1. Introduction

Unregulated and unsustainable diving practices pose a growing threat to one of the world’s most famous shipwrecks—the SS

Thistlegorm in the Red Sea. This World War II cargo vessel, now a major tourist attraction, attracts thousands of divers and generates an estimated €4 million for the local economy each year [

1] (p. 49). Yet the same popularity that fuels this economic benefit is accelerating the deterioration of the wreck and its cargo. To address this challenge, the Thistlegorm Project, a collaboration between Alexandria University and the University of Edinburgh, employed underwater photogrammetry to create the first comprehensive baseline survey of the site. This record not only supports long-term monitoring and preservation efforts but also serves as a pilot study in developing strategies for the public presentation of underwater cultural heritage.

Despite the SS Thistlegorm’s status as one of the world’s most intensively dived shipwrecks, there has been no quantitative, site-wide baseline against which the ongoing physical deterioration of the wreck could be measured. The absence of a baseline survey has made it impossible to assess change objectively and to distinguish between natural degradation and anthropogenic impact. The present study addresses this gap by discussing the results of repeated high-resolution photogrammetric surveys undertaken in 2017 and 2022 to document, quantify, and visualise structural and artefactual change on and around the wreck. In doing so, it describes a transferable approach for monitoring other metal wrecks of historic importance—many of which, like the Thistlegorm, fall outside existing legal protection frameworks yet face increasing pressures from dive tourism, looting, salvage, and climate change.

The baseline survey of the SS Thistlegorm was carried out in July 2017, using digital photogrammetry and 360 video approaches, and was then re-surveyed in May 2022 to record any changes and damage to the wreck in the intervening period, as well as to further record internal deck areas and to chart the extent and nature of the surrounding debris field. The Thistlegorm Project has created an extensive digital record of the site that can be compared with pre- and post-survey data to identify and chart changes to the wreck over time.

Located off the west coast of the Sinai Peninsula some 40 km from Sharm el-Sheikh (

Figure 1), the SS

Thistlegorm is the best-known and most popular wreck dive in the Red Sea [

1,

2,

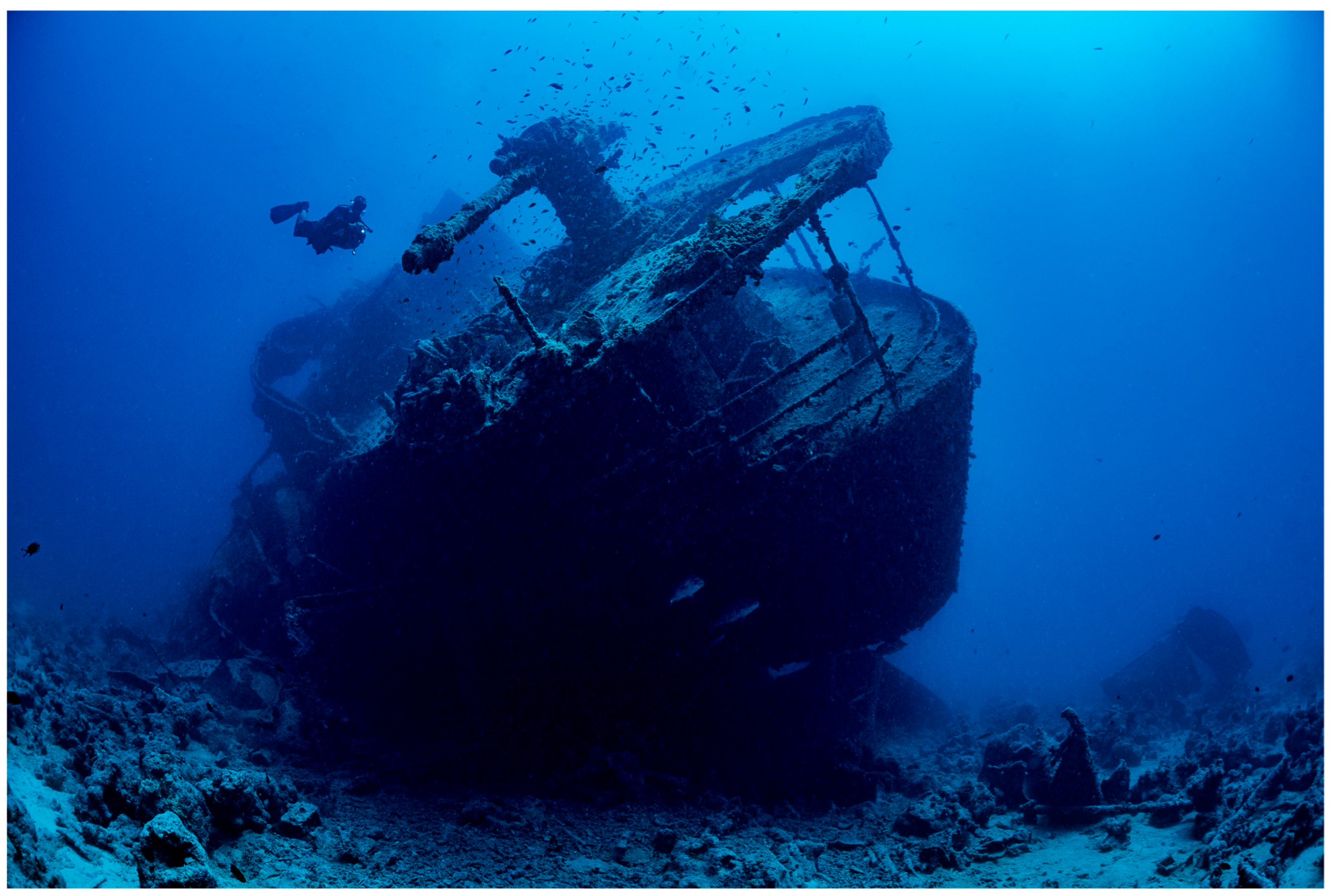

3]. The 125 m long British Merchant Navy armed freighter was sunk on the 6th October 1941 after being hit by two bombs from a German aircraft as she sat at anchor with a full cargo of lorries, trucks, motorbikes, railway tenders, Lee Enfield rifles, tracked armoured vehicles, motorbikes, aircraft spares, and a significant quantity of ammunition.

Sitting upright on a rocky seabed in 32 m of water, rising to a depth of 11.5 m at the peak of the wheelhouse, the wreck sits perfectly within the safe limits of recreational diving (

Figure 2). Since the development of Sharm el-Sheikh as a major dive tourism resort in the 1990s the wreck has become one of the most popular diving locations in the Red Sea and is widely regarded as one of the best wrecks to dive in the world [

4] (pp. 122–130).

The resulting increase in divers and boats to the wreck has resulted in damage to the remains that, as the numbers visiting the wreck continue to increase, is accelerating at an alarming pace. On average, at least five charter vessels leave from both Sharm-el-Sheikh and Hurghada every other day over the summer season to dive the wreck. Sometimes there can be more than fifteen dive boats moored on the wreck. These dive charter vessels, weighing over 40 tonnes each, attach their mooring lines directly to the wreck, wrapping them around upstanding features such as railings, guns, turrets, and deck winches. Strong currents and rough sea conditions create a lot of strain on these moorings and they can cause significant damage, ripping superstructure from the wreck and causing decks to collapse.

Along with mooring, the wreck is under continuous threat from looting. Every year parts of the wreck are looted—including everything from the removal of steering wheels from the many vehicles, crew personal effects, and clothing to the more organised salvage of entire motorcycles, non-ferrous metals, and other large items including the ship’s safe. Although Egypt signed the international UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage in 2017, which encourages states to better protect their submerged heritage, this legislation only applies to remains that are more than 100 years old. This means historically important remains from World War II like the SS Thistlegorm and indeed the vast majority of the metal wrecks in the Red Sea, in other words those that are popular dive sites, are currently afforded no protection by law (though in theory national legislation could be applied to sites less than 100 years old).

With no baseline survey of the remains, it has been impossible to quantify, measure, and track this destructive activity. Through comparative analysis of the 3D data gathered in 2017 and 2022 direct, quantified, and accurate measurement is now possible. Work has revealed that while generally structurally stable, the wreck and its contents are being directly impacted by diver activity, dive vessel mooring, and salvage activities. This paper summarises the changes identified and documents the latest results of the 2022 fieldwork.

2. History

The

Thistlegorm, constructed by J.L. Thompson and Sons shipyard, was launched into the River Wear in Sunderland on the 9th of April 1940 [

5]. Costing the Albyn Line owners a total of £115,000 GBP, the 4800 ton ship was taken into war service and was equipped with a pair of paravanes, used to detect and destroy tethered anti-shipping mines, at least two Lewis machine guns on the bridge, and two guns mounted at the stern. Known as a Defensively Equipped Merchant (DEM) ship, the

Thistlegorm was crewed by civilian merchant seamen, with Royal Navy sailors crewing the weapons.

The SS Thistlegorm made three successful journeys carrying goods from America, grain from Argentina, and rum and sugar from the West Indies. On the 2nd of June the Thistlegorm departed from Glasgow with a mixed cargo of vehicles, two Stanier 8F locomotives, general stores, aircraft spares, and ammunition destined for Alexandria, Egypt. With the Mediterranean predominantly controlled by Axis forces the Thistlegorm went via Cape Town, South Africa, before travelling up the east coast of Africa to Aden (Yemen). Joining a convoy escorted by HMS Carlisle the Thistlegorm headed up the Red Sea to the Straits of Gubal where the ship was given orders to wait at Anchorage F while a German mine blocking the Suez Canal could be located and destroyed.

On the night of the 5th of October 1941, a German Heinkel He 111 bomber from Kampfgeschwarder 26 Lowengeschwarder located the convoy and dropped two bombs on the SS Thistlegorm, striking Hold No. 4 and setting the ship on fire. The order was given to abandon ship with the crew taking to a lifeboat or jumping straight into the water.

Eventually the fire in Hold No. 4 triggered a secondary explosion in the cargo of ammunition, breaking the ship in two. The force of the explosion was considerable with heavy components such as the railway locomotive boilers (weighing 20~25 tonnes) between 60 m and 80 from the ship. At approximately 1:30 am on the morning of the 6th of October 1941 the SS Thistlegorm quickly sank in 30 m of water.

From a crew of 41 a total of 5 gunners and 4 sailors lost their lives, either during the initial attack, secondary explosion, or sinking. The survivors were picked up by HMS

Carlisle. For his bravery in rescuing an injured Royal Navy gunner crewmember Angus McLey would be awarded the George Medal in 1941 and the Lloyds War Medal in 1942 [

3] (p. 43).

2.1. Rediscovery and Popularisation of the Wreck

In 1955 the renowned marine explorer Jacques Cousteau reported he had discovered the wreck of the

Thistlegorm while looking for promising wrecks to dive in the Red Sea. Despite Cousteau’s claims it seems likely that the

Thistlegorm was never really ‘lost’—the Admiralty chart from 1948 records the wreck’s position accurately (27°48′52″ N, 33°55′16″ E) and it was well known locally as a shipping hazard given that, at the time, the mast was reportedly sticking out of the water. With that being said, the reporting of his discovery in the pages of

National Geographic magazine [

6], alongside the spectacular underwater footage featured in his 1956 documentary

The Silent World, brought the wreck to public attention for the first time. His descriptions of a pristine shipwreck replete with compass, porcelain, bottles, builders’ plate, and even the bell still in place, serve as a reminder as to what has been lost through removal of artefacts over the years. Cousteau himself raised both a BSA M20 motorcycle and a safe from the wreckage; the latter, when opened, contained nothing more than a drenched wallet with the captain’s ID, a one-pound note, two Canadian dollars, some port receipts, and a waterlogged roll of navigation charts [

7] (p. 89).

From the time of Cousteau’s visit and up until the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty was signed in 1979, the

Thistlegorm lay in troubled waters. A series of wars between Israel and its neighbours over the decades ensured that any diving activity on the wreck was likely to have been from the military. In fact, reports suggest that the mast was taken down in the late 1970s by divers from the occupying Israeli army [

1] (p. 163).

After Israel returned the Sinai to Egyptian control in 1982 some limited private diving activity took place out of Sharm el Sheikh, but the port town remained a difficult place to reach, and there was little dive tourism. This changed in the early 1990s as Sharm el-Sheikh and Hurghada began to develop as a popular diving resorts. As diving intensified and word spread, the wreck of the Thistlegorm began to become increasingly visited by divers and dive charter vessels. Following an assessment by the Egyptian authorities in 1992, the Thistlegorm was designated as an official location for recreational diving. This point marks the beginning of large-scale dive tourism on the wreck with charter vessels starting to visit the site on a daily basis.

2.2. Early Years—Losses from 1954 to 1999

The full extent of fittings and components that degraded or were removed since the wreck’s rediscovery is unknown, but what documented evidence there is points to considerable loss of material.

Cousteau’s footage and images present a shipwreck in almost pristine condition from which we can infer the loss of a range of material from the ship’s bell to the removal of a BSA M20 motorcycle. Based on the loading pattern and ease of access, the original location of the now missing BSA M20 can be confidently identified as the starboard side of Hold No. 2 upper deck. From the loading pattern every example of a Morris CS11/30 is loaded with five BSA M20, with one exception. A motorcycle-sized space on the rear of one CS11/30, which is very close to the hold access, suggests Cousteau lifted the motorcycle from here.

The fact that the ship’s mast now lies towards the original blast area rather than away from it supports the report that the mast was taken down in the 1970s by the Israeli military. Further post-wreck interference can be seen from the position of the bridge which seems to have taken a bashing over the years and has been pushed over from port to starboard. It is probable this was caused by a passing ship. The explosion in 1941 came from stern forward and therefore cannot therefore have been responsible.

John Kean [

1] (pp. 137–159) collected many local stories of divers looting a range of items from the wreck including ammunition, rifles, shells, medical supplies including morphine, the ship’s clock, the bridge telegraph, brass portholes, generators, utensils, and galley fittings. A seven-foot radio mast was also removed and was reportedly on display in a garden in Sharm el Sheikh. The list in

Table 1 of known and recorded objects removed is an attempt to summarise the loss.

2.3. 1992 BBC Site Visit and Documentary

In 1992, diver and BBC producer Caroline Hawkins visited the SS

Thistlegorm to conduct a series of photographic dives, capturing the condition of the wreck just before the onset of mass tourism and sport diving on the site. Hawkins would later direct the 1995 BBC documentary

The Last Journey of the SS

Thistlegorm, and her photographs and raw footage shot in 1994 for the film provide a critical baseline for assessing changes to the wreck over the past three decades [

8].

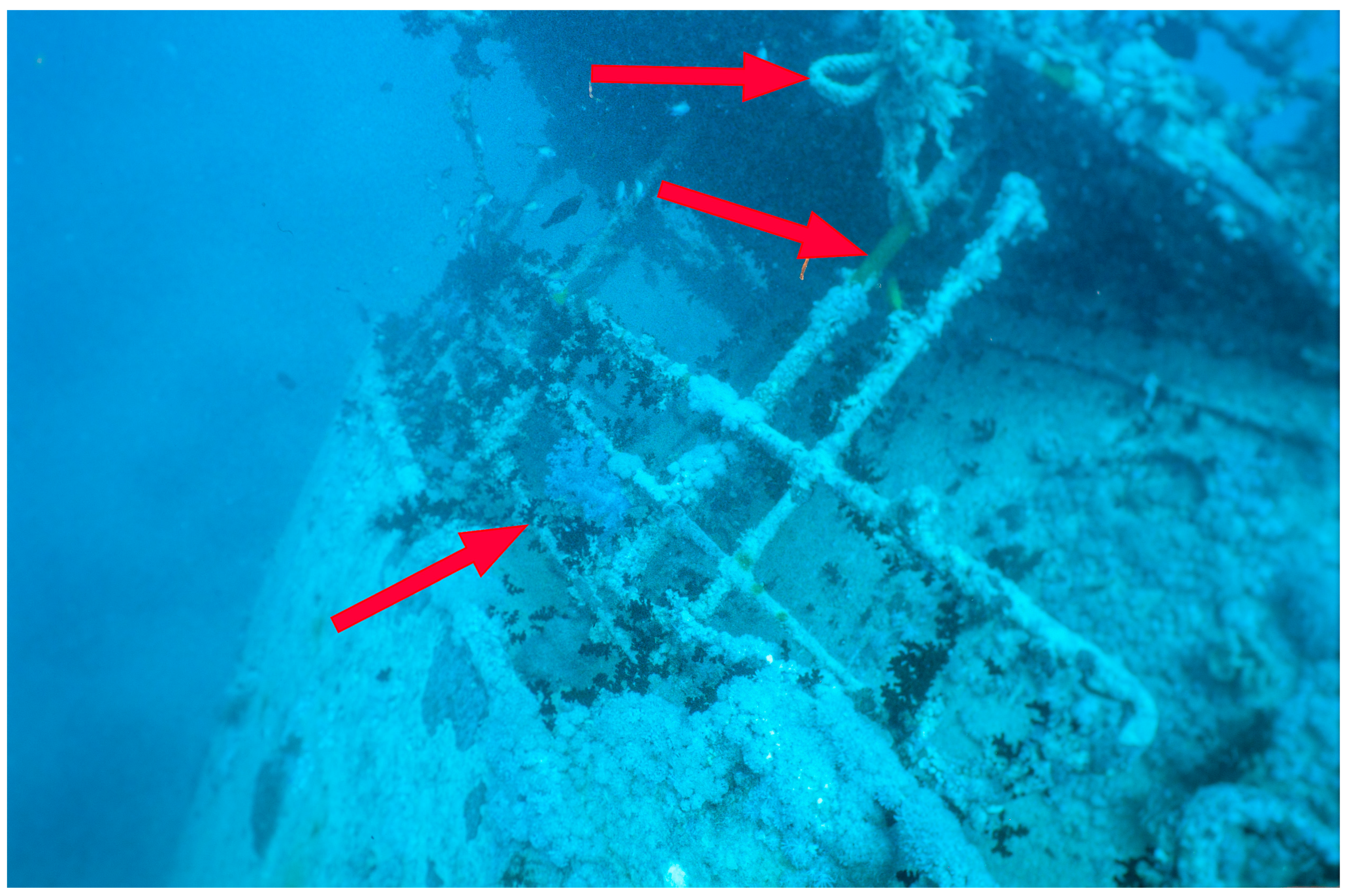

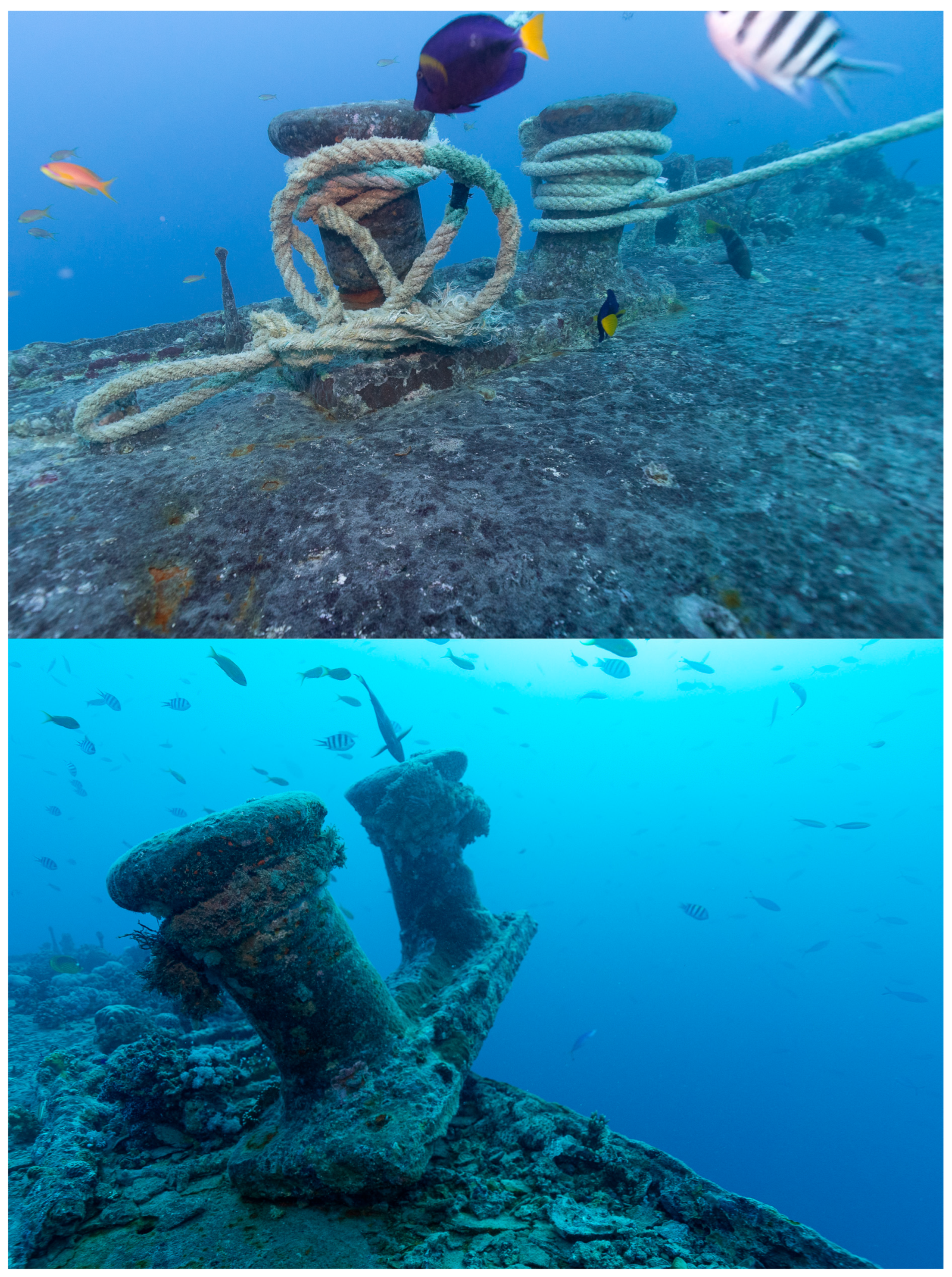

Even before Hawkins’ visit, dive vessels had been mooring directly onto the structure of the

Thistlegorm. Her images document mooring lines tied to the bow anchor winch and deck railings, with rope loops around vertical stanchions visibly scraping away protective coral and exposing fresh rust, indicating the early stages of corrosion accelerated by this practice (

Figure 3). The near-complete loss of railings along the ship’s bow—still intact in Hawkins’ photographic record—can be traced, at least in part, to historical mooring practices.

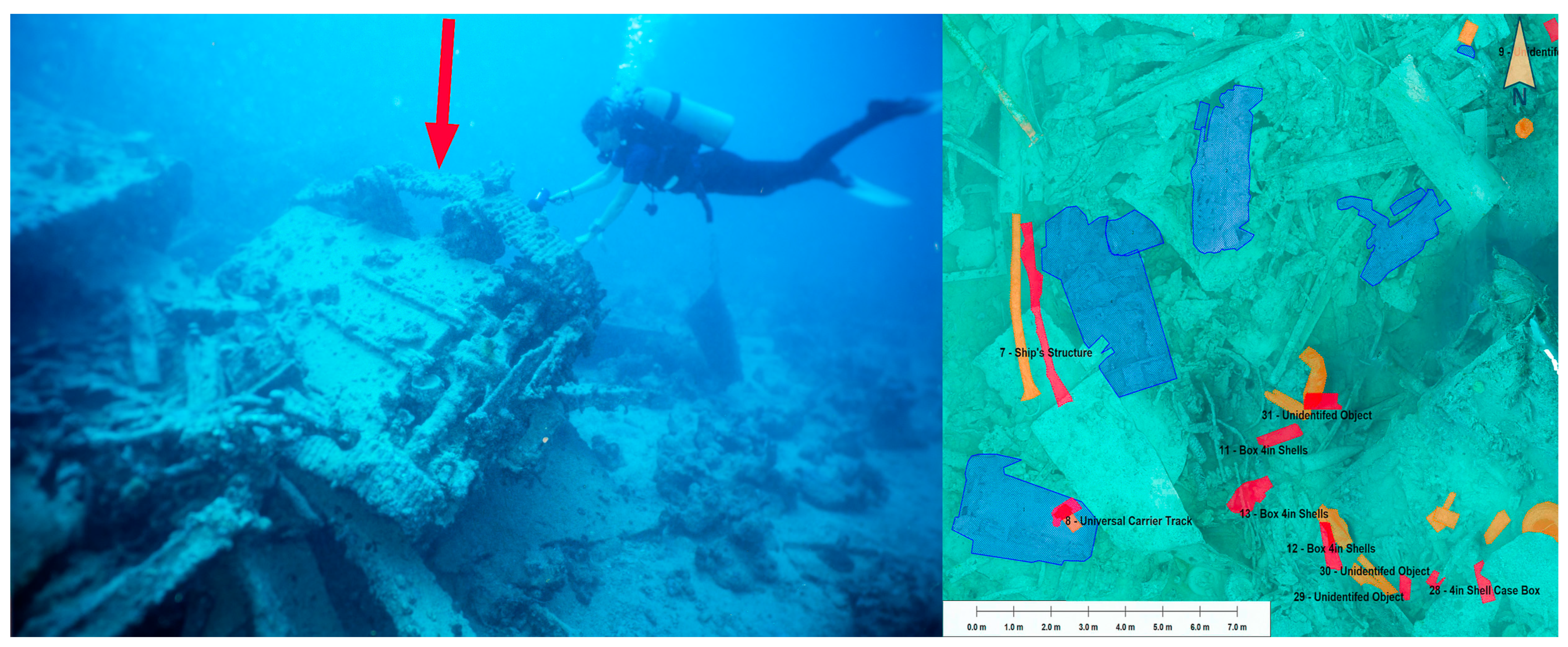

Hawkins’ photographs also capture various structural and artefactual elements that have since been lost or displaced. A deck-mounted ventilator behind the bridge on the starboard side, recorded in 1992, is now missing, while a similar ventilator found aft of the stern may have been moved or, more likely, displaced during the explosion in 1941 in Hold No. 4. Significant changes are observable in the remains of the Stanier 8F heavy freight locomotive located on the port side of the wreck. In 1992, a section of the locomotive’s mainframe was still attached to the smokebox; today, this piece lies separated on the seabed, confirming its origin as part of the locomotive’s structure and providing evidence of progressive fragmentation and loss of features, including potential removal of non-ferrous pipework. A large Brockhouse trailer, noted resting near Hold No. 5 in the 1992 images, was no longer on deck by 2017. The only similar trailer matching its design and suspension is now found approximately five metres from the wreck on the seabed, illustrating artefact displacement likely caused by environmental forces or human intervention. Hawkins’ images also record an inverted Universal Carrier with its left-hand track still in place within Hold No. 4. By 2017, this track was missing, with only a small section remaining beneath the vehicle. This fragment was later recorded in shifted positions during the 2017 and 2022 surveys, highlighting the ongoing movement of artefacts within the wreck (

Figure 4).

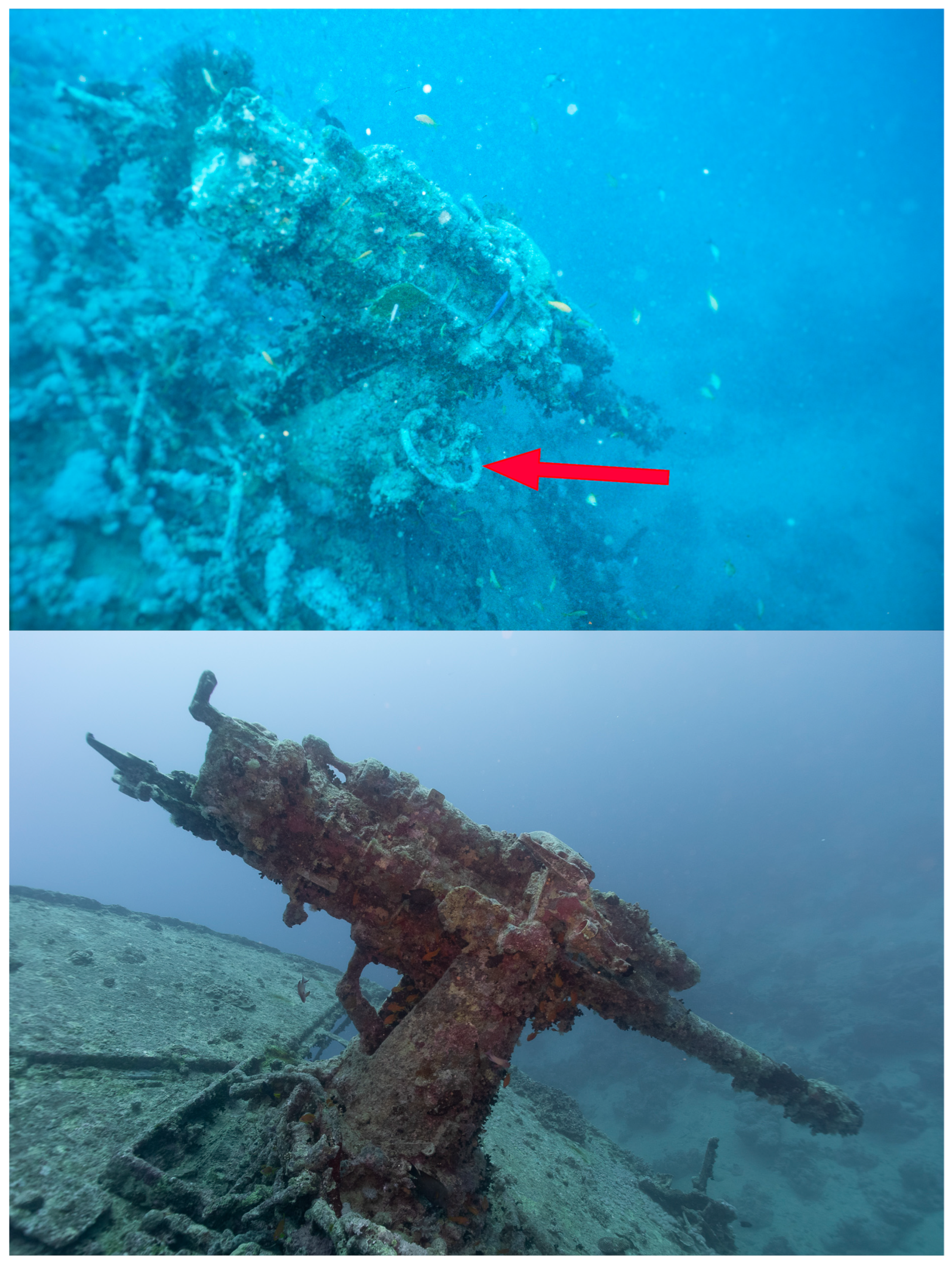

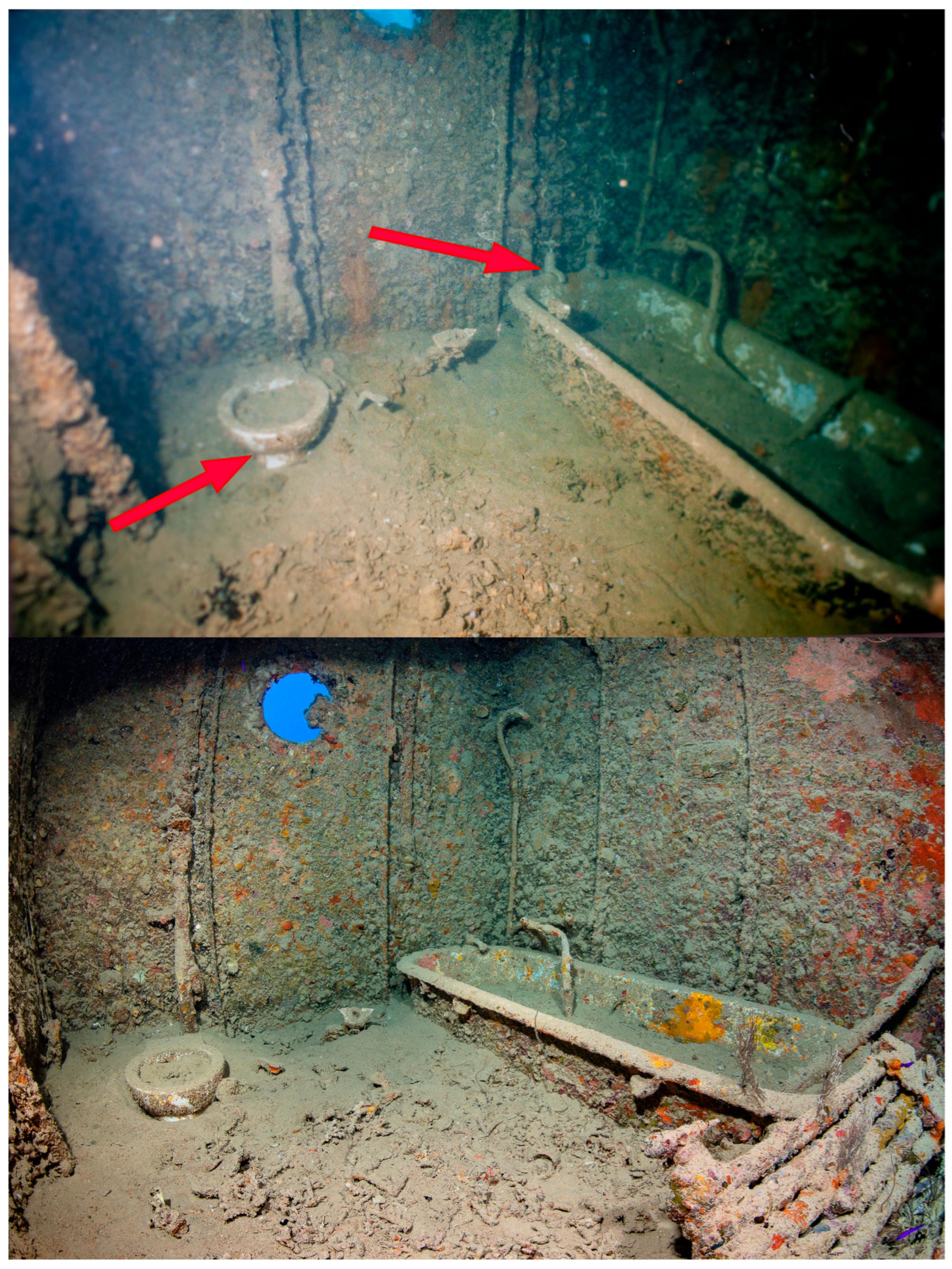

There is also evidence of the removal of smaller fixtures, presumably collected by divers as souvenirs. The traverse handwheel of the low-angle stern gun, present in Hawkins’ 1992 images, is now no longer in place and cannot be traced nearby (

Figure 5). Hawkins’ 1992 photograph of the captain’s bathroom shows the bathtub with both taps present; by 2018, one of the taps had been removed (

Figure 6).

Taken together, Caroline Hawkins’ 1992 photographs and 1994 film footage provide a vital baseline that reveals the steady attrition and displacement of artefacts, the progressive corrosion of structural elements exacerbated by mooring practices, and the subtle yet significant changes resulting from the intersection of natural and human impacts on the SS Thistlegorm over the past three decades.

2.4. Alex Mustard’s Photographic Archive (2005–Present)

Since 2005, underwater photographer Alex Mustard has systematically documented the SS Thistlegorm and its cargo, building an invaluable visual archive that has proven critical for monitoring changes to the wreck over time. His images provide clear evidence of deliberate artefact removal, particularly of non-ferrous objects associated with the vehicles in the cargo holds, and offer detailed insights into the condition of the wreck prior to the first photogrammetric survey in 2017.

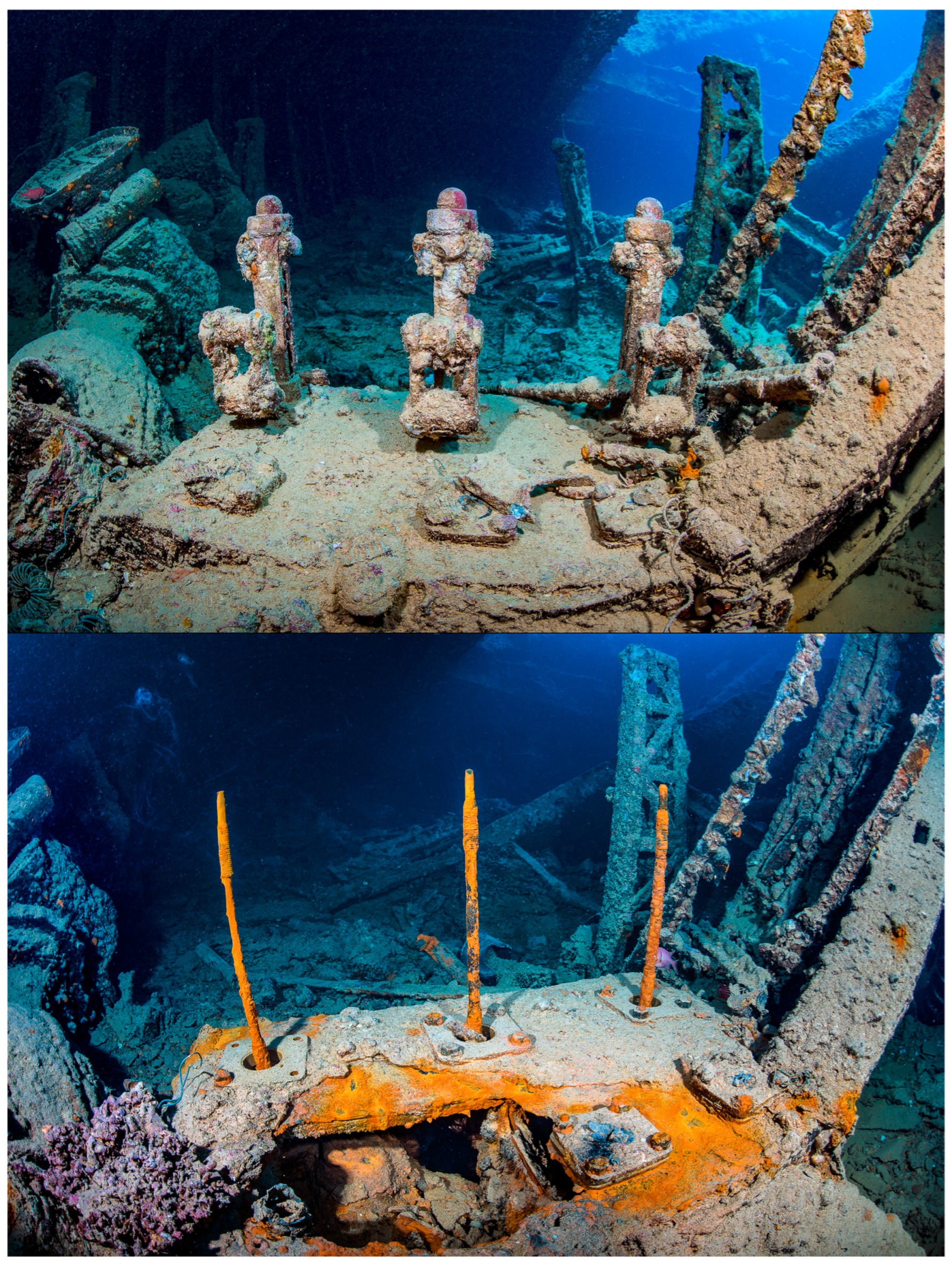

One area of ongoing concern captured in Mustard’s images is dive vessel mooring practice on the wreck. Comparisons between photographs taken in 1992 and those from 2013 reveal a significant increase in the number of mooring lines securing vessels to the structure, with images showing the use of steel hawsers, the anchor chain, and the deck winch as attachment points (

Figure 7). While deck mooring bollards likely cause less harm than other methods, the use of steel hawsers—often deployed to prolong the life of nylon ropes—has accelerated surface erosion on these fixtures. This is evident in images showing bollards with ropes looped around them, eventually leading to weld failures and displacement of the bollards themselves (

Figure 8).

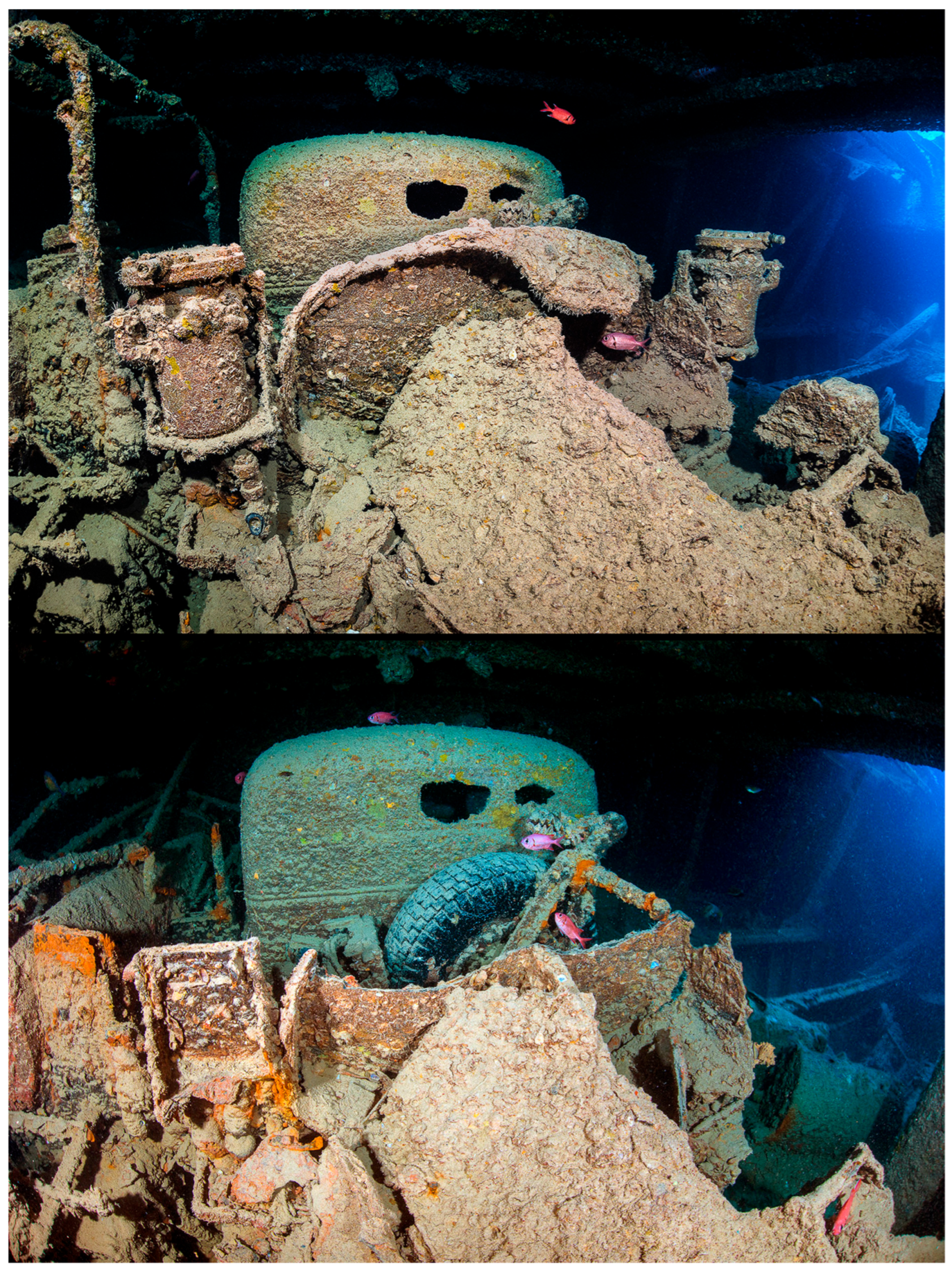

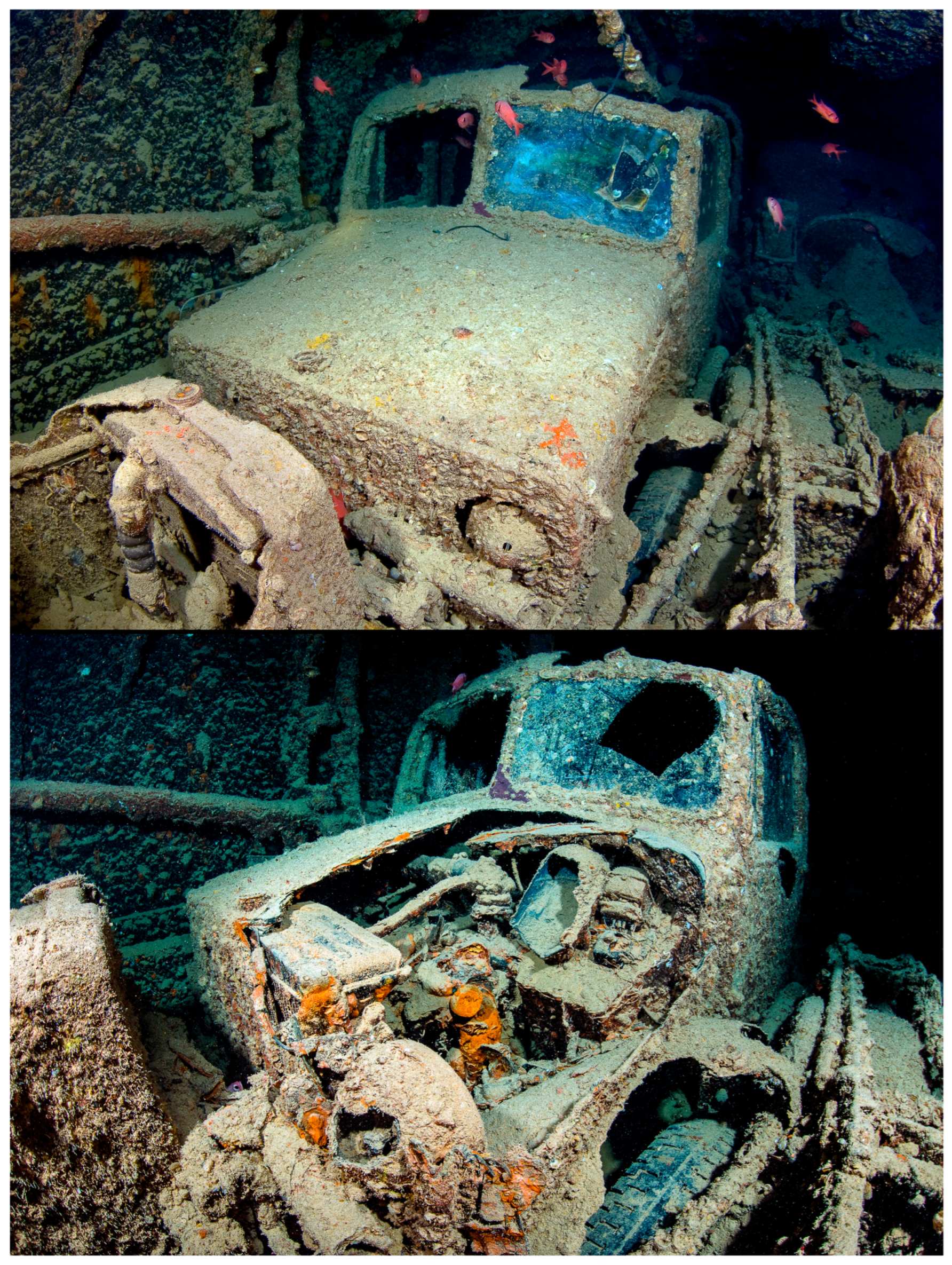

Beyond mooring-related impacts, Mustard’s photographs document a systematic pattern of artefact removal and damage within the wreck. Five examples of Bedford OCY tankers are found on the upper cargo deck [

3] (p. 110) and photographs reveal each have been subject to the recent targeted removal of non-ferrous metals (

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The removal of these non-ferrous filters was likely motivated by the scrap value of the materials, a pattern mirrored by the simultaneous removal of brass fuel valves from Albion AM463 refueler trucks located nearby (

Figure 11). As no known preserved examples of these refueler trucks exist elsewhere, the

Thistlegorm’s refuellers represent the last surviving examples of this type. The removal of these brass fittings in early 2015 underscores the vulnerability of the site to opportunistic artefact collection, erasing irreplaceable elements of the wreck’s historical fabric.

Mustard’s archive also captures the loss of objects with little or no scrap value, suggesting recreational divers may be taking items as souvenirs. For instance, the steering wheel of a Morris Commercial CS11/30 vehicle, documented in place in June 2008, was removed by June 2009 [

3] (p. 19). Given that the steering wheel, constructed from a steel frame covered in Bakelite, holds no significant monetary value, the most likely reason for removal is by recreational divers seeking a memento from their visit. It is unknown if this activity is carried out with the knowledge of dive guides and vessel operators.

3. Photogrammetric Survey in 2017 and 2022

The SS Thistlegorm was selected as a case study to document the wreck and its cargo, while also establishing a baseline survey to support future monitoring and management efforts for the site’s long-term preservation. Creating an accurate baseline survey is recognised as the essential first step in developing an effective management strategy for sites threatened by unregulated and unsustainable diving practices.

Photogrammetry provides an established, effective, and non-invasive 3D measuring technique for recording underwater cultural heritage [

9]. By deriving metric information from overlapping photographic imagery, it enables the generation of highly detailed, textured models that are both visually interpretable and metrically accurate [

10,

11,

12]. Compared with other recording methods such as manual tape measurements, or single or multibeam sonar, photogrammetry offers the following several advantages: it captures complex geometries at millimetre-scale resolution, requires minimal contact with the site, and can be repeated easily to monitor change over time. The resulting 3D datasets can be georeferenced, measured, and analysed quantitatively, allowing objective comparison between surveys as well as high-quality visual outputs for interpretation, conservation, and public dissemination.

More recently, multi-year photogrammetric surveys on shipwrecks have demonstrated how successive datasets can be used to monitor change through time, documenting both excavation impacts and environmental changes even where georeferencing or fixed control is limited [

13,

14]. However, the broader potential of photogrammetry as a systematic monitoring tool remains underexploited. One notable exception is the sustained programme across multiple WWII aircraft and shipwrecks in the Pacific, where baseline surveys in 2017 were repeated in 2023 to quantify natural and anthropogenic deterioration [

15]. Such longitudinal work highlights the feasibility of repeat 3D documentation for evidence-based monitoring of underwater cultural heritage.

In this study, monitoring simply refers to the systematic, repeat documentation of the physical condition of the wreck through high-resolution digital photogrammetric recording. The purpose of this visual monitoring is to detect, quantify, and interpret change—whether caused by natural processes such as corrosion, currents, or sediment movement, or by human activities including intensive diving, looting, and mooring practices. Using photogrammetric techniques, the Thistlegorm Project records a series of temporal “snapshots” that can be directly compared to measure structural deformation, artefact displacement, and surface wear over time. Continuous physical and chemical processes ensure that every survey captures only one stage of an ongoing cycle of deterioration. This evidence-based approach allows a broad assessment of the rate and nature of deterioration to be made and to identify particular areas of concern.

The equipment, techniques, and methods used to digitally record this large and complex wreck through photogrammetry, alongside the survey design and photogrammetric workflow followed, are discussed by the authors in detail in a previous paper [

16]. In this current paper the focus is on analysing the results of the photogrammetric surveys conducted in 2017 and 2022, with particular attention given to identifying and assessing damage to the wreck over time.

That said, the survey procedures followed are quickly summarised here for clarity. Complete coverage of the exterior of the wreck and the majority of the internal areas was achieved using overlapping image transects captured with single calibrated cameras in underwater housings equipped with dual strobes to ensure consistent illumination. Each survey was divided into smaller image “chunks” corresponding to major areas of the wreck (e.g., deck, cargo holds, stern, and debris field) to facilitate image alignment and processing. These chunks were scaled using pre-measured scale bars positioned throughout the site and by diver tape measurements taken between identifiable structural features. All scale markers were included in multiple overlapping images to maintain consistent scaling across chunks. The individual models were then aligned and merged within a local reference coordinate system established from stable structural features distributed across the wreck, providing a unified spatial framework for both datasets which could be consistently checked. Stable elements on the wreck such as bollards, hatch coamings, and deck fittings were selected as fixed reference points visible in both survey campaigns. Divers verified their relative positions by measuring inter-feature distances with calibrated fibreglass tapes to cross-check model scaling underwater. The stability of these features was further confirmed by comparing their relative geometry in the 2017 and 2022 datasets and against historical imagery. Alignment accuracy was validated through residual-error analysis during model registration, which consistently remained below 2 mm, confirming that the selected features had not shifted and could serve as fixed control points for change detection. Over 34,000 overlapping images were collected in 2017 and 2022, producing dense point clouds and textured meshes of the entire wreck, sections of the wreck or features of interest with an average ground-sampling distance of 1 mm and estimated positional accuracy of ±1.5 mm. The models were processed in Agisoft Metashape and analysed in GlobalMapper and CloudCompare for both qualitative visual assessment and quantitative distance and deformation measurements. These parameters ensured that the minimum detectable change was on the order of a few millimetres—sufficient to identify structural movement, artefact displacement, and surface degradation across the wreck.

The SS Thistlegorm was first captured photogrammetrically during the 2017 season, where twelve dives over 806 min (13 h and 43 min of in-water time) yielded 24,307 wide-angle images, generating 637 GB of data. Each image was tagged with location and description, with on-site processing conducted using Agisoft Photoscan Professional 1.3 to validate capture quality for 3D reconstruction and archive resilience. This initial survey established a baseline dataset for monitoring changes to the wreck and the surrounding seabed.

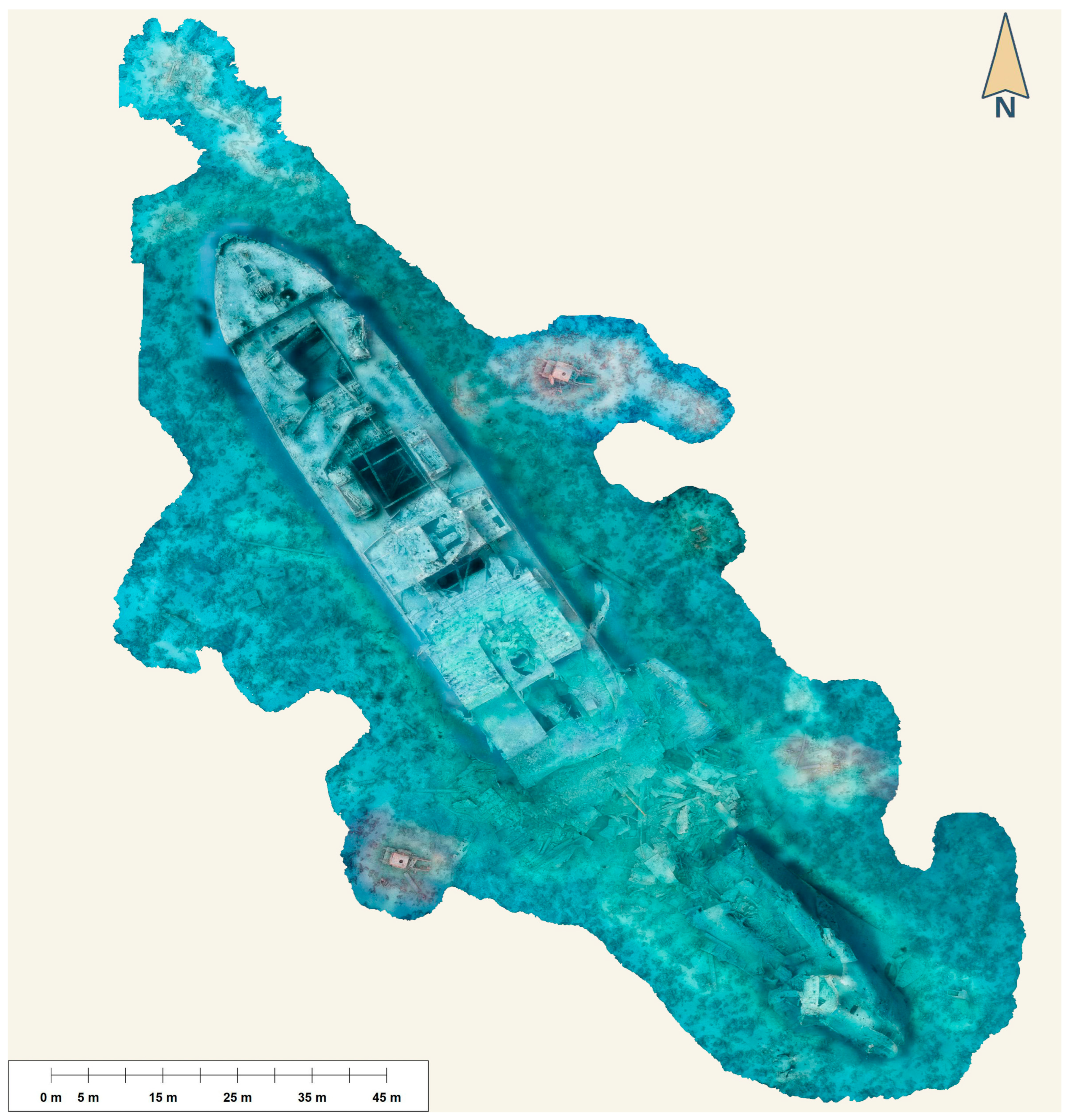

In 2022, a follow-up survey was conducted with seven dives over 357 min (5 h and 57 min of in-water time), capturing an additional 10,365 images and generating 246 GB of data, processed in Agisoft Metashape Professional 1.83. The 2022 season had two primary goals: to record changes to the ship’s structure, features, and artefacts since the 2017 baseline to assess the ongoing impacts of recreational diving, and to extend the survey area to map the debris field created by the secondary explosion that sank the ship, which scattered material, including two partial locomotives, across the seabed.

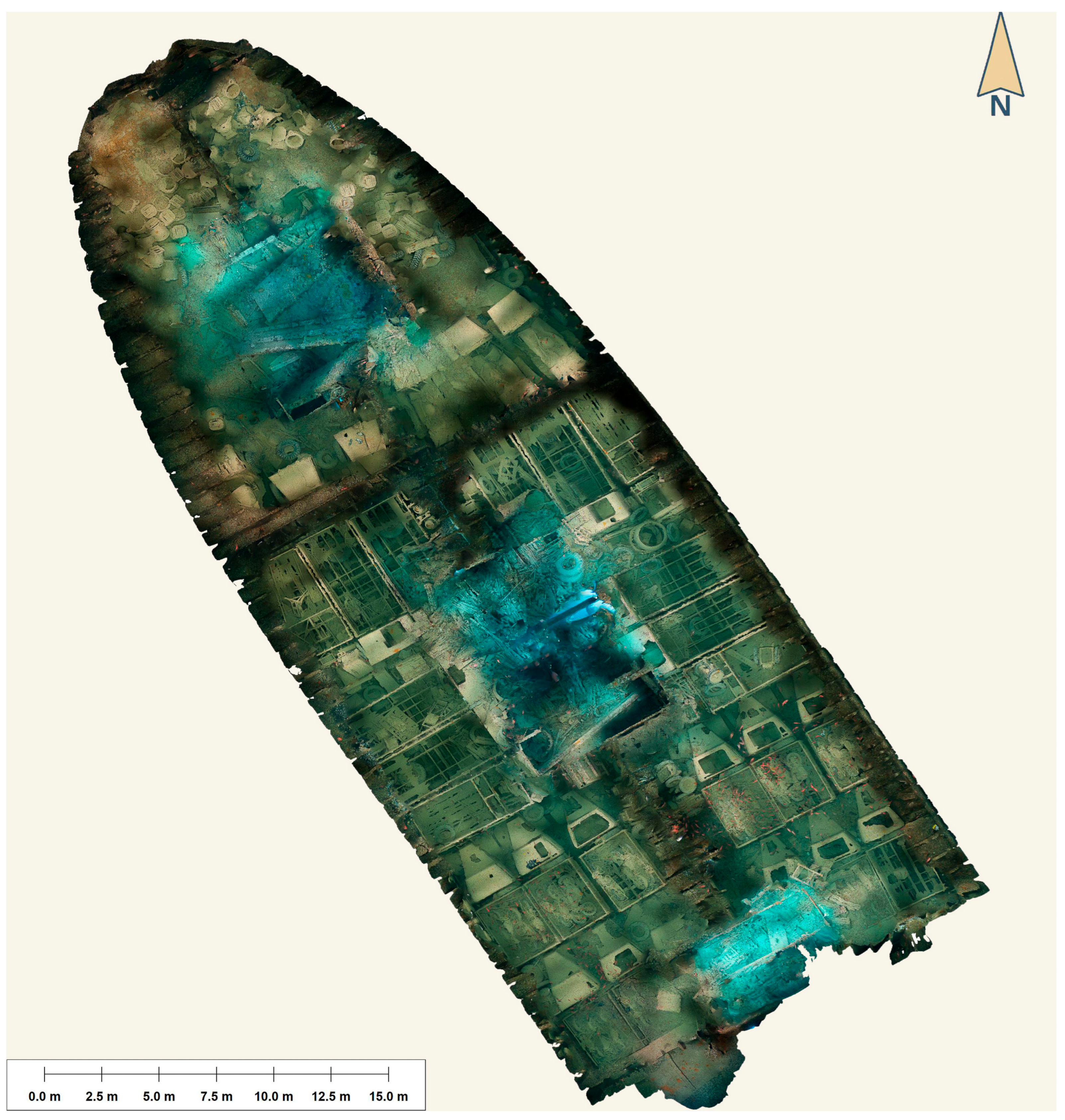

During the 2017 survey, a comprehensive record of the outer surfaces and features of the wreck and surrounding seabed was produced, including 3D models, orthophotos, and digital elevation models (DEMs). In addition, the accessible internal areas of the wreck were recorded including the forecastle room, upper and lower cargo decks of Hold Nos. 1 and 2, the saloon house, wheelhouse, and partial coverage of the engine room remains. In June 2018, Alex Mustard supplemented this dataset with images of the captain’s house, expanding the coverage of key internal areas.

The 2022 season focused on re-surveying known locations to record changes as well as filling in gaps from the previous survey and systematically mapping the wider debris field around the wreck. New areas surveyed included the port and starboard locomotive boilers blown off the decks by the original explosion as well as ship structures associated with those locomotives. The new survey included the port bow anchor and winch, aft mast remains, the stern anchor, and a locomotive wheel found near ammunition and ship structure fragments. Internally, the survey was expanded to include Hold No. 3 (upper and lower decks), the store room including the cold store, and the engineers’ accommodation on both port and starboard sides. The survey also examined sections of the central superstructure and debris piles in Hold Nos. 2, 4, and 5, providing detailed data on the distribution and condition of scattered artefacts. Additional material covering the Hold No. 2 lower cargo deck was provided by Holger Buss from a November 2022 dive, enabling comparative analysis with the 2017 baseline.

Taken together the surveys have achieved near-complete coverage of the external wreck structure and extensive coverage of internal decks and compartments. Areas with collapse or heavy siltation, such as parts of the engine room and lower holds, presented challenges for comprehensive recording and will remain priorities for targeted future survey efforts.

The 3D models and 2D orthomosaics produced during both survey seasons have proven invaluable for post-fieldwork research. The high-resolution orthomosaics, typically captured at 1 mm per pixel, have been critical in identifying objects, tracking their movement or removal, and assessing the condition of structural elements over time (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). The accuracy, scale, and, where possible, georeferencing of these orthomosaics cannot be overstated in their importance for monitoring, managing, and preserving the SS

Thistlegorm as a heritage site under increasing visitor pressure.

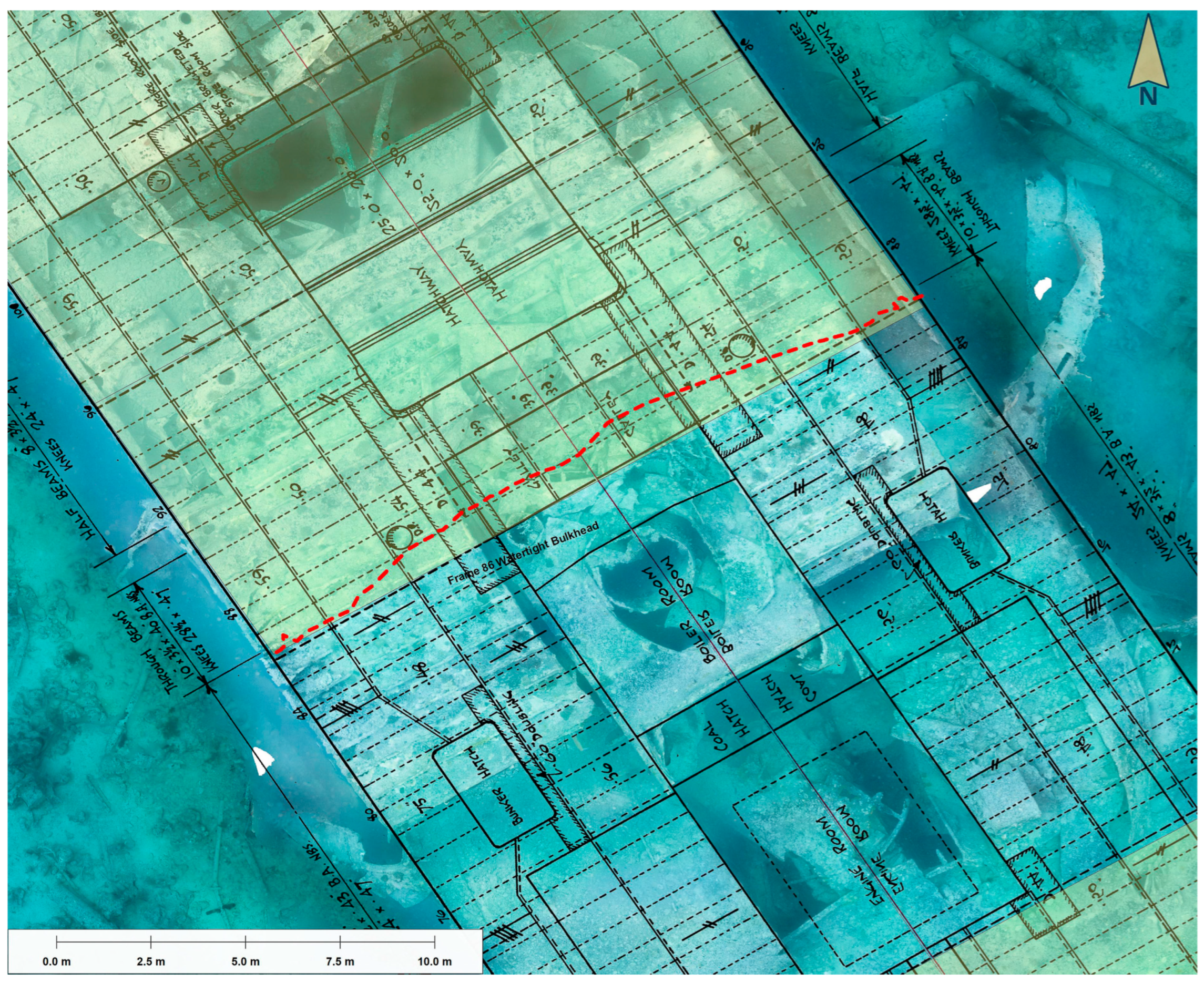

The original raster format orthomosaics, with scaling and georeference properties, have been used to create a base map for subsequent analysis and interpretation. Using Blue Marble Global Mapper Pro v23.1, the georeferenced data of the ship were added as individual layers. This included adding the raster-format builders’ plans main deck layout drawing which was manually rectified and aligned to the surviving structure of the vessel. This layer overlay reveals how the structure of the ship aft of the engine room has been substantially changed. The location of key features, such as hatchways, holds, and rooms, were extracted and drawn as vector-based shape file layers, simplifying the view of the overlay. The orthophotos of the main site, upper and lower cargo decks, have been used as a raster overlay in Global Mapper with vector overlays created to show physical location of identified objects.

Change detection between the 2017 and 2022 models combined automated and manual procedures. Once both datasets were co-registered within the same local reference system, a point-to-point distance analysis was conducted in CloudCompare to examine spatial differences on point clouds across the wreck surface. Any detected variations were then verified against the orthomosaics in Global Mapper and the high-resolution textured models to distinguish genuine structural or artefactual change from noise caused by lighting variation or biological growth. This integrated workflow allowed both quantitative measurement and qualitative interpretation of change, ensuring that detected differences represented real changes on the wreck.

3.1. Degradation and Damage: Internal Areas

The ship has a wide range of internal areas ranging from extensive cargo holds to living and working spaces used by the crew. Diver access to these areas commenced in 1954 with Cousteau’s visit and has increased with the rise in recreational diving on the site. The internal areas are popular, and the cargo loaded into the forward holds are very much part of the appeal to visiting divers. However, this popularity has contributed to ongoing damage within the wreck.

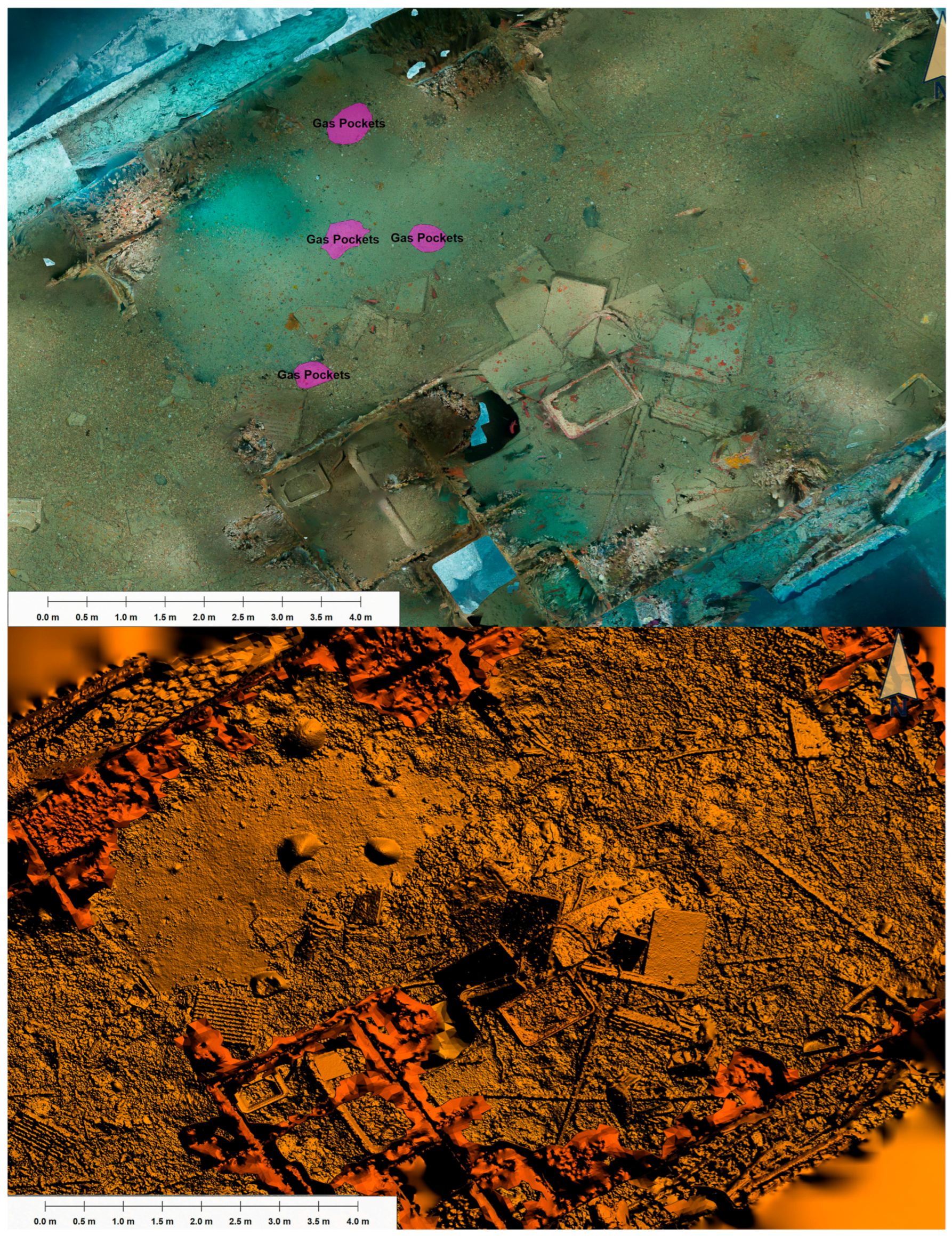

Open-circuit SCUBA equipment is typically used by divers visiting the wreck. Rebreathers are used within the recreational community, but the numbers are low when compared to open-circuit divers. There are no firm statistics to support the view, but casual observation of moored dive vessels and their divers indicate most dives are conducted with SCUBA equipment and result in exhaled gas being vented to the surrounding environment.

In open water the exhaled gas vents to atmosphere. Inside the wreck exhaled gas will remain trapped in any pocket that prevents direct ascent to the surface and whilst these pockets of gas are often out of sight (unless the diver looks up—an unnatural action when diving) the gas will be exerting a buoyant force against the pocket ceiling.

Evidence for this can be seen in The Saloon House where the floor carries evidence of damage by exhaled gas. The floor covering appears to be a type of linoleum, bonded directly to the steel deck. Several patches of floor covering have separated from the deck and an air pocket formed between deck and linoleum, creating a domed effect on an otherwise flat floor. It is believed a pocket of gas, collected on the ceiling of the upper cargo deck, has accelerated corrosion until a hole has formed and allowed gas to vent under the linoleum (

Figure 14).

The overall impact of exhaled gases and its impact on the steel structure of the wreck, especially when enriched with higher oxygen levels from Nitrox use, is unknown [

17]. Given the popularity of the cargo holds and the impracticality of enforcing a ban on diver penetration, managing this form of degradation remains a challenge for future conservation efforts (

Figure 15).

Fragile artefacts such as aircraft airframe components, motorcycles, lorries, and crates of rifles in Hold No. 2 attract significant diver traffic. Comparing the survey data from 2017 with the re-survey in 2022 revealed significant object movement, new graffiti, and, worse, artefact removal compared with the 2017 baseline. Items including tyres, airframe fragments, and rifle crates had clearly been moved, while the presence of graffiti on artefacts highlighted ongoing disturbance and a lack of respect for the wreck’s heritage value (

Figure 16).

Watertight bulkheads originally designed to preserve the ship’s integrity have also suffered extensive damage. Several were destroyed or damaged during the explosion that sank the ship, while others have been intentionally cut to facilitate diver passage and reducing decompression risks. This has led to significant structural weakening, with fresh oxidation visible on steel ribs indicating continued abrasion and erosion from diver contact (

Figure 17).

3.2. Degradation and Damage: External Areas

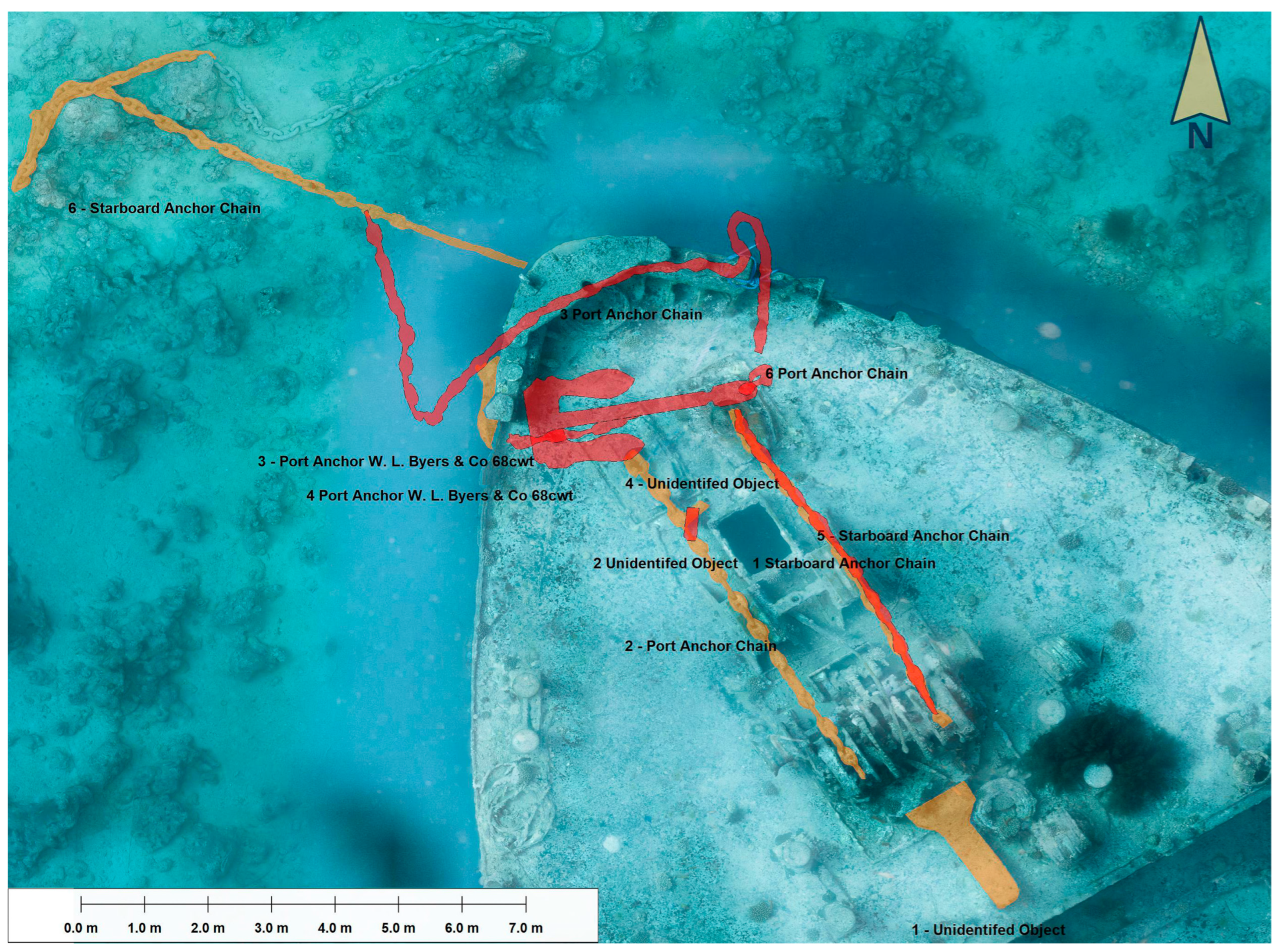

External areas of the wreck have also experienced significant degradation, particularly from mooring practices. The ship’s anchor chains have historically been used to secure dive vessels, resulting in visible thinning and corrosion of the chains and the displacement of the starboard chain from its guides. The impact of this practice was evident from the 2017 survey with both anchor chains showing evidence of ongoing wear through thinning of the individual links and corrosion build up. It could also be seen that the starboard anchor chain had been pulled from its rubbing strip guides. In 2019, the port anchor chain failed entirely, dropping the 3.5-tonne anchor and chain to the seabed and further displacing the starboard chain (

Figure 18).

On the main deck, the starboard machine gun mounting, originally positioned on the bridge, was recorded in 2017 before being found rotated by approximately 90 degrees in 2022. Given the weight of the mounting, this movement is likely due to entanglement with mooring lines rather than direct interference from divers, illustrating how even heavy structures are susceptible to unintentional displacement.

The starboard machine gun mounting, originally located on the bridge, was surveyed in position on the main deck in 2017 but was found rotated by approximately 90 degrees by 2022. The object’s mass makes individual diver disturbance unlikely and the movement is again likely due to poor mooring practices, with vessel lines snagging and shifting the structure during attachment or retrieval.

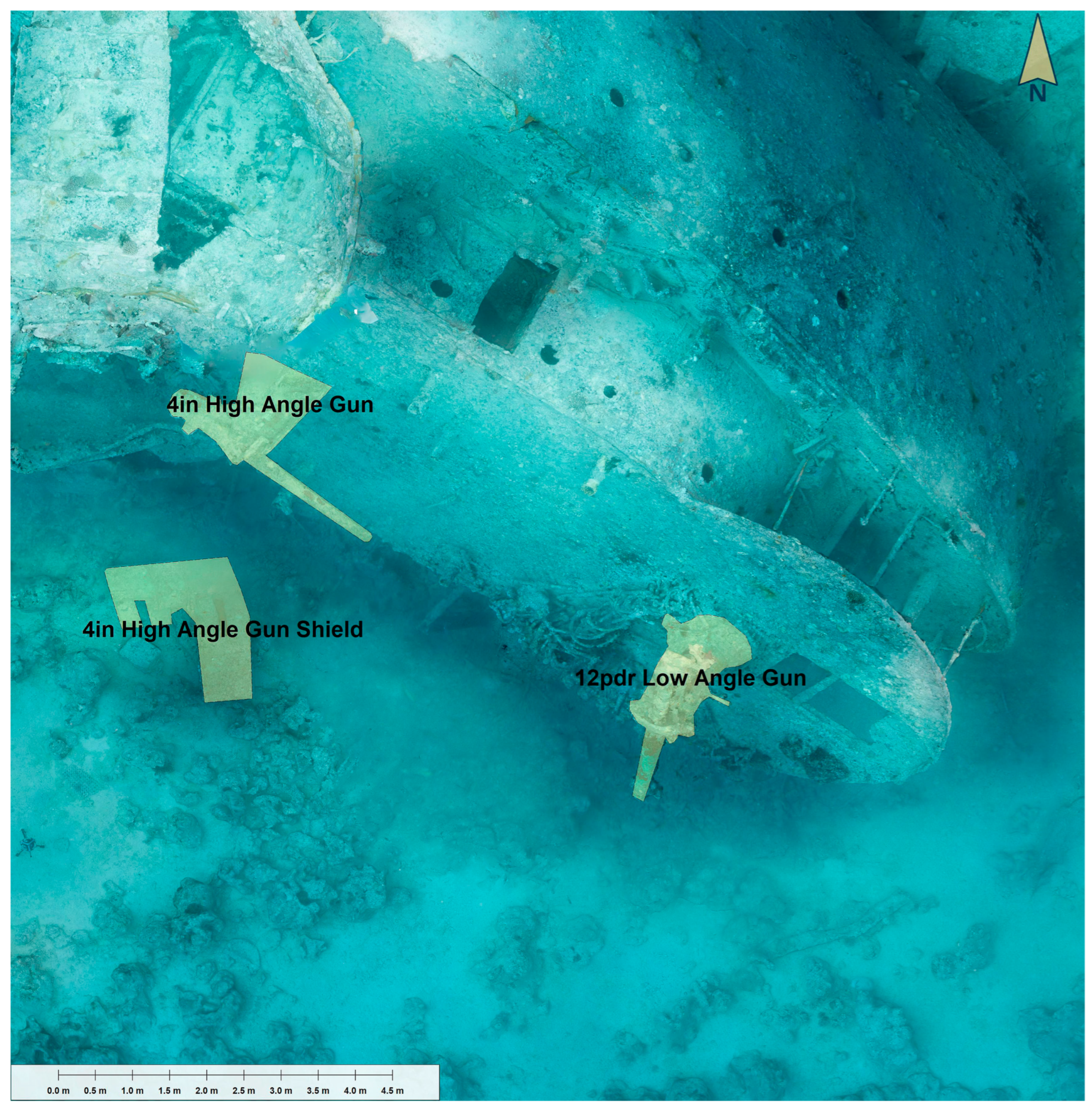

At the stern, the high-angle gun’s protective steel shield, which was still in place in photos from 2011 and before, was found on the seabed beneath the gun during the 2017 survey, reflecting the ongoing deterioration and dislodgement of defensive fixtures on the wreck (

Figure 19).

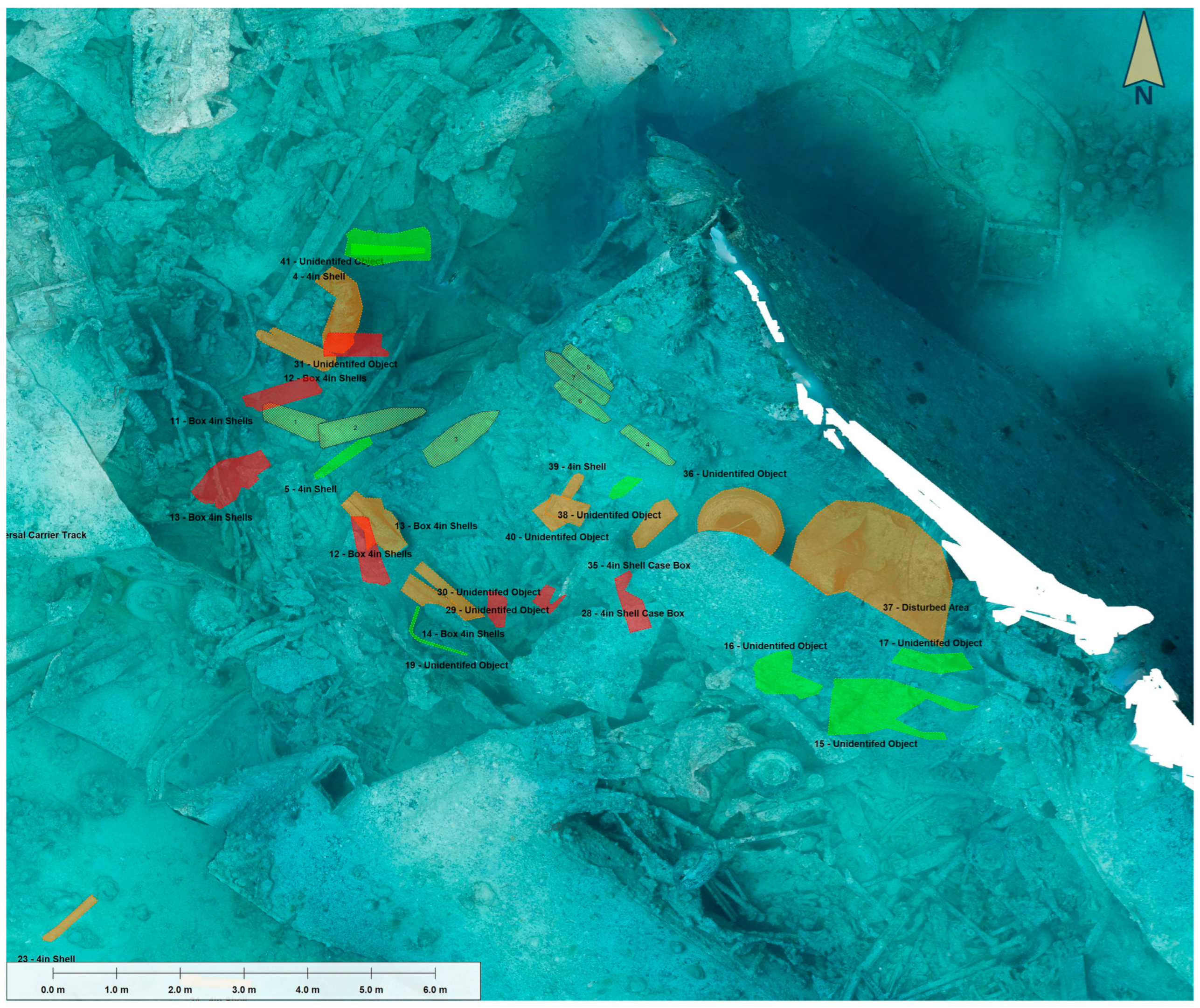

Although at first glance the debris field around Hold Nos. 4 and 5 appears stable, detailed analysis between the 2017 and 2022 of orthomosaics reveals significant changes, including the removal of artefacts, most notably non-ferrous items, and extensive evidence of the movement and redeposition of objects (

Figure 20). While some of these losses appear to be small-scale disturbances, potentially by divers seeking souvenirs or engaging in opportunistic recovery for scrap, other removals indicate more organised efforts. Notably, by 2022, a large drum of copper cable or wire had been removed from Hold No. 5—a heavy artefact measuring 1.12 m × 0.61 m—indicating a deliberate and planned salvage operation. The removal work disturbed the surrounding area with deck and hull plates being removed. Of particular concern is the movement of unexploded ordnance within the debris field, including Mk1 air-dropped depth charges containing around 113 kg of explosive material. These charges can become highly volatile, unstable and explode unexpectedly, having been responsible for the loss of at least one fishing vessel in UK waters [

18], and underscore the severe safety and heritage risks posed by unauthorised artefact disturbance at the site.

Nearby, a 2-tonne locomotive wheel and axle assembly located approximately 16 m from the main wreck was found to have rotated approximately 29 degrees between 2017 and 2022 (

Figure 21). The most plausible explanation for this movement is entanglement with mooring lines from dive vessels, illustrating how even heavy artefacts can be vulnerable to unintentional displacement.

Finally, two flanged sections of the propeller shaft can be found within the shattered remains of Hold No. 4, one exiting the engine room area and one passing through the remains of the watertight bulkhead between Hold Nos. 4 and 5. With the absence of deck mooring bollards in this part of the wreck these features are frequently used by dive boats as a mooring point. Originally used to transfer the power from steam engine to propeller, the shaft is manufactured from steel and is of exceptionally robust construction. That said, it can be seen that mooring rope movement is eroding the steel, with the red oxidation covering indicating the process is ongoing. The original engineering drawings, to which the prop shaft would have been manufactured, are held by the Lloyds Register Foundation archive (Drawing No 10422) and record the diameter of the shaft, ranging from a minimum of 1′ ½″ (317 mm) to a maximum of 1′ ¾″ (323.85 mm). Photogrammetric survey of the shaft revealed that it now measures 203 mm at the narrowest point just behind the coupling flange (

Figure 22). Without intervention, continued wear will lead to eventual failure of the shaft, risking vessel stability and diver safety during mooring operations. While the installation of sacrificial sleeves could mitigate damage, the use of the propeller shaft for mooring is not recommended due to these escalating risks.

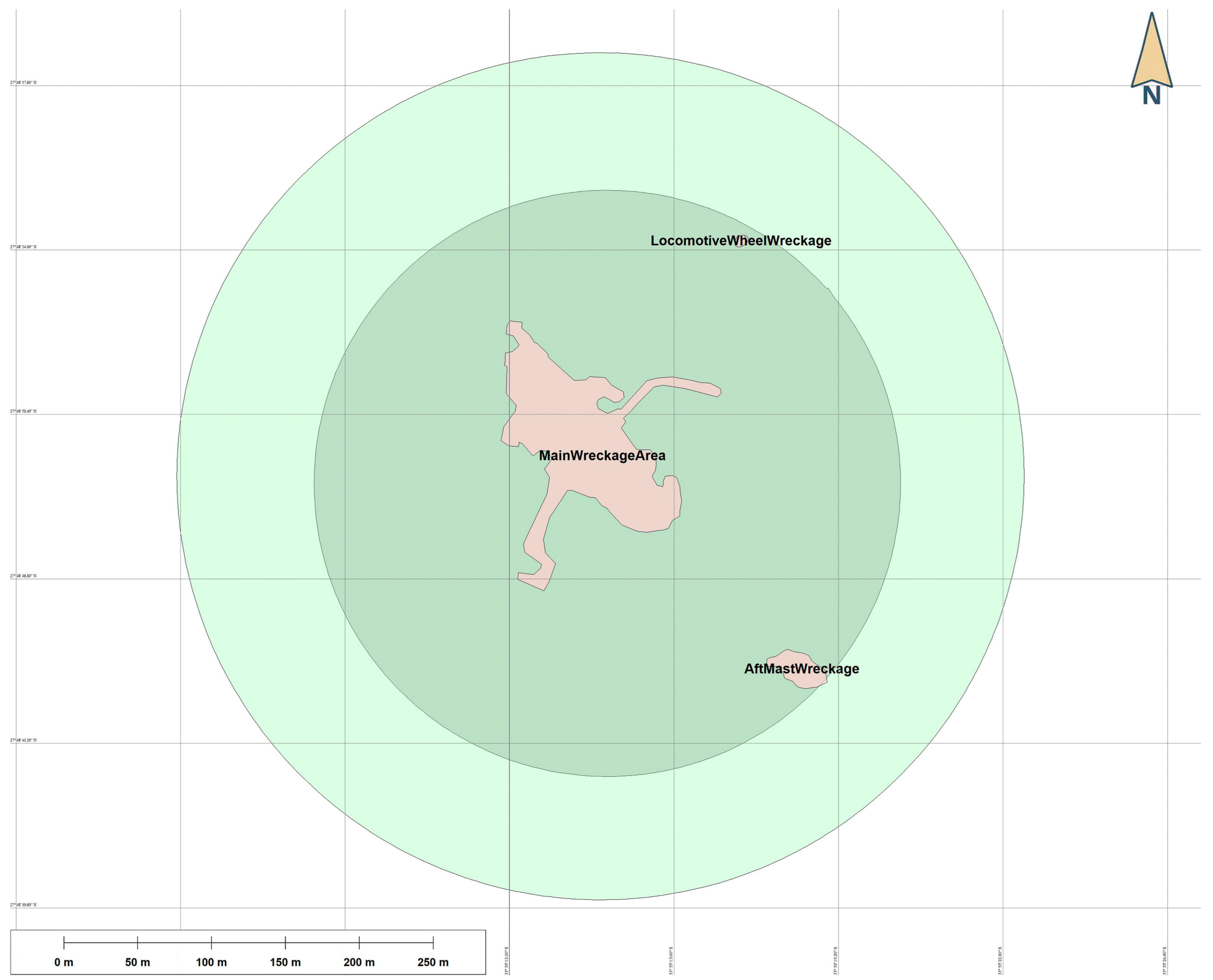

3.3. Extent of the Debris Field

A key objective of the 2022 fieldwork was to chart the full extent of the debris field created by the catastrophic secondary explosion in Hold No. 4. Prior to this survey, the debris field was estimated at 10.9 hectares, based on unverified positional data taken from the wrecksite.eu website. The new survey revealed substantial additional wreckage far beyond these limits, with significant components located as far as 200 m from the main wreck, including a one-tonne locomotive wheel lying 180 m away. These discoveries extend the known debris field to at least 21.9 hectares, doubling the recorded area of dispersed artefacts and wreckage (

Figure 23).

The wider debris field includes the remains of the aft mast and deck winch, displaced 159 m from their stowed positions, as well as a four-inch brass shell case found 180 m from the wreck. Structural plating, unidentified wreckage, and dispersed machinery parts are scattered across the seabed. This spatial pattern is consistent with contemporary accounts of the sinking. Reports agree that the SS

Thistlegorm was struck by an air-dropped bomb on Hold No. 4, igniting a fire that detonated the ammunition cargo. Dennis Gray, serving aboard the escort HMS

Carlisle, recalled in 1994 that “…it seemed to fold up and the stern went one way and the bow another as sinking ships often do…as if the back was broken and then it went down in a V-shape…it didn’t take long…” [

1] (p. 135). This report is supported by the composition of the wreckage on the seabed. The wreck’s orientation, with the bow to the north and stern to the south, matches the tidal stream at the time of loss.

By overlaying the 2017 orthomosaics onto the original builder’s plans within GIS, it is clear that the structure from the bow to midships remains largely aligned with the ship’s original form. However, aft of Hold No. 3, the effects of the secondary explosion are evident. The engine room and Holds Nos. 4 and 5 exhibit significant structural changes, with the forward section of Hold No. 5 peeled back and draped over the stern superstructure. The rear section of the wreck shifted approximately 7 m east during the sinking, while debris including the aft mast and deck winch has been found over 150 m away, demonstrating the force of the blast and subsequent distribution of wreckage across the seabed

Hold No. 1 also shows significant deformation, with partial collapse between the main and upper decks, crushed vehicle cargo, and a displaced port tank waggon with one wheel hanging over the lip of the hold. These features appear in 1992 photographs, suggesting they occurred during the sinking rather than through later deterioration. Comparative measurements between 2017 and 2022 models show minimal change, indicating that despite pressures from dive vessel mooring practices using bollards on the upper deck around Hold No. 1, the structural integrity of the main and upper decks in this area has been largely maintained.

Initially overlooked in 2017 due to its apparent lack of cargo, Hold No. 3 was fully surveyed in 2022. The hold is loaded with coal to an estimated depth of 3 m and is devoid of the more exotic cargo such as Norton motorbikes found in Hold No. 2. Despite this, the survey revealed further evidence of the impact of the secondary explosion and subsequent sinking. Close inspection of the 3D photogrammetric model of Hold No. 3 revealed the aft watertight bulkhead at frame 86 was deformed, and that the deformation was not uniform. The model was compared in Global mapper to the as-designed bulkhead position extracted from the ship builders’ plans. These plans, held by Tyne and Wear Archives and the Lloyds Register Foundation, clearly indicate the presence of a linear and uniform watertight bulkhead at frame 86. Analysis of 3D models and plans showed the bulkhead had shifted by up to 1.2 m from its original position, most likely due to the pressure wave from flooding during the sinking, rather than the secondary explosion itself (

Figure 24). This deformation can also be seen by the curvature observed in the vertical stiffening ribs within the hold (

Figure 25).

3.4. Evidence for the Force of the Explosion

The distribution, displacement, and deformation of heavy components provide direct evidence of the extraordinary forces involved in the Hold No. 4 detonation. The secondary explosion not only damaged the ship but also dispersed cargo across the seabed. Eyewitness Dennis Gray stated “…there seemed to be a second explosion and still looking in that direction [towards the ship] we were amazed to see what turned out to be a railway engine and it was red hot with sparks flying from it…” [

1] (p. 144).

The presence of two Stanier 8F heavy freight locomotives, carried as deck cargo, has long been known, with smoke boxes and parts of the main frame from each locomotive located on the port and starboard sides of the wreck [

3] (p. 194). These artefacts, as impressive as they are, represent just 25~30% of the complete locomotive [

3] (p. 201) and the 2022 fieldwork set out to locate missing components in an effort to begin to establish the extent of the debris field around the wreck.

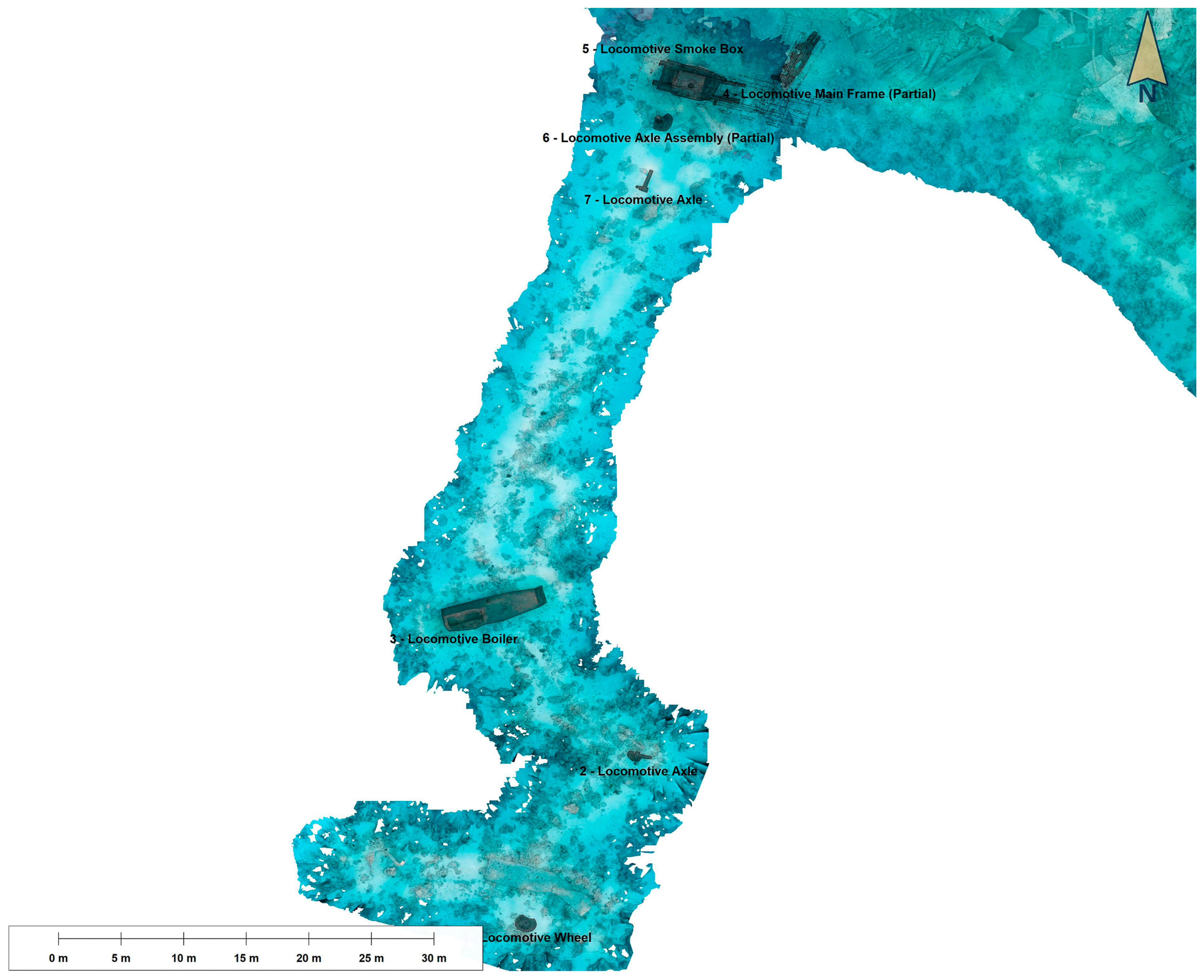

The port locomotive boiler had been photographed on the seabed off the wreck by Alex Mustard in 2018 [

3] (p. 195) but the exact location and its relationship to the main wreck site was unknown. Using a reel and line secured to the port smoke box a search of the seabed to the southeast was conducted and located the damaged boiler lying inverted on the seabed. The guideline served as a reference for subsequent transits swum to create a broad swathe of photogrammetry to reference the boiler back to the main site. Between the smoke box and boiler, an axle and single leaf spring assembly, with wheels removed, is located approx. 27 m from its as-stowed location (

Figure 26). The boiler (item 3) lies 59 m from its stowed location alongside Hold No. 4 and the structure itself records damage likely inflicted by the primary or secondary explosion. The estimated mass of this assembly is 22~24 tonnes. The search was extended beyond the boiler in a southeast direction locating a second axle assembly (Item 2) and a single locomotive wheel (Item 1) close to what is either ship deck or hull plate. The wheel is estimated to weigh approx. 1 tonne and lies 80 m from its as-stowed location. The presence of two axles minus their wheels is noteworthy. The Stanier 8F Association notes that a variable force of between 150 and 192 tons would be required to press the wheels from their axles [

19]. This force is likely to have been applied by the secondary explosion.

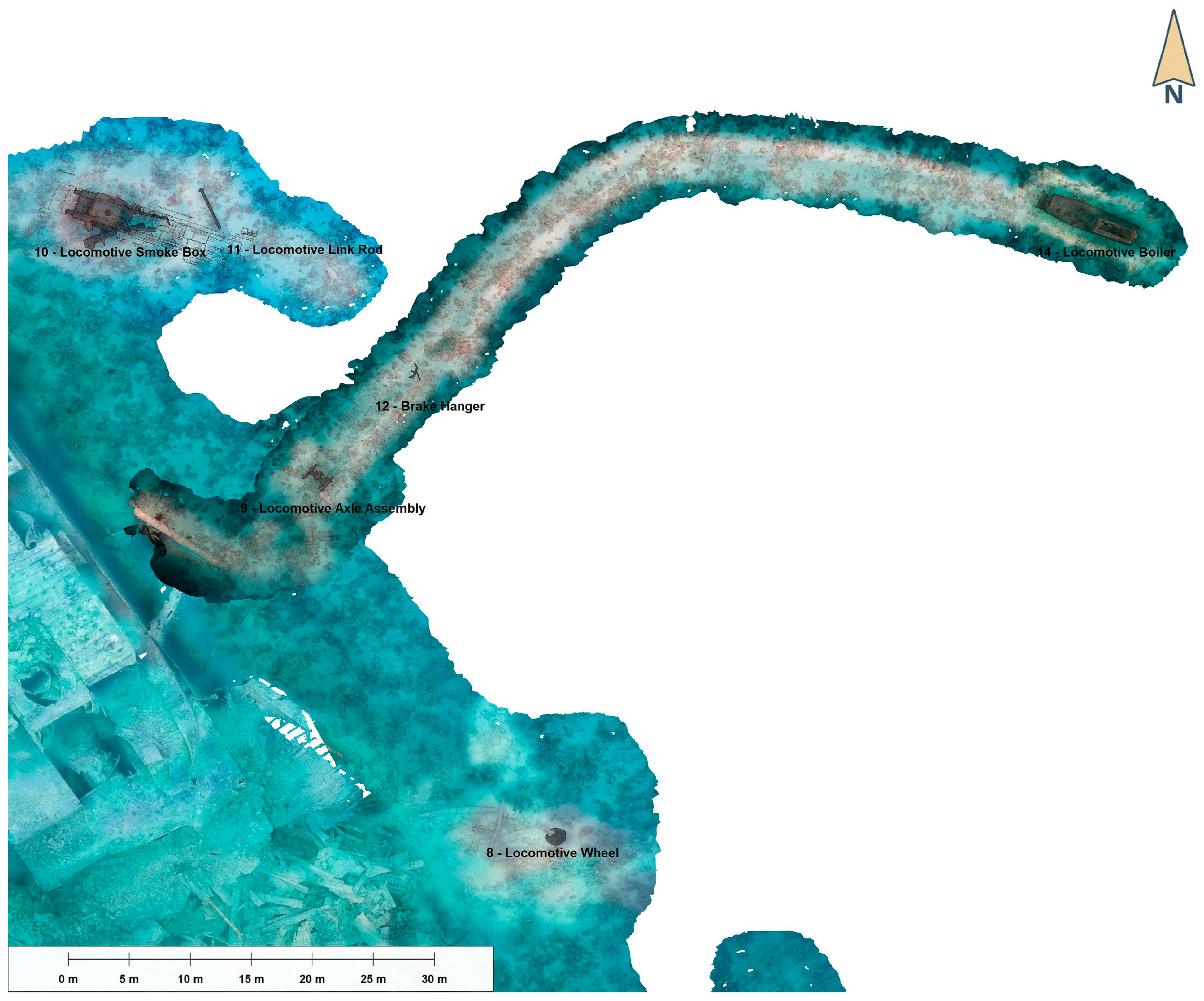

The presence of a locomotive boiler on the starboard side was also inferred from the existence of a smoke box, tender, driving and link rods, and associated wheels but the location of the locomotive itself was unknown. Using two reels of 50 m line starting from the starboard locomotive wheels, circular searches were conducted resulting in the discovery of the boiler 75–80 m from its stowed position, lying inverted and heavily deformed, with a distinctive concave damage pattern on the firebox wall (

Figure 27). The estimated mass of this assembly is 22~24 tonnes.

Both boilers displayed evidence of significant deformation underscoring the immense forces involved during the secondary explosion. Comparison between the original engineering plans and the surveyed remains reveal the extent and forces involved in the damage (see

Table 2 and

Table 3). The port side boiler is deformed and punctured (a hole has been punched through 25/32″ thickness of steel boiler plate) and overall diameter measurements exceed the original specifications by over 30 cm in places. A similar pattern was observed on the starboard side, where the boiler is inverted and heavily deformed, with a distinctive concave damage pattern on the firebox wall. Notably, a brake hanger identified within the debris confirms the extent of dispersal and offers insight into the locomotive’s disintegration during the blast.

Further evidence of the blast’s reach came from the discovery of a locomotive wheel and a four-inch brass shell case approximately 180 m from the wreck, as well as the aft mast and deck winch displaced 159 m from their original positions. Eyewitness Dennis Gray recalled a “second explosion” and seeing a railway engine “red hot with sparks flying from it” [

1] (p. 114) —an observation consistent with the physical evidence of heavy locomotive components hurled far from the ship.

Taken together, the expanded debris field and the severe deformation of massive steel components demonstrate that the Hold No. 4 secondary explosion generated forces sufficient to both disintegrate and scatter major sections of the vessel and its cargo over an area now known to be at least 21.9 hectares.

4. Conclusions

Since its rediscovery, the SS Thistlegorm has faced continuous human interference, with deliberate removal of artefacts evident even in Cousteau’s early documentation. At the time, the historical significance of the wreck was not fully appreciated, and the risks of interference were minimal due to the limited number of divers. However, as awareness of the wreck grew and recreational diving expanded, so too did the scale of disturbance. Non-ferrous materials and parts of the ship’s equipment have been systematically removed, resulting in a loss of context and provenance, whether these items were scrapped or ended up in private collections.

Mooring practices have further contributed to the wreck’s gradual degradation. With no viable alternatives, dive vessels continue to secure lines directly to the ship, causing structural wear. Although some mitigation measures, such as shifting from steel hawsers to nylon ropes, have reduced immediate damage, fresh oxidation, and dimensional changes to key structures like the propeller shaft indicate ongoing strain on the wreck.

The systematic application of comparative photogrammetry has proven invaluable in documenting these changes. It has allowed for precise recording of subtle disturbances, such as the movement of small artefacts, the appearance of graffiti, and even the repositioning of larger structures once assumed to be immovable, including the starboard locomotive wheel assembly and ‘fixed’ objects such as the deck bollards. These observations challenge assumptions about the stability of heavy objects on the seabed and underscore the vulnerability of the site to both intentional removal and unintentional disturbance.

The 2022 fieldwork expanded our understanding of the debris field, revealing a significantly larger distribution area than previously estimated, with artefacts found up to 200 metres from the main wreck site. These findings provide critical insights into the dynamics of the wreck’s sinking and the forces unleashed during the secondary explosion, offering valuable data for interpreting the final moments of the ship. It is clear that any future legal protection for the Thistlegorm must extend beyond the immediate wreck to include the wider seabed, ensuring comprehensive conservation of both the wreck and its scattered artefacts.

The Thistlegorm will remain a popular dive site for the foreseeable future, presenting an opportunity to harness citizen science to monitor and document the site. The increasing availability of affordable action cameras means many divers unintentionally collect valuable visual data during their visits, contributing to a growing archive of images that can be used to track changes over time. The significance of these contributions is evident from the impact of Cousteau’s film and Caroline Hawkins’ 1992 photographs, which continue to inform our understanding of the wreck’s condition and history. Although the quality of these citizen-collected datasets may vary, their integration with established photogrammetric baselines can yield insights far beyond what formal fieldwork alone can achieve. Encouraging divers to submit imagery and 3D models can enhance monitoring efforts, foster stewardship, and raise awareness of the wreck’s fragility. This, in turn, may help modify diver behaviour, reducing future damage and artefact removal while building a collaborative approach to heritage preservation.

As underwater cultural heritage sites worldwide face increasing pressures from tourism, environmental change, and unauthorised interference, the systematic monitoring and management approaches trialled on the SS Thistlegorm offer a scalable model for balancing access, preservation, and research. As one of the most visited wrecks in the Red Sea, its management provides insights for preserving underwater heritage in areas where tourism pressures are rising. Establishing the Thistlegorm as a protected heritage site, with legal status extending to its wider debris field, would safeguard its cultural value while setting a precedent for integrated heritage and marine resource management in Egypt. There is a clear need for collaborative frameworks involving Egyptian authorities, dive operators, and heritage professionals to implement alternative mooring solutions that minimise structural damage, develop site monitoring protocols, and align conservation goals with the local economy that benefits from wreck tourism.

The next phase of the project will prioritise establishing a structured re-survey schedule to monitor structural integrity and artefact displacement, expanding debris field mapping to capture the full extent of dispersed material, and systematically integrating diver-submitted photogrammetry data into the monitoring programme. Addressing the risks posed by unexploded ordnance will require community education and practical risk mitigation measures to ensure diver safety while reducing disturbance to hazardous artefacts. While the project has demonstrated the power of high-resolution monitoring, limitations remain, including the challenges of environmental variability, the absence of a cargo manifest, and data gaps in historical records. These constraints underscore the need for adaptive methodologies as the project continues. It is also important to acknowledge the potential impacts of climate change—such as increased storm intensity and warming sea temperatures—on the wreck’s stability, which alongside growing dive tourism pressures, reinforce the urgency of effective, proactive management of this irreplaceable underwater cultural heritage site.

The results presented here provide a clear, site-wide picture of the physical changes affecting the

Thistlegorm, but they also highlight the need to integrate this visual evidence with finer-scale analyses to fully understand the processes driving deterioration. While photogrammetric monitoring provides a powerful means of visualising and quantifying structural change across an entire wreck, it inevitably captures only the broader physical manifestations of deterioration. The technique records deformation, displacement, and surface loss but cannot in itself reveal the underlying chemical and electrochemical processes driving corrosion. In contrast, micro-scale in situ corrosion studies, such as those undertaken on the World War II wrecks in Chuuk Lagoon [

20,

21], generate detailed data on material stability, decay mechanisms, and environmental parameters such as pH and corrosion potential. Integrating such micro-level analyses with site-wide photogrammetric surveys would yield a far more comprehensive understanding of how deterioration progresses through both structural and material pathways. Developing management plans for the

Thistlegorm and similar wrecks would therefore benefit greatly from coupling repeat 3D documentation with targeted corrosion monitoring, ensuring that conservation measures are informed by both spatially extensive and chemically diagnostic evidence [

15] (p. 690).

The findings of this study underscore the urgent need for proactive management of twentieth-century wrecks that fall outside formal protection frameworks such as the UNESCO 2001 Convention’s 100-year threshold [

22]. The

Thistlegorm illustrates how historically and culturally significant sites can undergo rapid physical transformation long before they qualify for international protection. National legislation does, however, have the ability to extend heritage status to such wrecks based on their documented historical and educational value rather than their age alone. Integrating scientific monitoring—at both macro- and micro scales—into management planning would provide the robust evidence base needed to justify and guide such interventions. In this sense, the

Thistlegorm serves as both a warning and a model: a reminder of the vulnerability of modern underwater heritage, and a demonstration of how systematic digital documentation can inform more responsive and forward-thinking conservation policy.

Through systematic photogrammetric monitoring, careful analysis of the debris field, and the active involvement of the diving community, we can continue to document, understand, and protect the wreck for future generations, ensuring that its story as a wartime casualty and a cultural heritage site is preserved beneath the waters of the Red Sea.