Silencing of the Superaquaporin LvAQP11 Disrupts Salinity Tolerance, Molting Cycle, and Myofibril Organization in Litopenaeus vannamei

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

2.2. Evaluation of RNAi Efficiency for LvAQP11

2.3. Impact of LvAQP11 Knockdown on Salinity Adaptation

2.4. Effects of LvAQP11 Knockdown on the Molting Cycle

2.5. Growth Performance Under Long-Term Silencing of LvAQP11

2.6. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.7. Transcriptome Sequencing and Functional Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

2.8. qPCR Analysis of Target Genes

3. Results

3.1. Effect of LvAQP11 Knockdown on Shrimp Salinity Adaptation

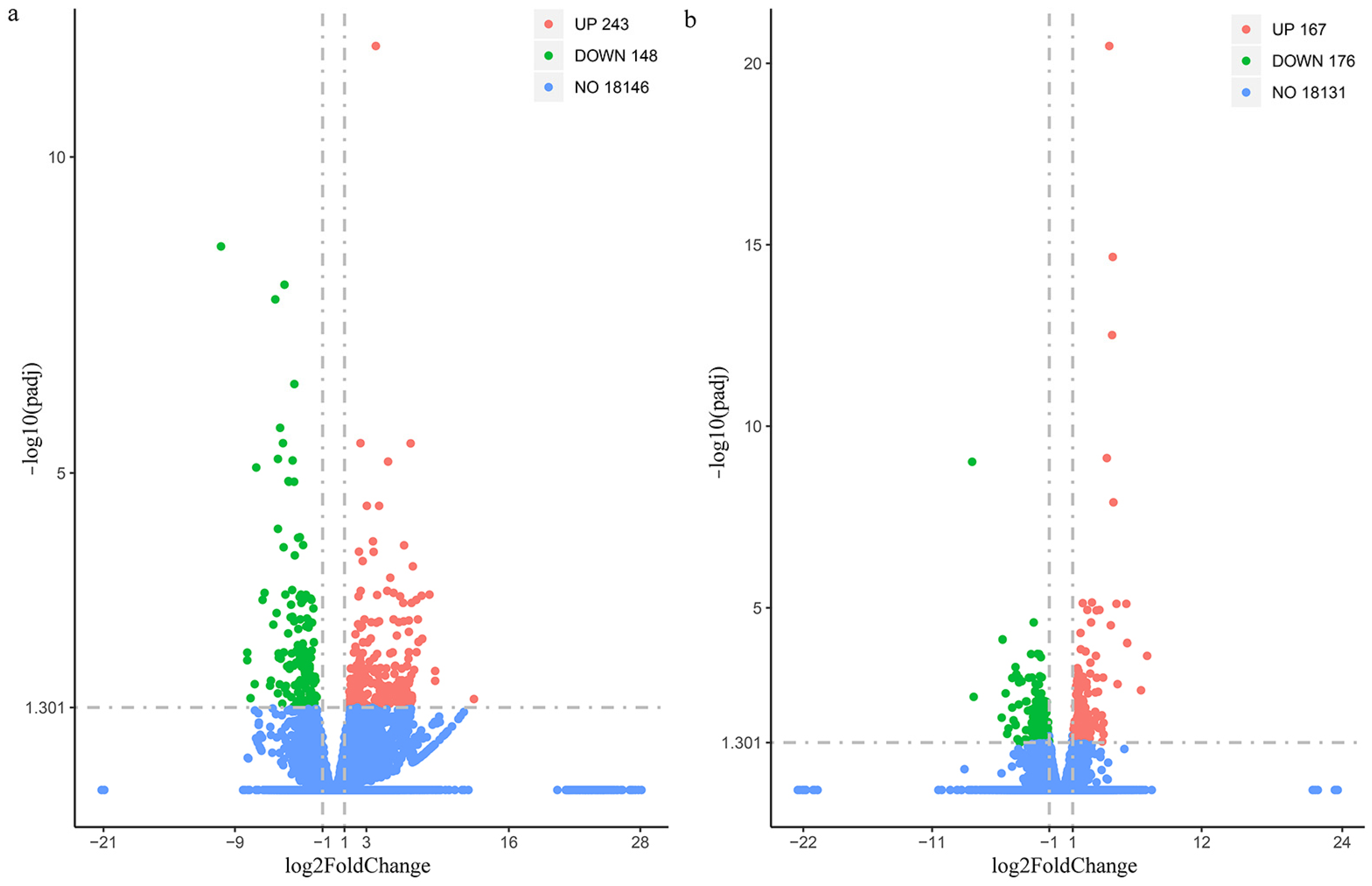

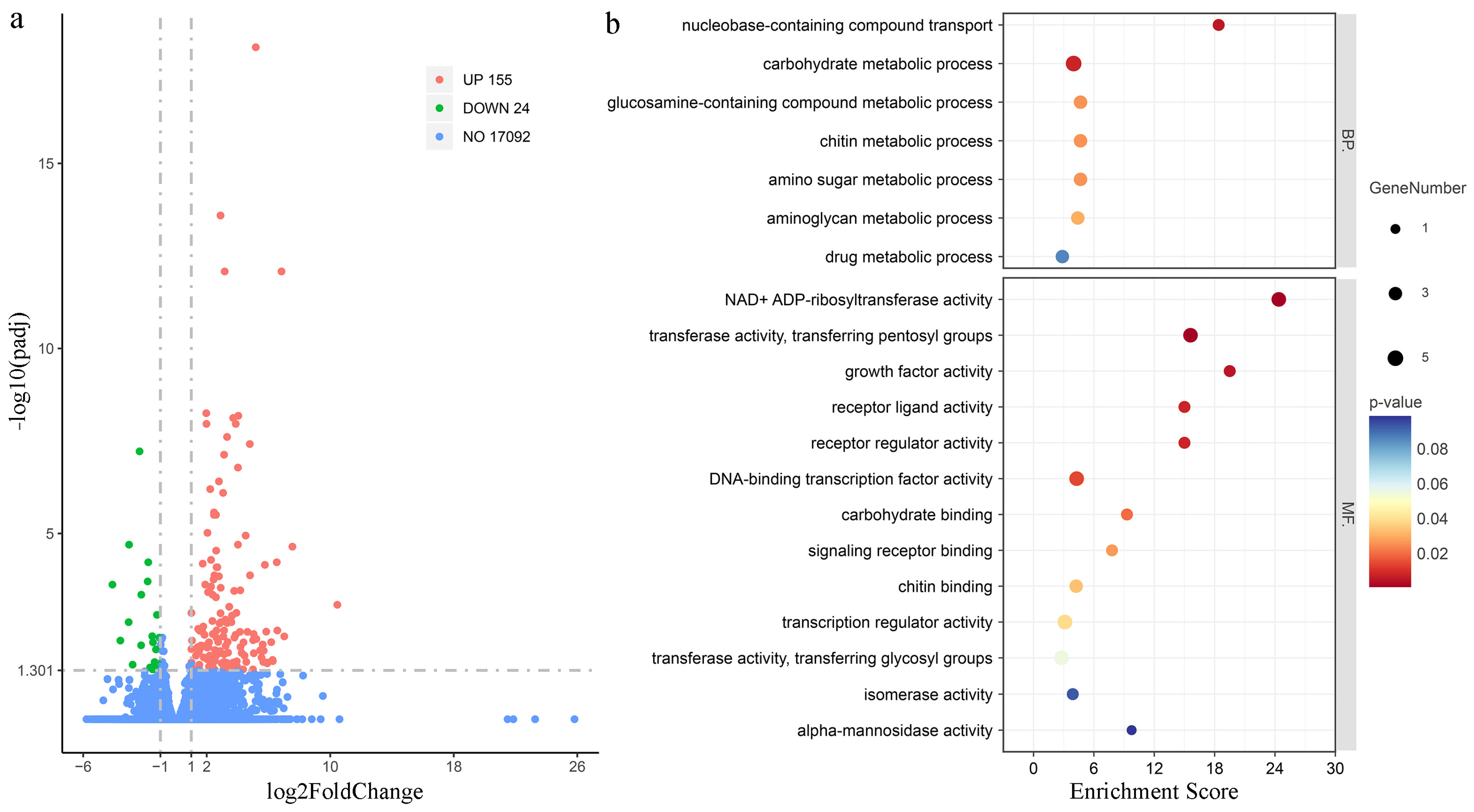

3.2. RNA-Seq of Muscle Tissues During High-Salinity Stress Post-LvAQP11 Silencing

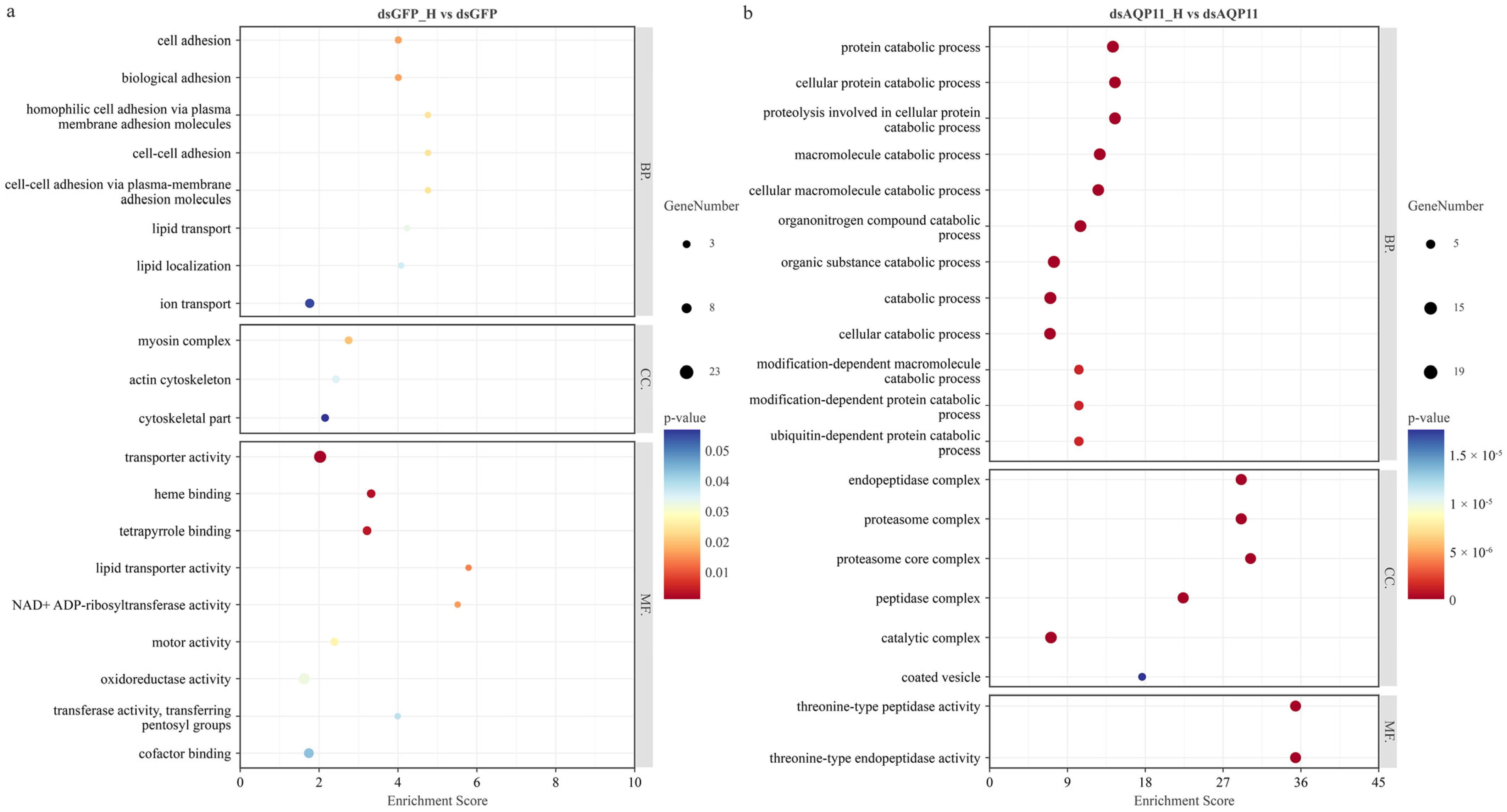

3.3. GO Enrichment Analysis of DEGs Under High-Salinity Stress

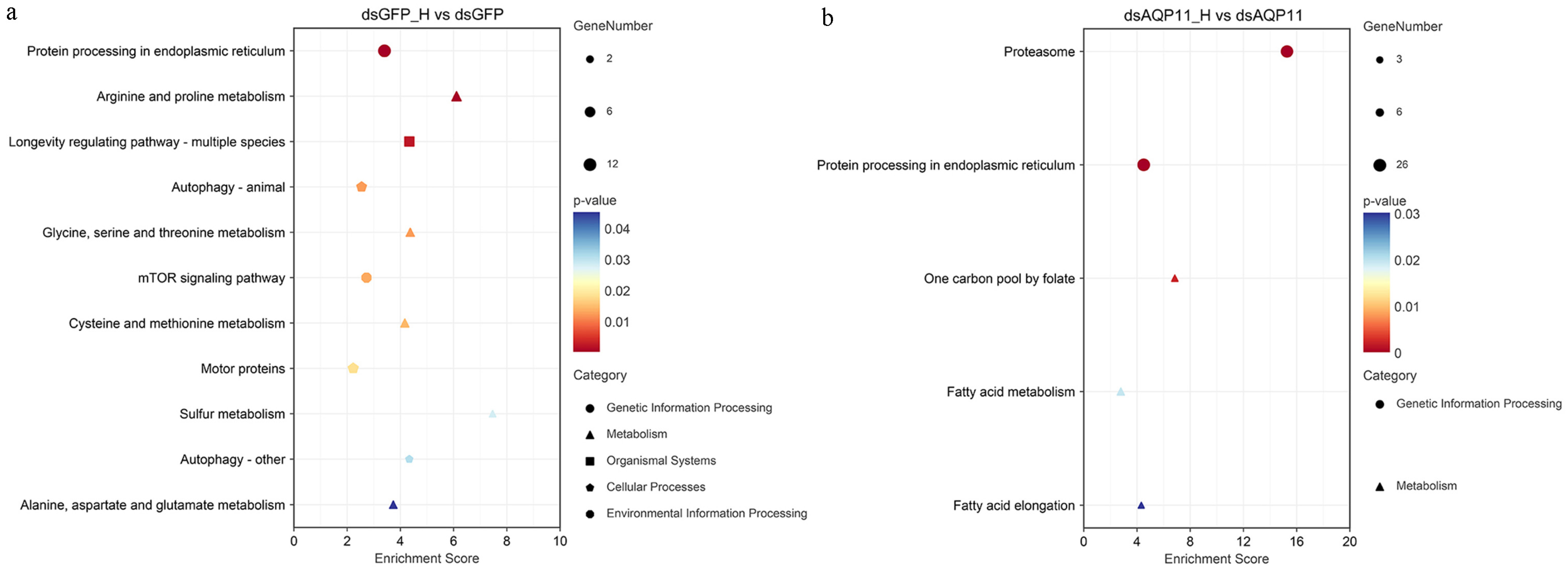

3.4. KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs Under High-Salinity Stress

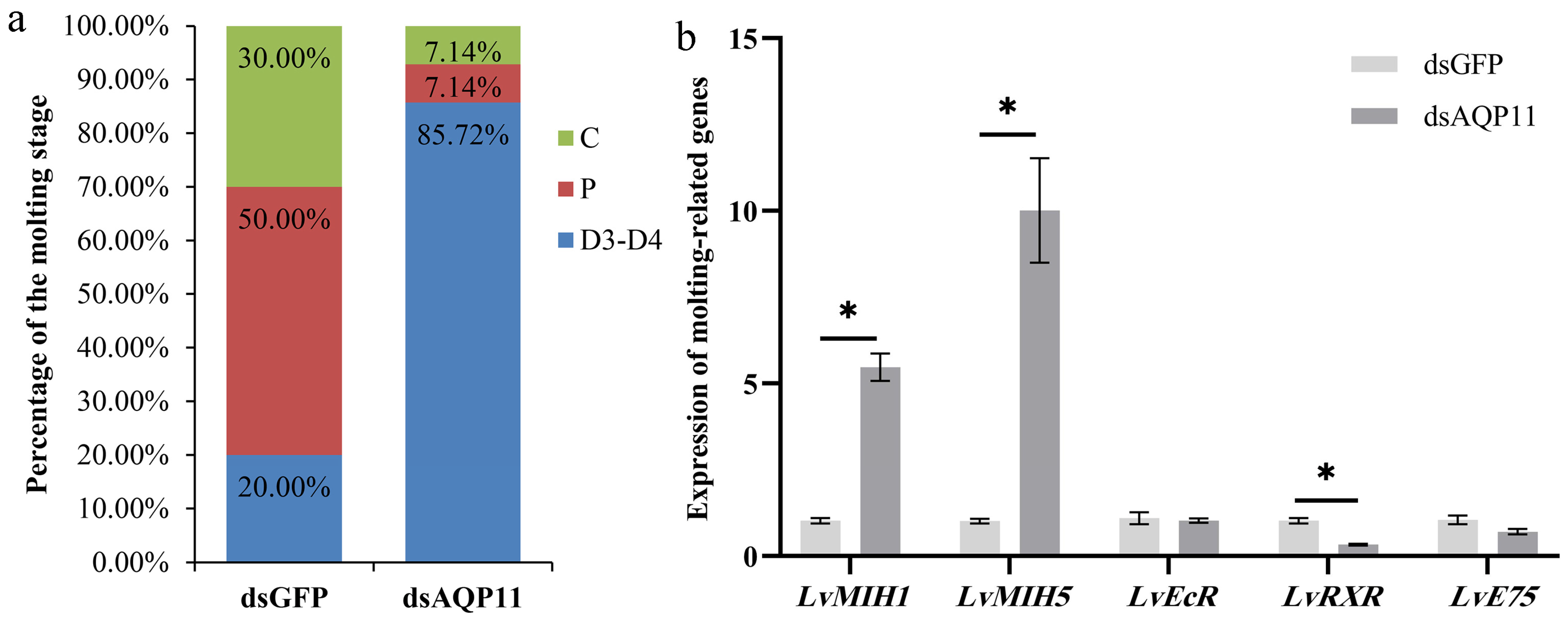

3.5. Effect of LvAQP11 Knockdown on Molting Cycle

3.6. Effect of Long-Term Silencing of LvAQP11 on the Growth of Shrimp

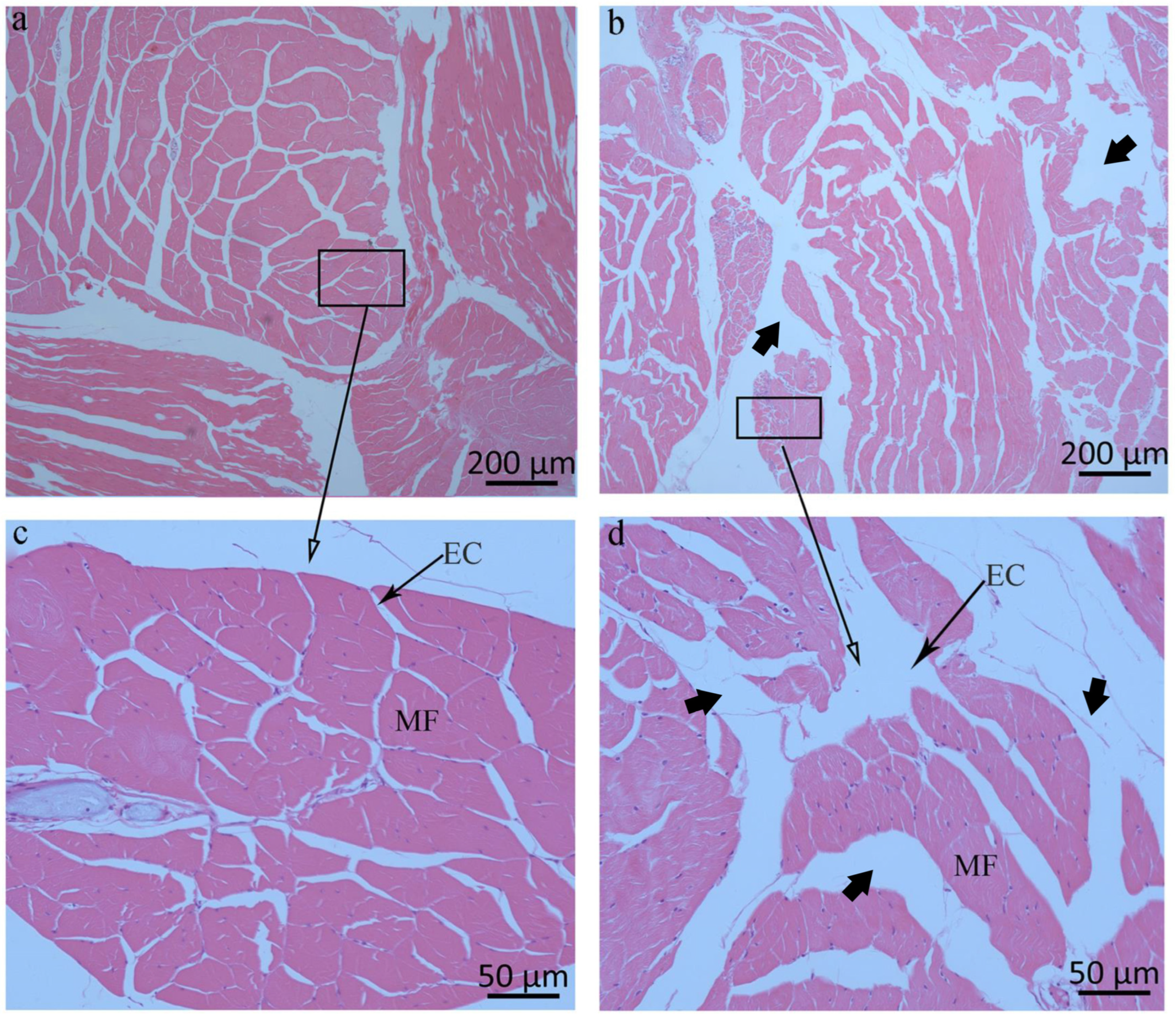

3.7. RNA-Seq Analysis of Muscle Tissue After Long-Term Silencing of LvAQP11

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of LvAQP11 in the Adaptation to High-Salinity Stress

4.2. The Role of LvAQP11 in the Regulation of Molting

4.3. The Role of LvAQP11 in the Regulation of Muscle Growth

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBW | initial body weight |

| FBW | final body weight |

| WGR | weight gain rate |

| SGR | specific growth rate |

| MWC | muscle water content |

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Li, N.; Dong, T.; Fu, Q.; Cui, Y.; Li, Y. Analysis of differential gene expression in Litopenaeus vannamei under high salinity stress. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, R.; Muralidhar, M.; Balasubramanian, C.P.; Rajesh, R.; Sukumaran, S.; Kumararaja, P.; Dayal, J.S.; Avunje, S.; Nagavel, A.; Vijayan, K.K. Osmo-ionic regulation in whiteleg shrimp, Penaeus vannamei, exposed to climate change-induced low salinities. Aquac. Res. 2021, 52, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, M.d.L.; Moshtaghi, A.; Mather, P.B.; Hurwood, D.A. Osmoregulation in decapod crustaceans: Physiological and genomic perspectives. Hydrobiologia 2018, 825, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, C.; Duan, H.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Convergent evolution of the osmoregulation system in decapod shrimps. Mar. Biotechnol. 2017, 19, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghi, A.; Rahi, M.d.L.; Nguyen, V.T.; Mather, P.B.; Hurwood, D.A. A transcriptomic scan for potential candidate genes involved in osmoregulation in an obligate freshwater Palaemonid prawn (Macrobrachium Australiense). PeerJ 2016, 4, e2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ren, C.; Jiang, X.; Cheng, C.; Ruan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Chen, T.; Hu, C. Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei): Molecular cloning, transcriptional response to acidity stress, and physiological roles in pH Hhomeostasis. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0212887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dai, X. Characterization and functional analysis of Litopenaeus vannamei Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter 1 under nitrite stress. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2024, 298, 111749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Pan, L. Cloning and expression analysis of two carbonic anhydrase genes in white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei, induced by pH and salinity Stresses. Aquaculture 2015, 448, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Q. Effect of salinity on the biosynthesis of amines in Litopenaeus vannamei and the expression of gill related ion transporter genes. J. Ocean Univ. China 2014, 13, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtaghi, A.; Rahi, M.d.L.; Mather, P.B.; Hurwood, D.A. An investigation of gene expression patterns that contribute to osmoregulation in Macrobrachium australiense: Assessment of adaptive responses to different osmotic niches. Gene Rep. 2018, 13, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agre, P.; King, L.S.; Yasui, M.; Guggino, W.B.; Ottersen, O.P.; Fujiyoshi, Y.; Engel, A.; Nielsen, S. Aquaporin water channels--from atomic structure to clinical medicine. J. Physiol. 2002, 542, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.N.; Cerdà, J. Evolution and functional diversity of aquaporins. Biol. Bull. 2015, 229, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.S.; Maurer, L.; Bratcher, M.; Pitula, J.S.; Ogburn, M.B. Cloning of aquaporin-1 of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus: Its expression during the larval development in hyposalinity. Aquat. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foguesatto, K.; Bastos, C.L.Q.; Boyle, R.T.; Nery, L.E.M.; Souza, M.M. Participation of Na+/K+-ATPase and aquaporins in the uptake of water during moult processes in the shrimp Palaemon argentinus (Nobili, 1901). J. Comp. Physiol. B 2019, 189, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Hao, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Song, G.; Cui, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, R.; et al. RNAi-mediated knockdown of the aquaporin 4 gene impairs salinity tolerance and delays the molting process in Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Aquac. Rep. 2024, 35, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, Y. Aquaporins in Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei): Molecular characterization, expression patterns, and transcriptome analysis in response to salinity stress. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 817868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Morishita, Y.; Tanaka-Mochizuki, Y. Role of Mammalian Aquaporin inside the Cell: An Update. In Peroxiporins; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, F.; Liang, L.; Wang, S.; Liew, H.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhan, F.; Liang, L.; Wang, S.; Liew, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis and Expression Pattern Profiling of the Aquaporin Family Genes in Leuciscus waleckii. Fishes 2023, 8, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Zhao, X.; Liang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the Aquaporin Gene Family Reveals the Role in the Salinity Adaptability in Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Genes Genom. 2022, 44, 1457–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Z.; Zhao, R.; Sun, J.; Hao, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; et al. How Do Gene Expression Patterns Change in Response to Osmotic Stresses in Kuruma Shrimp (Marsupenaeus Japonicus)? J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, Z. Cloning and Characterization of Aquaporins 11 and Its Expression Analysis under Molt Cycle in Eriocheir Sinensis. Int. J. Aquac. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K. Aquaporin Subfamily with Unusual NPA Boxes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1758, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Morishita, Y. The Role of Mammalian Superaquaporins inside the Cell: An Update. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Shi, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Effect of Ice Water Pretreatment on the Quality of Pacific White Shrimps (Litopenaeus Vannamei). Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 7, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Lv, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Penaeid Shrimp Genome Provides Insights into Benthic Adaptation and Frequent Molting. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, J.; Sun, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Whole Transcriptome Analysis Provides Insights into Molecular Mechanisms for Molting in Litopenaeus Vannamei. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G.M.; Antonescu, C.M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. StringTie Enables Improved Reconstruction of a Transcriptome from RNA-Seq Reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertea, M.; Kim, D.; Pertea, G.M.; Leek, J.T.; Salzberg, S.L. Transcript-Level Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1650–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes among Gene Clusters. Omics J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Z.; He, S.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Hou, F.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Mi, X.; Wang, P.; Liu, X. Identification of ecdysteroid signaling late-response genes from different tissues of the Pacific white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Comp. Biochem. Phys. A 2014, 172, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Chong, W.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Q.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ma, Y.; et al. Alternative Splicing-Derived Intersectin1-L and Intersectin1-S Exert Opposite Function in Glioma Progression. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Chen, L. Transcriptome sequencing revealed the genes and pathways involved in salinity stress of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Physiol. Genom. 2014, 46, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinji, J.; Okutsu, T.; Jayasankar, V.; Jasmani, S.; Wilder, M.N. Metabolism of amino acids during hyposmotic adaptation in the whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 1945–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, C.; Chen, K.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L.; Li, E. Molecular pathway and gene responses of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei to acute low salinity stress. J. Shellfish Res. 2015, 34, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; et al. Simple sequence repeats drive genome plasticity and promote adaptive evolution in Penaeid shrimp. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestetti, S.; Galli, M.; Sorrentino, I.; Pinton, P.; Rimessi, A.; Sitia, R.; Medraño-Fernandez, I. Human aquaporin-11 guarantees efficient transport of H2O2 across the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Redox Biol. 2019, 28, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atochina-Vasserman, E.N.; Biktasova, A.; Abramova, E.; Cheng, D.-S.; Polosukhin, V.V.; Tanjore, H.; Takahashi, S.; Sonoda, H.; Foye, L.; Venkov, C.; et al. Aquaporin 11 insufficiency modulates kidney susceptibility to oxidative stress. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2013, 304, F1295–F1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rützler, M.; Rojek, A.; Damgaard, M.V.; Andreasen, A.; Fenton, R.A.; Nielsen, S. Temporal Deletion of Aqp11 in mice is linked to the severity of cyst-like disease. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2017, 312, F343–F351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Cesar, J.R.; Zhao, B.; Malecha, S.; Ako, H.; Yang, J. Morphological and Biochemical Changes in the muscle of the marine shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei during the molt cycle. Aquaculture 2006, 261, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiao, C. Molt-dependent transcriptome analysis of claw muscles in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykles, D.L.; Chang, E.S. Hormonal control of the crustacean molting gland: Insights from transcriptomics and proteomics. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2020, 294, 113493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah-Zawawi, M.-R.; Afiqah-Aleng, N.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Sung, Y.Y.; Tola, S.; Fazhan, H.; Waiho, K. Recent development in ecdysone receptor of crustaceans: Current knowledge and future applications in crustacean aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1938–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Ge, H. Analysis of transcriptome difference between rapid-growing and slow-growing in Penaeus vannamei. Gene 2021, 787, 145642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, C.A.; Andrade, S.C.S.; Teixeira, A.K.; Farias, F.; Guerrelhas, A.C.; Rocha, J.L.; Freitas, P.D. Transcriptome differential expression analysis reveals the activated genes in Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp families of superior growth performance. Aquaculture 2021, 531, 735871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhong, X.; Song, W.; Yuan, J.; Sha, Z.; Li, F. Gene structure, expression and function analysis of the MyoD gene in the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Gene 2024, 921, 148523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Si, S.; Liu, C.; Yuan, J.; Li, F. RNA sequencing and LncRNA identification in muscle of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei at different growth rates. Aquaculture 2024, 582, 740534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.; Chen, L.; Zeng, C.; Chen, X.; Yu, N.; Lai, Q.; Qin, J.G. Growth, Body Composition, Respiration and ambient ammonia nitrogen tolerance of the juvenile white shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, at different salinities. Aquaculture 2007, 265, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Yang, L.; Zuo, H.; Zheng, J.; Weng, S.; He, J.; Xu, X. A chitinase from Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei involved in immune regulation. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2018, 85, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Reumont, B.M.; Undheim, E.A.B.; Jauss, R.-T.; Jenner, R.A. Venomics of remipede crustaceans reveals novel peptide diversity and illuminates the venom’s biological role. Toxins 2017, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogessie, B.; Roth, D.; Rahil, Z.; Straube, A. A novel isoform of MAP4 organises the paraxial microtubule array required for muscle cell differentiation. eLife 2015, 4, e05697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straube, A.; Merdes, A. EB3 regulates microtubule dynamics at the cell cortex and is required for myoblast elongation and fusion. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1318–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, K.K.; Eskelinen, E.-L.; Scott, C.C.; Malevanets, A.; Saftig, P.; Grinstein, S. LAMP proteins are required for fusion of lysosomes with phagosomes. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Pathak, D.; Thakur, S.; Singh, S.; Dubey, A.K.; Mallik, R. Dynein clusters into lipid microdomains on phagosomes to drive rapid transport toward lysosomes. Cell 2016, 164, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | IBW | FBW | WGR (%) | SGR (%) | MWC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsGFP_M | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.57 ± 0.08 | 60.33 ± 8.51 | 1.61 ± 0.18 | 77.06 ± 1.53 a |

| dsAQP11_M | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 1.72 ± 0.10 | 64.67 ± 10.06 | 1.57 ± 0.19 | 85.62 ± 2.42 b |

| Comparison | KEGG ID | KEGG Pathways | p-Value | Up * | Down * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dsAQP11_M vs. dsGFP_M | ko04145 | Phagosome | 0.0008 | 5 | 0 |

| ko00520 | Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | 0.0019 | 3 | 1 | |

| ko04814 | Motor proteins | 0.0028 | 4 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Song, G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, K.; Cui, Y.; Liu, F.; Wang, R.; Li, Y. Silencing of the Superaquaporin LvAQP11 Disrupts Salinity Tolerance, Molting Cycle, and Myofibril Organization in Litopenaeus vannamei. Fishes 2025, 10, 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120631

Wang Z, Song G, Zhang S, Zhang L, Wang B, Zhao K, Cui Y, Liu F, Wang R, Li Y. Silencing of the Superaquaporin LvAQP11 Disrupts Salinity Tolerance, Molting Cycle, and Myofibril Organization in Litopenaeus vannamei. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):631. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120631

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhongkai, Guanghao Song, Shikui Zhang, Long Zhang, Beibei Wang, Kunpeng Zhao, Yanting Cui, Fei Liu, Renjie Wang, and Yuquan Li. 2025. "Silencing of the Superaquaporin LvAQP11 Disrupts Salinity Tolerance, Molting Cycle, and Myofibril Organization in Litopenaeus vannamei" Fishes 10, no. 12: 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120631

APA StyleWang, Z., Song, G., Zhang, S., Zhang, L., Wang, B., Zhao, K., Cui, Y., Liu, F., Wang, R., & Li, Y. (2025). Silencing of the Superaquaporin LvAQP11 Disrupts Salinity Tolerance, Molting Cycle, and Myofibril Organization in Litopenaeus vannamei. Fishes, 10(12), 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120631