Abstract

Cultural heritage institutions face a critical challenge in engaging Generation Z, a demographic of digital natives with high expectations for interactive and immersive experiences. While Virtual Reality (VR) offers a promising solution, many implementations are dismissed as superficial “gimmicks,” lacking a theoretical foundation for effective design. To bridge this gap, we develop and validate an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) to explain the psychological mechanisms influencing Generation Z’s adoption of museum VR. Employing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design, we analyzed 566 survey responses using CB-SEM and conducted 20 in-depth interviews. Our findings establish Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Enjoyment as the primary direct drivers of intention to use, with Immersion and Content Quality acting as crucial antecedents. This research delivers a dual contribution: theoretically, we extend technology acceptance theory for the specific context of museum VR and young audiences; practically, we offer an empirically grounded framework with actionable principles that empowers curators and designers to create more meaningful and resonant cultural heritage experiences.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage institutions are at a critical juncture. In an increasingly digital world, they face the profound challenge of engaging a new generation of visitors for whom immersive and interactive experiences are not a novelty, but an expectation. Generation Z, born between 1995 and 2010 [1], has rapidly become a key audience segment, in some cases accounting for over 60% of visitors at major national museums [2]. As “digital natives” [3], this demographic possesses high levels of digital literacy and a distinct preference for personalized, participatory, and media-rich content [4]. This presents a fundamental conflict with traditional exhibition methods, which often rely on static displays, linear pathways, and text-based explanations—formats that frequently fail to meet the expectations of this young audience [5]. Without a strategic evolution in engagement practices, museums risk a growing disconnect with their future patrons, leading to reduced reach and a diminished role as influential cultural voices.

In response to this strategic imperative, Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a powerful medium for bridging this generational gap. By moving beyond the physical limitations of the gallery space, VR offers the potential to transform cultural heritage from a static monologue into a dynamic, embodied dialogue. Its capacity for high levels of immersion and interactivity can significantly enhance visitors’ emotional resonance and cognitive participation with cultural content [6,7]. VR reshapes the narrative logic of heritage by overcoming spatiotemporal constraints, allowing visitors to witness historical events, explore inaccessible sites, or deconstruct artistic processes in ways that promote deeper knowledge acquisition and strengthen memory retention [8,9,10]. This potential has not gone unnoticed; leading institutions worldwide have actively deployed VR, from the Louvre’s Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass to the Tate Modern’s Ochre Atelier, signaling a sector-wide move towards creating more profound, immersive visitor experiences.

However, the mere adoption of technology does not guarantee meaningful engagement. Despite a surge in development, many VR projects within the curatorial field are critiqued for being technologically driven “gimmicks” rather than narratively integrated experiences [11]. Often, they lack deep integration with core cultural narratives and fail to trigger the intended cultural resonance and learning [12]. This criticism aligns with broader concerns in digital museology regarding “technological solutionism,” where the focus on a tool’s novelty overshadows its pedagogical and interpretive purpose [13]. This creates a critical research gap: while museums are investing heavily in VR, there is a lack of systematic, evidence-based understanding of how their target young audiences actually perceive and decide to adopt these technologies. Without a robust theoretical model, the design and evaluation of museum VR risk remaining a matter of intuition rather than informed strategy.

This challenge is magnified when considering the unique characteristics of Generation Z. Their technology acceptance patterns differ markedly from previous cohorts. Heavily influenced by social media ecosystems, they value peer recommendations and user-generated content, making Subjective Norm a powerful driver of their behavior [14]. Furthermore, their engagement is often predicated on hedonic motivations; they gravitate towards experiences that are not only useful but also entertaining, emotionally resonant, and gamified. These traits suggest that traditional technology acceptance models, which often prioritize utilitarian factors like perceived usefulness and ease of use, may be insufficient to capture the complex decision-making process of this audience in a cultural context. Yet, specific research modeling Generation Z’s acceptance of museum VR remains notably limited.

In this study, we focus on on-site (in-museum) VR experiences, where visitors engage with immersive content during a physical museum visit. Prior research suggests that digitally mediated museum experiences, including VR, can enhance visitors’ willingness to participate in physical on-site visits, indicating a complementary rather than substitutive relationship between virtual engagement and place-based heritage consumption [15,16]. Moreover, digital heritage scholarship emphasizes that immersive digitization is intended to enrich interpretation and access to artefacts in situ rather than replace or decontextualize them [17]. While at-home or online VR exhibitions represent an important parallel domain [18], they involve different usage contexts and adoption mechanisms and are therefore beyond the scope of the present model.

To address this gap and provide a rigorous foundation for future practice, this study develops and validates an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) tailored to Generation Z in the museum context. We aim to systematically explore the psychological mechanisms that influence their intention to use museum VR experiences. Specifically, this research seeks to answer the following questions:

- What are the key factors, including experiential and social variables, that influence Generation Z visitors’ intention to use museum VR?

- How do these factors interact to shape their acceptance behaviors and perceptions of value?

To this end, we employ an explanatory sequential mixed-methods approach, combining a large-scale quantitative survey (N = 566) analyzed via covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) with in-depth, semi-structured interviews (N = 20) for qualitative validation. This study offers a multi-faceted contribution. For HCI and information systems scholarship, it presents theoretical novelty by developing and validating a context-specific extension of technology acceptance theory. For the cultural heritage sector, it provides demographic novelty through the first large-scale investigation into Generation Z’s unique adoption behaviors, yielding an empirically grounded framework and actionable design principles. Finally, it delivers a robust empirical contribution through a mixed-methods study combining a large-scale survey (N = 566) with in-depth qualitative insights, ensuring the generalizability and practical relevance of its findings for creating more effective and resonant VR experiences.

2. Related Research

2.1. Museums in the Post-Digital Paradigm

Contemporary museology is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, moving beyond its traditional role as a passive repository of artifacts to become a dynamic forum for dialogue and participatory experience [19]. This evolution is largely driven by the digital turn, which has profoundly reshaped institutional practices and public engagement. Within this context, scholars identify the emergence of the “post-digital museum,” a paradigm where digital technologies are not novel accessories but are fully integrated into the institution’s strategic and operational fabric [13]. A key consequence of this shift is the redistribution of interpretive authority; digital tools are increasingly leveraged to foster co-creative meaning-making, thereby repositioning visitors as active agents in their own learning journeys [20]. This reorientation places the “visitor experience”—a multifaceted construct of cognitive, affective, and social dimensions—at the center of modern curatorial practice [21]. Understanding and enhancing this experience has subsequently become a primary objective for the deployment of new technologies, including immersive media like Virtual Reality (VR).

2.2. Modeling Technology Acceptance in Experiential Contexts

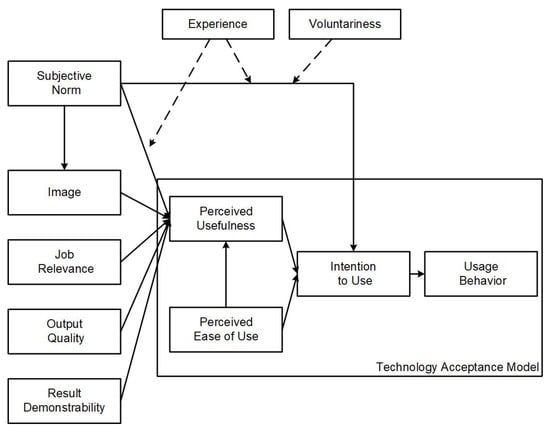

To systematically analyze the adoption of such experiential technologies, this study employs the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as its foundational framework. As one of the most robust theories of technology adoption, TAM posits that an individual’s behavioral intention to use a new technology is primarily determined by two core beliefs: Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) [22]. The model’s subsequent extension, TAM2, increased its explanatory power by incorporating social influence processes, such as subjective norm, providing a flexible theoretical basis for integrating external variables pertinent to specific contexts (see Figure 1) [23]. Its proven validity and adaptability make TAM a suitable framework for building a context-specific model that can deconstruct the acceptance mechanisms of VR within the unique, experientially focused environment of a museum.

Figure 1.

Proposed TAM2—Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Solid arrows indicate direct effects; dashed arrows indicate moderating effects.

2.3. VR Acceptance in Cultural Heritage and the Gen Z Gap

The application of VR in cultural heritage is not a new phenomenon; leading institutions have launched a variety of projects to enhance visitor engagement (see Table 1). However, when applied to this sector, the original TAM’s utilitarian focus proves insufficient. A consistent finding in the literature is the centrality of hedonic and affective factors in driving user engagement [15,24]. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that variables such as perceived enjoyment, playfulness, and immersion are significant predictors of use intention in virtual museum contexts [10,25,26]. Comprehensive surveys of immersive technologies in cultural heritage confirm that VR’s capacity to generate a strong sense of “presence” is a key affordance for creating compelling visitor experiences [6,27]. Recent XR research also demonstrates the growing role of augmented reality in heritage learning; for example, Motiv-ARCHE enables the co-creation of AR educational content to increase visitor motivation in cultural and natural heritage contexts [28]. This experiential focus is particularly salient for Generation Z, the cohort of “digital natives” who now constitute a primary museum demographic [3]. The expectations of this generation have been shaped by a media ecosystem predicated on interactivity, personalization, and social feedback, leading to a pronounced preference for digital experiences that are not only functional but also entertaining and participatory [14,29].

Table 1.

Selected Museum VR Experiences.

Despite this understanding, a clear research gap persists. Few studies have systematically integrated the unique social and hedonic characteristics of Generation Z into a comprehensive acceptance model for museum VR [30,31]. Consequently, an empirically validated framework is lacking that holistically explains the psychological mechanisms driving this specific demographic’s adoption behavior. Furthermore, contextual factors pertinent to on-site public installations, such as cybersickness or hygiene concerns with shared headsets, are often neglected in theoretical models. This study, therefore, addresses this gap by proposing a model tailored specifically to the characteristics and context of Generation Z museum visitors. To achieve this, the following section synthesizes the identified theoretical constructs from the literature into a cohesive, multi-dimensional research model and derives a series of testable hypotheses.

3. Proposed Model and Hypotheses

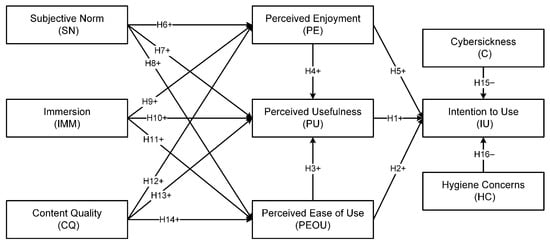

To address the identified research gap, this study develops a multi-dimensional model that synthesizes cognitive, hedonic, social, and contextual factors to explain Generation Z’s acceptance of museum VR. While grounded in the robust theoretical foundations of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [22], our proposed model is substantially extended to account for the unique characteristics of the cultural heritage context and the target demographic. Specifically, drawing from the insights established in our literature review, the model (depicted in Figure 2) integrates key variables identified as critical in prior work, including experiential constructs (Perceived Enjoyment, Immersion, Content Quality), social dynamics (Subjective Norm), and context-specific perceived risks (Cybersickness, Hygiene Concerns). This integrated approach moves beyond a purely utilitarian view of technology adoption to provide a more holistic and nuanced explanation of user acceptance in an experientially rich informal learning environment.

Figure 2.

The Proposed Research Model.

3.1. Core TAM Constructs: Perceived Usefulness and Ease of Use

Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) are the foundational pillars of TAM. PU refers to the degree to which an individual believes that using a technology will enhance their experience or performance, while PEOU is the extent to which they believe using it will be free of effort [22]. In the context of museum VR, PU relates to how much visitors feel the technology enriches their understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage. PEOU pertains to the perceived simplicity of operating the VR headset and interacting with the virtual environment. Consistent with decades of TAM research, PU is expected to be a primary determinant of usage intention. Furthermore, a system that is easier to use is often perceived as more useful, as it reduces the cognitive load required to achieve a goal [23]. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Perceived usefulness positively influences Generation Z museum visitors’ intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Perceived ease of use positively influences Generation Z museum visitors’ intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Perceived ease of use positively influences perceived usefulness.

3.2. Hedonic Motivation: Perceived Enjoyment

Given that museum visits are voluntary, leisure-time activities, hedonic motivations are likely to play a crucial role. Perceived Enjoyment (PE) is defined as the pleasure and fun derived from using a technology itself, independent of any performance consequences [32]. For Generation Z, an audience that prioritizes experiential and entertaining content, enjoyment is a central component of a digital product’s value proposition [29]. When visitors find the VR experience intrinsically enjoyable, they are more willing to invest the cognitive effort required for exploration and learning. This heightened engagement leads them to discover more of the exhibit’s educational value, thereby enhancing their perception of the technology’s pedagogical usefulness. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Perceived enjoyment positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Perceived enjoyment positively influences intention to use.

3.3. Experiential and Social Antecedents

Based on the literature review, we identified three key external variables that are expected to influence the core TAM constructs: Subjective Norm (SN), Immersion (IMM), and Content Quality (CQ).

Subjective Norm (SN) reflects the social pressure an individual feels to perform a certain behavior [23]. For the highly connected Generation Z, who rely heavily on peer recommendations and social media trends [14], the opinions of significant others are powerful influencers. Recent work specifically highlights the significant positive effect of social influence on attitude in the context of museum VR for young users [30]. Positive social cues are therefore expected to enhance the perceived value, enjoyment, and usability of the VR experience.

Immersion (IMM) is a central affordance of VR, representing the psychological state of being enveloped by and absorbed in the virtual environment. A higher degree of immersion can intensify the experience, making it more engaging, enjoyable, and memorable [10]. This heightened engagement, closely related to the concept of presence, is fundamental to the user experience in heritage tourism [27]. It can also make the technology seem more effective as an educational tool (more useful) and more intuitive to interact with (easier to use).

Content Quality (CQ) refers to the perceived quality of the information and presentation within the VR system, including its accuracy, richness, and aesthetic appeal. In the specific context of cultural heritage, CQ also involves the narrative coherence and interpretative depth through which VR contextualizes artefacts historically and culturally. Rather than treating “content” as neutral information, museum VR content is expected to function as heritage interpretation—i.e., helping visitors construct meaning, understand historical backgrounds, and emotionally connect to cultural narratives [9,12]. High-quality content is fundamental to a positive visitor experience and engagement [15]. It enhances the system’s credibility and educational value (PU), makes the experience more pleasurable (PE), and contributes to a more seamless and understandable interaction (PEOU).

Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Subjective Norm positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Subjective Norm positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Subjective Norm positively influences perceived ease of use.

Hypothesis 9 (H9).

Immersion positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Immersion positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 11 (H11).

Immersion positively influences perceived ease of use.

Hypothesis 12 (H12).

Content Quality positively influences perceived enjoyment.

Hypothesis 13 (H13).

Content Quality positively influences perceived usefulness.

Hypothesis 14 (H14).

Content Quality positively influences perceived ease of use.

3.4. Perceived Risks: Cybersickness and Hygiene Concerns

Finally, the model incorporates two potential inhibitors specific to the on-site use of shared VR headsets. Cybersickness (C) refers to symptoms of discomfort, such as nausea or dizziness, that can occur during VR exposure [33]. Such negative physical experiences are widely recognized as a significant barrier that can deter users from future use [34]. Hygiene Concerns (HC) relate to user apprehension regarding the cleanliness of shared devices that come into direct contact with the face. In public settings like museums, inadequate sanitation of shared equipment can be a major deterrent, negatively impacting a visitor’s willingness to engage with the technology [12]. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 15 (H15).

Cybersickness negatively influences intention to use VR.

Hypothesis 16 (H16).

Hygiene concerns negatively influence intention to use VR.

4. Materials and Methods

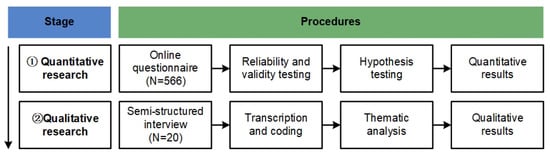

To empirically test the proposed model and answer our research questions, this study adopted an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design [35]. This approach is particularly well-suited for our objectives, as it allows for a comprehensive investigation wherein quantitative findings provide a broad overview of the relationships between variables, and subsequent qualitative data offer deep, contextualized explanations for those statistical results [36]. The research was structured in two distinct phases: first, a large-scale quantitative survey was conducted to validate the structural model; second, semi-structured interviews were carried out with a subset of survey participants to elaborate on and interpret the quantitative findings. The overall research procedure is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The explanatory sequential mixed-methods research procedure.

4.1. Phase 1: Quantitative Study

4.1.1. Qualitative Participants and Procedure

The target population for this study was Chinese members of Generation Z (born between 1995 and 2010) with prior experience using VR in a museum context. Participants were recruited online through a purposive sampling strategy between October 2024 and May 2025. Recruitment announcements, containing a link to the online survey, were disseminated across more than 20 public and semi-public social media groups focused on VR technology and museum enthusiasts.

The online survey began with an informed consent form. After consent, participants viewed a 60-s recording of an exemplar interaction with the VR application Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass (see Figure 4). The stimulus was recorded by the authors from the officially released version obtained via authorized channels and was streamed within the survey session for research purposes only; it was not shared or redistributed outside the study [37]. Participants then completed the main questionnaire. In total, 628 responses were collected; after excluding invalid entries (e.g., unusually short completion times, failed attention checks), 566 valid responses remained for analysis, yielding an effective response rate of 90.1%. The quantitative sample (N = 566) is sufficient for robust CB-SEM analysis [38].

Figure 4.

Promotional stills from the VR application Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass. All four images were obtained from the official Steam store page and are used here for academic purposes [37].

4.1.2. Measures

A 29-item questionnaire was developed to measure the nine constructs in our proposed model. All items were adapted from established scales in the information systems and HCI literature to ensure content validity. The questionnaire consisted of two sections: the first collected demographic information, while the second contained the measurement items for the constructs. All perceptual items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (Strongly Disagree) to “7” (Strongly Agree). Consistent with TAM2 [23], the measurement items for Subjective Norm (SN), Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), and Intention to Use (IU) were adapted from the original TAM/TAM2 instruments. To fit the museum VR context, we made only minor wording adjustments (e.g., replacing “system” with “museum VR experience/content”) while preserving the original construct meanings. The constructs and their corresponding measurement items are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Constructs and Measurement Items.

4.1.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

The quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 28.0 with a covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) approach, which is appropriate for theory testing and confirmation [38]. The analysis followed a two-step procedure. First, the measurement model was assessed for reliability and validity. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (). Convergent validity was assessed by examining factor loadings, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Fornell and Larcker criterion [47]. Second, after establishing a valid and reliable measurement model, the structural model was tested to evaluate the hypothesized relationships among the constructs. The model’s goodness-of-fit was assessed using multiple indices, including the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

4.2. Phase 2: Qualitative Study

4.2.1. Quantitative Participants and Procedure

At the end of the quantitative survey, participants were asked whether they were willing to take part in a follow-up in-depth interview. From the pool of volunteers who provided contact information, we purposively selected 20 participants, who then completed the qualitative phase. The interviews were conducted online in Mandarin Chinese, with each session lasting between 40 and 60 min. The interview protocol was semi-structured, designed to elicit rich, detailed narratives about participants’ perceptions and experiences related to the constructs in our model. An example prompt was, “Can you describe a time when a museum VR experience felt particularly immersive? How did that feeling of immersion affect your overall opinion of the experience?” (see Appendix A for the full interview guide).

4.2.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

The qualitative data from the interview recordings were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic analysis [35]. The analysis involved a process of open and axial coding. Two of the authors independently coded the transcripts to identify initial themes and patterns. They then met to compare their codes, discuss discrepancies, and collaboratively refine the coding scheme. A third author acted as an auditor to ensure the credibility and rigor of the analysis by reviewing the final thematic structure against the raw data. This iterative process continued until theoretical saturation was reached, which occurred after analyzing 18 transcripts; the final two interviews were used to confirm that no new major themes were emerging. This qualitative analysis provided nuanced explanations for the statistical relationships observed in the quantitative phase.

4.3. Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and exempted by the Academic Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University (Approval No. JNU202506RB030). All participants were informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, and data usage policies before providing their consent. Data were collected anonymously and were used exclusively for academic research purposes.

5. Results

This section presents the key findings derived from both the quantitative and qualitative analyses. The quantitative component begins with an assessment of the measurement model’s reliability and validity, ensuring the robustness of the instrument. It then proceeds to evaluate the hypothesized structural relationships using covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM). The qualitative component involves a systematic coding and thematic analysis of interview data from twenty participants, resulting in four core themes. These themes complement and deepen the quantitative findings, providing a multidimensional understanding of Generation Z’s acceptance of VR technology in museum contexts.

5.1. Quantitative Results

5.1.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 628 survey responses were initially collected. After a data screening and cleaning process to remove incomplete or invalid entries, 566 valid responses were retained for analysis. All participants met the predefined inclusion criteria: born between 1995 and 2010, with prior experience using VR in a museum context. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the sample is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 566).

The gender distribution of the sample was relatively balanced, with 293 respondents identifying as male (51.8%) and 273 as female (48.2%). The majority of participants (53.5%) were born between 2000 and 2004, representing the core of Generation Z. The sample exhibited a high level of education, with 59.7% holding undergraduate degrees and 37.3% holding postgraduate degrees or higher. Regarding engagement with cultural heritage, most participants (68.6%) reported visiting museums “occasionally.” In terms of technology readiness, a significant portion of the sample identified as novices in VR, with 51.8% rating themselves as “slightly unskilled” and 27.4% as “not proficient at all.” This suggests that our findings are largely representative of a general young audience with prior museum VR exposure rather than a niche group of VR experts.

5.1.2. Measurement Model Assessment

A two-step approach was used to analyze the data. First, the measurement model was assessed for reliability and validity. As shown in Table 4, all constructs demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha () values ranging from 0.854 to 0.938, comfortably exceeding the recommended 0.7 threshold [48].

Table 4.

Reliability and convergent validity of constructs.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted. Convergent validity was established as all standardized factor loadings were above 0.7, all composite reliability (CR) values exceeded 0.8, and all average variance extracted (AVE) values were above the minimum requirement of 0.5 [47]. Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell and Larcker criterion. As presented in Table 5, the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlation with any other construct, confirming that each construct is distinct. Taken together, these results indicate that the measurement model is both reliable and valid.

Table 5.

Discriminant validity results. The diagonal elements (in bold) are the square root of AVE; off-diagonal elements are inter-construct correlations.

5.1.3. Structural Model Analysis

Second, the structural model was tested to evaluate the hypothesized relationships. An assessment of the model’s overall goodness-of-fit indicated an excellent fit with the data. Specifically, all key indices met or exceeded the established thresholds: the ratio of chi-square to degrees of freedom (/df) was 2.333 (recommended < 5.00), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) was 0.967 (recommended > 0.90), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.962 (recommended > 0.90), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.049 (recommended < 0.06) [49,50]. A comprehensive report of all fit indices is provided in Table 6, further confirming the model’s robustness.

Table 6.

Fit indices for the measurement and research models.

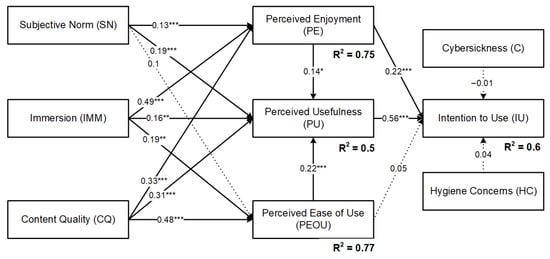

The results of the hypothesis tests are detailed in Table 7 and visualized in Figure 5. Out of the 16 hypotheses, 12 were supported. Specifically, Perceived Usefulness (PU) was the strongest predictor of Intention to Use (IU) (, ), strongly supporting H1. In contrast, the direct path from Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) to IU was not significant (, ), thus H2 was not supported. However, PEOU had a significant positive influence on PU (, ), supporting H3, indicating its role as an indirect determinant of intention.

Table 7.

Results of the Hypothesis Tests.

Figure 5.

Results of the structural model analysis. Note: * ; ** ; *** . indicates the proportion of variance explained by the predictors.

Perceived Enjoyment (PE) significantly and positively influenced both PU (, ) and IU (, ), supporting H4 and H5. This highlights the dual role of hedonic motivation in shaping both utilitarian perceptions and direct adoption intentions.

Among the external variables, Subjective Norm (SN) had a significant positive impact on PE (, ) and PU (, ), supporting H6 and H7. However, its influence on PEOU was not significant (H8 not supported; , ). Immersion (IMM) was a strong predictor for all three core TAM constructs, positively influencing PE (, ), PU (, ), and PEOU (, ), thus supporting H9, H10, and H11. Similarly, Content Quality (CQ) demonstrated significant positive effects on PE (, ), PU (, ), and PEOU (, ), supporting H12, H13, and H14.

Finally, neither of the perceived risk factors, Cybersickness (C) (, ) and Hygiene Concerns (HC) (, ), had a significant effect on IU. Therefore, H15 and H16 were not supported.

The model demonstrated substantial explanatory power. The antecedents collectively explained 75.0% of the variance in PE (), 50.0% in PEOU (), and 77.0% in PU (). Ultimately, the model accounted for 60.0% of the variance in Intention to Use ().

5.2. Qualitative Findings

Twenty in-depth, semi-structured interviews were analyzed to illuminate the mechanisms that underlie Generation Z’s adoption of museum-based VR. The following themes emerged from the data, providing nuanced explanations for the relationships observed in our quantitative model. All participant quotes have been translated from Mandarin Chinese.

5.2.1. Experiential Value as the Core Driver (H1, H3–H5, H9–H14)

Participants consistently emphasized that their intention to use museum VR was primarily driven by the quality of the experience itself, a concept encapsulating immersion, content, and enjoyment. Immersion (IMM) was frequently described as the catalyst for emotional engagement and the formation of durable memories, directly supporting its role as an antecedent to Perceived Enjoyment (PE) and Perceived Usefulness (PU). One participant vividly captured this sentiment:

“I felt like the painting came alive… It wasn’t just a flat image anymore. That kind of experience helps me remember the work much more clearly than just reading about it in a book.”(P03)

For some, immersion also fulfilled a desire for escapism and self-extension, allowing them to transcend the physical museum space:

“Sometimes I wish VR could transport me to another dynasty… It’s a satisfying escape from the pressures of daily life, a way to truly ’live’ in history for a moment.”(P08)

High-quality content (CQ) was deemed essential for building trust and sustaining engagement. Participants were quick to dismiss experiences that lacked aesthetic polish or narrative depth, viewing them as mere novelties rather than valuable cultural tools. This underscores CQ’s strong influence on PU, PE, and PEOU.

“If it looks like a cheap animation, I immediately lose interest. I would treat it as a toy, not as culture. The visual quality has to match the gravitas of the subject.”(P06)

Furthermore, well-designed user interfaces—a key component of Content Quality—were linked to a greater sense of control and ease of use, which in turn facilitated learning:

“A logical UI and intuitive interaction methods make it much easier for me to get started. This is directly related to how effectively I can learn from the content.”(P11)

Finally, Perceived Enjoyment (PE) acted as a crucial gateway to deeper learning, mediating the path to use intention. Participants indicated that fun was not a distraction from the educational mission but a prerequisite for it.

“If a VR experience can make me feel the same kind of pleasure I get from a game, then I will be genuinely interested in it and, as a result, understand the content much better.”(P01)

This enjoyment was also tied to feelings of emotional connection and cultural belonging, reinforcing the link between hedonic and utilitarian value:

“When I’m having fun in a museum VR, I feel emotionally understood and welcomed, as if this cultural space was designed specifically for me.”(P07)

5.2.2. Social Influence as a Catalyst and Currency (H6–H8)

The interviews strongly validated the significant role of Subjective Norm (SN) in shaping Generation Z’s perceptions and intentions. Participants frequently described peer recommendations and social media trends as powerful triggers for their curiosity and initial willingness to try a VR experience.

“If my close friends all say a VR exhibit is special and worth seeing, I’ll definitely make a point to go and try it. Their opinion acts as a quality filter for me.”(P02)

This influence extends beyond peers to mentors and digital influencers, whose endorsements are seen as credible signals of value, directly impacting Perceived Usefulness (PU).

“On TikTok, I saw a blogger share a video of a VR experience at an exhibition. The interesting interactions and beautiful visuals immediately caught my interest, which prompted me to visit that same weekend.”(P15)

Beyond being passive receivers of social influence, participants also viewed the VR experience as a form of social currency. The novelty and visual appeal of VR make it a valuable asset for content creation on their own social media platforms, fulfilling a desire for self-expression and online engagement.

“I enjoy sharing my daily life on social media. Experiencing VR would be a great opportunity to post unique content, which helps me get more attention and interaction online.”(P08)

However, a few participants expressed a stronger sense of internal motivation, suggesting that while social trends are influential, personal interest remains the ultimate gatekeeper.

“Unless I’m personally interested in the topic of the exhibition, no amount of recommendation would convince me to spend my time on it.”(P13)

5.2.3. Usability Barriers and Risk Adaptation (H2, H15, H16)

The qualitative data provided crucial insights into why Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU) did not directly impact intention, and why the perceived risks of Cybersickness (C) and Hygiene Concerns (HC) were not significant deterrents in the quantitative model.

Regarding PEOU, participants with less VR experience did report initial struggles with complex controllers, which could have been a barrier.

“The way the controller worked was a bit confusing at first… I spent a few minutes just trying to figure out how to simply grab an object.”(P03)

However, this hurdle was consistently described as minor and quickly surmountable, especially with brief guidance. This suggests that for this digitally native cohort, usability is a baseline expectation rather than a key driver of long-term intention.

“I’m confident I can pick up the controls for any new device quickly. As long as the museum offers a quick one-minute tutorial, I’ll be fine.”(P09)

Similarly, participants acknowledged experiencing mild cybersickness, such as dizziness or eyestrain, but framed it as an acceptable trade-off for a compelling experience. This supports the non-significant finding for H15.

“I did feel a bit dizzy when scenes changed too quickly, but it wasn’t a big deal… If the content is engaging enough, I’m perfectly okay with a little discomfort. It’s worth it.”(P01)

Hygiene concerns (H16) surfaced as a conditional, rather than absolute, barrier. While the thought of using a shared headset raised apprehension, this fear was easily mitigated by visible signs of sanitation, effectively neutralizing it as a major deterrent for most.

“It does touch my skin, and I don’t know who used it last, which is a bit unsettling.”(P06)

“But as long as it looks clean and they offer disposable wipes or protective covers, I’m completely fine with it. It’s a simple solution.”(P02)

These findings collectively suggest that Generation Z approaches museum VR with a pragmatic mindset, viewing minor usability challenges and physical risks not as deal-breakers, but as manageable costs in exchange for a novel and valuable cultural experience.

5.2.4. Design Opportunities for Future Engagement

Beyond validating the model, the interviews revealed a rich set of expectations and desires that offer clear design guidance for future museum VR experiences aimed at Generation Z. All 20 participants expressed a strong willingness to continue using museum VR, underscoring the technology’s long-term potential. Their suggestions clustered around three key themes.

Adding Personalized Content to Satisfy Exploratory Desire

A dominant theme was the desire for greater agency and personalization. Participants felt that future VR should move beyond linear, one-size-fits-all narratives to offer experiences tailored to individual interests and knowledge levels.

“The system could ask me a few questions at the start to gauge my interests. An art history enthusiast and a casual visitor want different things… I need deeper, more niche information, not just the basics.”(P02)

The idea of an AI-powered virtual guide was particularly popular, seen as a way to enable personalized, on-demand inquiry and provide companionship.

“It would be amazing if there were a virtual avatar, like a historian or the artist themself, who could answer all my questions in real-time, like ChatGPT. It would also keep me company when I visit alone.”(P13)

Enhancing Immersion Through Context-Specific Interaction

Participants expressed a desire for interaction methods that felt more natural and contextually appropriate than standard game controllers.

“Using a typical game controller in a museum feels a bit out of place… It would be much better to have more natural interaction methods, like eye-tracking to select objects or gesture controls to manipulate them. That would make it feel less like a game and more like a real exploration.”(P15)

Beyond interaction techniques, the interviews revealed that social context is itself an important dimension of how immersion is experienced in museum VR. Some participants envisioned VR as a shared adventure with friends or family, suggesting that being “in the same virtual scene” would amplify enjoyment and emotional engagement.

“If I could explore the same virtual space together with my friends, I’d be much more motivated to try it. It would feel like we are on an adventure together, not just me using a device alone.”(P09)

By contrast, others explicitly preferred solitary VR engagement, worrying that visible avatars or conspicuous co-visitors would break the narrative atmosphere and reduce immersion.

“If there were cartoon-like avatars of other users standing next to me, it would feel out of place and ruin the historical atmosphere. I would rather stay fully immersed by myself.”(P05)

A third group expressed interest in lightweight, asynchronous social features that do not intrude on their individual journey—for example, being able to access other visitors’ thoughts without directly encountering them inside the virtual scene.

“I’d like to see other visitors’ comments or reflections on the artwork, maybe as subtle floating text. But I don’t want to see everyone’s avatars running around, because that would distract me from the story.”(P04)

Addressing Barriers to Continued Use

Finally, while generally enthusiastic, participants raised several practical concerns that could dampen their long-term engagement. Privacy and the feeling of being watched in a public space was a recurring issue.

“I feel uncomfortable not knowing if others are watching me when I’m wearing the headset and moving my arms around… it feels a bit awkward.”(P06)

“If the VR area had some semi-enclosed partitions or was in a slightly separate room, I’d feel much safer and more relaxed.”(P15)

Cost was another significant consideration, with a strong expectation that such digital experiences should be integrated into the main museum admission.

“Even if it’s a small extra fee, I’d hesitate to pay it after already buying an entrance ticket. Museum VR should feel like a core part of the public service, not a commercial add-on.”(P18)

These findings provide clear, actionable insights for cultural heritage institutions to design VR experiences that are not only technologically impressive but also deeply resonant, user-centric, and sustainable in their appeal to the next generation of visitors.

6. Discussion

This study provides an integrated understanding of Generation Z’s adoption of museum VR by combining quantitative modeling with qualitative insights. The findings not only validate a robust model for predicting use intention but also offer nuanced explanations for the unique ways this digital-native cohort evaluates and engages with immersive cultural heritage technologies. Below, we discuss the theoretical contributions to the field of computing and cultural heritage, and the practical implications arising from these findings.

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research makes several contributions to the literature on technology acceptance and digital cultural heritage by developing and validating a context-specific model for a critical, yet understudied, demographic.

First, our findings confirm that Perceived Usefulness (PU) remains the single most powerful predictor of Generation Z’s intention to use museum VR (, ), reinforcing a core tenet of TAM [22]. This aligns with prior studies on immersive cultural heritage experiences within this journal [15,24]. However, our qualitative data enriches this finding, revealing that for this audience, “usefulness” is deeply intertwined with enhanced learning, emotional engagement, and memory retention. As one participant noted, the experience of a painting “coming alive” made it ”much more clearly” memorable (P03), validating VR’s pedagogical value in a heritage context [54].

Second, this study clarifies the shifting role of Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU). While PEOU significantly influenced PU (, ), its direct impact on intention was non-significant (H2 not supported). This finding, which deviates from the original TAM but echoes recent VR research [55,56], is powerfully explained by our qualitative data. Initial usability challenges were noted (P03), but they were consistently framed as minor and rapidly overcome by this digitally fluent cohort (P09). This suggests that for Generation Z users in experiential settings, ease of use has shifted from a primary motivator to a baseline “hygiene factor”; its presence is expected but does not directly drive adoption. This indirect role is also observed in non-immersive screen-based TAM studies, including web archives and conventional virtual exhibition websites, where PEOU tends to influence intention mainly through PU rather than as a direct predictor [41,57]. A clear contrast appears in VR acceptance. Traditional interfaces are adopted largely for utilitarian efficiency, whereas in our model intention is shaped by two parallel motives, usefulness and enjoyment. Consistent with digital museum research emphasizing playfulness [26], Perceived Enjoyment remains a direct driver, and in VR it is strongly supported by Immersion, a sensory and experiential dimension absent in standard video or web presentations. In addition, although TAM2 often reports a weak direct effect of Subjective Norm in voluntary non-immersive settings [23], SN is significant in our VR model, suggesting that social endorsement becomes more salient when users engage with an immersive and relatively novel medium. This nuanced role of PEOU and the prominence of experiential and social drivers constitute key theoretical contributions of this work.

Third, our model provides strong evidence for the dual importance of hedonic and experiential factors. Perceived Enjoyment (PE) emerged as a significant direct predictor of intention (, ), supporting the argument that in voluntary, informal learning contexts, hedonic motivation is not secondary but parallel to utilitarian goals [15]. Crucially, we identified Immersion (IMM) and Content Quality (CQ) as powerful antecedents. IMM was the strongest predictor of PE (, ), while CQ was a strong predictor for all core TAM constructs. This suggests that for Generation Z, a high-quality, immersive experience constitutes a form of “experiential authenticity” [10]. The value proposition is not just about accessing content, but about feeling a sense of presence within it [27], a sentiment captured by participants’ desire to “‘live’ in history for a moment” (P08). Beyond sensory immersion, a key contribution of museum VR lies in its interpretative and narrative function in cultural heritage learning. VR can support historical and cultural understanding by situating artefacts within embodied storyworlds, enabling visitors to experience spatial, temporal, and social contexts that are often inaccessible in physical galleries [31,54]. In this sense, VR contributes not merely by “delivering content”, but by creating experiential interpretation that strengthens meaning making, contextual learning, and emotional resonance with heritage narratives [9]. Accordingly, Content Quality in our model should be understood as a visitor-perceived proxy for interpretative quality, which helps explain its strong effects on Perceived Usefulness (meaningful learning) and Perceived Enjoyment (emotional connection). This interpretative role is also consistent with our interview data, in which participants repeatedly described VR as making heritage feel “alive” and historically situated.

Fourth, the study highlights the critical role of Subjective Norm (SN) as a catalyst for engagement ( for PU, for PE), a finding consistent with studies that have incorporated social influence into their models [30]. Our qualitative findings reveal that this is not just about social pressure, but about peer recommendations acting as “a quality filter” (P02) and the VR experience itself serving as ”social currency” for online self-expression (P08). This extends technology acceptance theory by framing social influence not just as a compliance mechanism, but as an integral part of the value discovery and identity-building process for this generation.

Finally, and perhaps most surprisingly, our mixed-methods approach offers a nuanced explanation for the non-significance of perceived risks. Neither Cybersickness (C) nor Hygiene Concerns (HC) were significant deterrents. The qualitative data reveal a pragmatic “cost-benefit” calculus: participants viewed these issues as manageable trade-offs for a compelling experience. Mild discomfort was “worth it” (P01) and hygiene fears were easily assuaged by simple measures like providing wipes (P02). This finding challenges the assumption that such physical factors are absolute barriers and suggests that for motivated young users in a cultural context, the perceived experiential rewards can significantly outweigh the perceived physical risks.

6.2. Practical and Design Implications

Our empirically validated model translates into a set of actionable recommendations for cultural heritage institutions aiming to strategically engage Generation Z. These implications are designed to guide curators, experience designers, and museum strategists in creating more effective and resonant immersive experiences.

- For Curators and Content Strategists: Prioritize Narrative Depth over Novelty. The finding that Content Quality is a cornerstone of the entire user experience (H12, H13, H14 supported) is a powerful directive. Resources should be invested in creating VR experiences with high-fidelity visuals, accurate historical information, and compelling, narrative-driven content. VR should be treated not as a tech demo, but as a digital curatorial medium. The goal is to leverage immersion to deepen the story of the artifact or heritage site, not merely to showcase the technology itself. More importantly, VR should be designed as a form of digital heritage interpretation that enables visitors to build cultural meaning, rather than a tool for superficial cultural consumption [9,12].

- For Marketing and Outreach Managers: Leverage Social Proof and Influencer Engagement. The strong influence of Subjective Norm (H6, H7 supported) confirms that for Generation Z, the path to adoption is often social. Marketing campaigns should be built around peer-to-peer sharing and collaboration with digital influencers in the realms of culture, history, and technology. Institutions can facilitate this by designing “shareable moments” within the VR experience and making it easy for visitors to capture and post their virtual journey, turning visitors into brand ambassadors.

- For Experience Designers and Developers: Design for Enjoyment and Manage Risks Proactively. Perceived Enjoyment being a direct driver of intention (H5 supported) means that incorporating elements of play, discovery, and interactivity is not a trivial addition but a core design requirement. Furthermore, while cybersickness and hygiene were not significant deterrents, they remain experiential frictions. Designers should proactively manage these by, for example, avoiding rapid virtual movements that induce motion sickness and working with front-of-house staff to ensure that sanitation protocols (providing disposable masks, wipes) are not only implemented but are also made visible to visitors to build trust.

- For Museum Directors and Strategists: Understand the Value Equation of the Next Generation. Our model demonstrates that Generation Z is willing to embrace immersive technologies when the experiential payoff is high. This justifies strategic investment in high-quality VR as a core component of a museum’s engagement portfolio. Rather than viewing it as an ancillary cost, it should be seen as a high-value asset that can increase visitor dwell time, enhance educational outcomes, generate powerful word-of-mouth marketing, and ultimately solidify the institution’s relevance and cultural authority in the post-digital era [13].

- For Museum Directors and Strategists: Plan for Sustainability and Long-Term Maintenance. Beyond initial deployment, museums should view VR as a maintained service rather than a one-off exhibit. Stable long-term adoption requires planning for hardware replacement cycles, routine technical maintenance, staff facilitation and training, and periodic content updates. Proactive sustainability and maintenance planning can prevent experiential degradation (e.g., malfunctioning devices, outdated narratives) that would otherwise erode perceived enjoyment, usefulness, and continued engagement.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that provide fruitful opportunities for future research. First, the quantitative and qualitative samples were drawn exclusively from a Chinese context. Cultural values and institutional norms may moderate the acceptance mechanisms identified in our model. Future studies could validate the model in different regions and conduct cross-cultural comparisons to test its generalizability.

Second, this study examined Generation Z’s acceptance primarily at the stage of first-time or early VR use in museums. Prior research suggests that initial encounters in virtual museum settings often determine whether Gen Z users are willing to form subsequent and future adoption intentions [58]. Nevertheless, our cross-sectional design does not capture how perceptions and intentions evolve with repeated use, and thus cannot directly speak to long-term engagement or loyalty. Future research should employ longitudinal or diary-based approaches, or track repeat on-site VR usage, to examine continuance intention and the potential decay or reinforcement of perceived enjoyment and usefulness over time.

Third, the quantitative phase relied on a video stimulus rather than a hands-on VR interaction. Although this approach ensured standardization of exposure, it may have constrained participants’ sense of immersion and underestimated physical risks such as cybersickness, as well as situational concerns tied to sharing headsets on-site (e.g., hygiene cues). Field experiments or on-site data collection with fully interactive systems would strengthen ecological validity.

Fourth, our model focused on psychological and experiential determinants and did not incorporate several potentially relevant contextual variables, such as monetary cost, privacy concerns, or spatial design of VR areas. These factors emerged in the interviews as practical considerations for continued use and should be incorporated into extended models in future work.

Fifth, this study operationalized user experience mainly through Immersion and Content Quality, and did not quantify Authenticity as a standalone latent variable. We acknowledge that authenticity is a crucial factor in shaping visitor responses in heritage-oriented VR experiences [59]. Prior work also suggests that in VR settings, authenticity is often experienced as presence authenticity generated through immersive perception, rather than only the objective authenticity of exhibited information [60]. Our qualitative interviews echoed this tendency, as participants frequently evaluated the realness of the experience in terms of environmental fidelity and embodied presence. Future research can extend this framework to the broader spectrum of XR technologies. According to the virtuality continuum proposed by Milgram and Kishino [61], AR and MR anchor virtual content in the physical world and may strengthen situational authenticity relative to fully virtual VR environments. Comparative TAM-based studies across VR, AR, and MR modalities would be valuable for clarifying how different forms of technological mediation shape authenticity perception and subsequent adoption [62].

Sixth, our extended TAM focuses on visitor-level psychological determinants of early-stage acceptance and does not model institutional sustainability or long-term maintenance constraints. In practice, museums’ continued adoption of VR also depends on operational resources such as lifecycle cost, device durability, energy use, staffing and training capacity, sanitation/maintenance workload, and the ability to update or refresh digital content over time. Future research could integrate these organizational and sustainability variables into acceptance frameworks, or employ longitudinal field studies to examine how maintenance quality and sustainability planning shape continuance intention and repeat use.

Moreover, our qualitative findings highlight that Generation Z visitors differ markedly in their preferred social context for museum VR. Some participants anticipated shared VR visits with friends or family and felt that being “in the same situation together” would heighten enjoyment, echoing the notion of copresence as a subjective sense of mutual entrainment with others [63]. Others, however, explicitly preferred solitary engagement, expressing concern that visible avatars or conspicuous co-visitors would disrupt the narrative atmosphere and diminish immersion, a pattern consistent with museum learning research showing distinct benefits of solitary versus shared visits [64]. Future studies are encouraged to experimentally manipulate social context or compare individual- versus group-based VR, in order to test whether copresence moderates hedonic and immersive pathways in museum environments.

7. Conclusions

This study proposed and empirically validated an extended Technology Acceptance Model to explain Generation Z’s adoption of museum-based virtual reality. By integrating survey data from 566 respondents with insights from twenty in-depth interviews, we identified Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Enjoyment as the most influential direct drivers of intention, mediated by powerful experiential antecedents such as Immersion and Content Quality, as well as the crucial influence of Subjective Norm. Qualitative results further clarified how this demographic pragmatically weighs experiential rewards against physical risks like cybersickness and hygiene concerns. Taken together, these findings enrich HCI scholarship on immersive cultural technologies and offer museums a robust, empirically grounded framework for designing more meaningful and resonant visitor experiences.

Author Contributions

J.G. and W.Z. contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, J.G., W.Z. and F.W.; Data curation, J.G. and W.Z.; Formal analysis, J.G.; Funding acquisition, F.W.; Investigation, J.G.; Methodology, J.G., W.Z. and B.L.; Project administration, B.L.; Resources, F.W.; Software, Z.L.; Supervision, B.L., Z.L. and F.W.; Validation, J.G.; Visualization, J.G.; Writing—original draft, J.G. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China Major Project in Artistic Studies, grant number 22ZD18.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was reviewed by the Academic Ethics Committee of Jiangnan University, which granted an exemption from formal ethical approval (Approval No. JNU202506RB030). The committee determined that an exemption was warranted in accordance with national legislation (‘Ethical Review Measures for Human-Related Life Science and Medical Research’), as the study utilized fully anonymized data for research, posed no harm to subjects, and did not involve sensitive personal information or commercial interests.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical and privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the anonymous participants for their involvement in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| PU | Perceived Usefulness |

| PEOU | Perceived Ease of Use |

| PE | Perceived Enjoyment |

| SN | Subjective Norm |

| IMM | Immersion |

| CQ | Content Quality |

| C | Cybersickness |

| HC | Hygiene Concerns |

| IU | Intention to Use |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modeling |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

Appendix A. Interview Guide

The semi-structured interview guide used in the qualitative study is detailed in Table A1.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide used in the qualitative study.

Table A1.

Semi-structured interview guide used in the qualitative study.

| Dimension | Guiding Questions |

|---|---|

| Subjective Norm | Can you describe how recommendations from friends, family, or social media content have influenced your decision to try a museum VR experience? Do you recall a specific, influential example? |

| How much does seeing others use or talk about a VR exhibit online motivate you to try it yourself? | |

| Content Quality | Think about a VR experience you have had. How did the quality of the content—its accuracy, richness, or visual appeal—affect your overall impression and your willingness to use it again? |

| Immersion | Could you describe a moment when you felt truly “inside” a museum VR experience? What was that feeling like, and how did it influence your perception of the cultural heritage content? |

| Perceived Enjoyment | To what extent does the element of “fun” or “enjoyment” shape your desire to use or recommend a museum VR experience? |

| What specific design elements or interactions would make a museum VR experience more enjoyable and engaging for you? | |

| Perceived Usefulness | In what ways do you feel VR helps you understand exhibits or cultural stories better compared to traditional methods such as reading a label or viewing an object in a case? |

| Does this enhanced understanding make you more likely to seek out VR experiences in future museum visits? | |

| Perceived Ease of Use | Can you walk me through your experience of operating a museum VR system? Were there any moments of confusion or frustration? |

| How does the simplicity or complexity of the controls affect your overall enjoyment and intention to use the system? | |

| Cybersickness | Have you ever experienced physical discomfort such as dizziness or eye strain during a VR session? If so, could you describe it? |

| How did that physical feeling affect your willingness to continue that session or to try another VR experience in the future? | |

| Hygiene Concerns | What are your thoughts or concerns about using shared VR equipment in a public place such as a museum? |

| What specific situations or lack of cleanliness might make you hesitate to use it, and what measures would make you feel more comfortable? | |

| Intention to Use | Based on your experiences so far, what is your overall feeling about using VR in museums in the future? What makes you say that? |

| What are the most appealing aspects of a museum VR experience that would make you actively choose it again? |

References

- Cilliers, E.J. The challenge of teaching generation Z. PEOPLE Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 3, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Museum of China. Annual Data Report of the National Museum of China (2024). 2025. Available online: https://www.chnmuseum.cn/shxg/zlxz/pdfdown/202503/t20250320_271313_wap.shtml (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 2: Do they really think differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surugiu, C.; Grădinaru, C.; Surugiu, M.R. Drivers of VR Adoption by Generation Z: Education, Entertainment, and Perceived Marketing Impact. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, V.; Nisi, V. Lessons learned on engaging teenage visitors in museums with story-based and game-based strategies. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, M.K.; Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Malinverni, E.S.; Gain, J. A survey of augmented, virtual, and mixed reality for cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2018, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, K.H. Comparison of visitor experiences of virtual reality exhibitions by spatial environment. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2024, 181, 103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlauskaitė, R. Embodying ressentimentful victimhood: Virtual reality re-enactment of the Warsaw uprising in the Second World War Museum in Gdańsk. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2022, 28, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, F.T.; Ch’ng, E. Analysing narrative engagement with immersive environments: Designing audience-centric experiences for cultural heritage learning. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2021, 36, 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jung, T.H.; tom Dieck, M.C.; Chung, N. Experiencing immersive virtual reality in museums. Inf. Manag. 2020, 57, 103229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MuseumNext. How Can Museums See Beyond the Gimmicks in Virtual & Augmented Reality. 2021. Available online: https://www.museumnext.com/article/how-can-museums-see-beyond-the-gimmicks-in-virtual-augmented-reality/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Shehade, M.; Stylianou-Lambert, T. Virtual reality in museums: Exploring the experiences of museum professionals. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R. The End of the Beginning: Normativity in the Postdigital Museum. Mus. Worlds 2013, 1, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A. Generation Z: Technology and social interest. J. Individ. Psychol. 2015, 71, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, X. Transformation in the Digital Age: Factors Influencing Visitor Engagement in Virtual Museums. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025, 18, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Qin, J. From digital museuming to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramm, R.; Heinze, M.; Kühmstedt, P.; Christoph, A.; Heist, S.; Notni, G. Portable solution for high-resolution 3D and color texture on-site digitization of cultural heritage objects. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 53, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lv, C. Exploring user acceptance of online virtual reality exhibition technologies: A case study of Liangzhu Museum. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N. The Participatory Museum; Museum 2.0: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Giaccardi, E. Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. The Museum Experience Revisited; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammady, R.; Ma, M.; Strathearn, C. Ambient Information Visualisation and Visitors’ Technology Acceptance of Mixed Reality in Museums. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N.; Yaakub, A.R.; Othman, Z. Assessing user acceptance towards virtual museum: The case in Kedah State Museum, Malaysia. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sixth International Conference on Computer Graphics, Imaging and Visualization, Tianjin, China, 11–14 August 2009; pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Liang, H.; Ni, S. What drives users to adopt a digital museum? A case of virtual exhibition hall of National Costume Museum. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221082105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Shen, M.; Huang, W.; Yi, X.; Zhang, J. Differences in Heritage Tourism Experience between VR and AR: A Comparative Experimental Study Based on Presence and Authenticity. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2024, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.C.G.; Fabregat, R.; Carrillo-Ramos, A.; Jové, T. Motiv-ARCHE: Co-creation of augmented reality educational content to motivate cultural and natural heritage learning. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiouni, D.H.; Hackley, C. ’Generation Z’children’s adaptation to digital consumer culture: A critical literature review. J. Cust. Behav. 2014, 13, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratisto, E.H.; Thompson, N.; Potdar, V. Virtual Reality at a Prehistoric Museum: Exploring the Influence of System Quality and Personality on User Intentions. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmanović, E.; Rizvic, S.; Harvey, C.; Boskovic, D.; Hulusic, V.; Chahin, M.; Sljivo, S. Improving Accessibility to Intangible Cultural Heritage Preservation Using Virtual Reality. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and intrinsic motivation to use computers in the workplace. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaViola, J.J., Jr. A discussion of cybersickness in virtual environments. ACM Sigchi Bull. 2000, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebenitsch, L.; Owen, C. Review on cybersickness in applications and visual displays. Virtual Real. 2016, 20, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.F. A mixed methods approach to technology acceptance research. J. AIS 2011. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1937656 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- VIVE Arts; Emissive; Musée du Louvre. Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass. 2019. Available online: https://store.steampowered.com/app/1172310/Mona_Lisa_Beyond_The_Glass/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.J.; Pack, A.; Quaid, E.D. Understanding learners’ acceptance of high-immersion virtual reality systems: Insights from confirmatory and exploratory PLS-SEM analyses. Comput. Educ. 2021, 169, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disztinger, P.; Schlögl, S.; Groth, A. Technology acceptance of virtual reality for travel planning. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2017: Proceedings of the International Conference in Rome, Italy, 24–26 January 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 255–268. [Google Scholar]

- Calisir, F.; Altin Gumussoy, C.; Bayraktaroglu, A.E.; Karaali, D. Predicting the intention to use a web-based learning system: Perceived content quality, anxiety, perceived system quality, image, and the technology acceptance model. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2014, 24, 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, J.Y. The adoption of virtual reality devices: The technology acceptance model integrating enjoyment, social interaction, and strength of the social ties. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 39, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussell, S.G.; Truong, D. Accepting virtual reality for dynamic learning: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 5442–5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liang, H.N.; Yu, K.; Wen, S.; Baghaei, N.; Tu, H. Acceptance of virtual reality exergames among Chinese older adults. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 1134–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, P.J. Health and Safety Issues associated with Virtual Reality-A Review of Current Literature. Med. Eng. Comput. Sci. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Høeg, E.R.; Serafin, S.; Lange, B. Keep It Clean: The Current State of Hygiene and Disinfection Research and Practices for Immersive Virtual Reality Experiences. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Pieper, T.M.; Ringle, C.M. The use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in strategic management research: A review of past practices and recommendations for future applications. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 320–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Shin, Y.J. Why do people play social network games? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyal, A.H.; Rahman, M.N.A.; Rahim, M.M. Determinants of academic use of the Internet: A structural equation model. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2002, 21, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widaman, K.F.; Thompson, J.S. On specifying the null model for incremental fit indices in structural equation modeling. Psychol. Methods 2003, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ch’Ng, E.; Li, Y.; Cai, S.; Leow, F.T. The effects of VR environments on the acceptance, experience, and expectations of cultural heritage learning. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2020, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyman, M.; Bal, D.; Ozer, S. Extending the technology acceptance model to explain how perceived augmented reality affects consumers’ perceptions. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagnier, C.; Loup-Escande, E.; Lourdeaux, D.; Thouvenin, I.; Valléry, G. User acceptance of virtual reality: An extended technology acceptance model. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 993–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.C.; Hwang, M.Y.; Hsu, H.F.; Wong, W.T.; Chen, M.Y. Applying the technology acceptance model in a study of the factors affecting usage of the Taiwan digital archives system. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarac, T.; Ozretić Došen, Đ. Understanding virtual museum visits: Generation Z experiences. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2024, 39, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Nam, Y. Do Presence and Authenticity in VR Experience Enhance Visitor Satisfaction and Museum Re-Visitation Intentions? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttentag, D.A. Virtual reality: Applications and implications for tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. 1994, E77-D, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Pescarin, S.; Città, G.; Gentile, M.; Spotti, S. Authenticity in VR and XR Experiences: A Conceptual Framework for Digital Heritage. In Proceedings of the Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, Lecce, Italy, 4–6 September 2023; Bucciero, A., Fanini, B., Graf, H., Pescarin, S., Rizvic, S., Eds.; The Eurographics Association: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Castillo, C.; Hitlin, S. Copresence: Revisiting a Building Block for Social Interaction Theories. Sociol. Theory 2013, 31, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Solitary vs. Shared: Exploring the Social Dimension of Museum Learning. Curator Mus. J. 2005, 48, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).