Abstract

Due to their sustainability, lightweight qualities, and simplicity of installation, wood slab systems have gained increasing attention in the building industry. Cross-laminated timber (CLT), an engineered wood product (EWP), improves structural strength and stability, offering a good alternative to conventional reinforced concrete (RC) slab systems. Conventional CLT, however, contains adhesives that pose environmental and end-of-life (EOL) disposal challenges. Adhesive-free CLT (AFCLT) panels have recently been introduced as a sustainable option, but their environmental performance has not yet been thoroughly investigated. In this study, the environmental impacts of five slab systems are evaluated and compared using the life cycle assessment (LCA) methodology. The investigated slab systems include a standard CLT slab (SCLT), three different AFCLT slabs (AFCLT1, AFCLT2, and AFCLT3), and an RC slab. The assessment considered abiotic depletion potential (ADP), global warming potential (GWP), ozone layer depletion potential (ODP), human toxicity potential (HTP), freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity potential (FAETP), marine aquatic ecotoxicity potential (MAETP), terrestrial ecotoxicity potential (TETP), photochemical oxidation potential (POCP), acidification potential (AP), and eutrophication potential (EP), covering the entire life cycle from production to disposal, excluding part of the use stage (B2-B7). The results highlight the advantages and drawbacks of each slab system, providing insights into selecting sustainable slab solutions. AFCLT2 exhibited the lowest environmental impacts across the assessed categories. On the contrary, the RC slab showed the highest environmental impact among the studied products. For example, the RC slab had the highest GWP of 67.422 kg CO2 eq, which was 1784.3% higher than that of AFCLT2 (3.779 kg CO2 eq). Additionally, the simulation displayed that the analysis results vary depending on the electricity source, which is influenced by geographical location. Using the Norwegian electricity mix resulted in the most sustainable outcomes compared with Sweden, Finland, and Saudi Arabia. This study contributes to the advancement of low-carbon construction techniques and the development of building materials with reduced environmental impacts in the construction sector.

1. Introduction

Slab systems provide the main horizontal load-bearing platform in buildings and strongly influence a building’s weight, construction logistics, acoustics, thermal behavior, and overall environmental performance. Among available options, timber slabs, particularly cross-laminated timber (CLT), have gained traction because they are lightweight, install quickly, and can deliver competitive structural performance with favorable life cycle profiles compared with conventional reinforced concrete (RC) floors [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. As an engineered wood product (EWP), CLT offers improved stiffness and stability that enable multi-story applications while reducing foundation loads and site impacts [2,3,4,5,9,10]. Furthermore, timber’s ductility enhances the seismic performance of building structures, making it a suitable solution in earthquake regions [11,12]. At the same time, several practical issues shape material choices and detailing: moisture management, acoustic performance, and fire design typically require additional measures in timber buildings; in addition, the adhesives used in conventional CLT (e.g., PUR, MUF) introduce petrochemical inputs, potential emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) during production and processing, and challenges at end of life (EOL) related to recyclability and energy recovery [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Against a backdrop of decarbonization targets for the built environment, life cycle assessment (LCA) has become popular for comparing slab alternatives and informing design decisions that balance structural performance, constructability, and environmental outcomes [5,6,13,14,15,16,17,24,25,26].

Existing research provides valuable baselines for both material systems and assessment practice. LCAs of CLT in various supply chains and projects report relatively low embodied impacts compared with many mineral-based floors while showing sensitivity to species mix, logistics, and manufacturing energy [13,14,15,16,17]. Comparative studies of CLT and other EWPs (e.g., GLT) further disentangle trade-offs between environmental indicators and material quantities, demonstrating that design choices and adhesive formulations materially affect results [27,28]. At the structural-system level, studies emphasize that connectors, fasteners, and construction processes contribute non-negligibly to cumulative impacts and should be explicitly modeled in LCAs of timber buildings [29]. In parallel, a growing body of research is exploring “adhesive-free” concepts (such as timber-to-timber dovetailing and densified-wood/compressed dowels) to reduce dependency on petrochemical binders while maintaining acceptable stiffness, strength, and ductility [12,30,31]. These works demonstrate technical feasibility and provide mechanical data and preliminary design guidance for adhesive-free laminated timber (AFLT) beams and adhesive-free CLT (AFCLT) panels, though often without a full environmental benchmark against conventional CLT or RC under consistent system boundaries [12,30]. For RC floors, LCA evidence consistently highlights the burden of cement production, high mass (and thus transport/installation energy), and more limited recovery options at EOL, though mix design innovations and reinforcement recycling can moderate impacts [32]. Furthermore, recent city-scale and typology-wide evidence reinforces the value of partial CLT substitution at the envelope. An analysis of 52 apartment building types found that replacing concrete exterior walls with CLT reduced life cycle GHG by 44.6% and life cycle energy demand by 49.3%; per-floor reductions were −16,906 kg CO2-eq and −256,896 MJ, respectively [33]. Moreover, at the building-physics level, hybrid CLT envelopes in a humid summer climate showed robust moisture blocking from outdoors but sensitivity to indoor humidity, indicating the need for surface treatments/vapor control; operational energy differences versus high-mass RC were small, yet the LCA still reached up to 135.9 t CO2-eq savings over 40 years for hybrid CLT apartments [34].

Despite these advances, notable knowledge gaps remain for decision-making at the slab level. Firstly, there is a shortage of LCAs that compare multiple AFCLT embodiments (e.g., dowel-connected vs. milled dovetail variants) alongside a standard CLT and an RC reference within a single, harmonized framework, functional unit, and boundary set. Many CLT LCAs focus on “typical” adhesive-based layups and do not consider how adhesive-free geometries alter upstream wood demand (including machining waste), electricity needs for milling, or small but consequential adhesive quantities in finger joints [12,13,14,15,16,17,30]. Furthermore, EOL modeling for timber slabs is heterogeneous across studies: assumed reuse rates, incineration credits, and treatment of avoided burdens vary widely, making comparisons difficult and potentially obscuring the practical benefits of design for reuse in AFCLT concepts [15,28,35,36,37,38]. Moreover, several works acknowledge but do not systematically explore regional electricity-mix effects, even though process electricity (drying, sawing, CNC milling, and panel fabrication) can drive toxicity, aquatic ecotoxicity, and photochemical smog indicators—categories where differences between renewable-heavy and fossil-dominant grids are substantial [13,14,15,16,17]. Furthermore, construction-stage modeling (A4–A5) is frequently simplified, and mass-dependent site operations (cranage, handling) that differentiate timber and RC alternatives receive inconsistent treatment, which can bias comparative conclusions in practice [29,32,35,36]. Addressing these gaps requires a controlled comparison that varies the design concept while holding scope, data sources, and assumptions consistent.

This study corresponds to those needs with an LCA of five floor-slab systems: a standard CLT slab (SCLT), three adhesive-free CLT variants (AFCLT1–3 capturing dovetail-milled and dowel-connected approaches), and an RC slab. Using 1 m2 of slab (supporting a 2.5 kN/m2 live load over 50 years) as the functional unit, the work adopts cradle-to-grave system boundaries covering A1–A5, B1, C1–C4, and module D, and it applies CML midpoint indicators to ensure comparability across impact categories. Inventory modeling is implemented in SimaPro v9.4.0.3 with Ecoinvent v3.5 datasets, anchored in Swedish production and logistics assumptions and explicitly representing mass-dependent construction activities. The present article further conducts a location-sensitivity analysis by substituting Nordic and fossil-dominant electricity mixes to isolate grid effects. By benchmarking AFCLT variants against SCLT and RC under a uniform methodology (including transparent treatment of machining waste, minor adhesive usage in finger joints, and reuse/incineration scenarios at EOL), this research work clarifies: (i) how adhesive elimination and connection concept influence total impacts, (ii) where electricity sourcing dominates category outcomes, and (iii) the extent to which realistic reuse assumptions shift comparative rankings. The contribution is twofold: practically, it provides evidence-based guidance for architects and engineers seeking lower-carbon slab solutions without compromising constructability; scientifically, this article fills a comparative LCA gap for AFCLT systems, aligning scope and data choices so results can inform code development, procurement, and further AFCLT optimization.

2. Materials

Based on the goal of understanding the life cycle impact of various slab systems as a building component, five different slabs were chosen to evaluate and compare their sustainability through LCA. The selected SCLT and RC slabs are the most commonly used building slabs in the European market (also applicable in North America and East Asia). Moreover, the AFCLT slabs were selected due to the exclusion of resins. This section provides detailed information on the five studied slabs, including material properties, dimensions, and mechanical properties.

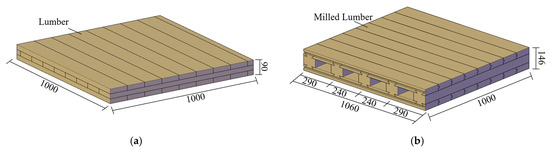

The SCLT slab (Figure 1a) is a prefabricated slab composed of PUR and lumber with finger joints. The slab consists of three lamella layers, each with a thickness of 30 mm. The SCLT slab has a maximum width and length (minor and major directions) of 3.45 m and 16 m [39,40]. The lamellas were assumed to be Scots pine, with a bond-dry density of 466 kg/m3 [41]. The moisture content was assumed to be 10% [41].

Figure 1.

Configurations of investigated slabs: (a) SCLT, (b) AFCLT1, (c) AFCLT2, (d) AFCLT3, and (e) RC slab (unit in mm).

AFCLT1 (Figure 1b) is an adhesive-free CLT that has developed a timber-to-timber dovetail connection between lamella layers [12]. The connection required milling work on the middle lamella layers and the outermost layers with the help of a CNC machine [42,43,44,45]. Meanwhile, the middle lamella layer was placed with a constant gap of 140 mm, which can be a convenient design for placing electronic cables and other things. The panel was made of Scots pine with a density of 500 kg/m3. Three lamella layers were included (total thickness of 146 mm), while the width and length were 1000 mm and 2500 mm, respectively. Extra groove-and-tongue connections were manufactured to connect lamella boards at the same layer (outermost layers only).

Moreover, AFCLT2 (Figure 1c) was developed and experimentally tested by Sotayo et al. [30], an adhesive-free CLT panel composed of dowel timber connectors. The dowel connectors were vertically inserted into the panels to connect the lamella layers. The connected AFCLT panel had dimensions of 600 mm × 60 mm × 1500 mm (width × depth × length), where the sawn lumbers were Scots pine (density of 556 kg/m3, moisture content of 10%, and thickness of 20 mm). The dowel connectors were made of beech with a radial hot-pressed procedure, which resulted in a density of 1300 kg/m3 and a moisture content of 5%. The dowels had a length of 60 mm and a section diameter of 10 mm. Furthermore, 2 dowels were employed in the panel per 13,225 mm2. The holes on the panels for dowel connectors were predrilled.

Additionally, AFCLT3 [46] (Figure 1d) is also an EWP slab design based on the exclusion of adhesives in CLT. AFCLT3’s design principle was built by using the dovetail edge connection between the lamella layer’s surface, similar to AFCLT1, but with different configurations. Moreover, internal gaps were not considered in AFCLT3, which makes it more intense. The panel had dimensions of 2500 mm × 120 mm × 5000 mm (width × depth × length), where each layer had a thickness of 40 mm (3-ply lamella). The applied wood species were assumed to be Scots pine with a density of 517 kg/m3 and a 10% moisture content.

The studied RC slab (Figure 1e) was taken from an LCA study by Demertzi et al. [32]. The RC slab had a thickness of 160 mm, where the top and bottom surfaces were flat. The employed concrete was class C25/30, where the density was 2500 kg/m3. Steel reinforcement A500NR was applied in two different dimensions: diameters of 8 and 10. The smaller reinforcements (⌀8) were placed in the upper part of the concrete (upper rebars) with a parallel distance (200 mm) between them. On the other hand, the other ⌀10 reinforcements (bottom rebars) were placed in the same manner but 100 mm vertically lower than the ⌀8 reinforcements. All reinforcements had a density of 10 kg/m2.

3. Methodology

LCA was employed in this study to evaluate the environmental impacts of the studied slabs. This section provides descriptions of the following: (1) life cycle assessment, (2) life cycle inventory, and (3) life cycle impact assessment. The contents cover the applied method, subjects, materials, life cycle phases, and necessary assumptions.

3.1. Life Cycle Assessment

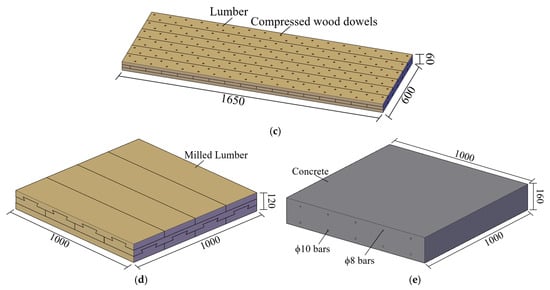

LCA is a well-known scientific method used to evaluate the environmental impact of products and activities across their whole life cycle. This work evaluated five structural slab systems by applying LCA with a cradle-to-grave approach. This study followed the recommendations developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), especially ISO 14040 [47] and ISO 14044 [48], so guaranteeing a consistent and valid analysis. The considered life cycle phases are depicted in Figure 2. It included the production stage (A1, A2, and A3: raw materials and manufacturing including drying/pressing and machining/CNC waste), construction stage (A4 and A5: mass-dependent transport and cranage/installation), use stage (B1), EOL scenario (C1, C2, C3, and C4), and benefits and loads (D1, D2, D3, and D4: demolition/deconstruction, reuse/recycling, incineration with energy recovery, and credited benefits). Parts of the use stage phases (B2-B7) were not considered in this study for the following reasons: (1) there was a limitation in data collection, and (2) the slabs require no maintenance, no energy during operation, and no water during use. The main inputs to the LCA study include the material ingredients, fuels, electricity, and resins. The production stage produced co-products since it involves milling of timber, but the co-products were excluded from this study. The standards EN15804 and EN15978 were followed accordingly [35,36]. This study considered several processes: resource extraction, manufacturing, component assembly, transportation, installation, use, deconstruction, and possible recycling or disposal routes. By concentrating on these features, this study seeks to provide a complete understanding of the environmental impacts of various CLT and RC slab systems.

Figure 2.

Life cycle phases, inputs, and outputs included in LCA of this study.

3.2. Life Cycle Inventory

The life cycle inventory of the different slabs was modeled by using the software SimaPro v9.4.0.3, ensuring the correctness and dependability of the evaluation. Furthermore, the data collection, calculations, and assumptions were set up mainly based on the Ecoinvent v3.5 database [37], experimental tests [12,30], standards [39], and relevant similar case studies [15,28,32,41,49]. Firstly, it was considered that producing 1 m3 SCLT requires 1.21 m3 of lumber as input [15]. As for the AFCLT1, -2, and -3, the input lumber’s volume was changed based on their surface area, volume, and waste volume. This is because the considered AFCLT required extra milling work, and the co-product (shavings 3.45%, finger joint waste 0.93%, CNC waste, and end cuts 12.8%) [13] volume will increase, which directly affects the input volume. Furthermore, it was assumed that an additional 6.44 kg of resin is necessary to produce 1 m3 of three-ply SCLT, including both the lamella layer surface (majorly used) and the finger joint (minorly used) [15]. Therefore, AFCLT1, -2, and -3 do not contain resin for the lamella surface but for the finger joint, where the resin volume was calculated based on the volume of applied lumbers in AFCLT compared to SCLT. Furthermore, the electricity source was considered only from Sweden, where the data (electricity contribution from different energy types) were adapted from Ecoinvent and Statens energimyndigheten 2023 [50]. The amount of electricity used varies among the studied slab systems based on the required cutting area compared with SCLT. Additionally, electricity sources from other Nordic countries (Finland and Norway) were also employed in scenarios comparing the effects from different locations through the Ecoinvent database.

The production location of CLT-related slab systems was assumed to be at Ljusne (Sweden), and the location of the RC slab was assumed to be at Heby, Sweden. The construction site was considered to be located in Stockholm, representing distances from the CLT factory and RC factory to the construction site of 242 km and 138 km, respectively. In addition, the distance in the waste disposal scenario was assumed to be 150 km for all investigated slab systems.

In the construction stage (A5), a telescopic boom crawler crane TKE750G (produced by Kobelco, from Lelystad, The Netherlands) [49,51] with 254 kWh of engine power was assumed to be used for lifting slabs on site. The consumed energy was calculated based on each slab’s weight (Table 1) compared with the crane’s lifting capacity.

Table 1.

Materials and inputs of slab systems.

At the EOL phase, the CLT-related slab systems were assumed to be 80% reuse and 20% incineration [28]. Meanwhile, the RC slab was considered for demolition with the help of a stone-crushing machine, about which there was information in the Ecoinvent database, and the separated concrete was sent to landfill, while the reinforcement was 75% recycled [28]. The environmental impact of the reused material will be counted as negative values for the total results (reduction). In SimaPro, the recycled materials were defined as avoided materials, which erased the production’s environmental impact of the same new material. Therefore, the negative values from the reused material are calculated based on its production’s environmental impacts.

3.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

Examining the environmental impacts of the flooring systems compared in this study was performed in the next step, the “life cycle impact assessment (LCIA)”. In this step, the acquired inventory data from the previous stage, the life cycle inventory, is converted into significant environmental impact indicators, enabling a thorough knowledge of possible environmental loads. In this study, the applied functional unit in the LCA of buildings is one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years. Impact assessment in this work employed the characterization factors advised by the Centre of Environmental Science (CML) [52], including abiotic depletion potential (ADP), GWP, ODP, human toxicity potential (HTP), freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity potential (FAETP), marine aquatic ecotoxicity potential (MAETP), TETP, photochemical oxidation potential (POCP), acidification potential (AP), and eutrophication potential (EP). The characterization factors (CFs) were used for converting elementary flows to kg CO2-eq in the model, where CO2, fossil = 1.0; CH4 = 28.0; N2O = 265.0; it also contains CO2 to soil/biomass stock = −1.0 and CH4, biogenic = 28.0. The same method and version were applied to all systems for comparability. In addition, the CFs of all environmental categories are available in the Supplementary Table S1. By applying these standardized indicators, this LCIA provides detailed insight into the environmental performance of the five flooring systems, comparisons, and decision-making guidelines for sustainable building design.

3.4. Energy Sources from Different Geographical Locations

The influences of geographical location were analyzed by changing the electricity source (originally set as the Swedish electricity mix) in Ecoinvent. The simulations were adapted to be in Finland, Norway, and Saudi Arabia. The different locations and attached electricity sources were chosen based on these points: (1) most selected countries (Sweden, Norway, and Finland) are geographically close to each other but have different energy resources and portions, (2) these four countries covered most of the commonly used energy resources, which forms a corresponding comparison, and (3) Saudi Arabia was chosen because it contains purely non-renewable energy resources. In Norway, the majority of electricity contribution was from hydropower (87.39%) and minorly from wind power (3.82%). As for Sweden, hydropower’s contribution dropped to 39.86%, while nuclear power (34.5%) and wind power (15.47%) were the second and third most significant contributors. In Finland, nuclear power, hydropower, wind power, and hard coal had contributions to the electricity production of 28.61%, 14.72%, 7.61%, and 5.12%, respectively. Finally, Saudi Arabia’s electricity mix was mainly based on oil (50.69%) and natural gas (49.3%). This modification and comparison aimed to understand the differences in environmental impacts due to regional factors. The other variables in the models were not modified as they represent European values or global values. However, the transportation distance impacts from geographical location were not included in this report. It is because this report tends to examine the influence of different electricity mixes and isolate the distraction from other factors.

4. Results and Discussion

This section presents analyses of the environmental impact results for the five slab systems studied, based on the following topics: (1) total environmental impacts, (2) environmental impact of different life cycle phases, and (3) the effect of the locations of the wood slab systems’ production on environmental impact. The results for each slab system are discussed in terms of their performance, data values, and causes. Meanwhile, they are also compared with each other. The conclusions are summarized, and the most sustainable slab system for the building sector is presented.

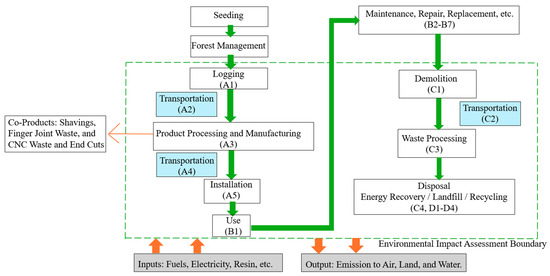

4.1. Environmental Impacts

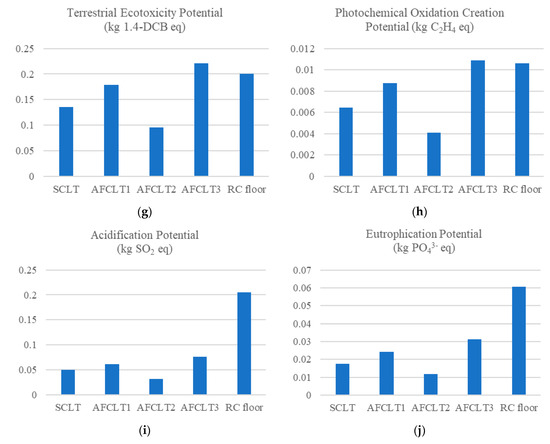

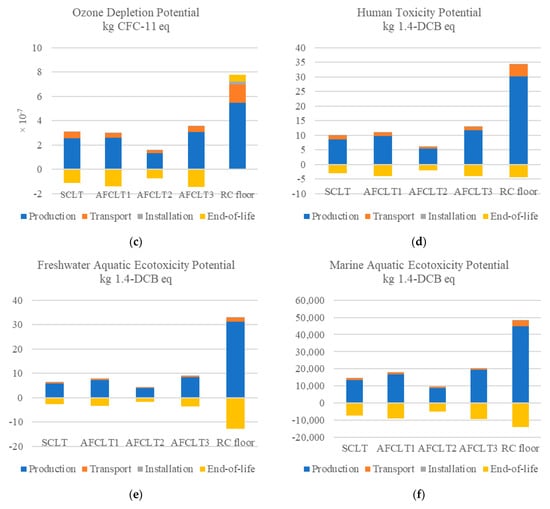

Table 2 depicts the total environmental impact of the five slab systems investigated, which contains ten impact categories. In each category, the slab system with the lowest value was compared with other slab systems, which resulted in a percentage difference. It was observed that the RC slab had the highest negative impact on the environment among the five studied slab systems based on most impact categories, except for TETP and POCP. It was caused by multiple factors, such as: (1) the production of non-renewable materials with high embodied carbon (concrete and steel), (2) the waste materials also emitted, and (3) the RC slab’s weight, which was far over that of the wooden slab and which consumed more resources from all weight-related activities (transportation, installation, and deconstruction). It indicated that the RC slab was the most unfavorable option in this study. In most categories, RC’s environmental impacts were far beyond the wooden slab systems in most impact categories (519–1784.3%). The exceptions are TETP and POCP, partly due to the contribution from the wood-ash mixture in waste treatment and wood-sawing procedures. As for the RC slab, the major contributor to TETP and POCP was still concrete production. It showed that the RC slab had lower TETP and POCP than the wooden slab (AFCLT3). On the contrary, the waste management of wooden slabs should be improved by the following: (1) limiting the amount of incineration or (2) improving the treatment of wood ashes after incineration. Furthermore, the difference in environmental performance between the RC slab and the wooden slabs could be reduced by: (1) improving the design to control the weight of the RC slab, and (2) using greener types of concrete. As for the wooden slabs, SCLT’s results were lower than those of AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 in most categories except for ADP and ODP. This was because of the production of PUR, where SCLT contained much more than AFCLT. Meanwhile, sawn wood board production also contributed to ADP and ODP, but AFCLT had a higher mass of board inputs than SCLT. It indicated that the ADP and ODP caused by extra board input (or higher wood density) were comparable to those from PUR, which showed similar levels of impact. This phenomenon was one of the main reasons that made AFCLT’s impact values lie close to that of SCLT in all categories. Among the wooden slabs (Figure 3), AFCLT2 consistently performed better due to: (1) its simplicity of milling work, (2) its exclusion of adhesives, and (3) its lesser amount of board and connector inputs in production. Therefore, AFCLT2 was the most sustainable slab system based on the total impacts in all categories (ADP: 2.401 × 10−5 kg Sb eq; GWP: 3.779 kg CO2 eq; ODP: 8.249 × 10−8 kg CFC-11 eq; HTP: 4.078 kg 1.4-DCB eq; FAETP: 2.360 kg 1.4-DCB eq; MAETP: 4472.192 kg 1.4-DCB eq; TETP: 0.095 kg 1.4-DCB eq; POCP: 0.004 kg C2H4 eq; AP: 0.031 kg SO2 eq; and EP: 0.012 kg PO43− eq).

Table 2.

Total environmental impacts of studied slab systems (per functional unit: one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) based on LCA.

Figure 3.

Total environmental impact of five slab systems (SCLT, AFCLT1, AFCLT2, AFCLT3, and RC) per functional unit (one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) for following categories: (a) ADP, (b) GWP, (c) ODP, (d) HTP, (e) FAETP, (f) MAETP, (g) TETP, (h) POCP, (i) AP, and (j) EP.

Among the wooden slab systems, the main factors that contributed to each impact category are concluded as well. The production of sawn wood (lumber) was the biggest contributor that influenced GWP, which was related to the amount of wood material inputs as well as its density. Both sawn wood mass and PUR affected HTP the most, which is similar to ADP and ODP. However, HTP values from AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 (7.068 kg 1.4-DCB eq and 9 kg 1.4-DCB eq) were higher than that of SCLT, which was the opposite of the comparison with ADP and ODP. This contrast highlighted that the contribution of lumber’s mass was higher in HTP than that of ADP and ODP. Moreover, the use of electricity was the major factor in impacting the FAETP, outweighing diesel and transport in the CLT production occasions. The electricity was applied mainly to produce CLT and for specific milling work regarding AFCLT slabs. Therefore, AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 were less preferred than AFCLT2 (179.1% and 230.4% higher, respectively) because they consumed more electricity on extra milling as their designs were more complex. The MAETP impact was mainly caused by sawn wood production, PUR, and transportation. Furthermore, it was noticed that incineration and raw material extraction affected AP and EP mostly. Hence, the performance of AP and EP of the wooden slabs was positively related to their final product mass, where the heaviest wooden slab AFCLT3 (56.1132 kg) achieved the highest values of 0.076 kg SO2 eq and 0.031 kg PO43− eq, respectively.

Furthermore, AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 illustrate a clear trade-off between design complexity and environmental performance. Their complex milling and higher lumber input raise production-stage burdens and electricity demand, which especially amplify FAETP and related categories, whereas their adhesive-free concept reduces resin-related concerns (e.g., HTP/ODP from PUR) seen in SCLT. AFCLT3 also carries substantially higher mass per m2 (≈55.9 kg) than AFCLT2 (≈30.0 kg), which increases transport- and mass-linked impacts but can increase EOL recovery credits because credits scale with mass. Thus, complexity can bring functional/structural benefits (e.g., robust mechanical interlocks) while shifting impacts toward electricity from production and sawn wood use.

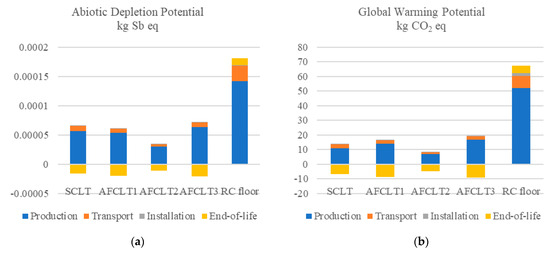

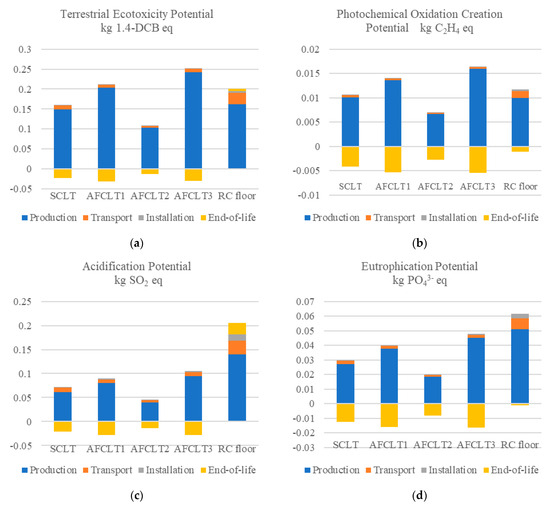

4.2. Contribution Summary of Life Cycle Phases

Based on the perspective of life cycle phases, the total environmental impact of the studied slab systems came from the production, construction, use, transportation, and EOL phases. The studied materials have no impact during their use stage, as they are prefabricated and have no activities considered during use (no surface treatment or maintenance). Therefore, the impact of their use stage was negligible. In addition, carbon sequestration was not accounted for in this study [38]. The impact contributions from each phase based on the considered impact categories are summarized in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The production phases were the top contributor to the environmental impact of all slab systems among all categories. This contribution was significantly higher than the other phases in each slab system based on their total impacts: SCLT (110.05–181.34%), AFCLT1 (113.07–192.45%), AFCLT2 (108.22–196.68%), AFCLT3 (109.80–177.17%), and RC slab (67.97–153.24%). It was noticed that the production phases showed relatively higher values in GWP, FAETP, MAETP, POCP, and EP. Furthermore, the production phase of the RC slab had lower impacts than some of the wooden slabs (SCLT, AFCLT1, and AFCLT3) based on TETP and POCP. The TETP and POCP impacts of the production phase from the RC slab and the AFCLT3 (with the highest value) were 0.1623 kg 1.4-DCB eq, 0.242 kg 1.4-DCB eq, and 0.00996 kg C2H4 eq, 0.01592 kg C2H4 eq, respectively. This difference was one of the main reasons that the RC slab’s total impact was lower among these two categories. Among the wooden slab system’s production phases, AFCLT2 depicted the lowest impacts of all categories, while AFCLT3 obtained the highest. The sustainability behavior in production from the AFCLT1 and SCLT were similar, while both slabs had higher impacts than AFCLT2 in all categories. Within most of the studied categories, it was observed that the top five contributors (production phase only) to SCLT, AFCLT1, and AFCLT3 were sawn wood production, PUR, electricity, board bonding, and waste wood treatment. However, the top five contributors from AFCLT2 were sawn wood production, electricity, PUR, board bonding, and waste wood treatment. It illustrated that although AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 excluded adhesives for lamella layers, the adhesive used in finger joints was still an obvious amount. This was caused by the fact that they had a higher lumber input than the production of AFCLT2. Since AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 had more complicated designs, they require higher amounts of lumber for milling. However, the milling of AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 also produced larger amounts of co-products, such as CNC milling waste, shavings, and end cuts. Except for design improvement, there are other recommendations for reducing the impact of using larger amounts of lumber input:

Figure 4.

Environmental impact of five floor systems (SCLT, AFCLT1, AFCLT2, AFCLT3, and RC) across the four assessed life cycle phases, presented per functional unit (one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) for following categories: (a) ADP, (b) GWP, (c) ODP, (d) HTP, (e) FAETP, and (f) MAETP.

Figure 5.

Environmental impact of five floor systems (SCLT, AFCLT1, AFCLT2, AFCLT3, and RC) across four assessed life cycle phases, presented per functional unit (one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) for following categories: (a) TETP, (b) POCP, (c) AP, and (d) EP.

- (1)

- The co-product could be reprocessed and used as structural timber. In this case, the wood inputs could be reduced as well as the environmental burden from the production.

- (2)

- The cutting waste could be recycled, which helps with recovery.

- (3)

- The cutting waste could be used for producing heat in the production phase. This approach could reduce the need for fuel in the machining of production.

Across phases, AFCLT1/3 concentrate their added burdens in A1–A3 due to extra sawn wood input and CNC milling electricity. The mentioned co-products from these designs can mitigate impacts if valorized (e.g., reprocessing to structural elements or on-site energy). Conversely, their greater mass improves absolute EOL recovery credits when reuse/energy recovery is modeled, but this does not fully offset the higher A1–A3 burdens. The net effect is that design complexity increases production-stage impacts while offering larger, but still secondary, credits at EOL.

- Main drivers: These include sawn wood and electricity for milling in A1–A3 (AFCLT1/3 > AFCLT2).

- Mass effect: AFCLT3 with the highest mass led to larger EOL credits but higher transport/production impacts.

Furthermore, it was perceived that RC slabs had no recovery capacity compared with the other wooden slabs in their EOL phases across most categories (ADP, GWP, ODP, TETP, and AP), which showed that the RC slab’s EOL phase only increased the total impact of those mentioned categories. This was caused mainly by the treatment of waste concrete and its transportation in the EOL phase. On the contrary, the wooden slabs could be partially recycled into structural timber (80%), which reduced the total impact. This recovery phenomenon was noticed in all conducted impact categories in this study. However, the recovery influences varied among wooden slabs. It was perceived that AFCLT3 had the highest recovery capacity in all categories, while AFCLT2 had the lowest absolute value from the EOL phase. Meanwhile, AFCLT1 had similar but lower values than AFCLT3 from the EOL phase in all categories (around 4%), while that of SCLT was even lower than AFCLT1 (around 20%). This is because the wooden slab’s recovery capacity was linked to the recycled structural timber’s mass. Since the recycling percentage was fixed for CLT-based slabs, the product with a heavier weight was aligned with a higher recovery ability. Therefore, density matters across phases. Variability in softwood density affects both performance and impacts: higher density raises A1-A3 (slightly more drying/machining per m2) and A4 (heavier transport) while also increasing biogenic carbon stored per m2 and the corresponding release at EOL (C3-C4) and potential energy-recovery credits in D. Performance-wise, density correlates with modulus of elasticity and connection capacity, so stiffer/stronger panels can, in some designs, improve material efficiency. In our fixed-geometry comparison, these effects partly offset each other, but density remains a key parameter. However, this does not mean that the slab system should be designed as heavily as possible, for these reasons: (1) the EOL phase was not the biggest contributor to the total impact, and (2) the product mass could affect the other phases as well. Furthermore, the EOL phases had different ratios of effect on different impact categories. It was shown that the EOL phase had a relatively higher contribution in GWP (85.02–122.99%), ODP (55.39–90.84%), FAETP (65.2–80.28%), MAETP (86.39–108.77%), POCP (50.27–67.97%), and EP (52.68–71.65%). Among the wooden slab systems, these results exhibited the following: (1) the EOL phase had a more significant impact on these phases specifically, and (2) the other phases were less important in GWP, ODP, FAETP, MAETP, POCP, and EP. As for the rest of the categories, the contribution was significantly lower. This phenomenon was found to be similar to that of the RC slab. Compared with the wooden slab systems, the EOL phase of the RC slab depicted a consistently low percentage of total impact among all categories (2.91–62.55%). Two reasons explain this phenomenon: (1) the other phases contributed massively, and (2) the RC slab had no recovery ability in the EOL phase among most impact categories. Although the reinforcement of the RC slab can be partially recycled, the waste concrete performed higher absolute values than that of reinforcement in most categories. It indicated that the treatment of waste concrete was the major issue of the EOL phase. It could be improved as: (1) by limiting the mass of concrete, (2) by using greener concrete, and (3) by increasing the reuse and recycling of concrete. Furthermore, the RC slab presented recovery ability in HTP, FAETP, MAETP, and POCP, which indicated that the effects of reinforcement recycling outweighed those of the waste concrete treatment. Furthermore, these findings indicated that the total environmental impact of wooden slab systems would increase without counting the EOL phase. The EOL phase considered that 80% of the wood elements will be transformed into structural timber and reused in the building industry, which were calculated as negative values to the total impact results. As for the RC slab system without the EOL phase, part of the category’s value will be decreased (ADP, GWP, ODP, TETP, and AP).

In addition, the transportation and installation phases occupied the smallest portion of the total impact across all categories and slab systems. This was because (1) in this LCA, the installation and transportation were carried out by a simple procedure on the site, (2) both procedures’ energy consumption was mainly mass-based, and (3) all manufacturers and EOL locations were assumed domestically. However, the main fuel used in the equipment and vehicles was diesel. These two phases could be further improved by switching to renewable energy with a lower environmental impact, such as renewable electricity from wind power. Moreover, it was observed that the transportation and installation were responsible for a relatively smaller percentage of environmental impact for all slab systems among FAETP, MAETP, TETP, and POCP. It illustrated that those categories were less linked to the consumption amount of diesel than the other categories.

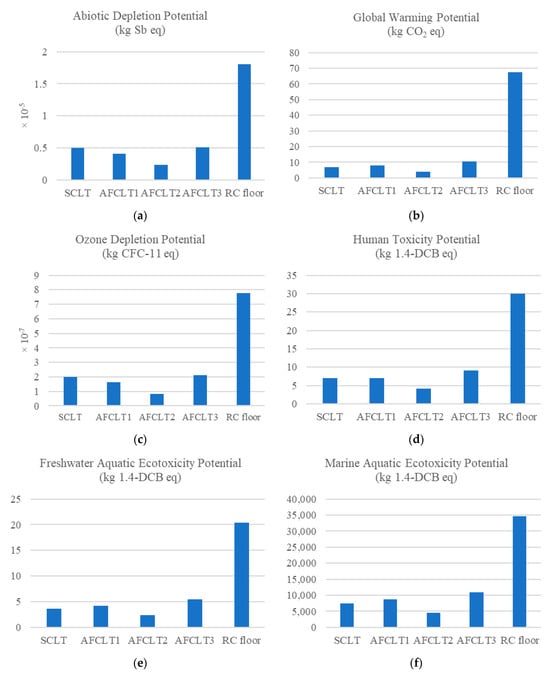

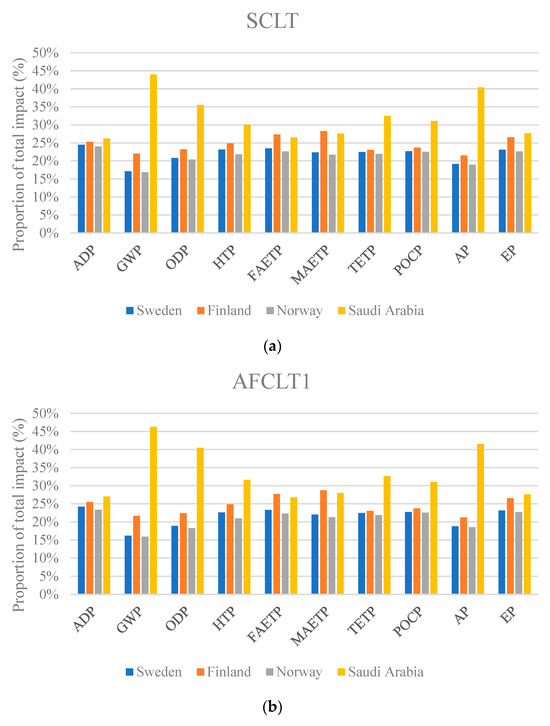

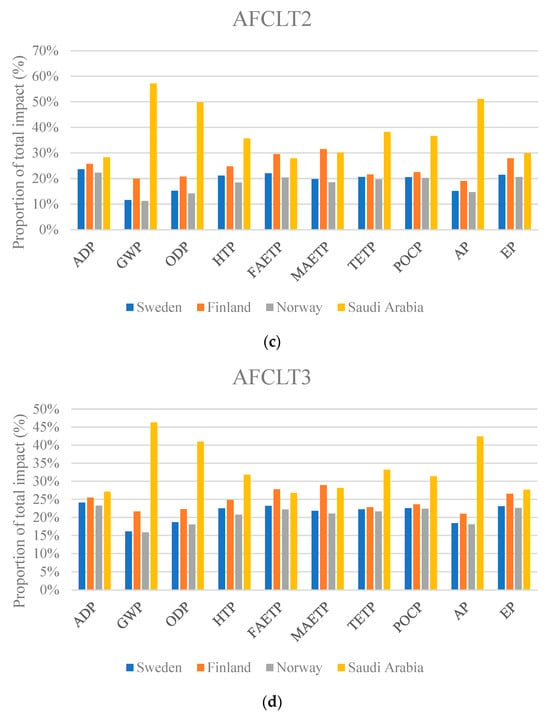

4.3. Influences of Geographic Location and Regional Electricity Source

Presented in Figure 6 is the country-specific environmental impact performance for locations in Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Saudi Arabia across multiple impact categories through LCA. The impact of each country’s electricity source was compared with the total impact across all four countries, and the comparisons resulted in percentages in Figure 6. The included categories were the same as those in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2. The comparisons and analyses were collected separately based on each slab system. It was noticed that most of the categories (ADP, TETP, POCP, and AP) showed relatively close ratios across the four countries. Therefore, the rest of the categories with significant differences were analyzed and presented.

Figure 6.

Environmental impact proportions of five slab systems (SCLT, AFCLT1, AFCLT2, AFCLT3, and RC) across different regions (based on relationship between impact of location and that of total for all locations), per functional unit (one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years): (a) SCLT, (b) AFCLT1, (c) AFCLT2, and (d) AFCLT3.

It was noticed that the reasons for the differences in impact between different regions were based on the resources for generating electricity. In general, Norway consistently demonstrated the lowest environmental impact across all categories, making it the location with the most favorable electricity source in terms of reducing emissions and environmental burdens. Saudi Arabia, with its electricity sourced from non-renewable sources, showed the highest values in most categories, indicating a comparatively higher environmental footprint. Sweden and Finland’s impact values generally lay between those of Norway and Saudi Arabia, with a moderately higher amount over Norway but still significantly lower than Saudi Arabia in most cases. The slab systems produced in Sweden performed relatively better than those in Finland in all categories. Meanwhile, it was noticed that the regional factor had obvious impacts on the categories of GWP, ODP, MAETP, TETP, POCP, and AP, which meant those categories had a major contribution from the use of electricity sources. Among these four countries, Saudi Arabia was the only country that consumed fossil oil as the main source for producing electricity. The produced electricity was 50.69% based on oil, and the rest of the electricity was generated by using natural gas. Consequently, the sustainability performance of Saudi Arabia in this study was extremely high compared with other regions based on GWP (43.97–49.81%), ODP (35.54–49.81%), HTP (30.09–35.63%), TETP (32.59–38.19%), POCP (31.03–36.62%), and AP (40.40–51.18%). It was also noticed that FAETP and MAETP were the only two categories in all slab systems from Saudi Arabia that performed better than those in Finland. This illustrated that FAETP and MAETP received the least impact from electricity sources among all wood slab systems.

Table 3 and Table 4 depict the detailed emission values of each wooden slab system based on the four countries. It was discovered that the environmental performance relationship between each wood slab remained the same under different electricity sources, where AFCLT2 and AFCLT3 showed the lowest and highest impact values among all categories, respectively. This is because each studied category received an impact contribution from electricity, and the source of electricity was the only modified variable. However, the difference between slab systems also changed when different electricity sources were applied. For example, SCLT had 189.44% higher GWP than AFCLT2 based on electricity from Norway, and the differences were lower in Sweden (185.59%), Finland (139.2%), and Saudi Arabia (96.98%). The explanation for this phenomenon is that the electricity’s impacts from high environmental impact sources were increased, which outweighed the influence of other factors. Therefore, the environmental impact difference between slab systems was more significant when a greener electricity source was employed, which decreased in the order of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Saudi Arabia.

Table 3.

Total environmental impacts of SCLT and AFCLT1 (per functional unit: one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) based on LCA of different countries.

Table 4.

Total environmental impacts of AFCLT2 and AFCLT3 (per functional unit: one square meter of slab structure (floor area), supporting a live load of 2.5 kN/m2 over 50 years) based on LCA of different countries.

Among the countries studied, electricity was produced from mixed sources, and the types and percentages used were far different. This showed that the overall environmental impacts could be reduced by: (1) excluding the use of fossil fuels in electricity production and (2) improving the percentage of using renewable energy sources, such as hydropower, wind power, etc.

4.4. Environmental Risk Evaluation: Likelihood–Impact and Acceptability

Beyond midpoint LCIA scores, the environmental risks for key hotspots were further assessed as the combination of the following: (1) the likelihood that a scenario or condition occurs in practice and (2) the impact magnitude if it does occur. This complements Section 4.3 by showing how scenario realism interacts with consequence.

The used scales and bands are stated below:

- Likelihood (L): 1 very unlikely, 2 unlikely, 3 possible, 4 likely, 5 very likely.

- Impact (I) (relative to the best performer in each category, per functional unit over study period):

- 1 negligible (<+5%), 2 minor (+5–20%), 3 moderate (+20–50%), 4 major (+50–150%), 5 severe (>+150%).

- Risk classification uses R = L × I: Low (1–5), Medium (6–10), High (11–15), Very High (16–25).

The risk is clarified based on the following conditions of acceptability: Low (1–5), acceptable with routine monitoring; Medium (6–10), tolerable only with documented controls; and High/Very High (11–25), not acceptable, where risk reduction is required prior to adoption.

Moreover, the evaluated aspects include: (1) electricity-mix sensitivity (drivers of GWP, HTP, and POCP), (2) resin/VOC emissions (HTP/ODP; SCLT only), (3) EOL incineration and ash handling (TETP/POCP for timber), (4) reuse not realized (lost credits affecting GWP/AP/EP), and (5) baseline GWP burden.

According to Table 5, AFCLT2 showed the most robust profile, with all risk scores in the Low–Medium range. AFCLT3 and SCLT displayed High or Very High risks for manufacturing electricity and EOL incineration and ash. Moreover, RC exhibited a Very High risk for the baseline GWP category. For each slab type, the table reports the selected L and I scores together with the resulting risk score R = L × I and its band (Low, Medium, High, Very High), so that lower R values correspond to more robust solutions.

Table 5.

Results of environmental risk evaluation: a summary of likelihood (L) × impact (I) = risk classification (R).

Likelihood ratings were assigned based on observed convenience and difficulties (e.g., feasibility of low-carbon electricity mixes, implementation of reuse and recycled material, or improved resin controls). At the same time, impact scores were derived from the relative differences in LCA results compared with the best-performing slab in each category (Section 4). In this way, the overall ranking is based on both the R values and classifications, with AFCLT2 the preferred option and AFCLT3 and RC requiring further risk reduction.

5. Limitations

The limitations of this study are multifaceted. First, the analysis was conducted at the floor-slab scale, representing only one component of a complete building system. Consequently, potential interactions between floors and other structural or non-structural elements, such as walls, columns, and building services, were not studied. Second, the scope was limited to CLT-related products, excluding other EWPs such as glulam or laminated veneer lumber (LVL), which may exhibit different environmental profiles and structural characteristics.

Third, carbon sequestration effects were excluded to avoid uncertainties related to service life, EOL scenarios, and carbon storage duration. While this ensures a conservative approach, it may underestimate the potential climate benefits of timber-based systems. However, stored biogenic carbon can be reported as a negative flow in A1–A3 with release at EOL (C3–C4) and potential credits in module D. By including stored biogenic carbon, it would lower A1–A3 GWP for all CLT/AFCLT options relative to RC (which has no biogenic pool). The benefit scales with wood mass (and thus density), so higher-mass variants (e.g., AFCLT3) would gain more than lighter ones, narrowing (but not necessarily overturning) the ranking in this study. Over a 100-year horizon, net GWP can approach neutral if stored carbon is fully released. However, reuse/cascading can prolong storage and displace carbon-intensive materials or fuels, amplifying climate benefits already captured in module D. This mechanism does not affect non-climate midpoints, and its visibility depends on choices such as static vs. dynamic LCA and reporting conventions.

Fourth, the geographic scope was limited to a few regions, which means that the results would differ from those in other parts of the world. Fifth, sensitivity and uncertainty analysis were not included in this article but could be a potential future topic. Furthermore, the current study does not evaluate functional performance domains, such as heat transfer and thermal behavior (e.g., conductivity, heat storage, airtightness), acoustics (airborne and impact sound insulation, damping), or fire performance (e.g., charring, fire resistance, ignition). Moisture/hygrothermal behavior and durability (e.g., creep, fatigue), vibration, serviceability, and indoor-air emissions are likewise outside the scope.

Future work should therefore combine LCA with function-based evaluations under an equivalent framework, in which each slab alternative should meet the defined performance targets (e.g., U-value or dynamic thermal criteria; R_w/L_n,w for acoustics; REI rating or char-ring-based resistance for fire; natural frequency/acceleration limits for vibration; moisture safety and durability checks; VOC/aldehyde emission limits). Within those constraints, comparative LCA can identify the environmentally preferable design. Methodologically, this refers to: (1) LCA simulations combined with building-physics, fire, and structural-serviceability analyses and (2) scenario/sensitivity analyses for performance-based assumptions (e.g., cavity infills, overlays, connectors, coatings, and electricity mixes). Additionally, the recycling phase was modeled by assuming that recycled wood products would be reused in equivalent applications, and that concrete and steel would follow standard recycling rates. These assumptions are based on common values in the case study but are not the only possibilities in real-life applications and may vary between contexts and projects.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study used LCA methodology to evaluate the environmental performance of five structural slab systems: SCLT, AFCLT1, AFCLT2, AFCLT3, and RC slab. The results showed large differences in environmental performance between the different slab systems in the studied impact categories (ADP, GWP, ODP, HTP, FAETP, MAETP, TETP, POCP, AP, and EP) through the LCIA method CML.

- Across 10 CML midpoint categories and five slab systems (SCLT, AFCLT1–3, RC), AFCLT2 showed the lowest total impacts overall, while RC ranked highest in 8/10 categories (exceptions: TETP and POCP).

- Per 1 m2 slab over 50 years, AFCLT2 consistently performed the best with the results as: ADP 2.401 × 10−5 kg Sb eq; GWP 3.779 kg CO2-eq; ODP 8.249 × 10−8 kg CFC-11 eq; HTP 4.078 kg 1.4-DCB eq; FAETP 2.360 kg 1.4-DCB eq; MAETP 4472.192 kg 1.4-DCB eq; TETP 0.095 kg 1.4-DCB eq; POCP 0.004 kg C2H4 eq; AP 0.031 kg SO2 eq; EP 0.012 kg PO43− eq.

- RC recorded substantially higher absolute impacts, including GWP 67.422 kg CO2-eq, AP 0.205 kg SO2 eq, and FAETP 20.409 kg 1.4-DCB eq, defining it as the worst option in this study set.

- Relative to AFCLT2, RC was higher by +1784.3% (GWP), +655.8% (AP), +864.9% (FAETP), +774.9% (MAETP), and +943.5% (ODP); even the smallest observed gap among major categories remained large (e.g., EP +519.0%).

- Compared with AFCLT2, SCLT showed GWP 7.013 kg CO2-eq (+85.6%), with similar uplifts for HTP (+70.0%), FAETP (+53.7%), and MAETP (+66.8%), attributable mainly to PUR use and higher electricity/material burdens.

- Within the adhesive-free group, AFCLT1 and AFCLT3 underperformed AFCLT2; versus AFCLT2, FAETP increased by +79.1% (AFCLT1) and +130.4% (AFCLT3), and AP increased by +100.7% for AFCLT3—linked to greater lumber inputs and milling electricity.

- Life cycle phase breakdowns showed production (A1–A3) dominated totals for all systems (typical stacked contributions ~110–197% of totals when including negative EOL credits), especially for GWP, FAETP, MAETP, POCP, and EP; A4–A5 were consistently minor.

- End-of-life assumptions (timber: 80% reuse, 20% incineration) produced negative credits whose magnitude scaled with mass (AFCLT3 > AFCLT1 > SCLT > AFCLT2). RC, modeled with concrete to landfill and ~75% steel recycling, received limited benefit and often increased totals.

- Electricity-mix sensitivity showed that relocating identical timber models from Norway to Saudi Arabia markedly raised impacts (e.g., AFCLT2 GWP: from 3.65 to 18.58 kg CO2-eq), with the strongest effects in GWP, ODP, HTP, TETP, POCP, and AP.

- RC was not the highest in TETP and POCP; certain timber scenarios (notably AFCLT3) exceeded RC in these categories due to wood-ash handling and milling electricity, although RC remained the highest in headline categories (GWP, AP, FAETP, MAETP, ODP).

- The main drivers for timber systems were sawn wood mass/density, PUR content (when present), and process electricity; design complexity that increases milling area and board input shifted burdens to A1–A3 and elevated toxicity-related indicators.

- Replacing RC slabs with CLT-based slabs (preferably AFCLT2-type designs) can yield large, quantified reductions at the slab level; further reductions are achievable by minimizing adhesives (including finger joints), reducing lumber mass via geometry optimization, and sourcing low-impact electricity.

The findings and conclusions of this research can serve as a foundation for recommending further improvements to wood slabs or the development of new designs.

7. Outlook

Future research should focus on further optimizing AFCLT designs, exploring fastening techniques, and integrating these solutions into large-scale building applications to promote sustainable construction. In addition, as highlighted in the Limitations section, future work should combine environmental assessment with systematic evaluations of thermal, acoustic, fire, durability, vibration, serviceability, and indoor-air performance, ensuring that environmentally preferable slab systems also meet functional criteria within an equivalent framework.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/infrastructures10120346/s1. Table S1—The characterization factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; methodology, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; validation, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; formal analysis, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; investigation, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; data curation, H.R., M.W. and A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, H.R.; writing—review and editing, H.R., A.B., M.W. and M.C.; visualization, H.R., A.B. and M.W.; supervision, A.B., M.W. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the University of Gävle for funding this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jayalath, A.; Navaratnam, S.; Ngo, T.; Mendis, P.; Hewson, N.; Aye, L. Life Cycle Performance of Cross Laminated Timber Mid-Rise Residential Buildings in Australia. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Vall, A.; Khalaf, A. Comparison of Cross-Laminated Timber and Reinforced Concrete Floors with Regard to Load-Bearing Properties. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 1395–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Jakobsson, J.; Söderroos, T. Factors Influencing Choice of Wooden Frames for Construction of Multi-Story Buildings in Sweden. Buildings 2023, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Edås, M.; Magnenat, K.; Norén, J. The Behavior of Cross-Laminated Timber and Reinforced Concrete Floors in a Multi-Story Building. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2022, 9, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte, A.M. Mass Timber—The Emergence of a Modern Construction Material. J. Struct. Integr. Maint. 2017, 2, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotayo, A.; Bradley, D.; Bather, M.; Sareh, P.; Oudjene, M.; El-Houjeyri, I.; Harte, A.M.; Mehra, S.; O’Ceallaigh, C.; Haller, P.; et al. Review of State of the Art of Dowel Laminated Timber Members and Densified Wood Materials as Sustainable Engineered Wood Products for Construction and Building Applications. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Ringaby, J.; Crocetti, R.; Debertolis, M.; Wålinder, M. Testing and Analysis of Screw-Connected Moment Joints Consisting of Glued-Laminated Timbers and Birch Plywood Plates. Eng. Struct. 2023, 290, 116356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Crocetti, R.; Wålinder, M. In-Plane Mechanical Properties of Birch Plywood. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techlam, N.Z. Advantages & Benefits of Glulam. Available online: https://techlam.nz/about/advantages-benefits-of-glulam/ (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. Experimental Validation and Simplified Design of an Energy-Based Time Equivalent Method Applied to Evaluate the Fire Resistance of the Glulam Exposed to Parametric Fire. Eng. Struct. 2022, 272, 115051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Bahrami, A.; Cehlin, M.; Wallhagen, M. Performance of Innovative Adhesive-Free Connections for Glued-Laminated Timber under Flexural Load. Structures 2024, 70, 107904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baño, V.; Moltini, G. Experimental and Numerical Analysis of Novel Adhesive-Free Structural Floor Panels (TTP) Manufactured from Timber-to-Timber Joints. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Dodoo, A. Cross-Laminated Timber for Building Construction: A Life-Cycle-Assessment Overview. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puettmann, M.; Sinha, A.; Ganguly, I. CORRIM Report—Life Cycle Assessment of Cross Laminated Timbers Production in Oregon; American Wood Council: Buffalo, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Puettmann, M.; Sinha, A.; Ganguly, I. Life Cycle Energy and Environmental Impacts of Cross Laminated Timber Made with Coastal Douglas-Fir. J. Green Build. 2019, 14, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Chen, C.X.; Pierobon, F.; Ganguly, I.; Simonen, K. Life Cycle Assessment of Katerra’s Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) and Catalyst Building: Final Report; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Pierobon, F.; Chen, C.X.; Simonen, K.; Ganguly, I.; Blomgren, H.E. Life Cycle Assessment of a Vertically-Integrated Cross-Laminated Timber Supply Chain. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering 2021, WCTE 2021, Santiago, Chile, 9–12 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Yusof, N.; Md Tahir, P.; Lee, S.H.; Khan, M.A.; Mohammad Suffian James, R. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Cross-Laminated Timber Made from Acacia Mangium Wood as Function of Adhesive Types. J. Wood Sci. 2019, 65, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Gašparík, M.; Sethy, A.K.; Kytka, T.; Kamboj, G.; Rezaei, F. Bonding Performance of Mixed Species Cross Laminated Timber from Poplar (Populus nigra L.) and Maple (Acer platanoides L.) Glued with Melamine and PUR Adhesive. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 106159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Yan, L.; Ning, T.; Wang, B.; Kasal, B. Behavior of Adhesively Bonded Engineered Wood—Wood Chip Concrete Composite Decks: Experimental and Analytical Studies. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 247, 118578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.B.; Wei, P.; Gao, Z.; Dai, C. The Evaluation of Panel Bond Quality and Durability of Hem-Fir Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT). Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2018, 76, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Lee, H.M.; Lee, M. Evaluation of Adhesive Characteristics of Mixed Cross Laminated Timber (CLT) Using Yellow Popular and Softwood Structural Lumbers. J. Korean Wood Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, N.M.; Cai, Z.; Carll, C. Wood-Based Composite Materials: Panel Products, Glued-Laminated Timber, Structural Composite Lumber, and Wood-Nonwood Composite Materials. In General Technical Report FPL–GTR–190; Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, H.; Bahrami, A.; Cehlin, M.; Wallhagen, M. A State-of-the-Art Review on Connection Systems, Rolling Shear Performance, and Sustainability Assessment of Cross-Laminated Timber. Eng. Struct. 2024, 317, 118552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Bahrami, A.; Cehlin, M.; Wallhagen, M. Literature Review on Development and Implementation of Cross-Laminated Timber. In Proceedings of the COBEE 2022, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–29 July 2022; Concordia University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vogtländer, J.G.; Van Der Velden, N.M.; Van Der Lugt, P. Carbon Sequestration in LCA, a Proposal for a New Approach Based on the Global Carbon Cycle; Cases on Wood and on Bamboo. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasbaneh, A.T.; Sher, W. Comparative Sustainability Evaluation of Two Engineered Wood-Based Construction Materials: Life Cycle Analysis of CLT versus GLT. Build. Environ. 2021, 204, 108112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighnavard Balasbaneh, A.; Sher, W.; Yeoh, D.; Koushfar, K. LCA & LCC Analysis of Hybrid Glued Laminated Timber–Concrete Composite Floor Slab System. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 49, 104005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukić, I.; Premrov, M.; Passer, A.; Žegarac Leskovar, V. Embodied Energy and GHG Emissions of Residential Multi-Storey Timber Buildings by Height—A Case with Structural Connectors and Mechanical Fasteners. Energy Build. 2021, 252, 111387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotayo, A.; Bradley, D.F.; Bather, M.; Oudjene, M.; El-Houjeyri, I.; Guan, Z. Development and Structural Behaviour of Adhesive Free Laminated Timber Beams and Cross Laminated Panels. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 259, 119821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Structure Craft Dowel Laminated Timber—The All Wood Panel—Mass Timber Design Guide. Available online: https://structurecraft.com/blog/dowel-laminated-timber-design-guide-and-profile-handbook (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Demertzi, M.; Silvestre, J.; Garrido, M.; Correia, J.R.; Durão, V.; Proença, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Alternative Building Floor Rehabilitation Systems. Structures 2020, 26, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, B.; Chang, S.J.; Wi, S.; Kim, S. Estimation of Energy Demand and Greenhouse Gas Emission Reduction Effect of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Hybrid Wall Using Life Cycle Assessment for Urban Residential Planning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 185, 113604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, S. Carbon Reduction and Hygrothermal Performance of Mid- and High-Rise Hybrid CLT Buildings as Residential Apartments. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 73, 106626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15804:2012+A2:2019; Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. CEN European Committee for Standardisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN 15978:2011; Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method. CEN European Committee for Standardisation: Brussels, Belgium, 2011.

- Frischknecht, R.; Rebitzer, G. The Ecoinvent Database System: A Comprehensive Web-Based LCA Database. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A. Contribution of Timber Buildings on Sustainability Issues. In Proceedings of the World Sustainable Building 2014, Barcelona, Spain, 28–30 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Erol, K.; Brad, D. CLT Handbook: Cross-Laminated Timber; FPInnovations: Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Forest Products Laboratory (US). Wood Handbook, Wood as an Engineering Material; Forest Products Laboratory (US): Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.X.; Pierobon, F.; Ganguly, I. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) Produced in Western Washington: The Role of Logistics and Wood Species Mix. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Gattas, J. Structural Behaviors of Integrally-Jointed Plywood Columns with Knot Defects. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2021, 21, 2150022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockwer, R.; Brühl, F.; Cabrero, J.M.; Hübner, U.; Leijten, A.; Munch-Anderssen, J.; Ranasinghe, K. Modern Connections in the Future Eurocode 5—Overview of Current Developments. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering 2021, WCTE 2021, Santiago, Chile, 9–12 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, T.; White, G.; Dowdall, A.; Bawcombe, J.; McRobie, A.; Steinke, R. Dalston Lane—The World’s Tallest CLT Building. In Proceedings of the WCTE 2016—World Conference on Timber Engineering, Vienna, Austria, 22–25 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tannert, T. Improved Performance of Reinforced Rounded Dovetail Joints. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 118, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilgın, H.E.; Karjalainen, M. Preliminary Design Proposals for Dovetail Wood Board Elements in Multi-Story Building Construction. Architecture 2021, 1, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. The International Standards Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Al-Najjar, A. Full Life Cycle Assessment of a Cross Laminated Timber Modular Building in Sweden. Master’s Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scenarier Över Sveriges Energisystem 2023; Statens Energimyndighet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2023.

- Kobelco Construction Machinery Co., Ltd. TKE750G Telescopic Boom Crawler Crane. Available online: https://www.kobelco-europe.com (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Guinee, J.B. Handbook on Life Cycle Assessment Operational Guide to the ISO Standards. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).