Abstract

Background: Grapevine breeding increasingly relies on molecular tools to introduce durable resistance to downy and powdery mildew. However, the reproducibility of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers across platforms remains a challenge for marker-assisted selection (MAS). This study aimed to evaluate the performance of SSR markers associated with key resistance loci (Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, Rpv10, Rpv12) using the Qsep100 system and to validate selected markers on the ABI platform. Methods: A panel of grapevine cultivars and breeding genotypes was analyzed for SSR markers linked to resistance loci. PCR amplicons were separated on the Qsep100 BioFragment Analyzer, and a subset of markers was cross-validated using ABI capillary electrophoresis. Results: Only a limited subset of markers displayed consistent performance across genotypes. Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 were most reliable for Run1/Rpv1, Indel-27 and Indel-20 for Ren3/Ren9, UDV737 for all Rpv3 sub-loci, GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 for Rpv10, and UDV340 and UDV343 for Rpv12. ABI validation of UDV737 and Indel-27 confirmed high concordance with Qsep100 results, with allele size differences typically ≤2 bp. Conclusions: The study identifies a core set of robust SSR markers suitable for routine MAS in grapevine breeding. Results demonstrate that the Qsep100 system is a reliable alternative to ABI for large-scale genotyping, supporting its broader implementation in resistance breeding programs.

1. Introduction

Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the most economically important fruit crops worldwide, but its cultivation is severely limited by fungal diseases. Among these, downy mildew caused by Plasmopara viticola and powdery mildew caused by Erysiphe necator are the most destructive, often resulting in significant yield losses and reduced grape quality if not properly controlled. Traditionally, viticulture has depended on intensive fungicide applications to manage these pathogens, often requiring 10 to 15 treatments per season in susceptible cultivars under humid conditions. This heavy chemical use increases production costs and raises concerns about environmental sustainability, human health, and the development of fungicide resistance [1,2].

Recent advances have deepened the understanding of the infection biology of P. viticola, including the molecular mechanisms underlying pathogen–host interactions, effector proteins, and host defense responses [3]. These insights offer important opportunities for targeted breeding of resistant grapevine cultivars and the development of innovative control strategies. At the same time, integrated pest management (IPM) approaches have been promoted to reduce reliance on chemical control by combining canopy management, predictive models, and biocontrol agents [4]. However, chemical protection remains indispensable in regions with high disease pressure, highlighting the urgent need for more sustainable solutions. Breeding resistant cultivars is a cornerstone of future viticulture, aligning with climate change challenges and societal demands for environmentally friendly wine production [1,2,3,4].

One of the most promising strategies for achieving durable and environmentally friendly disease control in grapevine is the exploitation of genetic resistance. Over the past two decades, numerous resistance loci against downy mildew and powdery mildew have been identified and mapped in diverse Vitis germplasm. Among the best characterized are Rpv3 from the cultivar ‘Bianca’, which confers partial resistance to downy mildew on chromosome 18 [5], and Rpv10, introgressed from Vitis amurensis, which provides strong resistance [6]. Similarly, Rpv12, also derived from V. amurensis, has been shown to act additively with Rpv3 [7]. Evidence of a selective sweep around the Rpv3 locus further demonstrates its key role in modern breeding programs [8]. For powdery mildew resistance, several loci have been identified, including Ren3 and Ren9, both validated in different segregating populations [9], as well as other Run and Ren loci distributed across the Vitis genome [10]. Comparative analyses have highlighted functional differences in defense responses mediated by Rpv3, Rpv10, and Rpv12 [11], while molecular studies have revealed unique defense mechanisms activated by individual loci such as Ren2, Ren3, and Ren4 [12]. More recently, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified novel loci [13], and comparative genomic studies have illustrated the complex haplotype structure of the Rpv3 region [14].

The integration of these loci into breeding programs has been greatly facilitated by marker-assisted selection (MAS), which enables early identification of resistant genotypes in segregating progenies. This approach reduces the need for time-consuming phenotypic evaluations in the field and accelerates the release of resistant cultivars [15]. Practical applications have shown that pyramiding Rpv and Ren/Run loci can produce progenies with enhanced resistance levels and reduced fungicide requirements [16,17]. Integrated strategies such as the ResDur program demonstrate the value of MAS in combining multiple resistance loci into elite germplasm [18,19]. The efficiency of MAS has been further supported by the development of high-throughput genotyping tools, including SNP arrays and standardized SSR panels [20,21], which allow precise cultivar identification, pedigree analysis, and validation of parent–offspring relationships [22]. Complementary phenotyping protocols strengthen the link between genotypic data and resistance expression [23], making MAS a cornerstone of sustainable grapevine breeding strategies [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23].

The utility of MAS depends on robust and reproducible marker analysis. SSRs remain a standard choice for grapevine genotyping because of their high polymorphism and codominant inheritance [24]. Although capillary electrophoresis on ABI Genetic Analyzer platforms has been considered the gold standard, new systems such as the Qsep100 fragment analyzer are being evaluated as cost-effective and efficient alternatives [25]. Capillary electrophoresis has been widely used in plant sciences for DNA fragment sizing [26], and new tools such as the Fragman R package facilitate more consistent allele scoring [27]. Compact CE platforms like Spectrum Compact have demonstrated resolution and accuracy comparable to ABI instruments [28], while reproducibility studies highlight the importance of careful marker validation for breeding applications [29].

To ensure comparability of genotyping results across laboratories, standardized SSR panels have been developed. Establishing a core set of reference SSR alleles has provided a foundation for harmonized protocols worldwide [30], supported by large multiplexable panels for higher throughput [31] and the design of long-core repeat SSRs to improve allele readability [32]. Recent evaluations have confirmed the informativeness of the OIV-recommended loci [33], while EST-derived SSRs have added functional relevance [34]. Review studies highlight the importance of methodological consistency and marker validation [35], and the Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC) serves as an essential global repository of SSR profiles linked to ampelographic and historical data [36]. Additionally, recent studies have demonstrated the utility of SSRs for the genetic characterization of large grapevine collections, further underscoring their relevance for germplasm conservation and breeding programs [37].

Despite the availability of numerous SSR markers and established protocols, the reproducibility and efficiency of specific markers can vary across platforms, creating a need for systematic evaluation. To our knowledge, a comprehensive assessment of marker performance across the major grapevine resistance loci (Run1, Ren3, Ren9, Rpv1, Rpv3, Rpv10, and Rpv12) has not been previously reported. In this study, we evaluated a panel of SSR markers linked to these loci in grapevine progenies derived from controlled crosses. Marker performance was analyzed using the Qsep100 Bio-Fragment Analyzer (Cartridge (BiOptic Inc., New Taipei City, Taiwan)), with a subset validated against ABI platform results to benchmark accuracy. Our aim was to identify the most reliable markers for routine application in marker-assisted selection programs, thereby contributing to the development of a standardized, reproducible, and cost-effective genotyping pipeline for grapevine resistance breeding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Young leaves from the grapevine cultivars listed in Table 1 were collected from the PIWI (germ. Pilzwiderstandsfähige Rebsorten) cultivar collection maintained at the Experimental Station Jazbina of the University of Zagreb, Faculty of Agriculture. The cultivars included in this study were selected because the presence of specific resistance loci (Run, Ren, and Rpv) has been reported for these genotypes in previous studies, making them suitable reference material for marker validation. A total of 37 cultivars from different geographical origins (Germany, France, Italy, Hungary, and Serbia) were sampled to ensure broad representation of resistance loci (Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, and Rpv12). For each locus under investigation, cultivars with a confirmed presence of the corresponding resistance locus were included as positive controls, allowing direct evaluation of SSR marker performance. Cultivars without reported resistance loci were included as negative controls to assess marker specificity and exclude false-positive amplification. For validation of SSR marker performance on the Qsep100 and ABI platforms, an additional set of grapevine genotypes (listed in Supplementary Table S1) was analyzed. For the final validation and application of the selected SSR markers, a set of cultivars with uncertain or incompletely documented allelic states (“?” in Table 1) was included. These genotypes, including Bačka, Cabernet Volos, Kozmopolita, Merlot Kanthus, Merlot Khorus, SK-90-2/11, Sauvignon Kretos, Soreli, and Sauvignon Rytos, were analyzed to evaluate marker performance in genetic backgrounds where resistance loci had not been fully confirmed. Leaf tissue was collected in the early growing season, immediately frozen, and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was subsequently isolated from the collected samples using a CTAB-based protocol as described below.

Table 1.

Grapevine cultivars included in the study, their origin, and reported resistance loci based on previous studies.

2.2. DNA Extraction

Genomic DNA was isolated from leaf tissue using a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB)-based protocol. Briefly, 1 g of finely ground leaf material was transferred to a 50 mL centrifuge tube containing 10 mL of CTAB extraction buffer (3% CTAB, 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1.4 M NaCl, and 10 mM EDTA). Samples were homogenized using a MiniG tissue homogenizer (SPEX SamplePrep, Metuchen, NJ, USA) at 1500 rpm for 4 min and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After incubation, 2 mL of homogenate was transferred to a 2 mL microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The resulting supernatant (1 mL) was transferred to a new tube, and 2 µL of 2-mercaptoethanol was added before incubation at 65 °C for 20 min. An equal volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1, v/v) was added, and samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The aqueous phase was carefully transferred to a clean microtube, and DNA was precipitated with 1 mL of cold isopropanol, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, vacuum-dried, and resuspended in 400 µL of nuclease-free water. DNA concentration and purity were determined spectrophotometrically using a Lambda XLS + UV/VIS spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer Inc., Shelton, CT, USA) equipped with a TrayCell 2.0 microcuvette (Hellma Analytics, Müllheim, Germany). DNA yield was quantified by absorbance at 260 nm, and purity was assessed using the absorbance ratios A260/280 and A260/230.

2.3. PCR Amplification and SSR Markers

Before PCR amplification, all DNA samples were adjusted to a concentration of 50 ng/µL. PCR was performed using a ProFlex PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the Type-it Microsatellite PCR Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Each 25 µL reaction contained 12.5 µL of Master Mix (including DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and reaction buffer), 2.5 µL of Q-solution, 4.5 µL of nuclease-free water, 2.5 µL of primer mix (forward and reverse primers), and 3 µL of template DNA. Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 57 °C for 90 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. A set of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers was selected to amplify genomic regions associated with known grapevine resistance loci, including Run1/Rpv1, Ren3, Ren9, Rpv3, and Rpv12. Markers were chosen based on their reported linkage to resistance traits and their reproducibility in previous studies. The list of SSR markers used for amplification of resistance-associated loci, including primer sequences and expected product sizes, is provided in Supplementary Table S2 according to previously published data [7,9,39,42,43,44,45,46,47,48].

2.4. Fragment Analysis Using Qsep100

PCR products were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis using the Qsep100 Bio Fragment Analyzer equipped with an S1 High Resolution Cartridge (BiOptic Inc., New Taipei City, Taiwan). Before analysis, PCR products were diluted 1:10 in dilution buffer. Samples were injected at 4 kV for 10 s, and fragments were separated at 6 kV for 300 s. The detection parameters used in this study correspond to the default, manufacturer-recommended settings for the S1 High Resolution Cartridge. These factory-optimized parameters are predefined for fragment analysis of PCR amplicons in the 20–1000 bp range and ensure consistent performance, appropriate resolution, and optimal peak morphology without further user modification. Alignment markers and size markers were included to ensure accurate sizing of DNA fragments. Electropherograms were processed and analyzed using Q-Analyzer software v. 3.4.3.0.6593 (BiOptic Inc., New Taipei City, Taiwan), which enabled determination of allele sizes and peak profiles for each SSR marker.

2.5. ABI Cross-Platform Validation

For targeted cross-platform validation, two SSR markers were selected based on their consistent performance on the Qsep100 system: UDV737, linked to the Rpv3 locus, and Indel-27, linked to the Ren3/Ren9 region. Experimental breeding genotypes were used for this validation (see Supplementary Table S1). Although these are not registered cultivars, they were chosen because they represent informative allelic combinations at the target loci.

PCR reactions were performed as described above, using fluorescently labeled primers suitable for ABI analysis. Amplicons were sent to Macrogen Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea), where they were separated on an ABI capillary electrophoresis platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Allele sizes were scored with GeneMapper software (Applied Biosystems). For each marker, PCR products from the same genotypes were also analyzed on the Qsep100 system to enable direct comparison of allele sizing across platforms. Concordance was assessed by calculating the absolute difference in allele size (Δbp) between ABI and Qsep100 for each allele call. A tolerance of ±2 bp was defined as concordant (match), 3–5 bp as a minor shift, and greater than 5 bp as discordant. Expected allele sizes were taken from the literature (Indel-27: 230 bp; UDV737: 281 bp) and used as reference values in the comparative analysis.

2.6. Intra- and Inter-Day Precision of SSR Marker Analysis

To assess the reproducibility and specificity of SSR genotyping on the Qsep100 system, intra- and inter-day precision analyses were performed. Intra-day precision was evaluated using two independent replicates of PCR amplification and fragment analysis conducted on the same day, while inter-day precision was assessed over four consecutive days using the same DNA extracts. Validation was carried out only with selected markers previously identified as the most informative for each resistance locus: Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 (Run1/Rpv1), Indel-27 and Indel-20 (Ren3/Ren9), UDV305 and UDV737 (Rpv3), GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 (Rpv10), and UDV340 and UDV343 (Rpv12). PCR conditions and Qsep100 analysis parameters were as described above. To strengthen assay specificity, three susceptible cultivars (Graševina, Grk, Maraština) were included as negative controls. These controls enabled verification that allele profiles outside the resistance-associated ranges remained stable and did not overlap with those of resistant genotypes. Precision was expressed as the deviation in allele size (bp) between replicates (intra-day) and between measurements obtained on different days (inter-day). Deviations of ±1–2 bp were considered within the accepted tolerance for SSR genotyping, while consistent allele profiles in negative controls confirmed marker specificity.

2.7. Validation of SSR Marker Performance Across Genotypes

Several cultivars listed in Table 1 were marked with an uncertain resistance status (“?”), as no reliable or consistent information on the presence of major resistance loci (Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, Rpv10, Rpv12) was available from the literature or official breeder reports. These genotypes were therefore subjected to targeted SSR analysis using the optimized marker set selected in this study: Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 (Run1/Rpv1), Indel-27 and Indel-20 (Ren3/Ren9), UDV305 and UDV737 (Rpv3), GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 (Rpv10), and UDV340 and UDV343 (Rpv12). PCR amplification and fragment analysis were performed as described above, and allele scoring followed the same criteria used for reference cultivars with known resistance status. This procedure enabled experimental determination of the presence or absence of resistance-associated alleles in cultivars for which no prior genetic information was available.

3. Results and Discussion

The development of resistant grapevine cultivars through marker-assisted selection (MAS) depends critically on identifying and validating genetic markers that reliably indicate the presence of resistance loci. Although numerous SSR markers have been reported in the literature for loci such as Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, Rpv10, and Rpv12, their reproducibility across diverse genetic backgrounds remains inconsistent [38,42,43,49]. This variability can be attributed to allele size shifts, weak amplification, or the presence of multiple non-specific fragments, all of which complicate allele scoring and reduce the diagnostic reliability of markers. To address these challenges, we evaluated a panel of SSR markers previously associated with resistance to powdery and downy mildew in a set of cultivars carrying the respective loci. The performance of each marker was assessed based on allele size concordance with reference values, signal strength, and reproducibility across genotypes. Markers that consistently produced clear, stable peaks and expected allele sizes were considered the most reliable candidates for MAS. In the following sections, we present the performance of markers for each resistance locus, highlighting the subset of SSRs that can be recommended as robust diagnostic tools for routine application in grapevine breeding programs.

3.1. Run1/Rpv1 Locus

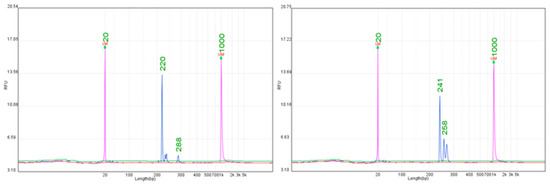

Five SSR markers previously reported for the Run1/Rpv1 resistance locus (VMC4f3.1, VMC8g9, Sc34-8, Sc35-2, and VMC1g3.2) were evaluated across cultivars carrying this locus (Supplementary Table S3). Considerable variability was observed among the markers. Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 consistently amplified alleles matching the expected fragment sizes and generated clear single peaks, making them the most robust markers in this set (Figure 1). These markers showed stable amplification across all tested cultivars, with minimal background noise and no additional non-specific peaks. In contrast, VMC4f3.1 and VMC8g9 frequently amplified additional fragments or produced size shifts greater than 5 bp compared to reference values, complicating allele interpretation. VMC1g3.2 occasionally yielded alleles close to the expected 122 bp, but signals were weak and inconsistent between cultivars. This variability is consistent with previous reports, which noted that only a subset of SSRs linked to Run1/Rpv1 are transferable across different genetic backgrounds [50]. The stable amplification obtained with Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 highlights their suitability for MAS, where markers must be reproducible and easy to interpret. Reliable detection of Run1/Rpv1 is particularly important given its contribution to durable resistance to powdery mildew, and our results indicate that these two markers can serve as primary diagnostic tools in breeding pipelines.

Figure 1.

Representative electropherograms for the Run1/Rpv1 locus obtained with SSR markers Sc34-8 (220 bp) and Sc35-2 (241 bp).

3.2. Ren3/Ren9 Loci

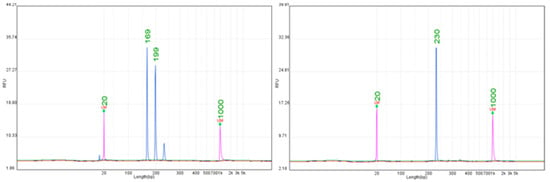

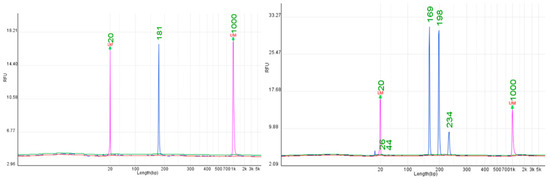

Eight SSR markers linked to Ren3 (GF15-42, GF15-28, GF15-30, VChr15CenGen06) and Ren9 (Indel-19, Indel-20, Indel-27, Indel-13) were tested across cultivars carrying these loci (Supplementary Table S4). Considerable heterogeneity in performance was observed, consistent with earlier studies noting limited reproducibility of markers in this chromosomal region [39]. Among the tested markers, Indel-27 and Indel-20 were the most reliable (Figure 2). Indel-27 consistently amplified fragments in the range of 229–231 bp, which were concordant across all tested genotypes. Indel-20 amplified alleles at 167–169 bp, again showing stable profiles without additional non-specific fragments. Both markers produced sharp, high-intensity peaks that were straightforward to score, establishing them as reliable diagnostic tools for Ren3/Ren9 [51,52]. In contrast, GF15-28, GF15-30, and Indel-13 often produced complex amplification patterns, including multiple peaks and size deviations exceeding 10 bp, which complicated allele calling. GF15-42 and VChr15CenGen06 amplified products near expected sizes, but variability between cultivars limited their reproducibility compared to Indel-27 and Indel-20. The identification of two robust markers, Indel-27 and Indel-20 is particularly valuable for breeding, since Ren3 and Ren9 have been introgressed into many modern resistant cultivars [38]. Their consistent allele sizes across cultivars reduce ambiguity during selection and provide breeders with simple, reproducible molecular tools for integrating resistance from chromosome 15 into elite backgrounds.

Figure 2.

Representative electropherograms for the Ren3/Ren9 locus obtained with SSR markers Indel-20 (169 bp) and Indel-27 (230 bp).

3.3. Rpv3 Locus

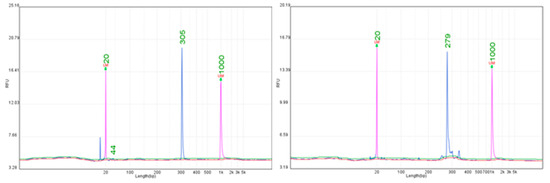

Five markers were tested for the Rpv3 resistance locus (UDV305, UDV737, UDV108, VVIv67, GF18-8). Of these, only UDV305 and UDV737 consistently amplified alleles of diagnostic value, while the remaining markers showed poor reproducibility or frequent non-specific products (Figure 3, Supplementary Table S5). A more detailed evaluation revealed differences depending on the Rpv3 sub-locus. For Rpv3.1, UDV305 amplified alleles at 303–305 bp, while UDV737 consistently yielded alleles at 279–281 bp. Both markers produced clear, strong peaks in this sub-locus (Figure 3). For Rpv3.2, UDV305 failed to produce a product (null allele), whereas UDV737 generated consistent alleles at 291 bp across all tested cultivars. For Rpv3.3, UDV305 again produced null alleles, while UDV737 reliably amplified alleles at 272–273 bp. These results highlight the superior versatility of UDV737, which consistently amplified across all three Rpv3 sub-loci, in contrast to UDV305, which was informative only for Rpv3.1. The other tested markers (UDV108, VVIv67, GF18-8) showed high variability and frequent allele size shifts (>10 bp), making them unreliable. This distinction is highly relevant for MAS: while UDV305 can serve as a supplementary marker for Rpv3.1, the reproducibility of UDV737 across all three sub-loci makes it the most practical choice for breeders. Its use enables accurate tracking of Rpv3 in segregating populations and ensures reliable introgression of this important downy mildew resistance locus.

Figure 3.

Representative electropherograms for the Rpv3 locus obtained with SSR markers UDV 305 (305 bp) and UDV 737 (279 bp).

3.4. Rpv10 Locus

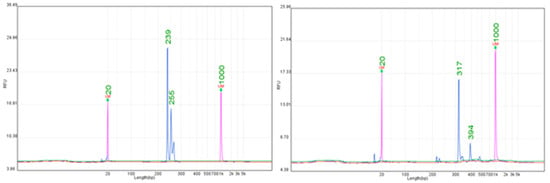

The Rpv10 resistance locus was analyzed using several SSR markers, but only GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 showed stable and reproducible performance (Supplementary Table S6). GF-09-44 consistently amplified alleles in the 239–240 bp range, while GF-09-57 produced clear products of 317 bp (Figure 4). Both markers exhibited strong peaks and minimal background noise, making them reliable diagnostic markers. Other SSRs linked to Rpv10 were less reproducible, showing weak amplification or multiple non-specific peaks. A previous study also emphasized that only selected SSRs in the Rpv10 region are transferable across genetic backgrounds [39]. The stable allele sizes observed in this study demonstrate that GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 can be used with confidence in breeding programs, reducing the uncertainty associated with less reliable SSRs. Their reproducibility across resistant cultivars makes them particularly suitable for high-throughput MAS pipelines focused on the introgression of Rpv10.

Figure 4.

Representative electropherograms for the Rpv10 locus obtained with SSR markers GF-09-44 (239 bp) and GF-09-57 (317 bp).

3.5. Rpv12 Locus

Ten SSR markers were evaluated for the Rpv12 resistance locus (UDV350, UDV370, UDV340, UDV390, UDV348, UDV380, UDV347, UDV360, UDV345, UDV343). Considerable variation was observed among the markers (Supplementary Table S7). Several markers, such as UDV350 and UDV370, frequently amplified additional non-specific fragments or deviated substantially from expected sizes. In contrast, two markers were highly consistent across all tested cultivars: UDV340 and UDV343. UDV340 amplified alleles at 181–182 bp, and UDV343 consistently produced alleles at 168–169 bp (Figure 5). Both markers generated strong peaks, were highly concordant with reference values, and displayed stable performance across genotypes. Other markers (UDV390, UDV348, UDV380, UDV345, UDV360) showed limited reproducibility or amplified additional peaks that complicated scoring. This finding aligns with earlier work noting that only a subset of SSRs linked to resistance loci are reliable in diverse genetic backgrounds [37]. The consistent performance of UDV340 and UDV343 demonstrates their potential as primary markers for routine genotyping of Rpv12. Their reproducibility across resistant cultivars and agreement with expected allele sizes ensure their value for MAS, where accuracy and simplicity of scoring are essential.

Figure 5.

Representative electropherograms for the Rpv12 locus obtained with SSR markers UDV 340 (182 bp) and UDV 343 (169 bp).

3.6. Overview of SSR Marker Performance Across Resistance Loci

Table 2 summarizes the most reliable SSR markers identified in this study for each resistance locus. Although multiple markers were tested per locus, only a limited subset showed stable and reproducible performance across cultivars.

Table 2.

Reliable SSR markers identified for grapevine resistance loci and their corresponding allele sizes.

For Run1/Rpv1, Sc34-8 (220–221 bp) and Sc35-2 (240–241 bp) consistently amplified the expected allele sizes and produced clear single peaks, confirming their diagnostic value. Within the Ren3/Ren9 region, Indel-27 (229–231 bp) and Indel-20 (167–169 bp) showed superior reproducibility compared to other markers, which often produced additional peaks or shifted allele sizes. For Rpv3, UDV305 and UDV737 provided informative alleles for the Rpv3.1 sub-locus (303–305 bp and 279–281 bp, respectively), while UDV737 was the most versatile marker overall, reliably amplifying alleles at 291 bp (Rpv3.2) and 272–273 bp (Rpv3.3). Other tested markers (UDV108, VVIv67, GF18-8) showed poor reproducibility and are not recommended for practical use. For Rpv10, GF-09-44 (239–240 bp) and GF-09-57 (317 bp) consistently matched expected fragment sizes and produced strong peaks, making them suitable for routine application. For Rpv12, UDV340 (181–182 bp) and UDV343 (168–169 bp) displayed high concordance with literature values and stable performance across cultivars, standing out as the most reliable markers for this locus. These results show that only a small subset of SSR markers is transferable across genetic backgrounds and suitable for marker-assisted selection. The markers listed in Table 2 can therefore be recommended as primary diagnostic tools for routine screening of resistance loci in grapevine breeding programs.

3.7. ABI Cross-Platform Validation of Selected SSR Markers

To further confirm the reliability of SSR markers across platforms, targeted ABI validation was performed for two loci using the most robust markers identified in the Qsep100 analyses: UDV737 for Rpv3 and Indel-27 for Ren3/Ren9. These markers were selected because they consistently produced clear allele calls across genotypes and showed the strongest association with their respective resistance loci.

Results showed a high level of concordance between Qsep100 and ABI data (Table 3, Supplementary Table S1). For Indel-27 (Ren3/Ren9), allele sizes obtained on ABI (values around 229 bp) matched those determined on Qsep100 (≈230 bp), with differences typically ≤2 bp. Similarly, for UDV737 (Rpv3), the ABI-derived allele sizes (280 bp) closely matched Qsep100 results, with size differences largely within the ±2 bp tolerance. Across all tested genotypes, the median Δbp was 1.0 bp, and 100.0% of allele calls fell within the concordance threshold of ≤2 bp. Marker-specific performance confirmed that Indel-27 had a median Δbp of 1.0 bp, while UDV737 showed complete agreement with a median Δbp of 0.0 bp. This level of agreement is consistent with reports of small, platform-specific sizing shifts commonly observed in SSR genotyping, which usually remain within the range of analytical tolerance. The validation confirms that both UDV737 and Indel-27 are highly transferable between genotyping platforms, reinforcing their suitability as diagnostic markers for resistance screening. Although ABI validation was limited to these two markers, the high degree of concordance supports the broader application of Qsep100 data for the other loci tested in this study. Moreover, validation on experimental breeding genotypes further emphasizes marker robustness across diverse genetic backgrounds, not only in registered cultivars but also in novel selections relevant for ongoing breeding programs.

Table 3.

Targeted ABI cross-platform validation was performed for two SSR markers: UDV737 (Rpv3 locus) and Indel-27 (Ren3/Ren9 region).

3.8. Intra- and Inter-Day Precision of SSR Marker Analysis

Allele sizing reproducibility was evaluated for selected SSR markers associated with the resistance loci Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, Rpv10, and Rpv12. Intra-day precision was assessed using two replicates per genotype on the same day, while inter-day precision was determined across four consecutive days with the same number of replicates (Table 4). Overall, the results showed exceptionally high stability, with allele sizes remaining identical (±0 bp) in most cases.

Table 4.

Intra- and inter-day precision of SSR marker analysis on the Qsep100 system. Results are expressed as the observed differences in allele size (bp) between replicates.

For the Run1/Rpv1 locus, markers Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 showed perfect intra-day stability, with inter-day variation limited to ±1 bp only in Vidoc, while all negative controls (Graševina, Grk, Maraština) consistently produced non-resistance alleles without spurious amplification. For Ren3/Ren9, Indel-27 and Indel-20 demonstrated stable allele calling in all resistant cultivars, with only occasional ±1 bp shifts observed between days, particularly in multi-allelic profiles such as Accent, Muscaris, and Voltis. Importantly, the negative controls amplified distinct allele sizes outside the resistance-associated range, confirming the specificity of these markers. Markers linked to Rpv3 (UDV305, UDV737) exhibited slightly higher inter-day variability, particularly in complex genotypes like Cabernet Cantor, Phoenix, and Souvignier Gris, where shifts of ±1–2 bp were recorded. Nevertheless, the negative controls consistently yielded allele sizes unrelated to the expected resistant haplotypes, validating the discriminatory capacity of the marker set. For Rpv10 (GF-09-44, GF-09-57) and Rpv12 (UDV340, UDV343), both intra- and inter-day reproducibility were excellent, with almost all calls stable at ±0 bp and only rare ±1 bp shifts (e.g., Cabernet Cortis and Merlot Khorus). As with other loci, negative controls amplified allele sizes clearly outside resistance ranges, further demonstrating assay specificity. Overall, the inclusion of susceptible cultivars as negative controls reinforced the robustness of the system by confirming both the reproducibility and specificity of SSR-based genotyping. The minimal intra- and inter-day variability observed, together with the clear distinction between resistant and susceptible profiles, underscores the suitability of Qsep100 for routine marker-assisted selection in grapevine breeding.

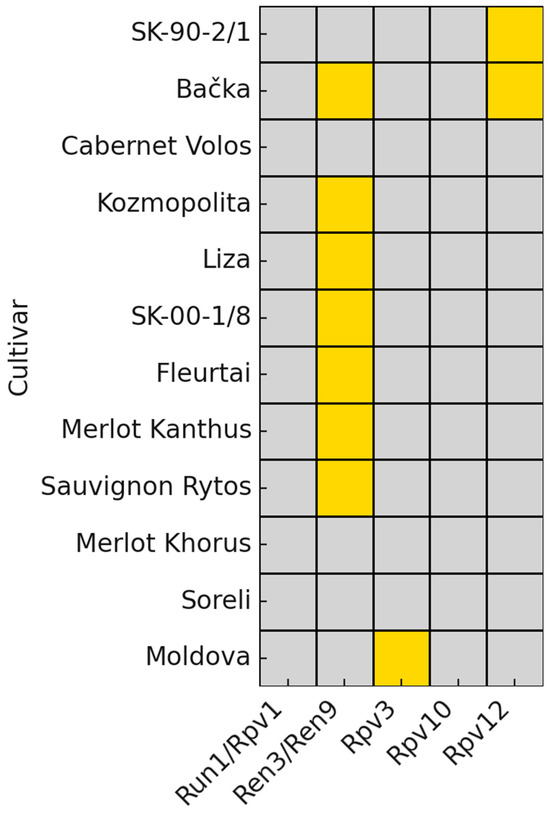

3.9. Validation of SSR Marker Performance Across Genotypes

In the final validation step, analysis was conducted on a panel of grapevine cultivars whose resistance status had previously been uncertain. The genotypes included in this step were SK-90-2/1, Bačka, Cabernet Volos, Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, Fleurtai, Merlot Kanthus, Sauvignon Rytos, Merlot Khorus, Soreli, and Moldova (Figure 6, Supplementary Table S8). These cultivars were selected because their allelic composition had not been fully clarified, making them key materials for testing the applicability of the optimized SSR marker set in breeding contexts with incomplete genetic information. All cultivars were analyzed with markers linked to the Run1/Rpv1 and Ren3/Ren9 loci to assess the presence of resistance-associated alleles. Additionally, a subset of cultivars (SK-90-2/1, Bačka, Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, and Moldova) was further tested with markers associated with the Rpv3, Rpv10, and Rpv12 loci.

Figure 6.

Distribution of resistance loci across tested cultivars. Fields highlighted in yellow indicate fragment sizes corresponding to resistance alleles, thereby confirming the presence of the respective resistance locus. The presence of previously confirmed resistance loci is shown in the Table 1.

None of the genotypes carried the diagnostic fragments of 220 bp (Sc34-8) and 241 bp (Sc35-2), which are associated with the presence of Run1/Rpv1. The absence of these alleles across the panel suggests that this resistance locus is not represented in the material analyzed. Resistance-associated fragments linked to Ren3/Ren9 were detected in most genotypes, confirming the presence of this locus in the majority of the panel. Specifically, resistant alleles were present in Bačka, Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, Fleurtai, Merlot Kanthus, and Sauvignon Rytos. In contrast, SK-90-2/1, Cabernet Volos, Merlot Khorus, Soreli, and Moldova did not show the expected fragment sizes, indicating the absence of Ren3/Ren9 in these cultivars. A subset of cultivars (SK-90-2/1, Bačka, Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, and Moldova) was tested with UDV305 and UDV737, which discriminate between sub-loci Rpv3.1, Rpv3.2, and Rpv3.3. Among these genotypes, resistant fragments were identified only in Moldova, where the allele combination corresponded to Rpv3.2. None of the other cultivars in this subset carried diagnostic alleles for any of the Rpv3 sub-loci. The same subset (SK-90-2/1, Bačka, Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, and Moldova) was also analyzed with markers GF-09-44 and GF-09-57, which are diagnostic for Rpv10. In this panel, no cultivar carried the expected resistance-associated alleles, and all observed fragments fell outside the diagnostic size ranges. These results indicate that the Rpv10 locus is absent in the tested genotypes and confirm that this resistance source is not contributing to the genetic background of the analyzed breeding material. The absence of Rpv10 is consistent with the limited distribution of this locus in grapevine germplasm reported in earlier studies and underscores the importance of focusing on alternative resistance loci for selection within this panel [38]. The presence of Rpv12 was evaluated using markers UDV340 and UDV343 in the same subset of cultivars. Resistance-associated fragments were detected only in SK-90-2/1 and Bačka, confirming the introgression of Rpv12 in these two genotypes. No diagnostic alleles were observed in Kozmopolita, Liza, SK-00-1/8, or Moldova, indicating the absence of this resistance locus in their genetic background. These findings demonstrate the restricted distribution of Rpv12 among the analyzed breeding material and emphasize the role of specific genotypes such as SK-90-2/1 and Bačka as carriers of this valuable resistance source. Because no reliable pedigree information exists for these cultivars in the available literature, it was not possible to infer the expected presence of resistance alleles based on parentage.

3.10. Evaluation of the Qsep System

An important aspect of this study was the evaluation of the Qsep100 system as an alternative to conventional capillary electrophoresis platforms such as ABI. The main advantages of Qsep are its speed and simplicity, requiring minimal sample preparation and short run times, as well as lower costs due to the absence of fluorescently labeled primers and expensive consumables. The system also demonstrated high reproducibility, as confirmed by intra- and inter-day precision testing, making it suitable for routine applications in marker-assisted selection pipelines. Technically, the S1 High Resolution Cartridge enables DNA fragment sizing from 20 to 5000 bp, with a detection limit as low as 0.1 ng/µL and a recommended working concentration of 0.1–10 ng/µL. Only small sample volumes are required (≥2 µL), with actual consumption per run well below this amount. The system offers a resolution of 1–4 bp, which is sufficient for most SSR applications in grapevine. However, the absence of fluorescently labeled primers limits multiplexing capacity, and the ability to confidently resolve alleles separated by only a few base pairs can be slightly lower compared to ABI. Despite these limitations, the overall performance, robustness, and cost-effectiveness of the Qsep platform indicate that it is a reliable tool for SSR marker analysis and routine application in grapevine breeding programs.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of SSR marker analysis for grapevine resistance breeding, with a particular focus on validating the Qsep100 platform as an alternative to conventional ABI capillary electrophoresis. Cross-platform comparison confirmed high concordance for selected diagnostic markers, while intra- and inter-day precision testing demonstrated the reproducibility and robustness of the Qsep100 system. The approach requires only minimal amounts of the PCR product, eliminates the need for fluorescently labeled primers, and reduces analysis costs, making it well suited for routine marker-assisted selection workflows. Among the tested markers, Sc34-8 and Sc35-2 were optimal for Run1/Rpv1, Indel-27 and Indel-20 for Ren3/Ren9, UDV305 and UDV737 for Rpv3, GF-09-44 and GF-09-57 for Rpv10, and UDV340 and UDV343 for Rpv12. These markers provided the most consistent discrimination of resistance-associated alleles and thus offer a reliable basis for practical breeding applications. By integrating optimized marker sets with validated analytical performance, this work establishes a methodological framework for the reliable detection of resistance loci in grapevine. The findings confirm that Qsep100 can be confidently implemented in breeding pipelines, while ABI remains a valuable reference for validation. Overall, the study offers advances that directly support the development of cultivars with durable resistance to downy and powdery mildew.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/horticulturae11121506/s1, Table S1: ABI cross-platform validation of selected SSR markers; Table S2: List of SSR markers used in this study, with locus assignment, primer sequences, and fragment sizes reported in the literature; Table S3: Fragment sizes (bp) obtained with SSR markers linked to Run1/Rpv1 locus; Table S4: Fragment sizes (bp) obtained with SSR markers linked to Ren3/Ren9 locus; Table S5: Fragment sizes (bp) obtained with SSR markers linked to Rpv3 locus.; Table S6: Fragment sizes (bp) obtained with SSR markers linked to Rpv10 locus; Table S7: Fragment sizes (bp) obtained with SSR markers linked to Rpv12 locus.; Table S8: Detection of diagnostic allele sizes for major resistance loci (Run1/Rpv1, Ren3/Ren9, Rpv3, Rpv10, Rpv12) in a panel of grapevine cultivars.

Author Contributions

I.T. and D.P. conceived and planned the study. N.B. and I.Š. conducted the analysis. N.B. and I.Š. interpreted the results and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. I.T. and D.P. edited and finalized the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Croatian Science Foundation, grant number IP-2022-10-9428 project “Application of metabolomics, high-throughput phenotyping and molecular markers in early selection for disease resistance in the development of new grape varieties—VitiResist”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gessler, C.; Pertot, I.; Perazzolli, M. Plasmopara viticola: A review of knowledge on downy mildew of grapevine and effective disease management. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2011, 50, 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gadoury, D.M.; Cadle-Davidson, L.; Wilcox, W.F.; Dry, I.B.; Seem, R.C.; Milgroom, M.G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): A fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, L. Review of the pathogenic mechanism of grape downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) and strategies for its control. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertot, I.; Caffi, T.; Rossi, V.; Mugnai, L.; Hoffmann, C.; Grando, M.S.; Gary, C.; Lafond, D.; Duso, C.; Thiery, D. A critical review of plant protection tools for reducing pesticide use on grapevine and new perspectives for the implementation of ipm in viticulture. Crop Prot. 2017, 97, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellin, D.; Peressotti, E.; Merdinoglu, D.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Cipriani, G.; Morgante, M.; Testolin, R.; Di Gaspero, G. Resistance to plasmopara viticola in grapevine ‘bianca’is controlled by a major dominant gene causing localised necrosis at the infection site. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009, 120, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwander, F.; Eibach, R.; Fechter, I.; Hausmann, L.; Zyprian, E.; Töpfer, R. Rpv10: A new locus from the asian vitis gene pool for pyramiding downy mildew resistance loci in grapevine. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuti, S.; Copetti, D.; Foria, S.; Falginella, L.; Hoffmann, S.; Bellin, D.; Cindrić, P.; Kozma, P.; Scalabrin, S.; Morgante, M. Historical introgression of the downy mildew resistance gene rpv12 from the asian species Vitis amurensis into grapevine varieties. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gaspero, G.; Copetti, D.; Coleman, C.; Castellarin, S.D.; Eibach, R.; Kozma, P.; Lacombe, T.; Gambetta, G.; Zvyagin, A.; Cindrić, P. Selective sweep at the rpv3 locus during grapevine breeding for downy mildew resistance. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2012, 124, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendler, D.; Töpfer, R.; Zyprian, E. Confirmation and fine mapping of the resistance locus ren9 from the grapevine cultivar ‘regent’. Plants 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Zuniga, V.; Vidal Valenzuela, Á.; Barba, P.; Espinoza Cancino, C.; Romero-Romero, J.L.; Arce-Johnson, P. Powdery mildew resistance genes in vines: An opportunity to achieve a more sustainable viticulture. Pathogens 2022, 11, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingerter, C.; Eisenmann, B.; Weber, P.; Dry, I.; Bogs, J. Grapevine rpv3-, rpv10-and rpv12-mediated defense responses against Plasmopara viticola and the impact of their deployment on fungicide use in viticulture. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massonnet, M.; Riaz, S.; Pap, D.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Walker, M.A.; Cantu, D. The grape powdery mildew resistance loci ren2, ren3, ren4d, ren4u, run1, run1. 2b, run2. 1, and run2. 2 activate different transcriptional responses to Erysiphe necator. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1096862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, V.; Crespan, M.; Maddalena, G.; Migliaro, D.; Brancadoro, L.; Maghradze, D.; Failla, O.; Toffolatti, S.L.; De Lorenzis, G. Novel loci associated with resistance to downy and powdery mildew in grapevine. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1386225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, D.; Zou, C.; Sun, Q.; Nigar, Q.; Paineau, M.; Cantu, D.; Hwang, C.-F.; Cadle-Davidson, L. Comparative genomics of rpv3, a multiallelic downy mildew resistance locus in grapevine (Vitis sp.). OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibach, R.; Töpfer, R. Progress in grapevine breeding. In Proceedings of the X International Conference on Grapevine Breeding and Genetics 1046, Geneva, NY, USA, 1–5 August 2010; pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Possamai, T.; Migliaro, D.; Gardiman, M.; Velasco, R.; De Nardi, B. Rpv mediated defense responses in grapevine offspring resistant to Plasmopara viticola. Plants 2020, 9, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Possamai, T.; Scota, L.; Velasco, R.; Migliaro, D. A sustainable strategy for marker-assisted selection (MAS) applied in grapevine (Vitis spp.) breeding for resistance to downy (Plasmopara viticola) and powdery (Erysiphe necator) mildews. Plants 2024, 13, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brault, C.; Segura, V.; Roques, M.; Lamblin, P.; Bouckenooghe, V.; Pouzalgues, N.; Cunty, C.; Breil, M.; Frouin, M.; Garcin, L. Enhancing grapevine breeding efficiency through genomic prediction and selection index. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2024, 14, jkae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdinoglu, D.; Schneider, C.; Prado, E.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Mestre, P. Breeding for durable resistance to downy and powdery mildew in grapevine. OENO One 2018, 52, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.A.; Ibáñez, J.; Lijavetzky, D.; Vélez, D.; Bravo, G.; Rodríguez, V.; Carreño, I.; Jermakow, A.M.; Carreño, J.; Ruiz-García, L. A 48 snp set for grapevine cultivar identification. BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žulj Mihaljević, M.; Maletić, E.; Preiner, D.; Zdunić, G.; Bubola, M.; Zyprian, E.; Pejić, I. Genetic diversity, population structure, and parentage analysis of croatian grapevine germplasm. Genes 2020, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyman, L.; Höfle, R.; Kicherer, A.; Trapp, O.; Ait Barka, E.; Töpfer, R.; Höfte, M. The durability of quantitative host resistance and variability in pathogen virulence in the interaction between european grapevine cultivars and Plasmopara viticola. Front. Agron. 2021, 3, 684023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, S.; Mertes, C.; Kaltenbach, T.; Bleyer, G.; Fuchs, R. A method for phenotypic evaluation of grapevine resistance in relation to phenological development. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Chen, H.; Hu, Z.; Gao, L.; Chen, L.; Ren, S.; Ma, H.; Lu, L. An accurate and efficient method for large-scale ssr genotyping and applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazıcı, K.; Gönülkırmaz, B.; Şahin Çevik, M. Development of molecular marker linked to seed hardness in pomegranate using bulked segregant analysis. Life 2023, 13, 1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durney, B.C.; Crihfield, C.L.; Holland, L.A. Capillary electrophoresis applied to DNA: Determining and harnessing sequence and structure to advance bioanalyses (2009–2014). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 6923–6938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covarrubias-Pazaran, G.; Diaz-Garcia, L.; Schlautman, B.; Salazar, W.; Zalapa, J. Fragman: An r package for fragment analysis. BMC Genet. 2016, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgardt, N.; Weissenberger, M. First experiences with the spectrum compact CE system. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2022, 136, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Jiang, X.; Lu, C.; Liu, J.; Diao, S.; Jiang, J. Genetic diversity and population structure analysis in the chinese endemic species michelia crassipes based on ssr markers. Forests 2023, 14, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- This, P.; Jung, A.; Boccacci, P.; Borrego, J.; Botta, R.; Costantini, L.; Crespan, M.; Dangl, G.; Eisenheld, C.; Ferreira-Monteiro, F. Development of a standard set of microsatellite reference alleles for identification of grape cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merdinoglu, D.; Butterlin, G.; Bevilacqua, L.; Chiquet, V.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Decroocq, S. Development and characterization of a large set of microsatellite markers in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) suitable for multiplex pcr. Mol. Breed. 2005, 15, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Marrazzo, M.T.; Di Gaspero, G.; Pfeiffer, A.; Morgante, M.; Testolin, R. A set of microsatellite markers with long core repeat optimized for grape (Vitis spp.) genotyping. BMC Plant Biol. 2008, 8, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tympakianakis, S.; Trantas, E.; Avramidou, E.V.; Ververidis, F. Vitis vinifera genotyping toolbox to highlight diversity and germplasm identification. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1139647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lu, J.; Ren, Z.; Hunter, W.; Dowd, S.E.; Dang, P. Mining and validating grape (Vitis L.) ests to develop est-ssr markers for genotyping and mapping. Mol. Breed. 2011, 28, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokupilova, I.; Sturdik, E.; Mihalik, D. Characterization of vine varieties by ssr markers. Acta Chim. Slovaca 2013, 6, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Julius Kühn-Institut. Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC). Available online: https://www.vivc.de/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).[Green Version]

- Cretazzo, E.; Moreno Sanz, P.; Lorenzi, S.; Benítez, M.L.; Velasco, L.; Emanuelli, F. Genetic characterization by ssr markers of a comprehensive wine grape collection conserved at rancho de la merced (Andalusia, Spain). Plants 2022, 11, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Töpfer, R.; Trapp, O. A cool climate perspective on grapevine breeding: Climate change and sustainability are driving forces for changing varieties in a traditional market. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 3947–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, E.; Dolzani, C.; Stefanini, M.; Gratl, V.; Bettinelli, P.; Nicolini, D.; Betta, G.; Dorigatti, C.; Velasco, R.; Letschka, T. R-loci arrangement versus downy and powdery mildew resistance level: A vitis hybrid survey. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.vivairauscedo.com/en/product-index/resistant/ (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Ivanisević, D.; Di Gaspero, G.; Korać, N.; Foria, S.; Cindrić, P. Grapevine genotypes with combined downy and powdery mildew resistance. In Proceedings of the XI International Conference on Grapevine Breeding and Genetics 1082, Beijing, China, 28 July–2 August 2014; pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, C.L.; Donald, T.; Pauquet, J.; Ratnaparkhe, M.; Bouquet, A.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Thomas, M.; Dry, I. Genetic and physical mapping of the grapevine powdery mildew resistance gene, run1, using a bacterial artificial chromosome library. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005, 111, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doligez, A.; Adam-Blondon, A.-F.; Cipriani, G.; Di Gaspero, G.; Laucou, V.; Merdinoglu, D.; Meredith, C.; Riaz, S.; Roux, C.; This, P. An integrated SSR map of grapevine based on five mapping populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006, 113, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VIVC. Table of Loci for Traits in Grapevine. Available online: https://www.vivc.de/docs/dataonbreeding/20240216_Table%20of%20Loci%20for%20Traits%20in%20Grapevine.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Zyprian, E.; Ochßner, I.; Schwander, F.; Šimon, S.; Hausmann, L.; Bonow-Rex, M.; Moreno-Sanz, P.; Grando, M.S.; Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S.; Merdinoglu, D. Quantitative trait loci affecting pathogen resistance and ripening of grapevines. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2016, 291, 1573–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendler, D.; Schneider, P.; Töpfer, R.; Zyprian, E. Fine mapping of ren3 reveals two loci mediating hypersensitive response against Erysiphe necator in grapevine. Euphytica 2017, 213, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gaspero, G.; Cipriani, G.; Marrazzo, M.T.; Andreetta, D.; Castro, M.J.P.; Peterlunger, E.; Testolin, R. Isolation of (AC)n microsatellites in Vitis vinifera L. and analysis of genetic background in grapevines under marker-assisted selection. Mol. Breed. 2005, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwander, F. Identifikation des Mehltauresistenzlocus Rpv10 für die Rebenzüchtung. Doctoral Thesis, Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Agurto, M.; Schlechter, R.O.; Armijo, G.; Solano, E.; Serrano, C.; Contreras, R.A.; Zúñiga, G.E.; Arce-Johnson, P. Run1 and ren1 pyramiding in grapevine (Vitis vinifera cv. Crimson seedless) displays an improved defense response leading to enhanced resistance to powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migliaro, D.; De Lorenzis, G.; Di Lorenzo, G.S.; De Nardi, B.; Gardiman, M.; Failla, O.; Brancadoro, L.; Crespan, M. Grapevine non-vinifera genetic diversity assessed by simple sequence repeat markers as a starting point for new rootstock breeding programs. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 70, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Tenscher, A.; Ramming, D.; Walker, M. Using a limited mapping strategy to identify major qtls for resistance to grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) and their use in marker-assisted breeding. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 1059–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katula-Debreceni, D.; Lencsés, A.; Szőke, A.; Veres, A.; Hoffmann, S.; Kozma, P.; Kovács, L.; Heszky, L.; Kiss, E. Marker-assisted selection for two dominant powdery mildew resistance genes introgressed into a hybrid grape population. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 126, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).