Abstract

This study conceptually examines, using multi-agent simulation-based traffic flow analysis, how the communication range and penetration rate of connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) influence route choice behaviour, traffic flow distribution, and CO2 emissions. We consider an environment in which CAVs exchange local traffic information and show that traffic congestion mitigation and emission reduction may emerge from the structure of information sharing itself, even without centralised or highly coordinated vehicle control. The results indicate that CO2 emissions respond nonlinearly to the combination of CAV penetration rates and communication ranges, with emission reduction effects becoming evident once penetration exceeds a certain threshold. When communication ranges are limited, relatively high CAV penetration rates are required for such effects to materialise, whereas excessively expanding the communication range is not necessarily desirable, as moderately constrained information sharing can instead promote traffic flow dispersion. By comparison with a reference regime corresponding to user equilibrium under homogeneous information, the analysis suggests that restricting communication ranges introduces spatial heterogeneity in information availability, which can lead to emergent improvements in traffic flow through decentralised route choice. Although individual CAVs act selfishly, the aggregation of local information-based decisions may give rise to swarm-intelligence-like effects at the system level. This study does not aim to predict real-world traffic conditions or emissions, but rather to elucidate the causal mechanisms through which information-sharing structures shape traffic system dynamics under simplified conditions.

1. Introduction

Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) technology have ushered in a transformative era in road transport, marked by the emergence of autonomous vehicles and the development of highway congestion modelling. Accordingly, the development of intelligent transportation systems (ITS), in which people, roads and vehicles exchange information, has attracted considerable attention. Within ITS, the intelligent capabilities of vehicles are expected to enable more effective utilisation of road traffic information.

Existing research on vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication has largely focused on platoon control for autonomous driving or accident avoidance [1,2,3], whereas relatively few studies have examined the use of such information for route selection [4]. Moreover, studies that explicitly employ local information for route selection remain limited [5].

Accordingly, this study examines the extent to which CO2 emissions can be reduced when connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) equipped with V2V communication utilise locally acquired traffic information for route choice. It should be emphasised that this study does not propose a novel routing algorithm or a new theoretical traffic model; rather, it is positioned as a conceptual exploration aimed at clarifying how differences in information structures influence the behaviour of traffic systems at the network level.

Many existing studies on eco-routing [4,6] and traffic information provision [7] implicitly assume that traffic information is shared uniformly across the entire system or is centrally aggregated. In contrast, this study explicitly treats the spatial range of information sharing via V2V communication as a design variable and examines how the scale of information sharing affects route choice behaviour and network-level traffic conditions. The contribution of this study does not lie in pursuing optimisation under full information, but rather in clarifying—under simplified conditions—a system-level mechanism through which information heterogeneity induced by limiting the communication range can mitigate inefficient traffic concentration.

The reference point adopted in this study is a traffic system in which route choice is based on homogeneous traffic information shared across the entire system. This setting corresponds to Wardrop’s user equilibrium and represents an assumption implicitly adopted in many centralised eco-routing and navigation approaches. In contrast to this reference regime, we consider scenarios in which information availability is spatially constrained by limiting the communication range between CAVs, thereby inducing heterogeneity in accessible traffic information. We then examine how such information heterogeneity affects route choice behaviour, traffic flow distribution, and CO2 emissions. Through this comparative framework, the study seeks to explicitly disentangle the system-level effects arising from the design of information-sharing ranges.

In particular, drawing on existing insights from the literature traffic paradoxes, this study adopts the perspective that wider information sharing does not necessarily lead to greater traffic efficiency, and therefore deliberately considers the limitation of the information-sharing range. Although individual vehicles make selfish route choices, simulation results illustrate that the aggregation of decentralised decisions based on local information can, at the network level, mitigate inefficient traffic concentration and potentially improve overall system performance.

In this study, CO2 emissions are adopted as a metric to evaluate traffic flow, and the magnitude of the expected impact was investigated using local information. Although the Value of Time (VoT) is often employed as an evaluation indicator in traffic studies, recent studies have increasingly focused on greenhouse gas (GHG) and SO2 emissions in light of growing concerns over global warming [8]. CO2 emissions are influenced not only by travel distance but also by vehicle speed, and it is well established that emissions tend to increase particularly under low-speed driving conditions. For this reason, CO2 emissions are positioned in this study as a proxy indicator reflecting the efficiency of traffic flow and the degree of congestion. However, the CO2 emissions considered in this study are derived from a simplified emissions proxy based on average travel speed and do not represent absolute emission levels or predictive estimates of real-world emissions. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted as relative comparisons obtained under the adopted average-speed-based emissions proxy, rather than as absolute or predictive estimates of real-world emissions.

The contributions of this study can be summarised as follows.

- (1)

- It explicitly elucidates, as a system-level mechanism, how non-cooperative route choice based on local traffic information obtained through V2V communication influences traffic flow.

- (2)

- It introduces the spatial extent of traffic information shared among CAVs as an explicit design variable and examines how constraints on this information-sharing range affect traffic flow efficiency and CO2 emissions.

A distinctive feature of this study is that the observed effects are interpreted as systematic deviations from Wardrop’s user equilibrium under conditions of spatially constrained information. While existing studies [9,10] have focused on the penetration rate of CAVs under mixed traffic conditions involving both conventional vehicles and CAVs, they do not extend to the design dimension of the spatial range over which traffic information is shared. Rather than pursuing traffic flow optimisation through coordinated vehicle control (the first-best outcome), this study highlights the potential for a second-best form of traffic flow optimisation, in which non-cooperative vehicle decision-making, mediated by the locality of information, gives rise to swarm-intelligence-driven improvements in traffic flow.

It should be noted that this study does not propose a new routing algorithm or a novel theoretical traffic model; rather, it constitutes a conceptual exploration that focuses on how differences in information structures influence the behaviour of the traffic system as a whole. Accordingly, the results of this study should be interpreted within the boundary conditions defined by the adopted simulation framework, including simplified driving behaviour, idealised communication conditions, and an average-speed-based emissions proxy.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature from the perspectives of the environmental impacts of CAVs, microscopic traffic models and multi-agent simulation, as well as local information, swarm intelligence, and traffic paradoxes. Section 3 describes the traffic flow simulation model used in the study. Section 4 presents the simulation results and analyses the effects of communication range and CAV penetration rate on CO2 emissions. Section 5 organises the key findings of this study from a theoretical perspective and discusses their interpretation. Finally, Section 6 summarises the conclusions of this paper and outlines its limitations as well as directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Impacts of CAVs: Eco-Routing and Dynamic Traffic Control

CAVs have been widely studied for their potential to reduce energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions through improved traffic efficiency. A substantial body of literature has examined eco-routing and dynamic route guidance strategies that leverage connectivity and automation to smooth traffic flow and mitigate congestion. These studies generally report reductions in fuel consumption and emissions by avoiding stop-and-go traffic and redistributing demand across the network.

Several studies have quantified the environmental benefits of cooperative or connected vehicle control. For example, ref. [5] demonstrated that cooperative adaptive cruise control can reduce CO2 emissions by approximately 10–19%, while ref. [11] reported energy savings ranging from 3% to 20% under various connected and automated vehicle scenarios. Furthermore, ref. [4] showed that integrated eco-routing and traffic control strategies can significantly reduce emissions at the network level.

However, these benefits often rely on centralised or highly coordinated control architectures, which require extensive communication and computation. As the number of communicating vehicles increases, the design and scalability of such systems become increasingly complex. Ref. [12] argued that full communication with all surrounding vehicles is not always optimal and showed that, under certain conditions, feedback from only a limited number of upstream vehicles is sufficient. Nevertheless, their analysis was conducted on a simplified one-lane linear roadway, leaving open questions regarding the applicability of such findings to large-scale and complex urban networks.

This highlights the need for further investigation into decentralised and scalable information-sharing strategies that can achieve environmental benefits without relying on centralised control.

2.2. Agent-Based and Microscopic Traffic Simulation for CAV Studies

Microscopic traffic modelling has a long tradition in transportation engineering, with well-established frameworks such as cellular automata models [13], car-following models [14], and lane-changing models [15]. These models provide detailed representations of vehicle-level interactions and have been widely used to analyse congestion dynamics and traffic control strategies.

With the development of Intelligent Transportation Systems, agent-based and multi-agent simulation (MAS) frameworks have become central tools for studying CAV deployment scenarios, particularly in mixed traffic environments where CAVs and conventional vehicles coexist. MAS enables researchers to capture heterogeneous behaviours and decentralised decision-making processes, thereby allowing the simultaneous evaluation of traffic performance and environmental outcomes.

The idea of constructing vehicle-to-vehicle communication networks through wireless communication has been explored by [16,17], and more recently by [18]. While these studies discuss communication architectures and information dissemination mechanisms, they largely stop short of quantitatively evaluating the extent to which such communication improves traffic efficiency at the network level.

Other studies have sought to assess the effects of connected or automated vehicles on traffic flow using simulation-based approaches. For example, refs. [19,20] conducted simulation analyses of CAV-related traffic control strategies. However, their models were implemented on grid-based hypothetical cities or simplified linear road networks. As a result, the impact of CAV information sharing in realistic, large-scale urban road networks remains insufficiently explored.

In particular, few studies explicitly treat the communication range of CAVs as a key design parameter. Most simulation-based studies implicitly assume idealised or global information sharing, thereby overlooking the system-level implications of limited and local information exchange.

2.3. Local Information, Swarm Intelligence, and Traffic Paradoxes

The provision of information in transportation networks has long been associated with paradoxical outcomes. Braess’s paradox [21,22] demonstrates that adding a new road to a network can degrade overall performance, while empirical evidence also shows that temporary road closures can improve traffic flow [23]. These findings underscore that increasing capacity or information does not necessarily lead to improved system-wide outcomes.

Similar paradoxical effects have been observed in the context of connected and automated vehicles. For example, ref. [10] showed that a 100% penetration rate of CAVs can increase the frequency and severity of urban NO2 hotspots, suggesting that full connectivity may amplify congestion in certain areas. From a theoretical perspective, ref. [24] demonstrated that selfish route choice can lead to a Nash equilibrium that wastes up to 30% more travel time than the social optimum, a phenomenon closely related to the concept of the price of anarchy [25].

Insights from swarm intelligence and self-organising systems further help to explain these phenomena. Classical models such as Schelling’s segregation model [26] and Reynolds’s Boids model [27] illustrate how simple local decision rules can generate complex, and sometimes inefficient, collective patterns. In transportation contexts, when many drivers or vehicles respond uniformly to the same information, traffic demand may become excessively concentrated on particular routes, thereby creating new bottlenecks.

Related findings have also been reported outside transportation systems. For instance, ref. [28] showed that providing real-time waiting-time information to all visitors in a theme park can reduce overall utility under saturated conditions, whereas constraining information or prescribing visitation sequences can improve system performance. Taken together, these studies suggest that information heterogeneity and local decision-making can play a critical role in mitigating congestion.

Despite this rich theoretical background, relatively few studies have examined how the spatial range of information sharing influences the emergence or avoidance of traffic paradoxes. This study addresses this gap by analysing how limiting the communication range among CAVs can induce heterogeneous perceptions of traffic conditions, thereby leading to emergent and more efficient traffic distributions without centralised control.

In this study, the concept of swarm intelligence is not introduced as a new theoretical model; rather, it is employed as an interpretative framework to explain how decentralised and selfish route choices based on local information can, in aggregate, give rise to emergent traffic patterns at the system level. In particular, restricting the communication range among CAVs generates heterogeneity in accessible information, which can act as a mechanism to prevent excessive information homogenisation and convergence towards inefficient user equilibria.

2.4. Research Gaps and Design Motivation

Based on the foregoing literature, the most critical limitation of existing approaches to traffic information sharing using CAVs lies in the implicit assumption that communication and information sharing are conducted in a global and idealised manner, despite the absence of explicit design criteria regarding their spatial scale. While centralised or highly coordinated control can, in theory, achieve high levels of efficiency, such approaches entail structural challenges, including increasing computational burdens and scalability issues as the number of communicating vehicles grows, as well as the potential emergence of traffic paradoxes resulting from excessive information homogenisation. Nevertheless, the fundamental design question of how much information sharing is desirable has not been sufficiently examined.

Addressing this gap, the present study explicitly introduces the communication range among CAVs as a design parameter and systematically investigates how the spatial scale of information sharing affects traffic flow and environmental impacts. Rather than proposing optimal routing algorithms or centralised control schemes, the proposed approach aims to elucidate how decentralised decision-making under conditions of limited and local information sharing gives rise to system-level traffic dynamics.

In this way, the study redefines the range of information sharing, which has been implicitly fixed in prior research, as a variable design element, and explores the potential for traffic information design that does not rely on centralised control or complete information homogenisation.

3. Traffic Flow Simulation Model

This study employs a MAS framework to analyse traffic flow. In this section, we describe the behavioural rules governing the vehicle agents used in the simulation and the estimation formula for CO2 emissions.

3.1. Driving Rules of Vehicle Agents

The behavioural rule for each vehicle agent can be simply described as driving in a manner that avoids collisions with the vehicle ahead. To achieve this, each agent adjusts its driving speed so as to maintain a sufficient distance from the preceding vehicle.

At time t, each vehicle agent has the following parameters: the distance to the vehicle ahead dt, the current speed vt, the acceleration a, and the maximum speed vmax. If there is no risk of collision with the vehicle in front when travelling at the current speed (i.e., the minimum safe distance dmin is maintained), the position change per unit time Δt (one step in the simulation) is determined by the current speed vt, and the change in speed per unit time Δt is determined by the acceleration a. Therefore, the travel distance Δdt of the vehicle agent from time t to time t + 1 is given as “vtΔt + aΔt2” by the equation for uniformly accelerated motion. However, if “vtΔt + aΔt2” exceeds the distance covered at the maximum speed vmax, then Δdt = vmaxΔt.

If it appears that the vehicle cannot maintain a safe distance (minimum distance dmin) from the vehicle ahead when continuing to travel at the current speed, the travel distance Δdt for the next step will be adjusted to . This is referred to as “applying the brakes.” The condition for applying the brakes can be summarized as follows: . Thus, the travel distance of the vehicle agent from time t to time t + 1 can be written as follows:

The car-following rules adopted in this study can be situated within the tradition of widely used car-following models in the literature on microscopic simulations of CAVs. The framework in which vehicle agents update their driving behaviour based on the distance to the leading vehicle, relative speed, and acceleration is shared with representative continuous-time models such as the Intelligent Driver Model (IDM) [15], as well as Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) and Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control (CACC) models developed in the context of conventional automated driving technologies [29,30].

In addition, the discrete-time update rule employed in this study belongs to the lineage of microscopic traffic flow models, including the Gipps model [14] and cellular automaton-based models [13], which share a fundamental structure of speed and distance adjustment designed to ensure stability and safety in car-following behaviour. Building on this tradition, vehicle agents in the present study update their subsequent movement distance using the relative distance to the leading vehicle, , and the current speed, , while maintaining a safe following distance. Accordingly, the proposed approach is consistent with the core principles underlying IDM and ACC—namely, the maintenance of safe headways and continuous speed adjustment—while reformulating these principles within a discrete-time modelling framework that explicitly incorporates information-sharing mechanisms specific to CAVs.

However, although the network used in this study consists of multiple links and nodes, several traffic-specific elements inherent to real-world conditions—such as intersection behaviour, signal control, lane-changing manoeuvres, and heterogeneity in road capacity—are not explicitly modelled. Similarly, the proposed car-following model simplifies a number of important microscopic factors commonly considered in integrated traffic flow models, including driver reaction times, heterogeneity in driver and vehicle characteristics, and individual differences in acceleration and deceleration behaviour. While these factors are well known to influence traffic flow stability and congestion formation, this study intentionally minimises model complexity in order to isolate and examine the effects of information sharing among CAVs on traffic dynamics.

Nevertheless, incorporating these elements is essential for achieving more realistic representations of traffic flow and for conducting more precise evaluations of the impacts of CAV deployment. Future research should therefore develop higher-fidelity microscopic models that integrate intersection dynamics, signal control, lane-changing behaviour, reaction-time distributions, and vehicle performance heterogeneity, and examine how these factors interact with the information-sharing mechanisms analysed in this study.

3.2. Route Selection of Vehicle Agents

Throughout this paper, vehicles equipped with V2V communication functionalities are referred to as connected vehicles. Previous research has shown that information exchange between vehicles can help to avoid collisions and enable efficient control of autonomous driving [31]. When such information exchange is further utilised for route selection, overall traffic flow efficiency can be improved. In the simulation, vehicle agents tend to select routes that allow them to travel from their origins to their destinations in the shortest possible time. In this context, a key difference arises between conventional vehicles and connected autonomous vehicles (CAVs) in terms of the traffic congestion information available to them (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Availability of traffic information by car type.

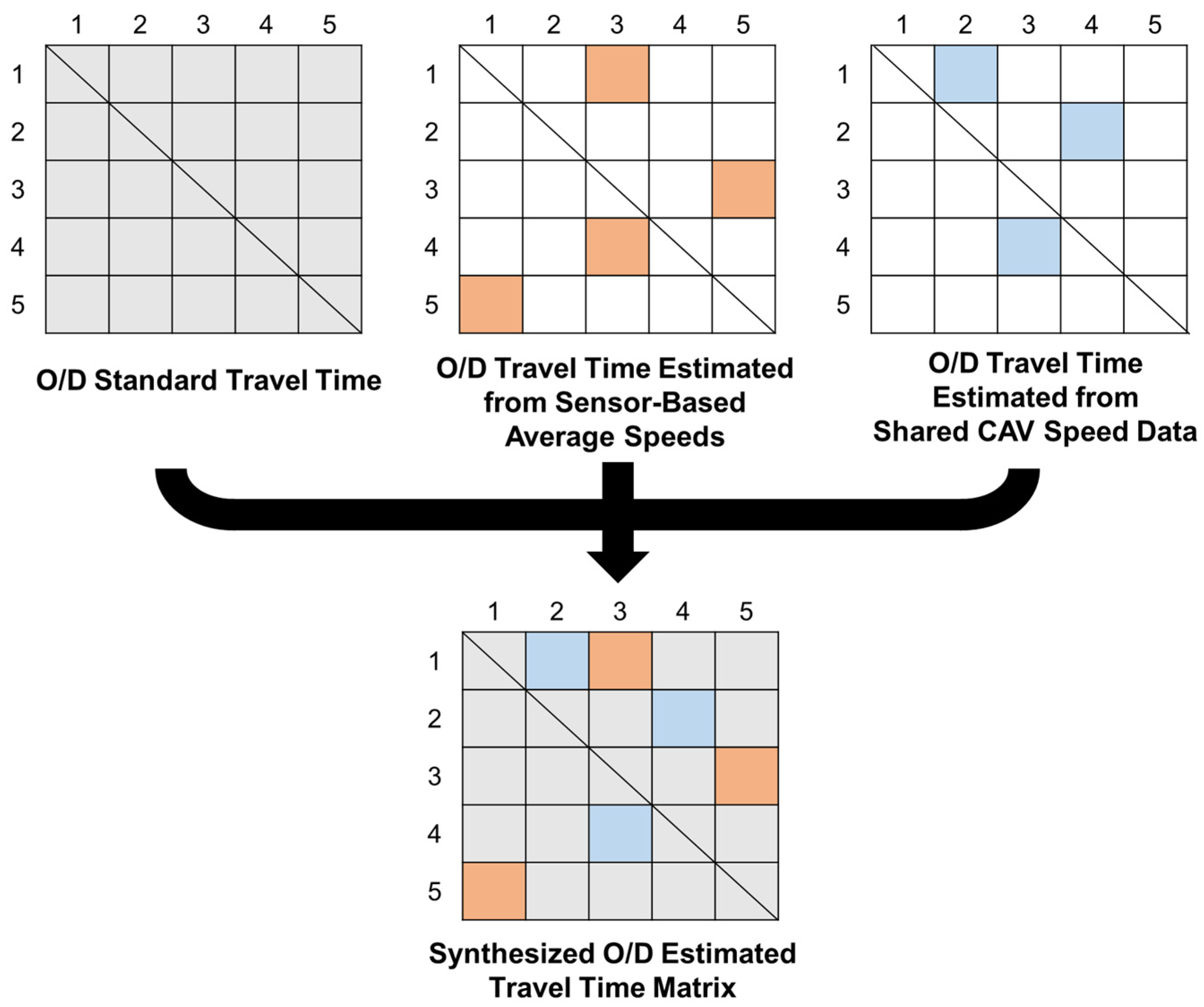

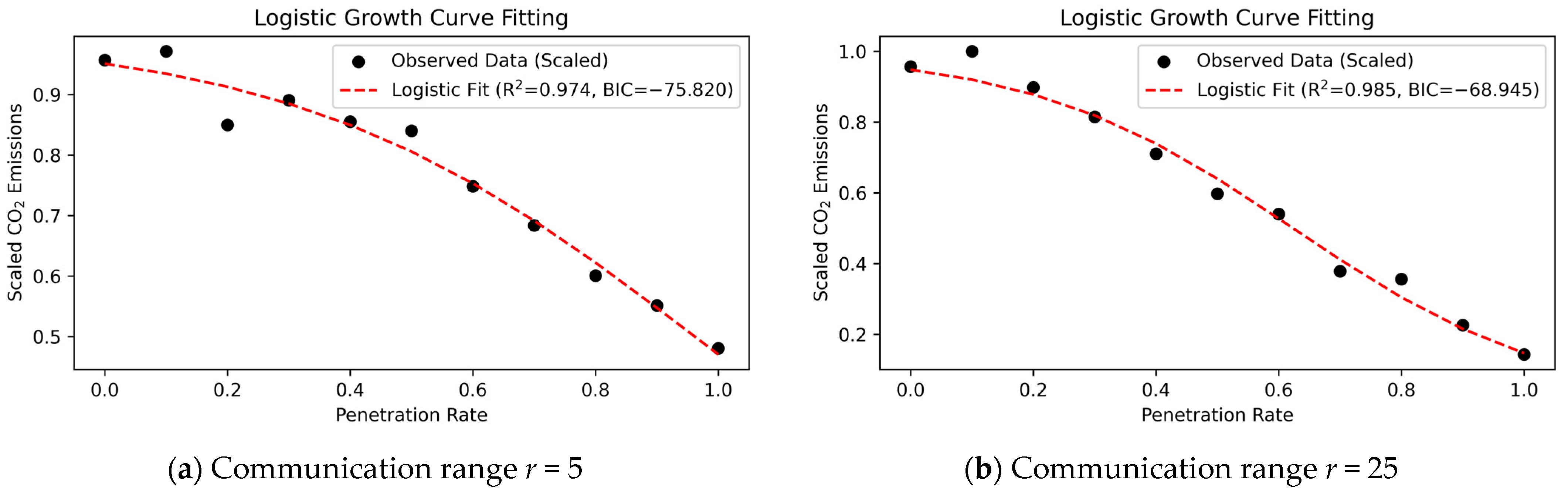

From the perspective of a conventional vehicle, two types of information are available: the standard travel time between points (road segments), and the travel time calculated from the average speed collected by traffic speed sensors. In addition to the information available to conventional vehicles, a CAV can obtain the driving speeds of nearby CAVs through local communication. The priorities of these types of information are as follows: (1) the O/D (Origin–Destination) travel time estimated from shared CAV speed data; (2) O/D travel time estimated from sensor-based average speeds; and (3) O/D standard travel time. Based on this prioritisation, the information used for the route choice is updated accordingly. Consequently, the information used by a CAV for route selection follows the synthesized O/D estimated travel time matrix shown in Figure 1. The standard travel time refers to the time required when there is no congestion, representing the theoretical shortest travel time. When no other information is available, routes are selected based only on the standard travel time.

Figure 1.

Estimated travel time for route selection. Schematic representation of the integration of multiple O/D travel time sources. Gray cells represent standard O/D travel times, orange cells indicate travel times estimated from sensor-based average speeds, and light blue cells denote travel times estimated from shared CAV speed data. The lower panel shows the synthesized O/D travel time matrix.

In the simulation, one time step corresponds to three seconds in real time. Information obtained from speed sensors installed on each link is updated at every time step and is therefore used as discretely updated traffic information at three-second intervals, spatially aggregated at the link level in the form of average travel speeds.

In contrast, local communication information shared among CAVs is characterised by being acquired and updated in real time at the moment when route selection is performed. Because CAVs immediately reflect the most recent speed data received from neighbouring CAVs within their communication range, this information source is spatially more localised while being temporally more frequent and instantaneous than the speed-sensor information available to conventional vehicles.

Accordingly, the route choice information employed in this study has a two-layer structure: (1) sensor-based information, consisting of link-level average speeds updated every three seconds (temporally coarse and spatially extensive), and (2) CAV-shared information, consisting of instantaneously updated data obtained from nearby CAVs (temporally fine-grained and spatially localised). By integrating these two information layers, an estimated travel-time matrix is constructed and used for route selection.

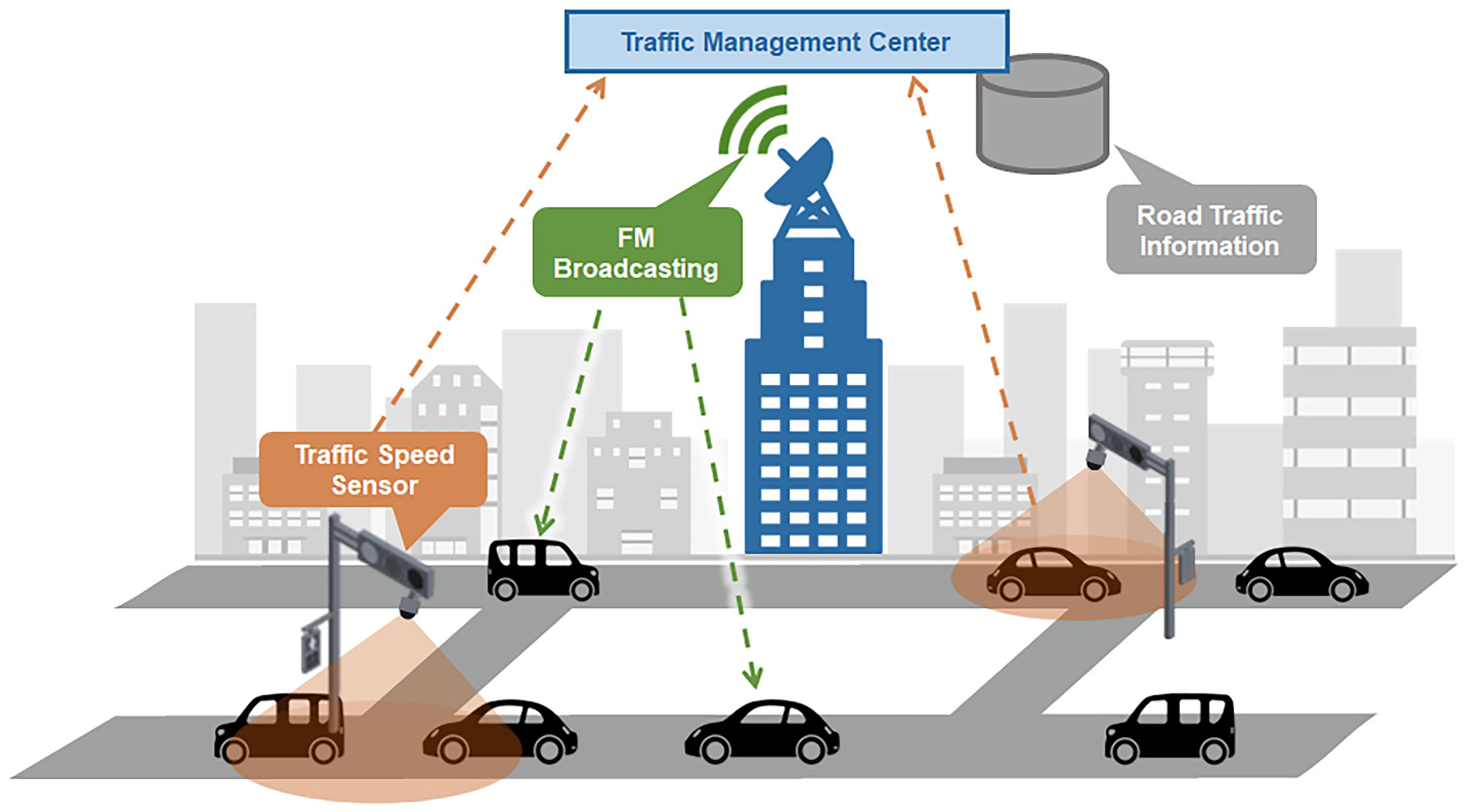

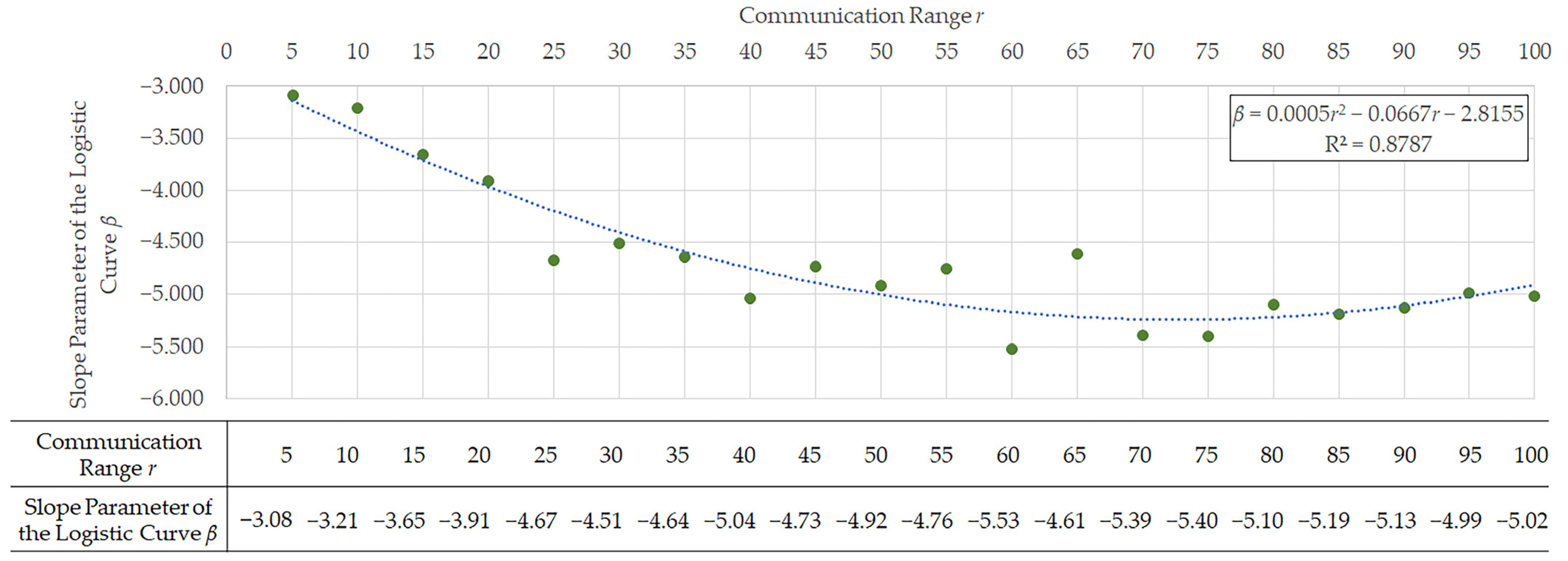

Information from traffic speed sensors is comparable to that provided by a conventional car navigation system. Driving speed data collected by traffic speed sensors installed at locations such as traffic signals are first aggregated at a traffic management centre and then transmitted to individual vehicles. Using this congestion information, each vehicle estimates the shortest expected travel time and select its route accordingly. The specific mechanisms of car navigation systems vary across countries, with the Japanese system illustrated in Figure 2. In this system, data collected by traffic speed sensors are sent to a traffic management centre and transmitted to the vehicle via FM broadcasting.

Figure 2.

Overview of car navigation system.

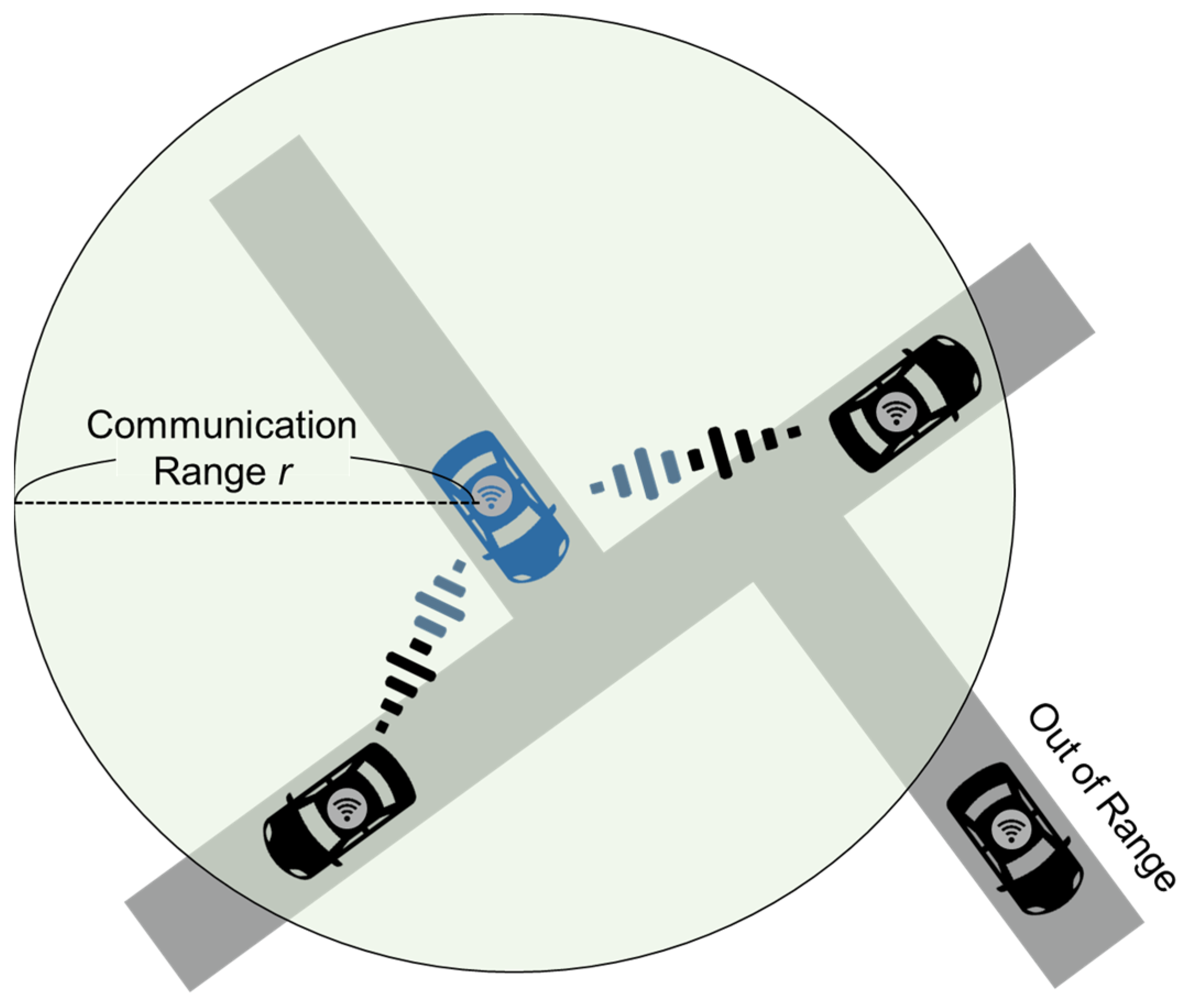

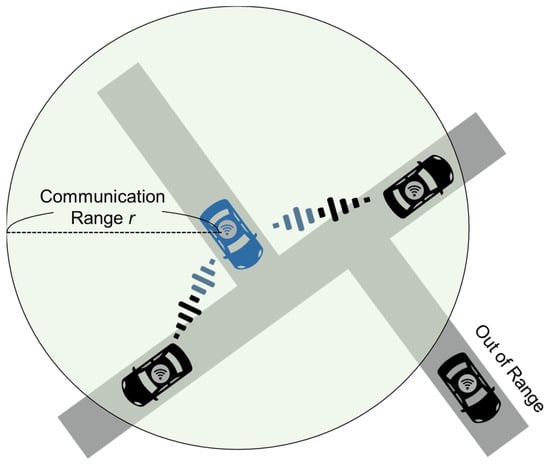

Information exchange between CAVs is assumed to occur through limited-range wireless communication (Figure 3). Various methods for V2V communication have been proposed, including systems using LED transmitters and camera receivers [32], the 5 GHz spectrum [33,34], and communication technologies such as Wi-Fi, DSRC, and LTE [35]. The present study does not consider which specific communication system is used, instead focusing on the exchange of information between nearby CAVs. The underlying concept is straightforward: if another CAV is within communication range, information exchange occurs. The information shared between CAVs pertains to the congestion on the current road. Specifically, a CAV receives the average speed data on the road from its entrance to its current position, as experienced by other CAVs, and uses these data to estimate the time required to pass through the road. This enables real-time route selection based on up-to-date information, thereby facilitating quicker avoidance of traffic congestion. When multiple CAVs are present on the same road segment, the average speeds received from those vehicles are averaged and used for estimation.

Figure 3.

Information sharing between CAVs.

The communication model adopted in this study is designed to clearly distinguish between elements that reflect real-world traffic information systems and those that are deliberately stylised to clarify the analytical focus. The former include information acquisition and sharing processes that exist in actual ITS technologies, such as the observation of link-level average speeds via traffic sensors and the wide-area broadcasting of aggregated traffic information. The latter comprise idealised assumptions introduced purely for modelling simplicity, including the absence of communication delays or observation errors and the assumption that information exchange among CAVs is always perfectly reliable.

This study can be positioned as an attempt to intentionally deviate from Nash equilibrium and the associated concept of the Price of Anarchy by introducing information heterogeneity arising from limited communication ranges. Unlike Wardrop’s user equilibrium [36], which assumes perfect and system-wide information, restrictions on communication range render the available information set incomplete, preventing drivers from fully perceiving the congestion structure of the entire network. Under such imperfect information, route choice behaviour may result in higher social costs than equilibria under full information, as demonstrated by [25], implying that equilibrium properties and system performance can vary depending on communication conditions.

Moreover, the effects of information provision range, reliability, and update frequency on network equilibria have been extensively examined in the literature, including studies by [37,38]. The communication-range constraints analysed in this study are therefore consistent with a broad body of research on traffic information provision and route choice under imperfect information, and they provide an important perspective for understanding how partial information sharing among CAVs influences equilibrium deviation and variations in social cost.

3.3. Estimation Formula for CO2 Emissions

CO2 emissions in this study are estimated using the speed-dependent polynomial function proposed by [39]. This approach has been widely adopted in traffic flow analysis and emissions modelling because it provides a concise representation of the nonlinear relationship between vehicle speed and emissions [6,40]. While maintaining consistency with these existing studies, this paper assumes that all vehicle agents share identical fuel efficiency in order to isolate and purely evaluate the effects of local information sharing. This simplification eliminates noise arising from differences in vehicle type and fuel economy, thereby allowing the impacts of the information-sharing mechanism—the primary focus of this study—to be examined more clearly. In this study, CO2 emissions are estimated based on link-level average travel speeds in order to evaluate the effects of local traffic information sharing on traffic flow and emissions. Specifically, following [39], the amount of CO2 emitted by an individual vehicle c was estimated based on the average driving speed on the road.

We converted the values of parameters b0–b4 using a unit conversion of 1 mi = 1.60934 km (see Table 2). In the simulation, every time a vehicle agent reached the endpoint of a road, the CO2 emissions (g/km) were calculated based on the average speed (km/h) at which the vehicle was travelling.

Table 2.

Parameters for estimating CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, emission estimation based on average travel speed involves several important limitations. In real-world urban traffic, signal control and frequent stopping and re-acceleration at intersections occur regularly, and emissions are known to depend strongly on instantaneous speed and acceleration fluctuations. Consequently, models that rely solely on average speed may underestimate or overestimate emissions, particularly under driving conditions characterised by frequent stops and acceleration–deceleration cycles. The emission model employed in this study likewise does not explicitly capture such microscopic driving behaviours.

In addition, the polynomial emission function proposed by [39] was estimated using empirical driving data within a speed range of approximately 5–65 miles per hour (8–105 km/h). In this study, the maximum vehicle speed is capped at 60 km/h, and therefore no issues arise in the high-speed regime; however, in the low-speed range below 8 km/h, the estimated emission values may involve non-negligible errors.

Furthermore, this study assumes that all vehicle agents have identical fuel efficiency. This assumption constitutes a technical simplification intended to enhance model transparency and reduce computational burden, while simultaneously eliminating the influence of vehicle-type heterogeneity and technological differences. By doing so, the analysis enables a consistent and comparable evaluation of how factors such as traffic information sharing and communication range affect emissions. At the same time, this assumption limits the ability of the model to provide quantitative assessments of absolute emission levels or to capture effects arising from variations in vehicle composition.

Accordingly, the CO2 emissions estimated in this study do not aim to precisely reproduce actual urban traffic emissions. Rather, they should be interpreted as an indicator for capturing the relative trends in how design factors—specifically, the penetration rate of CAVs and the spatial range of traffic information sharing—affect emissions through changes in average travel speed. As demonstrated by comprehensive emission modelling frameworks such as COPERT [41] and MOVES [42], practical emission assessment and policy analysis require detailed models that account for acceleration behaviour, vehicle fleet composition, and intersection control. Incorporating such elements therefore remains an important direction for future research.

4. Simulation

4.1. Settings

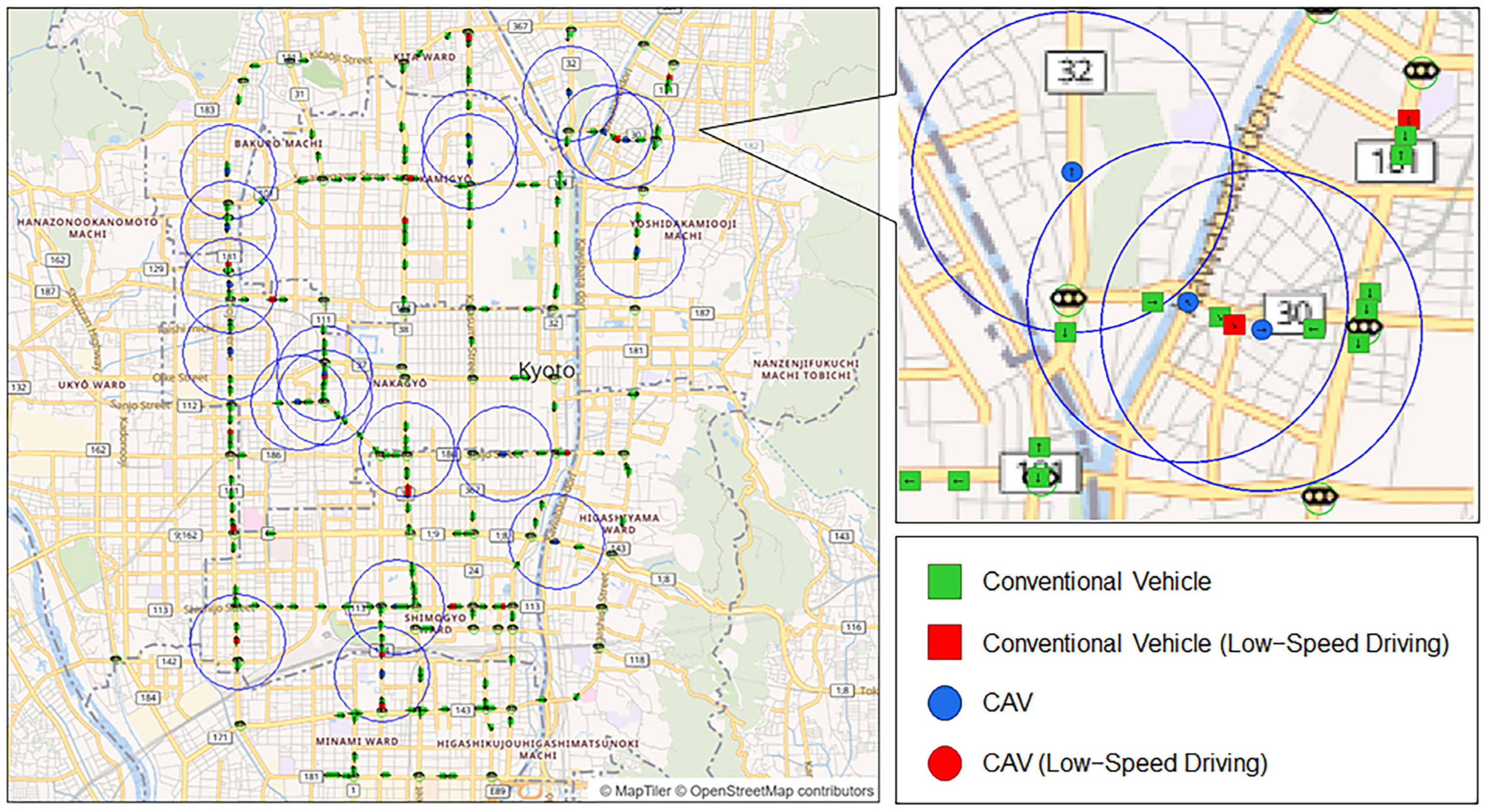

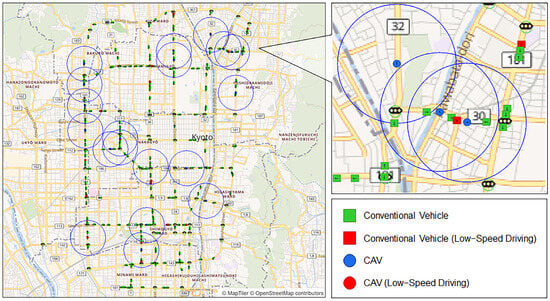

The simulation was conducted using Kyoto City as an example of a real urban environment. The simulation used artisoc, a platform for multi-agent simulation developed by [43]. The simulation interface is shown in Figure 4. Vehicle agent markers and colours distinguish between conventional vehicles and CAVs, and also indicate low-speed driving conditions. The communication range of each CAV is indicated by a blue circle.

Figure 4.

Visual output of the simulation. Visual output of the simulation. Square markers represent conventional vehicles, while circular markers denote CAVs. Red markers indicate vehicles in a low-speed driving state. The communication range of each CAV is illustrated by a blue circle. Green circles around traffic signals represent the information acquisition range of traffic speed sensors. Arrows on the markers indicate the direction of vehicle movement.

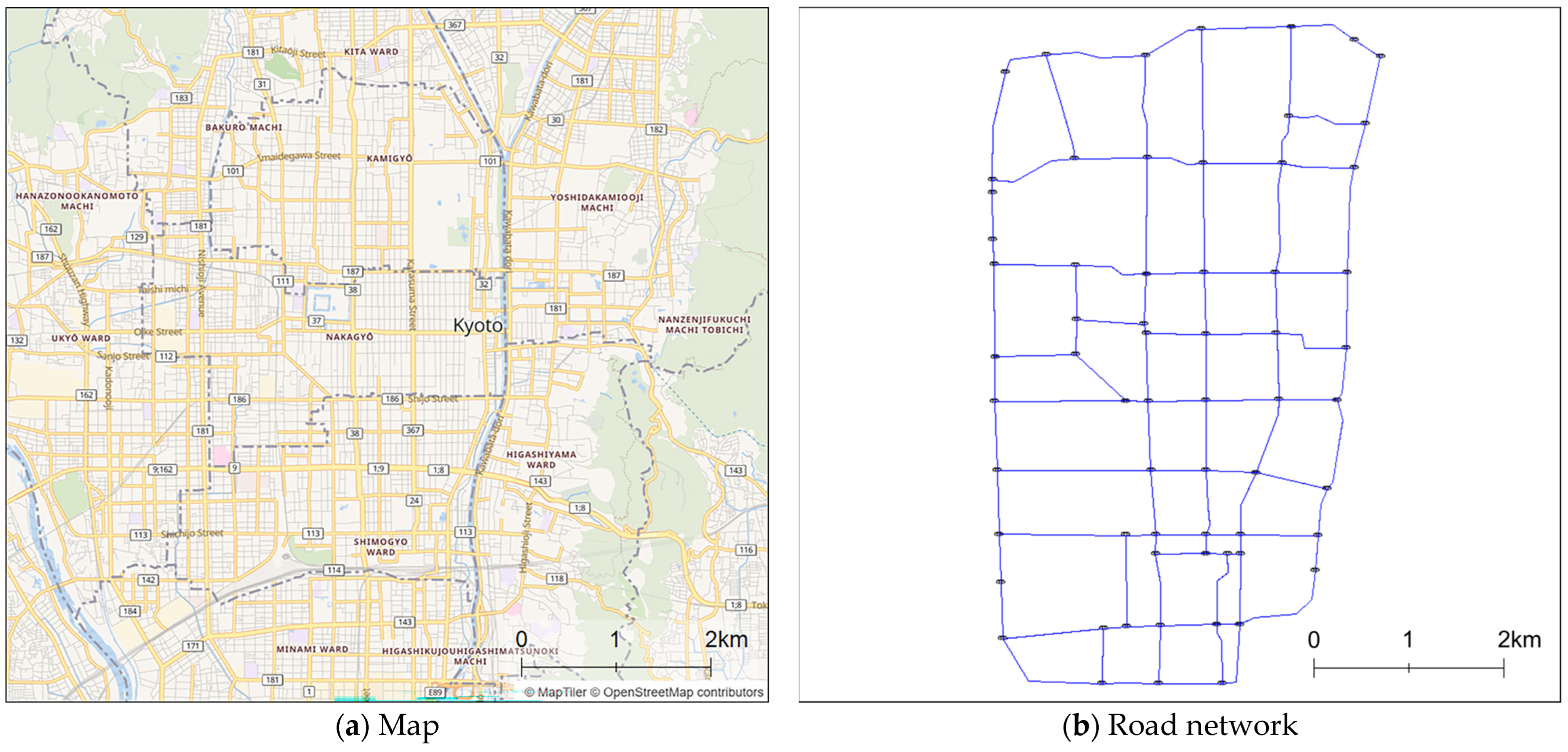

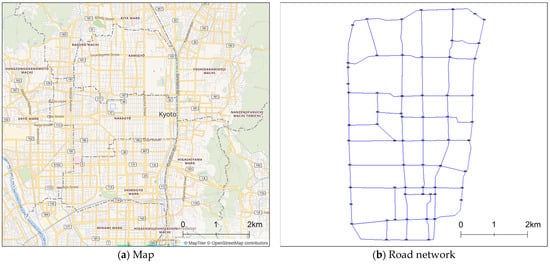

In the simulation, we used a road network extracted from national highways (trunk), major prefectural roads (primary), and general prefectural roads (secondary) in Kyoto (Figure 5). All of these are major roads that carry high traffic volumes and form the structural backbone of urban traffic within the study area (note that motorways are not included in the target region). In contrast, this study omits municipal roads (classified as tertiary and unclassified) from the model, which constitutes an important simplification that may affect congestion patterns and route choice behaviour. In particular, excluding fine-grained street networks may lead to an underestimation of drivers’ detour behaviour and the mechanisms underlying localised congestion. The results of this study should therefore be interpreted as an analysis focused primarily on major roads. The road network in Kyoto comprises 112 points (nodes) and 152 roads (links).

Figure 5.

Road network of Kyoto. Panel (a) shows the reference map of the study area, while panel (b) illustrates the simplified road network used in the simulation, including road segments and speed sensor locations.

The parameters governing the driving behaviours of vehicle agents were set as follows: maximum speed vmax = 1, acceleration a = 0.334, and minimum safe distance dmin = . The maximum speed is normalised to 1, which corresponds to 60 km/h. Given that one simulation step represents 3 seconds in real time, an acceleration value of 0.334 corresponds to approximately 1.86 m/s2, which is comparable to typical passenger vehicle acceleration performance (1.5–3.0 m/s2). As a result, the safe following distance varies with driving speed, and when travelling at the maximum speed, the safe distance corresponds to 27.75 m. In addition, because the maximum standard travel time was 248, data collection was initiated after 250 steps and terminated once 3000 vehicles had reached their destinations. Although a larger number of vehicles reaching their destinations would improve the statistical stability of the simulation results, the number was set to 3000 considering the trade-off with computational time.

In the simulation, the communication range of the CAVs was varied in increments of 10 from a radius of 10 to 100, and the penetration rate of the CAVs (generation ratio) was varied in increments of 5% from 0% to 100%. A penetration rate of 0% represents a scenario in which the vehicle agents are conventional vehicles, whereas a penetration rate of 100% corresponds to a scenario in which all agents are connected.

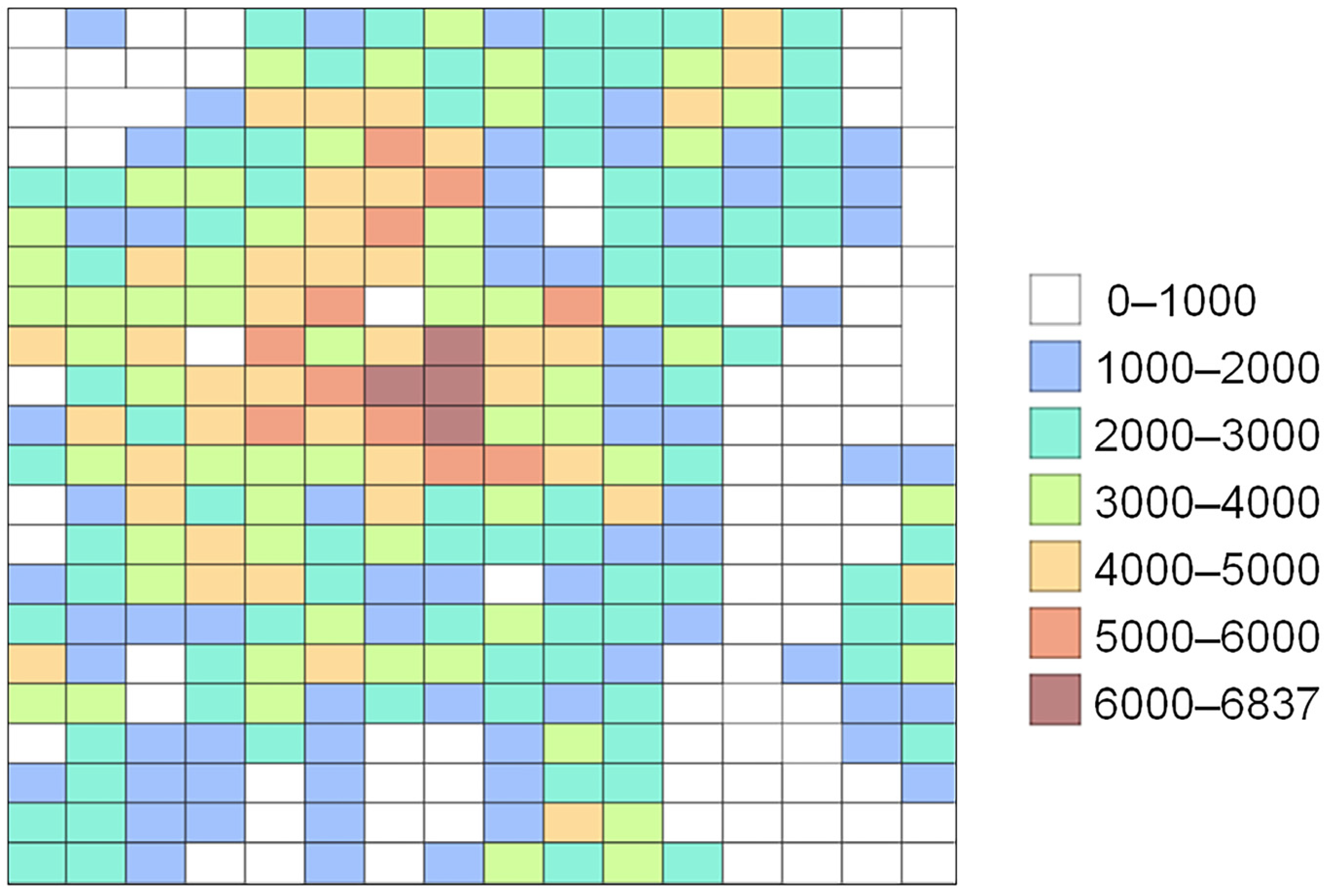

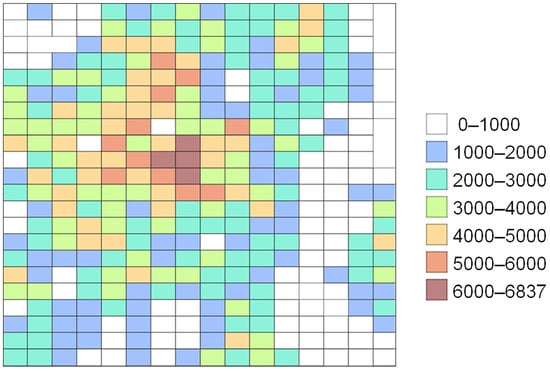

The generation probability of vehicle agents is determined by the population assigned to each road endpoint (node). It is assumed that nodes associated with larger populations generate vehicle departures more frequently. The population assigned to each node was based on the “500-m Mesh Estimated Future Population Data (FY2018 National Government Office Estimate)” obtained from [44]. Figure 6 presents a colour-coded map of population density, in which warmer colours represent areas with higher population levels, while cooler colours indicate areas with lower population levels. The population within each mesh block was allocated to the nodes contained within that block, and the population assigned to each node was proportionally determined based on the number of nodes in the mesh.

Figure 6.

500-m mesh population.

The probability that a vehicle agent is generated with node i as its origin is given by:

where δ is a scaling parameter used to adjust the overall traffic volume in the simulation. In the simulation for Kyoto City, δ was set to 0.25 in considering the numbers of nodes and the total number of generated agents.

Similarly, the destinations of the generated vehicle agents were determined probabilistically based on the population. The traffic demand between nodes was determined by the following gravity model, which is based on the population Pi of origin node i, population Pj of destination node j, and the straight-line (Euclidean) distance Lij between the two nodes.

Here, σ1, σ2, and σ3 represent parameters of the gravity model, set as σ1 = 0.5393192, σ2 = 0.3702117, and σ3 = 1.666391, based on estimates from data on Japan’s three major metropolitan areas as reported by [45].

The probability that a vehicle agent generated at the origin node i has node j as its destination is then given by:

It should be noted that the demand generation method employed in this study is not intended to reproduce actual commuting and school travel behaviour, tourist traffic, time-of-day demand variations, or empirically observed congestion patterns in Kyoto City. The parameters of the gravity model are estimated based on data from other metropolitan areas and therefore do not directly reflect Kyoto-specific land-use structures or travel behaviours. As a result, the O/D demand generated by this model may not necessarily coincide with real-world traffic demand or the actual locations of congestion.

In this study, demand generation is positioned as a conceptual experimental setting designed to examine how differences in CAV communication range and information-sharing mechanisms influence route choice and traffic flow distribution. The population-based gravity model is adopted as a parsimonious approximation capable of capturing the global spatial imbalance of O/D demand, rather than for the purpose of quantitatively reproducing real traffic conditions. Accordingly, the results presented below should be interpreted as relative comparisons under common demand conditions, rather than as assessments of the absolute validity of demand levels or congestion locations.

Future research should aim to construct more realistic demand models by incorporating Kyoto-specific O/D survey data or empirically observed mobility data derived from smartphones or GPS, thereby further refining the simulation results.

4.2. Results

Five independent simulation runs were conducted for each parameter setting, and the CO2 reduction rate was calculated based on the mean values, using the CO2 emissions at a CAV penetration rate of 0% as the benchmark. The results (The robustness of the experimental results is discussed in Appendix A and Appendix B) are summarised in Table 3. In Table 3, a colour scale ranging from red to blue is applied according to the magnitude of the CO2 reduction rate, enabling a visual comparison of relative reduction trends. The cell corresponding to the largest reduction—at a penetration rate of 1.0 and a communication range of 75—is highlighted in bold with a white background for reference.

Table 3.

Experimental results.

Table 3 shows that CO2 emissions generally decrease as the penetration rate of CAVs increases. However, when the communication range is small, the emission reduction effect remains limited even at high penetration rates. For example, when the communication range is 5, the CO2 reduction rate remains at approximately 10% at most. Moreover, achieving a CO2 reduction rate exceeding 20% requires a communication range of roughly 30 or greater. Importantly, the maximum reduction does not necessarily occur at the largest communication range, suggesting that the effects of expanding the communication range are nonlinear.

4.3. Two-Way ANOVA

In this section, a two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) is conducted to examine whether the two design parameters—the CAV penetration rate and the communication range—lead to systematic differences in the average level of total CO2 emissions.

The ANOVA employed here is not intended to provide a rigorous estimation of causal effects or a precise quantification of effect sizes. Rather, its purpose is to serve as a supplementary check to determine whether the nonlinear and level-dependent patterns identified through visualisation and curve-fitting analyses in the preceding and subsequent sections can also be detected as consistent differences at the level of mean values.

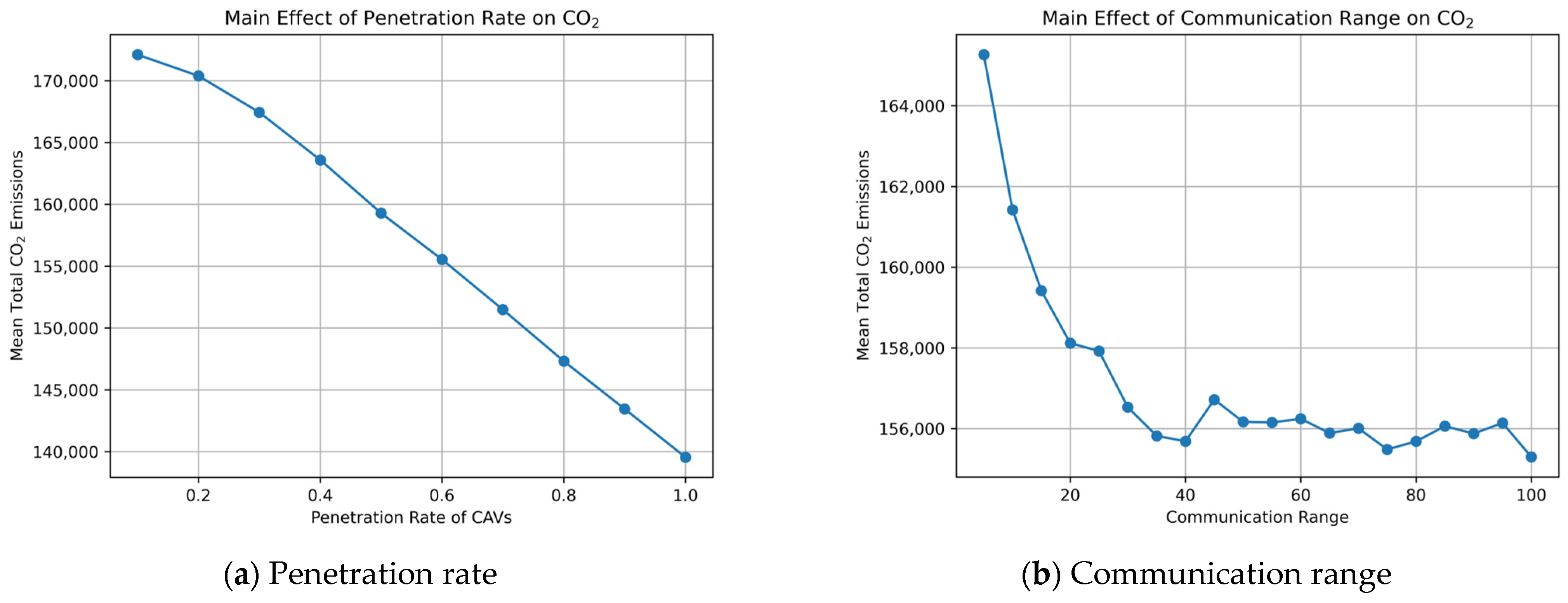

Table 4 presents the results of the two-way ANOVA assessing the effects of CAV penetration rate and communication range on total CO2 emissions. The analysis reveals a very large and statistically significant main effect of the CAV penetration rate (F = 1388.72, p < 0.001), indicating that the average level of CO2 emissions differs substantially across penetration levels. This result suggests that, as the penetration of CAVs increases, the mean emissions level changes in a systematic manner.

Table 4.

Results of Two-Way ANOVA on Total CO2 Emissions.

A statistically significant main effect is also observed for the communication range (F = 32.27, p < 0.001). This finding indicates that, even when averaging across penetration rates, differences in communication distance are associated with consistent changes in the average level of CO2 emissions.

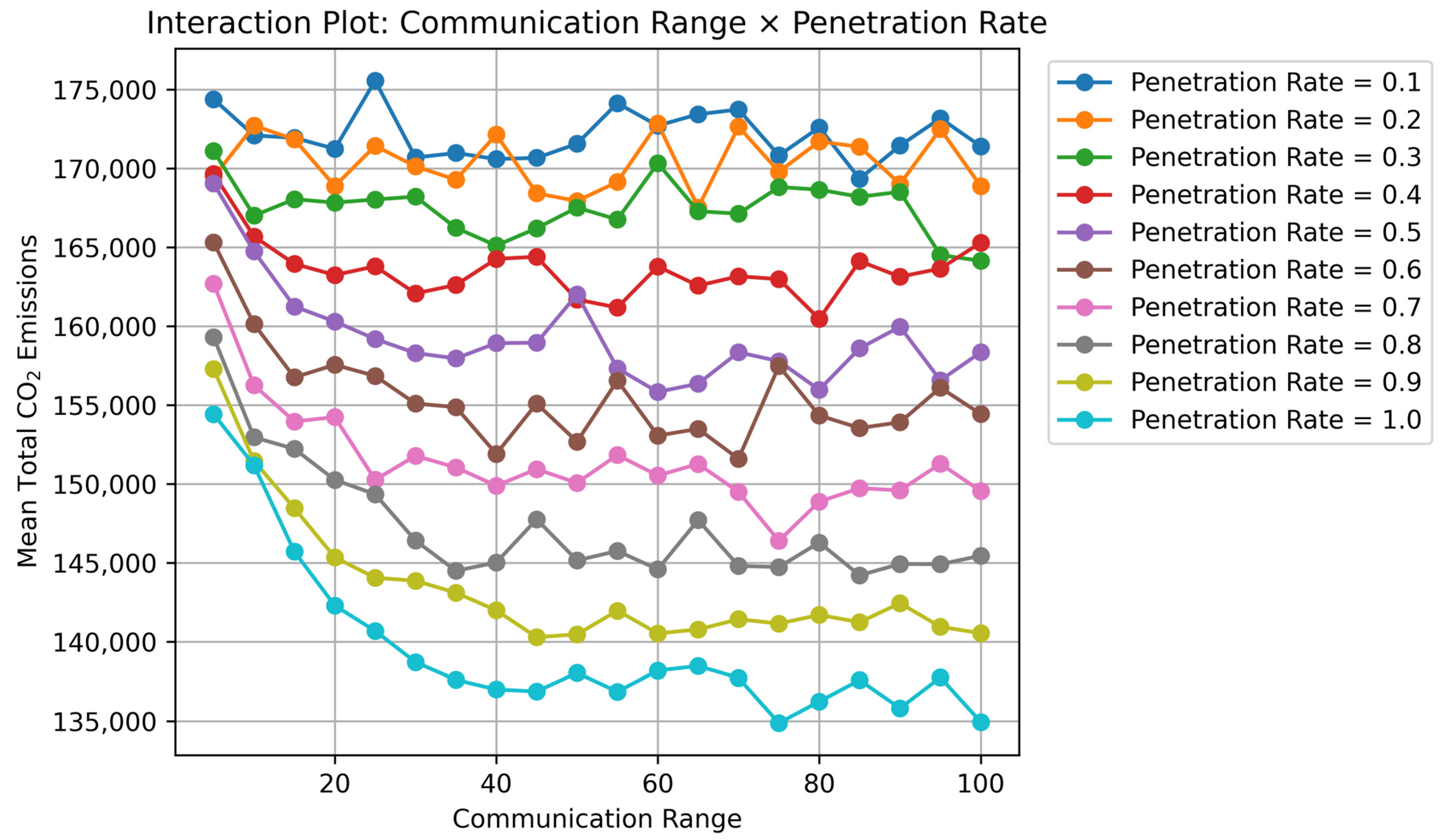

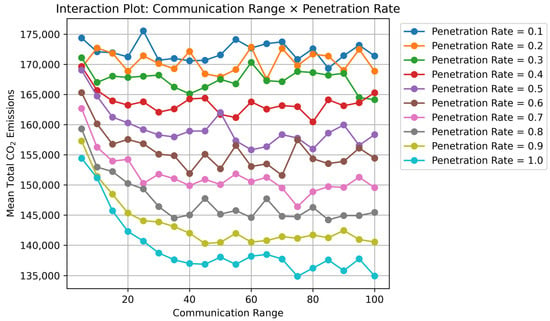

In addition, the interaction term between penetration rate and communication range is statistically significant (F = 2.51, p < 0.001). This result implies that the effect of communication range on CO2 emissions varies depending on the level of CAV penetration, and conversely, that the influence of penetration rate manifests differently across communication conditions.

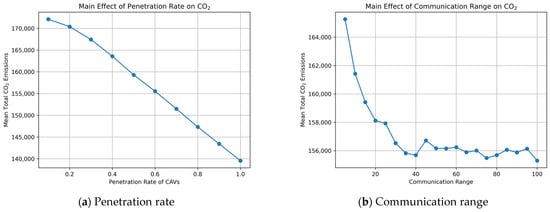

These patterns can also be visually confirmed from the main-effect and interaction plots shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. As illustrated in Figure 7a, total CO2 emissions exhibit an overall decreasing trend as the CAV penetration rate increases. In contrast, the main effect of communication range shown in Figure 7b indicates that the improvement becomes apparent as the range expands from short to medium distances, while changes become more gradual beyond a certain level.

Figure 7.

Main-effect plot of the penetration rate and communication range on total CO2 Emissions.

Figure 8.

Interaction effect plot of the penetration rate and communication range on total CO2 Emissions.

The interaction plot presented in Figure 9 further shows that the effect of communication range varies depending on the level of CAV penetration. Taken together, these results suggest that the influences of communication distance and penetration rate do not operate as simple linear effects, but rather emerge through level-dependent and non-linear structures.

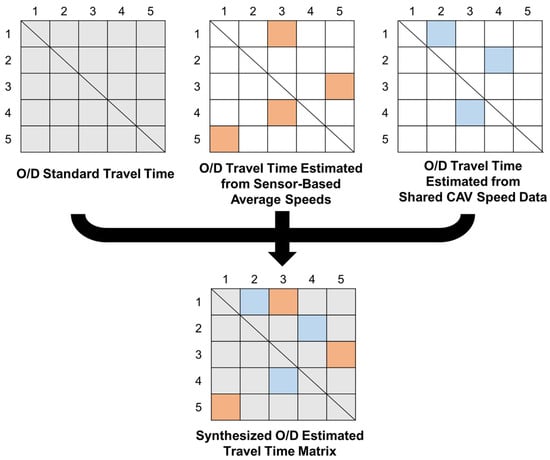

Figure 9.

Logistic curve fittings.

Overall, the results of the two-way ANOVA confirm, at the level of mean values, that both CAV penetration rate and communication range are systematically associated with CO2 emissions. In this sense, the ANOVA serves as a preliminary validation that motivates the subsequent analysis of non-linear change patterns examined in the following section.

4.4. Curve Fitting

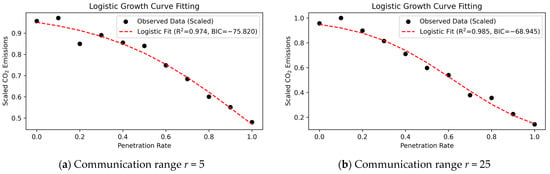

The preceding ANOVA confirmed that there are systematic differences in the mean level of CO2 emissions associated with variations in both the CAV penetration rate and the communication range. In this section, we descriptively examine how these differences manifest as non-linear structures over the process of increasing CAV penetration by applying logistic growth curve fitting (details of the model selection based on comparisons with alternative growth models are provided in Appendix C).

The purpose of the logistic model in this study is not to estimate strict causal relationships or to generate forecasts. Rather, it is employed as a descriptive tool to summarise characteristic patterns in the CO2 emission reduction process—namely the onset, acceleration, and saturation of reduction effects as the CAV penetration rate increases.

Specifically, total CO2 emissions were scaled using Min–Max normalisation based on the minimum value and the maximum value . The scaled total CO2 emissions can be estimated as a function of the CAV penetration rate x using the following equation:

Here, represents the upper asymptote, is a coefficient that controls the slope of the curve, and denotes the inflection point. In this study, because is normalised by its maximum value, is fixed at 1 for estimation.

The logistic growth model is originally used to describe processes such as population growth and technology diffusion; in this study, it is adopted not as a strict causal model but as a descriptive approximation for summarising the pattern of changes in CO2 emissions. Accordingly, the estimated parameters and should not be interpreted as direct measures of the magnitude of emission reduction, but rather as indicators that characterise how rapidly the reduction effect emerges and at what level of CAV penetration the system reaches a turning point.

As shown in Table 5, the coefficient of determination R2 exceeds 0.9 for all communication ranges, indicating that the logistic curves provide a generally good approximation of the simulation results. This suggests that the CO2 reduction effect associated with increasing CAV penetration shares a common nonlinear structure across all communication ranges, characterised by limited effects at low penetration levels, relatively pronounced reductions at intermediate levels, and eventual saturation at higher penetration rates.

Table 5.

Estimated parameters of the logistic growth model.

By contrast, the estimated values of and vary across communication ranges, suggesting that the onset and saturation of the CO2 reduction effect depend on communication conditions. When the relationship between total CO2 emissions and the CAV penetration rate is illustrated graphically, cases with and small |β| exhibit a gradual inverted S-shaped curve (Figure 9a), whereas cases with and large |β| display a steeper inverted S-shaped curve (Figure 9b). In particular, when the communication range exceeds 25, the magnitude of |β| approaches approximately 5, and the logistic curves become relatively steep. This result indicates that once a certain minimum communication range is ensured, the CO2 emission reduction associated with increasing CAV penetration tends to emerge more rapidly.

However, for communication ranges of 20 or less, the estimated inflection point takes relatively high values, indicating that a high level of CAV penetration is required before the reduction effect becomes apparent.

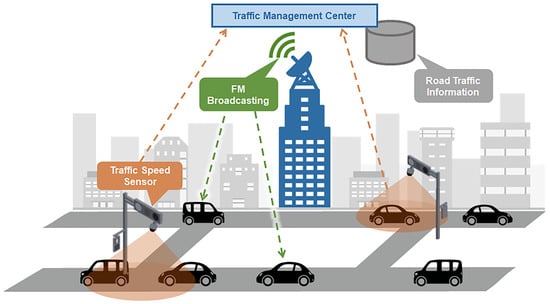

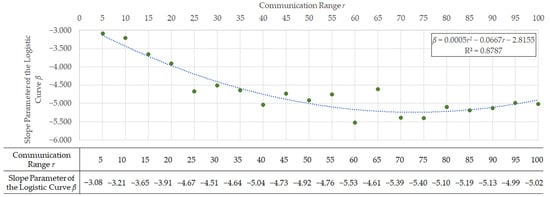

Next, we examine the relationship between the communication range and the speed at which the CO2 reduction effect emerges, as captured by the parameter . As shown in the table in Figure 10, the absolute value of does not change monotonically with increasing communication range, but instead exhibits a nonlinear pattern. When the communication range is very small, an insufficient number of CAVs can exchange information, and the effects of communication are therefore unlikely to materialise. Conversely, when the communication range becomes excessively large, the emission reduction effect may become less responsive to increases in the CAV penetration rate.

Figure 10.

Speed of CO2 reduction effect by communication range of CAVs. Green dots represent the slope parameter of the logistic curve, which characterizes the speed at which the CO2 reduction effect emerges. The blue curve shows the fitted approximation to the observed relationship.

This non-monotonic relationship is further confirmed by the fact that the relationship between the communication range and can be well approximated by a quadratic function (details of the comparison with other models are provided in Appendix D), as illustrated in the graph in Figure 10.

In this study, the observed behaviour is interpreted through the contrasting concepts of swarm intelligence and information homogenisation. Here, swarm intelligence does not refer to any specific cooperative algorithm or explicit form of collective optimisation. Rather, it denotes a more general mechanism whereby, under conditions in which individual vehicles make selfish decisions based on spatially limited local information, information incompleteness and heterogeneity can collectively promote traffic dispersion.

When the communication range becomes excessively large, the traffic information acquired by individual CAVs gradually converges, leading to overly homogeneous route choice behaviour. Under such conditions, vehicles are more likely to select the same or similar shortest routes, increasing the likelihood that traffic which would otherwise be dispersed becomes concentrated on specific routes. This phenomenon is consistent with established insights from traffic flow theory, which show that route choice under complete information converges to a user equilibrium corresponding to Wardrop’s first principle, while such an equilibrium is not necessarily socially optimal.

By contrast, when the communication range is moderately constrained, spatial differences arise in the sets of information available to individual vehicles, and heterogeneity in route choice information is preserved. Under such conditions of imperfect information, decentralized decision-making can, as an emergent outcome, promote the spatial dispersion of traffic flows and mitigate the concentration of congestion and emissions at the network level. Foundational studies such as Schelling’s segregation model [26] and Reynolds’ Boids model [27] provide useful theoretical backgrounds for interpreting this mechanism, as they demonstrate how localized and slightly heterogeneous information or behavioural rules can give rise to ordered patterns at the collective level.

In summary, the CO2 emission reduction effects observed in this study are not predicated on centralised control or complete information sharing. Rather, they can be interpreted as emerging from the interactions of decentralised behaviours induced by the design of the information structure, specifically the communication range. Nevertheless, these interpretations are qualitative in nature and are based on a simplified modelling framework; they do not claim the general validity of swarm-intelligence-like effects. Instead, the findings should be understood as a conceptual illustration of how the balance between information homogenisation and heterogeneity can influence traffic flow under the specific conditions considered in this study.

5. Conclusions

This study conceptually examines, using multi-agent simulation, how the communication range among CAVs and the structure of information sharing influence route choice behaviour, traffic flow distribution, and CO2 emissions. In particular, the study’s contribution lies in explicitly demonstrating that two design elements—the penetration rate of CAVs and their communication range—can exert nonlinear effects on traffic system dynamics. The obtained findings are shown to be relatively robust to variations in demand intensity based on the sensitivity analysis; however, they are conditional on the assumptions of simplified driving behaviour and the validity of CO2 emissions estimates derived from average travel speeds.

The traffic demand employed in this study is generated based on population assigned to network nodes and is not intended to reproduce actual traffic patterns, congestion levels, or observed O/D flows in Kyoto. Rather, the analysis is positioned as a conceptual experiment conducted under controlled and comparable demand conditions, aimed at isolating how differences in CAV communication range and information-sharing structures affect route choice and traffic flow distribution.

The simplifications adopted in this study include both pragmatic assumptions introduced to ensure model transparency and computational tractability, and structural assumptions that are essential to the study’s conclusions. The most critical of the latter is the assumption that traffic information is not shared homogeneously and instantaneously across all vehicles, but is instead spatially constrained by the communication range. Under this assumption, individual vehicles make decentralized route choices based on heterogeneous information, through which traffic dispersion and changes in emissions may emerge endogenously.

By contrast, elements such as the demand generation method and the CO2 emission estimation approach constitute sensitivity assumptions that influence the quantitative magnitude of the results. If these assumptions were altered, the numerical values of the estimated reduction rates would also change. Accordingly, the results of this study should not be interpreted as quantitative predictions of traffic conditions or emissions in a specific city. Rather, they should be understood as illustrating the causal mechanisms through which information-sharing structures influence traffic system behaviour under the adopted assumptions.

The findings of this study do not position the diffusion of CAVs itself as a standalone solution. Rather, they offer policy-relevant insights into how traffic information-sharing protocols should be designed as part of a broader portfolio of measures aimed at achieving sustainable urban mobility. In particular, the results suggest that by appropriately controlling the spatial range of information sharing, it may be possible to promote traffic dispersion and reduce emissions through decentralised decision-making, without relying on centralised traffic control or complete information homogenisation. This perspective is complementary to established policies such as public transport enhancement and traffic demand management.

At the same time, it cannot be ruled out that inappropriate designs of information sharing may lead to unintended effects. Excessive information homogenisation may cause many vehicles to concentrate on the same or similar routes, potentially giving rise to new congestion or an uneven concentration of demand on specific links. This indicates that expanding information sharing does not necessarily result in improved traffic efficiency in all cases, and that the design of information-sharing protocols requires careful consideration of the balance between efficiency and dispersion.

It should be noted, however, that these results represent relative, mechanism-level insights observed under simplified assumptions regarding demand structure, network representation, vehicle behaviour, and emissions estimation. Quantitative application to real cities or direct estimation of policy impacts therefore requires more detailed modelling and empirical validation.

The interpretation of the results is further clarified by adopting Wardrop’s user equilibrium—characterised by uniformly shared traffic information—as a theoretical reference regime. By restricting the communication range, spatial heterogeneity in the information available to CAVs is introduced, which suppresses convergence to full-information equilibria and may instead give rise to emergent traffic dispersion. This mechanism is consistent with the concept of swarm intelligence, whereby decentralized and selfish decision-making at the individual level can generate cooperative or efficiency-enhancing outcomes at the collective level.

6. Limitations and Future Work

The relatively robust finding of this study is the qualitative tendency whereby limiting the communication range suppresses information homogenisation and can alleviate demand concentration on specific routes. By contrast, the magnitude of emission reductions and the numerical values of what may be regarded as an “optimal” communication range depend on the demand model and the emission estimation method. These quantitative aspects therefore require further validation through sensitivity analyses and more realistic modelling frameworks.

In light of these considerations, this study has several important limitations. First, traffic demand is generated using a gravity model based on population distribution and distance, and does not explicitly reproduce realistic travel behaviours such as commuting and school trips, tourist movements, temporal demand variations, or empirically observed congestion hotspots. Moreover, the parameters of the gravity model are estimated from other metropolitan areas and do not reflect Kyoto-specific land-use structures or travel behaviour. Consequently, the resulting O/D demand may deviate from actual traffic patterns in Kyoto, and the findings should be interpreted not as quantitative predictions of real-world congestion or emissions, but as relative comparisons across scenarios.

Second, CO2 emissions are estimated using an average-speed-based emission model. While the model proposed by [39] provides a concise representation of the nonlinear relationship between vehicle speed and emissions, it does not explicitly account for microscopic driving behaviours characteristic of urban traffic, such as frequent stopping, acceleration, and deceleration. As a result, emissions may be under- or overestimated, particularly under low-speed or stop-and-go conditions.

In addition, this study assumes homogeneity in vehicle characteristics and perfect reliability of communication. Although these assumptions are essential for isolating the effects of information sharing and communication range and for ensuring comparability across scenarios, they also limit the interpretation of absolute emission levels and the realism of the results.

Furthermore, the model is not calibrated using observed O/D survey data or vehicle trajectory data. This constrains the external validity and generalisability of the findings, and the estimated emission reductions should therefore be regarded as indicative rather than definitive.

Future research should incorporate Kyoto-specific O/D data as well as empirically observed mobility data derived from GPS or smartphones in order to enhance the realism of demand modelling. Moreover, adopting more detailed emission estimation frameworks—such as COPERT [40] or MOVES [41]—that account for acceleration behaviour, vehicle heterogeneity, and intersection control would enable more quantitative and policy-relevant analyses. Finally, extending the demand model to endogenously capture rebound effects, whereby improvements in traffic efficiency induce additional travel demand, represents an important direction for the long-term evaluation of CAV deployment effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.I., T.H. and Y.K.; methodology, H.I. and Y.K.; software, H.I.; validation, H.I., T.H. and Y.K.; formal analysis, H.I. and Y.K.; investigation, T.H.; resources, H.I.; data curation, H.I.; writing—original draft preparation, H.I.; writing—review and editing, T.H. and Y.K.; visualization, H.I.; supervision, Y.K.; project administration, T.H.; funding acquisition, T.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP21K01515.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and analysis code supporting the findings of this study are openly available on GitHub at the following link: https://github.com/inoue-hiroki-kurume/Communication-Range-of-Connected-Autonomous-Vehicles-and-its-Impact-on-CO-Emissions-Reduction (accessed on 18 January 2026). The version of the code used in this study corresponds to commit 9d9a653.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this paper, the author used Python 3.11 for analyzing the simulation results and QGIS 3.30.0 for handling geospatial data. The authors gratefully acknowledge KOZO KEIKAKU ENGINEERING Inc. for providing access to artisoc, the multi-agent simulation platform used in this research. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations and symbols are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control | |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence | |

| CACC | Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control | |

| CAV(s) | Connected Autonomous Vehicle(s) | |

| DSRC | Dedicated Short Range Communication | |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas | |

| IDM | Intelligent Driver Model | |

| ITS | Intelligent Transportation Systems | |

| LED | Light Emitting Diode | |

| LTE | Long Term Evolution | |

| MAS | Multi-Agent Simulation | |

| O/D | Origin–Destination | |

| TLA | Three-Letter Acronym | |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle | |

| VoT | Value of Time | |

| Symbol | Definition | Unit |

| Traffic demand between origin node i and destination node j | — | |

| Acceleration of a vehicle agent | model units (m/step2) | |

| Parameters of CO2 emission estimation model | — | |

| Slope parameter of the logistic curve | — | |

| CO2 emissions on a road segment | g/km | |

| Minimum safe distance between vehicles | m | |

| Distance to the vehicle ahead at time t | m | |

| Scaling parameter for vehicle-generation probability | — | |

| Travel distance between time steps t and t + 1 | m | |

| Duration of a simulation step | 3 s (equivalent) | |

| Euclidean distance between nodes i and j | km | |

| Population assigned to nodes i and j | persons | |

| Communication range radius of CAVs | model units (10–100) | |

| Parameters of the gravity model | — | |

| Time step index | step | |

| Vehicle speed at time t | m/step | |

| Average speed on a road segment | km/h | |

| Maximum vehicle speed | model unit (=1) | |

| CAV penetration rate (0–1) | — | |

| Inflection point of the logistic model | — | |

| Total CO2 emissions | g | |

| Minimum/maximum CO2 emissions | g | |

| Min–Max scaled CO2 emissions | — |

Appendix A

This appendix reports the standard deviations (variability) of CO2 emissions across the five repeated simulation runs conducted for each parameter setting, in order to assess the stability of the simulation results. The objective here is not to obtain precise estimates of individual numerical values, but rather to examine whether the observed patterns are strongly driven by accidental or stochastic events.

Although the results do not exhibit perfectly uniform trends across all conditions, a clear tendency can be observed whereby the standard deviation across repetitions becomes relatively smaller as the CAV penetration rate increases. This suggests that, as the share of CAVs rises, the occurrence of localised congestion and incidental traffic disruptions is relatively suppressed, leading to more stable system-wide behaviour.

By contrast, under low penetration rates, traffic flows are more sensitive to initial conditions and individual route choice variations, resulting in comparatively larger variability across repeated runs. This reflects the fact that, given the stochastic elements embedded in the model, dispersion in outcomes is unavoidable when CAV penetration remains low.

Overall, these findings indicate that the main conclusions of this study are relatively robust to inter-run variability, particularly in the medium-to-high penetration range. Nevertheless, it should be noted that these results are obtained under the simplified demand settings, network representation, and behavioural rules adopted in this study, and do not aim to capture the full range of variability present in real-world traffic systems. This limitation should be considered alongside the sensitivity analysis of traffic volumes presented in Appendix B, which together define the conditions under which the results of this study should be interpreted.

Table A1.

Standard Deviations across Five Repeated Simulation Runs for Each Setting.

Table A1.

Standard Deviations across Five Repeated Simulation Runs for Each Setting.

| Standard Deviation of CO2 Emissions | Penetration Rate of CAVs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.90 | 1.00 | ||

| Communication Range | 5 | 2432 | 2595 | 3388 | 2363 | 1901 | 1197 | 2615 | 2310 | 3490 | 826 | 1370 |

| 10 | 2432 | 2447 | 2852 | 4463 | 2982 | 3270 | 2225 | 2696 | 3197 | 761 | 3191 | |

| 15 | 2432 | 2420 | 3334 | 2990 | 2159 | 3281 | 3797 | 1647 | 1811 | 1722 | 1681 | |

| 20 | 2432 | 3954 | 1969 | 3742 | 4122 | 2341 | 2297 | 2441 | 2997 | 978 | 2437 | |

| 25 | 2432 | 3746 | 3603 | 2602 | 2626 | 3135 | 2964 | 1631 | 3176 | 1883 | 3761 | |

| 30 | 2432 | 3828 | 2887 | 3571 | 1086 | 835 | 2219 | 2167 | 3534 | 1847 | 1119 | |

| 35 | 2432 | 3328 | 2223 | 1991 | 2299 | 2466 | 2729 | 647 | 2394 | 1999 | 930 | |

| 40 | 2432 | 4536 | 4850 | 2886 | 2962 | 2862 | 4522 | 2954 | 997 | 1383 | 1876 | |

| 45 | 2432 | 2522 | 3446 | 3220 | 2768 | 3266 | 1934 | 1881 | 2330 | 2860 | 1531 | |

| 50 | 2432 | 986 | 3811 | 5274 | 1859 | 2286 | 3804 | 2259 | 2579 | 2682 | 1726 | |

| 55 | 2432 | 5017 | 2865 | 2465 | 1460 | 677 | 2144 | 2502 | 1552 | 1563 | 2417 | |

| 60 | 2432 | 2666 | 2156 | 3243 | 1037 | 2695 | 2896 | 3780 | 1322 | 1432 | 2182 | |

| 65 | 2432 | 5352 | 2673 | 1954 | 2392 | 3694 | 1283 | 1646 | 3245 | 1252 | 1156 | |

| 70 | 2432 | 1801 | 3446 | 3975 | 2139 | 3777 | 2525 | 2854 | 2644 | 756 | 1743 | |

| 75 | 2432 | 1379 | 898 | 3551 | 2029 | 5825 | 2734 | 1224 | 3311 | 723 | 2248 | |

| 80 | 2432 | 3963 | 3594 | 3435 | 3099 | 4323 | 3791 | 3479 | 1930 | 2170 | 2100 | |

| 85 | 2432 | 1913 | 3124 | 2871 | 2131 | 2094 | 3818 | 2481 | 1872 | 1671 | 1439 | |

| 90 | 2432 | 5682 | 1502 | 4470 | 3595 | 2675 | 4190 | 1363 | 1404 | 1402 | 2385 | |

| 95 | 2432 | 3507 | 2164 | 1561 | 3227 | 3098 | 1567 | 3231 | 1979 | 1547 | 1711 | |

| 100 | 2432 | 3303 | 2993 | 1810 | 3557 | 1507 | 1765 | 2707 | 1653 | 2303 | 2818 | |

Note: A red-to-blue colour scale is applied according to the magnitude of the standard deviation of CO2 emissions.

Appendix B

This appendix examines the robustness of the results with respect to the set of modelling assumptions adopted in this study—namely, the demand generation method, network representation, vehicle behaviour rules, and emission estimation approach—by conducting a stress test (sensitivity analysis) that evaluates how changes in traffic volume (traveller appearance frequency) affect CO2 emissions.

Specifically, the traveller appearance frequency was set at three levels (0.10, 0.25, and 0.50), and the corresponding rates of change in CO2 emissions were calculated for each case. In this analysis, the communication range was fixed at 70, a value for which relatively high emission reduction effects were observed in the main analysis. The decision to fix the communication range at does not imply that this value is assumed to be universally optimal. Rather, the baseline results indicate that represents a representative condition under which CO2 emission reductions were observed to be relatively clear and stable across a wide range of CAV penetration rates. It was therefore selected as a reference point to enable a clean assessment of how changes in traffic demand affect the results while holding communication conditions constant.

The purpose of this sensitivity analysis is not to identify an optimal communication range for each demand level, but to examine whether the main conclusions of this study—namely, the qualitative effects of communication range and information-sharing structure on traffic flow and emissions—are preserved when traffic volume varies. It should also be noted that qualitatively similar tendencies were observed for communication ranges in the vicinity of , indicating that the findings of this analysis are not dependent on this specific value alone.

The sensitivity matrices constructed for each CAV penetration rate (0.1–1.0), shown in Table A2, indicate that the sensitivity values are positive in most cases, confirming that increases in traffic volume (traveller appearance frequency) consistently lead to increases in CO2 emissions. This result suggests that the model responds to demand changes in an intuitively consistent manner.

At the same time, the magnitude of these sensitivities is generally limited. Compared with the effects associated with CAV penetration rates and communication ranges discussed in the main text, the impact of changes in traffic volume is relatively small. This indicates that, although variations in demand levels affect the absolute level of CO2 emissions, they do not overturn the main conclusions of this study—namely, the qualitative influence of communication range and information-sharing structure on traffic flow and emission dynamics.

It should also be noted that this study does not incorporate detailed road capacity data, nor does it explicitly model signal control or intersection behaviour. Vehicle route choice is based on a simplified behavioural rule using the A* (A-star) algorithm to identify shortest-time paths. Accordingly, this sensitivity analysis is not intended to precisely reproduce real-world demand fluctuations, but rather to verify that the overall model behaviour does not break down under extreme demand conditions.

Table A2.

Sensitivity matrix constructed for each CAV penetration rate (0.1–1.0).

Table A2.

Sensitivity matrix constructed for each CAV penetration rate (0.1–1.0).

| Penetration Rate of CAVs | Traveler Appearance Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| From | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.144 | 0.120 | |

| 0.25 | 0.296 | 0.217 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.405 | 0.357 | ||

| 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.143 | 0.097 | |

| 0.25 | 0.294 | 0.144 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.350 | 0.251 | ||

| 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.127 | 0.093 | |

| 0.25 | 0.267 | 0.152 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.338 | 0.263 | ||

| 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.102 | 0.076 | |

| 0.25 | 0.221 | 0.130 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.291 | 0.230 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.056 | 0.048 | |

| 0.25 | 0.129 | 0.100 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.201 | 0.181 | ||

| 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.085 | 0.048 | |

| 0.25 | 0.189 | 0.057 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.202 | 0.109 | ||

| 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.029 | 0.026 | |

| 0.25 | 0.069 | 0.059 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.118 | 0.111 | ||

| 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.032 | 0.013 | |

| 0.25 | 0.077 | 0.005 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.063 | 0.010 | ||

| 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.007 | 0.008 | |

| 0.25 | 0.018 | 0.022 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.040 | 0.043 | ||

| 1.0 | 0.1 | −0.007 | −0.011 | |

| 0.25 | −0.018 | −0.034 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.058 | −0.070 | ||

In addition, an additional sensitivity analysis was conducted by treating the communication range as a key system parameter and examining three levels of traveller appearance frequency (0.10, 0.25, and 0.50) for each communication distance ranging from 5 to 100 (Table A3). The results show that, for all communication distances, increases in demand consistently lead to increases in CO2 emissions, while the magnitude of this sensitivity depends strongly on the communication range.

Under short-range communication, the sensitivity of CO2 emissions to demand fluctuations is relatively high. As the communication range increases, however, this sensitivity declines rapidly and reaches a minimum at intermediate communication distances (approximately 25–30). Beyond this range, further expansion of the communication distance yields only limited additional reductions in sensitivity, indicating a saturation in robustness to demand variation.

These findings indicate that the demand sensitivity of CO2 emissions varies non-monotonically with the communication range and suggest the existence of a band of communication distances that are relatively robust to demand fluctuations. Importantly, this analysis is not intended to provide a precise estimate of an optimal communication range. Rather, its purpose is to verify that the design of the information-sharing range can also influence the stability of system responses to demand variations.

Taken together, the sensitivity analyses presented in this appendix serve as supplementary validation that the main qualitative conclusions of this study remain robust to changes in demand levels, even under the simplified modelling assumptions adopted here. Analyses incorporating more realistic demand structures and explicit capacity constraints remain an important direction for future research.

Table A3.

Sensitivity matrix constructed for each communication range (5–100).

Table A3.

Sensitivity matrix constructed for each communication range (5–100).

| Communication Range | Traveler Appearance Frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| To | 0.1 | 0.25 | 0.5 | |

| From | ||||

| 5 | 0.1 | 0.072 | 0.060 | |

| 0.25 | 0.163 | 0.119 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.242 | 0.213 | ||

| 10 | 0.1 | 0.057 | 0.035 | |

| 0.25 | 0.131 | 0.050 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.153 | 0.095 | ||

| 15 | 0.1 | 0.060 | 0.045 | |

| 0.25 | 0.137 | 0.081 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.189 | 0.150 | ||

| 20 | 0.1 | 0.036 | 0.011 | |

| 0.25 | 0.084 | −0.007 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.055 | −0.014 | ||

| 25 | 0.1 | −0.009 | 0.004 | |

| 0.25 | −0.023 | 0.029 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.019 | 0.057 | ||

| 30 | 0.1 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| 0.25 | 0.002 | 0.013 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.017 | 0.025 | ||

| 35 | 0.1 | 0.019 | −0.004 | |

| 0.25 | 0.046 | −0.043 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.020 | −0.090 | ||

| 40 | 0.1 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |

| 0.25 | 0.002 | 0.012 | ||

| 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.023 | ||

| 45 | 0.1 | −0.015 | −0.003 | |

| 0.25 | −0.039 | 0.011 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.015 | 0.022 | ||

| 50 | 0.1 | −0.010 | −0.006 | |

| 0.25 | −0.025 | −0.008 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.029 | −0.017 | ||

| 55 | 0.1 | −0.021 | −0.010 | |

| 0.25 | −0.054 | −0.007 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.050 | −0.015 | ||

| 60 | 0.1 | −0.008 | −0.008 | |

| 0.25 | −0.021 | −0.021 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.043 | −0.042 | ||

| 65 | 0.1 | −0.027 | −0.008 | |

| 0.25 | −0.071 | 0.009 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.042 | 0.018 | ||

| 70 | 0.1 | −0.017 | −0.007 | |

| 0.25 | −0.043 | −0.003 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.036 | −0.005 | ||

| 75 | 0.1 | −0.037 | −0.020 | |

| 0.25 | −0.097 | −0.026 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.109 | −0.054 | ||

| 80 | 0.1 | −0.015 | −0.006 | |

| 0.25 | −0.039 | 0.001 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.028 | 0.002 | ||

| 85 | 0.1 | −0.014 | −0.008 | |

| 0.25 | −0.036 | −0.010 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.040 | −0.021 | ||

| 90 | 0.1 | −0.019 | −0.015 | |

| 0.25 | −0.049 | −0.033 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.080 | −0.067 | ||

| 95 | 0.1 | −0.027 | −0.008 | |

| 0.25 | −0.070 | 0.011 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.039 | 0.022 | ||

| 100 | 0.1 | 0.072 | 0.060 | |

| 0.25 | −0.018 | −0.034 | ||

| 0.5 | −0.058 | −0.070 | ||

Appendix C

In this appendix, three nonlinear models—Logistic, Gompertz, and Exponential—are compared in order to examine which functional form most parsimoniously summarises the nonlinear relationship between CAV penetration rates and CO2 emissions observed for each communication range . The purpose of this comparison is not to identify a strict causal model, but rather to select a descriptive functional form that can capture the common shape characteristics observed in the simulation results, namely the onset, acceleration, and saturation of emission reduction effects.