Application of Buckwheat Starch Film Solutions as Edible Coatings for Strawberries: A Proof-of-Concept Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Film Solutions, Strawberry Samples, and Coating Application

2.3. Physicochemical Quality Study

2.3.1. Weight Loss

2.3.2. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) and Firmness

2.3.3. Color

2.3.4. pH, Total Soluble Solids (TSS), and Titratable Acidity (TA)

2.3.5. Decay Index (DI)

2.3.6. Antioxidants Assay

2.3.7. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Assay

2.4. Application as a Film Packaging Material

2.5. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

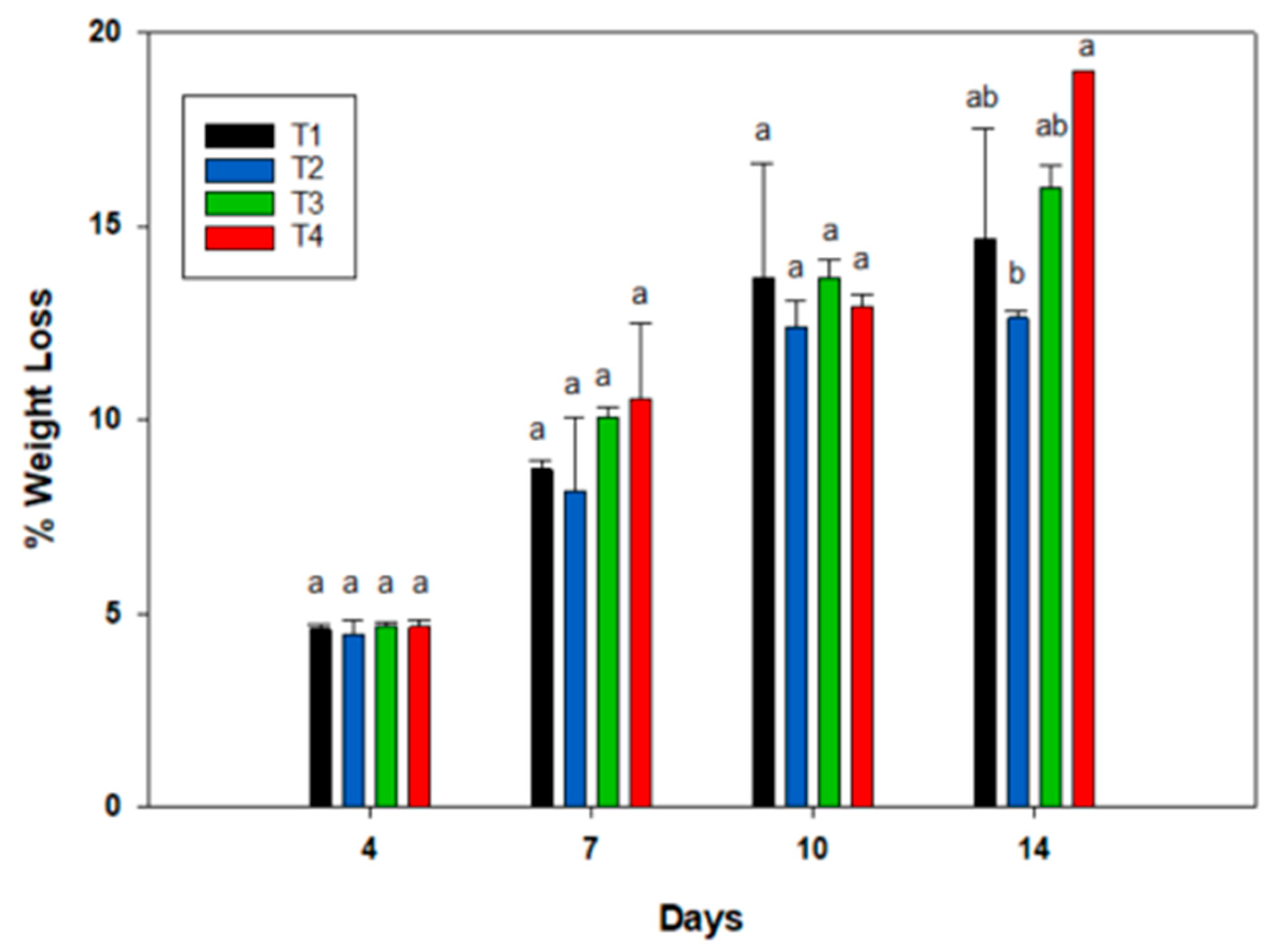

3.1. Weight Loss

3.2. Color Change

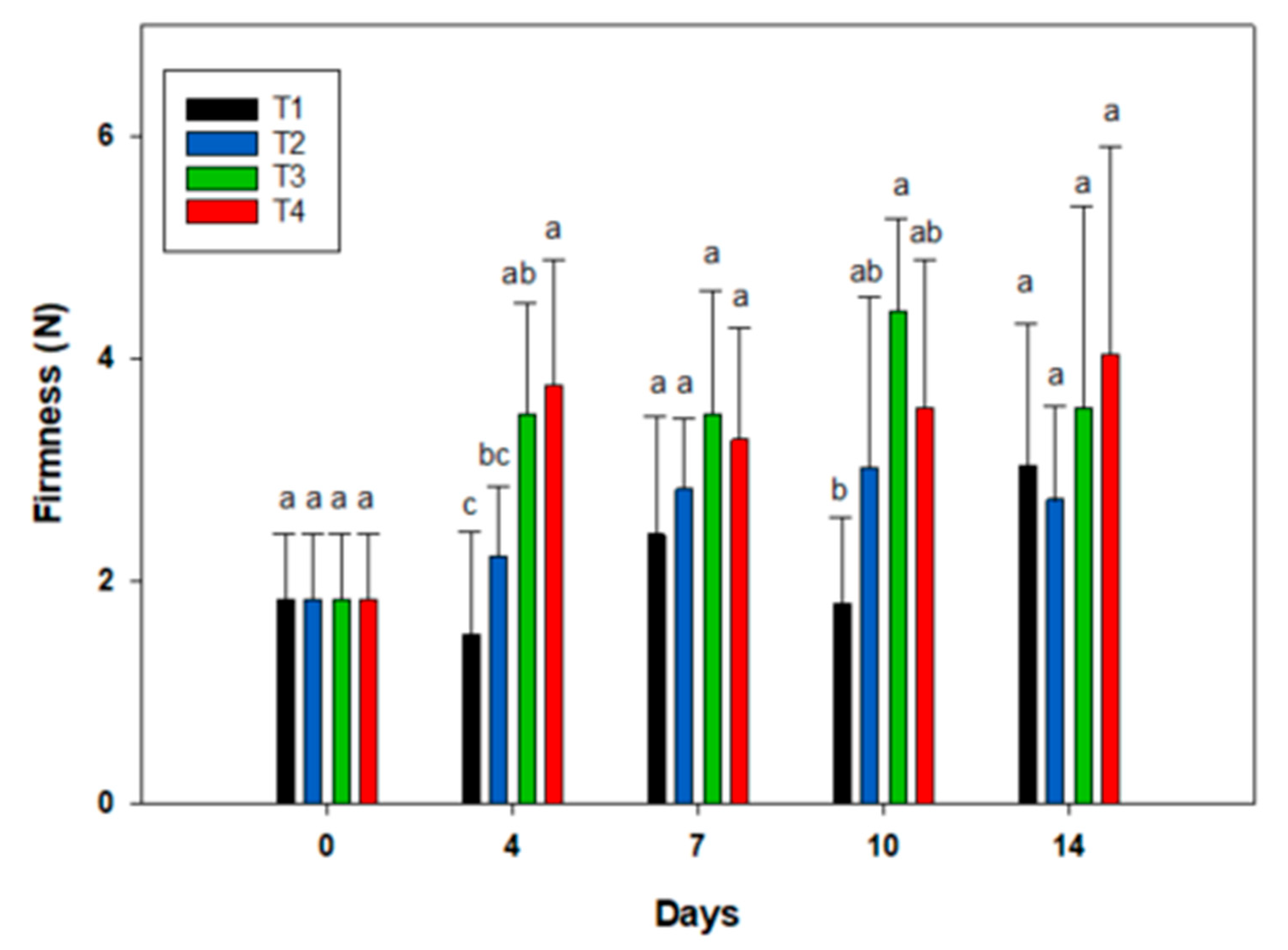

3.3. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA) and Firmness

3.4. Chemical Changes

3.5. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

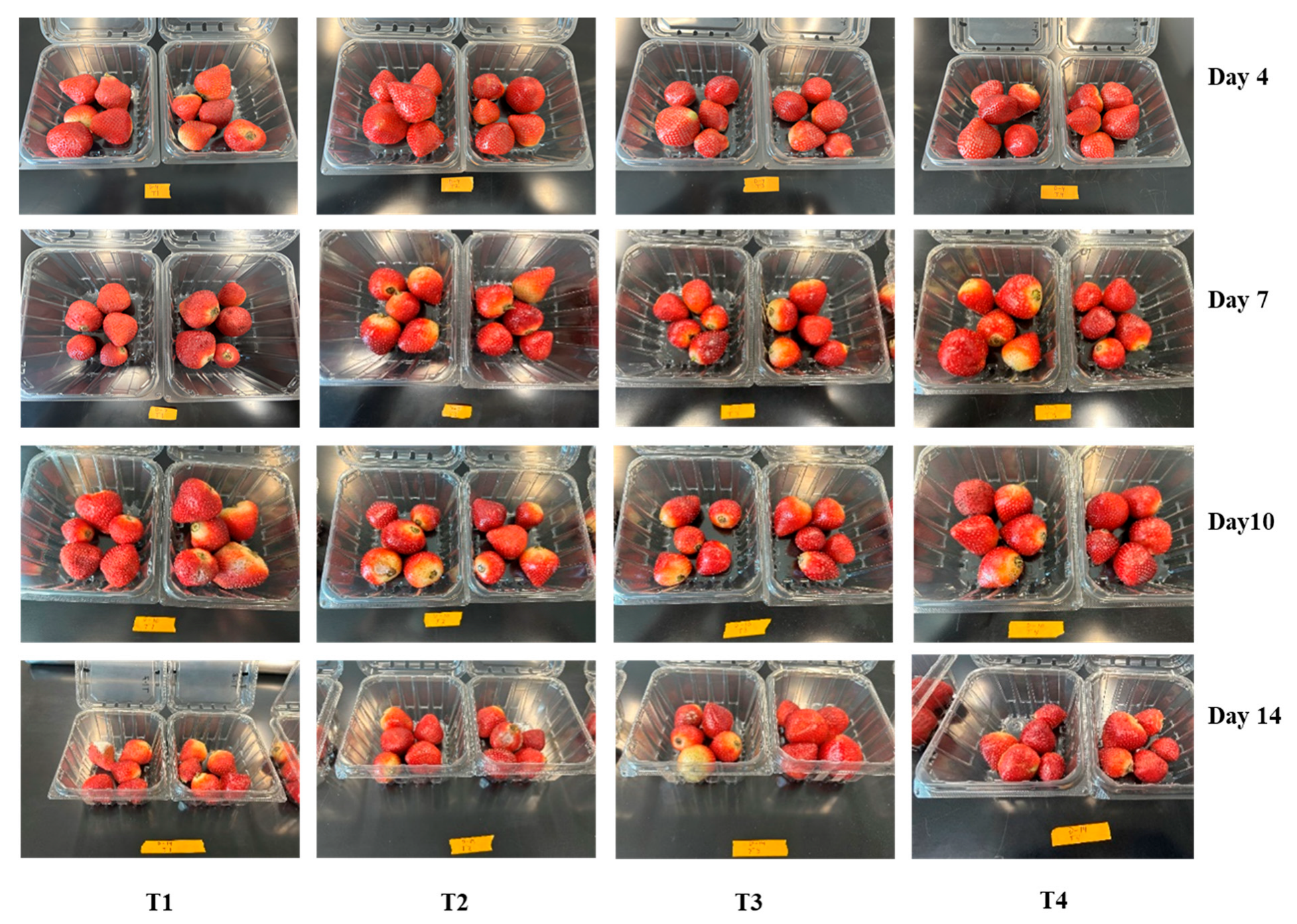

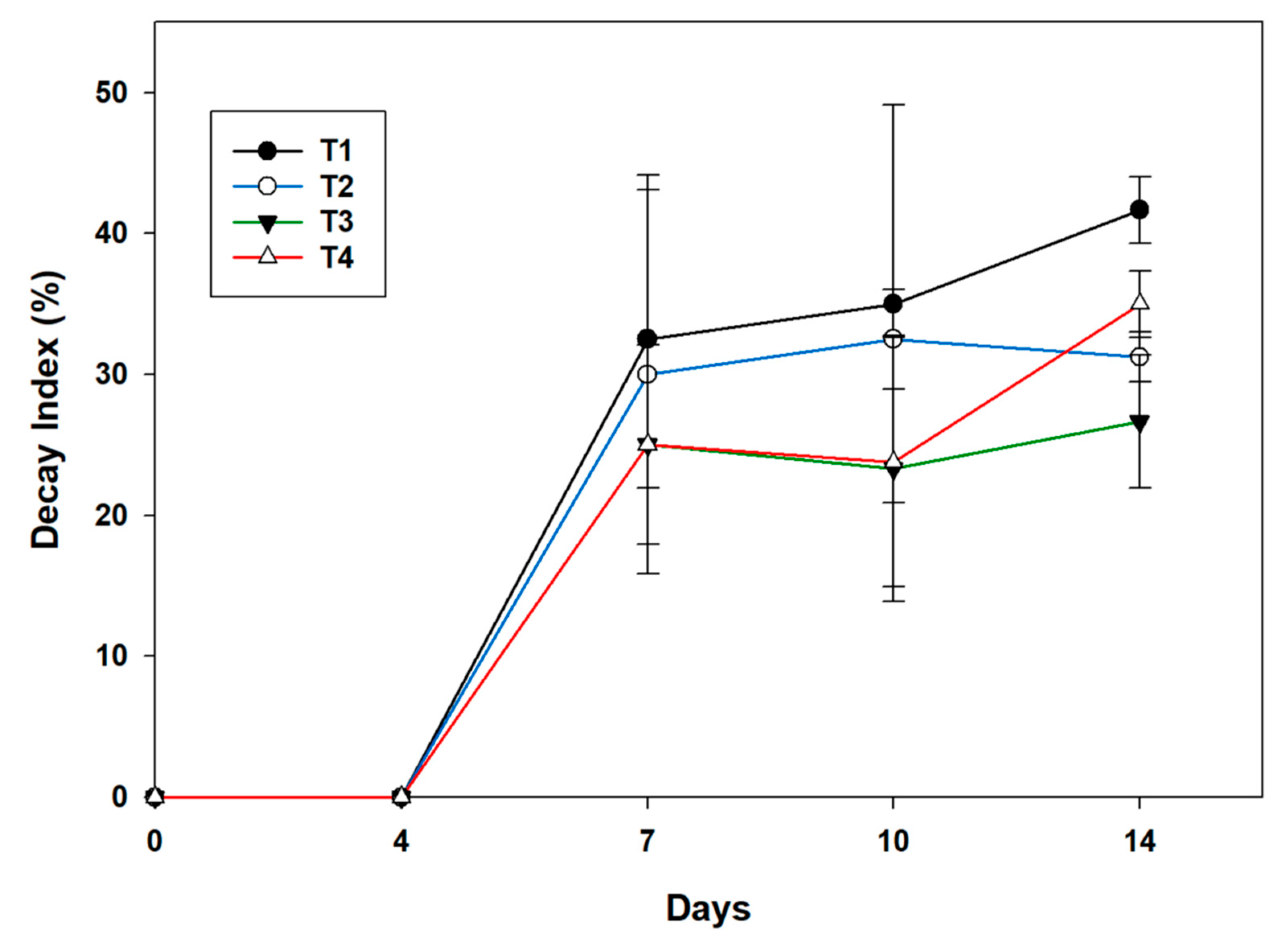

3.6. Decay Index

3.7. Application as a Film Packaging Material

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandla, N.K.; Khatkar, S.K.; Singh, S.; Saxena, D.C.; Jindal, N.; Bansal, V.; Wakchaure, N. Tensile Strength and Solubility Studies of Edible Biodegradable Films Developed from Pseudo-cereal Starches: An Inclusive Comparison with Commercial Corn Starch. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2020, 39, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, D.; Kumar, Y.; Sharanagat, V.S.; Srivastava, T.; Saxena, D.C. Development of pH-sensitive films based on buckwheat starch, critic acid and rose petal extract for active food packaging. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 36, 101236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothornvit, R.; Krochta, J.M. Plasticizer effect on mechanical properties of β-lactoglobulin films. J. Food Eng. 2001, 50, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornsumdaeng, K.; Seeharaj, P.; Prachayawarakorn, J. Property improvement of biodegradable citric acid-crosslinked rice starch films by calcium oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzel, C.; Olsson, E.; Plivelic, T.S.; Andersson, R.; Johansson, C.; Kuktaite, R.; Järnström, L.; Koch, K. Molecular structure of citric acid cross-linked starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 96, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; McClements, D.J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Jin, Z.; Chen, L. Development, characterization, and biological activity of composite films: Eugenol-zein nanoparticles in pea starch/soy protein isolate films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 293, 139342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abral, H.; Basri, A.; Muhammad, F.; Fernando, Y.; Hafizulhaq, F.; Mahardika, M.; Sugiarti, E.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Stephane, I. A simple method for improving the properties of the sago starch films prepared by using ultrasonication treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zheng, H.; Sheng, K.; Liu, W.; Zheng, L. Effects of melatonin treatment on the postharvest quality of strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 139, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gol, N.B.; Patel, P.R.; Rao, T.V.R. Improvement of quality and shelf-life of strawberries with edible coatings enriched with chitosan. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 85, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregel-Zamudio, E.; Angoa-Pérez, M.V.; Oyoque-Salcedo, G.; Aguilar-González, C.N.; Mena-Violante, H.G. Effect of candelilla wax edible coatings combined with biocontrol bacteria on strawberry quality during the shelf-life. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Grift, T.E. Bioactive properties and potential applications of aloe vera gel edible coating on fresh and minimally processed fruits and vegetables: A review. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 2119–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, G.R.; Di Pierro, P.; Mariniello, L.; Esposito, M.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Porta, R. Fresh-cut fruit and vegetable coatings by transglutaminase-crosslinked whey protein/pectin edible films. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 75, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbah, M.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Esposito, M.; Di Pierro, P.; Mariniello, L.; Porta, R. Transglutaminase Cross-Linked Edible Films and Coatings for Food Applications; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Rennie, T.; Shaheb, R.; Matak, K.; Jaczynski, J. Optimization of the properties of underutilized buckwheat starch films through different modification approaches. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 49, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Qian, F.; Mu, G. Characteristics of whey protein concentrate/egg white protein composite film modified by transglutaminase and its application on cherry tomatoes. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 9529–9542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapper, M.; Chiralt, A. Starch-based coatings for preservation of fruits and vegetables. Coatings 2018, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Siddiqui, R.A. Effects of ultrasonic processing on the quality properties of fortified yogurt. Ultrason. Sonochem 2023, 98, 106533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saberi, B.; Golding, J.B.; Marques, J.R.; Pristijono, P.; Chockchaisawasdee, S.; Scarlett, C.J.; Stathopoulos, C.E. Application of biocomposite edible coatings based on pea starch and guar gum on quality, storability and shelf life of ‘Valencia’ oranges. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 137, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdam, M.S.; Fard, J.R. Melatonin treatment attenuates postharvest decay and maintains nutritional quality of strawberry fruits (Fragaria × anannasa cv. Selva) by enhancing GABA shunt activity. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1650–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, A.; Jung, Y.; Siddiqui, R. Yoghurt fortification with green papaya powder and banana resistant starch: Effects on the physicochemical and bioactive properties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 5745–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Sarker, A.; Deltsidis, A.; Shaheb, M.R.; Grift, T.E. Effect of aloe vera gel-glycerol edible coating on the shelf-life and the kinetics of colour change of minimally processed cucumber during storage. Int. J. Postharvest Technol. Innov. 2021, 8, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Hashemi, M.; Hosseini, S.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with Cinnamomum zeylanicum essential oil enhance the shelf life of cucumber during cold storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 110, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogvar, O.B.; Koushesh Saba, M.; Emamifar, A. Aloe vera and ascorbic acid coatings maintain postharvest quality and reduce microbial load of strawberry fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 114, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermesonlouoglou, E.K.; Pourgouri, S.; Taoukis, P.S. Kinetic study of the effect of the osmotic dehydration pre-treatment to the shelf life of frozen cucumber. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2008, 9, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phisut, N. Factors affecting mass transfer during osmotic dehydration of fruits. Int. Food Res. J. 2012, 19, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, A.; Deltsidis, A.; Grift, T.E. Effect of Aloe vera gel-Carboxymethyl Cellulose composite coating on the degradation kinetics of cucumber. J. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 46, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, G.; Grimm, E.; Bruggenwirth, M.; Knoche, M. Strawberry fruit skins are far more permeable to osmotic water uptake than to transpirational water loss. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Maqbool, M.; Ramachandran, S.; Alderson, P.G. Gum arabic as a novel edible coating for enhancing shelf-life and improving postharvest quality of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 58, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretto, G.; Du, W.X.; Avena-Bustillos, R.J.; De, J.; Berrios, J.; Sambo, P.; McHugh, T.H. Electrostatic and Conventional Spraying of Alginate-Based Edible Coating with Natural Antimicrobials for Preserving Fresh Strawberry Quality. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2017, 10, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amal, S.H.; El-Mogy, M.M.; Aboul-Anean, H.E.; Alsanius, B.W. Improving Strawberry Fruit Storability by Edible Coating as a Carrier of Thymol or Calcium Chloride. J. Hortic. Sci. Ornam. Plants 2010, 2, 88–97. Available online: www.idosi.org/jhsop/2(3)10/2.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Arifin, H.R.; Setiasih, I.S.; Hamdani, J.S. Shelf life and characteristics of strawberry (Fragaria nilgerensis L.) coated by Aloe vera—Glycerol and packed with perforated plastic film. In Proc. Second Asia Pacific Symp. on Postharvest Research, Education and Extension. ISHS Acta Horticulturae 1011; Purwadaria, H.K., Ed.; International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS): Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2013; pp. 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Asmar, A.; Giosafatto, C.V.L.; Sabbah, M.; Sanchez, A.; Santana, R.V.; Mariniello, L. Effect of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on the physicochemical properties of pectin packaging material for strawberry wrapping. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, S.; Achaerandio, I.; Sepulcre, F.; Pujolà, M. Aloe vera based edible coatings improve the quality of minimally processed ‘ Hayward ’ kiwifruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2013, 81, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopacka, D.; Plocharski, W.J. Effect of storage conditions on the relationship between apple firmness and texture acceptability. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2004, 32, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lufu, R.; Ambaw, A.; Opara, U.L. Water loss of fresh fruit: Influencing pre-harvest, harvest and postharvest factors. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 272, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidado, M.J.; Gunny, A.A.N.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Ali, A.; Wongs-Aree, C.; Salleh, N.H.M. Challenges of postharvest water loss in fruits: Mechanisms, influencing factors, and effective control strategies—A comprehensive review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 17, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maftoonazad, N.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Postharvest shelf-life extension of avocados using methyl cellulose-based coating. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 38, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Hashemi, M.; Hosseini, S.M. Postharvest treatment of nanochitosan-based coating loaded with Zataria multiflora essential oil improves antioxidant activity and extends shelf-life of cucumber. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 33, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baswal, A.K.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Singh, Z.; Mahajan, B.V.C. Influence of types of modified atmospheric packaging (MAP) films on cold-storage life and fruit quality of ‘kinnow’ mandarin (Citrus nobilis Lour X C. deliciosa Tenora). Int. J. Fruit. Sci. 2020, 20, S1552–S1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, G.; Sedaghat, N.; Woltering, E.J.; Farhoodi, M.; Mohebbi, M. Chitosan-limonene coating in combination with modified atmosphere packaging preserve postharvest quality of cucumber during storage. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Y.; Jo, W.S.; Song, N.B.; Min, S.C.; Song, K.B. Quality change of apple slices coated with Aloe vera gel during storage. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, C817–C822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Khan, A.S.; Nawaz, A.; Anjum, M.A.; Naz, S.; Ejaz, S.; Hussain, S. Aloe vera gel coating delays postharvest browning and maintains quality of harvested litchi fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 157, 110960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.; Smitha, V.; Jisha, M.S. Antifungal, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of chitosan nanoparticles and its use as an edible coating on vegetables. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzola-Rodríguez, S.I.; Muñoz-Castellanos, L.N.; López-Camarillo, C.; Salas, E. Phenolipids, Amphipilic Phenolic Antioxidants with Modified Properties and Their Spectrum of Applications in Development: A Review. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, S.H.M.C.; Silva, E.K.; Alvarenga, V.O.; Moraes, J.; Freitas, M.Q.; Silva, M.C.; Raices, R.S.L.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Meireles, M.A.A.; Cruz, A.G. Effects of ultrasound energy density on the non-thermal pasteurization of chocolate milk beverage. Ultrason. Sonochem 2018, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Gan, C.; Ren, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, Z. Riboflavin application delays senescence and relieves decay in harvested strawberries during cold storage by improving antioxidant system. LWT 2023, 182, 114810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R.; Pristijono, P.; Golding, J.B.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Scarlett, C.J.; Bowyer, M.; Singh, S.P.; Vuong, Q.V. Development and application of rice starch based edible coating to improve the postharvest storage potential and quality of plum fruit (Prunus salicina). Sci. Hortic. 2018, 237, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadim, Z.; Ahmadi, E.; Sarikani, H.; Chayjan, A.R. Effect of Methylcellulose-Based Edible Coating on Strawberry Fruit’s Quality Maintenance During Storage. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 39, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burel, C.; Kala, A.; Purevdorj-Gage, L. Impact of pH on citric acid antimicrobial activity against Gram-negative bacteria. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 72, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznanski, P.; Hameed, A.; Orczyk, W. Chitosan and Chitosan Nanoparticles: Parameters Enhancing Antifungal Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 2996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Film Samples | WVP (g mm/mm2 h kPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Moisture Sorption (%) After 6 h |

|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 2.73 × 10−10 ± 2.26 × 10−11 | 4.41 ± 0.83 | 77.32 ± 0.64 |

| T3 | 2.76 × 10−11 ± 1.64 × 10−11 | 3.48 ± 0.57 | 65.33 ± 0.47 |

| T4 | 2.13 × 10−10 ± 1.04 × 10−11 | 10.89 ± 6.65 | 73.88 ± 4.88 |

| Treatments | Only Distilled Water | Buckwheat Starch | Citric Acid (CA) and Chitosan Nanoparticles (CNP) | Ultrasound Treatment Before Gelatinization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (negative control) | + | − | − | − |

| T2 (positive control) | − | + | − | − |

| T3 | − | + | + | − |

| T4 | − | + | + | + |

| Df | SS | MS | F | Pr (>F) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Weight loss (n = 3) | Trt. | 3 | 24.36 | 8.121 | 4.9838 | 0.0125 * |

| Day | 3 | 551.06 | 183.686 | 112.7233 | 5.674 × 10−11 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 28.01 | 3.112 | 1.9097 | 0.1241 | |

| Residuals | 16 | 26.07 | 1.630 | |||

| L* (n = 8) | Trt | 3 | 115.57 | 38.52 | 1.7098 | 0.1689 |

| Day | 4 | 2105.79 | 526.45 | 23.3660 | 3.747 × 10−14 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 273.11 | 30.35 | 1.3469 | 0.2208 | |

| Residuals | 115 | 2591.00 | 22.53 | |||

| a* (n = 8) | Trt | 3 | 530.75 | 176.917 | 25.9433 | 6.856 × 10−13 *** |

| Day | 4 | 398.63 | 99.658 | 14.6140 | 1.111 × 10−9 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 111.61 | 12.401 | 1.8184 | 0.0721 | |

| Residuals | 115 | 784.23 | 6.819 | |||

| b* (n = 8) | Trt | 3 | 516.61 | 172.203 | 15.6502 | 1.336 × 10−8 *** |

| Day | 4 | 270.88 | 67.720 | 6.1545 | 0.0001595 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 166.19 | 18.466 | 1.6782 | 0.1020587 | |

| Residuals | 115 | 1265.38 | 11.003 | |||

| Hardness (n = 10) | Trt | 3 | 30.608 | 10.2026 | 14.2888 | 4.97 × 10−8 *** |

| Day | 4 | 6.357 | 1.5893 | 2.2258 | 0.07015 | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 6.505 | 0.7228 | 1.0122 | 0.43414 | |

| Residuals | 121 | 86.397 | 0.7140 | |||

| Springiness (n = 10) | Trt | 3 | 33.35 | 11.1155 | 2.1360 | 0.09921 |

| Day | 4 | 16.23 | 4.0571 | 0.7796 | 0.54054 | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 81.09 | 9.0099 | 1.7314 | 0.08892 | |

| Residuals | 121 | 629.68 | 5.2040 | |||

| Chewiness (n = 10) | Trt | 3 | 0.04088 | 0.0136254 | 1.7678 | 0.15693 |

| Day | 4 | 0.10406 | 0.0260154 | 3.3753 | 0.01175 * | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 0.01346 | 0.0014954 | 0.1940 | 0.99445 | |

| Residuals | 121 | 0.93262 | 0.0077076 | |||

| Firmness (n = 6) | Trt. | 3 | 48.99 | 16.3299 | 12.5856 | 5.906 × 10−7 *** |

| Day | 3 | 4.421 | 1.4736 | 1.1357 | 0.3390 | |

| Trt × Day | 4 | 4.937 | 1.2341 | 0.9512 | 0.4383 | |

| Residuals | 91 | 118.073 | 1.2975 |

| Treatments a | Days of Storage at 4 ± 1 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 14 | |

| L* | |||||

| T1 | 19.19 ± 4.13 a | 20.85 ± 4.19 a | 24.85 ± 5.31 a | 22.93 ± 7.66 a | 12.26 ± 3.41 b |

| T2 | 19.19 ± 4.13 a | 18.07 ± 2.73 a | 26.31 ± 4.30 a | 23.28 ± 3.86 a | 12.28 ± 6.70 b |

| T3 | 19.19 ± 4.13 a | 17.66 ± 4.73 a | 23.88 ± 2.59 a | 24.07 ± 6.14 a | 20.15 ± 5.14 a |

| T4 | 19.19 ± 4.13 a | 17.92 ± 3.08 a | 25.99 ± 4.05 a | 21.45 ± 2.43 a | 14.63 ± 6.89 ab |

| a* | |||||

| T1 | 23.01 ± 3.36 a | 24.66 ± 2.78 a | 27.55 ± 1.84 a | 24.83 ±3.93 a | 24.86 ± 2.36 a |

| T2 | 23.01 ± 3.36 a | 22.59 ± 2.10 a | 26.55 ± 1.99 a | 22.89 ± 1.94 ab | 22.47 ± 2.18 ab |

| T3 | 23.01 ± 3.36 a | 19.12 ± 2.36 b | 22.25 ±3.27 b | 20.57 ±3.00 b | 21.04 ± 3.11 b |

| T4 | 23.01 ± 3.36 a | 19.27 ± 1.74 b | 25.51 ± 2.56 ab | 19.14 ± 2.70 b | 17.46 ± 2.12 c |

| b* | |||||

| T1 | 19.18 ± 5.02 a | 15.55 ± 5.18 a | 15.76 ± 4.54 a | 15.00 ± 2.95 a | 14.91 ± 1.85 a |

| T2 | 19.18 ± 5.02 a | 14.75 ± 1.97 a | 14.76 ± 2.87 a | 14.26 ± 3.78 a | 12.28 ± 3.03 ab |

| T3 | 19.18 ± 5.02 a | 10.18 ± 1.53 a | 13.29 ± 4.79 a | 11.07 ± 2.77 ab | 10.33 ± 2.95 b |

| T4 | 19.18 ± 5.02 a | 10.88 ± 1.84 a | 16.42 ± 3.38 a | 8.82 ± 2.00 b | 9.82 ± 2.78 b |

| Treatments a | Days of Storage at 4 ± 1 °C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 14 | |

| Hardness (N) | |||||

| T1 | 2.00 ± 0.67 a | 1.45 ± 0.85 b | 1.17 ± 0.60 b | 1.16 ± 0.46 a | 1.43 ± 0.35 b |

| T2 | 2.00 ± 0.67 a | 2.24 ± 0.67 ab | 2.27 ± 0.61 a | 2.10 ± 0.48 a | 1.90 ± 0.99 b |

| T3 | 2.00 ± 0.67 a | 2.87 ± 1.14 a | 2.52 ± 0.89 a | 2.31 ± 1.68 a | 3.26 ± 0.84 a |

| T4 | 2.00 ± 0.67 a | 2.76 ± 0.80 a | 2.20 ± 0.96 a | 2.41 ± 0.74 a | 1.72 ± 0.95 b |

| Springiness | |||||

| T1 | 4.02 ± 0.98 a | 3.07 ± 0.37 a | 3.29 ± 0.48 a | 3.83 ± 0.73 a | 3.29 ± 0.48 a |

| T2 | 4.02 ± 0.98 a | 3.59 ± 0.65 a | 3.28 ± 0.34 a | 3.56 ± 0.52 ab | 3.08 ± 0.51 a |

| T3 | 4.02 ± 0.98 a | 3.28 ± 0.66 a | 3.22 ± 0.41 a | 2.29 ± 1.18 b | 2.50 ± 1.94 a |

| T4 | 4.02 ± 0.98 a | 3.44 ± 0.83 a | 3.52 ± 0.67 a | 3.85 ± 0.65 a | 3.71 ± 1.59 a |

| Chewiness (N) | |||||

| T1 | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.07 ± 0.06 a | 0.07 ± 0.03 a | 0.13 ± 0.04 a | 0.11 ± 0.07 a |

| T2 | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.07 ± 0.03 a | 0.07 ± 0.06 a | 0.09 ± 0.04 a | 0.15 ± 0.09 a |

| T3 | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.11 ± 0.08 a | 0.10 ± 0.11 a | 0.12 ± 0.12 a | 0.18 ± 0.20 a |

| T4 | 0.05 ± 0.02 a | 0.08 ± 0.05 a | 0.09 ± 0.14 a | 0.14 ± 0.06 a | 0.15 ± 0.11 a |

| Df | SS | MS | F | Pr (>F) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH (n = 3) | Trt. | 3 | 0.06876 | 0.022922 | 3.0434 | 0.04118 * |

| Day | 4 | 0.62238 | 0.155595 | 20.6592 | 6.442 × 10−9 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 10 | 0.12754 | 0.012754 | 1.6934 | 0.12039 | |

| Residuals | 36 | 0.27113 | 0.007531 | |||

| TSS (n = 3) | Trt. | 3 | 3.6384 | 1.2128 | 515.44 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** |

| Day | 4 | 17.1448 | 4.2862 | 1821.64 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 11.4783 | 1.2754 | 542.03 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Residuals | 36 | 0.0800 | 0.0024 | |||

| % TA (n = 3) | Trt | 3 | 0.013972 | 0.004657 | 636.87 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** |

| Day | 4 | 0.156258 | 0.039065 | 5341.99 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 0.080491 | 0.008943 | 1223.00 | 2.2 × 10−16 *** | |

| Residuals | 36 | 0.000249 | 0.000007 | |||

| AA (n = 3) | Trt | 3 | 1.5336 | 0.51118 | 7.2086 | 0.0007515 *** |

| Day | 4 | 9.2857 | 2.32143 | 32.7362 | 4.62 × 10−11 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 3.3691 | 0.37434 | 5.2788 | 0.0001806 *** | |

| Residuals | 33 | 2.3401 | 0.07091 | |||

| TPC (n = 3) | Trt | 3 | 0.82126 | 0.273752 | 20.4468 | 9.447 × 10−8 *** |

| Day | 4 | 0.10462 | 0.026154 | 1.9535 | 0.124 | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 1.14524 | 0.127249 | 9.5044 | 4.685 × 10−7 *** | |

| Residuals | 34 | 0.45521 | 0.013388 | |||

| % DI (n = 2) | Trt | 3 | 322.4 | 107.45 | 2.0753 | 0.1439 |

| Day | 3 | 5598.7 | 1866.23 | 36.0423 | 2.394 × 10−7 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 9 | 218.0 | 24.23 | 0.4679 | 0.8754 | |

| Residuals | 16 | 828.5 | 51.78 | |||

| % Weight loss_film package (n = 3) | Trt | 3 | 1480.83 | 493.61 | 60.9564 | 1.230 × 10−11 *** |

| Day | 1 | 242.57 | 242.57 | 29.9558 | 1.101 × 10−5 *** | |

| Trt × Day | 2 | 103.67 | 51.84 | 6.4014 | 0.005691 ** | |

| Residuals | 25 | 202.44 | 8.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarker, A.; Nicholas-Okpara, V.A.N.; Shaheb, M.R.; Matak, K.; Jaczynski, J. Application of Buckwheat Starch Film Solutions as Edible Coatings for Strawberries: A Proof-of-Concept Study. AgriEngineering 2025, 7, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120410

Sarker A, Nicholas-Okpara VAN, Shaheb MR, Matak K, Jaczynski J. Application of Buckwheat Starch Film Solutions as Edible Coatings for Strawberries: A Proof-of-Concept Study. AgriEngineering. 2025; 7(12):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120410

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarker, Ayesha, Viola A. N. Nicholas-Okpara, Md Rayhan Shaheb, Kristen Matak, and Jacek Jaczynski. 2025. "Application of Buckwheat Starch Film Solutions as Edible Coatings for Strawberries: A Proof-of-Concept Study" AgriEngineering 7, no. 12: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120410

APA StyleSarker, A., Nicholas-Okpara, V. A. N., Shaheb, M. R., Matak, K., & Jaczynski, J. (2025). Application of Buckwheat Starch Film Solutions as Edible Coatings for Strawberries: A Proof-of-Concept Study. AgriEngineering, 7(12), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriengineering7120410