Abstract

Increasing urbanisation and the intensification of environmental and climate challenges require a review of governance models and tools supporting urban and territorial planning. The Twin Transition concept (green and digital) requires the integration of advanced monitoring and simulation systems. In this context, Digital Twins (DTs) have evolved from static virtual replicas to dynamic urban intelligence systems. Thanks to the integration of IoT sensors and artificial intelligence algorithms, DT enables the transition from a descriptive to a prescriptive approach, supporting climate uncertainty management and real-time territorial governance. The ability to integrate multi-source data and provide high-resolution site-specific representations makes these tools strategic for planning, resource management, and the assessment of urban and peri-urban resilience. The contribution comparatively analyses different digital twin frameworks, with particular attention to their applicability in highly complex environmental contexts, such as the city of Taranto. As a Site of National Interest, Taranto requires models capable of integrating industrial pollutant monitoring with urban regeneration and biodiversity protection strategies. The study assesses the potential of DT as predictive models to support governance for more sustainable, adaptive, and resilient cities.

1. Introduction

The urbanisation process is now a fairly well-established phenomenon globally, posing significant environmental, social, and economic challenges. According to the United Nations, 55% of the world’s population currently lives in urban areas, a figure that is set to rise to around 68% by 2050 [1]. This phenomenon has extremely negative consequences for the environment and society, as urban expansion is often associated with land consumption, soil sealing, loss of biodiversity, reduction in agricultural and forest areas, and increased levels of air pollution and emissions that significantly impact the climate [2] and phenomena linked to human behaviour that degrade and pollute the soil and water environments, such as littering [3].

These effects are part of an already complex picture, in which cities are facing the consequences of climate change (e.g., heat waves, extreme weather events, floods, and droughts) that amplify pre-existing social and economic vulnerabilities [4]. In peri-urban contexts, characterised by rapid land use change and increasing pressure on natural resources, these challenges are even more acute, generating conflicts between development needs, environmental protection, and the well-being of local communities. Faced with these challenges, traditional forms of urban governance often show structural limitations that slow down decision-making and planning processes, as a result of poor integration between sectors and institutional levels [5,6]. This has given rise to the need for innovative, rapid, and effective tools capable of providing a dynamic and detailed picture of the conditions of cities and peri-urban areas.

The European policies have outlined the ‘Twin Transition” concept, a systemic approach that sees digital transformation as an essential driver for achieving climate neutrality. The official document systematically defines the link between digitalisation and climate neutrality, emphasising how digital technologies are critical enabling factors for achieving the objectives of the Green Deal [7]. The Joint Research Centre (the Commission’s science and knowledge service) has also moved in this direction, publishing a report dedicated to how digital transformation is the “engine” for a sustainable future, providing the scientific basis for the Twin Transition [8].

In this scenario, the adoption of advanced technologies such as Digital Twins (DTs) offers the opportunity to improve urban and peri-urban resilience: thanks to their ability to integrate real-time data and simulate complex scenarios, these tools can support governance with decision-making, reduce environmental impacts, and promote a more sustainable and adaptive development model [9]. DTs are therefore not just technical tools but the operational pillars of this transition, capable of translating the complexity of environmental data into concrete mitigation actions.

The concept of DT was introduced in the early 2000s, and one of its first applications was in the industrial and manufacturing sector [10]. In 2003, Michael Grieves introduced his concept of a “virtual, digital equivalent to a physical product”, or “Digital Twin”, during his course on “Product Lifecycle Management” at the University of Michigan. The conceptual model proposed for the DT is based on three main parts: the physical product, the virtual product, and the exchange of data between the two [11].

Originally, DT was used as a digital model capable of replicating the behaviour of a physical system in real time: companies, for example, used it to simulate the operation of machines and predict possible failures or inefficiencies [12]. Through integration with data collected in real time by sensors placed on the machinery, it was possible to predict when a machine would need maintenance or identify production defects before they caused problems. During the early years of experimentation, the DT approach and digital representations of real physical products were fairly new and immature. Furthermore, the information collected about the physical product during its production was limited, collected manually, and mostly on paper. However, over the following decade, integration with emerging technologies in the field of information technology, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Big Data, and Artificial Intelligence (AI), led to exponential growth in the application of DT [13,14]. From simple digital replicas of physical components, DTs have evolved into complex, interconnected models capable of representing real systems and environments, expanding their field of application from the industrial world to the urban, environmental, and infrastructural worlds. Current integration with generative artificial intelligence and machine learning is taking DT beyond simple simulation: we are moving from predictive models (what will happen?) to prescriptive models (what should we do?). This technological leap allows urban “stress tests” to be carried out in safe virtual environments before their physical implementation.

It is precisely at this technological juncture that the concept of urban intelligence comes into play, understood as the systematic integration of big data, advanced algorithms, and computing power to understand and manage the complexity of urban systems. It is not only a technical tool, but also the “cognitive” ability of the Digital Twin to process heterogeneous information to optimise urban metabolism and improve quality of life, acting as a digital brain for the city [15].

In recent years, the use of DT has also expanded into the urban environment, giving rise to the so-called Urban Digital Twins (UDTs) or Digital Twin Smart Cities (DTCs) [16,17]. These digital models allow for detailed and dynamic representation and analysis of the complexity of cities, from physical infrastructure (energy networks, transport, buildings) to environmental and social aspects. Through the integration of multi-source data—such as GIS, Building Information Modelling (BIM), IoT sensors, satellite imagery, and public participation data—DT can store enormous amounts of information and return a site-specific and highly realistic representation of urban conditions [18]. According to recent studies [19], DT in cities pursues three visions: (1) more intensive and efficient urban production and functioning; (2) liveable and comfortable urban living spaces; and (3) a sustainable urban ecological environment.

At the same time, the DT paradigm is also extending to natural ecosystems, giving rise to initiatives such as the “Digital Twin of the Ocean (DTO)”—promoted at the European level through programmes such as ILIAD (February 2022–July 2025), EDITO (January 2023–December 2025) and DTO-BioFlow (September 2023–February 2027) [20]. These projects aim to integrate satellite data, in situ observations, and advanced artificial intelligence models to create scalable and robust virtual representations of the marine system. The DTO enables the understanding and simulation of complex interactions between physical, chemical, biological, and anthropogenic processes, improving the ability to monitor and respond to climate change, environmental impacts, and the sustainable management of ocean resources. The application of DT to marine ecosystems is crucial for coastal cities with complex port-city interfaces. For example, integrating an urban digital twin with a marine digital twin (DTO) would enable monitoring not only of industrial emissions on land but also of the impact of spills and port activities on the marine ecosystem, providing a holistic view of environmental risk.

In this historical period, particularly marked by global challenges such as climate change, demographic pressure, and resource scarcity, DT offers governance tools for testing alternative scenarios, assessing the impact of policies or infrastructure interventions, optimising resource allocation and improving the resilience of urban systems [21].

Although the literature on UDT is broad and rapidly growing, it still appears predominantly oriented towards large metropolitan contexts and technological aspects, highlighting a significant research gap: the lack of comparative frameworks capable of guiding the selection and adaptation of such models in peri-urban, environmentally fragile, and resource-limited settings, such as the case of Taranto. To fill this gap, this study aims to analyse and compare the main existing cases of DT applied to cities, focusing on the following research questions: what thematic areas are the focus of current studies, what methodological limitations they present, and whether applied research is currently sufficient for areas of complex environmental conflict. The survey aims to identify the key characteristics and evaluation criteria that must be considered to implement a DT in vulnerable territorial contexts, pursuing a dual objective: on the one hand, to highlight the different technological and management approaches that characterise these models; on the other, to evaluate the potential of the DT as a forecasting tool to support urban resilience. Through the analysis of concrete experiences, the research aims to outline a critical framework that highlights opportunities and limitations, providing useful methodological guidance for future applications in contexts characterised by limited resources and marked vulnerability to climate change.

Based on these premises, the study focuses on a specific sample of international case studies capable of filling the knowledge gap outlined above. The selection also ensured the representativeness of different territorial scales (urban, peri-urban, marine and regional) and different areas of application, including spatial planning, environmental monitoring and resource and infrastructure management. This choice is particularly important because the existing literature on urban DTs is mainly focused on large cities and metropolitan contexts, with a still limited number of contributions referring to small municipalities and peri-urban areas. In this sense, the selected case studies allow us to broaden our knowledge, offering examples that can potentially be transferred to complex territorial contexts such as that of the city of Taranto.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology adopted is based on a multidimensional qualitative-comparative approach. The aim is to go beyond a simple technological description and arrive at a critical analysis of the enabling factors that make DT effective urban intelligence tools. The research is structured to compare heterogeneous experiences, assessing how the “Twin Transition” is implemented in different geographical and institutional contexts [22], with a specific focus on the transferability of models to complex contexts such as that of Taranto.

The first phase involved a systematic literature review, ensuring rigour, transparency, and reproducibility. The research strategy was based on a predefined Boolean string combining the main thematic domains of the study. The core search string was: (“Digital Twin” OR “Urban Digital Twin”) AND (“Smart City” OR “Urban Resilience”) AND (“Peri-urban” OR “Climate Change” OR “Pollution” OR “Sustainable Planning”). Searches were applied to the title, abstract, and keyword fields when supported by the database. The literature search was conducted between September and November 2025 using academic and scientific databases, such as Google Scholar, which was used as the main search engine, through which it was possible to access various internationally renowned academic databases, including Scopus, ScienceDirect, MDPI, and IEEE Xplore. ResearchGate was used as a supplementary platform for retrieving full-text versions of publications that had already been identified through indexed academic databases: this ensured access to complete manuscripts without influencing the selection process. The time range was limited to publications from 2021 to 2025 to ensure that only the most recent contributions were included.

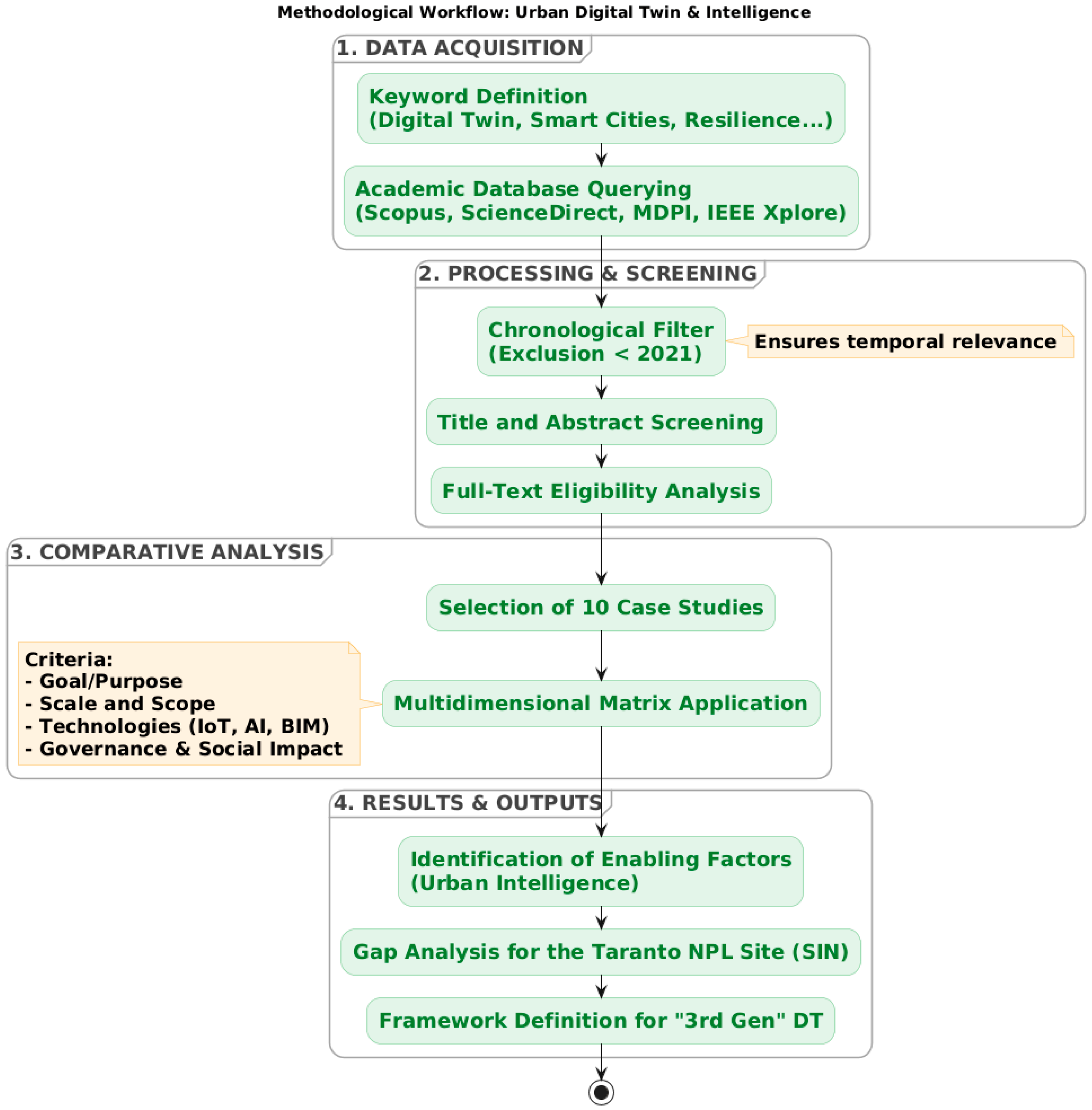

Furthermore, the selection process was structured in two phases to ensure accuracy: the first phase, screening, was conducted on the basis of an in-depth analysis of the title and abstract of the contributions, identifying publications considered potentially consistent with the research objectives. The second phase, eligibility, involved analysing the full text of the pre-selected articles to confirm their direct and specific relevance to the topic of this study. This step led to the identification of case studies to be subjected to comparative analysis [23] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The methodological workflow.

2.1. Analysis of Case Studies and Comparative Matrix

A focal point of the methodology concerned the selection and analysis of specific case studies emerging from the literature. In order to guarantee the objectivity of the research, the selection of case studies was conducted following a scoping review protocol, filtering experiences based on the availability of technical data and relevance to urban and peri-urban contexts. The resulting comparative matrix is not only descriptive, but it also offers a robust evaluative framework. By applying a qualitative multi-criteria scoring system, each case study was assessed to determine its alignment with five fundamental criteria. These pillars evaluate the complexity and relevance of DT territorial applications in direct relation to the strategic objectives of the European Twin Transition. The assessment was conducted collectively by all authors through a qualitative ordinal scale (low, medium, high relevance), based on the level of correspondence between each case study and the predefined criteria. This qualitative, criteria-based approach enables the development of a replicable methodological framework that can be applied in other territorial contexts, supporting the selection and adaptation of digital twin solutions beyond the specific case studies analysed.

Additionally, this approach makes it possible to map not only the current state of technology but also the “implementation gap” between the different urban realities analysed. This matrix has made it possible to systematically characterise the contributions according to the following parameters [24] (Table 1):

Table 1.

Table of criteria used for the DT comparative matrix.

2.2. Methodology for Comparative Evaluation of AI Algorithms

Considering how important computing is in ‘third-generation’ digital twins, the study uses a comparative evaluation protocol to figure out which AI algorithms work best for complex urban and peri-urban settings. This evaluation is not just about how efficient the algorithms are, but also how well the model can work as a Decision Support System (DSS).

The comparison is divided into three main technological clusters, analysed in terms of their applicability to the chosen case study:

- Supervised Machine Learning (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost), for the prediction of discrete variables, such as air pollution peaks, trends in soil and water matrices, or energy demand, based on historical data series;

- Deep Learning and Neural Networks (e.g., LSTM, CNN) for processing high-frequency unstructured data, which is essential for artificial vision from satellite images (Copernicus) and the modelling of dynamic flows (traffic, microclimate, environmental offences such as littering and illegal discharges into water);

- Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) for their ability to act as conversational interfaces between DT and policymakers, facilitating the interrogation of complex data through natural language.

For each algorithm identified in the literature, an evaluation metric based on the following KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) is applied [25,26]:

- Predictive accuracy measured through statistical indicators such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Coefficient of Determination (R2) for the validation of environmental simulation models;

- Interpretability (Explainable AI–XAI) as a crucial criterion for governance. The extent to which the algorithm is a “black box” or allows for understanding the variables that generated a given output is assessed, which is essential for justifying policy choices in sensitive areas;

- Computational Efficiency and Latency understood as the algorithm’s ability to process data in real time (Edge Computing) to respond to sudden critical events (e.g., industrial accidents or extreme weather events);

- Algorithm generalisation, understood as its adaptability, based on appropriate training, to one context (e.g., dense urban area) and successfully applied to another (e.g., peri-urban or agricultural area).

2.3. Focus on the Taranto Context

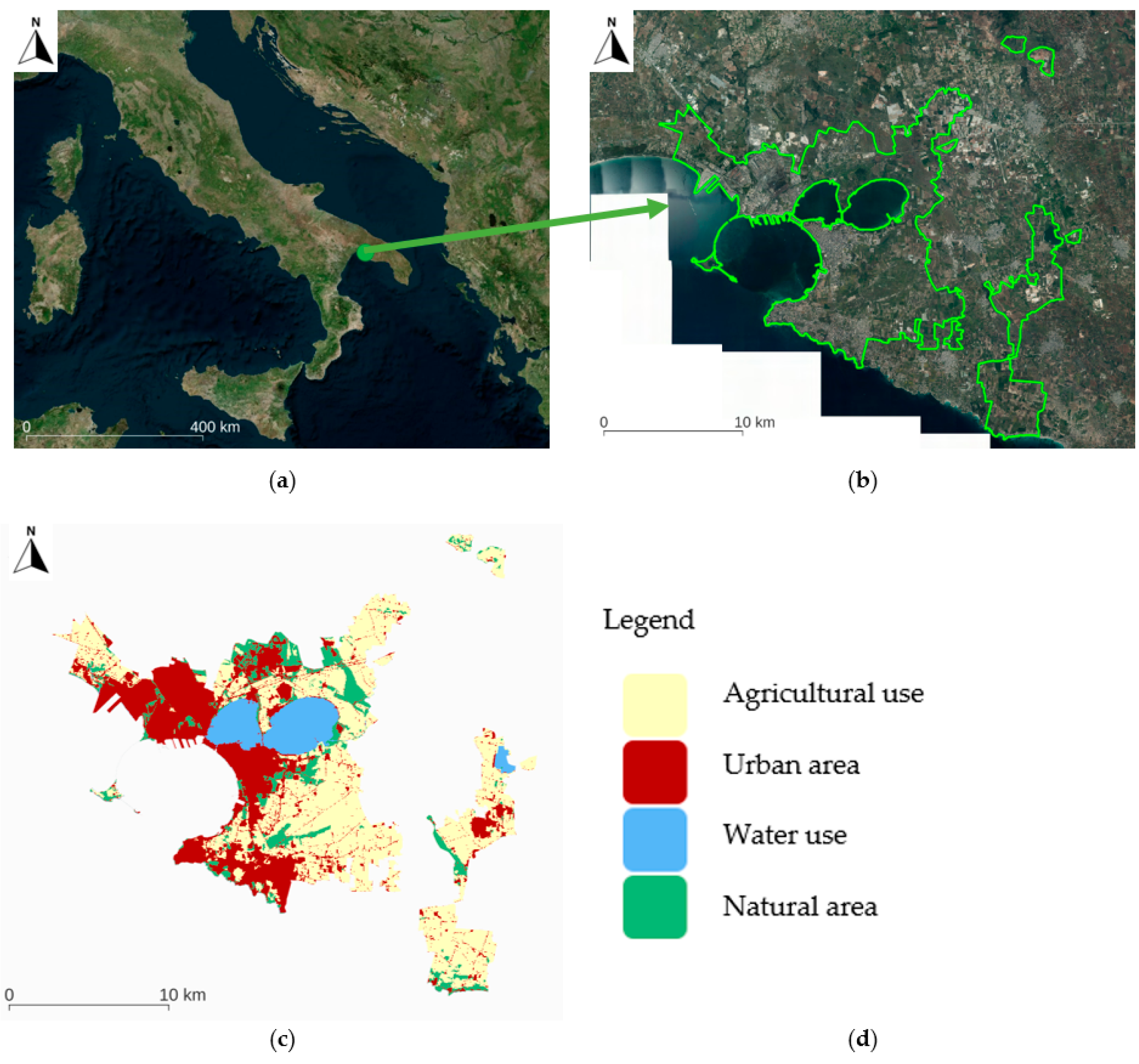

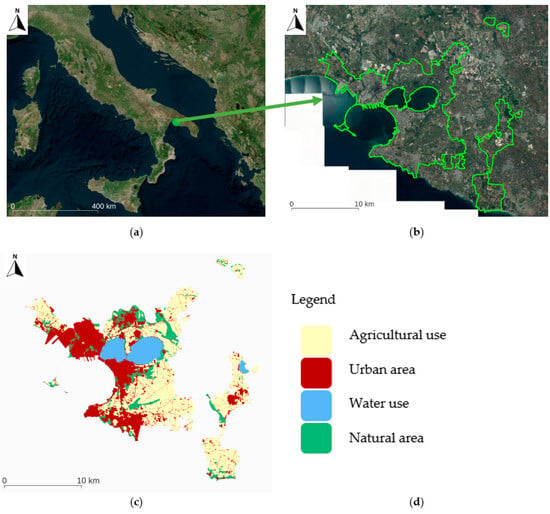

The final methodological phase involves the critical transposition of the results of the case studies to the context of Taranto (Figure 2). This territorial reality represents an emblematic and extremely complex case study, characterised by a deeply layered set of environmental, social and economic values that are often in conflict with each other.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Framing and zooming in on the study area. (c) Overview of land use in Taranto, (d) where it is possible to see the presence of the industrial hub, natural areas, urban environments, and some aspects of the marine ecosystem.

On the one hand, Taranto is home to one of the largest industrial centres in Europe, which has led to the area’s inclusion among the Sites of National Interest (SIN) due to the need for remediation and constant monitoring of environmental matrices. On the other hand, the city possesses an extraordinary naturalistic and historical identity, founded on its conformation as the “City of Two Seas”. The Little Sea, in particular, is a unique ecosystem characterised by the presence of “citri” (underwater freshwater springs) and a rare biodiversity that includes one of the most important populations of seahorses (Hippocampus) in the Mediterranean. This heritage, together with the Cheradi Islands and the coastal strip, requires rigorous conservation strategies to preserve vital ecosystem services and promote sustainable urban regeneration.

Through a gap analysis, the study identifies which components of the analysed frameworks are essential to manage this scenario, where the need to balance industrial, healthcare, and environmental data requires a very high-resolution “third-generation” digital twin. This tool must be able to integrate industrial emissions modelling with real-time monitoring of water and air quality, acting as a mediation platform between economic development and safeguarding the well-being of the local community [27].

3. Results

The methodological survey made it possible to map an extensive corpus of scientific and technical literature. The initial identification phase was carried out by applying predefined keyword combinations related to DT, smart cities, urban resilience, climate change, and territorial planning to major academic databases and using searches in titles, abstracts and discussions. This broad query returned an aggregate set of over 600,000 records, reflecting the wide diffusion of the topics across multiple research domains. The application of strict chronological inclusion criteria (time range from 2021 to 2025) subsequently narrowed the dataset to approximately 25,000 contributions, ensuring alignment with the most recent technological and methodological developments.

Through systematic screening of titles and abstracts, 100 potentially relevant contributions were isolated and subsequently subjected to a full-text eligibility review. This process yielded 40 articles closely focused on the intersections between urban resilience, climate adaptation and the territorial implementation of DT.

At the end of the selection process, 10 case studies of excellence were identified using a strategy based on predefined evaluation criteria. The reduction from the initial set of 40 contributions was made following the application of the comparative evaluation matrix, through which the case studies were analysed in relation to their degree of relevance to the identified methodological criteria. The 10 cases selected were found to be the most consistent and relevant to the research objectives, demonstrating a high level of adherence to the criteria relating to territorial scale, technological integration, data type, operational and governance models.

The following table organises the 10 selected case studies, and it is structured to highlight the transition from descriptive to prescriptive models, categorising each experience according to its strategic objective, scale of intervention and integration technologies (IoT, AI, GIS). This schematisation allows the identification of the “best-in-class” for each functional area, providing reference parameters for the subsequent gap analysis in the context of the Taranto SIN (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparative matrix of case studies selected for the implementation of urban digital twins (2021–2025).

A systematic analysis of the selected contributions highlights how DT is now being applied in different ways in dense urban contexts and peri-urban areas, taking on specific technological and operational configurations depending on the objectives of planning, management and resilient monitoring. The case studies examined show a clear evolutionary path: DT is completing its metamorphosis from a static digital model—understood as a mere 3D geometric replica—to a dynamic, integrated and data-driven system. This evolution allows it to move from a purely descriptive function to a prescriptive capability, able to support complex decision-making processes through the simulation of “what-if” scenarios in real time. The comparative analysis also highlights a strategic convergence towards the digital green transition approach. While the first iterations of DT focused mainly on participatory visualisation and building asset management (BIM-based), the more advanced models of the 2024–2025 period (such as the cases of Matera and Florence) natively integrate the Urban Intelligence layer. This cognitive level allows for the processing of multi-risk analyses and predictive maintenance protocols, enabling cities to react preventively to climate shocks or systemic inefficiencies. This change of pace confirms that the DT is no longer configurable as an isolated “product” or vertical software but as an interoperable City Twin Platform. This platform acts as an open ecosystem, capable of communicating with national infrastructures, local sensor networks (IoT) and health or environmental databases. From this perspective, the platform becomes the operational pillar for ensuring dynamic resilience, transforming the complexity of urban data into concrete and measurable mitigation actions, in line with the climate neutrality objectives set by the European Green Deal.

The evaluation framework is divided into five dimensions, summarised in Table 1. The following subsections provide a detailed examination of each pillar: objectives, scale, technologies, data and governance.

3.1. Objective and Purpose of the Digital Twin

The case study survey shows that DTs are mainly adopted as an integrated paradigm for planning and strategic support for public policy decision-making processes. The DUET project (Digital Urban European Twins), implemented in cities such as Athens, Pilsen and Brussels, highlights the use of DT as a platform (City Twin platform) for evaluating alternative scenarios through the integration of 3D urban modelling, IoT data and Big Data, enabling the simultaneous analysis of traffic, air quality and noise pollution in real time. Similarly, in the cases of Helsinki and Zurich, DT supports urban planning, simulation and management processes, enabling the visualisation and analysis of complex scenarios related to urban densification, microclimatic comfort and urban climate dynamics.

3.2. Application Scale and Thematic Scope

With regard to the scale of application and thematic scope, there is a prevalence of applications at the urban and metropolitan level, with sectoral extensions including energy, mobility, environment and risk management. The cases of Singapore and Rotterdam are advanced examples of multi-domain DT, applied, respectively, to the integrated management of complex urban systems and to logistics and transport in port and peri-urban contexts. In non-strictly urban contexts, such as the marine environment, DT is mainly used for environmental monitoring and ecosystem modelling, confirming a greater functional specialisation compared to established urban contexts.

3.3. Supporting Technologies Adopted

Concerning the criteria for technologies adopted to support DT, all case studies highlight a strong integration of enabling technologies such as GIS, BIM, IoT, and Big Data. In more advanced contexts, such as Singapore and Matera, DT also incorporates Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) algorithms for predictive simulation, adaptive management, and decision-making support. One innovative element that emerged from the analysis of the most advanced frameworks (such as those applied in Singapore and Matera) concerns the integration of Explainable AI (XAI) techniques. In the critical context of Taranto, the application of XAI algorithms (such as SHAP—Shapley Additive exPlanations or LIME) makes it possible to overcome the “black box” limitation of artificial intelligence. For example, in a system for monitoring the dispersion of pollutants (PM10, SOx, NOx), an XAI algorithm does not merely predict when legal limits will be exceeded but provides policy makers with an “explanation” of the phenomenon. By calculating SHAP values, DT can indicate the relative weight of different variables in real time. In this way, the system could highlight that a specific alert is caused by a certain percentage of the wind direction coming from the industrial area and by another percentage of the ground temperature and peri-urban vehicle traffic. This transparency is crucial for the governance of Taranto, as it allows for the issuance of targeted and scientifically motivated ordinances, reducing conflicts with industrial and social stakeholders [38].

3.4. Data Typology and Interoperability

The effectiveness of the DTs analysed is strongly linked to the type of data used. The most advanced implementations are based on multi-source data environments, integrating static datasets with real-time sensor data. Urban DTs such as those in Helsinki, Singapore, Matera and Florence demonstrate high levels of data interoperability, often relying on open standards (e.g., CityGML, OGC-compliant services) to enable semantic integration and cross-domain analysis. In marine and environmental applications, DTs support data fusion and three-dimensional visualisation of large-scale environmental datasets, enabling autonomous learning and intelligent prediction of oceanographic and meteorological events.

3.5. Governance and Social Impact

Finally, governance emerges as a key dimension that distinguishes different DT applications. Several cases highlight the role of DTs as tools to support decision-making, stakeholder coordination and citizen engagement. The Herrenberg case illustrates an innovative participatory approach, which integrates environmental simulations with emotional and perceptual data collected via apps and virtual reality, thus strengthening the social dimension of planning processes. In Matera, DTs are explicitly designed to support governance through artificial intelligence-based reasoning, environmental monitoring, and transparency in decision-making.

3.6. Comparative Benchmark of Algorithms for Urban Intelligence

The analysis of existing literature and technical evaluation of identified frameworks reveals that the effectiveness of a digital twin depends not only on the volume of data collected but rather on the algorithmic logic employed for data processing. No universally valid algorithm exists for urban complexity; algorithm selection entails trade-offs among predictive accuracy, computational cost, and explainability.

Based on the criteria defined in the methodology, a comparative benchmark of the three predominant algorithm families in third-generation digital twins was developed. Table 3 summarises the performance of these technological clusters in relation to environmental monitoring and governance requirements. It should be noted that this table represents a qualitative synthesis and meta-analytical evaluation of the findings that emerged from the reviewed literature and existing technical frameworks, rather than an original empirical benchmark based on experimental laboratory tests.

Table 3.

Comparative benchmark of AI algorithms for urban digital twin applications.

Deep learning algorithms offer superior performance for modelling complex dynamic phenomena, typical of a port-city interface such as Taranto, where pollutant dispersion is influenced by nonlinear variables (wind patterns, orography, traffic) [39]. However, the black-box nature of these models limits their use in public governance: decision-makers cannot justify restrictive measures (e.g., industrial or traffic bans) based on unexplainable algorithmic outputs [40,41].

Conversely, traditional ML algorithms offer greater native transparency, enabling visualisation of variable feature importance, but demonstrate accuracy limitations when handling massive and unstructured datasets. A rare example of a comprehensive application with a feedback loop on real-world data is represented by Zhang et al. (2022); our framework intends to extend such an approach from the industrial process to the scale of complex urban systems [42]. The solution identified in the most advanced state of the art (2024–2025) resides in the integration of XAI modules.

The application of model-agnostic methods such as SHAP enables interpretation and transparency of deep learning model predictions [43]. In a SIN context, this hybrid approach serves two purposes. NN maintains high monitoring accuracy. XAI methods ensure transparency, allowing administrators to identify pollution sources (industry or traffic).

The comparative analysis of ten case studies (Table 2) in concordance with the algorithmic benchmark (Table 3) reveals a clear correlation between data typology and the class of algorithms adopted. Based on the complexity of the territorial problem and the computational architecture selected, it is possible to categorise the applicability of algorithms in the analysed case studies into distinct clusters (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparative overview of the selected case studies, clustered by application domain and corresponding AI algorithms, highlighting the use of deep learning, computer vision, traditional machine learning, and XAI approaches.

The first cluster addresses DL and NN for managing complex and non-linear flows. In high-density urban contexts or port environments, where the objective is real-time management of dynamic systems (traffic, pollution, logistics), DL and time series analysis models predominate. Exemplary cases include Singapore and Rotterdam, which demonstrate how managing vast heterogeneous datasets necessitates predictive capabilities that surpass traditional ML. Similarly, in the DUET project (Athens, Pilsen), the requirement to correlate vehicular traffic and air quality in real time drives the adoption of high-precision models, where forecasting accuracy is prioritised over immediate interpretability.

The second cluster encompasses computer vision and spatial AI for morphological and environmental monitoring. This applies to the cases of Florence and Draguc, where the priority is the conservation of historical heritage. Here, AI does not process temporal flows but analyses geometric and visual data to identify structural degradation or morphological anomalies. Analogously, in the digital twin of the ocean, the integration of satellite data and in situ observations requires artificial vision algorithms to model complex phenomena and support the blue economy.

The final third cluster concerns traditional ML and Explainable AI (XAI) for governance and participatory processes. This applies to contexts in which the digital twin functions as a decision support system (DSS) or social engagement tool, where the necessity for transparent algorithms or techniques integrated with explainable AI emerges. The case of Matera represents the most advanced example of this trend toward cognitive “urban intelligence.” Here, the use of “AI-based reasoning” serves not only to predict but to support complex decision-making by integrating tourism and environmental data. Similarly, in the Herrenberg case, the use of emotional and participatory data suggests the employment of algorithms capable of processing qualitative inputs, approaching the frontiers of generative AI for citizen-institution interaction. This alignment between the technological framework and algorithmic choice constitutes the enabling factor for model replicability in critical contexts such as Taranto.

4. Discussion

4.1. The ‘Twin Transition’ as a Driver of Regeneration

Overall, the analysis of the case studies highlights shared models and significant differences in terms of scale, technologies and governance. This comparison makes it possible to bridge the implementation gap between different territories while promoting the transferability of DT solutions. Furthermore, the survey shows that DTs are evolving towards integrated multi-domain platforms, powered by real-time semantic data and advanced technologies such as AI, ML and IoT. These systems are not limited to territorial planning and management but also enhance decision-making and participatory processes, proving to be essential in contexts characterised by high environmental, infrastructural and cultural complexity.

Based on the case studies analysed, it is clear that for a context such as Taranto, adopting an isolated digital model is not sufficient; rather, an integrated City Twin Platform is required. The particular nature of Taranto, classified as a Site of National Interest (SIN) for its high level of environmental compromise, requires a quantum leap: DT must not be limited to “photographing” the existing situation but must act as a virtual laboratory for prescriptive governance. This approach is the only one capable of resolving the historical conflict between industrial development and health protection, allowing decision-makers to test the effectiveness of remediation measures or new green infrastructure in a simulated environment, reducing the risks of failure and optimising the use of economic and environmental resources.

A key point for the success of this initiative lies in the very nature of the technological tools adopted. Taranto’s future digital architecture must be based on open-source standards [44,45,46]. This choice ensures interoperability between different systems, allowing, for example, data on marine monitoring of the Mar Piccolo to instantly communicate with urban air quality models. Adopting open-code software means avoiding so-called vendor lock-in, ensuring that knowledge and data remain a public good that can be managed autonomously by local governments and accessible to the scientific community, promoting a culture of transparency that underlies every process of urban resilience. However, technology alone is not enough if it is not supported by constant methodological rigour. The integration of artificial intelligence algorithms must always be accompanied by the use of standardised performance metrics to prevent models from deviating from physical reality. In socially sensitive contexts like Taranto, where every decision can have repercussions on citizens’ health, the use of Explainable AI (XAI) becomes imperative. Through tools such as SHAP values, the DT can explain the motivations behind an alert or operational suggestion, transforming complex algorithms into understandable and verifiable information. This explainability is the necessary bridge to build trust between institutions and citizens, ensuring that environmental policies are based on solid and indisputable scientific evidence. The Twin Transition as an engine of rebirth. Ultimately, the path to a digital twin for Taranto fits perfectly into the European paradigm of the “twin transition,” where the digital revolution becomes the catalyst for the ecological transition. The study shows that territories with a heavy industrial past must not resign themselves to decline but can become pioneers in the use of frontier technologies for regeneration. Investing in an urban intelligence infrastructure means equipping Taranto with a “dynamic memory” and “forecasting capability” that make it not only more resilient to climate change but also a role model for other European cities facing similar challenges.

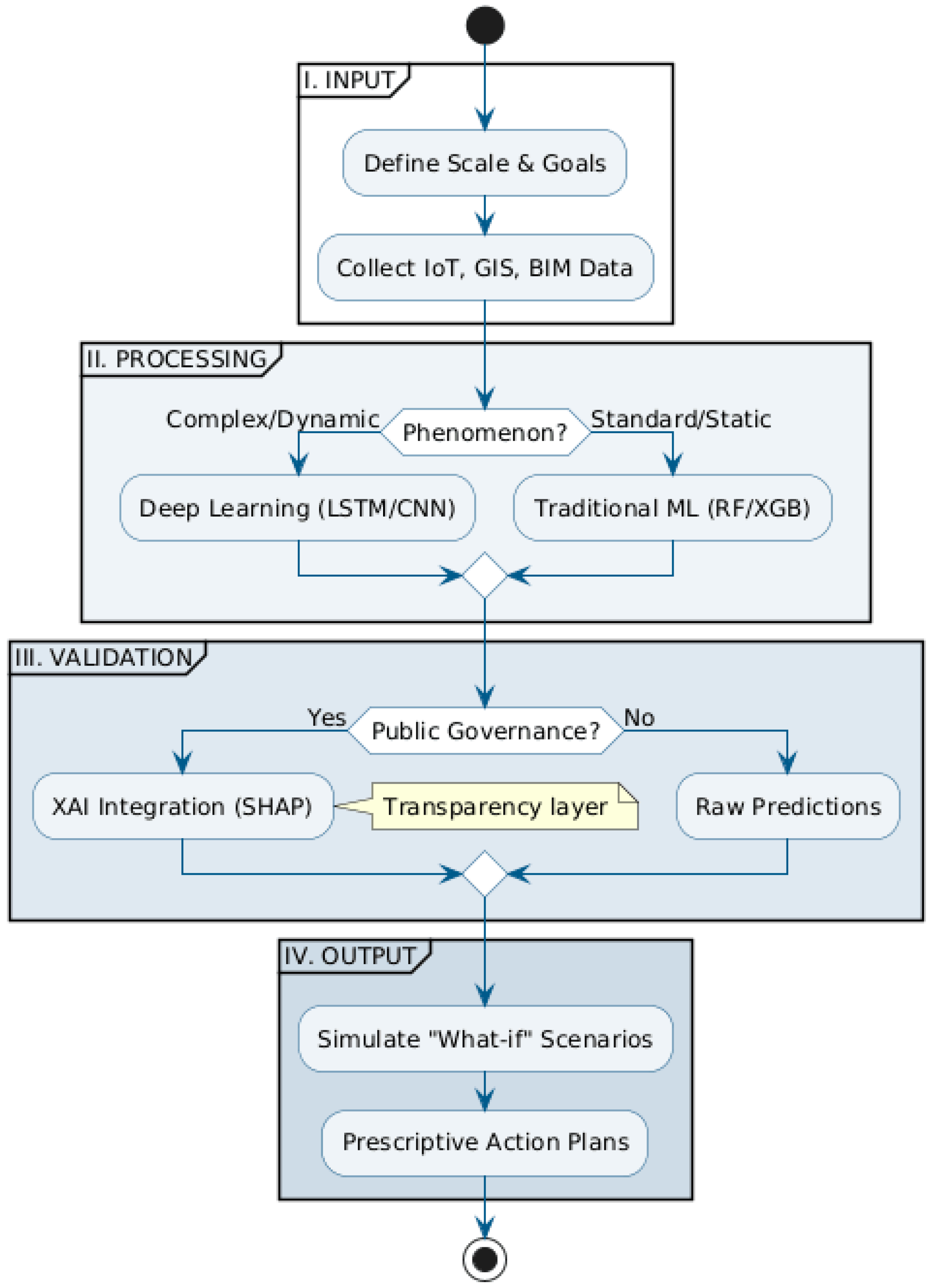

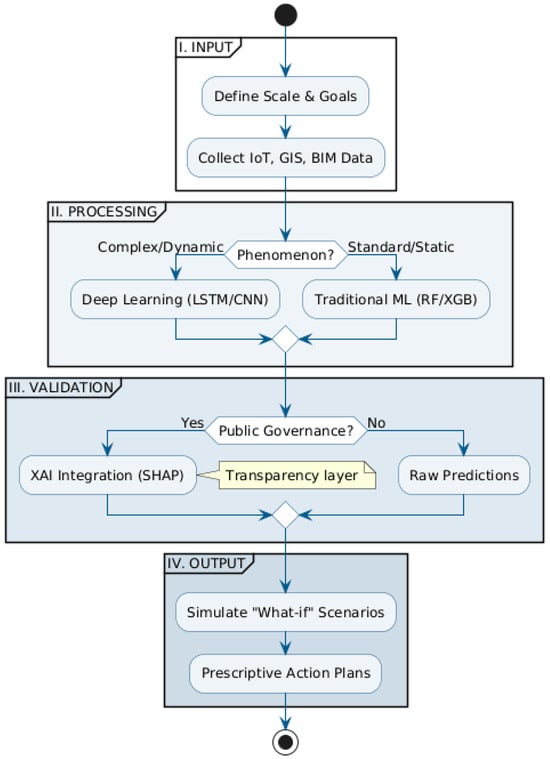

Completing the investigation, the proposed workflow outlines the methodological transition towards urban governance based on scientific evidence and algorithmic transparency. This logical structure organises the complexity of big data and artificial intelligence in a linear process that starts from multi-source acquisition (IoT, BIM, GIS) to arrive at a real prescriptive capacity. The heart of the system lies in the balance between the accuracy of deep learning models and the need to “open” these black boxes via XAI modules, ensuring that each “what-if” scenario simulation is understandable and defensible by public decision-makers [47]. In this framework, the digital twin ceases to be a mere aesthetic representation to transform itself into a dynamic city twin platform, capable of guiding the twin transition through targeted and scientifically validated mitigation interventions [48] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Digital twin decision logic.

From this perspective, the case of Taranto can be considered as an exploratory context useful for investigating the scalability and replicability potential of the proposed model, rather than as an exhaustive demonstration of its transferability. The adoption of a modular architecture based on open-source standards appears consistent to promote progressive adaptations of the framework to urban contexts characterised by different environmental, infrastructural and institutional settings. However, extending the approach to other SIN or port-industrial cities would require further validation phases, as well as a recalibration of models and metrics in relation to the availability and quality of local data. In this context, the replicability of the model should not be understood as a simple technical transposition, but as an adaptive and iterative process, whose effectiveness depends on the ability to integrate territorial specificities within a shared methodological framework.

4.2. Limitations of the Study

Despite the systematic approach adopted, this research presents some limitations that should be acknowledged. The research was limited to a specific time range (2021–2025) to ensure technological relevance; however, this may have excluded longitudinal studies or earlier foundational projects that could offer insights into the long-term evolution of digital twins. Furthermore, while the selection of 10 “best-in-class” cases allowed for a deep-dive analysis, it represents only a fraction of the rapidly growing global ecosystem of urban digital twins.

From a methodological point of view, the comparative matrix and the relevance scoring (low, medium, high) were based on a qualitative assessment conducted collectively by the authors. Although supported by literature benchmarks, this approach involves an inherent degree of subjectivity that could lead to different interpretations if applied by other research groups. The benchmark of AI algorithms is a qualitative synthesis of existing literature. Consequently, the performance indicators (e.g., predictive accuracy and latency) are based on reported data from previous studies rather than on a standardised, side-by-side empirical test using a single reference dataset.

In addition, the study identifies a framework for the city of Taranto through a gap analysis and a critical transposition of results. While this provides a robust methodological roadmap, the framework has not yet been empirically tested through a full-scale physical implementation in the field.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the research demonstrated how, in the 2025 Twin Transition landscape, digital twins have evolved from simple virtual replicas to sophisticated urban intelligence systems. Through a systematic scoping review of the literature and a comparative analysis of ten international frameworks—from Singapore to Matera—, it is clear that the effectiveness of these tools lies in their ability to move from descriptive to prescriptive models. This technological leap, supported by the integration of IoT sensors and satellite data, allows urban governance to test environmental “stress tests” in secure digital environments, optimising territorial resilience in the face of climate uncertainty. A focal point of the study concerns the adoption of a rigorous approach in the evaluation of Artificial Intelligence algorithms. The use of techniques such as SHAP values ensures the transparency of decision-making processes, allowing us to break down the complexity of data and explain to citizens and policymakers the variables (climatic, industrial, or social) that determine a specific urban alert or choice. Finally, the application of this framework to the case of Taranto highlights the need for an open-source and interoperable platform. For a Site of National Interest (SIN) characterised by a complex stratification of industrial pollutants and the need for regeneration, the Digital Twin represents the only infrastructure capable of harmonising environmental monitoring with public health protection. In summary, the work emphasises that only through data sovereignty, the use of open standards, and algorithmic clarity will it be possible to transform historically vulnerable areas into adaptive, sustainable, and challenge-ready urban ecosystems of the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.M. and C.M.; methodology, V.M. and C.M.; validation, V.M., C.M. and M.S.B.; formal analysis, V.M.; investigation, V.M.; resources, V.M.; data curation, V.M., C.M. and M.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.M.; writing—review and editing, V.M., C.M. and M.S.B.; visualization, V.M., C.M. and M.S.B.; supervision, C.M. and M.S.B.; project administration, C.M.; funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further in-quiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Gemini Pro to improve the quality of English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Result; New York, NY, 2024. Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Summary-of-Results.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Concepción, E.D. Effects of counter-urbanization on Mediterranean rural landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, C.; Matarrese, R.; Uricchio, V.F.; Muolo, M.R.; Laterza, M.; Ernesto, L. Detection of asbestos-containing materials in agro-ecosystem by the use of airborne hyperspectral CASI-1500 sensor including the limited use of two UAVs equipped with RGB cameras. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 2135–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufiane, I.M.; Djaouad, R.D.; Farah, B.; Djamel, S. Spatiotemporal Impact of Urbanization on Urban Heat Island Using Landsat Imagery in Oran, Algeria: 1984–2024. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, M.; Dutta, H.; Minerva, R.; Crespi, N.; Raza, S.M.; Herath, M. Global perspectives on digital twin smart cities: Innovations, challenges, and pathways to a sustainable urban future. In Sustainable Cities and Society; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework. In Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 2289–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUR-Lex, Access to European Union Law. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52022DC0289 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Muench, S.; Stoermer, E.; Jensen, K.; Ahola, S.M.; Scapolo, F. Towards a Green & Digital Future: Key Requirements for Successful Twin Transitions in the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Liu, Z.; Efremochkina, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. Study on city digital twin technologies for sustainable smart city design: A review and bibliometric analysis of geographic information system and building information modeling integration. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 84, 104009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieves, M.; Vickers, J. Digital Twin: Mitigating Unpredictable, Undesirable Emergent Behavior in Complex Systems. In Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Complex Systems; Kahlen, J., Flumerfelt, S., Alves, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC Pap. 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, T.; Deng, X.; Liu, Z.; Tan, J. Digital twin: A state-of-the-art review of its enabling technologies, applications and challenges. J. Intell. Manuf. Spec. Equip. 2021, 2, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minerva, R.; Lee, G.M.; Crespi, N. Digital Twin in the IoT Context: A Survey on Technical Features, Scenarios, and Architectural Models. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.I.K.; Huang, H.; Xu, X. Digital Twin-driven smart manufacturing: Connotation, reference model, applications and research issues. In Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Goodchild, M.F.; Batty, M.; Kwan, M.-P.; Zhang, A. The Urban Book Series. n.d. Available online: http://www.springer.com/series/14773 (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Batty, M. Digital twins. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2018, 45, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré-Bigorra, J.; Casals, M.; Gangolells, M. The adoption of urban digital twins. Cities 2022, 131, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahat, E.; Hyun, C.T.; Yeom, C. City digital twin potentials: A review and research agenda. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Merritt, J. Digital Twin Cities: Framework and Global Practices; Insight Report; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Digital Twin of the Ocean (DTO). Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-and-open-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe/restore-our-ocean-and-waters/european-digital-twin-ocean-european-dto_en (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Yessef, M.; Hakam, Y.; Tabaa, M.; Alammar, M.M.; Elbarbary, Z.M.S. Digital twin technology in smart cities: A step toward intelligent urban management. Energy Rep. 2025, 14, 5539–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBalkhy, W.; Karmaoui, D.; Ducoulombier, L.; Lafhaj, Z.; Linner, T. Digital twins in the built environment: Definition, applications, and challenges. Autom. Constr. 2024, 162, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lv, Y.; Wang, Q.; Sun, B.; Han, D. A Systematic Review of the Digital Twin Technology in Buildings, Landscape and Urban Environment from 2018 to 2024. Buildings 2024, 14, 3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, D.; Susi, M.; Gioia, C. GHASP: A Galileo HAS parser. GPS Solut. 2023, 2, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, T.; Papapetrou, P.; Zdravkovic, J. Artificial intelligence in digital twins—A systematic literature review. Data Knowl. Eng. 2024, 151, 102304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lartey, D.; Kris, M.Y. Law, Artificial intelligence adoption in urban planning governance: A systematic review of advancements in decision-making, and policy making. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 258, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agenzia per la Protezione dell’Ambiente e per i Servizi Tecnici (APAT). Manuale per Le Indagini Ambientali Nei Siti Contaminati; (Manuali e linee guida, n. 43/2006); ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Raes, L.; Michiels, P.; Adolphi, T.; Tampere, C.; Dalianis, A.; McAleer, S.; Kogut, P. DUET: A Framework for Building Interoperable and Trusted Digital Twins of Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Comput. 2022, 26, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotter, G.; Hürzeler, C. The Digital Twin of the City of Zurich for Urban Planning. PFG J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2020, 88, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembski, F.; Wössner, U.; Letzgus, M.; Ruddat, M.; Yamu, C. Urban digital twins for smart cities and citizens: The case study of herrenberg, germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, K.; McAfee, M.; Gharbia, S.S. Management of Climate Resilience: Exploring the Potential of Digital Twin Technology, 3D City Modelling, and Early Warning Systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprari, G.; Castelli, G.; Montuori, M.; Camardelli, M.; Malvezzi, R. Digital Twin for Urban Planning in the Green Deal Era: A State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Benedictis, R.; Cesta, A.; Pellegrini, R.; Diez, M.; Pinto, D.M.; Ventura, P.; Stecca, G.; Felici, G.; Scalas, A.; Mortara, M.; et al. Digital twins for intelligent cities: The case study of Matera. J. Reliab. Intell. Environ. 2025, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yang, J.; Huang, B.; Ma, C.; Tian, F.; Ge, L.; Xia, L.; Li, J. Toward digital twin of the ocean: From digitalization to cloning. Intell. Mar. Technol. Syst. 2023, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, M.; Zun, Z.; Qian, X. Multi-aspect applications and development challenges of digital twin-driven management in global smart ports. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2021, 9, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagonić, B.; Markovinović, D.; Matijević, H.; Redovniković, L. Integration of Digital Twin Technologies in Urban Regeneration of a Small Historic Town in Europe. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucci, G.; Meucci, A.; Fiorini, L.; Conti, A. Data Quality in Urban Digital Twins: Challenges in the Virtualization of Florence’s Historic Heritage. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 48, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, E.; Nassif, N. Artificial intelligence in environmental monitoring: In-depth analysis. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahim, M.; Sharma, V.; Cao, T.V.; Canberk, B.; Duong, T.Q. Machine Learning-Based Digital Twin for Predictive Modeling in Wind Turbines. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 14184–14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiao, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ma, T.; He, L. A survey of human-in-the-loop for machine learning. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 135, 364–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, K.; Sun, Y.; Tan, S.; Udell, M. Why should you trust my explanation? Understanding uncertainty in LIME explanations. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, X. A digital twin dosing system for iron reverse flotation. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 63, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. A Comparative Analysis of Model Agnostic Techniques for Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Res. Rep. Comput. Sci. 2024, 3, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarelli, C.; Binetti, M.S.; Triozzi, M.; Uricchio, V.F. A First Step towards Developing a Decision Support System Based on the Integration of Environmental Monitoring Activities for Regional Water Resource Protection. Hydrology 2023, 10, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, M.S.; Campanale, C.; Uricchio, V.F.; Massarelli, C. In-Depth Monitoring of Anthropic Activities in the Puglia Region: What Is the Acceptable Compromise between Economic Activities and Environmental Protection? Sustainability 2023, 15, 8875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, M.S.; Uricchio, V.F.; Massarelli, C. Isolation Forest for Environmental Monitoring: A Data-Driven Approach to Land Management. Environments 2025, 12, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, J.M. Environmental management using a digital twin. Environ. Sci. Policy 2025, 164, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, R. Big Data-Informed Urban Design; Global Forum on Urban and Regional Resilience; ETH Zurich: Zurich, Switzerland, 2014; Available online: https://it.scribd.com/document/373404586/Big-Data-Informed-Urban-Design (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.