Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alterations Associated with Environmental and Host Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Sampling

2.2. Sample Processing and Analysis

2.3. Bioinformatics

3. Results

3.1. Host and Environmental Parameters

3.2. Bioinformatics

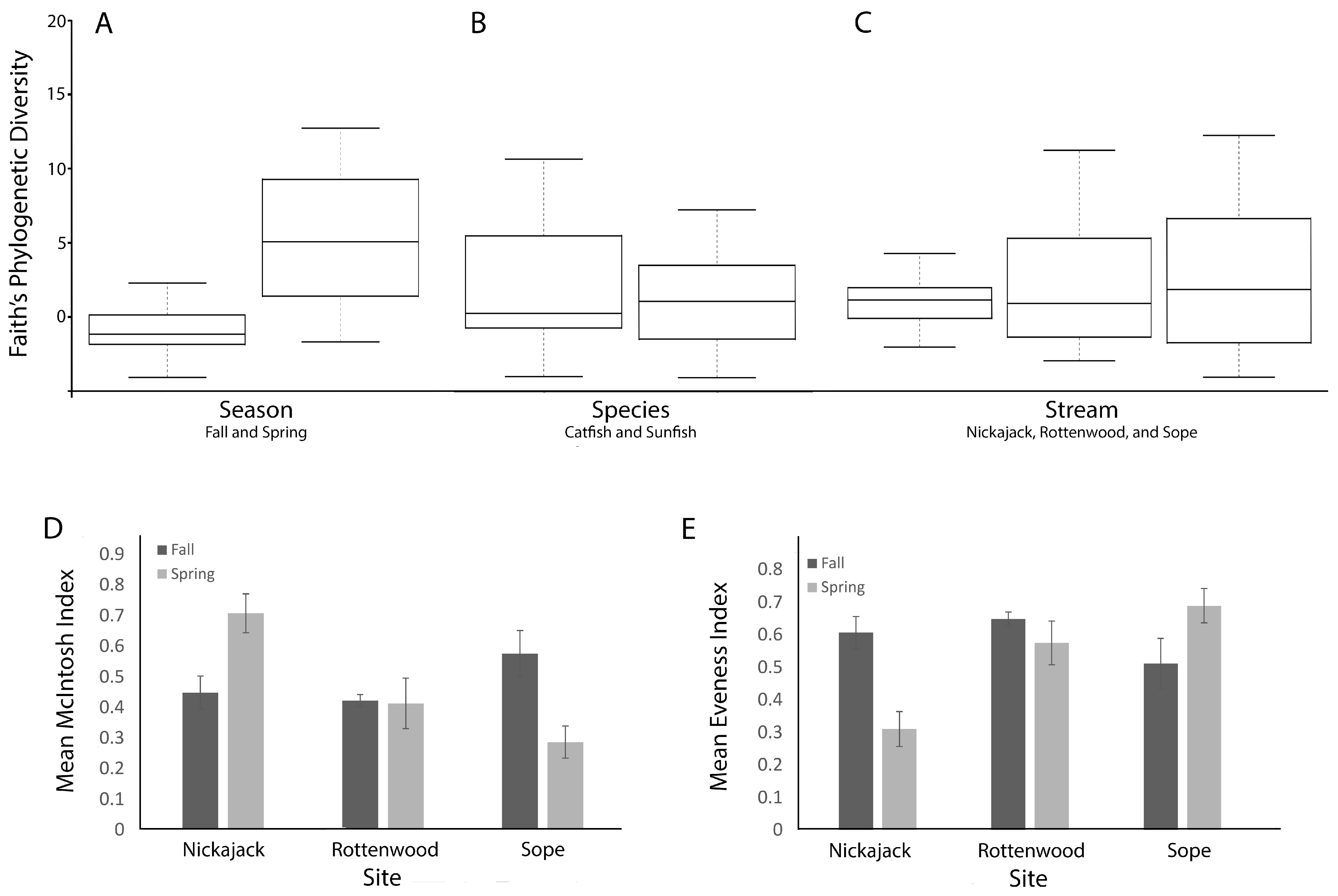

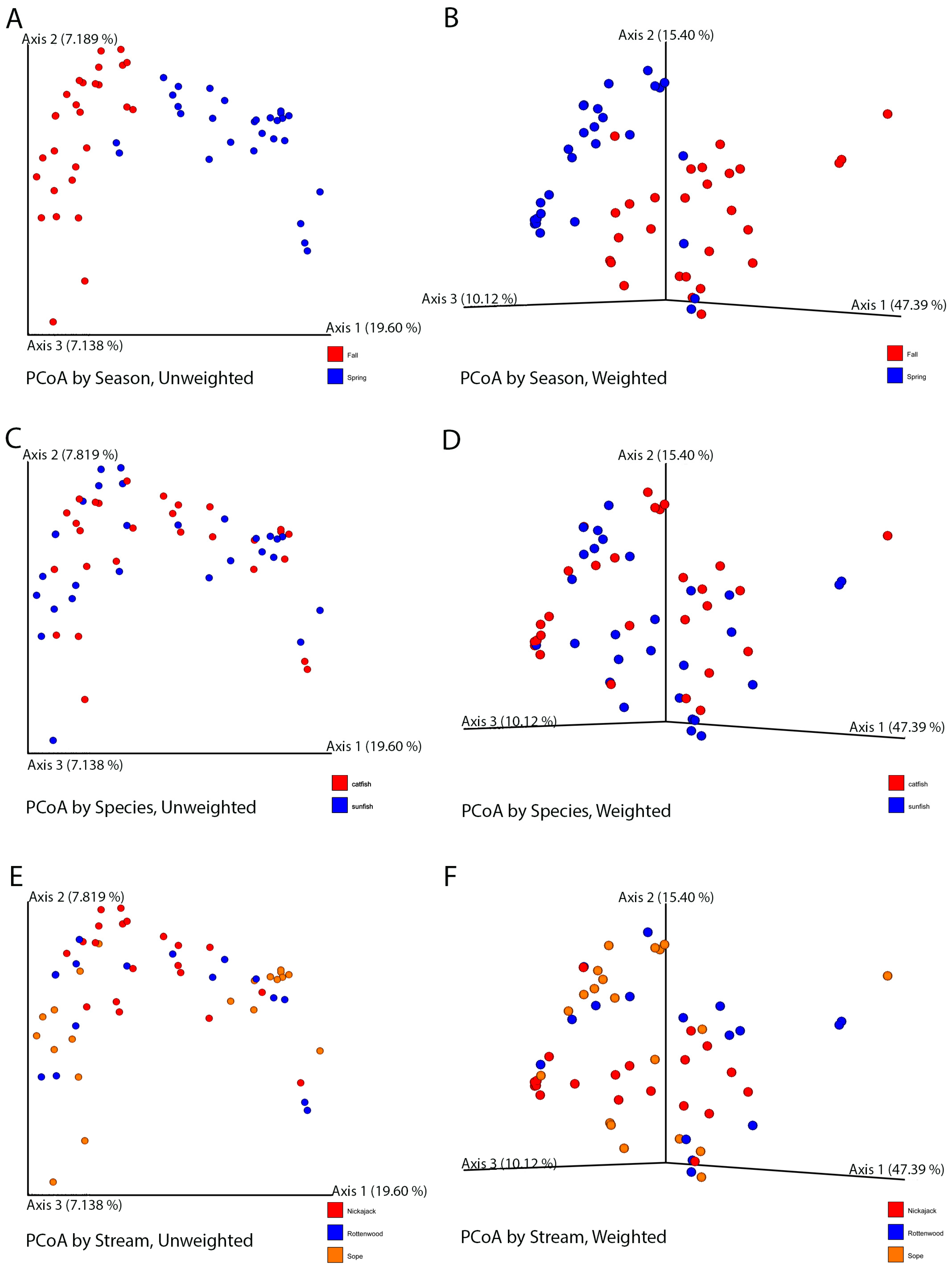

3.3. Alpha and Beta Diversity Analysis

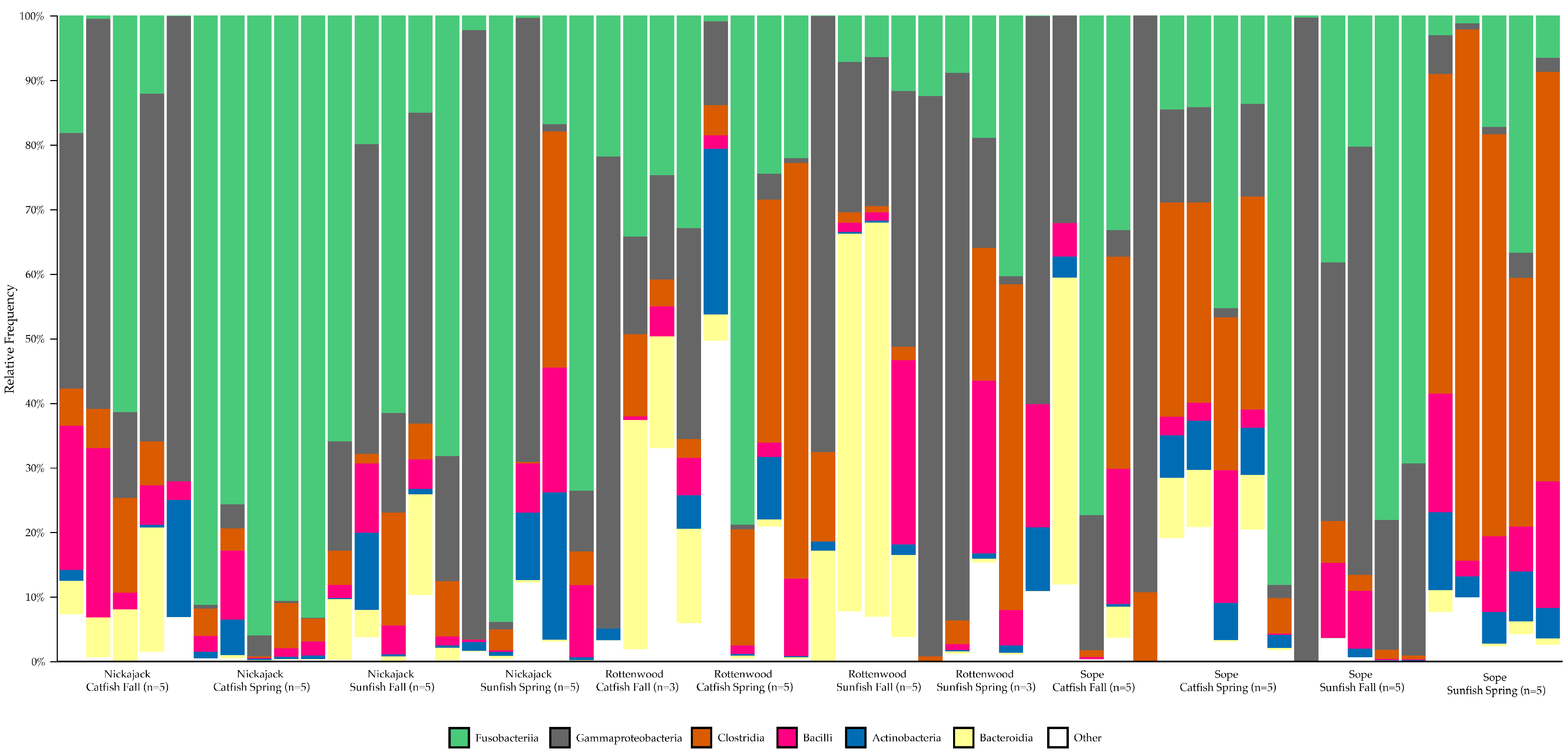

3.4. Representation of Taxa

4. Discussion

4.1. Modulating Factors in Fish GIM

4.2. Study Design and Host Findings

4.3. Habitat and Environmental Quality

4.4. Impact of Season

4.5. Dominance, Richness, and Nutrient Load

4.6. Ecological Interpretation and ASV Enrichment

4.7. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANCOM | Analysis of Compositions of Microbiomes. |

| GIMs | Gastrointestinal Microbiomes. |

| TMDL | Total Maximum Daily Load. |

| QIIME2 | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology. |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variants. |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. |

| HSI | Hepatosomatic Index. |

| DADA | Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm. |

| PCoA | Principle Component Analysis. |

| UniFrac | Unique Fraction Metric. |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance. |

Appendix A

| Sample-id | Length | Weight | Fulton’s Condition | Liver_Weight | Hepatosomatic_Index | Phosphorous | Dissolved_O2 | Water Temperature | Coliforms | pH | Nitrate | Fish_Age | Stream | Species | Season |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| q2:types | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | numeric | categorical | categorical | categorical |

| F1 | 14.9 | 58.46 | 1.77 | 0.67 | 0.0114608 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 4 | Nickajack | sunfish | Fall |

| F2 | 15.1 | 67.18 | 1.95 | 0.97 | 0.0144388 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 4 | Nickajack | sunfish | Fall |

| F3 | 15.4 | 64.74 | 1.77 | 0.55 | 0.0084955 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Fall |

| F4 | 13.1 | 34.8 | 1.55 | 0.58 | 0.0166667 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 4 | Nickajack | sunfish | Fall |

| F5 | 12.6 | 38.38 | 1.92 | 0.27 | 0.0070349 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 4 | Nickajack | sunfish | Fall |

| F6 | 11.2 | 16.42 | 1.17 | 0.23 | 0.0140073 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 1 | Nickajack | catfish | Fall |

| F7 | 20.2 | 105.44 | 1.28 | 1.63 | 0.015459 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 3 | Nickajack | catfish | Fall |

| F8 | 10.8 | 15.49 | 1.23 | 0.27 | 0.0174306 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 1 | Nickajack | catfish | Fall |

| F9 | 11.5 | 17.6 | 1.16 | 0.13 | 0.0073864 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 1 | Nickajack | catfish | Fall |

| F10 | 17.8 | 66.56 | 1.18 | 1.63 | 0.0244892 | 0.9 | 8.8 | 4.8 °C | 18 | 7 | 1.8 | 2 | Nickajack | catfish | Fall |

| F11 | 12.1 | 31.8 | 1.80 | 0.29 | 0.0091195 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 4 | Sope | sunfish | Fall |

| F12 | 12.7 | 38.9 | 1.90 | 0.37 | 0.0095116 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 4 | Sope | sunfish | Fall |

| F13 | 11.3 | 27.3 | 1.89 | 0.25 | 0.0091575 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 2 | Sope | sunfish | Fall |

| F14 | 17.5 | 109.4 | 2.04 | 0.9 | 0.0082267 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 6 | Sope | sunfish | Fall |

| F15 | 16.5 | 61.7 | 1.37 | 0.57 | 0.0092383 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 5 | Sope | sunfish | Fall |

| F16 | 20.6 | 96.2 | 1.10 | 1.19 | 0.0123701 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 5 | Sope | catfish | Fall |

| F17 | 22.2 | 120.7 | 1.10 | 1.6 | 0.013256 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 6 | Sope | catfish | Fall |

| F18 | 19.5 | 91.5 | 1.23 | 1.37 | 0.0149727 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 5 | Sope | catfish | Fall |

| F19 | 19.2 | 78.4 | 1.11 | 0.85 | 0.0108418 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 4 | Sope | catfish | Fall |

| F20 | 16.1 | 55.8 | 1.34 | 0.8 | 0.0143369 | 2.5 | 2 | 4.6 °C | 110 | 6 | 2.25 | 4 | Sope | catfish | Fall |

| F21 | 11.9 | 33.1 | 1.96 | 0.22 | 0.0066465 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Fall |

| F22 | 14.1 | 52.7 | 1.88 | 0.53 | 0.0100569 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Fall |

| F23 | 12.4 | 37.2 | 1.95 | 0.34 | 0.0091398 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Fall |

| F24 | 13.4 | 39.8 | 1.65 | 0.3 | 0.0075377 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Fall |

| F25 | 11.8 | 31.8 | 1.94 | 0.37 | 0.0116352 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Fall |

| F26 | 18 | 61 | 1.05 | 0.87 | 0.0142623 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 3 | Rottenwood | catfish | Fall |

| F27 | 19.6 | 98.4 | 1.31 | 1.51 | 0.0153455 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Fall |

| F28 | 19.1 | 77 | 1.11 | 1.31 | 0.017013 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Fall |

| F29 | 15.4 | 37.5 | 1.03 | 0.6 | 0.016 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2 | Rottenwood | catfish | Fall |

| F30 | 16 | 47.6 | 1.16 | 0.73 | 0.0153361 | 1.1 | 8.1 | 4.9 °C | 23 | 6.8 | 2.4 | 3 | Rottenwood | catfish | Fall |

| S1 | 15.4 | 58.96 | 1.61 | 1.17 | 0.5114608 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Spring |

| S2 | 15.6 | 67.68 | 1.78 | 1.47 | 0.5144388 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Spring |

| S3 | 15.9 | 65.24 | 1.62 | 1.05 | 0.5084955 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 5.5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Spring |

| S4 | 13.6 | 35.3 | 1.40 | 1.08 | 0.5166667 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Spring |

| S5 | 13.1 | 38.88 | 1.73 | 0.77 | 0.5070349 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 4.5 | Nickajack | sunfish | Spring |

| S6 | 11.7 | 16.92 | 1.06 | 0.73 | 0.5140073 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | Nickajack | catfish | Spring |

| S7 | 20.7 | 105.94 | 1.19 | 2.13 | 0.515459 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 | Nickajack | catfish | Spring |

| S8 | 11.3 | 15.99 | 1.11 | 0.77 | 0.5174306 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | Nickajack | catfish | Spring |

| S9 | 12 | 18.1 | 1.05 | 0.63 | 0.5073864 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 | Nickajack | catfish | Spring |

| S10 | 18.3 | 67.06 | 1.09 | 2.13 | 0.5244892 | 1.4 | 9.3 | 4.0 °C | 18.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | Nickajack | catfish | Spring |

| S11 | 12.6 | 32.3 | 1.61 | 0.79 | 0.5091195 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 4.5 | Sope | sunfish | Spring |

| S12 | 13.2 | 39.4 | 1.71 | 0.87 | 0.5095116 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 4.5 | Sope | sunfish | Spring |

| S13 | 11.8 | 27.8 | 1.69 | 0.75 | 0.5091575 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 2.5 | Sope | sunfish | Spring |

| S14 | 18 | 109.9 | 1.88 | 1.4 | 0.5082267 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 6.5 | Sope | sunfish | Spring |

| S15 | 17 | 62.2 | 1.27 | 1.07 | 0.5092383 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 5.5 | Sope | sunfish | Spring |

| S16 | 21.1 | 96.7 | 1.03 | 1.69 | 0.5123701 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 5.5 | Sope | catfish | Spring |

| S17 | 22.7 | 121.2 | 1.04 | 2.1 | 0.513256 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 6.5 | Sope | catfish | Spring |

| S18 | 20 | 92 | 1.15 | 1.87 | 0.5149727 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 5.5 | Sope | catfish | Spring |

| S19 | 19.7 | 78.9 | 1.03 | 1.35 | 0.5108418 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 4.5 | Sope | catfish | Spring |

| S20 | 16.6 | 56.3 | 1.23 | 1.3 | 0.5143369 | 3 | 2.5 | 4.1 °C | 111 | 6.5 | 2.75 | 4.5 | Sope | catfish | Spring |

| S21 | 12.4 | 33.6 | 1.76 | 0.72 | 0.5066465 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Spring |

| S22 | 14.6 | 53.2 | 1.71 | 1.03 | 0.5100569 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Spring |

| S24 | 12.9 | 37.7 | 1.76 | 0.84 | 0.5091398 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Spring |

| S25 | 13.9 | 40.3 | 1.50 | 0.8 | 0.5075377 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | sunfish | Spring |

| S26 | 12.3 | 32.3 | 1.74 | 0.87 | 0.5116352 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Spring |

| S27 | 18.5 | 61.5 | 0.97 | 1.37 | 0.5142623 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 3.5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Spring |

| S28 | 20.1 | 98.9 | 1.22 | 2.01 | 0.5153455 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 5.5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Spring |

| S29 | 19.6 | 77.5 | 1.03 | 1.81 | 0.517013 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 5.5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Spring |

| S30 | 15.9 | 38 | 0.95 | 1.1 | 0.516 | 1.6 | 8.6 | 4.3 °C | 23.5 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | Rottenwood | catfish | Spring |

Appendix B

| Stream | Season | Species | Total Sequences | Chao1 | Shannon’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickajack | Fall | Ameiurus brunneus | 8533.6 ± 2795 | 63.4 ± 22.9 | 3.75 ± 0.73 |

| Lepomis auritus | 12,823.8 ± 4446 | 77.3 ± 31.3 | 3.24 ± 0.77 | ||

| Spring | Ameiurus brunneus | 179,553.6 ± 53,305 | 101.9 ± 41.4 | 1.22 ± 0.82 | |

| Lepomis auritus | 84,998 ± 13,290 | 210.9 ± 196.9 | 2.73 ± 1.39 | ||

| Sope | Fall | Ameiurus brunneus | 9398.25 ± 5538 | 38.3 ± 11.58 | 2.83 ± 1.04 |

| Lepomis auritus | 8092.6 ± 4009 | 27.40 ± 16.80 | 2.06 ± 1.40 | ||

| Spring | Ameiurus brunneus | 83,728 ± 65,103 | 216.7 ± 68.04 | 4.89 ± 1.94 | |

| Lepomis auritus | 37,539.8 ± 9242 | 196.5 ± 44.26 | 5.03 ± 0.53 | ||

| Rottenwood | Fall | Ameiurus brunneus | 13,287 ± 1618 | 61.5 ± 27.8 | 3.36 ± 0.19 |

| Lepomis auritus | 15,785.6 ±11,549 | 31.47 ± 6.2 | 3.08 ± 0.56 | ||

| Spring | Ameiurus brunneus | 84,114.8 ± 20,373 | 383.4 ± 330.6 | 4.58 ± 2.34 | |

| Lepomis auritus | 133,984 ± 105,954 | 218.0 ± 11.5 | 3.67 ± 1.56 |

Appendix C

| Fall Nickajack Sunfish | Spring Nickajack Sunfish | Fall Sope Sunfish | Spring Sope Sunfish | Fall Rottenwood Sunfish | Spring Rottenwood Sunfish | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinomycetia | 9.9 | 9.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

| Bacilli | 1.8 | 0.7 | 5.9 | 1.0 | 7.5 | 0.8 |

| Bacteroidia | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.0 |

| Clostridia | 19.1 | 32.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 5.5 | 21.9 |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 3.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Fusobacteriia | 13.2 | 29.6 | 19.7 | 7.3 | 2.6 | 23.2 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 12.3 | 15.0 | 20.7 | 1.7 | 21.7 | 1.1 |

| Other | 38.2 | 13.1 | 49.0 | 84.3 | 53.6 | 51.3 |

| Fall Nickajack Catfish | Spring Nickajack Catfish | Fall Sope Catfish | Spring Sope Catfish | Fall Rottenwood Catfish | Spring Rottenwood Catfish | |

| Actinomycetia | 13.7 | 1.9 | 13.4 | 3.7 | 12.9 | 2.6 |

| Bacilli | 8.0 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 9.5 | 3.4 | 7.3 |

| Bacteroidia | 1.5 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 5.4 | 0.2 |

| Clostridia | 13.7 | 2.0 | 12.6 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 12.8 |

| Deltaproteobacteria | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 6.5 | 1.8 |

| Fusobacteriia | 6.9 | 4.8 | 16.2 | 23.4 | 6.1 | 9.8 |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 15.8 | 8.1 | 19.8 | 3.3 | 12.8 | 25.7 |

| Other | 40.4 | 81.4 | 25.5 | 47.8 | 42.5 | 39.8 |

Appendix D

| Nickajack | Sope | Rottenwood | Sunfish | Catfish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriia | Two Fusobacteriia | Fusobacteriia |

| Bacilli | Gammaproteobacteria | Clostridia | Five Clostridia | Actinomycetia |

| Actinomycetia | Bacteroidia | Two Actinomycetia | Three Gammaproteobacteria | Two Clostridia |

| Bacteroidia | ||||

| Bacilli | ||||

| Actinomycetia |

Appendix E

| Margelef | Ace | Dominance | Faith-pd | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Pr | F | Pr | F | Pr | F | Pr | |

| Species | 0.6584 | 0.5100 | 0.6923 | 0.4866 | 0.5885 | 0.5492 | 0.8441 | 0.39356 |

| Site | 3.1361 | 0.0215 | 3.3201 | 0.0180 | 3.4619 | 0.0161 | 3.7940 | 0.0142 |

| Season | 74.2100 | 1 × 10−5 | 87.6113 | 1 × 10−5 | 3.4174 | 0.0396 | 136.0864 | 1 × 10−5 |

| Species*Site | 0.8268 | 0.4901 | 0.6794 | 0.5998 | 0.2924 | 0.8972 | 0.8354 | 0.4719 |

| Species*Season | 0.2356 | 0.8663 | 0.2174 | 0.8741 | 2.5047 | 0.0865 | 0.0572 | 0.97238 |

| Site*Season | 3.3304 | 0.0168 | 3.0685 | 0.0246 | 6.4056 | 0.0005 | 4.2559 | 0.0087 |

| McIntosh | Shannon | Simpson | Evenness | |||||

| F | Pr | F | Pr | F | Pr | F | Pr | |

| Species | 0.5147 | 0.5242 | 0.8480 | 0.4148 | 1.1628 | 0.2875 | 0.4089 | 0.6605 |

| Site | 3.8489 | 0.01915 | 2.8620 | 0.0245 | 45.3082 | 1 × 10−5 | 4.1598 | 0.0079 |

| Season | 2.3250 | 0.1168 | 2.3506 | 0.0841 | 7.8943 | 0.0021 | 3.0234 | 0.0607 |

| Species*Site | 0.1743 | 0.9217 | 1.3821 | 0.2179 | 0.7114 | 0.5599 | 1.4311 | 0.2214 |

| Species*Season | 2.0206 | 0.1480 | 2.8158 | 0.0550 | 1.6740 | 0.1781 | 3.7939 | 0.0348 |

| Site*Season | 8.6284 | 0.0002 | 8.0755 | 2 × 10−5 | 9.1323 | 7 × 10−5 | 7.1017 | 0.0003 |

References

- Antwis, R.E.; Harrison, X.A.; Cox, M.J. (Eds.) Microbiomes of Soils, Plants and Animals: An Integrated Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tarnecki, A.M.; Burgos, F.A.; Ray, C.L.; Arias, C.R. Fish Intestinal Microbiome: Diversity and Symbiosis Unravelled by Metagenomics. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2017, 123, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Gooneratne, R.; Lai, R.; Zeng, C.; Zhan, F.; Wang, W. The Gut Microbiome and Degradation Enzyme Activity of Wild Freshwater Fishes Influenced by Their Trophic Levels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Rawls, J.F. Intestinal Microbiota Composition in Fishes Is Influenced by Host Ecology and Environment. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 3100–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullam, K.E.; Rubin, B.E.; Dalton, C.M.; Kilham, S.S.; Flecker, A.S.; Russell, J.A. Divergence across Diet, Time and Populations Rules out Parallel Evolution in the Gut Microbiomes of Trinidadian Guppies. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1508–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmiller, J.J.; Hamilton, M.J.; Staley, C.; Sadowsky, M.J.; Sorensen, P.W. Environment Shapes the Fecal Microbiome of Invasive Carp Species. Microbiome 2016, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, T.P.R.A.; Wynne, J.W.; Weyrich, L.S.; Oxley, A.P.A. A Microbial Sea of Possibilities: Current Knowledge and Prospects for an Improved Understanding of the Fish Microbiome. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 1101–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.R.; Ran, C.; Ringø, E.; Zhou, Z.G. Progress in Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiota Research. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 626–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, M.S.; Boutin, S.; Hoseinifar, S.H.; Derome, N. Teleost Microbiomes: The State of the Art in Their Characterization, Manipulation and Importance in Aquaculture and Fisheries. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.P.; Junaid, M.; Xin, G.Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.B.; Pei, D.S. Disruption of Intestinal Homeostasis Through Altered Responses of the Microbial Community, Energy Metabolites, and Immune System in Zebrafish After Chronic Exposure to DEHP. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 729530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bledsoe, J.W.; Peterson, B.C.; Swanson, K.S.; Small, B.C. Ontogenetic Characterization of the Intestinal Microbiota of Channel Catfish through 16S RRNA Gene Sequencing Reveals Insights on Temporal Shifts and the Influence of Environmental Microbes. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanika, N.H.; Liaqat, N.; Chen, H.; Ke, J.; Lu, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, C. Fish Gut Microbiome and Its Application in Aquaculture and Biological Conservation. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1521048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Background Document on the Risks and Benefits of Fish Consumption; Food Safety and Quality Series; FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Villéger, S.; Brosse, S.; Mouchet, M.; Mouillot, D.; Vanni, M.J. Functional Ecology of Fish: Current Approaches and Future Challenges. Aquat. Sci. 2017, 79, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carthey, A.J.R.; Blumstein, D.T.; Gallagher, R.V.; Tetu, S.G.; Gillings, M.R. Conserving the Holobiont. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 34, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevelline, B.K.; Fontaine, S.S.; Hartup, B.K.; Kohl, K.D. Conservation Biology Needs a Microbial Renaissance: A Call for the Consideration of Host-Associated Microbiota in Wildlife Management Practices. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 286, 20182448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegunloye, D.V.; Sanusi, A.I. Microbiota of Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) Tissues Harvested from Vials Polluted with Soil from e-Wastes Dumpsite. Int. J. Fish. Aquac. 2019, 11, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolorbe-Payahua, C.D.; de Freitas, A.S.; Roesch, L.F.W.; Zanette, J. Environmental Contamination Alters the Intestinal Microbial Community of the Livebearer Killifish Phalloceros Caudimaculatus. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chupani, L.; Barta, J.; Zuskova, E. Effects of Food-Borne ZnO Nanoparticles on Intestinal Microbiota of Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 25869–25873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restivo, V.E.; Kidd, K.A.; Surette, M.G.; Servos, M.R.; Wilson, J.Y. Rainbow Darter (Etheostoma caeruleum) from a River Impacted by Municipal Wastewater Effluents Have Altered Gut Content Microbiomes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Lu, W.; Hong, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, S.; Huang, Q. Long-Term Wet Precipitation of PM2.5 Disturbed the Gut Microbiome and Inhibited the Growth of Marine Medaka Oryzias melastigma. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theis, K.R.; White, J. Editorial: Impact of Anthropogenic Environmental Changes on Animal Microbiomes. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1204035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namasivayam, S.K.R.; Poornima, V. An Investigation of Polymer Coated Metallic Nanoparticles Mediated Influence on Gut Microbiota of Zebra Fish (Danio rerio). Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2017, 10, 2221–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fackelmann, G.; Sommer, S. Microplastics and the Gut Microbiome: How Chronically Exposed Species May Suffer from Gut Dysbiosis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 143, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamovsky, O.; Buerger, A.N.; Wormington, A.M.; Ector, N.; Griffitt, R.J.; Bisesi, J.H.; Martyniuk, C.J. The Gut Microbiome and Aquatic Toxicology: An Emerging Concept for Environmental Health. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2758–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degregori, S.; Casey, J.M.; Barber, P.H. Nutrient Pollution Alters the Gut Microbiome of a Territorial Reef Fish. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajima, D.; Fujita, H.; Hayashi, I.; Shima, G.; Suzuki, K.; Toju, H. Core Species and Interactions Prominent in Fish-Associated Microbiome Dynamics. Microbiome 2023, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.G.; Harris, C.R.; Kalis, K.M.; Bowen, M.; Biddle, J.F.; Farag, I.F. Comparative Metagenomics of Tropical Reef Fishes Show Conserved Core Gut Functions across Hosts and Diets with Diet-Related Functional Gene Enrichments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e02229-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwan, A.D.; Harke, S.N.; Panche, A.N. Host-Microbiome Interaction in Fish and Shellfish: An Overview. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. Rep. 2023, 4, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulski, T.; Kozłowski, K.; Ciesielski, S. Habitat and Seasonality Shape the Structure of Tench (Tinca tinca L.) Gut Microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, D.; Turner, S.J.; Clements, K.D. Ontogenetic Development of the Gastrointestinal Microbiota in the Marine Herbivorous Fish Kyphosus sydneyanus. Microb. Ecol. 2005, 49, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Refaey, M.M.; Xu, W.; Tang, R.; Li, L. Host Age Affects the Development of Southern Catfish Gut Bacterial Community Divergent from That in the Food and Rearing Water. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Kneifel, W.; Domig, K.J. A New View of the Fish Gut Microbiome: Advances from next-Generation Sequencing. Aquaculture 2015, 448, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, B.D.; Farrell, J.M.; Leydet, B. Use of next Generation Sequencing to Compare Simple Habitat and Species Level Differences in the Gut Microbiota of an Invasive and Native Freshwater Fish Species. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, C.R.; Ray, L.; Cai, W.; Willmon, E. Fish Are Not Alone: Characterization of the Gut and Skin Microbiomes of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), and Spotted Gar (Lepisosteus oculatus). SDRP J. Aquac. Fish Fish. Sci. 2019, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, B.D.; Farrell, J.M.; Leydet, B.F. Fish Gut Microbiome: A Primer to an Emerging Discipline in the Fisheries Sciences. Fisheries 2020, 45, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaris, P.C.; Jesien, R.V.; Pinkney, A.E. Brown Bullhead as an Indicator Species: Seasonal Movement Patterns and Home Ranges within the Anacostia River, Washington, D.C. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2005, 134, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschung, H.T.; Mayden, R.L. Fishes of Alabama; Smithsonian Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parata, L.; Nielsen, S.; Xing, X.; Thomas, T.; Egan, S.; Vergés, A. Age, Gut Location and Diet Impact the Gut Microbiome of a Tropical Herbivorous Surgeonfish. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiz179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Sudduth, E.B.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Wright, J.P.; Bernhardt, E.S. Watershed Urbanization Alters the Composition and Function of Stream Bacterial Communities. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, N.; Qi, X.; Zeng, J.; Cui, K.; Lu, W.; Bai, S. Variations and Interseasonal Changes in the Gut Microbial Communities of Seven Wild Fish Species in a Natural Lake with Limited Water Exchange during the Closed Fishing Season. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, P.S.; Shin, N.-R.; Lee, J.-B.; Kim, M.-S.; Whon, T.W.; Hyun, D.-W.; Yun, J.-H.; Jung, M.-J.; Kim, J.Y.; Bae, J.-W. Host Habitat Is the Major Determinant of the Gut Microbiome of Fish. Microbiome 2021, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolas, I.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Teame, T.; Olsen, R.E.; Ringø, E.; Rønnestad, I. A Fishy Gut Feeling—Current Knowledge on Gut Microbiota in Teleosts. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 4795373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.K.; Thakur, K.; Kumari, H.; Mahajan, D.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, B.; Pankaj, P.P.; Kumar, R. A Review on Comparative Analysis of Marine and Freshwater Fish Gut Microbiomes: Insights into Environmental Impact on Gut Microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiae169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.M.; Stewart, D.R. Verification of Otolith Identity Used by Fisheries Scientists for Aging Channel Catfish. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 2010, 139, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaris, P.C.; Bonvechio, T.F. Comparison of Two Otolith Processing Methods for Estimating Age of Three Catfish Species. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2021, 41, S428–S439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J.; Angert, E.R. DNA Replication during Endospore Development in Metabacterium Polyspora. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 67, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassol, I.; Ibañez, M.; Bustamante, J.P. Key Features and Guidelines for the Application of Microbial Alpha Diversity Metrics. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, M.A.M.; Mohamed, W.M.A.; Lau, A.C.C.; Chatanga, E.; Qiu, Y.; Hayashi, N.; Naguib, D.; Sato, K.; Takano, A.; Matsuno, K.; et al. R A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Foundation for Statistical. Computing 2020, 20. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Bereded, N.K.; Abebe, G.B.; Fanta, S.W.; Curto, M.; Waidbacher, H.; Meimberg, H.; Domig, K.J. The Impact of Sampling Season and Catching Site (Wild and Aquaculture) on Gut Microbiota Composition and Diversity of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Biology 2021, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.L.; Volkoff, H. Gut Microbiota and Energy Homeostasis in Fish. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogdahl, A.; Sundby, A.; Bakke, A.M. Integrated Function and Control of the Gut | Gut Secretion and Digestion; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 2, ISBN 9780080923239. [Google Scholar]

- Sehnal, L.; Brammer-Robbins, E.; Wormington, A.M.; Blaha, L.; Bisesi, J.; Larkin, I.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Simonin, M.; Adamovsky, O. Microbiome Composition and Function in Aquatic Vertebrates: Small Organisms Making Big Impacts on Aquatic Animal Health. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 567408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J.F.; Mahowald, M.A.; Ley, R.E.; Gordon, J.I. Reciprocal Gut Microbiota Transplants from Zebrafish and Mice to Germ-Free Recipients Reveal Host Habitat Selection. Cell 2006, 127, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egerton, S.; Culloty, S.; Whooley, J.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. The Gut Microbiota of Marine Fish. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Sham, R.C.; Deng, Y.; Mao, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Leung, K.M.Y. Diversity of Gut Microbiomes in Marine Fishes Is Shaped by Host-Related Factors. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 5019–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvain, F.É.; Holland, A.; Bouslama, S.; Audet-Gilbert, É.; Lavoie, C.; Luis Val, A.; Derome, N. Fish Skin and Gut Microbiomes Show Contrasting Signatures of Host Species and Habitat. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00789-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Long, M.; Li, H.; Gatesoupe, F.J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, D.; Li, A. Multi-Omics Analysis Reveals a Correlation between the Host Phylogeny, Gut Microbiota and Metabolite Profiles in Cyprinid Fishes. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Tan, H.; Yang, C.; Ren, L.; Liu, Q.; Wang, S.; Hu, F.; Xiao, J.; Zhao, R.; et al. Genetic Effects on the Gut Microbiota Assemblages of Hybrid Fish from Parents with Different Feeding Habits. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullam, K.E.; Essinger, S.D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Connor, M.P.O. Environmental and Ecological Factors That Shape the Gut 2 Bacterial Communities of Fish: A Meta-Analysis—Supplementary. PubMed Cent. 2009, 21, 3363–3378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkoff, H.; Rønnestad, I. Effects of Temperature on Feeding and Digestive Processes in Fish. Temperature 2020, 7, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.B.; Hellmann, J.J.; Ricketts, T.H.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Sinclair, L.; Osman, O.A.; Bertilsson, S.; Eiler, A.; Sala, V.; De Faveri, E.; et al. Counting the Uncountable: Statistical Approaches to Estimating Microbial Diversity MINIREVIEW Counting the Uncountable: Statistical Approaches to Estimating Microbial Diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 10, 4399–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Van Treuren, W.; White, R.A.; Eggesbø, M.; Knight, R.; Peddada, S.D. Analysis of Composition of Microbiomes: A Novel Method for Studying Microbial Composition. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 27663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiersztyn, B.; Chróst, R.; Kaliński, T.; Siuda, W.; Bukowska, A.; Kowalczyk, G.; Grabowska, K. Structural and Functional Microbial Diversity along a Eutrophication Gradient of Interconnected Lakes Undergoing Anthropopressure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, W.E. Computation and Interpretation of Biological Statistics of Fish Populations; Bulletin of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1975; Volume 191, pp. 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Józefiak, A.; Nogales-Mérida, S.; Rawski, M.; Kierończyk, B.; Mazurkiewicz, J. Effects of Insect Diets on the Gastrointestinal Tract Health and Growth Performance of Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser baerii Brandt, 1869). BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcés, M.E.; Olivera, N.L.; Fernández, M.; Riva Rossi, C.; Sequeiros, C. Antimicrobial Activity of Bacteriocin-producing Carnobacterium spp. Isolated from Healthy Patagonian Trout and Their Potential for Use in Aquaculture. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 4602–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ke, L.; Huang, C.; Peng, S.; Zhao, M.; Wu, H.; Lin, F. Effects of Seawater from Different Sea Areas on Abalone Gastrointestinal Microorganisms and Metabolites. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Hamid, N.; Deng, S.; Jia, P.-P.; Pei, D.-S. Individual and Combined Toxicogenetic Effects of Microplastics and Heavy Metals (Cd, Pb, and Zn) Perturb Gut Microbiota Homeostasis and Gonadal Development in Marine Medaka (Oryzias melastigma). J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 397, 122795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Huttenhower, C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.J.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2-SC: An Update to the Reference Database Used for Functional Prediction within PICRUSt2. Bioinformatics 2025, 41, btaf269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delgado, D.; Dustman, W.; Erickson, K.; Kurtz, L.; King-Keller, S.; Sakaris, P.; Ward, R. Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alterations Associated with Environmental and Host Factors. Fishes 2025, 10, 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120633

Delgado D, Dustman W, Erickson K, Kurtz L, King-Keller S, Sakaris P, Ward R. Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alterations Associated with Environmental and Host Factors. Fishes. 2025; 10(12):633. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120633

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelgado, Daniel, Wendy Dustman, Keith Erickson, Lee Kurtz, Sharon King-Keller, Peter Sakaris, and Rebekah Ward. 2025. "Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alterations Associated with Environmental and Host Factors" Fishes 10, no. 12: 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120633

APA StyleDelgado, D., Dustman, W., Erickson, K., Kurtz, L., King-Keller, S., Sakaris, P., & Ward, R. (2025). Fish Gastrointestinal Microbiome Alterations Associated with Environmental and Host Factors. Fishes, 10(12), 633. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10120633