On the Adoption of Smart Home Technology in Switzerland: Results from a Survey Study Focusing on Prevention and Active Healthy Aging Aspects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. SH Service and Prevention Areas

2.2. Factors Influencing SH Adoption

2.3. User Characteristics

3. Methodology and Data

3.1. Survey Design and Data Collection

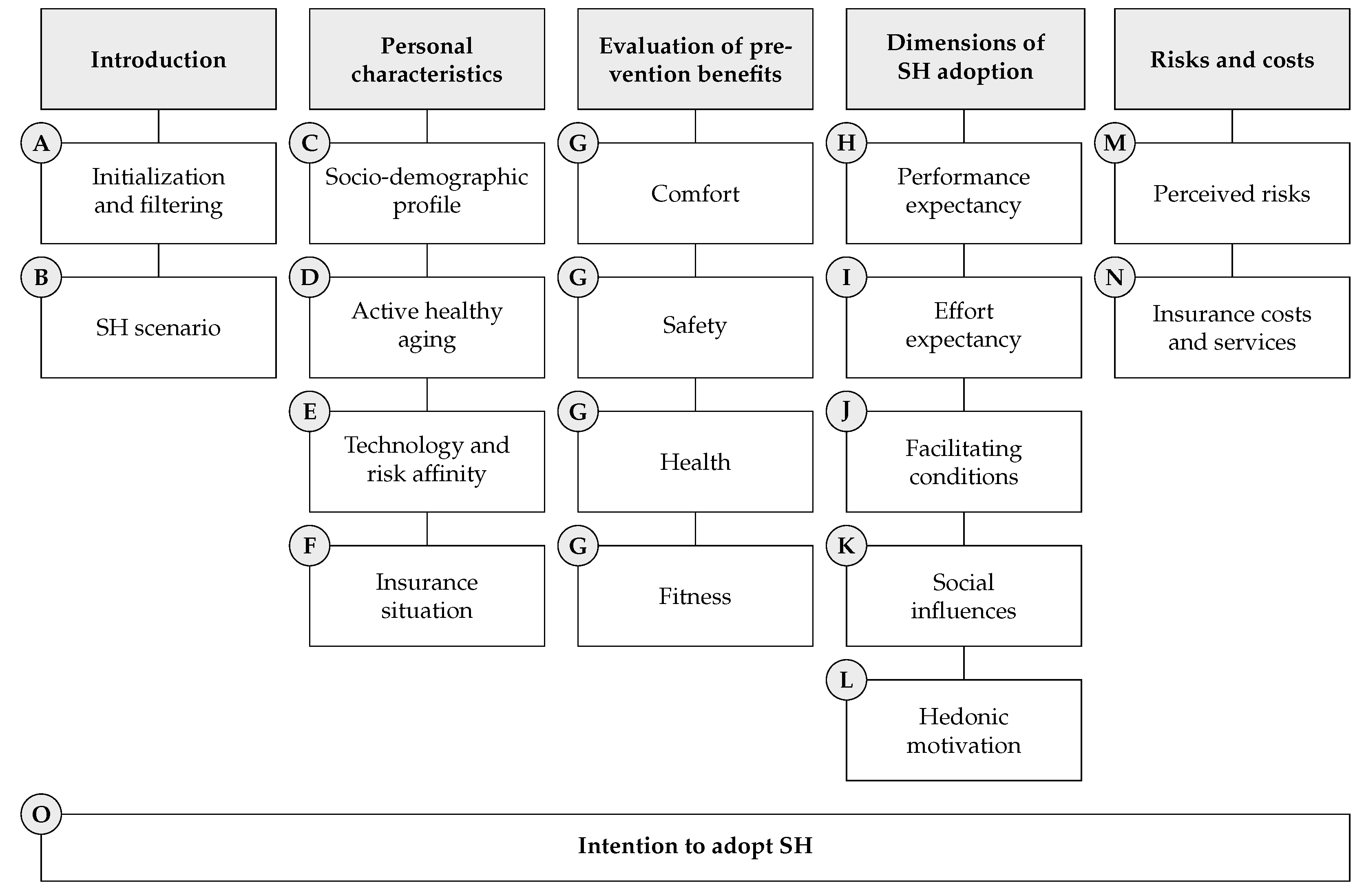

3.1.1. Structure

3.1.2. SH Scenario

3.1.3. Operationalization

3.1.4. Sample

3.2. Questions and Measurement Items

3.2.1. Intention to Adopt SH

3.2.2. Introduction

3.2.3. Personal Characteristics

3.2.4. Evaluation of Prevention Benefits

3.2.5. Dimensions of SH Adoption

3.2.6. Risks and Costs

4. Results

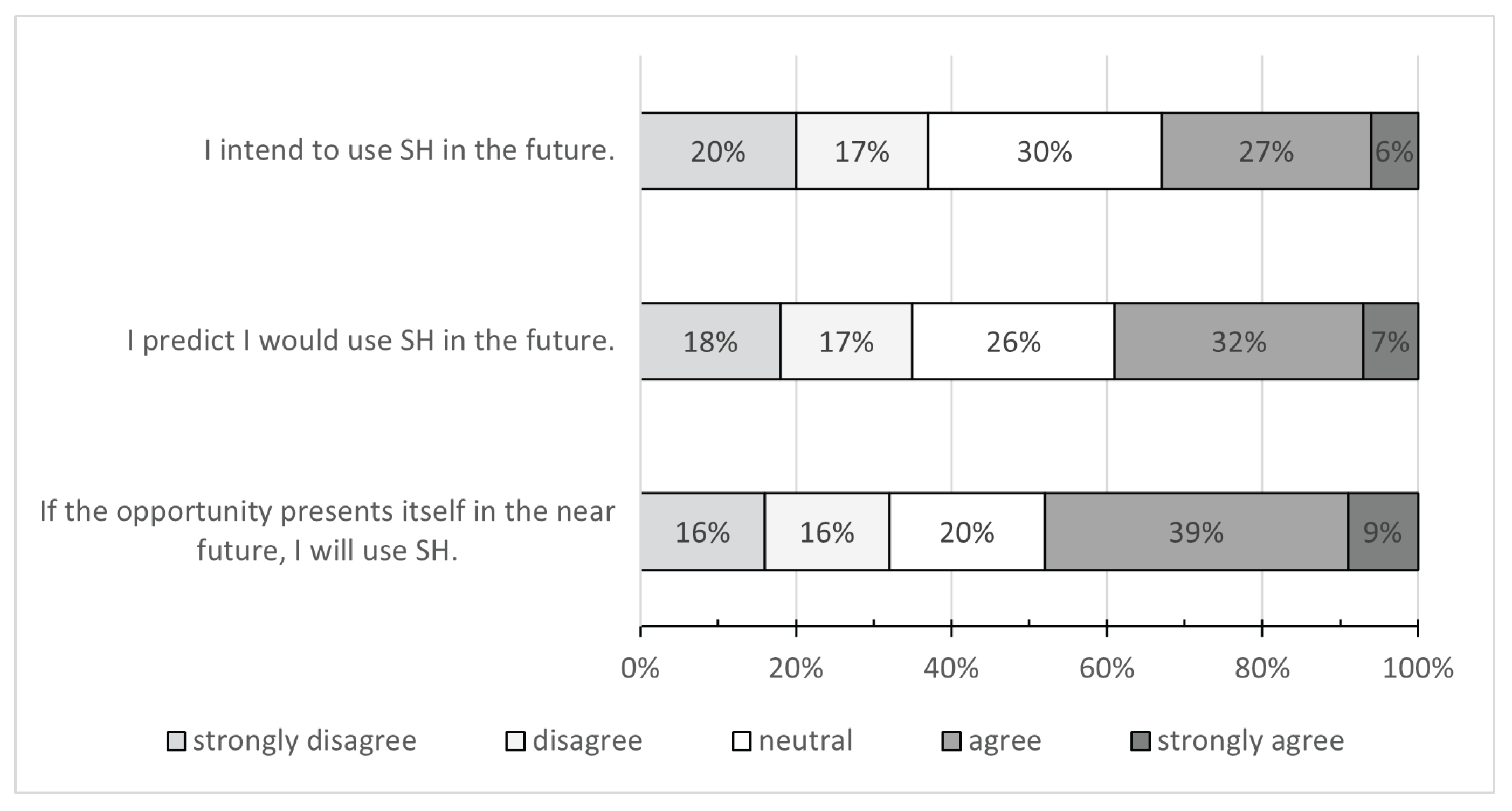

4.1. Intention to Adopt SH

4.2. Reliability of the Constructs

4.3. Descriptive Statistics

4.3.1. Evaluation of Prevention Benefits

4.3.2. Dimensions of SH Adoption

4.3.3. Risks and Costs

4.4. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion and Implications

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHA | Active Healthy Aging |

| CHERRIES | Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys |

| SH | Smart Home |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

- Part A: Introduction

| A “smart home” is a connected and intelligent home. Examples of smart homes are home systems with temperature controllers, door sensors, lighting systems, robotic vacuum cleaners, or even fitness exercises on the TV or video consultation with a doctor. Typically, a smart home is digital and can often be controlled remotely via a mobile phone. With the following survey, we investigate the interest for different smart home systems. Specifically, questions regarding benefits, design and risks are asked. |

- Part B: Smart home scenario

| In the following you will find a smart home scenario based on two examples. | |

| Example 1: Sensors in the housing. Sensors can already detect power consumption, temperature and humidity as well as movements. They are permanently on and can be controlled in real time via mobile phone. This makes it easy to adjust the room climate, control power consumption, alert for dangers such as a break-in, or allow access to neighbors when one is absent. |  Note: The above visualization is used from this point on throughout the survey, pinned on the top of the screen. |

| Example 2: Mobile health devices. They are compact devices, similar in size to a tablet, that enable health monitoring through integrated cameras and measuring devices. These devices are activated only when necessary, providing access to new health services. Fitness assessments and routine examinations can be conducted from the comfort of one’s home, while spontaneous inquiries can be addressed through video calls. | |

- Part C: Socio-demographic profile

- C6.1: Marriage/partnership. Spouse or partner

- C6.2: Single household. Live alone

- C6.3: Other household. Roommate

- C6.4: Household with kids. Children

- C6.5: Other household. Grandchildren

- C6.6: Other household. Parents

- Part D: Active healthy aging

- D6.1: Cultural activity level.Cultural activities with friends or like-minded people (theater visits, city trips, etc.)

- D6.2: Group sports involvement.Group sports activities (fitness group classes, hikes, bike tours, etc.)

- D6.3: Educational courses.Attendance of an educational or training course

- D6.4: Voluntary work.Voluntary or charity work

- D6.5: Club activity level.Participation in club activities (local hometown club, sports club, etc.)

- D6.6: Outing level.Going out with friends (dinners, cooking evenings, etc.)

- D6.7: Active grandparent.Helping others (looking after grandchildren, caring for relatives, etc.)

- Part E: Technology and risk affinity

- Part F: Insurance situation

- F1.1: Suppl. health insuranceSupplementary health insurance (in addition to mandatory health insurance)

- F1.2: Motor vehicle insurance Motor vehicle insurance

- F1.3: Travel insurance Travel insurance

- F1.4: Liability insurance Liability insurance

- F1.5: Life insurance Life insurance

- F1.6: Household insurance Household insurance

- F1.7: Legal expenses insurance Legal expenses insurance

- F1.8: Other insurance Other: [Free text as answer option.]

- Part G: Evaluation of prevention benefits

- Part H: Performance expectancy

- Part I: Effort expectancy

- Part J: Facilitating conditions

- Part K: Social influences

- Part L: Hedonic motivation

- Part M: Perceived risks

- Part N: Insurance costs and services

| Suppose you could get smart home services from an insurance company. The insurance company provides such services because they prevent accidents and contribute to home security. However, this implies a willingness to share data with the company. |

- Part O: Intention to adopt smart home

| Finally, we are interested to know if you intend to use smart home. Please indicate the level of agreement on the following final statements, with the two smart home examples in mind, and detached from the insurance context. |

Appendix B. Pre-Test Protocol

- Phase 1

| Interview date | Interviewee’s gender | Interviewee’s age (years) | Interviewee’s smart home knowledge | Interview duration (minutes) |

| 4 February 2022 | female | 57 | no | 25 |

| 5 February 2022 | male | 54 | good | 15 |

| 6 February 2022 | female | 62 | fair | 25 |

| 6 February 2022 | male | 61 | fair | 20 |

- Changed introductory part of the questionnaire by adding a few simple “icebreaker” questions (e.g., age and gender) to build a flow, in replace of an abstract smart home scenario description at the beginning.

- Questions on social well-being (cf. questions D6.1 to 6.7) extended by the answer option “few times per year” to a five-level-Likert scale.

- Added a question regarding home ownership (question C5).

- Minor wording adjustment in the insurance part N.

- Phase 2

- Question on the comprehensibility of the smart home examples, measured using a five-level-Likert scale ranging from 1 (not comprehensible) to 5 (comprehensible).

- If comprehensibility of the smart home examples was rated 1 or 2, an open comment box requested information on how comprehensibility can be improved.

- One open comment box at the end of parts L and N requested information on how comprehensibility can be improved regarding the “dimensions of SH adoption” and “risks and costs”, respectively.

| Age class (years) | Gender | Number of responses |

| 45–54 | female | 8 |

| 45–54 | male | 9 |

| 55–64 | female | 6 |

| 55–64 | male | 9 |

| 65-74 | female | 9 |

| 65–74 | male | 8 |

| 75+ | male | 1 |

- Added question regarding safety benefits (questions G2.1 and G2.2) because of the high agreement in all safety related questions.

- Changed title of smart home example 1 (question B1) to “Sensors in the housing” because of feedback that the original title (“Permanently installed sensors”) was associated to elevated installation efforts and would not suit tenants.

- Removed the question “Are facilities and services such as a doctor, pharmacy, or shopping available at your residence (or within 15 minutes driving distance)?” because of a 96% “yes” quota.

Appendix C. Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)

| Item Category | Checklist Item | Reference Location and/or Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Describe survey design | “We applied filters based on age (≥45 years, aligning with the research focus on AHA), quotas (67:33 ratio for German and French-speaking regions in Switzerland; 50:50 for female and male; 30:30:30:10 for age groups 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and over 75 years; 10:90 for participants without and with SH knowledge, respectively), and conducted quality checks throughout the survey using control questions.” |

| Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval and informed consent process | IRB approval | Ethics approval was submitted to the ad hoc commission of the ZHAW School of Management and Law and resulted in a waiver on 13 January 2022. |

| Informed consent | The first page, which asked for informed consent in order to participate in the survey, was the following: Welcome to the study on the benefits of smart home systems. This study is conducted by the Institute for Risk and Insurance at the ZHAW School of Management and Law. The survey is strictly confidential and only the ZHAW project team has access to the data collected. All your data will be collected anonymously and cannot be assigned to you personally. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact the university team (project team contact details provided). I agree that my personal data will be processed in accordance with the information provided here. (Yes/No opt-in box provided) | |

| Data protection | Access to the data set was limited to the authors of this paper. The polling agency also did not have access to the data set. Further, the data were fully anonymized and no data collected could give an inference to an individual person. Data were stored according to best practice guidelines of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). Access was given only to team members, managed on internal university GitHub, summarized exclusively in aggregated form, and participants could request to have raw data deleted. | |

| Development and pre-testing. Recruitment process and description of the sample having access to the questionnaire | Development and testing | “Prior to its distribution, we conducted a pilot test with individuals who met the eligibility criteria to ensure comprehensibility, usability and technical functionality (see the test protocol in Appendix B)” |

| Open survey versus closed survey | The survey was open. Since we worked with a polling agency, most of the respondents were prompted by them to complete our questionnaire. | |

| Contact mode/Advertising the survey | “The survey was conducted online in March 2022 using the Unipark software and administrated by a professional polling agency responsible for participant recruitment. Participants were provided financial incentives for successful completion and only given the title of the survey when first contacted.” | |

| Survey administration | Web/E-mail | The survey was created and managed with Unipark. All valid responses were collected via this website. |

| Context | The survey was not posted on any other website. See Checklist item “Contact mode” and “Advertising the survey” for more information on the polling agency. | |

| Mandatory/voluntary | Participation was voluntary and participants could opt out at any point of the survey. See Checklist item “Incentives” for more information. | |

| Incentives | The polling agency offered monetary incentives for successful completion. We were given a price per valid participant of EUR . However, we do not know the effective amount received by the participants. We were not charged for invalid answers (filter criteria and control questions). Therefore, we placed the filter questions at the beginning of the survey and the control questions throughout the questionnaire. | |

| Time/Date | “The survey was conducted online in March 2022 using the Unipark software and administrated by a professional polling agency responsible for participant recruitment.” The exact period was 19–29 March 2022. | |

| Randomization of items or questionnaires | All items were randomized, except for the questions regarding personal characteristics of the respondent (part A–F of the questionnaire) and the final statements on intention to use a smart home (part O). | |

| Adaptive questioning | No adaptive questioning or follow-up questions were used. | |

| Number of Items | “The core of the survey contains 122 questions organized into four categories (personal characteristics, evaluation of prevention benefits, dimensions of SH adoption, risks and costs) and 15 topics labeled from A through O.” | |

| Number of screens (pages) | A maximum of 15 items were queried on a page in order to keep usability high, resulting in 15 pages/screens. | |

| Completeness check | There was no completeness check at the end of the survey. However, Unipark made it possible to force an answer on certain questions. We chose to perform this for all items in the main part (parts G to O of the questionnaire). | |

| Review step | The back button was enabled throughout the questionnaire. No review functionalities were activated. | |

| Response rates | Unique site visitor | View rates were defined as those who opened the survey and viewed/loaded the first page of the survey, which was the informed consent page. Visitors were tracked using Unipark’s multiple standard cookies for tracking website visitors. |

| View rate | Not applicable. | |

| Participation rate | “A total number of 2553 participants were recruited, with 2490 agreeing to participate. […] The final sample consists of 1515 valid responses.” Details: participants, 63 disagreed on informed consent page, 409 screened out because of filter questions, 566 screened out in control questions. Total valid participants: . | |

| Completion rate | ||

| Preventing multiple entries from the same individual | Cookies used | Visitors were tracked using Unipark’s multiple standard cookies for tracking website visitors. Duplicate entries were prevented by restricting user access to only one completion. |

| IP check | Unipark generates a unique session ID for each respondent on the basis of different cookies and IP tracking. We checked for duplicate entries, which would have been eliminated. | |

| Log file analysis | None. | |

| Registration | The survey was publicly accessible and no registration was necessary. However, polling agencies typically work on their own platform where users can track participation in different polls. We do not know the exact mechanism that our polling agency applied. | |

| Analysis | Handling of incomplete questionnaires | Only complete questionnaires were analyzed. |

| Questionnaires submitted with an atypical timestamp | The response time averaged 18 min and 57 s, with a median of 16 min and 57 s. Cut-off points for responses that were “too long” or “too short” were not used due to presumed differences in the target groups’ technological competence for online questionnaires. Instead, we made use of control questions to test whether the survey was actively and consciously completed. | |

| Statistical correction | In terms of representativeness, we did not prioritize achieving a defined margin of error. This decision was based on several factors. First, representativeness was not the primary goal; rather, our focus was to conduct exploratory research on SH adoption with a focus on prevention. Second, recruiting the target population, especially those 75 years and older, through an online survey inherently introduces non-representativeness and selection bias. Finally, in our exploratory research, we emphasized the comprehensibility of the questionnaire, appropriate framing in the scenario section, and ensuring respondent engagement usage of control questions. Therefore, we did not adjust for the non-representativeness of the sample, and this fact must be kept in mind when analyzing the results. |

Appendix D. Regression Analyses

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.463 | <0.001 | *** |

| Comfort benefits (G1.1–G1.3, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.135 | 0.611 | |

| Agree | 0.207 | 0.491 | |

| Safety benefits (G2.1–G2.3, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.192 | 0.584 | |

| Agree | 0.283 | 0.428 | |

| Health benefits (G3.1–G3.5, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.501 | 0.020 | * |

| Agree | 0.273 | 0.340 | |

| Fitness benefits (G4.1–G4.4, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.335 | 0.083 | . |

| Agree | −0.108 | 0.721 | |

| Performance expectancy (H1–H6, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.019 | 0.947 | |

| Agree | 0.148 | 0.655 | |

| Effort expectancy (I1.1–I4.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −1.009 | 0.169 | |

| Agree | −0.955 | 0.184 | |

| Facilitating conditions (J1–J8, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 1.528 | 0.013 | * |

| Agree | 1.601 | 0.011 | * |

| Social influences (K1–K4, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.323 | 0.058 | . |

| Agree | 0.495 | 0.153 | |

| Hedonic motivation (L1–L10, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 1.359 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | 2.376 | <0.001 | *** |

| Increased dependence (M1.1–M1.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.245 | 0.168 | |

| Agree | 0.067 | 0.781 | |

| Costs (M2.1–M2.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.706 | 0.011 | * |

| Agree | −0.987 | <0.001 | *** |

| Privacy (M3.1–M3.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.482 | 0.056 | . |

| Agree | 0.360 | 0.107 | |

| Other risks (M4.1–M8.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.696 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | −1.059 | 0.003 | ** |

| Insurance costs (N1–N3, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.092 | 0.690 | |

| Agree | −0.311 | 0.221 | |

| Insurance prevention services (N4–N6, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.204 | 0.354 | |

| Agree | 0.180 | 0.453 | |

| Interest for insurance offering (N7–N8, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.679 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | 1.812 | <0.001 | *** |

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.857 | 0.007 | ** |

| Mildly strenuous activities (D1.1, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Often | −0.003 | 0.983 | |

| Really strenuous activities (D1.2, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Often | 0.213 | 0.099 | . |

| Frailty (D2, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | 0.035 | 0.808 | |

| Satisfaction with life (D3, baseline: dissatisfied) | |||

| Neutral | 0.279 | 0.341 | |

| Satisfied | 0.371 | 0.199 | |

| Depressive symptoms (D4, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | 0.118 | 0.393 | |

| Loneliness (D5, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Often | 0.348 | 0.063 | . |

| Cultural activity level (D6.1, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.353 | 0.020 | * |

| Often | 0.443 | 0.098 | . |

| Group sports involvement (D6.2, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.152 | 0.429 | |

| Often | −0.229 | 0.146 | |

| Educational courses (D6.3, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.251 | 0.307 | |

| Often | −0.197 | 0.412 | |

| Voluntary work (D6.4, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | −0.014 | 0.949 | |

| Often | 0.030 | 0.883 | |

| Club activity level (D6.5, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | −0.005 | 0.980 | |

| Often | 0.237 | 0.229 | |

| Outing level (D6.6, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.337 | 0.010 | * |

| Often | 0.453 | 0.013 | * |

| Active grandparent (D6.7, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.054 | 0.730 | |

| Often | −0.011 | 0.936 | |

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.430 | 0.002 | ** |

| Knowledge level (A1, baseline: poor) | |||

| Mediocre | 0.595 | <0.001 | *** |

| Good | 1.278 | 0.001 | *** |

| Convenience application (B1, baseline: dislike) | |||

| Neutral | −0.108 | 0.726 | |

| Like | 1.335 | <0.001 | *** |

| Health application (B2, baseline: dislike) | |||

| Neutral | 0.593 | 0.004 | ** |

| Like | 1.246 | <0.001 | *** |

| Survey language (baseline: DE) | |||

| FR | −0.172 | 0.314 | |

| Age (A2, baseline: 45–54 years) | |||

| 55–64 years | −0.431 | 0.030 | * |

| 65–74 years | −0.481 | 0.110 | |

| 75+ years | −0.703 | 0.065 | . |

| Gender (A3, baseline: female) | |||

| Male | 0.438 | 0.004 | ** |

| Education (C1, baseline: high school) | |||

| Mandatory | −0.033 | 0.936 | |

| Higher education | −0.123 | 0.463 | |

| Income sufficiency (C2, baseline: difficult) | |||

| Easy | 0.095 | 0.625 | |

| Expense capacity (C3, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.139 | 0.502 | |

| Professional situation (C4, baseline: employed) | |||

| Others | 0.120 | 0.651 | |

| Retired | 0.170 | 0.487 | |

| Home ownership (C5, baseline: rent) | |||

| Ownership | 0.413 | 0.014 | * |

| Marriage/partnership (C6.1, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.611 | 0.094 | . |

| Single household (C6.2, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.476 | 0.222 | |

| Household with kid(s) (C6.4, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.198 | 0.358 | |

| Other households (C6.3/5/6, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.418 | 0.373 | |

| Technology experimenter (E1, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.276 | 0.209 | |

| Agree | 1.216 | <0.001 | *** |

| Technology pioneer (E2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.219 | 0.266 | |

| Agree | 0.780 | 0.001 | *** |

| Technology expert (E3, baseline: poor) | |||

| Good | −0.125 | 0.802 | |

| Excellent | −0.029 | 0.954 | |

| Mistake avoider (E4, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.066 | 0.721 | |

| Agree | 0.525 | 0.009 | ** |

| Familiarity preferer (E5, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.342 | 0.078 | . |

| Agree | −0.380 | 0.041 | * |

| Risk-taking level (E6, baseline: not willing) | |||

| Moderately willing | 0.024 | 0.908 | |

| Willing | 0.221 | 0.342 | |

| Suppl. health insurance (F1.1, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | −0.041 | 0.819 | |

| Motor vehicle insurance (F1.2, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | −0.066 | 0.741 | |

| Travel insurance (F1.3, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | −0.008 | 0.959 | |

| Liability insurance (F1.4, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | 0.208 | 0.468 | |

| Life insurance (F1.5, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | 0.443 | 0.016 | * |

| Household insurance (F1.6, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | −0.132 | 0.691 | |

| Legal expenses insurance (F1.7, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | 0.147 | 0.355 | |

| Other insurance (F1.8, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | −0.163 | 0.613 | |

| Insurance app in use (F2, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | 0.090 | 0.565 | |

References

- Chang, S.; Nam, K. Smart Home Adoption: The Impact of User Characteristics and Differences in Perception of Benefits. Buildings 2021, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Estève, D.; Fourniols, J.Y.; Escriba, C.; Campo, E. Smart wearable systems: Current status and future challenges. Artif. Intell. Med. 2012, 56, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, F. Teaching Homes to Be Green: Smart Homes and the Environment; Technical Report; Green Alliance: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.R.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Ali, M.A.M. A Review of Smart Homes—Past, Present, and Future. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2012, 42, 1190–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iten, R.; Wagner, J.; Zeier Röschmann, A. On the Identification, Evaluation and Treatment of Risks in Smart Homes: A Systematic Literature Review. Risks 2021, 9, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D. Smart home technologies in Europe: A critical review of concepts, benefits, risks and policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalsen, S.; Dowling, R. COVID-19 and the accelerating smart home. Big Data Soc. 2020, 7, 205395172093807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafurian, M.; Ellard, C.; Dautenhahn, K. An investigation into the use of smart home devices, user preferences, and impact during COVID-19. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2023, 11, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Humboldt, S.; Mendoza-Ruvalcaba, N.M.; Arias-Merino, E.D.; Costa, A.; Cabras, E.; Low, G.; Leal, I. Smart technology and the meaning in life of older adults during the COVID-19 public health emergency period: A cross-cultural qualitative study. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2020, 32, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiad, A.; Zhou, L. The determinants of home healthcare robots adoption: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binette, J.; Vasold, K. 2018 Home and Community Preferences: A National Survey of Adults Age 18-Plus; Technical Report; AARP Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnemolla, P. Ageing in place and the internet of things—How smart home technologies, the built environment and caregiving intersect. Vis. Eng. 2018, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tural, E.; Lu, D.; Cole, D.A. Safely and Actively Aging in Place: Older Adults’ Attitudes and Intentions Toward Smart Home Technologies. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 7, 233372142110173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikou, S. Factors driving the adoption of smart home technology: An empirical assessment. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 45, 101283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turjamaa, R.; Pehkonen, A.; Kangasniemi, M. How smart homes are used to support older people: An integrative review. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2019, 14, e12260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shank, D.B.; Wright, D.; Lulham, R.; Thurgood, C. Knowledge, Perceived Benefits, Adoption, and Use of Smart Home Products. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2021, 37, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; McGill, T.J.; Klobas, J.E. I Want It Anyway: Consumer Perceptions of Smart Home Devices. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2020, 60, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.; Hargreaves, T.; Hauxwell-Baldwin, R. Benefits and risks of smart home technologies. Energy Policy 2017, 103, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikyan, D.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. A systematic review of the smart home literature: A user perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 138, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Erol, I.; Liu, A. Motivations, barriers and risks of smart home adoption: From systematic literature review to conceptual framework. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Große-Kreul, F. What will drive household adoption of smart energy? Insights from a consumer acceptance study in Germany. Util. Policy 2022, 75, 101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schill, M.; Godefroit-Winkel, D.; Diallo, M.F.; Barbarossa, C. Consumers’ intentions to purchase smart home objects: Do environmental issues matter? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 161, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthanat, S.; Wilcox, J.; Macuch, M. Profiles and Predictors of Smart Home Technology Adoption by Older Adults. OTJR Occup. Particip. Health 2019, 39, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowsky, R.; Sharit, J.; Czaja, S. Factors Predicting Decisions About Technology Adoption Among Older Adults. Innov. Aging 2017, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework; Technical Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Farré, C.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Bonmatí-Tomàs, A.; Malagón-Aguilera, M.C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Fuentes-Pumarola, C.; Juvinyà-Canal, D. Prevalence and related factors of Active and Healthy Ageing in Europe according to two models: Results from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacken, M.; Marcellini, F.; Széman, Z. Use and acceptance of new technology by older people. Findings of the international MOBILATE survey: ‘Enhancing mobility in later life’. Gerontechnology 2005, 3, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, M.; Jung, C.; Awad, J.; Chohan, A.H. Analysis of Smart Home Technology Acceptance and Preference for Elderly in Dubai, UAE. Designs 2021, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flückiger, I.; Carbone, M. From Risk Transfer to Risk Prevention—How the Internet of Things Is Reshaping Business Models in Insurance; Technical Report; The Geneva Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hubert, M.; Blut, M.; Brock, C.; Zhang, R.W.; Koch, V.; Riedl, R. The influence of acceptance and adoption drivers on smart home usage. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Park, Y.; Lee, D. Who will be smart home users? An analysis of adoption and diffusion of smart homes. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 134, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodimeji, Z.O.; Janardhanan, M.; Marinelli, M.; Patel, I. Adoption of Smart Homes in the UK: Customers’ Perspective. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Engineering; Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S.J. Smart home services as the next mainstream of the ICT industry: Determinants of the adoption of smart home services. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2018, 17, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Funilkul, S.; Charoenkitkarn, N.; Kanthamanon, P. Internet-of-Things and Smart Homes for Elderly Healthcare: An End User Perspective. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 10483–10496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sequeiros, H.; Oliveira, T.; Thomas, M.A. The Impact of IoT Smart Home Services on Psychological Well-Being. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 24, 1009–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, Y.; Choi, J. A study on the adoption of IoT smart home service: Using Value-based Adoption Model. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2017, 28, 1149–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, R.; Sorwar, G. Understanding factors influencing the adoption of mHealth by the elderly: An extension of the UTAUT model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2017, 101, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baudier, P.; Ammi, C.; Deboeuf-Rouchon, M. Smart home: Highly-educated students’ acceptance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 153, 119355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimperman, M.; Brenčič, M.M.; Trkman, P. Analyzing older users’ home telehealth services acceptance behavior—Applying an Extended UTAUT model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 90, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.; Cho, Y.; Han, J.; Kwon, S.J. Comprehensive Approaches to User Acceptance of Internet of Things in a Smart Home Environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuhaiber, A.; Mashal, I. Understanding users’ acceptance of smart homes. Technol. Soc. 2019, 58, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, F.; Sivanathan, A.; Gharakheili, H.H.; Radford, A.; Sivaraman, V. Systematically Evaluating Security and Privacy for Consumer IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Internet of Things Security and Privacy, Dallas, TX, USA, 3 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, P.S.; Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Rompay, T.J. Accepting the Internet-of-Things in our homes: The role of user skills. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 36, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebel, H.; Zarnekow, R. Exploring Platform Adoption in the Smart Home Case. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2015 Proceedings, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marikyan, D.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. Smart Home Technology Acceptance: An Empirical Investigation. In Proceedings of the Digital Transformation for a Sustainable Society in the 21st Century, Trondheim, Norway, 18–20 September 2019; pp. 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luor, T.; Lu, H.P.; Yu, H.; Lu, Y. Exploring the critical quality attributes and models of smart homes. Maturitas 2015, 82, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furszyfer Del Rio, D.; Sovacool, B.K.; Martiskainen, M. Controllable, frightening, or fun? Exploring the gendered dynamics of smart home technology preferences in the United Kingdom. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, A.; Nam, C.; Kim, S. What will be the possible barriers to consumers’ adoption of smart home services? Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klobas, J.E.; McGill, T.; Wang, X. How perceived security risk affects intention to use smart home devices: A reasoned action explanation. Comput. Secur. 2019, 87, 101571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Martiskainen, M.; Furszyfer Del Rio, D.D. Knowledge, energy sustainability, and vulnerability in the demographics of smart home technology diffusion. Energy Policy 2021, 153, 112196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lee, H.; Zo, H. User acceptance of smart home services: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta-Ozkan, N.; Davidson, R.; Bicket, M.; Whitmarsh, L. Social barriers to the adoption of smart homes. Energy Policy 2013, 63, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.; Aarts, S.; Wouters, E.J. Can Smart Home Technology Deliver on the Promise of Independent Living? In Handbook of Smart Homes, Health Care and Well-Being; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacasa. Smart Living Loft by Bonacasa: Site Visit in Oensingen, Switzerland. 2021. Available online: https://www.bonacasa.ch/de/geschaeftskunden/concept-development/smart-living-loft-by-bonacasa (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Eysenbach, G. Improving the Quality of Web Surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J. Med. Internet Res. 2004, 6, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iten, R.; Wagner, J.; Zeier Röschmann, A. Survey Data on the Adoption of Smart Home Technologies by Older Adults in Switzerland. in preparation.

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 140, 5–53. [Google Scholar]

- Calasanti, T.; Repetti, M. Swiss Retirees as “Active Agers”: A Critical Look at this New Social Role. Popul. Ageing 2017, 11, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Börsch-Supan, A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)Wave 8. Release Version: 8.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data Set. 2022. Available online: https://share-eric.eu/data/data-documentation/waves-overview/wave-8 (accessed on 22 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution; Social Science Open Access Repository (SSOAR): Klagenfurt, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. Insights and Strategies for Smart Home Insurance Programs; Technical Report; LexisNexis Risk Solutions: El Paso, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D. Preventing Water Claims: Understanding the Value of Smart Home Technology; Technical Report; LexisNexis Risk Solutions: El Paso, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sevillano, C. Smart Homes. In Proceedings of the EMEA Claims Conference, Rüschlikon, Switzerland, 7 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Śliwiński, A.; Kuryłowicz, Ł. Usage-based insurance and its acceptance: An empirical approach. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2021, 24, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeier Röschmann, A.; Erny, M.; Wagner, J. On the (future) role of on-demand insurance: Market landscape, business model and customer perception. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2022, 47, 603–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Mutivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer, M.; Wagner, J. New solvency regulation: What CEOs of insurance companies think. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2013, 38, 213–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pelau, C.; Dabija, D.C.; Ene, I. What makes an AI device human-like? The role of interaction quality, empathy and perceived psychological anthropomorphic characteristics in the acceptance of artificial intelligence in the service industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegard, R.B.; Breitner, M.H. Smart services in healthcare: A risk-benefit-analysis of pay-as-you-live services from customer perspective in Germany. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Framework | References |

|---|---|---|

| Usefulness | UTAUT | Alaiad and Zhou [10], Große-Kreul [22], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Pal et al. [35], Sequeiros et al. [36], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Baudier et al. [39], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| TAM | Tural et al. [13], Nikou [14], Hubert et al. [31], Shin et al. [32], Park et al. [41], Shuhaiber and Mashal [42], De Boer et al. [45], Kuebel and Zarnekow [46], Marikyan et al. [47] | |

| Other | Wang et al. [18], Schill et al. [23], Kim et al. [37], Luor et al. [48] | |

| Usability | UTAUT | Alaiad and Zhou [10], Große-Kreul [22], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Pal et al. [35], Sequeiros et al. [36], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Baudier et al. [39], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| TAM | Tural et al. [13], Nikou [14], Hubert et al. [31], Shin et al. [32], Park et al. [41], Shuhaiber and Mashal [42], De Boer et al. [45], Kuebel and Zarnekow [46], Marikyan et al. [47] | |

| Other | Wang et al. [18] | |

| Support and resources | UTAUT | Alaiad and Zhou [10], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Pal et al. [35], Sequeiros et al. [36], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Baudier et al. [39], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| Other | Kim et al. [37] | |

| Social influences | UTAUT | Alaiad and Zhou [10], Große-Kreul [22], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Pal et al. [35], Sequeiros et al. [36], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Baudier et al. [39], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| Hedonic motivation | UTAUT | Große-Kreul [22], Sequeiros et al. [36], Baudier et al. [39] |

| TAM | Park et al. [41], Shuhaiber and Mashal [42], Marikyan et al. [47] | |

| Other | Kim et al. [37] | |

| Risks and barriers | UTAUT | Alaiad and Zhou [10], Arar et al. [29], Pal et al. [35], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| TAM | Nikou [14], Hubert et al. [31], Shin et al. [32], Shuhaiber and Mashal [42], Marikyan et al. [47] | |

| Other | Wang et al. [18], Kim et al. [37], Luor et al. [48], Furszyfer Del Rio et al. [49], Hong et al. [50], Klobas et al. [51] | |

| Price value | UTAUT | Sequeiros et al. [36], Baudier et al. [39] |

| TAM | Tural et al. [13] | |

| Habit | UTAUT | Sequeiros et al. [36], Baudier et al. [39] |

| Trust | Other | Luor et al. [48], Furszyfer Del Rio et al. [49] |

| Expert advice | UTAUT | Pal et al. [35], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| Technology anxiety | UTAUT | Arar et al. [29], Pal et al. [35], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| Characteristics | Population | References |

|---|---|---|

| Age | General | Tural et al. [13], Shank et al. [17], Wang et al. [18], Li et al. [21], Shin et al. [32], Sequeiros et al. [36], Hoque and Sorwar [38], Klobas et al. [51] |

| Gender | Older Adults | Chang and Nam [1], Tural et al. [13], Arthanat et al. [24], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Cimperman et al. [40] |

| General | Nikou [14], Shin et al. [32], Sovacool et al. [52], Yang et al. [53] | |

| Education | Older Adults | Chang and Nam [1], Tural et al. [13] |

| General | Shin et al. [32], Klobas et al. [51] | |

| Income | Older Adults | Chang and Nam [1], Tural et al. [13], Shank et al. [17] |

| General | Shin et al. [32] | |

| Martial status | Older Adults | Arthanat et al. [24] |

| SH experience | Older Adults | Chang and Nam [1] |

| General | Nikou [14], Shank et al. [17], Yang et al. [53] | |

| SH knowledge | Older Adults | Wilson et al. [19], Ayodimeji et al. [33], Marikyan et al. [47], Balta-Ozkan et al. [54] |

| Technology ownership | Older Adults | Tural et al. [13], Arthanat et al. [24] |

| General | De Boer et al. [45] | |

| Technology affinity | Older Adults | Arar et al. [29] |

| General | Wilson et al. [19], Hubert et al. [31] | |

| Home ownership | Older Adults | Tural et al. [13], Arthanat et al. [24] |

| Household size | Older Adults | Tural et al. [13], Peek et al. [55] |

| AHA | Older Adults | Carnemolla [12], Tacken et al. [28] |

| Label | Description | Categories | Question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and preference variables | |||

| Knowledge level | Level of experience in SHs | Five levels from no knowledge to very good knowledge | A1 |

| Convenience application | Preference for sensors in the housing | Five levels from dislike to like | B1 |

| Health application | Preference for mobile health device | ” | B2 |

| Socio-demographic variables | |||

| Survey language | Chosen language of the questionnaire | German, French | n.a. |

| Age | Age class in years | 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75+ (from numeric answers) | A2 |

| Gender | Gender of the respondent | Female, male, diverse, prefer not to reply | A3 |

| Education | Highest level of education | Mandatory school, high school, higher education | C1 |

| Income sufficiency | Income sufficiency for recurring expenses | With great difficulty; with some difficulty; fairly easily; easily | C2 |

| Expense capacity | Ability to cover an unexpected expense | No, yes | C3 |

| Professional situation | Current employment situation | Retired, employed, unemployed, homemaker, unable to work | C4 |

| Home ownership | Main residence ownership | Rent, ownership | C5 |

| Marriage/partnership | Living with spouse/partner in a household | No, yes | C6.1 |

| Single household | Living alone (without anyone else) | ” | C6.2 |

| Household with kid(s) | Living with kids in one household | ” | C6.4 |

| Other households | Living in other household constellation | ” | C6.3,5,6 |

| Active healthy aging variables | |||

| Mildly strenuous activities | Physically mildly strenuous activities | Hardly ever, 1–2× month, 1× week, >1× week | D1.1 |

| Really strenuous activities | Physically very strenuous activities | ” | D1.2 |

| Frailty | Frailty in certain everyday activities | No, yes | D2 |

| Satisfaction with life | Satisfaction with current life situation | Five levels from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied | D3 |

| Depressive symptoms | Feeling sad or depressed | No, yes | D4 |

| Loneliness | Feeling lack of companionship | Almost never or never, 1–2× month, 1× week, >1× week | D5 |

| Cultural activity level | Participation in cultural activities | Hardly ever, few times a year, 1–2× month, 1× week, >1× week | D6.1 |

| Group sports involvement | Participation in group sports | ” | D6.2 |

| Educational courses | Participation in educational courses | ” | D6.3 |

| Voluntary work | Participation in voluntary work | ” | D6.4 |

| Club activity level | Participation in club activities | ” | D6.5 |

| Outing level | Going out with friends | ” | D6.6 |

| Active grandparent | Looking after grandchildren | ” | D6.7 |

| Technology and risk affinity variables | |||

| Technology experimenter | Pleasure in trying new technologies | Five levels from strongly disagree to strongly agree | E1 |

| Technology pioneer | First to try new technologies | ” | E2 |

| Technology expert | Skills using smartphone or tablet | Five levels from poor to excellent | E3 |

| Mistake avoider | Potential errors discourage from usage | Five levels from strongly disagree to strongly agree | E4 |

| Familiarity preferer | Familiar things are preferred over new ones | ” | E5 |

| Risk-taking level | Self-assessed preferences for risky behavior | Five levels from not at all to very willing to take risks | E6 |

| Insurance situation variables | |||

| Suppl. health insurance | Supplementary health insurance | No, yes | F1.1 |

| Motor vehicle insurance | Motor vehicle insurance | ” | F1.2 |

| Travel insurance | Travel insurance | ” | F1.3 |

| Liability insurance | Liability insurance | ” | F1.4 |

| Life insurance | Life insurance | ” | F1.5 |

| Household insurance | Household insurance | ” | F1.6 |

| Legal expenses insurance | Legal expenses insurance | ” | F1.7 |

| Other insurance | Other less frequent insurance contracts | ” | F1.8 |

| Insurance app in use | App from any insurance company in use | ” | F2 |

| Label | Description | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of prevention benefits | ||

| Burden relief | Reduce burden of household activities | G1.1 |

| Home information | Provide information and control options | G1.2 |

| Value enhancement | Maintain or increase property value | G1.3 |

| Sense of safety | Make feel more safe | G2.1 |

| Security booster | Increase home security | G2.2 |

| Risk protection | Protect against risks at home | G2.3 |

| Health maintenance | Take care of oneself and avoid doctor visit | G3.1 |

| Health monitoring | Monitor easily health metrics | G3.2 |

| Health encouragement | Motivate to behave healthier | G3.3 |

| Accident prevention | Help to prevent accidents and health risks | G3.4 |

| Family well-check | Check if family and friends are well | G3.5 |

| Automated fitness | Perform something automatically for fitness | G4.1 |

| Exercise feedback | Obtain immediate feedback on fitness exercises | G4.2 |

| Movement motivation | Motivate to move more | G4.3 |

| Socializing opportunity | Meet new people for training groups | G4.4 |

| Label | Description | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | ||

| Everyday simplification | Simplify everyday household activities | H1 |

| Home monitoring | Monitor state or progress of home effectively | H2 |

| Activity motivation | Motivate to conduct activities that do not like to do | H3 |

| Money saving | Save money with technology usage | H4 |

| Social connectivity | Stay in touch with family and friends | H5 |

| Shared access | Give access to others when needed | H6 |

| Effort expectancy | ||

| Easy to use | Designed to be easy to use | I1.1 |

| Intuitive | Designed to be intuitively understandable | I1.2 |

| Easy to learn | Designed to be easy to learn | I1.3 |

| Quickly usable | Designed to be quickly usable | I1.4 |

| Customizable | Designed to be individually customizable | I2.1 |

| Tailored | Designed to be tailored to one properly | I2.2 |

| Trustworthy | Designed to be trustworthy | I3.1 |

| Warrantied | Designed to be backed by credible warranties | I3.2 |

| Autonomous | Designed to be used without consulting others | I4.1 |

| Seamless | Designed to be used independently without problems | I4.2 |

| Facilitating conditions | ||

| Availability of usage instructions | Instructions available on proper usage | J1 |

| Availability of a professional for questions | Professionals available if any questions | J2 |

| Availability of a professional when problems | Professionals available if any system problems | J3 |

| Availability of close people | Close people available if any difficulties | J4 |

| Availability of colleagues/friends | Colleagues or friends are happy to support | J5 |

| Availability of own knowledge | Sufficient knowledge required for usage | J6 |

| Fit to daily life | Fit well into daily routine | J7 |

| Fit to household | Fit well to household organization | J8 |

| Social influences | ||

| Meaning to important others | Important people encourage technology usage | K1 |

| Meaning to opinion makers | Valued opinions encourage technology usage | K2 |

| Prestigious image | Users have a more prestigious image | K3 |

| Modern image | Users are perceived as modern | K4 |

| Hedonic motivation | ||

| Entertaining | Using SH is entertaining | L1 |

| Enjoyable | Using SH is enjoyable | L2 |

| Convenient | Using SH is convenient | L3 |

| Curiosity-inducing | Using SH arouses curiosity | L4 |

| Versatile | Using SH is versatile | L5 |

| Fun | Using SH is fun | L6 |

| Pleasant | Using SH is pleasant | L7 |

| Relieving | Using SH brings relief | L8 |

| Trending | Using SH helps to be at the pulse of time | L9 |

| Variegating | Using SH leads to more variety in everyday life | L10 |

| Label | Description | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived risks | ||

| Dependence | Concern of increasing dependence on technology | M1.1 |

| Loss of control | Concern of losing control of technology | M1.2 |

| Costs exceeding benefits | Concern of costs exceeding benefits | M2.1 |

| Expensive maintenance | Concern of expensive maintenance | M2.2 |

| Data misuse | Concern of collected data being misused | M3.1 |

| Data used unforeseeable | Concern of collected data being used unforeseeable | M3.2 |

| Overwhelming | Concern of overwhelming technology usage | M4.1 |

| Cumbersome | Concern of cumbersome technology usage | M4.2 |

| Go less out of house | Concern of going out of the house less | M5 |

| Non-essential luxuries | Concern of turning into a non-essential luxury | M6 |

| Source of problems | Concern of leading to problems | M7.1 |

| Insecure | Concern of being insecure | M7.2 |

| Replace contact with others | Concern of replacing contact with others | M8.1 |

| Lack of human interaction | Concern of resulting in lack of human interaction | M8.2 |

| Insurance costs and services | ||

| Discount on insurance premium | Expect to receive discount on insurance premium | N1 |

| Automatic premium adjustment | Expect price of insurance to adjust automatically | N2 |

| Reimbursement of purchase costs | Expect insurer to cover cost of purchase | N3 |

| Advice from insurer | Expect insurer to provide advice on home maintenance | N4 |

| Early warning from insurer | Expect insurer to give early warning on incipient risks | N5 |

| Individual offers from insurer | Expect insurer to provide offers that match personal interests | N6 |

| Future SH insurance intention | Intention to use SH insurance | N7 |

| Future SH insurance plan | Intention to use SH insurance when opportunity arises | N8 |

| Construct | Description | Questions | Cronbach’s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of prevention benefits | |||

| Comfort benefits | Prevention benefits perceived for comfort | G1.1–G1.3 | 0.699 |

| Safety benefits | Prevention benefits perceived for safety | G2.1–G2.3 | 0.850 |

| Health benefits | Prevention benefits perceived for health | G3.1–G3.5 | 0.892 |

| Fitness benefits | Prevention benefits perceived for fitness | G4.1–G4.4 | 0.825 |

| Dimensions of SH adoption | |||

| Performance expectancy | General SH usage benefits | H1–H6 | 0.865 |

| Effort expectancy | Easiness of SH usage | I1.1–I4.2 | 0.953 |

| Facilitating conditions | Support and resources available for SH usage | J1–J8 | 0.759 |

| Social influences | Relevant extent others believe one should use SH | K1–K4 | 0.825 |

| Hedonic motivation | Fun or pleasure derived from SH usage | L1–L10 | 0.958 |

| Risks and costs | |||

| Increased dependence | Risks related to increased dependence | M1.1–M1.2 | 0.713 |

| Costs | Risks related to costs of purchase and use | M2.1–M2.2 | 0.871 |

| Privacy | Risks related to privacy | M3.1–M3.2 | 0.936 |

| Other risks | Risks related to other aspects of daily life | M4.1–M8.2 | 0.869 |

| Insurance costs | Cost considerations on SH insurance offerings | N1–N3 | 0.801 |

| Insurance prevention services | Service considerations on SH insurance offerings | N4–N6 | 0.862 |

| Interest for insurance offering | Intention to use SH insurance offerings | N7–N8 | 0.847 |

| Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and preference variables | ||||||||

| Knowledge level (A1) | Convenience application (B1) | Health application (B2) | ||||||

| Poor | 60.2 | 36.3 | Dislike | 17.5 | 16.2 | Dislike | 31.5 | 26.2 |

| Mediocre | 32.2 | 63.9 | Neutral | 13.5 | 21.7 | Neutral | 22.7 | 46.1 |

| Good | 7.6 | 86.2 | Like | 69.0 | 62.4 | Like | 45.8 | 65.8 |

| Socio-demographic variables | ||||||||

| Survey language | Income sufficiency (C2) | Marriage/partnership (C6.1) | ||||||

| DE | 66.6 | 47.5 | Easy | 66.5 | 50.7 | Yes | 62.3 | 50.8 |

| FR | 33.4 | 51.9 | Difficult | 33.5 | 45.5 | No | 37.7 | 45.9 |

| Age (A2) | Expense capacity (C3) | Single household (C6.2) | ||||||

| 45–54 years | 31.0 | 56.3 | Yes | 66.6 | 50.8 | Yes | 30.6 | 45.6 |

| 55–64 years | 29.2 | 50.4 | No | 33.4 | 45.2 | No | 69.4 | 50.4 |

| 65–74 years | 30.8 | 44.5 | Professional situation (C4) | Household with kid(s) (C6.4) | ||||

| 75+ years | 9.0 | 34.2 | Employed | 49.7 | 55.5 | Yes | 22.9 | 53.5 |

| Gender (A3) a | Others | 11.0 | 46.0 | No | 77.1 | 47.6 | ||

| Female | 51.0 | 40.6 | Retired | 39.3 | 41.5 | Other households (C6.3/5/6) | ||

| Male | 49.0 | 57.7 | Home ownership (C5) | Yes | 3.8 | 40.4 | ||

| Education (C1) | Rent | 51.7 | 46.5 | No | 96.2 | 49.3 | ||

| Mandatory | 3.1 | 43.6 | Ownership | 48.3 | 51.6 | |||

| High school | 64.4 | 45.5 | ||||||

| Higher education | 32.5 | 56.3 | ||||||

| Active healthy aging variables | ||||||||

| Mildly strenuous activities (D1.1) | Loneliness (D5) | Voluntary work (D6.4) | ||||||

| Rarely | 19.5 | 46.7 | Rarely | 86.5 | 48.0 | Rarely | 81.0 | 48.6 |

| Often | 80.5 | 49.5 | Often | 13.5 | 55.1 | Regularly | 8.4 | 51.0 |

| Really strenuous activities (D1.2) | Cultural activity level (D6.1) | Often | 10.6 | 50.4 | ||||

| Rarely | 57.3 | 46.2 | Rarely | 72.9 | 45.1 | Club activity level (D6.5) | ||

| Often | 42.7 | 52.6 | Regularly | 21.5 | 58.3 | Rarely | 78.7 | 47.8 |

| Frailty (D2) | Often | 5.6 | 62.9 | Regularly | 9.4 | 50.9 | ||

| Yes | 21.6 | 47.4 | Group sports involvement (D6.2) | Often | 11.9 | 54.7 | ||

| No | 78.4 | 49.4 | Rarely | 65.7 | 47.5 | Outing level (D6.6) | ||

| Satisfaction with life (D3) | Regularly | 11.1 | 57.2 | Rarely | 44.9 | 42.0 | ||

| Dissatisfied | 5.1 | 42.2 | Often | 23.2 | 49.1 | Regularly | 38.4 | 53.2 |

| Neutral | 18.9 | 47.4 | Educational courses (D6.3) | Often | 16.7 | 58.0 | ||

| Satisfied | 76.0 | 49.8 | Rarely | 87.4 | 48.5 | Active grandparent (D6.7) | ||

| Depressive symptoms (D4) | Regularly | 6.0 | 56.8 | Rarely | 52.0 | 47.4 | ||

| Yes | 34.3 | 50.8 | Often | 6.6 | 47.6 | Regularly | 19.6 | 51.4 |

| No | 65.7 | 48.0 | Often | 28.4 | 50.0 | |||

| Technology and risk affinity variables | ||||||||

| Technology experimenter (E1) | Technology expert (E3) | Familiarity preferer (E5) | ||||||

| Disagree | 26.8 | 21.0 | Poor | 3.2 | 20.0 | Disagree | 40.1 | 58.1 |

| Neutral | 23.9 | 35.1 | Good | 28.7 | 34.8 | Neutral | 25.0 | 46.1 |

| Agree | 49.3 | 70.9 | Excellent | 68.1 | 56.3 | Agree | 34.9 | 40.4 |

| Technology pioneer (E2) | Mistake avoider (E4) | Risk-taking level (E6) | ||||||

| Disagree | 53.5 | 32.7 | Disagree | 44.2 | 54.9 | Not willing | 20.8 | 36.4 |

| Neutral | 21.8 | 53.5 | Neutral | 30.0 | 40.9 | Moderately willing | 47.3 | 44.4 |

| Agree | 24.7 | 80.1 | Agree | 25.8 | 48.1 | Willing | 31.9 | 63.9 |

| Insurance situation variables | ||||||||

| Suppl. health insurance (F1.1) | Liability insurance (F1.4) | Legal expenses insurance (F1.7) | ||||||

| Yes | 76.3 | 49.5 | Yes | 92.4 | 49.5 | Yes | 55.3 | 52.8 |

| No | 23.7 | 47.3 | No | 7.6 | 42.6 | No | 44.7 | 44.2 |

| Motor vehicle insurance (F1.2) | Life insurance (F1.5) | Other insurance (F1.8) | ||||||

| Yes | 80.2 | 50.5 | Yes | 26.6 | 60.0 | Yes | 5.6 | 49.3 |

| No | 19.8 | 42.7 | No | 73.4 | 44.9 | No | 94.4 | 48.9 |

| Travel insurance (F1.3) | Household insurance (F1.6) | Insurance app in use (F2) | ||||||

| Yes | 42.3 | 53.0 | Yes | 94.0 | 49.4 | Yes | 46.4 | 60.3 |

| No | 57.7 | 46.0 | No | 6.0 | 41.3 | No | 53.6 | 39.1 |

| Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort benefits | ||||||||

| Burden relief (G1.1) | Value enhancement (G1.3) | Comfort benefits | ||||||

| Disagree | 30.5 | 37.3 | Disagree | 19.2 | 27.7 | Disagree | 17.8 | 18.1 |

| Neutral | 21.5 | 37.5 | Neutral | 33.9 | 40.6 | Neutral | 46.5 | 45.1 |

| Agree | 48.0 | 61.5 | Agree | 46.9 | 63.7 | Agree | 35.7 | 69.3 |

| Home information (G1.2) | ||||||||

| Disagree | 10.7 | 12.8 | ||||||

| Neutral | 14.8 | 25.1 | ||||||

| Agree | 74.5 | 58.9 | ||||||

| Safety benefits | ||||||||

| Sense of safety (G2.1) | Risk protection (G2.3) | Safety benefits | ||||||

| Disagree | 14.8 | 17.5 | Disagree | 7.9 | 16.3 | Disagree | 10.8 | 15.7 |

| Neutral | 23.2 | 37.8 | Neutral | 12.7 | 25.5 | Neutral | 17.4 | 33.3 |

| Agree | 62.0 | 60.6 | Agree | 79.4 | 55.9 | Agree | 71.8 | 57.8 |

| Security booster (G2.2) | ||||||||

| Disagree | 10.2 | 16.7 | ||||||

| Neutral | 13.9 | 29.5 | ||||||

| Agree | 75.9 | 56.9 | ||||||

| Health benefits | ||||||||

| Health maintenance (G3.1) | Health encouragement (G3.3) | Family well-check (G3.5) | ||||||

| Disagree | 27.2 | 27.8 | Disagree | 32.7 | 28.6 | Disagree | 20.4 | 28.1 |

| Neutral | 28.0 | 43.8 | Neutral | 30.1 | 48.5 | Neutral | 26.9 | 41.0 |

| Agree | 44.8 | 65.0 | Agree | 37.2 | 67.2 | Agree | 52.7 | 61.1 |

| Health monitoring (G3.2) | Accident prevention (G3.4) | Health benefits | ||||||

| Disagree | 19.7 | 23.4 | Disagree | 30.7 | 31.2 | Disagree | 31.0 | 24.2 |

| Neutral | 21.1 | 37.4 | Neutral | 31.0 | 48.7 | Neutral | 45.2 | 53.6 |

| Agree | 59.2 | 61.6 | Agree | 38.3 | 63.4 | Agree | 23.8 | 72.5 |

| Fitness benefits | ||||||||

| Automated fitness (G4.1) | Movement motivation (G4.3) | Fitness benefits | ||||||

| Disagree | 35.1 | 33.3 | Disagree | 32.7 | 30.3 | Disagree | 41.4 | 33.1 |

| Neutral | 33.9 | 47.6 | Neutral | 25.8 | 44.4 | Neutral | 43.7 | 54.2 |

| Agree | 31.0 | 68.1 | Agree | 41.5 | 66.5 | Agree | 14.9 | 77.3 |

| Exercise feedback (G4.2) | Socializing opportunity (G4.4) | |||||||

| Disagree | 26.3 | 29.1 | Disagree | 44.5 | 40.2 | |||

| Neutral | 30.4 | 43.5 | Neutral | 35.7 | 49.4 | |||

| Agree | 43.3 | 64.8 | Agree | 29.8 | 67.8 | |||

| Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance expectancy | ||||||||

| Everyday simplification (H1) | Money saving (H4) | Performance expectancy | ||||||

| Disagree | 10.3 | 8.6 | Disagree | 10.4 | 16.3 | Disagree | 19.3 | 14.6 |

| Neutral | 11.8 | 17.8 | Neutral | 16.5 | 38.5 | Neutral | 48.1 | 45.8 |

| Agree | 77.9 | 59.0 | Agree | 73.1 | 56.0 | Agree | 32.6 | 73.8 |

| Home monitoring (H2) | Social connectivity (H5) | |||||||

| Disagree | 11.7 | 13.1 | Disagree | 33.1 | 34.6 | |||

| Neutral | 18.9 | 25.5 | Neutral | 33.3 | 47.5 | |||

| Agree | 69.4 | 61.1 | Agree | 33.6 | 64.5 | |||

| Activity motivation (H3) | Shared access (H6) | |||||||

| Disagree | 24.2 | 26.7 | Disagree | 23.2 | 27.9 | |||

| Neutral | 31.4 | 42.8 | Neutral | 23.2 | 36.8 | |||

| Agree | 44.4 | 65-5 | Agree | 53.6 | 63.3 | |||

| Effort expectancy | ||||||||

| Easy to use (I1.1) | Customizable (I2.1) | Autonomous (I4.1) | ||||||

| Disagree | 2.2 | 18.5 | Disagree | 3.0 | 18.9 | Disagree | 3.7 | 28.3 |

| Neutral | 5.4 | 28.4 | Neutral | 7.5 | 28.0 | Neutral | 9.6 | 36.1 |

| Agree | 92.4 | 50.9 | Agree | 89.5 | 51.7 | Agree | 86.7 | 51.3 |

| Intuitive (I1.2) | Tailored (I2.2) | Seamless (I4.2) | ||||||

| Disagree | 2.2 | 11.1 | Disagree | 2.7 | 14.7 | Disagree | 2.6 | 21.9 |

| Neutral | 6.5 | 28.4 | Neutral | 7.7 | 33.3 | Neutral | 5.1 | 27.0 |

| Agree | 91.3 | 51.3 | Agree | 89.6 | 51.4 | Agree | 92.3 | 50.9 |

| Easy to learn (I1.3) | Trustworthy (I3.1) | Effort expectancy | ||||||

| Disagree | 3.1 | 23.1 | Disagree | 2.5 | 19.4 | Disagree | 7.3 | 19.8 |

| Neutral | 6.8 | 35.7 | Neutral | 5.2 | 15.4 | Neutral | 47.8 | 48.5 |

| Agree | 90.1 | 50.9 | Agree | 92.3 | 51.7 | Agree | 44.9 | 54.2 |

| Quickly usable (I1.4) | Warrantied (I3.2) | |||||||

| Disagree | 2.4 | 13-3 | Disagree | 3.4 | 28.6 | |||

| Neutral | 5.9 | 30.1 | Neutral | 8.1 | 36.6 | |||

| Agree | 91.7 | 51.1 | Agree | 88.5 | 50.9 | |||

| Facilitating conditions | ||||||||

| Availability of usage instructions (J1) | Availability of close people (J4) | Fit to daily life (J7) | ||||||

| Disagree | 3.2 | 8.2 | Disagree | 34.1 | 39.0 | Disagree | 2.7 | 11.8 |

| Neutral | 8.2 | 22.8 | Neutral | 27.5 | 49.6 | Neutral | 10.0 | 25.0 |

| Agree | 88.6 | 52.5 | Agree | 38.4 | 57.4 | Agree | 87.3 | 52.9 |

| Availability of a professional for questions (J2) | Availability of colleagues/friends (J5) | Fit to household (J8) | ||||||

| Disagree | 5.1 | 42.9 | Disagree | 26.9 | 35.9 | Disagree | 4.4 | 10.9 |

| Neutral | 10.9 | 44.4 | Neutral | 35.7 | 46.3 | Neutral | 11.2 | 27.3 |

| Agree | 84.0 | 49.9 | Agree | 37.4 | 60.9 | Agree | 84.4 | 53.8 |

| Availability of a professional when problems (J3) | Availability of own knowledge (J6) | Facilitating conditions | ||||||

| Disagree | 4.1 | 27.5 | Disagree | 24.8 | 23.5 | Disagree | 5.8 | 6.9 |

| Neutral | 6.8 | 36.9 | Neutral | 18.9 | 38.0 | Neutral | 47.3 | 39.5 |

| Agree | 89.1 | 50.9 | Agree | 56.3 | 63.8 | Agree | 46.9 | 63.7 |

| Social influences | ||||||||

| Meaning to important others (K1) | Prestigious image (K3) | Social influences | ||||||

| Disagree | 25.3 | 27.7 | Disagree | 41.1 | 36.1 | Disagree | 42.5 | 29.4 |

| Neutral | 55.1 | 48.0 | Neutral | 40.9 | 50.3 | Neutral | 47.7 | 59.0 |

| Agree | 19.6 | 79.0 | Agree | 18.0 | 75.3 | Agree | 9.8 | 85.1 |

| Meaning to opinion makers (K2) | Modern image (K4) | |||||||

| Disagree | 36.7 | 29.7 | Disagree | 16.7 | 23.7 | |||

| Neutral | 47.3 | 53.9 | Neutral | 32.8 | 41.0 | |||

| Agree | 16.0 | 78.4 | Agree | 50.5 | 62.5 | |||

| Hedonic motivation | ||||||||

| Entertaining (L1) | Versatile (L5) | Trending (L9) | ||||||

| Disagree | 23.0 | 18.6 | Disagree | 14.8 | 15.2 | Disagree | 17.8 | 18.1 |

| Neutral | 33.1 | 40.2 | Neutral | 36.5 | 39.2 | Neutral | 28.0 | 39.2 |

| Agree | 43.9 | 71.4 | Agree | 48.7 | 66.6 | Agree | 54.2 | 64.1 |

| Enjoyable (L2) | Fun (L6) | Variegating (L10) | ||||||

| Disagree | 22.6 | 12.1 | Disagree | 18.9 | 17.1 | Disagree | 27.6 | 25.7 |

| Neutral | 32.3 | 38.2 | Neutral | 32.6 | 35.6 | Neutral | 35.9 | 46.4 |

| Agree | 45.1 | 75.1 | Agree | 48.5 | 70.4 | Agree | 36.5 | 69.0 |

| Convenient (L3) | Pleasant (L7) | Hedonic motivation | ||||||

| Disagree | 9.8 | 8.3 | Disagree | 18.7 | 5.2 | Disagree | 22.9 | 8.5 |

| Neutral | 21.9 | 24.3 | Neutral | 22.9 | 23.9 | Neutral | 47.7 | 48.1 |

| Agree | 68.3 | 62.7 | Agree | 58.4 | 72.8 | Agree | 29.4 | 81.9 |

| Curiosity-inducing (L4) | Relieving (L8) | |||||||

| Disagree | 16.9 | 6.2 | Disagree | 10.9 | 6.7 | |||

| Neutral | 18.9 | 22.6 | Neutral | 21.5 | 20.2 | |||

| Agree | 64.2 | 68.0 | Agree | 67.6 | 64.9 | |||

| Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased dependence | ||||||||

| Dependence (M1.1) | Loss of control (M1.2) | Increased dependence | ||||||

| Disagree | 42.7 | 54.1 | Disagree | 45.6 | 58.7 | Disagree | 46.2 | 56.4 |

| Neutral | 23.0 | 49.1 | Neutral | 23.0 | 41.8 | Neutral | 32.4 | 44.8 |

| Agree | 34.3 | 42.5 | Agree | 31.4 | 40.1 | Agree | 21.4 | 39.2 |

| Costs | ||||||||

| Costs exceeding benefits. (M2.1) | Expensive maintenance (M2.2) | Costs | ||||||

| Disagree | 16.4 | 76.4 | Disagree | 12.2 | 73.5 | Disagree | 14.8 | 75.5 |

| Neutral | 23.8 | 57.3 | Neutral | 19.3 | 49.4 | Neutral | 28.2 | 55.9 |

| Agree | 59.8 | 38.1 | Agree | 68.5 | 44.5 | Agree | 57.0 | 38.6 |

| Privacy | ||||||||

| Data misuse (M3.1) | Data used unforeseeable (M3.2) | Privacy | ||||||

| Disagree | 17.5 | 63.9 | Disagree | 16.1 | 61.3 | Disagree | 17.9 | 62.6 |

| Neutral | 18.3 | 56.8 | Neutral | 16.5 | 56.1 | Neutral | 20.5 | 57.1 |

| Agree | 64.2 | 42.7 | Agree | 67.4 | 44.3 | Agree | 61.6 | 42.3 |

| Other risks | ||||||||

| Overwhelming (M4.1) | Non-essential luxuries (M6) | Replace contact with others (M8.1) | ||||||

| Disagree | 51.8 | 59.7 | Disagree | 29.6 | 76.3 | Disagree | 59.0 | 55.5 |

| Neutral | 21.5 | 36.3 | Neutral | 24.3 | 52.8 | Neutral | 22.4 | 42.6 |

| Agree | 26.7 | 38.4 | Agree | 46.1 | 29.4 | Agree | 18.6 | 35.9 |

| Cumbersome (M4.2) | Source of problems (M7.1) | Lack of human interaction (M8.2) | ||||||

| Disagree | 36.9 | 62.7 | Disagree | 25.7 | 69.9 | Disagree | 54.8 | 57.7 |

| Neutral | 26.6 | 47.3 | Neutral | 29.4 | 51.6 | Neutral | 22.1 | 43.4 |

| Agree | 36.5 | 36.3 | Agree | 44.9 | 35.4 | Agree | 23.1 | 33.4 |

| Go less out of house (M5) | Insecure (M7.2) | Other risks | ||||||

| Disagree | 67.1 | 54.7 | Disagree | 27.1 | 67.0 | Disagree | 56.5 | 61.1 |

| Neutral | 22.5 | 36.9 | Neutral | 26.5 | 52.0 | Neutral | 34.7 | 34.8 |

| Agree | 10.4 | 38.0 | Agree | 46.4 | 36.7 | Agree | 8.8 | 25.7 |

| Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | Sample | Intent. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance costs | ||||||||

| Discount on insurance premium (N1) | Reimbursement of purchase costs (N3) | Insurance costs | ||||||

| Disagree | 11.5 | 23.8 | Disagree | 22.4 | 40.6 | Disagree | 20.7 | 31.6 |

| Neutral | 24.2 | 38.7 | Neutral | 27.2 | 43.0 | Neutral | 39.4 | 46.8 |

| Agree | 64.3 | 57.3 | Agree | 50.4 | 55.8 | Agree | 39.9 | 60.0 |

| Automatic premium adjustment (N2) | ||||||||

| Disagree | 18.2 | 32.0 | ||||||

| Neutral | 29.5 | 39.9 | ||||||

| Agree | 52.3 | 59.9 | ||||||

| Insurance prevention services | ||||||||

| Advice from insurer (N4) | Individual offers from insurer (N6) | Insurance prevention services | ||||||

| Disagree | 18.0 | 26.5 | Disagree | 22.6 | 37.5 | Disagree | 23.1 | 31.7 |

| Neutral | 26.8 | 35.8 | Neutral | 25.9 | 36.6 | Neutral | 38.8 | 43.7 |

| Agree | 55.2 | 62.6 | Agree | 51.5 | 60.2 | Agree | 38.1 | 64.8 |

| Early warning from insurer (N5) | ||||||||

| Disagree | 20.7 | 34.6 | ||||||

| Neutral | 29.8 | 40.8 | ||||||

| Agree | 49.5 | 59.9 | ||||||

| Interest for insurance offering | ||||||||

| Future SH insurance intention (N7) | Future SH insurance plan (N8) | Interest for insurance offering | ||||||

| Disagree | 28.2 | 23.4 | Disagree | 31.3 | 16.0 | Disagree | 35.3 | 22.5 |

| Neutral | 37.5 | 47.5 | Neutral | 34.3 | 44.5 | Neutral | 37.8 | 49.5 |

| Agree | 34.3 | 71.5 | Agree | 34.4 | 83.4 | Agree | 26.9 | 82.5 |

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.743 | <0.001 | *** |

| Health benefits (G3.1–G3.5, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.410 | 0.026 | * |

| Agree | 0.265 | 0.257 | |

| Facilitating conditions (J1–J8, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 1.316 | 0.016 | * |

| Agree | 1.406 | 0.011 | * |

| Social influences (K1–K4, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.330 | 0.045 | * |

| Agree | 0.581 | 0.084 | . |

| Hedonic motivation (L1–L10, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 1.331 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | 2.375 | <0.001 | *** |

| Costs (M2.1–M2.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.692 | 0.009 | ** |

| Agree | −0.945 | <0.001 | *** |

| Other risks (M4.1–M8.2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.689 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | −0.946 | 0.002 | ** |

| Insurance prevention services (N4–N6, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.273 | 0.186 | |

| Agree | 0.055 | 0.802 | |

| Interest for insurance offering (N7–N8, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.647 | <0.001 | *** |

| Agree | 1.726 | <0.001 | *** |

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −0.457 | <0.001 | *** |

| Really strenuous activities (D1.2, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Often | 0.170 | 0.146 | |

| Loneliness (D5, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Often | 0.308 | 0.067 | . |

| Cultural activity level (D6.1, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.386 | 0.009 | ** |

| Often | 0.431 | 0.100 | |

| Outing level (D6.6, baseline: rarely) | |||

| Regularly | 0.342 | 0.008 | ** |

| Often | 0.443 | 0.012 | * |

| -Estimate | p-Value | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.834 | <0.001 | *** |

| Knowledge level (A1, baseline: poor) | |||

| Mediocre | 0.609 | <0.001 | *** |

| Good | 1.274 | 0.001 | *** |

| Convenience application (B1, baseline: dislike) | |||

| Neutral | −0.055 | 0.855 | |

| Like | 1.360 | <0.001 | *** |

| Health application (B2, baseline: dislike) | |||

| Neutral | 0.606 | 0.003 | ** |

| Like | 1.228 | <0.001 | *** |

| Age (A2, baseline: 45–54 years) | |||

| 55–64 years | −0.412 | 0.029 | * |

| 65–74 years | −0.389 | 0.048 | * |

| 75+ years | −0.620 | 0.028 | * |

| Gender (A3, baseline: female) | |||

| Male | 0.409 | 0.006 | ** |

| Home ownership (C5, baseline: rent) | |||

| Ownership | 0.394 | 0.012 | * |

| Marriage/partnership (C6.1, baseline: no) | |||

| Yes | −0.234 | 0.144 | |

| Technology experimenter (E1, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.295 | 0.165 | |

| Agree | 1.255 | <0.001 | *** |

| Technology pioneer (E2, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | 0.225 | 0.244 | |

| Agree | 0.790 | <0.001 | *** |

| Mistake avoider (E4, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.102 | 0.568 | |

| Agree | 0.465 | 0.015 | * |

| Familiarity preferer (E5, baseline: disagree) | |||

| Neutral | −0.361 | 0.057 | . |

| Agree | −0.407 | 0.023 | * |

| Life insurance (F1.5, baseline: Yes) | |||

| No | 0.401 | 0.022 | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iten, R.; Wagner, J.; Zeier Röschmann, A. On the Adoption of Smart Home Technology in Switzerland: Results from a Survey Study Focusing on Prevention and Active Healthy Aging Aspects. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 370-413. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7010015

Iten R, Wagner J, Zeier Röschmann A. On the Adoption of Smart Home Technology in Switzerland: Results from a Survey Study Focusing on Prevention and Active Healthy Aging Aspects. Smart Cities. 2024; 7(1):370-413. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleIten, Raphael, Joël Wagner, and Angela Zeier Röschmann. 2024. "On the Adoption of Smart Home Technology in Switzerland: Results from a Survey Study Focusing on Prevention and Active Healthy Aging Aspects" Smart Cities 7, no. 1: 370-413. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7010015

APA StyleIten, R., Wagner, J., & Zeier Röschmann, A. (2024). On the Adoption of Smart Home Technology in Switzerland: Results from a Survey Study Focusing on Prevention and Active Healthy Aging Aspects. Smart Cities, 7(1), 370-413. https://doi.org/10.3390/smartcities7010015