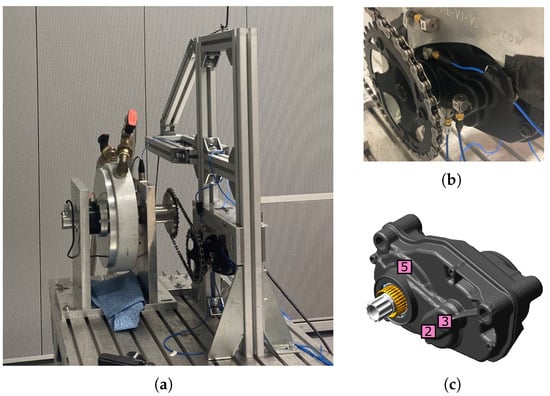

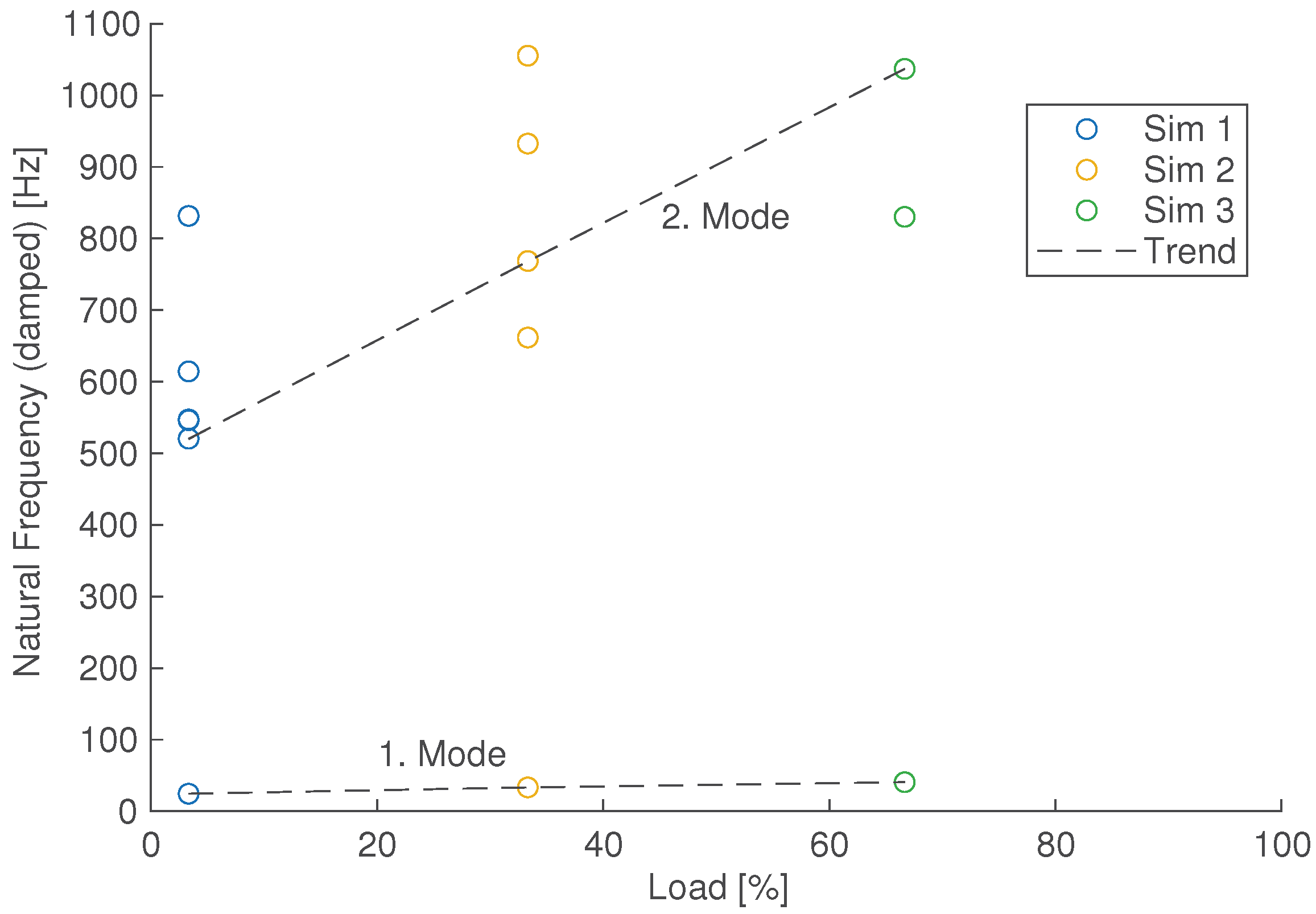

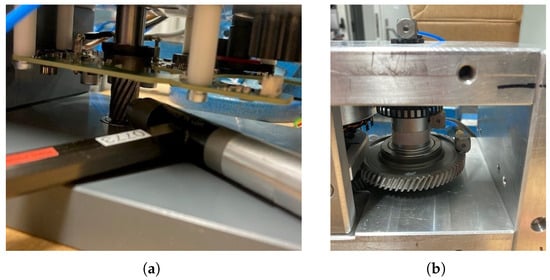

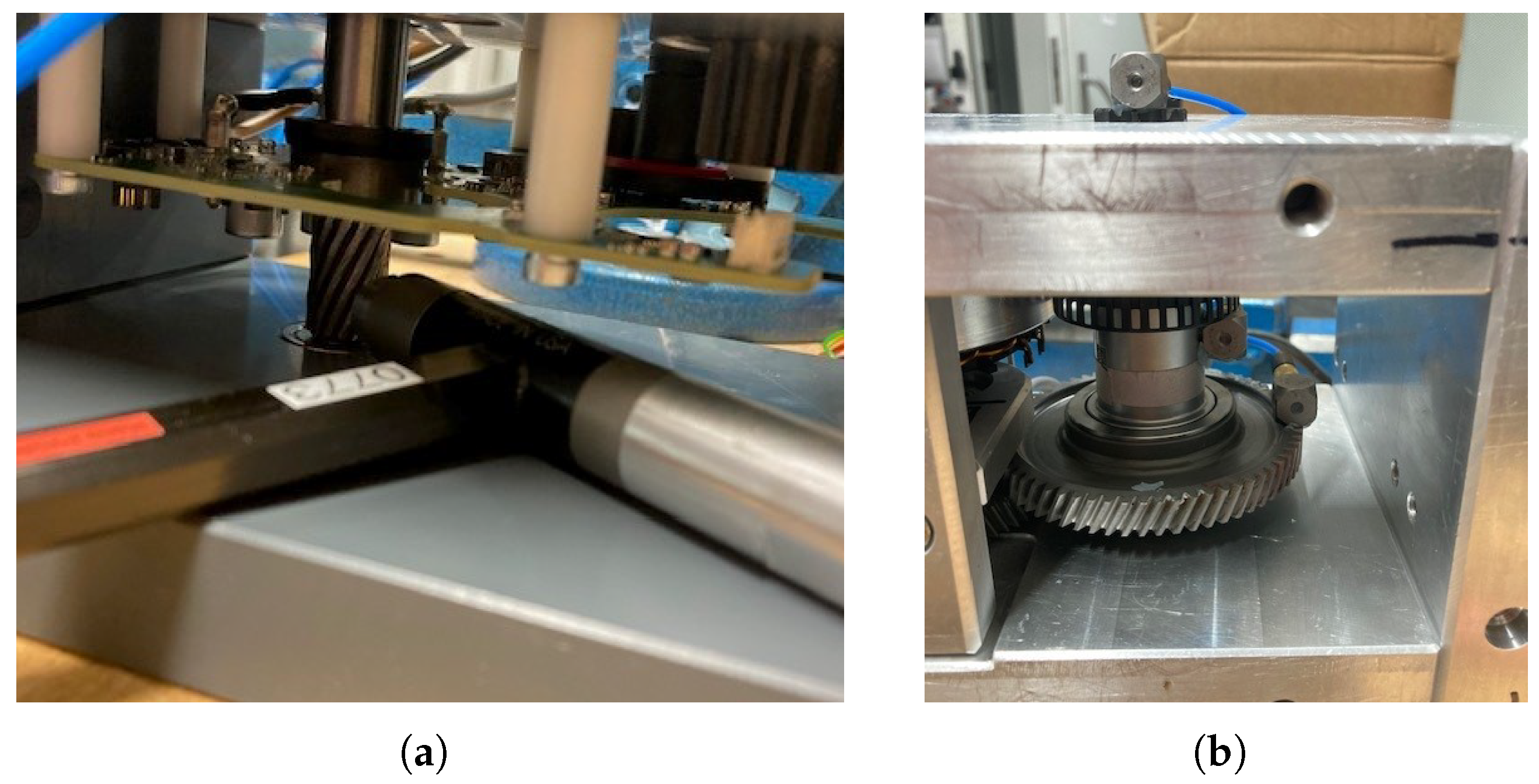

Figure 4 shows the test rig and the sensor positions in both the measurement and simulation to evaluate the acceleration.

Figure 4.

Measurement setup (a) of the test rig assembly and the positions used for the acquisition of acceleration signals in (b) the measurement and (c) the simulation. The numbers 2, 3, and 5 indicate the used sensor positions.

Figure 4a shows the assembled test rig. The connection of the bicycle chain to the brake is analogously represented in the modelling through a constraining motion by a revolute velocity and a surrogate chain stiffness. Tri-axial piezo-electric sensors are applied for measurement (see Figure 4b), whereas the simulation structure is preprocessed with interface nodes at the same locations as the sensors. The motions of these interface nodes are captured in the simulation. The indicated positions are clearly visible in Figure 4c by numbering. The sensor positions on the housing are selected to be close to the locations of the ball bearings within the e-bike drive unit. This allows us to capture the gear system’s dynamic behaviour as accurately as possible.

The accelerometers are of type Kistler 8763B050BT05 ( accuracy , g, g, Kistler Group) with a data acquisition device from Head Acoustics. The system is excited using the electromagnetic motor forces in both measurement and simulation. The measurement control and communication is applied over a CAN bus. The simulation is performed in MSC Adams with additional Bearing AT and Gear AT plug-ins, yet without any internal or external controlling. The sampling frequency in the measurement is at 48 , and the output time resolution in the simulation is 20 . With regard to the given sensor bandwidth and accuracy, this ensures a reliable analysis of up to ≈ 5 without violating the Nyquist criterion. Higher frequencies may be analysed for a relative comparison, but are affected by distortions in the absolute amplitude and phase angle captured by the accelerometers. The measurements are performed at room temperature of approximate 20° to 23°, and the sensors perceive regular calibration intervals. As the measurements are repeated with the same sensor setup and are relatively evaluated against the simulation (in terms of frequency), the measurement accuracy is considered sufficient for the purposes of this study without further investigation.

No additional filtering is applied to the simulated raw data. For the experimental measurements, a high-pass filter in the range of approximately 2 can be used due to the sensor characteristics (lower limit at ). As this cutoff range lies below the analysed frequency range, any impact of this filter on the results is expected to be negligible. For the signal processing, the MATLAB Signal Processing Toolbox is used. To generate the Campbell plot, the spectrogram function is used with a resolution of = 25 Hz. The orderspectrum function is applied to build the average order spectrum with an order resolution of 0.005. The spectrum is built upon the pspectrum function with = 25 Hz (Kaiser-window). As part of this, the internal default setups are used.

For the simulation, the Hilbert–Hughes–Taylor (HHT) solver is used, which shows the best results and proven convergence for an error size of 1.0 × 10−7 with a maximum step size of 5.0 × 10−6. The reference system is a CPU @ 3.6 GHz, with 4 cores, 8 logical processors, and 32 GB RAM, which is operated under Windows 10 with the Adams Version 2023.4.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Dynamics

This section examines the accuracy of the modelling approach to verify the correctness of the numerical results and to validate the developed methodology. This is conducted by comparing measured and simulated data under similar conditions. The used test rig and setup is the one described in the previous Section 2.4.

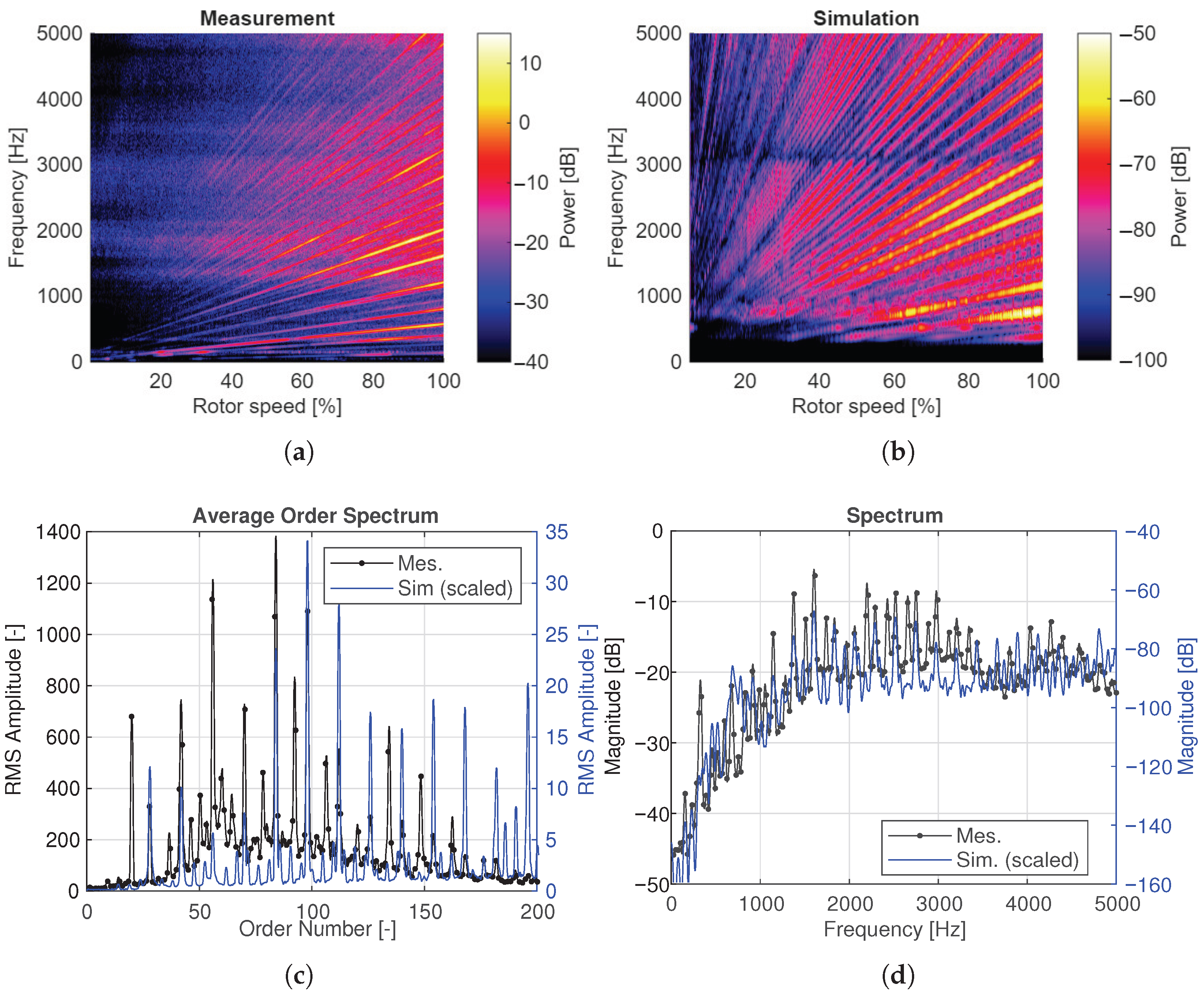

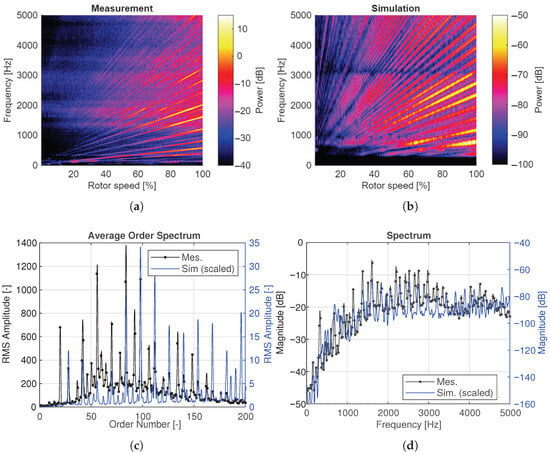

In the first test, the speed is linearly ramped from zero to maximum under constant torque (simulation details: simulated time 10 , step size 5.0 × 10−6, function evaluations 5.9 × 106, cumulative steps 2.4 × 106, order 2, elapsed time 19 34 ). In the second test, both the torque and the rotational speed per minute (rpm) are kept constant. As a consequence of the dynamic transient behaviour and the system interactions, comparable results are obtained for all applied sensor positions. is selected because it is located close to the output, and the dynamic quantities are amplified by the gear transmission. Figure 5 exemplarily presents the axial acceleration results designated as , which are collinear with the axis of rotation.

Figure 5.

Comparison between simulated and measured acceleration signals evaluated at the sensor position . (a) Measured ramp up. (b) Simulated ramp up. (c) Order-spectrum of ramp. (d) Steady state at 1000 rpm (rotor).

Figure 5a,b illustrates the Campbell plot from measurement and simulation. At a similar speed and frequency scaling, the amplitude (power in dB) is significantly lower in the simulation (approximately 5 dB compared to −60 dB for particular amplitudes). This could indicate that the simulation model is too stiff, as a lower structural stiffness would allow for larger vibration amplitudes due to increased displacements under the same excitation forces. Since the housing and its fixation to the frame are not examined in detail, this should be addressed in future investigations. In both cases, the orders increase, and resonances are crossed. A detailed visual comparison is not possible at this resolution using the Campbell plot. However, it proves that the simulation runs stably without convergence issues since no numerical artifacts are apparent, which most likely appear in the acceleration response.

To analyse the results more precisely, the averaged order-spectrum is used. It allows us to compare the peak positions of the single orders, enabling a more precise comparison. The order-spectrum refers to the rotational speed of the rotor as first order and indicates the speed-dependent spectrum as root mean square (RMS) amplitude (see Figure 5c). Using the min–max normalised order amplitude (), and comparing the positions of corresponding order peaks, a mean order deviation of 0.03% with a maximum deviation of 0.07% is observed relative to the order resolution. The normalised amplitude shows a mean deviation of 9.1% and a maximum deviation of 0.38 when expressed as normalised RMS amplitude. It should be noted that these values are approximations based solely on matched peak positions and therefore depend on the selected analysis procedure. In total, 15 significant matching orders are identified, while five dominant orders do not reveal a consistent matching behaviour.

Qualitatively, a major part of the orders’ peaks match the positions, while quantitatively, there is a clear deviation. This is also evident from the spectrum in steady state (see Figure 5d), which is performed at a rotor speed of 1000 min−1. The average frequency deviation of similar resonance peaks is approximately 0.06%, with a standard deviation of . The normalised amplitude deviates with 17.3% and a maximum factor of 4.8. Consequently, the overall trend of the resonance peaks can be considered to be well captured, enabling a reliable qualitative assessment. However, it must be emphasised that further model refinement is required before robust quantitative conclusions can be drawn.

3.2. Mode Shapes

Table 2 lists the first 30 modes, which are calculated in the flexible MBD system using a modal analysis of a linearised load point under low torque and under consideration of the fixation by the bicycle chain. This ensures that the contacts are interacting so that the true system behaviour can be analysed. The influence of the housing is neglected in this analysis, as it is assumed to be negligible (see Section 3.5). The given frequency is the damped natural frequency , computed from the undamped natural frequency using the damping ratio relative to critical damping (). The defined mode shapes approximately categorise their occurrence.

Table 2.

Frequencies and damping ratios of the system modes from the gear stage.

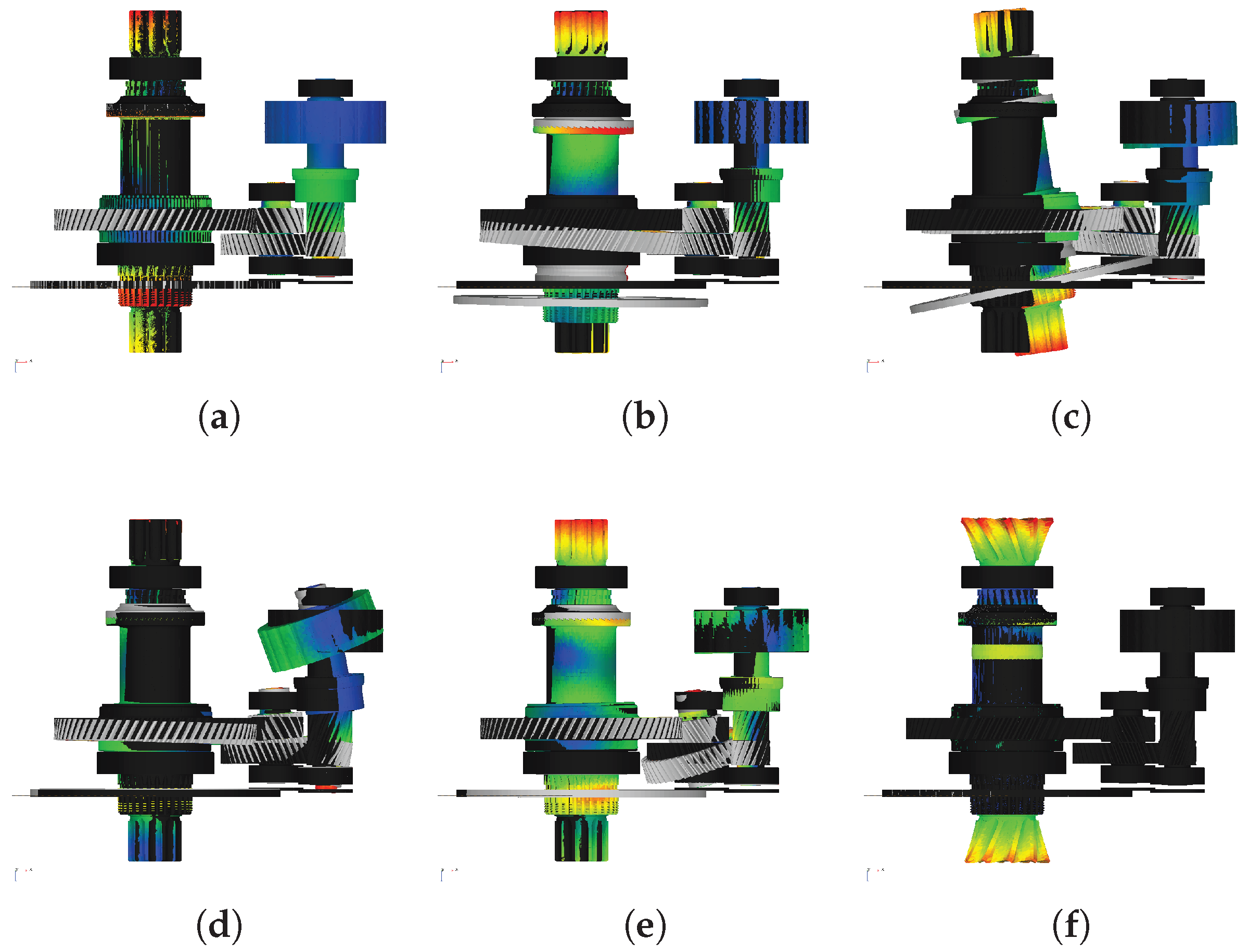

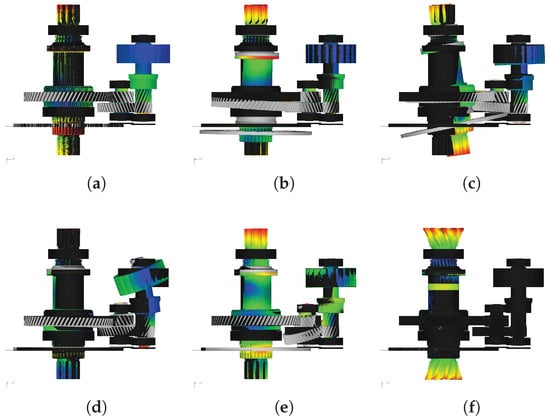

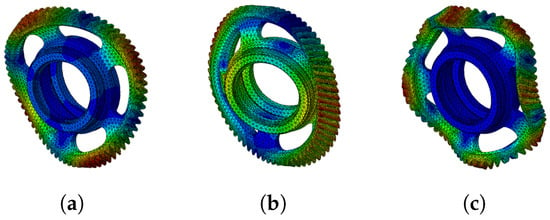

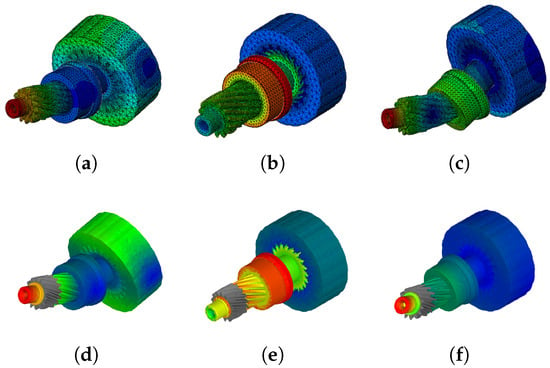

According to Section 2.1, there are three conditions of the system when considered in the frequency domain: rigid body oscillations over the system, structural oscillations of single components (fix–free, or fix–fix), and the combination of those. Due to the multitude of modes (see Table 2), only the illustration of a few serves as examples below (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Example of simulated system modes under low load with frequency and damping ratio of (a) 24 Hz, 0.2%. (b) 520 Hz, 0.7%. (c) 1801 Hz, 1.3%. (d) 3955 Hz, 2.8%. (e) 5673 Hz, 9.0%. (f) 7317 Hz, 96.7%.

In Figure 6, the modes (a)–(c) are predominantly rigid body oscillations at 24 , 520 , and 1801 with a damping ratio of 0.2%, 0.7%, and 1.3%, respectively. Thereby, the shape (a) is a decisive torsional rotation of the rotor shaft, the shape (b) is a decisive axial deflection of the output shaft, and the mode (c) is a tilting of the same one. The mode (d) is at 3955 with 2.8% damping. Its shape represents a rather pure elastic, structural mode of the rotor shaft. The mode (e) is at 5673 with 9.0% damping and shows an interaction of all components. The mode (f) at 7317 serves as an example for an unrealistic numeric mode, since its shape is rather implausible and the damping ratio with 96.7% is significantly high. The overview of all frequencies at which some modes are present is listed in Table 2.

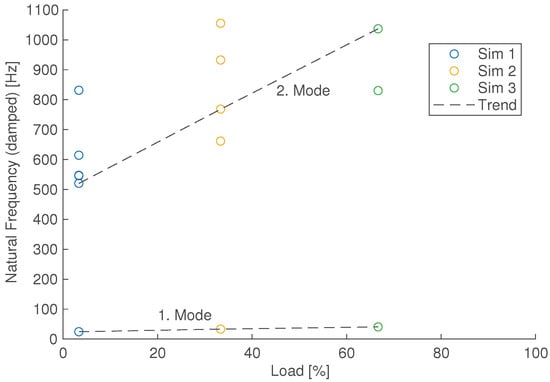

In total, the simulation proves that there is a multitude of modes present in the drivetrain which acts as a dynamic multibody system even without (!) the structural influence of the surrounding housing and mountings. Because of the relatively small masses and mass moments of inertia, in combination with the high stiffness arising from elastic material and contact properties as well as the low damping, the majority of the modes occur at comparatively high frequencies > 500 . However, there is the first mode at around 24 , which is in a structurally relevant frequency range and receives the strongest excitation by the motor forces. Therefore, it shall be further analysed in Section 3.3. Additionally, the modes show a load-dependent behaviour in terms of their natural frequency (see Appendix A.3) with potentially changing shapes, which is not further analysed. The modes’ relevance arises primarily with their excitation, so Section 3.4 investigates the relevant frequency range under operating conditions.

3.3. Torsional Response Behaviour

Based on prior experience, the first torsional system mode from Table 2 is particularly sensitive to the e-motor excitation due to potential torque ripples. On the one hand, it lies in a specific relevant frequency range, since a rotational rotor speed of, e.g., up to 5000 min−1, corresponds to a maximum frequency of 83 , which crosses the natural frequency of this mode (24 ). On the other hand, it is assumed that through the decisive transition reduction in the gear system, none of the other modes (≥ 520 ) are significantly excited solely through the gears’ rotation frequencies, since their first few orders remain below the rotor’s frequency.

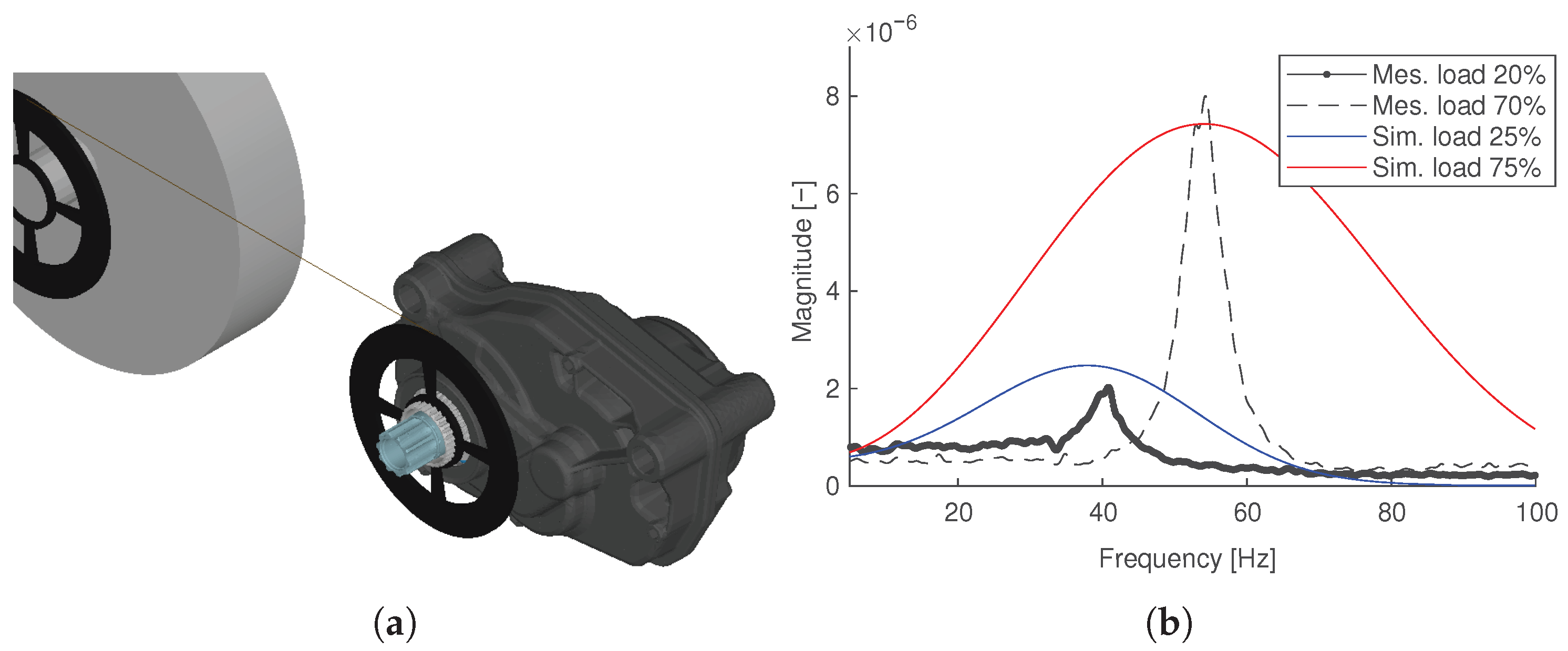

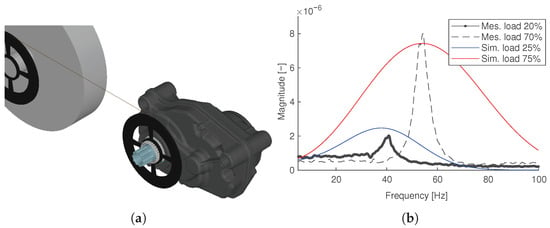

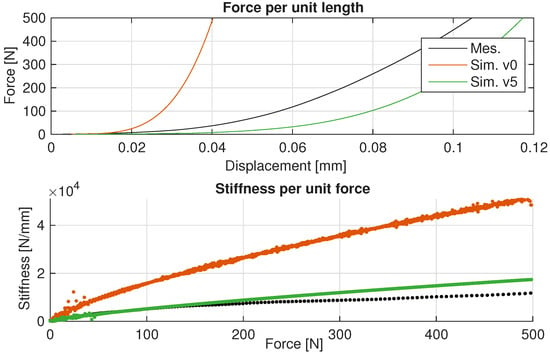

Due to the given relevance for operating the system, and the fact that in this force-flow direction all modelling assumptions comply with a full system, it is further analysed and used for additional model validation. The boundary condition (clamping via chain to a brake) is implemented in both the simulation and the experiment as illustrated in Figure 7a. For the measurement, the CAN bus signals are evaluated to capture the torque or rpm signal of the rotor shaft. Thereby, one trial is performed during a ramp up with low torque and one at high torque (see Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Torsional resonance in the system. (a) MBD assembly illustration with schematic brake. (b) Comparison of the response function for measurement and simulation.

When comparing the resonances in Figure 7b, it becomes evident that the proportional relation between simulation and measurement is approximately similar. The wider shape of the curve from the simulation is linked to the resolution of the time discretisation, but may additionally come from further interference. Moreover, the load-dependent behaviour is visible, since the resonance frequency increases with increasing load. This is due to the load-dependent stiffness, which increases together with the applied load. Since the resonances match qualitatively between simulation and measurement, this indicates the validity of the simulation. Moreover, the pure presence of this mode covers the assumptions by Section 2.3 referring to the system’s mass momentum of inertia in Equation (20) and stiffness in Equation (24), which act on the rotor shaft on the system level.

3.4. Relevant Frequency Range

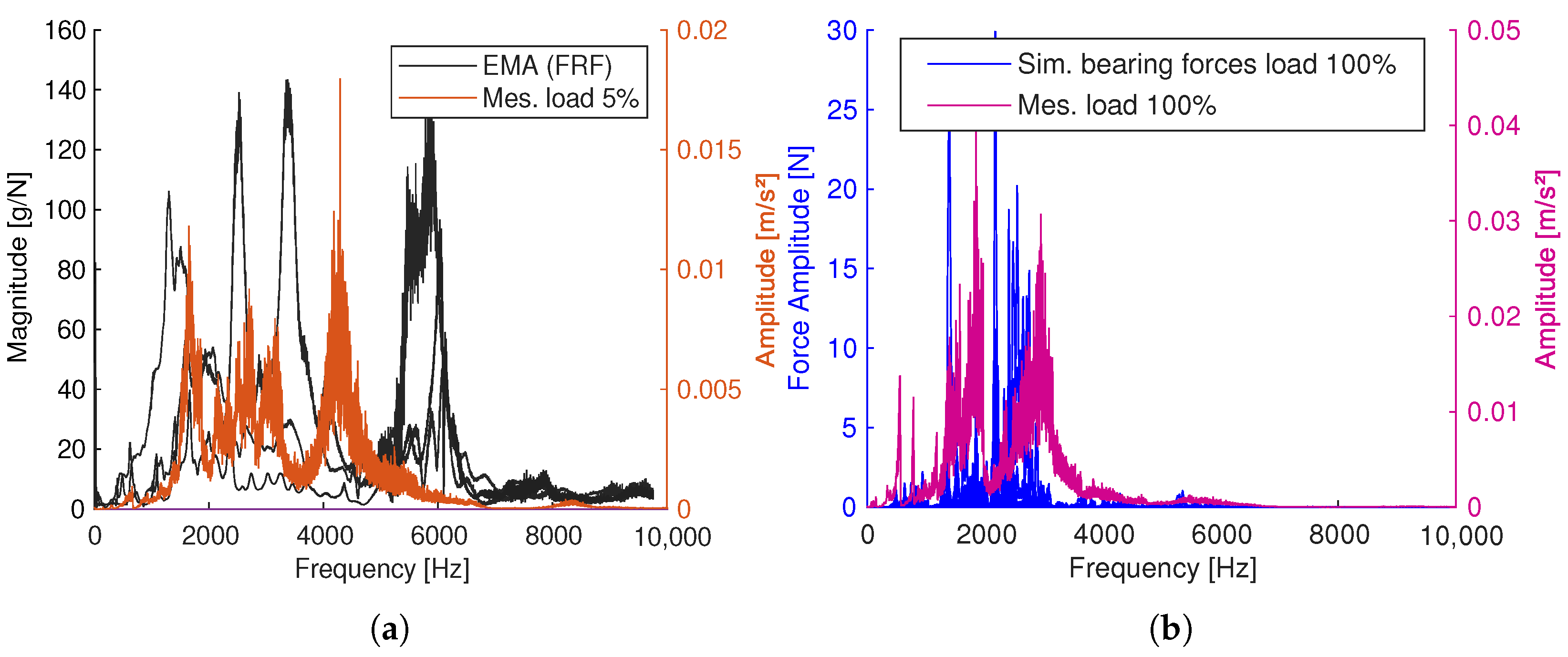

To identify which modes are of relevance, the frequency range under excitation is analysed. The first trial considers an experimental modal analysis (EMA) of a unique test rig, in which the e-bike drive unit housing is substituted by rigid plates (see Appendix A.4). In this particular setup, the mode shapes would be of interest but are not accessible due to the limited space. Nevertheless, they are used to identify a rough estimate of the resonance behaviour directly from the drivetrain without the influence of the housing. The EMA uses a modal hammer and roofing sensors, which are directly placed on the shafts and gears. The same type of e-bike drive unit is mounted in the previously mentioned test rig of Section 2.4 but with a normal housing.

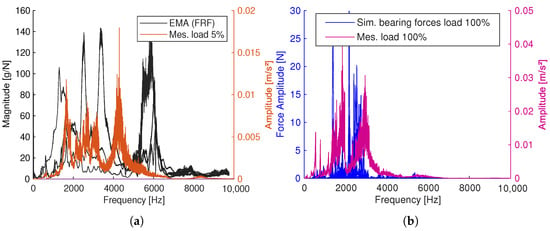

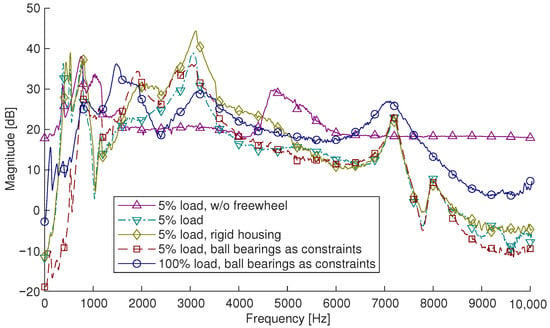

Figure 8a shows the comparison in the frequency domain from the EMA and the frequency spectrum determined over a ramp-up under low torque. For the EMA, this is carried out with the drivetrain rotationally constrained in order to enable a rough comparison, as the contacts are thereby locked. Since this is associated with a low preload, the ramp up is likewise considered at low torque. A similar comparison is conducted for simulation and measurement, but at high torque and solely for a ramp-up, since an EMA is not feasible in the given setup for high torque. The simulation takes the bearing forces into account since these best possibly indicate the excitation of the structure, whereas the acceleration amplitude is considered for the measurement (see Figure 8b).

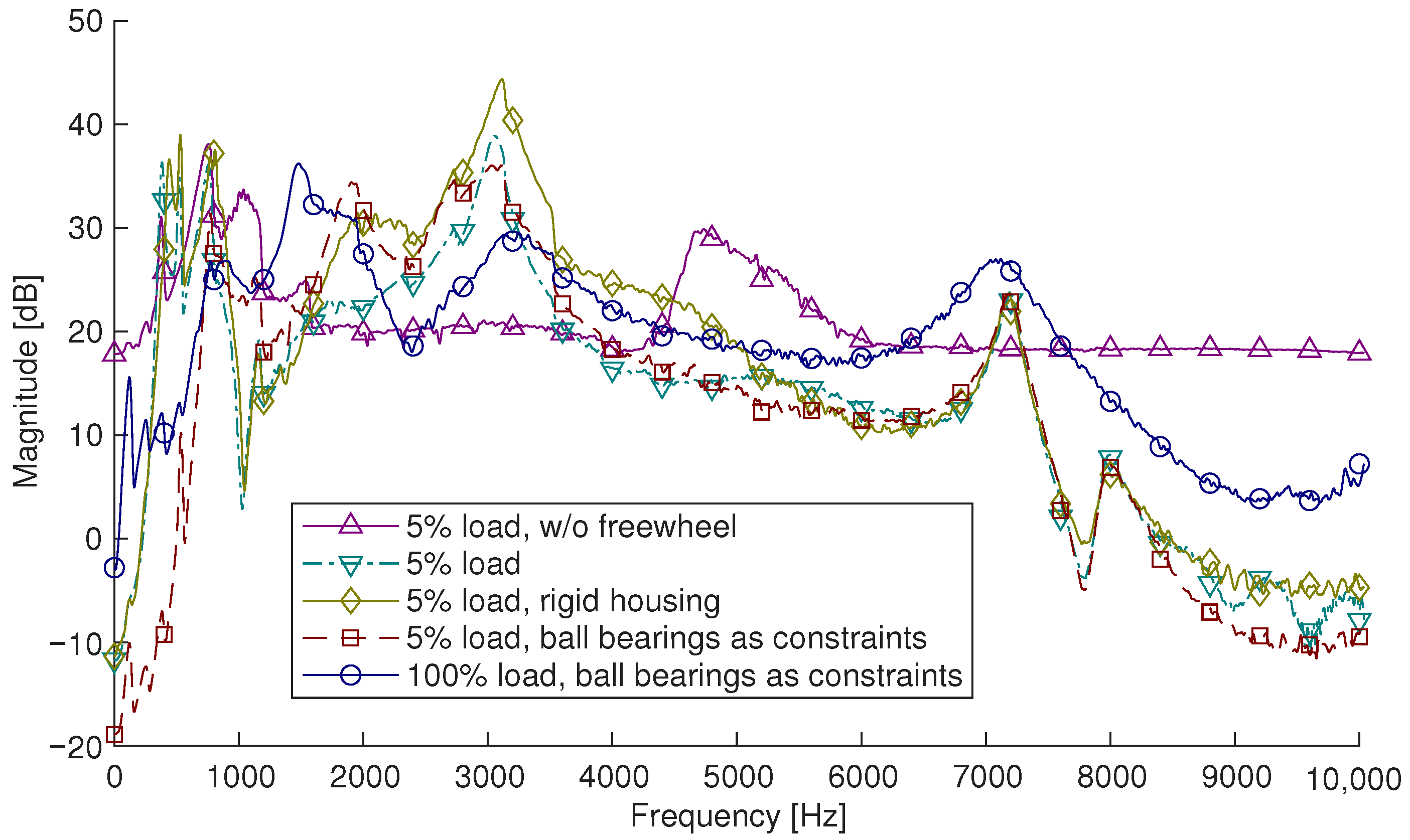

Figure 8.

Present resonances and frequency range (a) Comparison of experimental modal analysis (EMA) and spectrum of ramp up under low torque. (b) Comparison of simulation and measurement under high torque.

The significant frequency range of the EMA ranges from 0 kHz to 6.1 kHz, whereas the spectrum of the ramp-up measure under low torque ranges from 0 kHz to 5 kHz (see Figure 8a). Under high torque, this frequency range reduces to 0 kHz to 3 kHz (see Figure 8b), while the amplitude increases, e.g., from 0.012 ms−2 at 4kHz to 0.03 ms−2 at 3 kHz. This indicates two things: Firstly, the operating condition has great significance to the resonance behaviour. Secondly, the resonances identified by the EMA clearly demonstrate that a variety of modes exist which only arise when the gearbox is considered as a multibody system. The simulation reveals an excitation via the bearing forces within an approximately identical frequency range (see Figure 8b), which implies a valid modelling approach. In particular, the bearing forces significantly indicate the excitation of the system that is part of any insufficiently represented transfer paths to the housing structure where the acceleration is measured. For completeness, the reaction forces of the stator additionally excite the housing structure but are not further elaborated on in this study.

3.5. Modelling Restrictions

The modelling restrictions are elaborated on the utilised e-bike drive unit model to maintain clarity but can be transferred to comparable systems. The different components are labelled by numbers in Figure 9, where each number represents a specific modelling approach.

Figure 9.

Flexible multibody dynamic model of the e-bike drive unit. Each number represents a different modelling approach.

- 1.

- The chain is simplified by considering only its stiffness, which neglects both the resonances from chain modes and the influence of the mass moment of inertia. The flexibility of the two chainrings is disregarded as well as the precise dynamics of the brake, which is simply constrained by a given rotational motion. This is assumed valid, since the chain stiffness contributes to a decoupling from the drivetrain, while the dynamic behaviour of the brake (and downstream systems) is of no interest.

- 2.

- The gear stage modelling approach substitutes the tooth geometry of the gear bodies with rigid gear rims on which the surrogate models of the flexible teeth are employed. By this, some degrees of freedom for the modal representation of the gear body may be constrained by the artificially employed rigidity of the coupling interface nodes. This is particularly relevant in the present modelling of the very thin-walled gear bodies (see Appendix A.5), whereas the rigidity influence of the coupling nodes at thicker gear bodies is negligible.

- 3.

- The ball bearings are based on a surrogate stiffness, which is quasi-statically exploited. This approach simplifies the rolling behaviour of the balls and neglects elastohydrodynamic contact. Since the dynamic system behaviour of the e-bike drive unit contains a maximum revolution of 5000 min−1 and the resulting fault is expected to be small, this approach is considered valid. Moreover, due to simplified geometric representation and available nominal values, the precise depiction of the inner geometry may differ, leading to divergent stiffness curves (see Appendix A.6).

- 4.

- The clutch and slide bearings are considered as rigid bodies with contact stiffness. This enhances the computational efficiency but neglects the influence of structural deformations. This may distort the contact behaviour and the resulting stiffness, e.g., visible as deviation in curves from the geometric elastic FEM to the geometric rigid MBD (see Appendix A.2). Also, dry friction is applied, which in this particular case is assumed valid, since the relative velocity of the clutch and slide bearing is zero in theory, as long as the system is engaged. Otherwise, the maximum frequency at the output shaft is very low, e.g., 2 , which corresponds to an almost implausible high rider cadency of 120 min−1.

- 5.

- The frictionally engaged freewheel is substituted by a surrogate stiffness which represents the elasticity of the clamping bodies. The influence of the clamping bodies’ mass is expected to be negligibly low and, hence, attributed to the gear body. The load-dependent stiffness behaviour reflects the actual state of the system, but does not provide a precise representation of the geometric positions of the clamping bodies. This is assumed valid, because the underlying measurement system is similar in geometric installation and operation to the applied system. However, it is conceivable that the gradient of the stiffness curves differs in the spatial directions, dependent on the clamping engagement. Moreover, this approach does not capture slip effects caused by load switches.

- 6.

- Analogous to points number 2 and 7, the shaft assemblies consist of the modal reduced structures using CMS, with a partially implemented surrogate model of the gear tooth flexibility. Due to the geometric linear isotropic material behaviour, the CMS method is well-suited for the shafts, except for the rotor. The rotor exhibits nonlinear behaviour [29,30,31], so either linear-elastic models for each load point would be needed or a nonlinear approach is needed. However, the workflow delivers approximate close mode shapes and natural frequencies after the reduction and gear implementation (see Appendix A.7), assuming it is valid.

- 7.

- The housing is simplified using the component mode synthesis (CMS) via Craig–Bampton and orthonormalisation. The resulting modal representation is linearised at one specific operating point. Hence, potential geometric nonlinearities arising from the load influence are not captured, which might be present due to the complex geometry. Moreover, in the modelling, the two housing segments, including the stator, are tied to each other, neglecting any influence from contact points and joint damping. In the scope of this work, the housing has minor relevance, which becomes evident when comparing the spectrum of the system with rigid and flexible housing approaches (see Appendix A.8), However, this should be taken into account in future work for more precise modelling.

- 8.

- The fixation of the housing to the ground is not mapped properly and substituted by an approximated bushing stiffness. This needs to be further examined, as the rigidity of the fixation significantly influences the possible motion of the entire e-bike drive unit. Deviations towards measurements may result from this contribution.

In the future, high priority can be given to optimising both the housing structure (restriction 7) and its fixation to the frame (restriction 8) since they contribute significantly to the system rigidity. Furthermore, the nonlinear influence of rotor and stator (restriction 6) should be optimised, since it has a direct impact on the excitation level of the system.

Medium priority can be given to the fully flexible representation of the gear stages (restriction 2), as their unmapped modes lie in a higher frequency range and are expected to have minor relevance to the structural behaviour. However, the related representation contributes to the system’s rigidity and therefore needs to be further investigated and confirmed. The clutch and slide bearings (restriction 4) in combination with the frictionally engaged freewheel (restriction 5) build one subsystem in this particular case. Hence, they should be analysed and optimised as one package. Their combined interaction may result in unwanted nonlinearities with unknown consequences towards modes’ shapes, resulting resonances, and, logically, excitations through stiffness discontinuities.

Low priority can be given to the optimisation of the chain (restriction 1), since the stiffness influence is considered and no further significant behaviour is expected. Likewise, the bearing optimisation (restriction 3) is of minor importance, since the stiffness impact is known and the quasi-static modelling is sufficient due to the tendency towards low speeds.

4. Conclusions

This work develops and validates a flexible multibody model of an e-bike drive unit, providing new insights into its structural dynamics. Combined with measurements, the simulations identify system-level vibrations and explain the underlying interactions via system topology and mathematical relations. It can be shown that, at the system level, the gear ratio and topology impose high effective inertia and low stiffness on the input shaft with the mounted rotor. Consequently, a torsional mode arises, dominated by a rigid-body rotation of the rotor shaft. This mode is governed mainly by the elasticities of the frictionally engaged clamping freewheel and the bicycle chain when the drivetrain is braked or coupled to a high-inertia load. It is critical because its frequency lies within the operating range (<100 Hz) and can become excited through the electromagnetic motor forces. In the case of an unfavourable drive unit design and without countermeasures, this may result in perceptible, unpleasant pedal vibrations.

Beyond the first mode, the drivetrain exhibits 27 additional system modes in this configuration in the range of 0.5 kHz to 10 kHz. These arise solely from the multibody couplings between the gear stages and their connected components, even without the housing directly influencing them. The modes arise as rigid-body oscillations, single-body structural modes, or combinations thereof, governed by diagonal stiffness terms and off-diagonal couplings between rigid and flexible components. Because the stiffness is load-dependent, their frequencies vary under load and mode veering may occur. Although the behaviour is solely examined for one specific drive unit design, it is highly likely that similar characteristics occur in comparable architectures. Thereby, these dynamic properties are essential for the drive unit’s design layout and durability, especially of the electric motor and the gear stages, the rider’s perceived comfort through noise and vibration, and the bicycle frame integration.

Considered separately, the mentioned modes have no relevance without any excitation forces, which is why the excited behaviour during operation is investigated on a test rig environment. During operation, resonance amplitudes occur up to ≈6 at almost no load, up to ≈5 at low load, and up to ≈3 at high load. Their vibration amplitudes increase with the operational load, while the resonance band narrows proportionally. The mentioned frequencies are expected to shift with different drivetrain configurations. These resonances excite the surrounding structure significantly over the bearing forces. In particular, it can lead to decisive vibrations of the bicycle frame, which the rider perceives as uncomfortable noise. Hence, further investigations should minimise the present resonances through model-based optimisation of the bearing stiffness. In this context, one should also consider the impact of the components’ mass moment of inertia and elasticity. The resonance information could also be used to optimise the bicycle frame’s mode shapes to avoid dynamic excitation.

The results are based on a holistic system-level consideration of the e-bike drive unit within a test rig environment, using both flexible multibody dynamic simulations and specific measurements. The Craig–Bampton component mode synthesis and several obtained surrogate stiffnesses, including contact, enable the flexible representation based on the floating frame of reference. Consequently, the system representation is valid for structural flexibility with linear-elastic behaviour under small perturbations around an equilibrium, so the material nonlinearities of the rotor, stator, and potentially the housing are linearised and not continuously mapped. The quasi-static determination of the surrogate stiffnesses does not capture highly dynamic behaviour, such as frequency dependence and elastohydrodynamic contacts, and limits the results to low to medium dynamics. Also, a few rigid representations are contained, which are expected to influence the results, and the housing fixation needs further research attention.

Despite the qualitative validation, a quantitative comparison would enhance the accuracy and credibility of the results. Therefore, future research should consider displacement measurements directly on the shafts and analyse the results as order-cuts to analogous simulations. Thereby, the boundary condition of the fixation from the housing to the test rig should be refined. The housing, rotor, and stator should be characterised more precisely, e.g., using the modal assurance criterion for an alignment at representative operating points and by adopting alternative formulations to capture joint damping and nonlinear elasticity. A fully flexible modelling of the gear wheels, slide bearings, and clutch should be analysed to quantify its influence and determine whether such a representation is necessary. Finally, a modal analysis of the drivetrain without housing in a preloaded state, to ensure that the contacts are engaged, would provide a suitable basis for comparison with the simulation’s system-level modal analysis. In conclusion, this study reveals fundamental insights into the structural dynamic behaviour of an e-bike drive unit. It provides a clear baseline for future research, enabling more focused examinations of relevant effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.S. and D.R.; methodology, K.S., D.L. and I.G.; software, K.S.; validation, K.S.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, K.S.; resources, K.S.; data curation, K.S.; writing original draft preparation, K.S.; writing—review and editing, D.R., I.G. and P.K.; visualisation, K.S.; supervision, D.L, I.G., P.K. and D.R.; project administration, K.S., D.L. and D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Selected data may be shared by the authors upon reasonable request and with prior approval from Robert Bosch GmbH.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Robert Bosch GmbH for providing the resources that enabled this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Kevin Steinbach and Dominik Lechler were employed by the company Robert Bosch GmbH. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relation ships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. As part of that, the authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Nomenclature

The following nomenclature is used in this manuscript. Block subscripts (rr),(rf),(fr) and (ff) refer to the corresponding matrix partitions with respect to rigid, rigid–flexible, flexible–rigid, and flexible coordinates:

| Mass matrix | |

| Global stiffness matrix | |

| Craig–Bampton stiffness | |

| Bushing stiffness | |

| Global damping matrix | |

| Craig–Bampton damping contribution | |

| Rotation matrix in the inertial frame | |

| Transformation matrix of the bushing into the reference frame | |

| Damping matrix of the bushing | |

| Relative displacement in the bushing between bodies a and b | |

| Relative velocity between the two bodies | |

| Jacobian with respect to rigid coordinates | |

| Jacobian with respect to flexible coordinates | |

| Relative rigid Jacobian of the bushing | |

| Relative flexible Jacobian of the bushing | |

| Frequency-dependent effective stiffness | |

| Stiffness matrix of the bushing | |

| Generalised coordinates | |

| Rigid-body generalised coordinates | |

| Flexible generalised coordinates | |

| Time derivative of rigid coordinates | |

| Time derivative of flexible coordinates | |

| Acceleration of rigid coordinates | |

| Acceleration of flexible coordinates | |

| Rigid part of an eigenvector | |

| Flexible part of an eigenvector | |

| External forces | |

| Coriolis and centrifugal forces | |

| Constraint forces (e.g., from bushings) | |

| Rigid-body translation | |

| Body-fixed coordinates in the undeformed state | |

| Global position of the considered point | |

| Velocity of the point | |

| Acceleration of the point | |

| Mode matrix / spatial shape functions | |

| Craig–Bampton constraint modes | |

| Craig–Bampton fixed-interface modes | |

| Individual shape function in the Rayleigh–Ritz approximation | |

| Elastic displacement at position | |

| Rigid-body motion parameters | |

| Flexible modal coordinates | |

| Circular frequency |

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Adams | Automated dynamic analysis of mechanical systems |

| AT | Advanced technology |

| CAN | Controller area network |

| CMS | Component mode synthesis |

| CB | Craig–Bampton |

| EMA | Experimental modal analysis |

| FE | Finite element |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| FFRF | Floating frame of reference formulation |

| FRF | Frequency response function |

| HHT | Hilbert–Hughes–Taylor |

| MBD | Multibody dynamic |

| MNF | Modal neutral file |

| MSC | MacNeal-Schwendler corporation |

| RMS | Root means square |

| SQP | Sequential quadratic programming |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Figure A1.

Quasi-static tension measurement to characterise the chain stiffness. (a) Test arrangement. (b) Stiffness curves.

Figure A1.

Quasi-static tension measurement to characterise the chain stiffness. (a) Test arrangement. (b) Stiffness curves.

Appendix A.2

Figure A2.

Example illustration of the contact stiffness analysis and implementation. (a) Rigid multibody dynamic model. (b) FE contact deformation analysis. (c) Comparison of contact deformation behaviour between FE and MBD with MSCSQP optimised contact parameters.

Figure A2.

Example illustration of the contact stiffness analysis and implementation. (a) Rigid multibody dynamic model. (b) FE contact deformation analysis. (c) Comparison of contact deformation behaviour between FE and MBD with MSCSQP optimised contact parameters.

Appendix A.3

Figure A3.

Example illustration of the load dependency from any modes with possible mode veering.

Figure A3.

Example illustration of the load dependency from any modes with possible mode veering.

Appendix A.4

Figure A4.

Modal analysis in special test rig with substituted housing. (a) Modal hammer used to excite the structure on the shaft. (b) Position of the acceleration sensors on the inner structure of shafts and gear body.

Figure A4.

Modal analysis in special test rig with substituted housing. (a) Modal hammer used to excite the structure on the shaft. (b) Position of the acceleration sensors on the inner structure of shafts and gear body.

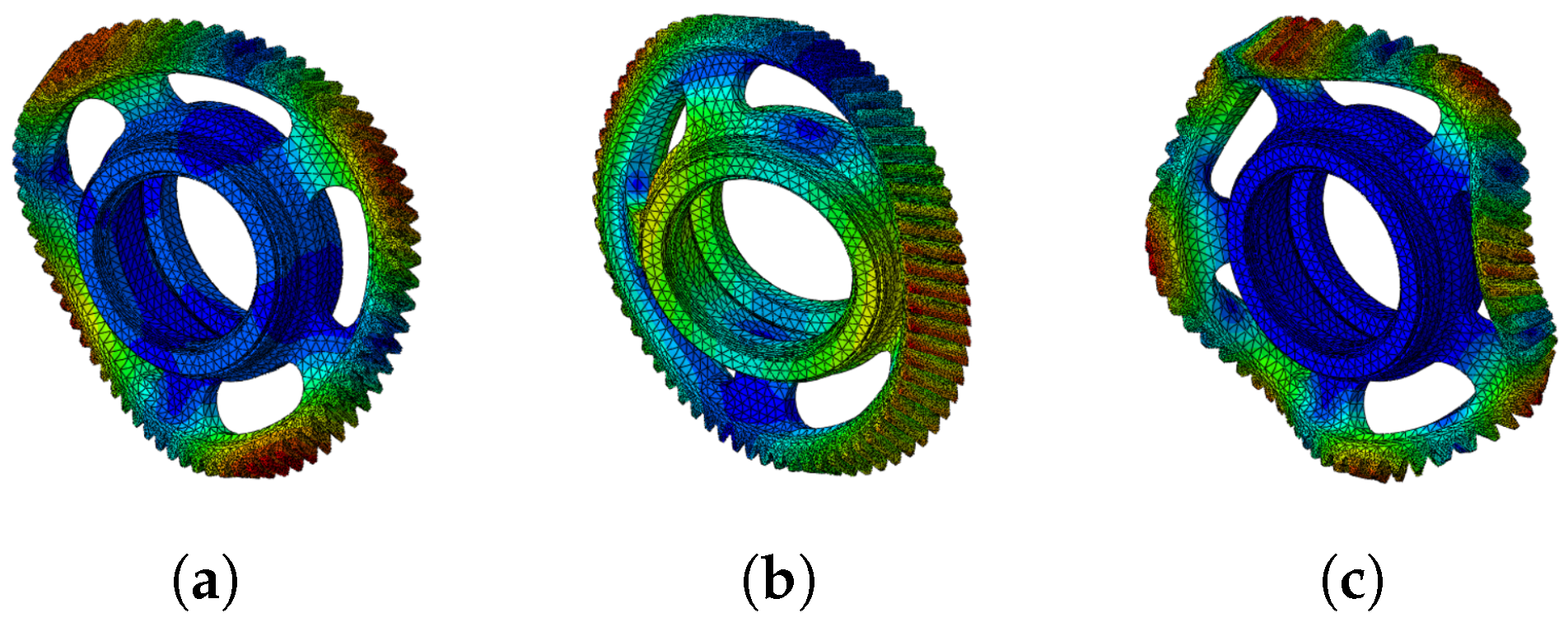

Appendix A.5

Figure A5.

Example illustration of modes’ shapes calculated in FEM, which are not present after modal reduction when the outer ring is coupled to an interface node. (a) . (b) . (c) .

Figure A5.

Example illustration of modes’ shapes calculated in FEM, which are not present after modal reduction when the outer ring is coupled to an interface node. (a) . (b) . (c) .

Appendix A.6

Figure A6.

Bearing stiffness configurations compared to axial quasi-statical measurement. The colourised simulation variants differ only in the used parameter magnitudes and serve as illustrative examples, demonstrating the sensitivity about the adjustable parameters in Bearing AT under consistent dimensions.

Figure A6.

Bearing stiffness configurations compared to axial quasi-statical measurement. The colourised simulation variants differ only in the used parameter magnitudes and serve as illustrative examples, demonstrating the sensitivity about the adjustable parameters in Bearing AT under consistent dimensions.

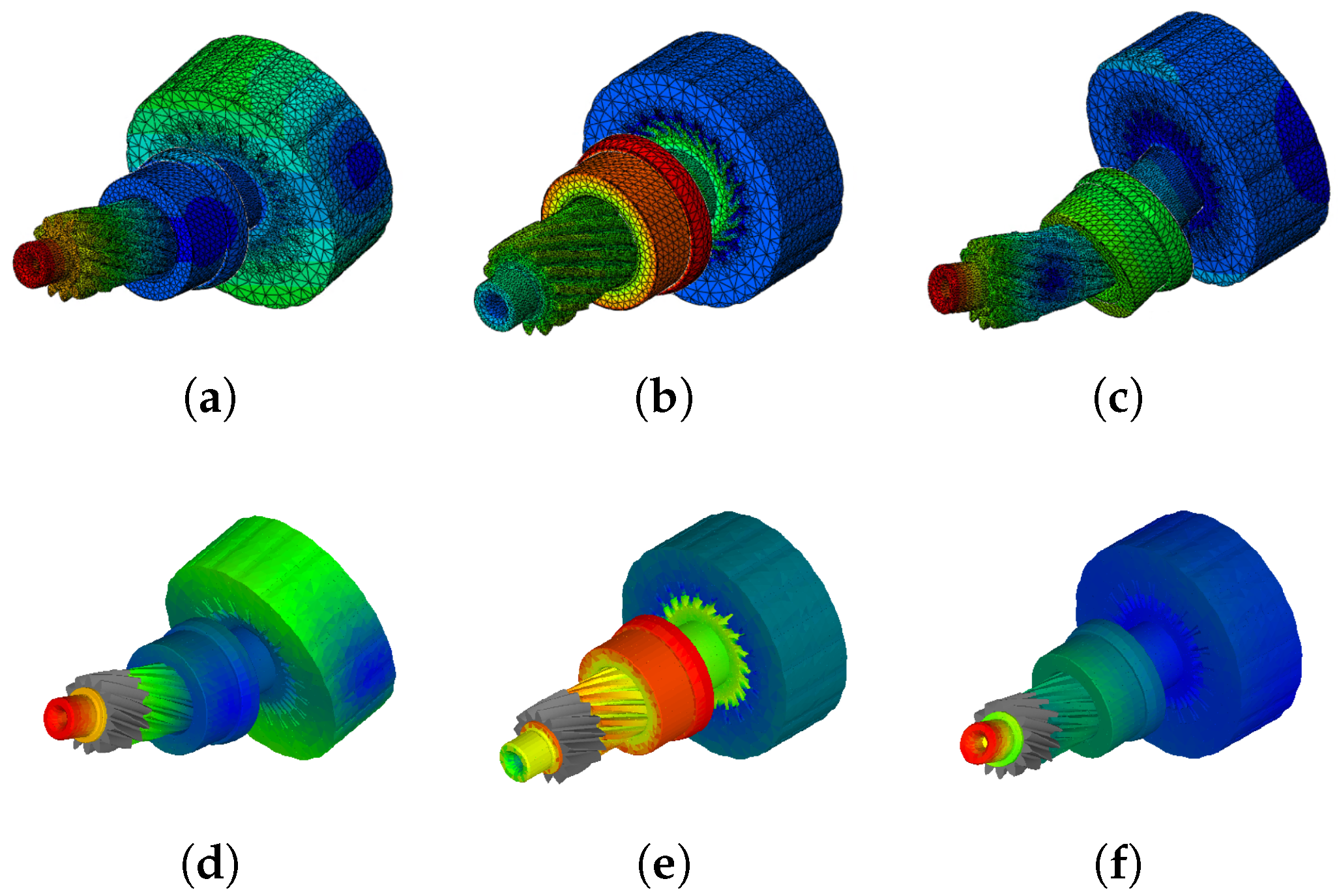

Appendix A.7

Figure A7.

Exemplary comparison of the rotor shaft assembly’s natural modes between the full FE model (a–c) and the flexible MBD model incorporating the reduced substructure (d–f). (a) First bending mode in the FE. (b) First torsional mode in the FE. (c) Second bending mode in the FE. (d) First bending mode in the MBD. (e) First torsional mode in the MBD. (f) Second bending mode in the MBD.

Figure A7.

Exemplary comparison of the rotor shaft assembly’s natural modes between the full FE model (a–c) and the flexible MBD model incorporating the reduced substructure (d–f). (a) First bending mode in the FE. (b) First torsional mode in the FE. (c) Second bending mode in the FE. (d) First bending mode in the MBD. (e) First torsional mode in the MBD. (f) Second bending mode in the MBD.

Appendix A.8

Figure A8.

Comparison of the spectra of the axial acceleration of the crankshaft for different model configurations in order to analyse the modelling influences.

Figure A8.

Comparison of the spectra of the axial acceleration of the crankshaft for different model configurations in order to analyse the modelling influences.

References

- Zweirad-Industrie-Verband (ZIV). Verteilung des Fahrradabsatzes in Deutschland nach Modellgruppen im Jahr 2024. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/6062/umfrage/anteil-der-fahrradmodelle-in-deutschland (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Statista. Elektrofahrräder Weltweit. 2025. Available online: https://de.statista.com/outlook/mmo/mikromobilitaet/fahrraeder/elektrofahrraeder/weltweit (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Bosch eBike Systems. Performance Line CX. 2025. Available online: https://www.bosch-ebike.com/us/products/performance-line-cx (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Amflow. PL Carbon. 2025. Available online: https://www.amflowbikes.com/de/pl-carbon (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Groß, I.; Reith, D. A Novel Approach to Predict the Structural Dynamics of E-Bike Drive Units by Innovative Integration of Elastic Multi-Body-Dynamics. Vehicles 2023, 5, 1227–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Groß, I.; Reith, D. Structural dynamic effects of the freewheel-clutch in e-bike drive units using a hybrid measurement and simulation approach. J. Vib. Control 2025, 10775463251344657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnejat, H.; Johns-Rahnejat, P.; Dolatabadi, N.; Rahmani, R. Multi-body dynamics in vehicle engineering. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part K J. Multi-Body Dyn. 2023, 238, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Tang, X.; Jia, T.; Duan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, L. Noise and vibration suppression in hybrid electric vehicles: State of the art and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4210; Safety Requirements for Bicycles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- EN 15194; Electrically Power Assisted Cycles. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- DIN 79010; Lastenfahrräder–Sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen und Prüfverfahren. Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Soori, M.; Arezoo, B.; Dastres, R. Virtual manufacturing in Industry 4.0: A review. Data Sci. Manag. 2024, 7, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, J.; Wyckaert, K.; Brughmans, M.; Kienert, M.; Van der Auweraer, H.; Donders, S.; Hadjit, R. Reducing Body Development Time by Integrating NVH and Durability Analysis from the Start. In Proceedings of the SAE 2006 World Congress & Exhibition, Detroit, MI, USA, 3–6 April 2006; SAE Technical Paper Series. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, M.; Drichel, P.; Schröder, M.; Berroth, J.; Jacobs, G.; Hameyer, K. Die Kopplung elektrotechnischer und strukturdynamischer Domänen zu einem NVH-Systemmodell eines elektrischen Antriebsstrangs. Elektrotechnik Informationstechnik 2020, 137, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonisoli, E.; Lisitano, D.; Dimauro, L. Detection of critical mode-shapes in flexible multibody system dynamics: The case study of a racing motorcycle. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 180, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gufler, V.; Wehrle, E.; Zwölfer, A. A review of flexible multibody dynamics for gradient-based design optimization. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2021, 53, 379–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, K.; Lechler, D.; Kraemer, P.; Gross, I.; Reith, D. Efficient parameter identification in nonlinear multi-body dynamics through frequency response and harmonic distortion analysis. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rill, G.; Schaeffer, T.; Borchsenius, F. Grundlagen und Computergerechte Methodik der Mehrkörpersimulation: Vertieft in Matlab-Beispielen, Übungen und Anwendungen; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.R.; Bampton, M.C.C. Coupling of substructures for dynamic analyses. AIAA J. 1968, 6, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lu, N.; Che, R. Dynamic analysis on rigid-flexible coupled multi-body system with a few flexible components. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Quality, Reliability, Risk, Maintenance, and Safety Engineering, Xi’an, China, 17–19 June 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabana, A.A. Flexible Multibody Dynamics: Review of Past and Recent Developments. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 1997, 1, 189–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Klerk, D.; Rixen, D.J.; Voormeeren, S.N. General Framework for Dynamic Substructuring: History, Review and Classification of Techniques. AIAA J. 2008, 46, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauchau, O.A. Flexible Multibody Dynamics; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. The Schur Complement and Its Applications; Methods and Algorithms; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Mevada, H.; Patel, D. Experimental Determination of Structural Damping of Different Materials. Procedia Eng. 2016, 144, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, F.; Schmidt, G.; Forrai, L. On the significance of antiresonance frequencies in experimental structural analysis. J. Sound Vib. 1999, 219, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akima, H. A New Method of Interpolation and Smooth Curve Fitting Based on Local Procedures. J. ACM 1970, 17, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linke, H. Stirnradverzahnung, 2, vollständig überarbeitete auflage ed.; Hanser eLibrary, Hanser Verlag: München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Siegl, G. Das Biegeschwingungsverhalten von Rotoren, die Mit Blechpaketen Besetzt Sind. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Fasihi, A.; Shahgholi, M.; Kudra, G.; GhandchiTehrani, M.; Awrejcewicz, J. The influence of rotor-stator contact on the nonlinear vibration of an asymmetrical rotor. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 27435–27457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chocholaty, B.; Liu, Y.; Marburg, S. Nonlinear dynamic behavior of a rotor-bearing system considering time-varying misalignment. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 284, 109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).