Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of dietary fermented Chinese herbal waste compound (FCHW, comprising fermented stems and leaves of Astragalus membranaceus, Rheum tanguticum, and Bupleurum chinense) on the growth, digestive function, antioxidative capacity, and non-specific immunity in juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish were randomly assigned to one of three dietary treatments for 45 days: a basal diet (control), a basal diet supplemented with 1% Chinese herbal waste (CHW), and a basal diet supplemented with 1% FCHW. The results showed that, compared to the control group, dietary FCHW significantly enhanced weight gain rate (WGR), specific growth rate (SGR), hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px), and hepatic non-specific immune parameters (ACP and AKP activities) of M. salmoides on both day 30 and day 45 (p < 0.05) except CAT activity on day 30. FCHW supplementation also significantly increased intestinal villus height, width, and muscularis thickness at both time points (p < 0.05). However, intestinal digestive enzyme activities (trypsin, lipase, and amylase) were elevated significantly only on day 30 relative to the control (p < 0.05). Dietary CHW showed limited efficacy. Compared to the control group, dietary CHW supplementation significantly improved intestinal lipase activity and hepatic SOD activity on day 30 (p < 0.05). By day 45, dietary CHW supplementation significantly increased intestinal morphology (villus height, width, and muscularis thickness) (p < 0.05). These results indicate that fermentation enhances the bioactivity of CHW, thereby supporting the potential of FCHW as a functional feed additive in aquaculture.

Keywords:

fermented Chinese herbal waste; Micropterus salmoides; growth; digestive function; antioxidative capacity Key Contribution:

Dietary FCHW enhanced fish growth, intestinal digestive function, hepatic non-specific immune parameters, and antioxidative capacity.

1. Introduction

Aquaculture is the fastest-growing food-producing sector in the world. Growing safety concerns over the consumption of aquatic products have led to stricter regulations on the use of medicinal chemicals in aquaculture. As a result, Chinese herbal medicines (CHMs) are gaining prominence as an alternative, giving rise to the concept of “green medicine” [1]. CHMs are rich in various bioactive molecules, which can enhance feed conversion efficiency, accelerate growth performance, and improve the quality of aquatic products. Furthermore, they also exhibit significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, thereby enhancing the immune competence and disease resistance of cultured species [2]. To optimize CHM bioavailability, fermentation, a bioprocessing technique utilizing specific microorganisms or their metabolic enzymes, is employed under defined aerobic/anaerobic conditions [3]. During CHM fermentation, probiotics and CHs establish a mutually beneficial relationship. CHMs promote probiotic proliferation, and probiotics enhance the bioavailability of CHM components. Consequently, fermented preparations of CHMs typically exhibit superior effects compared to using either CHMs or probiotics alone [4].

Herbs typically consist of various plant parts, including leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds, stems, wood, bark, roots, and rhizomes, each possessing distinct medicinal properties. During processing, non-medicinal and low-medicinal components in herbs are routinely discarded, generating substantial amounts of herbal waste [5]. The domestic production of Chinese herbal medicine reached approximately 2.5 million tons in 2021, with this manufacturing process concomitantly producing an estimated 60–70 million tons of herbal wastes annually [6]. Traditional waste management approaches such as landfill disposal, incineration, and uncontrolled stockpiling pose risks of environmental contamination. Therefore, it is of great significance to make rational use of these Chinese herbal wastes and achieve their value-added transformation.

Largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), native to North America, has become a key species in Chinese freshwater aquaculture owing to its broad environmental adaptability, fast growth, manageable husbandry requirements, and short production cycle [7]. In 2024, the production of M. salmoides in China reached 880,000 tons. However, the intensive and large-scale aquaculture practices have led to recurrent issues such as growth retardation and hepatointestinal diseases in M. salmoides, which are the main factors restricting the sustainable development of its farming [8].

Astragalus membranaceus, Rheum tanguticum, and Bupleurum chinense are essential bulk medicinal materials in CHMs. However, their aboveground parts (stems and leaves), being low-medicinal components, are typically discarded as processing byproducts. In this study, stems and leaves from compound A. membranaceus, R. palmatum, and B. chinense were fermented by Bacillus subtilis isolated from shrimp pond sediment. The raw herbal waste and its fermented product were supplemented into the basal diet of M. salmoides, and their effects on fish growth performance, hepatic antioxidative capacity, hepatic non-specific immunity, and intestinal digestive function were investigated, aiming to establish a theoretical foundation for the utilization of fermented Chinese herbal wastes in aquaculture practices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Experimental Diets

The stems and leaves of A. membranaceus, R. palmatum, and B. chinense were provided by Jiu Feng Ecological Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Zhuoni, China). The herbal waste materials were dried, crushed, and passed through a 60-mesh sieve, followed by sterilization via high-temperature and high-pressure treatment before being dried again. The dried powders of A. membranaceus, R. palmatum, and B. chinense were mixed in a mass ratio of 5:4:1 to prepare the Chinese herbal waste compound (CHW). For fermentation, the CHW was reconstituted with sterile water at a solid–liquid ratio of 1:2 (w/v) and inoculated with B. subtilis (viable count ≥ 3.51 × 108 CFU/g). The mixture was fermented in an incubator at 31 °C for 72 h, followed by final drying. Quantitative analysis revealed that the total polysaccharide contents in CHW and fermented Chinese herbal waste compound (FCHW) were 2.54 mg/g and 38.3 mg/g, respectively. Viable count of B. subtilis in FCHW reached 1.37 × 109 CFU/g [9]. CHW and FCHW were stored at 4 °C until further use.

The granular basal diet was commercially obtained from Shandong Haibo Agricultural and Animal Husbandry Science and Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China) (nutritional composition presented in Table 1). Prior to feeding, CHW and FCHW were incorporated into this diet through uniform blending.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of the basal diet.

2.2. Experimental Design

The experiment was carried out at the Recirculating Aquaculture System Laboratory at Tianjin Agricultural University. Juvenile largemouth bass (M. salmoides) were obtained from a rearing facility in Jinan, Shandong Province, China. Prior to the experiment, fish were reared in recirculating aquaculture tanks (71.4 cm × 42.8 cm × 50.2 cm) and fed the basal diet for 7 days to acclimate to the experimental conditions.

After acclimation, a total of 180 fish with an initial mean body weight of 11.08 ± 0.25 g were randomly divided into 3 groups, with 3 tanks per group and 20 fish per tank. Nine tanks were connected to a closed recirculating system comprising three independent units. Each dietary treatment was assigned to a separate unit (containing three replicate tanks) to create hydraulically isolated environments and thereby prevent any cross-contamination of water microbiota between treatments. All units were supplied with water from the same source and maintained under identical environmental conditions and management protocols to minimize any unintended systematic variation. Three groups were fed: (1) a basal diet (control group), (2) basal diet supplemented with 1% CHW (CHW group), and (3) basal diet supplemented with 1% FCHW (FCHW group). The inclusion level of 1% was chosen based on results from the preliminary dose-finding trial, which showed that 1% was the optimal supplementation level for promoting growth performance. The fish were fed their respective diets until apparent satiation twice daily, with daily feed intake carefully monitored and recorded. The feeding trial lasted for 45 days, and water temperature was maintained at 24–26 °C, pH at 6.5–7.5, and dissolved oxygen at 6.0–7.0 mg/L.

2.3. Sample Collection

On day 30 and again at the end of the experiment (day 45), fish were sampled following an identical protocol. After a 24 h fast, fifteen fish were randomly selected from each treatment group, corresponding to five fish per replicate tank. The selected fish were anesthetized with Eugenol (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Shanghai, China) and weighed. Liver tissues were excised and weighed. For subsequent biochemical analyses, the livers from all five fish within the same replicate tank were pooled to form one composite sample (n = 3 per group). Similarly, a segment of the hindgut (approximately 1.5 cm anterior to the anus) was collected from each fish was fixed separately in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for histological examination. For biochemical analyses, the left intestinal segments from the five fish in a replicate were also pooled into one composite sample (n = 3 per group). All composite samples for biochemistry were immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

2.4. Growth Performance Measurement

Growth performance was calculated according to the following formulae:

where Wt and W0 are the final and initial body weight, respectively, t is the experimental duration, and Wf is the diet consumed. N0 and Nt represent the initial and final fish number, respectively. Wg and Wd represent the hepatopancreas weight and fish weight, respectively.

Weight gain rate (WGR, %) = ([Wt − W0]/W0) × 100

Specific growth rate (SGR, %) = ([lnWt − lnW0]/t) × 100

Feed coefficient rate (FCR) = Wf/(Wt − W0)

Survival rate (SR, %) = Nt/N0 × 100

Hepatopancreasomatic index (HI, %) = (Wg/Wd) × 100

2.5. Enzymatic Activity Assays

Approximately 1 g of liver or intestine sample was homogenized in 9 mL of ice-cold physiological saline (1:9 w/v) using a homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was aliquoted for various enzyme assays. All aliquots were stored at 4 °C and analyzed within 24 h.

Enzyme activities were measured using commercial assay kits (Jiancheng Biotech, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Total protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method [10] using bovine serum albumin as the standard. One unit of amylase activity hydrolyzed 10 mg of starch in 30 min at 37 °C. One unit of trypsin activity caused a change in absorbance of 0.003/min using N-benzoyl-L-arginine ethyl ester hydrochloride substrate at 37 °C (pH 8.0). Lipase activity was determined according to Li et al. [11] with olive oil as substrate. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity were measured according to Zhang et al. [12] and Trenzado et al. [13], respectively. Catalase (CAT) activity was determined using the method of Aebi [14] in which the initial rate of hydrogen peroxide decomposition was determined. Malondialdehyde (MDA) level was determined using the method of Dogru et al. [15]. Both acid phosphatase (ACP) and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activities were determined using a colorimetric method [16].

2.6. Intestinal Histology Observation

Fixed intestinal samples were dehydrated in ethanol, equilibrated in xylene, and embedded in paraffin according to standard histological techniques. During paraffin embedding, samples were carefully aligned so that the villi were perpendicular to the cutting plane, ensuring consistent sectioning across all samples. Sections of approximately 5 μm were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before examination under optical microscopy. ImageJ 1.8.0 software was used to conduct morphometric measurements.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD and were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, SPSS ver. 27.0) to determine significant differences between treatments. The significance of differences (p < 0.05) was determined by Duncan’s test.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Dietary FHWC on the Growth Performance of M. salmoides

As shown in Table 2 and Tables S6–S9, on both day 30 and day 45, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet exhibited significantly higher SGR and WGR compared to the control group (p < 0.05). In contrast, M. salmoides fed the CHW diet showed no significant change in SGR and WGR relative to the control on day 30 and day 45 (p > 0.05). Significant differences were detected in SGR and WGR between FCHW and CHW treatments on both day 30 and day 45 (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed in FCR among the control group, the FCHW group, and the CHW group at either time point (p > 0.05). On day 30, the CHW group exhibited a significantly higher HI value than the control (p < 0.05); however, no significant differences were observed among any of the treatments by day 45 (p > 0.05). On both day 30 and day 45, significant differences over time exist in SGR, WGR, and HI within groups (p < 0.05), but not for FCR and WGR in CHW (Tables S1 and S22). No mortality was observed in any treatment group throughout the experimental period.

Table 2.

Effects of FHWC on the growth performance of M. salmoides.

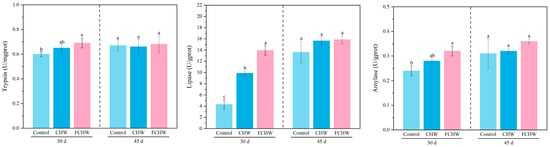

3.2. Effects of Dietary FHWC on Intestinal Digestive Function of M. salmoides

As shown in Figure 1 and Tables S10–S12, compared to the control group, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet exhibited significantly higher intestinal activities of trypsin, amylase, and lipase on day 30 (p < 0.05). M. salmoides fed the CHW diet showed a significantly higher intestinal lipase activity compared to the control (p < 0.05), but no significant differences were observed for trypsin or amylase activities (p > 0.05). Compared to the CHW group, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet had higher trypsin, amylase, and lipase activities. However, only the increase in lipase activity on day 30 was statistically significant (p < 0.05). On day 45, no significant differences were found in the intestinal activities of trypsin, amylase, or lipase among the control group, the FCHW group, and the CHW group (p > 0.05). On both day 30 and day 45, significant differences over time occur only in lipase activity within each group (p < 0.05), but not for trypsin or amylase activities (Tables S2 and S22).

Figure 1.

Effect of dietary FHWC on intestinal digestive enzyme activities in M. salmoides. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks). Within each sampling day, values sharing different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05), while those with identical letters show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

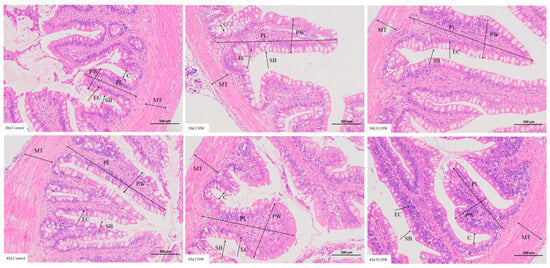

As shown in Figure 2, Table 3 and Tables S13–S15, on day 30, significant differences were observed among the control, FCHW, and CHW groups for intestinal villus height and muscularis thickness in M. salmoides (p < 0.05). The order was: FCHW group > control group > CHW group. Compared to the control group, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet exhibited a significantly greater intestinal villus width (p < 0.05). In contrast, M. salmoides fed the CHW diet showed no significant change in villus width compared to the control (p > 0.05). On day 45, M. salmoides in FCHW and CHW groups showed significantly higher intestinal villus height, villus width, and muscularis thickness compared to the control group (p < 0.05). M. salmoides in the FCHW group had significantly greater villus height than those in the CHW group (p < 0.05). However, no significant differences were found between the FCHW and CHW groups for villus width or muscularis thickness (p > 0.05). Villus height and muscularis thickness show significant increases from 30 to 45 days within each group (p < 0.05), while villus width shows no significant change except in the CHW group (Tables S3 and S22).

Figure 2.

Effects of FHWC on the intestinal microstructure of M. salmoides. MT represents muscularis thickness, PL represents villus height, PW represents villus width, C represents crypt depth, SB represents striated border, and EC represents simple columnar epithelium. The scale bar is located in the lower right corner.

Table 3.

Effects of FHWC on the intestinal morphology of M. salmoides.

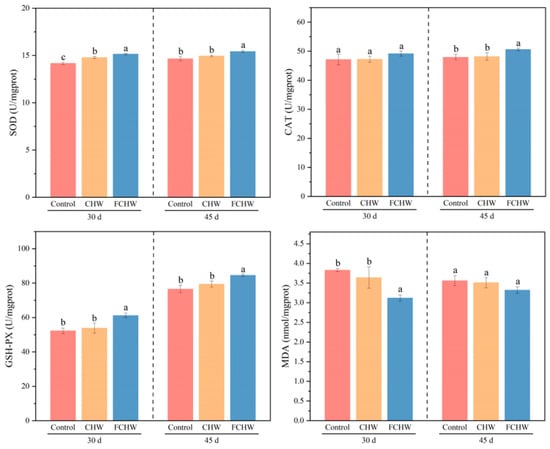

3.3. Effects of Dietary FHWC on Hepatic Antioxidative Capacity of M. salmoides

As shown in Figure 3 and Tables S16–S19, on day 30, hepatic SOD and GSH-Px activities were significantly elevated in M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet compared to the control group (p < 0.05), and CAT activity changed insignificantly (p > 0.05). SOD activity in the CHW group showed a significant increase (p < 0.05), while CAT and GSH-Px activities exhibited no significant differences relative to the control (p > 0.05). Compared to the control group, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet displayed a significant reduction in hepatic MDA levels (p < 0.05), while M. salmoides fed the CHW diet showed a non-significant decrease (p > 0.05). On day 45, SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px activities in the FCHW group were significantly higher than those in the control group (p < 0.05), but no significant differences were detected between the control and CHW groups (p > 0.05). MDA levels did not differ significantly among the control, FCHW, and CHW groups (p > 0.05). As shown in Tables S4 and S22, GSH-Px increases significantly from 30 to 45 days in all groups, while significant changes in MDA only occur in the FCHW group (p < 0.05), with no significant differences for SOD and CAT (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary FHWC on hepatic antioxidative capacity of M. salmoides. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks). Within each sampling day, values sharing different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05), while those with identical letters show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

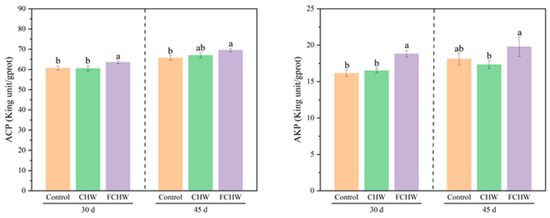

3.4. Effects of Dietary FHWC on Hepatic Non-Specific Immunity of M. salmoides

As shown in Figure 4 and Tables S20 and S21, on day 30, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet demonstrated significantly higher hepatic ACP and AKP activities compared to the control (p < 0.05), while M. salmoides fed the CHW diet showed non-significant changes in either ACP or AKP activities relative to the control (p > 0.05). On day 45, M. salmoides fed the FCHW diet exhibited a significant increase in ACP activity (p < 0.05), while AKP activity remained unchanged compared to the control (p > 0.05). No significant differences were detected in either ACP or AKP activities between the control and CHW groups (p > 0.05). As shown in Tables S5 and S22, ACP increases significantly from 30 to 45 days in all groups (p < 0.05), while AKP shows no significant change in any group (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of dietary FHWC on hepatic non-specific immunity of M. salmoides. Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 tanks). Within each sampling day, values sharing different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05), while those with identical letters show no significant difference (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

A. membranaceus, one of the most well-known Chinese herbs, possesses a complex chemical profile, with over 100 bioactive compounds having been isolated and identified from its roots [17]. In aquaculture, dietary supplementation with A. membranaceus root or root extract has demonstrated significant growth-promoting effects across multiple fish species, including Oreochromis niloticus [18], common carp (Cyprinus carpio) [19], bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus) [20], Jian Carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian) [21], angasianodon hypophthalmus [22]. Beyond its roots, Chen et al. [23] found that A. membranaceus by-products could also enhance growth performance in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). In aquaculture, Rheum and Bupleurum are more frequently used in combination with other Chinese herbs rather than alone, typically utilizing their roots or root extracts [24,25,26,27]; however, their leaves and stems have seen little practical application.

In this study, the leaves and stems of A. membranaceus, R. tanguticum, and B. chinense were crushed and mixed at a mass ratio of 5:4:1 to prepare CHW. Dietary supplementation with CHW showed no significant improvement in the growth of M. salmoides (p > 0.05). This may be attributed to the generally lower concentrations of nutrients and bioactive compounds in the stems and leaves compared to the roots, along with potentially reduced bioavailability. In contrast, fermentation of CHW with B. subtilis to produce FCHW significantly enhanced the growth of M. salmoides compared to both the control and CHW groups (p < 0.05). We hypothesize that fermentation may have enhanced the nutritional and functional profiles of CHW, possibly improving its digestibility and subsequent metabolic utilization in fish [28], thereby contributing to the observed growth promotion.

Digestive enzyme activity serves as a crucial indicator for assessing the digestive capacity of aquatic organisms [29]. In this study, dietary FCHW significantly enhanced intestinal digestive enzyme activities in M. salmoides on day 30. This effect could be partly attributed to bioactive constituents in FCHW—namely, polysaccharides, which may modulate secretory functions in the digestive system [30]. Moreover, B. subtilis introduced in the fermentation process might generate extracellular enzymes, including proteases, amylases, and lipases [31], which could supplement the host’s endogenous digestive enzymes and facilitate nutrient breakdown [32].

Intestinal morphology plays a pivotal role in fish growth, nutrient utilization, and immune regulation [33]. Dietary composition is a critical determinant of intestinal histomorphology, with structural adaptations—particularly in villus height, width, and muscularis thickness—occurring in response to nutritional shifts [33]. Dietary FCHW diet significantly increased intestinal villus height, villus width, and muscularis thickness of M. salmoides. These structural improvements were possibly resulting from an improved intestinal microenvironment and promoted epithelial cell proliferation [34].

Fermentation has been extensively employed to enhance the antioxidant capacity of CHMs. Higher antioxidant capacity of fermented CHMs was evidenced by elevated free radical and reactive oxygen species scavenging capacity, increased expression of antioxidant enzymes [28]. Antioxidant enzymes serve as crucial indicators for aquatic animals in combating oxidative stress. Among them, SOD, CAT, and GSH-PX constitute the primary antioxidant defense system. SOD and CAT primarily function in scavenging superoxide anion radicals and decomposing hydrogen peroxide generated during antioxidative processes, thereby mitigating oxidative damage [35]. GSH-PX plays a pivotal role in eliminating organic hydroperoxides and hydrogen peroxide by catalyzing their reduction using glutathione as an electron donor, effectively preventing lipid peroxidation chain reactions [36]. The present study demonstrated that dietary FCHW significantly enhanced hepatic antioxidant enzyme activities, including SOD, CAT, and GSH-PX, in M. salmoides while simultaneously reducing MDA levels to the lowest values. These findings align with a previous study reporting that dietary probiotic-fermented CHM could effectively improve the antioxidant capacity in the liver of juvenile M. salmoides [37]. The elevated antioxidant enzyme activities and reduced lipid peroxidation suggest that FCHW may help mitigate oxidative stress, potentially through free radical scavenging by bioactive compounds formed or released during fermentation.

AKP and ACP are key hydrolytic enzymes in fish immune defense systems and serve as important metabolic regulators. They primarily catalyze the hydrolysis of phosphate esters to release inorganic phosphate, thereby promoting ATP production during immune responses. Consequently, phosphatase activity in aquatic animals functions as a biomarker for assessing immune status [38,39]. In this study, dietary FCHW significantly enhanced hepatic AKP and ACP activities compared to the control, whereas CHW did not. The fermentation process substantially increased the content of total polysaccharides in CHW. We hypothesize that the fermentation-induced increase in total polysaccharides and the concomitant presence of B. subtilis in FCHW are potential contributors to this observed upregulation.

5. Conclusions

Dietary supplementation of FCHW could enhance growth performance, antioxidant capacity, digestive function, and non-specific immunity in M. salmoides. In contrast, unfermented CHW supplementation demonstrated minimal effects. Fermentation with the probiotic B. subtilis enabled efficient valorization of CHW, transforming low-value CHW into a promising functional aquafeed additive. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms behind FCHW’s growth-promoting effects and to compare its efficacy with commercial immunostimulants or established probiotics, which is a critical step toward facilitating its commercial application.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fishes10120629/s1, Table S1. Comparison of growth indicators among groups at different time points. Table S2. Comparison of intestinal digestive enzyme activities among groups at different time points. Table S3. Comparison of intestinal morphology among groups at different time points. Table S4. Comparison of hepatic antioxidative capacity among groups at different time points. Table S5. Comparison of hepatic non-specific immunity among groups at different time points. Table S6. SGR ANOVA results. Table S7. WGR ANOVA results. Table S8. FCR ANOVA results. Table S9. HI ANOVA results. Table S10. Trypsin ANOVA results. Table S11. Lipase ANOVA results. Table S12. Amylase ANOVA results. Table S13. Villus height ANOVA results. Table S14. Villus width ANOVA results. Table S15. Muscularis thickness ANOVA results. Table S16. SOD ANOVA results. Table S17. CAT ANOVA results. Table S18. GSH-PX ANOVA results. Table S19. MDA ANOVA results. Table S20. ACP ANOVA results. Table S21 AKP ANOVA results. Table S22. Result of paired samples t test.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.B.; methodology, X.Z. (Xiaolei Zhang); formal analysis, X.Z. (Xiaolei Zhang), W.D. and X.Z. (Xinye Zhao); investigation, X.Z. (Xiaolei Zhang); writing—original draft preparation, X.Z. (Xinye Zhao); writing—review and editing, W.D.; supervision, X.B.; project administration, X.Z. (Xiaolei Zhang) and Z.S.; funding acquisition, X.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Gansu Science and Technology Planning Project (24CXNP005, 24CXNP011) and the Tianjin Science and Technology Planning Project (24ZYCGSN00140).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Tianjin Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval Code: BM2018; Approval Date: 2 June 2024).

Data Availability Statement

The data used to generate the results in this manuscript can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FCHW | Fermented Chinese herbal waste compound |

| CHW | Chinese herbal waste |

References

- Pu, H.; Li, X.; Du, Q.; Cui, H.; Xu, Y. Research progress in the application of Chinese herbal medicines in aquaculture: A Review. Engineering 2017, 3, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Jia, S.; Zhi-Nan, Y.; Shuang, L.; Yue-Hong, L.I. Research progress of Chinese herbal medicine in aquaculture. Feed Res. 2023, 46, 133–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.; Bose, S.; Wang, J.-H.; Yadav, M.K.; Mahajan, G.B.; Kim, H. Fermentation, a feasible strategy for enhancing bioactivity of herbal medicines. Food Res. Int. 2016, 81, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Fan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. The Application of fermentation technology in traditional Chinese medicine: A review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2020, 48, 899–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Yang, R.; Ma, F.; Jiang, W.; Han, C. Recycling utilization of Chinese medicine herbal residues resources: Systematic evaluation on industrializable treatment modes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 32153–32167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, Z.-X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Hu, Y.; Gao, J. Treatment and bioresources utilization of traditional Chinese medicinal herb residues: Recent technological advances and industrial prospect. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Lutz-Carrillo, D.J.; Quan, Y.; Liang, S. Taxonomic status and genetic diversity of cultured largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides in China. Aquaculture 2008, 278, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Ramos, F. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Current knowledge and alternatives to tackle the problem. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.L.; Bi, X.D.; Wang, X.Y.; Dai, W. Study on optimization of aerobic fermentation conditions for stems and leaves of compound Chinese herbs. Feed Res. 2024, 23, 119–124. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.S.; Li, J.L.; Wu, T.T. Effects of exogenous enzyme and citric acid on activities of endogenous digestive enzyme of tilapia(Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus). J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2005, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shen, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Xue, Y. Effects of chronic exposure of 2,4-dichlorophenol on the antioxidant system in liver of freshwater fish Carassius auratus. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenzado, C.; Hidalgo, M.C.; García-Gallego, M.; Morales, A.E.; Furné, M.; Domezain, A.; Domezain, J.; Sanz, A. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation in sturgeon Acipenser naccarii and trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. A comparative study. Aquaculture 2006, 254, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; Volume 105, pp. 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru, M.I.; Dogru, A.K.; Gul, M.; Esrefoglu, M.; Yurekli, M.; Erdogan, S.; Ates, B. The effect of adrenomedullin on rats exposed to lead. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2008, 28, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhao, L.; Pan, Y.; Kang, Y.; Liu, Z. Chinese herbal medicines mixture improved antioxidant enzymes, immunity and disease resistance to infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus infection in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquac. Int. 2024, 32, 3217–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, L.; Gao, C.; Chen, W.; Vong, C.T.; Yao, P.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Tang, X.; Wang, S.; et al. Astragali Radix (Huangqi): A promising edible immunomodulatory herbal medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 258, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elabd, H.; Wang, H.-P.; Shaheen, A.; Matter, A. Astragalus membranaceus nanoparticles markedly improve immune and anti-oxidative responses; and protection against Aeromonas veronii in Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 97, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.-T.; Zhao, S.-Z.; Wang, K.-L.; Fan, M.-X.; Han, Y.-Q.; Wang, H.-L. Effects of dietary Astragalus Membranaceus supplementation on growth performance, and intestinal morphology, microbiota and metabolism in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 100955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, H.; Wang, H.-P.; Shaheen, A.; Yao, H.; Abbass, A. Astragalus membranaceus (AM) enhances growth performance and antioxidant stress profiles in bluegill sunfish (Lepomis macrochirus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 42, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, G.; Wu, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, H. The extract of Astragalus membranaceus inhibits lipid oxidation in fish feed and enhances growth performance and antioxidant capacity in Jian carp (Cyprinus carpio var. Jian). Fishes 2023, 8, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Latif, H.M.R.; Ahmed, H.A.; Shukry, M.; Chaklader, M.R.; Saleh, R.M.; Khallaf, M.A. Astragalus membranaceus Extract (AME) enhances growth, digestive enzymes, antioxidant capacity, and immunity of Pangasianodon hypophthalmus juveniles. Fishes 2022, 7, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xu, J.; Huang, J.; Li, H.; Yu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, T.; Pu, J.; Luo, L.; et al. Effects of Astragalus membranaceus by-product on pellet quality, mold growth and resistance of Crucian carp (Carassius auratus) against Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 43, 102820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, I.P.; Lee, P.-T.; Nan, F.-H. Rheum officinale extract promotes the innate immunity of orange-spotted grouper (Epinephelus coioides) and exerts strong bactericidal activity against six aquatic pathogens. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 102, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.F.; Zhu, B.; Wang, Y.; Lu, C.; Wang, G.X. In vivo evaluation of anthelmintic potential of medicinal plant extracts against Dactylogyrus intermedius (Monogenea) in goldfish (Carassius auratus). Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Sun, W.; Yin, S.; Long, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y. Improvement effects and mechanism of compound Chinese herbal medicine on fatty liver in largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides. Aquaculture 2025, 598, 742075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.T.; Ding, Z.L.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, W.Q.; Xia, R.X.; Yang, S.; Fei, H. Combination of herbal extracts regulates growth performance, liver and intestinal morphology, antioxidant capacity, and intestinal microbiota in Acrossocheilus fasciatus. Aquaculture 2025, 594, 741428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, J.; Ling, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Application of fermented Chinese herbal medicines in food and medicine field: From an antioxidant perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 148, 104410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, F.J.; Díaz, M.; Alarcón, F.J.; Sarasquete, M.C. Characterization of digestive enzyme activity during larval development of gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 1996, 15, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, Y. The effect of fermented Chinese herbal medicine extracts on the growth performance and intestinal digestive enzyme activity of Ictalurus punctatus. Feed China 2010, 15, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schallmey, M.; Singh, A.; Ward, O.P. Developments in the use of Bacillus species for industrial production. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, M.A.O.; Koshio, S. Application of fermentation strategy in aquafeed for sustainable aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Li, X.M.; Shu, H.; Zhang, H.F.; Shi, H.R. The effects of two kinds of microecologics on body composition, intestinal digestive enzyme and histological structure of hybrid grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀×E. lanceolatus ♂). Feed Ind. 2018, 39, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhong, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lv, Z.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y. Effects of dietary andrographolide levels on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, intestinal immune function and microbioma of rice field eel (Monopterus Albus). Animals 2020, 10, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandalios, J.G. Oxidative stress: Molecular perception and transduction of signals triggering antioxidant gene defenses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2005, 38, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavas, L.; Tarhan, L. Glutathione redox system, GSH-Px activity and lipid peroxidation (LPO) levels in tadpoles of R.r.ridibunda and B.viridis. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2003, 21, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Wu, Q.; Bao, S.; Jiang, L.; Liu, B. Effects of dietary fermented Chinese herbal medicines on growth performance, digestive enzyme activity, liver antioxidant capacity, and intestinal inflammatory gene expression of juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 25, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wei, L.; Zhai, H.; Ren, T.; Han, Y. An evaluation on betaine and trimethylammonium hydrochloride in the diet of Carassius auratus: Growth, immunity, and fat metabolism gene expression. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 19, 100627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ayiku, S.; Liu, H.; Tan, B.; Dong, X.; Chi, S.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, W. Effects of dietary ESTAQUA® yeast culture supplementation on growth, immunity, intestinal microbiota and disease-resistance against Vibrio harveyi in hybrid grouper (♀Epinephelus fuscoguttatus×♂E. lanceolatus). Aquac. Rep. 2022, 22, 100922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).