Abstract

This review explores the relationship between urban energy planning and smart city evolution, addressing three primary questions: How has research on smart cities and urban energy planning evolved in the past thirty years? What promises and hurdles do smart city initiatives introduce to urban energy planning? And why do some smart city projects surpass energy efficiency and emission reduction targets while others fall short? Based on a bibliometric analysis of 9320 papers published between January 1992 and May 2023, five dimensions were identified by researchers trying to address these three questions: (1) energy use at the building scale, (2) urban design and planning integration, (3) transportation and mobility, (4) grid modernization and smart grids, and (5) policy and regulatory frameworks. A comprehensive review of 193 papers discovered that previous research prioritized technological advancements in the first four dimensions. However, there was a notable gap in adequately addressing the inherent policy and regulatory challenges. This gap often led to smart city endeavors underperforming relative to their intended objectives. Overcoming the gap requires a better understanding of broader issues such as environmental impacts, social justice, resilience, safety and security, and the affordability of such initiatives.

1. Introduction

While cities cover a mere 3% of Earth’s total land expanse [1], they are home to over half of the world’s inhabitants [2] and play a crucial role as centers of energy consumption, with estimates showing that they annually consume 60% to 80% of the world’s energy [3,4], mainly derived from non-renewable sources [5]. Moreover, from an environmental standpoint, cities bear significant responsibility for approximately 70% to 75% of global GHG emissions [4,6,7]. Projections suggest that by 2050, urban areas will cradle nearly 70% of the world’s inhabitants [3,8]. Intriguingly, with every 1% increase in the urbanization rate, the consumption of non-renewable energy grows by about 0.72% [9]. This escalating urban population, coupled with heightened energy consumption and GHG emissions, although indicative of economic strides and societal advancement [10,11], simultaneously raises concerns about sustainability and resilience.

With energy as the lifeblood of modern cities, urbanization faces mounting pressures including escalating demands, environmental imperatives, diminishing non-renewable resources, fluctuating supplies and prices in global markets, infrastructural limitations, and the vulnerability of urban energy systems to the existential threat of climate change [12,13,14]. Furthermore, emerging research underscores the pivotal role of buildings, urban form and spatial structure, transportation systems, renewable energy (RE), energy infrastructure, and power grids in enhancing cities’ energy profiles and performance [5,14,15,16]. By constructing and retrofitting energy-efficient systems, curbing urban sprawl, optimizing RE integration, improving urban microclimates, and fostering walkable and mixed-use urban settlements, cities can potentially break from a past built on energy-intensive sectors [13,14,15]. As such, the integration of energy planning into urban planning and management procedures is not just prudent but potentially transformative, especially when contextualized within the overarching goals of climate change mitigation and decarbonization [4,17,18].

The emergence of “Smart Cities” offers promising solutions to facilitate this integration and can address pressing energy and sustainability challenges through a new generation of information and data-driven urban and energy planning [14,19,20]. Grounded in the evolving field of urban planning and supported by technological advancements such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), Digital Twins (DTs), Remote Sensing (RS), Geographic Information System (GIS), Internet of Things (IoT), Intelligent Transportation System (ITS), and smart grids, smart cities aim to integrate Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) into city planning process [20,21,22,23,24]. These tools and technologies enable the optimization of energy consumption, the integration of RE sources into the urban fabric, a reduction in GHG emissions, and ultimately an improvement of the quality of urban life as a whole [19,25,26,27]. However, achieving the potential of the smart city model is not without hurdles along the way. The advancement of smart cities poses various challenges, including managing and interconnecting complex tools, platforms, and sensors, and gathering and analyzing large data sets while ensuring system interoperability and addressing security and privacy concerns [28,29,30]. Additionally, the rapid pace of technological change necessitates continuous adaptation and multidisciplinary cooperation among engineers, city planners, social and behavioral scientists, utility planners, and city administrators [31]. Ensuring equitable access to these smart solutions to prevent the emergence of “digital divides” within urban populations is another significant challenge [32]. Last but not least, financial constraints can also impede the large-scale deployment of advanced technologies from building to city scale [19,33,34].

While the existing literature highlights the transformative potentials and technological advancements associated with the energy aspects of smart cities, it does not thoroughly explore the complexities and challenges involved [30]. Specifically, this advanced review shows a dearth of scholarly investigations that assess the potential advantages and difficulties associated with energy-focused smart city initiatives. Addressing this deficiency is crucial and an advanced review in this domain can offer deeper insights into the multifaceted nature of smart city initiatives. Equipped with this knowledge, decision-makers and stakeholders can make more informed choices and policies, particularly concerning the inherent trade-offs elucidated by such studies. This review endeavors to bridge this gap by thoroughly examining the synergy between urbanization, energy planning, and smart city evolution, specifically addressing the following three questions:

- How has the research on the convergence of smart cities and urban energy planning transformed over the past three decades?

- What are the promising benefits and accompanying challenges that smart city initiatives introduce in the realm of urban energy planning?

- Why do some smart city projects, despite rapid technological advancements, struggle to consistently achieve energy efficiency and carbon emission reduction goals, while others succeed?

A methodology using bibliometric analysis and scoping review was employed to answer these questions. Initially, guided by the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) framework [35], we undertook a bifurcated literature selection procedure. The initial search of the literature yielded 9320 pertinent papers published between January 1992 and May 2023. We cataloged the metadata of these publications into VOSviewer software, generating co-occurrence maps of keywords. Several insights were gained from an in-depth examination of these maps. Firstly, this analysis identifies three distinct phases in the literature on smart cities and urban energy planning: an initial focus on technology, smart transportation, and sustainable urban governance (January 1992–2008), a middle phase emphasizing rapid technological advancements with a limited socioeconomic focus (2008–2017), and a recent trend towards integrating technological growth with socio-ecological and economic considerations (2018–May 2023). However, there is a notable gap between studies on the technical aspects of smart cities and those addressing their socio-economic and environmental. Secondly, the analysis unearthed five pivotal dimensions encapsulating the nexus between urban energy planning and smart city endeavors: 1. Energy use at the building scale, 2. Urban design and planning integration, 3. Transportation and mobility, 4. Grid modernization and smart grids, and 5. Policy and regulatory frameworks.

These dimensions served as the foundation for a second phase of review that involved scoping questions. Initially, subsequent scrutiny refined the obtained paper collection, narrowing it down to 193 key papers deemed suitable for an in-depth review and evaluation. This in-depth review revealed that the great majority of studies highlighted the advantages of incorporating energy systems into smart urban environments and there is a scarcity of research regarding the current and future challenges and obstacles that could undermine the effectiveness of nearly all energy-related smart city initiatives. Only in recent years has academia begun to scrutinize the prevailing and potential challenges. Furthermore, despite notable technological advancements and the myriad of smart city initiatives aiming to enhance urban energy efficiency across dimensions 1–4, a deficit in research exists regarding appropriate policy and regulatory frameworks.

The abovementioned identified issues could be among the main reasons why some smart city projects deviate from their energy and environmental objectives, exacerbate socio-economic disparities, and grapple with an array of technical challenges. Therefore, for smart city projects to truly augment urban energy sustainability, inclusivity, and resilience, there is an exigent need for integrative frameworks and policies. Such paradigms should transcend mere technical considerations, encompassing environmental and socio-economic determinants as well. To strike this balance, further research is needed on overall energy performance, environmental impacts, public engagement, socioeconomic justice and inclusion, technical and implementation complexities, and resilience, privacy, and security concerns of energy-related smart city initiatives.

2. Materials and Methods

In this advanced review, we employed an integrated bibliometric and scoping review methodology. As articulated by Page et al. [36], review papers play a significant role in compiling and analyzing existing knowledge in a particular field, allow for inquiry into questions unavailable to individual studies, identify shortcomings within primary research, and contribute to the development or evaluation of theories. In conducting this review, we followed the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA-ScR to ensure transparency and adherence to best practices [35]. Moreover, we performed this review utilizing the six stages suggested by Cooper and Hedges [37], which include problem identification, literature exploration, data evaluation, data analysis, interpretation of results, and presentation of findings.

We employed primary scientific sources from the Web of Science (WoS) database, the oldest and most widely used database of research publications and citations worldwide [38]. This approach was taken to avoid overlooking crucial and up-to-date sources, as well as to obtain reliable access to ontologies, underlying hypotheses, families of terms, main components, and processes. To direct the WoS literature search process, a preliminary review of 19 reports and documents, published by reputable organizations (Appendix B, Table A1), was conducted to extract an initial list of keywords for defining search strings. To ensure the relevance of the extracted keywords, a panel consisting of 14 experts from diverse fields such as urban planning, transportation planning, architecture, electronic engineering, computer science, geography, and energy and environmental policy was convened for consultation. Using a Delphi questionnaire, the experts rated the importance of each statement or keyword and submitted additional keywords not included in the initial questionnaire. This assessment utilized a Likert-type response scale consisting of five points ranging from “Extremely important” to “Not at all important”. The administration of this survey was carried out through Google Forms in April 2023.

The next phase involved devising the research protocol and determining specific criteria for inclusion and exclusion (Table 1). These criteria play a crucial role in narrowing down the search scope and ensuring that only articles relevant to the topic are selected [35]. To create an effective search strategy, expert input was considered alongside these criteria, leading to the compilation of targeted search strings. Then, we reviewed and refined the search strings together to enhance accuracy and ensure consistent application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In each round, we screened the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the first 200 articles to further improve the search string’s precision. After five rounds of development and refinement, the final search string yielded 11,800 papers. Using our predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 9320 papers were chosen to be imported into VOSviewer software (version 1.16.9) for bibliometric analysis.

Table 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria.

It is worthwhile to note that during the preceding steps, we discovered that there have been remarkable advancements in smart city technologies, policy frameworks, and energy planning methods over the past three decades. The term “Smart City” emerged in the 1990s, bringing forth new possibilities for how modern technology could impact urban areas. Dameri and Cocchia [39] provided a comprehensive account of the origins of this concept, highlighting that its initial conceptualization occurred in 1992 by Gibson et al. [40] through their book titled “The Technopolis Phenomenon: Smart Cities, Fast Systems, Global Networks”. Accordingly, we selected the time period from January 1992 to May 2023 to conduct this bibliometric and scoping review. Examining this period allowed us to gain a deeper comprehension of how urban energy planning practices have evolved and how smart city initiatives have been incorporated into rapidly changing energy landscapes.

VOSviewer is a freely accessible tool designed specifically for conducting bibliometric analyses. It utilizes the VOS mapping technique developed by Van Eck and Waltman [41], which stands for “visualization of similarities”. One application of VOSviewer, serving as the foundation for this paper, is to generate visual maps depicting keyword relationships and networks using co-occurrence data [42]. By using this software, researchers can visually represent the connections and associations between keywords in a dataset, providing insights into their relationships, underlying co-occurrence patterns, and trends in specific research areas [43].

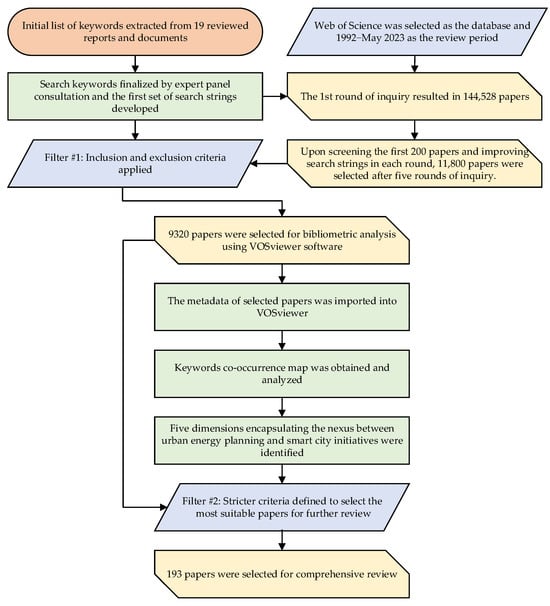

While bibliometric analysis can effectively handle and derive insights from the initial set of 9320 papers, we used a stringent filter to identify key papers for the in-depth review. The initial step involved applying the highly cited papers filter on the WoS, which trimmed the number of papers from 9320 to 254. Subsequently, we scanned these papers to identify those that cover one or more of the five identified dimensions and address potential advantages and/or challenges associated with integrating smart city initiatives into urban energy planning. This selection process culminated in a refined set of 193 papers. The total of 193 papers reviewed in this study exceeds the typical average number of review articles. Given the multidisciplinary and multifaceted nature of the investigated topic, it was imperative to encompass a broad range of literature to ensure all pertinent aspects were adequately addressed. The overall review process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The review procedure.

3. Results of the Bibliometric Analysis

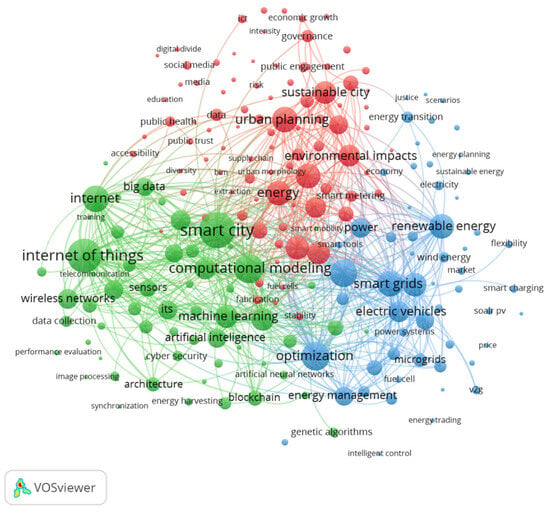

The co-occurrence map, crafted using VOSviewer software, illustrates a visual narrative of the research landscape, including keywords, clusters, and their interrelationships (Figure 2). Each node in this map represents a specific keyword, with the size of each node indicating its frequency or significance in the literature [42]. The connections between nodes represent frequent co-occurrences and suggest topics often discussed together. The thickness and proximity of these links indicate the degree of association between keywords. Nodes close to each other on the map tend to co-occur more frequently, reflecting a stronger relationship between them [43]. Additionally, there are three clusters whose keywords exhibit closer relationships with each other than with keywords from other clusters. Terms within the same cluster share thematic coherence, meaning they are often discussed in conjunction or in relation to each other.

Figure 2.

Keywords co-occurrence network (January 1992–May 2023).

In Figure 2, the first cluster, illustrated in green, draws attention to the significant role emerging technologies have in shaping urban energy systems. This cluster underscores the integration of AI, 5G, IoT, sensors, and other communication technologies, emphasizing their role in real-time data processing and decision-making. Notably, this cluster also accentuates concerns surrounding cybersecurity, privacy, and energy efficiency, highlighting the dual narrative of technological advancements and their potential challenges. The second cluster, in red, shifts the focus to the intersection of urban development and environmental sustainability, underscoring the need for sustainable practices amidst climate change discussions. However, this cluster reveals a disparity by incorporating technological advancements with human-centric issues. Lastly, the third cluster, colored in blue, portrays aspirations for a greener future, spotlighting the importance of energy transition and optimization and smart mobility solutions. This cluster delves into innovations such as Electric Vehicles (EVs) and their corresponding infrastructures, highlighting opportunities for city-wide transformation. Crucially, this cluster brings to the forefront the challenge of modern energy distribution the pivotal role of smart grids, and the nuances of balancing energy production, consumption, and trading in an ever-evolving urban environment.

The co-occurrence map reveals that the studies reviewed have addressed both positive prospects and concerns when it comes to integrating smart city tools and technologies into urban energy planning. However, positive and technocratic perspectives are prevalent rather than studies focused on addressing social concerns and obstacles. Critical social considerations, such as justice, public engagement, public trust, risks, public health, diversity, accessibility, and the digital divide are situated on the periphery of the network with smaller nodes and fewer connections to other nodes.

Figure 2 provides insights that confirm existing knowledge and open up new research directions. Some areas of the map show a high density of interconnected nodes, representing well-explored topics. However, there are other regions with relatively few connections, indicating areas that have not yet been extensively investigated. On the other hand, even within the highly connected clusters representing established fields of study, there may still be hidden gaps or unanswered questions that have gone unnoticed by mainstream academia.

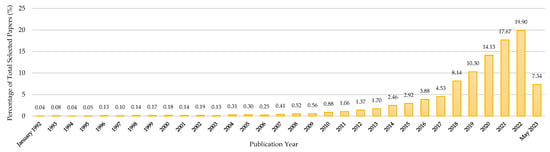

Figure 3 shows that 77.5% of the 9320 scholarly papers were published between 2018 and May 2023. The concentration on research efforts within these years underscores the value of the comprehensive review conducted in the next section. Therefore, when considering the entire time span from January 1992 to May 2023, Figure 2 and Figure 3 highlight both the significant development of the field and several prospects for further exploration.

Figure 3.

Annual distribution of 9320 selected papers by publication year.

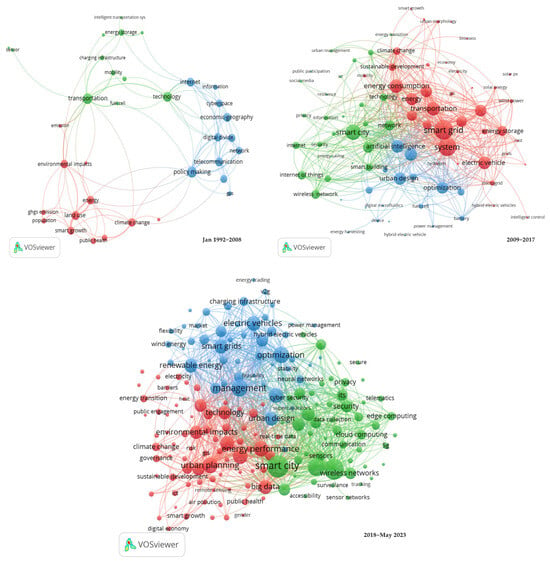

Guided by the VOSviewer co-occurrence maps for each period, as illustrated in Figure 4, our bibliometric analysis emphasizes the progressive evolution of the literature on smart cities and urban energy planning through three transformative periods. The initial period from 1992 to 2008 was formative, merging technology with sustainability and governance, and giving rise to the role of smart transportation within urban energy and environmental planning. Between 2009 and 2017, rapid technological growth was accompanied by the emergence of AI, energy storage, smart grids, and EVs. However, socioeconomic factors were often overlooked. The most recent phase, 2018 to 2023, has sought to redress this by harmonizing technological growth with economic and socio-ecological priorities, influenced by the imperatives of climate change, energy transition, social and environmental justice, the COVID-19 pandemic, and privacy and security concerns and marked by widespread developments in 5G, DT, IoT, blockchain, big data analytics, and machine learning, among others. As Figure 4 shows, despite these advancements, a notable gap persists between the literature focusing on the technical dimensions of smart cities and studies addressing the socioeconomic and environmental implications, indicating the need for a more balanced research approach.

Figure 4.

Evolving research trends in smart cities and urban energy planning: A three-period keywords co-occurrence analysis.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This conducted review showed that the energy performance of the building sector is transforming through the integration of technologies such as AI, DT, IoT, IoE, and RE sources in building design and construction [45,59,60]. These same technologies find application in urban planning and design, forming a synergy with passive measures to enhance energy efficiency. The deployment of IoT devices, remote sensing, GIS, and AI algorithms provides a unified approach, allowing for the optimization of RE harvesting, spatial planning, UHI mitigation, and energy demand prediction [50,82,85,94]. This emphasizes the interconnectedness of buildings and urban design and planning, showcasing the seamless integration of energy efficiency from individual buildings to the urban landscape. In the realm of smart transportation and mobility, technologies such as ITS, IoT-enabled solutions, V2G, and EVs represent a broader application of intelligent systems and technologies [106,123,124,145]. Grid modernization and smart grids mark the convergence of these initiatives. Enhanced with IoT devices and other smart technologies, smart grids increase control, predictive capabilities, and energy efficiency while fostering decentralized systems, energy storage, and RE integration [174,176,184,186,187].

These technological advancements are posited by some to be pivotal in empowering cities to predict, prepare for, and mitigate risks in real-time, turning reactive measures into proactive strategies, and fostering a resilient and sustainable future. Over the last three decades, a multitude of urban development concepts have emerged, inspired by the promising aspects of smart cities as illustrated in Figure 5. These initiatives are driven by the goal of transforming communities and urban areas into entities that are energy-efficient and carbon-neutral. This movement has given rise to an array of concepts and models, such as Smart Eco-City, Eco2 City, Ubiquitous Eco-City, Low Carbon City, Carbon Neutral City, Net Zero Carbon Community, Zero Carbon City, Low Energy District, Nearly Zero Energy Neighborhood, Zero Energy Community, Positive Energy Blocks, and ultimately, Positive Energy Districts (PEDs) [205,206]. Underpinned by these models, numerous smart city-based projects have been implemented or are in the planning stages globally. A notable example is the European Commission’s objective to have 100 PEDs either planned, developed, or established by 2025 [207]. In the context of these varied and ambitious initiatives, a critical question arises: Why do some smart city projects, despite rapid technological advancements, struggle to consistently achieve energy efficiency and carbon emission reduction goals [105], while others succeed [206]?

Figure 5.

Mapping urban energy to smart city: An overview of promises and challenges.

Prior to addressing the aforementioned question, it is instructive to examine the definition of PEDs as outlined in the European “SET Plan Action 3.2 Smart Cities and Communities Implementation Plan [208].” PEDs encompass the integration of electric vehicles, advanced materials, local RE sources, local storage, smart energy grids, demand response, user interaction and involvement, ICT, and participatory energy management strategies in order to showcase a future where cities not only consume energy but also generate, store, and sustainably manage it [208]. In fact, the emergence of PEDs and other smart city-based concepts unfolds as a multidimensional transformation that not only emphasizes the technical and technological aspects but also implementation, performance evaluation, and management policies [105,205]. While there are multiple factors contributing to the varying success of smart city projects, one potential answer to the third question of this paper is the possible oversight of well-developed policies and regulations, which is a principal contributor to the challenges illustrated in Figure 5. Although some of these challenges are technical and technological in nature, more than half span across four dimensions and are directly linked to the absence of rigorous policies and regulations. These cross-cutting issues are pervasive, highlighting the imperative for a holistic and coordinated framework that addresses not only technical solutions but also policy and regulatory strategies.

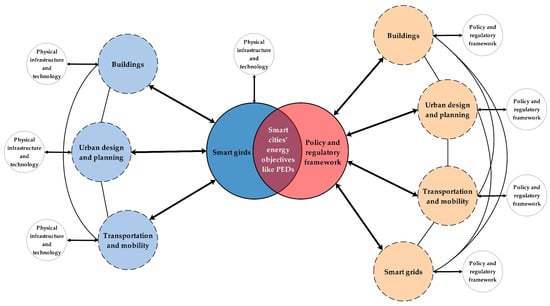

If we conceptualize the four technical dimensions as the foundational infrastructure of the smart city and urban energy planning nexus, smart grids can be thought of as the central nervous system, interconnecting and coordinating these dimensions [209]. On the other hand, policy and regulatory frameworks act as the decision-making algorithms or central processing units that guide the operations. Without these guiding mechanisms, the system risks operational inefficiency, misalignment of goals, and potential failure in achieving smart cities’ energy and emission reduction objectives [204]. Referring to the conceptual framework presented in Figure 6, enhancing physical infrastructure and technologies is still imperative for optimizing the energy performance of each dimension. This not only involves individual improvements but also their integration and connection to boost their collective efficacy. Concurrently, each dimension demands specialized policies and regulations, necessitating an overarching policy assemblage that comprehensively addresses all four dimensions. This holistic approach ensures improvements not just in energy performance, but also across environmental, socioeconomic, and other technical facets.

Figure 6.

Conceptual framework of the ideal smart city and urban energy planning nexus.

Should smart cities aspire to effectively confront the existing and anticipated challenges in the forthcoming years, strict adherence to the outlined framework becomes crucial. Urban centers are expected to face unprecedented pressures from these global concerns, alongside other emerging uncertainties. In this context, the role of smart cities, especially in the energy sector, emerges as a critical factor in driving sustainable urban energy transitions and climate resilience. This underscores the importance of smart cities as proactive agents in navigating and mitigating the complexities of our evolving environmental landscape [6,86,210]. Therefore, to successfully navigate this endeavor, the next wave of smart city evolution should emphasize an integrative approach developed based on established policies that are flexible, adaptable, and forward-thinking. These policies and regulations should set the stage for a judicious amalgamation of technological prowess with overarching societal and environmental imperatives. In this unfolding chapter, the ultimate success of smart city initiatives will not only hinge on energy efficiency and climate change mitigation and adaptation but also on the ability to embed technology within socially responsive, economically viable, and environmentally sustainable frameworks [28,210].

5.1. Emerging Trends and Concerns

Our review has highlighted a predominant focus within the smart cities literature on leveraging advanced technology systems to achieve broad-based energy use reductions and sustainable energy deployment. However, this emphasis has often been at the expense of fully addressing socioeconomic and environmental considerations. Furthermore, our bibliometric analysis, coupled with insights from recent papers, has revealed key predictions about the future trajectory of research in this domain:

- (1)

- Trend predictions in the realm of smart cities indicate an expected surge in research focusing on the reciprocal impact between smart city initiatives and the environment. It is anticipated that future studies will delve deeper into understanding how these initiatives can positively influence the environment. This includes exploring the potential for reducing GHG emissions and mitigating UHI effects through the implementation of energy-efficient, solar-powered smart cities [10,211,212]. Additionally, there will likely be a growing emphasis on understanding the adverse environmental impacts of smart technologies, including the ecological footprint of their entire lifecycle, from resource extraction to E-waste disposal [213]. Concurrently, research is expected to intensify in exploring how environmental and climate changes affect smart cities [214]. This includes examining the resilience of smart infrastructures against extreme weather conditions and their capacity to adapt to changing environmental dynamics. Such research could lead to innovations in developing more robust and climate-adaptive smart cities. This dual focus on the interaction between smart cities and their environmental context is poised to play a pivotal role in informing sustainable policy development, energy management, and resilient urban planning in the face of ongoing climatic and environmental shifts [211,212,214].

- (2)

- Socioeconomic justice and inclusion are rapidly gaining attention as key areas of research in smart city development, emphasizing the need for equitable access to energy efficiency and other benefits for all societal segments, particularly marginalized communities [32]. This growth in focus is driven by the recognition that certain populations within digital societies are becoming marginalized due to a lack of technological literacy or economic means, limiting their access to the benefits that smart cities offer [215]. Additionally, it is crucial to ensure that not only the benefits but also any adverse impacts of smart city developments are equally distributed, rather than disproportionately affecting low-income and disadvantaged communities [34,107,188,189]. Research in this area includes exploring mechanisms to ensure the fair distribution of smart city benefits, such as access to green, reliable, and affordable energy, as well as energy-saving technologies and programs [32,191,216]. The goal is to make sustainable energy systems truly inclusive, addressing the disparities in the distribution of incentives and burdens, and ensuring that the advancements in smart cities do not exacerbate existing social inequalities. This concern is increasingly pressing as smart city initiatives advance, highlighting the need for deliberate and targeted strategies to bridge the digital divide and foster a more equitable urban future.

- (3)

- The emerging trend in smart city research is the re-imagination of technology-energy-society relations, with a focus on enhancing public engagement [217]. This approach advocates for the development of smart technologies that not only promote transparency, accountability, and citizen participation but also address privacy and security concerns. Such concerns have been a major barrier to the successful implementation of smart city projects, as hesitancy to participate is often due to a lack of trust. Overcoming these apprehensions is critical for fostering meaningful public engagement [218]. Key to this effort is ensuring the safety and security of citizen data and the accountability of smart technologies. It is essential to involve citizens in decision-making processes, particularly through bottom-up approaches, and to enhance transparency in both the development and management of these projects [219]. Furthermore, educational initiatives that align citizen behavior with energy efficiency objectives are gaining importance [220]. These steps are vital for building trust, fostering community ownership, and making smart city projects more attuned to the needs of their residents.

- (4)

- Future research in the field of smart cities is anticipated to increasingly focus on two interconnected technical and implementation complexities: the integration of advanced technologies, such as 5G and 6G, into urban energy frameworks, and the technical aspects of privacy and security within these complex systems [45,63,65,193,200,201]. This shift reflects a growing need to understand and resolve the challenges of system interoperability, particularly in the context of global technology transfer. This involves navigating a range of financial, geopolitical, and skill-related issues [220]. A critical aspect of this research will be to enhance the technical resilience of smart city infrastructures against cyberattacks. This includes advancing robust methodologies for ensuring data privacy and maintaining the integrity of energy management systems [45,200,201]. Such research is essential for the development of secure and efficient smart city environments, where the technical safeguarding of information and infrastructure is as crucial as the physical and social dimensions of urban living. By holistically addressing both the integration of cutting-edge technologies and the technical safeguards necessary for security and privacy, future research endeavors are set to significantly impact the design, policy-making, and operational efficacy of smart cities.

5.2. Rethinking Policies and Regulations

The emerging trends and concerns in smart city research highlight the urgent need to reevaluate policy and regulatory frameworks, especially as existing ones may not adequately address the systemic dimensions inherent in smart city development and urban energy planning. This necessitates a shift towards a more integrative approach, one that not only embraces technological advancements but also weaves in considerations of socioeconomic justice, environmental impact, and public engagement. Such an approach recognizes the intricate tapestry of interests among various stakeholders—including governments, urban authorities, residents, investors, and businesses—and underscores the importance of a collaborative approach. Engaging practitioners, policymakers, and academics in dialogue and development is crucial for formulating comprehensive policy and regulatory frameworks that can navigate the promises and challenges of smart cities [221,222].

However, a significant challenge lies in the disparity between rapid technological advancements and slow policy development and performance evaluation. This gap calls for research into the creation of adaptive and responsive policy and regulatory frameworks [204]. Research in this domain should focus on designing policies that are both flexible and robust, capable of keeping pace with technological changes while ensuring effective governance and oversight. Delving into the interplay between emerging technologies and existing legal structures is essential, offering insights into areas where conflict may arise and identifying opportunities for harmonization [191,192]. This line of inquiry is vital to ensure that technological advancements are steered responsibly, benefiting society and the environment.

Acknowledging the dual impact of smart city initiatives on societal and ecological contexts underscores the importance of measurable outcomes in urban energy planning. This recognition necessitates a shift in policy and regulation to not only keep pace with technological innovation but also ensure social and environmental responsibility. In a field marked by uncertainties, like smart cities, every decision carries its own set of trade-offs. Therefore, it is imperative that policies and regulations are designed to accurately measure these trade-offs, enabling a balanced and informed approach to decision-making. Such frameworks are essential for ensuring that smart city initiatives are not only technologically advanced but also aligned with the comprehensive needs of urban energy systems, optimizing outcomes while addressing new challenges and maintaining a commitment to societal and environmental well-being [19,223].

5.3. Moving beyond This Review

This review provides a foundational synthesis of smart cities in the context of energy and climate objectives, yet it also opens avenues for further exploration. Building upon the insights gained, there is a significant opportunity for expanding the research into detailed case studies of smart cities globally. Such an expansion is not only desirable but necessary to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the performance metrics of smart cities, particularly in terms of their energy efficiency and climate mitigation achievements. Future research could enrich this domain by undertaking comparative analyses of diverse smart city projects and initiatives. This would involve an in-depth examination of the various dimensions discussed in Section 5.1.

Further research endeavors should aim to delineate the unique strategies and challenges encountered by smart cities, taking into account the various geographical, political, environmental, and socioeconomic landscapes they operate within. An area ripe for scholarly exploration involves examining the differential impacts of policy and regulatory frameworks, technological deployments, environmental, and urban planning, and administrative strategies on the progression of smart cities towards their defined energy efficiency and emission reduction targets. A critical analysis of how smart cities have formulated and implemented adaptation and mitigation policies to overcome their faced challenges, and the extent to which these policies have been successful or unsuccessful, is crucial. This analysis should also consider the reasons behind these outcomes, thereby providing a nuanced understanding of the efficacy of smart city initiatives [105,206,224].

Such scholarly inquiries are not only paramount in enhancing our comprehension of the role and effectiveness of policy and regulatory frameworks within the context of smart cities but also crucial in assessing their broader impact on achieving sustainability objectives. This would significantly enrich the discourse on smart cities, providing a foundation for future policy formulation and implementation strategies aimed at optimizing urban environments for energy efficiency and climate resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E., S.T., J.B. and J.T.; methodology, S.E., S.T., G.G. and S.A.A.; software, S.E. and S.T.; validation, S.E., S.T., J.B. and J.T.; resources, S.E., S.T., J.B. and J.T.; data curation, S.T., G.G. and S.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E., S.T. and J.T.; writing—review and editing, J.B. and J.T.; visualization, S.E., S.T., G.G. and S.A.A.; supervision, S.E. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Renewable Energy and Environment (FREE), New York City, NY 10111, USA.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Seyed Ali Alavi was employed by the company Tehran Sewerage Company. The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PRISMA-ScR | PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| RE | Renewable Energy |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| RS | Remote Sensing |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoE | Internet of Energy |

| IoV | Internet of Vehicles |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation System |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| DSM | Demand-side Management |

| UHI | Urban Heat Island |

| E-waste | Electronic Waste |

| EVs | Electric Vehicles |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid |

| PEDs | Positive Energy Districts |

Appendix A

Limitations of Study

While reviewing studies conducted on smart cities and urban energy planning, encompassing its technological, environmental, transportation, and socioeconomic dimensions, we encountered some limitations. Primarily, we grapple with the inherent challenges of selecting pertinent studies and the unavoidable subjectivity infused in data extraction, interpretation, and analysis, inherent to any qualitative review [36]. With transparency at the forefront of the data and paper selection phase, we meticulously detailed our search string, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the databases employed (WoS), striving for a comprehensive sweep of the relevant literature. Nevertheless, the confines of our established parameters might have resulted in omitting pertinent research, those newly published (after May 2023), inaccessible through our database, or research nestled within specialized reports, policy briefs, professional and practical documents, and other non-academic literature. Therefore, as our review draws predominantly from academic journals, it is conceivable that practical insights or novel strategies from non-academic sectors, including urban policymakers or industry innovators, have been underrepresented.

Regarding subjectivity in data analysis, we used our own analytical categorization and interpretation framework, which inevitably influenced our analysis and findings. The specific framing and design of our review may also be incomplete, potentially leaving out important analytical constructs and categories. The bibliometric review focused on papers published between January 1992 and May 2023. However, the majority of the selected papers for the in-depth review are sourced from the last 5–10 years. This emphasis is reasonable due to the substantial volume of recent publications and the importance of reviewing and analyzing current knowledge and research findings. Moreover, the deployment of VOSviewer software, pivotal for our bibliometric analysis, brings its inherent constraints to keyword extraction and semantic apprehension, potentially curtailing nuanced interpretations. Additionally, although Section 4 focuses on five key dimensions and thoroughly investigates their promising and challenging sides, there might be emerging or niche topics, technological advancements, or other challenges, concerns, and barriers that were not covered throughout this review.

To overcome these limitations, we developed a comprehensive research protocol that includes explicit review questions, well-established search strings, and criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Our approach adheres to the checklist requirements for PRISMA-ScR analyses and provides justification for the decisions made at each stage of the review process. Four authors independently evaluated both search strings and results before reaching a consensus collectively to mitigate subjectivity during paper selection. To minimize the possibility of excluding relevant studies, we extensively included and scrutinized a substantial number of papers (193 records), far surpassing what is typically seen in other existing reviews in this field. Moreover, in the initial phase of the review, we identified and utilized 19 highly relevant reports and documents (Appendix B). These sources helped define our search strings and informed our recommendations for future research. This approach was necessary because smart cities and urban energy planning are not simply academic concepts; to effectively integrate smart city initiatives into improving urban energy profiles, it is crucial to establish a mutually beneficial relationship between theory and practice.

Appendix B

Table A1.

The list of reviewed non-peer-reviewed documents and reports.

Table A1.

The list of reviewed non-peer-reviewed documents and reports.

| # | Organization | Documents | # | Organization | Documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | European Commission | 1-Summary Report on Urban Energy Planning: Potentials and Barriers in Six Cities 2-Strategic Energy Technology (SET) Plan ACTION n°3.2 Implementation Plan 3-Digitalization in Urban Energy Systems: Outlook 2025, 2030 and 2040 | 8 | MIT SENSEABLE CITY LAB projects | 12-The Smart Enough City: Putting Technology in Its Place to Reclaim Our Urban Future |

| 2 | International Energy Agency (IEA) | 4-Digitalization & Energy 5-Energy Technology Perspectives 2023 6-Empowering Cities for a Net Zero Future: Unlocking Resilient, Smart, Sustainable Urban Energy Systems | 9 | Arup | 13-Five Minute Guide: Energy in Cities |

| 3 | United Nations University, UNU-EGOV, International Development Research Centre Canada (IDRC) | 7-Smart Sustainable Cities—Reconnaissance Study | 10 | IBM Institute for Business Value Executive Report | 14-Smarter Cities for Smarter Growth |

| 4 | European Parliament | 8-Digital Agenda for Europe | 11 | ASEAN Smart Cities Network and ASEAN Secretariat (ASEC) | 15-ASEAN Smart Cities Planning Guidebook |

| 5 | American Public Power Association | 9-Creating a Smart City Roadmap for Public Power Utilities | 12 | OECD | 16-Measuring smart cities’ performance: Do smart cities benefit everyone? 17-Enhancing the Contribution of Digitalization to the Smart Cities of the Future |

| 6 | International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) | 10-World Energy Transitions Outlook 2023: 1.5 °C Pathway | 13 | World Economic Forum | 18-Electric Vehicles for Smarter Cities: The Future of Energy and Mobility |

| 7 | C40 CITIES Climate Leadership Group | 11–10 Climate Challenges & Plenty of Solutions | 14 | Deloitte | 19-Renewables (em)power smart cities |

References

- Pérez, J.; Lázaro, S.; Lumbreras, J.; Rodríguez, E. A Methodology for the Development of Urban Energy Balances: Ten Years of Application to the City of Madrid. Cities 2019, 91, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M.; Politis, C.; Panori, A.; Bakratsas, T.; Fellnhofer, K. Emerging Smart City, Transport and Energy Trends in Urban Settings: Results of a Pan-European Foresight Exercise with 120 Experts. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 183, 121915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, Z.; Efremochkina, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. Study on City Digital Twin Technologies for Sustainable Smart City Design: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Geographic Information System and Building Information Modeling Integration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi Moghadam, S.; Delmastro, C.; Corgnati, S.P.; Lombardi, P. Urban Energy Planning Procedure for Sustainable Development in the Built Environment: A Review of Available Spatial Approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 165, 811–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Yamagata, Y. Principles and Criteria for Assessing Urban Energy Resilience: A Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1654–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Moriarty, P. Energy Savings from Smart Cities: A Critical Analysis. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 3271–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban and Transport Planning Pathways to Carbon Neutral, Liveable and Healthy Cities; A Review of the Current Evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, C. Towards a Secure and Resilient All-Renewable Energy Grid for Smart Cities. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2022, 11, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, Z.; Alsamara, M.; Saleh, A.S.; Anwar, S. Urbanization and Non-Renewable Energy Demand: A Comparison of Developed and Emerging Countries. Energy 2019, 170, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Taminiau, J.; Seo, J.; Lee, J.; Shin, S. Are Solar Cities Feasible? A Review of Current Research. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2017, 21, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Hughes, K.; Toly, N.; Wang, Y.-D. Can Cities Sustain Life in the Greenhouse? Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2006, 26, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nik, V.M.; Perera, A.T.D.; Chen, D. Towards Climate Resilient Urban Energy Systems: A Review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwaa134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammen, D.M.; Sunter, D.A. City-Integrated Renewable Energy for Urban Sustainability. Science 2016, 352, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E. Eco-Districts and Data-Driven Smart Eco-Cities: Emerging Approaches to Strategic Planning by Design and Spatial Scaling and Evaluation by Technology. Land Use Policy 2022, 113, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfandi, S.; Rahmdel, L.; Nourian, F.; Sharifi, A. The Role of Urban Spatial Structure in Energy Resilience: An Integrated Assessment Framework Using a Hybrid Factor Analysis and Analytic Network Process Model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, P.; Jomehzadeh, F.; Taheri, M.M.; Gohari, M.; Majid, M.Z.A. A Global Review of Energy Consumption, CO2 Emissions and Policy in the Residential Sector (with an Overview of the Top Ten CO2 Emitting Countries). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanon, B.; Verones, S. Climate Change, Urban Energy and Planning Practices: Italian Experiences of Innovation in Land Management Tools. Land Use Policy 2013, 32, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajot, S.; Peter, M.; Bahu, J.-M.; Koch, A.; Maréchal, F. Energy Planning in the Urban Context: Challenges and Perspectives. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 3366–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarstad, H.; Wathne, M.W. Are Smart City Projects Catalyzing Urban Energy Sustainability? Energy Policy 2019, 129, 918–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, H.; Kang, H.; An, J.; Yeom, S.; Hong, T. A Systematic Review of the Smart Energy Conservation System: From Smart Homes to Sustainable Smart Cities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahad, M.A.; Paiva, S.; Tripathi, G.; Feroz, N. Enabling Technologies and Sustainable Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 61, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. Smart Energy Transition: An Evaluation of Cities in South Korea. Informatics 2019, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herath, H.M.K.K.M.B.; Mittal, M. Adoption of Artificial Intelligence in Smart Cities: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2022, 2, 100076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, P.; Saravanan, S.; Usha, K.; Kannadasan, R.; Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, M.-K. Technological Advancements toward Smart Energy Management in Smart Cities. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 648–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T. Smart Cities: An Effective Urban Development and Management Model? Aust. Plan. 2015, 52, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Severino, A.; Al-Rashid, M.A.; Pau, G. The Development of the Smart Cities in the Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs) Era: From Mobility Patterns to Scaling in Cities. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Pham, V.V.; Nguyen, X.P. Integrating Renewable Sources into Energy System for Smart City as a Sagacious Strategy towards Clean and Sustainable Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, E.; Pan, I.; Acha, S.; Shah, N. Smart Energy Systems for Sustainable Smart Cities: Current Developments, Trends and Future Directions. Appl. Energy 2019, 237, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Agarwal, N.; Kar, A.K. Addressing Big Data Challenges in Smart Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. INFO 2016, 18, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naphade, M.; Banavar, G.; Harrison, C.; Paraszczak, J.; Morris, R. Smarter Cities and Their Innovation Challenges. Computer 2011, 44, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrisano, O.; Bartolini, I.; Bellavista, P.; Boeri, A.; Bononi, L.; Borghetti, A.; Brath, A.; Corazza, G.E.; Corradi, A.; De Miranda, S.; et al. The Need of Multidisciplinary Approaches and Engineering Tools for the Development and Implementation of the Smart City Paradigm. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 738–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Sharifi, A. Toward a Societal Smart City: Clarifying the Social Justice Dimension of Smart Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 95, 104612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrachooto, S.; Horayangkura, V. Energy Efficient Innovation: Overcoming Financial Barriers. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoldi, P.; Economidou, M.; Palermo, V.; Boza-Kiss, B.; Todeschi, V. How to Finance Energy Renovation of Residential Buildings: Review of Current and Emerging Financing Instruments in the EU. WIREs Energy Environ. 2021, 10, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V. Research Synthesis as a Scientific Process. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 3–16. ISBN 978-1-61044-886-4. [Google Scholar]

- Birkle, C.; Pendlebury, D.A.; Schnell, J.; Adams, J. Web of Science as a Data Source for Research on Scientific and Scholarly Activity. Quant. Sci. Stud. 2020, 1, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dameri, R.P.; Cocchia, A. Smart City and Digital City: Twenty Years of Terminology Evolution. In Proceedings of the X Conference of the Italian Chapter of AIS, ITAIS 2013, Milan, Italy, 14 December 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, D.V.; Kozmetsky, G.; Smilor, R.W. The Technopolis Phenomenon: Smart Cities, Fast Systems, Global Networks; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1992; ISBN 0-8476-7758-3. [Google Scholar]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. VOS: A New Method for Visualizing Similarities between Objects. In Advances in Data Analysis: Proceedings of the 30th annual conference of the German Classification Society; Decker, R., Lenz, H.-J., Eds.; Studies in classification, data analysis, and knowledge organization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 209–306. ISBN 978-3-540-70980-0. [Google Scholar]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software Survey: VOSviewer, a Computer Program for Bibliometric Mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, J.T.; Lennertz, L.; Atencio Mojica, Z. Mapping A Discipline: A Guide to Using VOSviewer for Bibliometric and Visual Analysis. Sci. Technol. Libr. 2022, 41, 319–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.V.; Zamora, M.A.; Skarmeta, A.F. User-Centric Smart Buildings for Energy Sustainable Smart Cities. Trans. Emerg. Tel. Technol. 2014, 25, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, H.; Malehmirchegini, L.; Bejan, A.; Afolabi, T.; Mulumba, A.; Daka, P.P. Artificial Intelligence Evolution in Smart Buildings for Energy Efficiency. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Lu, L. A Comprehensive Review on Passive Design Approaches in Green Building Rating Tools. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1425–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, C.E.; Capeluto, I.G. Strategic Decision-Making for Intelligent Buildings: Comparative Impact of Passive Design Strategies and Active Features in a Hot Climate. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1829–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergård, T.; Jensen, R.L.; Maagaard, S.E. Building Simulations Supporting Decision Making in Early Design—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, V.L.; Pisello, A.L.; Piselli, C.; Fabiani, C.; Cotana, F.; Santamouris, M. How Outdoor Microclimate Mitigation Affects Building Thermal-Energy Performance: A New Design-Stage Method for Energy Saving in Residential near-Zero Energy Settlements in Italy. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 920–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, S.; Gratia, E.; De Herde, A.; Hensen, J.L.M. Simulation-Based Decision Support Tool for Early Stages of Zero-Energy Building Design. Energy Build. 2012, 49, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteconi, A.; Polonara, F. Assessing the Demand Side Management Potential and the Energy Flexibility of Heat Pumps in Buildings. Energies 2018, 11, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, A.; Mohammadi, N.; Taylor, J.E. Smart City Digital Twin–Enabled Energy Management: Toward Real-Time Urban Building Energy Benchmarking. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04019045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwieduk, D.A. Towards Modern Options of Energy Conservation in Buildings. Renew. Energy 2017, 101, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondal, I.A.; Syed Athar, M.; Khurram, M. Role of Passive Design and Alternative Energy in Building Energy Optimization. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyik, E.; Araz, M.; Hepbasli, A.; Shahrestani, M.; Yao, R.; Shao, L.; Essah, E.; Oliveira, A.C.; Del Caño, T.; Rico, E.; et al. A Key Review of Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2017, 20, 833–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaygusuz, A.; Keles, C.; Alagoz, B.B.; Karabiber, A. Renewable Energy Integration for Smart Sites. Energy Build. 2013, 64, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralegaonkar, R.V.; Gupta, R. Review of Intelligent Building Construction: A Passive Solar Architecture Approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2238–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, S. Optimization of Passive Solar Design Strategies: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.M.; Boudreau, M.-C.; Helsen, L.; Henze, G.; Mohammadpour, J.; Noonan, D.; Patteeuw, D.; Pless, S.; Watson, R.T. Ten Questions Concerning Integrating Smart Buildings into the Smart Grid. Build. Environ. 2016, 108, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Irwin, D.; Shenoy, P.; Kurose, J.; Zhu, T. GreenCharge: Managing Renewable Energy in Smart Buildings. IEEE J. Select. Areas Commun. 2013, 31, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliero, M.S.; Asif, M.; Ghani, I.; Pasha, M.F.; Jeong, S.R. Systematic Review Analysis on Smart Building: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Zheng, L.-Q.; Xie, B.-C.; Mahalingam, A. Barriers to the Adoption of Energy-Saving Technologies in the Building Sector: A Survey Study of Jing-Jin-Tang, China. Energy Policy 2014, 75, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, U.; Abbasi, U.; Mir, T.; Kanwal, S.; Alamri, S. Energy Management in Smart Buildings and Homes: Current Approaches, a Hypothetical Solution, and Open Issues and Challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 94132–94148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, R.; Stephenson, P.; Morrey, D. Digital Construction: From Point Solutions to IoT Ecosystem. Autom. Constr. 2018, 93, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliero, M.S.; Qureshi, K.N.; Pasha, M.F.; Ghani, I.; Yauri, R.A. Systematic Mapping Study on Energy Optimization Solutions in Smart Building Structure: Opportunities and Challenges. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2021, 119, 2017–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkse, J.; Dommisse, M. Overcoming Barriers to Sustainability: An Explanation of Residential Builders’ Reluctance to Adopt Clean Technologies. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2009, 18, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaghraby, A.S.; Losavio, M.M. Cyber Security Challenges in Smart Cities: Safety, Security and Privacy. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 5, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaço, F.M.D.A.; Simoes, S.G.; Dias, L.P.; Duic, N.; Seixas, J.; Bermann, C. The Dawn of Urban Energy Planning—Synergies between Energy and Urban Planning for São Paulo (Brazil) Megacity. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 458–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, O.; Ho Dac, D.; Boudou, P.; Kayal, M. Cooperative Energy Management of a Community of Smart-Buildings: A Blockchain Approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 117, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zhu, Q.; Yu, N. Proactive Demand Participation of Smart Buildings in Smart Grid. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2016, 65, 1392–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Wu, D.; Lian, J.; Yang, T. Optimal Coordination of Building Loads and Energy Storage for Power Grid and End User Services. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 9, 4335–4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcin, M.; Kaygusuz, A.; Karabiber, A.; Alagoz, S.; Alagoz, B.B.; Keles, C. Opportunities for Energy Efficiency in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Istanbul Smart Grid Congress and Fair (ICSG), Istanbul, Turkey, 20–21 April 2016; IEEE: Istanbul, Turkey, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Futcher, J.A.; Mills, G. The Role of Urban Form as an Energy Management Parameter. Energy Policy 2013, 53, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzino, A.; Osello, A.; Patti, E.; Bottaccioli, L.; Danna, C.; Lingua, A.; Acquaviva, A.; Macii, E.; Grosso, M.; Messina, G.; et al. The Energy Efficiency Management at Urban Scale by Means of Integrated Modelling. Energy Procedia 2015, 83, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, L.; Bruse, M.; Meng, Q. An Integrated Simulation Method for Building Energy Performance Assessment in Urban Environments. Energy Build. 2012, 54, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, I.; Pucar, M.; Kovačević, B. Reducing the Impact of Climate Change by Applying Information Technologies and Measures for Improving Energy Efficiency in Urban Planning. Energy Build. 2016, 115, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainzer, K.; Killinger, S.; McKenna, R.; Fichtner, W. Assessment of Rooftop Photovoltaic Potentials at the Urban Level Using Publicly Available Geodata and Image Recognition Techniques. Sol. Energy 2017, 155, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, R.; Gagnon, P.; Melius, J.; Phillips, C.; Elmore, R. Using GIS-Based Methods and Lidar Data to Estimate Rooftop Solar Technical Potential in US Cities. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 074013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukač, N.; Seme, S.; Žlaus, D.; Štumberger, G.; Žalik, B. Buildings Roofs Photovoltaic Potential Assessment Based on LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) Data. Energy 2014, 66, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Taminiau, J.; Kurdgelashvili, L.; Kim, K.N. A Review of the Solar City Concept and Methods to Assess Rooftop Solar Electric Potential, with an Illustrative Application to the City of Seoul. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 830–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taminiau, J.; Byrne, J. City-scale Urban Sustainability: Spatiotemporal Mapping of Distributed Solar Power for New York City. WIREs Energy Environ. 2020, 9, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, A.M.; Domínguez, J.; Amador, J. Applying LIDAR Datasets and GIS Based Model to Evaluate Solar Potential over Roofs: A Review. AIMS Energy 2015, 3, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngie, A.; Abutaleb, K.; Ahmed, F.; Darwish, A.; Ahmed, M. Assessment of Urban Heat Island Using Satellite Remotely Sensed Imagery: A Review. South Afr. Geogr. J. 2014, 96, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafoni, S.; Baldinelli, G.; Verducci, P. Sustainable Strategies for Smart Cities: Analysis of the Town Development Effect on Surface Urban Heat Island through Remote Sensing Methodologies. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 29, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, H.; Cartalis, C.; Kolokotsa, D.; Muscio, A.; Pisello, A.L.; Rossi, F.; Santamouris, M.; Synnef, A.; Wong, N.H.; Zinzi, M. Local Climate Change and Urban Heat Island Mitigation Techniques—The State of the Art. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2015, 22, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, C.F.; Sánchez-Miralles, A.; Villar, J. Energy Management and Planning in Smart Cities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TAO, W. Interdisciplinary Urban GIS for Smart Cities: Advancements and Opportunities. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 16, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papyshev, G.; Yarime, M. Exploring City Digital Twins as Policy Tools: A Task-Based Approach to Generating Synthetic Data on Urban Mobility. Data Policy 2021, 3, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Kavousi-Fard, A.; Chen, T.; Karimi, M. A Review on Digital Twin Technology in Smart Grid, Transportation System and Smart City: Challenges and Future. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 17471–17484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, F.T.; Brown, N.C.; Duarte, J.P. A Grammar-Based Optimization Approach for Designing Urban Fabrics and Locating Amenities for 15-Minute Cities. Buildings 2022, 12, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Bibri, S.E.; Jones, D.S.; Chabaud, D.; Moreno, C. Unpacking the ‘15-Minute City’ via 6G, IoT, and Digital Twins: Towards a New Narrative for Increasing Urban Efficiency, Resilience, and Sustainability. Sensors 2022, 22, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozoukidou, G.; Angelidou, M. Urban Planning in the 15-Minute City: Revisited under Sustainable and Smart City Developments until 2030. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 1356–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, S.; Fan, L.; Suzuki, Y. Assessment of Urban Energy Performance through Integration of BIM and GIS for Smart City Planning. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jiang, L.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Y. Intelligent Edge Computing for IoT-Based Energy Management in Smart Cities. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekić-Sušac, M.; Mitrović, S.; Has, A. Machine Learning Based System for Managing Energy Efficiency of Public Sector as an Approach towards Smart Cities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 102074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sivaparthipan, C.B.; Muthu, B. IoT Based Smart and Intelligent Smart City Energy Optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 49, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.P.; Merrett, G.V.; Weddell, A.S.; White, N.M. A Traffic-Aware Street Lighting Scheme for Smart Cities Using Autonomous Networked Sensors. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2015, 45, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcholtchev, N.; Schieferdecker, I. Sustainable and Reliable Information and Communication Technology for Resilient Smart Cities. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 156–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puron-Cid, G.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Are Smart Cities Too Expensive in the Long Term? Analyzing the Effects of ICT Infrastructure on Municipal Financial Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Kim, K.-J.; Maglio, P.P. Smart Cities with Big Data: Reference Models, Challenges, and Considerations. Cities 2018, 82, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.-Y.; Kim, D.; Chun, S.A. Digital Divide in Advanced Smart City Innovations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, U.; Sengupta, U. Why Government Supported Smart City Initiatives Fail: Examining Community Risk and Benefit Agreements as a Missing Link to Accountability for Equity-Seeking Groups. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 960400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R.; Sharifi, A.; Sadeghi, A. The 15-Minute City: Urban Planning and Design Efforts toward Creating Sustainable Neighborhoods. Cities 2023, 132, 104101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.C.J.M.; Ju Choi, C. Development and Knowledge Resources: A Conceptual Analysis. J. Knowl. Manag. 2010, 14, 759–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Han, H.; Kamruzzaman, M.; Ioppolo, G.; Sabatini-Marques, J. The Making of Smart Cities: Are Songdo, Masdar, Amsterdam, San Francisco and Brisbane the Best We Could Build? Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh Bar Gai, D.; Shittu, E.; Attanasio, D.; Weigelt, C.; LeBlanc, S.; Dehghanian, P.; Sklar, S. Examining Community Solar Programs to Understand Accessibility and Investment: Evidence from the U.S. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daum, K.; Stoler, J.; Grant, R. Toward a More Sustainable Trajectory for E-Waste Policy: A Review of a Decade of E-Waste Research in Accra, Ghana. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šurdonja, S.; Giuffrè, T.; Deluka-Tibljaš, A. Smart Mobility Solutions—Necessary Precondition for a Well-Functioning Smart City. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 45, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Dameri, R.P.; D’Auria, B. Smart Mobility in Smart City: Action Taxonomy, ICT Intensity and Public Benefits. In Proceedings of the XI Conference of the Italian Chapter of AIS, ITAIS 2014, Genova, Italy, 21–22 November 2014; Empowering Organizations. Lecture Notes in Information Systems and Organisation. Torre, T., Braccini, A.M., Spinelli, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2016; Volume 11, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.W.; Uludag, S. Intelligent Transportation as the Key Enabler of Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2016-2016 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Istanbul, Turkey, 25–29 April 2016; IEEE: Istanbul, Turkey, 2016; pp. 1261–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, X.; Ghazzai, H.; Massoud, Y. Mobile Crowdsourcing for Intelligent Transportation Systems: Real-Time Navigation in Urban Areas. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 136995–137009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Din, S.; Paul, A.; Jeon, G.; Aloqaily, M.; Ahmad, M. Real-Time Route Planning and Data Dissemination for Urban Scenarios Using the Internet of Things. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2019, 26, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namoun, A.; Tufail, A.; Mehandjiev, N.; Alrehaili, A.; Akhlaghinia, J.; Peytchev, E. An Eco-Friendly Multimodal Route Guidance System for Urban Areas Using Multi-Agent Technology. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainetti, L.; Patrono, L.; Stefanizzi, M.L.; Vergallo, R. A Smart Parking System Based on IoT Protocols and Emerging Enabling Technologies. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 2nd World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Milan, Italy, 14–16 December 2015; IEEE: Milan, Italy, 2015; pp. 764–769. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Turjman, F.; Malekloo, A. Smart Parking in IoT-Enabled Cities: A Survey. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 49, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavhan, S.; Gupta, D.; Gochhayat, S.P.; Chandana, B.N.; Khanna, A.; Shankar, K.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Edge Computing AI-IoT Integrated Energy-Efficient Intelligent Transportation System for Smart Cities. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2022, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembski, F.; Wössner, U.; Letzgus, M.; Ruddat, M.; Yamu, C. Urban Digital Twins for Smart Cities and Citizens: The Case Study of Herrenberg, Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Fan, W.; Zeng, E.; Hang, Z.; Wang, F.; Qi, L.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.A. Digital Twin-Assisted Real-Time Traffic Data Prediction Method for 5G-Enabled Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2022, 18, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Jiao, H.; Niu, Q. An Agent-Based Model Simulation of Human Mobility Based on Mobile Phone Data: How Commuting Relates to Congestion. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, C.; Erath, A.; Fourie, P.J. Transport Modelling in the Age of Big Data. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2017, 21, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachanek, K.H.; Tundys, B.; Wiśniewski, T.; Puzio, E.; Maroušková, A. Intelligent Street Lighting in a Smart City Concepts—A Direction to Energy Saving in Cities: An Overview and Case Study. Energies 2021, 14, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.; Cano, J.; Kim, D. Predicting Traffic Lights to Improve Urban Traffic Fuel Consumption. In Proceedings of the 2006 6th International Conference on ITS Telecommunications, Chengdu, China, 21–23 June 2006; IEEE: Chengdu, China, 2006; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.-H.; Chiu, C.-Y. Design and Implementation of a Smart Traffic Signal Control System for Smart City Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dlugosch, O.; Brandt, T.; Neumann, D. Combining Analytics and Simulation Methods to Assess the Impact of Shared, Autonomous Electric Vehicles on Sustainable Urban Mobility. Inf. Manag. 2022, 59, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Bernal-Escobedo, L.; Santa, J. Eco-Efficient Mobility in Smart City Scenarios. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutar, S.H.; Koul, R.; Suryavanshi, R. Integration of Smart Phone and IOT for Development of Smart Public Transportation System. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Internet of Things and Applications (IOTA), Pune, India, 22–24 January 2016; IEEE: Pune, India, 2016; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski, R.; Pałka, P.; Turek, A. Solving “Smart City” Transport Problems by Designing Carpooling Gamification Schemes with Multi-Agent Systems: The Case of the So-Called “Mordor of Warsaw”. Sensors 2018, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palomares, J.C.; Gutiérrez, J.; Latorre, M. Optimizing the Location of Stations in Bike-Sharing Programs: A GIS Approach. Appl. Geogr. 2012, 35, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Jiao, J.; Wang, H. Estimating E-Scooter Traffic Flow Using Big Data to Support Planning for Micromobility. J. Urban Technol. 2022, 29, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnr, B.A. Integrating Electric Vehicles to Achieve Sustainable Energy as a Service Business Model in Smart Cities. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 685716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiebat, M.; Xu, M. Synergies of Four Emerging Technologies for Accelerated Adoption of Electric Vehicles: Shared Mobility, Wireless Charging, Vehicle-to-Grid, and Vehicle Automation. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 794–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbue, O.; Long, S. Barriers to Widespread Adoption of Electric Vehicles: An Analysis of Consumer Attitudes and Perceptions. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.K.; Devaraj, E.; Gopal, A. Overview of Wireless Charging and Vehicle-to-grid Integration of Electric Vehicles Using Renewable Energy for Sustainable Transportation. IET Power Electron. 2019, 12, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljohani, T.M.; Ebrahim, A.F.; Mohammed, O.A. Dynamic Real-Time Pricing Mechanism for Electric Vehicles Charging Considering Optimal Microgrids Energy Management System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Applicat. 2021, 57, 5372–5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmer, S.; Rodemann, T. Peak Load Reduction through Dynamic Pricing for Electric Vehicle Charging. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 113, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Kester, J.; Noel, L.; Zarazua De Rubens, G. Actors, Business Models, and Innovation Activity Systems for Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Technology: A Comprehensive Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 109963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-ibanez, J.A.; Zeadally, S.; Contreras-Castillo, J. Integration Challenges of Intelligent Transportation Systems with Connected Vehicle, Cloud Computing, and Internet of Things Technologies. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2015, 22, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A. Smooth Integration of Transport Infrastructure into Urban Space. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2021, 5, 1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwasilu, F.; Justo, J.J.; Kim, E.-K.; Do, T.D.; Jung, J.-W. Electric Vehicles and Smart Grid Interaction: A Review on Vehicle to Grid and Renewable Energy Sources Integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 34, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Awater, P.; Schafer, A.; Breuer, C.; Moser, A. Scenario-Based Evaluation on the Impacts of Electric Vehicle on the Municipal Energy Supply Systems. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, San Diego, CA, USA, 24–28 July 2011; IEEE: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Straub, F.; Streppel, S.; Göhlich, D. Methodology for Estimating the Spatial and Temporal Power Demand of Private Electric Vehicles for an Entire Urban Region Using Open Data. Energies 2021, 14, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vopava, J.; Koczwara, C.; Traupmann, A.; Kienberger, T. Investigating the Impact of E-Mobility on the Electrical Power Grid Using a Simplified Grid Modelling Approach. Energies 2019, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Kong, F.; Liu, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, Q. A Review on Electric Vehicles Interacting with Renewable Energy in Smart Grid. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, N.; Grijalva, S.; Chukwuka, V.; Vasilakos, A.V. Network Security and Privacy Challenges in Smart Vehicle-to-Grid. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2017, 24, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntafloukas, K.; McCrum, D.P.; Pasquale, L. A Cyber-Physical Risk Assessment Approach for Internet of Things Enabled Transportation Infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]