Abstract

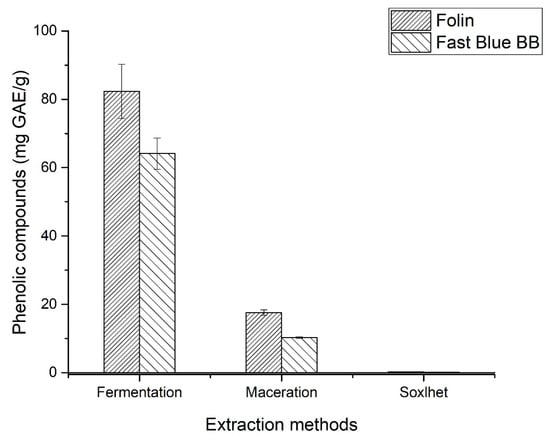

The increase in pineapple production has led to a significant accumulation of agro-industrial waste, underscoring the need for sustainable strategies for its utilization. The valorization of pineapple crowns presents an opportunity to produce value-added products rich in phenolic compounds, thereby reducing environmental impacts and offering accessible alternatives to small-scale producers. Among the methods for extracting phenolic compounds, maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and fermentation stand out, with the latter being considered a low-cost and more environmentally sustainable option. In this study, the objective was to compare three extraction methods (dynamic maceration, Soxhlet extraction, and fermentation) were compared to identify the most efficient method for recovering phenolic compounds from pineapple crowns. The results showed that fermentation yielded the highest total phenolic compounds of 82.3 mg GAE/g (Folin–Ciocalteu) and 64.1 mg GAE/g (Fast Blue BB), followed by maceration at 17.3 mg GAE/g (Folin–Ciocalteu) and 10.2 mg GAE/g (Fast Blue BB) and Soxhlet extraction at 2.1 mg GAE/g for both, with gallic, ferulic, and p-coumaric acids being particularly noteworthy in the fermented extract. The microorganism Bacillus sp. SMIA-2 played a significant role in the release and availability of these compounds, increasing the efficiency of the process. Thus, fermentation proves to be a sustainable and economically viable alternative for utilizing pineapple crowns, promoting the rational use of plant biomass and adding value to a low-cost, easily applicable agro-industrial byproduct.

Keywords:

byproduct; pineapple; phenolic compounds; maceration; Soxhlet; fermentation; Bacillus sp. SMIA2 1. Introduction

Pineapple (Ananas comosus), a member of the Bromeliaceae family, is one of the most widely consumed tropical fruits worldwide, notable for its sweet flavor, characteristic aroma, and recognized health benefits and phenolic compounds. In the Brazilian context, the crop has significant economic and social relevance due to the multiple production stages requiring a high labor level. The country ranks fourth globally in pineapple production, which contributes significantly to income and job creation, especially among small and medium-sized farmers [1]. The cultivars Pérola (also known as Pernambuco), Jupi (a variant of the cultivar Pérola), and Smooth Cayenne are among the most widely cultivated in Brazil, standing out for their agronomic and commercial characteristics. It is estimated that approximately 88% of national production is composed of the Pérola cultivars, with a conical shape, and Jupi, with a cylindrical shape; the remaining 12% corresponds to the Smooth Cayenne cultivar, with a predominantly cylindrical shape and recognized for its high yield and industrial quality [1,2]. Despite being widely valued for its fresh consumption and industrial processing, the pineapple plant generates significant quantities of byproducts during the harvesting and processing stages, which, in most cases, are not reused properly, accumulating as waste that can represent environmental liabilities [3]. Pineapple processing generates, on average, 60% waste, of which approximately 29% corresponds to the peel, 9% to the core, 2% to the stem, and 2% to the crown. It is estimated that about 76.4 million tons of leaf waste are generated annually. These byproducts, frequently burned or disposed of in landfills, pose a potential environmental problem, as they increase the chemical and biological oxygen demand. When incinerated, they contribute to the emission of greenhouse gases. However, such waste has high potential for obtaining value-added products, as it is a source of enzymes, organic acids, antioxidant compounds, and other nutrients of industrial interest. Currently, pineapple waste is used in composting and the production of bioethanol and biogas, as well as in the extraction of dietary fibers and nanocellulose [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The bark, for example, has been used in the formulation of animal feed, in the generation of bioenergy, in the production of bio-plastics and prebiotic flours; the pith in sweets, beverages and cosmetic products; the stem in obtaining bioactive molecules; the leaves in the production of fibers; and the crown as material for composting [11,12,13].

In the scientific literature, there is growing interest in the study and valorization of these solid byproducts, commonly called agro-industrial residues, which stand out as sources of various bioactive compounds and technological interest. These residues have a diverse composition, including dietary fiber, pectin, essential oils, enzymes, and different organic acids, which have potential applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology sectors. Therefore, the proper exploitation of these components can add value to materials that are usually discarded, contributing to the reduction in environmental impacts and the development of sustainable alternatives in the agricultural sector [14].

Pineapple is a fruit rich in carbohydrates and low in sodium and fat, contributing to a balanced and healthy diet. It is also a significant source of phytochemicals, such as gallic acid, ferulic acid, catechin, and epicatechin, which give it high nutritional value. The chemical composition of the pineapple crown also contains several bioactive compounds, including phenolic compounds [15,16,17]. These compounds, derived from the secondary metabolism of plants, play an essential role in food quality, providing color and flavor, serving as a substrate for enzymatic browning, and protecting vegetables against free radicals generated during photosynthesis and viral and bacterial infections, among other functions [17]. Furthermore, they are known for their antioxidant potential, with beneficial effects in preventing cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, as well as reducing inflammatory processes [18]. However, as they are sensitive to heat, light, and oxygen, extracting these compounds requires appropriate methods that guarantee good yield and preserve their functional properties. These molecules are extracted using methodologies such as dynamic maceration and Soxhlet extraction, which have several disadvantages compared to more recent techniques, including the use of organic and toxic solvents, high energy consumption, solvent evaporation, and inadequate waste disposal [19,20,21,22,23]. Dynamic maceration and Soxhlet extraction are distinct processes in terms of efficiency and impact on food quality. However, both are widely used to recover phenolic compounds from plant matrices. In dynamic maceration, plant material is immersed in an organic solvent, usually under constant agitation and at room temperature, gradually allowing soluble compounds to migrate into the solvent over time. This method is relatively simple and low-cost, but the reduced solvent penetration into plant tissues may limit its efficiency [24].

In contrast, Soxhlet extraction involves the continuous circulation of heated solvent through the plant material, promoting a more intense and efficient extraction of phenolic compounds. Controlled heating accelerates the diffusion and solubilization of metabolites in plant cells, resulting in higher yields than conventional maceration. Despite being more efficient, the Soxhlet method may have disadvantages related to the prolonged use of solvents and thermal exposure, which may compromise heat-sensitive compounds. Therefore, the choice of extraction method must consider the balance between yield, preservation of compound quality, and process sustainability, according to the specific objective of the application [25,26,27].

Extraction methods aligned with green chemistry principles have been explored in response to these challenges, aiming to reduce energy consumption, reduce solvent use, and promote sustainability [28,29]. In this context, fermentation extraction has emerged as an efficient strategy for obtaining phenolic compounds from plants and agro-industrial waste. During fermentation, microorganisms degrade fibrous components in plant cell walls, breaking the covalent bonds between polyphenols and other substances, thereby leading to the release of associated phenolic compounds that are bound to polysaccharides and thus making them more available for extraction [30,31,32]. Therefore, extraction by fermentation constitutes a highly efficient method, since the enzymes secreted by the microorganism can degrade the plant cell wall and release the bound phenolic compounds, significantly increasing their bioavailability [33,34,35]. The use of microorganisms in this process has become a promising strategy for valorizing agro-industrial waste, converting previously discarded byproducts into value-added materials, with potential applications in the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and biotechnology industries [36].

However, the choice of microorganism plays a crucial role in extraction efficiency, as different species and strains have distinct enzymatic capacities that directly influence the release of bioactive compounds. In this context, the strain Bacillus licheniformis SMIA2, isolated in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2001, was categorized as belonging to group 5 of thermophilic Bacillus. This strain has stood out as an important alternative for the fermentation of agricultural waste, due to its efficiency in producing hydrolytic enzymes and its ability to act in processes of valorization of vegetable byproducts [37,38].

Thus, considering the biotechnological potential of microorganisms and the need for full utilization of pineapple, it becomes relevant to explore the use of its residues beyond the pulp. The crown, in particular, presents itself as an abundant, renewable, and biodegradable source of fibers and bioactive compounds [39,40]. In this context, the present study aimed to compare three extraction methods to determine the most efficient in recovering phenolic compounds from pineapple crowns.

2. Materials and Methods

The plant material used in this study corresponded to pineapple crowns (Ananas comosus), belonging to the Pérola cultivar, widely cultivated and commercialized in Brazil due to its sensory characteristics and socioeconomic relevance. The Plant Science Laboratory of the Northern Fluminense State University Darcy Ribeiro (UENF) provided the samples, which guaranteed the origin and standardization of the material used in the tests. After collection, the crowns were sent to the experimental stage, conducted in the Food Technology Laboratory (FTL), belonging to the same institution, with the appropriate infrastructure to carry out the proposed analyses.

The microorganism was Bacillus licheniformis SMIA2, which was isolated from a soil sample collected in Campos dos Goytacazes city, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The genome of Bacillus licheniformis SMIA-2 was previously sequenced at the Molecular Biology Service Unit of the Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Canada. The whole-genome project has been deposited in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession number JAACZZ000000000 [7].

2.1. Drying the Pineapple Crown

The pineapple crowns were initially washed under running water to remove surface impurities and then immersed in distilled water for two minutes to ensure complete cleaning. Subsequently, the leaves were dried with absorbent paper and placed in trays of previously known mass. The samples were placed in a forced-air oven at 60 °C to reduce moisture, where they remained until they reached a constant weight, which occurred after approximately 48 h, resulting in a final moisture content of 12%. Then, the dried material was ground in a mill and sieved to obtain particles with a granulometry between 1 mm and 2 mm, resulting in a homogeneous flour known as pineapple crown residue flour (PFR) [39,40,41].

2.2. Extraction Methods of Phenolic Compounds

2.2.1. Dynamic Maceration Extraction

Dynamic maceration extraction was performed according to Zhou et al. [42]. 30 g of sample and 150 mL of methanol were added to an Erlenmeyer flask, which remained in the shaker for 12 h at 35 °C and 180 rpm. Subsequently, the mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 5000 rpm. The supernatant was collected, frozen, and lyophilized (L101 Liotop, Liobras, São Carlos, Brazil) at −54 °C with a pressure between 250 and 170 µHg.

2.2.2. Soxhlet Extraction

The Soxhlet extraction was performed according to Oliveira et al. [39]. The extraction cartridge was prepared with 20 g of FCA for reflux extraction. The first step was performed with 150 mL of hexane solvent at 80 °C for 4 h to remove nonpolar compounds, and then, using the same sample, 150 mL of methanol at 60 °C for 4 h. The extracts were placed in a rotary evaporator and subsequently taken for lyophilization (L101 Liotop) at −54 °C with a pressure between 250 and 170 µHg.

2.2.3. Extraction by Submerged Fermentation

Extraction by submerged fermentation was carried out growing the non-pathogenic bacteria Bacillus licheniformis SMIA2 in the culture medium consisting (g·L−1): KCl—0.3, MgSO4—0.5, K2HPO4—0.87, CaCl2—0.29, ZnO—2.03 × 10−3, FeCl3.6H2O—2.7 × 10−2, MnCl2.4H2O—1.0 × 10−2, CuCl2.2H2O—8.5 × 10−4, CoCl2.6H2O—2.4 × 10−3, NiCl3.6H2O—2.5 × 10−4, H3BO3—3.0 × 10−4, commercial corn steep liquor (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA)—3.0 as a nitrogen source and dry flour from the pineapple crown −5.0. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.2 with 1.0 M NaOH, and the medium was sterilized by autoclaving at 121 °C for 15 min. The medium (50 mL in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks) was inoculated with 1 mL of a standard overnight culture (initial number of cells 104) and incubated at 50 °C in an orbital shaker (Thermo Forma, Marietta, OH, USA) operated at 150 rpm. After 240 h, the flasks were withdrawn and the contents were then centrifuged (HERMLEZ 382K, Wehingen, Germany) at 15,500× g for 15 min, at 4 °C. The fermented extract was frozen and lyophilized (L101 Liotop).

2.2.4. Enzyme Assay

Avicelase (exo-1,4-β-D-glucanase or cellulose 1,4-β-cellobiosidase—EC 3.2.1.91), carboxymethycellulase (endo-(1,4)-β-d-glucanase—EC 3.2.1.4), and polygalacturonase (EC 3.2.1.15) were assayed by measuring the reducing sugar released from avicel (PH-101, Sigma-cell 20), carboxymethylcellulose sodium salt (Sigma), and apple pectin (Sigma), respectively. The reaction mixture, containing 0.5 mL of substrate solution (1%, w/v) prepared in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5, and 0.5 mL of enzyme solution, was incubated at 70 °C. After 10 min of reaction, 1 mL of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent [39] was added and boiled in a water bath for 5 min. The resulting samples were cooled to room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. When the activity was tested on Avicel as a substrate, the assay tubes were agitated during the assay to keep the substrate suspended. One unit (U) of activity toward the substrates mentioned above was defined as 1 μmole of glucose (avicelase and CMCase) and galacturonic (polygalacturonase) equivalent released per minute under the above assay conditions, by using a standard curve. Appropriate controls were conducted in parallel with all assays. An enzyme blank containing 0.5 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 0.5 mL of 1% (w/v) substrate solution was run. To exclude the background of reducing sugars found in the enzyme supernatant from the results, a substrate blank was also run containing 0.5 mL of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer and 0.5 mL of enzyme solution [43]. The absorbance of the enzyme blank sets and the substrate blank was subtracted from the absorbance of the activity assay. All samples were run in triplicate, while the blanks were run in duplicate.

2.3. Analysis of Total Phenolic Compounds

2.3.1. Analysis of Phenols

The Folin–Ciocalteu method was carried out according to Singleton [44], which consisted of preparing a 1.0 mg/mL solution of the sample in methanol solvent. After preparing the sample solution, a 30 µL aliquot was transferred to a plate containing wells. Along with the solution, 50 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was added to the same well, and after 10 min, 100 µL of sodium carbonate was added. The samples were left on an orbital shaker (Tecnal TE 420, Tecnal, Piracicaba, Brasil) for 1 h under agitation at 70 rpm, and the reading was taken at a wavelength of 760 nm on a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A gallic acid curve was created to quantify phenols, and the phenol concentration was expressed in mg GAE/g of sample.

2.3.2. Phenol Analysis by the FastBlue BB Method

Phenol analysis by the FastBlue BB method was performed according to Ravindranath et al. [45], which consisted of preparing a 1.0 mg/mL sample solution in methanol solvent and a 0.1 mg/mL solution of the FastBlue BB reagent. After preparing the solutions, a 40 µL aliquot of the sample solution was transferred to a plate containing wells. Together with the solution, 160 µL of ultrapure water and 20 µL of the FastBlue BB solution were added to the same well. After 1 min, 20 µL of 5% NaOH was added. The samples remained for 1.5 h in the orbital shaker (Tecnal TE 420) under agitation at 70 rpm. After this time, the reading was taken at a wavelength of 420 nm in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. A gallic acid curve was created to quantify phenols, and the phenol concentration was expressed in mg GAE/g of sample.

2.4. Evaluation of the Chemical Profile of Methanolic Extracts by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

A Shimadzu HPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a refractive index detector (RID-10A) and a C18 chromatographic column (phenosphere column 5UM ODS(2) 250 × 4.6 mm) was used, with the column temperature maintained at 35 °C. The mobile phase was acidified water at pH = 3.2 and acetonitrile with a 1 mL/min flow rate. The samples were prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/mL of mobile phase (500 µL of acidified water and 500 µL of acetonitrile). Gallic acid, ferulic acid, and p-coumaric acid standards were used to identify phenolic compounds.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data were subjected to statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 4 software. The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s test, adopting a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of Total Phenolic Compounds

The concentrations of total phenolic compounds, determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu and Fast Blue BB methods, varied significantly depending on the analytical methodology employed. As shown in Figure 1, the dynamic maceration and Soxhlet extraction methods showed no significant differences. The maceration method quantified 17.3 mg GAE/g (Folin–Ciocalteu) and 10.2 mg GAE/g (Fast Blue BB). For Soxhlet, the values were 2.1 mg GAE/g for both. This discrepancy between the values can be attributed to the differences in sensitivity and selectivity of the reagents used.

Figure 1.

Concentration of phenolic compounds in pineapple crown using two analysis methods. The samples are significantly different according to Tukey’s test (p ≤ 0.05).

In the extraction performed by submerged fermentation with B. licheniformis SMIA2, 82.3 mg GAE/g of sample were quantified by the Folin–Ciocalteu method. In comparison, the Fast Blue BB method indicated 64.1 mg GAE/g. Compared to the study of Zang et al. [30], who used Bacillus subtilis in submerged fermentation to extract phenolic compounds from corn flour, the results obtained with B. licheniformis SMIA2 in this study demonstrated superior yield.

Bacillus licheniformis SMIA-2 produced hydrolytic enzymes such as avicelase (avicel-hydrolyzing enzymes), CMCase (carboxymethylcellulose-hydrolyzing enzymes), and polygalacturonase (enzymes involved in the degradation of pectic substances) (Table 1). Thus, the SMIA-2 has the enzyme systems for pineapple crown degradation.

Table 1.

Enzymatic activity of Bacillus licheniformis SMIA-2 from the utilization of carbohydrates from pineapple crown and concentration of phenolic compounds.

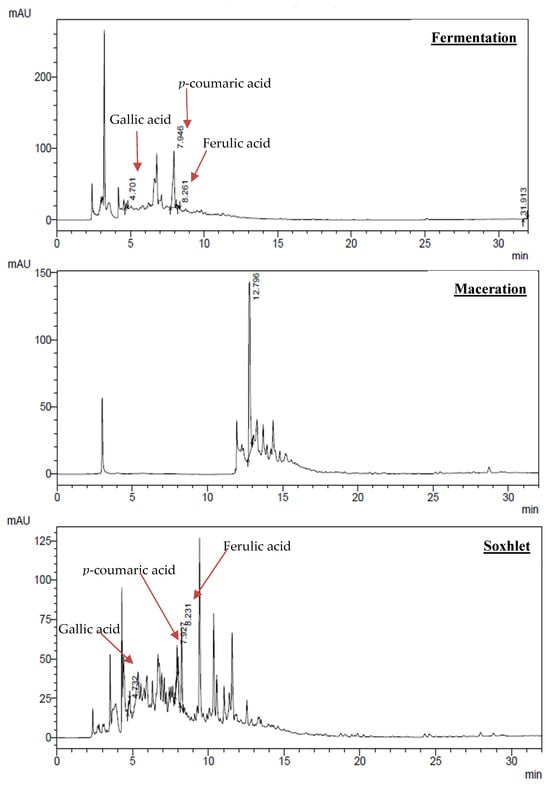

3.2. Chemical Profiling by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The chromatograms (Figure 2) obtained for the samples extracted by submerged fermentation and the Soxhlet method exhibited peaks with retention times compatible with the standards of gallic acid, ferulic acid, and p-coumaric acid, confirming the presence of these phenolic compounds in the analyzed samples. These results agree with the literature, which indicates that p-coumaric and ferulic acids are predominant in the pineapple crown and other compounds derived from these acids [30].

Figure 2.

Chemical profile of the three extraction methods.

4. Discussion

The Folin–Ciocalteu method is based on electron transfer and the measurement of the reducing capacity of the sample; however, it is sensitive to interference from ascorbic acid, sugars, amines, and other antioxidants, which can result in overestimation of the phenolic compound content. This reagent exhibits low selectivity, reacting not only with phenols but also with various reducing substances present in the sample matrix. Furthermore, experimental factors such as pH, temperature, order of reagent addition, and reaction time can directly influence the method’s accuracy. In contrast, the Fast Blue BB reagent demonstrates greater selectivity for phenolic compounds, which explains the lower concentrations observed, since its detection occurs by direct reaction with these compounds [46,47,48]. These results are consistent with those of Rudiana et al. [49], who observed no significant differences in phenolic compound levels and antioxidant activity between maceration and Soxhlet extractions of fruit tree samples.

The temperature during the extraction process directly influences yield, as high temperatures can favor the release of phenolic compounds and promote their thermal degradation. Phenolic compounds, such as phenolic acids, are particularly heat-sensitive and can participate in Maillard reactions, forming new products. High temperatures can break the bonds between lignin and phenolic acids, releasing previously bound phenolic acids or generating new phenolic acids. However, temperatures above 80 °C can cause significant degradation of these compounds, resulting in low yields, as observed in the Soxhlet extraction of pineapple crown flour. Furthermore, the maceration and Soxhlet extraction methods are performed under conditions without strict light and oxygen control, factors that can contribute to the oxidative degradation of the extracted phenolic compounds. This fact partly explains the low levels obtained for pineapple crown using these methods [50,51].

On extraction by submerged fermentation, Zang et al. [30] observed that B. subtilis promoted cell wall degradation and increased the release of bound phenols; their values were lower than those obtained with pineapple crown flour treated with B. licheniformis SMIA2. This indicates that the SMIA-2 has greater enzymatic capacity or efficiency in converting insoluble bound phenols into soluble forms, consolidating it as the most efficient extraction method evaluated in this study. However, the literature reports several green extraction methods that have shown promising results in recovering phenolic compounds from different types of waste. For example, in tomato pomace residue, total phenolic compound contents ranging from 4.6 to 22.8 mg GAE/g were obtained through extraction with ethanol. Similarly, residues from vegetable oil processing showed concentrations between 1.5 and 74.7 mg GAE/g when subjected to extraction using methanol. Furthermore, several agro-industrial residues, such as corn husks, peanut shells, coffee husks, among others, are widely recognized as relevant sources of phenolic compounds, among which gallic acid, ferulic acid, catechin, quercetin, kaempferol, rutin, and epicatechin stand out [52,53,54].

B. licheniformis SMIA-2 produced avicelase, CMCase and polygalacturonases, which are enzymes involved in plant material degradation. Carbohydrate hydrolyzing enzymes such as pectinases, cellulases, amylases, hemicellulases, and xylanases disrupt the plant cell wall matrix, breaking the covalent bonds between polyphenols and other substances, facilitating the liberation of phenolic compounds, that are bound to polysaccharides [55,56]. Some microorganisms express free enzymes, while others produce a large extracellular multienzyme complex, such as the cellulosome. The entire SMIA-2 genome was recently sequenced, and relevant gene clusters, including six amylase genes, 13 loci for xylose metabolism, 55 protein degradation-associated loci, and three cellulolytic enzyme loci under a putative cellulosome complex, were identified [57]. Bacillus licheniformis SMIA2 has characteristics that make it especially advantageous for the extraction of phenolic compounds from plant material. It is an easy-to-cultivate microorganism, with a rapid growth rate and low operating costs, which contribute positively to both the economic viability and environmental sustainability of the process. During extraction, Bacillus SMIA2 secretes enzymes capable of degrading the plant matrix, releasing the bound phenolic compounds in a single efficient process. Furthermore, this microorganism has the metabolic capacity to generate new phenolic compounds through its secondary metabolism, increasing the bioactive value of the extracted material [58].

The chromatographic profile obtained for dynamic maceration extraction showed a peak with a retention time longer than the standards used, suggesting the presence of phenolic compounds different from those detected in fermentation and Soxhlet extractions. This difference can be explained by the fact that compounds with lower polarity and higher molar mass present longer retention times by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), unlike phenolic acids such as ferulic and p-coumaric acids, which have lower molar mass, higher polarity, and, consequently, shorter retention times [59]. The chemical profile obtained by the three extraction methods revealed the presence of possible phenolic substances, since the observed peaks presented wavelengths compatible with compounds of this group (250–350 nm). Although dynamic maceration did not exhibit the same phenolic acids identified in Soxhlet and fermentation extractions, the analysis of ultraviolet absorption spectra suggests the presence of other phenolic acids, since a characteristic absorption band of these compounds was observed. Furthermore, the presence of spectra with two absorption bands indicates the possible occurrence of flavonoids in the extracts obtained [60].

Conventional extraction methods have limitations in the recovery of phenolic compounds since many of these metabolites are linked and conjugated to plant cell wall components through ether, ester, or glycosidic bonds. Although it is possible to employ acidic or basic hydrolysis in these methods to release the bound phenolic compounds, such procedures can result in the degradation of hydroxycinnamic acids, such as ferulic and p-coumaric acid, compromising the yield and integrity of the compounds [61]. The identified phenolic compounds belong mainly to the classes of hydroxybenzoic acids, represented by gallic acid, and hydroxycinnamic acids, such as ferulic acid and p-coumaric acid. Gallic and ferulic acids are considered especially important due to their bioactive properties, including antioxidant, anticancer, antiviral, antimutagenic, and antiparasitic potential. Furthermore, gallic acid is used to synthesize compounds such as the antibacterial agent trimethoprim and the antioxidant propyl gallate. In contrast, ferulic acid is used in the food industry, present in cereals, beverages such as coffee and beer, and serves as a precursor in the synthesis of vanillin, widely used industrially [62].

The three hydroxyls present in the structure of gallic acid allow it to act through the hydrogen atom transfer mechanism, donating them to free radicals and promoting their neutralization. This antioxidant capacity results from the low enthalpy of dissociation of the O–H bond characteristic of gallic acid, which facilitates the transfer of hydrogens to reactive species [63,64,65].

Ferulic acid, in turn, has a hydroxyl group linked to the aromatic ring capable of donating hydrogen to free radicals, forming a resonance-stabilized phenoxy radical. This structural stabilization is one of the main reasons for the high antioxidant potential of ferulic acid. Furthermore, ferulic acid may exert an additional antioxidant effect by inhibiting enzymes responsible for generating free radicals, enhancing its protective action against oxidative processes [66,67,68].

Phenolic acids are more hydrophilic than flavonoids and elute more rapidly in reversed-phase systems, such as the C18 columns used in this study. In gradient elution systems, phenolic acids are generally detected before flavonoids due to differences in their structural properties and polarity. Thus, the chemical structure of the compounds and their substituents directly influences retention time, allowing for proper separation and identification during chromatographic analysis [69,70].

The presence of phenolic compounds in plant materials is of great importance, since these compounds act as antioxidants, being able to donate hydrogens from their hydroxyls to prevent the formation of free radicals and the oxidation of biomolecules. Furthermore, they promote the stabilization and delocalization of unpaired electrons within their aromatic ring, increasing their ability to neutralize reactive species [71,72]. In the case of p-coumaric acid, its antioxidant potential is attributed to the presence of a hydroxyl group in position 4 of the aromatic ring, which donates the hydrogen atom to stabilize the radical formed. In addition to this action, p-coumaric acid can inhibit lipid peroxidation, protecting important biological structures, such as cell membranes, against oxidative damage [73,74,75]. The quantification of phenolic compounds and the identification of phenolic acids in pineapple crowns highlight the potential of this agro-industrial residue as a valuable source of bioactive biomolecules. These results highlight the potential of developing byproducts from pineapple crowns, with applications in the pharmaceutical, food, and cosmetic industries, among others, thereby contributing to the sustainable use of waste and enhancing the value of the pineapple production chain [76,77,78].

5. Conclusions

The results obtained in this study show that conventional methods of extracting phenolic compounds are less efficient compared to submerged fermentation. This difference is related to the inability of traditional techniques to promote the release of phenolic compounds bound to the plant cell wall, which restricts their availability. In contrast, submerged fermentation demonstrated superior performance since the Bacillus SMIA2 strain produced enzymes capable of degrading the structural components of the cell wall, promoting greater release of these compounds. In addition to the efficiency in yield, the sustainable nature of the process stands out, as submerged fermentation eliminates the use of organic solvents, often used in traditional methods. Another relevant aspect is the microbiological safety of B. licheniformis SMIA2, which is not pathogenic, expanding its potential for application in the food sector.

At the same time, considering the continuous increase in pineapple production and, consequently, the accumulation of waste in the agro-industrial sector, the importance of strategies to enhance the value of these byproducts becomes evident, in line with the UN’s 12th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG), which advocates “responsible consumption and production”. In this sense, the use of pineapple crowns as a source of bioactive compounds proves to be a strategic alternative for reducing environmental impacts and, at the same time, generating low-cost, high-value-added products. This aspect takes on particular relevance in the North Fluminense region, one of the largest pineapple-producing centers in the state of Rio de Janeiro, where accessible technological solutions can directly benefit small rural producers and family farmers.

Thus, it is concluded that submerged fermentation with B. licheniformis SMIA2 not only constitutes an efficient and sustainable method for the extraction of phenolic compounds from the pineapple crown, but also represents an approach with great practical applicability, aligned with the principles of bioeconomy and circular economy, contributing to the valorization of agro-industrial waste and the promotion of cleaner and more sustainable processes in the agricultural sector.

Author Contributions

Methodology, T.T.M.d.S., A.L.P.B.C., S.M.d.F.P., E.R.M.d.O. and T.C.d.S.; Software, E.R.M.d.O.; Formal analysis, T.T.M.d.S.; Writing—original draft, T.T.M.d.S. and M.L.L.M.; Writing—review and editing, H.D.V. and D.B.d.O.; Supervision, D.B.d.O.; Project administration, D.B.d.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Northern Fluminense State University Darcy Ribeiro (UENF), grant number 31033016001P2 and the APC was funded by Henrique Duarte Vieira.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UENF | Northern Fluminense State University Darcy Ribeiro |

| FTL | Food Technology Laboratory |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| PFR | Pineapple crown residue flour |

References

- Embrapa-Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (2021) Technical Bulletin; Embrapa-Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation: Brasília, Brazil, 2021; 12p.

- Matos, A.P. Abacaxi: O Produtor Pergunta, a Embrapa Responde, 2nd ed.; Associação Brasileira de Milho e Sorgo: Sete Lagoas, Brazil; Inovações, Milho e Sorgo: Bento Gonçalves, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.M.; Hashim, N.; Abd Aziz, S.; Lasekan, O. Pineapple (Ananas comosus): A comprehensive review of nutritional values, volatile compounds, health benefits, and potential food products. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardawati, E.; Putri, S.; Fitriana, H.; Nurliasari, D.; Rahmah, D.R.; Maulana, I.; Dewantoro, A.; Hermiati, E.; Balia, R. Aplicação do conceito de biorrefinaria à produção de bromelaína, etanol e xilitol a partir de resíduos de abacaxi. Fermentation 2023, 9, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, A.; Hamzah, M.; Man, C.; Jamali, N.; Siajam, S.; Ismail, M. Atualizações recentes sobre a conversão de resíduos de abacaxi (Ananas comosus) em produtos de valor agregado, perspectivas futuras e desafios. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-González, E.; Giraldi-Díaz, M.; De Medina-Salas, L.; Sánchez-Castillo, M. Pré-Compostagem e Vermicompostagem de Abacaxi (Ananas comosus) e Resíduos Vegetais. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, S.P.C.; Rosana, A.R.R.; de Souza, A.N.; Chiorean, S.; Martins, M.L.L.; Vederas, J.C. Draft genome sequence of the thermophilic bacterium Bacillus licheniformis SMIA-2, an antimicrobial-and thermostable enzyme-producing isolate from Brazilian soil. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020, 9, e00106-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, A.N.D.; Martins, M.L.L. Isolation, properties and kinetics of growth of a thermophilic Bacillus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2001, 32, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.B.; Gentil, N.O.; Ladeira, S.A.; Martins, M.L.L. Addendum to Issue 1-ENZITEC 2012 Cheese whey and passion fruit rind flour as substrates for protease production by Bacillus sp. SMIA-2 strain isolated from Brazilian soil. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2014, 32, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.E.; Thai, Q.B.; Le, D.K.; Luu, T.P.; Nguyen, P.T.; Do, N.H.; Duong, H.M. Functionalized pineapple aerogels for ethylene gas adsorption and nickel (II) ion removal applications. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, T.; Nguyen, D.T.C.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Nguyen, D.H.; Alhassan, M.; Jalil, A.A.; Lee, T. A critical review on pineapple (Ananas comosus) wastes for water treatment, challenges and future prospects towards circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 158817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretto, L.C.D.O.; Moreira, J.D.J.D.S.; Santos, J.A.B.D.; Narendra, N.; Santos, R.A.R.D. Characterization and extraction of volatile compounds from pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merril) processing residues. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Kumar, V.; Singh, K.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Pineapple (Ananas cosmosus) product processing: A review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 4642–4652. [Google Scholar]

- Roda, A.; Lambri, M. Food uses of pineapple waste and byproducts: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chow, C.; Fang, Y. Preparation and physicochemical properties of fiber-rich fraction from pineapple peels as a potential ingredient. J. Food Drug Anal. 2011, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seenak, P.; Kumphune, S.; Malakul, W.; Chotima, R.; Nernpermpisooth, N. Pineapple consumption reduced cardiac oxidative stress and inflammation in high cholesterol diet-fed rats. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadh, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Chawla, P.; Duhan, J.S. Fermentation: A boon for production of bioactive compounds by processing of food industries wastes (byproducts). Molecules 2018, 23, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoddami, A.; Wilkes, M.; Roberts, T. Techniques for Analysis of Plant Phenolic Compounds. Molecules 2013, 18, 2328–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhao, W.; Yang, Z.; Subbiah, V.; Suleria, H.A. Extraction and characterization of phenolic compounds and their potential antioxidant activities. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 81112–81129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong-Cong, X.U.; Bing, W.A.N.G.; Yi- Qiong, P.U.; Jian-Sheng, T.A.O. Advances in extraction and analysis of phenolic compounds from plant materials. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 15, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanti, I.; Pratiwi, R.; Rosandi, Y.; Hasanah, A.N. Separation methods of phenolic compounds from plant extract as antioxidant agents candidate. Plants 2024, 13, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama-Muñoz, A.; Contreras, M.D.M. Extraction systems and analytical Techniques for food phenolics compounds: A review. Foods 2022, 11, 3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, U.; Viegas, C.; Duarte, M.P.; Maurício, E.M.; Nobre, C.; Correia, R.; Gonçalves, M. Maceration of Waste Cork in Binary Hydrophilic Solvents for the Production of Functional Extracts. Environments 2023, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Bhushan, B. An overview of the recent trends on the waste valorization techniques for food waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Martín, E.; Forbes-Hernández, T.; Romero, A.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. Influence of the extraction method on the recovery of bioactive phenolic compounds from the food industry byproducts. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 131918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Los Ángeles Fernández, M.; Espino, M.; Gomez, F.J.; Silva, M.F. Novel approaches mediated by tailor-made green solvents for the extraction of phenolic compounds from agro-food industrial byproducts. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Adhikari, B.; Fang, Z. Fermentation transforms the phenolic profiles and bioactivities of plant-based foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 49, 107763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.; Silva, C.; Salgado, J.M.; Belo, I. Simultaneous production of lignocellulolytic enzymes and extraction of antioxidant compounds by solid-state fermentation of agro-industrial Wastes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Gu, T.; Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Gao, M. The Release of Bound Phenolics to Enhance the Antioxidant Activity of Cornmeal by Liquid Fermentation with Bacillus subtilis. Foods 2025, 14, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, T.B.; Chakraborty, S.; Jain, K.K.; Sharma, A.; Kuhad, R.C. Antioxidant phenolics and their microbial production by submerged and solid state fermentation process: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulsunoglu-Konuskan, Z.; e Kilic-Akyilmaz, M. Microbial bioconversion of phenolic compounds in agro-industrial wastes: A review of mechanisms and effective factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 6901–6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira Junior, J.V.; Teixeira, C.B.; e Macedo, G.A. Biotransformation and bioconversion of phenolic compounds obtainment: An overview. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, T.A.; Singh, N.J.; Shadangi, K.P.; Srivastava, R.K.; Singh, A.K.; Vivekanand, V. Sustainable utilization of pineapple waste for production of bioenergy, biochemicals and value-added products: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, R.K.; Gupta, V.K. Recent progress and future perspectives for zero agriculture waste Technologies: Pineapple waste as a case study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukruansuwan, V.; Napathorn, S.C. Use of agro-industrial residue from the canned pineapple industry for polyhydroxybutyrate production by Cupriavidus necator strain A-04. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Singh, B. Pineapple byproducts utilization: Progress towards the circular economy. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, K.S.; Spinacé, M.A. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from pineapple crown waste and their potential uses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.C.; Valentim, I.B.; Silva, C.A.; Bechara, E.J.H.; de Barros, M.P.; Mano, C.M.; Goulart, M.O.F. Total phenolic content and free radical scavenging activities of methanolic extract powders of tropical fruit residues. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenssen, P.H.; Peek, K.; Morgan, H.W. Effect of culture conditions on the production of an extracellular proteinase by Thermus sp. Rt41A. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1994, 41, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, E. Cellulases from Bacillus sp. SMIA-2: Drying and Use for Formulation Development Ecological Cleaning. Ph.D. Thesis, University State of Northern Fluminense Darcy Ribeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Li, J.; Agar, O.T.; Barrow, C.; Dunshea, F.; Suleria, H.A.R. Screening and characterization of phenolic compounds by LC-ESI-QTOF-MS/MS and their antioxidant potentials in papaya fruit and their byproduct activities. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugars. Analytical 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin ciocalteu reagent. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranath, V.; Singh, J.; Jayaprakasha, G.K.; Patil, B.S. Optimization of Extraction Solvent and Fast Blue BB Assay for Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant Phenolics from Cucumis melo L. Plants 2021, 10, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pico, J.; Pismag, R.; Laudouze, M.; Martinez, M. Systematic evaluation of the Folin-Ciocalteu and Fast Blue BB reactions during the analysis of total phenolics in vegetables, nuts and plant seeds. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9868–9880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, G.; Lewers, K.; Medina, M.; Saftner, R. Comparative analysis of strawberry total phenolics via Fast Blue BB vs. Folin–Ciocalteu: Assay interference by ascorbic acid. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 27, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Herfellner, T.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P. How does it Phenol Structure Influence the Results of the Folin-Ciocalteu Assay? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudiana, T.; Nurbayti, S.; Ashari, T.H.; Zhorif, S.A.; Suryani, N. Comparison of maceration and Soxhletation methods on the antioxidant activity of the Bouea macrophylla Griff plant. J. Kim. Val. 2023, 9, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, A.; Farid, M. Effect of temperature on polyphenols during extraction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, M.N.; Berset, C. Evolution of antioxidant activity during kilning: Role of insoluble bound phenolic acids of barley and malt. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 1789–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieder, M.; De Oliveira, I.; Bragagnolo, F.; Sanches, V.; Pizani, R.; De Souza Mesquita, L.; Rostagno, M. Consistency of Phenolic Compounds in Plant Residues Parts: A Review of Primary Sources, Key Compounds, and Extraction Trends. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 11515–11534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzella, L.; Moccia, F.; Nasti, R.; Marzorati, S.; Verotta, L.; Napolitano, A. Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Agri-Food Wastes: An Update on Green and Sustainable Extraction Methodologies. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalaxmi, S.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Sreeramulu, K. Polyphenols from different agricultural residues: Extraction, identification and their antioxidant properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 2761–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, P.; Belo, I.; Salgado, J.M. Enhancing Antioxidants Extraction from Agro-Industrial Byproducts by Enzymatic Treatment. Foods 2022, 11, 3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, T.B.N.; Moreira, R.C.; Carvalho, M.G.O.; Arruda, H.S.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M.; Ferreira, M.S.L.; Fai, A.E.C.; Bicas, J.L. from pineapple crown to multi-targeting bioactive compounds by solid-state fermentation using Aspergillus tubingensis. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Du, B.; Ren, X.; Yang, L.; Du, P.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Li, J.; Xiao, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Intracellular self-assembly and metabolite analysis of key enzymes for L-lysine synthesis based on key components of cellulosomes. Front. Microbiol 2025, 16, 1596240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, Z.L.; Koffas, M.A. Biosynthesis and biotechnological production of flavanones: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 83, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steingass, C.; Glock, M.; Schweiggert, R.; Carle, R. Studies on the phenolic patterns of different tissues of the pineapple (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.) by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn and GC-MS analyses. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6463–6479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, M.; Piñeiro, Z.; Barroso, C.G. Stability of phenolic compounds during extraction with superheated solvents. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 921, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrica, M.; Rebucci, R.; Giromini, C.; Tretola, M.; Cattaneo, D.; Baldi, A. Total phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of agri-food waste and by-products. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 18, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Parizad, P.; De Nisi, P.; Scaglia, B.; Scarafoni, A.; Pilu, S.; Adani, F. Recovery of phenolic compounds from agro-industrial by-products: Evaluating antiradical activities and immunomodulatory properties. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 127, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulțescu, M.; Marinaș, I.; Susman, I.; Belc, N. Byproducts (Flour, Meals, and Groats) from the Vegetable Oil Industry as a Potential Source of Antioxidants. Foods 2022, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, M.G.; Markham, K.R. Structure Information from HPLC and On-Line Measured Absorption Spectra; Coimbra University Press: Coimbra, Portugal, 2007; pp. 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, R.J. Phenolic acids in foods: An overview of analytical methodology. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2866–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei, S.; Tehrani, A.D.; Shamlouei, H. Antioxidant activates of new carbohydrate based gallate derivatives: A DFT study. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 377, 121506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.L.; Peterson, K.A. Benchmarking antioxidant-related properties for gallic acid through the use of DFT, MP2, CCSD, and CCSD (T) approaches. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, V.K.; Muraleedharan, K. A computational investigation on the structure, global parameters and antioxidant capacity of a polyphenol, Gallic acid. Food Chem. 2017, 220, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, W.; Chen, Q. The antioxidant properties, metabolism, application and mechanism of ferulic acid in medicine, food, cosmetics, livestock and poultry. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A.; Cristiano, M.C.; Pandolfo, R.; Greco, M.; Fresta, M.; Paolino, D. Improvement of ferulic acid antioxidant activity by multiple emulsions. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambruschini, C.; Demori, I.; El Rashed, Z.; Rovegno, L.; Canessa, E.; Cortese, K.; Moni, L. Synthesis, photoisomerization, antioxidant activity, and lipid-lowering effect of ferulic acid and feruloyl amides. Molecules 2020, 26, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglia, M. Polyphenols as antimicrobial agents. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravo, L. Polyphenols: Chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masek, A.; Chrzescijanska, E.; Latos, M. Determination of antioxidant activity of caffeic acid and p-coumaric acid by using electrochemical and spectrophotometric assays. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 10644–10658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, I.; Yeşiloğlu, Y. Spectroscopic studies on the antioxidant activity of p-coumaric acid. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 115, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazonić, A.; Bucar, F.; Maleš, Ž.; Mornar, A.; Nigović, B.; Kujundẑić, N. Identification and quantification of flavonoids and phenolic acids in burr parsley (Caucalis platycarpos L.), using high-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Molecules 2009, 14, 2466–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, G.; Leong, L. Separation and determination of organic acids and phenolic compounds in fruit juices and beverages by high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatography. A 2002, 977, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Kang, L.; Chen, S.B.; Guo, B. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of flavonoids and phenolic acids in snow chrysanthemum (Coreopsis dyeing Nutt) by HPLC-DAD and UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Molecules 2016, 21, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).