Abstract

This review examines scientific and engineering strategies for adapting bituminous and asphalt concrete materials to the highly diverse climates of Central Asia. The region’s sharp gradients—from arid lowlands to cold mountainous zones—expose pavements to thermal fatigue, photo-oxidative aging, freeze–thaw cycles, and wind abrasion. Existing climatic classifications and principles for designing thermally and radiatively resilient pavements are summarized. Special emphasis is placed on linking binder morphology, rheology, and climate-induced transformations in composite bituminous systems. Advanced characterization methods—including dynamic shear rheometry (DSR), multiple stress creep recovery (MSCR), bending beam rheometry (BBR), and linear amplitude sweep (LAS), supported by FTIR, SEM, and AFM—enable quantitative correlations between phase composition, oxidative chemistry, and mechanical performance. The influence of polymeric, nanostructured, and biopolymeric modifiers on stability and durability is critically assessed. The review promotes region-specific material design and the use of integrated accelerated aging protocols (RTFOT, PAV, UV, freeze–thaw) that replicate local climatic stresses. A climatic rheological profile is proposed as a unified framework combining climate mapping with microstructural and rheological data to guide the development of sustainable and durable pavements for Central Asia. Key rheological indicators—complex modulus (G*), non-recoverable creep compliance (Jnr), and the BBR m-value—are incorporated into this profile.

1. Introduction

The modern paradigm of infrastructure development is increasingly shaped by ecological sustainability. The concepts of green roads [1,2], circular economy [3,4], and net-zero infrastructure [5] have become integral components of both engineering practice and policy frameworks. The term green roads implies not only the application of energy-efficient construction technologies but also a systemic materials approach—from raw material extraction and production to end-of-life recycling—aimed at minimizing greenhouse gas emissions and reducing the environmental footprint of transport infrastructure.

International strategies for carbon emission reduction reflect this direction: recent national and intergovernmental road maps include targeted plans to transition transport infrastructure toward low- or zero-emission systems, requiring the revision of materials, design methodologies, and construction processes.

At the core of this transformation lies a persistent engineering dilemma—how to balance durability, sustainability, and cost. Many environmentally friendly solutions either increase initial costs or exhibit reduced service life under extreme climatic conditions. Thus, economically viable and sustainable materials must simultaneously ensure adequate mechanical robustness and long-term durability under environmental stresses. This trade-off remains a central subject of ongoing research and pilot-scale validation.

Globally, there is a growing momentum toward integrating recycled materials into the road construction sector, with the European Union, China, and India leading in both implementation and standardization. In Europe, circular principles are being embedded directly into infrastructure value chains, supported by numerous research programs and B2B initiatives on material recycling. In Asia—particularly in India—large-scale programs utilizing shredded plastics and crumb rubber in asphalt concrete have demonstrated both industrial-scale deployment [6] and thousands of kilometers of pavement incorporating recycled plastics [7]. China continues to advance large national programs on reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) reuse in urban and highway networks. Parallel to these efforts, metric reviews have systematically analyzed the effects of recycled components on rutting resistance, elastic modulus, and bitumen savings [8,9].

Against this global background, there is an increasing demand for low-cost, low-carbon, and adaptive solutions that can be rapidly deployed in regions with limited recycling infrastructure. Such approaches should satisfy three principal criteria:

- 1.

- availability of local secondary resources (plastics, lignin, rubber, industrial by-products);

- 2.

- technological simplicity and compatibility with existing production processes (dry/wet integration, masterbatch techniques, local mini-plants);

- 3.

- compliance with required mechanical and rheological performance under regional climatic conditions.

Comprehensive life-cycle assessment (LCA) and economic feasibility analyses are essential decision-making tools for policymakers and infrastructure stakeholders [10].

Central Asia—comprising primarily Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Mongolia, and Afghanistan—occupies a strategically significant position within the evolving global transport architecture. The Middle Corridor and related Belt & Road initiatives [11] make the region a potential hub for both transcontinental and domestic transport routes, driving a growing demand for reliable and quickly deployable road infrastructure. This geopolitical and economic context dictates massive construction needs—from rural access roads to major highways—while the region’s climatic heterogeneity (continental temperature extremes, aridity, high wind loads, and mountainous hydrology) imposes stringent and often contrasting material requirements [12].

Consequently, solutions based on locally available secondary resources (such as lignin from wood processing, recycled plastics, waste tires, and carbon composite residues) or those enabling simple, cost-effective technological adaptation (e.g., masterbatch incorporation, dry dosing methods) emerge as priorities not only from an ecological but also from an economic standpoint. Recent analytical and policy reports highlight this scenario for the Middle Corridor as a catalyst for the development of locally sourced, affordable, and rapid road construction technologies [13].

According to current national and regional transport development programs, Central Asia faces a substantial increase in planned roadway expansion over the next decade. Kazakhstan’s “National Infrastructure Development Plan 2025” outlines more than 11,000 km of new or reconstructed highways, including ~3200 km of international corridors intended for heavy-load traffic classes TC-1 and TC-2 [14]. Uzbekistan’s “Transport Strategy 2035” similarly targets over 8000 km of upgraded roads, with projected increases in freight volumes of 40–45% and the expansion of high-category pavement structures designed for intense axle loads (>10 t/axle) [15]. Independent assessments confirm these trends: a regional feasibility review published by the Asian Development Bank highlights that cumulative demand for high-performance pavements along the Middle Corridor may exceed 25,000 km by 2035 due to expected freight redistribution between Europe and China. These figures underscore the urgency of developing climate-adaptive and resource-efficient binder technologies capable of withstanding the region’s extreme environmental loads and traffic classes.

Based on these considerations, the objectives of this review are:

- to systematize current approaches to the recycling and adaptation of polymer–bitumen composites, from mechanical recycling of plastics to thermo-mechanical and chemical compatibilization methods;

- to identify the interrelation between climatic and environmental factors in Central Asia and the performance requirements of materials, highlighting climate-determined rheological passports for asphalt binders and mixtures;

- to outline technological and policy directions (LCA-oriented implementation scenarios, pilot standards, and localized supply chains) that may enable the safe and large-scale application of secondary resources in the regional road construction sector.

These goals lie at the intersection of materials science, rheology, and infrastructure policy, thus requiring an interdisciplinary perspective—which this review seeks to provide [9].

Building on this context, the present review introduces a novel integrative framework that links climatic zoning with rheological material design. First, the analysis explicitly incorporates Köppen–Geiger climate stratification into the formulation of rheological passports for bituminous binders and asphalt mixtures, enabling climate-informed performance benchmarking across the diverse environmental conditions of Central Asia. Second, the review synthesizes and evaluates combined aging protocols—including PAV, UV exposure, and freeze–thaw cycling—as a unified methodology for reproducing coupled climatic stressors characteristic of continental and sharply continental regions. Third, the study advances a climate-driven approach to binder selection, in which microstructural, morphological, and rheological criteria are directly anchored to regional temperature regimes, radiation loads, and hydrological variability. Finally, the core methodological contribution of this work is the introduction of the “Climate Rheology Profile”, a conceptual and practical framework that integrates climate mapping with multiscale binder characterization to support the development of adaptive, durable, and sustainable pavement materials tailored to Central Asia.

2. Nature, Structure, and Challenges of Road Materials: Adaptivity as a Key Parameter

2.1. The Functional Role of the Surface Layer and Its Relation to Binder Structure

The performance of the surface course is governed by the interplay between its rheological response and the multiscale structure of the binder. Mechanical durability under cyclic loading and environmental resistance to moisture, oxidation, and ultraviolet radiation arise from the microstructural organization of the binder film, its relaxation dynamics, and its susceptibility to oxidative densification. Accordingly, the functional state of the pavement surface cannot be interpreted solely through macroscopic mixture parameters but requires explicit consideration of binder chemistry, colloidal architecture, and aging kinetics.

Modern materials science tools for describing this transition “from molecule to pavement” include SARA fractionation and rheological characterization (DSR, BBR, MSCR), which provide a quantitative link between chemistry, microstructure, and performance behavior. Review studies emphasize that understanding the colloidal organization of bitumen is the key to controlling its functional properties [16].

2.2. Chemical–Fractional Composition and Colloidal Organization

Changes in the SARA ratio directly affect the viscoelastic response and aging susceptibility: an increased asphaltene fraction leads to higher stiffness, reduced plasticity, and a greater risk of low-temperature brittleness, whereas an excess of oily components decreases thermal stability. These correlations are consistently confirmed by both classical and recent studies employing SARA fractionation [17,18] and graph-analytical [19] methods.

Contemporary models describe bitumen as a colloidal system of complex composite structural entities (CSEs, micelle-like aggregates)—asphaltene cores surrounded by resin shells and dispersed in an aromatic matrix. The association–dissociation equilibrium of these entities depends on temperature, oxygen content, and the presence of modifiers.

Transitions between sol, sol–gel, and gel states explain the observed nonlinear rheological behavior [20,21,22]. The progressive growth of the aggregate network during aging accounts for the irreversible increase in complex modulus (G*) and the loss of relaxation capability [16].

2.3. Aging Mechanisms and Their Kinetics

Oxidative aging of bitumen manifests through the formation of carbonyl and sulfoxide groups, as identified by FTIR spectroscopy, and correlates with the increase in stiffness (G*) and non-recoverable compliance (Jnr) in rheological tests. Petersen and subsequent studies demonstrated that thermo-oxidative reactions are governed not only by temperature but also by mass transport factors—oxygen availability and nanofilm thickness—making the kinetics of aging strongly dependent on pavement geometry and service conditions.

Laboratory protocols such as RTFOT and PAV [23,24] simulate these effects, yet accurate correlation with field reality still requires comprehensive long-term data. Camargo et al. [25] further distinguished between purely thermal and oxidative pathways, demonstrating that temperature rise accelerates carbonyl formation and increases G*, while oxygen availability and UV exposure modify the oxidation pathway (thermo- vs. photo-oxidation) [25].

However, RTFOT and PAV procedures were developed to simulate generic thermal-oxidation exposure and do not capture several field-relevant coupled factors that dominate degradation in continental and sharply continental climates such as those across Central Asia. RTFOT/PAV omit direct ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, which drives photo-oxidative pathways producing chemical signatures (and surface embrittlement) distinct from thermal oxidation; combined heat+UV experiments show substantially faster increases in modulus and oxidation indices than heat alone [26].

The kinetics of oxidation in thin pavement surface films are controlled by oxygen diffusion and microstructural heterogeneity; standard oven-based protocols do not reproduce the spatial gradients of oxygen ingress, nor the influence of nanofilm thickness on reaction rates, leading to under- or mis-estimation of carbonyl/sulfoxide accumulation and consequent rheological stiffening [27].

Central Asia is characterized by large diurnal temperature amplitudes and frequent freeze–thaw and moisture cycles; these induce thermomechanical fatigue and microcracking that accelerate ingress of oxygen and water and thus alter aging pathways. RTFOT/PAV procedures do not include cyclic thermal or moisture loading and therefore cannot reproduce these coupled effects [27].

To improve correlation with field aging in the region should made adoption of combined accelerated protocols that superimpose UV exposure and controlled moisture/freeze–thaw cycles on top of RTFOT/PAV treatments, calibration of accelerated schedules against field-extracted binders from instrumented pilot sections (iterative matching of chemical indices—carbonyl/sulfoxide by FTIR and rheological measurings G*(T), δ(T), J; and reporting of film thickness, oxygen partial pressure and UV dose in aging experiments to allow reproducible comparison. Several recent studies show that such combined or alternative aging sequences produce chemical and mechanical signatures closer to field-aged binders than RTFOT/PAV alone [26].

2.4. Effects of Polymer and Biopolymer Modifiers on Structure and Rheology

Polymeric modifiers (SBS, EVA, PPA, crumb rubber) and biopolymeric additives (lignin, modified cellulose, bio-oils) affect bitumen structure through diverse mechanisms. Polymers may form continuous or semi-continuous networks, enhancing the elastic component; fillers act as rigid inclusions, increasing the modulus; biopolymers can function as antioxidants and compatibilizers.

Numerous studies have shown that the phase distribution of the polymer within the bituminous matrix is critical to achieving improved performance, whereas excessive coalescence of polymer domains may deteriorate low-temperature flexibility [16,28].

In the region, SBS (styrene-butadiene-styrene) is primarily imported from international manufacturers. Several SBS importers and distributors are registered in Kazakhstan and neighboring countries, and the global market exhibits price volatility due to fluctuating raw material prices (ICIS contract prices increased in 2024). The estimated price of commercial grades of SBS ranges widely from ≈1500 to 3500 USD/t, depending on the grade and logistics. Practical application requires wet-process equipment (heating bitumen to 160–190 °C, intense shear mixing; note: 180 °C, 4000 rpm, 2 h for laboratory formulations) [29]. These requirements increase the CAPEX of a PMB production plant and the energy intensity of production.

The availability of crumb rubber in Kazakhstan is confirmed by significant volumes of waste tire accumulation, as well as the emergence of domestic recycling lines. This makes it technically feasible to locally source raw materials for rubber modifiers, although the actual volumes of material suitable for asphalt production depend on fraction size, purification, and de-feeder technology. The production of rubberized bitumen typically involves mixing bitumen with crumbs at ~175–180 °C and high shear rates (in practice: 40–60 min in industrial plants, 175 °C/5000 rpm in the laboratory) [30], which requires specialized mixers and degassing control.

Lignin as a bio-raw material is potentially available through local pulp and paper mills: paper production volumes in Kazakhstan are measured in tens of thousands of tons per year (approx. ~83 × 103 tons of paper in 2022), which theoretically corresponds to the potential of by-product lignin. However, industrial-scale extraction is technically and economically dependent on the availability of pulp mills with cost-effective extraction systems (LignoBoost, etc.) [31]. Technical lignins are typically valued globally at approximately USD 250–600/t (depending on purity and extraction technology), making them an economically attractive additive given their local availability and minimal logistics costs [32]. Converting lignin into bitumen-compatible forms requires additional pre-processing (fractionation, sulfonation/esterification, fine mechanical processing) and thermal stability control at asphalt production temperatures (WMA/HMA strategies).

2.5. Design Challenges for Central Asia and Kazakhstan

The climatic conditions of the region—wide diurnal temperature ranges, high solar radiation in the south, prolonged frosts in the north, and rapidly changing humidity in mountain areas—amplify the degradation mechanisms discussed above. Field observations and regional monographs highlight the inconsistency between standard classification systems (PG, EN specifications) and local realities, suggesting the need to adapt test parameters and formulations accordingly [33,34,35].

Practically, this implies that:

- Standard polymer modification recipes require regional adaptation (dosage, incorporation method, polymer pre-treatment);

- Local raw material characteristics must be considered (bitumens derived from regional crudes exhibit distinctive SARA profiles);

- Innovative modifiers (biocomponents, nanophases, combined polymer systems) should be tested under conditions that simulate real regional climates, including UV exposure and freeze–thaw cycling [36,37,38].

2.6. Section Summary and Research Gaps

While the fundamental principles of bitumen structure and aging are well established, several application-oriented research gaps remain critical for Central Asia:

- systematic correlation of SARA profiles of local bitumens with pavement performance across climatic zones of Kazakhstan;

- long-term field evaluation of polymer–biopolymer composites under regional solar radiation and thermocyclic conditions;

- standardization of accelerated laboratory aging methods (combined RTFOT/PAV + UV + freeze–thaw protocols) to ensure valid correspondence with field performance.

3. Interrelation Between the Climate of Central Asia and Engineering Challenges

3.1. Climatic Stratification of Central Asia

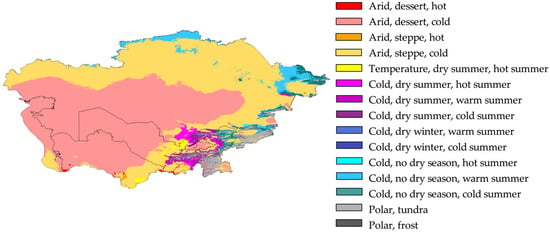

Central Asian countries, including Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Mongolia, are characterized by pronounced spatial variability of climatic conditions, ranging from moderately continental and continental steppe and semi-desert zones to high-mountain, alpine, and arctic climate types. For quantitative stratification of the region, the widely accepted Köppen–Geiger system is convenient; recent high-resolution mapping demonstrates significant zone shifts in Central Asia and predicts further warming and aridization in the 21st century [39]. Higher spatiotemporal resolution maps (1 km, historical and scenario-based data) additionally confirm that even within administratively homogeneous areas, shifts between climate types are observed (toward drier and warmer clusters), necessitating regionally targeted engineering (Figure 1) [40].

Figure 1.

Koppen-Geiger climate classification map for Central Asia (1980–2016) [40].

Based on climatic stratification and available literature, several degradation scenarios and corresponding engineering challenges can be identified:

Northern Continental Zones (Northern and Eastern Kazakhstan)

These territories are characterized by long and harsh winters, several months of ground freezing, and large temperature and humidity fluctuations. The main threats to pavement integrity arise from low-temperature cracking, cohesive failures, and loss of adhesion due to moisture penetration into frozen layers. Studies of frost behavior of road structures in Kazakhstan document significant frost depth and complex thawing dynamics, which require the use of binders with low stiffness at subzero temperatures and high relaxation capacity (e.g., elastomers, plasticizers). Practices and standards (such as regional RILEM recommendations) emphasize the need to control BBR parameters (stiffness and m-value) for such climates [41,42].

Southern Semi-Desert and Continental Regions (Southern Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan)

These zones are dominated by high daytime temperatures, rapid nocturnal cooling, and intense insolation. Operational risks include rutting, thermo-oxidative, and photo-oxidative aging. Studies demonstrate that UV exposure not only increases bitumen stiffness but can also induce the formation of a surface “hard crust,” reducing elasticity, especially in polymer-modified bitumens [43]. For such regions, modifications with antioxidants, UV absorbers, nanofillers, as well as engineering measures such as reflective “light-colored” coatings, have been proposed to reduce thermal loading.

Mountainous and High-Mountain Territories (Tien Shan, Pamir, etc.)

Mountain regions combine extreme factors: intense radiation, large diurnal temperature fluctuations, moisture, and water penetration into the pavement. This combination creates a dual aging mechanism: photostress and thermo-cyclic fatigue. In high-altitude regions, as shown by experiments with reclaimed mixtures, combined aging (UV + freeze–thaw) significantly deteriorates structural stability and mechanical properties. Xie et al., 2025 studied asphalt mixture performance under combined UV radiation and freeze–thaw cycles, showing substantial reductions in fatigue durability [44]. Engineering solutions here must include multi-level modification: polymer grids, UV stabilizers, appropriate selection of aggregates, and climatically adapted laboratory testing.

3.2. Key Climatic Factors and Their Engineering Implications

Climatic changes determining the performance of asphalt pavements in the region include: the range and frequency of extreme temperatures (diurnal and seasonal amplitudes), relative humidity and precipitation patterns, total solar radiation (including UV intensity), wind speed (erosion potential, evaporation, and particle blow-off), and elevation above sea level (high-altitude regions are characterized by enhanced UV radiation and sharper diurnal temperature swings). These parameters affect three main degradation mechanisms: (1) thermo-oxidative aging of bitumen; (2) thermo-cyclic and low-temperature cracking; (3) mechanical damage: rutting and fatigue cracking under repeated loads [45,46,47].

Key parameters influencing pavement properties include:

Temperature. Thermal regimes determine the rate of thermo-oxidative kinetics and evaporation of light fractions [25]: upon heating with oxygen access, there is a rapid increase in carbonyl and sulfoxide groups, stiffness growth (|G*|), and reduced elasticity. Consequently, this is directly linked to brittle failure risk at low temperatures and decreased fatigue resistance in the medium temperature range [25].

UV Radiation and Elevation. In high-altitude regions (Pamir, Tien Shan), UV intensity increases; recent studies identify a specific mechanism of “photo-oxidative” aging [43], distinct from classical thermo-oxidation: photolysis of the surface layer produces a hard crust (surface hardening) and depth-wise property gradients (gradient aging) [48], increasing the risk of surface cracks and fragmentary pavement failure.

Moisture and Frost Regime. Frequent freeze–thaw cycles and high seasonal frost depth (in northern and mountainous Kazakhstan minima reach −46 °C in some locations) cause moisture accumulation and redistribution within structural layers, increasing internal pressure and promoting longitudinal and transverse thermal cracking; studies focused directly on Kazakhstan document low-temperature damage statistics and critical temperature strength calculation features [33,49].

Wind and Abrasive Factors. Wind speeds in desert and semi-desert areas intensify particle blow-off (dust, sand), leading to surface abrasion, rapid aggregate polishing, and roughness changes. These factors affect traction and braking performance. In addition, wind erosion modifies the surface thermal balance (locally increasing or decreasing evaporation/cooling rates), indirectly influencing aging rate and temperature distribution across the pavement [39,50].

3.3. Concept of “Climatically Selective” Formulations

The above indicates that a universal formulation for the entire region is infeasible: binder and mixture optimization must be linked to local climatic factors and operational loads. Practically, this means that for northern and high-altitude zones, binders with improved low-temperature plasticity (below critical brittle temperatures) or compounded/modification (plasticizers, elastomeric additives) that reduce stiffness at subzero temperatures are preferred, as demonstrated by studies on compounding and low-temperature performance [51]. For warm and sunny regions, binders with increased thermal resistance and photo-oxidative stability (antioxidants, UV stabilizers, nanomodifiers) are required, along with pavement designs with optimized reflective properties (heat-reflective coatings) to reduce surface temperature [43,52,53].

For semi-desert and wind-exposed areas requiring enhanced particle abrasion protection, careful selection of aggregates and gradation, with mandatory roughness control before and after sandblasting, is necessary. Additionally, water-draining pavement types and measures against fine-particle blow-off (engineered shoulder design, vegetation cover) are recommended [54,55,56].

3.4. Regional Standards and Engineering Practices

Regional adaptation of bituminous binders and asphalt mixtures is an essential component of modern pavement engineering, particularly in countries with pronounced climatic heterogeneity. Analysis of international practices shows that nearly all advanced road systems employ national or regional standards linked to specific temperature ranges, humidity, and material aging characteristics.

China is a prominent example, with climates ranging from humid subtropical to arid continental. National standards (JTG F40–2004 [57]) introduce climate-oriented categories of binders and asphalt mixtures based on service temperature ranges and solar radiation intensity. Mixes using crumb rubber and thermoplastic elastomers are actively developed to enhance aging resistance and rutting performance under hot climates. Xu et al., 2023 reported that using rubber powder with SBS-modified bitumen increased rutting resistance by 35–40% and significantly reduced sensitivity to temperature fluctuations in the 25–60 °C range [58]. Other studies [59,60] demonstrate that optimization based on MSCR and DSR criteria, along with UV stabilizers (TiO2, ZnO), increases pavement durability in regions with high solar insolation, such as western China (Xinjiang, Gansu).

Indian practice also follows climatic stratification. Considering extreme temperatures (from +50 °C in Rajasthan deserts to +15 °C in Himachal Pradesh mountains), regional guidelines recommend polymer-modified binders, primarily with polyethylene waste and natural latex [61]. These modifications enhance deformation and thermo-oxidative resistance while maintaining acceptable viscosity at low temperatures. India promotes the Waste-to-Road concept, dispersing plastic waste (PET, PP, HDPE) into bitumen at high temperatures, simultaneously addressing recycling and thermal resistance improvement [8].

In Europe, where climatic conditions range from subarctic to moderate Atlantic, binder classification systems are established in EN 12591 [62] and several national documents. Special attention is paid to northern countries (Sweden, Norway, Finland), where modified bitumens with increased low-temperature cracking resistance and improved adhesion under moisture saturation are used. Nordic Road Association (NVF) and FASpec (Finland Asphalt Specification) guidelines define low-temperature properties measured via BBR and DSR, and durability after artificial aging RTFOT+PAV [63]. For cold Scandinavian regions, formulations with reduced asphaltene content and biomodifiers (e.g., tall oil) are proposed, lowering shear modulus at −20 °C without adhesion loss [64,65].

In North America, a similar principle is implemented in the Superpave Performance Grading (PG) system, where climate parameters (maximum and minimum design pavement temperatures) directly determine binder selection.

Comparison of these regional approaches demonstrates that climate-oriented standardization and binder design have become a primary direction in pavement engineering. For Central Asia, where climate spans extremely cold (−40 °C) to hot (+45 °C) conditions, the experience of China, India, and Northern Europe is particularly relevant. Engineering adaptation must include both material-technological solutions (regulating binder phase composition and rheological properties, optimizing aggregates and modifiers) and regulatory measures—developing regional classifications, similar to the PG system, considering not only temperature extremes but also radiation levels, wind loads, and moisture cycles.

3.5. Conclusions and Implications for Design

Central Asia’s climatic stratification, with contrasting temperatures, high insolation, and seasonal humidity fluctuations, precludes the use of universal asphalt binder formulations. Various climatic factors, including temperature, UV radiation, moisture, wind, and elevation, differentially influence aging, cracking, and deformation processes. The Studies [39,40] show that using the Köppen–Geiger climate classification enables rational selection of binder types, modifiers, and structural solutions for specific zones.

Scientific justification of “climatically selective” formulations requires integration of climate mapping, accelerated laboratory aging scenarios, and rheological testing (DSR, BBR, MSCR). Such approaches quantitatively link climatic loads with binder property changes and allow prediction of pavement durability. Contemporary reviews emphasize the necessity of transitioning from universal standards to regionally adapted design systems [25,43].

Practical implementation requires combining material-science and engineering measures: targeted binder modification with antioxidants, UV stabilizers, and biopolymers; selection of mineral aggregates considering thermal and hydrophilic properties; and engineering measures such as reflective surfaces, drainage systems, and thermally stabilizing layers. Collectively, these approaches form the basis for climate-adaptive pavement structures resilient to Central Asia’s extreme conditions.

Central Asia’s climatic stratification dictates the need for regional adaptation of formulations: a “one-size-fits-all” binder is not justified from an engineering perspective. Analysis of combined climatic factors (temperature, UV load, moisture, wind, elevation) is essential when selecting binder type, modifiers, and pavement structure [39,40].

Scientific justification of “climatically selective” formulations requires a comprehensive methodology combining climate mapping, accelerated laboratory aging scenarios (including combined temperature and UV effects), rheological measurements (DSR, BBR, MSCR), and field observations. This approach is recommended by modern studies on bitumen aging and rheology [25,43].

Practical strategies should integrate material- and design-based measures: targeted binder modification (antioxidants, UV stabilizers, biocomponents), aggregate and gradation selection, as well as engineering measures (reflective coatings, drainage) to ensure long-term resilience of regional road infrastructure.

4. Recycled Polymers as Bitumen Modifiers

In recent years, global road construction practice has increasingly adopted polymer-modified asphalts (PMB), in which conventional petroleum bitumen is supplemented or partially replaced by various polymers. This development is driven by the need to enhance the operational performance of pavements—particularly their resistance to rutting, cracking, and aging—as well as by environmental and recyclability considerations. Classical polymers in this domain include styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS) block copolymers, ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), polyisobutylene, and others. Their use has proven effective: the binder becomes more elastic, the recovery coefficient after deformation increases, low-temperature crack resistance improves, and high-temperature deformation resistance is enhanced [35]. Reviews of contemporary literature [66,67] emphasize that such modifications significantly broaden the temperature range of asphalt mixture applications and extend their service life.

Alongside commercial polymer additives, interest has grown in more readily available sources of modifiers, particularly secondary plastics and biopolymers. In many countries, pilot projects have successfully demonstrated the practical applicability of these approaches. For instance, in the Netherlands, the PlasticRoad project (VolkerWessels) demonstrated that road and bicycle pavements can be constructed from recycled plastics, with such structures exhibiting sufficient mechanical strength and resistance to loads and temperature fluctuations [68]. In India, where plastic waste is a particularly acute problem, technologies for incorporating shredded polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) into asphalt concrete have been implemented in field conditions: polymer content typically ranges from 5 to 10 wt.% of the mixture, and several studies and reports indicate a noticeable reduction in rutting and bitumen savings at this dosage [69]. Laboratory and field studies in North America and Europe also show that the addition of ground tire rubber (GTR), PE/PP, and combined modifiers improves the strength, damping, and durability of asphalt layers [70].

Thus, global practice demonstrates that asphalt modification with polymers has moved beyond academic research and is increasingly applied in infrastructure projects.

4.1. Technological Approaches to Producing Polymer-Bitumen Composites

Two primary technological approaches exist for incorporating polymer additives into asphalt concrete—the so-called “wet” and “dry” processes—each with distinct physicochemical characteristics, advantages, and limitations. In the wet approach, modification is performed during bitumen preparation: the polymer (most often SBS, EVA, LDPE, less commonly PP or recycled thermoplastics) is introduced into heated bitumen at 160–190 °C with intensive shear mixing for 30–60 min [35]. Two interaction scenarios are possible: partial polymer dissolution in bitumen or formation of a stable dispersion, depending on solubility parameters and system viscosity. The resulting structure is either a finely dispersed emulsion with polymer droplets in a bitumen matrix or a continuous structure in which the polymer phase forms a spatial network, imparting increased elasticity and thermal stability. Rheologically, this manifests as an increase in complex modulus (G*) and a reduction in the loss tangent (tanδ), indicating enhanced elasticity and, practically, improved resistance to rutting at high temperatures [71].

The dry method, in contrast, involves the direct introduction of polymer particles into the asphalt mixture without prior dispersion in bitumen. Shredded thermoplastics (HDPE, LDPE, PP, PET) or rubber crumbs are added to the mixer together with heated mineral aggregates at 160–180 °C. The polymer particles partially melt, coating the surfaces of the aggregate or sand, forming a thin polymer layer that improves adhesion and water resistance.

The physical distinction between these methods primarily relates to heat and mass transfer mechanisms and component compatibility. In the wet process, polymer chains can diffuse into the low-molecular-weight bitumen phase, forming a partially dissolved structure, whereas in the dry process, interaction is limited to surface wetting and localized melting. Compatibility is determined by the proximity of Hansen solubility parameters (δD, δP, δH); the highest degree of dissolution is observed for elastomers and polyolefins with δ values close to those of bitumen (approximately 17–19 MPa1/2) [72]. For PET, which has high crystallinity and a melting point of ~250 °C, direct melting in bitumen is impossible—preliminary chemical or thermomechanical processing (glycolysis, pyrolysis) is required to achieve an amorphous state and produce low-molecular-weight fragments compatible with the hydrocarbon matrix [73].

Technologically, the wet method requires specialized equipment—high-shear mixers, thermostated tanks, and bitumen circulation systems—raising energy consumption and process costs. However, polymer-bitumen binders (PBB) produced by this method exhibit high stability, controllable rheological properties, and standardization potential according to international specifications (e.g., Superpave PG). These composites are predominantly applied in highways, airfield pavements, and other high-load facilities. An example is the use of SBS-modified bitumen in high-traffic pavements, where service life extends to 12–15 years compared to 6–8 years for standard asphalt [74].

The dry method, however, has proven especially popular in countries focused on local waste recycling and low capital costs. A typical example is the Vasudevan technology (India), in which shredded polyethylene or polypropylene is added directly to heated aggregates; the polymer partially melts, binding mineral grains to form a composite with improved water resistance and crack resistance [75]. Similar implementations exist in the UK, Netherlands, and Australia, where the use of 5–8 wt.% recycled plastic reduced rutting by 30–40% and increased asphalt concrete modulus by 20–25% [70]. Despite lower homogeneity and potential property variations, the dry method offers simplicity of implementation and effective utilization of secondary resources, making it promising for regions with limited technological infrastructure, including Kazakhstan.

A clear and practically relevant distinction must be made between the wet and dry routes for the incorporation of recycled polymers into asphalt systems, as each method leads to different performance outcomes, constraints, and long-term risks.

In the wet process, low-melting-point recycled plastics (commonly PE or PP) are molten and blended directly into hot bitumen under high shear, producing a modified bitumen binder prior to mixture production. Recent experimental work demonstrates that such wet-modified binders with plastic contents in the range of 2–6 wt% of the binder can enhance rutting resistance and stiffness of asphalt mixes, though higher dosages often result in decreased storage stability and increased risk of phase separation [76,77]. Studies report that with plastic contents above ~6%, gains in performance are offset by poor homogeneity and long-term durability issues [78].

Alternatively, the dry (or “aggregate-addition”) process introduces shredded or pelletized recycled plastic directly into the asphalt mixture—either as partial aggregate substitute or as mixture modifier—typically without attempting full dissolution in bitumen. This route is technologically simpler, more compatible with decentralized or lower-cost production facilities, and avoids binder-blend instability. For example, dry-process asphalt mixtures with waste polyethylene dosages in the order of 0.25–1.5 wt% of total mixture mass demonstrated comparable workability, moisture resistance, and improved stiffness or permanent deformation resistance compared to reference mixtures [79].

However, both methods carry the risk of surface hardening and reduced low-temperature or fatigue performance when polymer content (or plastic fraction) becomes excessive. Several studies note that too high a polymer fraction (for wet method) or too large plastic content (for dry method) leads to increased mixture brittleness, poor fatigue crack resistance, and moisture-sensitivity under freeze–thaw cycles or cyclic loading [80,81].

Based on available experimental evidence and to maintain a balance between mechanical improvement and long-term durability, practical upper limits for polymer addition are recommended as follows:

For the wet process: 2–6 wt% of binder mass.

For the dry process: ~1–2 wt% of total asphalt mixture mass (equivalent to ~4–6 wt% of the binder/bitumen proportion, depending on mix design).

These dosage ranges provide sufficient modification to enhance high-temperature performance and rutting resistance, while minimizing the risks of phase separation, surface hardening, and durability degradation under variable climatic and load conditions.

Given the simpler logistics and lower cost requirements, the dry-process route appears particularly suitable for deployment in regions with limited industrial infrastructure or decentralized production—for example, in many parts of Central Asia. Nevertheless, adequate quality control (e.g., particle-size distribution, plastic type selection, mixing temperature, moisture control) remains critical to ensure consistent pavement performance.

There are notable differences in the energy demand associated with wet and dry modification pathways. Wet processing requires high-shear milling at elevated temperatures and therefore adds an additional ≈72 MJ·t−1 of energy consumption per tonne of PMB, as documented in the Bitumen Life Cycle Inventory of the Refined Bitumen Association. For each ton of modified asphalt produced using the conventional wet process, an average of 121.67 kg of carbon dioxide (CO2) is emitted, alongside 605.0 kg of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), 58.0 kg of carbon monoxide (CO), and 490.0 kg of methane (CH4) [82].

Baseline plant energy use for producing asphalt mixture (heating and drying aggregates) is typically 320–390 MJ·t−1, and remains similar for both approaches [83]. In contrast, dry modification does not require high-shear reactors and thus adds little to the plant-level energy input; however, the off-site pre-processing of recycled plastics can be significant, with mechanical shredding reported between 15 and 180 kWh·t−1 depending on feedstock and equipment [84]. Additional CO2-equivalent emissions associated with wet milling have also been reported in industrial LCA case studies, typically on the order of 10–15 kg CO2-eq·t−1 PMB. Taken together, these values indicate that wet modification introduces a predictable process-integrated energy penalty, whereas dry modification shifts the energy burden to upstream plastic preparation stages. A comparative overview of the energy demand, emission contribution, and capital requirements associated with wet and dry polymer incorporation routes is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of energy consumption, emission footprint, and capital costs for wet and dry polymer incorporation methods.

The choice between wet and dry approaches depends on operational requirements, economic factors, and equipment availability. When predictable properties and high durability are required, the wet method is preferred; when priority is given to waste utilization and cost reduction, dry or combined approaches are advisable.

4.2. Modification of Asphalt Pavements

A major avenue for sustainable asphalt modification is the use of secondary polymers, such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and ground tire rubber (GTR) from end-of-life tires [85]. Incorporating these polymers into bitumen or the mixture alters mechanical and thermal properties: increasing stiffness and deformation resistance, while potential trade-offs include reduced low-temperature plasticity. The density, thermal conductivity, and heating behavior of recycled plastics are critical factors in optimizing the formulation of modified asphalt.

In addition to isotropic insoluble, partially soluble, and soluble polymers, fibers are frequently employed. These can be polymeric, such as non-melting cellulose [86,87,88] or high-melting polypropylene [89,90], or inorganic, such as glass fibers [91,92,93] or even carbon nanotubes [94,95,96]. Fibrous additives enhance the asphalt mixture structure, prevent bitumen drainage, increase fatigue resistance, and stabilize polymer particle distribution. When combined with polymers, a multicomponent matrix is formed: the polymer provides thermal stability and elasticity, while fibers confer structural stability and integrity under cyclic loading.

Contemporary formulations increasingly rely on complex granulometric filler systems: multimodal distributions of coarse, medium, and fine aggregates combined with polymer particles and fibers allow optimization of mixture density, minimization of porosity, and achievement of high mechanical strength and durability. This is especially important for pavements operating in climates with pronounced temperature fluctuations, such as the sharply continental climate of Kazakhstan, where temperatures can vary from −57 to +49 °C.

5. Biopolymer Modifiers for Asphalt-Bitumen Binders

In recent decades, there has been a steady increase in interest in using biopolymers and other biomaterials (such as lignin, bio-oil components, polysaccharides, protein fractions, etc.) as modifiers and/or extenders for bitumen binders. The reasons for this trend are manifold: the pursuit of a circular economy, reduction in the carbon footprint, availability of by-products from the pulp-and-paper and bio-manufacturing industries, and the potential to improve pavement performance. A synthesis of recent reviews and experimental studies indicates that biopolymers can exert a significant influence on the microstructure of bitumen, its rheology, and consequently, on rutting resistance, fatigue durability, and aging resistance of pavements [97,98,99].

Consequently, the modification of asphalt using biopolymers, such as lignin, has emerged as a key focus. Lignin is a naturally occurring biopolymer and a by-product of the pulp and paper industry. Its aromatic structure is similar to that of bitumen, and it exhibits antioxidant properties, which allow for enhanced aging resistance of the binder and adjustments of rheological parameters. Studies demonstrate that the incorporation of 3–5% lignin can increase stiffness and high-temperature deformation resistance while maintaining satisfactory low-temperature performance [100]. Moreover, at the laboratory scale, the addition of lignin has been actively investigated. Comparisons between mixtures containing 30% lignin and conventional asphalt mixtures show that lignin-containing binders reduce thermal sensitivity and age-related degradation while providing comparable strength and stability [97]. However, in terms of fatigue performance and workability, the addition of lignin may require formulation optimization to avoid deteriorating the mixture’s processability [101]. A recent study [102] demonstrated that bio-oil-lignin compositions (combining bio-oil and lignin) exhibit excellent storage stability and rheological properties.

5.1. Major Biopolymer Modifiers and Their Properties

Among the most studied biopolymers in the context of bitumen systems are some biopolymers:

Lignin (a by-product of the paper and biotechnological industries)—used as a modifier, antioxidant, filler/extender, and potential partial bitumen substitute. Extensive reviews and experimental studies indicate that lignin increases binder stiffness at high temperatures, enhances rutting resistance, and exerts a pronounced antioxidant effect, slowing thermo-oxidative aging [6,97].

In recent studies, the impact of lignin dosage on storage stability and long-term performance of bituminous binders has been carefully characterized, revealing both opportunities and limitations for its practical use. For instance, a comprehensive investigation demonstrated that composite binders modified with bio-oil and lignin remained stable after thermal storage at up to 165 °C for 48 h: the maximal softening point difference (top vs. bottom of storage container) was only 0.9 °C, and the calculated storage stability index (Is) remained below 0.1—indicating negligible phase separation even under prolonged heating [102].

However, when unmodified technical lignin or partially purified fractions with small molecular weight distributions are used, excess dosage may lead to inhomogeneity, aggregation or sedimentation during storage, which compromises binder homogeneity and thus service performance [103].

To mitigate these stability issues and improve compatibility of lignin with bitumen, several pretreatment methods have been proposed and successfully demonstrated. Among them: organosolv fractionation—which isolates lignin fractions with narrower molecular weight distribution and higher aromaticity; esterification (or oxyalkylation) of lignin to increase hydrophobicity; high-energy milling to achieve fine particle size (<10–50 µm); and pH neutralization/solvent washing to remove low-molecular-weight acidic or polar impurities. For example, a recent study reported that esterified lignin (PA-L) added at 5 wt% to an SBS-modified binder improved high-temperature stability, increased complex modulus, and preserved low-temperature crack resistance more effectively than unmodified lignin.

Similarly, using purified organosolv lignin fractions (e.g., fraction F4) yielded significant retardation of oxidative aging under PAV/UV protocols, with reduced formation of carbonyl and sulfoxide groups compared to neat bitumen [104].

Based on these data, a practical dosage window for lignin incorporation emerges: up to ~5–6 wt% appears acceptable for producing stable modified binders without significant risk of phase separation or poor workability, provided proper pretreatment and homogenization are implemented. Dosages exceeding this threshold should be accompanied by rigorous mixing protocols (e.g., high-shear blending at elevated temperature), or preferential use of pretreated lignin to ensure long-term storage stability, uniform dispersion, and acceptable rheological and aging behavior.

Polysaccharides: chitosan, cellulose (including micro- and nanocellulose), starch, and their derivatives. For example, chemically modified chitosan improves adhesion and provides some thermal stability; starch-based organic structures can form supramolecular networks within the bitumen matrix, exhibiting “anti-flow” behavior at elevated temperatures [105,106].

Bio-oils and plant-derived esters (rejuvenators/bio-oils)—primarily used to rejuvenate aged binders, but at specific dosages and in combination with polymers, they can adjust viscosity and fraction compatibility. Reviews of bioproduct rejuvenators highlight both their efficacy [107].

Other biopolymers (e.g., agar/alginate gels, protein fractions) are being investigated in pilot studies as potential structuring additives; although data are currently scattered, they suggest the possibility of achieving specific rheological effects by controlling molecular weight and surface chemistry [108,109].

The influence of biopolymers on bitumen rheology can be interpreted through three interrelated mechanisms:

Physical filling/dispersed phase formation — insoluble fractions (certain lignins, native cellulose, nonpolar structures) act as solid fillers, increasing effective modulus and reducing susceptibility to viscous deformation at high temperatures. This is reflected in increased complex modulus G* and decreased phase angle δ in DSR tests, positively affecting rutting resistance [110,111].

Certain biopolymer additives (e.g., functionalized lignin, carboxylated chitosan) engage in chemical interactions with heteroatomic components of bitumen (carboxyl, phenolic, etc.), forming adsorption/crosslinking sites that stabilize asphaltene-resin aggregates and slow their coagulation during heating/cooling. Such interactions are evidenced by changes in FTIR spectra and molecular weight shifts (GPC) after modifier incorporation [106,110].

Bitumen is an associative colloidal system; biopolymers can alter the balance between asphaltenes, resins, and the oil phase: either “binding” asphaltenes into more stable aggregates (enhancing stiffness) or acting as compatibilizers, improving dispersion of high-molecular-weight fractions (potentially improving low-temperature plasticity). These effects manifest in temperature-dependent modulus curves and changes in sample thixotropy [99].

To systematize the growing body of data on biopolymer-modified bituminous binders and to enable a comparative assessment of their functional roles, Table 2 summarizes the major classes of biopolymers currently investigated for asphalt modification, including their typical dosage ranges, dominant mechanisms of action, and the resulting rheological and performance-related effects. The table integrates results from recent experimental and review studies on lignin, polysaccharides, bio-oils, and emerging biopolymeric systems, highlighting both their technological advantages and practical limitations relevant to asphalt engineering applications.

Table 2.

Major Biopolymer Modifiers for Bitumen: Properties, Mechanisms, and Performance Effects.

5.2. Rheological Evaluation Methods and Observed Effects

Classical tools for evaluating the effects of biopolymer modifiers include: dynamic shear rheology (DSR—measuring G*, δ), Multiple Stress Creep and Recovery (MSCR—for ranking rutting resistance), Bending Beam Rheometer (BBR) and low-temperature creep/fracture tests—for assessing low-temperature brittleness, as well as cyclic fatigue tests (LAS/four-point bending) for predicting durability under repeated loading. Recent studies demonstrate the following typical observations:

Improved resistance to plastic deformation (rutting). Incorporation of 3–10% lignin (by binder mass) often increases G* and reduces δ in the high-temperature working range; MSCR-Jnr decreases (improved recovery). The effect depends on lignin type (organosolv, kraft, soda) and molecular weight [101,110].

Effect on low-temperature behavior and fatigue cracking resistance. A duality is observed: some lignin forms increase low-temperature brittleness (modulus rise at −18 to −30 °C), while optimal functionalization or combination with elastomers (SBS, CTR) maintains or even improves low-temperature performance and fatigue resistance. Experiments indicate that dosage and form are critical—excessive solid biopolymer fractions can reduce crack resistance [111].

Antioxidant and anti-wear effect. Lignin and certain polysaccharides exhibit antioxidant properties, slowing the formation of oxygen-containing functions in resins during thermo-oxidative aging—reflected in aging indices (CMAI, PAAI) and reduced stiffness growth after RTFOT/PAV processes [110].

In comparative terms, the most widely investigated biopolymers differ substantially in their functional roles and applicable conditions. Lignin is generally advantageous for high-temperature performance and aging resistance, yet its benefits are dosage-sensitive and strongly dependent on pretreatment; unmodified or low-molecular-weight fractions may induce phase instability or brittleness at excessive loadings. Polysaccharides primarily as structuring or adhesion-enhancing agents, improving high-temperature stiffness but sometimes increasing low-temperature modulus if introduced as coarse solid fractions; chemically modified polysaccharides show improved compatibility with bitumen. Bio-oils and ester-based rejuvenators improve low-temperature flexibility and restore aged binders but may reduce rutting resistance unless combined with elastomers or used within narrow dosage windows. Emerging biopolymers, such as alginate/agar gels or protein-based additives, show promising but still system-specific effects, where molecular weight distribution and surface chemistry determine whether they act as compatibilizers or as rigid structuring phases. Overall, these distinctions highlight that each biopolymer class operates within a specific domain of effectiveness, governed by compatibility, molecular architecture, and the targeted rheological response of the binder.

5.3. Practical Results for Mixtures and Pavements

Laboratory and pilot studies indicate that with careful selection of biopolymer type, pretreatment (chemical functionalization, fractionation), and dosage, bio-modified binders and mixtures can achieve competitive performance: equivalent or improved rutting resistance, comparable fatigue durability, reduced aging susceptibility, and potentially lower environmental footprint [97,101,111].

However, the literature notes several cautions:

- Different lignin types, chitosan sources, and starch polymerization degrees result in highly heterogeneous outcomes; standardization is currently lacking.

- Many biopolymer fractions are poorly soluble in the aromatic fraction of bitumen, forming phase-inhomogeneous composites. Use of plasticizers, functionalization, or combined systems (biopolymer + small percentage of petroleum polymer/plasticizer) is often required. [99]

- Some biopolymers decompose at temperatures typical for hot asphalt (160–180 °C), necessitating lower temperatures (WMA), pretreatment, or thermally stable biopolymer variants.

5.4. Current Limitations and Research Directions

For biopolymer modifiers to become industrially applicable, several scientific and technical challenges must be addressed:

- Standardization of raw materials and pretreatment methods (fractionation, purification, functionalization) is critical to reproduce rheological effects.

- Investigation of compatibility mechanisms at the molecular level (FTIR, GPC, NMR, MD simulations) to predict behavior in complex real systems; recent MD studies of rejuvenators demonstrate the potential of this approach [112].

- Optimization of production processes (use of WMA technologies, sequential addition regimes, combined modifiers) to prevent thermal degradation of biopolymers.

- Comprehensive field testing and LCA to evaluate long-term performance, the influence of climatic and operational factors, and actual environmental benefits.

Biopolymer modifiers represent a promising direction for sustainable modification of bitumen binders: lignin and several polysaccharides have shown the ability to improve high-temperature stiffness, reduce the rate of oxidative aging, and contribute to the circular economy. However, successful translation of laboratory successes to industrial practice requires raw material standardization, in-depth understanding of molecular compatibility mechanisms, and adaptation of production technologies. With careful coordination of these aspects, biocomponents can become a viable alternative or supplement to traditional polymer modifiers, particularly in regions with abundant biological feedstock.

6. Rheological and Structural Aspects of Composite Bitumens

The rheological properties of bituminous binders are a key mechanism through which the supramolecular organization of the material and its phase composition are translated into the macroscopic performance characteristics of pavement. Parameters measured in the laboratory (complex modulus G*, phase angle δ, non-recoverable creep compliance Jnr, recovery rate R%, cyclic fatigue according to LAS, etc.) directly correlate with rutting resistance, fatigue resistance, and susceptibility to low-temperature cracking in the field [113]. Furthermore, Jiang et al. [114] demonstrated that standard DSR parameters alone may under-predict binder softening after long-term aging, thus highlighting the importance of integrated rheological characterization. Therefore, a rigorous methodological framework for rheological measurement and interpretation forms a vital bridge between materials science and pavement engineering: without this bridge, laboratory results cannot reliably be translated into formulation requirements and service-life predictions [115]. Extensive reviews on the colloidal nature of bitumen [16] emphasize the role of rheology as an integrator of structural and performance data.

6.1. Interpretation of Key Parameters

DSR and MSCR parameters are used by practitioners as quantitative risk markers: high G* (and/or G*/sinδ) at elevated temperatures typically correlates with lower rutting susceptibility, while a low δ indicates a higher elastic component, positively affecting deformation recovery. However, unidirectional increases in stiffness carry the risk of reduced low-temperature crack resistance—a classical “stiffness vs. cracking” trade-off. [114] Jnr (MSCR) directly characterizes residual creep under a given load: lower Jnr and higher R% indicate better recovery and, consequently, higher resistance to plastic deformation in the field [116]. Meta-analyses indicate that Jnr and R% are significantly more sensitive to the type of polymeric/composite modifier than traditional DSR parameters [115].

For fatigue prediction, LAS/VECD parameters (cyclic stiffness, failure parameters) index binder durability under repeated loading. Collectively, these parameters form a “rheological passport” for the binder, essential for engineers when selecting formulations for specific climate and load conditions.

6.2. Influence of Composite Additives on Temperature Stability and Rheology

Composite additives—including polymers, rubber fractions, mineral and carbon-based nano-fillers, and biopolymers—modify bitumen rheology through multiple mechanisms: mechanical reinforcement (the filler acting as a solid phase), formation of a polymer network (such as SBS, EVA), surface chemical functionalization, and enhanced colloidal stabilization (resins acting as compatibilizers between asphaltenes and polymer). Empirical studies demonstrate that appropriately dispersed polymer fractions increase G* and reduce δ at high temperatures—improving rutting resistance; similarly, nanoparticle additives (SiO2, TiO2, CNTs) enhance stiffness and thermal stability via formation of a secondary structural network [117,118]. For example, Mielczarek et al. showed that even low levels (0.2%) of imidazoline in an SBS-modified binder improved low-temperature behavior without significantly degrading rutting performance [115]. However, an excess of rigid phase may reduce low-temperature ductility and accelerate crack formation under cyclic thermal loads [119]. A special group of modifiers includes biopolymers (lignin, modified celluloses), which, in addition to mechanical effects, provide antioxidant and compatibilizing properties: their addition can slow thermo-oxidative aging and shift the colloidal equilibrium, leading to more stable G*(T) master curves after aging [120,121]. Such modifiers typically require pre-chemical treatment and optimized laying conditions to avoid phase separation.

6.3. Rheology–Climate Correlation: Boundary Conditions for Central Asia

Climatic factors—including diurnal and seasonal temperature amplitudes, insolation/UV-exposure, humidity and freeze–thaw cycling—define rheological requirements for binders: namely resistance to plastic deformation at high temperatures (high G*, low δ, capacity for thermal stress-relaxation at subzero temperatures (low BBR modulus, favorable mmm-parameter), and structural stability under combined UV and thermo-oxidative action. In Central Asian contexts—characterized by high altitude, strong insolation and large diurnal temperature swings—it is imperative to develop “rheological passports” that include DSR, MSCR and BBR parameters specific to each climatic sub-region. Recent work [43] indicates that the key degradation predictors are not mean annual temperatures but rather maximum daily temperatures, diurnal amplitude and cumulative UV dose. Laboratory aging validation should accordingly include RTFOT/PAV aging plus UV and moisture cycling [122].

6.4. Practical Implementation of the “Climate Rheology Profile” Concept

The “Climate Rheology Profile” concept involves establishing target rheological metrics (e.g., G*(T) and δ(T) ranges, critical Jnr and R% under specified loads, BBR criteria) for each climatic zone, thereby guiding formulation and technological requirements. This profile is developed in three sequential stages: (1) climate analysis (Köppen–Geiger classification plus local meteorological data); (2) laboratory simulation of operational scenarios (combined thermal, UV and moisture cycling) with full rheological testing; (3) pilot field sections with monitoring of temperature, deformation, adhesion and corrosion. Implementing this methodology yields significant benefits in regions with marked climatic heterogeneity [113]. It is recommended to integrate combined modifications (polymer + nanofiller + antioxidant/UV stabilizer) and adapt technological regimes (e.g., Warm Mix Asphalt, additive sequencing) to align with the Zone-specific rheology profile. Composite bitumens are complex multiphase systems whose behavior is determined by the interplay of colloidal structure, chemical properties and additive interactions. Rheological methods (DSR, BBR, MSCR, LAS) combined with morphological and chemical analyses (SEM, AFM, FTIR) establish a reliable toolkit for scientifically grounded formulation design that is climate-specific. In Central Asia it is critical that binder and mixture development rely on zone-specific “rheological passports”, accounting for maximum temperatures, diurnal amplitude and UV load, while simultaneously integrating combined modifications and adapting technological regimes. Only an integrated approach—ranging from molecular-level structure and morphology analysis through to the finished pavement—enables durable, climate-adapted roads capable of withstanding extreme loads and significant climatic variations [16].

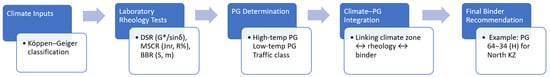

Figure 2 presents a conceptual decision-making scheme for climate-driven binder selection based on the proposed Climate Rheology Profile. The flowchart integrates climatic inputs derived from the Köppen–Geiger classification, pavement temperature extremes, freeze–thaw frequency, and traffic loading into a unified workflow for defining target rheological parameters. Through sequential interpretation of DSR, MSCR, and BBR criteria, the scheme provides a structured transition from climatic characterization to Performance Grade (PG) determination and final binder recommendation. Such an approach formalizes the otherwise fragmented selection process and ensures that materials are matched to the dominant degradation mechanisms of each climatic zone.

Figure 2.

A conceptual decision-making scheme for climate-driven binder selection based on the proposed Climate Rheology Profile.

The practical implementation of this framework is illustrated through two contrasting climatic regions of Central Asia, whose key parameters and corresponding binder requirements are summarized in Table 3. The cold continental zone (Northern Kazakhstan, Mongolia) is characterized by extreme winter temperatures down to −40 °C, high freeze–thaw cycling intensity, and a predominance of low-temperature cracking and moisture-related damage. Accordingly, the target binder class is PG 64−34 (H), with stringent requirements on BBR stiffness and m-value, moderate MSCR traffic levels, and emphasis on elastomeric and rubber-based modification strategies to secure low-temperature relaxation and crack resistance.

Table 3.

The quantitative climatic–rheological correlation.

In contrast, the hot semi-desert zone (Southern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan) is governed by extreme summer pavement temperatures above +70 °C, intense solar radiation, and accelerated oxidative aging. For these conditions, the Climate Rheology Profile shifts toward high-temperature stiffness, rutting resistance, and UV durability, resulting in a target PG 70−22 (V) classification. Elevated MSCR demands and reinforced antioxidant protection become decisive, while modification strategies prioritize high-temperature SBS systems, recycled plastics, and stabilizing additives. The combined use of the decision scheme (Figure 2) and the quantitative climatic–rheological correlation (Table 3) demonstrates the operational applicability of the Climate Rheology Profile for region-specific material design.

6.5. Example Box: Translating Rheological Metrics into PG (Kazakhstan North Zone)

To demonstrate the practical connection between rheological parameters and binder selection in climate-driven design, Table 4 summarizes representative DSR, MSCR, and BBR values and their interpretation within the Performance Grade (PG) system. The climatic conditions of northern Kazakhstan—where pavement temperatures may reach +64…+70 °C during summer and drop to −34…−40 °C in winter—require binders with high rutting resistance and adequate low-temperature flexibility.

Table 4.

Rheological criteria and corresponding PG thresholds.

In accordance with AASHTO M 320 and AASHTO M 332, the high-temperature grade is defined by DSR criteria (G*/sin δ ≥ 1.0 kPa for original binder and ≥2.2 kPa after RTFO), while traffic-loading categories are refined through MSCR (Jnr and recovery). Low-temperature performance is assessed via BBR, requiring stiffness S (60 s) ≤ 300 MPa and m-value ≥ 0.300 at the critical temperature after PAV aging. These thresholds are widely used in North America for climate-adaptive binder selection (FHWA-HRT-11-045; Asphalt Institute Binder Specification Guide 2021).

Assume a binder exhibits the following rheological properties:

- DSR (original): G*/sin δ = 1.35 kPa at 64 °C

- DSR (RTFO): G*/sin δ = 2.45 kPa at 64 °C

- MSCR: Jnr3.2 = 1.8 kPa−1, recovery R3.2 = 24%

- BBR (PAV-aged): S = 245 MPa, m = 0.315 at −34 °C

The DSR criteria satisfy the requirements for PG 64 high-temperature grade. The MSCR value of Jnr3.2 = 1.8 kPa−1 corresponds to the PG 64-H traffic category. The BBR data meet the low-temperature thresholds for PG −34

7. Experimental Approaches, Modeling, and Pilot Studies

The analysis of the durability and performance characteristics of road bitumens is based on a comprehensive set of laboratory tests aimed at investigating thermo-oxidative aging, photodegradation, moisture effects, freeze–thaw cycling, and structural and rheological changes. These methods are used to predict binder behavior under service conditions and to select optimal modifiers. Three main categories of bitumen testing can be distinguished: laboratory studies, modeling, and field trials.

7.1. Laboratory Studies of Road Bitumens

Thermo-oxidative aging is a key process governing the degradation of bitumen in asphalt pavements. Short-term aging is simulated using the Rolling Thin Film Oven Test (RTFOT, ASTM D2872 [127]), where a thin film of bitumen is exposed to hot air at 163 °C for 85 min, replicating the effects of mixing and laying. As an alternative, the Thin Film Oven Test (TFOT) can be used, although RTFOT is generally considered more reproducible and representative of real-world aging.

Long-term aging is modeled using the Pressure Aging Vessel (PAV, ASTM D6521 [128]/AASHTO R28 [129]), where RTFOT-aged samples are exposed to 2.1 MPa at 100 °C for 20 h, equivalent to several years of natural aging. After PAV treatment, the complex modulus and phase angle are measured using a DSR (AASHTO T315 [130]), while low-temperature stiffness and relaxation are determined by the BBR (AASHTO T313 [126]). The combined RTFOT + PAV procedure provides a comprehensive picture of both short- and long-term aging resistance [131].

During thermo-oxidative aging, viscosity and elastic modulus increase, while oxygen-containing functional groups form. FTIR spectroscopy detects these chemical changes, with characteristic carbonyl (≈1700 cm−1) and sulfoxide (≈1030 cm−1) bands serving as oxidation indices. ATR-FTIR is widely accepted as a reproducible tool for quantitative oxidation assessment, validated through interlaboratory comparisons [132,133,134].

Accelerated photoaging caused by ultraviolet radiation is another critical degradation mechanism. Laboratory xenon-arc or UV-fluorescent chambers replicate solar spectra under controlled temperature and humidity. UV exposure induces surface oxidation and bond cleavage (C–S, C–H), resulting in brittle films and reduced ductility [135]. Studies show that photoaging increases the carbonyl index more strongly than thermal aging, especially in surface layers [136].

In polymer-modified bitumens (e.g., SBS, EVA), UV radiation degrades the polymer phase, reducing elasticity as observed in Multiple Stress Creep and Recovery (MSCR, AASHTO T350 [137]) tests and FTIR spectra. Combining PAV + UV aging yields more realistic durability estimates than individual procedures [138].

Freeze–thaw cycling is crucial for regions with variable climates. The method involves saturating specimens with water and subjecting them to repeated freezing (−20 °C) and thawing (+20 °C), followed by evaluating strength, adhesion, and stiffness changes. For asphalt mixtures, this is defined in AASHTO T283 [139] (Modified Lottman Test) via the Tensile Strength Ratio (TSR). For neat bitumen, freeze–thaw testing is used to evaluate brittleness and BBR parameters [140].

Moisture sensitivity of bitumen and asphalt mixtures is assessed using AASHTO T283 or Hamburg Wheel-Tracking Test (AASHTO T324 [141]), which simulate water exposure under cyclic loading. TSR and rutting resistance data provide insight into adhesion loss under moisture. Additional measurements such as contact angle, surface free energy, and FTIR-based hydrolysis analysis complement binder testing [142,143,144].

Rheological tests form the backbone of bitumen characterization. The DSR (AASHTO T315 [130], ASTM D7175 [145]) measures G* and δ across temperatures to evaluate rutting and fatigue resistance, while MSCR (AASHTO T350) quantifies nonrecoverable compliance (Jnr) and percent recovery. These parameters underpin PG classification. Complementary methods (TGA, DSC, GPC, and GC-MS) are used to study volatility, molecular-weight distribution, and oxidation products [134].

In summary, modern bitumen analysis combines accelerated aging tests (RTFOT → PAV → UV) with mechanical, rheological, and spectroscopic measurements. The integrated use of DSR, MSCR, BBR, and FTIR provides predictive insight into performance and degradation mechanisms such as oxidation, polymer breakdown, volatilization, and moisture absorption. Incorporating freeze–thaw and water-sensitivity tests ensures that evaluations reflect actual climatic conditions.

The use of standardized methods (ASTM D2872, ASTM D6521, AASHTO R28, T283, T315, T350, T324) ensures cross-laboratory comparability. Together, these methods form a robust framework for assessing bitumen durability and environmental resistance, serving as the basis for developing long-life binders [66,132,135,136].

7.2. Field Studies of Road Bitumens and Pavements